ABSTRACT

Introduction

The complex nature of Sjögren’s Disease (SjD) necessitates a comprehensive and patient-centered approach in both diagnosis and management. This narrative review emphasizes the need for a holistic understanding of the connection between salivary gland inflammation and oral symptoms in SjD.

Areas covered

The intricate relationship between salivary gland inflammation and dry mouth is explored, highlighting the variability in associations reported in studies. The association of the severity of xerostomia and degree of inflammation is also discussed. The frequent presence of recurrent sialadenitis in SjD further accentuates the connection of compromised salivary gland function and inflammation. The review additionally discusses local inflammatory factors assessed through salivary gland biopsies, which could potentially serve as predictors for lymphoma development in SjD. Insights into compromised quality of life and hypercoagulable state and their association with salivary gland inflammations are provided. Advancements in noninvasive imaging techniques, particularly salivary gland ultrasonography and color Doppler ultrasound, offer promising avenues for noninvasive assessment of inflammation.

Expert opinion

There is a need for longitudinal studies to unravel the connections between salivary gland inflammation and oral symptoms. This will enhance management strategies and optimize treatment outcomes for SjD patients.

1. Introduction

Sjögren’s Disease (SjD), or Sjögren’s syndrome as it is also known [Citation1], is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease, typified by exocrine gland tropism and is mainly characterized by fatigue, and dryness (sicca) complaints of eyes and mouth related to lymphocytic infiltration of the lacrimal and salivary glands. Since SjD is a systemic disease, patients may experience a variety of other disease manifestations and related conditions, including but not limited to arthritis, interstitial lung disease, polyneuropathy, and lymphoma [Citation2]. Several of these symptoms and disease manifestations lack specificity for SjD and may be indicative of other underlying causes. However, it is the unique combination of these symptoms that differentiates a patient as having SjD rather than another disease.

Until now, we do not possess a gold standard to diagnose the disease, i.e. a single test with high sensitivity and high specificity which can successfully discriminate patients with SjD from non-SjD controls. As a result, a variety of diagnostic tests are implemented in the clinical work-up. In order to ensure homogeneous populations of SjD patients in research, numerous classification criteria for SjD have been proposed throughout the decades. The criteria are intended to classify patients for studies, with the 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria representing the most recent and popular one [Citation3]. Classification criteria such as the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria are also commonly used to diagnose SjD. However, a patient can be diagnosed based on expert’s opinion as having SjD when the patient does not match the classification criteria yet, but the signs rigorously suggest that the patient has SjD (it is a clinical diagnosis).

The most common element to all classification criteria is the evaluation of salivary gland inflammation. The degree of inflammation in salivary glands of SjD patients is histopathologically characterized by periductal clusters of ≥50 lymphocytes, called foci. The number of foci per 4 mm2 glandular parenchyma can be calculated into a focus score (FS) [Citation4,Citation5]. For the classification of SjD, biopsies with an FS ≥ 1 are considered positive [Citation3]. However, it is important to note that the focus score can also be ≥1 in healthy individuals and in patients with various other medical conditions. Relying solely on the focus score is insufficient for diagnosing a patient with SjD. Other histopathological features important in diagnosing SjD are the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions and germinal centers, and a relative increase of IgG and IgM plasma cells compared with the number of IgA plasma cells (plasma cell shift) [Citation6–10]. Furthermore, salivary glands of SjD patients contain higher proportions of fibrosis and acinar atrophy than controls [Citation11–13].

This comprehensive review aims to identify available knowledge about salivary gland inflammation status and distinct oral related symptoms in SjD.

2. Dry mouth and salivary gland inflammation

Dry mouth is a debilitating symptom that can significantly impact the quality of life of patients with SjD. The term ‘dry mouth’ encompasses xerostomia, salivary gland hypofunction, and hyposalivation [Citation14]. Xerostomia is defined as ‘the subjective feeling of oral dryness,’ whereas salivary gland hypofunction is an objectively decreased saliva secretion (i.e. below normal secretion) [Citation15,Citation16]. Hyposalivation refers to a diagnosis when saliva secretion becomes pathologically low, as measured objectively (i.e. unstimulated whole saliva flow rate ≤0.1 to 0.2 mL/min and/or stimulated whole saliva flow rate ≤0.5 to 0.7 mL/min) [Citation17–19]. The terms xerostomia, salivary gland hypofunction, or hyposalivation are not synonymous and should not be used interchangeably. Of note, although commonly a low salivary flow rate causes xerostomia, a low salivary flow rate can also be seen in subjects with no xerostomia and vice versa. A sensation of xerostomia is linked to a reduction of the flow rate in at least 50% of the individuals original flow rate [Citation15].

2.1. Xerostomia and salivary gland inflammation

Numerous studies have delved into the connection between salivary gland inflammation and the occurrence and intensity of xerostomia. However, only a limited number have directly investigated this link from the perspective of patients. In a cohort study by Pijpe et al., findings from 23 SjD patients revealed that 91% experienced a dry mouth, with 78% of those patients exhibiting a positive minor salivary gland biopsy or a positive biopsy of the parotid gland [Citation20]. Interestingly, SjD patients not reporting dry mouth showed varying results in their biopsies, either positive or negative for SjD. In a more recent study, Janka and colleagues similarly could not report a clear association between inflammation and xerostomia symptoms [Citation21]. Their investigation into SjD patients demonstrated that the presence of xerostomia was not consistently linked to a minor salivary gland biopsy compatible with SjD. This suggests that numerous factors, like the original flow rate of that person, polypharmacy, mouth breathing, or psychogenic factors, may contribute to sicca symptoms [Citation14,Citation16].

