ABSTRACT

This paper highlights the erasures of normal-languaging and normal-diversities that mark the contemporary human condition. Its aim is to make visible North-centric assumptions regarding the nature of language by asking what, when, why and where language exists and how it plays out in global-local, analogue-digital timespaces. In particular, the study presented in this paper troubles the interrelated ‘webs-of-understandings’ regarding language, identity and culture that are embedded in both traditional concepts and neologisms. It illuminates the looped taken-for-grantedness of established and emerging discourses in the Social Sciences and Humanities. Drawing attention to boundary-markings in scholars languaging that have become naturalized, the paper critically appraises how conceptual epistemic hegemonies continue to flourish across northern-southern places-spaces. It thus, also discusses the relevance of such questions in doing research itself. Inspired by an overarching reflection on various ‘turns’ (like the multilingual-, boundary – and mobility-turns), this paper calls for moving from North-centric knowledge regimes to engaging analytically with global-centric epistemologies where gazing from a mobile-loitering stance is key. This means that this paper poses uncomfortable and revised analytical–methodological questions that potentially destabilize existing global/universal understandings related to language, identity and culture.

Intercultural communication may often focus on modest reforms calling for the inclusion of marginalized knowledges, rather than on fundamental institutional changes that can eradicate the forces that produce marginalization. (R’boul Citation2022, 1)

Operationalizing SWaSP tenets, this paper aims to disturb explicit mainstream understandings (in Northern spaces-places like Sweden, other parts of west-Europe, USA, etc.) related specifically to the nature of language, identity and culture.Footnote2 Secondly, it aims to transcend binaries and instead explore alternate ways-with-words, ways-of-being, ways-of-doing and ways-of-knowing. It does this as a third alternative (SWaSP) position that transcends a middle compromise stance: rather than from the global-North or from the global-South, a mobile-loitering gaze is understood as contributing to global-centric dialogues.

The need for a gaze that illuminates complexities, i.e. the wilderness of human existence, is illustrated through two examples in Section 1. Section 2 indexes the importance of making visible scholars’ gazing in mainstream Northern contexts, including its relevance in research. Section 3 explicitly troubles what such taken-for-granted gazing means for language, identity and culture. The last two sections explore established North-centric knowledge-regimes in mainstream scholarship through a continuing mobile-loitering gaze, inviting attention to global-centric alternative ways-of-knowing/being/doing.

1. Introducing an interrogating gaze in the wilderness

Terms like ‘global’ and ‘international’ garner 9,360 million and 10,740 million hits respectively in the category ‘all’ on the search engine google in mid-2022. Of these 841 million and 1,070 million respectively fall under the category ‘news’. While viewing the popularity of concepts and their circulations in digital spaces is mediated through our contemporary computing lives, meaning circulations in and across digital-analogue spaces is contingent upon the uptake, shifts and changes in and through named-languagesFootnote3 across planet earth. Thus, while the whimsical google search of the concept ‘global’ at my desktop in Sweden resulted in items in at least two named-languages – EnglishFootnote4 and Swedish, this was not the case with the search term ‘international’ (its spelling in English differs from Swedish).Footnote5

Noting cultural patterns around us is what a researcher’s purposeful (or whimsical) gaze attempts to map whether directed at dimensions of human behavior or natural phenomenon. Such gazing – whether on specific concepts at specific moments or at complexities in and across digital-analogue spaces – is (at best) analytically steered. It is never neutral. Given that human life and existence are complex, studying complexities requires dedicated ways of making sense of life, through what we call data. Doing ‘naturalistic inquiry’, for instance, challenged previous paradigms that were marked by taken-for-granted framings wherein controlling variables purportedly provided ‘better’ results (Erlandson et al. Citation1993; Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Acknowledging complexities, messiness and the entanglements of epistemology, analysis and methodology, naturalistic inquiry draws attention to ‘ethnography as mindwork, not merely a set of techniques for looking but … a particular way of seeing’ (Wolcott Citation1999, 44). Doing naturalistic inquiry also necessitates loitering. Akin to but different from what Geertz (Citation1998) calls ‘deep hanging out’, loitering connects with a transmethods stance that interrogates programmatic ideas regarding data and methods. It consists of just being in spaces, without purpose, with a curious mind. A privileged activity, loitering metaphorically draws attention to casual hanging around without implicit or explicit reason. It potentially enables becoming privy to happenings in analogue-digital spaces and constitutes an important way to illuminate cultural patterns in and across settings conceptualized as global, (inter)national, regional and local.

Made possible through a taken-for-granted access, physical loitering is ‘a fundamental act of claiming public space and ultimately, a more inclusive citizenship’ (Phadke, Khan, and Ranade Citation2011, xiii). In contrast, entangled conceptual-methodological loitering calls attention to the creative chance happenings a researcher can become privy to and thereby engage with human complexities. Loitering is a pre-condition wherein ethnography as mindwork is salient. Being allowed to loiter in digital-analogue communities for doing mindwork is however, as ethnographers recognize, not an easy mission. Key here is drawing on the creative human capacity of taking note of things whereby mindwork needs augmention with ethnography as loitering.

Problematizing the key notion of language can be done through continuing loitering and gazing at other terms. Some theoretical framings explicitly question the ways in which language, identity and culture are thingified, imagined as existing outside individuals. As dimensions of meaning-making, language can fruitfully be conceptualized as a verb – languaging, and human-beings as languagers, rather than users of languages.Footnote6 Similarly, culture and music become disentangled from their thinginess when seen as culturing and musicing/musiking, the very doings that makes us human. I first highlight circulations of naming-practices related to terms that mark the human experience of having eaten, before loitering and gazing at vocabularies that designate imagined places-spaces on planet earth.

