ABSTRACT

Introduction: In the treatment of house dust mite (HDM) respiratory allergic disease, allergy immunotherapy constitutes an add-on treatment option targeting the underlying immunological mechanisms of allergic disease. However, for the treatment of HDM allergic asthma, the use of subcutaneous allergy immunotherapy (SCIT) has been limited by the risk of systemic adverse events. Thus, sublingually administered allergy immunotherapy (SLIT) has been investigated as a treatment option with an improved tolerability profile that allows for safer treatment of patients with HDM allergic asthma.

Areas covered: In this Drug Profile, we provide a review of the clinical data behind the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, which was recently approved for the treatment of HDM allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis by regulatory authorities in several European countries.

Expert commentary: The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is the first allergy immunotherapy to be tested prospectively in patients with asthma, and to favorably modify patient relevant end points such as requirement for inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) or the time to first asthma exacerbation upon ICS reduction, suggesting that SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment may contribute to improving overall asthma control.

1. Introduction

The house dust mite (HDM) is a major source of indoor allergens and represents a significant factor in the development of respiratory allergic disease [Citation1]. Clinical manifestations of HDM respiratory allergic disease include allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma, and the frequent comorbidity of the two underlines the continuity of the airways [Citation2,Citation3]. HDM allergy is one of the most common forms of inhalant allergy, with global prevalence estimates suggesting that 1–2% of the world’s population may be affected [Citation4]. Accordingly, HDM sensitization, as detected by the presence of HDM-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E, is one of the most frequently observed sensitizations, with average prevalence levels of 21% and 28% reported in European and U.S. populations, respectively [Citation5–Citation7].

Epidemiological studies suggest that HDM is the most common allergen associated with asthma [Citation8]. Among adult patients with HDM respiratory allergy, almost all suffer from HDM allergic rhinitis and approximately half also suffer from HDM allergic asthma. Thus, nearly all patients with HDM allergic asthma also suffer from HDM allergic rhinitis [Citation9]. Among children and adolescents, HDM allergens are particularly important, as HDM sensitization in early childhood has been identified as an important risk factor for the development of asthma later in childhood [Citation10,Citation11]. Further, HDM sensitization is linked to a chronic course of asthma characterized by impaired lung function in school-age children [Citation11,Citation12] and persistence of asthma into adulthood [Citation13].

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation. It is defined by the presence of variable expiratory airflow limitation and a history of respiratory symptoms (wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, or cough) that vary in intensity over time [Citation14]. For allergic asthma, respiratory symptoms and airway impairment are triggered by allergen exposure and in this context, skin prick testing and evaluation of specific IgE levels in serum can aid in confirming a suspected allergic asthma diagnosis.

For patients suffering from HDM allergic asthma, perennial exposure to HDM allergens results in chronic persistent symptoms with little if any seasonal fluctuations throughout the year [Citation15,Citation16]. While allergen avoidance has been investigated as a way to reduce HDM allergen levels and symptoms, the majority of interventions have failed to provide a significant clinical benefit [Citation17–Citation19]. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guideline recommends a stepwise approach to symptom control and risk reduction [Citation14]. One or more daily controller medications provide regular maintenance treatment and ongoing treatment adjustments may involve an increase in daily dose or adding additional controller treatment if the patient is not well controlled. Similarly, ongoing treatment adjustments may involve a step-down in treatment once good asthma control has been maintained for 3 months. In this treatment algorithm, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) represent the initial controller option, which may be combined with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) with increasing disease severity and inadequate symptomatic control. In addition, short-acting β2-agonists (SABA) are provided to all asthma patients for as-needed relief of breakthrough symptoms. The current GINA guideline mentions allergy immunotherapy (AIT) as a non-pharmacological intervention that may assist in improving symptom control and/or reducing future risk [Citation14]. As noted in the guideline, the evidence level for AIT in asthma treatment is very low (evidence level D) and the GINA position on AIT recommends that physicians weigh potential benefits of AIT against the risk of adverse effects and the practical challenges involved [Citation14].

AIT involves repeated administration of allergen to allergic subjects in order to induce immunological tolerance to the specific allergen and ameliorate symptoms associated with subsequent allergen exposure [Citation15]. The mechanism behind AIT-induced tolerance appears to involve a shift in the balance between Th2 and Treg responses, accompanied by increased numbers of Treg cells and suppression of effector T cell function [Citation20]. Thus, as AIT targets the underlying immunological mechanisms of allergic disease, treatment is likely to result in clinical effects on all manifestations of respiratory allergic disease. Consequently, for HDM respiratory allergic disease, AIT may provide simultaneous clinical benefit in allergic asthma as well as allergic rhinitis. Further, AIT represents the only treatment option with a potential for long-term post-treatment efficacy and modification of the natural course of allergic disease [Citation15,Citation21].

Historically, AIT has been administered as subcutaneous injections with allergen extracts specific for patients’ sensitization(s) and history of disease. Current treatment guidelines for subcutaneously administered AIT (SCIT) recommend a treatment period of 3 years [Citation15], with frequent (at least weekly) injections during an initial up-dosing period of a few months followed by a period of maintenance dose injections every 4–6 weeks. However, as mentioned, due to the low level of evidence of effect and the fact that asthma constitutes a known risk factor for systemic allergic reactions, SCIT treatment of allergic asthma has generally not constituted a recommended treatment option.

