Abstract

This article deals with the theoretical and methodological problems in any effort to conceptualize a model of multinational federalism. This is shown through an exemplary review of scholarly literature frequently ending up in nothing else but tautological regressions and/or ideologically driven dichotomizations of basic terms and concepts such as ethnic group, community, nationality, minority or (co-)nation when using these terms interchangeably, in particular, through combinations such as ‘minority-nation’, in order to get hold of the phenomenon of overlapping social, political and cultural diversities. These problems of conceptualization, symbolized through the perennial question ‘What ‘is’ a nation or minority?’ in order to be able to establish an allegedly objective or universal definition, are trapped in what I call the ethnic–civic–national oxymoron following from political theories of nationalism and liberalism based on normative-ontological approaches. In order to overcome the mentioned theoretical and methodological trap(s) based on the confusion of epistemology and ontology, this article argues for the necessity to overcome ideological dichotomizations through the method of triangulation. In the end, based on this method, I try to develop an institutional model of multicultural instead of multinational federalism which allows from the very beginning to take the empirical processes of ethnification and/or de-ethnification as major drivers for ‘multiple diversity governance’ into account. This de-construction of the concept of multinational federalism and the re-conceptualization of a model of multicultural federalism also allows to overcome the theoretical battles in power sharing literature between so-called accomodationists and integrationists, based on the dichotomization of their policy prescriptions.

Introduction

This article will deal with the theoretical and methodological difficulties in the conceptualization of multinational federalism at the interface of law and political sciences and try to outline a new approach following from the theoretical concept which was termed ‘multiple diversity governance’ (see Marko, Citation2019). As will be demonstrated in the next sections, it is not pure coincidence that lawyers, political scientists or social philosophers end up in a terminological jungle when dealing with phenomena of cultural, social, or socio-economic diversity and their interrelationships. Frequently, the interchangeable or contradictory use of the terms and concepts of society, people, nation, nationality, minority, or ethnic group is leading to nothing else but a series of nominal definitions ending in tautological regression and/or ideologically driven dichotomizations. Also the futile attempt to establish a politically, legally or scientifically recognized general definition of the concept and term of minority and therefore substituting this term through terms and concepts such as minority-nation, co-nation, or community demonstrates that something must go wrong in the process of conceptualization.

However, every effort thus, as one of the anonymous peer reviewers suggested, to first ‘properly address and define’ the concept of multinational federalism will remain trapped ‘in the shortcomings of a positivist social science’ when transforming political phenomena to be critically analyzed into a priori given transcendental categories, concepts or models as if naturally existing ‘and thus to overlook the interpretative aspect of human behaviour and significance of value and meaning in human experience’ (Loughlin, Citation2005, pp. 381, 389). In conclusion, so the main hypothesis in this first section following from a historic-sociological analysis of state formation and nation building in Western and Central Europe to provide the context for a critical review of exemplary scholarly literature dealing with federalism, power sharing and conflict management, all the efforts to a priori construct and define a concept of multinational federalism remain trapped not only in a confusion of epistemology with ontology, but also in—what is termed by me—the civic–ethnic–national oxymoron based on ideological presumptions and prescriptions.

The second and third sections of this article are thus dedicated to explain the necessary theoretical and methodological changes from primordial theories of nationalism and/or positivist thinking in law to a social constructivist approach as well as the method of triangulation to be able to overcome the inherent dichotomies in the mentioned oxymoron and, thereby, provide fresh ideas for the problem how to (re-)conceptualize the perennial problem of how to accommodate political unity with legal equality and cultural diversity for peaceful living together. Therefore, ethnicity must no longer be seen as an intrinsic property of individuals, territories, or institutions in opposition to civic(-republican) groupings of society and the associations or even corporatist institutions they establish, but as an empirical process of group formation through social organization and institutionalization (see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 138–162). Such empirical processes might, but need not necessarily lead to an antagonistic political polarization of societies which is the criterion used here for the definition of so-called deeply divided societies. Hence, not cultural diversities being confused with ethnic difference are the root cause of the division of societies and possibly even (violent) conflicts in terms of a ‘clash of civilizations’ (Huntington, Citation2011), but absolutist claims for the political and jurisdictional control of the entire territory and the population, dressed in the phrase of the ‘sovereignty of the nation’ in political proclamations and legal documents as we will demonstrate. Finally, against the conflation of culture with ethnicity as well as the dichotomization of private and public by liberalist as well as nationalist ideologies, the concept of multicultural instead of multinational federalism shall demonstrate the comparative advantage of what I termed—in contrast also to social constructivist instrumentalist approaches in studies on so-called ethnic conflict—a ‘social constructivist-structuralist approach’ (Marko, Citation2019, p. 161) how to theoretically reconcile political unity with legal equality and cultural diversity. This approach and the concept of multicultural federalism shall provide a new perspective for future empirical research about the interrelationship of federalism and power sharing.

The Historic-sociological Context of State Formation and Nation Building in Europe

When we start not with an a priori definition of either multi—or plurinational democracy or federalism, but the perennial problem of how to create a legitimate political order in which a diversity of individual persons and diverse peoples as groupings can peacefully, i.e. ‘civilly’ (see instead of all Elias, Citation1997, pp. 356–376), live together in one state based on the rule of law and democratic governance, we have to highlight two main ideas and normative principles of such state formation in Europe. The first of these two constitutive principles for state formation is expressed through the notion of the internal exercise of jurisdictional power by state authorities in terms of rule of law over the people (singular!) living on its territory so that Hans Kelsen could, against the dominant categorical distinction between human persons and citizens of national states in all contemporary European theories of state and law, argue in his seminal monograph ‘Allgemeine Staatslehre’: ‘ … also foreigners are part of the Staatsvolk insofar they are subject to the legal order of the state; even if they do not enjoy any rights, but have only duties’ (Kelsen, Citation1925, p. 405, transl. JM). Following from the development of the Westphalian peace order until the twentieth century, the second constitutive principle not only for state formation as such but also the relations between them in terms of public international (!) law is laid down in the doctrine of the sovereignty of states. This principle claims the external independence of national states in terms of a right to territorial integrity and non-intervention by other states.

