ABSTRACT

During the last decades, the tourism market saw the growth of national and regional brands based on characters and places promoted through movies and TV series. One of the most notorious tourism brands based on fictional works is represented by Dracula. With a constantly expanding coverage on entertainment channels, Dracula became widely popular and strongly associated with Romania. However, its capitalization by national tourism actors lacks synergy and integration of spatial features. In this paper, we use an original cartographic approach combining the spatial distribution of Dracula attractions and online data regarding tourist behavior aimed to set up a decision-making toolkit for the enhancement of brand management. The results confirm the existence of a spatial pattern in the distribution and differentiation of Dracula attractions, which affects the overall tourist behavior and satisfaction. The paper provides several recommendations for national actors in order to upgrade the tourism management of Dracula's image.

1. Introduction

The increasing competition in the international tourism market has reinforced the destinations’ efforts to further invest both money and creativity into their branding strategies. The race for tourists has recently seen the appearance of a highly effective branding tool: movies and TV series. Many destinations (New Zeeland, Scotland, Croatia, Iceland) have swiftly increased their popularity and tourist flows following the airing of famous productions, especially from the fantasy genre, such as Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, Harry Potter (CitationBeeton, 2005; CitationLight, 2009; CitationReijnders, 2010). While inspired mainly from fantasy novels, these cultural references have strong roots into the historical and cultural backgrounds of the territories promoted. Nevertheless, the management of tourism brands inspired by popular movies or books has rarely addressed the connections and the anchorage into the territorial networks. Therefore, we consider that spatial-oriented approaches could provide the missing pieces required for the establishment of an effective management with respect to this type of brands.

1.1. The place of Dracula brand in dark tourism

Count Dracula, the famous vampire character introduced by Bram Stoker in 1897 is a worldwide known myth which generated a national brand constantly reinforced by media and literature during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (CitationLight, 2017). This brand plays an important role in Romania's destination image given that the whole country, and the Transylvania region in particular, has become known as Dracula's homeland (CitationLight, 2009; CitationLupu et al., 2017). As vampires and other supernatural characters are known to enhance people's imagination and their desire to visit real places connected to the fictional stories, Romania has become consequently a top destination for Dracula and vampire fans, especially during Halloween (CitationHovi, 2008; CitationStoleriu, 2014). Recent blockbusters have added new fantasy characters associated with Transylvania and Romania, such as Dracula's daughter, Frankenstein, or werewolves. Therefore, the places associated with Bram Stoker’s character (Dracula) or with the historical figure that inspired it (prince Vlad the Impaler) have become top attractions for foreign tourists (CitationHovi, 2008). Scholars define this type of tourism as Dracula tourism which describes the visiting of real places and historical heritage and comparing them to the fictional stories (CitationHovi, 2008; CitationLight, 2009; CitationReijnders, 2011).

Given its strong anchoring in an increasing number of fantasy movies and literature, Dracula tourism can be considered a form of movie and literary tourism (CitationMuresan & Smith, 1998) that has evolved through media promotion into a media-induced tourism (CitationReijnders, 2011). Moreover, Dracula tourism has a macabre side as well. Most of the tourists are looking for the mythical character – vampire Dracula – for supernatural adventures, or thrilling experiences inspired by horrific events associated with Vlad the Impaler (CitationLight, 2009, Citation2017). This macabre side of Dracula tourism attractions and experiences justified the inclusion of Dracula tourism in the dark tourism spectre (CitationLewis et al., 2021; CitationLight, 2017; CitationMiles, 2014; CitationMillán et al., 2019).

