This special issue volume stems from 8th International Sikh Studies Conference hosted by the Dr. Jasbir Singh Saini Endowed Chair in Sikh and Punjabi Studies at the University of California Riverside (UCR) on May 5–6, 2023. Sikhs have been a part of the social fabric of North America for more than 150 years. When discussing the history of Sikhs in North America, there are a series of key events which drastically impacted the Sikh narrative in North America. These events include, but are not limited to, the Anti-Asian riots across the Pacific Northwest, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind of 1923, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and the Oak Creek Gurdwara massacre in August of 2012. Major anniversaries for some of these catalyst moments occurred between 2021 and 2023. These include the 100th anniversary of the U.S. v. Thind (2023), the 20th anniversary of Balbir Singh Sodhi’s murder following the 9/11 attacks (2021), and the 10th anniversary of the Oak Creek Gurdwara massacre (2022). In addition, 2023 was also the 50th anniversary of the registration of Sikh Dharma International as a recognized non-profit 501c (3) religious organization in the United States. And with all the fallout from the recent news of Yogi Bhajan's misconduct during his reign, it might be an appropriate time for updated reflections on Punjabi Sikh and Gora Sikh relations in North America.

Scholarship and community activism surrounding anti-Sikh hate incidents and the archiving of Sikh history on the continent within the past twenty years were developed because of the rise of antagonism, abuse, and discrimination following the two latter incidents. Given the recent anniversaries, the 8th Sikh Studies Conference at UC Riverside, Sikhs in North America: Remembering Key Historical Events, Challenges and Responses, served as an opportunity to reflect upon the scholarship of Sikhs in North America, and the interconnectedness of many historical threads across boundaries and borders from numerous perspectives and approaches to touch on intersectional issues such as: racialization, ethnicity, class, gender, criminalization, anti-Sikh hate, Sikh activism (past and present), assimilation, inclusivity, intergenerational trauma, education, and other relevant topics.

Conference events began Friday morning with Daryle Williams – Dean for the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at UCR – inaugurating the conference and welcoming the global audience. Dean Williams shared that the conference was an excellent opportunity for educational and academic exchange and debate within the field of Sikh Studies. Following an introduction by Pashaura Singh, Parminder Kaur Bhachu delivered the keynote speech on ‘Migration, Creativity, Innovation: Sikh Migrants and Values Define the 21st Century.’ In her keynote address, Bhachu shared her latest work Movers and Makers in which she forcefully argued that immigrants have been the most innovative people in the world. She remarked that the intrinsic Sikh sensibilities of collaboration, of sharing, and of radical generosity as reflected in egalitarian Sikh institutions, have much in common with the contemporary ‘equalizing’ movements of open-source and licensing technologies, free-souls sharism, crowdsourcing, participative pedagogy, and the creative commons. Historic Sikhs traditions are thus absolutely in sync with the currents of our times and catalyze diasporic creativity.

Louis Fenech offered a response to the keynote speech beginning with a self-reflexive note that this conference itself is a result of ‘movers and makers’ like those discussed by Bhachu in her book. Fenech brought an historian’s perspective as he noted the Punjab’s history as a frontier in which ‘Islamicate and Indic ideas, values, peoples, movers, and makers interacted and exchanged.’ Fenech used seventeenth–eighteenth century Sikh poet Bhai Nand Lal as an illustrative example of one such historical ‘mover and maker’ as he immigrated to the Punjab from Ghazni and ‘conveyed Sikh teachings’ in ‘the language of Islam modified to Indian tastes,’ all while simultaneously drawing from and pushing back against the Persian literary tradition in his poetic creations. Fenech considered several Sikh values in turn, each ‘gloriously delineated’ in Movers and Makers. His last point was about ‘eternal optimism’ (chardi kala) and the final term in the Ardas, ‘welfare of all’ (sarbat da bhala), as co – dependent and binding values expressed by the figures in Bhachu’s book. Fenech ended on the point that, not only the interviewees in Bhachu’s book, but also the members of the present conference ‘collectively reveal the creativity and the resilience and sharing in a fragile and uncertain world’.

