ABSTRACT

This paper provides a speech stylistic analysis of Barack Obama’s 2016 Athens speech, and it argues for a culturally conscious take on speech style, which links it to the accumulation of political capital, at least in the context of political speeches. With a focus on stance and intertextuality, the main argument put forward is that Obama constructs a dialogue with Ancient Greek thought, which does not simply draw on experiences and events; rather, it recreates them and, eventually, it creates a whole understanding of cultural politics. Against this take on politics based heavily on Greek democracy legacy, for Obama, his performance serves as his consignment to the global political discourse through an effort to join a very well established and highly respected democratic tradition stemming from (Ancient) Greece, whose sociocultural impact is felt vividly in contemporary US. In this sense, his accumulation of political capital serves as his effort to achieve posthumous fame (ystero’fimia) after his stepping down from the US administration.

1. Introduction

Speech style is considered to be one of the most important concepts in contemporary sociolinguistic scholarship (e.g. chapters in Rickford and Eckert Citation2001; Schilling-Estes Citation2004; Coupland Citation2007; chapters in Hernández-Campoy and Cutillas-Espinosa Citation2012). As such, it has been theorized extensively already since the beginning of the formation of sociolinguistics as a distinct field of inquiry. More specifically, speech style has been dealt with as ‘attention paid to speech’ (Labov [Citation1966] Citation2006), which means that style shifting along the (in)formality axis is the product of the amount of attention speakers pay to their monitoring of their speech. This approach has created a ‘Labovian axiom’ (Coupland Citation2007), which means that the more attention a speaker pays, the more formal their style will be, and vice versa. Due to its unidimensional, deterministic and mechanistic character, it has been argued that this approach is too narrow and, hence, cannot explain all cases of stylistic variation (Hernández-Campoy Citation2016: 91–93).

As an attempt to tackle these difficulties, came the speech style as ‘audience design’ approach (Bell Citation1984, Citation2001). This more responsive take on speech style has as its basic premise the idea that speakers design and employ their speech style with keeping in mind their audiences. Despite the fact that this model provides a fuller account of stylistic variation than the ‘attention paid to speech’ model, style shifting may not be essentially reactive but rather more agentive or proactive, inasmuch as speakers may be projecting their own identity, and not just responding to how others view them. To this end, the style as ‘speaker design’ approach (for an overview, see Hernández-Campoy Citation2016: 146–184) has been developed, whose gist is the consideration of speaker agency, namely both the reactive and proactive motivations for style-shifting (Hernández-Campoy Citation2016: 149; see also Makoni Citation2019). More specifically, stylistic variation can be seen as an initiative performance (cf. Coupland Citation2007), whereby speakers mix stylistic resources, both linguistic and semiotic ones, to construct and project identities.

An aspect of style that seems to be ignored in the aforementioned scholarship is that of culture. In the context of cultural discourse studies (e.g. Shi-xu Citation2012, Citation2016), culture is seen as ‘a historically evolved set of ways of thinking, concepts, symbols, representations (e.g. of the self and others), norms, rules, strategies’ (Shi-xu Citation2016: 2) embodied in the actions and ideologies of social groups, including politicians. The reason why it is important to consider cultural aspects of speech style is because culture goes hand in hand with identity construction, which in turn is the outcome, among other linguistic and semiotic resources, of speech style (cf. Theodoropoulou Citation2014, Citation2016). In light of this, I argue that political speech style is a culturally-based integrated communicative event (or a class thereof named activity), whereby politicians, like Obama, accomplish social interaction through linguistic and other symbolic means and mediums, in particular historical and cultural relations. In this sense, speech style is one of the cornerstones of cultural politics.

Against this theoretical backdrop of sociolinguistics of style, my study focuses on the political speech style of an individual (cf. Johnstone Citation1996, Citation2000), the former President of the US, Barack Obama, who is considered to be a charismatic orator (cf. Bligh and Kohles Citation2009). I see style as an agentive and, hence, active and creative process of mixing and matching (socio)linguistic resources (Coupland Citation2007), whereby an individual can constitute and portray a certain (or multiple types of) persona(e), identities and various understandings of self, which can shift over the course of a political speech, depending on the goals of the speaker and the audience reception of that speaker at different moments of their speech. At the same time, because I consider political speech style, I argue that the goals of the speaker, which depend on how the speaker will be perceived by their audience, also include the accumulation of political capital. According to Bourdieu (Citation1991: 192),

political capital is a form of symbolic capital, credit founded on credence or belief and recognition or, more precisely, on the innumerable operations of credit by which agents confer on a person (or on an object) the very powers that they recognize in him [sic] (or it).

Recognition of their personality, their (potential to engage in successful) administration and political service as well as recognition of completed administration is an important dimension of political capital for every politician, as it can pave the way for the continuation or successful, i.e. positively memorable, completion of their political careers. In this paper, I am looking at the concept of political capital from a micro perspective, considering its manifestation in the discourse itself. More specifically, I consider the ways whereby political capital is constructed in Barack Obama’s Athens speech in November 2016. Before I proceed with my analysis, though, a note on the context of Greek-American political relationships, as well as a critical discussion of my theoretical tools, which I use in my analysis, are in order.

