Abstract

The article demonstrates broad variation regarding what is considered to be at the ‘core’ of Sámi ethnicity by different people. The differences are here typologized as kinship-, culture- or community-based ‘foundations’ for Sámi ethnicity. Ideas about individual Sámi ethnicity tended to focus on individual traits more than individuals’ social relationships. This may be influenced by non-Sámi authorities’ focus on individual descendancy, but also by certain aspects of modern Indigenous politics. The article discusses the distinction between relational and individual foundations for ethnicity, pointing to their interconnectedness. It also discusses the difference between genetics and kinship, and potential consequences of a genetics-focused definition of Sáminess.

1. Introduction

Who may be accepted as belonging to an Indigenous people? This question fuels widespread and sometimes heated debates. Some debates concern which criteria should be set for formally registering as Indigenous, other debates concern what are appropriate foundations for personally identifying as Indigenous. The first type of debates affects the latter—and vice versa—but the two nevertheless spring from different questions and ultimately, there are different things at stake. To be denied formal registration is not the same as being excluded from the group—for example, an electoral roll may not be constituted by the entire national demos, but is delimited by factors such as age, settlement history, or criminal history. Debates about personal identity and acceptance are arguably more fundamental for the group: they ultimately concern which traits unite the group and set it apart from others and, as shall be argued, they may affect what status the group is recognized as having.

This article concerns individual reasons for personally identifying as part of an Indigenous people, the Sámi. It is based on interviews and media studies made in Norway, one of the states where the Sámi are Indigenous. The article discusses the relationship between individual and relational foundations for ethnic identity, some different meanings and consequences of referring to ‘genes’/‘DNA’ as a foundation for one’s ethnicity, and the roles of kinship, culture, and community for Indigenous identity.

2. Sámi Definitions and Foundations for Sáminess

2.1. The Maintenance of Grouphood

What is a group? One may differ between two distinct views: (a) a set of individuals with observable commonalities, (b) a set of individuals that identify as part of the group (Jenkins, Citation2008). This article takes the latter view as its point of departure: that ethnic groups are fundamentally identity-groups created through social interaction.

This viewpoint is incompatible with the view that ethnicity is the same as genetic descendancy, which constitutes an extreme variant of the other view of grouphood. Tallbear (Citation2013) criticizes the conflation of genes and ethnos, using Haraway’s apt term ‘gene fetishism’ for it, but she does not describe biology as entirely irrelevant for ethnicty—f. ex. she argues that a Native American tribe is ‘not, strictly speaking, a genetic population’ but ‘at once a social, legal, and biological formation’. The article at hand builds upon a view that biology is not necessarily a fundamental ‘building block’ for ethnicity at all: both formal and informal ethnicity is seen here as constituted by social practices. However, for any substantial number of individuals to consider membership in a group as a core part of their identity, it is necessary for a discourseFootnote1 to be maintained that articulates the group exists and is relevant (Gaski, Citation2008; Kaufman, Citation2001), and such discourses do refer to certain foundations for that ethnicity—commonalities between individuals—and among such commonalities, we may, or may not, find genetic heritage.

This article constitutes an exploration of what different people hold to be foundations for Sámi ethnic identity.

2.2. Formal Criteria for Indigenous Ethnicity: The Case of the Sámi

Since there is a relationship between what formal criteria are set for registration as Indigenous and the broader discourses on what serves as the basis for Indigenous ethnicity, the article will address some aspects of ‘formal Sáminess’ before moving on to the article’s main subject.

If we base our definition of Indigeneity on ILO 169, it can be summed up that to be an Indigenous people is to have been subjugated by the state of another people in one’s own homeland, and to have survived this process but to remain under the dominance of the other people’s state (Berg-Nordlie et al., Citation2015). Colonial states have long regulated who are to formally be considered members of ‘their’ Indigenous peoples, utilizing definitions that have often reflected the dominant ethnos’ view of the Indigenous more than the Indigenous people’s own pre-colonial ideas about who they are (Andersen, Citation2015; Beach, Citation2007; deCosta, Citation2015; Sokolovskiy, Citation2011). deCosta (Citation2015) distinguishes between three basic approaches used by contemporary states to determine Indigenous group membership: descent-based requirements, culture-based requirements (defined broadly as encompassing both individual cultural traits, socio-economic practices, and participation in ethnic communities) and self-definition (Indigenous communities determining membership rules).

As a people divided between four different states, the Sámi are subjected to different approaches. In Russia, the Sámi are considered one of many ‘Native, Small-Numbered Peoples of the North’, a category based on demographic and socio-economic traits as well as collective self-identification. At the individual level, the only opportunity to formally declare one’s Sáminess, or membership in any other Indigenous group, is to write this in the ethnicity column of official censuses. A planned registry of Indigenous citizens has been met with concerns, among others because individuals will need to provide documentation of descent, and be connected to specific areas or rural traditional economic activities. Such demands reflect dominant-group ideas about certain types of descent and culture as essential for Indigeneity (deCosta, Citation2015; Murashko & Rohr Citation2020; Zmyvalova, Citation2020).

The Nordic states Finland, Norway, and Sweden have not registered individual ethnicity in their censuses since World War II (Pettersen, Citation2011), and hence lack registries of Sámi citizens. However, all three states have Sámi Electoral Registries (SERs) that are open for individuals above the age of 18 who fulfill certain criteria. SER membership gives no individual rights except voting and running for elections to Sámediggis (‘Sámi Parliaments’), official organs that advocate Sámi interests, participate in policymaking through various channels and arrangements, and have some devolved decision-making authority.

The Nordic states’ SERs have different entry criteria (Berg-Nordlie, Citation2015; Josefsen et al., Citation2015; Mörkenstam, Citation2002). To enter Norway’s SER you must fulfil a subjective criterion (declaring your identity as a Sámi), and one out of several possible objective criteria which are a mix of what deCosta calls descent-based and cultural individual traits. One objective criterion is purely linguistic (you spoke Sámi in your home as a child), while the other objective criteria can be categorized as linguistic-genealogical (one of your parents/grandparents/great-grandparents must have fulfilled the purely linguistic criterion) or registry-genealogical (one of your parents are in SER) (Pettersen, Citation2015). Importantly, ‘genealogical’ is not the same as ‘genetic’—it is fully possible to be a descendant through adoption.

In Sweden and Finland, the linguistic-genealogical criterion is one generation closer to the individual (i.e. parent/grandparent). In Finland, there are also more liberal registry-genealogical criteria that enable individuals to register based on distant ancestors’ registration as Sámi in official documents. This makes Finland the state with the most liberal approach on paper, but Norway is arguably more liberal in practice due to having an essentially trust-based registration process while the other states have mechanisms for screening and removing applicants (Berg-Nordlie, Citation2015). There have been intense public debates concerning SER entry criteria, particularly in Finland (Joona, Citation2015; Junka-Aikio Citation2016, Citation2016; Laakso, Citation2016). In 2015, a former President of Finland’s Sámediggi quit SER in protest over 93 persons being included in the registry against the Sámediggi’s will (Heikki, Citation2015). In 2016, a debate ensued in Sweden after the Sámi researcher N. J. Päiviö, argued that ‘assimilated Sámi’ had taken over the Swedish Sámediggi due to liberal, descent-based entry criteria.