While the concept ‘hunger’ is an experience that humans and communities may voluntarily subject themselves to (through shorter and longer fasting cycles), involuntary hunger and starvation have, and continue to be, a reality for millions. The mass-spread hunger and starvation between 1867 and 1869 in Sweden are chronicled as leading to misery, death and the start of the territory’s largest mass-emigration, including the very formation of the country (Västerbro Citation2018). While the latter part of the twentieth century witnessed a greater awareness of the human condition across the planet – not least due to mass-media and digital access, the continuing hegemonic disproportionate (mis)use, including (mis)management of natural resources and produce, have been blamed for food maldistribution and inaccessible sustenance for-all. Economists Dreze and Sen (Citation2004) discuss hunger as a human-made situation, an ‘entitlement crisis’, instead of a consequence of natural catastrophes.

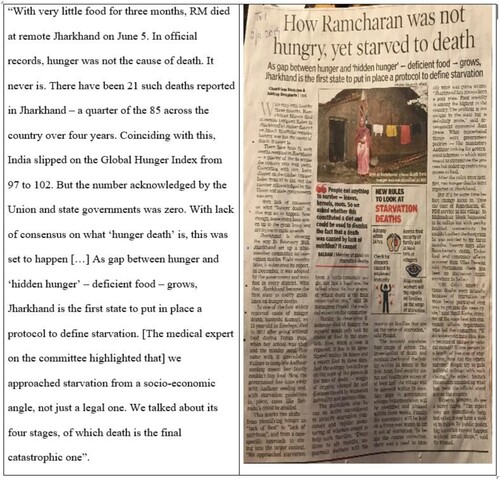

While widespread hunger and malnutrition continue to shape life and death, circulating discourses that monitor ‘hunger and starvation’ constitute illustrations of what naming-practices can do and how they shape our understandings related to the living and the dying. displays a Times of India report wherein identification markers of hunger and starvation point, among other issues, to the apathy we find ourselves in when attempts are made to fit this despicable issue into stages ‘of which death is the final catastrophic one’. Established vocabularies at best hold us prisoners in conceptual realms, and at worst shape the meanings of dying on account of ‘hidden hunger’. While experts and governments fine-tune what distinguishes involuntary hunger from starvation (where the final stage is death), a person’s demise is reported within a definition of starvation, even though he was not hungry.

Figure 1. Identifying hunger and starvation: lack of ‘nutrition’ or ‘food’ (Times of India, 2 November 2019).

While officials, politicians, journalists, citizens, and researchers, discuss ways to identify, define, monitor, fight, experiment with,Footnote7 and eradicate hunger and starvation, humans continue to die because of a ‘lack of nutrition, rather than not having access to food’. The hungry, starving cease to exist, they pass out of time. Given the global/international nature of such experiences across timespaces, in what ways do these naming-practices contribute to illuminating the condition of the living and the dying? What, we can ask, is the role of languaging here? Cognizant of being trapped in the very cultural tool that I am channeling our attention to – i.e. language, the mindwork called for requires loitering creatively and compassionately, thus, cultivating a mobile-loitering gaze that attends to complexities of the human condition. If mainstream language scholarship abdicates such a gaze, then the very purpose and role of research gets jeopardized.

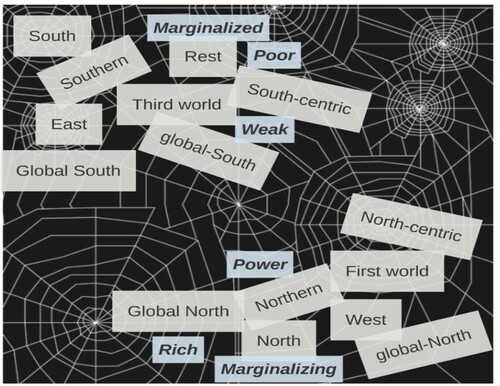

My second example turns our gaze towards naming-practices that point to places-spaces on planet earth. Terminological and analytical issues related to naming specific places-spaces as the East was surmised in relation to Europe. The term East (the Orient) led to the creation of the West (the Occident). These regions morphed into the South and North, Southern/Northern, global-South/global-North, West and the Rest, etc. Such naming-practices and shifts vis-à-vis place-space, constitute metaphors related to the marginalized and the marginalizers. They build on looped taken-for-granted webs-of-understandings that need troubling: South/East of Europe on a spherical planet? Furthermore, mobilities mediated by digitalization more clearly shake conceptualizations of directionality based upon the earth’s magnetic field.Footnote8 While East–West, North–South and other terminological binaries are imagined, they nevertheless constitute potent circulating connected-discourses or webs-of-understandings that have gained currency inside and outside scholarship (). These binaries map onto the haves and the have-nots, the rich and the poor, those who are in positions to marginalize others (knowingly or unknowingly) and those who involuntarily experience hunger and other marginalizations.

Figure 2. Webs-of-understandings. South(ern), North(ern), global-South, global-North.

These constitute illustrations of what a mobile-loitering gaze implies in the wilderness of human existence, including researching the human condition. The next section highlights the importance of making scholars’ gazing visible and the meaning of a mobile-loitering gaze for contemporary scholarly issues.

