ABSTRACT

Monterrey Metropolitan Zone (Mexico) is characterised by industrial activity and its proximity to the border with the US. In 2010, its 13 municipalities provided infrastructure and services that allow people to live, work or rest, but also a specific function (housing, work, or leisure) due to the prevalence of one of these, impacting the daily life of the population by gender. This article explores the relationship between travel distance to work and reproductive work for working women. Using data by the Extended Questionnaire of the Census Sample of the 2010 Population and Housing Census, home-work commuting routes were mapped at the municipal level, combined with four variables of reproductive work. Our study demonstrates that as the reproductive work increases for working women, they experience spatial segregation since they cannot travel as far as the ones with lower reproductive work because they are expected to take care of the reproductive work.

1. Introduction

The functional division of urban activities (mainly work and residence) has led people to use urban space separately. The aim of this research is to observe how urban planning affects women in different ways. The patriarchal conception where men’s ‘natural attributes’ are to provide protection and be the source of the family’s economic income, i.e. productive activities, while the women’s role are the reproductive and care activities have a strong influence on how cities are shaped. This gender division has led to the idea that productive and reproductive roles are carried out in completely different, distant, and unrelated spaces, segregating women in the domestic sphere and excluding them from the public sphere (CitationMcDowell, 2000; CitationMoser, 1989; CitationValcárcel, 2013).

Furthermore, both genders are confronted with the friction of distance and the principle of return in a greater or lesser degree. Individuals’ experience is based on the limitation to carry out their daily activities within a radius of action from home, the selection of different services or destinations to satisfy people’s need and consequent patterns of displacement are traditionally determined by the availability of time, budget, and transportation mode. However, aspects such as age, income, primary activity and gender will have a level of influence on this (CitationEllegård & Vilhelmson, 2004; CitationNæss, 2006).According to the evidence of co-location between housing and employment provided by CitationSuárez Lastra and Delgado Campos (2007, p. 2010), distance has a more significant impact on the location of paid work. Although revealing, their research does not analyse the information by gender, which would reveal very different realities of employability for each household member. Salazar (Citation1999, p. 132) makes it very clear that, in the specific case of women, the domestic organisation (whose immediate environment of activity is the house and the neighbourhood) must be added to the labour market, the urban structure, the location of residential areas, and the public transportation network, aspects faced by the population in general. Also, CitationHanson and Pratt (1991, Citation2003), CitationFanning Madden (1981), and CitationMojica Segovia (2014) pointed this out in their writings.

This study comprises four variables associated with the reproductive work of working womenFootnote1 living in the Monterrey Metropolitan Zone -MMZ- Main Map: marital status, number of children, age of the youngest child, and relationship to the head of household. The particular interest is to relate them to the geographical location of women’s paid work and determine if there are differences in the distance and concentration of women between the female productive work-residence trajectories.

2. Method and results

To investigate how the gender condition and reproductive work characteristics relate to working women’s job location, we used the Census Sample of the 2010 Population and Housing Census in Mexico. We are aware that by the time this article was written the 2020 Population and Housing Census data was available, as well as the 2015 Intercensal Survey. We decided to use the 2010 Population and Housing Census data because the only source for the information needed for our research was the expanded questionnaire from the Census Sample of the 2010 Population and Housing Census. The 2015 Intercensal Survey is a statistical representative sample of the whole population, and a conclusion is drawn that is very similar to the one that would be drawn if the whole population was studied as a universe. On the other hand, the results of the 2020 Population and Housing Census were still not published at the level of detail needed when the study was done. Also, this research stems from Hernandez-Reyes’ Doctoral dissertation (CitationHernández-Reyes, 2021), which was conducted before the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) generated and published the new information.

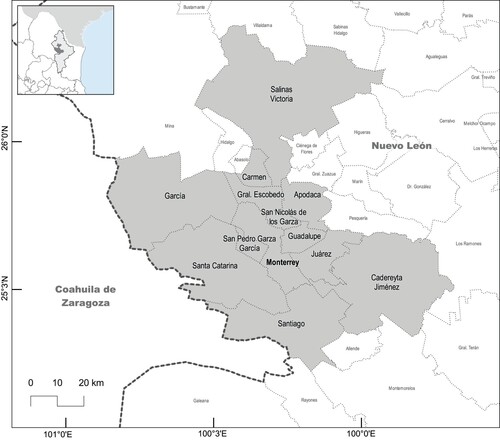

We selected the Monterrey Metropolitan Zone as our case study. Monterrey Metropolitan Zone is the third largest city in Mexico, and it is in the border state of Nuevo Leon, in the north-eastern part of the country (Map 1). By 2010,Footnote2 it had an area of 6794 sq. km., and a population of 4,106,054 inhabitants (CitationINEGI, 2016a), making an urban density of 109 inhabitants per hectare. It was composed by 13 municipalities: Apodaca, Cadereyta Jiménez, Carmen, García, San Pedro Garza García, General Escobedo, Guadalupe, Juárez, Monterrey, Salinas Victoria, San Nicolás de los Garza, Santa Catarina and Santiago (CitationSEDESOL et al., 2012).