When it comes to the severity of xerostomia, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, it was observed that sicca symptoms significantly decreased in a subgroup of SjD patients treated with rituximab. In this subgroup, notable reductions in lymphocytic infiltration, B-cells, germinal centers, and lymphoepithelial lesions in the parotid gland parenchyma were observed [Citation22,Citation23]. These findings suggest a potential association between the severity of xerostomia and the degree of infiltrating B cells in a patient.

2.2. Hyposalivation and salivary gland inflammation

Hyposalivation can cause a dry or sticky feeling in the mouth, difficulty in swallowing, and an increased risk of dental cavities and gum disease. Numerous studies have shown that salivary flow rate, e.g. total or gland-specific saliva, stimulated or unstimulated saliva, is not strongly associated with salivary gland histopathology. In a study assessing salivary gland scintigraphy, histopathology, and salivary flow, Kim and coworkers reported among others that unstimulated and stimulated flow rate showed a correlation with focus score or number of leukocyte common antigen (LCA) of approximately ρ = 0.5 (p < 0.001) [Citation24]. In an in-depth analysis, Mossel and colleagues showed that in the 41 included SjD patients, correlations between histopathological features of parotid gland biopsy and stimulated parotid salivary flow were fair (ρ = −0.123 for focus score and ρ = −0.259 for percentage of CD45+ infiltrate) [Citation25]. The authors concluded that histopathology and salivary flow are complementary measurements that cannot directly replace each other in the workup of SjD [Citation25].

3. Sialadenitis and salivary gland inflammation

Sialadenitis is a frequently observed condition, particularly in the general pediatric population, often presenting as an isolated incident linked to viral or bacterial infections [Citation26]. Recurrent sialadenitis is commonly seen in individuals with SjD. More specifically, recurrent parotitis has been noted to occur more frequently in individuals with childhood-onset SjD compared to those with adult-onset SjD, as reported by Gong et al. in 2023 [Citation27]. In children with SjD, it is even the most prevalent manifestation of SjD [Citation28]. The affected salivary glands exhibit characteristic symptoms of swelling, inflammation, and pain, accompanied by erythematous and warm overlying skin (). Some patients may also experience fever, with a purulent discharge often secreted from the duct during gland massage (). Enlarged regional lymph nodes are a frequent accompanying feature of sialadenitis.

Figure 1. Acute bacterial sialadenitis: swollen and painful parotid gland with erythematous and warm overlying skin. This figure was previously published in the book “Mondziekten, Kaak-en Aangezichtschirurgie, Handboek voor Mondziekten, Kaak- en Aangezichtschirurgie” by A. Vissink, F.K.L. Spijkervet and co-authors. 2023| ISBN 9789023258629. Copyright permission from the publisher Uitgeverij Van Gorcum B.V. was obtained.

Figure 2. Acute bacterial sialadenitis: purulent discharge from the orifice of the parotid duct is seen when the gland is massaged. This figure was previously published in the book “Mondziekten, Kaak- en Aangezichtschirurgie, Handboek voor Mondziekten, Kaak-en Aangezichtschirurgie” by A. Vissink, F.K.L. Spijkervet and co-authors. 2023| ISBN 9789023258629. Copyright permission from the publisher Uitgeverij Van Gorcum B.V. was obtained.

In cases of acute bacterial sialadenitis, bacteria invade salivary glands, primarily due to an ascending infection originating in the oral cavity [Citation29,Citation30]. The decreased salivary flow, often coupled with factors like sialoliths, mucous plugs, adhesions, strictures, or ductal malformations, contributes to this condition. Saliva’s inherent antibacterial properties, along with its flow that clears debris and impedes bacterial entry into ducts, ordinarily protect salivary glands. However, the compromised natural barrier in SjD significantly increases the risk of bacterial sialadenitis in SjD [Citation31]. Expressing the gland’s contents and stimulating its activity may contribute to symptom reduction. When antibiotics are necessary, they should be administered for an adequate duration, typically at least 2 weeks or until symptoms completely resolve. Insufficient antibiotic treatment may lead to an early relapse of the condition. While hyposalivation associated with acute bacterial and viral sialadenitis is usually temporary and self-limiting in otherwise healthy individuals, patients with SjD often endure persistent hyposalivation. In cases of sialolithiasis, symptoms manifest differently, typically initiating with recurrent, mealtime-related swellings of the affected gland. Radiologically or through ultrasound, a sialolith is often observable in the duct of the affected gland, though not always as it can be radiolucent.

Chronic bacterial sialadenitis typically initiates with an episode of acute bacterial sialadenitis and is often associated with Staphylococcus aureus [Citation30]. In individuals with SjD, chronic bacterial sialadenitis typically affects the parotid gland unilaterally or bilaterally. This condition is commonly associated with ductal obstruction, often caused by mucous plugs, strictures, and/or adhesions. In the submandibular gland, the development of chronic sialadenitis is frequently linked to the presence of a mucous plug or sialolith. The primary pathogenic event involves a decrease in saliva secretion rate, leading to stasis of secretions and subsequent ascending bacterial invasion of the ductal system [Citation32]. The swelling may persist from days to months, and after resolving, clinical quiescence may range from weeks to years [Citation30]. Expressing the gland’s contents might help, occasionally antibiotics are needed (for details see above).

Recent studies have revealed potentially promising outcomes associated with sialoendoscopy in patients with SjD. This positive impact might be attributed to the dilation performed during the endoscopic procedure, combined with the efficacy of ductal irrigation. This dual approach appears to play a role in opening ductal strictures and effectively removing debris, including microsialoliths and mucous plugs [Citation33,Citation34]. Similarly, also positive effects of just ductal irrigation, with or without the use of corticosteroids, are reported with a procedure as used in sialography [Citation35]. Future studies, however, should confirm the positive effect of sialoendoscopy in patients with SjD.

