ABSTRACT

A comprehensive understanding of the assessment of an urban space by its residents is viewed as one of the most in demand approaches within the endogenous strategies of urban space planning. As a rule, this process only leads to the identification of topophilic or topophobic places. What is lacking is the identification and interpretation of places that may contain both topophobic and topophilic meanings. Thus, the main objective of this paper is to explore, analyse, and compare ambivalently perceived places within an urban environment. Methodologically, the paper stems from the perception of space. More specifically, the phenomenon of mental maps is elaborated on. The analysis proves the ambivalent perception of selected places in the town under study (Šternberk, the Czech Republic), which points, to the complexity of human perception that characterises each community. Two synthetic maps based on four follow-up methodical procedures are provided, accompanied by two analytical maps.

1. Introduction

One of the main characteristics of an urban space is dynamism. Towns and cities undergo constant development which can be understood as a complex process concerning environmental, social, structural, and functional dimensions of an urban space. Sustainable urban development can be stimulated through urban management. The ultimate goal of urban management is to achieve a state where citizens are able to identify with their own town or city. (CitationJežek, 2004)

Strategic planning is understood as one of the possible ways to manage urban development (CitationStein, 2017). Strategic planning is a long-term process, and its formal output is a document called a strategic plan. However, a strategic plan is not the ultimate goal of a strategic planning. Rather, a strategic plan is seen as a record of the consensus of strategic planning participants on the vision of the future, common goals, and priorities leading to its fulfilment. The implementation of a strategic plan should lead to changes in the town for the better. The strategic plan should be developed primarily for the purposes inclusive of the entire community based on its needs, desires, and public interest as well as serve the community as a whole. It should not be a document that promotes only the interests of one group or political representation (CitationStein, 2017). From the point of view of the basic strategic planning of urban development which distinguishes between exogenous and endogenous strategies, the use of an endogenous strategy is more appropriate for the process of bringing about a strategic plan. Among other things, this idea is fuelled by the fact that local actors are themselves best able to set strategic goals and control the development process. Local actors (i.e. residents, entrepreneurs, politicians) are considered to be the driving force of urban development (CitationVazquez-Barquero, 2002). Thus, one of the approaches within the endogenous strategy is the process of involving residents in activities that lead to the decision of the further development of the municipality.

CitationLynch (Citation1960) expressed the above-mentioned ideas nearly 60 years ago when he stressed that making the planning, design, and management of urban space more suitable for residents is only possible if it is implemented with them. Once planners are aware of the different preferences, views, values, meanings, and attitudes to various places in general (based on different perceptions of residents towards their urban space), it is more efficient and accurate to find a match between the real needs of the population and the specific steps in the decision making process (CitationGolledge & Stimson, 1997). One of the approaches that can serve to capture, express, and eventually discuss the different meanings and attitudes to specific places within urban spaces is the use of specific psychological images – specifically mental maps.

Learning and subsequent assessment of space leads to the meanings that man attributes to certain places. CitationTuan (Citation1975) defined two basic categories of place importance – topophilia (positive) and topophobia (negative). Topophilic and topophobic places represent the parts of a social space formed perceptually, that is, by mental processes to which particular experiences with the places are used (CitationSiwek, 2011). Hence, they are stored in mental maps of human beings. At the same time, the two terms frequently are understood as opposites, dichotomies in the context of geographical research (CitationBowring, 2013; CitationGhioca, 2014; CitationPánek, 2019; CitationStasíková, 2013). On the one hand, there is a topophilic place: a pleasant, popular, and desirable place. It is a type of place that connotes positive feelings (CitationSiwek, 2011) and people attribute positive meanings to such a place. On the other hand, it is possible to identify a topophobic place that evokes negative feelings among people (CitationRuan & Hogben, 2007). This kind of place is given negative meanings and is experienced as an unpleasant, repulsive, and consciously rejected place. What is lacking, however, is a more comprehensive view of places. Specifically, the identification and interpretation of places that may contain both topophobic and topophilic meanings. Based on this circumstance and using data from the Czech Republic, the main aim of the article is to explore, analyse, and compare ambivalently perceived places within an urban environment. The successful fulfilment of the main aim will enable city planners and scholars to assess the implementation of gained knowledge in the process of strategic planning of urban development.