Map 1. Monterrey metropolitan zone. Location and Municipalities included in the metropolitan zone.

The objective of this article is to find out how the working women of the MMZ were directly affected by their gender condition and reproductive work using the observed variables and the geographical location of their job. To achieve this, we selected all the working women from the Census SampleFootnote3 of the 2010 Population and Housing Census (CitationINEGI, 2016b), resulting in a universe of 22,408 cases, which represents almost 35% of the total number of women of working age of the 13 municipalities.

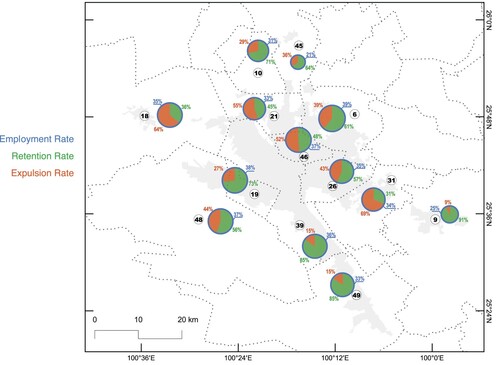

The next step for this study was to identify from the female labour force participation rate how many women stay in their municipality (retention rate) or must travel to another (expulsion rate) (Map 2). On average, 62% of these women stay in their municipality, with Cadereyta Jiménez the one that retains the most (91%), followed by Monterrey and Santiago, both with 85%. Whilst the municipalities of Juárez and García are the ones that expel the largest proportion of working women from their boundaries (69% and 64%, respectively).

Map 2. Rates of retention and expulsion working women in the MMZ.

We looked in our sample, for the four selected variables that constitute, together with others, what is known as reproductive work. Each of these variables is presented, analysed, and represented separately. For our maps, we used the geometric centroid of the urban area of each municipality (excluding land that is uninhabited) as a reference for the origin and destination of the travels, since the Census Sample only provided information at the municipal scale. In all the variables and categories observed, we only mapped those destinations that attracted more than 10% (up to 50%) of the municipal employment rate.

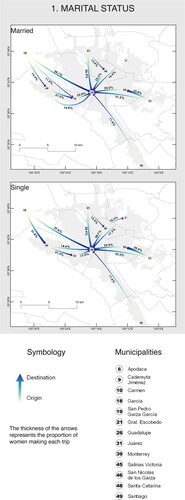

We consider it important to say that for Map 3 presented in this article, we followed the method for edge bundling for QGIS proposed by CitationGraser et al. (2019). By doing this, we were able to visualise the most important destinations for the working women outside of their municipality of residence. Using the function Summarise, we represented the Origin (yellow) and the Destination (dark blue) municipalities. Whilst using the function ‘Arrow size’, allowed us to express that the higher the value represented, the thicker the arrow is.

Map 3. Marital status. Women working outside their residential municipality. Range: 10–50%.

2.1. Marital status

For this study, we grouped the 10 available statuses of the Extended Questionnaire into just two: the Married status includes married women and those living with a partner regardless of legal status; the Single status considers single, divorced, and widows.

By looking at each municipality in , we can realise that being a married woman in the MMZ is a strong condition to work in the same municipality as the residential one, except for Apodaca and Carmen (which have the same rates).

Table 1. Percentage of Retained (Ret) and Expulsion (Exp) working women (ww) by marital status, by municipality.

Even when the average difference between both observed status is just four percentage points, the range between the highest and lowest values is larger in the ‘Single Status’ (60 percentage points for the Married versus 62 for the Single), which reinforces the argument that a single woman might have slightly less restrictions to get a job outside her municipality.

It is very interesting that in both Marital Statuses, two of the three municipalities with the highest retention rates are located in the south periphery of the MMZFootnote4: Cadereyta and Santiago, with an average of 91% and 85% of the working women, respectively. On the other hand, García and Juárez have the highest expulsion rates (66% and 70% on average for each municipality) of working women, which might imply that there are not enough working positions for women.

