1. Summary

Autoimmune diseases (ADs) are now the fastest growing disease category for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (aHCT). Despite the evolution of competing biological and targeted therapies, there are poor prognosis patients in many ADs who respond unsatisfactorily and for whom the risk: benefit ratio of aHCT is acceptable. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) has been central to developments, with over 3000 HCT registrations for ADs. Recent data has improved the evidence-base to support aHCT in MS, systemic sclerosis and Crohn’s disease, along with a wide range of rarer disease indications. Currently, aHCT is in a phase of ‘implementation science’, where aHCT is now being integrated into algorithms of various ADs. Center quality and collaborative experience are important and aHCT as a single one-off procedure may have health economic advantages versus ongoing administration of biological therapies. Mechanistic studies have provided an evolving insight into ‘re-booting’ of the immune system through a re-diversification of naïve and regulatory immune effector cells and, along with clinical trials, may help fine tune transplant technique and improved patient selection through early prognostic biomarkers with the ultimate goal of safe delivery of aHCT with maximal benefit.

2. Introduction

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) combines various forms of ablative cytotoxic therapy with a subsequent infusion of allogeneic (donor) or autologous (self) hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) to reconstitute the blood and immune systems and is used to treat a wide range of malignant and non-malignant indications [Citation1].

Over the last 20 years, HCT has been increasingly used in the treatment of patients severely affected by autoimmune diseases (ADs) [Citation2–Citation5]. By far the majority of the procedures are for the autologous HCT, which can be delivered with low risks compared with allogeneic HCT. ADs are now the fastest growing indication category for aHCT [Citation6].

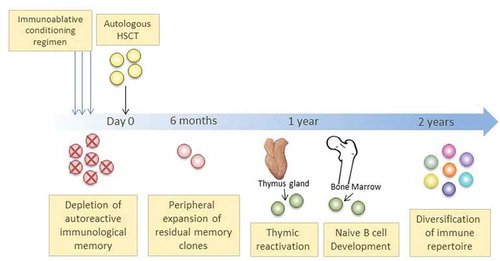

Autologous HCT is an intensive ‘one off’ procedure, typically combining high-dose cytotoxic chemotherapy with lymphodepleting serotherapy (most commonly anti-thymocyte globulin, ATG) followed by HSC infusion with the aim of broad immunoablation, providing an initial rapid ‘debulking’ of the inflammatory load followed by regeneration of the hematopoietic and immune systems. Such ‘re-booting’ is clinically associated with sustained responses in some ADs, leading to freedom from and/or renewed sensitivity to immunosuppressive drugs, even in patients that have become refractory to modern biological management [Citation3–Citation5]. The process is summarized in . Type and intensity of conditioning regimen in ADs may vary according to indication, study protocol or center preference. The most widely used regimen is non-myeloablative (most commonly cyclophosphamide/ATG-based), which aims to be ‘lymphoablative’ but does not have the intensity to destroy the entire hematopoietic compartment, which may be achieved by higher intensity ‘myeloablative’ regimens.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the process of autologous HCT and post-transplant immune re-constitution in autoimmune diseases

Initial concepts of using HCT as a means of controlling severe ADs were based on animal experiments and clinically validated though the observation of serendipitous case reports, where patients treated for ‘standard indications’ had cure or long remission of ‘coincidental’ AD alongside their leukemia or aplastic anemia [Citation3,Citation4]. From the mid-1990s patients were treated with aHCT specifically for various severe ADs. This was followed by the formation within the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) of the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP), which was closely aligned to the EBMT registry. The EBMT registry has now collected over 3000 patients treated with HCT, predominantly aHCT for multiple sclerosis (MS), systemic sclerosis (SSc), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Crohn’s disease (CD) and a range of other diseases. Individual AD indications for aHCT are summarized in . The ADWP has been instrumental in reporting both retrospective and prospective clinical studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), whilst publishing guidelines and recommendations for responsible practice and promoting education across the specialties [Citation2,Citation7–Citation9].

Table 1. Autologous HCT for autoimmune diseases reported to the EBMT registry (May 2019, N = 2809)

Progress has been slower than expected. It has taken almost two decades for aHCT to be recognized as a standard treatment option alongside the continual development of biologic and other targeted therapies. Such treatment advances, usually involving the design of monoclonal antibodies and small molecules specifically targeted against key elements of autoimmune and inflammatory pathways, have been without doubt significant advances in the management of ADs. They have been supported heavily by the pharmaceutical industry and can be administered by the AD specialists, which favored their adoption by disease-specific communities. However, they require continuous administration and do not provide control in all patients.

