ABSTRACT

While many aspects of state-diaspora relations have been explored, the role that youth play in state-led diaspora outreach remains under-researched in the literature. Democratic and non-democratic states alike, however, actively target diaspora youth for a variety of reasons. In this article, we explore how and why a non-democratic state like Turkey engages with its perceived diaspora youth by focusing on the AKP regimes’ recent engagement within its European diasporas as a case study. We argue that the AKP regime has proactively bolstered transnational youth engagement policies over the last decade with the goal of creating a loyal diaspora that will serve the regime in the long run. We show that selected diaspora youth are not only empowered, but also co-opted and mobilized by the regime to ensure continued influence in the diaspora—ultimately to incorporate them into authoritarian consolidation efforts back home and to turn them into assets that lobby host country governments.

Over the last decades, an increasing number of states have been building and expanding policies to engage their diasporas (Gamlen, Citation2014). As more states around the world formulate diaspora engagement policies with the goal of transforming unorganized diaspora networks into organized entities in a top-down manner (Gudelis & Klimavičiūtė, Citation2016, p. 328), scholars seek to understand how home states engage their diasporas abroad to mobilize, remobilize or demobilize them through policies and institutions. Existing accounts generally prioritize diaspora involvement in development as well as newly established institutional mechanisms of diaspora building and management (see for instance Flanigan, Citation2017). Scholars have also focused on external voting practices as well as other forms of diaspora engagement which aim at tapping into diaspora resources for economic and political reasons (Délano & Gamlen, Citation2014; Hartmann, Citation2015; Kapur, Citation2010). As diasporas not only affect domestic politics, but occupy a unique position of serving as foreign policy tools for home states’ soft power and public diplomacy efforts abroad, home states increasingly perceive diasporas as political assets to further varying interests of the state depending on their positionality (Takenaka, Citation2020). As such, the transnational autonomy that diaspora grassroots organizations held in the past has been shrinking due to the growing employment of state-led diaspora building and shaping projects (Caglar, Citation2006). More recent studies have started focusing on how diasporas respond to such state-led diaspora policies, granting initial insights into bottom-up and top-down diaspora engagement efforts (Dickinson, Citation2017).

While home states have a variety of motivations for diaspora outreach, most accounts overlook ‘differentiations based on the sub-diaspora group characteristics and variations in policies toward them’ (Alonso & Mylonas, Citation2019, p. 476). In particular, we observe that generational differences in the diaspora remain underexplored. Studies that consider home states’ efforts to reach out to descendants of emigrants in their broader analysis of diaspora governance, do not provide a systematic study of youth-related policies (van Dongen & Liu, Citation2018; Hirt, Citation2013; Hirt & Mohammad, Citation2018). Democratic and non-democratic states around the world, nonetheless, increasingly target diaspora youth for a variety of reasons depending on their domestic and foreign policy strategies formed to perpetuate state interests (Louie, Citation2000). Yet, this outreach is predominantly explored within the context of heritage tourism or as a sub-category of diaspora policies rather than a policy subject on its own (Abramson, Citation2017; Sasson et al., Citation2011). While these accounts demonstrate the importance of heritage programs as vehicles for strengthening young diasporans’ ties with the homeland, constructing transnational solidarity as well as mutual understanding between the local population and the diasporans (Abramson, Citation2017; Cressey, Citation2006; Kelner, Citation2010; Mahieu, Citation2019a; Citation2019b; Sasson et al., Citation2011)—there is a growing need to understand efforts of home states that go beyond strengthening ties, and explore how and why home states strategically mobilize diaspora youth.

Diaspora engagement is not static and often varies according to regime type, partisan interests, the composition of diasporas and their descendants abroad, the host country’s political opportunity structures as well as diasporas’ own agency, positionality, and behavioural patterns. Scholars draw our attention to the strategies that different democratic and non-democratic home states employ by documenting the versatile forms through which different aims and objectives are advanced in governing their diasporas (Mirilovic, Citation2018). As Adamson (Citation2020, p. 151) argues, diaspora politics is ‘not just a form of transnationalism that interacts with or contests state power; it also encompasses modalities of political control.’ It is these new modalities of political control in the ‘transnational political field’ (Itzigsohn, Citation2000) that has attracted scholarly attention on this topic during the last two decades. These modalities of control, however, also vary. Indeed, recent studies highlight that non-democratic states engage in activities that go beyond fostering cultural ties, strengthening economic relations and public diplomacy efforts by implementing extraterritorial monitoring and surveillance strategies, transnational repression as well as co-optation and legitimation tactics to perpetuate authoritarian rule outside their territories (Baser & Ozturk, Citation2020; Brand, Citation2010; Tsourapas, Citation2021; Yabanci, Citation2021). In other words, state-led transnational activities of non-democratic regimes, ‘may evolve and institutionalize in some respects in line with the global trends of positive diaspora engagement, i.e. extending voting rights to citizens abroad (…) [s]imultaneously, states may engage with their citizens abroad in a negative sense which, for example in the current Turkish political climate, is proven by the purge against political opposition that extends well beyond the national borders’ (Yanasmayan & Kaşlı, Citation2019, p. 24). Recent scholarly efforts tend to focus more on negative forms of engagement such as the transnational repression of opposition groups in the diaspora while paying lesser attention to the heterogeneity of diasporic communities and how home states co-opt and mobilize different segments of the diaspora for their own purposes. Furthermore, an important sub-category that is often overlooked in these debates concerns the engagement of diaspora youth, thus begging for research exploring the ways in which non-democratic states formulate specific strategies targeting diaspora youth.

This article therefore turns to the subject of diaspora youth engagement, and asks how and to what end non-democratic home states tailor policies that specifically target diaspora youth? What kind of strategies are employed to mobilize them? By focusing on Turkey’s diaspora youth policies that have been continuously bolstered at a time when the country has experienced democratic backsliding and regime change under the AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi), hereafter AKP, we examine Turkey’s diaspora engagement with youth as a case study for several reasons. Firstly, Turkey has a sizeable diaspora in Europe and beyond. Ongoing waves of migration are a testimony that Turkey’s diasporas will keep growing (Maritato et al., Citation2021). At the same time, Turkey’s diaspora engagement policies continue to have an impact on European policymaking both domestically and internationally, especially in host countries with proportionally large diasporic populations from Turkey such as Germany, France and the Netherlands (Mügge, Citation2012). Secondly, Turkey’s diaspora engagement has been accelerated since the 2000s, in which time institutionalized forms of diaspora-building, forging, mobilizing, and governing mechanisms have been systematically introduced (Adamson, Citation2019; Aksel, Citation2019). Thirdly, Turkey’s extension of diaspora outreach policies under regime change has resulted in episodes of transnational election propaganda, import of conflict, and transnational repression within its communities causing significant controversy, especially in European political circles (Baser & Féron, Citation2022)—in particular within the context of youth triggering discussions on integration and citizenship in various host states. Although many states, from democracies to autocracies around the world uphold state-diaspora relations, host country responses to Turkey’s diaspora governance policies have been unprecedented and deserve more scrutiny. Finally, Turkey constitutes a distinct subtype of non-democratic regime and is often referred to as a hybrid regime which fits well into the category of competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky & Way, Citation2020). However, there is no consensus on how to place Turkey on the authoritarianism spectrum as the outcome of regime transformation is yet to be seen.Footnote1 Scholars such as Akçay (Citation2021) emphasize ongoing authoritarian dynamics and assert that recent processes can be interpreted as the AKP regimes’ authoritarian consolidation efforts.Footnote2 This is a trend we can both observe in Turkey’s domestic and foreign policy priorities which applies to transnational spaces as well.