When focusing only on the Expulsion population from each of the 13 municipalities, shown in Map 3, we noticed that the municipality of Monterrey is the one that attracts most of the working women: 9 out of 14 arrows for both statuses have it as a destination. On the other hand, Juárez and García are the municipalities that expulsion the highest number of working women regardless of their Marital status (also demonstrated in ). In the case of Juárez, most women go to the closest neighbour: Guadalupe, being Monterrey the second. The working women of García, on the other hand, prefer to travel to Monterrey first, being their second option Santa Catarina, followed by San Pedro Garza García.

If we look at the travels in terms of the adjacent municipality in Map 3, the married working women from five municipalities travel to Monterrey and San Pedro (in one case), which are not contiguous to their residence municipality, whereas the single women only move to four, but the proportion of the later is larger, fact that reinforces our main argument.

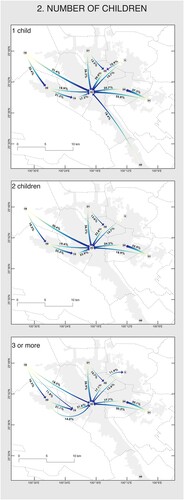

2.2. Number of children: one, two, and three or more children

Looking now to the variable of number of children that has each working woman in the MMZ,Footnote5 we clearly observe that as the number of children increases, more women tend to work within their residential municipality, i.e. closer to their home (). This happens in almost all the MMZ, except for four municipalities: Carmen, in the north, where the reverse is clearly the case; Monterrey, San Pedro, and Santa Catarina show rates of working women with two children lower relative to those with one or three children.

Table 2. Percentage of Retained (Ret) and Expulsion (Exp) working women (ww) by number of children, by municipality.

If we look at the expulsion population again from each municipality (Map 3), we can observe the same two patterns as in the Marital status variable. First, when looking at Monterrey as a destination, it is the main attractor for the working women, regardless of the number of children. Second, Juárez and García do not offer proper jobs to most of the female population.

In terms of the adjacent municipality, most of the working women travel to a contiguous municipality to work. When this is not the case (13 arrows in the three categories), Monterrey is the municipality to travel towards, with only one exception: working women with 3 or more children travelling from García to San Pedro.

Another relevant fact is that the working women from Santiago with two or more children represent a small fraction of this sample. Plus, they do not show a preference for their work’s location (in Map 4, when looking at the two maps of these categories, there are no arrows from Santiago to any other municipality).

Map 4. Number of children. Women working outside their residential municipality. Range: 10–50%.

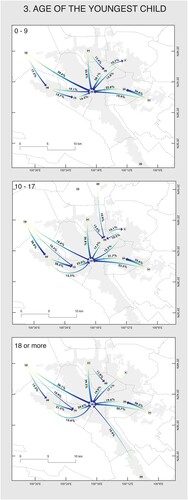

2.3. Age of the youngest child: 0–9 years, 10–17 years, and 18 years and over

We observe in that as their children get older, the working women tend to stay in their municipality, except for Apodaca and San Pedro, where the number of expulsion women increases, and Monterrey, which is constant.

Table 3. Percentage of Retained (Ret) and Expulsion (Exp) working women (ww) by age of the youngest child, by municipality.

These results may suggest that the higher economic demand represented by young children is what drives women to move away from their homes in exchange for better working conditions.

By looking at Map 5, we can confirm the Expulsion pattern of García and Juárez, with more than 47% of the sampled population travelling to just two or three municipalities (in the case of García, when the youngest child is older than 10).

Map 5. Age of the youngest child. Women working outside their residential municipality. Range: 10–50%.

Another repeated pattern is that Cadereyta does expel working women, even if they do not have a particular destination, which means that very few moves from these municipalities to any of the other 12 are made. Also, it called to our attention that when having their youngest child in the range of 10- to 17-years-old, a relatively significant number (11%) of working women of Apodaca move to San Nicolás to work.

Two repeated patterns shown in Map 6 are first that the most recurrent working destination is Monterrey, even when the origin is not an adjacent municipality, and second the labour relation between García and San Pedro Garza García. Also, it called our attention that in the case of women with children with ages between 10 and 17, in comparison with all the maps presented in this paper, this category is the one that presents a more dispersed distribution (number of arrows) of destinations, eight of the 16 arrows directed to Monterrey, and the rest are distributed between four other municipalities (San Nicolás de los Garza stands out for attracting women from 3 different places).

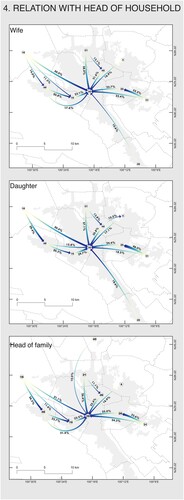

Map 6. Map of Monterrey Metropolitan Zone showing destinations who. relation to the head of the household. Women working outside their residential municipality. Range: 10–50%.

