ABSTRACT

The article concerns the utilisation of existing cartographic materials and spatial databases for an analysis and visualisation of changes in land usage which occurred in the Noteć Forest. From the year 1700, small settlements began to spring up on these lands, established on the basis of the so-called ‘olęderskie law' (‘Dutch’ law, specific name to Poland). Geopolitical, and later economic conditions caused these colonies to lose importance and gradually die off. Presently, these are in the main ruins. The land use changes are visible on maps which were drawn in various years. These changes have been researched using numerous different cartographic sources and visualised for both the entire Noteć Forest and selected townships, with particular emphasis being given to Radusz. The study makes use of archival and contemporary Polish topographic maps and archival German Messtischblatter maps.

1. Introduction

Changes in land usage in the Noteć Forest were primarily the result of settlement based on ‘Dutch law’, which commenced in the area in the seventeenth century (Rusiński, Citation1947). As a colonising movement in Wielkopolska [Greater Poland], this form of settlement continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Initially, the term ‘olęders’ (the ‘Dutch’) was used to describe settlers from the Netherlands, Flanders and Frisia, usually of the Mennonite faith, who emigrated to Poland due to difficult living conditions and religious persecution in their homelands (Klassen Pater, Citation2002; Targowski, Citation2016).

The beginnings of Dutch colonisation began in the 12th century in present day Germany. Since the 16th, settlers from Frisia and the Netherlands established their villages in the Prusy Książęce [Duchy of Prussia] and Prusy Królewskie [Royal Prussia (Polish Prussia)], then along the Wisła River and its tributaries and in Kujawy, Wielkopolska and Mazowsze (Ratzlaff, Citation1971). In the seventeenth century, they appeared near Warsaw, and then in the Lublin region and Volhynia (Kneifel, Citation1971). At that time, this type of settlement was quite common. The villages assumed included mainly uninhabited areas, difficult to cultivation (wetlands, forests).

In later years (until the mid-nineteenth century), the term ‘olęders’ was applied to immigrants of various ethnic nationalities (mainly Poles and Germans, sometimes Scotts, Czechs and Hungarians) who enjoyed certain privileges under the law of the Frisian and Netherlandish colonists. In accordance with the principles of ‘olęderskie law’ appearing in the feudal contracts of colony founders, which were concluded with entire communes, the ‘olęders’ enjoyed personal freedom and used land on the basis of a long-term renewable lease, and later also held it in perpetual lease (Przewoźny & Przewoźny, Citation2009). Further, they retained their own religion and beliefs, as well as the right to pass on their land to their inheritors. Residents were entitled to their own self-government, while the most significant feature of this type of settlement was the joint and several liability of the commune for duties with respect to the landowner (Szałygin, Citation2002). Such colonies were distinguished by aspects of law, and not through nationality, ethnicity, or religion.

In the years 1527−1864, at least 1,700 ‘olęder’ communities were established in, first, the Polish Commonwealth (pl. I Rzeczpospolita), and after 1795, in the three partition zones; of these, approximately 300 were settled by ethnic Dutchmen (Chodyła, Citation2001). This colonisation type was characterised by a specific form of architecture, which was influenced by the area on which a settlement was established − compact Zeilendorfs sprang up along rivers and canals, while forested areas were the location of scattered farmsteads. A typical ‘Dutch’ homestead would normally comprise three buildings − a single-storey hut, a barn, and outbuildings (Wrona & Rek, Citation1998).

In Wielkopolska, the ‘Dutch’ colonisation was completely agricultural in nature, and formally ceased to exist as such in 1823. According to Rusiński (Citation1947), approximately 550 settlements were established in the region, while more recent research conducted by Chodyła (Citation2001) indicates that there were some 700 in total. Villages were founded in the vicinity of Nowy Tomyśl, Gostyń, Środa Wielkopolska, Śrem, Pyzdry, Skwierzyna, Międzyrzecz, Wolsztyn, Oborniki, and within the Zielonka Forest and the Noteć Forest. These villages were scattered throughout the forests, and oftentimes comprised only isolated farmsteads. Basically, they were established in order to clear the forests and reclaim wastelands. Lands belonging to individual homesteads were consolidated, and their shape resembled a square or a polygon. Homes and outbuildings were usually located in the centre of these lands. Farmers connected their houses with the main road by means of separate paths.