What knowledge and understanding of Sáminess do you really have if you only have a weak connection to the Sámi world through a grandmother or grandfather? (Päiviö in Nutti et al., Citation2015)

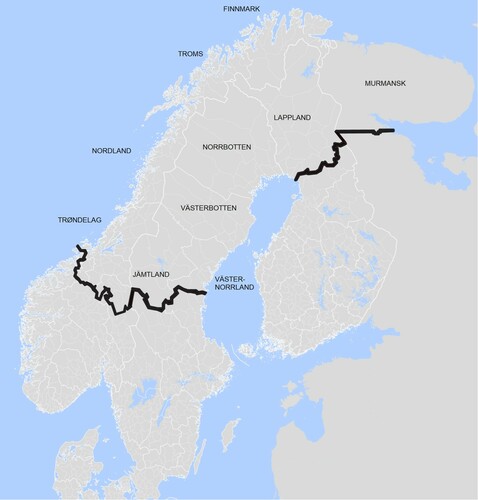

Figure 1. Map showing approximate border of Sápmi (black line) across the states Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, and names of provinces within Sápmi. The Sámi homeland is not formally delineated by any state, and different maps show different borders. The border on this map follows the southern borders of the South Sápmi Sámediggi Electoral Constituency (Norway), Jämtland and Västernorrland provinces (Sweden), Lappland province (Finland), and Murmansk province (Russia). Map made by author utilizing Nordregio.org’s open map source Nordmap.se.

2.3. Sáminess Today and Yesterday

Outsiders’ formal delimitations of Indigenous ethnicity have come to influence many colonized peoples’ own discourses on insiderness and outsiderness (Andersen, Citation2015; Nilsson, Citation2020; Palmater, Citation2011). How much do contemporary self-definitions differ from pre-colonial self-definitions? In the words of Nilsson (Citation2020), in her article about changing Sámi views on Sáminess in Sweden: ‘what is actually left of customary Sámi ways of determining membership after decades of state control and regulations?’

We lack written sources that give an insider’s perspective on Sáminess prior to colonization, but it is possible to propose some likely influences from the colonizing states’ and dominant ethnic groups’ views on Sámi ethnicity. One such possible influence is the accentuation of genetic descent. Colonizing states and the dominant groups’ academic communities have often focused on ‘race’ as a defining aspect of Indigenous group membership, and the Sámi have certainly not been spared this (Dankertsen, Citation2019; deCosta, Citation2015; Kyllingstad, Citation2012; Nilsson, Citation2020). Concepts such as ‘races’, ‘genes’, or ‘DNA’ are not part of any Indigenous group’s traditional self-definitions: these are terms that come from modern scientific terminology—or in the case of ‘race’, from what we now see as pseudo-scientific jargon. A related concept for biological descendancy is ‘blood’. Tallbear (Citation2013) warns against conflating ‘blood’ with ‘genes’/‘DNA’ and demonstrates how terms like ‘blood quantum’ have a history and contemporary practice in the US that puts it apart from ‘genes’/ ‘DNA’. In Sápmi, the term ‘Sámi blood’ is also much older than ‘genes’/‘DNA’ but, unlike in the USA, ‘blood’ is not used in contemporary formal criteria for Sámi ethnicity, and while the term can be found used informally (Dankertsen, Citation2019) it is not as common as what Tallbear describes for US Indigenous nations. Arguably, one may assume that ‘blood’ and ‘genes’/‘DNA’ overlap in colloquial meaning and connotations more in the Sámi case than in the US Indigenous case.

Genealogical descent is on the other hand likely to have been seen as relevant for determining ethnicity also in the past: one cannot ascribe to external influence the view that ethnicity can be inherited from a parent. Still, some possible reasons to ethnically in-group or out-group individuals may fall out of view when genealogy is put front and center. Such factors include for example kinship other than descendancy (for example through marriage); social integration (living and working within the community); and cultural competences and practices (such as language, social norms, arts, lore, technologies, techniques, etc.)

In Sápmi, intermarriage between people with different ethnic backgrounds has been and is common. When we Sámi study our genealogies, we may find outsiders that moved into a Sámi community, married and integrated, and their descendants are still considered Sámi (Fors & Strømstad, Citation2006). This raises some interesting questions about earlier Sámi ethnic definitions. Were ‘first-gen immigrants’ into Sámi communities generally accepted as Sámi, or were only their children broadly considered as such? What if two immigrants married, would their children have been identified as Sámi due to social and cultural integration—or as non-Sámi due to their lack of genealogical Sámi descent? What if an immigrant did not marry locally, but still lived their life integrated in the community? These are questions of relevance for the Sámi of yesterday and today.

Nilsson’s (Citation2020) study of articulations in a Swedish Sámi magazine 1919–1993 found that during this period, emphasis shifted from what she calls a relational understanding of Sáminess to a more individual understanding. The first emphasized being part of a social and cultural community, the other individual rights based on descendancy. Nilsson relates this development to Sweden’s individual descent-based categorization of the Sámi, but also to aspects of modern Sámi Indigenous politics. Of relevance is the SERs’ entry criteria, which is based on the individual applicant’s objective traits, and prominently descent-based traits. Nilsson’s findings are of great interest, although—as she underscores—they do not necessarily reflect attitudes within the entire Sámi people. Also, we cannot know how much the self-descriptions of the Sámi at Nilsson’s early 1900s’ point of departure would resonate with Sámi self-descriptions in the more distant past. This article takes inspiration from Nilsson’s distinction between relational and individual foundations for Sáminess when analyzing attitudes to what constitutes Sáminess in current-day Norway.

Nilsson also mentions two concepts from traditional Sámi society that are of relevance for understanding contemporary Sámi society: laahkoeh and siida. Laahkoeh refers to a terminological system where individuals have specific titles based on their placement in a web of kinship. ‘Laahkoeh’ is a South Sámi word, but the cultural importance of kinship exists across Sámi subgroups (Jernsletten, Citation2000; Nilsson, Citation2020). A siida (North Sámi, sijte in South Sámi) is a community of people who utilize and jointly administer a delimited resource set. When treating laahkoeh and siida as parts of traditional Sámi society, some caveats must be made: Firstly, one should not assume that laahkoeh and siida have always existed in Sámi culture. Sámi society is also subject to change over time, and it is not known exactly when and how these institutions came to be. They are, however, clearly old enough to be called traditional. Secondly, it is not known if outsiders who in older times were included into the kin or local community were also generally accepted as Sámi. Thirdly, the centrality of kin and local community in Sámi culture may wane due to urbanization and economic specialization—although research into urban Sámi identity and community do indicate that ties to kin and ancestral rural communities remain strong among urban Sámi (Berg-Nordlie, Citation2018; Dankertsen & Åhrén, Citation2018).

When analyzing the interview data, special attention has been given to informants’ emphasis of kinship and community-integration as foundations for their and others’ perceived ‘Sáminess’. A third category utilized in analysis is culture, which here refers to knowledges, practices, and worldviews that are considered by informants as being at the core of Sáminess.