In contrast, aHCT requires complex multi-specialty collaboration (involving close working between disease specialists and transplant hematologists) and has a higher level of early toxicity, which mandates inpatient management. In the earlier phases of development of aHCT tolerance of side effects was compromised by the established and often irreversible organ dysfunction and disability commonly seen in advanced, poor prognosis patients with various ADs. Early experiences of aHCT as ‘last ditch’ salvage treatments were not encouraging for widespread adoption. With time, limitations in modern biological therapies have been recognized and aHCT has become safer and experience of cross-specialty working has become greater. The combination of earlier referral, better patient section, and increased center experience has most likely contributed to substantial falls in treatment-related mortality (TRM) [Citation2]. Significantly, for example, a TRM of 2.8% was reported in a large retrospective multicenter study in MS patients receiving aHCT between 1995 and 2006 [Citation10], but there has been no TRM in the recent larger studies in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), with levels of 0.2–0.3% based on EBMT registry data and meta-analysis of published studies [Citation11–Citation14].

In time, various disease specialist communities and their patients have become more interested in the ‘cross fertilization’ approach of aHCT. This has been consolidated by the progressive publication of higher quality evidence supporting the use of aHCT use in well-selected patients with RRMS, SSc, and CD, and also the integration of aHCT into professional guidelines and algorithms.

3. Indications for autologous HSCT in AD

3.1. Multiple sclerosis and neurological diseases

MS patients have been treated with aHCT since 1995. However, it eventually became clear that only patients with active neuroinflammation, mainly in the RRMS phase of the disease, could benefit [Citation10–Citation14]. There have been two RCTs: a phase II, predominantly in secondary progressive (SPMS) patients, demonstrating a relative reduction in inflammatory activity and relapse, but limited in its design to sufficiently demonstrate an impact on disability [Citation11], and a recent phase III trial providing convincing evidence of a substantial effect on relapse and disability compared with most modern disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) [Citation13]. In this multicentre trial, disease progression (Expanded Disease Status Scale, EDSS, score increase of ≥1.0) was observed in 3 patients in the HCT group versus 34 patients in the DMT group with a median follow-up of 2 years. In addition, the mean EDSS score improved from a pre-HCT score of 3.38 to 2.36, whereas it worsened in the DMT group from 3.31 to 3.98 at 1 year. There were no deaths in the HCT group or in the DMT group [Citation14].

Outside of clinical trials, current consensus supports the use of aHCT in highly active RRMS, ‘aggressive’ MS and cautiously with progressive MS with clear evidence of significant clinical and MRI disease activity [Citation1]. Other neurological indications include chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and myasthenia gravis (MG), and are covered in recent reviews [Citation3,Citation4].

3.2. Rheumatic diseases

Rapidly progressive diffuse cutaneous SSc has five-year mortality up to 30% due to progressive fibrosis, inflammatory damage, vasculopathy and organ failure, particularly due to pulmonary arterial hypertension or interstitial lung disease. Even in the biological era, effective drug therapy is not available, with only a modest effect of cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil and much has been dependent on supportive care. On this background, three RCTs in SSc have compared aHCT to intravenous cyclophosphamide [Citation15–Citation17]. All trials supported significant improvement in skin and broader disease-specific scores, with some evidence for benefits on pulmonary function. The 5-year event-free survival was reported between 70% and 74% in the large multicentre European (ASTIS) and American (SCOT) trials and remained superior to monthly cyclophosphamide in the control arm during the 10 years following HSCT in the ASTIS trial [Citation16,Citation17]. Toxicity of aHCT in SSc was initially relatively high, predominantly attributed to SSc-related cardiac dysfunction, and especially related to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and drug-induced cardiotoxicity. With improved screening procedures and transplant techniques [Citation18], as well as cyclophosphamide-sparing conditioning regimens, early TRM decreased from 10% in the ASTIS trial [Citation15], to 5% since 2010 within the EBMT registry [Citation2] and 3% in the SCOT trial [Citation17]. Autologous HCT is now an intrinsic part of the SSc treatment pathway [Citation19] and endorsed by recently updated recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [Citation20].

Other severe autoimmune connective tissue diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermato- and polymyositis and systemic vasculitis have been treated to varying results. The number of these patients is unlikely to be great enough to complete RCTs, but consideration is possible on an individualized basis [Citation2–Citation4].