Associate Dean Gloria Gonzalez-Rivera and Harkeerat Singh Dhillon delivered special remarks at the reception dinner. Dean Gonzalez-Rivera thanked the donors of the Jasbir Singh Saini endowment for bringing such distinguished scholars to the UCR campus, and for solidifying the study of Sikhism at UCR. She noted that this conference not only draws attention to the contributions of Sikhs in North America, but as a fellow scholar of the humanities, also noted that such a conference may ‘provide us with a better understanding of the human condition ().’ Harkeerat Singh Dhillon provided a sincere reflection as a physician on the challenges of the past few years during the Covid pandemic. Dhillon alluded to the efforts by the Sikhs of New Delhi as they provided ‘Oxygen Langars’ to all suffering the effects of the Delta variant, regardless of religious background. Echoing Dean Gonzalez-Rivera’s point that there is in North America and around the world a ‘strong need for spiritual guidance, for solid values that inform our decisions and actions as individuals and as members of our communities,’ Dhillon offered the closing observation that ‘seva and sharing, crossing lines of race and religion, love and caring is the key.’

Figure 1. Associate Dean Gloria Gonzalez-Rivera delivering her remarks at the reception of the conference.

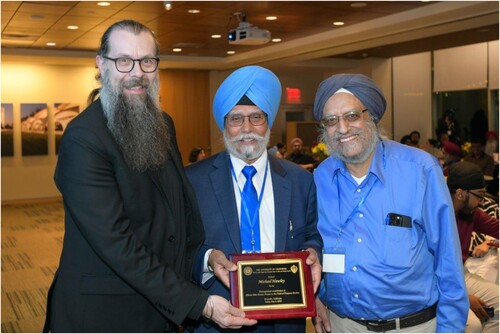

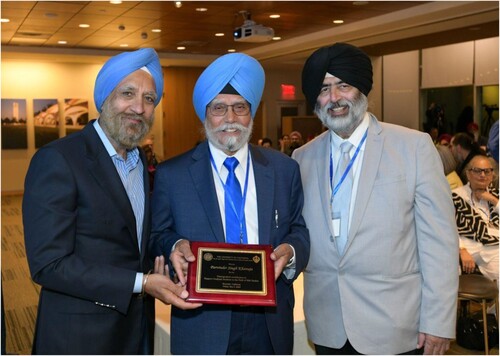

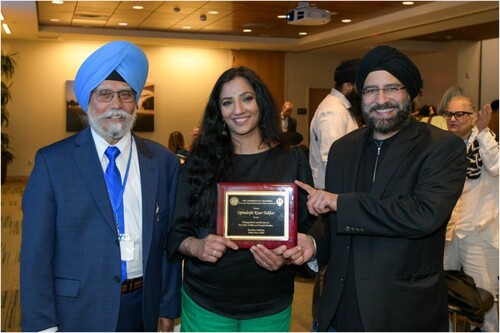

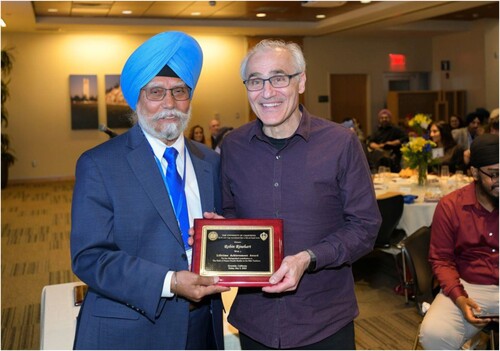

Delivering the second Keynote Speech during the evening reception, Karen Leonard shared her ethnographic work with Punjabi immigrants in Southern California and Mexico who belong to the early twentieth century wave of immigration and contrasted this with the 1960s wave of Punjabi immigration. Following the keynote address, six individuals were honored by Pashaura Singh for their contribution to the field of Sikh Studies. First, Parminder Bhachu was recognized for her contribution to the field of Sikh Diaspora Studies. Second, Doris Jakobsh was honored for her contribution to the field of Gender Studies in the Sikh Tradition. Third, Opinderjit Kaur Takhar was celebrated for her groundbreaking work as the Director of the Centre for Sikh and Punjabi Studies. Fourth, Robin Rinehart was recognized for her distinguished contribution to the study of Dasam Granth within the Sikh Tradition. The fifth honoree, Michael Hawley, was recognized for his work on the Alberta Sikh History Project and its impact on the field of Sikh Diaspora Studies. Finally, Parvinder Singh Khanuja was honored for his commitment to and continuous support of graduate students in Sikh Studies (, , , , ).