However, these two constitutive principles have quite differently been conceptualized throughout the centuries since 1648 depending on the respective problems to be solved. Most important for our purposes, the Roman law term ‘majestas’ was translated and re-constructed by Jean Bodin in his ‘Les Six Livres de la Republique’ of 1583 as the ‘sovereignty’ of the king or prince in power which is declared to be ‘indivisible’ in order to be able to legitimize his absolutist rule. And the ideologues of the French Revolution and their re-interpretation and re-construction of this concept in terms of the principle of ‘popular’ sovereignty turned this absolutist conception of sovereignty simply upside down. In addition, the notion of the sovereignty of the state as political institution, having symbolically been identified before 1789 with the person of the king in the concept of ‘The King’s Two Bodies’ (Kantorowitz, Citation2016), was coupled with the alleged sovereignty of an imagined socio-politically constitutive entity, namely the Nation. This can best be seen and understood through Abbé Sieyés’ rhetorical question ‘Qúest-ce que le tiers etát?’ and his conclusion ‘The Third Estate is always identical to the idea of a nation … ’ and how this has been co-ordinated with the exercise of power in Article III of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen which declares: ‘The principle of sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual can exert authority which does not emanate expressly from it’ (for a longer analysis of the interplay between the imagination and construction of these constitutional principles enshrined in the respective legal texts see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 42–59, in particular, 56).

To this day, therefore, Bodin’s absolutist and therefore exclusivist conception of sovereignty as indivisibility is extended and upheld, as we will see below, not only in French constitutional doctrine by the notion of the unity of the nation state, allegedly possible only in terms of preserving the indivisibility of the Nation against even the most modest claims for power sharing (see Decision of 9 May 1991, Case no. 91–290 DC, Act on the statute of the territorial unit of Corsica). Together with the doctrinal distinctions of Western European theories of state and law in terms of a ‘constitutive power’ (of the people) from which all law shall emanate and a ‘constituted power’ in terms of legitimate institutions of a state, we, however, end up in what must be called a democratic or constitutional paradox with the empirical observation expressed by Ivor Jennings: ‘The people cannot decide until someone decides who are the people’ (Jennings, Citation1956, p. 56). Hence, the idea of the indivisibility of sovereignty of one people identified with the nation stemming from Jacobin French constitutional doctrine must remain nothing but one of the constitutional myths defying to this day political and legal pluralism as such as well as ideas and institutional mechanisms of power sharing within federations.

The other factor which can be traced back to J. G. Herder’s trinitarian conception of state formation and nation building (that is, one language must be equated with one people with the right to form its own national state; see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 63–64) finds its expression in the so-called Böckenförde paradox. This German legal scholar and judge of the German Federal Constitutional Court famously postulated that the ‘modern, secular state cannot provide the necessary trust, solidarity and social cohesion on which its existence depends’ (Böckenförde, Citation1991, p. 112). In his opinion, these public goods can only be produced by allegedly pre-political religious and/or linguistic communities, thereby implicitly, nevertheless categorically separating the political from the cultural sphere of life. Also, this paradox with its underlying dichotomization demonstrates perfectly well how the fact of cultural, social, and political diversities and therefore pluralism is transformed by the mental process of reification and even naturalization of socially and politically constructed categories such as one (specific) language, religion and people into the notion of a priori and de facto existing homogenous languages, cultures and/or communities as if they were neatly separated from each other from the beginnings of history (as primordial and ethno-symbolist-perennial theories of nationalism claim; see A. D. Smith, Citation2019). It goes without saying that these notions are in no way in conformity with the actual processes of group and state formation through social organization and institutionalization (see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 148–159) when, for instance, ‘peasants’ were transformed ‘into Frenchmen’ in the course of centuries as the seminal study of Eugen Weber (Citation1976) has proven.

In conclusion, both these traditional constitutive principles in the processes of European state formation and nation building, the purported sovereignty-as-indivisibility and therefore identity of state and nation as well as the alleged homogeneity of cultures and communities as if there were one ‘Volk’ (people) or nation as legacies of the French model of a civic state-nation and the German model of an ethnic nation-state (see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 58, 65) must be taken into consideration as historic-sociological and political-ideological context for the hypothesis that the conceptualization of a model of multinational federalism for the effective governance of cultural, socio-economic and political diversities through the accommodation of political unity with legal equality and the preservation of cultural diversity cannot work as long as this context is not ideologically and theoretically adequately reflected. As we will show in the next sub-section, this is the reason why in an exemplary review of scholarly literature about the efforts to conceptualize multinational democracy and federalism, two interrelated problems remain unresolved which I summarize as the civic–ethnic–national oxymoron (Marko, Citation2019, pp. 132–135).

These are, first, what I call the nationalist identity fiction coupled with the sovereignty-as-indivisibility postulate so that all claims for even symbolic, let alone effective political participation through a model of multinational federalism will be seen as an attack against the political and constitutional ‘unity’ of state and society by those who claim to possess the monopoly for the definition and (legal) regulation of the relationship between a (however never) existing single, homogenous identity of persons or groupings of people or other persons and groupings. Hence, not allegedly ‘natural’ cultural differences are the root cause of more or less ‘deep divisions’ of societies and conflict, but such nationalist identity fictions coupled with the sovereignty-indivisibility claims create what has been termed the ‘dilemma of difference’ (Minow, Citation1990) as enduring basic problem of both nationalist ideology as well as liberal-individualist and liberal-egalitarian social philosophies (see Marko, Citation2019, in particular, pp. 111–132). Second, all conceptualizations of a model of multinational federalism and democracy based on these ideological assumptions remain thus trapped in the unresolved, contradictory dichotomy of a ‘good’ nationalism or patriotism versus a ‘bad’ nationalism in the tradition of Hans Kohn (Kohn, Citation2005).