2. Greek-American political relations

The bilateral relations between Greece and the United States (henceforth US), which were established in the 1830s, have historically been excellent.Footnote1 According to the website of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Greek-US bilateral relations are founded on long-term cooperation and go back to the philhellene movement that was prevalent in Europe and America in the early 19th century, in support of the Greek people’s struggle for independence. The two countries’ common values – freedom and Democracy – and their fighting together in the two World Wars, as well as their participation in NATO, the OSCE and other international organizations and treaties, form the strong foundations of Greek-US strategic cooperation.Footnote2

The arrival of Barack Obama as the President of the United States in Greece on Tuesday the 15th of November 2016 marked the fourth visit of a US President in the country. President Obama stayed in Athens for two days and he met with the then President Prokopis Pavlopoulos and the then Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. On Wednesday, the 16th of November 2016, the US President delivered his legacy speech in the packed out Stavros Niarchos Foundation, following a visit to the Acropolis. Speaking at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre earlier in the day, Obama, apart from his eulogy to Ancient Greek democracy, highlighted the need for Greece’s creditors to agree to debt relief, in accordance with the advice of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He noted that Greece, and especially its young people, needed to see hope and a future. President Obama sparked lots of enthusiasm and clapping during his speech among his audience at the Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, while his speech also triggered lots of mixed reactions in social media, given that it was live streamed. A linguistic analysis of how Obama’s speech was received in social media is beyond the scope of this paper.

Against this backdrop, and in an effort to understand how Obama employs the Greek-American friendship discourse as part of his political capital, the focus of this paper is on how Obama uses intertextuality, and stance in his speech for political purposes (cf. Shayegh and Nabifar Citation2012; Sheveleva Citation2012; Reyes Citation2014).

3. Intertextualizing stance and stancing intertextuality

Intertextuality translates into the way in which texts do not stand alone, but carry the traces of other texts in both form and content (Allen Citation2011: 342; Hodges Citation2015). Given that intertextuality is dealt with in the context of political speeches attended by audiences, text is seen as a performance and, hence, as ‘something that can be interpreted by an audience’ (Deumert Citation2014: 89). It is created through decontextualization of textual material, namely the lifting of this material from its original context, and its subsequent recontextualization in a new context. This recontextualization of words and ideas can be seen as an ‘active process of negotiation’ that creates meaning (Bauman and Briggs Citation1990: 69). Meaning is, therefore, ‘not the product of a single, isolated speech event; meaning in language results from a web of relationships linking current with past (and future) discourse’ (Tannen Citation2007: 9).

Irvine (Citation1996: 149) has claimed that ‘to animate another’s voice gives one a marvelous opportunity to comment on it subtly – to shift its wording, exaggeratedly mimic its style, or supplement its expressive feature’. The recontextualization of prior words is a joint, active process achieved by all those involved in the reporting context (cf. Kuo Citation2001). ‘Extra textual knowledge’ comes in the form of intertextual links to prior text types or tokens. The intertextual relationship among different texts necessarily entails what Briggs and Bauman (Citation1992) call an ‘intertextual gap’. This gap arises because the linking of particular utterances to generic (or prior text) models can never produce an exact fit by virtue of the fact that even prototypical and faithful re-creations always introduce some variation on the theme. Intertextuality ‘gives us ways of thinking of power and authority in discourse-based terms larger than those that are immediately and locally produced in the bounded speech event (interactional power)’ (Bauman Citation2005: 146). What this means is that the definition of intertextuality includes, apart from textual allusions, allusion to historical narratives, discourses and related sociopolitical and cultural ideologies.

In light of this, the focus of this paper is on how Obama makes use of the cultural and historical bonds of the US with Greece to position the political and cultural concept of ‘democracy’, and the context of being democratic. His political alignment reflects a growing interest in how language is used to encode or reflect specific ‘stances’ (cf. chapters in Jaffe Citation2009a). A stance is an expression, whether through overt assertion or through drawing inferences, of a speaker’s personal feelings, judgments, evaluations or commitments towards what they are talking about (Biber and Finegan Citation1989; Du Bois Citation2007; chapters in Englebretson Citation2007; Du Bois and Kärkkäinen Citation2012).

Stance has been dealt with as the way whereby people align themselves with a concept or topic, along with a focus on narratives of personal, and collective experience. According to Du Bois (Citation2007: 163), a stance is a social act, something we do through communication when we evaluate or align ourselves with objects or others, and such evaluations may reflect a host of issues from ethnicity, through formality, to politeness, and, eventually, captatio benevolentiae, namely the capture of audience’s benevolence. Jaworski and Thurlow (Citation2009) have argued that ‘the stance evaluation nexus appears to permeate all aspects of meaning making, all communicative functions, and all levels of linguistic production’ (Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2009: 197). Hence, stance can be seen as a relevant analytical tool in the analysis of the Obama speech.

The relationship between intertextuality and stance taking is a close one, given that stance is centrally implicated in the creation of intertextual links (Jaffe Citation2009b: 20). In the Obama speech considered here, there is a combination of individual stances (i.e. evaluation and expressiveness he expresses as an individual personality), and sociocultural stances (general beliefs and knowledge he shares as an American, who has interacted with members of the Greek-American community).

Having discussed the theoretical framework of this study, I now turn to a discussion of the methodology and data of this study.