Dark tourism generally encompasses visits to real or commodified places associated with death, suffering and tragedy (CitationLennon & Foley, 2000; CitationMiller et al., 2017). However, visitor experiences have evolved from actual or symbolic encounters with death (CitationSeaton, 1996) to a larger palette of products (CitationLight, 2017; CitationMiles, 2014) based on the search for thrills, otherworldly, or seemingly macabre as a main theme (CitationBiran & Poria, 2012; CitationRaine, 2013; CitationStone, 2005, Citation2006). In this framework, Dracula tourism is either linked to the wider macabre theme (CitationLewis et al., 2021; CitationLight, 2009; CitationMiles, 2014) or considered a category of dark tourism on its own (CitationLight, 2017; CitationMillán et al., 2019). The spectrum of dark attractions includes places based on real characters and stories as well as fiction-based attractions. Media has had a major role in increasing people’s fascination with thrilling and macabre attractions (CitationSeaton & Lennon, 2004), hence the increasing popularity of the vampire and Halloween tours, ghost tours or other thrilling encounters with the macabre (CitationBiran & Poria, 2012; CitationMillán et al., 2019; CitationStoleriu, 2014; CitationStone, 2005, Citation2006).

There are multiple shades of darkness among dark tourism attractions. Thus, ranging from lighter to darker, they include dark fun factories (horror museums), dark exhibitions (with an educational or entertaining purpose), prisons, graveyards, shrines (usually for recently deceased) and celebrity death sites, battlegrounds and camps of genocide (concentration camps) (CitationLennon, 2017; CitationStone, 2006). Within this spectrum, Dracula tourism is considered a lighter form of dark tourism, as it is mainly based on a fictional character (CitationLight, 2017).

1.2. Dracula-related myths in Romania's promotion and the territorial incongruity

The Dracula myth is considered a foreign (imported) concept and has raised many controversies in Romania because it contradicts the historical facts. The medieval prince Vlad the Impaler (Vlad Tepes) has been presented by national historical narratives as a national hero, iconic for his harsh justice. Bram Stoker built the Dracula character inspired by the historical figure but adding (as other cultural representations afterwards) a darker nuance. This contradiction has generated controversy and dual attitudes regarding the Dracula myth among Romanian tourism authorities, academics and general population (CitationBanyai, 2010). While some voices defend the economic benefits of capitalizing the tourists’ fascination with fictional vampire stories, others advocate for historical authenticity, considering Dracula a negative brand for Romania, hence the national rejection of Dracula-inspired tourism (CitationKaneva & Popescu, 2011; CitationReijnders, 2011; CitationStoleriu & Ibanescu, 2014).

This dichotomy was underlined in various dimensions regarding Romanian tourism development: interviews with tourism actors (CitationLight, 2007), strategic national documents and initiatives of local administrations (CitationLight, 2007; CitationStoleriu & Ibanescu, 2014), national promotional campaigns (CitationKaneva & Popescu, 2011; CitationStoleriu & Ibanescu, 2015), web pages of travel agencies (CitationHovi, 2014; CitationStoleriu, 2014), visitors’ reviews (CitationLupu et al., 2017), blogs and opinions of local residents (CitationBanyai, 2010), tourist behavior (CitationLight, 2009). In time, these circumstances generated a lack of unitary strategies and efficient cooperation among tourism actors for a successful capitalization of the Dracula brand.

Since the first manifestations of foreign visitors’ interest for Dracula-based tours in Romania, during the 1970s, the communist regime has started building Dracula attractions and themed tours exclusively for foreign tourists, while it simultaneously reinforced internal heroic representations of Vlad the Impaler (CitationLupu et al., 2017). After the fall of communism, Romanian tourism authorities have focused on promoting a positive (and modern) country image, hence their constant dismissal of the Dracula brand, generally perceived as fake and with a negative impact on a country already bearing the unwanted label of communist. Furthermore, when national authorities realized the potential of the brand and tried to capitalize it through a thematic park (2001), they met a large societal opposition that led to its abandonment. After this event, the involvement of national or local authorities diminished to scarcer and lower impact initiatives, such as the Dracula tour launched by the Romanian Employers’ Federation of Tourism and Services in 2012, or minor festivals organized by local authorities that merged vampire myth and historical heritage (CitationHovi, 2014). Contradictorily, private actors were more open to capitalize the brand by developing their own businesses based on both the historical and fictional characters, such as themed tours, accommodation units, restaurants, or souvenirs production (CitationBanyai, 2010). However, most of the private initiatives are dispersed, with short or temporary impact, and with a mitigated effect on visitors’ experience, the latter being often disappointed by the contradiction between their expectations and the poor capitalization of the myth at Dracula linked attractions (CitationBanyai, 2010; CitationLupu et al., 2017).

