One of the perks of being a journal editor are the occasional invitations to travel to interesting locations to meet with informed and insightful colleagues to discuss current trends in our academic discipline. One such event, recently hosted by Copenhagen Business School, provided an opportunity for scholars from a range of disciplinary (and national) backgrounds to share their perspectives on the way in which history is being integrated with other business school disciplines – most notably organization studies. This is clearly a topic of particular interest for our journal, positioned as it is at the intersection on management history and organizational theory. Contributors to Management and Organizational History (MOH) have, of course, helped to lead the way in promoting a ‘historical turn’ in organization studies (Clark and Rowlinson Citation2004; Booth and Rowlinson Citation2006; Mills et al. Citation2016), and the last decade has witnessed an increasingly productive dialogue between researchers working in these two disciplinary areas. This is reflected in the publication of historically themed special issues of mainstream management (Godfrey et al. Citation2016; Wadhwani et al. Citation2018; Argyres et al. Citation2017; Wadhwani et al. Citation2016), as well as the variety of papers that have sought to map out the different ways in which history and management theory are being combined (Kipping and Usdiken Citation2014; Rowlinson, Hassard, and Decker Citation2014; Maclean, Harvey, and Clegg Citation2016; Zundel, Holt, and Popp Citation2016; Decker Citation2016; Foster et al. Citation2017).

In the light of this emerging literature, and the discussion it has generated at various recent business history workshops and conferences, this would seem to be an opportune moment to proffer some editorial comments on the way in which historical and theoretical approaches can be accommodated within the pages of MOH.

As Decker (Citation2016) points out, a distinct trend in the literature on this topic has been to move beyond ‘supplementarist’ approaches, which tend to place history in a subordinate role – essentially supplying data in order to test or refine theory. Rather, emphasis has tilted toward what Üsdiken and Kieser (Citation2004) referred to as ‘integrationist’ approaches, in which history and theory meet on equal terms, each informing and supporting the other. If the goal of mutually beneficial integration is widely shared, there is rather less consensus about what this actually looks like in practice.

Kipping and Üsdiken (Citation2014) differentiate between what they call ‘history-in-theory’ (in which a temporal dimension is built into theoretical modeling) and ‘historical cognizance’ (in which theorizing takes account not just of time, but of historical context.) Maclean, Harvey, and Clegg (Citation2016), in a similar vein, call for integrative studies that meet the threshold of ‘dual integrity’ by achieving legitimacy in the eyes of both theorists and historians. But is such a standard of ‘dual integrity’ realistically achievable? Maclean et al. highlight some important differences in the way in which historians and management theorists typically work (and in the type of work they value). Rowlinson, Hassard, and Decker (Citation2014) clarify such differences very effectively, by pointing to three fundamental ‘dualisms’ between historical and theoretical approaches. Such differences have led them, and others (e.g. Coraiola, Foster, and Suddaby Citation2015; Decker, Kipping, and Wadhwani Citation2015), to advocate ‘pluralist’ rather than ‘unitary’ models of integrating history into organizational studies.

Pluralism, I’m happy to report, is a principle we heartily endorse at MOH. The journal has always been interested in work both by historians with an interest in organizational change, as well as by organizational theorists with an interest in different historical contexts (Rowlinson and Hassard Citation2013). This means that some articles draw their originality from their archival source material and narrative construction, while others claim novelty from their approach to theory development and refinement. As with any peer-reviewed journal, what we look for in all cases is research that is demonstrably rigorous in its standards of scholarship, and relevant to wider audiences. The key concern of this editorial, therefore, is to identify the different ways in which scholarly validity and academic relevance can be achieved, and to use these dimensions as a means of mapping out the different types of research papers that we are most keen to attract.

Representativeness and particularity as sources of scholarly validity

One of the criticisms most often faced by historians when trying to address their work to management scholars relates to the question of generalisability. A carefully researched historical case study might make fascinating reading, but the question that often follows is ‘so what?’ Such cases can quickly be reduced to the status of anecdotes – interesting vignettes, perhaps, but essentially single data points from which it is unsafe to draw wider conclusions. Historians, for their part, are typically wary of any attempts to construct (and impose) universal theories of behavior that are insensitive to the particularities of different historical contexts. If theoretically minded social scientists are unimpressed by mere anecdotes, historians are equally skeptical of anachronistic applications of contemporary theories to past individuals or societies (Lipartito Citation2014). The way researchers in these disciplines think about what constitutes valid (and potentially generalizable) scholarship is an important area of difference. On the one side, we can identify approaches which prioritize the selection and analysis of evidence that is deemed to be ‘representative’. Here, the peculiarities of specific historical contexts constitute a potential problem – a source of ‘noise’ that needs to be controlled for when constructing a representative sample. Only by effectively doing this through careful experimental design can research findings be considered robust. On the other side, we find researchers that prefer to emphasize contextual peculiarities, focusing on periods or cases that are atypical and decidedly unrepresentative. Such studies often accentuate the messy realities that complicate attempts to rationalize the actions or decisions of actual historical actors in theoretical terms. In this latter case, generalizability is achieved not by controlling for contextual differences, but by placing actors firmly within their historical context, and thus ensuring that any moments of recognition between present-day reader and historical subject are all the more powerfully communicated.