2. A note on gazing and noting a mobile-loitering gaze

Democratic-equity and quality issues constitute dimensions of knowledge circulations enabled through ‘international’ publications. Loitering in the corridors of academic publishing, enables interrogating some of its taken-for-granted premises and naturalizations. It raises uncomfortable questions related to who decides and what makes a journal or publication international. What is the nature of referencing patterns, thematic foci, named-languages of publications, etc. that can confer the label ‘global’ and/or international to a journal? What epistemologies are being made (in)visible, what continents dominate the global/international publishing landscape – in terms of who and what is referenced, but also who gets published and where and in which named-languages this is accomplished? Key here is the paucity of global epistemologies in what is received knowledge – the caveat being that it is the West-North-First world that are assumed in the labels global and international.

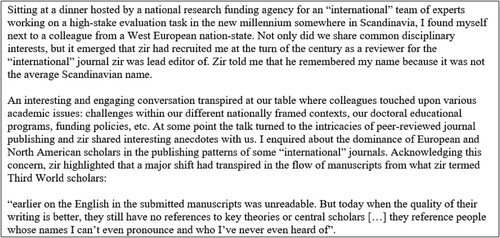

Vignette 1. The nature of gaze: from where and at what.

has shaped my teaching and mentoring work in the nation-state where I live and work, a country that suffers from colonial amnesia (Hübinette, Wickström, and Samuelsson Citation2022); it has also shaped my understandings and the agendas I attempt to create in my engagements in the territories colonized by European powers. Furthermore, experiences from different places-spaces, including the mobility that is called for to access, crisscross and work across planet earth creates openings and dissonance. One opening potentially enabled through mobility is engaging with and making relevant epistemological framings that go under place-space binary-marked concepts explicated in . These are relevant for cultivating epistemologies related to imaginaries of mobility, language, identity and culture. In the remainder of this and the next section, we will loiter and gaze at issues of mobility, language, identity and culture. Crisscrossing and working across territories calls for a brief reflection on the very term nation-state (or country). These emerged because of historical shifts that left behind a world of colonial empires: from 51 in 1945 to 206 currently.Footnote9

Although empires of other sorts arguably endure and exert continued influence on global affairs, they are obliged to operate with an international system that privileges the nation-state, with its claim to territorial integrity and sovereignty, along with the premise that sovereignty derives in some fashion from ‘the people.’ What this modern international system has deemed unacceptable is colonialism: the imposition by a foreign power of direct rule over another people. (Kennedy Citation2016, 1; see also Bhambra Citation2007)

It is the issue of noting boundary creations, their flux and countering colonial gazing that is key in research. This calls for a two-fold effort. First, drawing attention and making visible outcomes of boundary creations, their fluid nature and the gaze a scholar brings to conceptual issues. Second, how this visibility can be managed in the scholarly pursuit of knowledge building. Recognizing the imagined and in-flux nature of nation-states calls attention to issues of using them as units-of-analysis when scholars focus on language, identity and culture. While people and communities have always moved across physical places, contemporary human existence is mobile in newer ways. In addition to explosively larger numbers of people who moveFootnote11 across places-spaces, digitalization has opened new ways-of-knowing/being/doing in different spaces sans physical movement.Footnote12 Turning an interrogating mobile-loitering gaze across time and within nation-states provides evidence of the normal nature of human migrations and mobilities. However, human mobility has become conceptualized within the Social Sciences and Humanities scholarship and the mass-media (in particular in west-European places-spaces in the new millennium) in terms of heightened (super)diversity. Loitering in the wilderness of such circulating discourses disturbs the mobility-related neologisms that have become ‘academic slogans’ (Pavlenko Citation2019). Thus, instead of attempting to engage with the hegemonic circulating discourses of purportedly new human and cultural diversities in the twenty-first century, loitering in nation-states and territories that were colonized (and that have seen extensive older and newer cross-mobilities and internal-mobilities) enables directing the scholarly gaze towards issues of normal-diversities. The point is that attending to what is being conceived as contemporary (super)diversity in North-centric places-spaces of west-Europe requires explorations of normal-diversities across time in South-centric spaces.Footnote13

Being mobile on planet earth is an enriching enterprise for a scholar curious about epistemologies and ontologies. A perpetual mobility across timespaces – physically and digitally living and working across nation-states – is however also risky since such an existence does not foster a stable given natural point of departure vis-à-vis knowledge-regimes, identity-positionalities, languaging, cultural practices and human mobility itself.

Such recurring mobility also emerges when a scholar works within different research domains and disciplinary areas: what constitutes given points of departure or data in one is far from the given in another. Such risks of not having taken-for-granted points of departure notwithstanding, the enriching (at least in the long term) nature of such mobility can be accrued through the fostering of an understanding of the many-ways-with-words, the plurality of ways-of-seeing and ways-of-being in the epistemological enterprise itself. Relevant here is that a scholar (and a human being) always gazes from some position. There is a gaze from which the East/South and West/North emerge and are naturalized and re-actualized. There is a gaze from specific (mono)disciplinary academic spaces, from cross/inter/multi/trans-disciplinary spaces, etc. There is also a gaze from a mobile position of being on the move: a mobile-loitering gaze. Such alternative (SWaSP) gazing from mobile-loitering spaces can potentially break hegemonies of rooted traditions of gazing from given naturalized places-spaces.