4. MALT and salivary gland inflammation

A serious complication of SjD is the 5–10% lifetime risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas (NHL), with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma being the most common subtype in SjD [Citation36,Citation37]. These lymphomas most frequently manifest in the parotid gland, and the transition from variable to persistent gland enlargement serves as a concerning clinical indicator for the potential presence of MALT. While not pathognomonic, the presence of palpable purpura, vasculitis, renal involvement, and peripheral neuropathy, particularly when combined with factors like monoclonal gammopathy, reduced complement C4 levels, CD4+ T lymphocytopenia, a sharp increase in IgG levels, or cryoglobulinemia, should heighten suspicion for MALT in SjD patients [Citation38–42].

The identification of SjD patients at risk of developing NHL remains a challenge, but certain predictors have been recognized. These encompass systemic factors, such as disease activity, persistent glandular enlargement, lymphadenopathy, palpable purpura, anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies, rheumatoid factor, lymphopenia, declined C3 or C4 levels, and cryoglobulinemia, as well as local inflammatory factors assessed through salivary gland biopsies [Citation42–44]. In a study by Risselada and colleagues, patients who went on to develop NHL exhibited a significantly higher lymphocytic focus score compared to those who did not (3.0 ± 0.894 vs. 2.25 ± 1.086; p = 0.021) [Citation45]. Risselada et al. determined that a focus score threshold of ≥3 foci had a positive predictive value of 16% for lymphoma and an impressive negative predictive value of 98% [Citation45]. Additionally, Theander et al. proposed germinal centers (GC) in labial gland biopsies as potential predictors of lymphoma in SjD patients [Citation46]. In their study, among the 43 patients with GC-like structures, 14% developed lymphomas, whereas only 0.8% of the 135 GC-negative patients did (p = 0.001). However, contradicting results were presented by Haacke et al., who reported that the presence of GC in labial gland biopsies did not differ significantly between SjD patients who developed parotid MALT lymphoma and those who did not develop a lymphoma [Citation47]. Consequently, they suggested that the presence of GCs in labial glands was not identified as a predictive factor for SjD-associated parotid MALT lymphomas.

5. Quality of life and salivary gland inflammation

Beyond the distinctive symptoms directly associated with SjD, patients often face additional challenges, including but not limited to fatigue, anxiety, and depression, collectively wielding a profound influence on their overall quality of life. A study by Miglianico et al. sheds light on the multifaceted impact of SjD, revealing that in SjD patients, general fatigue aligns with heightened pain levels and elevated Interleukin-5 (IL5) concentrations [Citation48]. Intriguingly, lower motivation and fatigue demonstrate an upward trajectory with advancing age and increased serum levels of Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt-3 ligand). In contrast, in sicca controls, depression, anxiety, and fatigue exhibit no discernible associations with inflammatory variables [Citation48].

The intricate interplay between IL-5 and Flt-3 ligand in the realm of inflammation unfolds through distinct mechanisms. IL-5, with its primary influence on eosinophils, assumes a critical role in allergic responses and conditions characterized by heightened eosinophilic inflammation. Conversely, Flt-3 ligand, by fostering the development of dendritic cells, significantly amplifies antigen presentation and immune responses integral to inflammation. While these findings strongly suggest an association between serum inflammatory markers and the overall quality of life, a plausible postulation emerges: the same inflammatory markers localized in the salivary glands might, indeed, contribute substantially to the compromised quality of life observed in patients grappling with SjD.

6. Hypercoagulable condition and salivary gland inflammation

The association between inflammation status and a hypercoagulable state is well established, and chronic inflammation can profoundly impact the coagulation system in various autoimmune diseases [Citation49]. Notably, conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), dermatomyositis, and psoriasis are linked to an increased susceptibility to venous thromboembolism [Citation50]. In the context of SLE, abnormally elevated D-dimer levels have been identified as a significant risk factor for thrombosis [Citation51] (Wu et al., 2008). Adding to this body of knowledge, recent research by Wang et al. revealed higher D-dimer levels in patients with SjD compared to healthy controls, along with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels [Citation52]. The authors interpret these findings as indicative of a correlation between hypercoagulation and inflammation, providing a partial explanation for the heightened risk of embolism observed in patients with SjD [Citation52].