2.4. Relationship of the working woman to the head of household

This variable allows us to understand the role of the sampled women in their homes, and their duties as members of a family, which led us to imply the possible economic and domestic responsibilities.

As in the previous three variables, Cadereyta and Santiago are the municipalities that retain the largest number of working women within their borders, regardless of the category (). Also, García and Juárez are the ones that are not capable of doing the same and present the highest rates of expulsion.Footnote6 In both cases, retention and expulsion, the condition of being a daughter in these four areas supports the possibility of working outside the municipalities’ boundaries.

Table 4. Percentage of Retained (Ret) and Expulsion (Exp) working women (ww) by relation to the head of household, by municipality.

When comparing the categories of those capable to travel to other municipalities to work in Map 3, we can see that being a daughter seems to be the best condition to get a job further away i.e. the higher rates for the same destination most of the time, while being a wife is the most restrictive category. Being the head of the household might imply a weaker attachment to the geographical location of the household, besides their responsibility for reproductive duties.

Once more, we can observe patterns in Map 6: most trips for work are done to Monterrey regardless of the type of relationship with the head of the household or the residential location of the working women. The presence of a labour relationship between García (the origin) and San Pedro Garza García (the destination). As seen before, the few working women travelling from Cadereyta to any other municipality, do not show any preferred destination, and in the case of Santiago, being the head of the household limits their possibilities to work outside its boundaries.

3. Discussion and conclusion

The functional division of urban activities (mainly work and residence) has led people to use urban space differently and, for our study, has a direct impact on the women’s participation in the labour market. This is mainly due to the time and costs it takes to commute, considering that women’s social role demands their presence in and around the home for most of the day.

Our research shows this limitation or spatial segregation around the municipality of residence, which tends to be more evident as the variables studied represent greater reproductive works. Correspondences are observed between the geographic location of women’s paid work and marital status, the number of children, the age of the youngest child, and relationship with the head of the household.

We observed that working women in the MMZ with fewer opportunities to leave their municipality reasons are those who live with a partner, those with more than one child, those with at least one child between the ages of 0 and 9, or those identified as the head of the household, given their dual reproductive/productive role. In other words, these women are more likely to suffer spatial segregation on an urban scale due to their economic activity.

Moreover, studies on the Mexican context that analyse urban structure and form, as well as the structure and concentration of jobs within the city (CitationGuerra et al., 2018; CitationMonkkonen et al., 2018, Citation2020; CitationSuárez Lastra & Delgado Campos, 2007), allow us to see a little further. Since such studies observe the highest concentrations of employment in the urban geographic centre, we can assume that women with greater urban and economic segregation are those who inhabit peripheral areas, commonly related to lower income and education level. These conditions, coupled with high domestic workloads, would pose a significant challenge.

This study raised relevant questions related to the type of economic/working activity these women carry out, if the salary is significantly different between jobs according to their location, and what type of paid work and income level can aspire a woman with a strong reproductive workload. Possible answers to these issues can be found in the Doctoral dissertation by CitationHernández-Reyes (2021).

NOTE. We consider it necessary to point out the patriarchal influence in the language used by the institutional apparatus of our country (Mexico), which is reflected in the census data analysed.

The term working women (translated from Spanish mujeres ocupadas) states that women who do not carry out some type of economic activity classified in the census do not work, even when they do some other sort of activity, e.g. domestic and caregiving work. It only gives value to paid work and makes invisible the rest of the tasks that do not involve a monetary flow. CitationPérez Orozco (2014) points out that the androcentric bias on which notions such as those of economy and work ‘are founded on the absence of women, denies economic relevance to spheres associated with femininity (the private-domestic sphere, the home, and unpaid work), and uses the male experience in markets to define economic normality’ (p. 37).

The other term we would like to point out is head of household. It indicates the millenary inheritance of the archaic state in the organisation of present-day Western society. Since then, men family head, the patriarch, ‘allocated the resources of society to their families the way the state allocated the resources of society to them’ (CitationLerner, 1990, p. 315). The economic aspect is once again at the centre of daily life, the axis around which the rest of the activities that make up daily life revolve.

It is necessary to recognise that under the patriarchal influence, significant omissions are made, such as the fact that the database consulted (the Census sample) does not contain information related to the paternity of men. It is not possible to know whether men are fathers and, much less, how many children they have, perhaps because having children is exclusively feminine.