Experience and abstraction as sources of scholarly relevance

Another potential area of difficulty when integrating history with organizational studies concerns the actual object of scholarly analysis. At issue here is not so much the way in which research is conducted, but what that research is meant to communicate to its intended audience. Put bluntly, is the purpose of integrating history with theory to create better theory, or to come to a more informed and nuanced understanding of past events? One approach deploys abstract concepts to organize and sharpen our thinking about historical actions and changes. The other aims to make sense of the past by bringing to life the experiences of historical actors. We might think of the former as a study of the invisible forces that help to guide historical change, which can only be grasped at a conceptual level, while the latter is more concerned with the visible manifestation of these changes and the process by which they occurred. This distinction shares some similarity to the ‘narrative/analysis’ dualism that Rowlinson, Hassard, and Decker (Citation2014) refer to, though I would regard both the construction of narratives (about lived experiences) and the creation of abstract theories as types of analysis. In one case the (performative) analytical act involves the transformation of ‘the past’ into a relatable form of ‘history’. In the other ‘history’ is utilized to create a more historically informed version of theory.

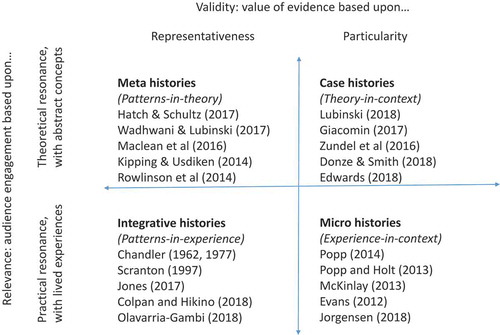

Bringing these two dimensions together allows us to construct a 2 × 2 matrix that helps to illustrate the different ways in which the work of historians and organization theorists intersect (see ). This is not the first attempt to create such a matrix (and will probably not be the last), but it is intended to offer a practical guide to those thinking of submitting papers to MOH about the plurality of approaches that the journal seeks to encourage. To make the framework more meaningful, I have populated each quadrant of the matrix with some examples. As a test of its usefulness, I have also attempted to locate each of the papers published in the current issue on the chart.

The top-left quadrant of the matrix has been labeled meta-histories. These are studies that seek to create theoretical frameworks or models on the basis of evidence that is deemed to be representative. Many of the recent attempts to map out (and theorize) the position of history within organizational studies fall into this category. In most cases, the examples cited draw on existing academic literature as source material, and go to some lengths to substantiate the representativeness of this evidence base. Hatch and Schultz (Citation2017, 663) base their study on the use of history by a single organization (Carlsberg), but stress the use of ‘purposeful sampling’ in their process of data collection. Studies do not need to be based on large datasets to be positioned within this quadrant, but they do seek to establish theoretical patterns that will be repeatable in different contexts. The category of serial history, which is ‘predicated on finding a series of “repeatable facts” that can be analyzed using replicable techniques’ (Rowlinson, Hassard, and Decker Citation2014, 265) also fits comfortably within this sector of the matrix.

Moving to the top-right of the chart, case histories continue to focus primarily on making a theoretical contribution, but do so by stressing the distinctiveness of the research context – rather than its representativeness. As Lopes, Casson, and Jones (Citation2018) put it, ‘it is not a single exotic animal that historians discover, but rather an entire zoo.’ Lubinski (Citation2018) shows how the effectiveness with which German firms were able to strategically deploy their history in 1930s India was strictly tied to the political context in which they operated. Zundel, Holt, and Popp (Citation2016, 231) cover a wide range of corporate histories in their study, but conclude by emphazising not common patterns, but rather the ‘anomaly, disjuncture and asynchronicity that is offered when the past is understood as an altogether different country.’ Giacomin’s (Citation2017) study adds to our understanding of cluster formation, and particularly the role of governments in this process, by focusing specifically on a case which is not characterized by political stability, free-markets and dominant indigenous firms. Here it is the distinctiveness of the context, rather than its representativeness, that adds to its theoretical usefulness. A similar argument is made in the paper by Donzé and Smith (Citation2018) in this volume.