We consider that the lack of synergy in exploiting the Dracula brand is due to the week integration of the spatial dimension (location, emplacement, networks) in the regional and national tourism strategies. Therefore, a more substantial approach towards the territorial realities and spatial matters could substantially improve the overall plan of action, the collaboration between actors, and the effectiveness of the Dracula brand. This paper presents an original cartographic approach in terms of research data and the perspective on Dracula tourism in order to generate a robust toolkit necessary for the enhancement of the brand handling. We used online visitor reviews posted on TripAdvisor between 2017 and 2020 to identify and map the main attractions linked to Dracula tourism, as well as their levels of online popularity. Moreover, we classified these attractions according to the dark tourism spectrum, the resulting maps bringing a novel and unique perspective on the spatial configuration and typology of Dracula tourism resources which can be used for the formulation of tourism strategies.

2. Methods

For this paper, we chose the most comprehensive type of data in terms of tourist behavior available to date: online data. Social media platforms represent a major communication channel for tourism branding and a key information source for tourists, managers, and researchers (CitationKim et al., 2015; CitationZhang & Cole, 2016). Online visitor reviews are known for their increasing influence on tourist decisions and behavior (CitationLitvin et al., 2008), with TripAdvisor representing the world’s largest travel site – over 934 million reviews and about 490 million monthly active users.

Travelers usually consider online reviews as more trustworthy than official sources and more honest about real customer experiences with tourism products and services (CitationCheung et al., 2009; CitationFilieri, 2016; CitationZhang & Cole, 2016). People post reviews especially when their experiences are considered significant and memorable (CitationSemrad & Rivera, 2018) or when they want to help others (CitationChelminski & Coulter, 2011). They express subjective and spontaneous experiences in a brief and informal manner, which makes them valuable data for an increasing number of tourism studies (CitationBrochado et al., 2019; CitationLupu et al., 2017). For researchers, online reviews are a cost-effective and permanently updated information source regarding tourist experiences and satisfaction, with a worldwide reach (CitationKim et al., 2015; CitationLitvin et al., 2008).

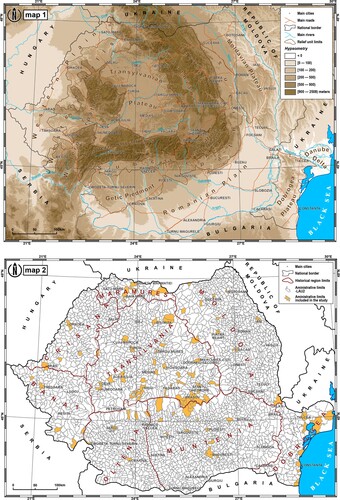

In order to accurately identify the spatial dimension of the database, we inventoried all Dracula attractions, their type, rating, popularity, and reviews at the LAU-2 level, the most accurate level in terms of cartographic representation for Romania (, map 2). The exhaustive list of variables used is available in . The data was collected from the TripAdvisor platform, using a web scraping tool (WebHarvy).

Figure 1. Physical map of the study area (map 1); Spatial distribution of Dracula-linked attractions according to the administrative units (map 2).

Table 1. Description of variables used in the study.

The mapping of the mythical, historical and dark fantasy dimensions of tourist attractions was done using the ArcMap v.10.2 and Adobe Illustrator CC 2017 software. For each LAU2 we used the point centroids of the administrative areas’ polygons, which are freely available in shapefile format on the website of ANCPI (National Agency for Cadastre and Land Registration). The parameters mapped were calculated in Excel software and the results were joined as an attribute table to the point centroids using their SIRUTA (Register Information System of Territorial Administrative Units) codes. The cartographic materials were done in an A2 format (420 × 594 mm), in the Pulkovo 1942-Adj 1958 geographical system of coordinates. The maps grids represent the values of geographical coordinates, as latitude-longitude in degrees and minutes.