All the above is evidence of the durability and permeability of a social model whose development began very long ago: the patriarchal system, which reaches areas as disparate as the city and language.

Software

Data input, processing, editing, and map design were performed using QGIS 3.14.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (7.4 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the help of Edgar Alán Egurrola Hernández from the Observatorio de Ciudades (Tecnologico de Monterrey), who helps us to improve our maps.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Repositorio Tec: ‘Base de datos analizada. Muestra censal 2010’ at https://repositorio.tec.mx/handle/11285/641532.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For this article, we are using the term working women to refer to those women who receive a salary for their work, and it is not related to their own reproductive work.

2 The study used the available data when the Doctoral research was conducted.

3 ‘For the 2010 census sample, an expanded questionnaire was designed, with which around 2.9 million dwellings in the country were censused, selected using probabilistic criteria’ (CitationINEGI, 2016b). The whole document explaining the criteria used for the Census sample is available at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/ccpv/2010/doc/diseno_de_la_muestra_censal.pdf

4 We are not considering the municipality of Monterrey because it is the core of the whole Metropolitan Area.

5 Women that have no children because they only represent 0.14% of the sampled population of working women.

6 On average, 65% and 70% of the working women must travel to another municipality.

References

- Ellegård, K., & Vilhelmson, B. (2004). Home as a pocket of local order: Everyday activities and the friction of distance. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(4), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00168.x

- Fanning Madden, J. (1981). Why women work closer to home. Urban Studies, 18(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988120080341

- Graser, A., Schmidt, J., Roth, F., & Brändle, N. (2019). Untangling origin-destination flows in geographic information systems. Information Visualization, 18(1), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473871617738122

- Guerra, E., Caudillo, C., Monkkonen, P., & Montejano, J. (2018). Urban form, transit supply, and travel behavior in Latin America: Evidence from Mexico’s 100 largest urban areas. Transport Policy, 69, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.06.001

- Hanson, S., & Pratt, G. (1991). Job search and the occupational segregation of women. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 81(2), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01688.x

- Hanson, S., & Pratt, G. (2003). Gender, work and space. Routledge.

- Hernández-Reyes, M. (2021). El uso femenino del espacio urbano por razones laborales y su relación con la actividad no remunerada de la mujer. Evidencias geográficas en la zona metropolitana de Monterrey (ZMM) [Tecnologico de Monterrey]. https://repositorio.tec.mx/handle/11285/637315

- INEGI. (2016a, January 1). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. INEGI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/

- INEGI. (2016b, January 1). Muestra (cuestionario ampliado). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. INEGI; INEGI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/default.html#Microdatos

- Lerner, G. (1990). La creación del patriarcado. Crítica.

- McDowell, L. (2000). Género, identidad y lugar: Un estudio de las geografías feministas (Vol. 60). Universitat de València.

- Mojica Segovia, A. C. (2014). Hábitat urbano y vida cotidiana: Una mirada de género a la organización espacio-temporal de las actividades en León, México. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Monkkonen, P., Comandon, A., Montejano Escamilla, J. A., & Guerra, E. (2018). Urban sprawl and the growing geographic scale of segregation in Mexico, 1990–2010. Habitat International, 73, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.12.003

- Monkkonen, P., Montejano, J., Guerra, E., & Caudillo, C. (2020). Compact cities and economic productivity in Mexico. Urban Studies, 57(10), 2080–2097. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019869827

- Moser, C. O. N. (1989). Gender planning in the third world: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Development, 17(11), 1799–1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(89)90201-5

- Næss, P. (2006). Urban structure matters: Residential location, car dependence and travel behaviour (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Pérez Orozco, A. (2014). Subversión feminista de la economía: Aportes para un debate sobre el conflicto capital-vida. Traficantes de Sueños. https://www.traficantes.net/sites/default/files/pdfs/Subversi%C3%B3n%20feminista%20de%20la%20econom%C3%ADa_Traficantes%20de%20Sue%C3%B1os.pdf

- Salazar Cruz, C. E. (1999). Espacio y vida cotidiana en la Ciudad de México. El Colegio de México. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv3f8qgp

- SEDESOL, CONAPO, & INEGI. (2012). Delimitación de las zonas metropolitanas de México 2010 (pp. 1–214). http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Zonas_metropolitanas_2005

- Suárez Lastra, M., & Delgado Campos, J. (2007). Estructura y eficiencia urbanas. Accesibilidad a empleos, localización residencial e ingreso en la ZMCM 1990–2000. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio, VI(023), 693–724.

- Valcárcel, A. (2013). Feminismo en el mundo global. Ediciones Cátedra.