These hypotheses will be further elaborated by an exemplary literature review in the following section in two steps. First, by showing a terminological jungle through the interchangeable use in combinations of the terms people, nation, state, ethnic group, nationality, minority, community, and society leading not only to tautological regression but also hiding the nationalist identity fiction and sovereignty claims; second, the constantly reproduced dichotomy of good vs. bad nationalism following from the dichotomization of civic versus ethnic which is equated with the naturalization and dichotomization of political versus cultural relations. The confusion of epistemology with ontology in these dichotomies leads, however, to wrong premises for empirical research and therefore the confusion of cause and consequence when ethnicity and so-called ethnic difference are taken as the root cause of conflict instead of analyzing the processes of ethnification through ‘social closure’ of groupings, possibly, but not necessarily following from ‘symbolic boundary drawing’ and functional differentiation and processes of political polarization of social relations which might lead, in the end, to the ‘deep division’ of societies.

The Civic–Ethnic–National Oxymoron in Conceptualizations of Multinational Federalism

Terminological Conundrums and the Nationalist Identity Fiction

For instance, for James Tully, ‘a multinational democracy emerges out of a cocoon of societies in which the majority tends to understand itself as nation’, which he then characterizes as a ‘multi-peoples society’ in the singular that is, moreover, conceptualized as ‘deeply diverse political community’ (Tully, Citation2001, pp. 1, 3, 9). However, what Tully pinpointedly addresses in this conception of a multinational democracy is the phenomenon which I have termed the nationalist ‘identity fiction’ (Marko, Citation2019, p. 119), when a so-called majority population identifies its values, culture, and socio-political habits with the state as the political and legal system in their possession. In consequence thereof, all others who are considered not to belong to the nation will be excluded or discriminated against and become second-class citizens at best. In a similar vein, David Miller upholds a categorical distinction between nations and nationalities and argues that ‘two or more ethnic groups’ are, despite the existence of ‘ethnic cleavages’, nevertheless able to participate in ‘a common national identity’ (Miller, Citation2001, p. 301). Based on this latter assumption he distinguishes between ‘nested nationalities’ and ‘rival nationalities’, with the former—in similarity with Tully’s ‘multi-peoples society’—characterized as ethnic groups whereby ethnicity in this case shall not be seen as an ‘intrinsic’ political ‘identity’. This type of nationalities is thought not to make particular territorial claims, but political demands to form clubs, associations, or churches to be conceived as an expression of civil society activities. In contrast then, he conceives ‘rival nationalities’ as antagonistic by definition, since each of them will seek control over the territory of the entire state, thereby preventing the development of an overarching national identity.

However, can this distinction and the concept of an ‘overarching national identity’ hold when reading the following passage only a few pages later identifying the interest of an ‘English majority’ with a ‘higher-level British identity’ so that Scots, when claiming secession, were simply befallen by ‘wrong consciousness’ in Marxist terminology?

Just as we might say of an individual who tries not merely to reinterpret but to jettison the identity he has been brought up to have that he probably doesn’t understand himself, we can say that for Scots to renounce their higher-level British identity would in one way be to fail to understand who they are, what makes them the people they are today … But there is also a second consideration. The British people taken together have established a valid claim to control the whole territory of Britain and this claim would be infringed by a unilateral secession. Claims to exercise territorial authority arise when people sharing a common national identity form a political community, and occupy territory over a substantial period of history. Thus the English too now have a stake in Scottish lands, a stake that arises from the process that I described earlier, namely the emergence of a common national identity from overlapping cultures, mutually advantageous economic cooperation and interwoven history. Unless and until there arises some kind of radical discontinuity such that these historical factors cease to affect contemporary political identities, the English majority have a right to resist unilateral secession … . (Miller, Citation2001, pp. 315–316, emph. added by JM)

[w]hen it comes to dealing with issues of diversity and cultural difference, it becomes evident that making the effort of adapting and compromising is, all in all, a business for minority members to take care of. Let me put it bluntly: developing dual (Catalan-Spanish) communicative skills is a ‘privilege’ reserved for the citizens of Catalonia, while Spanish ‘standard citizens’ remain ‘exempt’ from making comparable efforts of building complex identities. (Kraus, Citation2017, p. 110)

In light of such narratives developed in scholarly literature in order to empirically ground their definitional efforts, the following critical hermeneutic question must be raised: What shall be the difference in the meaning of all these terms and concepts of ‘nations’, ‘nationalities’, ‘minority nations’, ‘national minorities’, ‘ethnic groups’, and ‘societies’, ‘cocoons of societies’ or ‘political communities’? Are these differences ‘political’ and/or ‘ethnic’ and/or more or less ‘thin national’ identities of single groups and can there be, at the same time, ‘overarching nationalities’ or ‘pluri-national identities’ (Keil, Citation2016, pp. 45–46) of societies as a whole, then termed ‘joint nation’ with Switzerland supposedly the paradigmatic case (Keil, Citation2016, pp. 27, 48)? What makes, however, Switzerland different from multinational states or societies when academic literature claims that Switzerland is not multinational (Keil, Citation2016; Popelier & Sahadžić, Citation2019)? Is it because none of the language groups is supposed to have developed a national identity, thereby abstaining from making territorial claims or even requiring outright secession? But then, what about the process of the decades long internal nationalist mobilization including the use of violence leading to the creation of the new canton of Jura in 1974 through the secession of three administrative districts of the canton of Berne and the refusal of the newly created canton to accept the results of a series of referendums which not only led to the creation of the canton of Jura, but also to the—for these authorities unwelcome—fact that three other French-speaking administrative districts voted by majority to remain in the canton of Berne (Marko, Citation1995, pp. 500–514)?

