ABSTRACT

Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) remains one of the most significant problems affecting women globally with its elimination being central to achieving SDG 5 on gender equality. While information on its prevalence is increasing globally, this is often at the national scale with limited local-level data. Responding to feminist critiques of SDG 5 and target 5.2 in terms of the importance of capturing more nuanced data on grassroots women’s experiences as agents rather than victims, this paper reflects on countermapping VAWG in the favelas of Maré in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Drawing on countermapping methodologies, it analyses a series of countermaps highlighting the prevalence of VAWG, but also the need to report and resist it locally. Only by revealing the complexity of VAWG and women’s practices to deal with it can such violence be truly eliminated in order to meet SDG 5 and target 5.2.

1. Introduction

Brazil is one of the most violent countries for women and other gender and sexual minoritized groups, particularly intersecting with race and disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. It ranks fifth in the world for femicides (CitationWaiselfisz, 2015) with rates increasing, especially since the advent of COVID-19 (CitationFBSP, 2020). Indeed, one woman is killed every four hours in Brazil (CitationIPEA, 2020) and the country has a daily rate of 4.3 female homicides per 100,000 women, which is almost twice the global rate (CitationUNODC, 2019).

More widely, gender-based violence is endemic globally, specifically that perpetrated against women and girls. Such violence is now recognised as a major impediment to achieving gender equity and to meeting the aims of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indeed, one of the main achievements of the transition from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to the SDGs, was the inclusion of the elimination of violence against women and girls (VAWG) within SDG 5 on achieving gender equality (included in target 5.2) (CitationAzcona & Bhatt, 2020). As we rapidly approach the target year of the United Nations Agenda 2030, this paper interrogates the effectiveness of a technocratic perspective using statistical information in monitoring progress towards SDG 5 (CitationEsquivel, 2016), particularly within marginalised and racialised urban communities facing where lack of accurate data on gender-based violence is a perennial challenge. We focus on alternative ways to monitor experiences of combatting VAWG in a group of favelas in Rio de Janeiro, Maré, where we developed a collaborative feminist approach to countermapping VAWG with a grassroots organisation.

2. SDG 5, gender data gaps and countermapping

While SDG 5 (and SDG 16 on the need to ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’) has been welcomed among researchers and practitioners alike (CitationBabu & Kusuma, 2017), questions remain around the conceptual and practical implications of eliminating violence against women and girls. Conceptually, debates continue around difficulties of addressing structural gendered power relations that underpin VAWG through the SDGs and how women are constructed as vulnerable victims rather than agents of change. This is further compounded by the neglect of grassroots women’s experiences in the SDG process, and that Agenda 2030 is based on a dominant neoliberal economic agenda that is arguably antithetical to gender transformation (CitationStruckmann, 2018).

More practically, the ‘gender data gap’, referring to the lack of gender-disaggregated statistical information undermines accurate monitoring of the SDGs, especially in terms of VAWG, due to widespread under-reporting to public institutions (CitationFuentes & Cookson, 2020). The over-emphasis on quantitative data by the SDG framework obscures the realities of women’s lives in qualitative terms resulting in the neglect of the causes of gendered inequalities and violence (CitationBradshaw et al., 2017). Furthermore, the SDGs focus predominantly on the national scale in terms of the prevalence of gendered violence with little consideration of local patterns (CitationFuentes & Cookson, 2020), despite some recent shifts towards using crowdsourced geospatial data at micro-levels.Footnote1

Beyond SDG 5 and target 5.2, mapping VAWG has a long history ranging from ‘live’ maps of urban hotspots linked with mobile phone apps, such as those associated with SafetiPin in India (CitationViswanath & Basu, 2015) to those using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to map specialised service provision for women survivors at national scales (CitationCoy et al., 2011 on the UK) or femicides (CitationFonseca-Rodríguez & San Sebastián, 2021 on Ecuador). There has also been considerable engagement with mapping violence using participatory visual methods (CitationMoser and McIlwaine, 2004), some of which also work with arts-based methodologies (CitationAlonso-Sanz, 2020), combine GIS mapping with creative and qualitative or survey data inputs (CitationRenold, 2018) or entail concept mapping (CitationO’Campo et al., 2017).

