ABSTRACT

International Retirement Migration (IRM) is a growing phenomenon in the Global South. Using the example of the city of Cotacachi in the Ecuadorian Andes, this paper analyzes the spatio-temporal growth of the properties acquired by foreign retirees. We have developed a multi-temporal map that visualizes the spatio-temporal patterns of foreign-owned real estate properties and explains them in the historical context of land tenure. As no official spatial data is available for foreign-owned properties in Cotacachi, the mapping was developed based on data triangulation from remote sensing, participatory mapping, document analysis (e.g. a cadastral database), and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders. With this origin approach, the map reveals a significant growth in the number of properties and the size of the land acquired by foreigners particularly since the 2008 United States’ housing crisis. Most of the foreign-owned properties are located at the urban fringe and have been built on former colonial hacienda lands in direct proximity to existing indigenous communities.

1. Introduction

International Retirement Migration (IRM) is a growing phenomenon in the Global South and Ecuador is considered one of the best destinations for retirement. The American magazine International Living has ranked the country as one of the top 10 places to retire in the world for consecutive years (CitationInternational Living, Citation2021, Citation2022). Andean cities such as Cotacachi, Cuenca, and Vilcabamba are among the main destinations of IRM, partly due to comparatively affordable housing prices, the low cost of living, and excellent climatic conditions.

Existing research on IRM and its impacts have focused mainly on Europe and the United States, where this process has been ongoing for decades (CitationBlasco Peris, Citation2009; CitationCasado-Diaz, Citation1999; CitationHuete, Citation2008; CitationMembrado, Citation2015). However, recent studies have been carried out in Latin American countries, such as Mexico (CitationBastos, Citation2013; CitationLizárraga, Citation2010; CitationMonterrubio et al., Citation2018; CitationSloane & Silbersack, Citation2020), Costa Rica (CitationJanoschka, Citation2011; CitationVan Noorloos & Steel, Citation2016), Panama (CitationBenson, Citation2013) and Brazil (CitationPontes da Fonseca & Janoschka, Citation2018).

The impacts of IRM are diverse. IRM generates a sharp increase in property prices (CitationHuete, Citation2008; CitationLizárraga, Citation2010); land speculation (Citationvan Noorloos, Citation2013), territorial dispossession and gentrification (CitationBastos, Citation2013; CitationHayes, Citation2016, Citation2020; CitationJanoschka, Citation2011), social segregation (CitationCasado-Diaz, 2016; CitationGustafson, Citation2016), etc. Some scholars have also pointed out positive aspects; including the generation of employment, tax contribution, and new service sectors (CitationHuete, Citation2008; CitationTorres Bernier, Citation2003).

Despite the existence of several studies that analyze the impacts of IRM in Latin America as mentioned above, few studies exist for the Andean region of Ecuador. Some scholars have focused particularly on analyzing the economic and social impacts of retiree migration in cities such as Cuenca and Vilcabamba, where this migration process has been going on for many years (CitationEfird et al., Citation2020; CitationHayes, Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2020; CitationSloane & Silbersack, Citation2020; CitationVan Noorloos & Steel, Citation2016). However, due to the recent history of this phenomenon in the city of Cotacachi, this issue has not yet been addressed considerably. In addition, only few studies have examined the issues of IRM in the context of land foreignization in colonial hacienda histories (CitationGascón, Citation2015, Citation2016; CitationHayes, Citation2016, Citation2018). Focusing on the city of Vilcabamba, CitationHayes (Citation2016) analyzes how lifestyle migration drives foreign real estate investment and relates it to the historical control of land by a powerful landowning elite. According to him, this development has a significant effect on the local population, culminating in gentrification. Similarly, CitationGascón (Citation2015) for the case of Cotacachi, pointed out that ‘this phenomenon causes land speculation processes that threaten peasant reproduction strategies and that contribute to depeasantisation and rural migration’ (Citation2015, p. 4). In sum, foreign-local contestation over land emerges as a key problem of IRM. However, none of the existing studies map and quantitatively demostrate the spatio-temporal growth of foreign-owned properties since 2008 and explain it in the colonial historical context of land tenure.

For this purpose, the map and this article follow two specific objectives: first, to map and quantify the number of properties and the amount of land acquired by foreigners in the city of Cotacachi for the last three decades (1990–2019). Second, explain the spatio-temporal patterns of foreign-owned property growth in the context of the historical background of land tenure. This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the historical process of land tenure in Cotacachi and the emergence of a new foreign real estate market. Section 3 details the data and cartographic methods used for the mapping of foreign-owned properties and indigenous communities. Section 4 shows the results obtained through these methods and finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions.

2. Land tenure in Cotacachi: from colonial haciendas to foreign real estate investment

Understanding which land is sold and which actors are involved in selling land for foreign-owned residential complexes requires a look back into the colonial history of land tenure. In Cotacachi, at least three key historic moments can be identified: (i) the predominance of large colonial haciendas; (ii) the fracture of the hacienda system; (iii) the agricultural land market for foreign retirees.

Large haciendas existed from colonial times until the beginning of the Republic of Ecuador and were characterized by strong processes of territorial control and indigenous labor exploitation under the system known as huasipungo. Derived from the Quechua words huasi, ‘house,’ and pungo/pungu, ‘door.’ Under this colonial system, the hacienda owners forced indigenous people to work on their haciendas. In exchange for their labor, they were given the right to cultivate small plots of land on the hacienda (called huasipungos), as well as the right to collect firewood and use the hacienda's water (CitationRhoades, Citation2006). However, although they cultivated and lived on these plots, the land did not belong to them as they were only given a right to use. As a result, the land of the haciendas was spatially divided: (1) the land cultivated directly by the hacienda owner and (2) the land used by indigenous families for their own interest; the latter generally being of lower quality and located on hillsides (CitationGuerrero, Citation1975).

As a result of the agrarian reforms of 1964 and 1973, the hacienda system became fractured and the huasipungos were eliminated (CitationCamacho, Citation2006). The reforms aimed to promote a more equitable land distribution through the state expropriating and dividing the large haciendas. However, the results were not as expected (Guerrero & Ospina, 2003]; quoted in CitationOrtiz Crespo, Citation2004). Many of the haciendas maintained their extensive lands (CitationBrown et al., Citation1988). Historical data on land tenure shows that 1.1% of landowners controlled about 60% of the agricultural land in 1974 (CitationGuerrero, Citation2004).

During the 1980s and 1990s, land tenure was characterized by the fragmentation of large properties as land was sold by hacienda owners to generate funds to modernize their haciendas (e.g. purchasing agricultural machinery, fertilizers, livestock, etc.). In addition, in 1994 an ‘Agricultural Development Law’ was passed, which liberalized land title and registration laws, making land sales easier (CitationPastor, Citation2014, pp. 45–46). This allowed hacienda owners to sell land to outsiders who had no previous connection to ongoing and contentious land claims.

Finally, in recent years, the influx of foreign retirees to the city has triggered a strong real estate market, mainly oriented to the sale of agricultural land for IRM-related real estate. In most cases, parts of the remaining land of the colonial haciendas were sold to real estate agents who developed a series of residential complexes or gated communities in different areas (CitationQuishpe & Alvarado, Citation2012). Three key factors have motivated the strong increase of IRM to Cotacachi: first, the US economic and financial crisis of 2008 affected the financial security of many older adults, which led them to search for better retirement conditions in countries with lower costs of living (CitationHayes, Citation2013, p. 6). Second, a tourism development policy promoted by the municipality in previous years, based on tourist attractions (CitationGascón, 2016). Third, strong international promotion by some companies specialized in retirement destinations and by U.S. residents through online forums highlighting favorable living conditions for elderly people for relatively little money, including low-cost healthcare and access to the Ecuadorian Social Security System, as well as specific discounts on taxes and transportation costs.

Additionally, no restrictions exist on foreign real estate investment in Ecuador. In fact, anyone can freely buy property in Ecuador upon their arrival using only their passport. Ecuador's constitution guarantees everyone the right to buy and hold property. These conducive conditions are clear comparative advantages for Ecuadorian destinations of IRM compared to other countries applying restrictions on foreign real estate investment.