Calling attention to sticky issues, illustrates both the taken-for-grantedness with regards to scholarly hegemonies and a need for disturbing naturalizations regarding publishing routines: for instance, how diversity is named and by whom, what is mainstream wisdom and referencing patterns, etc. A mobile-loitering gaze on this case also illustrates the need for making visible the continuing paucity of global-North/South dialogues in different scholarly domains. Aligned with postcolonial/decolonial/southern perspectives that highlight important hegemonies and injustices across the planet, alternative (SWaSP) framings call attention to uncomfortable revised analytical issues that trouble naturalized North-centric gazing vis-a-vis epistemologies and ontologies. While postcolonial/decolonial/southern framings have existed in some scholarly domains for a few decades, they appear to live a parallel or peripheral existence to the mainstream agendas of those domains. My mobile-loitering’s in the next section illustrates this issue through a focus on the scholarship in the Language Sciences/Studies.

3. Gazing from where? Example language scholarship

The language scholarship emerging from geopolitical West-North-First world places-spaces is recognizing the restricted way language was (and is) treated in its own geopolitical contexts, thus changing the very nature of this scholarship.Footnote14 Increasing numbers of special issues since 2015 and conferences since 2018 focusing on the non-bounded nature of language can also be noted in North-centric spaces.Footnote15 While this shift is becoming visible in sub-fields like Applied Linguistics, Bi/Multilingualism, Educational Linguistics, Linguistic Anthropology, Sociolinguistics, it continues to build on its own epistemological, ontological and methodological toolkits through old/new vocabularies.Footnote16

Calling attention to the normalcy of deploying more than one named-language and the fluidity of such languaging through diversifying neologisms has taken (and to a large extent continues to take) place in the West-North-First world; furthermore, most scholars who engage with these ideas are born in and/or are educated in West-North-First places-spaces and have (at best) conducted their fieldwork in East-South-Rest places-spaces. This means that the gaze of scholars, situated in places-spaces where imaginaries of monolingualism continue to thrive, is on a phenomenon that is the norm in the East-South-Rest of the planet. Introducing ‘the Multilingual Turn’ in the edited volume with the same title, May (Citation2014, 2) suggests that despite growing awareness regarding ‘the ongoing hegemony of monolingualism … , we have not wholly escaped from the established terminology associated with it – most notably, the still ubiquitous terms of “native speaker” and, of course, “language” itself’. May makes another critical observation: the volume chapters are ‘still focused predominantly on Western contexts, on ongoing legacy of the hegemony of Western applied linguistics’ (May Citation2014). Another illustration of the nature of this gaze, and in particular from where and at what, can be seen in the 2016 Douglas Fir Group article published in The Modern Language Journal. The articles’ 15 authors, situated in North America, are cognizant of their hegemonic gaze. They highlight that while their views are

enriched by the diverse parts of the world in which each one of us has worked, done research, and collaborated with others … we must recognize that our affiliation with institutions in only two parts of the world, the United States and Canada (SIC), bound our intellectual views. (2016, 20)

The gaze of scholars from the East-South-Rest who language in multiple ‘parent-languages’ and who are situated in spaces where the use of multiple named-languages is banal normalcy are rarely upfronted; North-centric scholars ‘can’t even pronounce’ () the names of scholars from the East-South-Rest; their peripheral writings are published in peripheral journals. The Douglas Fir Group article became a ‘mainstream reference’, was published in a ‘mainstream reputable journal’, in a status ‘mainstream language’. While it made significant contributions to the language scholarship, it illustrates the hegemony of a North-centric gaze.

Constituting meaning-making enterprises, mainstream references, mainstream publishing areas, the naturalized role of English in a global context, etc. showcase specific epistemologies that silence alternative knowledge-regimes. Such hegemonies related to knowledge-regimes, circulations and (re)productions, including publication practices, need interrogation and de-naturalization. Why are dialogues regarding the fluid non-bounded phenomena called language primarily – if not totally – taking place in some places-spaces? From whose gaze, from what positionalities is such knowledge (re)production taking place? The recent re-conceptualization regarding the key term language notwithstanding, the importantpoint is that this shift is taking place in academic and professional places-spaces of the West-North-First world.

Naming-practices that call attention to language, human beings’ key cultural tool, including people’s deployment of more than one named-language is not a neutral endeavor either. Use of boundary-marking older concepts (like bi/multilingualism, home language, mother-tongue, etc.) and neologisms that point to this behavior, including the people behaving in this manner, constitute a meaning-creating enterprise that scholars are complicit in. Labels are never neutral, and they are never outside the cultural tool of language (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980).

Circulations of terms related to language are, furthermore, linked to other conceptual webs-of-understandings that work to mutually reinforce one another: peoples roots, their cultures, their origins, peoples’ home-countries, etc. Unlike rooted vegetation, human beings do not have roots – humans (like other animals) have always been mobile: through their physical capabilities of moving around and ontologically of being in a world where mobility across timespaces characterizes the homo sapiens and their descendants (see Section 1). Origin stories, framed in cultural and religious narratives notwithstanding, highlight specific characteristics (eye shape, skin color, functionality, etc.) or place-space (nation-states, mountain regions, river sides, etc.) that support the demarcation of one group from another. Similarly, an individual or a groups (original) home-country (labeled native-place) creates a boundary to group-in people, separating one community from another. The contemporary revival of circulating discourses of genetics and race, linked to the construct of nation-states and groups, needs critical interrogation from a mobile-loitering gaze. Here the scholarly domains of language, identity and culture are key. The birth places-spaces of the 2019 Nobel prize winners in Economics (see footnote 7) can serve to illustrate this: situating the laureates in their USA academic institutions aside, presenting their birth cities and nation-states of ‘origin’ in a press-release is arbitrary. Does the Nobel Academy present such information as a matter of routine, and if so, is the rationale to,

highlight brain-drain from Asia and Europe to the USA?

the global/international nature of research?