In this context, sublingually administered AIT (SLIT) meets an unmet medical need. Local administration of allergen extracts as sublingual tablets or drops appears to modify similar immunological mechanisms as when extracts are delivered subcutaneously [Citation22,Citation23]. Importantly, the safety profile observed with SLIT involves a lower risk of systemic adverse reactions [Citation24] and this improved risk-benefit profile suggests that SLIT may represent a novel AIT treatment option for patients with allergic asthma. In addition, as the safety profile observed with SLIT allows for daily at-home administration [Citation25,Citation26], SLIT represents a more convenient AIT treatment option compared to the many doctor’s visits involved in a typical SCIT treatment regimen [Citation27].

2. HDM SLIT-tablet treatment of HDM-induced allergic asthma

2.1. Market overview

Since current treatment guidelines do not recommend AIT as a treatment option for HDM allergic asthma [Citation14], the use of AIT for the treatment of allergic asthma has been very limited. As the GINA position has partly been based on the inherent risk of systemic allergic reactions associated with SCIT [Citation14], SLIT products and the more favorable safety profile they offer, may represent a novel treatment option for patients with allergic asthma. Currently, the market of SLIT-tablets aimed at the treatment of HDM allergic asthma revolves primarily around two formulations, as reviewed elsewhere [Citation28] and outlined in brief below.

The topic of this Drug Profile is the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (ACARIZAX®, ALK, Denmark; Miticure®, Torii, Japan; MK-8237, Merck, USA), which was recently approved by regulatory authorities in Europe for the treatment of HDM allergic asthma as well as HDM allergic rhinitis and in Japan for the treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis [Citation29]. Currently, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet represents the only SLIT-tablet registered for the treatment of both HDM allergic asthma and HDM allergic rhinitis.

Further, a HDM SLIT-tablet developed by Shionogi and Stallergenes (Actair®) has been approved for the treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis by Japanese regulatory authorities based on data confirming efficacy and safety of the tablet in the treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis [Citation30].

Finally, a sublingual allergoid tablet developed by Lofarma (Lais®) which contains HDM allergens modified by carbamylation is available in a number of countries on a named-patient product basis for the treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis [Citation31,Citation32]. This product is undergoing further clinical development in order to support a future marketing authorization application.

Thus, the market of SLIT-tablets for treating HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease includes several products for the treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis. In addition, the regulatory approval of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet for treatment of HDM allergic asthma represents an acknowledgment that SLIT-tablets constitute a novel treatment option for patients with HDM allergic asthma, which may help meet the unmet medical need of patients with HDM allergic asthma.

2.2. Introduction to the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet

2.2.1. Chemistry

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is a fast-dissolving freeze-dried tablet containing extracts from the two HDM species Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and D. farinae. Thus, the tablet contains all D. pteronyssinus and D. farinae allergens contained in the extracts of the two species. A highly standardized production process ensures a 1:1:1:1 ratio of the major allergens Der p 1, Der f 1, Der p 2, and Der f 2 in the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet [Citation33]. D. pteronyssinus and D. farinae represent the two most commonly occurring HDM species worldwide, and the group 1 and group 2 allergens are the most frequent and clinically relevant HDM allergens [Citation16].

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is formulated for daily, at-home sublingual administration, utilizing a well-established formulation technology (Zydis®, Catalent, UK). Manufactured by a freeze-drying process, this dosage form consists of the drug substance physically entrapped or dissolved within the matrix of a fast-dissolving carrier material designed to dissolve rapidly in the mouth [Citation34,Citation35]. Administration of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet involves placing the freeze-dried tablet under the tongue from where it will dissolve within seconds.

2.2.2. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism

As traditional pharmacokinetic studies are not possible with AIT [Citation36], no clinical studies have been conducted to investigate the pharmacokinetic profile and metabolism of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. This reflects the finding that plasma levels of intact HDM allergen remain below detection limits after sublingual administration [Citation36–Citation38]. Upon sublingual administration, allergen is presumably taken up by dendritic cells, particularly Langerhans cells, of the oral mucosa and presented to other cells of the immune system [Citation20,Citation39,Citation40]. As the active components of allergen extracts are composed of polypeptides and proteins, allergen molecules not taken up by antigen-presenting cells are believed to undergo enzymatic hydrolysis during passage through the gastrointestinal tract. Accordingly, there is no evidence suggesting that intact allergen enters the systemic circulation after sublingual administration and there are no reports that SLIT affects renal or hepatic function.

2.2.3. Pharmacodynamics

Since formal pharmacodynamic studies are not possible for allergen products, evaluation of the impact of AIT on specific immune parameters, including allergen specific Ig levels, is recommended during AIT product development [Citation36]. Tolerance induction during AIT involves changes in T cell responses as well as antibody responses to the specific allergen. The current understanding of the mechanism of AIT involves a shift in the balance between Th2 and Treg responses mediated by antigen-presenting cells [Citation41]. Allergic symptoms result from IgE-mediated degranulation of mast cells, and the production of IgE results from a switch in B cells, which is mediated by IL-4 produced by Th2 cells. Thus, a shift toward Treg may potentially inhibit the Th2 mediated influences on B cell Ig secretion [Citation28]. For instance, serum levels of allergen-specific IgE are known to transiently increase after AIT initiation and then gradually decrease over months or years [Citation41]. However, while these fluctuations in IgE levels indicate AIT modulation of underlying immunological mechanisms, IgE levels represent a poor predictor of clinical improvement during AIT [Citation42–Citation44]. In contrast, increased serum levels of allergen-specific IgG, and particularly IgG4, are consistently observed with AIT [Citation45,Citation46], and IgG may inhibit IgE binding to allergen in a competitive manner [Citation22,Citation47]. Thus, the inhibitory activity against allergen-specific IgE has been suggested as a relevant measure that may explain the observed treatment-induced changes in the levels of Ig secretion and some of the clinically observed effects of AIT in trial populations [Citation41,Citation48].