Today, traces of settlement are visible in rural architecture, the spatial arrangement of villages, and the names of townships (Kusiak, Citation2013). The following are some of the colonies established on ‘Dutch Law’ in the vicinity of the Noteć Forest (Przewoźny & Przewoźny, Citation2009): Rąpin (1747), Grotów (1702), Sowia Góra (1702), Mierzyn (1695), Mierzynek, Piłka and Zamyślin (1713), Radgoszcz, Zwierzyniec, Zatom (1751), Chorzępowo (1753), Bucharzewo, Bukowiec (1722), Bukowce (1691), Lubowo (1764) and Popowo (1768).

The first, most well known and largest village to be established on ‘Dutch’ law in the Noteć Forest, in around the year 1700, was Radusz. This township forms the focus of the present study, and the spatial layout of forms of land usage – which underwent a complete change between the 18th and the twentieth century – has been researched in depth.

A study of the spatial distribution of settlement units is made possible, among others, by cartographic sources in the form of archival (Plit, Citation2006; Szady, Citation2018) and contemporary topographic maps, a rich body of which is extant for the Noteć Forest.

Cartographic analyses of selected topographic objects located in the Noteć Forest have already been previously undertaken by the authors of the present paper. One such investigation, carried out in the years 2010–2014, centred on the location of the shoreline of selected lakes on archival maps, which was then compared with the presently existing state, obtained on the basis of GNSS measurements (Ławniczak & Kubiak, Citation2016).

2. Study area

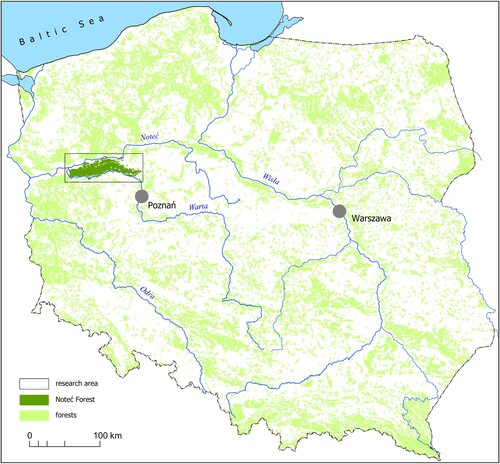

The aim of the study was to trace changes in the settlement network in the Noteć Forest on the basis of cartographic sources. The Noteć Forest () forms a compact and vast wooded complex – one of the largest in Poland – with an area of approximately 1,372 km2. It is situated in the Gorzów Basin, which itself is part of the Toruń-Eberswalde Glacial Valley. The area is overgrown mainly with pine stands, sporadically interspersed with small birch stands, which occupy the poor sandy habitats located on outwashes and inland dunes. The weak soils, primarily podsols, make it difficult to introduce more varied stands. These areas are valuable in natural terms. Presently, nearly the entire Noteć Forest is situated within a ‘Natura 2000’ special protection area, and its forest lands have been in large part subjected to landscape protection. It is also home to a great number of nature reserves.

The area stretches latitudinally along more than 100 km from Santok and Skwierzyna in the west to Oborniki and Rogoźno in the east, and to Czarnków in the north-east. Other larger townships situated on the fringes of the Noteć Forest include Międzychód, Drezdenko, Sieraków, Wieleń and Wronki. The area of the Noteć Forest is currently one of the least populated regions of Poland.

The forest areas are located between the rivers Warta and Noteć were chosen as the borderline for the study area. Its eastern boundary is delimited by the Wełna River ().

3. Materials and methods

The cartographic analysis of changes in the settlement network in the Noteć Forest and in land usage in the vicinity of the township of Radusz was based on a comprehensive store of archival and contemporary cartographic sources. This comprised the following topographic maps:

Urmesstichblatter, issue 1832;

Messtischblatter, on a scale of 1:25,000 (1934–1935);

WIG (Military Geographical Institute) Topographic Map, on a scale of 1:25,000 (1931–1934);

Topographic Map of the Military Geographical Institute, on a scale of 1:100,000 (1934);

Topographic Map (General Staff Topographic Board), on a scale of 1:25,000 (1964);

Topographic Map, on a scale of 1:50,000 coordinate system 1965 (1977);

Topographic Map, on a scale of 1:10,000 coordinate system 1965 (1991);

Topographic Map, on a scale of 1:50,000 coordinate system 1992 (1998).