The Reification and Dichotomization of Categories and Concepts and the Problem of Conflict Management

The terminological jungle and conceptual complexity even increase when alleged multinationality is combined with normative principles and institutional arrangements of models of federalism and/or power sharing as can be seen from the so-called ‘federal paradox’ (Gagnon, Citation2019, p. 95; Sanz Moreno, Citation2019, p. 347). The arguments underlying this paradox, summarized by Jan Erk and Lawrence Anderson (Erk & Anderson, Citation2009) following from their literature review, call into question whether constitutional provisions for ‘self-rule’ can be ‘accommodated’ with ‘shared-rule’ or, to the contrary, ‘exacerbate divisions’ so that the legal institutionalization of cultural group identities through different forms of self-government will simply entrench the division of societies and not bring political stability, but lead to claims for secession. Hence, the stakes for a ‘federal bargain’ for ‘coming together’ or ‘holding together’ types of federations (see Palermo & Kössler, Citation2017, p. 40) become more complex and thus higher, since classic models of federal systems such as the United States or Germany are conceptualized on the basis of the normative principles for liberal democracies in a, however, mono-national state. Already classic federal theory (see in particular Palermo & Kössler, Citation2017, pp. 13–50) had put into question whether territorial autonomies and federations can even be an effective tool for conflict management in socio-economically, i.e. allegedly only interest-driven, diverse societies because elite cooperation is seen as a necessary condition for ‘federal comity’ or ‘Bundestreue’—a concept following from German constitutional law doctrines (Woelk, Citation1999). In socio-political reality, however, such a normative prescription is said to create a ‘hierarchical structure of society’ (Elazar, Citation1985, p. 32) and to lead to problems of representativeness and accountability of elites and therefore both the in-put and out-put legitimacy of the system. At the same time, the development of originally ‘dual federal’ to ‘co-operative federal’ systems was brought about by processes of centralization of powers on behalf of the respective federal governments because of what was termed in Germany the ‘Politikverflechtungsfalle’ (joint-decision trap; Scharpf, Citation1985).

Conceptualizing multinational federalism, therefore, requires to give up the liberal myth of territorial ‘neutrality’, simply based on socio-economic interest representation and federal bargaining in terms of getting a-little-bit-more or a little-bit-less-of-the-cake-compromise, and the need to recognize and to effectively guarantee not only individual, liberal human rights, but also group rights. As Sören Keil thus rightly argues, the aim of (democratic) multinational federations shall be the transformation of the normative principle of (formal) equality before the law into ‘a right to diversity and freedom to choose a culture to identify with.’ As a consequence, ‘citizenship and identity have to be conceptualized in a framework that allows for plural citizenship and multiple identities’ (Keil, Citation2016, pp. 44–45). This means that ‘the protection of minority nations and recognised national minorities is part of the protection of individuals and their identities through group affiliation’ (Keil, Citation2016, p. 34). This conceptual requirement remains, however, hotly contested by liberal individualists and liberal egalitarians alike to this day who see in the recognition of groups and even more so in group rights the first step into the fragmentation and division of societies (for a comprehensive literature review and critique of the case law of apex courts, see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 111–132).

Nevertheless, advocates of multinational federalism argue that even under the condition of ‘rival nationalities’ (see Miller above) this model can secure peace, political stability, economic prosperity and, last not least, from a liberal perspective, individual freedom of choice (Kymlicka, Citation2000, p. 207). Hence, the empirical task of federalism and democracy in multinational states shall be the ‘accomodation of sub-state nationalism, that is, the collective needs and requirements of the nations or nationalities that co-exist within the larger, overarching nationality of the federation taken as a whole’ (Keil, Citation2016, p. 45). In light of this, federations should be seen as an ‘open process’ (Maiz, Citation2000, pp. 37–38; Requejo, Citation2006, p. 312) that includes the possibility to ‘redraw borders’ (Burgess, Citation2006, p. 107) with examples such as India and Canada as well as the above-discussed case of Switzerland.

However, from empirical case studies, not only from Europe (see Popelier & Sahadžić, Citation2019), we must learn that the optimism of the advocates of the concept of multinational federations might be too strong.

First, when ‘federalism and consociationalism are the two sides of the same coin’ in any conceptualization of multinational federations as Sören Keil correctly claims (Keil, Citation2016, p. 36), grand coalitions of nationalist elites will be prone to discriminate all those who do not belong to any of the nationalized groups within the electorate as already indicated above with reference to the nationalist ‘identity fiction.’ Supposedly representing the respective nationalized groups, this means that the leaders of mono-ethnic nationalist parties will not only be legitimized in so doing, but they will also try to marginalize all those who politically oppose their ethno-nationalist elite cartel in terms of power dividing in order to uphold their ethno-nationalist socio-economic and political monopoly over those parts of the electorate whom they claim to represent, and who, instead, fight for a system of power sharing by referring to the requirement for peace and functionality of the state as a whole and/or for societal cohesion (see for empirical evidence, Marko, Citation2013; Hulsey & Keil, Citation2019 and the case law of the ECtHR in Aziz v. Cyprus, 2004; Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2009; Zornić v. Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014). Therefore, also in all power sharing literature, the theoretical battles between so-called accommodationists in the tradition of Arend Lijphart and integrationists in the tradition of Donald Horowitz remain ongoing (for an overview see Marko, Citation2019, pp. 374–380).

Second, seen from the perspective of possible solutions on a theoretical continuum between centralization and federalization with a-/symmetric institutional arrangements, is it really possible that ‘multinational federations are likely to be characterised by asymmetry’ which does, as Keil argues, not mean, however, ‘that the whole federation is decentralised’, but ‘that some units, which represent different nations, have more rights than others’ (Keil, Citation2016, p. 51)? Will constitutionally entrenched asymmetries in the allocation of powers and mutual veto rights as core institutional elements of power sharing always be perceived as substantial and effective equality-in-diversity for the status of ‘partnership between equal nations’ as the ‘essence’ of multinational federalism (Keil, Citation2016, p. 45)? Or, quite contrary, will asymmetry be seen as political domination by the ‘majority nation’ or unfair privileges for some ‘nationalities’, ‘national minorities’ or ‘minority nations’, however you call them, and therefore discrimination of those groups who are not recognized and treated as equals?