2. The town under study

The object of the research is the town of Šternberk that is situated in the eastern part of the Czech Republic (see map). The town is one of the oldest in the country as its history dates back to the 13th century. The population size of the town is rather small, with 13,603 inhabitants as of 1st January 2019 (CitationMICR, 2019). Since 2003, Šternberk has had a status of a municipality with extended powers. This fact means that Šternberk is the administrative centre of the region, which currently consists of 22 municipalities and 24,199 inhabitants (CitationCZSO, 2019). The recent intention of the town council has been to create a new developmental strategy of the town, last updated in 2007.

The physical structure of the town comprises of several functionally different parts. The centre is dominated by the Šternberk State Castle from the 13th century and the nearby Baroque Church of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. Both landmarks are located near the Upper Square and together with adjacent streets create the Šternberk Urban Heritage Zone (CitationNational Heritage Institute, 2015). In the central part of the town on the site of a former cemetery, there is a park called Tyršovy sady, which was built in the twentieth century. The park represents an important relaxation zone for residents. The north-eastern edge of Šternberk consists of extensive residential areas with detached houses. There are prefabricated housing estates located in the eastern and western parts of the city that again perform a residential function. The southern part of the town includes the industrial zone where the largest enterprises reside. A significant part of Šternberk (49%) is occupied by woods, especially in the north and east of the cadastre. Thanks to the natural character of the woods, these parts of the town landscape are used year-round. There is also a frequently visited gazebo called Zelená budka.

The presence of residents living in the five socially excluded locations significantly influences the socio-economic development of the town. According to estimates (CitationESFR, 2015), this group of people represent 200–400 inhabitants of the town and are mainly composed of Roma, homeless, and other socially challenged people.

3. Methodology and methods

CitationGolledge and Stimson (1997, p. 190) understood perception as the immediate apprehension of information about the environment. This primarily happens via one or more of the senses. Secondary environmental information is culled from the media and through hearsay via communication with fellow human beings. Thus, perception is considered to be the result of mental activity which is produced by perceiving current stimuli in the environment and the ability of imagination. Mental maps can be the result of such a process. They are stored in the human mind and can be recalled, if necessary. The geographical concept of mental maps can be represented by CitationTuan (Citation1975) who stated that a mental map is a special kind of image which is even less directly related to sensory experience – that the mental map could be the cartographic representation of peoples’ attitudes toward places for geographers (Drbohlav, Citation1991).

The research on mental maps is based on data of a primary type provided by a questionnaire which took place in Šternberk in the period from August 2018 until January 2019. In total, 133 respondents aged 15 years and higher were addressed by the face-to-face method, which represents 1.22% of the inhabitants of the town. Mental mapping is closely linked with the experience of the respondents who are addressed. This experience varies considerably in terms of age, education, length of stay in the town, or gender (CitationGolledge & Stimson, 1997). For this reason, it was necessary to ensure the qualitative representativeness of the research sample with respect to the population structure of the town aged 15 years and higher in the above categories. On the basis of the completed χ² testing (), it can be stated that the ensured research sample is qualitatively representative with a probability of 95% and more. Its selected structures are not statistically significantly different from those of the total population of a town aged 15 years and higher.

Table 1. Socio-demographic profiles of the research sample and the population of the town aged 15 years and higher (%) and χ2 test results.

In the questionnaire, we used the maps of the town in a paper form with the scale that made it possible to distinguish individual streets and buildings. The advantage of paper maps and face-to-face responding was undoubtedly the opportunity to look deeper beneath the surface of the primary data and to understand the cognitive processes of the respondents. At the same time, we used the method of the revealed preferences (CitationGould & White, 1993), i.e. preferences without alternatives presented. The respondents were exclusively residents of the town which largely eliminated the risk of ignorance of the environment being examined.