Contemporary topographic maps are further supplemented with sources made available in numerical form and with data for selected environmental components. These include:

VMap Level2, on a scale of 1:50,000 (2003);

BDOT 10k (Database of Topographic Objects), on a scale of 1:10,000 (2013);

NML (Numerical Forest Map), on a scale of 1:10,000 (2017).

Research tasks consisted of gathering available source data and performing their necessary elaboration. A field inspection was also conducted, this consisting of the verification of the chosen objects that had been identified on archival maps.

The research procedure was based on the cartographic method, supplemented with field studies and measurements. The author of the term is Saliszczew (Citation1955), according to whom its essence consists of the incorporation into the process of researching reality of an intermediate link – the geographical map – as the model of analysed phenomena. A development of the cartographic method of research is the geomatic method, which in the opinion of Kozieł (Citation1997) provides research with support through the automatic performance of operations on spatial data.

All archival and contemporary maps were converted to the PUWG 1992 system of coordinates that is currently in force in Poland for topographic and thematic maps, and which is based on the GRS 80 ellipsoid, in the Gauss-Krüger single zone projection with the central meridian of zone 19°. Maps were provided with georeferences in the form of geographical coordinates. The reference points adopted for the Messtischblatter and Military Geographical Institute topographic maps were selected characteristic situational elements, which were identified both on the map and in the field. These operations on the aforementioned archival maps were necessary due to the fact that they made use of projections and ellipsoids different from those currently applicable in Poland for topographic maps. This resulted in a specific distribution of deformations and in slight shifts of the cartographic grid. Issues concerning the calibration of historical maps have been discussed, among others, by Guerra (Citation2000), Affek (Citation2012) and Panecki (Citation2014).

Since these maps were drawn many years ago and the land had changed considerably since then, the task was made additionally difficult. The sole control points that could be applied were characteristic crossroads, bridges, culverts, the existing fencing of old cemeteries, sacred buildings, extant structures erected at the time the maps were drawn, and topographic elevation points. Measurements of the geographical coordinates of these points were performed using GNSS technology. The determination of coordinates for the control points made it possible to provide these maps with georeferences. The same procedure was applied for topographic maps of the General Staff Topographic Board from 1964, the civilian versions of which – due to the period in which they were drawn – had been censored. Namely, these maps had their cartographic grids and grids of topographic coordinates removed.

The necessity of converting coordinates from the 1965 system to the 1992 system was brought about by the differences between existing systems compared with Krassowski’s ellipsoid and the new system of spatial references compared with the GRS-80 ellipsoid (Kadaj, Citation2000, Citation2002). The theory of Polish systems of coordinates provides very precise formulae for the defined projections and mathematical relations between individual systems, including those originating from various ellipsoids of reference.

The sole type of conversion permitted to be used when recalculating coordinates between the 1965 system and that of 1992 is the 4-parameter flat conformal transformation (similarity transformation) with the removal of deviations at reference points by means of Hausbrandt’s method (Technical Instruction G-2, Citation2001). The recalculation procedure, which comprised four stages, was performed using the C-Geo geodetic programme:

projection of flat coordinates xy in the 1965 system to BL geographical coordinates on Krassowski’s ellipsoid,

The 7-parameter Helmert transformation of spatial coordinates XYZ (BLH) from the 1942 system (Krassowski's ellipsoid) to the EUREF-89 system (GRS-80 ellipsoid),

projection of BL geographical coordinates on the GRS-80 ellipsoid into flat coordinates xy in the Gauss-Krüger projection for the 1992 system,

4-parameter flat conformal transformation with the removal of deviations at reference points by means of Hausbrandt’s method.

