ABSTRACT

Drawing on the corporate entrepreneurship (CE) theory, this article examines the rise of the Spanish engineering consulting firm Técnica y Proyectos SA (TYPSA), from its foundation, in 1966, as a project office within a larger national-based construction fgroup, until its consolidation as a family multinational in the 2000s. Our research shows how contextual and intra-organizational changes affect the CE drivers identified by entrepreneurship theory, and highlights resilience as a new element reinforcing entrepreneurial orientation over time. The study also enriches the Chandlerian-biased historical debate by focusing on project-based professional services and assessing the role of decentralization and managerial leadership in corporate entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

The study of innovation processes within industrial corporations has a long tradition among business historians since Chandler’s path-breaking research on the topic (Jones and Wadhwani Citation2008). Yet the term corporate entrepreneurship (CE) was first coined in the management and organization literature of Robert Burgelman (Burgelman Citation1983, 1349), referring to the set of entrepreneurial activities that occur within an existing organization and require new resource combinations (Sharma and Chrisman Citation2007). Burgelman’s work inspired a new wave of research concerned with the drivers and dimensions of firms’ entrepreneurship and the effect of their outcomes on business performance. One of the best-known theoretical contributions in this regard was Miller’s concept of entrepreneurial orientation, understood as the combination of innovation, risk-taking and proactivity in the actions of firms (Miller Citation1983). Much work has been published since then; however, longitudinal and qualitative studies in the domain of CE remain limited, and debates continue regarding its impact and its antecedents, in terms of individual, organizational and contextual factors (Miller Citation2011; Gil-López et al. Citation2020; Pirhadi and Feyzbakhsh Citation2021). Even though entrepreneurial processes would manifest differently in different contexts, context is too often ignored or misunderstood (Miller Citation2011; Wadhwani et al. Citation2020). The deductive and short-term character of management and organization research, however, makes it very difficult to capture the dynamics behind entrepreneurial actions and their links with entrepreneurial contexts, as a longitudinal, holistic and business history approach would do (Milliken Citation2001; Cuff Citation2002; Cooper and Martyn Citation2006; Short et al. Citation2010; Miller Citation2011; Tajeddini and Mueller Citation2012; Gil-López et al. Citation2016; Üsdiken, Kipping, and Engwall Citation2013; Wadhwani Citation2015; Wadhwani and Jones Citation2014; Wadhwani et al. Citation2020). Context specificity may limit the generality of findings but it can enhance application, generating more fine-grained and empirically valid knowledge (Lincoln and Denzin Citation2005). Additionally, CE has been explored almost exclusively in the field of technology and manufacturing firms, leaving other types of companies and industries overlooked.

This paper aims to contextualize CE through a historical case study approach, understanding context as embedding and shaping entrepreneurial action (Wadhwani et al. Citation2020). It does so by examining the entrepreneurial process within a knowledge-based company, the Spanish engineering consulting firm Técnica y Proyectos S.A. (TYPSA), from its origins, as a project office within a larger national-based construction group in 1966, to its consolidation as a family multinational in the early 2000s. We connect TYPSA’s entrepreneurial processes with its surrounding institutional and economic context. Our proposal of industry, context and company to be studied deserves explanation. Regarding the former, engineering consulting firms apply scientific and technical knowledge to the development of customized solutions to their clients’ needs, which can range from specific processes and small building works to large public, residential or industrial works (Empson et al. Citation2015). Knowledge, embedded within both their staff and corporate routines, and absorbed through formal training as well as partnerships, among others, is therefore essential to reputation building and success. Additionally, the business works around projects. Their temporary, one-off-problem-solving character, the role of teamwork and partnerships to complement economic, technological or other resources, and their focus on non-durable structures mean that projects do not fit neatly into managerial hierarchies, making entrepreneurial action particularly critical (Scranton and Fridenson Citation2013). This explains our interest in CE in this sector.