Reflecting on feminist critiques of the SDGs and taking a lead from calls to ‘widen the catchment of data’ for understanding the impact of gender-based violence (CitationFuentes & Cookson, 2020, p. 894), this paper suggests that quantitative approaches that measure, monitor and map national-level prevalence of VAWG require more nuanced perspectives. Recognising the intersectional socio-spatial dimensions of VAWG (CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2020), we suggest that this can be addressed through countermapping.

Countermapping involves challenging dominant power structures and hegemonic narratives at the community level first coined by Nancy CitationPeluso (1995) with reference to forest resource mapping in Indonesia. It is a specific form of critical cartography that challenges cartographic conventions and assumptions (CitationHarris & Hazen, 2005) and aims to empower marginalized communities and individuals (CitationCounter Cartographies Collective et al., 2012). While this may take different forms, here we focus on combining GIS with qualitative data and survey research in urban settings to produce counter-narratives about a community based on local territorial knowledge shared among residents but typically overlooked in official, quantitative maps. Producing countermaps requires innovative methods – including participatory and co-produced approaches – to identify the nature of social problems and how they are dealt with locally to engender more effective policy designs. In terms of monitoring progress on eliminating VAWG, this entails understanding the various ways violence is tackled by women within their communities, as informed agents who create strategic and effective responses.

3. Situating violence against women and girls in Rio de Janeiro and Maré: background and methods

Empirically, we draw on recent research in the favelas of Maré in the northern part of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a marginalised and racialised community marked by endemic urban violence and high incidence of VAWG, but also where women residents have created resourceful ways to resist such violence. This location is especially important given that favelas are historically neglected and lack of data to inform policy is a key factor perpetuating social problems, specifically gender-based violence (CitationMotta, 2019). Classified by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics as ‘subnormal agglomerates’, favelas have only recently been included in the Brazilian census and other national household surveys. However, integrated statistics remain non-existent in over 1,000 favelas in Rio, with many favelas remaining uncharted (CitationRizzini Ansari, 2022). This includes information on women’s experiences of VAWG despite a broad national-level commitment to the MDGs (but not the SDGs) (CitationIPEA, 2014).Footnote2

Therefore, we developed participatory countermapping methodologies linking a quantitative survey (with 801 women in 2018) together with 32 in-depth qualitative interviews and five focus groups with women survivors, and nine semi-structured interviews with female community actors all conducted in Portuguese in 2020 and 2021 with full ethical approvals. The survey was adapted from the CitationEU Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014) questionnaire on gender-based violence that addresses types of violence experiences, perpetrators and nature of reporting. The survey was conducted using random sampling in 15 of the 16 favelas that make up Maré (see CitationKrenzinger et al., 2018; CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2022a for further details). The main research on which this paper draws was a co-created participatory method to collect the perspectives of four stakeholders from a women’s support organisation in Maré. This group participated in three discussion sessions discussing the research findings and locating key points on the map of Maré. This involved mapping unsafe and potent sites (following CitationGago, 2020] idea of ‘feminist potencia’; see also CitationFernandes et al., 2018), examining how and why women report VAWG and/or how they develop agency in relation to the development of community and women-led initiatives within marginalised urban communities as well as creating a concept map to outline their resistance practices.

The resulting (counter)maps presented here aimed to capture aspects of lived experiences and everyday tactics developed by women to cope with and resist VAWG, something neglected in the SDG conceptualisation of VAWG. The maps highlight the global challenges of addressing violence against women in urban margins who are otherwise invisible and/or constructed as victims and suggest that their inventive strategies must be accounted for in global debates on SDG 5.

This must be situated within a wider violent history and geography of gender and racial injustice, the state of Rio de Janeiro has some of the highest indicators of urban violence in Brazil. In 2019, there were 1534 victims per 100,000 with 15 victims per hour. Most were black (68%), aged 30–59 (58%), attacked inside their household (79%), at night (40%), by partners or former partners (82%) (CitationMendes et al., 2020). In 2020, there were 78 feminicides (referring to the murder of women because of their gender, often with direct and indirect support from the state – see CitationFregoso & Bejarano, 2010), where 78% were committed by partners or former partners (CitationInstitute of Public Security, 2021).

In addition to direct forms of VAWG, women residing in favelas are affected by specific forms of direct, indirect and symbolic violence inherent to the favelas’ racial-spatial-economic marginalisation (CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2021). The widespread militarization of public security policy produces further armed and lethal violence that significantly impacts the lives of women in peripheries (CitationBarros & Guariento, 2019). Despite this, women in favelas are important protagonists in the networks of families of victims of institutional violence, fighting for justice as well as facing harsh repression. However, there are few official records of VAWG or of women’s responses to it, which is the focus of the research reported here.