The bottom-left quadrant of our matrix consists of studies that claim to be representative in some way, but their purpose is to identify historical trends (patterns-in-experience) rather than theoretical axioms. This often involves the construction of complex and multilayered narratives which lend themselves more to the format of the research monograph than the journal article. The examples cited here include seminal works by Chandler (Citation1962, Citation1977) and Scranton (Citation1997), which offer starkly contrasting accounts of American industrialization, while both representing important and widespread aspects of American experience. Jones’s most recent (Citation2017) book, similarly seeks to address a big topic (business and the environment) by constructing a complex narrative. The distinctiveness (or eccentricity) of individual entrepreneurs is highlighted, and their complex motivations recognized, but by bringing enough of these together across time and space, wider patterns can be drawn out. Similarly, Colpan and Hikino’s (Citation2018) wide ranging analysis of business groups draws on an extensive sample of cases from differing historical and national contexts to challenge existing theoretical explanations about this important form of business organization. Olavarria-Gambi’s (Citation2018) contribution to the current volume is also located here, focussing as it does on the issue of state reform in historical perspective. The emphasis of the study is on the practical experience of political reform, rather than abstract reasoning, and the focal context (Chile) is justified because of its similarity with other mature western democracies (in terms of political stability) rather than its differences.

Finally, the bottom-right sector, micro-histories, includes work which is concerned with lived experiences rather than abstract concepts but which also focuses on contextual particularities rather than general patterns. This approach overlaps very considerably with what Rowlinson, Hassard, and Decker (Citation2014, 266) refer to as ethnographic history, in which researchers analyze archival ‘texts’ as a means of interpreting the wider culture – a theoretical perspective they describe as ‘angular’. Researchers in this vein are reluctant to impose contemporary theoretical concepts on the historical actors they study, but instead attempt to understand them on their own terms. The value of this work lies in the peculiarities and complexities of the individual cases studied, which allow for valuable insights to be generated into individual (and organizational) behaviors. By closely scrutinizing the archival traces left by successful entrepreneurs (Popp and Holt Citation2013), cotton speculators (Popp Citation2014), bank clerks (McKinlay Citation2013) or even material objects such as the plantation hoe (Evans Citation2012) historians have provided new perspectives on, and a richer understanding of, organizational life. From the current volume, Jorgensen’s (Citation2018) vignettes on Carl Jacobsen come closest to this model of research.

Clearly, the matrix outlined here is not intended to be all-encompassing. Not all forms of management or organizational history will necessarily sit neatly in one of these four boxes. In many cases, work will straddle two or more of the quadrants, and there will no doubt be studies that do not map comfortably onto this framework at all. The intention behind it is to offer a guide to those considering MOH as a potential outlet for publication about the different ways in which history and organization studies can be integrated, and to provide a tangible outline of what a plurality of approaches to organizational history means in practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Argyres, N., A. De Massis, N. Foss, F. Frattini, G. Jones, and B. Silverman. 2017. “History and Strategy Research: Opening up the Black Box (Call for papers).” Strategic Management Journal.

- Booth, C., and M. Rowlinson. 2006. “Management and Organizational History: Prospects.” Management and Organizational History 1 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1177/1744935906060627.

- Chandler, A. 1962. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chandler, A. 1977. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Clark, P., and M. Rowlinson. 2004. “The Treatment of History in Organisation Studies: Towards an ‘Historic Turn’?” Business History 46 (3): 331–352. doi:10.1080/0007679042000219175.

- Colpan, A., and T. Hikino. 2018. “The Evolutionary Dynamics of Diversified Business Groups in the West: History and Theory.” In Business Groups in the West: Origins, Evolution, and Resilience, edited by A. Colpan and T. Hikino. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 26–69.

- Coraiola, D., W. Foster, and R. Suddaby. 2015. “Varieties of History in Organizational Studies.” In Routledge Companion to Management and Organizational History, edited by P. McLaren and A. Mills, 1–28. London: Routledge.

- Decker, S. 2016. “Paradigms Lost: Integrating History and Organization Studies.” Management and Organizational History 11 (4): 364–379. doi:10.1080/17449359.2016.1263214.

- Decker, S., M. Kipping, and D. Wadhwani. 2015. “New Business Histories! Plurality in Business History Research Methods.” Business History 57 (1): 30–40. doi:10.1080/00076791.2014.977870.

- Donzé, P. Y., and A. Smith. 2018. “Varieties of Capitalism and the Corporate Use of History: The Japanese Experience.” Management and Organizational History 13: 3.

- Edwards, P. 2018. “The Contingencies of Corporate Failure: The Case of Lucas Industries.” Management and Organizational History 13: 3.

- Evans, C. 2012. “The Plantation Hoe: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Commodity, 1650–1850.” The William and Mary Quarterly 69 (1): 71–100. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.69.1.0071.