Insofar, not accommodation, peace, and stability will result from multinational federations, but permanent conflict, instability, and the claim for secession as can be seen not only from the self-fulfilling prophecy in the quotation of Miller concerning the case of Scots above, but also from the case of the spiral of conflict, driven by one of Spain’s major parties, the conservative Partido Popular under the leadership of Mariano Rajoy, and the democratically elected representatives of the nationalist parties of Catalonia after the Catalan parliament had adopted a draft proposal for a new Autonomy Statute, referring to a ‘Catalan nation’ in its preamble in 2005. A political compromise on this wording was concluded after negotiations in the Spanish parliament, acknowledging Catalonia’s self-declaration as ‘nation.’ As a political compromise, this was intended and perceived as confirmation of Catalonia’s constitutional status as ‘nationality’ in order to avoid a constitutional conflict by dichotomization of the terms and concepts of nation and nationality, thereby also acknowledging the ongoing political process of regionalization of Spain. Both terms ‘nation’ and ‘nationality’ follow from the text of Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, referring to an ‘indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation, the common and indivisible country of all Spaniards’ as well as ‘the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed.’

However, the representatives of the Partido Popular in the Spanish parliament, at that time in opposition, had not only voted against this compromise, but also submitted a constitutional complaint to the Spanish Constitutional Court. In its judgment of 2010, the Court insisted on a ‘strictly legal interpretation’ that ‘Catalonia is not a nation’ since ‘only Spain ‘is’ the nation’ (for a comprehensive analysis see Pons Parea, Citation2013). When, after general elections in Catalonia, the parties with an independent political platform had won the majority of seats in parliament in 2012, the Catalan parliament passed a Declaration of Sovereignty in 2013 which was again contested before the Spanish Constitutional Court. In 2014, the Court declared the preambular provision that the Catalan people ‘is’ sovereign unconstitutional. Again, instead of leaving even at this moment a space for political compromise open—as this had been done by the majority of the Spanish parliament before the judgment was handed down in 2010—the reasoning of the Constitutional Court followed in its interpretation of the text of Article 2 the traditional ideological conceptualization of sovereignty-as-indivisibility in the spirit of Bodin, Rousseau and Sieyès by simply declaring that ‘two sovereignties cannot legally exist.’

But will such a ‘strict legal interpretation’ contribute to the de-escalation of the underlying political conflict? Instead of turning the relationship of the meaning of the terms nation and nationality into an exclusive dichotomy by nominal definitions based on traditional, centuries-old ideological pretexts, the Court could have interpreted the sovereignty declaration in an alternative way, that is, in line with the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights. In light of Articles 10 and 11 of the ECHR (freedom of expression and freedom of assembly; ECtHR, United Macedonian Organisation Ilinden and Others v. Bulgaria, 2005, para. 61) the sovereignty declaration could and should have constitutionally been conceptualized in terms of a constitutionally guaranteed right to start a political process through negotiations for more autonomy or even con-federal relationships. Thus the question remains: after such a rigorous, allegedly ‘strictly legal interpretation’, how will it be possible any longer for political actors to believe in a realistic chance which was offered by the judges of the Court themselves as a political compromise in their reasoning that ‘the Spanish parliament should take into account’ a region’s proposal to change the text of Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution in line with ‘the principles of institutional cooperation and loyalty to the Constitution’?

Hence, many authors claim right from the outset that a multinational federation is not possible at all in divided societies since ‘federal bargaining’ under these conditions will either end up in a strong unitary state as can, in particular, be seen from the swing of the pendulum from Boris Jelzin’s efforts of democratization back to authoritarian centralization under Vladimir Putin in the Russian Federation (Kembayev, Citation2018; Kremyanskaya, Citation2019), or the struggles for autonomy under a communist one-party state such as China (Buhi, Citation2019). Or, so the argument goes, also in post-conflict situations federalization in combination with power sharing institutionalizes competition and conflict, leading to a permanent blockade of the entire political system and a high risk for renewed inter-group violence as can be seen not only from Bosnia and Herzegovina (Marko, Citation2013; Sahadžić, Citation2019) as a paradigmatic case.

So what? Is unilateral secession, in the end, the only alternative left when liberal- and ethno-nationalists alike claim a monopolistic right to politically and jurisdictionally dominate the entire territory and so-called realists in international relations theory argue that all forms of autonomy, federalism and even more so multinational federalism are to be seen as a ‘slippery slope’ unleashed by its centrifugal forces? Hence, against Wayne Norman’s proposal (Norman, Citation2006), even a possible right to secession entrenched in constitutional law would then not lead to compromise, but only the possibility for blackmail in negotiation processes, and thus only prolong the political deadlock to the detriment of ordinary people.

From this literature review, we now can conclude the following (see in more detail Marko, Citation2019, pp. 103–105, 111–112, 132–136). Based on the normative-ontological approach which tries to identify and thereby to define a priori an allegedly universal ‘essence’/idea of social concepts, all efforts to define nations, nationalities, minorities, national minorities, minority nations, ethnic groups, political communities and so forth and their conceptual interrelationships lead only to three consequences as we could observe from the terminological jungle above:

First, the a priori categorical definition of the meaning of one term/concept requires to make reference to another term/concept defined in the same way so that all definitional efforts finally end up in a tautological regress in a similar vein such as a state shall be characterized by a people as a nation in possession of its state, so that a state essentially ‘is’ nothing else but a state (for the respective examples from English scholarly literature, see Connor, Citation1994; for examples from German scholarly literature, see Marko, Citation1995, pp. 37–56).

Second, the conceptual relationships of terms defined through this epistemological and ontological approach—which in particular lawyers in the tradition of positivistic law thinking are trained to apply in Europe to this day—are reified or even naturalized as if they are material things in the world (see, in particular, Marko, Citation2019, pp. 31–32).