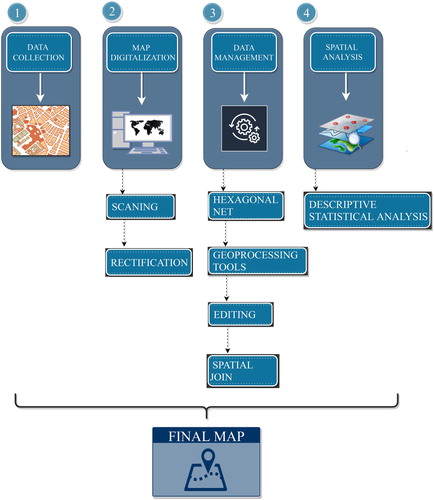

The primary data collection was the first of four steps that led to the production of the Main Map outputs. In this step residents of Šternberk were asked to look at the topographic map and draw places, where they feel well and places, where they feel bad. It was followed by map digitisation, data management, and spatial analysis (). Sketches made by respondents were subsequently processed in GIS software. Through the hexagonal network that was used, the town was divided into uniformly large units. In this way, 5,778 hexagons were established to carry out a methodologically correct comparison and evaluation using selected statistical procedures. The final map shows results of such processing in the form of the hexagonal network containing red, blue and violet colour. Red colour represents topophobic places (negatively perceived places), blue colour represents topophilic places (positively perceived places) and violet colour represents topo-ambivalent places (places perceived both positively and negatively). This is also the main added value of authors. The rest of map background (buildings, street network, railways and rivers) serves as topographic information showing spatial context.

4. Results

On the basis of the analysis of the primary data, both topophilic and topophobic places are identified in the area of the town that was examined. It is shown that these contrary types of perception overlap in many cases. Accordingly, a third type of perception has been identified in the town defined as topo-ambivalent based on its duality (see Main Map).

4.1. Typology of the topo-ambivalent places

In the town of Šternberk, nine larger or smaller ambivalently perceived places were identified in which the respondents declared that they attributed both positive and negative meanings (). The most extensive place with a topo-ambivalent attribute is the historical centre of the town (1), which the inhabitants favour, but at the same time are afraid to visit because of the presence of the Roma minority. This reason is multiplied after dark. The town park (2), which is the second-largest topo-ambivalent place, has a very similar character. The often-sought-after municipal swimming pool (6) is one of the smallest places, but even there are some reasons that placed it in an ambivalent position. This is due to repeated conflicts in which Roma people are again involved.

Table 2. Topo-ambivalent places in the town of Šternberk and the most frequent feelings that residents had towards them.

The analysis of the perception of places no. 7, 8 and no. 9 points to two important factors that can transform otherwise positive experiences. These include heavy traffic and the unpleasant appearance of buildings, and these factors also appear in other selected places.

The different ambivalence in the perception of the town being surveyed is particularly evident when the results of people who have moved to the town and those who have lived in it since birth are compared. This comparison shows, above all, the better knowledge of Šternberk by its native residents, whose images were considerably more complex. Compared to the inhabitants who have moved into the town, the images of the native residents included, for example, a wider definition of a topophobic place around the train station, but especially a large topophilic place extending from the town centre deep into the forests in the eastern section of the cadastral area (see Main Map). As a result, topo-ambivalent places are more likely to be perceived by native residents and primarily cover the entire town centre, the town park, and a part of the adjacent forests. Newcomers mostly perceive in the ambivalent way the historical centre, the park, and two specific busy roads.

4.2. Semantic meanings of topo-ambivalent places

The verbal arguments of the respondents listed in also encourage the evaluation of the ambivalence of the area of the town by means of a semantic map. Such a way of visualising a map reflects the characteristics of a socially constructed space through the interconnection of mental mapping and the linguistic meaning of the respondents’ verbal declarations. Thus, it is possible to analyse the meanings with which specific places are associated and to produce semantic places based on their semantic proximity (CitationOsman, 2016).