In light of these dynamics of regime change, various scholars have explored how the AKP has sought increasing domestic control over youth political agency over the last two decades (Uzun, Citation2019, p. 7). Some have shown how the regime utilizes selected state-led youth organizations to build a pious and nationalistic youth to create regime-loyal youth actors who can oppose bottom-up threats to the nation and the state in the civil sphere (Yabanci, Citation2019b). Focusing on the transnational dimension of such state-led efforts to engage the youth, we suggest that Turkey further seeks to create loyal youth beyond the nation’s borders by mobilizing these parts of the diaspora. We argue that diaspora youth policies are strategically employed to serve the political agenda of the homeland’s ruling elites as a continuation of the regimes’ domestic policies at home. As such, diaspora youth’s transnational mobilization becomes a contested area as a result of a non-democratic state’s extraterritorial engagement, this also creates what Adamson (Citation2020) labels policy conundrums that transcend state boundaries when liberal and illiberal spaces overlap. Our case study grants insights into how non-democratic regimes engage their diasporas focusing specifically next generations of diasporans. While we do not suggest that Turkey is a representative case study for all non-democracies, we believe that it provides crucial insights to theorize and study how such regimes use diaspora engagement as a tool for political means that goes beyond keeping ties with nationals abroad.

Methodological Approach

To empirically assess how and to what end Turkey seeks strategic control over youth in the diaspora, we explore policies towards diaspora youth formulated after Turkey’s Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (Yurtdışı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Başkanlığı, hereafter YTB) was established in 2010. We stick to the definition of youth used by Turkey’s state institutions and examine documents and online sources which specifically mentioned youth in their title or content.Footnote3 To understand Turkey’s motivations for engaging diaspora youth and its expectations of this subset population in the diaspora, we collected publicly available data and used a two-stage qualitative content analysis method to identify emerging themes and patterns (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). In the first stage, we collected data from the YTB’s own website, Twitter and Facebook accounts and examined 150 events and initiatives that took place between 2015 and 2020, organized by the YTB and other transnational state apparatuses related to diasporas specifically targeting youth groups in Europe.Footnote4 We also traced the UETD (Union of European Turkish Democrats, hereafter UETD)’s political activities towards youth to make sense of the regimes’ local activities on the ground and to gain further insights into the mobilizational processes within the diasporaFootnote5, as well as DITIB‘s (The Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs) activities that were often co-organised with the YTB. In addition, in the second stage, we analysed newspaper articles, press statements, policy declarations, official statements, and interviews given by Turkish officials targeting youth in the diaspora. All events and initiatives were analysed to understand the state’s motivations and target groups.

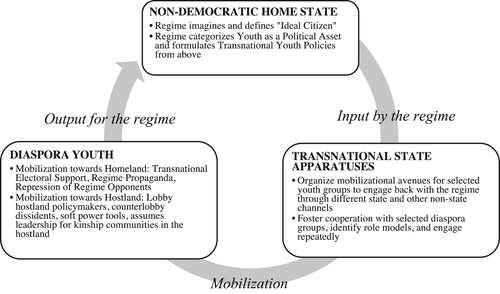

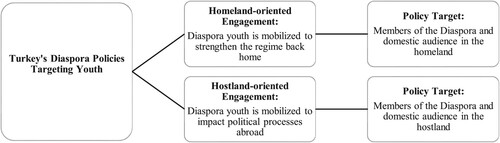

Two major themes emerged from our analysis of Turkey’s diaspora youth policy. We observed that while some activities were aimed at empowering the loyalist diaspora within the host country and repressing the dissident groups in exile, others were primarily aimed at legitimizing the current regime and strengthening the ruling elite’s attempts to cling to power in the homeland by instrumentalizing diaspora through co-optation. Therefore, we divided Turkey’s diaspora youth policies into two broad categories to further assess engagement with the diaspora and evaluate multiple motivations at play at different levels of analysis: (1) homeland-oriented engagements which are aimed at incorporating diaspora youth to regime consolidation efforts in Turkey, and (2) hostland-oriented engagements which are aimed at strengthening Turkey’s and loyalist Turkish diaspora’s positionality in host countries. Although we found occasional overlaps in these engagement strategies, we identified a clear pattern allowing us to make claims about which activities and target groups were prioritized to what end. We acknowledge that transnational processes are characterized by a triangular relationship between the home and host countries and the diaspora(s), and as such, an activity’s outreach and impact cannot be isolated from other actors and processes. Therefore, we emphasize that although these categories are helpful in understanding the scope and aims of various activities employed by the state, these activities still interact and overlap, and have implications for both diasporas and local citizens, as well as policymakers at home and abroad. We also paid attention to the timing of events and found that although certain activities (especially social media posts) were intensified during critical junctures in Turkey (such as the coup attempt in 2016) or in the world (such as COVID-19), there was a sustained interest in engaging with diaspora youth which was systematic and institutionalised. Most events such as summer schools, heritage tours, competitions and training sessions have been turned into annual events. Other indicators such as specific target groups, participation rates and other actors involved were not readily available in publicly available documents.

Transnational Mobilization of Youth by Non-Democratic Home States

Although recent accounts on diaspora governance underscore that diasporas are not homogenous entities and that states tailor multifaceted policies to deal with different segments of diaspora populations (Alonso & Mylonas, Citation2019), little attention has been given to the question of how state-led policies specifically target and shape youth who are born and raised outside their homeland’s borders. There is a burgeoning literature on diaspora youth which takes into consideration visits to the homeland (Cressey, Citation2006), identity-formation and contributions to the homeland (Horst, Citation2018), political remittance and activism (Baser, Citation2015; Cohen & Horenczyk, Citation2003; Müller-Funk, Citation2020), heritage tourism (Lev Ari & Mittelberg, Citation2008) and attitudes towards the host country (Nilan, Citation2017). A majority of these works focus on youth identity-building and activism while paying less attention to the transnational policies from above that try to shape and (re)formulate youth agency extraterritorially.

In practice, state-led initiatives targeting diaspora youth have been expanding in scope and impact over the last decades. Various home states specifically organize gatherings for diaspora youth in strategic locations. In doing so, they not only foster ties between diaspora youth and the homeland, but also build transnational links between different diaspora groups creating a large network of new generation diasporans. For instance, in 2018, the Latvian Foreign Ministry and the Latvians in Europe Association organized a series of events targeting Latvian diaspora youth in Europe. The strategy developed by the Foreign Ministry was designed to foster young people’s sense of belonging to Latvia while enabling them to contribute to the country’s economic development and promote education in the Latvian language.Footnote6 Another example is the Global Jamaican Youth Council—an initiative jointly run by the Jamaican government, diplomats and diaspora youth leaders.Footnote7 Similarly, the Commission on Filipinos Overseas prepared a plan targeting diaspora youth—Youth Leaders in the Diaspora Program (YouLead) which organizes tours introducing homeland culture and heritage to future generations.Footnote8 Other examples include an initiative developed by the Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia which organized a conference for Bosnians in the diaspora titled ‘Youth and BiH: Making Steps Together’,Footnote9 and China’s youth engagement through the Roots program (Louie, Citation2000).

Critical engagements with such initiatives mentioned above show that homeland visits are not simply touristic in nature, but rather include ‘educational elements’ (Mahieu, Citation2019b, p. 674). These visits are thus understood as a means of creating long-distance nationalism among future generations, and also of sustaining a shared identity based on common history, homeland, culture and the shared values of their ancestral home (Sasson et al., Citation2011, p. 179). As such, they reinforce self-pride and love for the homeland while also deepening a sense of belonging to ancestral heritage (Abramson, Citation2017). In this regard, studies on Taglit-Birthright Israel Tours suggest that such tours provide an opportunity for young diasporans to experience authentic Jewish public life and culture (Cohen, Citation2008) and for them to become part of a larger Jewish collective community which lies at the heart of the nation-building project (Mahieu, Citation2019b).Footnote10 In non-democratic contexts, these underlying interests become even more visible as scholars identify incentives to perpetuate state power, regime survival, legitimation, co-optation as well as monitoring and surveillance. Mahieu’s analysis of Moroccan Summer Universities demonstrates that although home state actors use apolitical framings to define these homecomings, in reality, they are a deeply political enterprise due to their content and aim. She concludes that ‘[…] these programmes should be regarded as origin state instruments of political socialization, aiming at transmitting particular orientations and values to diasporic members, in order to facilitate their mobilisation for the state’s political, economic and social projects’ (Mahieu, Citation2019b, p. 676). Hirt and Mohammad, on the other hand, show that the Eritrean government targets diaspora youth as a source of legitimation for the regime that engages them in state-led transnationalism programs with the purpose of keeping them as a source of income and instrumentalizing them as political messengers who defend the ruling party’s policies in the host countries where they reside. In other words, ‘diaspora youth is being mobilized as a generation of Eritrean patriots (…) where the youth feels as part of a national movement that defies the constant threats to their homeland’ (Hirt & Mohammad, Citation2018, p. 238). We suggest that these cases are not isolated exceptions and that more scrutiny is needed of other case studies to understand such processes in non-democratic contexts.

