Although many immune disorders were difficult to manage in the past, recent advancements in biologic therapies have enabled healthcare providers to control such difficult-to-treat pathologies. However, some patients are concerned that using biologics may result in serious adverse events. How to quantify adverse event rates and present those rates to patients are important issues [Citation1,Citation2].

While clinical studies are well-powered to assess the efficacy of a biologic, they are not well-powered to assess rare events. A study of several hundred subjects may be very well powered to detect differences in efficacy between biologics that result in success 70% or more of the time and placebos that achieve success less than 10% of the time. But such studies may not detect differences in rates of adverse events that may occur in only 1 in 100 or 1 in 1,000. Rare events need more power to be quantified and may not be detected at all in clinical trials. For instance, efalizumab, one of the first biologics approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of psoriasis, was voluntarily withdrawn from the market because of potential risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. No cases were reported during efalizumab’s clinical trials before its FDA approval. Relatively small sample size and short study periods limit the ability to detect rare adverse events. To better define safety profiles, larger samples are needed and can be obtained through registry studies and post-marketing surveillance [Citation3].

The exclusion of subjects with common comorbidities from clinical trials also limits studies’ power to assess adverse events. This limitation negatively impacts external validity and generalizability of a biologic’s safety profile. Registry studies and post-marketing surveillance can help address this, too [Citation4].

Registries and post-marketing surveillance also allow for evaluation of adverse events associated with long-term drug exposure. However, they also have limitations and do not easily allow for comparison of drug safety relative to not taking the drug since there is no randomized control group available for comparison. And even though regulators may encourage recording of all adverse events related to a medication, post-marketing surveillance reportings are far from complete [Citation5].

Having subjects randomized to a placebo group helps determine whether side effects are due to a drug or not. Although clinical trials often have a placebo group, placebo-controlled periods can only be continued for so long before it becomes unethical to leave patients untreated limiting the ability of studies to assess whether drugs cause higher long term side effect rates. As stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, item 33; ‘The benefits, risks, burdens, and effectiveness of a new intervention must be tested against those of the best proven interventions [Citation6].’ Although studies address this unethical dilemma by allowing placebo-controlled trials to eventually continue without a control group, such efforts limit the studies’ ability to provide certainty about long-term safety [Citation1,Citation7]. Registry-based randomized control trials may help provide better information on side effect profiles [Citation8].

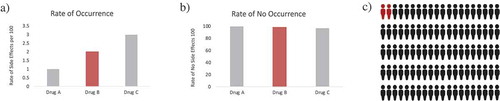

The compilation of clinical trial data, registries, and surveillance do give us a good picture, albeit incomplete, of a drug’s safety (). However, after getting that picture of a drug’s safety, we have to communicate the risk to patients, yet another hurdle to address. Patients’ fear of side effects may be out of proportion to real risk [Citation9–Citation11]. Many strategies have been proposed to address this problem; however, there is no ‘one fits all’ strategy.

Putting risks into perspective may be helpful when advising patients on treatment options. Simply providing statistics may not be ideal, as human brains were not designed for the mathematics of large numbers. Telling patients that an adverse event occurs in only 1 out of 100 patients – or even 1 in 1,000,000 – may leave patients focused on what it would be like to be the 1. Instead, telling patients that an adverse event will not occur in 99 out of 100 patients on a specific treatment can give a much more reassuring perspective [Citation9].

Pictorial aids may be another approach (). These graphical demonstrations help providers counsel patients not only on adverse events but also on improving disease comprehension and treatment adherence. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial of low-literate participants, 73% of participants demonstrated complete understanding of medication labels when provided both text and pictorial aids, compared to 53% when provided only text (P = 0.005) [Citation12]. Moreover, there is an innate preference for pictures rather than text; the ‘picture superiority effect’ may help provide a better understanding about treatment-related adverse events [Citation10].