For the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, several clinical trials have included measurement of allergen-specific IgE, IgG4, and the inhibitory activity against IgE, as assessed by IgE-blocking factor (IgE-BF). Two phase I trials investigated the tolerability and acceptable dose range of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in adults and children, respectively, during 28 days of treatment [Citation49]. Both studies reported significant dose-dependent increases in IgE-BF against D. pteronyssinus as well as D. farinae, with doses higher than four SQ-HDM inducing significantly increased levels of IgE-BF after 28 days of treatment. Similarly, levels of specific IgE toward both HDM species showed a significant dose-dependent increase in all active groups, as expected, whereas no changes were observed in the placebo groups [Citation49]. In addition, data from the two studies indicated comparable immunological responses to the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet of an adult vs. pediatric population [Citation49].

A 24-week phase II trial assessing dose-related efficacy of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet using an environmental exposure chamber reported comparable immunological responses [Citation50]. Levels of specific IgE and IgG4 increased significantly in all active groups during the initial 8 weeks of treatment, reaching levels statistically significant from those of the placebo group. Further, at week 24, levels of both immunological parameters demonstrated a pronounced dose-dependence. Importantly, the onset and magnitude of immunological changes correlated with the observed clinical effect of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment on a group level [Citation50].

Collectively, dose-dependence was observed for all assessed immune parameters, regarding onset as well as magnitude of the immunological changes. Thus, responses induced by the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet correspond well with the mechanistic understanding of AIT [Citation22].

2.3. Clinical efficacy

2.3.1. Phase I studies

Dose selection for subsequent efficacy trials was based on the results from two phase I trials investigating tolerability and the acceptable dose range for treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in HDM allergic adults and children, respectively [Citation49]. Testing doses ranging from one SQ-HDM to 32 SQ-HDM, these trials identified 16 SQ-HDM as the maximum tolerable dose. However, as this dose involved a higher frequency of treatment-related adverse events (AEs) compared to the lower doses, 12 SQ-HDM was concluded to represent a suitable dose for further clinical investigation in adults and children with HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease [Citation49]. Thus, no subsequent trials included doses beyond 12 SQ-HDM.

2.3.2. Phase II and phase III studies

The clinical development program for the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was designed to demonstrate clinical benefit in patients with HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease. Clinical efficacy in HDM allergic rhinitis has been demonstrated in several randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials conducted in Europe, as reviewed recently by Klimek et al. [Citation51], and in phase III trials in North America and in Japan.

Clinical efficacy of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in HDM allergic asthma has been evaluated in three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials [Citation50,Citation52,Citation53], as outlined in . The different trial designs involving distinct asthma-specific, clinically relevant primary end points were designed to complement each other and enable independent substantiation of effect. In addition to the listed trials conducted in Europe, the clinical efficacy of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in HDM allergic asthma has been evaluated in one phase III trial in Japan.

Table 1. Summary of efficacy results relating to HDM allergic asthmaa.

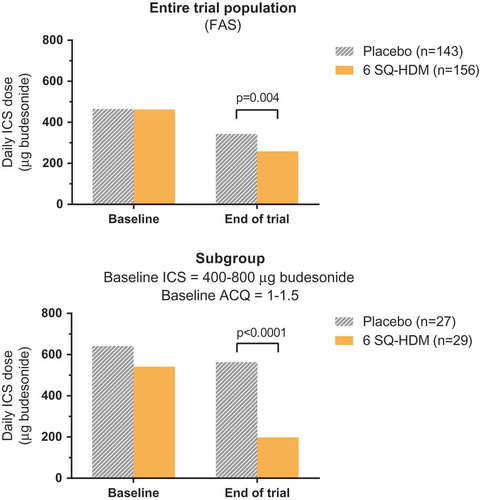

MT-02 (EudraCT no. 2006–001795-20; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00389363) was a large phase II trial investigating the efficacy and safety of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in adults and adolescents with HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease over a treatment period of 1 year [Citation28,Citation52]. The primary end point evaluated impact on the control of allergic asthma as a reduction in daily ICS dose from subjects’ individual baseline dose without deterioration in the asthma disease. The trial population comprised subjects with controlled mild to moderate HDM allergic asthma [defined as an Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score <1.5] as well as a medical history of HDM allergic rhinitis. In order to identify the lowest ICS dose providing asthma control for each subject at baseline and after 1 year of treatment, the trial design involved ICS adjustment periods during the screening period prior to randomization and at the end of the trial, and the ICS dose identified at each time point formed the basis for the primary efficacy assessment. As shown in , compared to placebo, treatment with six SQ-HDM for 1 year resulted in a statistically significantly lower dose of daily ICS required to maintain asthma control. Specifically, at the end of trial assessment, the daily ICS dose necessary to achieve asthma control for patients treated with six SQ-HDM was reduced from baseline by 42% from 462 µg to 258 µg, corresponding to an additional 81 µg reduction compared to the reduction observed for subjects receiving placebo. In contrast, no significant differences from placebo were observed for the two lower doses included in the trial (1 and 3 SQ-HDM) ().

Figure 1. Daily inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) dose at baseline and end-of-trial assessment during the MT-02 trial. The top panel displays data for the entire trial population; the lower panel displays post-hoc analysis results for the subgroup of subjects with a baseline ICS dose of 400–800 µg and partly controlled asthma. Data are displayed as adjusted means.

