ABSTRACT

Introduction: Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is characterized by widespread erythema and edema, superficial sterile coalescing pustules, and lakes of pus. Although the impact of GPP is thought to be substantial, emerging literature on its clinical, humanistic, and economic burden has not previously been described in a structured way.

Areas covered: A structured search focused on the identification of studies in GPP using specific search terms in PubMed and EMBASE® from 2005 onwards, with additional back-referencing and pragmatic searches. Outcomes of interest included clinical, humanistic, and economic burden.

Expert opinion: Despite its significant clinical, humanistic, and economic burden, GPP is poorly classified and inadequately studied. A recent European (ERASPEN) consensus classifies GPP into relapsing and persistent disease and classifies patients on the presence or absence of psoriasis vulgaris. Classification of GPP lesions involving >30% body surface area or use of hospitalization as a surrogate may be a way to identify significant flares. Given the frequency of flares, the impaired quality of life during the post-flare period, and safety/tolerability issues, it is clear that current treatment options are not sufficient. Long-term studies utilizing the European consensus statement with subclassifiers are required to supplement our current understanding of the burden of GPP.

1. Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), first described by von Zumbusch in 1910, is characterized by widespread erythema and edema, superficial sterile coalescing pustules, and lakes of pus. Dermal eruptions are usually accompanied by fever and leukocytosis. GPP is one recognized subtype of pustular psoriasis (PP), alongside palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH). PP describes a group of inflammatory skin conditions characterized by infiltration of neutrophil granulocytes in the epidermis to such an extent that clinically visible sterile pustules develop [Citation1]. PP has traditionally been considered a subset of psoriasis alongside other phenotypes including psoriasis vulgaris (PV; also known as plaque psoriasis), intertriginous psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, and erythrodermic psoriasis [Citation2]. However, the classification of PP (and [PPP] in particular) within psoriasis has often been debated [Citation3]. A recent collaboration from the European Rare and Severe Expert Network (ERASPEN) has classified PP as a distinct clinical entity rather than a subset of psoriasis, noting clear distinctions in the genetic architecture of PP and PV, as well as differences in response to treatment. Primary pustules are not considered to feature on the PV spectrum, and conditions in which pustules arise within or at the edge of psoriasis plaques are described as ‘psoriasis cum pustulatione’ (psoriasis with pustules) and are not classified as PP [Citation1]. It is also important to distinguish GPP from other pustular dermatoses, including subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson syndrome; a localized variant of pustular psoriasis) and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) [Citation4]. AGEP is a drug-induced pustular psoriasis, which, like GPP, presents with rapid onset of generalized pustules. However, the two conditions can be differentiated on the basis of their clinical features, especially the quicker resolution of symptoms with AGEP [Citation5]. The classifications of GPP, PPP, and ACH have been used historically and are retained in the recent ERASPEN consensus document. Consensus definitions for the diagnosis of these three subtypes are provided in [Citation1].

Table 1. ERASPEN consensus definitions for the diagnosis of pustular psoriasis.

In GPP, loss-of-function mutations of IL36RN were identified in 23% to 37% of familial and sporadic cases, which seem to be associated with a more severe clinical phenotype. These and other gene mutations found in patients with GPP (including mutations in CARD14 and AP1S3) lead to enhanced proinflammatory cytokine secretion and recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the skin, and thus are directly contributing to the pathology of the disease [Citation4].

Recently, Akiyama et al. [Citation6] highlighted the role of IL36RN and CARD14 mutations in GPP and proposed that GPP cases with autoinflammatory pathomechanisms be classified within ‘autoinflammatory keratinization disease’ (AiKD). This is particularly the case with early-onset GPP without preceding plaque psoriasis, which is often associated with IL36RN mutations [Citation7]. Ethnic differences have been reported in genetic mutations associated with GPP; in a large recent study, IL36RN mutations were most frequent in European patients (34.7%) with GPP, followed by East Asian patients, most of whom were from Malaysia (28.8%). None of the South Asian patients in the study had IL36RN mutations [Citation8]. In Chinese Han patients, IL36RN mutations have been reported in 46.8–60.5% of GPP patients; the frequency of mutations was much higher in GPP patients without psoriasis (70.6–79.2%) than in those with psoriasis (36.8–37.8%) [Citation9,Citation10]. A high frequency of IL36RN mutations in GPP patients without psoriasis has also been reported in Japan (81.8%) [Citation11] and Germany (46.2%) [Citation12].