The essentialism inherent in ideas related to roots, culture, origins, home/native-place, race, like the use of East/South and West/North to mark places-spaces, continues without analytical engagement. A mobile-loitering gaze calls attention to such essentialism embedded innocently in contemporary mainstream circulating discourses.

This discussion calls for making visible essentialism at a more overarching level by drawing attention to turn-positions such as the multilingual-turn (May Citation2014), the boundary-turn (Bagga-Gupta Citation2013), the mobility-turn (Landri and Neuman Citation2014), etc. Such a turn-on-turn reflexivity has the potential to

illuminate the naturalized boundaries and the gaze researchers (and non-academicians) bring to different issues, and

how such visibility can mobilize alternative ways-of-knowing/being/doing.

This constitutes the agenda in the rest of this paper.

4. From established knowledge-regimes…

Human languaging is complex irrespective of how many named-languages (including named-modalities and other semiotic resources) people engage with in mundane life and irrespective of whether such behavior plays out in analogue, digital or entangled analog–digital places-spaces. Recognizing and giving this complexity visibility is complicated – for the researcher, not for languagers interacting with others and with cultural and physical tools. Simplifying the complexity of human languaging, if anything creates epistemological, and ontological problems in the scholarship (Law Citation2004).

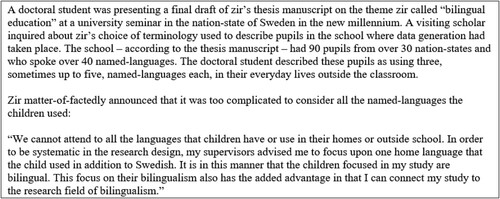

The slice of academic life presented in illustrates established naturalized knowledge-regimes, including the monolingual gaze of North-centric scholars and scholarship. Fitting multiple named-language usage and languagers with experiences and knowledge of multiple named-languages into a bilingual model is seen as the easy-way out under the cloak of research systematicity, including the intent of connecting such research to the ‘international’ field of bilingualism. This field is marked by nomenclature that labels people’s behavior in specific ways. An underlying point of departure that frames such North-centric gazing is the mainstream concepts regarding languagers who deploy multiple named-language/s. A critical query for approaching the wilderness of such languaging through mobile-loitering gazing is asking, for whom is this task complicated? For North-centric doctoral students, their supervisors and for particular academic communities? Languaging where multiple named-languages (including multiple named-modalities and other semiotic resources) are deployed in meaning-making is (for the most) not an issue for languagers participating in social practices of which they are (peripheral or central) members.

Vignette 2. Squeezing in multiple languages into a bilingual model.

The doctoral students’ and zirs’ academic community’s working strategies are illustrative of the pragmatics of conducting language scholarship in North-centric places-spaces and of the problems that such established knowledge-regimes pose for scientific inquiry more broadly. Peoples complex languaging repertoires need acknowledgement and this calls for a mobile-loitering gaze that transcends established knowledge-regimes. Problems that researchers or specific research domains face need to be addressed analytically and methodologically, rather than through reductionist circulating discourses. This is an epistemological issue, not an ontological problem that subjects face.

While North-centric scholarship has become aware of the need to dislodge a monolingual bias in search of firmer ground (see above), the issue at stake is that unless there is explicit recognition of a scholar’s gazing positionings and the never-ending partiality of all knowledge-regimes, merely replacing older concepts with neologisms is a doomed short-term enterprise. Dialoguing with ways-of-being-with-words from East/South/Rest places-spaces, where recognition is accorded to a diversity of human experiences and the deployment of multiple named-languages constitutes a taken-for-granted stance, becomes a fundamental game-changer here. Thus, understanding that individuals have many ‘mother-tongues’ or ‘parent-languages’ (as is the norm in many communities across both what is recognized as the South and as the North) dislodges North-centric equations wherein a child’s languaging repertoires continue to be reduced to one or two named-languages to fit the child’s behavior into a bilingual model.

(Re)creating demarcations between named-languages, prefixed (bi/multi/pluri/trans) established or new vocabularies are also contingent upon framings that are North-centric. Troubling this does not call for replacing present hegemonies by a ready-made gaze that is pre-existent in South/Southern places-spaces: it is making visible the North-centric taken-for-granted gaze that is key. Secondly, this naturalized gaze can be disturbed through a naturalistic inquiry agenda (see above) enabling a re-viewing and re-articulation of existent circulating discourses. This stance also calls attention to the lack of dialoging between North-centric and South-centric scholars. This is not an uncomplicated issue given the colonial hegemonies of circulating discourses established across timespaces. Thus, for instance, the validity conferred to knowledge-regimes of west/north-European and North American places-spaces, and the established pattern of unilateral circulation of literature, theories and concepts in hegemonic named-languages from North/West/First to South/East/Rest of the planet needs acknowledgement; this, as illustrated, draws attention to the naturalized ways of referencing, the languaging of mainstream scholarship wherein English dominates, etc. A mobile-loitering gaze plays a critical role here to enable shifts from such established knowledge-regimes towards non-binary global-centric alternative ways-of-knowing/being/doing.