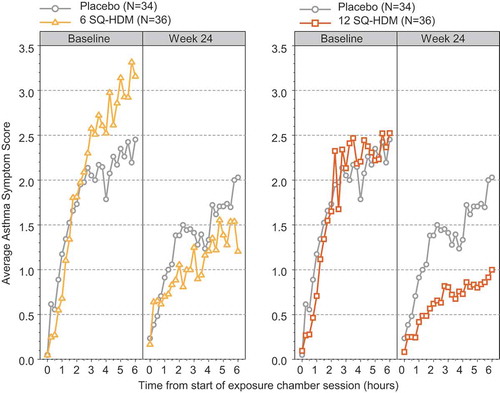

Figure 2. Average asthma symptom score (AASS) during baseline and week 24 exposure challenges in the P003 trial. Data are displayed as adjusted mean of AASS recorded every 15 minutes during the chamber session and include all subjects who recorded symptoms at the week 24 visit.

Additional statistical analyses of the ICS dose supported the observed treatment effect of six SQ-HDM over placebo [Citation52]. Further, a post hoc analysis on a subset of the MT-02 trial population showed that subjects with a daily ICS dose of 400–800 µg and partly controlled asthma (defined as an ACQ score between 1 and 1.5) at randomization experienced a significantly more pronounced treatment benefit in terms of ICS reduction compared to the rest of the trial population with less severe asthma () [Citation54]. Also, after 1 year of treatment with six SQ-HDM, the subgroup population reported statistically significant improvements in asthma related quality of life and improved asthma control, as assessed by the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) and ACQ instruments, compared to placebo. Thus, post hoc analysis of MT-02 trial data suggests that patients with HDM allergic asthma who are not adequately controlled on medium-high daily doses of ICS benefit significantly from SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment in terms of increased asthma control as well as improved quality of life [Citation54].

To investigate dose-related efficacy of SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment, the P003 trial (EudraCT no. 2012–001855-38; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01644617) evaluated the treatment effect in a controlled allergen exposure environment during allergen challenge sessions throughout a treatment period of 24 weeks [Citation50,Citation55]. While the primary end point related to HDM allergic rhinitis, a secondary outcome of the trial was the evaluation of asthma symptoms during allergen challenge sessions, as assessed by the Average Asthma Symptom Score (AASS). The trial population comprised adults with HDM allergic rhinitis with or without asthma and with or without conjunctivitis. HDM allergen challenges were performed as 6-h sessions in an allergen exposure chamber with subjects scoring their symptoms every 15 min. As presented in , after 24 weeks of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, subjects in the 12 SQ-HDM group reported markedly lower AASS during the challenge session than subjects receiving placebo, whereas no difference in AASS was observed between the groups at baseline. This difference corresponds to a statistically significant improvement over placebo in the reported AASS during allergen exposure after 24 weeks of treatment with 12 SQ-HDM (). Likewise, treatment with six SQ-HDM for 24 weeks resulted in a statistically significant improvement vs. placebo in reported AASS during allergen challenge (). After 24 weeks of treatment, a clear dose-response was observed in the reported AASS () and collectively, findings from the P003 trial demonstrate higher efficacy of the 12 SQ-HDM dose as compared with six SQ-HDM.

Figure 3. Probability of having the first moderate or severe asthma exacerbation during the ICS reduction period of the MT-04 trial. Subjects’ daily ICS dose was reduced by 50% for 90 days before complete ICS withdrawal for an additional 90 days. Numbers in the lower part of the plot represent the number of subjects still at risk of exacerbation for each time point. Reproduced with permission from the American Medical Association [Citation53].

![Figure 3. Probability of having the first moderate or severe asthma exacerbation during the ICS reduction period of the MT-04 trial. Subjects’ daily ICS dose was reduced by 50% for 90 days before complete ICS withdrawal for an additional 90 days. Numbers in the lower part of the plot represent the number of subjects still at risk of exacerbation for each time point. Reproduced with permission from the American Medical Association [Citation53].](/cms/asset/a16f8b77-ee10-402f-8fff-4b0e4ea83ed8/ierm_a_1200467_f0003_oc.jpg)

In MT-04 (EudraCT no. 2010–018621–19; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01433523), a phase III trial investigating the efficacy of SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment during natural HDM allergen exposure, impact on the risk of asthma exacerbations was assessed during a 6 month ICS reduction period [Citation53]. The trial population comprised 834 adults with HDM allergic asthma and HDM allergic rhinitis, and with a need for daily ICS treatment equivalent to budesonide 400–1200 µg and an ACQ score of 1–1.5, i.e. not well-controlled on ICS. Subjects were randomized to receive daily treatment with placebo, six SQ-HDM, or 12 SQ-HDM, as add-on therapy to ICS and SABA. The primary end point was time to first moderate or severe asthma exacerbation during a 6 month ICS reduction period. Specifically, after 7–12 months of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet or placebo, daily ICS use was reduced to 50% for 3 months, followed by complete ICS withdrawal for 3 months for the remaining subjects who had not experienced an asthma exacerbation during the previous study phases [Citation53]. As displayed in , the probability of experiencing the first moderate or severe asthma exacerbation increased during the ICS reduction period for all treatment groups, with a clear difference observed between the placebo group and actively treated groups. Specifically, the time to the first exacerbation experienced by 25% of subjects (first quartile) was 102 days for placebo, 166 days for six SQ-HDM, and more than 180 days for 12 SQ-HDM. For both doses, this difference represented a statistically significant risk reduction in the time to first asthma exacerbation versus placebo, as observed by hazard ratios of 0.69 and 0.66 for six SQ-HDM and 12 SQ-HDM, respectively (). Thus, treatment with 12 SQ-HDM resulted in a 34% risk reduction compared to placebo.