3. Methodology

This article is based on interviews performed after an initial period of media studies. It is not a quantitative study with results that say something about the statistical popularity or marginality or the viewpoints presented, but a qualitative study aimed at giving insights into different perspectives on the foundations for Sáminess that exist in the minds of people whose personal identity is connected to this Indigenous people.

3.1. Media Database

During the initial part of the research project, 2015–2017, a database of media texts was compiled from various news sources. The database, which was called Raajah (South Sámi: ‘Borders’) compiled open-access online media articles that contained articulations about who can be considered Sámi and who should be allowed entry into SERs. Texts were gathered predominantly but not exclusively from the Norwegian side of the borders through Sápmi. Languages used were Norwegian, Finnish, Swedish, and Sámi. Initial analysis of these texts informed the preparation for interviews. The database was made openly accessible at https://uni.oslomet.no/sampolraj/. Information about the open database was disseminated through social media, particularly in online communities for Sámi.

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

During the period 2018–2019, 36 semi-structured interviews were performed. The interviewers (see ‘Acknowledgments’ section) had a list of four general questions that guided interviews.Footnote2 These general questions were only used to ‘nudge’ the informant towards addressing certain topics if necessary. The ideal was that informants should be allowed to talk freely and choose what they felt proper to accentuate when discussing Sáminess.

Informants were reached through open calls made on social media, for example, on relevant Facebook groups, and through print and online media articles following researchers’ press releases about the project. Initially, three locations were chosen for physical interviews: A village in the interior of Finnmark County (anonymized as Johka, ‘the River’), a town on the coast of Finnmark County (Luokta, ‘the Bay’), and a city in a part of Norway considered outside Sápmi (Vuemie, ‘the Forest-Valley’). The project was eventually also contacted by informants living elsewhere in Norway. None were rejected. Informants chose the form of interview that they were most comfortable with: some interviews were made physically, some over telephone or video chat, one by writing responses to questions.

The project initially looked for individuals who are out-grouped by some and in-grouped by others, and for individuals who identify as Sámi but are not in SER. Such people have personal experiences of the Sámi ethnic ‘border zones’—formal and informal—and were likely to have reflected on what they see as constituting Sáminess. Calls were made specifically for informants who fulfill the SER criteria but are not SER-registered (coded F1R0), and informants who have a close connection to Sáminess but do not fulfill the SER criteria (F0R0). People with other connection types to the Sámi ethnos and SER also submitted their interest. Among these were also F1R1—people who fulfilled the criteria and were registered. Others were less easy to categorize neatly: Some were uncertain if they should consider themselves as Sámi. Some had a Sámi identity, but suspected that many Sámi would not approve of it. Some did not call themselves Sámi—but displayed strong cultural, social, or genealogical connections to the Sámi people. The commonality between them was that their lives had been characterized in some way that they perceived as important by their personal connection to Sáminess.

3.3. Insiderness, Outsiderness, and Ethics

Research on the Sámi people, as with all Indigenous people, necessitates particular ethical considerations. While academia has also produced results of value for the Sámi, academics were key articulators of the discursive construction that framed the Sámi as a people of lesser ‘racial’ quality, lower physical and intellectual capabilities than the dominant ethnos, and fated to become extinct (Drugge, Citation2016; Olsen, Citation2016; Pedersen, Citation2008). Furthermore, academia was and is guilty of producing research that dominant-group decision-makers utilize for purposes to which Indigenous communities are opposed. Researchers have also often treated Indigenous individuals in ways that violate today’s ethical standards of obtaining free and informed consent. Even when researchers are at their most well-intended, researcher subjectivity affects their choice of subject material, research questions, and analysis. Researchers positioned within the group may have provided other questions, interpretations, and conclusions than those who come from the outside—but research on Indigenous groups is often performed by outsiders (Berg, Citation2000; Olsen, Citation2016).

One should not think that these issues are resolved just because the author is situated on the inside of the group under study.Footnote3 An in-group position may possibly result in research identified as coming from a more ‘recognizable place’ by people in the studied group, but a researcher’s insiderness may also cloud the consciousness among the participants that research is taking place, which negatively affects the fulfilment of informed consent. To facilitate informed consent, full disclosure of the project’s background, research questions, and planned output were provided to potential interviewees, and interviewees were given the opportunity to ask further questions about the project (Túnon et al., Citation2016). Informants were informed that they may withdraw their interviews from the project at any time, and were promised anonymity.

Informants and interviewers from the same ethnic group may have cultural commonalities that reduce the chance of miscommunication, but being of the same ethnicity does not entirely remove the risk. To avoid misunderstandings stemming from dissimilar definitions of key concepts, follow-up questions were often used to clarify the content of, for example, ‘genes’, ‘DNA’, ‘blood’, ‘kinship’, ‘culture’, etc. This provided a clearer understanding of what was actually implied, for example when informants discussed ethnicity using biological concepts.

4. Three Questions About Sáminess

4.1. Kinship: Is Sáminess ‘All in the Family’?

4.1.1. Genetics or genealogy?

During the last decades, results from DNA research have trickled into the public debate, but they have often been filtered through a discourse colored by biology-based views on ethnicity. For example, an article by the Norwegian public broadcasting company’s Sámi section (NRK.no, Citation2009) tells us in the headline that ‘The Sámi are from Northern Spain’. The basis for this statement is that certain haplogroups have been found among individuals classified as Sámi by genetic researchers. The article oversimplifies the genetic background of the Sámi, who like most ethnic groups include people with diverse genetic backgrounds, and conflates ethnicity with genetics. A culture-based view on ethnicity would have yielded the less surprising headline ‘The Sámi are from Northern Europe’, since it is in that region that different cultural impulses merged and developed into the Sámi culture. The conflation of Sáminess with ‘genes’ or ‘blood’ is controversial. It calls forth memories of when proponents of ‘scientific racism’ claimed the Sámi to be a lesser ‘race’ (Kyllingstad, Citation2012, Citation2014). Gene-ethnos conflating discourse has also been adopted by current activists hostile to Sámi Indigenous rights and institutions (Handegård, Citation2016; Svala, Citation2020). For example, in 2009 an organization for landowners in the Røros (Plaassje) area accused a local reindeer herding family of not actually being Sámi, because

These are people of very high intelligence, an IQ far beyond other families in the village, a large share of them have university educations. Genetic testing should be administered. (Quoted in Fjellheim, Citation2017)

A different result of the meeting between the gene-ethnos conflation and the knowledge of northern multicultural unions, is to identify as a member of all the ‘ethnicities’ that one reads into one’s genetic background. This variant of the gene-ethnos conflation is not antagonistic to the idea that people should call themselves Sámi—quite the opposite—but is still experienced by some as provocative, for some of the same reasons that ‘evocations of métissage’ are controversial in Canada (Gaudry & Leroux, Citation2017): Gaudry and Leroux describe the emergence of movements that claim descendancy, no matter how distant, as an adequate basis for Indigeneity, and how this causes conflict with Canadian Indigenous people who consider that there are social and cultural aspects to their ethnicity, not just biology.