First-line systemic treatment for GPP in adults includes oral retinoids (acitretin), cyclosporine, methotrexate, or a rapidly acting biologic agent. Second-line treatment may involve combining a biologic agent with conventional therapy. Topical treatments such as corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus also have a role in GPP, either as a standalone treatment for mild or localized illness, or as an adjunct to systemic therapy in more severe/generalized illness. Treatment for children with GPP is broadly along similar lines and includes acitretin (with or without oral prednisolone), methotrexate, and cyclosporine. The treatments for GPP can themselves be burdensome; important safety concerns with the current treatments include teratogenicity risk (acitretin and methotrexate) and osteoarticular symptoms (acitretin), while biologic agents can cause bone marrow depression resulting in an increased risk of serious infections. Steroid treatment carries the risk of triggering a GPP flare due to steroid withdrawal [Citation4]. While genetic differences across ethnicities have been reported [Citation8], data are lacking on potential differences in treatment responses across ethnic groups [Citation4].

Although the burden of GPP is typically described in terms of clinical consequences, the impact on the lives of patients and their families and economic cost is thought to be substantial, and we have not identified any previous review that has attempted to describe the emerging literature on clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of GPP in a structured way. The objective of the current review was, therefore, to characterize the overall disease burden of GPP across the following domains: (1) Clinical burden (epidemiology, core clinical features, and natural history of disease over time, including risk factors, clinical outcomes, and comorbidities); (2) Humanistic burden (functioning, quality of life [QoL], psychosocial burden, adherence/preference/satisfaction with treatment and caregiver burden); and (3) Economic burden (drivers of resource use and cost, actual costs, and utilities). In the sister publication published in the same edition [Citation13], the burden of disease of PPP is characterized in a similar way.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search strategy

Based on the review objectives, a structured search focused on the identification of observational studies in GPP using specific search terms (‘pustular psoriasis’ OR ‘generalized pustular psoriasis’ OR ‘generalised pustular psoriasis’). Searches were performed using the PubMed and EMBASE® databases from 2005 onwards (2005–2018). In addition, supplementary searches were conducted through back-referencing of relevant articles, pragmatic searches in PubMed, Google Scholar, the gray literature, and conference abstracts.

2.2. Study selection

Screening and extraction were conducted by a single reviewer. Titles and abstracts of the citations identified in the literature search were screened according to predefined criteria, which included patient population (individuals diagnosed with GPP), outcome measures of interest (clinical burden, humanistic burden, economic burden), and study design (case reports and case series were excluded).

Potentially relevant articles that met the eligibility criteria were selected for full-text review, and the criteria were then applied to the full-text articles. To avoid duplication of information and in order to provide a useful overall summary, articles were further screened to ensure that 1) the highest quality publications were selected and 2) the publications provided adequate representation of the population, including pediatric studies.

3. Results

In total, 19 unique publications are included in this review, of which 13 report on clinical outcomes only, two on economic outcomes only, one on QoL only, two on clinical and economic outcomes, and one which reports on all outcomes of interest.

3.1. Clinical burden of GPP

This section describes the clinical burden experienced by patients with GPP as well as the natural history of GPP, including the evolution of signs and symptoms. The publications providing data to support the findings described in this section are summarized in .

3.1.1. Epidemiology

One national study [Citation14] focused on the prevalence of GPP, and three studies provided supporting data [Citation15–Citation17] ().

Table 2. Characteristics of publications reporting on the clinical burden of GPP.

Augey et al. conducted a national GPP-focused study in France and reported a prevalence rate of 1.76 cases per million population [Citation14]. In this study, GPP data from hospitals were obtained by sending a questionnaire to dermatological wards throughout France for information on all in- and outpatients who visited these departments during 2004. Of the 121 dermatological wards, 112 responded to the questionnaire; 46 of these wards reported a total of 99 GPP patients. Ohkawara et al. assessed the prevalence of ‘GPP and related disorders’ by sending questionnaires to 575 community center hospitals throughout Japan to obtain information from medical records for patients with GPP and related disorders who had visited the hospitals during 1983–89; and reported a prevalence of 7.46 cases per million population [Citation17]. Much higher prevalence rates were described in a national insurance database study in Korea (122.3 per million population [psoriasis prevalence: 453 per 100,000; GPP: 2.7% of all psoriasis]) [Citation16] and a prospective observational study across 104 centers in Italy (180.0 per million population [psoriasis prevalence: 2%; GPP: 0.9% of all psoriasis]) [Citation15], with both studies reporting GPP prevalence as a subset of overall psoriasis ().

Figure 1. Prevalence of GPP (per million population) across studies.

*Ohkawara 1996 reported the prevalence of ‘GPP and related disorders’ [Citation17].

