Abstract

This study explores the link between ethnic divides and affective polarization by proposing that individual differences in outparty affect towards ethnic parties are associated with either prejudice against the ethnic group or dissatisfaction with minority accommodation at the sociotropic or egotropic level. We test this proposal through a case study of the Swedish People’s Party in Finland. Using survey data, we find that sociotropic concerns have the strongest link to affective evaluations of the ethnic party. However, among right-wing populist voters, egotropic concerns also stand out. The association between ethnic prejudice and evaluations of the SFP was weak and ambiguous.

1 Introduction

In recent years, research on mass polarization has increasingly focused on affective, rather than ideological, distances between political parties—a phenomenon known as affective polarization, introduced by Iyengar et al. (Citation2012). Scholars have thoroughly explored the drivers behind affective polarization, but one aspect that has received little attention thus far is the link between ethnic divisions and partisan affective polarization.

A country-level comparative study of affective polarization in Europe (Reiljan, Citation2020) suggested that such a link exists; affective polarization appears to be higher in countries with ethnic divisions and ethnic partisan representation than mere ideological polarization would predict. Reiljan’s observation was confirmed by Bradley and Chauchard (Citation2022) in their study of the link between ethnic representation and affective polarization in party systems. To explain this, they draw on Chandra (Citation2006), who observed that ethnic identities are more visible and ‘sticky’ than other identities, and connect this observation to findings that the alignment of partisan and social identities drives affective polarization (Mason, Citation2016). Nonetheless, their material does not allow for a closer examination of the mechanisms that transform political and societal ethnic conflict into heightened partisan polarization in countries where ethnic parties are present. The aim of our study is to advance the knowledge about these mechanisms.

We propose that the politicization of ethnicity might increase affective polarization not only through the identity-based mechanisms that Bradley and Chauchard (Citation2022) draw upon but also through disagreement on policy issues concerning accommodation of the interests of ethnic groups. Such disagreements, we believe, are more likely to be salient in a party system where ethnic parties are present. We find inspiration for this line of reasoning in Bustikova (Citation2014), who suggested in her study of post-communist countries that support for radical right-wing parties is often derived not from direct prejudice against ethnic minorities, but from discontent about accommodation of their interests. If such discontent may lead to increased support for radical right-wing parties in certain settings, we argue that it could also be expected to translate into increased dislike of ethnic minority parties.

Unlike Bustikova (Citation2014), who studies temporal changes in electoral success of parties, we focus on individual-level attitudes towards parties and ethnic minority issues. We argue that individual discontent can occur at two levels: egotropic and sociotropic. These concepts are derived from the field of economic voting (Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Citation2000) and refer to concerns about the personal and societal consequences of policies, respectively. In the context of accommodating ethnic minorities’ interests, this translates into a distinction between attitudes about the desirability of minority accommodation on a collective level, and its possible advantages or disadvantages on a personal level. At the same time, we remain open to the possibility that ethnic prejudice can act as a source of polarization.

The relationship between the egotropic, sociotropic and prejudicial dimensions, and attitudes towards ethnic minority parties is examined through a case study of Finland, which is one of the countries studied in Bradley and Chauchard (Citation2022). Finnish society has been divided linguistically between a Finnish-speaking majority and Swedish-speaking minority since before Finland’s independence in 1917 (McRae, Citation1999). This divide has been addressed through a policy of bilingualism at the national level in combination with rights and obligations that vary at the local level depending on the relative size of each linguistic group. Swedish speakers predominantly support the Swedish People’s Party (Svenska Folkpartiet, SFP) (Grönlund, Citation2011; Sundberg et al., Citation2005) and, as we will argue, the party fits the criteria of an ethnic party and is thus likely to be a target of affective spillover from both egotropic and sociotropic discontent, as well as ethnic prejudice. Furthermore, the SFP is generally considered a moderate party and has been a recurring partner in governing coalitions in Finland, which means that the ethnic minority it is not being systematically excluded from power—something that could aggravate conflict (Bradley & Chauchard, Citation2022). This makes Finland and the SFP an excellent case to identify to what extent our proposed mechanisms translate into affective partisan polarization.

In the next sections, we discuss the theoretical framing of the study and the political context of Finland. In conjunction with this, we elaborate on our initial argument about an association between the presence of ethnic minority parties and affective polarization and formulate more precise research questions that will guide the analysis.

2 Theory

Affective Polarization Between Parties

The concept of affective polarization refers to the idea that antagonism between parties can manifest not only as increasing divergence between ideas or policy preferences but also through intergroup affect. Using spatial metaphors, political groups can thus be separated not only by ideological distance but also by social distance. When conceptualizing affective polarization, Iyengar et al. (Citation2012) drew on the concepts of ingroups and outgroups described by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). According to this theory, individuals develop a cognitive bias in favour of the group they identify with and a sense of antagonism against rival groups.

Using this approach to gauge mass polarization, Iyengar et al. (Citation2012) found increasing affective polarization in the United States, especially in the form of stronger negative evaluations of the opposing party, whether Democrat or Republican. Subsequent studies have shown that this trend has accelerated further in the USA (Boxell et al., Citation2024; Iyengar et al., Citation2019; Iyengar & Krupenkin, Citation2018; Iyengar & Westwood, Citation2015). Starting with the work of Iyengar et al. (Citation2012), three main approaches have characterized explanations of affective polarization. The first approach explains affective polarization as driven by principled dislike based on ideological differences (see, e.g. Bougher, Citation2017; Rogowski & Sutherland, Citation2016). The second approach sees a driver of affective polarization in the identity-based ingroup–outgroup dynamic described by the social identity theory (Huddy et al., Citation2015; Huddy et al., Citation2018; Mason, Citation2015, Citation2016). The third approach accounts for contextual factors, such as election campaigns (Hansen & Kosiara-Pedersen, Citation2017; Hernández et al., Citation2021).