Figure 1. Changing Patient Perspective Through Pictorial Aids. (a) Drug A, B, and C demonstrate the rate of occurrence of side effects per 100 of 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Drug C looks more worrisome than the rest. (b) Drug A, B and C had a rate of no occurrence of side effects per 100 of 99, 98 and 97, respectively and the difference between them is barely noticeable. (c) Pictorial aids give the perspective on why Graph A and B can be so similar in numbers but so different in context. This is because patients fear being part of the 2% (when being told the rate of side effects) but find more reassuring being part of the 98% (when being told the rate of no side effects)

Behavioral economic strategies can help encourage better adherence; such strategies include using anchoring phrases, message framing, ‘default option,’ or putting adverse effects in the context of more common risks (). How a provider discusses a treatment and its risks influences the patient’s willingness to use that treatment. For instance, message framing strategy speaks about how a message’s effect on a patient is influenced by how the healthcare provider transmits it. While a gain-frame message would be to tell patients that by quitting smoking you will live longer; a loss-framed message would be to tell patients that by not quitting smoking you will die sooner. Framing messages as a loss tends to be a stronger motivator as humans are averse to losses [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14].

Table 2. Strategies for a better patients’ understanding of biologics’ safety

The ethics of such strategies must be considered and are of importance to human subjects research committees and other regulatory bodies. All parties want patients educated in a way that optimizes patients’ autonomy and outcomes. Autonomy and optimizing outcomes may sometimes be in conflict. While it would be inappropriate to try to reassure a patient by saying there are no side effects when there are side effects, framing and other approaches can be used to reduce excessive fears while still disclosing accurate risk information.

Overall, biologics have marked a new era in managing many immunologic disorders; however, evidence regarding their safety is limited. There are several long-term extension studies addressing this need [Citation15,Citation16]. Randomized control trials, registries, and post-marketing surveillances give us a good, yet not perfect, picture of biologic drug safety [Citation7]. However, when comparing the safety of biologics to older drugs (such as systemic corticosteroids and methotrexate), evidence is limited and of even lower quality for older drugs; older drugs did not undergo the strict pharmacovigiliance of more recently approved products, and this can also be considered in discussions with patients about this challenging topic. Putting facts into the appropriate perspective is a critical aspect of risk counseling.

Declaration of interest

SR Feldman has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from a variety of companies including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Valeant, Abbvie, Samsung, Janssen, Lilly, Menlo, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, Caremark, Advance Medical, Sun Pharma, Suncare Research, Informa, UpToDate and National Psoriasis Foundation. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abreu C, Sarmento A, Magro F. Screening, prophylaxis and counselling before the start of biological therapies: a practical approach focused on IBD patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(12):1289–1297.

- Hanley T, Handford M, Lavery D, et al. Assessment and monitoring of biologic drug adverse events in patients with psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:41–54.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):546–551.

- Garcia-Doval I, Carretero G, Vanaclocha F, et al. Risk of serious adverse events associated with biologic and nonbiologic psoriasis systemic therapy: patients ineligible vs eligible for randomized controlled trials. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(4):463–470.

- Alatawi YM, Hansen RA. Empirical estimation of under-reporting in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(7):761–767.

- World Medical Association.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.

- Millum J, Grady C. The ethics of placebo-controlled trials: methodological justifications. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(2):510–514.

- James S, Rao SV, Granger CB. Registry-based randomized clinical trials–a new clinical trial paradigm. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(5):312–316.

- Devine F, Edwards T, Feldman SR. Barriers to treatment: describing them from a different perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:129–133.

- Katz MG, Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Use of pictorial aids in medication instructions: a review of the literature. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(23):2391–2397.

- Keyworth C, Nelson PA, Bundy C, et al. Does message framing affect changes in behavioural intentions in people with psoriasis? A randomized exploratory study examining health risk communication. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23(7):763–778.

- Mansoor LE, Dowse R. Effect of pictograms on readability of patient information materials. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(7–8):1003–1009.

- Abood DA, Black DR, Coster DC. Loss-framed minimal intervention increases mammography use. Womens Health Issues. 2005;15(6):258–264.

- Davis SA, Feldman SR. An illustrated dictionary of behavioral economics for healthcare professionals. 1 ed. Columbia, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2014.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. 2012 Jun 12 - Identifier NCT01617018 Assessing the Long Term Effectiveness and Safety of Biotherapies in the Treatment of Cutaneous Psoriasis (PSOBIOTEQ); 2018 Jul 23. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine. [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT01617018?order=1.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017 Aug 18- Identifier NCT03254667 LTS of Siliq vs. Other Therapies Treating of Adults With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis; 2018 Apr 10. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine. [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT03254667?order=1.