![Figure 1. Prevalence of GPP (per million population) across studies.*Ohkawara 1996 reported the prevalence of ‘GPP and related disorders’ [Citation17].](/cms/asset/81f136bc-31ed-47ed-93e2-107b21c29d3e/ierm_a_1708193_f0001_oc.jpg)

Augey et al. also reported the incidence of GPP using two approaches [Citation14]. The first approach used survey data as described above, which yielded an incidence rate of 0.64 cases per million person-years. The second approach utilized claims data from the national health insurance of France (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés) and reported an incidence rate of 0.5 cases per million person-years in 1998 and 0.8 case per million person-years in 2001.

Zelickson classified GPP patients into four subtypes (acute, subacute annular, chronic acral, and mixed GPP) based on the onset of flare and lesion morphology [Citation18]. However, the recent ERASPEN consensus statement defines subtypes of GPP on the basis of the presence or absence of associated features, as shown in [Citation1]. Although conventions for the subclassification of GPP were not applied consistently across studies, acute GPP was the most commonly reported subgroup. A high proportion of acute GPP (93%) was reported by Choon (n = 102) [Citation19], while in the 1991 study by Zelickson, 56% of patients (n = 63) had a diagnosis of acute GPP [Citation18].

GPP is known to occur at all stages in life, including in children (juvenile GPP) [Citation20–Citation22]. Data from Malaysia reported a mean age of disease onset of 40.9 years among patients with adult-onset GPP (range: 21–81 years) [Citation19], with other studies reporting a mean age at diagnosis of 45.6 (across all age groups) [Citation20] to 50 years (adult-onset GPP) [Citation18]. In the French epidemiological study, the incidence and prevalence of GPP were highest between the ages of 40 and 60 years [Citation14], which is consistent with an earlier retrospective study from the UK which reported the highest GPP prevalence between the fifth and sixth decades of life [Citation23].

Most publications reported GPP to be more frequent in females than males, with the male-to-female ratio varying from 0.5 to 0.9 [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19,Citation23].

3.1.2. Clinical characteristics and diagnosis

While the definitions and classifications of GPP used across studies were inconsistent, the occurrence of flares presenting throughout the course of the disease is the defining and diagnostic characteristic of the condition. In general, a GPP flare consists of a generalized pustular eruption all over the body. In most cases, the onset of the flare is acute and GPP is then diagnosed based on the presence of systemic symptoms along with multiple sterile pustules (‘acute GPP’ or ‘von Zumbusch’), although subacute and chronic onset may also be possible. Navarini et al. recently proposed that GPP should only be diagnosed when the condition (consisting of primary, sterile, macroscopically visible pustules on non-acral skin) has relapsed at least once or when it persists for more than 3 months [Citation1].

Flares are a potentially life-threatening and critical characteristic of GPP, consisting of dermal lesions accompanied by systemic symptoms. Widespread erythematous plaques studded with sterile pustules all over the body are typically seen, which often coalesce to form lakes of sterile pus [Citation22]. Common symptoms during GPP flares include fever with chills and rigors as well as arthralgia. In one retrospective chart review, fever, and painful skin lesions were present in 89% of patients (n = 102) [Citation19].

Other clinical features in acute GPP flares included uveitis, conjunctivitis, iritis, leg swelling, geographic or fissured tongue, and cheilitis [Citation18,Citation19,Citation22]. On rare occasions, the acute stage may be followed by pulmonary capillary leakage, pulmonary emphysema, jaundice, or renal failure [Citation22].

During the post-flare chronic phase, patients experienced a variety of skin lesions including acropustulosis, annular plaque psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, plaque, erythroderma, and PP [Citation17,Citation19]. Of these, plaque psoriasis lesions were the most common manifestation (50%), followed by pustular lesions (22%).

3.1.3. Disease course

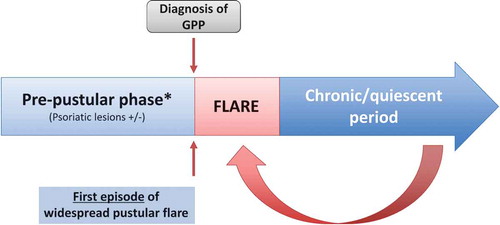

GPP can broadly be described as having three phases. An initial pre-pustular phase is followed by a flare and then a post-flare chronic/quiescent period, which persists until the next flare. A repeating pattern of flares and post-flare periods may continue to occur episodically throughout life ().