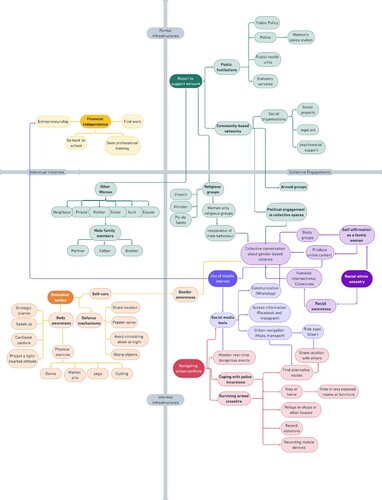

In terms of the specific situation of Maré (see ), it is one of the largest and most complex groups of favelas in Brazil. Maré is affected by high levels of poverty, inequality, drug-trafficking and public insecurity. Thanks to a community-led census, data show that there are 140,000 people residing there, of which 51% are women, 45% who are sole heads of household, with 62% identifying as mixed-race or black (CitationRedes da Maré, 2013). Maré is territorially controlled by several armed groups who act as perpetrators and agents of paralegal state governance (CitationSilva, 2015). Maré is frequently occupied by state security forces resulting in systematic violence against residents, male and female, through police incursions (CitationWilding, 2014). Yet Maré is also a locus of historical social struggles around securing infrastructure and challenging violence to which the paper now turns.

Figure 1. Map of Maré in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro showing women residents’ knowledge of the territory regarding armed violence, safety, potencia.

The research discussed here aimed to identify alternative ways to understand the nature of VAWG in Maré and how women self-organise to eliminate it – in line with SDG 5 and target 5.2. Given the dearth of data, we developed an interdisciplinary, co-produced, collaborative feminist approach with a grassroots organisation to countermap the prevalence of VAWG and explore the nature of resistance to it.

4. Tracing and resisting violence against women and girls through countermapping in Maré, Rio de Janeiro: main findings

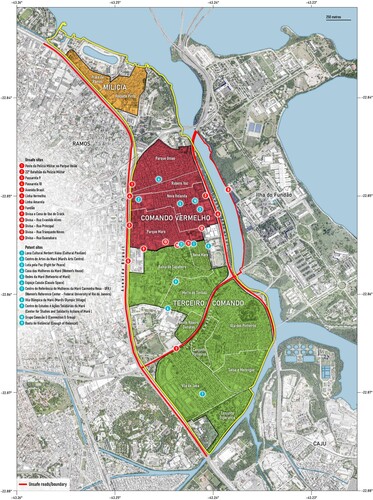

Addressing SDG 5 and target 5.2 requires providing data on the prevalence of VAWG as a precursor to eliminating it. This is notoriously difficult at the national level and even more challenging in poor urban peripheries who are often invisibilised and stigmatised. Given the lack of statistical data on VAWG in Maré, we conducted a survey with 801 women in 2018 across 15 of the 16 favelas that constitute the complex (see above). Overall, it showed that 57% of women suffered one or more forms of direct gender-based violence (34% physical, 30% sexual and 45% psychological) with young black women being most likely to have experienced it (69% of black women compared to 55% of mixed-race and 50% of white women). Intimate partners committed 47% of VAWG with more than half occurring in the public sphere (53%) (CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2021).

Reflecting the importance of acknowledging the multidimensional nature of VAWG which occurs inside the private sphere as well as in public spaces, we mapped the prevalence according to this distinction (). While within Maré as a whole, just over half of violence occurred in the public sphere (53%) compared with 47% in the private domain, this varied among the individual favelas. Not only was incidence of VAWG higher in general in some favelas, with the lowest in the southern communities, but violence in the public sphere predominated in six favelas with private sector violence predominating in five, with a further four where there was an equal split.

Figure 2. Incidence and nature of VAWG in Maré.

To explain some of these variations, a participatory map () shows the perspectives of stakeholders on locally shared knowledge to locate sites that they perceived to be unsafe for women as well as those considered as potent. The potent sites are places where women had liberating experiences momentarily or where they felt they could challenge gender-based violence. Here we use the idea of ‘feminist potencia’ following CitationGago (2020, pp. 2–3) as a concept of power incorporating individual and collective struggles among women and a desire for change.