Figure 2. Parminder Bhachu receiving her Lifetime Achievement Award for her contribution to the field of Sikh Diaspora Studies from Karen Leonard and Pashaura Singh.

Figure 3. Doris Jakobsh receiving her Lifetime Achievement Award for her contribution to the field of Gender Studies in the Sikh tradition from Verne A. Dusenbery and Pashaura Singh.

Figure 4. Michael Hawley was honored for his Alberta Sikh History Project by Amritjit Singh and Pashaura Singh.

Figure 5. Parvinder Singh Khanuja was honored for his continuous support of graduate students in Sikh Studies by Harkeerat Singh Dhillon and Pashaura Singh.

Figure 6. Opinderjit Kaur Takhar was honored for her contribution in establishing Centre for Sikh and Punjabi Studies at Wolverhampton University in the UK by Pashaura Singh and Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair.

Over the course of two days, seven sessions focused on a variety of topics relating to the history and experiences of Sikhs in North America including

Public Perception, Multiculturalism, Race and Gender; American Fascism and Sikh Precarity; Race, Citizenship, and the Sikhs; Sikh Dharma International and Gora Sikh-Punjabi Sikh Relations; Preserving, Documenting, and Narrating Sikh North American History; and White Supremacy, Violence, Right-Wing Politics and the Sikhs.

This Special Issue includes papers that were presented at the Sikhs in North America: Remembering Key Historical Events, Challenges and Responses conference. First, Sasha Sabherwal focuses on the Sikh diaspora of the Pacific Northwest (PNW) to trace how multicultural discourse has ‘obfuscated state sanctioned racial violence’ of Sikhs beginning in the 1980s and 1990s continuing into the present. She draws from analysis of Deepa Mehta’s film Beeba Boys as well as ethnographic fieldwork that analyzes the images of the ‘Surrey Jack’ and the ‘Kent Boy,’ stereotypes attached to Punjabi men in the PNW. Second, Tavleen Kaur argues that much like Sikhs in the United States today, Bhagat Singh Thind was a diasporic subject seeking social, cultural, and political recognition in a settler-colonial state. By providing critical perspectives on Thind’s legal battles with the United States and contextualizing them in relation to contemporary Sikh advocacy, she illustrates how Thind being co-opted as an exemplary ‘Sikh American’ model is somewhat incongruent with his own evolving beliefs and choices. The third paper is Karen Leonard Keynote Speech from the conference, ‘Changes Over Time: Punjabis, Punjabi Mexicans, and Sikhs in North America,’ which discusses her earlier ethnographic work with Punjabi-Mexicans in the early twentieth century wave of immigration in contrast with the 1960s wave of Punjabi immigration. The religious identities of her interlocutors were far more complicated than is usually assumed when labeling these immigrants strictly as ‘Sikhs,’ and she noted that recasting the pre-1960s ‘Punjabi diaspora’ as a ‘Sikh diaspora’ places emphasis on religion rather than ‘language, occupation, or place of origin.’