3.2. Pre-pustular phase

In patients with preceding psoriasis (usually in the form of plaque lesions), the pre-pustular phase persisted for approximately 6–12 years prior to the first widespread flare [Citation17–Citation19,Citation24]. During this phase, 31–78% of GPP patients experienced psoriatic lesions [Citation17–Citation19,Citation24].

3.3. Acute symptoms/flares

Data on the frequency of flares over time were limited. One single-center study, in which a flare was defined as involving greater than 30% body surface area (BSA), reported a single flare in approximately 60% of patients (n = 102) over a follow-up period of around 5 years [Citation19]. In the same study, approximately 40% of patients reported a recurrence of flares, with about 10% experiencing more than five flares over a 5-year period [Citation19].

3.4. Post-flare chronic/quiescent period

Following the treatment of a flare, most patients showed partial or complete response. As an example, Wu et al. reported that 42% of adult patients (n = 66) and 25% of children (n = 16) demonstrated complete resolution of pustules, erythema, and scales, while 36% and 50% of adults and children, respectively, showed a marked response [Citation25]. Only 9% of adults and 6% of children showed no response immediately following treatment.

However, relapse of lesions (not amounting to a widespread flare) is common. In a report of patients with GPP across two tertiary hospitals, relapse of skin lesions was subsequently seen after initial symptom clearance (following treatment) in 76% of patients (n = 25) over a 1-year follow-up [Citation24]. These relapses were reported to manifest in the form of pustules alone (42%), plaques alone (32%), or both plaques and pustules (26%). Patients with preceding plaque psoriasis may have an increased risk of relapse [Citation24]. These findings were corroborated by cross-sectional data from Choon et al. who found that, during the non-flare period, only a small proportion (<5%) of patients showed no psoriasis symptoms [Citation19]. In this study, during the non-flare period, almost all patients were receiving topical or systemic treatments, with most patients (nearly 73%) experiencing mild psoriasis (affecting <10% BSA) and about 10% of patients experiencing moderate-to-severe psoriasis (affecting ≥10% BSA). As discussed earlier, these psoriasis symptoms consisted of plaque psoriasis in about 50% of the patients, followed by PP lesions in about 22% [Citation19].

3.4.1. Precipitating factors for flares

GPP flares tend to be triggered by specific factors. In the retrospective analysis by Choon, precipitating factors were identified in 85% patients (n = 102), with a spontaneous first episode of GPP flare occurring in 15% patients [Citation19]. Slightly lower rates were reported by Zelickson et al. and Wu et al., with 46% and 50%, respectively, of flares being associated with specific triggers [Citation18,Citation25].

The most commonly reported precipitating factors for flares were withdrawal of steroid treatment (approximately 30–40% of patients) [Citation19,Citation23]; pregnancy (two or more flares in 60% of pregnant women with GPP versus 40% in GPP as a whole) [Citation19]; infections (particularly upper respiratory tract infections) [Citation17–Citation19,Citation21,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26]; hypocalcemia [Citation23]; and others, including sun exposure, seasonal variation, salicylates, exertion, and menstruation [Citation18].

Specific precipitating factors appeared to be associated with the type of GPP. Medications (75%) [Citation25], including steroids (15–28%) [Citation17], triggered flares more frequently in patients with preceding plaque psoriasis, whereas in patients with no preceding plaque psoriasis, the most common precipitating factors included pregnancy (35%) [Citation19] and respiratory tract infections (42%) [Citation25].

3.4.2. Key comorbidities

Common comorbidities in GPP included obesity (42.9%), hypertension (25.7%), hyperlipidemia (25.7%), and diabetes mellitus (23.7%) [Citation19]. Other conditions seen with GPP included metabolic syndrome, ophthalmological involvement, inflammatory bowel disease, cholestasis, and neutrophilic cholangitis [Citation3,Citation21]. In children with GPP, hyperlipidemia, infection, and electrolyte disorders were commonly seen [Citation21]. Joint involvement in the form of arthralgia or arthritis has been reported in 23.8% to 34.7% of GPP patients [Citation19,Citation22,Citation24]. The presence of arthritis often necessitates the use of systemic steroids even in patients with mild GPP, and steroid withdrawal in these patients has been reported to be a trigger for acute GPP flares [Citation19]. Uveitis has been reported in 3.2% of patients with acute GPP [Citation19].

3.4.3. Mortality in GPP

Flares in GPP can be difficult to treat, and systemic complications during flares may occasionally result in death [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19,Citation24,Citation27].