In relation to the unsafe areas, the map reveals a series of concrete and symbolic territorial domains created by rival armed groups and the urban segregation of favelas in the context of the war on drugs (CitationSilva, 2015; CitationWilding, 2014). Marking the borders (in red) that encircle Maré are a group of motorways (Avenida Brasil, Linha Vermelha and Linha Amarela) connecting the city of Rio to the suburbs. These mark a transition between the space of favelas and the space of the city and are considered dangerous, especially at night, due to the high incidence of urban violence. Within the boundaries of Maré, other key borders delimit armed groups’ occupations and constrain free circulation of residents. shows the areas dominated by the milícias (militias) (yellow), Terceiro Comando (Third Command) (green) and Comando Vermelho (Red Command) (red). Known as divisas, these bordering areas are often delimited by barricades and the ostensible presence of firearms and crossfire. Circulation among these areas is limited for all genders, although women often fear crossing these boundaries more than men as part of wider mobility restrictions felt by women in the favelas and beyond (CitationKrenzinger et al., 2018; CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2021).

Linking and , it emerges that VAWG in the public sphere is especially prevalent in areas dominated by milícias. The predominance of violence in the private sphere is most marked in favelas dominated by the Red Command with lower prevalence in the area controlled by the Third Command where a combination of private and public sector violence is most common. This is likely to be related to how different armed groups patrol the streets, their attitudes towards women and the extent to which they intervene in domestic violence disputes. For example, it was not uncommon for gangs to provide alternative extra-judicial protection for women survivors of domestic violence if the police would not intervene. It is also likely that there are variations in how different groups censure what can and cannot be said about gender-based violence in their territories; the milícias are especially well-known to retaliate against residents who discuss problems in their areas (see CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2020).

It is also important to note that although favelas are widely known as dangerous territories, the city ‘outside’ is often perceived as riskier than ‘inside’ from the perspective of favela residents. For example, Patricia, a 31-year-old mixed-race woman who lived in the favela of Nova Holanda reflected: ‘I can feel safer in here than out there. I won't circulate in the city centre at night or at dawn, I run the risk of being raped, killed, or robbed’. In part, this is linked with the extra-judicial role played by the armed actors who provide informal protection for residents in the areas they control (see also CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2022a).

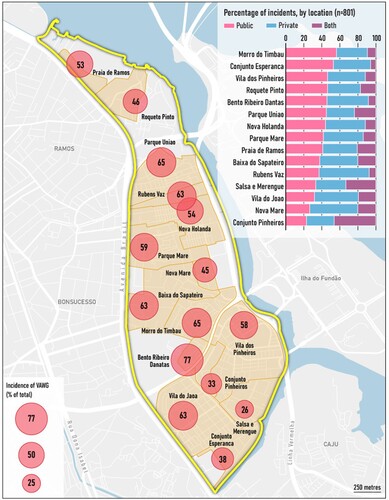

Turning to the potent sites for women in Maré, shows that most of these are community-based organisations and indicates how the potent sites are concentrated in areas where more community-based organisations and women-led initiatives are located, and whose activities foster feminist potency. This includes two women-focused organisations (Casa das Mulheres da Maré – Women’s House of Maré and Centro de Referência de Mulheres da Maré – Women of Maré’s Reference Centre run by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro). Also noted on the map was the site of the 2017 protest known as Basta da Violência! (Enough Violence!) that took place in the liminal divisa area gathering residents and local organisations against escalating state violence. This protest was repeated in 2019 and is notable due to the dominance of women protesting.Footnote3

Figure 3. Networks of support for women in Maré.