4. Methodology and data

In order to address the use of intertextuality and stance taking by Obama, his speech, which was given in Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens on 11/16/2016, was watched by the author of the paper very carefully, and the White House transcript of the speechFootnote4 was also delved into in depth. The reason behind this close reading, and watching of the speech, was to make note of stylistic, discursive and rhetorical strategies (cf. Partington and Taylor Citation2018) that Obama employed in order to emphasize his intertextual references to Greece and democracy, which are analyzed immediately below.

Regarding the speech itself, it was delivered as Obama’s final, landmark foreign policy speech on what was his last overseas trip in office, first to Greece and then to Germany. Through it, he reflected on his eight-year presidency by focusing on the US’s foreign policy vis-à-vis its NATO allies, whose democracies can be seen as a pledge for a peaceful relationship with the US. Obama’s speech is a hymn to democracy with many references to Ancient and Modern Greek civilization, culture, people, and values, whose ultimate goal, as it was argued by a number of journalists, who covered Obama’s trip to Athens, was to ‘reassure Europe on the future of its relations with the United States’,Footnote5 after Obama’s end of administration, and the takeover by Donald J. Trump.

5. Obama’s intertextuality and stance taking

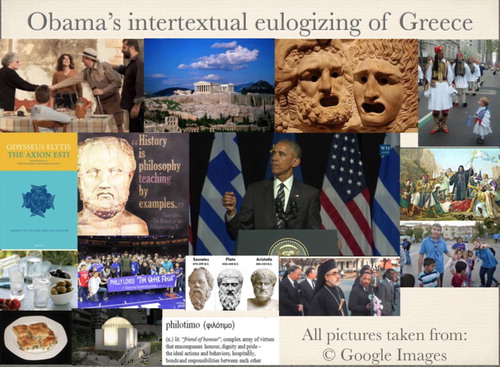

The emerging themes of Obama’s intertextuality include taking stance vis-à-vis the diachronic contribution of Greeks to knowledge, politics, culture, and religion (), culminating into the greatest legacy Greece has given the US and the world, which is democracy. Obama takes epistemic stance through his extensive use of evidential modals, such as ‘I believe’, ‘I’m confident that’, ‘it is my belief that’, etc., which he enhances through the precision-grip gesture (Lempert Citation2011), whose discussion, however, is beyond the scope of the paper. Given that his Athens speech is a panegyric one, namely a eulogic tribute to democracy, his evidentiality is characterized by higher degrees of certainty through reference to external evidence and epistemic markers of ‘fact’ (cf. Shayegh Citation2012).

At the very beginning of his talk, like he has always done during official visits to foreign countries, he greets his audience in their native language, in this case Greek, by code-switching between English and Greek (/yia sas/ – /kali’spera/) in an effort to achieve captatio benevolentiae, and to thus set his tone for what is about to follow. Obama’s speech style (cf. Nicola Citation2010; Alim and Geneva Citation2012) is characterized by what I call a ‘speaking in earnest’ dimension, which occurs in confessional moments of his talk. This is very evident already at the beginning of his talk, where he is explicit about it by framing it in terms of determination and appreciation for Greece’s contribution to the world:

As many of you know, this is my final trip overseas as President of the United States, and I was determined, on my last trip, to come to Greece – partly because I’ve heard about the legendary hospitality of the Greek people – your filoxenia. (Applause.) Partly because I had to see the Acropolis and the Parthenon. But also because I came here with gratitude for all that Greece – ‘this small, great world’ – has given to humanity through the ages.Footnote6

The first intertextual reference is made to one of the most widely known values of Greeks throughout their history, which is ϕιλοξενία (hospitality) (cf. Karakatsanis and Swarts Citation2007). By foregrounding it, and by framing it as ‘legendary’, Obama acknowledges it, takes it for granted, highlights it, and pays respect to his hosts for their showing of appreciation towards him. Later in his talk, he connects ϕιλοξενία to Greeks’ acceptance of refugees in North-Eastern Aegean islands, and, in this way, he acknowledges Greeks’ hospitality to these people, despite the crisis (cf. Andrikopoulos Citation2017). This paying of respect, of course, gets appreciated by his audience, who applaud. In this sense, Obama’s attempt to achieve captatio benevolentiae is met with success.

Shifting themes, but continuing on the same praising Greece footing, the second intertextual reference he makes is to the Acropolis in general, and Parthenon in particular, a place which he had visited just a couple of hours before his talk at SNF. As the symbol of democracy worldwide, Acropolis presents for Obama a great opportunity not only to ascertain his admiration to the democratic values, but also to reinforce his position as the then leader of his Democratic party. The fact that, due to security reasons, he was not able to give his speech at the Pnyx hill, like Emanuel Macron did in September 2017, has not discouraged him from making epistemic and emotional references to the hill, where democracy was born, in a metaphorical way. According to his own wording, ‘these are all concepts that grew out of this rocky soil’.

