Food allergy prevalence is increasing, currently affecting 7.6% of children and 10.8% of adults in the United States [Citation1,Citation2]. Food allergy poses a considerable burden to patients and their families, with multiple dietary restrictions resulting in nutritional deficiencies, limitations in social activities and significant anxiety and emotional burden, stemming from the fear of accidental exposures and life-threatening anaphylaxis [Citation3,Citation4]. Fatalities due to food-related anaphylaxis are very rare.

Food oral immunotherapy has emerged as a novel form of intervention that may benefit patients in multiple ways: a) reducing the risk of accidental exposure reactions to cross-contaminated foods, b) decreasing the severity of allergic reactions in case of accidental exposure, c) improving quality of life by limiting the number of dietary and social restriction and reducing anxiety, and d) allowing varying amounts of food consumption for some patients if they wish to incorporate the food into their diet [Citation4].

Food oral immunotherapy (F-OIT) is the administration of allergenic food to food-allergic individuals, starting at a low dose and gradually increasing over time (buildup phase), with the aim of reaching a target dose (maintenance dose), that will be ingested daily long term. Dose increases occur in a medical facility, under supervision of a trained allergist, every 2 weeks or monthly, and the dose (provided it is tolerated) is then taken daily, at home, in between the buildup visits. Once the food-allergic individual reaches the target maintenance dose, they are considered ‘desensitized’ and this dose is taken regularly (usually daily) long term [Citation4]. The maintenance dose varies in different studies from smaller amounts that protect from accidental trace exposures to very large amounts that allow ad-lib consumption of the relevant food. Food immunotherapy research has focused on most of the common allergenic foods including peanut, tree nuts, milk, egg, wheat, and sesame.

Food-allergic patients of any severity of previous reactions (including anaphylaxis) are eligible for F-OIT, with the exception of a recent history of severe anaphylaxis to the food, requiring cardio-respiratory support and ICU admission. Patients with uncontrolled allergic co-morbidities (especially, uncontrolled asthma) are not eligible. Eosinophilic esophagitis, chronic undiagnosed gastrointestinal symptoms, heart disease, use of beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and pregnancy are also common contraindications [Citation5]. Importantly, patients should have a confirmed diagnosis of food allergy prior to initiating F-OIT; if there is uncertainty, an oral food challenge may be performed. Other factors to consider before the start of OIT are the ability of the patient and family to attend a number of appointments for dose escalation, to adhere to regular dosing, to comply with safe dosing rules and the time commitment required for this therapy.

The main benefit of F-OIT is the rise in the allergenic threshold of reactivity, post-therapy, which provides protection from accidental exposures. Research studies have also shown that successful desensitization is associated with a reduced severity of allergic reactions [Citation6]. Additional benefits include reduction in dietary restrictions, improvement in social interactions, less anxiety about allergic reactions, and an overall improvement in quality of life. For some patients, the therapy may only provide protection from accidental exposures, but for others, ad-lib consumption of the food may be achieved [Citation7].

F-OIT is not without risk. Allergic reactions generally occur during treatment, but these are usually mild or moderate in severity for most patients. Common allergic reactions include gastrointestinal symptoms (oral itching, abdominal pain), skin reactions (hives, angioedema), and respiratory symptoms (cough, wheeze). Anaphylaxis may also occur in 10–20% of patients, with studies reporting different rates [Citation6,Citation8]. Generally, allergic reactions are seen during the buildup and early maintenance phase, and tend to decrease significantly over time, with longer term maintenance. It has been observed that, frequently, co-factors such as infection or exercise are responsible for inducing allergic reactions during F-OIT; as a result, it is advised that patients avoid exercise for 2 hours after dosing and dosing may be interrupted or reduced during periods of illness (safe dosing rules) [Citation9]. It is generally accepted that F-OIT is a safe intervention, with significant patient benefits, provided it is performed by allergy specialists that have a good understanding of this therapy and that patients comply with the safety instructions.

Most studies have focused on single F-OIT, but this therapy may be performed to multiple foods simultaneously. Considering that a significant number of patients suffer from multiple food allergies, this may be a preferred option for them. Research studies on multi-food OIT have generally shown a good safety profile, comparable with the one in single food OIT [Citation10]. The main difference when comparing single versus multi-food OIT is the time required to reach maintenance, which is much longer for multi-food OIT. However, studies that have used a combination of F-OIT with a biologic appear to have overcome this issue, with the duration of therapy comparable to single F-OIT [Citation11].

Currently, the only FDA-approved product available for F-OIT is for the treatment of peanut-allergic individuals 4–17 years of age. Multiple practices also offer OIT with non-standardized food allergens (also known as ‘off-label’ OIT). No studies exist currently comparing these two approaches. F-OIT in the younger population of infants and toddlers (also known as ‘early OIT’) has shown promising results in both efficacy and safety, with the majority of treated patients achieving desensitization. Vickery et al. showed that 81% of participants 9–36 months old achieved desensitization and 78% achieved sustained unresponsiveness after 3 years of peanut oral immunotherapy [Citation12]. The landmark IMPACT study showed that in 96 participants aged 1–3 years who were reactive to 500 mg or less of peanut protein at baseline, 71% were successfully desensitized to 2000 mg peanut protein per day after receiving peanut oral immunotherapy for 134 weeks. Additionally, after 26 weeks of peanut avoidance, 21% achieved remission, with younger age and lower baseline peanut-specific IgE shown to be predictive of remission [Citation13]. It is important to consider that a number of infants and toddlers will naturally outgrow their food allergy (especially for milk and egg, less so for peanut, tree nuts, and seeds); therefore, F-OIT will need to be discussed within this context with parents and caregivers during a shared decision-making process.