In the Finnish setting, affective polarization has only recently gained scholarly attention. Historically, Finland has experienced deep polarization, with a civil war directly following the country’s independence in 1918 and strong ideological polarization in the following decades. However, by the 1980s, this state of affairs had changed into the consensus type of politics that modern Finland has traditionally been known for (Karvonen, Citation2014). Recent studies show that affective polarization has nonetheless steadily increased in Finland since the turn of the millennium (Kawecki, Citation2022a; Kekkonen & Ylä-Anttila, Citation2021), albeit polarization levels are still moderate compared to those in other European countries (Kawecki, Citation2022b; Reiljan, Citation2020; Wagner, Citation2021).

Ethnic Conflict and Partisan Affective Polarization

How does ethnic conflict fit into the framework of affective polarization? For conceptual clarity, it is important to differentiate between partisan affective polarization, the focus here, and other types of polarization based on social identity. For example, a country can be characterized by strong social polarization and prejudice around ethnic identities, but this conflict might not manifest in the party system in the form of affective polarization between parties. Neither does ethnic conflict necessarily manifest through the appearance of specifically ethnic parties—questions about ethnicity and minority rights can be raised by non-ethnic parties. However, when ethnic parties are present, these parties are likely to be directly associated with the interests of the ethnic group they represent.

Ethnic conflict can take on multiple forms in diverse settings—from violent struggle to democratic disagreement about the institutional and constitutional solutions designed to facilitate peaceful co-existence. Finland belongs to the latter category, as the ethnic conflict in question is linguistic in nature and involves a numerical minority of Swedish speakers in a country where the majority speaks Finnish. The lion’s share of Swedish-speaking citizens supports a small ethnic party, the SFP. Before we describe this setting and the background, it is important to note that there are no other explicitly ethnic parties in Finland. We can thus identify three types of partisan relationships that could become affectively polarized due to the ethnic divide: (a) the ethnic minority party contributes to polarization by rallying supporters around ethnic identity in opposition to non-ethnic parties; (b) non-ethnic parties contribute to polarization by mobilizing their supporters in opposition to the ethnic minority party; (c) the salience of ethnic conflict caused by the existence of the ethnic minority party drives polarization between non-ethnic parties, for example through the question of whether minority interests should be accommodated or not.

In the setting at hand, we are primarily concerned by the second relationship, i.e. how supporters of non-ethnic parties contribute to affective polarization through hostility towards the ethnic minority party, driven by either ethnic prejudice or by egotropic or sociotropic discontent with accommodation of minority interests. We believe that this relationship will have the greatest effect on overall polarization in the party system: it arguably matters more from a system perspective if broad sections of the electorate are strongly hostile towards a particular, albeit small, party, than if supporters of one small party are hostile towards other parties.

Having made these clarifications, we can now ask our initial research question with greater precision: to what extent do egotropic attitudes, sociotropic attitudes and ethnic prejudice among supporters of non-ethnic parties have an impact on affect towards the ethnic minority party?

Egotropic and Sociotropic Attitudes

In studies of economic voting, it is common to differentiate between sociotropic and egotropic voting patterns (Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Citation2000). Sociotropic voting refers to voting based on the nationwide state of the economy, while egotropic voting is behaviour based on one’s personal economic situation, also referred to as pocketbook voting. The differentiation between sociotropic and egotropic behaviours is not limited to economic issues. In a broader sense, it can refer to whether political attitudes and behaviours are being driven primarily by concerns or evaluations of a private nature, or of a more general, societal nature. Such adaptions can be found in studies of political trust during the COVID-19 crisis (Rump & Zwiener-Collins, Citation2021), the effects of globalization and the intention to vote (Beesley & Bastiaens, Citation2022), and sociotropic uncertainty and multiple political identification (Steenvoorden & Wright, Citation2019).

In an adaption close to our focus on ethnicity, Hainmueller and Hopkins (Citation2014) review research on attitudes to immigration policy. Here, egotropic explanations for attitudes to immigration focus on its consequences for the individual, such as labour market competition, while sociotropic attitudes concern the economic or cultural impact of immigration on the country as a whole. Prejudice towards immigrants as a group is viewed as a subcategory of sociotropic attitudes, under the umbrella of ‘symbolic’ threats to society.

We thus adopt a similar logic to that of Hainmueller and Hopkins (Citation2014) to define ethnolinguistic attitudes, i.e. attitudes regarding various social and political aspects of the ethnolinguistic divide. Egotropic ethnolinguistic attitudes thus concern personal consequences related to ethnolinguistic policies, such as personal opportunities or disadvantages. Sociotropic attitudes, in turn, are directed at the impact of language policy on society as a whole, whether from an economic point of view or in relation to a perceived ‘symbolic threat’ towards national identity.

Ethnic Prejudice

Unlike Hainmueller and Hopkins (Citation2014), we do not consider ethnic prejudice to be a subcategory of sociotropic attitudes. Rather, following Bustikova (Citation2014), we distinguish between discontent about accommodation of minority interests and ethnic prejudice towards the minority, which we consider to be a dimension in its own right.

According to Allport (Citation1954, p. 9), ethnic prejudice is ‘an antipathy based upon a faulty and inflexible generalization’. In other words, ethnic prejudice is a negative attitude or feeling towards individuals or groups based solely on their ethnic background. It represents an overgeneralized belief, a stereotype, about the characteristics of a group without consideration for individual differences. A later criticism of Allport’s definition is that it focused too much on overt prejudice and largely ignored more subtle forms of prejudice, e.g. the paternalism of some forms of gender prejudice (Eagly & Diekman, Citation2008; Rudman, Citation2008). Subtle forms of prejudice are likely to be relevant to our study considering that they are directed towards a minority group that is highly integrated in Finnish society (high levels of bilingualism, high share of inter-ethnic marriages). Hence, prejudice is more likely to be a result of inconsiderate assumptions than overt antipathy.