5. … towards global-centric (alternative) ways-of-knowing/being/doing

The move from monolingual norms to a stance wherein bi/multi/pluri/trans-lingualism or bi/multi/pluri/trans-languaging is recognized as relevant by scholars situated in North-centric places-spaces is significant. While scholars are drawing attention to the non-bounded, non-reified nature of what is called language,Footnote17 the whos, the wheres and the ways in which this shift has evolved needs closer scrutiny. Pointing to the terminological creativity of this ongoing project, May suggests that several ironies are part of ‘this sudden “turn” towards multilingualism’ (Citation2014, 2). For instance, a

lack of historicity and not a little ethnocentrism [given that] scholars from beyond the West have long argued for just such an examination of multilingualism, albeit more broadly than in just urban contexts, and a related contesting of the monolingual norms that still underpin the study of language acquisition and use (the distinction itself reflecting this). (May Citation2014)

Another irony that May raises relates to the ‘largely untouched, uninterested, and unperturbed’ life of scholarly domains like SLA, TESOL that ‘continue to treat the acquisition of an additional language (most often, English) as an ideally hermetic process uncontaminated by knowledge and use of one’s other languages’ (May Citation2014). A final issue raised concerns the disregard for these very developments in the language scholarship ‘because it remains corralled within a “critical applied linguistics” with which they seldom engage (or, when they do, take seriously)’ (May Citation2014). Thus, it is some – not all – areas of language scholarship in North-centric places-spaces that are undergoing a revitalization process.

Making visible and troubling North-centric assumptions regarding this thing called language, needs to become a central element of a revitalization endeavor. Highlighting the skewed nature of what is purported as international and global is key, as is pointing to the need for understanding the nature of normal-languaging and normal-diversities through multiversal (compare universal), non-hegemonic global-centric alternative lenses. Such endeavors constitute dimensions of alternative (for instance, SWaSP) framings. Going beyond a de facto restricted gaze that has been naturalized as global/international both in terms of universal epistemologies, ontologies and methodologies needs to open up to multiversal ways-of-seeing/knowing/being-with-words. Current scenarios of marginalization and erasure need attention, first by highlighting naturalizations, and thereafter by employing a global-centric stance.

While postcolonial/decolonial/southern framings attempt to trace the places-spaces where hegemonies originate and towards what places-spaces they move (either historically or in contemporary times), an alternative (SWaSP) mobile-loitering gaze shakes illusions regarding the places-spaces of hegemonies and their unidirectional movements. It recognizes that marginalized and marginalizing peoples, communities exist across planet earth. Furthermore, marginalized and marginalizing discourses and terminologies circulate across analogue-digital places-spaces. It is therefore important to recognize that a South exists in the North and a North exists in the South. The flows of discourses as well as the entanglements of these places-spaces also need upfronting. The intersectional entanglements of identity-positionings in peripheries and centers constitute both a dynamic and a shifting mobile predicament. Identities cannot be bound to physical place or an embodied personhood or as traditional categories.

Naming-practices that give meaning to language, identity and culture furthermore hold us prisoners in conceptual framings; unlike hunger and starvation (), these concepts may not lead to death, but they are consequential. The multiply-layered violence perpetuated through the revival of circulating discourses that link genetics and race with communities and nation-states constitutes an illuminating example wherein language and cultural proficiency are used as yardsticks for awarding citizenship rights. Such ‘weaponization of language’ (Burke, Thapliyal, and Baker Citation2018, 84) points to the naturalized linkage of political belonging with language and cultural proficiency, indicating not just the relevance of troubling such circulating discourses, but also the need to make visible the multiple named-language norm of communities across planet earth. Doing this requires acknowledging the need for a North–South dialogue, i.e. the need for multiple gazing positionalities in research, rather than the replacement of North-centric epistemologies with something else. Alternative knowledge-regimes point to issues regarding naming-practices in North-centric mainstream epistemologies, contemporary hegemonic publication regimes, including referencing patterns and monolingual languages of scholarship, etc. They also call for the creation of dialogical spaces wherein Southern-centric ideas, themes, traditions, naming-practices are enabled.

Mainstream understandings of language are framed through ‘single grand stories’ (Bagga-Gupta Citation2018). These are reinforced through scholarship that continues to (re)create essentialist boundaries explicitly or implicitly between territories, named-cultures, named-languages and named-identity categories. For instance, scholarship that focuses upon mother-tongue, foreign languages, second language, bilingualism, etc. and named-languages like Swedish, Swedish Sign Language, English, British Sign Language, American Sign Language, Hindi, Indian Sign Language, etc., but also (imagined) named-languages like Swedish as a Second Language, English as a Second Language, English as an Additional Language, English as a global language, English as a lingua franca, etc., become linked to a range of named-identity categories and a ‘general’ naturalized understanding of learning in educational settings (Bagga-Gupta Citation2023a, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Such named-languages exist as areas of research and expertise that are ingrained in nation-state policies.

Recent circulating discourses regarding language fluidity and meaning-making notwithstanding, languaging and meaning-making continue to be conceptualized in terms of demarcated named-language categories. Hegemonic mainstream gazing continues to conceptualize identity and culture in essentialist terms through the organization of language teaching, learning and research. Calling attention to ethnic backgrounds, race, roots, origins and nation-state allegiances thus get connected to naturalized understandings of first, second, third named-languages, mother-tongues and home languages in the singular. Such categorizations and arrangements are not innocuous and need troubling in radically new ways. It is here that the language and culture scholarship needs revitalization through a global-centric stance if it is to meaningfully engage with the contemporary human condition across planet earth.