He starts his eulogy to democracy by employing the ‘asyndeton’ figure, whereby each sentence/phrase has an equal informational weight. More specifically, he starts off by making an explicit reference to America’s indebtedness to Greece for ‘the most precious of gifts – the truth, the understanding that as individuals of free will, we have the right and the capacity to govern ourselves’; this is the thematic preamble of democracy, which contains the gist of what this ideological system entails. Offering the etymology of the word ‘demokratia’, from ‘kratos’ – the power, the right to rule – and ‘demos’ – the people, he interprets it as the state of affairs that allows us to be citizens – not servants, but stewards of our society. He highlights the democratic concepts by presenting them through the rhetorical scheme of parallelism and asyndeton, and making, in this way, his intertextuality more stylistically rhythmic and, hence, more appealing to and memorable by his audience. He also emphasizes institutions, and their role in protecting the modus operandi of democracy, which is an indirect reference to the fact that, regardless of who the leader of a democratic country is, democracy is a concept that is (or should be) characterized by perpetuity, sustainability, and continuation.

As result of democracy, comes the natural inclination of people to freedom, and this is where Obama pays an intertextual tribute to Palaion Patron Germanos, as the Greek bishop, who raised the flag of independence for Greeks in 1821.Footnote7 Along the lines of his intertextual reference to the role of religion in Greece’s continuous presence in the world as an independent country, he also acknowledges that Greek Americans marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Alabama, demanding more civil, and human rights.Footnote8 The participation of Greek Americans in that marching is epitomized by Archbishop Iakovos, who has mentioned in one of his interviews that his participation was due to his need to take revenge for being treated as a slave, since he was born as a Greek in Turkey, where he and his community did not have any rights.Footnote9

The idea shared by both countries, Greece and US, that independence is a sine qua non for a harmonious and effective functioning is also implied in the explicit acknowledgement of the celebration of Greek Independence Day (which is on the 25th of March) all over the US, including a celebration at the White House. This celebration is always led by the President of the US, and a number of parades also take in major US cities, like Chicago, Obama’s hometown, including Greek evzones wearing their traditional foustaneles, and, of course, members of the Greek-American community. Obama integrates his religion-oriented intertextuality by referring to the Greek Orthodox church of St. Nicholas near Ground Zero; through this reference, he implies the important role that Greek Orthodox church in the US has played in comforting people, who lost their beloved ones on 9/11. Overall, all these references to various dimensions of the Greek Orthodox church should not come as a surprise, given the very close relationship between the church and every US President, which translates into influence of the former on the latter in Greek and Greek-Cypriot-related socio-political issues.

From his religious intertextual references, he shifts into more cultural discourses, including the presence of ‘evzones with their fousta’neles, while also acknowledging Greek food, which is extremely popular in the US. More specifically, he makes reference to spanakopita and ouzo. This seemingly more mundane type of gastronomic intertextual reference (compared to the previous, more spiritual ones) can be seen as an advertisement of Greek cuisine and Greek edible products exported to the US, something that can help the country overcome its financial crisis by boosting its GDP from exports of goods. In this sense, Obama tries to contribute towards the boosting of Greece’s export-related financial capital.

Along the same lines of an indirect advertisement of Greece should also be considered Obama’s reference to Giannis Antetokounmpo, a Milwaukee Bucks NBA player, who is a Greek citizen of Nigerian origin, and who is currently considered to be one of the rising stars in NBA. Due to his amazing performance in courts and his popularity with American, Greek, and Greek-American audiences, Antetokounmpo is also known as ‘Greek Freak.’ The very fact that Obama, as the then President of the US, who is known to be an avid fan of NBA, makes reference to a person, who is considered to be a legend in Greece due to his personal trajectory from the absolute poverty in Greece to a triumphant career in the US, has multiple meanings, and conveys multiple messages: to the people in Greece, it means that they should see him as a role model, and try to imitate his success in their own fields, and not just in sports. The message here is clear: work hard, capitalize on your talents, and success and worldwide recognition will come. Indeed, this is a message that Obama re-iterates in a more direct way, when he addresses the youth of Greece later in his speech, and urges them to stay in the country, work, and create for the benefit of their society, instead of leaving Greece, and contributing, in this way, to the brain drain of the country. The other message that the intertextual reference to NBA star Antetokounmpo conveys is to the people of the US (and, by extension, the rest of the world): Greece is an amazing tourist destination just as amazing as Antetokounmpo is in NBA courts. Again, we can see how the reference to an NBA star of Greek origin advertises in a strategic way Greece as a worthy travel destination for a big market, such as the US.

Moving on to the domain of literature, Obama makes his next intertextual reference to a verse belonging to the widely known poem ‘Axion esti’ by Greek Nobel laureate Odysseus Elytis: the emotionally stanced characterization of Greece as ‘this small, great world’, which epitomizes the great intellectual contribution of Greece to world history, culture, and civilization. In one of Elytis’ reflections on how and why he wrote this poem, he states that he decided to ‘shape his clamor as a liturgy’, and as a result of this he wrote Axion Esti, which was published in 1959. It is a long poem in which the speaker explores the essence of his being as well as the identity of his country, Greece, and Greek people.

Through an intertextual reference to this poem, Obama in his SNF speech can be argued to explore the essence of his political being as well as the identity of the US and American people. His speech, in that respect, can be seen as a reflection on his eight years of administration, and an effort to summarize his government’s achievements by linking them to the ideological background of democracy as envisioned and stipulated by Greeks throughout the history. This choice can be seen as a strategic move on behalf of Obama to frame his politics within democratic ideology, which is widely known, and accepted throughout the world. In this sense, this correlation serves to validate his administration by associating it with well-established democracy-related political capital, and, at the same time, to offer some verbal comfort to Greeks, who are suffering from the crisis, and whose collective morale was low, at least during the period that Obama visited Athens.