In order to assess whether the observed treatment effect was clearly able to reduce HDM-induced morbidity to an extent relevant for patients, a prespecified criterion for clinical relevance was defined as a hazard ratio <0.70 for the imputed data set. Whereas this criterion was met for both doses based on the observed data set (i.e. full analysis set (FAS)) (), only 12 SQ-HDM resulted in a hazard ratio <0.70 based on the imputed data set [Citation53]. Thus, collectively, data from the MT-04 trial indicate that treatment with 12 SQ-HDM provides a clinically relevant and statistically significant reduction in the risk of experiencing an asthma exacerbation versus placebo. This finding suggests that part of the anti-inflammatory action of ICS to promote asthma control can be maintained by treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. Interestingly, the treatment effect was observed irrespective of whether subjects were monosensitized to HDM or sensitized to HDM plus other allergens included in the skin prick test panel [Citation53].

2.3.3. Summary of efficacy trial results

Collectively, data from the presented efficacy trials demonstrate that treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet provides significant clinical improvement in HDM allergic asthma (). Whereas one and three SQ-HDM were below the clinically effective dose range, six and 12 SQ-HDM induced statistically significant treatment effects on current control and future risk, the two domains of overall asthma control [Citation56]. Specifically, SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment results in a reduced need for anti-inflammatory medication, reduced asthma symptom scores, and a reduced risk of experiencing an asthma exacerbation versus placebo upon ICS reduction. Despite similar treatment effects observed with six and 12 SQ-HDM, data indicate a more robust effect for the 12 SQ-HDM dose compared to the six SQ-HDM dose.

2.3.4. Safety and tolerability

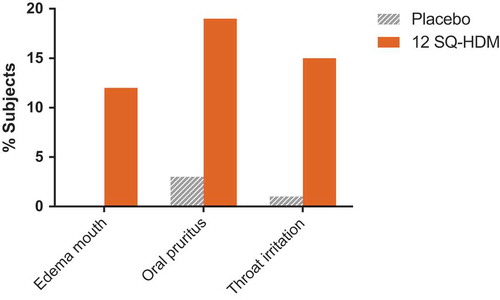

Combined clinical safety data from the reviewed trials indicate that the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was well tolerated, and the observed safety and tolerability profile of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet corresponds well with the observed profile for other SLIT products [Citation30,Citation57–Citation59]. outlines the nature of treatment-related AEs reported by subjects receiving SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment with 12 SQ-HDM or placebo (based on pooled safety data from trials where the 12 SQ-HDM dose was included, i.e. P003 and MT-04). Importantly, safety data from a phase III trial not included in this Drug Profile, in which the primary end point related to HDM allergic rhinitis, support the tolerability profile of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet observed in the reviewed trials [Citation60]. The proportion of subjects experiencing treatment-related AEs was higher among subjects receiving 12 SQ-HDM compared to the placebo group [Citation60]. The majority of AEs observed during the clinical development program of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet were mild, local allergic reactions, most of which occurred within the first few days of SLIT-tablet administration and subsided with continued treatment. As presented in , the most commonly observed treatment-related AEs included oral pruritus, throat irritation, and mouth edema (reported by 19%, 15%, and 12% of subjects receiving 12 SQ-HDM, respectively).

Table 2. Treatment-related AEsa.

Figure 4. Frequency of treatment-related AEs occurring in ≥5% of subjects receiving SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment. Combined safety data from trials where the 12 SQ-HDM dose was included, i.e., P003 and MT-04.

During clinical development of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, a limited number of treatment-related serious adverse events (SAEs) were observed. During the MT-02 trial, a case of severe migraine in a subject receiving 1 SQ-HDM and a case of severe dizziness in a subject receiving three SQ-HDM were classified as SAEs due to hospitalization of the involved subjects [Citation52]. During MT-04, two subjects in the placebo group reported erosive esophagitis and hepatocellular injury, both of which were assessed by the investigator as possibly treatment-related and classified as SAEs (). In the same trial, a subject receiving six SQ-HDM reported moderate laryngeal edema with no airway obstruction or symptoms of dyspnea. This event was considered medically important by the reporting investigator and classified as an SAE [Citation53]. Further, a case of arthralgia in a subject receiving six SQ-HDM in the MT-04 trial was upgraded to an SAE by the investigator after finalization of the trial due to medical importance. In addition, one SAE of moderate asthma was reported with 12 SQ-HDM during MT-04 (). The subject developed worsening of lung symptoms over the first six days of administration of SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment. This event was reported as an asthma exacerbation and assessed as moderate by the investigator, and was classified as an SAE due to hospitalization of the subject. Treatment included inhaled and systemic corticosteroids and LABA, and the subject was discontinued from the trial and recovered fully. According to the investigator, an alternative etiology may have been a recent viral infection [Citation53].

No deaths or cases of anaphylactic shock, and no events reported as systemic allergic reactions were reported in any of the trials. No AEs involved local allergic swelling that compromised the airways. This corresponds well with the known safety profile for SLIT products [Citation61], and the observed tolerability profile represents an advantage over the risk of systemic adverse reactions associated with SCIT.

Collectively, the safety and tolerability profile of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet supports at-home sublingual administration of doses up to 12 SQ-HDM, provided that initial administration is performed under medical supervision.

2.4. Regulatory status

In August 2015, the registration procedure for the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was completed in 11 European countries (Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, and Sweden). The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is indicated in adult patients (18–65 years) diagnosed by clinical history and a positive test of HDM sensitization (skin prick test and/or specific IgE) with at least one of the following conditions:

Persistent moderate to severe HDM-induced allergic rhinitis despite the use of symptom-relieving medication

HDM-induced allergic asthma not well controlled by ICS and associated with mild to severe HDM-induced allergic rhinitis and where patients’ asthma status has been carefully evaluated before the initiation of treatment

In Japan, regulatory authorities approved the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet in September 2015 for hyposensitization therapy for allergic rhinitis induced by mite antigens based on positive results from a large phase III trial conducted in Japan. In the U.S., a similar application was recently submitted to the FDA based positive results from a phase III trial conducted in North America demonstrating the efficacy of SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment (12 SQ-HDM versus placebo) in adults and adolescents with HDM allergic rhinitis (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01700192). Thus, large numbers of HDM allergic patients worldwide will get access to treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet within the near future.