7. Imaging techniques in detecting salivary gland inflammation in Sjogren’s disease

7.1. Ultrasonography of the major and minor salivary glands

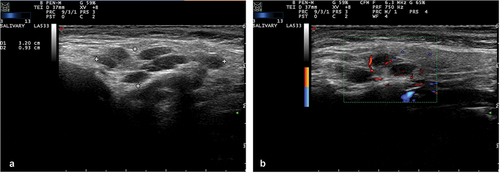

Ultrasonography of the major salivary glands (SGUS) has gained considerable attention in recent years as a promising imaging modality for SjD (). Offering a noninvasive, non-irradiating, cost-effective, and relatively straightforward approach suitable for outpatient settings, SGUS has become a valuable tool for the diagnostics and for follow-up examinations in SjD [Citation53]. There has been consideration regarding the potential of SGUS to replace more invasive methods, such as salivary gland biopsy, in the diagnostic workup of SjD to assess salivary gland inflammation. Limited studies directly compared salivary gland inflammation assessed through salivary gland biopsy with ultrasonographic findings of the same biopsied gland. In a study by Mossel and colleagues, it was shown that the absolute agreement between SGUS and parotid gland biopsy outcome was good (83%). Additionally, a negative SGUS predicted negative parotid gland biopsy (86%) [Citation54]. In a more recent in-depth investigation by the same authors, a moderate-to-good association was established between parotid gland ultrasound scores and salivary gland histopathology, including focus score (ρ = 0.510) and the percentage of CD45+ infiltrate (ρ = 0.560) in parotid gland biopsies [Citation25]. Several studies have investigated the benefit of adding SGUS to the ACR/EULAR classification criteria to determine its effect on diagnostic performance [Citation55–58]. Le Goff et al. described improved sensitivity of 97.4% when SGUS was added to the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria, compared to a sensitivity of 91.1% without SGUS [Citation55]. Similarly, Geng and colleagues reported an increase in sensitivity (90.8% vs 85.6%), while the loss in specificity was minimal (83.7% vs 82.2%) when adding SGUS to the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria [Citation56]. In a study by the EULAR ultrasound Sjögren syndrome Task Force SGUS was attributed a score of 1, which is similar to other minor classification criteria [Citation57]. Van Nimwegen and colleagues assessed the replacement of labial gland histopathology with SGUS in the classification criteria. This resulted in a significant decrease in sensitivity (82.2% vs 95.6%) [Citation58]. It can be concluded that adding SGUS to the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria improves diagnostic performance, but SGUS cannot replace histopathology as a criterion.

Figure 3. (a) Grey-scale salivary gland ultrasonography (SGUS) image of Sjögren’s disease (SjD) patient with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the right parotid gland. Characteristic for SjD are the hypoechoic areas and inhomogeneity of the tissue. (b) Color doppler (CD) ultrasound image of the same patient as in figure 3A. Diffuse vascular signals within the right parotid gland are observed.

In addition to major salivary gland ultrasonography, the role of ultra-high frequency minor salivary gland ultrasonography (UHFUS) has recently been studied by Ferro et al. and Izzetti et al. [Citation59,Citation60]. In two studies, they describe a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 71% for UHFUS compared to a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 86% for biopsy. Labial salivary gland inhomogeneity, as visualized by UHFUS, was significantly greater in patients with SjD compared to non-SjD sicca controls [Citation59]. In addition, inhomogeneity of the minor salivary glands had a moderate-to-high association with focus score (ρ = 0.531, p ≤ 0.001) [Citation60]. Furthermore, patients with high UHFUS scores had significantly more foci. The authors conclude that UHFUS, when used in combination with minor salivary gland biopsy, can potentially improve biopsy accuracy.

7.2. Color Doppler ultrasound (CD)

Color Doppler ultrasound (CD), a technique that utilizes ultrasound to detect the difference between emitted and received frequencies of moving particles, presents a promising avenue for assessing the vascularization of salivary glands (). Specifically, it offers a means to theoretically evaluate inflammatory activity in cases of SjD [Citation61]. The CD method allows for the examination of blood flow within the salivary gland parenchyma, providing valuable insights into the vascular aspects associated with inflammatory processes. Despite the potential of CD in this context, there is currently a notable scarcity of comprehensive data regarding the assessment of salivary gland inflammation in individuals with SjD using CD. Recently, Hocevar and colleagues developed a new CD ultrasound scoring system to evaluate glandular inflammation in SjD [Citation62]. The proposed scoring system showed a good inter-reader reliability and excellent intra-reader reliability in static images and in real-life patient examinations. Studies about the association of CD and histopathological parameters of salivary gland parenchymal inflammation of the parotid and minor salivary glands, e.g. focus score, number of CD20 cells, number of CD3 cells, presence of lymphoepithelial lesions, area of fibrotic or fat tissue, are eagerly awaited. This exploration could contribute valuable information for enhancing our understanding of the disease and could possibly refine diagnostic and follow-up approaches.

7.3. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT)

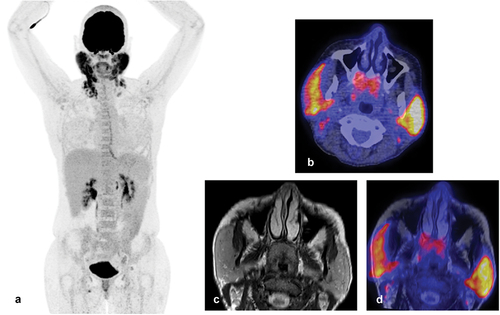

Another emerging imaging technique in SjD is positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). PET/CT combines gamma scanner images with CT images to acquire both anatomical and metabolic information about the salivary glands and potentially present lymphomas () [Citation63]. Van Ginkel and colleagues validated the usefulness of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) as a tracer to exclude SjD-associated lymphomas in SjD patients without PET abnormalities. Of note, metabolically active cells, such as tumor and inflammatory cells, show relatively high uptake of FDG. In addition, they describe that PET/CT can be used to detect systemic manifestations of SjD and can assist in guiding to the best biopsy location when patients are suspected of a SjD-associated lymphoma [Citation64]

Figure 4. (a) Whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose(FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan of the same patient as in figure 3a/b. Intense FDG-uptake is observed in both parotid glands and in the neck region. (b) FDG-PET/CT image showing increased uptake in both parotid glands and cervical lymph nodes. In addition, physiological FDG-uptake in the adenoids is observed. (c) T2 Magnetic resonance image (MRI) image showing diffuse enlargement of both parotid glands associated with MALT lymphoma. Figure 4d: Fused transversal FDG-PET/MRI image.