In an analysis of 106 GPP patients, a mortality rate of 32% was reported (follow-up period was not specified). Twenty-six of the 34 deaths were directly attributable to illness severity or to the treatment for GPP, especially the use of systemic steroids [Citation27]. In more recent studies, deaths attributable to GPP flares were reported in about 5–10% of GPP patients [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19,Citation24]. Sepsis or septic shock was the common cause of death in GPP [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19].

3.5. Humanistic burden of GPP

No evidence was identified regarding activities of daily living, caregiver burden, treatment adherence/satisfaction, occupational functioning, or psychosocial symptoms in GPP. Two publications provided data to support the findings described in this section, one of which was conducted exclusively in patients with GPP, while the second was in a general psoriasis population in which ‘pustular psoriasis’ constituted 3% of the sample (this study was included due to a paucity of data in GPP) ().

Table 3. Characteristics of publications reporting on the humanistic burden of GPP.

3.5.1. Quality of life

Data from Choon et al. indicated that GPP had a significant impact on QoL, even in the quiescent phase [Citation19]. This study used the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a 10-item questionnaire in which a score above 10 suggests severe QoL impairment, to assess how far GPP impacted patients’ lives. This study reported a mean DLQI score during a follow-up visit (i.e., non-flare period) of 12.4 points in patients with acute GPP (n = 102), indicating severe impairment. In the other subgroups, including subacute GPP, localized GPP, and impetigo herpetiformis (IH), the mean DLQI scores ranged from 13 to 17, again signifying severe impairment. At the time of QoL assessment, most (73%) patients had mild psoriasis symptoms while 10% had moderate-severe psoriasis (the remaining were either asymptomatic or lost to follow-up).

Sampogna et al. reported QoL in a subsample of 380 psoriasis patients from the IDI Multipurpose Psoriasis Research on Vital Experiences (IMPROVE) study, including those with PP (3%) (GPP-specific data, including information on the proportion of the sample with GPP, were not reported in this paper) [Citation28]. QoL was measured using the 36-item short form of the Medical Outcomes Study questionnaire (SF-36), in which responses to 36 questions are scored and summed according to a standardized protocol and expressed as a score on a 0–100 scale (a higher score represents better self-perceived health). Although no statistical analysis was provided, this study reported that QoL in PP was lower than that in plaque and guttate psoriasis and was comparable to that in palmoplantar and arthropathic psoriasis ().

Figure 3. Comparison of SF-36 scores across psoriasis subtypes.

Figure adapted, with permission, from Sampogna 2006 [Citation28].PF: Physical functioning; RP: Role physical; BP: Bodily pain; GH: General health; VT: Vitality; SP: Social functioning; RE: Role emotional; MH: Mental health.

![Figure 3. Comparison of SF-36 scores across psoriasis subtypes.Figure adapted, with permission, from Sampogna 2006 [Citation28].PF: Physical functioning; RP: Role physical; BP: Bodily pain; GH: General health; VT: Vitality; SP: Social functioning; RE: Role emotional; MH: Mental health.](/cms/asset/db6728fa-4106-4cc3-8644-d3dd9976ce5f/ierm_a_1708193_f0003_oc.jpg)

Sampogna et al. also reported that QoL decreased with increasing severity of psoriasis, as an example, SF-36 scores on the bodily pain domain of SF-36 for those with very mild, mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis were 73, 66, 62, and 47, respectively (p < 0.01) [Citation28]. In addition, emotional problems such as shame, anger, worry, and difficulties in daily activities and social life were seen in psoriasis patients, including those with PP. These problems increased with increasing disease severity.

3.6. Economic burden of GPP

No evidence was identified relating to the direct and indirect costs (including the economic impact on caregivers) established in GPP or regarding utilities in GPP. The publications providing data to support the findings described are summarized in . Healthcare resource utilization and economic burden were very variable by country and healthcare system.

Table 4. Characteristics of publications reporting on the economic burden of GPP.

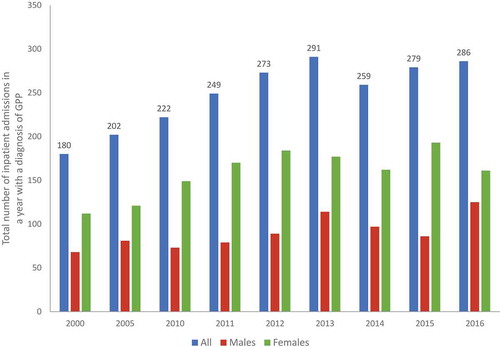

3.6.1. Healthcare resource utilization

Resource utilization during flares is accounted for by management of the acute episode of GPP using systemic treatments, often involving an inpatient hospitalization. In a large observational study (n = 102), an average of one hospitalization (range 1–20) was reported for each patient over a follow-up period of around 5 years [Citation19]. Hospitalization data from the Federal Health Monitoring System in Germany indicated approximately 250–300 inpatient admissions each year due to GPP from 2011 onwards () [Citation29]. In the study reported by Wu et al., the average duration of hospitalization was 11.6 (±10.2) days among patients with preceding plaque psoriasis and 12.1 (±6.7) days in those without preceding plaque psoriasis, and the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.816) [Citation25]. Across the three data sets [Citation23,Citation25,Citation29], the duration of hospitalization was about 10–14 days, which was considerably shorter than the 30-day average hospitalization reported in an older study [Citation18].