Some informants brought up genes as an important foundation for their Sáminess, but it turned out that it was not common for them to hold that ethnicity and genetics are the same. One person from a Norwegianized family whose’ Sámi background had been hidden from them until recently, explained how DNA testing had been part of reconnecting with their heritage.

It was sort of a process. To accept that this was how it was. It was strange, because I hadn’t been allowed to know. That there was such an amount of Sáminess [in the family]. So it was, that I looked at this gene stuff, and ‘ok, there it is’. And that was sort of an evidence for myself. (‘Kim’, South Norway, F1R1)

The popularity of DNA testing may partially be a result of Norway’s prior policy against the Sámi, during which many began to ‘pass’ as non-Sámi and hid their Sáminess from their children. The effect is that many lack knowledge of their Sámi genealogical heritage. Those who try to find out may encounter hostility from family members, and elders may be uncooperative when questions about Sámi ancestry are posed. Lacking oral sources, the open Norwegian historical population databases could be an alternative, but many do not know how to find their ancestors and their ethnicity in these databases, and in any case old population data in some cases ‘hide’ Sáminess, so that research will not necessarily be conclusive (Evjen, Citation2008; Hansen, Citation2015). In the face of such obstacles, the DNA testing industry offers an attractive shortcut to check for well-buried Sámi roots.

Some of the informants who were of non-Sámi genealogical background but socially or culturally integrated, stated that their ‘genes’ ultimately rendered them non-Sámi, no matter what they did:

Q: If someone has grown up in [Johka], but is not of Sámi kin, can they be a Sámi?A: No.Q: Why not?A: They probably don’t have the right genes. But in the old days when people moved in, both Finnish and Norwegian was mixed into the old families. (‘Hanne’, Johka, F0R0)

If you don’t speak Sámi then you don’t have the Sámi way of thinking, that too is lost. The Sámi way of seeing things and saying things. And then, there is no longer any difference between a Sámi and a Norwegian. Then it’s just the genes, and that isn’t important. Nobody asks what genes you have, they ask how you live. (‘Issát’, Johka, F1R0)

So I’m thinking that there has to be something genetic, but that one also has to have something to do with the culture. And then, preferably, the language (‘Kim’, South Norway, F1R1)

Q: What makes a person a Sámi?A: Mother and father. If mother and father are Sámi, then you are a Sámi. If they aren’t, then you aren’t. Biology. Plain and simple. It’s in the blood (…)

Q: What about adopted children of Sámi, are they Sámi?A: They are culturally Sámi, but not biologically. When one is adopted, then one is taken fully into a culture. I consider them to be Sámi. (‘Gunnar’, Abroad, F1R0)

… I say they [adopted children] are fully qualified. It’s not genes in a literal sense, but that you have a Sámi family. It doesn’t have to be the scientific genetic definition. [author’s emphasis] (‘Kim’, South Norway; F1R1)

4.1.2. The centrality of kinship

Genealogy and family history are important in Sámi culture. It is a common casual conversation subject among Sámi, particularly when meeting for the first time (Jernsletten, Citation2000). In the words of someone raised in a Sámi community but without Sámi genealogical ancestry:

Norwegian, that means having a Norwegian passport. But Sámi, then you have a Sámi family. You are of Sámi kin (…) People are very preoccupied with kin. Even the first thing people ask [you] about is [your] kin. So it’s confusing that I speak Sámi. I don’t fit in. But in daily life, among my mates, that was never an issue. It’s more when you meet new people. (Hallvard, Vuemie, F0R0)

There are also those who opine that descendancy is not the only form of kinship that can constitute a foundation for Sáminess. A recurrent issue in Sámi public debate is whether a person with no Sámi descendancy can become Sámi through marriage. If we are to look at attitudes to formal registration as an indicator, we find that survey-based studies of selections of SER-members in Norway revealed that only 22% wanted more liberal SER criteria—but given that the criteria were to be changed, 42% of respondents favored that spouses of SER-registered people should be able to register (numbers from 2017; in Pettersen & Saglie, Citation2021). At the informal level, an originally non-Sámi spouse may be considered Sámi by some due to their integration into the community, or through cultural integration, but also through a definition of kinship that includes marriage. After all, a person who marries a Sámi does become part of a Sámi family.

Informants differed regarding whether they thought spouses were, or should be, accepted as Sámi. This difference reflects more and less ‘liberal’ attitudes to the integration of spouses not just individually but also in different social millieus. Furthermore, there are different levels of acceptance for spouses living a Sámi life (i.e. behaving like Sámi, producing and practicing Sámi culture) vs. calling themselves Sámi. The former is much more accepted. It is possible to be integrated and get general acceptance for your Sámi life, and yet simultaneously it may not be accepted that you ‘check the final box’ and call yourself a Sámi. Whether or not this is seen as a problem varies between different individuals: for some it is unproblematic, for others it constitutes a sore issue, a persistent feeling of not being completely accepted.

… society isn’t shut or unhospitable, neither the Norwegian nor the Sámi society. But you can’t really get on the inside of the Sámi society unless you’re there to begin with. I don’t think you’ll really get on the inside, even if you marry in. (‘Anna’, Johka, F0R0)

The denial of registration is experienced by some spouses as symbolic of an ultimate denial of total integration into the Sámi community.

My mother (…) has been fully accepted in the Sámi community, but always felt outside precisely because of the voting rights, and also the fact that many keep fishing for exactly where her blood ties come from, as if that’s the only thing that ultimately matters. (…) If I’m to be honest, I really think it’s sad, old-fashioned and destructive for Sámi language/culture to make all distinctions based only on ‘race’ and not allow entry for all those activists who belong among us and who keep Sápmi alive. Those who are Sámi in the heart, but not in the DNA.Footnote4

4.2. Culture: What Is It to Be Culturally Sámi?

Several informants gave voice to the notion that cultural competence is of prime importance to call yourself a Sámi. But what is Sámi culture? When asked, informants highlighted different things.

4.2.1. Knowing the language

Sámi language competence is often considered an important cultural marker. Indeed, important enough that many did discuss it as something entirely separate from ‘culture’. It is nevertheless here treated analytically as a part of the broader category ‘culture’.

While some hold that language is a necessary condition for Sáminess, this opinion varies from person to person, and from place to place. In many parts of Sápmi, such as the South and most of the Coast, policies and processes of linguistic assimilation have destroyed Sámi language competence to such an extent that most people of Sámi descendancy are non-speakers (Beach, Citation2007; Minde, Citation2003). In Sámi majority-language areas such as Johka, people are more likely to see language competence as necessary.