The procedure undertaken made it possible to compile all of the used maps – archival, contemporary, analogue and numerical – into a single uniform system. Selected elements of the contents of each analogue map were digitised. This enabled comparative research and quantitative analyses of selected forms of land use from the interwar period to the present day.

4. Map of ‘Changes in the settlement network in the Noteć Forest in a historical perspective’

The map, which constitutes an attachment to the present study, was made using the PUWG-1992 system (in force in Poland for topographic and thematic maps) in the Gauss-Krüger projection, which for the purposes of the present paper was modified by the adoption of 15°50′ as the central meridian of the projection zone, for which the scale factor is equal to 0.9993. This made it possible to obtain a cartographic image free of the ‘deviation’ brought about by the location of the study area on the border of the zone. This helped minimise projection deformations and facilitated the performance of editorial work.

The main objective of the map is to present the changes which occurred in the distribution of built-up areas in the Noteć Forest. The comparison concerned the reach of building development in the years 1931–1935 and in the present day. During the interwar period (1919–1939), the study area was bisected by the Polish-German border. Built-up areas were presented on the basis of Messtischblatter maps drawn for German lands on a scale of 1:25,000, and of maps of the Military Geographical Institute – on a scale of 1:25,000 – for Polish lands; thus, the structure of building development is pre-1939. In order for the study to constitute a uniform whole, the following were marked on the map: forests, cemeteries, main railway lines, main roads, rivers and larger lakes. The Polish-German border from the years 1919–1939 was also marked. The basic element of contents, namely built-up areas, were presented in two variants. A dark brown colour was used to mark those which no longer exist. Building structures that have survived to our times were marked with a light brown colour. A significant element of the infrastructure of housing estates in the study area were cemeteries. They ceased to fulfil their functions along with the disappearance of settlement. Frequently, they were reclaimed by the forests. Their traces, however, are still visible in the land, and some are even marked on modern-day cartographic materials. Cemeteries designated on archival maps that no longer exist in their original form were distinguished in dark green, while those that are still extant and continue to fulfil their functions – in light green.

The verification of built-up areas and cemeteries was conducted on the basis of contemporary topographic maps on a scale of 1:10,000 and of field research, which took place between March 2018 and July 2019. Built-up areas that came into being after 1945 were not marked on the map. In the Noteć Forest, this phenomenon is marginal only, nevertheless it should be stressed that townships located on the fringes of the study area have grown sizeably (they do not, however, form the subject of the present study).

In addition, 13 frames in which changes in the settlement network are most noticeable were also distinguished on the map. These are the following townships: 1. Mąkoszyce, Baranowice, 2. Jezierce, 3. Smolarnia, 4. Koza, 5. Krzęcinek, 6. Radusz, 7. Ociesze, 8. Dębowiec, 9. Zieleniec, 10. Bronice, 11. Kobusz, 12. Bielawy, 13. Ludomicko. Fragment of sheets beneath the main presentation juxtapose images of archival maps with those of contemporary plans of these areas. These enable a visual analysis of the changes which occurred in the structure of the settlement network and other forms of land use.

5. Cartographic visualisation of changes in land use the vicinity of the village of Radusz

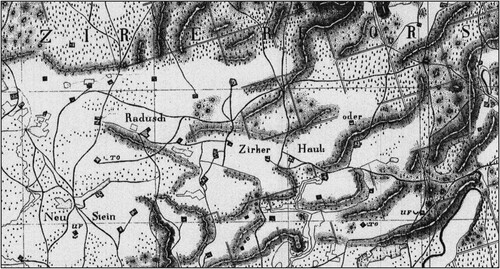

The township of Radusz is a special area in the Noteć Forest. The village was settled by Germans, Czechs and Poles from Lower Silesia. In its period of greatest prosperity, the colony numbered 700 residents. Apart from some 90 homesteads, the immigrants erected a church, pastor’s residence, school, post office, mills and inns; they also built two cemeteries. Individual farms occupied from 80 to as many as a few hundred hectares (Kusiak & Dymek-Kusiak, Citation2002). For the largest township located in the Noteć Forest (main map: ‘Changes in the settlement network … ’, frame no. 6) the authors performed a detailed analysis of the structure of changes in land use on the basis of all available cartographic sources. The arable land, meadows and pastures, forests, built-up areas and cemeteries were analysed. In the years 1793–1918, the lands of this part of Poland (Grand Duchy of Posen) – including the Noteć Forest – were in the Prussian partition zone. One of the first topographic maps of the area where the village of Radusz presented was on the map Prussian Urmesstischblatter von Preuβen, on a scale of 1:25,000. It was made in 1832. A fragment of folio containing the study area has been presented in .