- Foster, W., D. Coraiola, R. Suddaby, J. Kroezen, and D. Chandler. 2017. “The Strategic Use of Historical Narratives: A Theoretical Framework.” Business History 59 (8): 1176–1200. doi:10.1080/00076791.2016.1224234.

- Giacomin, V. 2017. “Negotiating Cluster Boundaries: Governance Shifts in the Palm Oil and Rubber Cluster in Malay(Si)A, C.1945–1970.” Management and Organizational History 12 (1): 76–98. doi:10.1080/17449359.2017.1304861.

- Godfrey, P., J. Hassard, E. O’Connor, M. Rowlinson, and M. Ruef. 2016. “What Is Organizational History: Toward a Creative Synthesis of History and Organization Studies.” Academy of Management Review 41 (4): 590–608. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0040.

- Hatch, M., and M. Schultz. 2017. “Toward a Theory of Using History Authentically: Historicizing in the Carlsberg Group.” Administrative Science Quarterly 62 (4): 657–697. doi:10.1177/0001839217692535.

- Jones, G. 2017. Profits and Sustainability: A History of Green Entrepreneurship. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jorgensen, I. 2018. “Creating Cultural Heritage: Three Vignettes on Carl Jacobsen, His Museum and Foundation.” Management and Organizational History 13: 3.

- Kipping, M., and B. Usdiken. 2014. “History in Organization and Management Theory.” Academy of Management Annals 8 (1): 535–588. doi:10.5465/19416520.2014.911579.

- Lipartito, K. 2014. “Historical Sources and Data.” In Organizations in Time: History, Theory, Methods, edited by M. Bucheli and D. Wadhwani, 284–304. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lopes, T., M. Casson, and G. Jones. 2018. “Organizational Innovation in the Multinational Enterprise: Internalization Theory and Business History.” Journal of International Business Studies. Accessed June 2018.

- Lubinski, C. 2018. “From “History as Told” to “History as Experienced”: Contextualizing the Uses of the Past.” Organization Studies. Published online October 2018. doi: 10.1177/0170840618800116.

- Maclean, M., C. Harvey, and S. Clegg. 2016. “Conceptualising Historical Organization Studies.” Academy of Management Review 41 (4): 609–632. doi:10.5465/amr.2014.0133.

- McKinlay, A. 2013. “Banking, Bureaucracy and the Career: The Curious Case of Mr Notman.” Business History 55 (3): 431–447. doi:10.1080/00076791.2013.773683.

- Mills, A., R. Suddaby, W. Foster, and G. Durepos. 2016. “Re-Visiting the Historic Turn 10 Years Later: Current Debates in Management and Organizational History – An Introduction.” Management and Organizational History 11 (2): 67–76. doi:10.1080/17449359.2016.1164927.

- Olavarria-Gambi, M. 2018. “Public Management and Organizational Reform in Historical Perspective: The Case of Chile’s State Reform and Public Management Modernization of the 1920s.” Management and Organizational History 13: 3.

- Popp, A. 2014. “The Broken Cotton Speculator.” History Workshop Journal 78 (1): 133–156. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbt035.

- Popp, A., and R. Holt. 2013. “Entrepreneurship and Being: The Case of the Shaws.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 25 (1–2): 52–68. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.746887.

- Rowlinson, M., and J. Hassard. 2013. “Historical Neo-Institutionalism or Neo-Institutionalist History?” Management and Organizational History 8 (2): 111–126. doi:10.1080/17449359.2013.780518.

- Rowlinson, M., J. Hassard, and S. Decker. 2014. “Research Strategies for Organizational History.” Academy of Management Review 39 (3): 250–274. doi:10.5465/amr.2012.0203.

- Scranton, P. 1997. Endless Novelty: Speciality Production and American Industrialization, 1865–1925. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Üsdiken, B., and A. Kieser. 2004. “Introduction: History in Organisation Studies.” Business History 46 (3): 321–330. doi:10.1080/0007679042000219166.

- Wadhwani, D., D. Kirsch, W. Gartner, F. Welter, and G. Jones. 2016. “Historical Approaches to Entrepreneurship Research (Call for papers for SI).” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal.

- Wadhwani, D., and C. Lubinski. 2017. “Reinventing Entrepreneurial History.” Business History Review 91 (4): 767–799. doi:10.1017/S0007680517001374.

- Wadhwani, D., R. Suddaby, M. Mordhorst, and A. Popp. 2018. “Uses of the Past: History and Memory in Organizations and Organizing”. Organization Studies. Forthcoming SI.

- Zundel, M., R. Holt, and A. Popp. 2016. “Using History in the Creation of Organizational Identity.” Management and Organizational History 11 (2): 211–235. doi:10.1080/17449359.2015.1124042.