In 2017, the language issue ‘exploded’ in Norwegian Sámi public debate. For the first time in history, the traditional New Year’s Speech of the Sámediggi President was held in Norwegian. The then-President, V. Larsen (Labor) is of a linguistically Norwegianized Sámi family, and addressed the language issue in her speech:

Particularly through my children I am reminded of the gift that the ‘language of the heart’ is. It gives them access to the wisdom and secrets hidden in the words. The language is identity, culture, and community. At the same time, our family is a typical image of the Sámi society. We are of the same flesh and blood, but also different. Some are able to speak Sámi, others are not. Nevertheless we are one Sámi family who belongs together. (Måsø & Boine Verstad, Citation2017)

It was awful. I couldn’t watch. Instead, I had to go read the speech on the internet afterwards. (…) It felt like a violation against myself. (Sámi teacher, quoted in Bye & Jørstad, Citation2017)

Look at when the Sámediggi President held her New Year Speech in Norwegian. She didn’t have a Sámi language and felt most comfortable holding the speech in Norwegian, and it created such a controversy. That wasn’t very generous. I experienced it as discrimination. (‘Ruth’, Luokta, F1R1)

4.2.2. Living with and of nature

Some informants saw themselves as having a special relationship with nature and identified this as a key part of their Sáminess. Most of them talked about nature as a place to gather resources, but others also spoke about nature in religious terms. Some readers may see these two views on nature as mutually opposed, but in Sámi tradition it is not so: the Sámi have pragmatically utilized natural resources for survival, but nature has also been worshipped in the pre-Christian Sámi faith. An example of religious language in relation to nature is the following statement:

Much of that which is Sámi in me is that closeness to nature. That I use it and walk in it. I am not a Christian, but I feel that there is something in nature. I feel that there are energies in nature. I walk in nature and pray within myself, and I feel a vast humility for everything out there. (‘Kristine’, Luokta, F1R0)

Food and clothes. To be fed and not cold. That’s the foundation of Sámi culture. When to harvest the food from nature, how to prepare it. How you exploit the resources … (‘Gunnar’, Abroad, 2019, F1R0)

… the kids, you give them love and help them, but they are to be strong. They are to manage alone. They are to be able to do practical things, early, as much as possible. My daughter in Oslo she says ‘those my age [down here], they don’t know how to do anything!’. (‘Kristine’, Luokta, F1R0)

… in my opinion you can’t do Sámi things in a city. I may be wrong. If I’m wrong, I’m glad. But I don’t get how one is supposed to do that. Everything [here] is about how everything costs money. And when you’re a Sámi, you are supposed to be able to live off nature without a big wallet. So I don’t know. (‘Jon’, Vuemie, F1R0)

For some Sámi, nature usage is also the foundation of their personal economy. Reindeer herding, coastal- and river fishing, gathering and hunting are all considered traditional Sámi industries. Reindeer herding is particularly closely associated with Sáminess in Norway, since only Sámi are traditionally involved in it, and in most of Norwegian Sápmi reindeer ownership is legally reserved for people of reindeer-herding Sámi families. During the harshest period of Norwegianization, Sámi reindeer herding communities functioned as important ‘keeps’ for Sámi identity, language, and culture. Coastal fishing is also practiced by non-Sámi Norwegians, but has a history, and an economic and cultural importance, that makes this too part of the backbone of Sámi society.

4.2.3. Carrying the torch of Sámi artistry

An important part of Sámi culture is creative arts—such as duodji (handcrafted tools, clothes, toys and games, etc.), music (particularly the distinctive juoigan or ‘yoiking’), and literature and storytelling. Sámi arts survive into our time through the passing on of traditional knowledge, the gradual changing of old traditions through creative development, and through the emergence of new arts inspired by Sámi tradition (Finbog, Citation2015, Citation2019; Seurajärvi-Kari, Citation2005).

Many informants discussed both the creation and consumption of art as important for their lives as Sámi. Particularly the usage of gákti (a type of traditional clothing) and other clothes or decorations with Sámi elements was underscored as important. For those with little Sámi language competence or connection to traditional Sámi industries, clothes constitute an accessible way of demonstrating one’s Sámi ethnicity.

Sámi traditional and tradition-inspired music has been an important part of the cultural revival, and several informants mentioned their enjoyment of it. The growing popularity of some Sámi artists, musicians, in particular, was also a source of pride in the achievements of one’s people.

When I listen to Nils-Aslak Valkeapää something stirs in my heart, I feel a very special longing (…) It tears in my heart. This is my people. (‘Berit’, Luokta, F1R0)

4.2.4. Can you teach yourself Sáminess?

If culture is seen as being at the core of Sáminess, does this mean that you can become a Sámi by learning the culture? Many would say no, due to the widespread notion that kinship is necessary to be Sámi. Beach (Citation2007) has presented the possibility of a ‘phase-in’ system wherein outsiders may gradually be acknowledged as Sámi across generations, and one informant argued that a formal Sámi ‘citizenship test’ for outsiders should be feasible. It could be argued that the Sámi have an increased risk of dwindling in numbers if ‘phase-out’ is seen as possible, but there is no ‘phase-in’ option.

For those who find that they are of Sámi descent but still feel that this is not enough to call themselves Sámi, it becomes a priority to acquire more knowledge of the culture, to integrate it into one’s life.

I went and got myself a gákti. I have to surround myself with Sáminess. For me, it’s like putting on my identity. I have to surround myself with different stuff. We have a Sámi flag at home. My wife and me, we are together about this project. We both have the Coast Sámi culture and all that entails, with denial and silence from the parent and grandparent generation (‘Børre’, Luokta, F1R0)

… if I’d showed up to a wedding in a dress, people would have been wondering what I’m doing! It’s the most natural thing in the world to use the gákti. (‘Anna’, Johka, F0R0)

Yes, I was a Dáža [non-Sámi] in [Johka]. But when I move out of [Johka] I’m part of the minority again. Because I’m from [Johka] and I speak Sámi. It’s the cultural bit. It makes you immediately different (‘Hallvard’, Vuemie, F0R0)

4.3. Community: When Are You A Part of Sámi Society?

4.3.1. A community of kin and culture

Socialization with co-ethnics was by some informants highlighted as a fundamental part of being Sámi. This is a relational type of foundation for ethnicity, but one may observe some interesting interplays between the possession of individual traits and participation in the community.

As mentioned, the possibility to discuss one’s Sámi genealogy can be an important social ‘ice-breaker’, and hence an individual trait that serves as a key to Sámi social relationships. The Sámi cultural preoccupation with individual genealogy can in itself be seen as transcending the individualistic, if one takes the perspective that the individual through this identifies itself as part of a Sámi kin-community that includes both the living and ancestors. Ancestor veneration was part of the old Sámi faith, and the pervasive interest in genealogy in the Sámi community could be seen at least partly a continuation of this tradition. One may here note the South Sámi concept of maadtoe (‘origin’) as explained by Nilsson (2017; referring to Ween, Citation2005):

maadtoe describes the entire network of mutual rights and responsibilities that an individual possesses through biological and social relations with both living and dead.

Sámi language competence is another individual trait that has a dynamic with community integration. It obviously opens social spaces within the Sámi group—but simultaneously it is largely dependent on social relations, since a language is difficult to learn and practice alone. Artistry is likewise connected to relational practices: Those who want to produce art, must learn, a social process that may involve courses or other forms of congregation. One may attempt to learn traditional arts from textual sources, but even in that case, social media groups dedicated to traditional arts constitute a relational element in the learning- and production process. Those who utilize art produced by others may also enjoy this in social settings—notably at the many festivals, markets and culture houses where Sámi culture is performed, sold, and practiced (Berg-Nordlie Citation2018). Nature-usage is also often a social activity, and can be a gateway to reconnecting with Sámi community:

… it’s in the last decades that I’ve been with the other Sámi, fishing on the river. They invite me to come. So I’ve gotten to know many more Sámi people after that. (‘Ole’, Luokta, F1R1)

Still, the question remains: what is ultimately the most important part of Sáminess—one’s individual traits, or living and working in community and solidarity with co-ethnics? Is the fundamental question ‘what is Sáminess in me’ or ‘what am I in Sáminess’?