7.4. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic Resonance imaging (MRI) is a technique which uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to visualize anatomical structures. MRI and MRI sialography, featuring enhanced spatial resolution, can both generate three-dimensional images of the ductal system. MRI (sialography) adds value to the diagnostic process and might be contemplated for patients suspected of having SjD when the diagnosis remains uncertain after ultrasound examination [Citation65]. However, the routine application of MRI in the diagnostic work-up of SjD is not standard practice. In SjD patients, MRI presently plays a major role in local staging of SjD-associated lymphomas due to its high spatial resolution () [Citation63–65].

8. Treatment of salivary gland inflammation and its impact on oral symptoms

8.1. Local therapies

Treatment of oral dryness remains challenging, with studies providing limited evidence [Citation66]. Important to consider is that local treatment is purely symptomatic and has no effect on salivary gland inflammation. Options for local treatment of oral symptoms consist of stimulation of residual salivary gland function and/or the use of saliva substitutes [Citation67]. Stimulation of salivary glands can be achieved non-pharmacologically and pharmacologically. Non-pharmacological treatment options include sugar-free chewing gums, chewing tablets, and acid-free lozenges, whereas pharmacological stimulation can be achieved by parasympathomimetic drugs such as pilocarpine and cevimeline and should be prescribed to patients with some residual salivary flow [Citation66]. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported significant improvements in oral dryness complaints in patients using pilocarpine and cevimeline [Citation68]. However, prescription should be carefully considered due to the common occurrence of side effects. In patients with severe glandular dysfunction, saliva substitutes temporarily offer lubrication and hydration of oral tissues to alleviate oral dryness [Citation69].

8.2. Systemic therapies

During the last 20 years numerous RCTs have been conducted to find systemic biological therapies for treating SjD [Citation22,Citation23,Citation70–73]. Unfortunately, the results are conflicting, and no definitive solution has been discovered yet to fit all patients. The latter might be attributed to the systemic nature of the disease and the heterogeneity of disease manifestations patients present with [Citation74]. Some well-studied biologicals used to treat SjD patients are the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab and the fusion molecule of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTL-4) and IgG1 also known as abatacept. Regarding rituximab, Devauchelle-Pensec and colleagues found no significant difference in dryness visual analogue scale (VAS) in patients treated with rituximab compared to placebo [Citation70]. Similarly, Bowman et al. report no significant improvements in oral dryness VAS and stimulated whole saliva flow rate. However, they did find a significant improvement in unstimulated whole saliva flow rate [Citation75].

In contrast to the studies of Devauchelle-Pensec et al. and Bowman et al., Meijer and colleagues describe a statistically significant increase in stimulated whole saliva and improvement in dry mouth VAS rating in the patient group treated with rituximab compared to placebo [Citation22]. Furthermore, Delli and colleagues report a major reduction in lymphocytic infiltration and decrease in B cells, germinal centers, and lymphoepithelial lesions in repeated parotid gland biopsies in the same patient cohort [Citation23], suggesting that reducing salivary gland inflammation can lead to improvement of oral symptoms. This study even suggested that baseline inflammatory infiltration of salivary glands, as depicted with the number of CD20+ B cells/mm2 of glandular parenchyma, might serve as a factor to predict patients’ response to rituximab treatment. In a recent phase II RCT, a combination of rituximab and belimumab showed promising results with near-complete depletion of minor salivary gland CD20 B cells and increased and more sustained depletion of CD19 B cells compared to belimumab and rituximab monotherapies and placebo [Citation76]. A phase III trial is still awaited to see if this combination improves oral dryness symptoms.

In addition to rituximab, two RCTs have studied the effect of abatacept on oral symptoms [Citation71,Citation73]. However, no significant effect on saliva flow rate and xerostomia has been reported [Citation71,Citation73]. New biologicals are being developed constantly. Furthermore, biologicals used in treating other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, offer new potential treatment options for SjD. The effects of these biologicals on salivary gland inflammation, saliva flow rate and oral dryness symptoms are currently being studied. Examples of these biologicals are ianalumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the B-cell activating factor receptor (BAFF-R), and anifrolumab, a monoclonal antibody blocking the type I interferon receptor [Citation77,Citation78]. Initial results of treatment with ianalumab are encouraging as increased stimulated saliva flow rate was reported in a dose–response trial by Bowman and colleagues [Citation77]. A phase III RCT will have to confirm this preliminary finding. Regarding anifrolumab, no results have been published yet.

9. Epilogue

SjD presents a complex clinical landscape with diverse manifestations and diagnostic challenges. Until now, studies comparing the intensity of xerostomia and the degree of hyposalivation to salivary gland inflammation report conflicting data with poor to moderate associations. Direct comparison of histopathology with imaging techniques, salivary flow measurements, and saliva composition data could help in further investigating the connection between salivary gland inflammation and oral symptoms in SjD.

10. Expert opinion

Salivary gland inflammation and oral-related symptoms stand out as hallmark features in SjD. Not only are salivary gland inflammation and salivary secretion pivotal criteria for classification, but oral symptoms, especially oral dryness, also commonly represent the primary reason patients seek medical attention, often leading to a diagnosis of SjD. Despite this prominence, a limited number of studies have directly explored the intricate relationship between glandular inflammation, the resulting impact on salivary secretion and oral manifestations.

To advance our understanding, future research, from an oral perspective, should adopt a longitudinal approach, investigating both objectively measured and subjectively reported oral symptoms in conjunction with salivary gland inflammation and its impact on salivary secretion. Specifically, the focus should extend to oral dryness complaints and salivary gland flow (including stimulated and unstimulated, and whole and glandular-specific flow rates), associating these parameters with inflammatory markers such as the focus score, the number of CD20 and CD3 lymphocytes per mm2 of glandular parenchyma, the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions, germinal centers, and the relative increase of IgG and IgM plasma cells compared to IgA plasma cells. Special attention is warranted to determine whether changes in oral dryness align with corresponding alterations in salivary gland inflammation and, if so, to determine which changes.