And third, even if such terms and concepts are understood as ‘ideal types’ in the tradition of Max Weber’s sociological approach, they are frequently dichotomized, if, for instance, ethnicity and therefore the difference between ethnic groups or ‘civilizations’ are declared the root-cause of violent conflict as this is presupposed in the (in)famous book title of the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ (Huntington, Citation2011).

When the term civic is frequently used in scholarly literature, this seems to be expressing the reference to territory instead of culture or ethnicity and therefore the notion of a culture- and ethnicity-free ‘political community’ or society, thereby ending up in civic versus ethnic, private versus public, and political versus cultural dichotomies which, however, characterize the ideologies of nationalism as well as liberalism (Marko, Citation2019, pp. 96–136). The most important indicator for a differentiation between all these nominal definitions is the reference to the purported inclusiveness of civic-national political claims and institutional settings against the permanent exclusiveness of ethno-national claims and institutional arrangements. However, as this has been demonstrated in the quotations above, also liberal nationalist philosophers claim that a purportedly existing ‘people-nation’ with a ‘higher-level identity’ has a right to ‘full control’ of the territory of the entire state. And as I have shown with regard to the spiral of conflict between the Spanish central government and the Catalan independence movement in more detail elsewhere, mutually excluding sovereignty claims—not only adjudicated by the Spanish Constitutional Court but also expressed by the self-proclaimed civic-nationalist Catalan independence movement—cannot be managed, let alone resolved by judicial fiat (Marko, Citation2019, pp. 120–128). Seen from this context then is the conclusion that also civic nationalism is in no way inclusive by definition when also requiring ‘full control’, that is, sovereign power over a given territory exercised against all others who do not want to bend to this absolutist claim.

In conclusion, the ‘central question … how to manage deep diversity’ (Gagnon, Citation2019, p. 86) with regard to the conceptualization of multinational federalism remains an unresolved problem and cannot be clarified as long as the epistemological and methodological problems in theoretical modeling and empirical testing remain trapped in the ideological presumptions of the European ‘meta-theory of identitarianism’ (Malešević, Citation2006, p. 4) with the consequence of the elimination of all forms of pluralism.

A New Approach: The Concept of Multicultural Federalism

What follows from the analysis of the civic–ethnic–national oxymoron in the section above? The first conclusion we must draw is to recognize the fact that all conceptual efforts in the tradition of the normative-ontological approach remain trapped not only in Kohn’s dichotomy but also in the liberal-national ‘myth of neutrality’ of state and law as we could observe from nationalist identity fictions and dichotomizations of social relationships quoted above. As long as a majority population is seen to represent ‘the whole’ (nation) in possession of state and law, not only authoritarian nationalism but also the liberal-democratic majority principle leads to permanent political domination and the creation of ‘structural minorities’ never in the position to effectively represent and protect their (socio-economic) interests always embedded in their (socio-cultural) identities.

Second, in order to be able to overcome the civic–ethnic–national oxymoron stemming from both nationalist and liberalist ideological doctrines, it is necessary to overcome the disciplinary isolation between philosophers, lawyers and social scientists when they study the same phenomena and problems and to develop an interdisciplinary approach, in particular, with the effort to take the interrelationship of law and sociology seriously (Marko, Citation2019, pp. 138–162). Seen from this perspective, ethnicity must not be understood any longer as a material-biological property of persons, institutions or territories as the twin-ideologies of racism and nationalism proclaim or the short-hand use of the term ‘ethnic group’ or ‘Republic of … ’ may give the impression. Ethnicity must rather be conceived as an empirical process of group formation through social organization and institutionalization. Thereby, symbolic ‘boundary drawing’ (Barth, Citation1969; Wimmer, Citation2013) between situatively changing loose ‘groupings’ of people (Brubaker, Citation2004) without membership conditionality leads to ‘social closure’ (M. Weber) so that fixed and controlled borders between ‘groups’ of people come into existence. In the end, individual persons understand themselves as members of a group with a collective identity and orient their behavior accordingly. These empirical processes are called ‘ethnification’ of socio-cultural relations and may, but need not necessarily lead to an antagonistic polarization of societies. Sociologically seen, therefore, all the ideological dichotomizations, in particular, the civic–ethnic distinction, are supposed to hide the normative claim for sovereignty of a group, whatever it is called. It is therefore always the sovereignty(-as-indivisibility) dogma and claim with reference to one’s own unique, special nation which politically creates mutual exclusiveness so that societal we-and-they configurations can be and are transformed into antagonistic us-versus-them relations.

Hence, a social constructivist approach—always analyzing law and legal relations not only through recourse to nominalist definitions but in the context of cultural, socio-economic and political relations—will make clear that

• bounded or ethnic groups or communities are not culturally homogenous by definition as the ideologies of (neo-)racism, nationalism and older theories of communitarianism want us to believe;

• nor are societies internally divided as such, meaning that cultural diversity between groups must automatically lead to exclusive and antagonistic us versus them positions; but

• these are possible empirical consequences of politically driven processes of ethnification and polarisation, within the processes of both social and system integration. (Marko, Citation2019, p. 159, emph. in the original)

For a new effort in the conceptualization of the relationship between multiple forms of diversity and federalism we, therefore, need a new approach based on a social constructivist epistemology and ontology which avoids naturalist fallacies by conflating diversity with difference and culture with ethnicity. Moreover, from a methodological perspective, all the dichotomizations of civic–ethnic, private–public, or universal–particular cannot be overcome by simply transforming dichotomies into scales with two extreme poles. Central research questions, already addressed in the first section above, cannot be clarified this way: Are federalism and consociationalism and power sharing arrangements either doomed to fail from the very beginning as their critics, following from the notion of a ‘slippery slope’ due to ‘inherent’ centrifugal forces, argue? Or is multinational federalism the only way to hold deeply divided societies together as advocates of accommodation through corporate or liberal power sharing are convinced of? Simply translating the civic–ethnic dichotomy into a continuum for empirical research does only lead to the conclusion that ‘every form of nationalism has elements of civic and ethnic nationalism’ (Berger, Citation2007, p. 8) so that all states would be, in the end, either ‘hybrid’, ‘complex’, or sui generis political systems. Such an approach will not be helpful for empirical research—in particular when exercised in the form of small-N case studies—because this does not allow to draw comparative conclusions. Nor would this be helpful for legal and political consulting in processes of conflict management as the author of this paper could experience himself in Bosnia–Herzegovina and Cyprus.