Figure 3. Areas of the village of Radusz presented on the Urmesstischblatter von Preuβen map from 1832.

Research conducted by Lorek and Medyńska-Gulij (Citation2020) has shown that this map is not a fully cartometric image. The issue of older topographic maps has also been noted by Czerny (Citation2015), who stated that it is connected with the problem of georeferences and conversion to contemporary systems of coordinates. Many historical maps are of insufficient precision, and it is impossible to determine the cartographic projection or the ellipsoid of reference.

Apart from the abovementioned drawbacks of these maps, we can see on the attached fragment that there is no clear delimitation between the analysed types of land use. In consequence, the map was omitted from quantitative research determining the share of individual forms of use. Furthermore, the map does not present the complete infrastructure of the township, for its period of greatest development occurred in later years.

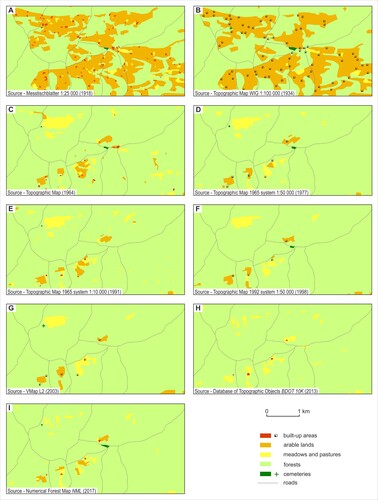

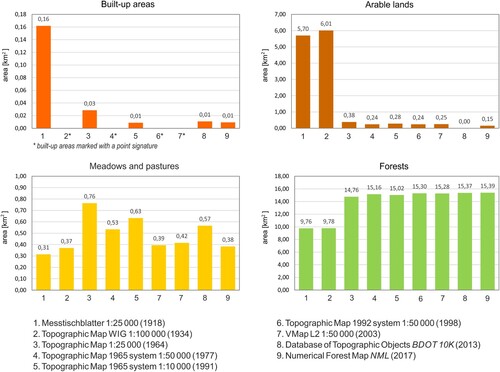

The first study concerning this area which fulfils all of the standards of a topographic map is the Messtischblatter. Its first version comes from the year 1893. (A) presents the usage of land for the township of Radusz in vectorised form from the period of its greatest development on the basis of the Messtischblatter from 1918.

Following the period of partitions, in 1919, Radusz found itself in Poland. At the time, some of the Germans living there refused to accept Polish citizenship and left the area. During the interwar period, Radusz continued to grow, taking advantage of its location on the Polish-German border (it housed a first-line station of the ‘Radusz’ Border Guards) and maximising profits from forestry. The structure of land use in this period has been presented in (B), elaborated on the basis of a map of the Military Geographical Institute from 1934. A slight increase in the area of forests may be determined. Building development, due to the fact that it was scattered and because of the map’s scale of 1:100,000, has been presented in the map in signature form, and thus it is not possible to calculation its area. This edition of the map is distinguished by its advanced cartographic level; as Nita and Myga-Piątek (Citation2012) have noted, these maps are characterised by a high degree of detail and precision of projection of land topography, and thus constitute a very valuable document for the study, among others, of changes in spatial management.

During the Second World War, already in 1940, the Germans liquidated the village and evicted all its residents, transforming the area into hunting grounds for dignitaries of the Third Reich (Anders & Kusiak, Citation2005). Residents of German nationality received farmsteads on other occupied Polish lands, while Poles were deported for forced labour to the Reich. In 1942, the demolition of buildings was commenced. After the War, the village was not rebuilt. Bricks from the surviving structures were used for the reconstruction of war damage in neighbouring townships. Today, the few surviving homesteads function as foresters’ lodges. What remains of the village are foundations, fragments of brick lined roads, filled in wells, fruit trees standing in the pine forest, and cemeteries.