The next five papers come from a roundtable at the UCR International Sikh Studies Conference on ‘Sikh Dharma International and Gora Sikh-Punjabi Sikh Relations.’ First, Verne Dusenbery offers a useful introductory evaluation of 3HO (Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization), also known as Sikh Dharma, from the 1970s to today. Dusenbery reflected on the difficulties this group has had in seeking legitimacy as part of the Sikh Panth, as well as the role Sikh Dharma has had in spreading Sikhism in North America. Second, Sangeeta Luthra’s paper, ‘From Charismatic Hierarchy to Autonomous Sangats: A Personal Reflection on the Evolution of 3HO Sikh Dharma Community,’ describes the shift from an organization centered on its charismatic founder toward ‘autonomous sangats.’ Third, Philip Deslippe’s ‘Provocations: Reappraising the Construction of Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga’ revisits his 2012 article for Sikh Formations titled ‘From Maharaj to Mahan Tantric’ and argues that the article played a role as both a threat to legitimacy and then a tool of crisis management for 3HO. Fourth, Nirinjan Kaur Khalsa-Baker speaks to the struggle to establish a 3HO-Sikh identity in the wake of Yogi Bhajan and describes a ‘hermeneutic chaos’ emerging from the question of whether Sikh Dharma teachings can be separated from its founding teacher. Finally, Simranjit Steel discusses the challenges of predominantly white Sikhs from 3HO in a predominantly Punjabi religion by analyzing community emails circulated by community leaders as examples of social ‘processes of legitimacy’ ().

Figure 7. Simranjit Steel (center) presenting her paper during the panel commemorating the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the 3HO.

The next paper comes from the ‘American Fascism’ and Sikh Precarity (Roundtable Discussion) which featured G.S. Sahota, Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, and Anneeth Hundle. Following the Oak Creek massacre which was a direct result of the resurgence of white supremacy and Islamophobia fueled by the ‘Tea Party’ Republicanism, what began to come into view was a distinctly American brand of fascism. The panel reflected on the nature of this ‘American fascism’ and its implications for Sikhs in North America. Sahota’s paper, included in this special issue, aims to slightly shift fundamental concepts, canons, methods, and attitudes in the reemerging field of philology from the perspective of marginalized minority experience. Sahota argues that the recapture of philological power by the minor allows the partial restoration of colonized traditions, reconfiguring distinct canons and connections across expansive world-textual fields ().

The final three papers in this Special Issue focus on contemporary projects by Sikh scholars and activists. Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra looks at the art of storytelling based on the power of her lived experiences as a Sikh woman and sharing Sikh stories of migration and settlement from a place of erasure, and then power, anti-colonialism, and anti-racism. She used the Sikh Heritage Museum, a National Historic Site Gur Sikh Temple, the oldest still standing gurdwara in the western hemisphere, in Abbotsford, BC, as a living site of Sikh story telling. Tejpaul Singh Bainiwal discusses the recent launch and subsequent work of the Sikh American History Project (SAHP). He uses the idea of ‘siloed scholarship’ to address not only the lack of focus and research about Sikh Americans, but also the limited knowledge about the community and the exclusion/under-representation of Sikh Americans in the broader Asian American and American history. The final essay, Komal Chohan’s ‘Unleashing the Power of the Youth: A Sparkling New Era of Sikh Activism,’ looks at how organizations like Umeed-Hope Inc are helping to shift cultural norms and expectations around gender roles by carving out new spaces. She offers insight into the experiences of Sikh women historically and in these new spaces, the threats they face as they continue to push for equality and empowerment, and the importance of providing platforms for marginalized groups to advocate for themselves ().

The conference was one of its kind as it brought together scholars and activists to discuss the history and experiences of Sikhs in North America. The conference also marked an opportunity to revisit a series of key anniversaries that occurred between 2021 and 2023. Despite how drastically these events shaped the Sikh narrative in North America, the anniversaries passed without a critical analysis of the impact of each event. Young scholars are engaging more with these socio-political events leading to an evolution in the field of Sikh Studies ().

The conference sponsors included Dr. Jasbir Singh Saini Trust and the Sikh Foundation of Palo Alto. We would like to acknowledge our supporters who provided help in various ways to make the conference a great success. Dilmohan Singh Chadha, Chairman of Sikh Foundation of Palo Alto, Harkeerat Singh Dhillon, and Saranjit Kaur Saini, contributed energetically in many ways to build the program in Sikh Studies at the University of California, Riverside. Their selfless and untiring support is much appreciated. As a member of organizing committee Adam Tyson helped both of us in finetuning all the events and other necessary arrangements for the conference. A number of graduate and undergraduate students assisted in various ways at the reception. We thank all of them for their timely help ().