As illustrated above, both democratic and non-democratic states formulate policies to specifically target diaspora youth. We suggest focusing on the youth policies of non-democratic states that go beyond benevolent, cultural and educational offerings. Given that youth-oriented diaspora policies usually target diasporans of a certain age (teens to mid-twenties), such home states often target youth during periods which are crucial in the formation of political orientation (Mahieu, Citation2019b, p. 677). Thus, non-democratic home states may have additional incentives to shape youth identities both at home and abroad. We observe that numerous non-democratic states instrumentalize diaspora policies for objectives beyond public diplomacy, including regime survival, extraterritorial state control and surveillance. Recent studies highlight that non-democratic home states claim or redefine their diasporas depending on the ruling regime’s agenda and interests (Takenaka, Citation2020, p. 1131). In certain cases, regime change might even lead to a redefinition of what constitutes a diaspora altogether (Han, Citation2019). Others have showcased how such states formulate transnational-strategies and tools to take advantage of a diaspora’s patriotism and long-distance nationalism to support the regime through coercion, co-optation and legitimation (Hirt & Mohammad, Citation2018, p. 232). While recent studies on how home states repress or coerce diaspora actors shed light on the extraterritorial reach of non-democratic regimes (Adamson, Citation2020; Dalmasso et al., Citation2018; Glasius, Citation2018; Moss, Citation2016; Tsourapas, Citation2021), more needs to be done to flesh out the mobilizational processes that these states use to co-opt and mobilize different pro-regime actors in the diaspora for legitimation purposes by paying attention to generational differences.

As Yabanci (Citation2021, p. 152) rightly points out, ‘legitimation of political authority is an essential aspect of ruling as it generates cooperation from the ruled’. Legitimation strategies are widely used by non-democracies to contribute to authoritarian consolidation and resilience (Lorch & Bunk, Citation2017). Non-democratic regimes increasingly use state-led civil society for ‘authoritarian upgrading’ purposes by incentivising them to ‘coopt newly emerging social groups’ domestically as well as utilizing them to ‘conform to a global discourse of civil society that helps define the state as a legitimate member of international society’. This means that state-led civil society organisations contribute to both domestic and international legitimacy (Lewis, Citation2013, pp. 328–329). As Yabanci suggests, in the case of competitive authoritarian states, the need to incorporate civil society can be more evident as loyal civil society organisations enable them to circulate official discourse and legitimate the regime’s policies at a societal level. According to Yabanci (Citation2019a, p. 286), ‘the reason is that although democratic practices and institutions are extensively violated in CA [Competitive Authoritarian] regimes, they cannot ignore societal consent and legitimacy and rule by pure coercion.’ The same argument can be valid for non-democratic home states’ transnational efforts in creating a loyal diaspora association assemblage abroad. Indeed, as Tsourapas (Citation2021, p. 629) mentions, ‘beyond repression, authoritarian states engage in a wide variety of strategies of transnational legitimation, in an effort to sponsor sentiments of patriotism across migrant and diaspora communities abroad.’ Both elder and future generations can be employed for such purposes and home states can formulate policies which target them as a whole and separately depending on the context. In cases where non-democratic home states do not have full control over civil society organisations such as in the case of diaspora, they might utilize them through engaging in corporatist arrangements and creating patron-client relationships (Lorch & Bunk, Citation2017, p. 989).

We therefore turn to the literature on domestic, state-led mobilization of youth actors which focuses on how non-democratic states strategically create and mobilize youth to consolidate the regime. Given that non-democratic states perceive a vibrant civil society as a threat to the regime, they may choose to co-opt selected societal groups as a pre-emptive measure (Kreitmeyr, Citation2019). Considering that non-democratic states also perceive youth opposition and mobilisation as a threat to regime survival (Finkel & Brudny, Citation2014, p. 5), targeting youth in order to forge loyalty becomes a widely used strategy for such regimes. Co-optation generally occurs in the context of regime consolidation which is conceptualized as a state project to improve the regime’s capabilities to govern and seek control over society (Göbel, Citation2011). Thus, co-optation and mobilization of youth actors can be understood as a strategy to increase the state’s sphere of control in areas potentially challenging to the regime. At the same time, non-democratic states may use youth actors to ‘revitalize stalled authoritarianism’ and to signal enthusiasm and support for the regime in order to increase its legitimacy (Finkel & Brudny, Citation2014, p. 5). Youth actors may be created or co-opted not only with the goal of countering ‘democratizing’ threats from civil society and suppressing dissidents, but also to create future generations of regime loyalists who promote it abroad. In other words, pro-regime mobilization of youth and other groups can ‘signal strength and mobilization capacity in response to threats to regime survival’ and, simultaneously, be used as a ‘tool to repress mobilization efforts by the opposition’ (Hellmeier & Weidmann, Citation2020, pp. 77–78). For this purpose, non-democratic states rely on the mobilization of collective identities based on powerful ideologies such as nationalism or religion with the goal of socializing youth embedded in the state’s ideological outlook. These states use a plethora of formal and informal channels to educate and socialize loyal youth actors through youth camps, rallies, and other events. These channels are expanded to the transnational space as part of diaspora governance policies and reveal themselves in different shapes and forms depending on the context they evolve.

In this article, we make contributions to three strands of literature. Firstly, we highlight the lack of insights into state-led youth mobilization in the diaspora and contribute to emerging efforts to understand youth outreach by putting transnational youth mobilization on the agenda of the main debates in diaspora studies. Given that ‘diaspora institutions extend domestic politics beyond national borders, extraterritorially projecting state power to shape the identity of emigrants and their descendants’ (Gamlen et al., Citation2019, pp. 494–495), we suggest that there is a need to treat diaspora youth as a separate unit of analysis under the umbrella of diaspora engagement policy for several reasons: To begin with, youth actors are crucial in extra-institutional forms of political engagement such as demonstrations, protests and social movements, and they increasingly play a pivotal role as agents of social and political change. Thus, we assume that, especially in the context of non-democratic states, the state-led diaspora-building policies aimed at younger generations are not solely designed to encourage diasporic attachments to the homeland. Instead, diaspora youth policies should be understood as part of a larger strategic agenda that contributes to symbolic nation-building and regime survival outside the state’s borders. Furthermore, home states’ efforts to engage youth have to be considered as an additional investment for future gains from the diaspora, as homeland attachments cannot be directly rejuvenated with youth, and new transnational ties need to be invented and sustained in a different manner compared to policies targeting the first generation. First-generation diasporas have a lived experience of the homeland, and their transnational attachments are stronger compared to the forthcoming generations (Safi, Citation2018). Their descendants, however, have a learned experience of the homeland and their sense—of belonging takes hybrid forms that are both embedded in the home and hostland contexts (Christou & King, Citation2010). State-led diaspora policies, therefore, need to be formulated by understanding both contexts fully, from a generational perspective, and the implementation of these policies also needs to carefully take into account the complex identity formation of younger generations with multiple attachments and potential differences that distinguish their experience from their forebears. With regard to the host country context, youth diaspora and their loyalties are also a matter for policymakers who also invest in ‘incorporating them into the system of stratification into the host society’ (Zhou, Citation1997, p. 975) and engaging them into their social, political and economic agendas as their own future generation (Thomson & Crul, Citation2007).

Secondly, we further conceptualize how transnational youth engagement plays out vis-à-vis non-democratic states by analyzing the transnational dimension of state-led youth mobilization. While youth actors have traditionally been considered liberal and democratic agents in crucial moments of political change (Abdalla, Citation2016; Kuzio, Citation2006; Nikolayenko, Citation2007), there is a growing interest in conceptualizing how non-democratic states, from autocracies to illiberal democracies, implement youth policies. Among non-democratic regimes that actively mobilize pro-regime youth groups are autocracies like Iran (Cohen, Citation2006), China (Zhao, Citation1998) and Uzbekistan (McGlinchey, Citation2009). Russia, for instance, is a prominent case where the regime organizes youth movements to mobilize regime support from below (Atwal & Bacon, Citation2012; Hemment, Citation2009; Citation2015; Horvath, Citation2011). We argue that strategies on mobilising youth for non-democratic regime’s interests can be transnationalised and diaspora youth policies can also be strategically employed by these states to serve the political agenda of the homeland’s ruling elites. However, the analysis of states who cannot be considered fully authoritarian on the regime spectrum, such as Turkey, also deserves scrutiny.

Our third contribution to the literature is an empirical one. Turkey’s efforts to engage its diasporas via formulating institutions and strategies have been widely studied and have advanced our understanding of how Turkey’s extraterritorial reach has changed over time. Scholars have explored a variety of topics; including the bifocal nature of these policies in terms of positive and negative diaspora engagement (Adamson, Citation2019; Baser & Ozturk, Citation2020), the scope of reforms and strategies (Kaya, Citation2018; Yaldız, Citation2020), party-led outreach (Böcü & Panwar, Citation2022) as well as the meaning of citizenship for different groups from Turkey (Yanasmayan & Kaşlı, Citation2019). Although they have provided important insights into Turkey’s motivations in reaching out to its diasporas, an exploration of diaspora youth remains largely absent in these studies preventing us from understanding Turkey’s diaspora policies in a holistic manner. Moreover, other studies that have focused on diaspora youth were either researched before the YTB became active in the diasporic space (see Baser, Citation2014) or solely focused on the soft power potential of these actors (see Aras & Mohammed, Citation2019) and omitted other aspects related to democratic decline in Turkey and its reflection on its foreign policy priorities as well as its transnational policy strategies.

In the following, we merge existing insights into diaspora engagement and domestic mobilization of youth, to unpack the transnational processes through which Turkey’s youth engagement contributes to regime consolidation back home, and its survival in the long run. As a first step, we demonstrate that youth policies are employed to create a loyal generation of diasporans which mirrors the constituencies of the ruling party in Turkey. Here, we explore the co-optation process through which young diasporans with pre-existing nationalistic or pious orientations are selectively engaged by the regime. In a second step, we uncover Turkey’s specific objectives behind its strategic engagement with young diasporans. We show that its engagement with diaspora youth is simultaneously homeland and hostland-oriented and that Turkey leverages young diasporans depending on the needs of the regime. Our analysis suggests that co-opted and mobilized diaspora youth groups serve a broader purpose which contributes to regime consolidation by advancing multiple long and short-term interests of the regime. In terms of the short-term interests of the regime, co-opted youth may be used to repress enemies of the regime, as already highlighted in the literature. But as our analysis suggests, they can also rally or lobby on behalf of the regime, thus reproducing and increasing the visibility and legitimacy of the regime within the diaspora. Moreover, the co-optation of young diasporans also ensures the continued presence of the regime in the diaspora, thus establishing long-term influence over the diaspora that allows future engagement.

Turkey’s Transnational Youth Outreach

Turkey has gradually drifted from an illiberal democracy to competitive authoritarianism (Esen & Gumuscu, Citation2016) and is in the process of becoming a consolidated autocracy since the failed coup attempt of July 2016 (Sika, Citation2020). In parallel to these developments, Turkey has also expanded and transformed its diaspora policy significantly since the early 2000s. This stands in stark contrast to its historical neglect of its populations abroad. While diaspora engagement policies addressing the social, religious, and cultural needs of citizens abroad were developed only after the 1980 coup d’état in an effort to project a new ideology into the diaspora, the biggest shift in Turkey’s diaspora engagement took place in the early 2000s with the AKP taking a proactive approach towards its global diasporas and kin communities (Maritato et al., Citation2021; Mügge, Citation2012)—ultimately resulting in policy expansion (Aksel, Citation2019).

Since 2010, Turkey’s new diaspora and kinship governance institution is the YTB, which is an official state institution that seeks to ‘maintain ties of Turkish citizens living abroad with the homeland, preserving native language, culture and identity of Turkish citizens living abroad and strengthening social status of Turkish citizens living abroad’.Footnote11 In its first years of operation, the YTB solely focused on citizens and dual citizens abroad, but civil society projects now also include Muslim kinship communities across Europe (Akcapar & Aksel, Citation2017), which can be interpreted as the regimes’ ongoing effort to promote Turkey as the leader of Muslim communities around the globe. As part of these policies, the YTB has also developed an increasing interest in the educational, cultural and social development of diaspora youth.Footnote12 Its youth policies include cultural events, mutual exchanges, training courses and summer schools, similar to the strategies developed by countries such as Israel, Morocco and Tunisia.Footnote13 A major aspect of its engagement constitutes the preservation of Turkish language and culture among its diaspora members. Often referred to as a ‘balancing act’,Footnote14 official documents and statements by the YTB highlight the importance of retaining one’s mother tongue but specifically underline that they support bilingualism, and do not want to impede the use of the host country’s language among young people.Footnote15

In terms of cultural education, the YTB organizes ‘Anatolian Weekend Schools’ to interest youth in Turkey’s ‘cultural and historical values’.Footnote16 YTB officials justify such offerings by emphasizing that it is ‘important for young people to be successful individuals in the countries where they live, protect their cultural values and pass them to the next generation’ and suggest that this will equip them with skills to ‘contribute to both countries.’Footnote17 They also put special emphasis on the need for mobility programs and explain that weekend schools, training courses and heritage tours are organized because ‘it is important to ensure that young populations know and embrace our national, moral, historical and cultural values, and transfer these values to future generations.’Footnote18

The YTB also increasingly invests in the academic development of young diasporans through academies, scholarships, internships and leadership programs. In this context, its ‘Diaspora Academies (DA)’ have become a signature youth event.Footnote19 According to YTB officials, the academy encourages the academic development of young people in the diaspora by offering ‘support for school education by providing guidance to parents and developing language skills which allows them to become more well-rounded community leaders’.Footnote20 Scholarships categorized as ‘Citizens Abroad Scholarships’ are offered to students who study law, the Turkish language, or who conduct research on Turkey’s citizens abroad, while additional opportunities exist for students who achieve academic excellence in their respective fields.Footnote21 Since 2016, the YTB has also been organizing ‘Youth Bridges’ and ‘Youth Leaders’ programs under the banner of ‘Turkey Internships’ to strengthen the ties with diaspora youth by training them at approximately 50 different domestic institutions such as high-ranking ministries to national research councils to familiarize young diasporans with the Turkish political system.Footnote22 These programs train skilled young leaders, but also stress the importance of Turkish proficiency for their future careers, thus emphasizing the need to maintain ties to their homeland.Footnote23 Upon completion of these programs, participants are presented with a certificate during a grand ceremony organized in the Presidential Palace (Kulliye), where they meet President Erdoğan.Footnote24 These programs are complemented with free of charge ‘historical and cultural education courses, seminars, trips, workshops, motivational speeches, cultural and arts programs as well as academic perspectives.’Footnote25 For instance, gender-segregated youth camps organized in popular holiday destinations across Turkey such as Evliya Çelebi Cultural Tours which offer additional opportunities to ‘promote national values’ and instil a sense of belonging to the homeland.Footnote26 In this context, it is interesting that not only those who hold Turkish citizenship are invited to apply, but that young people who have renounced Turkish citizenship are also considered eligible.

Although the article unpacks and analyses state perspectives and policies with regard to engaging diaspora youth, it is important to say a few words about how these policies are received by diaspora youth. There is illustrative evidence that indicates that the responses are heterogenous and show variation even within the same ideological/ethnic/religious cohorts. For instance, as part of a recent oral history project on the 60th anniversary of migration from Turkey to Germany, an edited volume presenting 60 youth testimonies (3rd generation) has been published. A majority of the interviewees were mosque-attending, pious young people who are either students (higher education) or young professionals dispersed throughout Germany. Their narratives showed that they are fond of Turkey’s recent attempt to reach out to its citizens and their descendants abroad, however, they were open about their feelings with regard to the controversy that Turkey’s increasing presence in the transnational space engenders in Germany. Some mentioned that Turkey’s domestic policies and its deteriorating international image have an impact on their everyday lives as they are being questioned about their loyalties to the Turkish regime or President Erdoğan at school or in their workplaces. Some interviewees also mentioned that the AKP’s transnational election campaigns inflamed integration debates in Germany where the Turkish community continues to appear as unintegratable in the public discourse due to their loyalty to a non-democratic regime.Footnote27 Moreover, youth testimonies show that President Erdoğan’s remarks accusing Germany and the Netherlands of Nazi practices for blocking several pro-AKP rallies on their soil have put the diasporans between a rock and a hard place (see Iyi, Citation2021). More research is needed to understand the reception of such youth policies from below, however, illustrative evidence already signals that categories such as diaspora youth are never static or monolithic, and that their own agency deserves more scrutiny.

Engaging Diaspora Youth: A Matter of Empowerment or Co-optation?

On the policy level, Turkey’s diaspora youth engagement appears as an attempt to empower youth by offering skill-building activities and strengthening cultural ties between the homeland and young citizens abroad. On the ground, however, the state’s activities point to another reality which cannot be separated from Turkey’s drift into authoritarianism. Over the last decade, the AKP has not only triggered regime change in Turkey but has also reconstructed a new state identity, making Sunni-Islam ‘the regime’s key focal point’ (Öztürk, Citation2019, p. 79). In this context, President Erdoğan has also signalled intentions to raise a ‘new generation of religious youth’ in 2012, which has transformed state-youth relationships in Turkey over the last decade (Hürriyet, Citation2012). As part of this process, domestic elites ‘establish linkages with youth through the process of political incorporation, referring to institutional arrangements, public policies, and legitimating discourses in integrating youth into the political and economic structures’ (Uzun, Citation2019, p. 11). In her study of pro-regime youth organizations in Turkey, Yabanci (Citation2019b) demonstrates the AKP’s efforts to build strong ties with youth to raise citizens who are loyal to the regime. To this end, pro-AKP youth organizations rely on religion and nationalism as the main ideology in their grassroots mobilization. Accordingly, these government-oriented youth organizations not only provide services and mobilize youth but take on the responsibilities of the state. As Yabanci (Citation2019b, 28) states, government-oriented youth organizations have the capability to ‘mould youngsters’ self-perceptions, identities, political attitudes’, further aligning loyalties with the state. The growing identification between youth and the authoritarian regime is becoming more and more visible ‘as partisan incorporation of pro-government youth enabled the ruling party to mobilize a considerable number of youth with conservative backgrounds into party politics and pro-government civic activism’ which ultimately ‘(…) triggered the pursuit of militant street politics amongst pro-government youth’ (Uzun, Citation2019, p. 11).

Given that a lack of regime support and legitimacy may signal weakness (Hellmeier & Weidmann, Citation2020, p. 78), Turkey’s authoritarian turn under the AKP has significantly informed transnational efforts to mobilize youth for the regime. The YTB’s young leaders scheme reveals that the main goal behind its transnational youth engagement is to create role models within Turkey’s diasporic communities. According to the statement, role models ‘have an important influence for young people’s character-building and perspective on life’ which is why it ‘is important to guide well-equipped and educated individuals to serve as role models in terms of shaping the future of the diaspora.’Footnote28 On the ground, however, youth groups are co-opted and mobilized selectively, which is in line with Hellmeier and Weidmann’s (Citation2020) assumption that ‘autocrats mobilize their supporters selectively as a strategic response to political threats’ (Hellmeier & Weidmann, Citation2020, p. 71). In the case of Turkey, diaspora youth actors have been given a duty to protect the regimes’ interests abroad and at the domestic level, the regime increasingly uses youth ‘to counter-mobilize youth as a political force ready to confront anti-government mobilization in the future’, often based on ‘a strong attachment to and identification with the party leader Erdoğan’ (Uzun, Citation2019, p. 11) ().

As Hirt (Citation2013, p. 16) points out, diaspora youth who face obstacles to their integration in various host country contexts are eager to develop a strong identification with their homeland and tend to buy into the idea that the heroic nation that they belong to is constantly under threat. Therefore, regime propaganda disguised as diaspora engagement can give groups in the diaspora a sense of duty and purpose that is meaningful and rewarded by the homeland. Learning, imitation and replication techniques can be formulated by state elites and target diaspora youth for (re)creation of state ideology abroad (Finkel & Brudny, Citation2014, p. 9). We provide evidence for these processes and unpack it in the context of Turkey’s diaspora youth engagement. While the mere content of Turkey’s youth policies suggests neutrality, we show that the specific channels and ties that are used to shape the identity of young diasporans indicate selective engagement by the AKP in which youth is increasingly used for regime purposes. Ties built by the YTB on the ground reveal that cooperation is largely fostered through state-led governmental organizations which reach out to selected diaspora organizations such as mosque associations, and nationalistic migrant associations which pledge loyalty to the ruling elite and deliver youth programs to targeted groups. We categorize these efforts along two types of activities which have evolved simultaneously: On one hand, youth policies are used to strengthen and reinforce ties of belonging to the regime, while youth are incentivized to advance the regime’s homeland-oriented goals such as generating political gains during crucial domestic moments or containing dissent against the regime. On the other hand, once empowered, youth actors are mobilized as strategic assets for hostland-oriented goals of the regime to lobby host country governments, project soft power and suggest leadership for kinship communities in the hostland. We argue that at both levels, homeland actors aim to woo the diaspora by acknowledging youth as important assets, but also sharing material resources, and ultimately perpetuating identification with and support for the regime ().

Homeland-Oriented Youth Engagement

Since 2014, the regime has been interested in a continuous supply of electoral legitimacy from domestic and foreign constituencies. Given that the overall vote share across European host country contexts has largely contributed to AKP’s domestic victories (Sevi et al., Citation2020), the maintenance and formation of loyal ties between the home state and diasporans appear to have become a pivotal goal vis-à-vis young diasporans. Therefore, youth programs offered by the YTB can be understood as an effort to meet the homeland-oriented goal of regime consolidation. To meet this goal, Turkey seeks to extract political remittances from diaspora youth by mobilizing regime-loyal youth during crucial domestic elections, against state opponents, and propagating the regime in the diaspora.

Moreover, the YTB has been fostering selective ties with religious and nationalistic groups in different issue areas which advance the regime’s grip over its diaspora youth. As such, it has worked closely with religious associations including local youth branches of mosque associations in Germany or youth associations associated with Millî Görüş networks across Europe (Yeni Akit, Citation2015). In this context, the YTB has been bringing members of selected youth associations to Turkey by offering cultural homeland tours or educational programs along with official visits to the YTB’s headquarters, thus strengthening ties between the homeland and young diasporans.Footnote29 In fact, students from Germany who were recruited and participated in the YTB’s educational seminars in Turkey, confirm that the target audience for these educational and cultural programs is generally quite homogenous, and composed of religious or nationalistic diaspora youth with similar world views (Author, forthcoming).

Ties formed with religious and nationalistic youth groups have thus allowed the regime to mobilize youth for several homeland-oriented purposes. The establishment of the Union of European Democrats (UETD) in 2004 and the subsequent establishment of its local youth organizations (UETD Youth) in 2014 played a pivotal part in advancing the mobilizational goals of the regime. Especially after the institutionalization of expatriate voting rights, UETD Youth organized transnational election campaigns for the AKP and encouraged expatriate voting within the diaspora. For instance, Erdoğan’s first mass rally held in Berlin, Germany on 5th February 2014 was organized by the UETD’s youth wing.Footnote30 Its members also actively campaigned for a ‘yes’ vote in the 2017 constitutional referendum which was a pivotal political moment for regime change in Turkey. After the victory, UETD Youth openly celebrated the regime by organizing small rallies in favour of Presidentialism under Erdoğan (Hofman, Citation2017).

Diaspora youth have also been involved in spreading regime propaganda abroad. UETD youth outlets across Europe, for instance, have been promoting the AKP’s regime ideology and glorifying Turkey’s Ottoman heritage by offering Ottoman language courses as well as Ottoman history seminars to young diasporans.Footnote31 In addition, youth actors are further recruited into commemorating the regime’s founding myths and symbolic dates. As such, the 2016 coup attempt has become an intrinsic element of the regime’s national narrative and the YTB has been actively organizing numerous commemorative events aimed at wooing diaspora youth.Footnote32 UETD youth has also played a role in encouraging local participation during commemorative events across European cities such as Düsseldorf, Brussels, London and Vienna to perpetuate regime loyalty abroad (Hürriyet, Citation2021). According to the organization, youth participation in such commemorative events serves the purpose of ‘keeping the memory of the traitorous coup night alive’.Footnote33

Youth have also been integral to the regime’s efforts to mobilize against, threaten or repress regime opponents abroad. In this context, diaspora youth organized multiple protests during critical moments in support of the regime. For instance, the UETD’s youth associations prepared a declaration in support of the regime during the Gezi protests in 2013.Footnote34 During Turkey’s military intervention in Afrin in 2018, UETD networks coordinated solidarity protests and prayers across Germany, the UK, Denmark, and Bosnia in support of Operation Olive Branch (TRT, Citation2018). These protests were largely organized against Kurdish groups opposing the intervention (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Citation2018). Various dissident diaspora youth including young Kurdish and Alevite activists have indeed confirmed such encounters with pro-regime groups, and reported organized counter-mobilization by young members of the diaspora affiliated with religious associations (Author, forthcoming).

Youth actors are also involved in the regime’s transnational repression efforts. In fact, the YTB’s president stated at one of the ‘Turkey Scholarship’ events in Bosnia that alumni associations should be formed and used as tools in the war against the Gülen Movement abroad, which have been labelled as terrorists abroad (Bıogradlıja, Citation2018).Footnote35 While UETD youth and other diasporic youth groups close to the regime have not been involved in repression on behalf of the regime, the activities of Ottoman Germania (Osmanen Germania)—an informal gang banned in Germany—constitute a prominent example of repression via youth (Bewarder, Citation2018). German intelligence reports and media claim that the group recruited Turkish-German youth from the streets and involved them in violent acts against regime opponents in Germany (Fischhaber & Klasen, Citation2018). Reports further indicate organizational links with prominent AKP politicians who instructed the group to organize protests and strike fear into dissidents (Winter, Citation2017).

Hostland-Oriented Youth Engagement

The formation of close ties with selected youth groups not only furthers the consolidation and survival of the regime but also serves Turkey’s hostland-oriented goals. By encouraging conservative and nationalistic youth to take part in hostland politics, the regime seeks to create and engage a new generation of diasporans to lobby foreign governments with hopes of ameliorating bilateral relations with host countries. To achieve this goal, educational offerings from the YTB such as targeted skill-building and professionalization seminars and scholarships are used to create proponents of the regime abroad. Themes like integration, Islam in Europe and a self-declared fight against Islamophobia serve the purpose of advancing Turkey’s influence abroad.

Since 2013 there have been countless examples in which the regime has built influence abroad through the use of youth groups. In fact, the UETD’s youth wing has been encouraging diaspora youth to ‘join politics to determine not only the next Turkish government but also shaping civil society in Germany’ in the immediate aftermath of the Gezi protests.Footnote36 This task was later taken up by the YTB which started to train selected diaspora youth to better respond to policy issues in the host country. As such, UETD youth as well as youth networks of the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DİTİB) have promoted seminars in active cooperation with the YTB. In 2014, for instance, UETD youth members were sent on a visit to the European Parliament in Brussels to expose youth to European and foreign policymaking and ensure their active participation in hostland politics.Footnote37 University student networks close to DİTİB youth associations have also been increasingly considered a target audience for the YTB’s offers to train young university students in the diaspora.Footnote38 Offerings have included various professionalization activities such as writing academies, political communication seminars and journalism programs (Yüzbaşıoğlu, Citation2020).

As part of the regime’s lobby-building efforts, young diasporans further received education on political and social issues pertaining to the role of Islam in Europe to strengthen their identity as Muslims. As such, the YTB’s political education offerings have heavily focused on issues such as racism and Islamophobia in Europe, while also encouraging migrant organizations to monitor attacks against members of its diasporas in Europe.Footnote39 For instance, the YTB organizes Human Rights Education programs where young diasporans are educated on how to report human rights violations, fight against discrimination and hate speech as well as Islamophobia.Footnote40 Thus, the strategic emphasis on their positionality as religious minorities in their respective host countries can be seen as an attempt to further capitalize on their identity and mobilize diaspora youth.

Diasporic organizations with large youth networks have followed suit in prioritizing the AKP’s pro-Islamic and nationalistic agenda on the ground. UETD youth, for instance, started to offer various academic seminars called ‘Muhabbet Halkaları’ on topics such as ‘Muslim Youth in Europe’ Footnote41 or ‘Muslims in Europe’Footnote42 as early as 2014. Increasingly, religious associations in Germany seem to adhere to the regime’s agenda by actively combating Islamophobia through street-level politics. In 2015, for instance, when right-wing protestors started to gain leverage in German politics, young diasporans close to the Turkish government such as UETD youth, DİTİB, Millî Görüş and various other religious or nationalistic diasporic organizations participated in multiple protests against racism and Islamophobia in Germany.Footnote43 According to a youth organization in Germany working closely with the consulate, foreign representations further play a key role in encouraging youth to speak up against growing discrimination and racism against immigrants from Turkey (Author, forthcoming).

These groups have further attempted to influence host country policies towards Turkey. This has helped Turkey to make use of its diasporas as another soft power tool and has come to the fore during debates on the acknowledgement of the Armenian genocide by various host countries in Europe. In France, the introduction of a bill to punish the denial of the Armenian genocide in January 2012 triggered mobilization by young diasporans close to the regime (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Citation2012). Efforts to mobilize against the law were coordinated by the Committee of Coordination of Turkish Muslims in France (Comité de Coordination des Musulmans Turcs de France) whose leadership holds close ties to the AKP regime (Graff, Citation2017). In 2016, when the German parliament passed a resolution recognizing the events of 1915 as genocide, nationalistic groups including Grey Wolves and the UETD as well as their youth organizations mobilized against the decision (Jansen, Citation2016).

Turkey’s youth outreach has not gone unnoticed by host country policymakers. In Europe, the YTB’s activities in the diaspora are increasingly perceived as a partisan tool of the regime. The fact that the YTB’s president was himself the head of the AKP’s youth branch before being appointed to this role, has perpetuated those suspicions. Moreover, YTB officials also acknowledge that Turkey’s activities in the diaspora cause mistrust among European policymakers (Ünal, Citation2015). Especially following the coup attempt in 2016, journalists and academics claimed that the YTB had been cooperating with Turkey’s Intelligence Service to monitor and control dissidents abroad (Bozkurt, Citation2020). Furthermore, reports published by the German domestic intelligence service claim that the regime is using DİTİB’s mosque communities abroad as instruments of state propaganda and repression. For instance, leaked pictures of youth wearing Turkey’s army uniforms in mosques celebrating and praying for Turkey’s victory over the Kurdish PYD in Afrin, ‘are considered to be acts of significant wrongdoing that deepen the polarization of German citizens of differing ethnic backgrounds’ (Aydin, Citation2019).

As a result, suspicion has been growing towards diasporic organizations with large youth networks such as the ultranationalist Grey Wolves Movement due to its links to the regime which has resulted in bans or calls for their investigation across host country contexts. While Austria banned the nationalistic salute of the group in 2019 (Kiyagan, Citation2019), the group has been fully outlawed in France (Deutsche Welle, Citation2020). Similarly, German policymakers are also pushing for a ban of the organization and its 170 affiliated associations due to growing concerns over potential violence, and negative effects on Germany’s integration efforts toward young immigrants (Tastekin, Citation2020). Thus, Turkey’s transnational youth policies which ostensibly promote host country integration and empowerment on the policy level, increasingly put the diaspora between a rock and a hard place as host country policymakers perceive the effects on the ground with growing scepticism increasingly considering Turkey’s efforts in the diaspora as authoritarian co-optation.

Concluding Remarks

As Lewis (Citation2013, p. 330) argues ‘in most cases, the contemporary authoritarian state is unable to maintain power simply through the maintenance of a closed, monolithic, homogeneous state order (…) [i]nstead, an assemblage of formal and informal networks, economic and financial flows, and discursive, symbolic, and performative dynamics all serve to constitute the contemporary authoritarian state.’ Our research shows that such informal networks can also be put in force transnationally and aim at mobilizing first and consecutive generations for a cause set by the homeland elites. As Burnell (Citation2006, p. 548) suggests, non-democratic states, from illiberal democracies to autocracies, might ‘enjoy some measure of legitimacy among social groups or strata even while they may possess no legitimacy at all among other subjects’. He further highlights that, ‘for some regimes international legal recognition and support, whether material and/or symbolic—that is to say external legitimation—are very valuable to the manufacture of legitimacy at home’ (Burnell, Citation2006, p. 549). In line with this, our study reveals how non-democratic regimes can forge such external legitimacy with the help of diasporans who are supportive of the regime. In other words, the presence of symbolic or material support from the diaspora strengthens the regime at home by underlining the power of the autocrat and the legitimacy of the regimes’ rule. As such, we not only show how but provide preliminary insights as to why non-democratic home states may engage with young diasporans. By unpacking how diaspora youth are instrumentalized for co-optation and legitimacy purposes, we therefore contribute to recent debates on the transnational dimensions of authoritarianism. In particular, the exploration of Turkey’s transnational youth policies constitutes a crucial case in demonstrating how non-democratic regimes disseminate their imagery of loyal and ideal citizens transnationally to strategically empower, co-opt and mobilize diaspora youth to realize domestic aspirations of regime building and authoritarian consolidation. Thus, non-democratic states’ attempts to seek control over civil society for legitimation purposes do not halt at the nation’s borders. Our research reveals that policies extended to diaspora youth reflect the regime’s interest in shaping a new generation of diasporans and perpetuating their loyalties to the regime abroad—a similar strategy to that applied towards youth back in Turkey. Although the YTB’s youth initiatives and programs appear to empower young diasporans through educational skill-building activities and cultural programs that strengthen ties with the home state, a closer look at cooperation patterns between the state and diaspora actors on the ground reveals that Turkey’s investment in diaspora youth has been strategically selective. Our analysis suggests that the YTB engages state-led non-governmental organizations such as the UETD and loyal diasporic civil society organizations to propagate the regime’s message to young diasporans in Europe. In turn, these groups benefit from the regime’s allocation of state resources with the expectation that future generations of diasporans will return the favour and contribute to the survival and legitimacy of the regime from abroad.

We have divided Turkey’s engagement policies into two categories depending on the priorities given to the target groups. We observed that, on one hand, the regime actively engages in state-led identity-building efforts which seek to form a regime-loyal youth of ideal citizens who obey and serve the regime by offering cultural homeland tours and educational programs which situate them as part of the homeland, and the new Turkey built under the AKP. Identification with the regime is further strengthened by partaking in political activities such as organizing and supporting transnational election campaigns, encouraging expatriate voting as well as contributing to Turkey’s other nation-branding activities such as cherishing Ottoman heritage and history or commemorating the thwarting of the July 15th coup d’état. In addition, youth actors are also being increasingly integrated into the regime’s transnational repression efforts and actively partake in countermobilization and repression activities against enemies of the state, which further bolsters their identification with the regime. On the other hand, pious and nationalistic youth are further mobilized to represent and communicate regime interests to host country policymakers. As such, the YTB and its local civil society partners actively engage pious and nationalistic young diasporans through political educational activities to nurture political leaders and elites of the future who can operate on behalf of the regime. Often, these programs focus on combating Islamophobia and racism across European host country contexts with the goal of creating an image of Turkey as the new leader of the Muslim world. In this context, selected diaspora youth are positioned as Muslim minorities and actively push for the accommodation of their demands through institutional and extra-institutional channels in the host country. In addition, young diaspora networks also further defend and promote Turkey’s position on important foreign policy issues.

What happens when there is a contradiction between these priority areas? How do they interact with each other? First of all, we have found that due to the transnational nature of dynamics that take place within the home state—host state—diaspora nexus, each intervention in the transnational political field has implications for all actors involved. Therefore, although youth engagement policies were designed in Turkey, and projected on young diasporans, they also triggered a discursive response from political actors in the host country. Moreover, lobbying and soft power activities which are mostly aimed at influencing political circles in the host country help to elevate a leader’s legitimacy, image and charisma back home. This triangular relationship has manifested itself in various interaction corridors between the actors involved and necessitates a transnational approach that considers all dimensions at once. Having said that, we observed such complexities as two-forged strategies formulated by the home state: homeland and hostland-oriented policies and practices towards the youth. In some cases, we observed that domains interact and overlap, while contradictions occurred in other spheres. For instance, the regimes’ proactive engagement with the diaspora during national elections and referenda caused uproar in host societies. Rather than de-escalating, Erdoğan opted for rekindling tensions to signal to domestic and transnational constituencies that European countries prohibit Turkey’s progress. When authoritarian consolidation became more important at certain moments, rather than employing soft power or public diplomacy, the regime did not hesitate to opt for homeland-oriented activity and goals, which in some cases put the diasporans in a difficult position as mentioned above. When Turkey needed economic or military support from host countries, the regime increased host country-oriented activities to lobby and propagate the regime. Other controversies around the regimes’ reach into mosque communities or its relations with nationalist youth groups such as the Grey Wolves, which tend to be treated with suspicion and racist discourses in various European host countries, demonstrate that both domains are highly politicized by all actors. Moreover, our analysis also revealed that home country policymakers can utilise each domain simultaneously. During critical junctures where contradiction occurs between the two domains, policymakers are faced with choices to perpetuate their power, legitimacy, and sovereignty at home to consolidate the regime. In these cases, diaspora interests can be side-lined by homeland actors which begs for further scrutiny of diaspora actors’ own perspectives and host state policy responses to such dynamics.

This study only constitutes a first insight into the topic, and therefore comes with limitations. Future research should focus on how authoritarian states’ transnational youth policies are received by target groups within the diaspora, and it should also consider how excluded or repressed youth groups within the diaspora reclaim agency and challenge the regimes’ engagement from below. Scholars should pay attention to various actors involved, the temporality and spatiality of diaspora outreach activities and participation rates and profiles. Such inquiries, however, require in-person fieldwork and in-depth interviews with diaspora youth and may face certain limitations given the sensitivity of the topic (Ahram & Goode, Citation2016). In addition, further exploration of comparative case studies of other sub-types of authoritarianism such as transnational efforts by China, India or Russia to forge ties with young citizens abroad would grant external validity to the insights produced in this paper. Lastly, scholars should also continue to study how democratic host states respond to non-democratic states’ engagement with diaspora youth on their soil.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants of the panel ‘Turkey as a Migration State’ held at the Annual Convention of the International Studies Association (ISA) in 2021 (Las Vegas, US) and Durham University’s Global Security Institute staff for their valuable feedback. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the previous versions of this article. All authors contributed equally to this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Currently, Turkey is listed as ‘Not Free’ by the Freedom House Index, as a ‘Moderate Autocracy’ by the Democracy Matrix and a ‘Hybrid Regime’ by the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index.

2 Drawing from the existing literature, Akçay (Citation2021, p. 94) defines authoritarian consolidation as ‘as a transition process in which the new regime is able to gain legitimation through increasing its problem-solving capacity, and implementing populist discursive strategies, along with the coercive measures’.

3 YTB’s youth definition differs according to the activity organized. For youth camps in Turkey, they limit the eligibility criteria to ages between 18 and 23 (see: https://www.ytb.gov.tr/genclikkamplari/). Other youth activities set age limits between 18 and 22 (https://www.ytb.gov.tr/yurtdisi-vatandaslar/genclik-kamplari). For cultural heritage tours, the age limit is defined between 14 and 29 (https://www.ytb.gov.tr/guncel/evliya-celebi-kultur-gezileri-programi).For Diaspora Academies, the limit is 20 and 27 (https://www.ytb.gov.tr/diasporagenclikakademisi/index.html). Therefore, we adopt the YTB’s age criteria when referring to youth in this article and assume a definition of youth in the diaspora between 14 and 30 years old.

4 YTB’s activities have been collected from their official website along with an additional news scan of items that appeared in the media.

5 Formerly known as the Union of European Turkish Democrats (UETD) the organization was founded in Cologne, Germany in 2004. In May 2018, the organization renamed itself to Union of International Democrats (UID). While the UID operates in 17 countries and upholds 253 representations across these countries, the majority of its representations operate within the European Union.

10 Abramson (Citation2017) has challenged these assumptions, claiming that the tours perpetuate diasporic identity rather than Jewish identity per se.

19 For the kinship communities the YTB organizes ‘Next Generation Academies’, see: https://www.ytb.gov.tr/duyurular/gelecek-nesil-akademisi?fbclid=IwAR1BDwTsSLlktQ1ZTXa9uxx1n9dINCgNIqOxnTjiyHMCHAVcLo6SunAdjPw

26 https://www.ytb.gov.tr/genclikkamplari/ and https://www.ytb.gov.tr/guncel/evliya-celebi-kultur-gezileri-programi

30 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2014 (Ocak), 12.

31 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2015 (Ocak), 10.

37 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2014 (Aralik), 7.

41 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2014 (Aralik), 3.

42 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2015 (Ocak), 7.

43 UETD Genclik Kollari Faaliyet Raporu 2015(Ocak), 6.

References

- Abdalla, N. (2016). Youth movements in the Egyptian transformation: Strategies and repertoires of political participation. Mediterranean Politics, 21(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081445

- Abramson, Y. (2017). Making a homeland, constructing a diaspora: The case of Taglit-Birthright Israel. Political Geography, 58, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.01.002

- Adamson, F. B. (2019). Sending states and the making of intra-diasporic politics: Turkey and its diaspora (s). International Migration Review, 53(1), 210–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318767665

- Adamson, F. B. (2020). Non-State authoritarianism and diaspora politics. Global Networks, 20(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12246

- Ahram, A. I., & Goode, J. P. (2016). Researching authoritarianism in the discipline of democracy*: authoritarianism in the discipline of democracy. Social Science Quarterly, 97(4), 834–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12340

- Akcapar, S. K., & Aksel, D. B. (2017). Public diplomacy through diaspora engagement: The case of Turkey. Perceptions, 22(4), 135–160.

- Akçay, Ü. (2021). Authoritarian consolidation dynamics in Turkey. Contemporary Politics, 27(1), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1845920

- Aksel, D. B. (2019). Home states and homeland politics: Interactions between the Turkish state and its emigrants in France and the United States. Studies in migration and diaspora. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Alonso, A. D., & Mylonas, H. (2019). The microfoundations of diaspora politics: Unpacking the state and disaggregating the diaspora. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(4), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1409160

- Aras, B., & Mohammed, Z. (2019). The Turkish Government scholarship program as a soft power tool. Turkish Studies, 20(3), 421–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2018.1502042

- Atwal, M., & Bacon, E. (2012). The youth movement nashi: Contentious politics, civil society, and party politics. East European Politics, 28(3), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2012.691424

- Aydin, Y. (2019). Turkey’s diaspora policy and the ‘DİTİB’ challenge. Turkey Scope - Insights on Turkish Affairs, 3(8), 1–6.

- Baser, B. (2014). The awakening of a latent diaspora: The political mobilization of first and second generation turkish migrants in Sweden. Ethnopolitics, 13(4), 335–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2014.894175

- Baser, B. (2015). Diasporas and homeland conflict: A comparative perspective. Routledge.

- Baser, B., & Féron, É. (2022). Host state reactions to home state diaspora engagement policies: Rethinking state sovereignty and limits of diaspora governance. Global Networks, 22(2), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12341

- Baser, B., & Ozturk, A. E. (2020). Positive and negative diaspora governance in context: From public diplomacy to transnational authoritarianism. Middle East Critique, 29(3), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2020.1770449

- Bewarder, M. (2018). Ein Aus Ankara Gelenkter Extremismus. Die Welt, Retrieved July 10, 2018, from https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article179107784/Verbot-der-Osmanen-Germania-Erdogans-krimineller-Arm-in-der-Bundesrepublik.html

- Bıogradlıja, L. (2018). Mezun Dernekleri FETÖ Ile Mücadelede Ciddi Enstrüman. Anadolu Ajansi, Retrieved September 24, 2018, from https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/dunya/mezun-dernekleri-feto-ile-mucadelede-ciddi-enstruman/1262994

- Bozkurt, A. (2020). Turkish Intelligence Runs Covert Recruitment Programs in Diaspora in Europe. Nordic Monitor, Retrieved September 20, 2020, from https://nordicmonitor.com/2020/09/turkish-intelligence-runs-covert-recruitment-programs-in-diaspora-in-europe/

- Böcü, G., & Panwar, N. (2022). Populist diaspora engagement. Diaspora Studies, 15(2), 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1163/09763457-bja10013

- Brand, L. A. (2010). Authoritarian states and voting from abroad: North African experiences. Comparative Politics, 43(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041510X12911363510439

- Burnell, P. (2006). Autocratic opening to democracy: Why legitimacy matters. Third World Quarterly, 27(4), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590600720710

- Caglar, A. (2006). Hometown associations, the rescaling of state spatiality and migrant grassroots transnationalism. Global Networks, 6(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00130.x

- Christou, A., & King, R. (2010). Imagining ‘home’: Diasporic landscapes of the Greek-German second generation. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(4), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.001

- Cohen, E. (2008). Youth tourism to Israel: Educational experiences of the diaspora. Tourism and cultural change 15. Channel View Publications.

- Cohen, E. H., & Horenczyk, G. (2003). The structure of attitudes towards Israel-diaspora relations among diaspora youth leaders: An empirical analysis. Journal of Jewish Education, 69(2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0021624030690208

- Cohen, J. (2006). Iran’s young opposition: Youth in post-revolutionary Iran. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 26(2), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2006.0031

- Cressey, G. (2006). Diaspora youth and ancestral homeland: British Pakistani/Kashmiri youth visiting Kin in Pakistan and Kashmir. Brill.

- Dalmasso, E., Del Sordi, A., Glasius, M., Hirt, N., Michaelsen, M., Mohammad, A. S., & Moss, D. M. (2018). Intervention: Extraterritorial authoritarian power. Political Geography, 64, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.07.003

- Deutsche Welle. (2020). France Bans Turkish Ultra-Nationalist Grey Wolves Group, Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://www.dw.com/en/france-bans-turkish-ultra-nationalist-grey-wolves-group/a-55503469

- Délano, A., & Gamlen, A. (2014). Comparing and theorizing state–diaspora relations. Political Geography, 41, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.05.005