Figure 4. Total number of GPP hospitalizations in a year in Germany 2000–2016.

Source: Federal Health Monitoring System http://www.gbe-bund.de/. Hospitalization data in the website (http://www.gbe-bund.de/) are reported at 5-year intervals for 2000–2010, and then annually from 2010.

During the non-flare period, resource utilization occurs in the form of visits to physicians, including dermatologists, and receipt of topical and systemic treatments for the prevention of flare recurrences and for the management of skin lesions [Citation19]. Detailed information regarding resource utilization during this period was not available.

3.6.2. Drivers of healthcare resource utilization

Hospitalization is a key driver for resource utilization in GPP. Specific triggers for hospitalization in PP were reported in a retrospective study [Citation30] in 38 recorded hospitalizations in France over a 15-year period (1990–2005). Triggers were identified in approximately 45% of hospitalizations, with the most common being infection (18%), treatment discontinuation (16%), and stress (16%) (n = 211 hospitalizations).

In a retrospective study in the Mayo Clinic [Citation18], female patients spent more time on average in hospital (38 days versus 22 days for male patients). The duration of hospitalization was also longer in patients with a positive history of PV (31 days versus 24 days for no PV history) and in those with hypocalcemia (37 days versus 27 days among those with no hypocalcemia).

4. Conclusion

4.1. Summary

This is the first structured review of the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden in GPP, and yields several interesting results. A major finding is the high burden of GPP, not only during acute flares but also during the post-flare period. Acute flares, which are serious episodes with considerable morbidity and mortality, are a hallmark of GPP. The morphology and distribution of cutaneous lesions and systemic manifestations have been thoroughly described in the literature. During the post-flare period, patients continue to experience plaque or pustular lesions and still require treatment, either to manage the lesions or to prevent widespread flares. Unfortunately, many of the treatments are associated with considerable side effects or precautions, such as osteoarticular symptoms, teratogenicity risk, and bone marrow depression. Finally, although QoL appears to be severely impaired during the post-flare period (noting that data to support this were drawn from a single study in an exclusive GPP population), little is known about the impact on other humanistic burden parameters during this period.

GPP is a rare disease, and the number of prevalence studies identified was small, with a wide range of prevalence rates reported. Differences in study design and definitions contribute to variability in prevalence estimates. The single GPP-focused population-based study reported a prevalence of 1.76 per million population [Citation20]. However, this study was conducted more than a decade ago, and only a subset of the dermatology wards (46 of 112) reported data on GPP patients. Ohkawara et al. [Citation17] reported data for a wider group of diagnoses (‘GPP and related disorders’), which may explain the higher rate of 7.46 cases per million population in that study. The other prevalence studies identified were focused on psoriasis overall, with an analysis of GPP within the overall population, and reported much higher prevalence rates. These studies were not focused on GPP, and it was not clear if the GPP diagnoses in these studies were sufficiently validated, which may explain the higher rates in these studies [Citation17].

A complete understanding of the economic impact of GPP could not be achieved as limited information was available and this was limited to the flare period. The available data suggest that patients with GPP experience at least one flare resulting in admission to a hospital every 1–5 years. Given the serious and potentially fatal nature of a flare, this represents a serious risk to GPP patients.

4.2. Limitations

One limitation is that although this is a comprehensive overview, it is not a systematic review, and the fact that studies were prioritized during selection may have resulted in the exclusion of potentially relevant data. However, most reliable studies were selected for detailed analysis, and it is therefore not expected that the conclusions of this review will be substantially impacted by the excluded literature.

In terms of the data included in this review, these were very limited. In particular, few reliable studies were available on the epidemiology of GPP, and the definitions and classifications of GPP used across studies were inconsistent, making inter-study comparisons difficult.