The semantic map of the town of Šternberk contains nine semantically ambivalent places (see Main Map), which are based on the identified topo-ambivalent places (). The frequency of the repetition of the most commonly used word determinations (2–16 times) is reflected by the font size. In characterising these places, residents declared a perceptual ambivalence primarily in the town centre (1). The predominant negative significance of this place is the presence of the Roma population and unadaptable people, which mixes with positively perceived meanings such as ‘centre’, ‘culture’, and ‘relaxation’. Another ambivalently perceived place, the part of space around the ice hockey stadium (3), is the third largest in area and combines positive meanings such as ‘sport’ and ‘quiet zone’ with negative ones such as ‘heavy traffic’ and ‘the appearance of the buildings’.

A greater number of different words were used in the final interpretation of the topophobic meanings, but this does not mean that the respondents perceive the town more negatively. It should be borne in mind that although the semantic map contains fewer topophilic meanings of places, the magnitude of these meanings and the frequency of repetitions are greater. It means that the inhabitants were able to agree more on the positive characteristics of places than on the negative ones.

5. Conclusions and their discussion

Considering the ambivalent perceptions of the selected places that were studied, the findings of the study can be compared with a research study from Ljubljana (CitationKrevs, 2004). In order to clarify the perception of places in Ljubljana located in the neighbourhood of the respondents, the author defined three types of perception of the neighbourhood. In addition to two ‘pure’ types (positive or negative perceptions), there was a third type that absorbed positive and negative perceptions (e.g. hate and love). In this research, the ‘centre’ of the neighbourhood was characterised by the most significant ambivalence and, like the centre of Šternberk, was the most widely defined topo-ambivalent place.

A third type of perception was also mentioned in a study from Bucharest, Romania (CitationCucu et al., 2011). In this case, the topophilic and topophobic places are complemented by what was called the topo-indifferent category. This category includes transit parts of places whose individual elements do not generate sufficiently strong meanings to be classified into either of the two semantically dichotomous types (topophilic, topophobic) of locations. As a result, it is the opposite of the topo-ambivalent places, which in turn are characterised by the presence and overlap of both options.

Public greenery, as a common part of the urban space, took an important position in the research into the perception of Šternberk, very similarly to the findings revealed through research in Guangzhou, China (CitationJim & Chen, 2006). It consisted of a significant ambivalence shown towards public greenery, which is determined by the time of day in both municipalities.

The ambivalent properties of space are also viewable through a semantic map. It enables individual places to be visualised without violating the unique significance of these places. A significant similarity to the construction of the semantic map of Šternberk is observable in CitationOsman (Citation2016) who delineated semantic places on the territory of the town of Ústí nad Orlicí. In contrast to his research, however, some semantic places of Šternberk contain considerably more expressive meanings.

The above-mentioned basic knowledge gained through the research in Šternberk has brought many relevant findings. One of them is that the mental maps of residents can also be used in the process of strategic planning. Involving the analysis of residents’ mental maps in activities aimed at deciding on the future development of the town can lead to the correct setting of strategic goals so that they are in line with the needs of the residents. In our particular case, the semantically ambivalent places within the town that was studied were identified and structured by means of the mental maps of the residents. This makes it possible to subsequently implement this knowledge into the new Municipal Development Strategy through several priority axes (technical and transport infrastructure, housing, etc.).

The research has shown a significant differentiation of ambivalent perception between native residents and newcomers in Šternberk. In the final analysis, the ambivalence of the perception of selected places in the town's space that was identified points, above all, to the complexity of human perception (CitationGolledge & Stimson, 1997), which is characteristic of any community. While for one person a park can be a favourite place that is associated with relaxation, for another, it may represent a dark part of the town where it is not possible to feel comfortable. Moreover, the resulting perception is greatly enhanced by the personal experience, attitudes, and opinions of each individual (CitationRelph, 1976). These important facts should not be neglected in the strategic planning of urban development.

Software

The was created via free accessible online open source technology stack for building diagramming applications CitationDraw.io (Citation2019). All other operations including creation of the final maps were carried out within the environment of SW ArcGIS 10.4 and QGIS 3.8. Adobe Illustrator CC 2017 was used for Main Map visualisation.