Troubling circulating discourses from a global-centric mobile-loitering gaze has consequences for transcending methodological-naivety and reductionist tendencies in the study of language. Instead of fitting the languaging of languagers in pre-conceived models, a mobile-loitering gaze enables illuminating human meaning-making in situ in the wild, including ways-of-thinking that are sensitive to peoples’ ways-of-knowing/being/doing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sangeeta Bagga-Gupta

Sangeeta Bagga-Gupta is University Full Professor in Education with a multidisciplinary background at Jönköping University, Sweden. She is the Scientific Leader of the research environment CCD (Communication, Culture, Diversity), that she established at the end of the 1990s at Örebro University, Sweden. Her research is marked by an explicit multidisciplinary/multi-thematic perspective that has a strong international anchoring. At an overarching level, her research contributes to areas such as communication/languaging, identity positionalities, culture, digitalization and learning from (n)ethnographic approaches at micro-, meso- and macro-scales from sociocultural and decolonial theories. She is multilingual in spoken, written and signed modalities.

Notes

1 For more on SWaSP see Bagga-Gupta (Citation2023a, Citation2023b, Citation2022a, Citation2022b), Bagga-Gupta and Carneiro (Citation2021), Bagga-Gupta and Messina Dahlberg (Citation2021).

2 This relates to the important work developing in the Cultural Discourse Studies tradition that insists on a holistic and cultural view of all human communication/discourse (Shi-xu Citation2022, Citation2016).

3 The digital resource Ethnologue lists 7151 ‘recognized languages’ in mid-2022. Its disclaimer is key here: this ‘number is constantly in flux, because we’re learning more about the world’s languages every day. … languages themselves are in flux. They’re living and dynamic, spoken by communities whose lives are shaped by our rapidly changing world’ (https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages). Transcending issues of language recognition, mainstream North-centric Language Sciences/Studies acknowledge problems of counting languages. The term ‘named-language’ draws attention to the fallacy of demarcating ‘a’ language from ‘an’other language, including differentiating ‘a’ language from other semiotic resources in peoples meaning-making languaging enterprise.

4 Let us temporarily disregard that English is not ‘one’, but ‘many’ named-languages.

5 The Swedish term ‘internationell’ garnered almost 17 million hits.

6 See writings by Lachhman Khubchandani, Per Linell, Ragnar Rommetveit.

7 The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to scholars working in the USA, two at MIT and one at Harvard University, ‘for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty’ (https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2019/press-release/, 15/5 2022). In its short official press-release, the Nobel Academy highlights where these scholars were born: Mumbai, India, Paris, France and New York, USA.

8 Not least since our earth is spinning around a sun in the solar system located in the Milky Way in the known universe, i.e., East/South, West/North are ideological constructions.

9 The United Nation lists 206 members of which 193 are ‘member states’ (i.e., nation-states, https://web.archive.org/web/20131230101646/http://www.un.org/en/members/index.shtml#, 15/5 2022), two observer states and 11 ‘other states’. Bagga-Gupta and Kamei (Citation2022) critically discuss places-spaces like Sapmi and Nagalin that counter such hegemonic politically sanctioned imaginaries.

10 My father’s life became shaped by what Kennedy calls ‘the problem of population transfers along with ethnic cleansing’; he was a teenage-refugee whose family home lay 50 kms on the wrong side of the Radcliffe Line that carved out Pakistan from the sub-continent of India in mid-1947. Cyril Radcliffe, an English-man who had never ventured beyond France, drew the line that would mark the immediate lives of over 88 million people, and their descendants well into the 21st century, both in and outside the territories it demarcated.

11 Both voluntarily and involuntarily.

12 While movements across analogue-digital contemporary spaces have been empirically explored (see for instance, Gynne Citation2016; Messina Dahlberg Citation2015), the role of digitalization in human existence came center-stage during the pandemic.

13 A caveat here is the uptake of conceptualization related to (super)diversity in nation-states conventionally understood as South-East places-spaces.

14 See for instance Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016), the framework offered by the Douglas Fir Group in 2016 (including commentaries) in The Modern Language Journal. See also Bagga-Gupta (Citation2018, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), Finnegan (Citation2015).

15 For instance, special issues of the International Journal of Multilingualism (2019, 2021), Journal of Language, Identity and Education (2017), Journal Language and Education (2015, 2018, 2019), Journal of Multicultural Discourses (2019), Languages (2018), and conferences of Language, Identity and Education in Multilingual Contexts (2018 Dublin, 2019 York, 2020 The Haag), Translanguaging: Opportunities and Challenges in a Global World (2018 Ottawa), Multilingual Language Theories and Practices (2019 Corfu), Translanguaging in the Individual, at School and in Society (2019 Växjö), Languages, Nations, Cultures: Pluricentric Languages in Context(s) (2019 Stockholm).

16 Neologisms that have emerged include, pluri-lingualism/languaging, metrolingualism, trans-lingualism/languaging, new-speakerism, etc.; new understandings include the ways in which named-languages are increasingly mixed in Europe and the United States (see Bagga-Gupta and Messina Dahlberg Citation2021).