3. Conclusion

The data reviewed in this Drug Profile demonstrate significant clinical improvement in HDM allergic asthma provided by the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. In three distinct trial designs, treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was shown to contribute to a reduced need for ICS, reduced asthma symptoms, or a significantly reduced risk of experiencing a moderate or severe asthma exacerbation upon ICS reduction. Thus, the complementary nature of the trial designs provides independent substantiation of a treatment effect on both current asthma control and future risk. The reviewed safety data indicate a favorable tolerability profile, which constitutes an important advantage over available unmodified extract-based SCIT treatment options. Doses up to 12 SQ-HDM display a safety and tolerability profile that supports at-home sublingual administration once the first tablet is tolerated when administered under medical supervision. In conclusion, treatment with 12 SQ-HDM delivers robust efficacy as well as a favorable safety and tolerability profile, and for patients with HDM allergic asthma, for whom AIT has not previously been recommended, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet represents a novel treatment option.

4. Expert commentary and five-year view

The clinical development program behind the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet represents the largest development program for an AIT product to date and a clear ambition of developing an evidence-based SLIT-tablet with documented clinical benefits for patients suffering from HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease. The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was developed as an improved AIT treatment option, enhancing access to AIT and meeting an unmet medical need of patients with HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease. As such, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is the first AIT to be tested prospectively in patients with asthma, and to favorably modify patient relevant end points such as requirement for ICS or the time to first exacerbation upon ICS reduction, suggesting that SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment may contribute to improving overall asthma control.

For patients suffering from multiple manifestations of HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet may constitute a particularly relevant treatment option. As mentioned, in addition to clinical data reviewed in this Drug Profile demonstrating significant clinical improvement in HDM allergic asthma, treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet has been found to significantly improve disease control in HDM allergic rhinitis, as observed by patients reporting lower symptom scores, decreased allergy pharmacotherapy use, and an improved quality of life [Citation51]. This observed effect on several disease manifestations reflects the advantage of targeting underlying immunological mechanisms of HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease. Thus, for the majority of patients diagnosed with HDM allergic asthma who also suffer from HDM allergic rhinitis, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet represents a treatment option that targets both manifestations and offers a potential for clinical improvement in HDM allergic asthma as well as HDM allergic rhinitis.

While subcutaneously delivered allergen extracts have represented the most common form of AIT for more than a century, the use of SCIT as an add-on treatment option for patients with HDM allergic asthma has been limited by the risk of systemic reactions in asthma patients. Due to this risk of systemic adverse reactions, sublingual administration of allergen extracts has been investigated as an AIT treatment option with an improved safety profile. In the context of AIT for HDM allergic asthma, the data presented in this Drug Profile demonstrate that treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet delivers robust efficacy and a favorable tolerability profile. As this allows for at-home sublingual administration, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet represents a novel and convenient AIT treatment option for patients with HDM allergic asthma who have not previously been able to benefit from AIT.

As clinical experience with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet accumulates, new data are likely to shed light on several as of yet unanswered questions, including the clinical benefit of SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment of pediatric populations, the potential for combination SLIT-tablet therapy for polysensitized patients, and the long-term efficacy beyond SQ HDM SLIT-tablet treatment cessation.

5. Information resources

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) comprises a network of individuals, organizations, and public health officials with the purpose of disseminating information about the care of patients with asthma and translating scientific evidence into improved asthma care worldwide. Thus, the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org) represents a relevant resource providing comprehensive reports and guideline documents, including the annual GINA report ‘Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention’, which includes recommendations for clinical practice and constitutes a useful reference in the management of asthma [Citation14].

The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) initiative aims to educate and implement evidence-based management of allergic rhinitis in conjunction with asthma worldwide and the ARIA website (www.whiar.org) represents a relevant resource. Specifically, the 2008 update of the ARIA Report reviews scientific evidence on the definition and classification of allergic rhinitis, risk factors, mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment [Citation15], and the ARIA 2010 Revision provides additional perspective on treatment options by answering key clinical questions based on objective analysis according to the WHO GRADE methodology [Citation62].

Current knowledge on the mechanisms of AIT, clinical use of AIT in the management of allergic disease worldwide, and unmet needs and ongoing developments in the AIT field have been reviewed in a recent consensus report [Citation22] as part of the PRACTALL initiative, which brings together the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). In addition, the World Allergy Organization (WAO) has published two position papers on SLIT to identify indications, contraindications, and practical aspects of the treatment [Citation25,Citation63].

Further information about the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet and more details on the clinical trials reviewed in the present Drug Profile are available in publications on individual trials: MT-02 (EudraCT no. 2006–001795-20) [Citation52], P003 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01644617) [Citation50], and MT-04 (EudraCT no. 2010–018621-19) [Citation53].

