Abstract

Twenty-six years after the Dayton Peace Agreement, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s constitution has remained largely intact, despite a well-established consensus on the necessity of reforming the post-Dayton system. This article looks at the Prud and Butmir Processes, two of the last unsuccessful attempts at comprehensive constitutional reform, with a focus on the political elite from the Republika Srpska. We use securitization theory, combining content and discourse analyses, to understand how the Prud and Butmir Processes, and by extension the overall constitutional reform, were successfully framed as existential threats to the Republika Srpska by the ethnopolitical elite, justifying the continuation of conflict-perpetuating routines.

Introduction

In 1995, the Dayton Peace Agreement (DPA) put a lid on a bloody war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) that had raged for three years prior. Its Annex IV forged a constitution for a country that had freshly emerged from a conflict fought largely along ethnic lines. As a result, the most distinctive features of BiH’s constitution hinge on the categorization of the three main ethnic groups—the Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats—as ‘constituent peoples’, consigning everyone else to the ‘Others’ category, and the striking division of the country into two almost identical in size, coequal ‘entities’—the majority-Serb Republika Srpska (RS) and the mostly Bosniak–Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH). The two entities wield significant powers and sovereignty, and have their own parliaments, governments, and veto rights over all national policies (Kapidžić, Citation2020, p. 85). This and other involved institutional divisions, such as the tripartite state Presidency consisting of representatives of each constituent peoples, were fashioned according to the consociational model of power-sharing among the ethnopolitical elites, with ‘proportionality in government and guaranteeing mutual veto rights and communal autonomy’ (Belloni, Citation2009, p. 359), which has been described as ‘one of the most complex political systems that exist’ (Kapidžić, Citation2020, p. 81).

Consequently, over the years, a consensus in academic and policy-making circles has formed for the need of moving past a constitutional arrangement whose immediate goal was to prevent further violence to one that would build a lasting peace. The arguments commonly made in support of constitutional reform, or at least contra the current system, mostly draw on the 2005 Opinion of the Venice Commission and the subsequent rulings of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) (Richter, Citation2018, p. 262; Tolksdorf, Citation2015, pp. 406–407), but many scholars also criticize the discriminatory ethnic logic embedded in the constitution (Cooley, Citation2013; Pinkerton, Citation2016), the inherent dysfunctionality of the system due to many veto opportunities (Kartsonaki, Citation2016, p. 499; Zenelaj et al., Citation2015, p. 422), and note the failure of the constitution to decisively resolve the underlying conflict (Sebastián, Citation2012, p. 597).

Nonetheless, BiH’s constitution has remained largely intact, though not for a complete lack of trying. Two last attempts at comprehensive constitutional reform are the Prud and the Butmir Processes initiated in 2008 and 2009, respectively, that saw the leaders of the largest parties engage in protracted negotiations, first under support—and later direct mediation—of the EU and the US. At the time, the International Crisis Group ([ICG], Citation2009a) wrote of the Prud agreement as ‘by far the most serious and hopeful attempt to break out of the country’s paralysis’ (p. 4), and described the Butmir package as a ‘good and fair proposal, whose adoption would significantly improve both Bosnia’s political climate and its functionality’ (ICG, Citation2009b, p. 7). Though this was not how the political leaders presented the proposals to their domestic audiences. It is generally believed that the ethnopolitical elites benefit immensely from the current convoluted institutional setup, which enables extensive and lucrative clientelist networks to flourish (Kartsonaki, Citation2016, p. 508; Richter, Citation2018, p. 263). However, as Belloni (Citation2009, p. 367) and Tolksdorf (Citation2015, p. 404) note, the RS elite is the most ardent supporter of the status quo, being loath to transfer any prerogatives from the entity to the state level.Footnote1 Indeed, the supposedly ‘good and fair’ Butmir proposal was instead framed by the elite as ‘very dangerous and absolutely unacceptable to the RS’ (‘Ozbiljna tendencija’, Citation2009), while the RS was purportedly ‘put in potential danger’ by the Prud Process (Morača, Citation2009).

There exists a significant corpus of research on the Prud and Butmir Processes. Though the latter has received much more scholarly attention, almost all studies—with the exception of Zdeb (Citation2017)—exclusively focus on external actors. At the risk of oversimplifying, what most of these studies seem to suggest is that, if only the EU and the US had chosen a different mediation strategy (Richter, Citation2018; Zenelaj et al., Citation2015), an approach based on conflict resolution rather than conflict management (Cooley, Citation2013), applied conditionality more consistently (Džihić & Wieser, Citation2011; Tolksdorf, Citation2015), or acted more cohesively (Sebastián, Citation2012), the outcome would have been different. This, however, while having significant policy implications, fails to explain why the Butmir and the preceding Prud Processes were the last of their kind—negotiations between the largest political parties at the highest level on comprehensive constitutional reform—but also the enduring failure of both the domestic ethnopolitical elites and the international mediators to introduce constitutional changes.

One way of explaining this was presented by Basta (Citation2016) who—though not focusing on the Prud and Butmir Processes—argues that the resistance of BiH’s institutions to reform is attributable to their symbolic power. For example, Bosnian Serbs see the ethnic and institutional fragmentation of the state as necessary components of what demarcates them as a distinct ethnically-defined community within BiH, which should explain their overall reluctance to engage in reforms (Basta, Citation2016, p. 945). What is implied but not further explored is that the stability of this distinct identity is predicated not only on the presence of an antagonistic Other who is often framed as a threat (Basta, Citation2016, p. 965), but also on the preservation of this underlying situation through a routinization of that conflictual Self-Other relationship. In contrast, constitutional reform processes disrupt this conflict-perpetuating routine and dominant Self-Other understandings, and therefore implicate identity constructions (Rumelili, Citation2015a, p. 63). Basta’s (Citation2016)—by his own admission—‘static’ sociological institutionalist approach is unable to account for these processes of threat-framing, and how this conflictual Self-Other relationship is sustained in the face of constitutional reform’s potential to transcend it. This article, therefore, builds upon his findings by highlighting these processes on the cases of the Prud and Butmir talks.

We do this by drawing on securitization theory, which highlights the discursive process of constructing something as an existential threat to a particular object. Although securitization is a frequent occurrence in BiH, we argue that its use during constitutional reform processes performs the function of a conflict-perpetuating mechanism that limits the prospect of constitutional reform unmaking the relations of enmity that are foundational to the current political structure. With an empirical focus on the case of the RS, this paper therefore attempts to understand how the RS ethnopolitical elite framed the supposedly advantageous Prud and Butmir Processes—and by extension comprehensive constitutional reform—as an existential threat to the entity, justifying the resumption of conflict-producing routines.

The article proceeds in four sections. The first provides some background information on the Prud and Butmir Processes. The second section outlines the theoretical framework, with a focus on securitization processes in protracted conflict environments, followed by a discussion of the methodology used. The fourth section presents the results of the analysis, while the conclusion discusses our contribution to the debate on constitutional reform in BiH.