Evidence on the clinical burden of GPP is limited to a few studies of modest quality. Data on the population-level epidemiology of GPP were very limited; therefore, comparisons across geographic regions or assessment of variations due to race/ethnicity could not be conducted. Several of the larger studies on clinical burden were conducted and published many years ago, thus reducing the generalizability of the data to current patients. The published data consisted of cross-sectional studies or retrospective analyses, with no large, high-quality prospective observational studies. Additionally, the reporting of clinical burden differed across publications due to the absence of standardized instruments used for the assessment of disease severity and progression in observational studies. There is, therefore, insufficient information to understand the long-term burden in terms of frequency of flares, severity of disease in the post-flare/chronic period, and prognostic factors. Autoimmune conditions such as uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease are important comorbidities in psoriasis, although their occurrence and impact in GPP have not been sufficiently described in the literature [Citation31,Citation32].

The humanistic burden data included only one GPP-focused study in which QoL was assessed during the post-flare/chronic period. Lack of data notwithstanding, it should be noted that although objective measurement of QoL is precluded during a flare because of the life-threatening nature of the episode, the humanistic burden is clearly higher during a flare than in the post-flare period. The impact of GPP on functioning, occupational performance, or caregivers has not been examined.

For economic burden, data on direct/indirect costs and utilities were not identified, and very little data on resource utilization in the form of hospitalization and drivers of resource utilization were obtained. Resource utilization during the post-flare period has not been fully reported but needs to be considered as the lifetime economic burden for someone diagnosed with GPP would appear to be very high.

5. Expert opinion

Until very recently, GPP has been both poorly classified and inadequately studied, despite its significant clinical, humanistic, and economic burden. The recent ERASPEN consensus statement proposes a new and valuable classification system that may help to provide consistency in terms of how GPP is described and characterized in the future. This consensus classifies GPP into relapsing disease (more than one episode) and persistent disease (maintained over the course of more than 3 months) and also classifies patients on the basis of the presence or absence of PV. This differs slightly from the separation of GPP into patients with and without preceding plaque psoriasis, which tends to be seen across the literature. Multiple studies have reported the proportion of patients with and without preceding plaque psoriasis, and there are some data to suggest that these subtypes are actually phenotypically different. As recent findings from genetic studies suggest, patients with GPP without preceding plaque psoriasis may potentially be classified under AiKDs [Citation6,Citation7].

It is surprising that the frequency of flares associated with GPP is not generally reported in the literature. This could simply be because GPP is a rare and therefore a rarely studied condition. However, it may also be due to difficulties encountered in determining what constitutes a ‘flare’, as no consensus definition exists. The definition used by Choon et al. (GPP lesions involving more than 30% of the BSA) may be a useful way to define a significant flare [Citation19]. Alternatively, hospitalization may be used as a surrogate for the identification of significant flares. Validated scales to define and quantify disease activity including persistent disease and flares are needed.

Given the frequency and seriousness of flares, impaired quality of life, and limited safe treatment options available, it is clear that there exists a significant unmet need in this area. The frequency of hospitalizations due to GPP also does not appear to have changed over recent years. There is, therefore, a pressing requirement for the development of better treatments to reduce the overall burden of GPP not only for patients but also for their families and health-care providers overall.

The paucity of data in some aspects of this review highlights areas in which future studies are required to supplement our current understanding of the burden of GPP. Reliable studies are needed that focus on the population-level prevalence and incidence of GPP, to allow for comparisons across race/ethnicities and geographic regions. Future studies should utilize the European consensus statement, complete with subclassifiers. Long-term studies are required to characterize the clinical burden in terms of the frequency of flares (defined objectively), despite treatment. Additional information on disease severity in the post-flare/chronic period, and the proportion of patients who require continuous topical or systemic treatment for the prevention of flare recurrences, would also be valuable.

Studies to better characterize the humanistic and economic burden of disease during the natural history of this disease are urgently required in order to address our existing poor understanding of this area. Future studies should also aim to better describe the inter-relationship between clinical, humanistic, and economic burden, particularly the impact of clinical improvement or worsening on quality of life and resource utilization.

Five years from now, we expect that the ERASPEN consensus statement will have obtained widespread acceptance, and that observational studies will report more consistent data by using the definitions and classifications provided in this statement. We also expect more data to be generated on the frequency of flares in GPP, perhaps aided by the use of validated disease measures for flare assessment.

Article highlights

Limited literature notwithstanding, it is clear that GPP confers a significant clinical, humanistic, and economic burden.

Estimates of the prevalence of GPP vary widely across studies; in the single GPP-focused study identified, the prevalence rate was 1.76 cases per million population in France.

Three phases can be identified in the disease course of GPP; an initial pre-pustular phase is followed by a flare and then a post-flare chronic/quiescent period preceding the next flare.