Furthermore, this industry underwent a profound change after World War II, when American contractors revolutionized and led the global market through the introduction of the complex-to-handle project management and turnkey projects, where consulting firms or contractors took charge of the entire planning and execution process (Rooij and Homburg Citation2002; Rooij Citation2004). At the same time, ‘modern’ engineering consulting firms consolidated into independent companies from larger construction or industrial groups, while the need for management education spread across European engineers – albeit not necessarily smoothly (Nygaard Citation2020). The ‘American way’ was echoed in the Spanish market as well, pushing the transformation of at least part of the domestic companies, quite often in direct or indirect partnerships with American peers while frequently remaining part of larger construction or industrial groups (Álvaro-Moya Citation2014). This took place at a time of rapid economic growth and rising public investment in a still rather protected domestic market. The lack of domestic infrastructure created opportunities for the most dynamic firms, whose ability to accumulate expertise and project-execution capabilities became essential for their later internationalization, as observed by Guillén and García-Canal (Citation2011), on Spanish multinationals in Torres (Citation2009, Citation2011, chapter 3), on the construction sector. In fact, the rapid increase in construction works drove some groups to develop their own in-house engineering services firms. Dealing with bureaucracy in public biddings, as well as with high regulation in terms of price and procedures, would also have prompted political capabilities among the Spanish firms, facilitating their future expansion abroad into imperfect markets (Guillén and García-Canal Citation2011).

The industry context, however, changed dramatically with the oil crisis and the Spanish transition to democracy in the late 1970s. The entrance into the European Economic Community in 1986 posed new challenges for domestic engineering firms in terms of market liberalization and increasing competition, but also brought new opportunities as European funds combined with Spanish government’s plans to modernize infrastructures, among other public works (Ministerio de Fomento Citation1998). The rise of public biddings drove many firms, particularly in the engineering civil sector, to focus on the domestic market (Torres Citation2009; Ministerio de Fomento Citation1998) – a curious phenomenon given the clear, contemporary internationalization of the Spanish economy, when outward foreign investment surpassed inward in the late 1990s (Guillén Citation2005, 11).

Founded in 1966 with a staff of 25 people, TYPSA was one of the first Spanish consulting firms to operate independently from a larger construction or industrial group (Álvaro-Moya Citation2014). In the period analyzed, the company underwent a profound process of organizational change, and business and geographical diversification, led by one of its first senior managers and ultimately the largest shareholder. At the turn of the century, TYPSA was a consulting and engineering services group working in the infrastructure, energy, environmental and city solution fields, and with offices in five continents. By the end of 2019, nearly 80% of the group’s production took place outside Spain, while 58% of its 2,818 employees were working abroad.Footnote1 In terms of turnover, it ranked 24th in the Spanish market – out of almost 7,000 registered companies in total – and 58th internationally – out of 225 –, behind only three other Spanish companies (El Economista Citation2020; Engineering News Record Citation2020).

Although our methodology focuses on an industry-contextualized historical case study, we also pay attention to the particular actors that comprised the organization and, in particular, to the alma mater of the company under discussion (Wadhwani et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, we combine our narrative approach with a discussion of theoretical frameworks, identifying key, historically-based implications. Our empirical evidence constitutes an extensive collection of written and oral sources collated as part of a commissioned business history project on the history of TYPSA. Consequently, we were afforded unrestricted access to these sources for research purposes. Primary sources include annual and financial reports, studies scanning the business environment for strategic purposes, top managers’ discourses to staff, and interviews of more than ten top managers working in different units within the period under analysis. Following historical triangulation purposes (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) and source criticism (Wadhwani Citation2016), we contrasted and complemented primary sources with secondary ones, such as professional journals and industry reports. These documents allowed us to supplement, corroborate and triangulate data from distinct interviews and internal company sources, avoiding the limitations associated with relying on single sources (Kipping, Wadhwani, and Bucheli Citation2014).

Our research, focused on the history of TYPSA, responds to different calls for more historical and qualitative studies that can shed light on how CE develops over time and the causal relationship between CE, the firm’s context, and performance (Argyres et al. Citation2020; Miller Citation2011; Hornsby, Peña-Legazkue, and Guerrero Citation2013; Kuratko and Audretsch Citation2013; Gil-López et al. Citation2020; Pirhadi and Feyzbakhsh Citation2021). Our approach also advances research focusing on how institutional contexts shape entrepreneurial processes (Miller Citation2011; Pirhadi and Feyzbakhsh Citation2021). This is particularly interesting in evolving institutional settings such as those experienced by our company: from a non-democratic, yet expansive context until 1975, to an open, improved, and democratic environment since 1985, through a very turbulent period shaped by the oil shocks and the Spanish transition to democracy between 1975 and 1985. Our research also responds to calls for more studies focused on individual and organizational factors that drive CE or increase the possibility of CE success (Pirhadi and Feyzbakhsh Citation2021). In this regard, we identify resilience as a critical (but underexplored) dimension of CE. Resilience emerges as a process leading to organizational reliability, underpinned by organizational alertness to opportunities and willingness to take risks and bold decisions in an uncertain and complex context (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld Citation1999). Finally, our paper enriches the academic discussion on corporate entrepreneurship by integrating an industry overlooked by scholars, i.e. professional services.

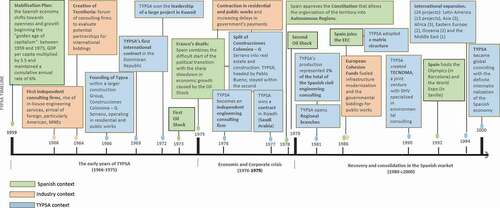

The article is structured as follows. After summarizing the theoretical framework, we analyze the history of TYPSA from its origins to its consolidation as a family multinational group. We differentiate three periods in which the company took critical decisions to face a changing context and exploit opportunities through CE: from 1966 to 1975, when TYPSA was not yet an independent company, but launched its first international project within a Spanish consortium; from 1976 to 1979, when TYPSA became independent and sharpened its international focus amidst economic and political crises within and outside Spain; and between 1980 and 2000, as TYPSA took advantage of the opportunities presented by the allocation of European funds, the reorganization of the Spanish administration, and new market demands towards sustainability. shows an overview of the history of TYPSA, connected with milestones in the industry and the Spanish context. Our narrative is guided by analysis of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation, according to five dimensions identified in the literature: proactivity, innovation, autonomy, competitive aggressiveness, and risk-taking. The paper closes with a discussion of the TYPSA case in light of CE theory, offering pertinent conclusions.

2. Corporate entrepreneurship in the management and business history literature: bridging the gap

Although scholarship has traditionally focused on the individual character of ‘the entrepreneur’ and the entrepreneurial outcome in terms of venture creation, entrepreneurship is also a process associated with strategic and renewal activities within existing firms (Jones et al. Citation2013; Roscoe, Cruz, and Howorth Citation2013; Baden‐Fuller Citation1995; Morris and Kuratko Citation2002; Tajeddini and Mueller Citation2012; Miller Citation2011; Sharma and Chrisman Citation2007; Zahra Citation1986, Citation1995, Citation1996; Zahra and Covin Citation1995; Wadhwani and Lubinski Citation2017). Initially conceptualized by Burgelman in the early 1980s, leading to a proliferation of theoretical and conceptual perspectives on CE, Sharma and Chrisman (Citation1999) undertook the first systematic attempt to standardize and clarify terminology in the field (Morris and Kuratko Citation2002; Parker Citation2011). These authors defined CE as ‘the process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organization, create a new organization or instigate renewal or innovation within that organization’ (Sharma and Chrisman Citation2007, 18).

Apart from terminology clarification, another important concern of scholars has been measuring CE as a means of distinguishing between entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial companies. The most successful efforts here have been the studies by Miller (Citation1983), Covin and Slevin (Citation1989) and Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996), which introduced the concept of entrepreneurial orientation, understood as a firm’s attitude towards entrepreneurship and innovation with visible implications for business processes, decisions and corporate culture (Miller Citation1983; Covin and Slevin Citation1989; Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996). Entrepreneurial orientation, as originally considered, emerges from the interplay of three distinct dimensions: (i) innovation, (ii) risk-taking and (iii) proactivity. Thereby, an entrepreneurial organization is defined as one that innovates, accepts risk and shows a forward-looking approach by introducing new products or services ahead of the competition and by anticipating future market needs or preferences (Lassen, Gertsen, and Riis Citation2006). While these dimensions may be applicable to other types of entrepreneurial processes, they capture the essence of CE (Zahra and Covin Citation1995). Competitive aggressiveness, understood as firms’ response to environmental threats, and autonomy, referring to the independent action of organizational players, were also added as dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation by Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996). Proactivity gives any organization the ability to launch new products, services or solutions on the market in advance of its competitors, and, as an organizational process (Covin and Slevin Citation1989), it is directed towards the search for new business opportunities, not towards the optimization of existing resources (Stevenson and Jarillo Citation1990). A proactive and competitive attitude, therefore, requires that an organization be aware of changes or threats to its environment, and of potential market demands, in order to capitalize on opportunities ahead of competitors. Proactivity and competitive aggressiveness both embody actions towards market positioning. Yet Lumpkin and Dess (Citation2001) made a distinction between the two concepts, stating that, whereas proactivity is more inclined towards a firm’s response to opportunities in dynamic or fast-growing markets, competitive aggressiveness better captures the response by firms facing threats posed by hostile environments or mature markets (Lumpkin and Dess Citation2001).