Longitudinal studies also hold the promise of offering valuable insights into the crucial aspect of predicting lymphoma development in individuals with SjD. By consistently and systematically assessing inflammatory parameters in the major salivary glands at the moment of diagnosis and over an extended period, researchers may uncover patterns and trends that could serve as early indicators of the potential progression to lymphoma. In this respect, multiple biopsies over time from the same salivary gland might be helpful. In particular, biopsies of the parotid gland, as these are often the site of a MALT lymphoma in SjD patients, might be helpful. Understanding how these inflammatory markers evolve over time could contribute to the better understanding of specific risk profiles associated with lymphoma development in SjD patients. Moreover, this prognostic insight could be instrumental in tailoring more personalized and targeted management strategies for individuals with SjD diagnosed with lymphoma and may emerge linking specific inflammatory profiles to treatment outcomes, thereby optimizing the management of SjD patients. Similarly, when a lymphoma has developed, these studies might also discover biomarkers which can be of help to know when a lymphoma needs treatment as well as to monitor the treatment effect.

The compromised quality of life in SjD, characterized by fatigue, depression, and anxiety, as well as hypercoagulability and their association to salivary gland inflammation and salivary gland function, is underexplored and necessitates focused research. Investigating the link between salivary gland inflammation, salivary gland function, and these conditions could unravel the underlying mechanisms and guide the development of targeted interventions.

Addressing current technical and methodological limitations in diagnostic and follow-up approaches is crucial for advancing research in salivary gland inflammation and its association with oral symptoms in SjD. Non-invasive imaging techniques, notably salivary gland ultrasonography and CD ultrasound, offer promising avenues for assessing inflammation. The emergence of new ultrasound scoring systems, coupled with correlations between ultrasound findings and histopathological parameters, suggests a paradigm shift toward more accessible and patient-friendly diagnostic tools. This advancement has the potential to significantly shape the trajectory of future research in the field, paving the way for enhanced understanding and management of SjD. Similarly, FDG-PET/CT can assist in excluding SjD-associated lymphomas in patients without PET abnormalities, possibly leading to a decrease in invasive biopsies in suspected lymphoma patients. FDG-PET/CT has shown this potential, but new hybrid camera systems are currently being developed, which provide better spatial resolution images (around 3–4 mm), decrease scan duration and radiation dose, and will have increased diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, new and specific tracers to image infectious and inflammatory diseases are constantly being developed and will further enhance the use of PET in detecting inflammatory diseases and lymphomas.

Article highlights

Salivary gland inflammation has a poor to moderate association with severity of xerostomia and hyposalivation.

Focus score has been proposed as a potential marker for MALT lymphoma development.

Salivary gland ultrasonography, color Doppler ultrasonography, and PET-CT offer new approaches to the diagnostic workup of SjD patients.

Local treatment options can be used to treat oral dryness symptoms but do not affect salivary gland inflammation.

While there is some evidence that rituximab reduces salivary gland inflammation in SjD patients, data are conflicting about improvements in saliva flow rate and oral dryness reduction.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to AWJM Glaudemans for providing the MRI and PET-CT images used in .

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baer AN, Hammitt KM. Sjögren’s disease, not syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Jul;73(7):1347–1348. doi: 10.1002/art.41676

- Rahman A, Giles I. 18. Rheumatology. In: Feather A, Randall D, Waterhouse M, editors. Kumar & clark’s clinical medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020. p. 411–469.

- Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, et al. 2016 American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):9–16. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210571

- Chisholm DM, Mason DK. Labial salivary gland biopsy in Sjögren’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 1968;21(5):656–660. doi: 10.1136/jcp.21.5.656

- Fisher BA, Jonsson R, Daniels T, et al. Standardisation of labial salivary gland histopathology in clinical trials in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1161–1168. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210448

- Kroese FGM, Haacke EA, Bombardieri M. The role of salivary gland histopathology in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: promises and pitfalls. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:S222–33.

- Risselada AP, Looije MF, Kruize AA, et al. The role of ectopic germinal centers in the immunopathology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42(4):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.07.003

- Ihrler S, Zietz C, Sendelhofert A, et al. Lymphoepithelial duct lesions in Sjögren-type sialadenitis. Virchows Arch. 1999;434(4):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s004280050347

- Zandbelt M, Wentink J, de Wilde P, et al. The synergistic value of focus score and IgA% score of sublabial salivary gland biopsy for the accuracy of the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome: a 10-year comparison. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(7):819–823. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.819

- Bodeutsch C, de Wilde PCM, Kater L, et al. Quantitative immunohistologic criteria are superior to the lymphocytic focus score criterion for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1075–1087. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350913

- Van Ginkel MS, Nakshbandi U, Arends S, et al. Increased diagnostic accuracy of the labial gland biopsy in primary Sjögren’s syndrome when multiple histopathological features are included. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023 Oct 4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37791984. doi:10.1002/art.42723

- Llamas-Gutierrez FJ, Reyes E, Martínez B, et al. Histopathological environment besides the focus score in Sjögren’s syndrome. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(8):898–903. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12502

- Leehan K, Pezant N, Rasmussen A, et al. Minor salivary gland fibrosis in Sjögren’s syndrome is elevated, associated with focus score and not solely a consequence of aging. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(Suppl 112):80–88.