4.3.2. A community of locals

One of the most radical statements regarding the relational foundations of Sáminess came from an informant who had moved to Johka. They rejected completely the notion of individual criteria for Sáminess

What is, then, this ‘identity’? Is it that frightfully important? Isn’t belonging more important? (…) [earlier] one hasn’t been all that preoccupied with ‘well, are you a proper Sámi’? Some have married someone in Denmark, moved there and lived a Danish life. Others have married into [village] and lived that life. But now we’re so preoccupied with the individual, ‘who am I’? (‘Josefine’, Johka, 2018, FXFootnote5R0)

Radical refutation of individual identity as the pinnacle of Sáminess has the interesting consequence that, in the final analysis, it could imply questioning the Sáminess of individuals living outside Sámi-identified communities:

Many people from FinnmarkFootnote6 move to the south, they leave it all behind. I don’t know how Arctic they are, then. They could have lived here and contributed, instead of living in Oslo. They’ve failed, then. It doesn’t help, then, that they have a grandmother who was Sámi. (‘Anna’, Johka, F0R0)

4.3.3. Can you immigrate into Sáminess?

If Sáminess is essentially about community integration, does this mean you can become Sámi by joining a Sámi community? The answer to this question, which is intimately connected to the question of Sáminess through cultural integration, depends on who you are talking with and where you are. Informants shared accounts about how in certain communities one could more easily become accepted as Sámi, or at least as ‘associated Sámi’, whereas in other communities this would be impossible. One informant related that while she was not considered Sámi in Johka, her acculturation after a long life in Johka had caused her to be identified as Sámi elsewhere, and targeted with racist behavior:

I’ve walked in [small town, Coastal Finnmark] wearing a gákti, I have, and I’ve had a gang of kids after me shouting ‘Lapp bitch! Lapp bitch! Lapp bitch!’ (‘Hanne’, F0R0)Footnote7

One must respect the ongoing rights’ struggle and not water it out too much. It is more important than little me. It is so much more important than the individual. (‘Bodil’, Vuemie, F0R0)

One interesting response to the question of whether Sáminess could be acquired through acculturation or immigration, was to essentially propose that the term ‘Sáminess’ in reality concealed two different things: ‘being Sámi’ and ‘having a Sámi identity’.

It’s obvious that I’ve been raised in a Sámi environment. But I have no Sámi family. So I don’t consider myself to be a Sámi. But it is of course part of my identity. The culture and the language. (…) Having a Sámi identity, many people can have that. Everything around you becomes part of your identity. Even things you work with become part of your identity, and the people you are with. (Hallvard, Vuemie, F0R0)

5 Conclusion

5.1. Genetics, Ethnicity, and Nationhood

This article takes as its point of departure that ethnicity is a social phenomenon, and not a function of genetic heritage. There are indications that some of those who do identify ‘genes’/‘DNA’ as part of the foundation of Sáminess, do not literally mean that biological descent is necessary, but use these terms as a shorthand for something else: genealogical descent. That said, the gene-ethnos conflation is present in Norwegian public debate on Sáminess.

In the words of Dankertsen (Citation2019), reducing Indigenous ethnicity into ‘mere repositories of DNA’ causes it to be ‘subtly deprived of its subjectivity’. This is akin to Tallbear’s (Citation2013) insight that

‘genetic articulations of indigeneity’ rest on assumptions of certain forms of physical and social death. And those assumptions contradict the analyses and work of indigenous peoples who view their presence as peoples, cultures, land stewards, and sometimes governmental entities as still vital.

The term ‘nation’ has many different possible meanings. One possible definition is that a nation is an ethnic group with organizations or institutions that claim to work for the group’s interests. Such interests may for example be found in the protection of shared culture or community. But what common interests can a group possibly be said to have, if it shares nothing but distant genetic ancestry? It is perhaps not surprising that public debate’s ‘hardline’ gene-ethnos conflation in relation to the Sámi tends to be articulated by people who opine that the Sámi should not be called a nation or even a people, and should not have its own political organs and Indigenous rights.

What then, if the Sámi are solely defined by kinship? If kinship is interpreted as genealogical descent alone, and no limit is set regarding how far back the nearest ancestor defined as ‘Sámi’ can be, does one not run into the same situation that the gene-ethnos conflation creates? What common interests may set such a group apart from others? However, this line of argument attacks a strawman: Firstly, it appears common to hold that there is a generational ‘cutoff’ beyond which Sámi ancestry is not as relevant. It is widely accepted that the SER criteria utilize such a ‘cutoff’, placed at the great-grandparent threshold. Secondly, it is not uncommon to hold that other categories than descent may count as relevant kinship, notably marriage. Thirdly, it appears that many hold kinship alone to not be enough, that something else must also be present, some cultural or community-based foundation for Sáminess.

5.2. The Many Pathways into Sáminess

As this article has shown, informants point to a variety of reasons when explaining what makes them Sámi, and what they find to be acceptable reasons for others to call themselves Sámi.

Kinship is for some the prime foundation of Sáminess. This may reflect the persistence of older Sámi cultural values. There are different opinions about what types of kinship are adequate, and if kinship alone is adequate. There is also some internal disagreement over whether marriage to a Sámi is an adequate form of kinship. Many hold that only genealogical descendancy ‘counts’, a position that may be influenced by states’ and dominant groups’ emphasis on descent as a Sáminess criterion, and by the SERs’ genealogical registry criteria.

For others, culture is at the centre of Sáminess. In this perspective, the Sámi people is constituted by those who carry into the future the ancient, yet always changing, Sámi culture. What aspects of Sámi culture is seen as most central, varies between different people. Arguably, there is a major distinction between those who consider language competence to be a cultural ‘must’, and those who do not. Among the latter, some see language competence as making a person ‘more’ Sámi while others see it as completely peripheral to their way of being Sámi. Other cultural traits articulated as important for Sámi identity is closeness to nature and competence regarding how to use it; and production or utilization of traditional/tradition-inspired arts. While some put culture front and centre, it does not appear uncommon to hold that some form of kinship must also be present.

Finally, community-based definitions of Sáminess emphasize the individual’s place in Sámi society. Nilsson’s (Citation2020) findings from Sweden noted a shift from relations and responsibilities to individuality and rights. The study at hand did not find rights to be brought up that much, but most informants did focus on individual traits—types of kinship, or types of cultural practices. Others again placed community integration at the core. As discussed in the article, individual and relational foundations for ethnicity strengthen one another: social integration facilitates the acquirement of key individual cultural traits, and key individual traits facilitate social integration. Interaction between individual traits and social relations may strengthen or weaken personal ethnic identity, and influence the extent to which a person’s ethnic identity is accepted by others. Regarding kinship as a foundation for Sáminess, it is open for discussion whether this should be considered primarily as a trait of the individual, or primarily as a form of community membership.