3. Results and discussions

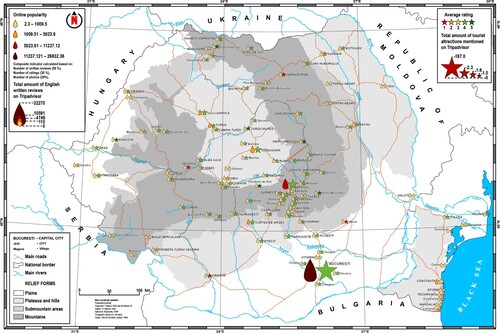

Overall, a high concentration of Dracula-linked attractions can be observed inside the Carpathian Mountains, within the Transylvania region (), a territory linked both with the historical ruler and the Dracula character. Fewer and more scattered locations can be identified outside the Carpathians, the vast majority of non-Transylvanian attractions being located in major cities (Bucharest, Timisoara, Iasi, Constanta) which have little connections with either the fictional or the historical character. These attractions use Dracula’s character as identification with a national brand and a mean to create appeal towards foreign tourists.

Figure 2. The most popular Dracula destinations according to their online popularity and average rating.

The Dracula map displays a mix of key historical sites linked to Vlad the Impaler (Targoviste – the princely court’s ruins, the Arefu fortress), locations solely inspired by the Dracula myth (Bran Castle known as Dracula’s Castle, Hotel Castle Dracula from Tiha Bargaului – built after the plans from Stoker’s novel) and unrelated tourist attractions that use Dracula as leverage for their attractiveness. As regards the average rating, the list of best-appreciated destinations highlights iconic Dracula destinations (Bran, Sighisoara, Brasov), major cities endowed with more diverse tourist facilities (Bucharest, Iasi, Timisoara, Cluj-Napoca) and several well-known rural tourist destinations from mountain area (Gura Humorului, Moeciu, Azuga, Horezu).

Therefore, in a purely quantitative matter, a false sense of the homogeneous distribution of the Dracula brand in Romanian destinations is displayed. Nevertheless, this distribution has several nuances and different levels of intensity. In order to better capture the nuances of the Dracula brand distribution, we calculated an indicator of online popularity for all destinations based on the number of reviews, the number of photos and the average rating (see ). This indicator is mapped in and illustrates a similar above-average concentration inside the Carpathian Mountains and towards Bucharest. The destinations with the highest numbers of reviews, photos, and higher ratings on TripAdvisor are the main cities from Transylvania and the capital city. They benefit from a high number of attractions and a wider range of facilities (Bucharest, Brasov, Sighisoara, Sibiu). This may seem counterintuitive, but the explanation resides in the influence that service quality, facilities, and transport accessibility have upon tourist satisfaction. Besides major cities, the map emphasizes a category of smaller localities with relatively high values of the indicator (Curtea de Arges, Bran, Biertan) which seem to successfully merge the historical background of Vlad the Impaler with connections to the fictional Dracula character.

The number of English written reviews is an indicator of the destination visibility and is usually correlated with the number of foreign visitors. This explains why the major Romanian destinations for international tourism appear as front runners, including main cities within or outside the Carpathians, popular mountain resorts around Bran Castle, main seaside resorts, and a selection of traditional rural destinations in the Danube Delta and Northern Romania. The cluster of localities around Hotel Castle Dracula has a higher visibility on the popularity map than on the map representing the number of total attractions, showing that the number of attractions is not a direct indicator for the popularity.