3 Finland and the Swedish People’s Party as an Ethnic Party

Historical Roots of the Language Divide and Party System

The territory of modern-day Finland was an integral part of the Swedish realm before 1809, when it was conquered by the Russian empire and subsequently granted status as an autonomous Grand Duchy. The population in this new territorial unit thus consisted of both Swedish speakers and Finnish speakers, not counting the Sámi in the north of Finland, and other minorities. While Swedish remained the official language of the Grand Duchy, an active effort was made to build a national identity around the Finnish language, spoken by around 85% of the population, and resulted in Finnish gaining equal status to Swedish during this period (McRae, Citation1999; Saaristo, Citation2020).

In the decades leading up to the establishment of the modern Finnish parties, and the first general election with universal and equal suffrage in 1907, the language issue was a source of political conflict. The Finnish national movement, which included prominent Swedish speakers, argued that Swedish should be abandoned to create a united national identity. However, a Swedish nationalist movement formed alongside the Finnish one, arguing against the abandonment of Swedish and instead seeking to build a national identity that included both languages and maintain Swedish as a national language (Saaristo, Citation2020). The SFP was formed in 1906 as part of the Swedish nationalist movement and is still today primarily considered as representing the interests of the Swedish-speaking minority. Since this party is of specific interest in our study, we will discuss it more closely in the following section.

When Finland gained independence from the Russian empire in 1917, both Finnish and Swedish were granted equal status in the constitution as national languages. What was known as the ‘language issue’, i.e. the question of whether Swedish should remain equal to the Finnish language nonetheless continued to be a heated political issue until the mid-twentieth century. Since then, the political importance of the linguistic divide has decreased over time and has mainly concerned the question of teaching Swedish as a mandatory subject in basic education and the role of language policy during various administrative reforms. Today, Swedish speakers constitute around 5% of the Finnish population (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2023).

The language divide was only one of several relevant cleavages that characterized the Finnish party system since the first parliamentary election in 1907 and shaped the party system of today. The Left–Right and urban–rural cleavages manifested in three opposing poles that dominated the political arena throughout the twentieth century. Each pole was represented by one major party: labour-urban by the Social Democratic Party (SDP), capital-urban by the National Coalition (KOK) and the rural periphery by the Centre Party (KESK) (Rokkan, Citation1987, pp. 81–95; Sundberg, Citation1999). Currently, nine parties are represented in the Finnish parliament (von Schoultz & Strandberg, Citation2024), although the Movement Now party holds only one seat and is excluded from this study due to its small size. Instead, we focus on the traditional eight parties, which in addition to the ones already mentioned are the Left Alliance (VAS), the Christian Democrats (KD), the Greens (VIHR), the right-wing populist Finns Party (PS) and, lastly, Swedish People’s Party (SFP). Even though today, as many as four relevant political cleavages can be identified in Finnish politics (Westinen Citation2015), the party system has developed towards two dominating conflict dimensions: Left–Right and Liberal–Conservative, or GAL-TAN.

The Swedish People’s Party as an Ethnic Party

In this study, we classify the SFP as an ethnic party based on the linguistic aspect of ethnicity. According to Chandra (Citation2004, p. 3), an ethnic party is a party that ‘overtly represents itself as champion of the cause of one particular ethnic category’ (race, language, religion, etc.) and that ‘makes such a representation central to its strategy of mobilizing voters’. Others (e.g. Horowitz, Citation2001) focus more on the distribution of support for the party. According to this definition, an ethnic party is defined as being primarily supported by voters of a particular ethnic category.

The SFP fits both these definitions. The party is an outspoken defender of the Swedish language in Finland and has been described as a moderate protectionist ethnic party (de Winter, Citation1998; Ishiyama & Breuning, Citation2011). The SFP is also very successful in mobilizing the Swedish-speaking vote in Finland, gaining stable support in Finnish parliamentary elections which has resulted in between 4.3% and 4.9% of the votes in the last five parliamentary elections (2003–2019). Survey research suggests that approximately 70% of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland vote for the SFP (Grönlund, Citation2011; Sundberg et al., Citation2005). While the party often wants to position itself as a socially and economically liberal option, the common denominator for SFP voters is the Swedish language, not a sharply defined ideological outlook (Djupsund & Carlsson, Citation2005).

The Swedish People’s Party’s Relations to Other Parties

The SFP, like any other ethnic minority party, is oriented towards the protection of minority interests. However, in Western Europe, it is quite a unique party. Few ethnic parties have participated in government during the post-war period, and only the SFP in Finland has been able to participate for any considerable period of time (Karvonen, Citation2014; Lane & Ersson, Citation1999). The SFP’s potential to assist in the formation of national governments is an explanation for their attractiveness as a coalition partner. Since they derive most of their political power from being a protector of minority interests, they can be rather flexible with their other political priorities.

However, the SFP’s role as an outspoken protector of Swedish language rights, together with lengthy stints in government, is also a source of some annoyance among the Finnish-speaking public. Supporters of the Finns Party feel the most negative about issues related to the Swedish language in Finland. Lundell (Citation2020) finds that 55% of Finnish-speaking Finns agreed with the statement that the SFP has more power than it ought to have in Finnish politics considering its size, while 82% of those sympathizing with the Finns Party agreed with the same statement. The negative attitudes toward the Swedish language in Finland among Finns Party voters extend beyond partisan opinions about the SFP. While two-thirds of Finnish-speaking Finns agree with the statement that the Swedish language is a central aspect of Finnish society, only one-third of those sympathizing with the Finns Party have this view (Himmelroos & Strandberg, Citation2020; Lundell, Citation2020). Furthermore, members of parliament that represent the Finns Party generally have even stronger negative views of the Swedish language in Finland than their voters (von Schoultz, Citation2020), and parliamentary debates around the Swedish language in Finland tend to be dominated by the Finns Party and the SFP, with little input from other parties (Fagerholm, Citation2020). Given the pronounced role of the Finns Party as an outspoken critic of the Swedish language in Finland and of the SFP, we formulate a second research question: do supporters of the Finns Party differ from supporters of other parties in how their ethnolinguistic attitudes are associated with affect towards the SFP?