Experiences of acceptance or rejection as Sámi has been a recurrent theme in many interviews. Some informants are frustrated when their Sáminess is called into question, while for others, external validation is much less important. What is held to be necessary to achieve general acceptance as a Sámi, varies between individuals and communities. One may also note a distinction between accepting that someone lives like a Sámi (i.e. exhibits cultural and communal integration) and accepting that someone refers to themselves as Sámi. Acceptance of the latter is more likely to be dependent on individual kinship ties. What is certain is that there never will be complete agreement among the Sámi regarding who can call themselves Sámi—after all, there is no ethnic group in which all individuals who consider themselves as part of the ethnos agree completely about what constitutes the borders of the ethnos.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway’s Programme for Sámi Research, Grant number 259421. Thanks to Jo Saglie for constructive feedback and Eva Josefsen for participation in field work. Points of view regarding ethnicity expressed in the article are the author’s own, and the author has sole responsibility for the article’s content.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Discourses’ are here defined as framings of phenomena that are maintained through communicative practices.

2 (1) What is the nature of your connection to the Sámi people. What are your thoughts about your relationship with the Sámi people? (2) How would you describe your relationship to Sámi culture? Is there any part of Sámi culture that is particularly important for you? (3) How is your relationship to the Sámi Electoral Registry? What do you think about the entry criteria? (4) What do you think about the current political situation of the Sámi, and what are your desires for the Sámi politics of the future?

3 If the author had been an informant, he would be coded F1R1.

4 Comment on author’s Facebook page following public lecture at the Oslo Sámi House concerning Sámi insider- and outsider positions, 2019. Permission to quote granted by commenter.

5 Informant stated they may be able to find ancestors that made them fulfil Sáminess criteria, but did not consider it important to check.

6 Norway’s northernmost county. The name comes from a Norse word meaning ‘Sámi Land’, although Sápmi is much larger than Finnmark.

7 ‘Lapp’ is a slur when used by non-Sámi against Sámi.

References

- Andersen, C. (2015). “Metis”. race, recognition, and the struggle for Indigenous peoplehood. UBC Press.

- Aslaksen, E. (2012). Harald Hårfagre kunne stått i samemanntallet. NRK Sápmi, https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/vil-apne-sametinget-for-ikke-samer-1.8375257

- Beach, H. (2007). Self-determining the self: Aspects of Saami identity management in sweden. Acta Borealia, 24(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830701411605

- Berg, B. A. (2000). Mot en korporativ reindrift. Samisk reindrift i Norge i det 20. århundre – eksemplifisert gjennom studier av reindriften på Helgeland. Phd thesis, UiT.

- Berg-Nordlie, M. (2015). Representativitet i Sápmi. Fire stater, fire tilnærminger til inklusjon av urfolk. In B. Bjerkli & P. Selle (Eds.), Samepolitikkens utvikling (pp. 388–418). Gyldendal.

- Berg-Nordlie, M. (2018). The governance of urban Indigenous spaces: Norwegian Sámi examples. Acta Borealia, 35(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2018.1457316

- Berg-Nordlie, M., Dankertsen, A., & Winsvold, M. S. (2021). An urban Future for Sápmi. Indigenous urbanization in the Nordic States and Russia. Berghahn Books.

- Berg-Nordlie, M., & Pettersen, T. (2021). De uregistrerte. Mennesker med samisk tilknytning utenfor Sametingets valgmanntall. In J. Saglie, M. Berg-Nordlie, & T. Pettersen (Eds.), Sametingsvalg: Tilhørighet, deltakelse, partipolitikk. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Berg-Nordlie, M., Saglie, J., & Sullivan, A. (2015). Introduction: Perspectives on Indigenous politics. In M. Berg-Nordlie, J. Saglie, & A. Sullivan (Eds.), Indigenous politics. Institutions, representation, mobilization (pp. 1–22). ECPR.

- Bye, K. S., & Jørstad, M. (2017). Kritisk til presidentens nyttårstale: - Det føltes som et overtramp. NRK Sápmi. https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/kritisk-til-presidentens-nyttarstale_-_-foltes-som-et-overtramp-1.13301328

- Dankertsen, A. (2019). I felt so white: Sámi racialization, indigeneity, and shades of whiteness. NAIS Journal of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association, 6(2), 110–137. https://doi.org/10.5749/natiindistudj.6.2.0110

- Dankertsen, A., & Åhrén, C. (2018). Er en bysamisk fremtid mulig? Møter, moro og ubehag i en bysamisk ungdomshverdag. Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift, 2(6). https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-2512-2018-06-01

- deCosta, R. (2015). States’ definitions of Indigenous peoples: A survey of practices. In M. Berg-Nordlie, J. Saglie, & A. Sullivan (Eds.), Indigenous policy. Institutions, representation, mobilisation (pp. 25–60). ECPR Press.

- Dorries, H., Henry, R., Hugill, D., McCreary, T., & Tomiak, J. (2019). Settler city limits: Indigenous resurgence and colonial violence in the urban prairie west. University of Manitoba Press.

- Drugge, A.-L. (2016). How can we do it right? Ethical uncertainty in Swedish Sámi research. Journal of Academic Ethics, 14 (4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9265-7

- Evjen, B. (2008). Giftermål, næring og etnisk tilhørighet 1850-1930. In B. Evjen & L. I. Hansen (Eds.), Nordlands kulturelle mangfold. Etniske relasjoner i historisk perspektiv (pp. 239–272). Pax.

- Finbog, L.-R. (2015). Gákti ja goahti: Heritage work and identity at várdobáiki museum. Nordisk Museologi, 2, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3050

- Finbog, L.-R. (2019). The duojár: An agent of the symbolic repatriation of Sámi cultural heritage. In J. S. Markide & L. Forsythe (Eds.), Research journeys in/to multiple ways of knowing (pp. 93–102). DIOPress Inc.

- Fjellheim, E. (2017). Dette bildet viser hvorfor min mor ikke snakket samisk til oss barna, Nordnorskdebatt.no. https://nordnorskdebatt.no/article/forsonings-sannhetskommisjon-om

- Fors, K., & Strømstad, A. (2006). Slekter I indre finnmark: De eldste generasjoner. A Strømstad.

- Gaski, L. (2008b). Sami identity as a discursive formation: Essentialism and ambivalence. In H. Minde, H. Gaski, H. Jentoft, & G. Midré (Eds.), Indigenous peoples: Self determination, knowledge, indigeneity (pp. 219–236). Eburon.

- Gaudry, A., & Leroux, D. (2017). White settler revisionism and making Métis everywhere: The evocation of Métissage in Quebec and Nova Scotia. Critical Ethnic Studies, 3 (1), 116–142. https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.3.1.0116

- Handegård, O. (2016). Var samene et urfolk? Nordnorskdebatt.no, https://nordnorskdebatt.no/article/var-samene-et-urfolk

- Hansen, L. I. (2015). Befolkningens etniske sammensetning i Tromsø-området gjennom siste halvdel av 1800-tallet – hva folketellingene forteller – og ikke forteller. In P. Pedersen & T. Nyseth (Eds.), City-Saami – same i byen eller bysame? Skandinaviske byer i et samisk perspektiv (pp. 58–81). ČálliidLágádus.