The first post-war topographic map of the area was made available for civilian use in 1964. It was used as the basis for a map ((C)) on which we can clearly see the results of the afforestation of previously agricultural lands and the considerable contraction of built-up areas. The progression of this process is illustrated by topographical maps from the years 1977–1998 ((D,E,F)). Data presented on the VMap L2 numerical map from 2003 ((G)) are the reflection of earlier analogue plans. The contemporary structure of land use has been shown in maps from the years 2013–2017 ((H,I)). The share of forested landmass continues to grow at the expense of agricultural land.

The vectorisation of analogue source maps and the contemporary numerical maps have made it possible to gather quantitative data. A determination has been made of area of analysed forms of land use, which have been presented in the form of charts in . It was not possible to determine built-up areas on the basis of certain maps. This is due to their smaller scale and the application of point signatures. A slight increase in built-up areas has been observed in some localities in the Noteć Forest in recent years. It is related to the development of recreational construction.

6. Results and conclusions

The field inspection conducted has allowed us to ascertain that contemporary cartographic sources, on the whole, faithfully reflect actual conditions as regards the occurrence and scope of individual forms of land use. They may well be used for spatial analyses and in research into the natural environment, providing reliable and commonly available quantitative data.

Within the analysed area we can observe changes characterised by a decrease in the share of arable land, meadows and pastures and a concomitant increase in forested land, which development was to a large extent impacted by geopolitical determinants.

Rusiński (Citation1947) claims that the arrival of colonists from the Netherlands gave impetus to the development of agriculture and breeding. Settlement processes in the Noteć Forest area weakened in the nineteenth century. After 1918, there was a slight outflow of German population from the areas within Polish borders. Many towns and settlements fell during the German occupation (1939−1945) as a result of forced deportations. After 1945, the vilages in the depths of the forest which were in decline were considered unattractive in economic and settlement terms. Settlements such as Jezierce, Smolarnia, Koza, Krzęcinek, Radusz, Ociesze, Bronice, Kobusz, Bielawy and Ludomicko have become depopulated and have largely or completely disappeared. At present, the economic and settlement development of the area is to some extent limited by its location within the ‘Natura 2000’ protected area. There are no investments that would have a negative impact on particuler habitats and natural species. The development of recreational construction in the Noteć Forest is small. The towns located in the Noteć and Warta Valleys are much more developed.

An analysis of archival and contemporary cartographic studies supports a critical view of the possibility of utilising available source materials. We may point out both their advantages and disadvantages, which allows for a proper selection of cartographic studies for selected types of research work.

The rich resource of cartographic source materials has enabled tracking of land use changes that have taken place over the last 100 years. However, topographic analyses of archival maps bring with them certain problems as regards a quantitative analysis. The oldest maps are characterised by a lack of cartometricity. Later works, created even before 1939, used cartographic projections and reference ellipsoids different than those applied today. This requires a broader range of actions aimed at connecting spatial data into a cohesive system.

The research results presented may be used in works focusing on cultural heritage protection and promotion of the region, and also in studies devoted to spatial planning and protection of the natural environment.

Software

At the stage of map calibration, transformation of systems of coordinates, elaboration of numerical layers, figures and the final map (which has been presented as a separate attachment), use was made of the following programmes: MapInfo Pro 12.5, CorelDRAW X6, Adobe Photoshop CS5.1 and C-Geo8.

Changes_in_the_settlement_network_after_revision.pdf

Download PDF (27.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Affek, A. (2012). Kalibracja map historycznych z zastosowaniem GIS [in:] Źródła kartograficzne w badaniach krajobrazu kulturowego. Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego, 16, 48–62.

- Anders, P., & Kusiak, W. (2005). Puszcza Notecka. Przewodnik krajoznawczy. Oficyna wydawnicza G&P.

- Chodyła, Z. (2001). Zarys osadnictwa olęderskiego w Polsce od XVI do XVIII w. [in:] Olędrzy i ich dziedzictwo w Polsce. Historia, stan zachowania, ochrona. Toruń. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from http://holland.org.pl

- Czerny, A. (2015). Dawne mapy topograficzne w badaniach geograficzno-historycznych. Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

- Guerra, F. (2000). New technologies for the georeferenced visualization of historic cartography. [in:] International Archives of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, XXXIII, port B5: 339–346.