This morale seems to be lifted through Obama’s intertextual references to ancient Greek tragic poets, including Aeschylus and Euripides, along with his acknowledgement of historians Herodotus and Thucydides, who invented history as a field of inquiry. These intertextual references are complemented by his references to Greek philosophy, through the naming of two of its most important representatives, Socrates and Aristotle. The explicit intertextual tribute to some of the most important personalities of Ancient Greek period serves as Obama’s effort to construct a knowledgeable and appreciative persona with high political capital, whose educational background includes some exposure to Classics, a fact that always indexes prestige, cultivation, power, and depth of a politician worldwide. At the same time, in an indirect way, I argue that through these intertextual references, which create a cultured and cultural politics, Obama tries to distinguish himself from the then recently elected new President of the US, Donald J. Trump, whose take on politics turns out to be more utilitarian than culture-based. These references to ancient Greek intellectual contributions (cf. Hamilakis Citation2016) pave the way for Obama’s eulogy of ancient Greek democracy, which occupies most of his talk.

By drawing on a range of historical multicultural discourses (Ancient Greeks and Martin Luther King), Obama most insistently creates his political self, as other voices incorporated into an ongoing autobiographical political statement become the central organizing features of the resulting composite text (cf. Haviland Citation2005: 82). Connections across contexts of situation and a nexus of different genres (Lassen Citation2016) create understandings, establish relations, construct identities, and generally ‘yield social formations’ (Agha Citation2005: 4). However, in line with Briggs and Bauman (Citation1992: 158), ‘questions of ideology, political economy, and power must be addressed as well if we are to grasp the nature of intertextual relations’. One direction we could follow with respect to this is the propagation of truth claims and narratives that form the basis for what are typically defined as ‘ideologies’, namely systems of thoughts and ideas that represent from a particular angle and frame the organization of meaning, guiding actions, and legitimating positions. It is evident that Obama attunes himself to past discourse relevant to the birth of democracy in Ancient Greece looking for opportunities to hang on to these references, and by noticing them, renders them extractable (entextualizing them), moving them from the original context in which they were used (to recontextualize them). Through this process of entextualization, Obama is able to play off a particular discourse in a manner that heightens the prior text for moving and persuasive effect. Particularly skilled instances of intertextual play are acknowledged as enjoyable by the audience, who in turn index their excitement through applause.

Obama’s speech forwards a set of assumptions and explanations about the structuring of society, combining the classical democratic commitment to the notion that ‘we are citizens – not servants, but stewards of our society’ with liberal commitments on behalf of institutions, and elites they they need to be ‘more responsive to the concerns of citizens’. In this way, Obama’s speech is open to shifts and transformations, as the speaker as a social actor discursively interacts and carries prior text into new settings. Intertextuality in action, therefore, not only contributes to the propagation of hegemonic discourses, but also holds the key to understanding processes of social change.

The final intertextual reference he makes in his talk is to another key Greek cultural discourse, which is ϕιλότιμο [filotimo] (self-obligation to act in a socially sensitized way). In an emotional stance taking move, Obama identifies ϕιλότιμο with love, respect, and kindness for family, community, and country, and a sense that we’re all together in this, with obligations to each other. He uses it to wrap up his speech by associating it with Greeks’ generous offer to help all the refugees arriving at the Greek islands from war-hit countries, like Syria, via the shores of Turkey. He justifies people’s humanity and generousness on the basis of this culturally specific concept, which has been shaped over the years in circumstances of democracy, where what matters is to engage in active citizenship, and to work for common good. Obama’s attempt to talk about Greeks in cultural-psychological terms at this hard time can be seen yet again as his effort to praise their good deeds by simultaneously constructing for himself a profile of a compassionate vis-à-vis refugees and appreciative leader vis-à-vis Greece, enhancing, in this way, his political capital by adding to it a more ‘human’ dimension.

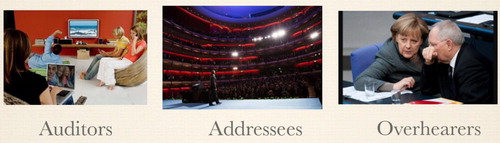

A vital factor, which has an impact on Obama’s use of intertextuality and stance, is his audience of this speech. Following the audience design framework (Bell Citation1984: 158ff.: Citation1991), there are four types of audience, which are relevant to the analysis: auditors, addressees, overhearers, and eavesdroppers. Auditors are known and ratified interlocutors of the speaker, which means that the latter knows that they are there and they have listening rights. Addressees are known, ratified and directly addressed audience of the speaker; as such, they are the immediate recipients of the speaker’s message. Overhearers are like auditors but they are not ratified. Finally, eavesdroppers are people who are not known to be present and, as such, they are not ratified or intentionally addressed.