- Heikki, J. (2015). Ex-presidenten säger upp sin rösträtt i Sametinget. Sameradion & SVT Sápmi. https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2327&artikel=6268385

- Jenkins, R. (2008). Social identity. Routledge.

- Jernsletten, J. (2000). Dovletje jirreden. Kontekstuell formidling i et sørsamisk miljø. Master thesis, University of Tromsø.

- Joona, T. (2015). The definition of a Saami person in Finland and its application. In C. Allard & S. F. Skogvang (Eds.), Indigenous rights in Scandinavia. Autonomous Sami law (pp. 155–172). Routledge.

- Josefsen, E., Mörkenstam, U., & Saglie, J. (2015). Different Institutions within similar states: The Norwegian and Swedish Sámediggis. Ethnopolitics, 14(5), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2014.926611

- Junka-Aikio, L. (2016). Can the Sámi speak now? Deconstructive research ethos and the debate on who is a Sámi in Finland. Cultural Studies, 30(2), 205–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2014.978803

- Kaufman, S. J. (2001). Modern hatreds: The symbolic politics of ethnic war. Cornell University Press.

- Kyllingstad, J. R. (2012). Norwegian physical anthropology and the idea of a Nordic master race. Current Anthropology, 53(5), S46–S56. https://doi.org/10.1086/662332

- Kyllingstad, J. R. (2014). Measuring the Master Race: Physical Anthropology in Norway, 1890-1945. Open Book Publishers.

- Laakso, A. M. (2016). Critical review: Antti Aikio and mattias Åhrén (2014). A reply to calls for an extension of the definition of Sámi in Finland. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 5(1), 123–143.

- Måsø, N. H., & Boine Verstad, A. (2017). For første gang i historien blir nyttårstalen ikke holdt på samisk. NRK Sápmi, https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/for-forste-gang-i-historien-blir-nyttarstalen-ikke-holdt-pa-samisk-1.13290446

- Minde, H. (2003). Assimilation of the sami – implementation and consequences. Acta Borealia Volume, 20(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830310002877

- Mörkenstam, U. (2002). The power to define: The Sámi in Swedish legislation. In K. Karppi & J. Eriksson (Eds.), Conflict and cooperation in the north (pp. 113–147). Umeå.

- Murashko, O. & Rohr, J. (2020). Russian federation. In D. N. Berger, D. Mamo & J. Koch (Eds) The Indigenous world 2019 (pp. 43–51). Copenhagen: IWGIA.

- Nilsson, R. (2020). The consequences of Swedish national law on Sámi self-constitution—The shift from a relational understanding of who is Sámi toward a rights-based understanding. Ethnopolitics Volume, 19(3), 292–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2019.1644779

- NRK.no. (2009). Samene kommer fra Nord-Spania, NRK Sápmi, nrk.no/sapmi/samenes-opprinnelse-funnet-1.6845819.

- Nutti, H., Sarri, T., & Marakatt, L.-O. (2015). Forskare: Sametinget styrs av försvenskade samer. Sameradion & SVT Sápmi, https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2327&artikel=6543807

- Olsen, T. A. (2016). Responsibility, reciprocity and respect. On the ethics of (self-)representation and advocacy in Indigenous studies. In A.-L. Drugge (Ed.), Ethics in Indigenous research, past experiences – future challenges (pp. 25–45). Umeå.

- Ot. Prp. nr. 43. (2007-2008). Om lov om endringer i Sameloven. (Proposition to Parliament on changes to the Sámi Act). https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/4cf124b9ceda425c908cbbbb526e4f38/no/pdfs/otp200720080043000dddpdfs.pdf

- Palmater, P. D. (2011). Beyond blood: Rethinking Indigenous identity. Purich.

- Pedersen, P. & T. Nyseth (2015). City-Saami – same i byen eller bysame? Skandinaviske byer i et samisk perspektiv. Kárášjohka-Karasjok: ČálliidLágádus.

- Pedersen, S. (2008). Lappekodisillen i nord 1751–1859. Fra grenseavtale og sikring av sameness rettigheter til grensesperring og samisk ulykke. Sámi allaskuvla.

- Peters, E., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous in the city: Contemporary identities and cultural innovation. UBC Press.

- Pettersen, T. (2011). Out of the backwater? Prospects for contemporary sami demography in Norway. In P. Axelsson & P. Sköld (Eds.), Indigenous peoples and demography (pp. 185–196). Berghahn.

- Pettersen, T. (2015). The Sámediggi electoral roll in Norway: Framework, growth, and geographical shifts, 1989-2009. In M. Berg-Nordlie, J. Saglie, & A. Sullivan (Eds.), Indigenous policy: Institutions, representation, mobilisation (pp. 165–190). ECPR Press.

- Pettersen, T., & Saglie, J. (2021). Valgt av og blant samer – og enkelte andre? Ulike velgergruppers holdninger til kriteriene for å delta ved sametingsvalg i norge. In M. Berg-Nordlie, J. Saglie, & T. Pettersen (Eds.), Sametingsvalg: Tilhørighet, deltakelse, partipolitikk. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Seurajärvi-Kari, I. (2005). ‘Theatre’. In U.-M. Kulonen, I. Seurujärvi-Kari, & R. H. Pulkkinen (Eds.), The saami: A cultural encyclopaedia. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Skogvang, S. F. ((2017). Kven er eigentleg same? Morgenbladet, https://morgenbladet.no/aktuelt-portal/2017/12/kven-er-eigentleg-same

- Sokolovskiy, S. (2011). Russian legal concepts and the demography of Indigenous peoples. In P. Axelsson & P. Sköld (Eds.), Indigenous peoples and demography. The complex relation between identity and statistics (pp. 239–252). Berghahn.

- Stoor, J. P. A., Berntsen, G., Hjelmeland, H. M., & Silviken, A. (2019). If you do not birget [manage] then you don’t belong here: a qualitative focus group study on the cultural meanings of suicide among Indigenous Sámi in Arctic Norway. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78 (1), 1565861. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2019.1565861

- Svala, S. T. (2020). Bokmålsforbundet: Samer er ikke et urfolk. Ságat, https://www.sagat.no/nyheter/bokmalsforbundet-samer-er-ikke-urfolk/19.14964

- Tallbear, K. (2013). Native American DNA: Tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science. University of Minnesota Press.

- Túnon, H., Kvarnström, M., & Lerner, H. (2016). Ethical codes of conduct for research related to Indigenous peoples and local communities – core principles, challenges and opportunities. In A.-L. Drugge (Ed.), Ethics in Indigenous research: Past experiences – future challenges (pp. 57–81). Umeå.

- Ween, G. (2005). Sörsamiske sedvaner. Tilnärminger til rettighetsforståelser. Diedut, 5, 4–82.

- Zmyvalova, E. (2020). Human rights of indigenous small-numbered peoples in Russia: Recent developments. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 11, 334–359. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v11.2336