- Kadaj, R. J. (2000). Zasady transformacji współrzędnych pomiędzy różnymi układami kartograficznymi na obszarze Polski. Rady na Układy. Geodeta, 9, 64.

- Kadaj, R. J. (2002). Polskie układy współrzędnych. Formuły transformacyjne, algorytmy i programy. AlgoRessoft.

- Klassen Pater, J. (2002). Ojczyzna dla przybyszów: wprowadzenie do historii mennonitów w Polsce i Prusach. Tłum.: Borodin A., ABORA, Warszawa.

- Kneifel, E. (1971). Die evangelisch − augsburgischen Gemeinden in Polen 1559-1939. Vierkierchen.

- Kozieł, Z. (1997). Concerning the need for development of the geomatic research method. Geodezja i Kartografia, 46(3), 217–214.

- Kusiak, W. (2013). Geograficzne, przyrodnicze, gospodarcze, rolnicze, historyczne i inne nazwy z obszaru Puszczy Noteckiej. Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej, 12, 61–72.

- Kusiak, W., & Dymek-Kusiak, A. (2002). Puszcza Notecka monografia przyrodniczo gospodarcza. Wydawnictwo Przegląd Leśniczy.

- Ławniczak, R., & Kubiak, J. (2016). Geometric accuracy of topographical objects at polisch topographic maps. Geodesy and Cartography, 65(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1515/geocart-2016-0003

- Lorek, D., & Medyńska-Gulij, B. (2020). Scope of information in the legends of topographical maps in the nineteenth century – Urmesstischblätter. The Cartographic Journal, https://doi.org/10.1080/00087041.2018.1547471

- Nita, J., & Myga-Piątek, U. (2012). Rola GIS w ocenie historycznych opracowań kartograficznych na przykładzie Wyżyny Częstochowskiej [in:] Źródła kartograficzne w badaniach krajobrazu kulturowego. Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego, 16, 116–135.

- Panecki, T. (2014). Problemy kalibracji mapy szczegółowej Polski w skali 1:25 000 Wojskowego Instytutu Geograficznego w Warszawie. Polski Przegląd Kartograficzny, 46(2), 162–172.

- Plit, J. (2006). Analiza historyczna jako źródło informacji o środowisku przyrodniczym. Regionalne Studia Ekologiczno-Krajobrazowe, PEKT, 16.

- Przewoźny, J., & Przewoźny, W. (2009). Szlakiem olędrów w północnej Wielkopolsce. Wydawnictwo Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna i Centrum Animacji Kultury.

- Ratzlaff, E. L. (1971). Im Weichselbogen Mennonitensiedlungen in Zentralpolen.

- Rusiński, W. (1947). Osady tzw. “Olędrów”w dawnym województwie poznańskim. Polska Akademia Umiejetności. Kraków, 132–143.

- Saliszczew, K. A. (1955). O kartograficzeskom mietodie isslidowania. Wiestnik Moskowskogo Uniwirsitieta. Sieria fiziko-matiematiczeskaja, 10.

- Szady, B. (2018). Dawna mapa jako źródło w badaniach geograficzno-historycznych w Polsce [in:] Kwartalnik historii kultury materialnej, 66, 2: 129-142, Warszawa.

- Szałygin, J. (2002). Kolonizacja “olęderska”w Polsce − niedoceniany fenomen. Opcja na Prawo, 7–8.

- Targowski, M. (2016). Osadnictwo olęderskie w Polsce − jego rozwój i specyfika [in:] Olędrzy − osadnicy znad Wisły. Sąsiedzi bliscy i obcy. Fundacja Ośrodek Inicjatyw Społecznych ANRO.

- Technical Instruction G-2. (2001). Szczegółowa pozioma i wysokościowa osnowa geodezyjna i przeliczenia współrzędnych między układami. Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii.

- Wrona, J., & Rek, J. (1998). Podstawy Geografii Ekonomicznej. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne.