Abstract

William Zartman’s ‘ripeness’ theory says that parties to a violent conflict will not negotiate sincerely in the absence of a mutually hurting stalemate (MHS). In such circumstances, Zartman recommends a mediator employ coercion by escalating the conflict into a MHS, but the concept is not fully elaborated. Building on Zartman, this article specifies a new theory of ‘muscular mediation’, defined as a powerful mediator using coercion to achieve a mutual compromise that it formulates. The theory is evaluated in three cases from the 1990s: Bosnia, Rwanda, and Kosovo. The article finds that muscular mediation can work but also may backfire by magnifying violence against civilians, especially when all of three adverse conditions are present: (1) the coerced agreement threatens a vital interest of a party; (2) that party has the potential to escalate violence against the opposing side’s civilians; (3) the muscular mediator does not deploy sufficient military forces to deter or prevent such escalation. The article also explores why muscular mediation has been pursued under such adverse conditions. It concludes with advice for prospective muscular mediators.

‘Ripeness’ is not merely a prominent academic theory but also a concept used by diplomats to determine if and when to attempt to end violent conflict. The theory’s most frequently cited aspect, among both scholars and practitioners, is the ‘mutually hurting stalemate’ (MHS). According to Zartman, it is impossible to negotiate peace until the opposing sides are not only suffering but realize they have no hope of victory via military escalation. In the absence of a MHS, Zartman recommends that mediators engage in various forms of ‘manipulation’ to create a MHS to facilitate negotiations. His most controversial prescription is for mediators to employ coercion by escalating violence into a MHS, although the concept is not fully elaborated.

This article builds on Zartman by formulating a new theory of ‘muscular mediation’. In ideal form, muscular mediation is conducted by a state with sufficient coercive power not only to compel the two opposing sides but also to deter any obstructionist third parties, and comprises three successive steps: (1) drafting a peace agreement entailing mutual compromise; (2) coercing the stronger side by weakening it relatively until it accepts the deal; (3) coercing the other side by threatening to abandon it, so it accepts the deal in lieu of pursuing victory. This diplomatic strategy initially came to prominence after the Cold War, employed especially by the United States, which at the time was the sole remaining superpower, so the article evaluates it in three cases from the 1990s: Bosnia, Rwanda, and Kosovo.

The article finds that muscular mediation can work but also may backfire by magnifying violence against civilians, especially when all of three adverse conditions are present: (1) the coerced agreement threatens a vital interest of a party; (2) that party has the potential to escalate violence against the opposing side’s civilians; (3) the muscular mediator does not deploy sufficient military forces to deter or prevent such escalation. The article also explores why muscular mediation has been pursued under such adverse conditions. It concludes with advice for prospective muscular mediators.

Ripeness Theory

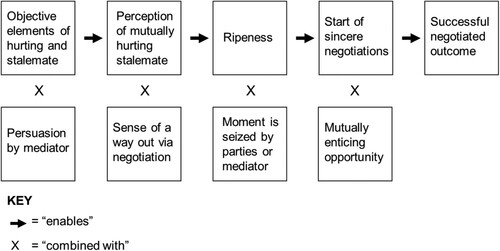

Zartman’s theory argues that, due to the emotions created by wartime sacrifices, ‘sincere’ peace negotiations will not begin before two conditions obtain (Zartman, Citation2000, p. 227). Until then, at least one party in any peace negotiations will be ‘insincere’—participating solely for instrumental reasons such as impressing international audiences or gaining time to mobilize resources for war (Goemans, Citation2000; Iklé, Citation1964, pp. 43–58, Citation2005, pp. 59–105; Mitchell, Citation2005). The first requirement for sincere negotiations is that the contending parties perceive they are in a MHS, ‘locked in a conflict from which they cannot escalate to victory, and this deadlock is painful to both of them’. Zartman (Citation2000, p. 228) says this perception stems partly from objective factors—such as repeated attempts to escalate that have failed to achieve decisive advantage, or a ‘recently avoided catastrophe’. Mediators may also try to persuade the parties that continued fighting is costly and fruitless. Only after the opposing parties perceive that escalation cannot succeed, while still suffering from the conflict, can they overcome the emotions that arise from war to rationally contemplate a mutually beneficial compromise (Pruitt, Citation2005). Wartime emotions thus add to the obstacles that even fully rational actors would face in negotiating peace, such as imperfect information and the difficulty of making commitments credible (Blainey, Citation1988; Fearon, Citation1995; Reiter, Citation2003; Walter, Citation1997).

Zartman’s second requirement for sincere negotiations is that the parties perceive a ‘sense of a way out’—an expectation that negotiations could yield an agreement to improve their situation. In Zartman’s words, ‘Parties do not have to be able to identify a specific solution, only a sense that a negotiated solution is possible for the searching and that the other party shares that sense and the willingness to search too’. If both of these conditions obtain, Zartman (Citation2000, pp. 228–229) defines the conflict as ‘ripe’, meaning sincere negotiations can begin if the parties themselves or a mediator seizes the moment. After sincere negotiations begin, Zartman says, they can reach fruition if there is a ‘mutually enticing opportunity’—a proposed deal that the parties perceive would leave them better off than fighting (). Finally, Zartman (Citation2000, p. 244) says a mediator can help create such an opportunity by offering a side-payment, which ‘increases the size of the stakes, attracting the parties to share in a pot that otherwise would have been too small’.