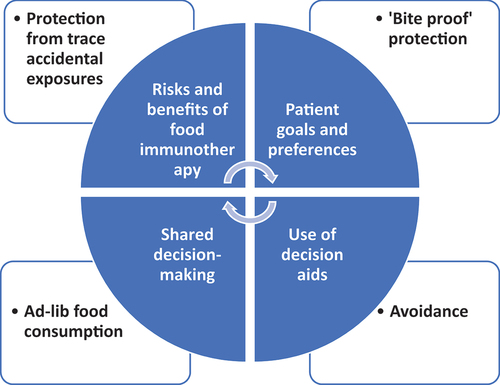

Recent developments in the field of food allergy such as food oral immunotherapy have shifted the management approach from passive avoidance to more active forms of therapy. As a result, patients now have more than one choice in how to manage their food allergy and the process of making the right decision for each patient involves shared decision-making (SDM) [Citation14]. In SDM, both the patient and the physician have an important role to play; patients should communicate their goals and preferences clearly, whereas the physician is responsible for making the correct diagnosis and informing the patients of their options and risks and benefits of each [Citation14]. The aim is to reach a decision that fits the individual patient’s needs based on their values and preferences. Decision-aids have also been developed to help patients and families with the SDM process for OIT () [Citation15].

Expert opinion

The future looks promising for food allergy therapies and F-OIT is likely only the first development, in an area that has been previously neglected for too long, and is finally seeing significant progress. Research performed so far has shown very encouraging results in terms of efficacy and safety of various F-OIT approaches. We are in need of more data that address long-term outcomes in F-OIT, including patient-reported outcomes. Research studies focusing on diverse patient populations, as well as real-world studies on non-selected patient cohorts are also needed. The ultimate goal of obtaining a ‘cure’ for food allergy has not yet been achieved, but many will argue that offering management choices and options to food-allergic individuals is a major achievement toward the right direction. The future will likely include biologics, either as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to F-OIT, as well as the use of different routes for allergen immunotherapy, including sublingual, mucosal, and epicutaneous. The microbiome field also has the potential to play a role in future treatments, with manipulation of the gut microbiome to benefit food-allergic individuals. Multiple studies are currently underway examining novel therapeutic approaches that may significantly benefit food-allergic patients, decrease food-related anxiety, and improve quality of life.

Declaration of interest

A Anagnostou reports institutional funding from Novartis, Aimmune Therapeutics, and FARE (Food Allergy Research and Education) and personal fees (consultation and speaker services) from DBV Technologies, ALK, and FARE. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gupta RS. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011 July;128(1): e9–17.

- Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e185630.

- DunnGalvin A, Blumchen K, Timmermans F, et al. APPEAL-1: a multiple-country European survey assessing the psychosocial impact of peanut allergy. Allergy. 2020(April):1–10. DOI:10.1111/all.14363

- Sicherer SH, Noone SA, Munoz-Furlong A. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2001;87. DOI:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62258-2

- Anagnostou K. Food immunotherapy for children with food allergies: state of the art and science. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:798–805.

- Vickery BP, Vereda A, Casale TB, et al. AR101 oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2018:379;1991–2001. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1812856

- Mack DP, Greenhawt M, Turner PJ, et al. Information needs of patients considering oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:1391–1402.

- Anagnostou K, Islam S, King Y, et al. Assessing the efficacy of oral immunotherapy for the desensitisation of peanut allergy in children (STOP II): a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014:383(9925);1297–1304. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62301-6

- Anagnostou K, Clark A, King Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose peanut oral immunotherapy with factors predicting outcome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03699.x

- Begin P, Winterroth LC, Dominguez T, et al. Safety and feasibility of oral immunotherapy to multiple allergens for food allergy. Allergy, Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014;10. DOI:10.1186/1710-1492-10-1

- Andorf S, Purington N, Kumar D, et al. A phase 2 randomized controlled multisite study using omalizumab-facilitated rapid desensitization to test continued vs discontinued dosing in multifood allergic individuals. Lancet. 2019;7:27–38.

- Vickery BP, Berglund JP, Burk CM, et al. Early oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe and highly effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017:139;173–181.e8. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.027

- Jones SM, Kim EH, Nadeau KC, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy in children aged 1–3 years with peanut allergy (the immune tolerance network IMPACT trial): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2022:399(10322);359–371.DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02390-4

- Anagnostou A, Hourihane JOB, Greenhawt M. The role of shared decision making in pediatric food allergy management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;46–51. DOI:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.004

- Greenhawt M, Shaker M, Winders T, et al. Development and acceptability of a shared decision-making tool for commercial peanut allergy therapies. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2020 Feb. DOI:10.1016/j.anai.2020.01.030