3.3. Crohn’s disease

Treatment options are limited in CD patients with refractory disease and surgery may not be feasible or be unacceptable. Long-term outcomes after aHCT for resistant CD have been recently reported by the ADWP with a stabilization of the disease in the majority of this very heavily pre-treated cohort. Although relapse occurs more commonly in CD than MS and SSc, the reintroduction of anti-TNF therapy may result in ongoing stabilization of disease [Citation21].

There has been one RCT in CD, the EBMT-based ‘ASTIC’ trial, which failed to meet its primary endpoint for a variety of factors related to trial design and crossover [Citation22]. However, in a subsequent analysis of the combined cohort of the 40 patients that underwent aHCT (including crossovers), there was a significant improvement in clinical disease activity, quality of life and endoscopic disease activity, with half of the patients having complete responses [Citation23]. The current ‘ASTIC-lite’ RCT, which incorporates associated mechanistic studies and an EBMT based long term follow up study will evaluate the effect of aHCT delivered using a modified regimen versus standard of care in poor-prognosis treatment-resistant CD [Citation24]. There is also an ongoing high-level inter-specialty collaboration between EBMT and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) [Citation25].

3.4. Other autoimmune diseases

A variety of other ADs treated with aHCT have been reported to the EBMT registry, which has been especially useful in identifying outcomes in rare ADs where there is limited opportunity for prospective studies. These are featured in and specific studies and other reports are covered in recent reviews [Citation2–Citation4].

4. The future

The role of aHCT in the treatment of ADs has been a changing dynamic and will continue to be so. However, it is now likely to continue to establish its place in the various treatment algorithms alongside other modern therapies for specific ADs. This will depend on improving the evidence of risk: benefit through better patient selection and improved transplant technique, whilst developing cross-specialty working and consideration of the broader health economic aspects of the delivery of aHCT through our health services. The following aspects are key:

4.1. Basic science

Basic science will be key to informing clinical practice; firstly by examining the mechanistic aspects there will be the basis for more directed therapies in designing the transplant techniques; and secondly, the general recognition of early biomarkers, whether clinical, radiological or biochemical, to define high-risk patients at an early stage. Developments in ‘pre-clinical’ autoimmunity will be of direct relevance to aHCT in ADs [Citation26].

4.2. Clinical trials

Clinical trials are needed, not only to provide proof of principle that aHCT procedure can provide significant therapeutic benefits over the standard of care but also to address early phase aspects of transplant technique, including more targeted conditioning regimens and graft selection. It is important to emphasize that aHCT and biological treatments are not mutually exclusive; they may have their place in the transplant regimen, maintenance and/or early salvage.

4.3. Data reporting

The newly redeveloped EBMT registry (MACRO) will incorporate the highest number of HCT in AD and will continue to support retrospective and prospective studies, along with other scientific interactions, both inside and outside the EBMT.

4.4. ‘Implementation science’

In addition to gaining acceptance across many disease-specific communities, the broader roll out of aHCT needs the ‘buy in’ of the public health services and other payers and for ‘low volume high cost’ procedures there is inevitably scrutiny in terms of health economics and quality of outcomes in individual units. Health economic benefits from aHCT as a single ‘one-off’ procedure may be favorable over the costs of years of ongoing biological treatment. The EBMT provides a quality assurance and accreditation scheme and evidence indicates that JACIE accreditation may impact, along with center experience, upon outcomes of AD post-aHCT [Citation2]. It is always a controversial question as to whether ‘centers of excellence’ are required, but there is, at the very least, a clear need for close interspeciality working to optimize early patient referral, patient selection, clinical management and follow up and a professional responsibility to inform patients and promote quality and good clinical practice in the field of HCT [Citation1].

5. Conclusions

With close working between transplant hematologists and disease specialists, aHCT will continue to evolve. Autologous HCT now has to be recognized as a standard treatment option alongside the continual development of biologic and other targeted therapies. However, as the field develops, these treatment advances, specifically targeted against key elements of autoimmune and inflammatory pathways, may become integral elements of the autologous HCT procedure. Along with other international partners and collaborators, the EBMT ADWP has an important overarching role in bringing together various specialists to support good clinical practice, educational activity, and clinical studies via the EBMT registry.