- Simms ML, Kuten-Shorrer M, Wiriyakijja P, et al. World workshop on oral medicine VIII: development of a core outcome set for dry mouth: a systematic review of outcome domains for salivary hypofunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023;135(6):804–826. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2022.12.018

- Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115(4):581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(87)54012-0

- Delli K, Spijkervet FK, Kroese FG, et al. Xerostomia. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;24:109–125. doi: 10.1159/000358792

- Mercadante V, Jensen SB, Smith DK, et al. Salivary gland hypofunction and/or xerostomia induced by nonsurgical cancer therapies: ISOO/MASCC/ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(25):2825–2843. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01208

- Heintze U, Birkhed D, Björn H. Secretion rate and buffer effect of resting and stimulated whole saliva as a function of age and sex. Swed Dent J. 1983;7(6):227–238.

- Sreebny LM. Saliva in health and disease: an appraisal and update. Int Dent J. 2000;50(3):140–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00554.x

- Pijpe J, Kalk WW, van der Wal JE, et al. Parotid gland biopsy compared with labial biopsy in the diagnosis of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(2):335–341. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel266

- Janka M, Zalatnai A. Correlations between the histopathological alterations in minor salivary glands and the clinically suspected Sjögren’s syndrome. Pathol Oncol Res. 2023 May 15;29:1610905. doi: 10.3389/pore.2023.1610905

- Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Vissink A, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab treatment in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Apr;62(4):960–968. doi: 10.1002/art.27314

- Delli K, Haacke EA, Kroese FG, et al. Towards personalised treatment in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: baseline parotid histopathology predicts responsiveness to rituximab treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Nov;75(11):1933–1938. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208304

- Kim JW, Jin R, Han JH, et al. Correlations between salivary gland scintigraphy and histopathologic data of salivary glands in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Oct;41(10):3083–3093. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06269-x

- Mossel E, van Ginkel MS, Haacke EA, et al. Histopathology, salivary flow and ultrasonography of the parotid gland: three complementary measurements in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 May 30;61(6):2472–2482. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab781

- Baszis K, Toib D, Cooper M, et al. Recurrent parotitis as a presentation of primary pediatric Sjögren syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012 Jan [cited 2011 Dec 19];129(1):e179–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0716

- Gong Y, Liu H, Li G, et al. Childhood-onset primary Sjögren’s syndrome in a tertiary center in China: clinical features and outcome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2023;21(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12969-022-00779-3

- Legger GE, Erdtsieck MB, de Wolff L, et al. Differences in presentation between paediatric- and adult-onset primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39 Suppl 133(6):85–92. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/vxe6h0

- Cascarini L, McGurk M. Epidemiology of salivary gland infections. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;21(3):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2009.05.004

- Carlson ER. Diagnosis and management of salivary gland infections. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;21(3):293–312. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2009.04.004

- Delli K, Spijkervet FK, Vissink A. Salivary gland diseases: infections, sialolithiasis and mucoceles. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;24:135–148. doi: 10.1159/000358794

- Bradley PJ. Microbiology and management of sialadenitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2002;4(3):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s11908-002-0082-3

- Karagozoglu KH, Vissink A, Forouzanfar T, et al. Sialendoscopy increases saliva secretion and reduces xerostomia up to 60 weeks in Sjögren’s syndrome patients: a randomized controlled study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Mar 2;60(3):1353–1363. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa284

- Karagozoglu KH, Mahraoui A, Bot JCJ, et al. Intraoperative visualization and treatment of salivary gland dysfunction in Sjögren’s Syndrome patients using contrast-enhanced ultrasound sialendoscopy (CEUSS). J Clin Med. 2023 Jun 20;12(12):4152. doi: 10.3390/jcm12124152

- Tucci FM, Roma R, Bianchi A, et al. Juvenile recurrent parotitis: diagnostic and therapeutic effectiveness of sialography. Retrospective study on 110 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;124:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.06.007

- Giannouli S, Voulgarelis M. Predicting progression to lymphoma in Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10(4):501–512. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.872986

- Voulgarelis M, Ziakas PD, Papageorgiou A, et al. Prognosis and outcome of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjögren syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31824125e4

- Ioannidis JP, Vassiliou VA, Moutsopoulos HM. Long-term risk of mortality and lymphoproliferative disease and predictive classification of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(3):741–747. doi: 10.1002/art.10221

- Theander E, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Mortality and causes of death in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1262–1269. doi: 10.1002/art.20176

- Fox RI. Sjögren’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366(9482):321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5

- Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, et al. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):796–803. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041186

- Delli K, Villa A, Farah CS, et al. World workshop on oral medicine VII: biomarkers predicting lymphoma in the salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome—A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2019;25 Suppl 1(S1):49–63. doi: 10.1111/odi.13041

- Fragkioudaki S, Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Predicting the risk for lymphoma development in Sjogren syndrome: an easy tool for clinical use. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(25):e3766. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003766

- Nocturne G, Virone A, Ng WF, et al. Rheumatoid factor and disease activity are independent predictors of lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(4):977–985. doi: 10.1002/art.39518

- Risselada AP, Kruize AA, Goldschmeding R, et al. The prognostic value of routinely performed minor salivary gland assessments in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1537–1540. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204634

- Theander E, Vasaitis L, Baecklund E, et al. Lymphoid organisation in labial salivary gland biopsies is a possible predictor for the development of malignant lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(8):1363–1368. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144782

- Haacke EA, van der Vegt B, Vissink A, et al. Germinal centres in diagnostic labial gland biopsies of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome are not predictive for parotid MALT lymphoma development. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1781–1784. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211290

- Miglianico L, Cornec D, Devauchelle-Pensec V, et al. Identifying clinical, biological, and quality of life variables associated with depression, anxiety, and fatigue in pSS and sicca syndrome patients: a prospective single-centre cohort study. Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89(6):105413. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105413