3. Materials and methods

3.1 Study Area

Cotacachi is a rural canton, located in northern Ecuador, in Imbabura Province, about 80 kilometers from the capital's airport (Quito). It has a population of 40,036 inhabitants, with approximately 8,800 living in the city (CitationINEC, 2010). The main economic activities are agricultural production, leather manufacturing and tourism (CitationPDOT, Citation2015). The canton is divided geographically in three zones (the urban zone, the subtropical zone and the Andean zone) and is inhabited by different ethnic groups. 53.5 percent of the population self-identifies as mestizo, 40.5% as indigenous and 2.5% as white (CitationINEC, 2010). This study focuses on the urban area and the so-called Andean zone, the latter characterized by the high presence of an indigenous population and where, since the last decade and half, a strong real estate development of foreign properties has been observed.

IRM to the city of Cotacachi in the Ecuadorian Andes only kick-started in 2009, shortly after the US economic and financial crisis (CitationViteri, Citation2015). Today, about 1,000 foreign pensioners live in the city (CitationEl Telégrafo, Citation2017). However, this is an approximate figure, as there is no census data for migrants. As CitationHayes (Citation2013) states, it is difficult to have exact figures for migrants arriving in countries such as Ecuador, because many foreign citizens do not require a visa to visit Ecuador and also because these types of migrants tend to move around constantly or return to their countries of origin. Most of them are low-income pensioners of U.S. origin (CitationViteri, Citation2015). But they also come from other countries, such as Canada, France, Germany and Australia in smaller numbers (CitationCrespo, Citation2014).

Since the arrival of the foreign retirees, a wide range of residential projects ranging from stand-alone houses, townhouses, or condominium units have been developed in the city. Most of these properties include a full range of services and amenities such as large green spaces, access to communal areas or gardens, 24-hour private surveillance, security cameras, etc. The foreign-owned residential complexes in Cotacachi (see photo 1), thus, clearly differ in terms of their amenities and their architectonical structure from the generally self-built houses in the neighboring indigenous communities (see photo 2).

Photo 1. Residential condominium complex for foreign retirees (The House of Dreams). Source: Quantum Real Estate. Available: https://www.plusvalia.com/propiedades/cotacachi-hermoso-departamento-en-venta-en-segundo-59639462.html

Photo 2. Typical model of a dwelling in one of the indigenous communities. Source: Field visit, October 2020.

3.2 Mapping the spatio-temporal patterns of foreign-owned properties

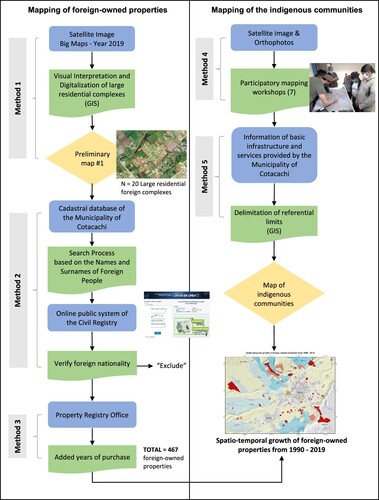

Due to the fact no official spatial data is available for foreign-owned properties in Cotacachi, the mapping was developed based on a combination of different cartographic methods and sources of information (see ). First, a visual interpretation and digitalization of the large residential complexes was carried out. For this purpose, we used a high-spatial resolution satellite image (less than 1 meter) from the year 2019 obtained through the Bing Maps platform. In doing so, we were able to identify 20 large residential foreign complexes or gated communities that were subsequently validated. Second, to identify smaller foreign-owned residential properties such as stand-alone houses, apartments, as well as unbuilt land purchased by foreigners, the cadastral database provided by the Department of Appraisals and Cadaster of the municipality of Cotacachi was analyzed. This database contains alphanumeric information of all properties in the city from which it was possible to know their geographic location, total area (m2), constructed area (m2), the names and surnames of the owners, etc. To identify foreign-owned properties, a labor-intensive, consecutive two-step search process was performed: (1) we identified properties owned by people with foreign names and surnames in the Cadaster; and (2) we used the online public system of the Civil Registry (https://servicios.registrocivil.gob.ec/cdd/), to verify whether the identified owners are of Ecuadorian or foreign nationality. As a result of this process, a total of 467 foreign-owned properties were identified. Finally, to map the spatial growth and distribution of foreign-owned properties in the city, we developed a multi-temporal map based on three time periods: (A) 1990–2007, (B) 2008–2013, (C) 2014–2019 (See Main Map). In order to be able to provide this information, the purchase dates of these properties were obtained through the database of the Property Registry Office.

3.3 Mapping the boundaries of indigenous communities

Official boundaries of indigenous communities do not exist in Cotacachi. To map the territories of the indigenous communities, two cartographic methods were used. First, participatory mapping workshops were conducted in different indigenous communities. Due to the high number of communities in the study area, the workshops were carried out mainly in seven indigenous communities where the largest number of foreign-owned properties are most notable (Azaya, La Calera, El Batán, San Ignacio, San Pedro, Santa Bárbara, and Tunibamba). For this purpose, high-resolution satellite images and orthophotos were used, which were distributed among the participants to draw the boundaries of their communities. The workshops had the active participation of several members: youth, elders, women, as well as indigenous leaders. Second, the boundaries of the indigenous communities, which were not considered in the participatory mapping workshops, were estimated based on existing information of the basic infrastructure and services (main roads, schools, etc.) provided to indigenous communities by the Municipality of Cotacachi. Therefore, these limits are considered as referential. All the information was processed using ARCGIS 10.3 software.

3.4 Interviews with key stakeholders

Finally, to know how the real estate market for foreign properties has developed in recent years, semi-structured interviews were carried out with different stakeholders. Interviews were conducted at the two main real estate agencies in the city (Santana Real Estate and Cotacachi Homes), as well as two telephone calls to the main builders of real estate projects for foreigners. Likewise, several conversations were held with members of the Department of Appraisals and Cadastre, as well as the Land Registry of the Municipality of Cotacachi. The interviews and workshops were held between September and October 2020. The usage of different secondary data sources (e.g. a cadastral database, satellite images), as well as methods such as participatory mapping and related interviews helped us to mitigate the uncertainties of our database and triangulate our results, which are presented in the following section.

4. Results

4.1 Number of properties and amount of land acquired by foreign retirees

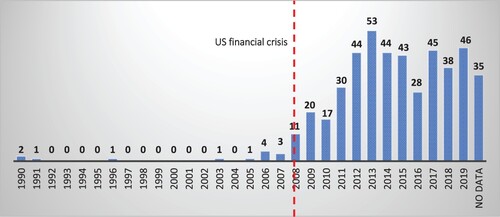

The results show a significant growth in the number of properties acquired by foreign retirees in the last several years. From 1990 to 2007, only 13 properties were registered to foreign names in the city. However, since 2008, there has been a steep increase in property purchases by foreigners with a total of 454 new properties registered as of 2019 (see ). According to the data obtained through the cadastral database of the municipality of Cotacachi, there are 467 properties owned by foreigners. However, it is important to mention that this information does not consider the properties that are for rent, so the total number of foreign households in Cotacachi might even be considerably higher. According to our interviews with the Property Registry Office, transactions are generally carried out directly by foreign citizens. This is because for e.g. to Visa issues, foreign citizens prefer the property to be in their name, rather than in the name of a third party (real estate agent). Purchasing property in Ecuador worth $30,000 or more can help make a retiree eligible for an ‘Investor Visa’ in the country. (Bayer 2018; Haines 2018a; quoted in CitationSloane & Silbersack, Citation2020).

Figure 2. Number of properties purchased by foreigners from 1990 to 2019. Data Source: Cadastral Database of the Municipality of Cotacachi, 2019. (Own elaboration).

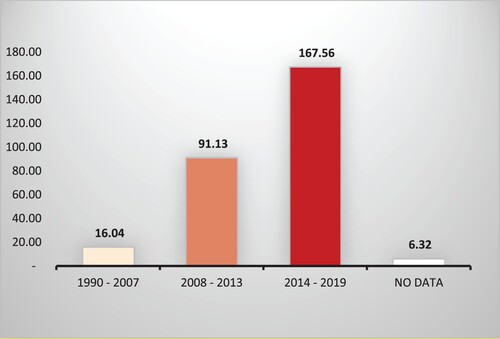

Similarly, the results obtained through multi-temporal mapping show an increase in the area of land purchased by foreigners. As shown in , during the first study period (1990–2007), there were only about 16 ha of land owned by foreigners. However, during the following period (2008–2013) this area increased to more than 91 ha and then to about 167 ha in the last period (2014–2019). In sum, a total of more than 280 ha of land has been purchased by foreigners within about three decades (1990–2019). If we compare this figure with the size of the urban area (568 ha), the amount of land acquired by foreigners represents about 49% of the urban area of Cotacachi.

Figure 3. Land purchased by foreigners from 1990 to 2019. Data Source: Cadastral Database of the Municipality of Cotacachi, 2019. (Own elaboration).

4.2 Spatial distribution and growth of foreign-owned properties

The multi-temporal map visualizes the spatial distribution and growth of foreign-owned properties over the three time periods analyzed: (A) 1990–2007, (B) 2008–2013, (C) 2014–2019. Foreign-owned properties are located both inside and outside the urban area. According to our interviews, the first residential projects designed for foreign retirees were built mainly within the urban area. The very first project, called ‘Primavera 1’, was constructed in 2007 and consisted of a building with 8 apartments plus a detached house. Then, a second larger residential project was immediately built nearby, called ‘Primavera 2’, consisting of 4 buildings with 32 apartments (Interview A, 2020). However, land for construction of large-scale housing projects with a private open space for all kinds of amenities is in short supply within the urban area of Cotacachi. Individual plot sizes are small and unbuilt plots are spatially dispersed. Therefore, the development potential within the city was limited. In addition, strong promotion by U.S. residents through online forums (CitationKline, Citation2013) quickly boosted the real estate sector in Cotacachi, pushing development outside the urban area (CitationGascón, Citation2015). Therefore, the spatio-temporal expansion of foreign-owned properties concentrated on areas located directly beyond the urban boundary, but in close proximity of about one to two kilometers to the urban center.

On the other hand, the map shows that many of the foreign-owned residential properties have been built on agricultural land, which belonged to former colonial haciendas. As CitationQuishpe and Alvarado (Citation2012) state, the large and medium-sized haciendas, stretching back to colonial times, were divided and sold to real estate companies to build residential developments for foreigners. In addition, a high number of foreign-owned properties are located in direct proximity to existing indigenous communities, resulting in a series of conflicts especially in relation to the issue of access to land. As previous studies have shown, the construction of housing for foreign retirees close to these areas ‘has generated a sharp increase in the price of rural land and has decelerated a land market that once allowed young farmers to continue agricultural activities’ (CitationGascón, Citation2015, p. 1). According to our map, there are several indigenous communities where the presence of foreign properties is most significant: San Pedro, El Batán, Azaya, Santa Bárbara, Topo Grande, San Ignacio, and La Calera.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we document the spatio-temporal dynamics of IRM-related real estate development in the Andean city of Cotacachi, Ecuador. Based on data triangulation from remote sensing, participatory mapping, document analysis (e.g. a cadastral database) and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, we developed a multi-temporal map showing the spatial distribution of the foreign-owned real estate properties and its link to the historical colonial process of land tenure. Our results show that foreign land ownership in Cotacachi has accelerated since the 2008 financial crisis. Our multi-temporal map reveals that most of these residential properties are located at the urban fringe of the city and have been built on land that used to belong to the former colonial haciendas in direct proximity to several existing indigenous communities. In this way, our findings not only support existing studies on IRM-related effects in Cotacachi (CitationGascón, Citation2015, Citation2016) but also enhance them in outlining in detail where these processes of land speculation and depeasantisation have mostly occurred.

The developed map is unique, as no official spatio-temporal data is available for foreign-owned properties in Cotacachi – maybe even for all of Ecuador. In this sense, this research proposes a methodological approach which could be applied in other areas where the phenomenon of IRM is gaining momentum. Here it can be also used to inform public policy and territorial planning debates.

As most of these properties are in direct proximity to several indigenous communities, future research is needed to better understand the series of socio-economic and spatial effects of IRM in these areas, which have only been shortly addressed in this article. In particular, issues related to land price increases, land speculation, land use changes, as well as impacts on the livelihoods of the indigenous people need to be analyzed in more detail. Therefore, the multi-temporal map prepared in this study will contribute significantly to a better spatial knowledge of IRM-related effects.

Software

The software used to create the map was ArcGis 10.3. The data and graphics were processed on Microsoft Office Excel 2019.

Final_Map.pdf

Download PDF (2.5 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Municipality of Cotacachi for their collaboration in providing the information, as well as the representatives of the indigenous communities for their active participation in the workshops.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bastos, S. (2013). Territorial dispossession and indigenous rearticulation in the Chapala Lakeshore. In Contested Spatialities, Lifestyle Migration and Residential Tourism. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203100813

- Benson, M. C. (2013). Postcoloniality and privilege in new lifestyle flows: The case of North Americans in Panama. Mobilities, 8(3), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.810403

- Blasco Peris, A. (2009). La Percepción Social del Turismo residencial a través de los impactos que genera en la sociedad de acogida. Caso de Sant Pol de Mar, Barcelona. Turismo, Urbanización y Estilos de Vida. Las Nueves Formas de Movilidad Residencial, 367–381.

- Brown, L. A., Brea, J. A., & Goetz, A. R. (1988). Policy aspects of development and individual mobility: Migration and circulation from Ecuador’s rural sierra. Economic Geography, 64(2), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.2307/144121

- Camacho, J. (2006). Good to eat, good to think: Food, culture and biodiversity in cotacachi. In R. E. Rhoades (Ed.), Development with identity: Community, culture and sustainability in the Andes (pp. 156–172). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851999494.0156.

- Casado-Diaz, M. A. (1999). Socio-demographic impacts of residential tourism: A case study of Torrevieja, Spain. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(4), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-1970(199907/08)1:4<223::AID-JTR153>3.0.CO;2-A

- Casado-Diaz, M. A. (2016). Social capital in the sun: Bonding and bridging social capital among British retirees. In M. Benson, & K. O’Reilly (Eds.), Lifestyle migration: Expectations, aspira- tions and experiences (pp. 87–102). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Crespo, M. (2014). Extranjerización de la tierra agrícola en el cantón Cotacachi. Estudio de caso: Comunidad El Batán. Tesis de Máster. Flacso Ecuador.

- Efird, L., Sloane, P. D., Silbersack, J., & Zimmerman, S. (2020). Social and Cultural Impact of Immigrant Retirees in Cuenca, Ecuador and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico (pp. 67–90). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33543-4_4

- El Telégrafo. (2017). Los ‘gringos’, tras un paseo, descubrieron en Ecuador su lugar favorito para vivir. Retrieved January, 19 2022, from https://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/sociedad/6/los-gringos-tras-un-paseo-descubrieron-en-ecuador-su-lugar-favorito-para-vivir

- Gascón, J. (2015). Residential tourism and depeasantisation in the Ecuadorian Andes. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(4), 868–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1052964

- Gascón, J. (2016). El turismo residencial como vector de cambio en las economías campesinas (Cotacachi, Ecuador). Estado & Comunes, Revista de Políticas y Problemas Públicos, 2(3), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.37228/estado_comunes.v2.n3.2016.25

- Guerrero, A. (1975). La hacienda precapitalista y la clase terrateniente en América Latina y su inserción en el modo de producción capitalista: el caso Ecuatoriano. Facultad de Jurisprudencia.

- Guerrero, F. (2004). El mercado de tierras en el cantón Cotacachi de los años 90. Ecuador Debate, 62, 187–208.

- Gustafson, P. (2016). Our home in Spain: Residential strategies in international retirement migra- tion. In M. Benson, & K. O’Reilly (Eds.), Lifestyle migration: Expectations, aspirations and experiences (pp. 69–86). Routledge.

- Hayes, M. (2013). Una nueva migración economica: El arbitraje geográfico de los jubilados estadounidenses hacia los países andinos. Andina Migrante, 15, 2–13.

- Hayes, M. (2016). En la tierra de los hacendados: migración de amenidad y reproducción de desigualdades locales y globales en Vilcabamba, Ecuador. 99–118.

- Hayes, M. (2018). Gringolandia: Lifestyle migration under late capitalism. University of Minnesota Press.

- Hayes, M. (2020). The coloniality of UNESCO’s heritage urban landscapes: Heritage process and transnational gentrification in Cuenca, Ecuador. Urban Studies, 57(15), 3060–3077. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019888441

- Huete, R. (2008). Tendencias del turismo residencial: El caso del Mediterráneo Español. El Periplo Sustentable, 14(14), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.21854/eps.v0i14.943

- INEC (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos). (2010). National Population and Housing Census. Retrieved December 22, 2021, from http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/informacion-censal- cantonal/

- International Living. (2021). The Best Places in the World to Retire in 2021. Retrieved January, 19 2022, from https://rosedalliving.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/International-Living-The-best-places-to-retire-in-2021.pdf

- International Living. (2022). The World’s Best Places to Retire in 2022. Retrieved January, 19 2022, from https://internationalliving.com/the-best-places-to-retire/

- Janoschka, M. (2011). Imaginarios del turismo residencial en Costa Rica: Negociaciones de pertenencia y apropiación simbólica de espacios y lugares: Una relación conflictiva. Construir Una Nueva Vida: Los Espacios Del Turismo y La Migración Residencial, 81–102.

- Kline, A. (2013). The amenity migrants of Cotacachi. Mg diss. Ohio State University.

- Lizárraga, O. (2010). The US citizens Retirement Migration to Los Cabos, Mexico. Profile and social effects. Recreation and Society in Africa, Asia and Latin America, 1(1), 75–92.

- Membrado, J. C. (2015). Migración residencial y urbanismo expansivo en el mediterráneo español. Cuadernos de Turismo, 35(35), 259–285. https://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.35.221611

- Monterrubio, C., Sosa Ferreira, A. P., & Osorio García, M. (2018). Impactos del turismo residencial percibidos por la población local: Una aproximación cualitativa desde la teoría del intercambio social. LiminaR. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos, 16(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.29043/liminar.v16i1.567

- Ortiz Crespo, S. (2004). Cotacachi: una apuesta por la democracia participativa. FLACSO.

- Pastor, C. (2014). Ley de tierras el debate y las organizaciones campesinas. Ediciones La Tierra.

- PDOT. (2015). Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial de Cotacahi.

- Pontes da Fonseca, M. A., & Janoschka, M. (2018). Turismo, mercado imobiliário e conflito sócioespaciais no Nordeste brasileiro. Sociedade e Território, 30(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.21680/2177-8396.2018v30n1id13450

- Quishpe, V., & Alvarado, M. (2012). Cotacachi: derecho a la tierra frente a urbanizaciones y especulación. https://ocaru.org.ec/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Cotacachi-Derecho-a-la-Tierra.pdf

- Rhoades, R. E. (2006). Linking sustainability science, community and culture: A research partnership in Cotacachi, Ecuador. In Development with Identity: Community, Culture and Sustainability in the Andes. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851999494.0001

- Sloane, P. D., & Silbersack, J. (2020). Real Estate, Housing, and the Impact of Retirement Migration in Cuenca, Ecuador and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico (pp. 41–65). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33543-4_3

- Torres Bernier, E. (2003). El turismo residenciado y su efecto en los destinos turísticos. Estudios Turísticos, 155&156, 45–70.

- van Noorloos, F. (2013). El Turismo residencial: ¿Acaparamiento de tierras? Un proceso fragmentado de cambio socio-espacial, desplazamiento y exclusión. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/313997/60.pdf?sequence=1

- Van Noorloos, F., & Steel, G. (2016). Lifestyle migration and socio-spatial segregation in the urban(izing) landscapes of Cuenca (Ecuador) and Guanacaste (Costa Rica). Habitat International, 54(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.014

- Viteri, M. A. (2015). Cultural imaginaries in the residential migration to cotacachi. Journal of Latin American Geography, 14(1), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2015.0005