The Prud and Butmir Processes

The Prud Process began in November 2008 with a meeting in the eponymous village in northern BiH, after which the leaders of the three largest ethnopolitical parties—Milorad Dodik of the Serb Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) and then the Prime Minister of the RS, the Bosniak Party of Democratic Action’s (SDA) Sulejman Tihić, and Dragan Čović from the Croat Democratic Union (HDZ)—announced they had come to an agreement regarding issues of constitutional change, ownership of state property, population census, the state budget, and the constitutionalization of the semi-autonomous Brčko District region. Aside from the constitutional reform, all other issues were conditions for the closure of the Office of the High Representative—BiH’s international administrator (ICG, Citation2009a, p. 4). The provisions of the Prud agreement regarding constitutional reform included the territorial reorganization of the country into four units—with diverging interpretations of what those units encompass—ensuring compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights, and improving the state’s functionality (ICG, Citation2009a, p. 5). The agreement was extolled by both the EU and the US, evidenced not least by then US Vice President Joe Biden’s visit to Sarajevo in May 2009 inter alia to express support to the talks on constitutional reform (‘Uređenje BiH’, Citation2009). Between January and June, subsequent meetings of the ‘Prud troika’ to hash out the details of the Prud agreement were held in the cities of Sarajevo, Banja Luka, and Mostar, though usually lacked either Dodik or Tihić, while Čović was a more eager participant. For example, Dodik walked out from the meeting in Mostar in February 2009 after demanding that a self-determination clause be included in the constitution (Gudelj, Citation2009), while Tihić was unwilling to negotiate with Dodik after the RS National Assembly passed a declaration in May 2009 vowing to return all state competencies to the RS entity (‘Nastavak prudskog procesa’, Citation2009). The talks finally broke down in July 2009 when Tihić proclaimed that ‘the Prud troika no longer exists’ (‘Tihić: “Prudska trojka”’, Citation2009). The Prud agreement, however, did birth the first and only, if largely symbolic, amendment to BiH’s constitution, which just constitutionalized the de facto status of the Brčko District (ICG, Citation2009a, pp. 4–5).

In October 2009, attempting to revive the momentum and touting accelerated EU and NATO membership procedures as an incentive, the US and the EU organized talks on constitutional reform in a NATO military base in the town of Butmir on the outskirts of Sarajevo. Two rounds of talks—on 8–9 and 20–21 October—were mediated by Deputy Secretary of the US State Department James Steinberg, and Swedish Foreign Minister and former High Representative in BiH Carl Bildt, representing the Swedish EU Presidency (ICG, Citation2009b, p. 4). Apart from the Prud troika, the Butmir Process included leaders of the Party of Democratic Progress (PDP), the Croat Democratic Union 1990 (HDZ 1990), the Party for BiH (SBiH), and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) (‘Butmir: Predstavljanje prijedloga’, Citation2009). The ‘Butmir package’ attempted to tackle the same constitutional reform issues as the Prud agreement, such as removing discriminatory provisions and improving the state’s efficiency, but, unlike the Prud Process, centred almost exclusively on constitutional change (Zdeb, Citation2017, p. 377). The main points of the initial Butmir package aimed at creating a parliamentary system by empowering the BiH Council of Ministers and creating the post of prime minister—at the same time relegating the authority of the tripartite presidency—establishing a single countrywide electoral district, reserving seats in an expanded House of Representatives for ‘Others’, and included a so-called ‘EU clause’ that would ensure that the state speak with one voice in its membership negotiation with the EU (ICG, Citation2009b; ‘Prijedlog Butmirskog sporazuma’, Citation2009). All parties except the SDA rejected this reform package. Despite that, the talks continued throughout November and December 2009 with individual party leaders and experts (‘Kreće nova runda’, Citation2009). Nonetheless, the mediators were not successful in reconciling the views of the party leaders, while a proclaimed intention of the Spanish EU Presidency in March and April 2010 to breathe new life into the Butmir Process with the so-called ‘Madrid Declaration’ was stillborn (‘Radmanović: Madridska deklaracija’, Citation2010).

Just as the negotiations crumbled, the ECtHR issued its seminal ruling in December 2009 in the case of Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina, which once again underscored the urgent necessity to bring BiH’s constitution in line with fundamental human rights (Cooley & Mujanović, Citation2015, p. 49). Following the collapse of the Prud and Butmir Processes, and despite numerous rulings of the ECtHR that followed the Sejdić and Finci case confirming the discriminatory nature of BiH’s constitution, no similarly ambitious attempt at comprehensive constitutional reform has occurred to date (Cooley, Citation2013, p. 184; Richter, Citation2018, p. 260).

Theoretical Framework

Securitizing Desecuritization and the Normalcy of the Exceptional in Post-war BiH

Beginning with the end of the Cold War, Ole Wæver (Citation1989) set out on a daunting task ‘to rethink the concept of security’ (p. 1). Over the following decade, he did so primarily through his collaborative work with Barry Buzan. The joint endeavour came to be known as the Copenhagen School of Security Studies, and their theory as securitization theory. Securitization, they argued, is the ‘discursive process through which an intersubjective understanding is constructed within a political community to treat something as an existential threat to a valued referent object, and to enable a call for … exceptional measures to deal with the threat’ (Buzan & Wæver, Citation2003, p. 491). With this ‘broad conceptual move’ (Guzzini, Citation2011, p. 330), the Copenhagen School sees security not as an objective condition that is out there, waiting to be described, but through the lens of a performative speech act. This means that the act of uttering security is the primary reality (Wæver, Citation1995, p. 55); the speech act’s power lies in its performativity—it does not describe reality, but rather shapes the way issues are perceived. This initial conceptualization of security as speech act was later reworked by scholars of the so-called Paris School, who emphasize the broader social and discursive context in which the security claims are made, replacing the universal power of the speech act to shape the context in which it is uttered with a model of securitization whose success is highly context-dependent (Balzacq, Citation2005, Citation2010, Citation2012; Stritzel, Citation2007).

To avoid a potentially infinite expansion of the research agenda by treating security as discursively constructed, one of the key points of the above definition is the existential quality of the perceived threat, which is what distinguishes a security issue from a simple inconvenience (Wæver, Citation2009, p. 22). Security is about the survival of the referent object, and the threat has to be framed by the securitizing actor as incompatible with the continued existence of the unit (Wæver, Citation1989, p. 26). It is within this logic of existential threat to a valued referent object that extraordinary measures are justified and used, thereby moving the issue from the realm of ‘normal politics’ to the realm of security (Buzan & Wæver, Citation2003, p. 71). Conversely, the act of desecuritization brings a securitized issue back into the domain of ‘the normal bargaining process of the political sphere’ (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 4).

Despite their normative commitment to ‘normal politics’ in the form of ‘less security, more politics’ (Wæver, Citation1989, p. 52), the Copenhagen School initially left the concept largely underexplored. However, the exceptionalism of security can only be defined if we have a clear picture of what normal politics entails. As pointed out by Roe (Citation2012): ‘Extraordinary politics is, in this sense, what normal politics is not’ (p. 251). Some scholars have argued that ‘extraordinary measures’—in the sense of breaking free of rules and norms of everyday politics—could have only been conceived in the context of the ‘procedural normalcy’ of Western liberal democracies (Aradau, Citation2004; Roe, Citation2012). Others have argued that the concept is altogether irredeemable due to the perceived civilizationist imaginary embedded in the distinction between the normal politics of reasoned, liberal, civilized dialogue, and the barbarous and racialized ‘primal anarchy’ of securitization (Howell & Richter-Montpetit, Citation2020). For their part, Wæver and Buzan (Citation2020) have recently clarified that they see normal politics as nothing more than an empty background, that is, ‘whatever passed as normal until an exception was installed through securitization’ (p. 391). No (liberal democratic) essence is attached to normal politics, only that it is ‘non-securitized’ (Wæver & Buzan, Citation2020, p. 391). Nonetheless, as the following paragraphs will argue, this simple distinction between the realms of normal, non-securitized politics, and the politics of securitized exception that underpins classical securitization theory cannot satisfactorily capture the logic and effects of securitization processes in BiH, nor in other cases of protracted conflicts, which also has implications for the concepts of ‘extraordinary measures’, ‘desecuritization’, and ‘referent objects’.

Informed primarily by the Paris School’s emphasis on the social context of the security utterance, there has been a surge of interest in securitization processes in post-conflict and protracted conflict environments in recent years (Abulof, Citation2014; Adamides, Citation2020; Antoniou, Citation2020; Oskanian, Citation2021; Rosoux, Citation2020; Rumelili, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Sjöstedt et al., Citation2019; Vuković, Citation2020). The common theme among these studies is the pervasiveness, normalization, and deep internalization of securitization processes within such societies that are facilitated by—and, in turn, influence—an environment marked by ‘recurring violence, psychological manifestations of animosity, intense mutual feelings of fear and distrust, amplified stereotypes, and reservations over each other’s intentions’ (Vuković, Citation2020, p. 145). Abulof (Citation2014), for example, calls this ‘deep securitization’—a situation in which discourses of existential threats permeate a society—while Adamides (Citation2020) refers to cases in which ‘the same or very similar threat discourses are frequently repeated by mainstream securitizing actors’ as ‘routinized securitization’ (p. 59). This dynamic is most visible in cases of protracted conflicts in which routinized or deep securitization becomes a conflict-perpetuating mechanism (Rumelili, Citation2015a), and a tool that ‘consolidates and furthers the status quo for those who are profiting from a protracted conflict’ (Vuković, Citation2020, p. 146). The very protraction of protracted conflicts is therefore the outcome of normalized securitization processes and threat-perpetuating routines of elites (Adamides, Citation2020, p. 64).

There is a strong case to be made that BiH finds itself in a similar position. If, indeed, BiH’s contemporary politics is marked by, what Belloni (Citation2009) calls in a reversal of Clausewitz, a ‘continuation of [the] war by other means’ (p. 360), then there seems to be no point in distinguishing normal politics from securitized politics, as securitization is part—indeed, the very essence—of the normal everyday political process. This is not to say that securitization theory loses its analytical purchase in BiH, since this is a significant revision, but it does tell us a different story. Securitization in BiH perpetuates the comfortably routinized conflictual ethnic relationships, or ‘routines of enmity’ (Mitzen, Citation2006, p. 362), which have created a stable system of meaning through antagonistic Self-Other understandings. A phenomenon of ‘conflict attachment’ emerges, as the distinct identity of the Self is dependent on the presence of an antagonistic and diametrically-opposed Other, and a preference for conflict-producing routines—and therefore ideational stability or ‘ontological security’—is established through the reproduction of existing securitized practices and narratives (Mitzen, Citation2006; Rumelili, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). The mobilization of these existing securitized and ‘difference-producing discourses’ (Rumelili, Citation2015a, p. 53) are, in a sense, Copenhagen School’s ‘extraordinary measures’ reapplied in the context of intractable conflicts. When normal means securitized, extraordinary measures no longer seem extraordinary. As Adamides (Citation2020) notes: ‘Reminding an audience of an existential threat is not necessarily to seek access to extraordinary measures, but only to safeguard the approval for the perpetuation of the existing political routine actions’ (p. 68).

Desecuritization in BiH’s context, on the other hand, is then not merely about the ‘unmaking of securitization’ in the sense of moving of individual issues from the securitized to the normal realm, as envisaged by classical securitization theory and often repeated by studies of securitization processes in protracted conflict environments, but about the ‘unmaking of a particular conceptualization of the political’ (Huysmans, Citation1998, p. 574), one that is based on an ethnicized Schmittian friend-enemy dichotomy and reinforced through perpetual securitization. On this point, it is worth quoting Huysmans (Citation1998) in full:

Unmaking representations of an existential threat can also imply dissolving relations of enmity as the foundation of the political community. In other words, in this modality desecuritization unmakes politics which identify the community on the basis of expectations of hostility. Instead of simply removing policy questions from the security sector and plugging them into another sector, desecuritization turns into a political strategy which challenges the fundaments of the political realist constitution of the political community head on. (p. 576)

Finally, a related issue is Wilkinson’s (Citation2007) call to put greater emphasis on the constitutive processes involved in securitization in order to shake off the Copenhagen School’s perceived ‘Westphalian straitjacket’. This primarily means spotlighting how a referent object and its particular identity are (re-)constructed through securitization. The traditional referent object in classical securitization theory has unsurprisingly been the state (Wilkinson, Citation2007, p. 9), reinforced by Wæver’s (Citation2009) explanation that ‘the referent object is that which you can point to and say, “it has to survive, therefore it is necessary to … ”’ (p. 22). But just as a threat cannot be pointed to outside of its discursive construction, the same is true of a referent object. The specific form and substance of the referent object is unknowable outside of its use in securitized discourse; its meaning and identity are constructed and reproduced through the very act of securitization (Hansen, Citation2000, p. 288). This is all the more relevant in view of constitutional reform’s desecuritizing potential of reconfiguring the constitutive Self-Other relations and thus redefining identities. Therefore, in our analysis, we pay attention to the representation of the Other(s), but also to the particular imagining of the Self and the production of narratives of self-identity.

Facilitating Conditions and Operationalization

Before moving on to the analysis, it is important to discuss the operationalization of securitization. There has been some debate as to how to ‘measure’ the success of a securitizing move. On a general level, the Copenhagen School distinguishes between three ‘facilitating conditions’, later reworked by Stritzel (Citation2007) as three ‘layers of securitization’: 1) the speech act must follow the internal ‘grammar’ of security, meaning construct a plot leading from the existential threat to a possible way out; 2) the securitizing actor must possess the capacity to construct collective meaning; 3) the securitizing move must be embedded in the historically evolved discursive practices out of which it emerged. Following this, we can distinguish between several indicators of securitization’s success that have been identified by numerous authors.

The first indicator identified is polarization, as it should uncover the ‘embedded self–other understandings that predispose’ audiences to certain securitizing moves (Guzzini, Citation2011, p. 335). The second indicator is emotions, particularly fear, humiliation, and anger, which can facilitate (or constrain) securitization to the extent that ‘emotionalization of discourse [becomes] the goal that any securitizing actor pursues’ (Amin, Citation2020, p. 239). The third indicator is ‘references to the past’. Rosoux (Citation2020) shows how the success of securitization ‘cannot be understood without paying attention to a particular memory’, and, specifically, how an emphasis on diverging interpretations of the past, or the most painful historical episodes, reveals the ‘fundamental incompatibilities that sustain conflictual relationships’ (p. 196). The fourth indicator is media bias, which should be a good measure of uneven positional power of securitizing actors to influence and define collective meaning, with high levels of bias stifling alternative voices and thereby increasing the securitizing move’s chances of success (Dolinec, Citation2010, pp. 18–19). The fifth and final indicator is the treatment option, with a ‘possible way out’, as mentioned earlier, being the sine qua non of the grammar of security, and therefore of a successful securitizing move.

It should be noted that neither a single indicator nor all of them taken together can determine the success of a securitizing move, but can only act as facilitators. This has been strongly argued by the Copenhagen School in order to preserve the theory’s non-deterministic character, and emphasise the ethico-political choice of initiating and accepting a securitizing move as such (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 29; Wæver, Citation2011, p. 476). We can only ever know that a securitizing move succeeded after the fact (Buzan et al., Citation1998, pp. 46–47); that is, after it was accepted by the audience and/or after the proposed measures were used. As securitization is a performative act, its success can ‘never [be] exhaustively explained by its conditions’ (Buzan & Wæver, Citation2003, p. 72). Therefore, these indicators mostly have a heuristic purpose in disentangling the complex process of securitization, and can never be used to predict or fully capture why a particular securitizing move was successful.

Methodology

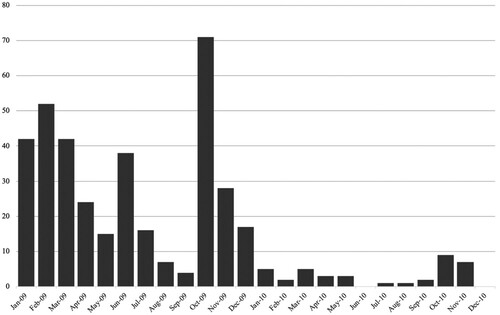

The analysis borrows the methodology and operationalization of the above-sketched indicators from Ejdus and Božović (Citation2017), combining content and discourse analyses of news articles from the period. The result we aim to achieve with this is to produce a richer description of the securitization process. In principle, discourse analysis maps ‘the emergence and evolution of patterns of representations which are constitutive of a threat image’ (Balzacq, Citation2010, p. 39), while content analysis seeks ‘to capture the kind of cues to which audience is likely to be responsive’ (Balzacq, Citation2010, p. 50). Here, we have to acknowledge the limitations of the methodology, as content and discourse analyses of news articles cannot shed light on how the audience receives the securitizing move (i.e. whether or not the securitizing actors are merely preaching to the choir), nor can the securitizing move of political actors be fully extricated from the particular framing of the issue by the media (Vultee, Citation2010). Nonetheless, with these limitations in mind, we proceed with content and discourse analyses of archives of two print and two broadcast media outlets from the RS. These are the Radio Television of Republika Srpska (RTRS), Radio Television of Bijeljina (RTV BN), Nezavisne Novine, and Glas Srpske, which have been chosen for their high circulation in the RS. Specifically, 22.2% of the RS’s population reads Glas Srpske, 17.5% reads the online version of the RTRS, 10% reads Nezavisne Novine, and 6.7% the online edition of the RTV BN (Vukojević, Citation2015). The analysis covers 1267 articles containing key words such as ‘Prud’, ‘Butmir’, and ‘constitutional reform’ (ustavna reforma), published between January 2009 and December 2010.

The first variable that has been hand-coded for content analysis is polarization, which had four possible values: no polarizing language, moderate speech/language based on facts, partially polarizing language/moderate criticism, strongly polarizing language/unbridgeable differences. The second variable is emotionality where articles were assigned either no emotionality, moderate emotionality, or extreme emotionality of discourse. The third variable, references to the past, was coded according to certain seminal points in BiH’s history, with either no reference to the past, a reference to the Second World War, to former Yugoslavia, to the disintegration of Yugoslavia, to NATO intervention in BiH, to the war in BiH and signing of the DPA, to Kosovo’s status, or to other historical events. Media bias as the fourth variable had four values: neutral, balanced, moderately biased, and biased. The extent of bias was assessed mainly on the basis of whether those at the receiving end of polarization were given space to respond, and how that space compared to that of the securitizing actor: no space given to opposing views indicated bias, less space compared to the ‘main voice’ indicated moderate bias, equal space pointed to a balanced article, while factual reporting indicated a neutral article. The fifth variable was much more detailed, as it attempted to categorize all the treatment options that were proposed into: no possibility of solution, evolution/gradual change, revolution/radical change, compromise/negotiation/cooperation with the other side, without compromise/negotiation/cooperation with the other side, peaceful settlement of the issue, violent settlement of the issue, institutional solution, and cultural solution.

Analysis of the Securitization of the Prud and Butmir Processes

Polarization and Emotionality

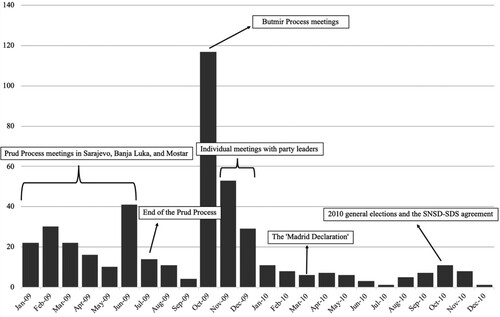

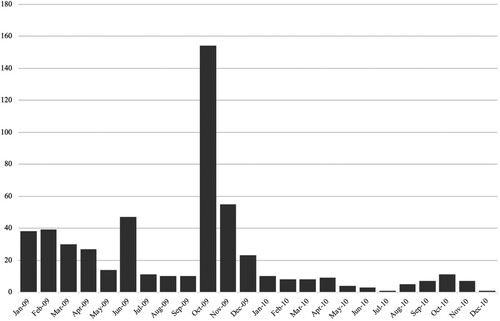

The content analysis of 1267 articles from the period revealed that partially and highly polarizing language was used in 35% of cases (see ). Comparably, moderate and high emotionality of discourse was identified in just under 42% of cases (see ). For a temporal distribution of polarization and emotionality, as well as other variables, which should provide a sense of the temporal dimension of securitization and the most active securitizing periods, see Appendix A. Polarization and its concomitant emotional undertone occurred on three levels: first, within the RS; second, outside the RS and against the FBiH and the state-level Bosniak political elite as representatives of the ‘internal Other’; and third, outside the RS and against international actors, i.e. the ‘external Other’.

Table 1. Polarization

Table 2. Emotionality of discursive acts

Polarization within the RS was mainly carried out by the opposition and against the governing SNSD and its president Milorad Dodik. The aim of internal polarization was twofold: to securitize the Prud Process, which the opposition was excluded from, and to deny the governing coalition the political legitimacy needed for constitutional reform. The Serb Democratic Party (SDS)—the largest opposition party in the RS—and its president Mladen Bosić used Dodik’s attendance at the talks to frame it as a betrayal of the RS’s interests and as a direct threat to the DPA (‘O Prudu’, Citation2009), demanding guarantees from Dodik that the RS would ‘remain within current borders and with intact sovereignty’ or else drop out of the talks (‘Inicijativa za referendum’, Citation2009). Bosić later challenged Dodik’s political authority in deciding upon these matters altogether, because the alteration of the DPA meant that ‘the RS is put in potential danger’, and is thus not a ‘matter for the RS government, nor the majority in the [RS] Assembly, nor the governing party, and definitely not for the leader of the governing party’, concluding that it is ‘a question for all citizens of RS’ (Morača, Citation2009). Because of Dodik’s involvement in the Prud talks, the PDP, another opposition party, maintained that every vote for SNSD is therefore ‘a direct vote to abolish the RS’ (‘PDP: SNSD prodao RS’, Citation2010). The leader of the Serb Radical Party, Milanko Mihajlica, even labelled Dodik as the ‘gravedigger of the DPA’, arguing that he should abandon the costly Prud talks for the sake ‘of those who gave their lives for the RS’ (Šajinović, Citation2009a).

Unlike the first level of polarization, which began very early on, polarization against the Bosniak political elite manifested itself fully, albeit more intensely, only after the Prud Process and during the Butmir Process, from the second half of 2009 to the general election in October 2010. While the opposition attempted to securitize the Butmir Process as well, the role of the main securitizing actor shifted to the governing coalition. Two complementary securitizing moves arising from this level of polarization have been identified. First is framing the Butmir Process as a Bosniak-orchestrated crisis. Already in June 2009, Dodik claimed that there is a ‘permanent effort of Bosniak politicians to create an unstable political situation’ (Gajević, Citation2009). Nebojša Radmanović (SNSD) was even blunter, insisting that Bosniaks ‘are creating a political crisis and in that situation they want to change the Constitution of BiH’ (‘Radmanović: Problem je neostvarivanje’, Citation2009). That the Butmir Process was orchestrated by the Bosniaks was made clear by the SDS as well, contending that the Butmir Process was the result of ‘three-year-long lobbying activities of Sarajevo in Washington, during which Bosniak politicians secured various resolutions of the US Congress for the negotiations, which are harmful to the RS and will now be used as instruments against the RS’ (‘SDS: Poziv predsjedniku’, Citation2009).

The second securitizing move was claiming that the true motive behind the Butmir Process and the constitutional reform was the subjugation of the RS by the Bosniak ethnopolitical elite. A day before attending the Butmir meeting, Dodik said that the constitutional reform process ‘clearly shows how [Bosniaks] want to dominate BiH’ (Bašić, Citation2009b, p. 2), warning that, if the RS were to accept the Butmir proposal, the Serbs would ‘greatly endanger their survival in this region for the next twenty years’ (Maunaga, Citation2009). With this particular, yet often made, rhetorical move, the RS elite are imagining the Republika Srpska as, quite literally, a Serb republic (srpska republika). Neither the RS as such, simply as one administrative-territorial unit within BiH (i.e. devoid of any meaning), nor Bosnian Serbs as such are made into the referent object. Instead, the future existence of Bosnian Serbs is tied to the future existence of the RS as an object that supposedly guarantees their collective security, which is not self-evidently so. That the security of the Bosnian Serbs means the security of the RS, and vice versa, consequently becomes ingrained in the social imaginary. Abulof (Citation2014) described a similar securitization dynamic on the case of Israel in which ‘the state must exist to preserve the people, and the people must persist (often with an assured majority) to sustain the state’ (p. 402). This is not a particularly new insight in BiH since the ‘ethnicization of space’ is a strategy often employed by the ethnopolitical elite, exemplified by the RS’s name itself (Björkdahl, Citation2018), but it is one worth highlighting as this particular self-narrative goes directly against the objectives of constitutional reform in BiH, insofar as it aims to create a more inclusive political system and at least partially transcend dominant Self-Other understandings.

Not surprisingly, Dodik’s narrative of an ulterior motive to the Butmir Process was given credence to by his acolytes. Nebojša Radmanović maintained that the ‘political corps’ from Sarajevo ‘wants to rule over the whole country and does not want to negotiate with representatives of other peoples’ (Filipović, Citation2009b). Not to be outdone, the Glas Srpske columnist Miroslav Filipović (Citation2010) followed the same line when he claimed that leaders from Sarajevo have ‘unitarist goals, at the core of which is the desire for Bosniak predominance and cruel rule over other peoples in the country’ (p. 4). Petar Kunić (Democratic People’s Alliance – DNS) said that the Butmir Process is ‘very dangerous and absolutely unacceptable to the RS’ (‘Ozbiljna tendencija’, Citation2009), while the columnist of the Nezavisne Novine, Dragan Jerinić (Citation2009), even insinuated that, if the Butmir talks were to fail, Sulejman Tihić and the ‘radical wing of the SDA [have] a plan B, according to which the constitutional reform, which should ultimately define a unitary state, would be carried out with violent, that is war methods’.

The analysis of the third level has identified a polarization against the external Other, chiefly the US and the EU. The securitizing moves from the second level continued, and, here as well, we can identify the narrative that the Butmir Process was a crisis orchestrated from the outside, whose ultimate goal was to violently impose constitutional reform onto the RS. For example, Dodik warned that ‘legal violence of the international community is behind the imposition of constitutional reform’ proposals at Butmir (‘Zvaničnici RS’, Citation2009), which were rigged to ‘favour one people at the expense of the other two’ (Bašić, Citation2009c). SDS similarly claimed that the ‘arranged [Butmir] talks which are dangerous for the future of the RS [are] organized exclusively under the auspices of states that openly advocate the centralization of BiH’ (‘SDS pozvao SNSD’, Citation2009), and that accepting the Butmir package would cause ‘great damage to the position of Serbs in the future’ (‘Kuzmanović započeo konsultacije’, Citation2009), thus echoing the ethnicization of the RS as a referent object that was identified before. Dodik again claimed in March 2010, that ‘for years, there has been legal violence of the international community present here, which is trying to devastate the political, institutional and every other capacity of the RS with various decisions’, one of which is ‘the case of “Finci and Sejdić v BiH” that is trying to be framed as a verdict to be used for extensive constitutional changes’ (‘Dodik: Sarajevo traži’, Citation2010). Securitization in the context of polarization against the external Other reached its apex when Slavko Mitrović (SNSD) promoted an abstruse idea of an international conspiracy taking place ahead of the Butmir talks. He contended that the ‘persistent attacks’ on the RS, whose goal is ‘weakening of its negotiating position’, are part of ‘a scenario of provocations and incidents which would generate unforeseen events, so that NATO would close the BiH borders [leading to] a blitzkrieg against the RS’ (Mitrović, Citation2009).

References to the Past

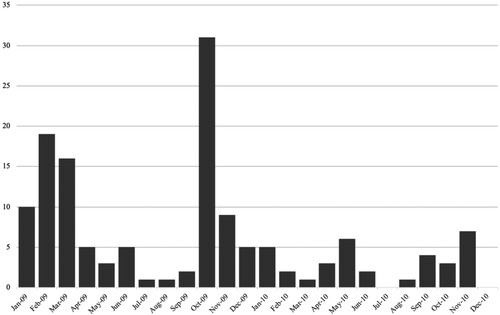

The content analysis also identified sporadic references to the past (see ). The most frequently mentioned historical event was the war in Bosnia, identified in 7.81% of articles. Of the more pertinent narratives in relation to that event, we can single out a relatively frequent revival of the negotiations on the DPA, with a particular emphasis on framing the Butmir Process as ‘the second Dayton’. SDS was vociferous in this respect, arguing that ‘talks on the most important question for the future of the RS should not be held in a NATO base that is not under BiH sovereignty’, adding that ‘because of the subject and the location, we are obviously dealing with an attempt of organizing a kind of Dayton 2’ (‘SDS pozvao SNSD’, Citation2009). One of the negotiators for the RS at Dayton 14 years earlier, Vladimir Lukić, lent credence to this assertion, maintaining that ‘Bosniak politicians persistently want to realize what they failed to do in the war and in Dayton’, which is ‘why they are calling for Dayton 2’ (Filipović, Citation2009a), while Slavko Mitrović (Citation2009) insisted that ‘hastily-organized’ Butmir’s ‘scenery is supposed to be reminiscent of Dayton in 1995 in order to extort a Dayton 2’.

Table 3. References to the past

Bias

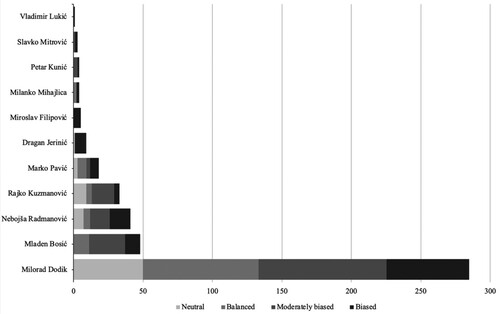

While the most prominent securitizing actors have already been identified by the preceding analysis, we have not yet considered the presence of bias. The content analysis shows that all of the identified securitizing actors enjoyed a high degree of bias, which occurred in no less than half of all the articles in which they were the main voice (see ). There are, however, very significant differences between them as regards the frequency of their appearances in articles. Thus, the list ranges from Dodik, who was the main securitizing actor in 285 articles (22.5% of all examples), which is more than all of the other 10 securitizing actors combined, to Vladimir Lukić, who was the main voice in only 1 example. Moreover, in absolute terms, Dodik had the largest number of biased articles (60), which is more than all of the articles which the second most frequent securitizing actor, Mladen Bosić, appeared in.

Treatment Options

Finally, having identified an existential security threat—buttressed by polarization, emotional undertone, underlying bias, and references to the past—the securitizing actors from the RS proposed numerous treatment options, that is solutions to the identified security problem (see ). It should be noted, however, that some treatment options, such as the institutional solution, could be framed either as constructive or destructive, depending on the context. That is why, for the purposes of this analysis, we will delve deeper and focus on two specific measures within the two most frequent treatment options: political unity within the RS (cooperation with the other side – 15.8%), and a referendum on independence (institutional solution – 15.3%).

Table 4. Treatment options

We first turn to the calls for unity among political parties in the RS. All securitizing actors equally demanded a unified defence of the RS against the perceived threat of constitutional reform. Thus, a month before the talks at Butmir, Dodik and Bosić held a meeting in order to reach a consensus on the issue of constitutional reform. On that occasion, Bosić declared that the SDS is ‘ready to help in the defence against pressures concerning the RS [because] the SDS cannot be in the opposition when it comes to the RS’ (Bašić, Citation2009a, p. 3). Marko Pavić, then President of the DNS (a member of the governing coalition), echoed these sentiments while commenting on the meeting, saying that ‘no one can have the right to be in the opposition when the interests of the RS and its citizens are at stake’, which is why ‘there is no government or opposition on this issue, the priority is the protection of the vital interests of the RS and the people of the RS’ (Tasić, Citation2009). Indeed, another meeting of representatives from the governing coalition and opposition was organized by Rajko Kuzmanović (SNSD), the President of the RS, two days ahead of the Butmir talks. After the meeting, Kuzmanović ‘emphasized the need for unity of all relevant political factors in the RS with regard to the key issues concerning the preservation of the constitutional and legal position of Srpska’ (‘Konsultacije kod Kuzmanovića’, Citation2009). The impetus for a unified stance on the Butmir Process also came from (nominally) non-governmental organizations in the RS, with one—the Serb Movement of Non-governmental Associations—demanding ‘from the representatives of the Serb people to be united in the defence of Srpska at today’s negotiations in Butmir’ (‘Jedinstveno u odbrani Srpske’, Citation2009).

A referendum on the independence of the RS was either advocated indirectly, by supporting the inclusion of a provision in the constitutional reform package that would allow for such a possibility, or directly. Thus, we identify a gradual move from the former strategy to the latter. The provision for the right of self-determination was first broached already in February 2009 during the Prud Process, when Dodik conditioned the continuation of the talks with an ultimatum ‘that the new constitution includes a provision that the entities have the right to self-determination and secession, and that this must be determined by a referendum three years after the adoption of the new constitution’ (Gudelj, Citation2009). While this idea was again floated by Dodik in October 2009 (Šajinović, Citation2009b), the Butmir Process elicited a more direct strategy. A day before the Butmir talks, Dodik announced that ‘he will not allow changes to the DPA that would be to the detriment of RS’, and that ‘should they be imposed, he will organize a referendum’ (‘Dodik: U Butmir ne’, Citation2009). Later that month, Dodik again warned that any ‘imposed solutions would lead to the destabilization of the situation in BiH’, concluding that ‘in response to such a situation, a referendum of the RS citizens will follow’ (Šikanjić, Citation2009). Even though calls for a referendum, regardless of its nature, are understood as illusions to secession (ICG, Citation2009b, p. 3), Dodik finally crossed the Rubicon in November, when he made known that ‘the RS is preparing for the option of BiH remaining and surviving, but also for the option that it cannot survive’ in which ‘everything must draw to a close, however, with a referendum in the end’ (‘Dodik: OHR smeta’, Citation2009). An independence referendum did not, in the end, take place, and part of the reason why is to be found in the lack of consensus on this measure even among the governing SNSD. Nikola Špirić (SNSD), who presided over the BiH Council of Ministers, came out against an independence referendum, arguing that ‘it is necessary to deal with EU [accession] issues, and not topics such as the referendum’ (‘Ključ za BiH’, Citation2010), and even Dodik vacillated on the issue, at one point saying that they are ‘not, of course, advocates of transforming the RS’s borders into state borders’ (Čubro, Citation2009).

Unlike the independence referendum, the proposed measure of establishing political unity in defence of the RS against constitutional reform, in fact, came to fruition after the October 2010 general elections and one year after the talks were initiated at Butmir, when an agreement was signed between two supposedly fierce political competitors. ‘The Platform on the Coordinated Action of the SNSD and the SDS’, as described by Bosić, was supposed to ‘allay the constant fear that some of the politicians from the RS would accept a constitutional solution to its detriment’, and established that ‘they accept neither the Prud nor the Butmir Process … in future talks on BiH’s constitution’ (‘Bosić: Platforma SDS’, Citation2010). At its signing on 22 November 2010, Dodik declared ‘that the RS is indivisible, that that is the basis of all talks, and any intrusion into its political and territorial competences preclude the possibility of any dialogue on the subject’ (Tadić, Citation2010).

That there was no comparable constitutional reform process since then—certainly not any remotely as ambitious—may be indicative of this particular measure’s success and of the lasting impact of the securitization of the Prud and Butmir Processes. Adamides (Citation2020, p. 90), for example, notes that the ‘unchallenged period’ following a successful securitization is longer in cases where there are no internal divisions over what constitutes a threat, as the framing of a threat becomes undisputed by the oppositional political elite and the audience. Certainly, all future attempts at reform will have to confront this securitized narrative of constitutional reform. Thus, a high degree of polarization, excessive emotionality, discursive linkages to divisive historical events, entrenched positional power of securitizing actors through media bias, and the foregrounding of possible measures, all facilitated the success of the RS ethnopolitical elite in securitizing constitutional reform in Prud and Butmir, thus justifying the resumption of the normal routines of enmity that they tried so adamantly to safeguard.

Conclusion

For years, the enduring failure to reform BiH’s post-conflict system has stumped the academic community. The particular research puzzle comes, on the one hand, from the necessity to ensure fundamental human rights through constitutional change, the evident advantages of making the state more functional, and the obstinate efforts on the part of the international community to provide worthwhile incentives; while despite all of this, the elites have consistently resorted to intransigence and belligerence. In this paper, we attempted to contribute to this debate by using securitization theory. On the cases of the Prud and Butmir Processes of constitutional reform, and with a focus on the RS, we tried to show how constitutional reform was successfully framed as an existential threat to the entity by the RS ethnopolitical elite, justifying the continuation of conflict-perpetuating routines. Combining content and discourse analyses, we attempted to chart the success of securitizing moves during the talks on constitutional reform by paying attention to five facilitating conditions, namely polarization, emotionality of discourse, references to the past, media bias, and treatment options.

The Prud Process was marked by internal polarization, in which the opposition figures assumed the role of the main securitizing actors with the aim of framing the agreement on constitutional reform and Dodik’s involvement in it as a threat to the RS. The Butmir Process, on the other hand, was marked by an antagonization—underpinned by a high degree of emotionality—of the Bosniaks and the international community by both the ruling as well as opposition parties in the RS. References to the past, in particular to the war in BiH and the negotiation of the DPA, were discursively linked to the context of the constitutional reform. Thus, the Butmir Process was framed as a revision of the DPA, a do-over with which the Bosniak ethnopolitical elite, aided by the international actors, wanted to achieve their war goals by means of constitutional reform. All securitizing moves were strongly bolstered by an extraordinarily high degree of bias which stifled alternative voices and contributed to a successful securitization of constitutional reform. The measure of rallying the RS political elite—almost equally advocated by all securitizing actors—around the proposal that the Prud and Butmir Processes never again be negotiated was put in writing with an agreement between the SNSD and the SDS, marking a securitized turning point after which attempts at reform were abandoned in favour of the status quo.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the journal’s editors, and the three anonymous referees for their invaluable suggestions and comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although certain progress since 1995 has been made regarding the transfer of competences to the state, such as unifying the armed forces, integrating the taxation system, and creating a state-level intelligence agency, most of these reforms were done under strong external influence, and did not particularly reflect the willingness of local actors, especially from the RS, to engage in meaningful reform (Sebastián, Citation2012, p. 598).

References

- Abulof, U. (2014). Deep securitization and Israel's ‘demographic demon’. International Political Sociology, 8(4), 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12070

- Adamides, C. (2020). Securitization and desecuritization processes in protracted conflicts: The case of Cyprus. Palgrave Pivot.

- Amin, F. (2020). An ‘existential threat’ or a ‘past pariah’: Securitisation of Iran and disagreements among American press. Discourse & Communication, 14(3), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481319893756

- Antoniou, K. (2020). Beyond the speech act: Contact, desecuritization, and peacebuilding in Cyprus. In M. J. Butler (Ed.), Securitization revisited: Contemporary applications and insights (pp. 168–193). Routledge.

- Aradau, C. (2004). Security and the democratic scene: Desecuritization and emancipation. Journal of International Relations and Development, 7(4), 388–413. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800030

- Balzacq, T. (2005). The three faces of securitization: Political agency, audience and context. European Journal of International Relations, 11(2), 171–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105052960

- Balzacq, T. (2010). Securitization theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve. Routledge.

- Balzacq, T. (2012). Constructivism and securitization studies. In V. Mauer, & M. D. Cavelty (Eds.), Handbook of security studies (pp. 56–72). Routledge.

- Basta, K. (2016). Imagined institutions: The symbolic power of formal rules in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Slavic Review, 75(4), 944–969. https://doi.org/10.5612/slavicreview.75.4.0944

- Bašić, Ž. (2009a, September 10). Ukidanje entitetskog glasanja ne dolazi u obzir. Glas Srpske, 3.

- Bašić, Ž. (2009b, October 8). Ustavne promjene za RS nisu interesantne. Glas Srpske, 2.

- Bašić, Ž. (2009c, October 19). Prijedlozi montirani u korist samo jednog naroda. Glas Srpske, 3.

- Belloni, R. (2009). Bosnia: Dayton is dead! Long live Dayton!. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 15(3-4), 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537110903372367

- Björkdahl, A. (2018). Republika Srpska: Imaginary, performance and spatialization. Political Geography, 66, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.07.005

- Bosić: Platforma SDS i SNSD postavlja nove odnose u BiH. (2010, November 12). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=31124.

- Butmir: Predstavljanje prijedloga SAD i EU. (2009, October 9). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10179.

- Buzan, B., & Wæver, O. (2003). Regions and powers: The structure of international security. Cambridge University Press.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Cooley, L. (2013). The European Union’s approach to conflict resolution: Insights from the constitutional reform process in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Comparative European Politics, 11(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.21

- Cooley, L., & Mujanović, J. (2015). Changing the rules of the game: Comparing FIFA/UEFA and EU attempts to promote reform of power-sharing institutions in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Global Society, 29(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2014.974512

- Čubro, M. (2009, February 17). Kuper podržao dogovor iz Pruda. Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- Dodik: OHR smeta dejtonskom putu BiH. (2009, November 20). Nezavisne Novine, 2.

- Dodik: Sarajevo traži ustavne promjene radi centralizacije BiH. (2010, March 27). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=18582.

- Dodik: U Butmir ne na dogovor, nego na pregovor. (2009, October 7). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10070.

- Dolinec, V. (2010). The role of mass media in the securitization process of international terrorism. Politické Vedy, 13(2), 8–32.

- Džihić, V., & Wieser, A. (2011). Incentives for democratisation? Effects of EU conditionality on democracy in Bosnia & Hercegovina. Europe-Asia Studies, 63(10), 1803–1825. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2011.618681

- Ejdus, F., & Božović, M. (2017). Grammar, context and power: Securitization of the 2010 Belgrade Pride Parade. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 17(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1225370

- Filipović, M. (2009a, November 20–22). BiH jedino može da opstane na dejtonskoj osnovi. Glas Srpske: Plus, 4.

- Filipović, M. (2009b, December 5–6). Sarajevski politički krug hoće da vlada cijelom zemljom. Glas Srpske: Plus, 4–5.

- Filipović, M. (2010, April 6). U Sarajevu ništa novo. Glas Srpske, 4.

- Gajević, B. (2009, June 17). Zalaganje za dejton nije antidejtonsko. Glas Srpske, 2.

- Gudelj, J. (2009, February 22). Dodik: Teritorija RS ne smije biti upitna. Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- Guzzini, S. (2011). Securitization as a causal mechanism. Security Dialogue, 42(4-5), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010611419000

- Hansen, L. (2000). The Little Mermaid silent security dilemma and the absence of gender in the Copenhagen School. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 29(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298000290020501

- Holbraad, M., & Pedersen, M. A. (2012). Revolutionary securitization: An anthropological extension of securitization theory. International Theory, 4(2), 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971912000061

- Howell, A., & Richter-Montpetit, M. (2020). Is securitization theory racist? Civilizationism, methodological whiteness, and antiblack thought in the Copenhagen School. Security Dialogue, 51(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010619862921

- Huysmans, J. (1998). The question of the limit: Desecuritisation and the aesthetics of horror in political realism. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 27(3), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298980270031301

- Huysmans, J. (2008). The jargon of exception—On Schmitt, Agamben and the absence of political society. International Political Sociology, 2(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2008.00042.x

- Inicijativa za referendum. (2009, January 31). Nezavisne Novine, 3.

- International Crisis Group. (2009a). Bosnia’s incomplete transition: Between Dayton and Europe (Europe Report No. 198).

- International Crisis Group. (2009b). Bosnia’s dual crisis (Europe Briefing No. 57).

- Jedinstveno u odbrani Srpske. (2009, October 20). Glas Srpske, 2.

- Jerinić, D. (2009, October 21). Sjeti se Hayoza. Nezavisne Novine, 15.

- Kapidžić, D. (2020). Subnational competitive authoritarianism and power-sharing in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 20(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2020.1700880

- Kartsonaki, A. (2016). Twenty years after Dayton: Bosnia-Herzegovina (still) stable and explosive. Civil Wars, 18(4), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2017.1297052

- Ključ za BiH odgovornost Bošnjaka. (2010, January 21). Glas Srpske, 4.

- Konsultacije kod Kuzmanovića. (2009, October 7). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10085.

- Kreće nova runda pregovora. (2009, November 14). Nezavisne Novine, 3.

- Kuzmanović započeo konsultacije uoči sastanka na Butmiru. (2009, October 6). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10046.

- Maunaga, G. (2009, November 28–29). Redukcija ustava BiH ugrozila bi opstanak Srba. Glas Srpske, 7.

- Mitrović, S. (2009, October 20). Tuđe dobre namjere. Nezavisne Novine, 14.

- Mitzen, J. (2006). Ontological security in world politics: State identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of International Relations, 12(3), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066106067346

- Morača, N. (2009, February 2). Bosić: RS je u opasnosti. Nezavisne Novine, 3.

- Nastavak prudskog procesa neizvjestan. (2009, June 14). Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- O Prudu u Skupštini RS. (2009, January 29). Nezavisne Novine, 5.

- Oskanian, K. (2021). Securitisation gaps: Towards ideational understandings of state weakness. European Journal of International Security, 6(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.13

- Ozbiljna tendencija ka regionalizaciji države. (2009, October 24). Nezavisne Novine, 3.

- PDP: SNSD prodao RS. (2010, August 21). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=26603.

- Pinkerton, P. (2016). Deconstructing Dayton: Ethnic politics and the legacy of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 10(4), 548–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1208992

- Prijedlog Butmirskog sporazuma. (2009, October 19). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10692.

- Radmanović: Madridska deklaracija neprihvatljiva za RS. (2010, April 1). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=18861.

- Radmanović: Problem je neostvarivanje Ustava. (2009, October 9). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10171.

- Richter, S. (2018). Missing the muscles? Mediation by conditionality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Negotiation, 23(2), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718069-23021155

- Roe, P. (2012). Is securitization a ‘negative’ concept? Revisiting the normative debate over normal versus extraordinary politics. Security Dialogue, 43(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010612443723

- Rosoux, V. (2020). The role of memory in the desecuritization of inter-societal conflicts. In M. J. Butler (Ed.), Securitization revisited: Contemporary applications and insights (pp. 194–216). Routledge.

- Rumelili, B. (2015a). Identity and desecuritisation: The pitfalls of conflating ontological and physical security. Journal of International Relations and Development, 18(1), 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2013.22

- Rumelili, B. (2015b). Ontological (in)security and peace anxieties. In B. Rumelili (Ed.), Conflict resolution and ontological security: Peace anxieties (pp. 10–29). Routledge.

- SDS pozvao SNSD i PDP da ne učestvuju na sastanku na Butmiru. (2009, October 4). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=9958.

- SDS: Poziv predsjedniku RS da zakaže sjednicu Parlamenta. (2009, October 11). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10284.

- Sebastián, S. (2012). Constitutional engineering in post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Peacekeeping, 19(5), 597–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2012.721998

- Sjöstedt, R., Södeberg Kovacs, M., & Themnér, A. (2019). Demagogues of hate or shepherds of peace? Examining the threat construction processes of warlord democrats in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Journal of International Relations and Development, 22(2), 560–583. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-017-0111-3

- Stritzel, H. (2007). Towards a theory of securitization: Copenhagen and beyond. European Journal of International Relations, 13(3), 357–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066107080128

- Šajinović, D. (2009a, April 15). Prudski sporazum krupan promašaj. Nezavisne Novine, 14.

- Šajinović, D. (2009b, October 14). Entitetsko glasanje nije dovedeno u pitanje. Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- Šikanjić, T. (2009, October 18). Ne očekujemo nametanja rješenja. Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- Tadić, S. (2010, November 23). Pozicija RS u Sarajevu biće nesumnjivo jaka i jedinstvena. Glas Srpske, 3.

- Tasić, S. (2009, September 12–13). Entitetsko glasanje nesporno i o tome nema rasprave. Glas Srpske: Plus, 4.

- Tihić: “Prudska trojka” više ne postoji. (2009, July 10). Glas Srpske, 3.

- Tolksdorf, D. (2015). The European Union as a mediator in constitutional reform negotiations in Bosnia and Herzegovina: The failure of conditionality in the context of intransigent local politics. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 21(4), 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2015.1095045

- Uređenje BiH na domaćim vlastima. (2009, May 20). Nezavisne Novine, 2–3.

- Vukojević, B. (2015). Mediji u Republici Srpskoj: Publike i sadržaji u kontekstu teorije koristi i zadovoljstva. CM: Communication and Media, 10(34), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.5937/comman10-9184

- Vuković, S. (2020). Conflict management redux: Desecuritizing intractable conflicts. In M. J. Butler (Ed.), Securitization revisited: Contemporary applications and insights (pp. 145–167). Routledge.

- Vultee, F. (2010). Securitization as a media frame: What happens when the media ‘speak security’. In T. Balzacq (Ed.), Securitization theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve (pp. 77–93). Routledge.

- Wæver, O. (1989). Security, the speech act: Analysing the politics of a word (Working Paper No. 19). Centre for Peace and Conflict Research.

- Wæver, O. (1995). Securitization and desecuritization. In R. D. Lipschutz (Ed.), On security (pp. 46–86). Columbia University Press.

- Wæver, O. (2011). Politics, security, theory. Security Dialogue, 42(4-5), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010611418718

- Wæver, O. (2009). What exactly makes a continuous existential threat existential – and how is it discontinued? In O. Barak & G. Sheffer (Eds.), Existential threats and civil-security relations (pp. 19–35). Lexington Books.

- Wæver, O., & Buzan, B. (2020). Racism and responsibility – The critical limits of deepfake methodology in security studies: A reply to Howell and Richter-Montpetit. Security Dialogue, 51(4), 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620916153

- Wilkinson, C. (2007). The Copenhagen School on tour in Kyrgyzstan: Is securitization theory useable outside Europe? Security Dialogue, 38(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010607075964

- Zdeb, A. (2017). Prud and Butmir processes in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Intra-ethnic competition from the perspective of game theory. Ethnopolitics, 16(4), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2016.1143661

- Zenelaj, R., Beriker, N., & Hatipoglu, E. (2015). Determinants of mediation success in post-conflict Bosnia: A focused comparison. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 69(4), 414–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2015.1024200

- Zvaničnici RS sa ekspertskim timovima SAD i EU. (2009, October 13). RTRS. https://lat.rtrs.tv/vijesti/vijest.php?id=10345.