In the case of Obama’s Athens speech, his audience is diverse and multidimensional (). More specifically, his auditors are all people, who have watched his speech from the screens of their TV sets, computers and smart phones; namely, auditors are people, who were not present together with Obama in the same venue, where the speech took place. On the other hand, addressees are the most immediate type of audience, in the sense that these are people, who were present at SNF Cultural Center and watched Obama’s speech while being in the same venue with Obama. Finally, overhearers, namely non ratified listeners/viewers of the speech, were the European commissioners and the members of the troika, who are currently monitoring Greece’s government, and its abiding by the MoUs they have signed. At the same time, they also evaluate the progress the country is making in terms of its economic activity. Synecdochically, these overhearers are represented by Chancellor Angela Merkel, and the then German Minister of Finance, Wolfgang Schäuble.

The bit of Obama’s Athens speech that targets his overhearers is the one, in which he hints at reducing Greece’s debt. This bit becomes particularly clear in the following excerpt from his speech:

I will continue to urge creditors to take the steps needed to put Greece on a path towards sustained economic recovery. (Applause.) As Greece continues to implement reforms, the IMF has said that debt relief will be crucial to get Greece back to growth. They are right. It is important because if reforms here are going to be sustained, people need to see hope, and they need to see progress.

6. Reflections

In light of the analysis, it can be argued that Obama’s intertextual styling drawing on a range of multicultural discourses results in the construction of a ‘political celebrity’ (cf. Redmond Citation2010; Coupland and Mortensen Citation2017: 255). In his talk, Obama has a relational style, in the sense that he shifts between his personal needs, aspirations, and dreams and his duties as the President of the US; these two in unison are then connected with themes, concepts and phenomena pertinent to the Greek (American) culture and civilization. Seen like this, his speech style is ‘locally grounded (viz. exhibiting cultural identity) and globally minded (viz. Obama is capable of engaging in international dialogue and showing global, human concerns)’ (Shi-xu Citation2012: 485), a fact that brings to the forefront the multicultural dimension of his stylistic performance.

Regarding Obama’s global mindedness, he uses his Athens speech to offer comforting words and moral support to Greeks as well as to offer indirect financial help to them via indirect advertisement of Greece. More specifically, through stancing intertextuality, Obama constructs his own personal style by drawing on and combining different elements pertinent to the birth and development of democracy in Greece. As a politician, it can be argued that he has carefully and reflexively designed a political capital accumulation-oriented speech (cf. Kienpointner Citation2013) that is made recognizable to his audience through very particular political capital-related resources, which are woven into his performed cultural politics. Such resources translate into historical knowledge, political skills, and personal resources, all of which have been argued to form important dimensions of political capital (Schugurnesky Citation2000: 6; Casey Citation2008). More specifically, through his Athens speech Obama indexes his factual knowledge of Ancient Greek democratic culture and Modern Greek needs, as evident in his intertextual references to important personalities and ideas, which have left their imprint in Western modus operandi of societies, including the US. At the same time, he has engaged in indexing procedural knowledge referring to the specific understanding of the rules of the political game not only in Greek-American bilateral relationships but also in America’s role in global politics as a peace keeper. These resources are intertextuality indexes, which tend to be iconized as co-referential with Obama himself. The fragments he has used, therefore, become indistinguishable from his political persona, which, itself, becomes indistinguishable from his person. They define his individual distinctiveness.

As a speaker, he exercises what Wilce (Citation2005) has called ‘strategies of intertextualization’, in an attempt to control how his words are taken up by his audience. Tannen (Citation2007) uses the term ‘constructed dialogue’ to refer to ‘reported speech’. In her concept, recontextualized words and information act not as verbatim descriptions but as ‘demonstrations’ that selectively depict their referents (Clark and Gerrig Citation1990). Through constructed dialogue, therefore, voices or sentiments attributed to a person can be typified. Despite the lack of continuity between the Ancient Greek code used by the quoted speakers and the English code used by Obama as a reporter to represent Ancient Greeks, the representations are nevertheless positioned as faithful quotations through expectations of verisimilitude. As Obama animates those voices, he embeds evaluations and imputes his own perspective on political events. This strategy of ‘transposition’ (Shoaps Citation1999) allowing Obama to present his view of events as self-evident appeals to common sense. In light of this, Obama’s constructed dialogue with Ancient Greek thought does not simply draw on experiences and events – it creates them and, eventually, it creates a whole new understanding of multicultural politics coupled with his securing of high political capital, which is essential for his (posthumous) fame as a President of the US and as a global leader.

Against this constructed take on politics based heavily on Greek democracy, for Obama, his performance serves as his consignment to the global political discourse through an attempt to join a very well established and highly respected democratic tradition stemming from (Ancient) Greece, whose sociocultural impact is felt vividly in contemporary US.

Such a culturally conscious and critical deconstruction of political speech style has shown that the theorization of the latter needs to incorporate innovative, appropriate and diverse analytical tools, such as intertextuality, stance and political capital, viewed from a polyprismatic perspective that takes into consideration the dialogue of multicultural discourses. In other words, at the heart of cultural discourse studies should be the tackling of speech style.

Acknowledgements

The first draft of this paper was presented at the 25th International Modern Greek Studies Association Symposium. I would like to thank the audience for a stimulating discussion and their helpful comments. Also, many thanks go to Thomas W. Gallant, Andonis Piperoglou and Shi-xu for their useful feedback. Any errors remaining are my own. Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Irene Theodoropoulou is Associate Professor of Sociolinguistics and Discourse Analysis at Qatar University. She is the author of Sociolinguistics of Style and Social Class in Contemporary Athens (2014, Benjamins) and co-editor of the Research Companion to Language and Country Branding (2020, Routledge).