Key issues

Patients with HDM allergic asthma not adequately controlled on available pharmacotherapy present an unmet medical need

AIT targets the underlying mechanisms in HDM-induced respiratory allergic disease by modifying the immunological response to HDM

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet provides robust efficacy in HDM allergic asthma, resulting in reduced controller medication use, reduced asthma symptoms and a reduced risk of asthma exacerbations

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet has a favorable safety and tolerability profile; transient, mild local allergic reactions represent the most commonly occurring adverse reactions

SLIT-tablets represent a highly convenient AIT treatment option

Treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet provides a clinically relevant benefit and constitutes a novel treatment option for patients with HDM allergic asthma

Declaration of interest

GW Canonica has been scientific consultant, researcher in scientific trials, speaker in scientific meetings, seminars and educational activities totally or partially supported by: ALK, Allergopharma, Allergy Therapeutics, Lofarma, Stallergenes, Thermo Fisher, GSK, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Mundipharma, Alimirall, and Chiesi Farmaceutici. JC. Virchow reports receiving grant funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Land Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme; honoraria from Allergopharma, ALK, Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Avontec, Bayer, Bencard, Berlin-Chemie, Bionorica, Boehringer Ingelheim, Essex/Schering-Plough, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Kyorin, Leti, Meda, Merck/Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Altana, Pfizer, Revotar, Sandoz-Hexal, Stallergenes Greer, Takeda, Teva, UCB/Schwarz Pharma, Zydus/Cadila; and serving on advisory boards for ALK, Asche Chiesi, Avontec, Berlin-Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Essex/Schering-Plough, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme/Merck, Mundipharma, Novartis, Revotar, Sandoz-Hexal, UCB/Schwarz-Pharma, and Takeda. P Zieglmayer received lecture fees from ALK, Denmark, Allergopharma, Germany, Bencard, Germany, Novartis, Austria, Stallergenes, Austria, Thermo Fisher Scientific; received grants from Allergopharma, Allergy Therapeutics, Biomay, Calistoga, GSK, HAL, MSD, Ono, Oxagen, RespiVert, Stallergenes, VentirX; and is a Sigmapharm, Stallergenes advisory board member. C Ljørring and IM Smith are employed by ALK, the manufacturer of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. H. Mosbech has no competing interests to declare. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

- Gandhi VD, Davidson C, Asaduzzaman M, et al. House dust mite interactions with airway epithelium: role in allergic airway inflammation. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:262–270.

- Passalacqua G, Ciprandi G, Canonica GW. The nose-lung interaction in allergic rhinitis and asthma: united airways disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1:7–13.

- Passalacqua G, Ciprandi G, Canonica GW. United airways disease: therapeutic aspects. Thorax. 2000;55 Suppl 2:S26–S27.

- Colloff MJ. Dust mites. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009.

- Sunyer J, Jarvis D, Pekkanen J, et al. Geographic variations in the effect of atopy on asthma in the European Community Respiratory Health Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1033–1039.

- Arbes SJ Jr., Gergen PJ, Elliott L, et al. Prevalences of positive skin test responses to 10 common allergens in the US population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:377–383.

- Bousquet PJ, Chinn S, Janson C, et al. Geographical variation in the prevalence of positive skin tests to environmental aeroallergens in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey I. Allergy. 2007;62:301–309.

- Platts-Mills TA, Ward GW Jr., Sporik R, et al. Epidemiology of the relationship between exposure to indoor allergens and asthma. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1991;94:339–345.

- Linneberg A, Henrik Nielsen N, Frølund L, et al. The link between allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma: a prospective population-based study. The Copenhagen Allergy Study. Allergy. 2002;57:1048–1052.

- Holt PG, Rowe J, Kusel M, et al. Toward improved prediction of risk for atopy and asthma among preschoolers: a prospective cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:653–659.

- Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Gurrin LC, et al. House dust mite sensitization in toddlers predicts current wheeze at age 12 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:782–788.

- Lau S, Illi S, Sommerfeld C, et al. Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: a cohort study. Multicentre Allergy Study Group. Lancet. 2000;356:1392–1397.

- Illi S, Von ME, Lau S, et al. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368:763–770.

- GINA Executive Committee. Global Initiative for Asthma; Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health; 2015.

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008;63 Suppl 86:8–160.

- Calderón MA, Linneberg A, Kleine-Tebbe J, et al. Respiratory allergy caused by house dust mites: what do we really know? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:38–48.

- Nurmatov U, Van Schayck CP, Hurwitz B, et al. House dust mite avoidance measures for perennial allergic rhinitis: an updated Cochrane systematic review. Allergy. 2012;67:158–165.

- Terreehorst I, Duivenvoorden HJ, Tempels-Pavlica Z, et al. The effect of encasings on quality of life in adult house dust mite allergic patients with rhinitis, asthma and/or atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2005;60:888–893.

- Custovic A, Wijk RG. The effectiveness of measures to change the indoor environment in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma: ARIA update (in collaboration with GA(2)LEN). Allergy. 2005;60:1112–1115.

- Allam J-P, Novak N. Immunological mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:564–569.

- Eifan AO, Shamji MH, Durham SR. Long-term clinical and immunological effects of allergen immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:586–593.

- Burks AW, Calderon MA, Casale T, et al. Update on allergy immunotherapy: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology/PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1288–1296.

- Scadding G, Durham S. Mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. J Asthma. 2009;46:322–334.

- Calderón MA, Simons FE, Malling H-J, et al. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy: mode of action and its relationship with the safety profile. Allergy. 2012;67:302–311.

- Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, et al. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization position paper 2009. World Allergy Organ J. 2009;2:233–281.

- Dretzke J, Meadows A, Novielli N, et al. Subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and indirect comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1361–1366.

- Alvarez-Cuesta E, Bousquet J, Canonica GW, et al. Standards for practical allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006;61 Suppl 82:1–20.

- Mauro M, Boni E, Makri E, et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic evaluation of house dust mite sublingually administered immunotherapy tablet in the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:1937–1943.