4 Data and Variables

The data for this study was collected in two different waves in 2021 and 2022 within the framework of an online panel. These years are situated between two parliamentary elections (held in 2019 and 2023), a period in which the SFP was a member of the governing coalition. The timing of the collection means that in our data, the potential effects of election campaigns or changes in government participation should be minimal. The data collected in the first wave in 2021 contains 1656 responses and was designed to measure media use and ideological bubbles. It contains questions about ideological positions and party attitudes. From this survey, we found the items that allow us to measure affect towards parties, as well as controls for vote choice and ideological positions. The data from this first survey was combined with responses from a second wave in 2022, which was part of a project to measure attitudes towards the Swedish language in Finland and contains 2832 responses. The second survey thus contained the items that form the foundation of our main independent variables. We also use this second round of data collection for demographic control variables, as it is the most recent of the two.

The combined dataset contains answers from 1269 respondents who have answered both surveys, providing us with an initial sample of Finnish voters through which we can examine the link between language attitudes and affective polarization. In our analyses of this data, we use post-stratification rake-weights based on gender, age, region and education. The sample is presented in closer detail in Appendix A.

Variables

Affect towards the Swedish People’s Party

Originally, Iyengar et al. (Citation2012) operationalized affective polarization as the gap between how positively the inparty is evaluated and how negatively the outparty is evaluated. Following Mason (Citation2015), this definition of affective polarization can be described as partisan bias. At the individual level, it manifests as a positive emotional attachment towards the individual’s preferred party (the inparty), and negative sentiment towards a specific outparty. While the mechanisms we propose may influence feelings towards all parties to some degree, our theoretical framework is geared towards understanding how they drive affect towards ethnic parties in particular. For this reason, a classical approach to affective polarization as the difference in inparty and outparty affect is less appropriate, as it obscures whether findings are the results of changing inparty or outparty affect. Instead, we focus exclusively on evaluations of the ethnic party, i.e. how the SFP is evaluated in the role of an outparty.

To measure affect against the SFP we employ the commonly used like–dislike scale, where respondents are asked to rate each party on an 11-point scale in response to the question: ‘What do you think about the following political parties on a scale of 0–10, where 0 means “strongly dislike” and 10 means “strongly like”?’ This type of scale is similar to the 101-point temperature scale used by Iyengar et al. (Citation2012) to measure warm and cold feelings towards parties. It is also important to note that this approach measures attitudes towards the party as a broad object and does not necessarily reflect attitudes or tendencies in behaviour towards regular supporters of the party (Druckman & Levendusky, Citation2019). This focus on party-level attitudes is in line with the objective of this study to examine whether ethnic prejudice towards individuals translates into negative attitudes towards the related ethnic party (for discussion and alternative approaches, see Druckman & Levendusky, Citation2019; Gidron et al., Citation2022; Kekkonen et al., Citation2022).

This results in an outparty evaluation of the SFP ranging from 0 to 10 for each respondent. Out of the 1269 respondents, 77 did not evaluate the SFP on the like–dislike scale and were thus removed from the sample at this stage. Similarly, the 29 respondents who voted for the SFP were excluded, since we are not concerned with inparty affect among supporters of the ethnic party. Moreover, we excluded observations with missing data in control variables, resulting in a reduced sample of 1058 respondents that we use to analyse affect towards the SFP. This reduced sample is described in the supplementary material (see Appendices A and B) and does not differ in any significant aspect from the initial sample. As shown in Appendix B, the like–dislike evaluations of the SFP follow an approximately normal distribution among voters of most parties; in some cases it is slightly skewed towards either the like or the dislike end of the scale. The distribution among the Finns Party voters stands out from the voters for other parties as predominantly negative towards the SFP, with ‘0’, i.e. strongest possible dislike, being the most predominant score.

Sociotropic attitudes towards the Swedish language in Finland

We measure the first independent variable, sociotropic attitudes, by tapping respondents’ views on the role of the Swedish language in Finland at a general level. The equal constitutional status of Finnish and Swedish as national languages is an important symbolic question, and strong opinions can be indicative of a perceived ‘symbolic threat’ to society from the opposing perspective. It is important to note that the topic of national bilingualism is not reflective of any ongoing constitutional struggle between parties with opposing agendas. This is evidenced, for example, by the SFP’s long-term participation in various governing coalitions (Karvonen, Citation2014, p. 91), which would not be possible if a coalition partner opposed the constitutional arrangement. The possible exception to this general rule is the Finns Party, which expresses opposition towards national bilingualism in various political programmes (Perussuomalaiset, Citation2015; Citation2022). However, these challenges are mostly indirect, such as the previously discussed demand that Swedish should not be a mandatory subject in basic education, which received minimal support from members of other parties (Fagerholm, Citation2020). Moreover, as of 2023, the SFP is a member of a government coalition with the Finns Party, suggesting that even for the Finns Party, constitutional change is not at the top of the agenda. Support for and opposition to the idea of two equal national languages nonetheless varies on the individual level regardless of party preference among Finnish voters, and thus constitutes a suitable candidate for a sociotropic attitude.

We measure this attitude by combining two items, one from each of the two surveys used to create the sample. The items are formulated as statements to which the respondent can agree or disagree on a 11-point scale for the first question and a 5-point scale for the second question:

In the following, some propositions relating to the future direction of Finland are listed. What is your opinion on these propositions? A Finland that has two strong national languages: Finnish and Swedish.

In my opinion, the Swedish language is a central aspect of Finnish society.

We rescale the items and calculate a mean value, which results in an attitude measure with a range of 0–1, where 1 is the most positive attitude in favour of the Swedish language in Finnish society.

Egotropic attitude towards the Swedish language in Finland

The second independent variable, egotropic attitudes, is measured through perceptions of the usefulness of the Swedish language. This hence taps into attitudes at the level of personal interest. Two items are used:

Knowing Swedish is becoming less and less important. (reversed)

I would like to know the Swedish language better.

The respondent can agree or disagree to the statements on a 5-point scale. We combine the items and rescale the response to 0–1, where 1 is the most positive attitude towards the usefulness of the Swedish language.

Ethnic prejudice against Swedish-speaking Finns

The third independent variable taps directly into attitudes towards the Swedish-speaking minority and measures the level of prejudice with two items:

In my opinion, Swedish speakers want to keep to themselves and distance themselves from the Finnish-speaking population.

In my opinion, Swedish speakers are arrogant.

Both questions play on long-standing stereotypes of Swedish speakers that are specific to the cultural context of Finland. Historically, a substantial portion of the upper classes in Finland spoke Swedish. The respondent can agree or disagree with the statements on a 5-point scale. We reverse and rescale the attitude measure to 0–1, where 1 is the most positive (unprejudiced) attitude towards Swedish speakers.

Control variables

Our primary control variables are for ideological position on the two scales; Left–Right and Liberal–Conservative. Both dimensions have been shown to have a strong effect on general affective polarization levels in Finland (Kawecki, Citation2022a). Self-reported ideological position is centred around 0 and rescaled so that −0.5 equals the strongest Left or Liberal position, while 0.5 equals the strongest Right or Conservative position. By using squared terms for both ideological dimensions in our regression models, we take non-linear effects into account.

As discussed in the previous section, the question of whether it should be mandatory to study Swedish in Finnish schools has been strongly politicized by some parties, especially the Finns Party. The question thus has the potential to drive affective polarization towards the SFP. However, it does not easily fit into our theoretical framework. First, it is difficult to gauge whether attitudes to this question stem from prejudice or from sociotropic or egotropic attitudes towards the Swedish language. Second, attitudes to this question do not necessarily represent ethnolinguistic concerns. Rather, they could be derived from a principled stance about freedom of choice, regardless of whether one has positive or negative attitudes towards the language. We resolve this by controlling for the effect of this variable, taking its potential impact into account while remaining within the chosen theoretical framework.

Furthermore, we control for basic sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, education level and residential area. We also take into account the possibility that contact with the Swedish-speaking minority might affect attitudes (Himmelroos, Citation2020) and thus create a dummy variable for the respondent’s municipality to indicate whether it is monolingually Finnish or has an official status as either a bilingual or monolingual Swedish municipality. Similarly, we believe that SFP representation in the voter’s home municipality might influence attitudes towards the party and therefore control for whether the party is not represented at all, or has a small (<10%), medium (11–30%) or large (>30%) share of local seats. Lastly, we control for vote choice, as we believe that it might serve as a proxy for policy disagreement and partisan conflict that is otherwise unaccounted for and might contribute to biased attitudes towards the SFP.

5 Analysis and Results

In the following, we will present analyses that allow us to respond to our two research questions. The first and main research question is: ‘to what extent do egotropic attitudes, sociotropic attitudes and ethnic prejudice among supporters of non-ethnic parties have an impact on affect towards an ethnic minority party?’ Furthermore, we take a specific interest in the role of the radical right-wing populist Finns Party as an outspoken critic of the Swedish language in Finland, and therefore ask our second research question: ‘Do supporters of the Finns Party differ from supporters of other parties in how their ethnolinguistic attitudes impact on affect towards the Swedish People’s Party?’

Our analysis contains three steps. Initially, we build a statistical model and examine to what extent our independent variables are associated with changes in affect towards the SFP. Next, we test the same model with each of the other parties as the target of affective evaluations. This will reveal whether ethnolinguistic attitudes have a particular impact on affect towards the SFP in accordance with our expectations, or whether they are similarly associated with affect towards other parties. Lastly, we interact the main variables of our model with a dummy variable of whether the respondent voted for the Finns Party or not. This will reveal whether the Finns Party supporters differ from supporters of other parties in how their ethnolinguistic attitudes impact their evaluations of the SFP.

We initiate the analysis by regressing affect towards the SFP on each of the independent variables, both one by one and in combination. The correlations between these variables are moderate, ranging from R = 0.4–0.6, providing sufficient variation to separate the effects of each variable. shows that each independent variable is positively correlated with affect towards the SFP. The more positive the attitude, the more positive the evaluation of the SFP, which is an expected result. When all three variables are included in the model, ethnic prejudice has a substantially smaller effect, and the effect for egotropic attitudes becomes insignificant. Overall, this indicates that sociotropic attitudes are the main predictor of affect towards the SFP.

Table 1. Effects of the independent variables on affect towards the Swedish People’s Party (SFP)

In , we add control variables in multiple steps. Adding controls for ideological position lessens the effect of ethnic prejudice and sociotropic attitudes. Adding further sociodemographic controls, controls for the contact hypothesis (proximity to Swedish language/the SFP), and lastly controls for vote choice, only changes effects to a small degree. The results thus suggest that sociotropic attitudes remain the most important aspect of how ethnolinguistic attitudes translate into affective evaluations of the SFP, even after control for other factors. The effect sizes of egotropic attitudes and ethnic prejudice are markedly smaller, and only the effect of ethnic prejudice passes the significance threshold of p < 0.05.