Zartman’s only explicit exception to the MHS requirement is if a mutually enticing opportunity is so attractive that it persuades the contending parties to negotiate sincerely prior to a MHS, but Zartman (Citation2000, p. 241) says that ‘few examples have been found in reality’. The logic of Zartman’s theory, however, suggests two other exceptions. First, a MHS may not be required to resolve mild conflicts, which lack the intense emotions that obstruct rational consideration of mutually beneficial compromise. Second, a MHS is not required to resolve a lop-sided war by negotiated surrender, when the weaker side offers significant concessions to end its losses and hurting, and the stronger side accepts to avoid the costs of achieving total victory (Kecskemeti, Citation1958; Rubin et al., Citation2004, p. 173; Pruitt, Citation2005, p. 11). Such conditional surrender occurs not when there is a MHS but rather, as noted by Schelling (Citation1966, p. 30), when only one side is hopeless and hurting: ‘On the losing side, prospective pain and damage were averted by concessions; on the winning side, the capacity for inflicting further harm was traded for concessions’.

Some critics complain that Zartman’s theory is underspecified and thus cannot predict when and how violence may be ended by negotiation (Coleman, Citation2000; Coleman et al., Citation2008; Forde, Citation2004; Greig, Citation2001; Hancock, Citation2001; Haass, Citation1990, pp. 9–14; Kleiboer, Citation1994, p. 109, 115; Mitchell, Citation2006, p. 95; O’Kane, Citation2006; Stedman, Citation1991, pp. 236–241). They question whether an MHS can be measured objectively, and hypothesize additional determinants of mediator success, including the internal politics of the contending sides, the roles of external patrons, and the specifics of negotiations. However, even such critiques acknowledge the importance of ripeness.

In unripe conflicts, Zartman’s advice is for a mediator to use its resources to ‘ripen’ the conflict, including potentially by escalating the violence. As Zartman (Citation2000, p. 241) explains, ‘To ripen a conflict one must raise the level of conflict until a stalemate is reached and then further until it begins to hurt—and even then work toward a perception of an impending catastrophe as well’. Although Zartman does not elaborate how mediators should do this, it may be inferred from excerpts of his 1985 article co-authored with Saadia Touval:

Mediators may have to … utiliz[e] … resources to move the parties … into a particular agreement that appears most stable or favorable. … The mediator must help … to produce the painful stalemate that leads them to see a mediated solution as the best way out … [T]his may mean temporarily reinforcing one side … to maintain the stalemate … [s]hifting weight … such as arms supplies. … [This] provides the mediator with bargaining power vis-á-vis the parties because of the constant possibility that it will join in a coalition with one against the other … if mediation fails. (Zartman & Touval, Citation1985, pp. 39–41)

Muscular Mediation Theory

To formalize this previously underspecified concept, I define ‘muscular mediation’ as the use of coercion by a mediator to achieve a mutual compromise that it formulates (Kuperman, Citation1999, Citation2010). The scope of the concept and theory are circumscribed because to succeed the mediator must be considerably more powerful than the contending sides and any potentially obstructive third party, and willing to deploy force if necessary. Muscular mediation typically is utilized in the absence of a MHS, when a weaker side is losing but insufficiently hurting and/or hopeless to surrender.

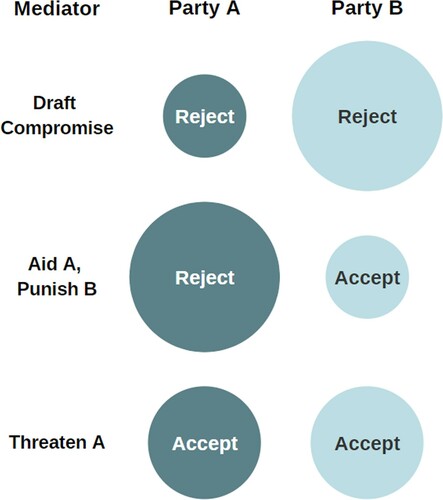

In ideal form, muscular mediation proceeds as follows. First, the mediator formulates a mutual compromise. Then it applies coercion (Schelling, Citation1966, p. 4, 172) against the stronger side—such as by imposing sanctions, providing (or permitting) military aid to the other side, and/or intervening militarily. The mediator’s aim is to reduce the relative strength and increase the suffering of the stronger side, so it accepts the mutual compromise formulated by the mediator. However, this coercion also increases the relative strength of the other side, thereby reducing its willingness to compromise. Accordingly, the mediator eventually may need to coerce that other side too, such as by threatening to halt the initial coercion of its opponent ().

Figure 2. Three steps of muscular mediation

Note: Circle areas represent the self-perceived strength of the opposing sides A and B, who either reject or accept the mediator’s proposed compromise.

If muscular mediation works, the opposing sides accept in principle the mutual compromise formulated by the mediator, negotiate the final details, and sign the deal. This can occur without literally creating a MHS, and in some cases, the mediator’s coercion against the stronger side may actually undo a battlefield stalemate and reduce the opposing side’s hurting. However, if the mediator eventually coerces both sides, then each party may come to believe that the mediator would use force to prevent its escalation to victory. Such a situation would have similar effects as a MHS without necessitating a battlefield stalemate or mutual hurting.

However, muscular mediation also raises risks, which scholars and practitioners have failed adequately to address. Most important, the mediator’s initial coercion against the stronger side, intended to incentivize compromise and thereby end violence, may backfire by provoking that side to escalate violence against its opponent’s civilians (Rudolf, Citation2016, p. 93; Wood et al., Citation2012). This is especially likely under three adverse conditions: the stronger side perceives that one of its vital interests (Salla, Citation1997, p. 459) is threatened by the mediator’s proposed deal; that side has the capacity to escalate violence against its opponent’s civilians; and the mediator does not deploy sufficient forces to deter or prevent such escalation.

Prior to the mediator’s coercion, the stronger side may hesitate to attack its opponent’s civilians due to fear of incurring international punishment. That deterrent wanes, however, when the mediator imposes such punishment anyway for the separate objective of coercing a peace deal. The stronger side may then attack opposing civilians for several reasons: to persuade the mediator to alleviate coercion; to weaken the opposing side by shrinking its demographic base; to compel migration to facilitate a more favourable territorial partition; or to inflict revenge prior to the war’s end (Kuperman, Citation2005, pp. 152–153). The likelihood of such backlash against civilians logically should increase as the mediator’s coercion escalates to threaten a party’s vital rather than subordinate interests. This is because such escalated coercion gives the party more to gain by compelling a relaxation of coercion or perpetrating a fait accompli that protects the threatened interest, and less to lose in that the mediator’s coercion against it already has escalated.

Muscular mediation ultimately is intended to reduce suffering, so if it exacerbates attacks against civilians, it has backfired. This dynamic may sometimes reflect the moral hazard of humanitarian intervention (Kuperman, Citation2008), if the weaker side is incentivized to fight by the prospect that endangering its own civilians would attract muscular mediation to help it win. In such cases, both the muscular mediator and the weaker side may bear some responsibility for the escalation of violence, which more typically is blamed on the stronger side. Muscular mediation also may have other downsides, such as creating a fragile peace that is dependent on continued international intervention (Zartman, Citation1997, pp. 16–17), or alienating countries whose cooperation is important for peacebuilding.

Lastly, muscular mediation has a third possible outcome, failure, if the coercion insufficiently alters the parties’ preferences, which can be due to other external intervention. Such failed coercion may cause at least one party to abandon the mediation and potentially seek an alternative mediator (Brooks, Citation2008; De Waal, Citation2007; Ker-Lindsay, Citation2009; Kuperman, Citation2009a; Nathan, Citation2007). The article’s next sections illustrate the above dynamics in the cases of Bosnia, Rwanda, and Kosovo.

Bosnia

Bosnia is the most revelatory case because it illustrates all three potential outcomes of muscular mediation: success, failure, and backfire. The country’s 1992–1995 civil war pitted three ethnic factions: Muslims, Serbs, and Croats. It ignited in April 1992, after the militarily weaker Muslims and Croats declared Bosnia’s independence from Yugoslavia without first agreeing to an ethnic territorial division that the militarily stronger Serbs and the European Community had demanded (Kuperman, Citation2008, Citation2016, pp. 379–386). Serb forces responded with a military offensive including ethnic cleansing that captured 70 percent of Bosnia within weeks. Aiming to carve out a contiguous Serb territory bordering Serbia, they still needed to capture several surrounded Muslim enclaves, which divided their territory and were vulnerable to attack, but threats of international intervention deterred them. Accordingly, the Serbs grudgingly accepted their divided territory for the time being, and by 1993 the main fighting was between the formerly allied Croats and Muslims.

During the war’s first three years, mediators proposed a series of peace plans, all of which failed because the Serbs insisted on contiguous territory and refused to retreat to only half of Bosnia. Coercion was initiated in 1992 by imposing economic sanctions on Yugoslavia to persuade it to halt military aid to the Bosnian Serbs so they would compromise. By early 1993, this succeeded in pressuring Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic to support the mediator’s proposal, but for domestic political reasons he could not entirely end military supplies to the Bosnian Serbs, so they rejected the plan that spring (Ingrao & Emmert, Citation2013, pp. 180–182). This first attempt at muscular mediation thus failed because indirect coercion via Yugoslavia was insufficient to alter Bosnian Serb preferences.

In 1994, muscular mediation escalated to coerce the Bosnian Serbs directly. The US-brokered Washington Agreement in March of that year enabled military aid and training for Bosnia’s Muslims and Croats (via Croatia) to reverse Serb gains on the battlefield (Beelman, Citation1997), and NATO gradually increased bombing of Bosnian Serb military targets (Kuperman, Citation2016, pp. 383–385). This backfired initially, however, because when the Bosnian Serbs discovered that coercion was tilting the military balance against them, they no longer were deterred from seizing the coveted Muslim enclaves, and indeed felt urgency to do so. Accordingly, they attacked in July 1995, and in the process murdered approximately 8000 Muslim men in Srebrenica, the largest crime of the entire war and the first large massacre by Serbs in the three years since the war’s opening phase. Peacekeepers had been deployed to Srebrenica, which was a UN-designated ‘safe area’, but their troop numbers and equipment were inadequate to deter or prevent the Serb attack. Thus, the flawed muscular mediation backfired during this period by incentivizing the Serbs to crush the Muslim enclaves.

In the wake of muscular mediation’s failure in spring 1993, and backfire in July 1995, it finally succeeded in autumn 1995. By September of that year, international military aid and bombing had enabled Bosnia’s Muslim and Croat forces to capture not just lost ground but also historically Serb territory, to control more than half the country (Burg & Shoup, Citation1999, pp. 355–367). This coercion persuaded the previously stronger Bosnian Serbs finally to negotiate sincerely, as evidenced by the fact that their leaders, who previously had opposed all mediator proposals since the outbreak of war, agreed on 29 August 1995, to be represented in negotiations by Milosevic, who had favoured all such proposals since 1993 because he sought to end sanctions on Yugoslavia (Ambrosio, Citation2001, pp. 89–90; Magas & Zanic, Citation2001, pp. 210–211; Chollet & Freeman, Citation1997, p. 108, 216; Doder & Branson, Citation1999, pp. 221–222). At the resulting Dayton peace talks, in November 1995, Milosevic quickly acquiesced to the US demands that Bosnia’s Serbs accept regional autonomy rather than independence, and within only 49 percent of Bosnia’s territory. Bosnia’s Serb leaders grudgingly accepted Milosevic’s concessions because the deal gave them more land than they now expected to retain if the war continued.

As the theory indicates, the mediator eventually also had to coerce the other side, which had been emboldened by the initial coercion against its opponent. The main sticking point at Dayton—according to the lead mediator, US Ambassador Richard Holbrooke—was the Muslims’ reluctance to accept less at the bargaining table than they now expected to win on the battlefield. Bosnia’s Muslims always had wanted a unitary rather than ethnically divided country, and finally they and the Croats enjoyed sufficient relative power to pursue that by force. A top Croatian official recalled, ‘We could have captured Banja Luka’, which was the effective Serb capital and biggest city in western Bosnia, because Serb ‘forces were panicking’ (LeBor, Citation2003, p. 242). The US State Department’s internal history similarly reports that Izetbegovic ‘believ[ed] that he was on the brink of another military success’ and that ‘the Serbs were on the run’ (Chollet & Freeman, Citation1997, p. 143, 146).

To compel the Muslims to accept compromise, American diplomats ultimately needed to threaten abandonment. Milder US attempts at persuasion, such as warning the Muslims that their military gains were insignificant or that the Serbs were poised to counterattack (Vuković, Citation2020, p. 437), had failed in light of the battlefield reality. Holbrooke therefore switched to pressuring Izetbegovic, warning him bluntly on October 4: ‘Washington does not want you to expect the United States to be your air force. If you continue the war, you will be shooting craps with your nation’s destiny’ (Holbrooke, Citation1999, p. 195). The next month, at the Dayton talks, US Secretary of State Warren Christopher still perceived Izetbegovic as the ‘most reluctant’ of the three Balkan leaders. Accordingly, during the final week of negotiation, Christopher threatened Izetbegovic even more explicitly that, ‘President Clinton … would not assist the Sarajevo leadership if they blocked a reasonable settlement’ (Chollet & Freeman, Citation1997, p. 226; Holbrooke, Citation1999, p. 305). Following this coercive threat, Izetbegovic reluctantly acquiesced to the Dayton accords that denied his goal of a unitary Bosnia. He did so even though the Muslim-Croat alliance, having benefited from mediator coercion against the Serbs, at the time enjoyed a military advantage and was neither stalemated nor hurting (Burg & Shoup, Citation1999, pp. 355–367).

Muscular mediation avoided further backfire in Bosnia, perhaps because all three adverse conditions had been mitigated: the Dayton agreement did not threaten the vital interest of any side; the preceding three years of ethnic cleansing and migration had reduced the number of minority enclaves vulnerable to attack; and 60,000 peacekeepers were deployed to avert violence. The peace deal’s mutual compromise was to establish a ‘Serb Republic’ confederated with a Muslim-Croat federation within a sovereign Bosnia. This meant that no side got its first choice: for Serbs, independence; for Muslims, a unitary Bosnia; for Croats, annexation by Croatia (Touval, Citation2001). However, each side secured its vital interest: for Serbs, a contiguous territory; for Muslims, avoiding formal partition; for Croats, cantons that might eventually be annexed by Croatia. Muscular mediation thus eventually succeeded in Bosnia when coercion was amplified and all three adverse conditions were alleviated.

Rwanda

Rwanda highlights three errors in the implementation of muscular mediation: imposing a deal that threatens the vital interest of a side capable of escalating violence against its opponent’s civilians; not deploying sufficient military forces to avert such escalation; and failing to coerce the other side to accept the deal rather than pursuing military victory. Historically, in Rwanda, minority Tutsi had comprised the ruling class until 1959, after which the Hutu majority gained control, but then Tutsi launched rebellions in the 1960s, which sparked retaliatory violence against Tutsi civilians that caused many of them to flee the country. Nearly three decades later, the country’s civil war started in October 1990, when longtime Uganda-based Rwandan Tutsi refugees invaded their home country under the banner of the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) to overthrow the Hutu regime (Kuperman, Citation2001, Citation2004). From 1990 to 1993, the Tutsi rebels grew in strength and territorial control, but intervening French troops repeatedly blocked their attempts to conquer the country. Hutu extremists reacted to the rebel incursions by perpetrating local massacres, halted each time by the Hutu president Juvénal Habyarimana, resulting in about 2000 deaths over three years.

No MHS existed because the rebels made gradual progress in their annual military offensives, yet the Hutu government continued to control the vast majority of the country with French support (Dallaire, Citation2003; Kuperman, Citation2004; Ruzibiza, Citation2005). Muscular mediation started in 1992, as western countries pressured the Rwandan government, which was perceived as the stronger side due to France’s support (Jones, Citation2001). Donor states conditioned their development aid on the regime’s agreeing to share power with both the invading Tutsi rebels and domestic Hutu opposition parties. France also announced a forthcoming total withdrawal of troops, to convince the Hutu government that it needed a peace deal (Kuperman, Citation1996).

Ultimately, the mediators coerced the Hutu regime to accede to the rebels’ key demands, in the Arusha peace accords of August 1993. Since the Tutsi comprised less than 10 percent of Rwanda’s population, and about 15 percent including refugees, the Hutu regime had proposed giving Tutsi rebels 10 percent of the slots in an integrated army. The RPF instead demanded 50 percent of officers and 40 percent of enlisted troops—which the mediators compelled the regime to accept. The mediators also coerced the regime to concede to a transitional government expected to be controlled by a coalition of the rebels and their domestic allies (Jones, Citation2001).

Many Hutu believed these concessions threatened their vital interests by enabling the Tutsi rebels to seize power at will, so such Hutu pursued two strategies to spoil the deal. First, they fractured the political alliance between the Tutsi rebels and the domestic Hutu opposition by fomenting fear of Tutsi hegemony. Tutsi forces inadvertently fed this fear by perpetrating two attacks in 1993: in February, a massive RPF offensive displaced one million Hutu civilians; and in October, in neighbouring Burundi, Tutsi soldiers killed the Hutu president and massacred thousands of Hutu civilians. As a result, by late 1993, Rwanda’s domestic Hutu opposition had split with the RPF and reunited with the regime in a ‘Hutu Power’ alliance, obstructing the Tutsi rebel plan to control the transitional government.

The Hutu regime also armed and trained irregular forces in anticipation that the RPF would attack after France withdrew in late 1993. The Tutsi rebels, realizing they had lost their peaceful path to power, and perceiving the regime would be vulnerable without French troops, did indeed plan a final attack to conquer the country (Kuperman, Citation2004, pp. 76–77). The mediators, however, mistakenly viewed the regime as the sole obstacle to peace, so they failed to coerce the rebels to abide by the peace deal. By early 1994, this flawed muscular mediation had incentivized both sides to prepare violent escalation.

On 6 April 1994, surface-to-air missiles shot down the plane carrying Rwanda’s Hutu president. Multiple Tutsi rebel officials (Mugabe, Citation2000; Rudasingwa, Citation2011; Ruyenzi, Citation2004; Ruzibiza, Citation2004) later admitted that their side did it. By the next day, the rebels launched their final invasion, and Hutu extremists started massacring Tutsi civilians and assassinating rebel-allied Hutu opposition politicians. Hutu extremists targeted Tutsi civilians for multiple reasons: to weaken the rebels by killing perceived collaborators; to deter the rebels from continuing their invasion; and to exact revenge for the president’s assassination (Kuperman, Citation2004). In three months, Hutu genocidaires killed an estimated half-million Tutsi—more than three-quarters of their total in Rwanda. Meanwhile, the Tutsi rebels killed tens of thousands of Hutu civilians, and many other Hutu also died in the conflict. About 2500 UN peacekeepers had been deployed, but they lacked adequate personnel, equipment, and mandate to avert the killing (Kuperman, Citation2001, pp. 20–21, 40, 89–91).

Muscular mediation thus backfired by siding with the Tutsi rebels rather than forging mutual compromise, thereby threatening the vital interests of the Hutu, who responded by escalating violence against Tutsi civilians, which the peacekeeping force was insufficient to prevent. A relatively low-intensity conflict that during the preceding three years had killed only 2000 civilians was transformed into a genocide and crimes against humanity that killed up to a million Rwandans in three months—magnifying the death toll approximately 500-fold. The average monthly killing rate spiked even more, some 6000-fold, from about 50 victims to 300,000. This underscores the potentially catastrophic consequences of poorly designed muscular mediation.

Kosovo

Although not as disastrous, Kosovo also illustrates how muscular mediation can backfire by imposing a deal that threatens the vital interest of one party without deploying sufficient forces to avert a violent backlash against the other side’s civilians. Kosovo’s conflict is rooted in 1989, when Serbia revoked the province’s autonomy, alleging that its ethnic Albanian majority was discriminating against the Serb minority. The Albanians’ initial response, from 1989 to 1997, was to declare nominal independence while resisting Serbian authority mainly through pacifist means, including establishing parallel tax, education, and health systems (Clark, Citation2000). This non-violent approach failed to achieve independence or even restore autonomy, so when weapons suddenly became available in 1997 from neighbouring Albania, the militant Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) launched a rebellion (Kuperman, Citation2008).

The KLA initially seized control of areas in central and western Kosovo. Serbian forces responded with a counter-insurgency in spring 1998, attacking and burning villages accused of harbouring the rebels. By late summer, Serbia appeared to have prevailed, as the rebels fled to neighbouring Albania (Judah, Citation2000, pp. 169–171).

As winter loomed, however, US officials expressed concern that ethnic Albanian civilians, who had been internally displaced by war and were afraid to return home due to the Serbian force presence, would die of exposure. The United States accordingly initiated coercion, but only against the stronger Serbian side to compel unilateral concessions, rather than forging a mutual agreement as envisioned by the theory. US Ambassador Holbrooke threatened Yugoslavia with NATO bombing, which successfully coerced Milosevic to commit in writing to halt fighting, withdraw some forces, and permit entry of 2000 unarmed international monitors, which he then did. By contrast, the KLA was not asked to sign and did not honour the cease-fire, so by winter it had reoccupied large swaths of Kosovo and resumed attacks against Serbian forces, reigniting the civil war (Crawford, Citation2001).

There was no MHS, because both sides still believed they could escalate to victory, and the hurting was bearable as only about 1500 civilians and combatants had died by September 1998 (Kosovo Memory Book, Citation2011). Serbia was confident that its superior forces armed with tanks and heavy weapons would again overwhelm the ragtag rebels armed only with light weapons. However, the Albanian rebels believed that if they continued to fight and provoke Serbian retaliation, the United States and NATO eventually would intervene decisively against the Serbs, as had occurred in Bosnia three years earlier (Kuperman, Citation2008, pp. 69–71).

The United States resorted to muscular mediation in February 1999, at a peace conference in Rambouillet, France, attempting to coerce concessions mainly from the Serbian side. US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright threatened to bomb Yugoslavia unless it agreed that Kosovo could hold an independence referendum after three years. Milosevic’s diplomats refused even to discuss this proposal, which many Serbians viewed as surrender of their historical heartland (Judah, Citation2000, p. 230; Mandelbaum, Citation1999, p. 4).

Instead, Yugoslavia prepared to escalate violence against its opponent’s civilians. When NATO implemented its coercive threat by commencing bombing in late March 1999, Yugoslav forces responded with attacks that within weeks killed about 10,000 ethnic Albanians and compelled the exodus from Kosovo of another 850,000, about half their total in the province (Ball et al., Citation2002). NATO intervention at the time was limited to aerial bombing and so could not prevent this civilian victimization. Yugoslavia’s aim in targeting the Albanian civilians may have been to compel NATO to halt the bombing, or to facilitate a north–south ethnic partition of Kosovo, or to exact revenge (Posen, Citation2000).

After 11 weeks of NATO bombing, in June 1999, Milosevic conceded to a modified peace deal that required his forces to withdraw from Kosovo but did not grant the Albanians an independence referendum. 50,000 peacekeepers deployed to Kosovo but were focused on the potential threat from Serbs, so they failed to stop the repatriating Albanian rebels and civilians from taking revenge by killing hundreds of Serb civilians and compelling the exodus from Kosovo of over 100,000 more, approximately half their total in the province (Abrahams, Citation2001; Matveeva & Paes, Citation2003, pp. 19–20).

Muscular mediation thus backfired twice. Initially it threatened Serbia’s vital interest of sovereignty over Kosovo, without deploying ground troops to avert violent backlash against Albanian civilians. Then it coerced the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces, without ensuring that the deployed peacekeepers would avert revenge attacks against Serb civilians. Prior to the start of mediator coercion in autumn 1998, the civil war had essentially ended in Yugoslav victory, after about 1500 fatalities. Poorly designed mediator coercion then reignited the civil war and incentivized both sides to commit massacres, which intervening forces failed to avert, magnifying the death toll nearly ten-fold to over 13,000 (Kosovo Memory Book, Citation2011).

Muscular Mistakes

Muscular mediation backfired to some extent in all three cases, so it is important to examine which mistakes were made and why. In Bosnia, the mediator’s coercion threatened the Serbs’ vital interest of a contiguous territory and eliminated their incentive for restraint against civilians, while gradually closing their window for escalation, so they crushed the Muslim enclaves while they could. All three adverse conditions should have been apparent: Serb leaders during the war consistently declared a vital interest in a contiguous territory; Serb forces had repeatedly shown their ability to attack the enclaves at will; and peacekeepers in the enclaves knew they could not fend off a concerted Serb attack. The mediator may have assumed optimistically that even though the Serbs could perpetrate mass killing, they would not, because they had not since UN peacekeepers deployed to Bosnia in summer 1992. If so, the mediator failed to understand how its coercion changed the incentives of the Serbs, by increasing their net benefit from crushing the enclaves quickly.

In Rwanda, too, all three adverse conditions were seemingly obvious: the peace proposal threatened the vital interest of the Hutu majority by enabling Tutsi rebel domination; the Hutu could escalate violence against Tutsi civilians, as illustrated by several wartime outbursts; and international political will was lacking for a military deployment sufficient to avert such violence. However, the mediator may not have comprehended the existential Hutu fear of the Tutsi rebels, or that the rebels were intent on military victory. The mediator also may have assumed that President Habyarimana would rein in Hutu extremists, as he had several times in preceding years but could not after being assassinated.

In Kosovo, the three adverse conditions again were clear: the peace proposal threatened Serbia’s vital interest in sovereignty over Kosovo; Serbia had demonstrated during the past year its ability to escalate violence against Albanian civilians; and international political will was lacking to deploy ground forces, prior to a peace agreement, to avert such violence (Judah, Citation2000, pp. 214–218, 269). Nevertheless, US diplomats convinced themselves that Yugoslav President Milosevic actually favoured the Rambouillet peace proposal and wanted NATO to bomb his country for a few days to persuade his domestic hardliners, which is why the Pentagon prepared only three days of bombing (Judah, Citation2000, p. 229). In the event, however, Milosevic retaliated by escalating violence against Albanian civilians, so the bombing continued for 11 weeks. The mediator’s benign view of the Albanians may explain why post-war peacekeepers were surprised by and therefore unprepared to prevent revenge attacks against Serb civilians.

Lessons in all three cases are that muscular mediators should try to avoid threatening the vital interests—or assuming the benign intent—of parties, and give greater attention to capacities for escalation and prevention of violence. The cases also highlight several persistent challenges that muscular mediators may need to overcome in the future. First is the difficulty of distinguishing each side’s truly ‘vital interests’ from its other demands in negotiations. One solution may be to pay more heed to subject matter experts, such as the American at the Rwanda peace talks who warned that giving the Tutsi rebels nearly half the slots in the armed forces, ‘would never be accepted by hard-line [Hutu] factions in the army’ (Jones, Citation1999, pp. 142–143).

A second challenge is reconciling the apparently incompatible interests of opposing parties. In some instances, this may be achieved through problem-solving, ambiguity, and lengthy time horizons. In Bosnia, for example, the Muslims initially demanded a unitary state, and the Serbs independence, which are incompatible. Through negotiations, however, it became clear that the Muslims would settle for a confederal state, and the Serbs for autonomy, if the agreement also provided for constitutional reform over time, which each side hoped would eventually enable its preferred outcome (Kuperman, Citation2006).

Third, it can be difficult to assess risks of violent escalation, which are based not just on the capabilities of regular and militia forces, and their recent patterns of engagement, but also potential changes of incentives, strategy, and tactics. Historically, however, some assessments have overcome this challenge, such as the CIA forecast for Rwanda three months prior to the genocide that warned of precisely such a worst-case scenario (Adelman et al., Citation1996, p. 66). Similarly, in Kosovo, warnings were published six months in advance that NATO bombing might provoke Serbian forces to ‘switch to genocidal tactics, killing many thousands of Kosovars before NATO stopped the violence’ (Kuperman, Citation1998). Muscular mediators should institutionalize roles for both governmental and independent experts to warn of such potential unintended consequences of coercion.

A fourth obstacle is deploying sufficient ground troops to deter or prevent escalation against civilians. Few countries have the logistics capabilities for such deployments (O’Hanlon, Citation2004), and those that do typically reserve these resources for self-interested rather than altruistic missions. Muscular mediators need to be realistic about whether they can muster adequate preventive forces before applying coercion.

Conclusion

Muscular mediation can forge peace even in the absence of a mutually hurting stalemate, as Bosnia eventually demonstrated. However, when facing all three adverse conditions, muscular mediation has high risk of backfiring and should be avoided. Even if facing only one or two of these conditions, muscular mediators should be cautious and adjust their strategies accordingly. For example, if a muscular mediator is unable or unwilling to deploy sufficient forces to avert violent escalation against civilians, it should try to ensure that its coercion does not incentivize such escalation (Kuperman, Citation2009b, p. 196), and so should avoid threatening the vital interests of any side with the capacity to attack civilians. When muscular mediation is too risky, there are non-coercive alternatives—such as track-two diplomacy or problem-solving workshops—that can try to foster the perception of a MHS without changing the balance of power. A consensual approach may require the mediator to be more patient, but under adverse conditions it poses less danger of backfiring.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of my late professor Saadia Touval. I am grateful for funding support from the Policy Research Institute of the LBJ School of Public Affairs, and for comments on preceding drafts from Fen Osler Hampson, anonymous reviewers including of this journal, and participants at the following events: 2014 Minefields of Mediation Workshop, Princeton University; 2011 Conference on Persistent Conflict in the twenty-first Century, London School of Economics; 2009 World Convention of the Association for the Study of Nationalities; 2008 American Political Science Association annual meeting; and 2008 International Studies Association annual meeting.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahams, F. (2001). Under orders: War crimes in Kosovo. Human Rights Watch.

- Adelman, H., Suhrke, A., & Jones, B. (1996). The international response to conflict and genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda experience: Early warning and conflict management. Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda.

- Ambrosio, T. (2001). Irredentism: Ethnic conflict and international politics. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Ball, P., Betts, W., Scheuren, F., Dudukovich, J., & Asher, J. (2002). Killings and refugee flow in Kosovo March-June 1999. Washington, DC: A Report to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

- Beelman, M. S. (1997). Dining with the Devil: America’s ‘Tacit Cooperation’ with Iran in Arming the Bosnians. The Alicia Patterson Foundation Reporter, 18(2). https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/dining-devil-americas-tacit-cooperation-iran-arming-bosnians

- Blainey, G. (1988). Causes of war. Simon and Schuster.

- Brooks, S. (2008). Enforcing a turning point and imposing a deal: An analysis of the Darfur Abuja negotiations of 2006. International Negotiation, 13(3), 413–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/157180608X365262

- Burg, S. L., & Shoup, P. S. (1999). The war in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic conflict and international intervention. ME Sharpe.

- Chollet, D., & Freeman, B. (1997). The road to Dayton: US diplomacy and the Bosnia peace process, May–December 1995. Washington, DC: Dayton History Project. US Department of State.

- Clark, H. (2000). Civil resistance in Kosovo. Pluto Press.

- Coleman, P. T. (2000). Fostering ripeness in seemingly intractable conflict: An experimental study. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11(4), 300–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022843

- Coleman, P. T., Fisher-Yoshida, B., Stover, M. A., Hacking, A. G., & Bartoli, A. (2008). Reconstructing ripeness II: Models and methods for fostering constructive stakeholder engagement across protracted divides. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 26(1), 43–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.223

- Crawford, T. W. (2001). Pivotal deterrence and the Kosovo war: Why the Holbrooke agreement failed. Political Science Quarterly, 116(4), 499–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/798219

- Dallaire, R. (2003). Shake hands with the devil. Random House Canada.

- De Waal, A. (2007). Darfur’s elusive peace. In A. De Waal (Ed.), War in Darfur and the search for peace (pp. 367–388). Harvard University Press.

- Doder, D., & Branson, L. (1999). Milosevic: Portrait of a tyrant. Simon and Schuster.

- Fearon, J. D. (1995). Rationalist explanations for war. International Organization, 49(3), 379–414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300033324

- Forde, S. (2004). Thucydides on ripeness and conflict resolution. International Studies Quarterly, 48(1), 177–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00296.x

- Goemans, H. E. (2000). War and punishment: The causes of war termination and the First World War. Princeton University Press.

- Greig, J. M. (2001). Moments of opportunity: Recognizing conditions of ripeness for international mediation between enduring rivals. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(6), 691–718. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002701045006001

- Haass, R. N. (1990). Conflicts unending: The United States and regional conflict. Yale University Press.

- Hancock, L. E. (2001). To act or wait: A two-stage view of ripeness. International Studies Perspectives, 2(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1528-3577.00049

- Holbrooke, R. (1999). To end a war. Knopf.

- Iklé, F. C. (1964). How nations negotiate. Harper and Row.

- Iklé, F. C. (2005). Every war must end. Columbia University Press.

- Ingrao, C. W., & Emmert, T. A. (2013). Confronting the Yugoslav controversies: A scholars’ initiative. Purdue University Press.

- Jones, B. D. (1999). The Arusha peace process. In H. Adelman & A. Suhrke (Eds.), The path of a genocide (pp. 131–156). Transaction.

- Jones, B. D. (2001). Peacemaking in Rwanda: The dynamics of failure. Lynne Rienner.

- Judah, T. (2000). Kosovo: War and revenge. Yale University Press.

- Kecskemeti, P. (1958). Strategic surrender: The politics of victory and defeat. Stanford University Press.

- Ker-Lindsay, J. (2009). The Emergence of ‘Meditration’ in International Peacemaking. Ethnopolitics, 8(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050902894995

- Kleiboer, M. (1994). Ripeness of conflict: A fruitful notion? Journal of Peace Research, 31(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343394031001009

- Kosovo Memory Book. (2011). Humanitarian law centre.

- Kuperman, A. J. (1996). The other lesson of Rwanda: Mediators sometimes do more damage than good. SAIS Review, 16(1), 221–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.1996.0013

- Kuperman, A. J. (1998, October 9–11). NATO move may widen war. USA Today.