GPP flares are life-threatening episodes, while plaques/pustules continue to occur in the post-flare period.

The most common precipitating factors for flares are the withdrawal of steroid treatment, pregnancy, infections, and hypocalcemia.

Hospitalizations are relatively common during flares, and patient QoL is severely impaired during the course of disease. Patients with GPP experience one flare resulting in admission every 1–5 years.

The persistence of lesions and recurrence of flares despite treatment highlights the unmet medical need for these patients.

It is understandable for a rare disease that data are limited; however, the scarcity of data is compounded by inconsistencies in definitions and classifications across studies.

The availability of the recent consensus statement will be helpful in generating more consistent evidence to help better understand this condition.

Declaration of interest

AK Golembesky and D Esser are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. S Kharawala and RL Bohn are paid consultants of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rachel Danks for assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. Editorial assistance was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. on behalf of the ERASPEN Network. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1792–1799.

- WHO [Internet]. Global report on psoriasis; 2015 [cited 2018 Jul 02]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204417/9789241565189_eng.pdf

- Yamamoto T. Palmoplantar pustulosis: A distinct entity with a close relationship to psoriasis. Dermatol Clin Res. 2015;1:1–7.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907–919.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: Pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17: E1214. pii.

- Akiyama M, Takeichi T, McGrath JA, et al. Autoinflammatory keratinization diseases: an emerging concept encompassing various inflammatory keratinization disorders of the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;90:105–111.

- Akiyama M. Early-onset generalized pustular psoriasis is representative of autoinflammatory keratinization diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):809–810.

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1021–1026.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132–138.

- Li Z, Yang Q, Wang S. Genetic polymorphism of IL36RN in Han patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in Sichuan region of China: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11741.

- Sugiura K, Takemoto A, Yamaguchi M, et al. The majority of generalized pustular psoriasis without psoriasis vulgaris is caused by deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2514–2521.

- Körber A, Mössner R, Renner R, et al. Mutations in IL36RN in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2634–2637.

- Kharawala S, Golembesky AK, Bohn RL, et al. The clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of palmoplantar pustulosis: a structured review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:2.

- Augey F, Renaudier P, Nicolas JP. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Zumbusch): A French epidemiological survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:669–673.

- Fabbri P. Psoriasis. From clinical diagnosis to new therapies. Florence, Italy: SEE-Firenze; 2004. ( (ISBN:978L000002112)).

- Lee J, Kang YS, Park JS, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis in Korea: A population-based epidemiological study using the Korean National Health Insurance Database. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:761–767.

- Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:68–71.

- Zelickson BD, Muller SA. Generalized pustular psoriasis: A review of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1339–1345.

- Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, et al. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: ANALYSIS of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:676–684.

- Azura MA, Alias F, Nurakmal B, et al. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriasis in paediatric population in Malaysia. Poster session presented at: 23rd World Congress of Dermatology–International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS); 2015 Jun 8–13; Vancouver, Canada.

- Lin M, Zhaoyang W, Lixin Z, et al. A clinical analysis of 103 cases of children with generalized pustular psoriasis. Poster session presented at: 23rd World Congress of Dermatology–International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS); 2015 Jun 8–13; Vancouver, Canada.

- Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(Suppl 1):S43–S54.

- Baker H, Ryan TJ. Generalized pustular psoriasis. A clinical and epidemiological study of 104 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:771–793.

- Jin H, Cho HH, Kim WJ, et al. Clinical features and course of generalized pustular psoriasis in Korea. J Dermatol. 2015;42:674–678.

- Wu X, Li Y. Clinical analysis of 82 cases of generalized pustular psoriasis. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2017;42:173–178 (article in Chinese).

- Popadic S, Nikolic M. Pustular psoriasis in childhood and adolescence: A 20-year single-center experience. Ped Dermatol. 2014;31:575–579.

- Ryan TJ, Baker H. The prognosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:407–411.

- Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Söderfeldt B, et al. Measuring quality of life of patients with different clinical types of psoriasis using the SF-36. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:844–849.

- The Federal Health Monitoring System [Internet] [cited 2018 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.gbe-bund.de/

- Lapeyre H, Hellot MF, Joly P. Current reasons for in-patient psoriasis management. Ann Dermatol Et Venereol. 2007;134:433–436.

- Fraga NA, Oliveira Mde F, Follador I, et al. Psoriasis and uveitis: a literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:877–883.

- Shimizu A, Kamada N, Matsue H. Generalized pustular psoriasis associated with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2013;4:192–193.