Table 2. Stepwise addition of control variables

Next, we test our assumption that the ethnic party is especially susceptible to ethnolinguistically motivated affect. In , we use the full model from , but instead of affect towards the SFP, we use corresponding like–dislike scores for the seven other parties as dependent variables. As outlined in Section 3, these parties represent the classical cleavages in European politics as well as the major post-materialist party families. Here, they nonetheless serve mainly as points of comparison, and we do not discuss their specific characteristics further. If our assumption is correct, the associations between the ethnolinguistic variables and affective evaluations should be markedly stronger than it is for other parties when SFP is the target. However, it is also possible that the association is not markedly stronger, which could mean that our assumption is wrong, either because other non-ethnic parties are similarly perceived to be associated with accommodation of minority interests, or because the variables tap into broader attitudinal dimensions of which ethnolinguistic attitudes are only one manifestation.

Table 3. Effect of independent variables on party affect towards each of the parliamentary parties

The effect sizes in demonstrate that affect towards SFP stands out as especially sensitive to sociotropic attitudes. The variable has a significant effect only on evaluations of one other party, the Christian Democrats, which can be partly explained by the fact that this party is strong in some of the regions where many Swedish speakers reside. Of the other variables, neither ethnic prejudice nor egotropic attitudes stand out as having a uniquely large impact on affect towards the SFP. In several cases, the impact is stronger for affect towards other parties. Specifically, the egotropic belief that Swedish is useful is associated with positive evaluations of the Greens. Similarly, having an unbiased attitude (i.e. low ethnic prejudice) towards Swedish speakers is equally strongly associated with positive evaluations of the SFP, the Greens and the Left Alliance.

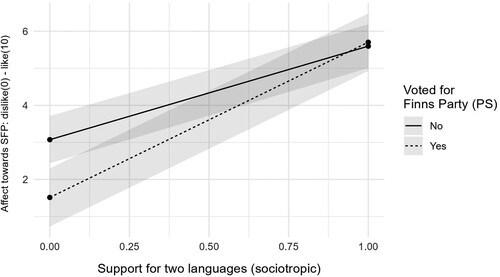

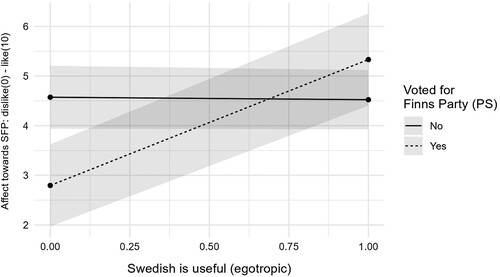

Lastly, we examine whether Finns Party voters differ from other voters regarding the type of attitudes that impact affective evaluations of the SFP. We replace the vote choice variable with a dummy variable for whether the respondent voted for the Finns Party or not. We then run our model three times and interact the dummy variable with each of our main variables of interest.Footnote1 shows that Finns Party voters indeed differ from voters for the other parties. We find statistically significant interaction effects between voting for the Finns Party and both supporting two languages (sociotropic attitude) and finding Swedish useful (egotropic attitude). We illustrate these effects in and . In the case of sociotropic attitudes, demonstrates that the main divergence is at the bottom end of the attitude scale, i.e. the Finns Party voters who are most negative towards national bilingualism evaluate the SFP more negatively than voters for other parties. However, this divergence is not present at the positive end of the attitude scale. In sum, the interaction effect mainly affects the downside, making supporters of the Finns Party potentially more negative to the SFP while the direction of the association is still the same for both groups.

Figure 1. Interaction plot for voting for the Finns Party (PS) and sociotropic attitude towards the Swedish People’s Party (SFP)

Figure 2. Interaction plot for voting for the Finns Party (PS) and egotropic attitude towards the Swedish People’s Party (SFP)

Table 4. Interaction between main variables and voting for the Finns Party (PS)

Turning to the egotropic dimension in , we find a somewhat different pattern emerging. Here, the perceived usefulness of the Swedish language does not have a significant effect on evaluations of the SFP among mainstream party supporters, but it has a comparatively strong effect among Finns Party voters. Similarly to the sociotropic attitude, this effect results in the largest differences at the negative end of the attitude scale.

In short, we find that sociotropic as well as egotropic attitudes influence evaluations of the SFP much more strongly among Finns Party voters among. However, ethnic prejudice does not impact on evaluations of the SFP among Finns Party voters any more or less than among supporters of other parties.

6 Concluding Discussion

This study set out to explore the link between affective polarization and the presence of ethnic parties. Specifically, we focused on mechanisms at the individual level that are associated with outparty affect towards ethnic parties and hypothesized that this can result from either spillover from prejudice against the represented ethnic group or from discontent with policies to accommodate ethnic minority interests. Such discontent, in turn, can be either sociotropic in nature, that is, derived from broader societal concerns, or egotropic, that is, derived from concerns about personal disadvantages. We tested these relationships through a case study of Finland, where the ethnic minority party is the Swedish People’s Party (SFP). We expected that anti-Swedish attitudes would be associated with negative affect towards the SFP. Furthermore, we believed that these associations would be uniquely strong in comparison to any potential associations with affect towards other parties, thereby demonstrating that the ethnic party is particularly prone to become the object of ethnically motivated evaluations.

Out of our three variables, we found that sociotropic attitudes had the strongest association with affect towards the SFP. The weaker the support among individuals for the idea of a bilingual Finland, the more negative their attitude to the SFP. Only in the case of one other party did we find a significant association between sociotropic attitudes and affect, namely the Christian Democrats. However, this association was substantially weaker, which confirms that the SFP is uniquely associated with this question in the minds of supporters of other parties. This finding thus suggests that ethnic parties are indeed especially susceptible to sociotropically motivated affective evaluations.

We did not find any relationship between egotropic attitudes, i.e. perceived usefulness of the Swedish language, and affect towards the SFP among the population in general, with the exception of Finns Party voters. Instead, we unexpectedly found a statistically significant association with outparty affect toward the Greens, indicating either that individuals do not specifically connect the perceived usefulness of the Swedish language with the SFP, or that our operationalization of egotropic attitudes might have tapped into other underlying dimensions, such as a general trait of cultural or linguistic openness particularly associated with culturally progressive parties. These results are therefore difficult to interpret, but nonetheless indicate that egotropic attitudes in general are not important as predictors of affect towards ethnic parties.

Supporters of the Finns Party are an exception to the results discussed thus far. Radical right-wing populist parties often position themselves in opposition to accommodating the interests of ethnic minorities, and the Finns Party in Finland is no exception. We expected that this group may differ from supporters of other parties in their motivations for affect towards the SFP, and this was indeed the case. Sociotropic concerns played a similar role among voters for the Finns Party and other parties, i.e. the overall correlation was positive, but as the attitude towards national bilingualism became more negative, Finns Party supporters displayed even more negative affect towards the SFP than supporters of other parties. Furthermore, egotropic concerns played a major role among Finns Party supporters, as opposed to supporters of other parties; the more the Finns Party supporters perceived the Swedish language to be useful, the more positive they became towards the SFP. This suggests a utilitarian perspective that contrasts with the broader societal perspective that appears to be inherent in how voters in general relate to the SFP.

Lastly, we found an association, albeit minor in comparison to sociotropic attitudes, between prejudice against Swedish speakers and negative affect towards the SFP. This association was, however, not uniquely strong for affective evaluations against the SFP. The same variable also predicted affective evaluations of the Greens and the Left Alliance, and the results are therefore inconclusive. It is possible that the difficulty of gauging this type of attitude with direct questions has influenced our results, or that prejudice against Swedish speakers is merely a manifestation of a more generally ‘prejudiced’ mindset that impacts on attitudes towards multiple parties, particularly towards parties at the most culturally progressive end of the political spectrum.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that negative affect against the SFP is mainly associated with disagreement about minority accommodation. Among the general population, this disagreement is situated at the sociotropic level, but in the case of the Finns Party voters, the egotropic perspective is also strongly present.

Considering that our findings are based on data from a single country, we are nonetheless limited in our ability to conclude to what extent our results are generalizable to other countries with ethnic parties. Hence, it would be important for future research to build on these findings using data that is better equipped for causal inference or explore attitudes toward ethnic parties in other contexts. Despite these limitations, our study and its findings about the drivers of affective evaluations of ethnic outparties makes an important contribution to the current research on affective polarization, which has mainly focused on traditional ideological stances and partisan social identities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (382.4 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset was collected through the Kansalaismielipide-Meborgaropinion online panel maintained by Åbo Akademi University. Data is available from the Finnish Social Science Data Archive FSD as part of the FIRIPO data series.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2024.2364314.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Kawecki

Daniel Kawecki is a PhD researcher at the University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences, and employed by the Society for Swedish Literature in Finland. His research is focused on affective political polarization and voter behaviour.

Staffan Himmelroos

Staffan Himmelroos is University Lecturer at the Swedish School of Social Science, University of Helsinki, Finland. His research interests include democratic innovations and political behaviour among minority groups and non-resident citizens.

Kim Strandberg

Kim Strandberg is Professor of Political Science and Political Communication at Åbo Akademi University, Finland. His research concerns public opinion, polarization, deliberation and online campaigning. He has published in journals including the International Political Science Review, New Media and Society, Party Politics, and Political Behaviour.

Åsa von Schoultz

Åsa von Schoultz is Professor of Political Science at the University of Helsinki, Finland, and Director of the Finnish National Election Study. She is also Chair of newly established Consortium for National Election Studies (CNES). Her research revolves around political behaviour, with a specific focus on electoral competition within parties.

Notes

1 We also ran a single model with all possible interactions between the main variables and the dummy variables, but due to the resulting complexity this approach became unfeasible, so we opted for a simplified approach.

References

- Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Beesley, C., & Bastiaens, I. (2022). Globalization and intention to vote: the interactive role of personal welfare and societal context. Review of International Political Economy, 29(2), 646–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1842231

- Bougher, L. D. (2017). The correlates of discord: Identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America. Political Behavior, 39(3), 731–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9377-1

- Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2024). Cross-country trends in affective polarization. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 106(2), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01160

- Bradley, M., & Chauchard, S. (2022). The ethnic origins of affective polarization : Statistical evidence from cross-national data. Frontiers in Political Science, 4(July), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.920615

- Bustikova, L. (2014). Revenge of the radical right. Comparative Political Studies, 47(12), 1738–1765. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013516069

- Chandra, K. (2004). Why ethnic parties succeed: patronage and ethnic headcounts in India. Cambridge University Press.

- Chandra, K. (2006). What is ethnic identity and does it matter? Annual Review of Political Science, 9(1), 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170715

- de Winter, L. (1998). Conclusion: A comparative analysis of the electoral office and policy success of ethnoregionalist parties. In L. de Winter, & H. Türsan (Eds.), Regionalist parties in Western Europe (pp. 204–247). Routledge.

- Djupsund, G., & Carlsson, T. (2005). Högt i tak och brett mellan väggarna? In Å Bengtsson, & K. Grönlund (Eds.), Den finlandssvenska väljaren (pp. 57–88). Samforsk.

- Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003

- Eagly, A. H., & Diekman, A. D. (2008). What is the problem? Prejudice as an attitude-in-context. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 19–35). Blackwell Publishing.

- Fagerholm, A. (2020). Belastning eller tillgång? En kartläggning av riksdagsdebatten kring medborgarinitiativet om frivillig skolsvenska. In S. Himmelroos, & K. Strandberg (Eds.), Ur Majoritetens Perspektiv. Opinionen Om Det Svenska i Finland (pp. 166–191). SLS.

- Gidron, N., Sheffer, L., & Mor, G. (2022). Validating the feeling thermometer as a measure of partisan affect in multi-party systems. Electoral Studies, 80, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102542

- Grönlund, K. (2011). Politiskt beteende i Svenskfinland och på Åland. In K. Grönlund (Ed.), Språk och politisk mobilisering. Finlandssvenskar i publikdemokrati (pp. 63--86). SLS.

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

- Hansen, K. M., & Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2017). How campaigns polarize the electorate: Political polarization as an effect of the minimal effect theory within a multi-party system. Party Politics, 23(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815593453

- Hernández, E., Anduiza, E., & Rico, G. (2021). Affective polarization and the saliency of elections. Electoral Studies, 69(June), 102203–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102203

- Himmelroos, S., & Strandberg, K. (2020). Ur majoritetens perspektiv. Opinionen om det svenska i Finland. SLS.

- Himmelroos, S. (2020). Attityder till det svenska – Kontakthypotesen som förklaringsmodell. In S. Himmelroos, & K. Strandberg (Eds.), Ur Majoritetens Perspektiv. Opinionen Om Det Svenska i Finland (pp. 101–118). SLS.

- Horowitz, D. (2001). Ethnic groups in conflict. University of California Press.

- Huddy, L., Bankert, A., & Davies, C. (2018). Expressive versus instrumental partisanship in multiparty European systems. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 173–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12482

- Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

- Ishiyama, J., & Breuning, M. (2011). What’s in a name? Ethnic party identity and democratic development in post-communist politics. Party Politics, 17(2), 223–241.

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology : A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

- Iyengar, S., & Krupenkin, M. (2018). The strengthening of partisan affect. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12487

- Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152

- Karvonen, L. (2014). Parties, governments and voters in Finland. Politics under fundamental societal transformation. ECPR Press.

- Kawecki, D. (2022a). End of consensus? Ideology, partisan identity and affective polarization in Finland 2003–2019. Scandinavian Political Studies, 45(4), 478–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12238

- Kawecki, D. (2022b). Poliitinen polarisaatio Suomessa ja Ruotsissa. In A. Saarinen (Ed.), Vastakkainasettelujen aika. Poliitinen polarisaatio ja Suomi (pp. 119–125). Gaudeamus.

- Kekkonen, A., Suuronen, A., Kawecki, D., & Strandberg, K. (2022). Puzzles in a affective polarization research: Party attitudes, partisan social distance, and multiple party identification. Frontiers in Political Science, 4, 920567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.920567

- Kekkonen, A., & Ylä-Anttila, T. (2021). Affective blocs: Understanding affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 72, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102367

- Lane, J.-E., & Ersson, S. (1999). Politics and society in Western Europe, 4th ed. Sage Publications.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Paldam, M. (2000). Economic voting: An introduction. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(99)00042-6

- Lundell, K. (2020). Partiidentifikation och partiideologi: skillnader i attityder till svenskan. In S. Himmelroos, & K. Strandberg (Eds.), Ur Majoritetens Perspektiv. Opinionen Om Det Svenska i Finland (pp. 47–65). SLS.

- Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089

- Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001

- McRae, K. D. (1999). Conflict and compromise in multilingual societies: Finland. Finnish Academy of Science and Letters.

- Official Statistics of Finland. (2023). Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Population structure. Statistics Finland. [Referenced: 15.2.2024]. https://stat.fi/en/statistics/vaerak

- Perussuomalaiset. (2015). Language policy of The Finns Party in The Finnish Parliament Elections of 2015. https://www.perussuomalaiset.fi/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ps_language_policy.pdf (Accessed: 6.3.2024)

- Perussuomalaiset. (2022). Suomalaisuusohjelma 2022. https://www.perussuomalaiset.fi/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ps_language_policy.pdf (Accessed: 6.3.2024)

- Reiljan, A. (2020). “Fear and loathing across party lines” (also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 376–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12351

- Rogowski, J. C., & Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How ideology fuels affective polarization. Political Behavior, 38(2), 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7

- Rokkan, S. (1987). Stat, Nasjon, Klasse: essays i politisk sosiologi [State, nation, class: essays in political sociology]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Rump, M., & Zwiener-Collins, N. (2021). What determines political trust during the COVID-19 crisis? The role of sociotropic and egotropic crisis impact. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(S1), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924733

- Steenvoorden, E. H., & Wright, M. (2019). Political Shades of ‘we’: sociotropic uncertainty and multiple political identification in Europe. European Societies, 21(1), 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1552980

- Rudman, L. A. (2008). Rejection of women? Beyond prejudice as antipathy. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 106–120). Blackwell Publishing.

- Saaristo, M. (2020). The construction, consolidation and transformation of the ethnic, collective identity Finland-Swede in the context of Swedish and Bilingual Voluntary Associations. [Doctoral dissertation] University of Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-3457-8

- Sundberg, J., Wilhelmsson, N., & Bengtsson, Å. (2005). Svenskt och finskt väljarbeteende. In Å. Bengtsson, & K. Grönlund (Eds.), Den finlandssvenska väljaren (pp. 23–56). Samforsk.

- Sundberg, J. (1999). The enduring Scandinavian party system. Scandinavian Political Studies, 22(3), 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.00014

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austinand, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations (pp. 33–79). Brooks-Cole.

- von Schoultz, Å. (2020). Åsiktsöverensstämmelse i språkfrågan – Representerar partierna väljarnas åsikter? In S. Himmelroos, & K. Strandberg (Eds.), Ur Majoritetens Perspektiv. Opinionen Om Det Svenska i Finland (pp. 150–165). SLS.

- von Schoultz, Å., & Strandberg, K. (2024). Political behaviour in contemporary Finland. Studies of voting and campaigning in a candidate oriented political system. Routledge.

- Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 69, 102199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

- Westinen, J. (2015). Cleavages in contemporary Finland. A study on party-voter ties. [Åbo Akademi University]. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-765-801-0