Management literature has also investigated how entrepreneurship within firms can be stimulated or constrained by sets of external and internal environmental factors (Lumpkin and Dess Citation2001; Kearney, Hisrich, and Roche Citation2009). Scholars appear to believe that organizational structure (Morris and Jones Citation1999), decision making (Bozeman and Kingsley Citation1998; Nutt Citation2005), motivation (Baird and St-Amand Citation1995; Hornsby, Kuratko, and Zahra Citation2002) and organizational culture (Covin and Slevin Citation1991) are the most consistent intra-organizational elements. It is generally assumed that organizations with less formalized structures, more flexible and decentralized decision-making procedures, a lower degree of formalization in the control system and higher rewards and motivation also demonstrate higher levels of entrepreneurship. Regarding the external environment, research has demonstrated that external conditions have a strong, if not deterministic, influence on the existence and effectiveness of entrepreneurial activity (Covin and Slevin Citation1989). Dynamism, hostility, and heterogeneity are the environmental features most cited by research. In short, dynamism and heterogeneity of the environment reflect the uncertainty faced by an organization due to political, social, technological, and economic changes. Hostile environments, meanwhile, refer to the degree of rivalry and competitive intensity and the abundance or scarcity of resources in the market; environmental hostility increases with heightened competition and resource scarcity. Dynamism, hostility and heterogeneity of the environment tend to be positively related to the entrepreneurial orientation of organizations (Ruiz‐Ortega et al. Citation2013; Lumpkin and Dess Citation2001).

An important vein of research has also examined the performance implications of entrepreneurship in different contexts. Alvarez and Busenitz (Citation2001) suggest that an innovative, proactive orientation which favors the assumption of moderate risks can stimulate organizational growth. Zahra, Jennings, and Kuratko (Citation1999), Zahra and Covin (Citation1995) and Wiklund (Citation1999) offer similar arguments, assuming the existence of a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and the organization’s results. Interestingly, the metric of these results has sparked much debate among researchers since there is no consensus on how to tackle organizational ‘performance’. Some of the most widely used dimensions of performance include economic profit (Schumpeter Citation1934 and Citation1975; Zahra and Covin Citation1995), product innovation (Jennings and Young Citation1990), business growth (Baum, Locke, and Smith Citation2001), public welfare and social legitimacy (Pfeffer Citation1994), or simply personal satisfaction (Miner Citation1997), among others. While an analysis of CE’s impact on business performance is beyond the main objectives of this article, we explore the performance and success of our case company, TYPSA, using some of these factors, particularly profit, innovation and business growth.

The study of CE has a long tradition in the business history research agenda. Chandler’s seminal works on the modern industrial corporation spawned countless case studies of major companies operating in different institutional and historical contexts (Jones and Wadhwani Citation2008; Amatori Citation2006). Thanks to such an extensive academic effort, we enjoy a better understanding of innovation within large (usually industrial) enterprises, of how innovation leads to industry change, and how the historical context influences corporate behavior. Part of this literature has untangled, furthermore, the corporate drivers to international venturing and the making of global businesses after the pioneering, Chandlerian-influenced studies of Mira Wilkins on the field (Wilkins Citation2008; da Silva Lopes, Lubinski, and Tworek Citation2019). Business History scholarship has also placed considerable emphasis on entrepreneurship within family firms. Although research has not focused on CE, it has tried to identify which exact features, related to family ownership, might strengthen entrepreneurial attitudes (Colli et al. Citation2013, San Román, Puig, and Gil-López Citation2020; San Román et al. Citation2021). The so-called new entrepreneurial history, for its part, argues in favor of the study of entrepreneurial processes rather than focusing on actors, hierarchies or institutions, as previous approaches had done (Wadhwani and Lubinski Citation2017). Those processes – envisioning and valuing opportunities, allocating and reconfiguring resources, and legitimizing novelty – are susceptible to being examined, we can conclude, both from an individual and a corporate perspective. Business historians, in any case, have usually applied a very loose definition of entrepreneurship, if any, leading to recent calls for a clearer conceptualization (Lubinski and Wadhwani Citation2019; Perchard et al. Citation2017). In fact, most of the business history research has developed separately from the CE theoretical framework (Jones and Wadhwani Citation2008; Zahra, Jennings, and Kuratko Citation1999; Corbett et al. Citation2013). This lack of interaction between historical empiricism and theory has been unfortunate, since bridging the gap between them can enrich the study of CE through generating more contextually-informed theories as well as more theoretically-guided narratives, as demanded by a number of recent calls from both management and business history scholars (Üsdiken, Kipping, and Engwall Citation2013; Wadhwani and Jones Citation2014; Wadhwani Citation2015; Mills et al. Citation2016; Wadhwani et al. Citation2020).