It is therefore necessary to recognize, first, that also the dichotomy of inclusion-exclusion cannot properly represent possible ideal-typical social relations, because both inclusion and exclusion are Janus-faced: Only the openness of personal attitudes and thus symbolic boundary drawing by groupings without complete social closure allows for multiple identities and thus the possibility of ‘multiple integration.’ Social closure and inclusion can, however, lead either to a claim for ‘upward assimilation’ into the dominant majority culture or to the consequence of remaining trapped in ethnic ghettos in terms of ‘downward assimilation.’ Whereas hyphenated identities of persons and the co-existence of groups remain possible so that cultural boundaries remain permeable in both directions as long as symbolic boundary drawing does not lead to the strict ethnification and polarization of societies, strict social closure on the basis of ascribed identities will then lead to more or less automatic and complete exclusion, and thus to institutional segregation and/or territorial separation (Marko, Citation2019, pp. 417–418).

Hence, against both liberals who want to relegate culture to the private realm and nationalists who conflate culture with ethnicity, the concepts of culture and multiculturalism shall remain a necessary point of reference for the (re-)conceptualization of federalism and consociationalism and their comparative study. Only when we triangulate the civic–ethnic or political–cultural dichotomies through reference to a multicultural society as analytical, third perspective, are we able to overcome the civic–ethnic–national oxymoron and can empirically test the processes of ethnification or de-ethnification of societies in new light.

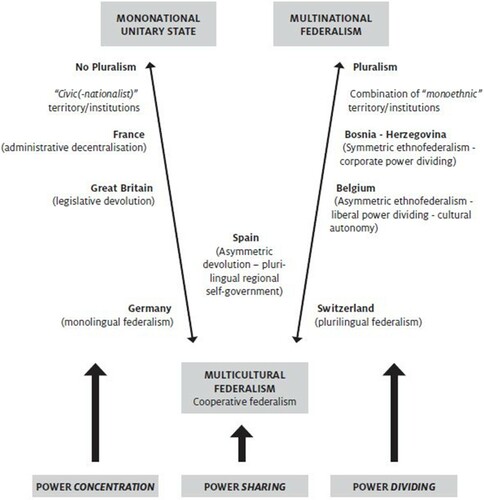

The final graph below () is therefore a first effort to make the method of triangulation with the conceptualization of an analytical model of ‘multicultural federalism’ graphically visible trying to avoid all the epistemological and ontological traps of nominal definitions following from the history of ideas and politics of state formation and nation building in Western and Central Europe outlined in the first section. This (re-)conceptualization is based on three models of institutionalization of power relations, i.e. the centralization and concentration of power in terms of central or unitary states; and the models of power sharing and power dividing, following from different types and forms of power allocation in federal systems. However, as our literature review in the second section made obvious, the identification of the binaries unitary state—federal system and mono-national—multi-national systems do not neatly overlap with the civic—ethnic distinction. The new graphic representation with examples of countries closer to the respective ideal-type in the triangle shall in particular make the distinction between a multi-national federation and a multi-cultural federation visible which cannot be captured by calling them ‘holding together’ or ‘forced together’ federations in contrast to ‘coming together’ federations.

This new graphic representation shall therefore make processes of ethnification and possible de-ethnification visible as this is indicated by the arrow between the angles of multi-national and multi-cultural systems. In institutional terms, multi-national systems are composed of mono-ethnic regions and institutions allegedly representing the more or less complete societal division into mono-ethnic groups so that minorities of all kinds are frequently excluded from effective political participation. As a consequence, the institutions at the federal level are then composed through the combination of mono-ethnic factions in and of state bodies (such as second parliamentary chambers). As can be seen from empirical studies mentioned above, they are functioning not in terms of a positive elite consensus to find compromises in a democratic process of political deliberation and decision-making. Instead, based on a negative elite consensus of divide and rule, they follow the logic of strict power dividing, i.e. institutional segregation to uphold the societal ‘segmental autonomies’ as this has euphemistically been termed by Lijphart.

In contrast, the model of multi-cultural federalism would prevent this logic of power dividing through institutional segregation and territorial separation and allow for the governance of multiple and diverse collective identities of groups in common institutions through power sharing and cooperation without the elimination of cultural diversities within and between groups. Hence, this model does not require to give up diverse identities and to either assimilate into a mono-ethnic culture and mono-national state or keep societies and state bodies strictly segregated as this is the underlying premise for multi-national federations. Nor is the model of multi-national federalism appropriate to overcome the central question how to keep a state and society (peacefully) together against the permanent political mobilization of people (singular!) by nationalist-populist leaders of all sorts.

In conclusion, the efforts of re-conceptualization for a model of multi-cultural federalism shall help to provide a new theoretical lens for both lawyers and political scientists working in the fields of comparative constitutional law, comparative government and comparative politics in their normative and/or empirical studies of many of the countries mentioned in this article.

References

- Barth, F. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of cultural difference. Allen & Unwin.

- Berger, S. (2007). Narrating the nation: Die Macht der Vergangenheit. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 1 (2), 7–13.

- Böckenförde, E. W. (1991). Recht, Staat, Freiheit. Studien zur Rechtsphilosophie, Staatstheorie und Verfassungsgeschichte. Suhrkamp.

- Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity without groups. Harvard University Press.

- Buhi, J. (2019). Constitutional asymmetry in the People’s Republic of China: Struggles for autonomy under a communist party-state. A country study of constitutional asymmetry in China. In P. Popelier & M. Sahadžić (Eds.), Constitutional asymmetry in multinational federalism. Managing multinationalism in multi-tiered systems (pp. 105–135). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burgess, M. (2006). Comparative federalism. Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Connor, W. (1994). Ethnonationalism. The quest for understanding. Princeton University Press.