Declaration of interest

JA Snowden discloses honoraria from Sanofi, Jazz, Janssen, Actelion and Kiadis Pharma, as well as grant support from UK NIHR. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge EBMT centers for their contributions to the EBMT registry and those active in the ADWP.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Duarte RF, Labopin M, Bader P, et al. for the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Indications for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current practice in Europe, 2019. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019 Apr 5. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI:10.1038/s41409-019-0516-2.

- Snowden JA, Badoglio M, Labopin M, et al. Evolution, trends, outcomes, and economics of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe autoimmune diseases. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2742–2755.

- Alexander T, Farge D, Badoglio M, et al. Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Hematopoietic stem cell therapy for autoimmune diseases - clinical experience and mechanisms. J Autoimmun. 2018;92:35–46.

- Kelsey PJ, Oliveira MC, Badoglio M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in autoimmune diseases: From basic science to clinical practice. Curr Res Transl Med. 2016;64:71–82.

- Snowden JA. Re-booting autoimmunity with autologous HSCT. Blood. 2016;127(1):8–10.

- Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, et al. Is the use of unrelated donor transplantation leveling off in Europe? The 2016 European society for blood and marrow transplant activity survey report. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018 Sep;53(9):1139–1148.

- Tyndall A, Gratwohl A. Blood and marrow stem cell transplants in auto-immune disease: a consensus report written on behalf of the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997 Apr;19(7):643–645.

- Snowden JA, Saccardi R, Allez M, et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European group for blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:770–790.

- Alexander T, Bondanza A, Muraro PA, et al. SCT for severe autoimmune diseases: consensus guidelines of the European society for blood and marrow transplantation for immune monitoring and biobanking. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:173–180.

- Muraro PA, Pasquini M, Atkins HL, et al. Long-term outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(4):459–469.

- Mancardi GL, Sormani MP, Gualandi F, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a phase II trial. Neurology. 2015;84(10):981–988.

- Das J, Sharrack B, Snowden JA. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a review of current literature and future directions for transplant haematologists and oncologists. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019;14(2):127–135.

- Burt RK, Balabanov R, Burman J, et al. Effect of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation vs continued disease-modifying therapy on disease progression in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(2):165–174.

- Muraro P, Martin R, Mancardi G, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(7):391–405.

- Burt RK, Shah SJ, Dill K, et al. Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation compared with pulse cyclophosphamide once per month for systemic sclerosis (ASSIST): an open-label, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:498–506.

- van Laar JM, Farge D, Sont JK, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation vs intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2490–2498.

- Sullivan KM, Goldmuntz EA, Keyes-Elstein L, et al. Myeloablative autologous stem-cell transplantation for severe scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:35–47.

- Farge D, Burt RK, Oliveira MC, et al. Cardiopulmonary assessment of patients with systemic sclerosis for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: recommendations from the European society for blood and marrow transplantation autoimmune diseases working party and collaborating partners. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(11):1495–1503.

- Smith V, Scirè CA, Talarico R, et al. Systemic sclerosis: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2018 Oct 18;4(Suppl 1):e000782. eCollection 2018.

- Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1327–1339.

- Brierley CK, Castilla-Llorente C, Labopin M, et al. European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP). autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Crohn’s disease: a retrospective survey of long-term outcomes from the European society for blood and marrow transplantation. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 May 18. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy069.

- Hawkey CJ, Allez M, Clark MM, et al. Autologous hematopoetic stem cell transplantation for refractory Crohn disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2524–2534.

- Lindsay JO, Allez M, Clark M, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease: an analysis of pooled data from the ASTIC trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:399–406.

- Pockley G, Lindsay JO, Foulds GA, et al. on behalf of the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) and the ASTIClite study investigators. immune reconstitution after autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Crohn’s disease: Current status and future directions. A review on behalf of the EBMT autoimmune diseases working party and the ASTIClite study investigators. Front Immunol. 2018;9:646.

- Snowden JA, Panes J, Alexander T, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) in severe Crohn’s disease: a review on behalf of ECCO and EBMT. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(4):476–488.

- Rose NR. Prediction and prevention of autoimmune disease in the 21st century: a review and preview. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:403–406.

- Jessop H, Farge D, Saccardi R, et al. General information for patients and carers considering haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for severe autoimmune diseases (ADs): a position statement from the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP), the EBMT nurses group, the EBMT patient, family and donor committee and the joint accreditation committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019 Jan 31. DOI:10.1038/s41409-019-0430-7.