Notes

1 The only exception to this could be considered the period after Andreas Papandreou’s ascendance to power in 1981 that sparked lots of criticism on behalf of the US (Phillips Citation1985).

2 https://www.mfa.gr/usa/en/greece/greece-and-the-usa/political-relations.html (accessed March 28, 2020).

3 https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/travels/president/greece (accessed March 28, 2020).

4 https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/11/16/remarks-president-obama-stavros-niarchos-foundation-cultural-center (accessed March 28, 2020).

5 https://www.voanews.com/a/obama-in-europe-germany-speech-/3598092.html (accessed March 28, 2020).

6 https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/11/16/remarks-president-obama-stavros-niarchos-foundation-cultural-center (accessed March 28, 2020).

7 https://greece.greekreporter.com/2017/05/30/palaion-patron-germanos-a-misunderstood-hero-of-the-greek-war-of-independence/ (accessed March 28, 2020).

8 http://www.pappaspost.com/video-turkish-born-archbishop-iakovos-marching-with-martin-luther-king-jr-was-duty-of-a-man-who-was-born-a-slave/ (accessed March 28, 2020).

9 https://usa.greekreporter.com/2017/01/16/archbishop-iakovos-why-i-supported-martin-luther-king-in-selma/ (accessed March 28, 2020).

References

- Agha, Asif. 2005. Introduction: Semiosis across encounters. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1: 1–5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43104034.

- Alim, H. Samy, and Smitherman. Geneva. 2012. Articulate while black: Barack Obama, language, and race in the US. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Allen, Graham. 2011. Intertextuality. London: Routledge.

- Andrikopoulos, Apostolos. 2017. Hospitality and immigration in a Greek urban neighborhood: An ethnography of mimesis. City and Society 29, no. 2: 281–304. doi:10.1111/ciso.12127.

- Bauman, Richard. 2005. Commentary: indirect indexicality, identity, performance: Dialogic observations. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1: 145–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43104044.

- Bauman, Richard, and Charles Briggs. 1990. Poetics and performances as critical perspectives on language and social life. Annual Review of Anthropology 19: 59–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.000423.

- Bell, Allan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13, no. 2: 145–204. doi:10.1017/S004740450001037X.

- Bell, Allan. 1991. Audience accommodation in the mass media. In Contexts of accommodation: Developments in applied sociolinguistics, ed. H. Giles, J. Coupland, and N. Coupland, 69–102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, Allan. 2001. Back in Style: Re-working Audience Design. In Style and Sociolinguistic Variation, ed. P. Eckert, and J. R. Rickford, 139–169. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Biber, Douglas, and Edward Finegan. 1989. Styles of stance in English: Lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and affect. Text-Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 9, no. 1: 93–124. 10.1515/text.1.1989.9.1.93.

- Bligh, Michelle C., and Jeffrey C. Kohles. 2009. The enduring allure of charisma: How Barack Obama won the historic 2008 presidential election. The Leadership Quarterly 20, no. 3: 483–92. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.013.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Briggs, Charles L., and Richard Bauman. 1992. Genre, intertextuality, and social power. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 2: 131–72. doi:10.1525/jlin.1992.2.2.131.

- Casey, Kimberly L. 2008. Defining political capital: a reconsideration of Pierre Bourdieu’s interconvertibility theory. Critique: A Worldwide Student Journal of Politics, Spring 2008. https://about.illinoisstate.edu/critique/Documents/Spring%202008/Casey.pdf.

- Clark, Herbert H., and Richard J. Gerrig. 1990. Quotations as demonstrations. Language 66, no. 4: 764–805. http://www.jstor.org/stable/414729.

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2007. Style: language variation and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coupland, Nikolas, and Janus Mortensen. 2017. Style as a unifying perspective for the sociolinguistics of talking media. In Style, mediation, and change: sociolinguistic perspectives on talking media, ed. J. Mortensen, N. Coupland, and J. Thøgersen, 251–61. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deumert, Ana. 2014. Sociolinguistics and mobile communication. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Du Bois, John W. 2007. The stance triangle. In Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction, ed. R. Englebretson, 139–82. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Du Bois, John W., and Elise Kärkkäinen. 2012. Taking a stance on emotion: Affect, sequence, and intersubjectivity in dialogic interaction. Text and Talk 32, no. 4: 433–51. doi:10.1515/text-2012-0021.

- Englebretson, Robert, ed. 2007. Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 2016. Some debts can never be repaid: The archaeo-politics of the crisis. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 34, no. 2: 227–64. doi:10.1353/mgs.2016.0026.

- Haviland, John. 2005. Whorish old man and one (animal) gentleman: The intertextual construction of enemies and selves. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1: 81–94. doi:10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.81.

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel. 2016. Sociolinguistic styles. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa, eds. 2012. Style shifting in public: New perspectives on stylistic variation. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Hodges, Adam. 2015. Intertextuality in discourse. In The handbook of discourse analysis, 2nd ed., ed. D. Tannen, H.E. Hamilton, and D. Schiffrin, 42–60. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Irvine, J.T. 1996. Language and community: Introduction. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 6, no. 2: 123–25. doi:10.1525/jlin.1996.6.2.123.