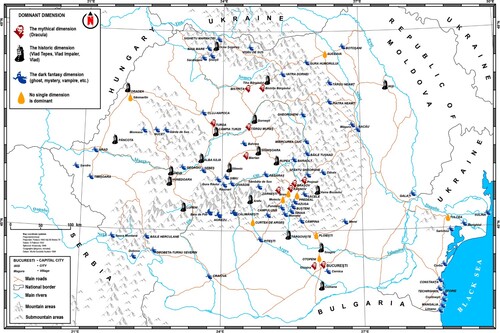

The apparent prerequisite of a strong connection between the attraction and the historical or fictional character motivated our search for additional factors explaining the spatial distribution of the Dracula brand. Therefore, a thematic map with the main dimensions of online reviews was built (the indicator is explained in ). To our knowledge, this is the first initiative of thematically mapping a national brand. The main purpose was to identify the main dimensions associated with destinations and the existence or absence of a direct connection with the historical or fictional character.

highlights the thematic orientation of the destinations analysed, and their spatial distribution.

Myth-oriented destinations (11 destinations), where the mythical dimension inspired by Bram Stoker’s novel is dominant. These destinations are mostly localized in Transylvania, with a stronger concentration around Bran Castle, plus several destinations more focused on Dracula (Turda, Zarnesti, Prejmer). Bucharest, the main national tourism destination, and Brasov, the most important city from the region, owe their place to the fact that they serve as starting points for many Dracula themed tours. Remarkably, the myth-orientated destinations do not overlap the iconic Dracula destinations, which questions the national strategies regarding Dracula promotion.

History-oriented destinations (20 destinations), where the historical figure of Vlad the Impaler is dominant. These destinations cover two types of backgrounds: (1) destinations directly connected to Vlad the Impaler (Sighisoara, the presumed birth place; Targoviste, where his royal court was located; Arefu, hosting one of his fortresses; Comana and Snagov, both presumed to host the ruler’s tomb), and (2) historic destinations without connections with Vlad the Impaler, but strongly anchored in the national history (Hunedoara, Alba Iulia, Oradea, Iasi). Rather surprisingly, Hotel Castle Dracula (from Tiha Bargaului) based thoroughly on Bram Stoker’s novel is more associated with the historical character than the fictional Dracula. One possible explanation could be offered by its positioning rather eccentric in the Transylvanian region, far away from Dracula-dominant destinations.

Dark fantasy destinations (64 destinations), where dark fantasy themes like ghost, vampire, and mystery are dominant. These destinations do not have a dominant Dracula core (neither historical or fictional), but use Dracula as a leverage for a wider fantasy orientated promotion (Main Map). As expected, they have a larger spatial distribution, following the main tourist areas in Romania. With the exception of several large cities (Constanta, Cluj, Timisoara, Arad), those attractions usually have 3 or less Dracula-based attractions, mostly accommodation units and restaurants. Few of them actually have a dark attraction, such as communist prisons (Sighetu Marmatiei), famous dark legends (Sibiu), or memorial sites.

No dominant dimension (9 destinations). This category encompasses destinations with attractions covering equally the dark and the historical background (Bran, Curtea de Arges), or less important destinations presenting fewer attractions with an equal spread on the myth/historic/fantasy spectrum from mountain areas, Danube Delta, or transit points.

Figure 3. The type of destination according to the dominant dimension in visitors’ reviews.

3.1. Implications of findings and conclusions

As regards the scientific implications of this study, the results bring new insights regarding the visitors’ perspective on their Dracula experiences as well as the spatial extension of the Dracula and Vlad the Impaler heritage (Main Map). Firstly, key Dracula themed destinations revealed in previous studies (CitationHovi, 2008; CitationLupu et al., 2017) are less emphasized in people’s reviews than expected. Moreover, the maps underlined small and medium destinations connected to Vlad the Impaler and to other dark attractions unmentioned in previous studies, as well as a wider range of associated features, besides the usual ‘count’ or ‘vampire’ (i.e. haunted, horror, mystery, witch). Secondly, the spatial distribution of Dracula attractions portrays a brand that goes beyond the core area previously defined between Transylvania and Bucharest, extending a lot further in the Carpathians and outside the mountain range. Destinations that do not necessarily have a direct connection to Dracula or Vlad the Impaler emerge as part of holiday or tour product configuration (places where tourists start their daily tours or stop for accommodation and food). This finding raises the question of how the development of the Dracula brand and its globalization affected not only the main locations associated with the fictional and the historical characters, but also destinations situated in the vicinity of these locations or destinations trying to benefit from the popularity of the brand by associating themselves with it. Thirdly, the brand mapping brings a new perspective on the online popularity indicator, an original outcome created for the study. The popularity was connected with the overall dimension of the destinations (mythical, historical, or dark fantasy) and tourists’ satisfaction, offering a useful approach for further studies tackling brand management.