- Elazar, D. (1985). Federalism and consociational regimes. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 15(2), 17–34.

- Elias, N. (1997). Über den Prozeß der Zivilisation. 2 Vols. Suhrkamp.

- Erk, J., & Anderson, L. (2009). The paradox of federalism: Does self-rule accommodate or exacerbate ethnic divisions? Regional & Federal Studies, 19(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560902753388

- Gagnon, A.-G. (2019). Competing claims for federalism in complex political settings. A Canadian Exploration. In A. López-Basaguren & L. E. San-Epifinado (Eds.), Claims for secession and federalism (pp. 85–96). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Hulsey, J., & Keil, S. (2019). Ideology and party system change in consociational systems: The case of non-nationalist parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25(4), 400–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2019.1678308

- Huntington, S. (2011). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. Simon & Schuster.

- Jennings, I. (1956). The approach to self-government. Cambridge University Press.

- Kantorowitz, E. H. (2016). The King’s Two bodies. A study in medieval political theology. Princeton University Press.

- Keil, S. (2016). Multinational federalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Routledge.

- Kelsen, H. (1925). Allgemeine Staatslehre. Duncker & Humblot.

- Kembayev, Z. (2018). Development of Soviet federalism from Lenin to Gorbachev: Major characteristics and reasons for failure. Review of Central and East European Law, 43(4), 411–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/15730352-04304003

- Kohn, H. (2005). The idea of nationalism: A study in its origins and backgrounds. Transaction.

- Kostakopoulou, D. (2006). Thick, thin and thinner patriotisms: Is this all there is? Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 26(1), 73–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqi045

- Kraus, P. A. (2017). Democratizing sovereignty: The “Catalan process” in a theoretical perspective. In P. A. Kraus & J. Vergés Gifra (Eds.), The Catalan process. Sovereignty, self-determination and democracy in the 21st century (pp. 99–119). Generalitat de Catalunya. Institut d'Estudis de l'Autogovern.

- Kremyanskaya, E. A. (2019). Constitutional asymmetry in Russia: Issues and developments. A country study of constitutional asymmetry in the Russian Federation. In P. Popelier & M. Sahadžić (Eds.), Constitutional asymmetry in multinational federalism. Managing multinationalism in multi-tiered systems (pp. 399–427). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kymlicka, W. (2000). Federalism and secession: At home and abroad. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, 13(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0841820900000400

- Loughlin, M. (2005). The functionalist style in public law. University of Toronto Law Journal, 55(3), 361–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/tlj.2005.0020

- Maiz, R. (2000). Democracy, federalism and nationalism in multinational states. In W. Safran & R. Maiz (Eds.), Identity and territorial autonomy in plural societies (pp. 35–60). Frank Cass.

- Malešević, S. (2006). Identity as ideology: Understanding ethnicity and nationalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marko, J. (1995). Autonomie und integration. Rechtsinstitute des Nationalitätenrechts im funktionalen Vergleich. Böhlau.

- Marko, J. (2013). Defective democracy in a failed state? Bridging constitutional design, politics and ethnic division in Bosnia and Herzegovina? In Y. Ghai & S. Woodmann (Eds.), Practising self-government: A comparative study of autonomous regions (pp. 281–314). Cambridge University Press.

- Marko, J. (2019). Human and minority rights protection by multiple diversity governance. History, law, ideology and politics in European perspective. Routledge.

- Miller, D. (2001). Nationality in divided societies. In A.-G. Gagnon & J. Tully (Eds.), Multinational democracies (pp. 299–318). Cambridge University Press.

- Minow, M. (1990). Making all the difference: Inclusion, exclusion, and American Law. Cornell University Press.

- Norman, W. (2006). Negotiating nationalism: Nation-building, federalism, and secession in the multinational state. Oxford University Press.

- Palermo, F., & Kössler, K. (2017). Comparative federalism. Constitutional arrangements and case law. Hart Publishing.

- Pons Parea, E. (2013). The effects of the constitutional court ruling 31/2010 dated 28 June 2010 on the linguistic regime of the statute of Catalonia. Catalan Social Science Review, 3, 67–92.

- Popelier, P., & Sahadžić, M. (2019). Constitutional asymmetry in multinational federalism. Managing multinationalism in multi-tiered systems. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Requejo, F. (2006). Federalism in plurinational societies: Rethinking the ties between Catalonia, Spain and the European Union. In D. Karmis & W. Norman (Eds.), Theories of federalism. A reader (pp. 311–320). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sahadžić, M. (2019). Mild asymmetry and ethnoterritorial overlap in charge of the consequences of multinationalism. A country study of constitutional asymmetry in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In P. Popelier & M. Sahadžić (Eds.), Constitutional asymmetry in multinational federalism. Managing multinationalism in multi-tiered systems (pp. 47–75). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sanz Moreno, J. A. (2019). The myth of ontological foundations and the secession clause as federal answers to national claims of external self-determination. In A. López-Basaguren & L. Escajedo San-Epifinado (Eds.), Claims for secession and federalism (pp. 347–367). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1985). Die Politikverflechtungsfalle: Europäische integration und deutscher föderalismus im Vergleich. Polititsche Vierteljahresschrift, 26, 323–356.

- Smith, A. D. (2019). Nationalism: Theory, ideology, history (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Tully, J. (2001). Introduction. In A.-G. Gagnon & J. Tully (Eds.), Multinational democracies (pp. 1–33). Cambridge University Press.

- Weber, E. (1976). Peasants into Frenchmen: The modernization of rural France, 1870-1914. Stanford University Press.

- Wimmer, A. (2013). Ethnic boundary making: Institutions, power, networks. Oxford University Press.

- Woelk, J. (1999). Konfliktregelung und Kooperation im italienischen und deutschen Verfassungsrecht. Nomos.