Multi-Disciplinary Financial and Administrative Unit (MDU) staff, Tanya Wine, Diana Marroquin, Irene Dotson, Dawn Viebach and Geneva Amador gave assistance in organizing this international event and helped with publicity. They worked behind the scenes for months to make travel arrangements of speakers and other participants. Much appreciation goes to them for competently organizing the last-minute details of the reception program ().

The local Gurdwara and the esteemed members of the Sikh Center of Riverside, along with community members from Southern California participated in the conference activities enthusiastically. Their presence was indeed the living example of town-gown cooperation. Our efforts have always been to encourage Sikh community participation in the academic activities of the Sikh Chair at UCR so that they are aware of our work to promote the field of Sikh Studies in the western academy. Once the local Sikhs and the University professors work out problems of communication, they can move together towards academically sound approaches to teaching and research of the Sikh tradition. As that shared experience continues to broaden, so will community and university support for Sikh Studies ().

Figure 11. Pashaura Singh with Amrik Singh, Jaswant Singh Jhawar, Surinder Singh Kohli and Upkar Singh of the local Gurdwara, Sikh Center of Riverside.

The unique aspect of this conference was to invite different organizations of Sikh activists who raised the real issues faced by the younger generations. As they grew up in the US and received their education in the western academy, they were more forceful in confronting the challenges of hate crimes and ignorance about the Sikhs and Sikh traditions in the contemporary society. They were all bubbling with enthusiasm to change the perceptions of old generations of Sikhs as well as educate the non-Sikhs simultaneously. It is no wonder that Sikh activists were always ready with big smiles for our conference photographer ().

Figure 12. Kiran Kaur Gill, Executive Director of the Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund (SALDEF), Navdeep Singh of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and SALDEF, Jaslin Kaur, New York-based Sikh American Activist and co-chair of NYC Democratic Socialists of America, Komal Kaur Chohan, a Sikh American Activist and Founder of Umeed-Hope, and Tarina Kaur Ahuja, Co-Founder of Young Khalsa Girls.

One of the honorees, Robin Rinehart, suddenly caught flu just a day before her flight to the conference. She had to cancel her participation with regrets due to the COVID-19 precautions, since she did not want to pass on the virus to anyone else in the conference. Rinehart has done an amazing work on the text of the Dasam Granth, a work which offers an overview of the debates on the Dasam Granth by providing an innovative reading of the text in the context of courtly literature of India. Her balanced approach in examining the most controversial issues in the field of Sikh studies is highly commendable. Louis E. Fenech received the award on her behalf, and it was then mailed directly to her address so that she can cherish the recognition of her academic work ().

Figure 13. Louis E. Fenech receiving the award from Pashaura Singh on behalf of Robin Rinehart for her contribution to the Dasam Granth studies.

Actually, we had envisioned two main outcomes of this conference, one immediate and quantitative, and the other long term and qualitative. The immediate outcome of this conference is the publication of selected papers emerging from the conference on a coherent theme. This special issue of Sikh Formations fulfills this preliminary task. However, we would like to publish the highly revised and enlarged chapters in an edited volume in the near future. The task of soliciting contributions from among the participants and organizing and editing the volume will fall to the chair of the organizing committee of this conference. The good news is that Routledge academic publishing house has already conveyed to us that it will publish such a volume in its Routledge Critical Sikh Studies series. In the long term, this conference will contribute to the on-going process of community building between individual scholars as well as across institutions. This conference has provided an opportunity for scholars with otherwise disparate fields of inquiry in Sikh Studies / Asian American Studies to enter conversation with one another. Therefore, this conference represents a first step in developing further collaborative projects among scholars of UCR and other universities around the world. The group photograph of the conference participants speaks for itself ().

In sum, 8th Sikh Studies Conference was a very successful event for the participants and the organizers. Through this issue we are presenting selected essays read in the conference to the worldwide readership, and we welcome suggestions and constructive criticism that may be useful to the authors in their future research. In fact, this feedback will be quite useful to the authors and the editors when they revise these essays to be included in the edited volume. This special issue of Sikh Formations and the conference thus will not be the last in a series of successful ventures, but rather a steppingstone to a fresh round of seminars, symposia, and town-gown cooperation in Riverside ().

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).