For policy makers, private, and public tourism actors the study provides food for thought and directions for a better capitalization of the Dracula heritage. The map collection highlights a slightly different reality from the typical routes of Dracula tours and the location of iconic Dracula heritage. The capitalization of the fictional character (mythical dimension) is highly connected with the spatial dependency on Transylvania region and its cluster of numerous historical attractions. It seems that the Dracula brand, although based on a novel character, uses the resemblance with the historical figure as an amplifier and authenticity provider. This could offer an explanation and a possible solution for the cluster of Dracula-linked destinations in Northern Transylvania, specifically based on Bram Stoker’s work, that are poorly emphasized on the maps. For the strong cluster of destinations situated around Bran Castle, Dracula provides an orientation for the diversification of tourist products for a new clientele, while for less popular destinations from the Southern Carpathians it offers an opportunity for capitalization through the dark-tourism niche. Local and regional authorities could support this diversification through a stronger promotion, collaboration with tour operators, and the organization of themed events in collaboration with private actors. In rural areas, the Dracula brand could easily be anchored in a more diverse local heritage or merged to local dark myths.

While our study managed to provide an exhaustive image of the Dracula brand in Romania, a limitation linked to the nature of the data could be considered. Online reviews are valuable for their updated and subjective information regarding visitors’ subjective perspectives and satisfaction. The importance of such a rich perspective cannot be denied by public or private tourism actors if they look for updated and continuous connection with the market demand. However, we must be aware that this is only a part of the overall image, because not all tourists post their impressions online. Moreover, future research could take this approach further, by integrating a destination-centred content analysis of visitors’ reviews which would bring new insights regarding the subjective attributes associated with each destination, beyond the official discourses and promotional materials.

Software

WebHarvy software was used to collect data from the TripAdvisor platform. For data structuring and analysis, the authors used Excel 2016. The preliminary maps were created with ArcGIS 10.2., and they were finalized with Adobe Illustrator CC 2017.

Author Contributions

All four authors contributed equally to the development of the framework and writing of this manuscript.

TJOM_A_2071647_Suplementary material

Download PDF (131.6 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data used in this article is available upon request [corresponding author].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Banyai, M. (2010). Dracula’s image in tourism: Western bloggers versus tour guides. European Journal of Tourism Research, 3(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v3i1.42

- Beeton, S. (2005). Film induced tourism: Aspects of tourism. Wordswork ltd.

- Biran, A., & Poria, Y. (2012). Reconceptualising dark tourism. In R. Sharpley, & P. Stone (Eds.), The contemporary tourist experiences: Concepts and consequences (pp. 62). Routledge.

- Brochado, A., Stoleriu, O., & Lupu, C. (2019). Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1649373

- Chelminski, P., & Coulter, R. A. (2011). An examination of consumer advocacy and complaining behavior in the context of service failure. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(5), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111149711

- Cheung, M. Y., Luo, C., Sia, C. L., & Chen, H. (2009). Credibility of electronic word-of-mouth: Informational and normative determinants of online consumer recommendations. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 13(4), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415130402

- Filieri, R. (2016). What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.019

- Hovi, T. (2008). Dracula tourism and romania. In S. Miloiu, I. Stanciu, & I. Oncescu (Eds.), Europe as viewed from the margins: An East-Central European perspective from World War I to Present (pp. 73–84). Târgovişte: Valahia University Press.

- Hovi, T. (2014). The use of history in Dracula tourism in Romania. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, 57, 55–78. https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2014.57.hovi

- Kaneva, N., & Popescu, D. (2011). National identity lite: Nation branding in post-communist Romania and Bulgaria. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910382181

- Kim, D., Jang, S., & Adler, H. (2015). What drives café customers to spread eWOM? Examining self-relevant value, quality value and opinion leadership. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2013-0269

- Lennon, J. (2017). Dark tourism. In Oxford research encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.212

- Lennon, J. J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism: In the footsteps of death and disaster. Cassell.

- Lewis, H., Schrier, T., & Xu, S. (2021). Dark tourism: Motivations and visit intentions of tourists. International Hospitality Review, (Preprint), https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-01-2021-0004

- Light, D. (2007). Dracula tourism in Romania cultural identity and the state. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(3), 746–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.03.004

- Light, D. (2009). Performing Transylvania: Tourism, fantasy and play in a liminal place. Tourist Studies, 9(3), 240–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797610382707

- Light, D. (2017). The undead and dark tourism: Dracula tourism in Romania. In G. Hooper, & J. J. Lennon (Eds.), (2016) Dark tourism: Practice and interpretation (pp. 121–133). Routledge. ISBN 978-036-7368-78-4.

- Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.011

- Lupu, C., Brochado, A., & Stoleriu, O. M. (2017). Experiencing Dracula’s homeland. Tourism Geographies, 19(5), 756–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1336786

- Miles, S. (2014). Battlefield sites as dark tourism attractions: An analysis of experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(2), 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2013.871017

- Millán, G. D., Rojas, R. D. H., & García, J. S.-R. (2019). Analysis of the demand of dark tourism: A case study in Córdoba (Spain). Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 10(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.2478/mjss-2019-0015

- Miller, D. S., Gonzalez, C., & Hutter, M. (2017). Phoenix tourism within dark tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-08-2016-0040

- Muresan, A., & Smith, K. A. (1998). Dracula’s castle in Transylvania: Conflicting heritage marketing strategies. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 4(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259808722223

- Raine, R. (2013). A dark tourist spectrum. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2012-0037

- Reijnders, S. (2010). Places of the imagination: An ethnography of the TV detective tour. Cultural Geographies, 17(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474009349998

- Reijnders, S. (2011). Stalking the count: Dracula, fandom and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.08.006

- Seaton, A., & Lennon, J. J. (2004). Thanatourism in the early 21st century: Moral panics, ulterior motives and alterior desires. New Horizons in Tourism: Strange Experiences and Stranger Practices, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851998633.0063

- Seaton, A. V. (1996). Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259608722178

- Semrad, K. J., & Rivera, M. (2018). Advancing the 5E's in festival experience for the Gen Y framework in the context of eWOM. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.08.003

- Stoleriu, O. M. (2014). Dracula tourism and dark geographies of Romania. Proceedings of the International Antalya Hospitality Tourism and Travel Research Conference Proceedings, Antalya, Turkey, 9–12.

- Stoleriu, O. M., & Ibanescu, B.-C. (2014). Dracula tourism in Romania: From national to local tourism strategies. SGEM 2014 Conference Proceedings, 2, 225–232. https://doi.org/10.5593/SGEMSOCIAL2014/B24/S7.029

- Stoleriu, O. M., & Ibanescu, B.-C. (2015). Romania’s country image in tourism tv commercials. SGEM 2015 Conference Proceedings, 2, 867–874. https://doi.org/10.5593/SGEMSOCIAL2015/B22/S7.111

- Stone, P. R. (2005). Dark tourism consumption-A call for research. E-Review of Tourism Research (ERTR), 3(5), 109–117. ISSN 1941-5842.

- Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 54(2), 145–160. ISSN 1790-8418.

- Zhang, Y., & Cole, S. T. (2016). Dimensions of lodging guest satisfaction among guests with mobility challenges: A mixed-method analysis of web-based texts. Tourism Management, 53, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.001