Revised_Main_map.pdf

Download PDF (28.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to acknowledge the support received from the students’ grant project titled ‘Regions and cities: analysis of development and transformation’ funded by the Palacký University Olomouc Internal Grant Agency (IGA_PrF_2018_018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bowring, J. (2013). Topophilia and topophobia in the post-earthquake landscape of Christchurch, New Zealand. REV. GEO. SUR, 4(6), 103–122.

- Cucu, L. A., Ciocanea, C. M., & Onose, D. A. (2011). Distribution of urban green spaces - an indicator of topophobia - topophilia of urban residential neighborhoods. Case study of 5th district of Bucharest, Romania. Forum Geographic, 10(2), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.5775/fg.2067-4635.2011.012.d

- CZSO. (2019). SO ORP Šternberk [online]. https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/cs/index.jsf?page=profil-uzemi&uzemiprofil=31548&u=__VUZEMI__65__7110#

- DRAW.IO. (2019). Retrieved from: https://about.draw.io/

- Drbohlav, D. (1991). Mentální mapa ČSFR: Definice, aplikace, podmíněnost. Sborník České Geografické Společnosti, 96(3), 163–176.

- ESFR. (2015). Analýza sociálně vyloučených lokalit v ČR [online]. https://www.esfcr.cz/mapa-svl-2015/www/index2f08.html?page=iframe_orp

- Ghioca, S. (2014). The cognitive map's role in urban planning and landscaping: Application to Braila city, Romania. Cinq Continents, 4(10), 137–157.

- Golledge, R. G., & Stimson, R. J. (1997). Spatial behavior: A geographic perspective. Guilford Press.

- Gould, P., & White, R. (1993). Mental maps. Routledge.

- Ježek, J. (2004). Aplikovaná geografie města. University of West Bohemia.

- Jim, C. Y., & Chen, W. Y. (2006). Perception and attitude of residents toward urban green spaces in Guangzhou (China). Environmental Management, 38(3), 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-005-0166-6

- Krevs, M. (2004). Perceptual spatial differentiation of Ljubljana. Dela, 21(21), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.4312/dela.21.371-379

- Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. The MIT Press.

- MICR. (2019). Počty obyvatel v obcích [online]. https://www.mvcr.cz/clanek/statistiky-pocty-obyvatel-v-obcich.aspx

- National Heritage Institute. (2015). Městská památková zóna Šternberk [online]. https://pamatkovykatalog.cz/pravni-ochrana/mestska-pamatkova-zona-sternberk-84597

- Osman, R. (2016). Sémantická mapa: Příklad Ústí nad Orlicí. Geografie, 121(3), 463–492. https://doi.org/10.37040/geografie2016121030463

- Pánek, J. (2019). Mapping citizenś emotions: Participatory planning support system in Olomouc, Czech Republic. Journal of Maps, 15(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2018.1546624

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. Annals Of The Association Of American Geographers, 67(4), 622–624.

- Ruan, X., & Hogben, P. (Eds.). (2007). Topophilia and topophobia: Reflections on twentieth-century human habitat. Routledge.

- Siwek, T. (2011). Percepce geografického prostoru. Czech Geographical Society.

- Stasíková, L. (2013). Genius loci vo vzťahu k strachu zo zločinnosti na príklade postsocialistického sídliska. Geografický Časopis, 65(1), 83–101.

- Stein, A. L. (2017). Comparative urban land use planning: Best practice. Sydney University Press.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1975). Images and mental maps. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 65(2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1975.tb01031.x

- Vaughn Kelso, N., Patterson, T., Furno, D., Buckingham, T., Buckingham, B., Springer, N., Cross, L., Zillmer, S., Haggit, C., Bennett, S., Coakley, B., McGrath, K., Klass, R., Maarel, H., Robertson, B., Karklis, K., Molyneaux, C., Goulet, F., Saligoe-Simmel, J., Buckley, A. (2019). Natural earth [online]. https://www.naturalearthdata.com/

- Vazquez-Barquero, A. (2002). Endogenous development, networking, innovation, institutions and cities. Routledge.