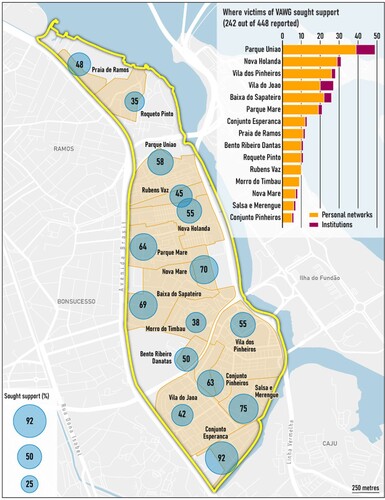

In terms of the nature of reporting of women’s experiences of violence, data from the survey showed that 52% had told someone about their experience, while 48% had not. highlights territorial variations among the favelas with reporting of VAWG more common in those with several organisations and where urban violence was more concentrated. It also differentiates between formal and informal reporting and highlights the predominance of turning to informal personal networks rather than formal institutions. Indeed, 83% of women who reported only sought informal support, with 14% seeking both formal and informal, and 2.5% only seeking formal help. Therefore, lower levels of formal reporting reflect different local codes set by armed groups as well as the presence of institutions in each favela within a wider context of a lack of faith in the judicial system. In terms of the latter, only 8% of women reported to the Women’s Police station (these are specifically oriented towards women reporting VAWG). This can partly be explained by the fact that it is located 11 km away in the city centre, as well as the lack of support provided when women do report. For example, Maria Rachel, 48, white and resident in Nova Holanda, spoke of reporting an incident and the police chief informing her that because she lived in a ‘risky area’ they could not protect her, also warning her of retaliation from the drug dealers. It is therefore not surprising that formal reporting levels are so low with important implications for eliminating violence against women through institutional mechanisms.

Figure 4. Victims reporting VAWG in Maré.

Understanding the institutional landscape in communities such as Maré is therefore essential in addressing and eliminating violence against women. Returning to , it also reflected a service mapping undertaken in Maré and illustrates the limited presence of public institutions which comprise mainly of schools and health clinics (a total of nine inside the favela). The lack of state institutions in Maré is also directly related to the predominance of civil society organisations, especially in centrally located favelas. Indeed, 17 nongovernmental organisations were identified of which nine were community-based organisations and eight were women-led initiatives, with an additional nine online groups. Women-led initiatives are especially significant in reflecting the strong role of women in the historical development of infrastructure in Maré (CitationSilva, 2015). While some of these initiatives were formal, such as the Women’s House, many were informal collective initiatives, many providing support services for women experiencing VAWG. Indeed, in 2020, the Support Network for Women in Maré (RAMM – Rede de Apoio às Mulheres da Maré) was initiated by the organisation Fight for Peace (Luta Pela Paz). It was established in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as socio-economic, health and infrastructural injustices intensified resulting in households facing severe hardships and the intensification in domestic violence. The RAMM identified the need for coordination among individuals and organisations to build joint strategies for women in Maré with a focus on VAWG. RAMM’s first action was to construct an ‘integrated workflow’ created through a participatory process for the mapping of services, policies, and meetings with representatives based on an urgent need to cooperate (CitationMcIlwaine et al., 2022b).

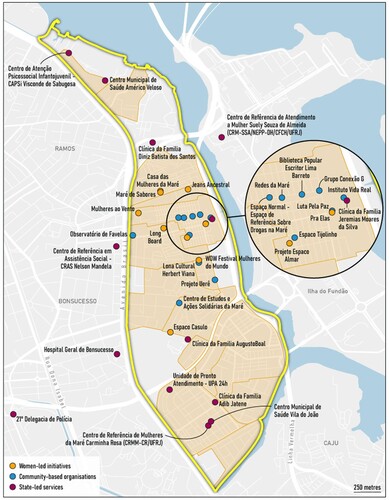

In the process of mapping the flows of interinstitutional resources and spontaneous forms of resisting violence developed by women in Maré, it became clear that a hybrid network of local practices and knowledge shared among women had been established. To capture these networks of resistance, we developed a concept map derived from the interviews with women residents and stakeholders (see ). This outlines the multiple formal and informal practices that operate individually and collectively. These focus on support networks, financial independence, mobile internet, racial-ethnic ancestry, navigating urban conflicts, and embodied practices and are essential in addressing and eliminating violence against women in the short and long term. Women use different practices simultaneously, activating resilience mechanisms and resistance processes, all of which show women as protagonists in achieving gender equality and safer cities.

5. Conclusion

This paper has developed a range of countermaps based on GIS, a survey and interview material on the nature of and resistance to VAWG in the favela of Maré in Rio de Janeiro to highlight the importance of addressing SDG 5 and target 5.2 on eliminating VAWG. While the maps illustrate the endemic nature of VAWG in one particular community, they also reveal the importance of data collection and mapping in marginalised urban spaces as well as the need to move beyond prevalence data in eliminating VAWG. In engaging with feminist critiques of SGD 5, the maps illustrate the importance of working with grassroots organisations, of understanding reporting mechanisms, and acknowledging women as protagonists rather than victims of VAWG. While institutional, legislative and policy frameworks are important in addressing SDG 5 and target 5.2, this paper has shown that it is essential to understand the complex local socio-spatial processes that inform and generate VAWG if appropriate responses are to be developed and such violence prevented and eliminated in the future. Capturing women’s lived experiences is key to this, especially the innovative ways in which they are challenging VAWG through individual, collective, formal and informal ways. The countermaps created here can provide the much-needed complexity required in understanding the complexity of VAWG that is central to meeting SDG 5 target 5.2.