- ALK-Abelló A/S. Acarizax summary of product characteristics. 2015. Available from: http://mri.medagencies.org/download/DE_H_1947_001_FinalSPC.pdf.

- Bergmann K, Demoly P, Worm M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual tablets of house dust mites allergen extracts in adults with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1608–1614.

- Passalacqua G, Pasquali M, Ariano R, et al. Randomized double-blind controlled study with sublingual carbamylated allergoid immunotherapy in mild rhinitis due to mites. Allergy. 2006;61:849–854.

- Passalacqua G, Albano M, Fregonese L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of local allergoid immunotherapy on allergic inflammation in mite-induced rhinoconjunctivitis. Lancet. 1998;351:629–632.

- Henmar H, Frisenette SM, Grosch K, et al. Fractionation of source materials leads to a high reproducibility of the SQ house dust mite SLIT-tablets. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;169:23–32.

- Seager H. Drug-delivery products and the zydis fast-dissolving dosage form. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1998;50:375–382.

- Badgujar BP, Mundada AS. The technologies used for developing orally disintegrating tablets: a review. Acta Pharm. 2011;61:117–139.

- EMEA. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) and Efficacy Working Party (EWP): Guideline on the clinical development of products for specific immunotherapy for the treatment of allergic diseases; EMEA/CHMP/EWP/18504/2006. 2008.

- Bagnasco M, Altrinetti V, Pesce G, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Der p 2 allergen and derived monomeric allergoid in allergic volunteers. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;138:197–202.

- Bagnasco M, Mariani G, Passalacqua G, et al. Absorption and distribution kinetics of the major Parietaria judaica allergen (Par j 1) administered by noninjectable routes in healthy human beings. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:122–129.

- Novak N, Allam J-P. Mucosal dendritic cells in allergy and immunotherapy. Allergy. 2011;66 Suppl 95:22–24.

- Novak N, Bieber T, Allam J-P. Immunological mechanisms of sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 2011;66:733–739.

- Akdis CA, Akdis M. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:18–27.

- Gleich GJ, Zimmermann EM, Henderson LL, et al. Effect of immunotherapy on immunoglobulin E and immunoglobulin G antibodies to ragweed antigens: a six-year prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;70:261–271.

- Bousquet J, Braquemond P, Feinberg J, et al. Specific IgE response before and after rush immunotherapy with a standardized allergen or allergoid in grass pollen allergy. Ann Allergy. 1986;56:456–459.

- Van RR, Van Leeuwen WA, Dieges PH, et al. Measurement of IgE antibodies against purified grass pollen allergens (Lol p 1, 2, 3 and 5) during immunotherapy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:68–74.

- Flicker S, Valenta R. Renaissance of the blocking antibody concept in type I allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2003;132:13–24.

- Wachholz PA, Durham SR. Mechanisms of immunotherapy: IgG revisited. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:313–318.

- Scadding GW, Shamji MH, Jacobson MR, et al. Sublingual grass pollen immunotherapy is associated with increases in sublingual Foxp3-expressing cells and elevated allergen-specific immunoglobulin G4, immunoglobulin A and serum inhibitory activity for immunoglobulin E-facilitated allergen binding to B cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:598–606.

- Shamji MH, Ljørring C, Francis JN, et al. Functional rather than immunoreactive levels of IgG4 correlate closely with clinical response to grass pollen immunotherapy. Allergy. 2012;67:217–226.

- Corzo JL, Carrillo T, Pedemonte C, et al. Tolerability during double-blinded randomised phase I trials with the house dust mite allergy immunotherapy tablet in adults and children. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:154–161.

- Nolte H, Maloney J, Nelson HS, et al. Onset and dose-related efficacy of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablets in an environmental exposure chamber. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1494–1501.

- Klimek L, Mosbech H, Zieglmayer P, et al. SQ house dust mite (HDM) SLIT-tablet provides clinical improvement in HDM-induced allergic rhinitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:369–377.

- Mosbech H, Deckelmann R, De Blay F, et al. Standardized quality (SQ) house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet (ALK) reduces inhaled corticosteroid use while maintaining asthma control: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:568–575.

- Virchow JC, Backer V, Kuna P, et al. Efficacy of a house dust mite sublingual allergen immunotherapy tablet in adults with allergic asthma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1715–1725.

- De Blay F, Kuna P, Prieto L, et al. SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (ALK) in treatment of asthma - post hoc results from a randomised trial. Respir Med. 2014;108:1430–1437.

- Nolte H, Maloney J, Nelson HS, et al. Effect of 12 SQ house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet on asthma symptoms using an environmental exposure chamber. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:A112.

- Bateman ED, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Overall asthma control: the relationship between current control and future risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:600–608.

- Maloney J, Bernstein DI, Nelson H, et al. Efficacy and safety of grass sublingual immunotherapy tablet, MK-7243: a large randomized controlled trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:146–153.

- Nolte H, Amar N, Bernstein DI, et al. Safety and tolerability of a short ragweed sublingual immunotherapy tablet. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:93–100.

- Didier A, Worm M, Horak F, et al. Sustained 3-year efficacy of pre- and coseasonal 5-grass-pollen sublingual immunotherapy tablets in patients with grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:559–566.

- Demoly P, Emminger W, Rehm D, et al. Effective treatment of house dust mite-induced allergic rhinitis with 2 doses of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet: results from a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.036.

- Durham SR, Emminger W, Kapp A, et al. SQ-standardized sublingual grass immunotherapy: confirmation of disease modification 2 years after 3 years of treatment in a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:717–725.

- Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:466–476.

- Canonica GW, Cox L, Pawankar R, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy: world allergy organization position paper 2013 update. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7:6.