- Jaffe, Alexandra, ed. 2009a. Stance: sociolinguistic perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jaffe, Alexandra. 2009b. Introduction. The sociolinguistics of stance. In Stance: sociolinguistic perspectives, ed. A. Jaffe, 3–28. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2009. Taking an elitist stance: ideology and the discursive production of social distinction. In Stance: sociolinguistic perspectives, ed. Alexandra Jaffe, 195–226. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Johnstone, Barbara. 1996. The linguistic individual: self-expression in language and linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2000. The individual voice in language. Annual Review of Anthropology 29: 405–24.

- Karakatsanis, Neovi, and Jonathan Swarts. 2007. Attitudes toward the xeno: Greece in comparative perspective. Mediterranean Quarterly: A Journal of Global Issues 18, no. 1: 113–34. doi:10.1215/10474552-2006-037.

- Kienpointner, Michael. 2013. Strategic maneuvering in the political rhetoric of Barack Obama. Journal of Language and Politics 12, no. 3: 357–77. doi:10.1075/jlp.12.3.03kie.

- Kuo, Sai-Hua. 2001. Reported speech in Chinese political discourse. Discourse Studies 3, no. 2: 181–202. doi:10.1177/1461445601003002002.

- Labov, William. [1966] 2006. The social stratification of English in New York city, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lassen, Inger. 2016. Discourse trajectories in a nexus of genres. Discourse Studies 18, no. 4: 409–29. doi:10.1177/1461445616647880.

- Lempert, Michael. 2011. Barack Obama, being sharp: Indexical order in the pragmatics of precision-grip gesture. Gesture 11, no. 3: 241–70. doi:10.1075/gest.11.3.01lem.

- Makoni, Busi. 2019. Strategic language crossing as self-styling: the case of black African immigrants in South Africa. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 14, no. 4: 301–18. doi:10.1080/17447143.2019.1581207.

- Nicola, Nassira. 2010. Black face, white voice: Rush Limbaugh and the message of race. Journal of Language and Politics 9, no. 2: 281–309. doi:10.1075/jlp.9.2.06nic.

- Partington, Allan, and Charlotte Taylor. 2018. The language of persuasion in politics. An introduction. London: Routledge.

- Phillips, James A. 1985. US-Greece relations: an agonizing reappraisal. Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/europe/report/us-greece-relations-agonizing-reappraisal.

- Redmond, Sean. 2010. Avatar Obama in the age of liquid celebrity. Celebrity Studies 1, no. 1: 81–95. doi:10.1080/19392390903519081.

- Reyes, Antonio. 2014. Bush, Obama: (in)formality as persuasion in political discourse. Journal of Language and Politics 13, no. 3: 538–62. doi:10.1075/jlp.13.3.

- Rickford, John R., and Penelope Eckert. 2001. Introduction. In Style and sociolinguistic variation, ed. P. Eckert and J.R. Rickford, 1–18. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Schilling-Estes, Natalie. 2004. Investigating stylistic variation. In The handbook of language variation and change, ed. J.K. Chambers, P. Trudgill, and N. Schilling-Estes, 375–401. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Schugurnesky, Daniel. 2000. Citizenship learning and democratic engagement: political capital revisited. Adult Education Research Conference. http://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2000/papers/82.

- Shayegh, Kamal. 2012. Modality in political discourses of Barack Obama and Martin Luther King. Trends in Advanced Science and Engineering 3, no. 1: 2–8.

- Shayegh, Kamal, and Nesa Nabifar. 2012. Power in political discourse of Barack Obama. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research 2, no. 4: 3481–91.

- Sheveleva, Alla. 2012. Lingo-rhetorical and socio-pragmatic peculiarities in political speeches by Barack Obama. Intercultural Communication Studies 21, no. 3: 53–62. https://web.uri.edu/iaics/files/05Sheveleva.pdf.

- Shi-xu. 2012. Why do cultural discourse studies? Towards a culturally conscious and critical approach to human discourses. Critical Arts 26, no. 4: 484–503. doi:10.1080/02560046.2012.723814.

- Shi-xu. 2016. Cultural discourse studies through the Journal of Multicultural Discourses: 10 years on. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 11, no. 1: 1–8. doi:10.1080/17447143.2016.1150936.

- Shoaps, Robin A. 1999. The many voices of Rush Limbaugh: The use of transposition in constructing a rhetoric of common sense. Text-Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 19, no. 3: 399–437. doi:10.1515/text.1.1999.19.3.399.

- Tannen, Deborah. 2007. Talking voices: Repetition, dialogue, and imagery in conversational discourse. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Theodoropoulou, Irene. 2014. Sociolinguistics of style and social class in contemporary Athens. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Theodoropoulou, Irene. 2016. Mediatized Vernacularization: On the Structure, Entextualization and Resemiotization of Varoufakiology. Discourse, Context and Media 14: 28–39.

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 2012. Discourse and ideology. In Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction, ed. T.A. van Dijk, 379–407. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Wilce, James M. 2005. Traditional laments and postmodern regrets: The circulation of discourse in metacultural context. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1: 60–71. doi:10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.60.