Software

The initial map creation was done in QGIS, raster satellite imagery, excel files of the data and shapefiles of the regions were combined. The maps were then exported as SVGS and the final layout was designed and produced using Adobe Illustrator. Some colour adjustment, sharpening and fading of the satellite layer were done using Adobe Photoshop.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval has been granted for this research from the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (HR-19/20-18918).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (53.6 MB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andreza Dionisio Pereira who also contributed to the fieldwork in Maré as well as Paul Heritage and Renata Peppl from Queen Mary University of London and People’s Palace Projects, Eliana Sousa Silva from Redes da Maré and Miriam Krenzinger from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. We are grateful to Maikon Saldanha who provided the base map of Maré and to Steven Bernard who developed the cartographic design and maps. Most of all we extend our gratitude to the women of Maré who were interviewed as part of this research.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Open Mapping for SDGs (https://sdgs.hotosm.org/) (retrieved 27 January 2022).

2 The federal government has recently stopped SDG monitoring which is now exclusively conducted by a civil society coalition which found alarming setbacks in public policies for women (CitationCSWG, 2030A, 2021).

3 See https://g1.globo.com/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/marcha-reune-quatro-mil-pessoas-pelo-fim-da-violencia-na-mare.ghtml (accessed 21 January 2022) (2017 event); https://mareonline.com.br/ato-na-mare-reune-moradores-e-organizacoes-locais-pelo-fim-da-violencia-na-mare/ (accessed 21 January 2022) (2019 event).

References

- Alonso-Sanz, A. (2020). Mapping of sexist violence in Valencia (Spain). Matter: Journal of New Materialist Research, 1(2), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1344/jnmr.v1i2.31839

- Azcona, G., & Bhatt, A. (2020). Inequality, gender, and sustainable development: Measuring feminist progress. Gender & Development, 28(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2020.1753390

- Babu, B., & Kusuma, Y. (2017). Violence against women and girls in the sustainable development goals. Health Promotion Perspectives, 7(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpp.2017.01

- Barros, R., & Guariento, S. (2019). Mapeamento de fluxos de atendimento para mulheres. FASE. https://fase.org.br/pt/acervo/biblioteca/mapeamento-de-fluxos-de-atendimento-para-mulheres/

- Bradshaw, S., Chant, S., & Linneker, B. (2017). Gender and poverty: What we know, don’t know, and need to know for agenda 2030. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(12), 1667–1688. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1395821

- Counter Cartographies Collective, Dalton, C and Mason-Deese, L. (2012). Counter (mapping) actions: Mapping as militant research. ACME, 11(3), 439–466. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/941

- Coy, M., Kelly, L., Foord, J., & Bowstead, J. (2011). Roads to nowhere? Mapping violence against women services. Violence Against Women, 17(3), 404–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211398637

- CSWG 2030A [Civil Society Working Group for the 2030 Agenda]. (2021). 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Spotlight report 2021 Brazil synthesis. https://gtagenda2030.org.br/relatorio-luz/relatorio-luz-2021/

- Esquivel, V. (2016). Power and the sustainable development goals: A feminist analysis. Gender & Development, 24(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2016.1147872

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey. European Union.

- FBSP [Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública]. (2020). Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública. https://forumseguranca.org.br/anuario-brasileiro-seguranca-publica/

- Fernandes, F. L., Silva, J. D., & Barbosa, J. (2018). The paradigm of potency and the pedagogy of coexistence. Periferias, 1(1). https://revistaperiferias.org/en/materia/the-paradigm-of-power-and-the-pedagogy-of-coexistence/

- Fonseca-Rodríguez, O., & San Sebastián, M. (2021). “The devil is in the detail”: geographical inequalities of femicides in Ecuador. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01454-x

- Fregoso, R. L., & Bejarano, C. (2010). Terrorizing women: Feminicide in the américas. Duke University Press.

- Fuentes, L., & Cookson, T. (2020). Counting gender (in)equality? A feminist geographical critique of the ‘gender data revolution’. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(6), 881–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1681371

- Gago, V. (2020). Feminist international. Verso.