17 As illustrations, Makoni and Pennycook (Citation2007), Pennycook and Makoni (Citation2020).

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2013. “The Boundary-Turn: Relocating Language, Culture and Identity Through the Epistemological Lenses of Time, Space and Social Interactions.” In Alternative Voices: (re)Searching Language, Culture and Identity, edited by S. Hasnain, Bagga-Gupta, and S. Mohan, 28–49. England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2017a. “Going Beyond Oral-Written-Signed-Virtual Divides. Theorizing Languaging from Social Practice Perspectives.” Writing & Pedagogy 9 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1558/wap.27046.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2017b. “Language and Identity Beyond the Mainstream. Democratic and Equity Issues for and by Whom, Where, When and why.” Journal of the European Second Language Association 1 (1): 102–112. doi:10.22599/jesla.22.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2018. “Going Beyond “Single Grand Stories” in the Language and Educational Sciences. A Turn Towards Alternatives." Special Issue: “Language Across Disciplines.” Aligarh Journal of Linguistics 8: 127–147. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:hj:diva-42343.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2022a. “RE- Vocabularies we Live by in the Language and Educational Sciences.” In The Languaging of Higher Education in the Global South. Decolonizing the Language of Scholarship and Pedagogy, edited by C. Severo, S. Makoni, A. Abdelhay, and A. Kaiper, 61–84. New York: Routledge.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2022b. “On Naming Traditions. Losing Sight of Communicative and Democratic Agendas When Language is Loose Inside and Outside Institutional-Scapes.” In Handbook of Language and Southern Theory, edited by A. Kaiper, L. Mokwena, and S. Makoni, 371–383. New York: Routledge.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2023a. “Analytical-methodological Entanglements. On Learning to Notice What, Where, When, why and by Whom in the re-Search Enterprise.” In Re-theorizing Learning and Research Methods in Learning Research, edited by Crina Damşa, Antti Rajala, Giuseppe Ritella, and Jasperina Brouwer. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2023b. “Mobile Gazing. On Ethical Viability and Epistemo-Existential Sustainability.” In From Southern Theory to Decolonizing Sociolinguistics – Voices, Questions and Alternatives, edited by A. Deumert, and S. Makoni, 262-272. Cleveland: Multilingual Matters.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta, and Alan Carneiro. 2021. “Nodal Frontlines and Multisidedness. Contemporary Multilingual Scholarship and Beyond. SI: Advances in the Studies of Semiotic Repertoires.” International Journal of Multilingualism 18 (2): 320–335. doi:10.1080/14790718.2021.1876700.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta, and Machun Kamei. 2022. “Lines, Liminality and Lim. Disrupting the Nature of Things, Beings and Becomings.” Bandung Journal of the Global South 9 (1-2): 248–278. doi:10.1163/21983534-09010010.

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta, and Giulia Messina Dahlberg. 2021. “On Studying Peoples’ Participation Across Contemporary Timespaces: Disentangling Analytical Engagement.” Outlines. Critical Practice Studies 22 (1): 49–88. doi:10.7146/ocps.v22i.125861

- Bhambra, Gurminder. 2007. Rethinking Modernity. Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Burke, Rachel, Nisha Thapliyal, and Sally Baker. 2018. “The Weaponisation of Language: English Proficiency, Citizenship and the Politics of Belonging in Australia.” Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis 7 (1): 84–102. doi:10.31274/jctp-180810-107.

- Chester, Lucy. 2013. Borders and Conflict in South Asia. The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Dreze, Jean, and Amartya Sen. 2004. Hunger and Public Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Erlandson, David, Edward Harris, Barbara Skipper, and Steve Allen. 1993. Doing Naturalistic Inquiry. A Guide to Methods. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Finnegan, Ruth. 2015. Where is Language? An Anthropologists Questions on Language, Literature and Performance. London: Routledge.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1998. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Gynne, Annaliina. 2016. Languaging, Learning and Identities in Glocal (Educational) Settings – The Case of Finnish Background Young People in Sweden. Mälardalen: Sweden.

- Hübinette, Tobias, Peter Wickström, and Johan Samuelsson. 2022. “Scientist or Racist? The Racialized Memory war Over Monuments to Carl Linnaeus in Sweden During the Black Lives Matter Summer of 2020.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies 9 (3): 27–55. doi:10.29333/ejecs/1095.

- Kennedy, Dane. 2016. Decolonization. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Landri, Paolo, and Eszter Neuman. 2014. “Introduction. Mobile Sociologies of Education.” European Educational Research Journal 13 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2304/eerj.2014.13.1.1.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method. Mess in Social Science Research. London: Routledge.

- Lincoln, Yvonna, and Egon Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Makoni, Sinfree, and Alastair Pennycook, eds. 2007. Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages. Cleveland: Multilingual Matters.

- May, Stephen. 2014. “Introducing the "Multilingual Turn".” In The Multilingual Turn. Implications for SLA, TESOL and Bilingual Education, edited by S. May, 1-6. New York: Routledge.

- Messina Dahlberg, Giulia. 2015. Languaging in virtual learning sites: studies of online encounters in the language-focused classroom. Örebro Studies in Education 49. Örebro University. Sweden.

- Pavlenko, Agneta. 2019. “Superdiversity and Why it Isn’t. Reflections on Terminological Innovations and Academic Branding.” In Sloganizations in Language Education Discourse, edited by S. Breidbach, L. Küster, and B. Schmenk, 142-168. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pennycook, Alastair, and Sinfree Makoni. 2020. Innovations and Challenges in Applied Linguistics from the Global South. London: Routledge.

- Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade. 2011. Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

- Pietikäinen, Sari, H. Kelly-Holmes, A. Jaffe, and N. Coupland. 2016. Sociolinguistics from the Periphery. Small Languages in new Circumstances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- R’boul, Hamza. 2022. “Epistemological Plurality in Intercultural Communication Knowledge.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 17 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1080/17447143.2022.2069784.

- Shi-xu. 2016. “Cultural Discourse Studies Through the Journal of Multicultural Discourses: 10 Years on.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 11 (1): 1–8. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2016.1150936.

- Shi-xu. 2022. “Towards a Methodology of Cultural Discourse Studies.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 17 (3): 201–202. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2022.2159418.

- Västerbro, Magnus. 2018. Svälten. Hungeråren som formade Sverige [Famine. The Famine That Created Sweden]. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag.

- Wolcott, Harry. 1999. Ethnography: A Way of Seeing. Lanham: Rowman Altamira.