- Kuperman, A. J. (1999, March 4). Rambouillet requiem: Why the talks failed. Wall Street Journal.

- Kuperman, A. J. (2001). The limits of humanitarian intervention: Genocide in Rwanda. Brookings Institution Press.

- Kuperman, A. J. (2004). Provoking genocide: A revised history of the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Journal of Genocide Research, 6(1), 61–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1462352042000194719

- Kuperman, A. J. (2005). Suicidal rebellions and the moral hazard of humanitarian intervention. Ethnopolitics, 4(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050500147267

- Kuperman, A. J. (2006). Power-sharing or partition? History’s lessons for keeping the peace in Bosnia. In M. Innes (Ed.), Bosnian security after Dayton (pp. 35–62). Routledge.

- Kuperman, A. J. (2008). The moral hazard of humanitarian intervention: Lessons from the Balkans. International Studies Quarterly, 52(1), 49–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00491.x

- Kuperman, A. J. (2009a). Darfur: Strategic victimhood strikes again? Genocide Studies and Prevention, 4(3), 281–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3138/gsp.4.3.281

- Kuperman, A. J. (2009b). Wishful thinking will not stop genocide: Suggestions for a more realistic strategy. Genocide Studies and Prevention, 4(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3138/gsp.4.2.191

- Kuperman, A. J. (2010). Ripeness revisited: The perils of muscular mediation. In T. Lyons & G. Khadiagala (Eds.), Conflict management and African politics (pp. 23–35). Routledge.

- Kuperman, A. J. (2016). Humanitarian intervention. In M. Goodhart (Ed.), Human rights: Politics and practice (3rd ed., pp. 370–388). Oxford University Press.

- LeBor, A. (2003). Milosevic: A biography. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Magas, B., & Zanic, I. (2001). The war in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1991–1995. Frank Cass.

- Mandelbaum, M. (1999). A perfect failure: NATO’s war against Yugoslavia. Foreign Affairs, 78(5), 2–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/20049444

- Matveeva, A., & Paes, W. C. (2003). The Kosovo Serbs: An ethnic minority between collaboration and defiance. Bonn International Center for Conversion.

- Mitchell, C. (2006). The right moment: Notes on four models of ‘ripeness’. In D. Druckman & P. F. Diehl (Eds.), Conflict Resolution (pp. 85–98). Sage.

- Mitchell, C. R. (2005). Conflict, social change, and conflict resolution: An enquiry.

- Mugabe, J.-P. (2000, April 21). Declaration on the shooting down of the aircraft. http://www.multimania.com/obsac/OBSV3N16-PlaneCrash94.html

- Nathan, L. (2007). The failure of the Darfur mediation. Ethnopolitics, 6(4), 495–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050701277863

- O’Hanlon, M. E. (2004). Expanding global military capacity for humanitarian intervention. Brookings Institution Press.

- O’Kane, E. (2006). When can conflicts be resolved? A critique of ripeness. Civil Wars, 8(3-4), 268–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240601060710

- Posen, B. R. (2000). The war for Kosovo: Serbia’s political-military strategy. International Security, 24(4), 39–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/016228800560309

- Pruitt, D. G. (2005). Whither ripeness theory?

- Reiter, D. (2003). Exploring the bargaining model of war. Perspectives on Politics, 1(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592703000033

- Rubin, J. Z., Pruitt, D. G., & Kim, S. H. (2004). Social conflict: Escalation, stalemate, and settlement. McGraw-Hill.

- Rudasingwa, T. (2011, October 1). I confirm it is Paul Kagame who sparked the Rwandan genocide. http://rwandinfo.com/eng/i-confirm-it-is-paul-kagame-who-sparked-the-rwandan-genocide-rudasingwa/

- Rudolf, P. (2016). Evidence-Informed Prevention of Civil Wars and Mass Atrocities. The International Spectator, 51(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2016.1152749

- Ruyenzi, A. J. (2004, July 5). Testimony. http://www.inshuti.org/ruyenzi.htm

- Ruzibiza, A. J. (2004, March 14). Statement. http://fdlr.r-online.info/Actualite/Abdul_Ruzibiza_testimony.htm

- Ruzibiza, A. J. (2005). Rwanda l’histoire secrète. Éditions du Panama.

- Salla, M. E. (1997). Creating the ‘Ripe Moment’ in the East Timor Conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 34(4), 449–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343397034004006

- Schelling, T. C. (1966). Arms and influence. Yale University Press.

- Stedman, S. J. (1991). Peacemaking in civil war: International mediation in Zimbabwe, 1974–1980. L. Rienner.

- Touval, S. (2001). Mediation in the Yugoslav wars: The critical years, 1990–1995. Palgrave.

- Vuković, S. (2020). Debunking the myths of international mediation: Conceptualizing bias, power and success. In M. O. Hosli & J. Selleslaghs (Eds.), The changing global order (pp. 429–451). Springer.

- Walter, B. F. (1997). The critical barrier to civil war settlement. International Organization, 51(3), 335–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/002081897550384

- Wood, R. M., Kathman, J. D., & Gent, S. E. (2012). Armed intervention and civilian victimization in intrastate conflicts. Journal of Peace Research, 49(5), 647–660. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343312449032

- Zartman, I. W. (1997). Introduction: Toward the resolution of international conflicts. In I. W. Zartman & J. L. Rasmussen (Eds.), Peacemaking in international conflict (pp. 3–22). USIP Press.

- Zartman, I. W. (2000). Ripeness: The hurting stalemate and beyond. In P. C. Stern & D. Druckman (Eds.), International conflict resolution after the Cold War (pp. 225–250). National Academies Press.

- Zartman, I. W., & Touval, S. (1985). International mediation: Conflict resolution and power politics. Journal of Social Issues, 41(2), 27–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb00853.x