- Harris, L. M., & Hazen, H. D. (2005). Power of maps: (counter) mapping for conservation. ACME, 4(1), 99–130. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/730

- Instituto de Segurança Pública. (2021). Dossiê Mulher 2021. http://arquivo.proderj.rj.gov.br/isp_imagens/uploads/DossieMulher2021.pd

- Ipea [instituto de pesquisa econômica aplicada]. (2014). Objetivos de desenvolvimento do milênio - relatório nacional de acompanhamento. IPEA. http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/3205

- Ipea [instituto de pesquisa econômica aplicada]. (2020). Atlas da violência 2020. IPEA. https://www.ipea.gov.br/atlasviolencia/

- Krenzinger, M.,McIlwaine, C., Sousa Silva, E., & Heritage, P. (2018). Dores que libertam: Falas de mulheres das favelas da maré. Appris Editora.

- McIlwaine, C., Krenzinger, M., Rizzini Ansari, M., Evans, Y., & Sousa Silva, E. (2021). Negotiating women’s right to the city: Gender-based and infrastructural violence against Brazilian women in London and residents in Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Revista de Direito da Cidade, 13(2), 954–981. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/154309041/Published_Paper_Revista_Direito_da_Cidade_Vol_13_n_2_2021.pdf

- McIlwaine, C., Resende, N., Rizzini Ansari, M., Dionísio, A., Leal, J., Vieira, F., Krenzinger, M., Heritage, P., Peppl, R., & Silva, E. (2022a). Resistance practices to address gendered urban violence in maré, Rio de janeiro. King's College London.

- McIlwaine, C., Evans, Y., Krenzinger, M., & Sousa Silva, E. (2020). Feminised urban futures, healthy cities and violence against women and girls. In X. Keith, & X. Santos (Eds.), Urban transformations and public health in the emergent city (pp. 55–78). Manchester University Press. https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526150943/9781526150943.00008.xml

- McIlwaine, C., Krenzinger, M., Rizzini Ansari, M. C., Resende, N., Gonçalves Leal, J., & Vieira, F. (2022b). Building emotional-political communities to address gendered violence against women and girls during COVID-19 in the favelas of Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Social and Cultural Geography. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2022.2065697

- Mendes, A., Rolim, L., Carvalho, P., Campagnac, V., & Cortes, V. (2020). Dossiê Mulher 2020. Instituto de Segurança Pública. http://www.isp.rj.gov.br/Conteudo.asp?ident=48

- Moser, C., & Mcilwaine, C. (2004). Encounters with violence in Latin America: Urban poor perceptions from Colombia and Guatemala. Routledge.

- Motta, E. (2019). Resistência aos números: A favela como realidade (in)quantificável. Mana, 25(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-49442019v25n1p072

- O’Campo, P., Zhang, Y. J., Omand, M., Velonis, A., Yonas, M., Min, A., Cyriac, A., Ahmad, F., & Smylie, J. (2017). Conceptualization of intimate partner violence: Exploring gender differences using concept mapping. Journal of Family Violence, 32(3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9830-2

- Peluso, N. (1995). Whose woods Are these? Counter-mapping forest territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Antipode, 27(4), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.1995.tb00286.x

- Redes da Maré. (2013). Censo populacional da maré. https://apublica.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/07/censomare-web-04mai.pdf

- Renold, E. (2018). ‘Feel what I feel’: Making da(r)ta with teen girls for creative activisms on how sexual violence matters. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1296352

- Rizzini Ansari, M. (2022). Cartographies of poverty: Rethinking statistics, aesthetics and the law. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 40(3), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758221075350

- Silva, E. (2015). Testemunhos da Maré. Mórula.

- Struckmann, C. (2018). A postcolonial feminist critique of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: A South African application. Agenda (durban, South Africa), 32(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2018.1433362

- UNODOC [United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime]. (2019). Global study on homicide. UNODOC. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet_5.pdf

- Viswanath, K., & Basu, A. (2015). Safetipin: An innovative mobile app to collect data on women's safety in Indian cities. Gender & Development, 23(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1013669

- Waiselfisz, J. (2015). Mapa da Violência 2015. Homicídios de Mulheres no Brasil. FLACSO Brasil. http://www.onumulheres.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/MapaViolencia_2015_mulheres.pdf

- Wilding, P. (2014). Gendered meanings and everyday experiences of violence in urban Brazil. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(2), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.769430