- Marzano AV, Tedeschi A, Polloni I, et al. Interactions between inflammation and coagulation in autoimmune and immune-mediated skin diseases. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10(5):647–652. doi: 10.2174/157016112801784567

- Ramagopalan SV, Wotton CJ, Handel AE, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseases: record-linkage study. BMC Med. 2011 [cited 2011 Jan 10];9:1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-1

- Wu H, Birmingham DJ, Rovin B, et al. D-dimer level and the risk for thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1628–1636. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01480308

- Wang Q, Dai SM. An interaction between the inflammatory condition and the hypercoagulable condition occurs in primary Sjögren syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42(4):1107–1112. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06498-0

- Delli K, Dijkstra PU, Stel AJ, et al. Diagnostic properties of ultrasound of major salivary glands in Sjögren’s syndrome: a meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2015;21(6):792–800. doi: 10.1111/odi.12349

- Mossel E, Delli K, van Nimwegen JF, et al. Ultrasonography of major salivary glands compared with parotid and labial gland biopsy and classification criteria in patients with clinically suspected primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(11):1883–1889. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211250

- Le Goff M, Cornec D, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Comparison of 2002 AECG and 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria and added value of salivary gland ultrasonography in a patient cohort with suspected primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1475-x

- Geng Y, Li B, Deng X, et al. Salivary gland ultrasound integrated with 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria improves the diagnosis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(2):322–328. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/13u0rt

- Jousse-Joulin S, Gatineau F, Baldini C, et al. Weight of salivary gland ultrasonography compared to other items of the 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Intern Med. 2020;287(2):180–188. doi: 10.1111/joim.12992

- van Nimwegen JF, Mossel E, Delli K, et al. Incorporation of salivary gland ultrasonography into the American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Apr;72(4):583–590. doi: 10.1002/acr.24017

- Ferro F, Izzetti R, Vitali S, et al. Ultra-high frequency ultrasonography of labial glands is a highly sensitive tool for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome: a preliminary study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020 Jul;38 Suppl 126(4):210–215.

- Izzetti R, Ferro F, Vitali S, et al. Ultra-high frequency ultrasonography (UHFUS)-guided minor salivary gland biopsy: a promising procedure to optimize labial salivary gland biopsy in Sjögren’s syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021 May;50(5):485–491. doi: 10.1111/jop.13162

- Jousse-Joulin S, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Cornec D, et al. Brief report: ultrasonographic assessment of salivary gland response to rituximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1623–1628. doi: 10.1002/art.39088

- Hočevar A, Bruyn GA, Terslev L, et al. Development of a new ultrasound scoring system to evaluate glandular inflammation in Sjögren’s syndrome: an OMERACT reliability exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(8):3341–3350. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab876

- Vissink A, van Ginkel MS, Bootsma H, et al. At the cutting-edge: what’s the latest in imaging to diagnose Sjögren’s disease? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. [cited 2023 Nov 13];20(2):135–139. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2023.2283588

- van Ginkel MS, Arends S, van der Vegt B, et al. FDG-PET/CT discriminates between patients with and without lymphomas in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(10):3323–3331. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead071

- Rao Y, Xu N, Zhang Y, et al. Value of magnetic resonance imaging and sialography of the parotid gland for diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome. Int J Of Rheum Dis. 2023;26(3):454–463. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14528

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Bombardieri S, et al. EULAR-Sjögren Syndrome Task Force Group. EULAR recommendations for the management of Sjögren’s syndrome with topical and systemic therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jan;79(1):3–18. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216114

- Al Hamad A, Lodi G, Porter S, et al. Interventions for dry mouth and hyposalivation in Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2019 May;25(4):1027–1047. doi: 10.1111/odi.12952

- Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas AG, Stone JH, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010 Jul 28;304(4):452–460. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1014

- Alpöz E, Güneri P, Onder G, et al. The efficacy of xialine in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a single-blind, cross-over study. Clin Oral Investig. 2008 Jun;12(2):165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0159-3

- Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Feb 18;160(4):233–242. doi: 10.7326/M13-1085

- Baer AN, Gottenberg JE, St Clair EW, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept in active primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results of a phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Mar;80(3):339–348. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218599

- van Nimwegen JF, Mossel E, van Zuiden GS, et al. Abatacept treatment for patients with early active primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (ASAP-III study). Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 Mar;2(3):e153–e163. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30160-2

- de Wolff L, van Nimwegen JF, Mossel E, et al. Long-term abatacept treatment for 48 weeks in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: the open-label extension phase of the ASAP-III trial. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2022 Apr;53:151955. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2022.151955

- Gandolfo S, Bombardieri M, Pers JO, et al. Precision medicine in Sjögren’s disease. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024 May 6;S2665-9913(24):00039–0. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(24)00039-0

- Bowman SJ, Everett CC, O’Dwyer JL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab and cost-effectiveness analysis in treating fatigue and oral dryness in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jul;69(7):1440–1450. doi: 10.1002/art.40093 Erratum in: Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Oct;72(10):1748.

- Mariette X, Barone F, Baldini C, et al. A randomized, phase II study of sequential belimumab and rituximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. JCI Insight. 2022 Dec 8;7(23):e163030. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.163030

- Bowman SJ, Fox R, Dörner T, et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous ianalumab (VAY736) in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet. 2022 Jan 8;399(10320):161–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02251-0

- Mathian A, Felten R, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, et al. Type 1 interferons: a target for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs). Joint Bone Spine. 2024 Mar;91(2):105627. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105627