This paper aims to reduce this gap in existing scholarship by contextualizing corporate entrepreneurial orientation through a historical case study approach. More concretely, we examine the entrepreneurial process within a knowledge-based company, the engineering consulting firm Técnica y Proyectos SA (TYPSA), in the light of both CE theory and business history methods.

3. The early years of TYPSA (1966-1975)

Técnica y Proyectos SA (TYPSA) was founded in 1966 within a larger construction group (Construcciones Colomina – G. Serrano) to meet its demand for engineering services, a common strategy in the industry at that time (Álvaro-Moya Citation2014).Footnote2 The group, one of the largest in the domestic market and operating in residential and public works, was growing fast, as was the construction industry as a whole. After the isolation and economic stagnation following the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), the liberalizing measures adopted by the government in 1959 fueled economic growth, structural change and convergence with the European leaders. Spain’s GDP grew on average 8.3% annually, a rate significantly above the European average (Carreras and Tafunell Citation2021, 30). In this context of growth, the State decided to outsource public works projects, which had previously been under the domain of the Spanish Ministry of Public Works. This decision created a fantastic business opportunity for national project offices, as subsidiaries of foreign companies were not authorized to participate in any public bidding (Torres Citation2009).Footnote3

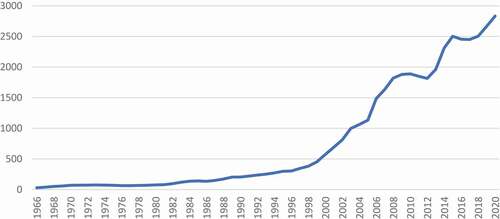

TYPSA was organized around two businesses: architecture and engineering services. In the former, TYPSA commanded a wide client portfolio, largely from the wide array of residential works in which the group Construcciones Colomina – G. Serrano was involved. However, the in-house demand for engineering services was not large enough to guarantee the viability of the consulting branch. This situation forced TYPSA to compete aggressively in the market, participating in all possible biddings, learning by doing, preparing a competitive proposal and building its reputation. In the following years, and fueled by the country’s rapid urbanization, TYPSA participated in the modernization of a wide range of national infrastructures. Production (the value of the services provided) increased more than 16 times over between 1966 and 1970, and staff numbers rose to 70 employees (see Appendix). That said, TYPSA’s staff headcount still ranked as average, significantly below state-owned firms and private industrial groups at that time, which numbered in the hundreds or even thousands (Ministerio de Industria y Energía Citation1978).

TYPSA also played a role in the early internationalization of the industry through its membership of Tecniberia, a national association of engineering and consulting companies sponsored by the government to support the exportation of Spanish engineering consulting services – and accumulated foreign currency as a result. As Spanish firms lacked the financial resources, experience, and reputation to go international, Tecniberia was created in 1964 as a forum where consulting firms could evaluate potential partnerships to gather sufficient resources for international biddings (Álvaro-Moya Citation2009). Through this formula, in 1969 TYPSA achieved its first contract abroad to plan and supervise the school construction program sponsored by the World Bank in the Dominican Republic.Footnote4 Three years later, the company won the leadership of a large project in Kuwait. As a result of the work carried out and the experience acquired, by the mid-1980s TYPSA was already among the main Spanish companies exporting civil engineering services in residential and public works, with 20 contracts signed in the Middle East and Latin America (Álvaro-Moya Citation2009). These were the regions in which Tecniberia had focused most of its networking activities.

The first overseas projects represented a vital learning experience for TYPSA, forced to work to different standards and to overcome the disadvantages of operating in unfamiliar, foreign markets (Zaheer Citation1995). The case of the Kuwait project is highly illustrative in this regard.Footnote5 The definition of the final proposal was the result of lengthy discussions between TYPSA’s president (Pablo Bueno Sáiz) and different levels of the Kuwaiti administration regarding the project details, as well as quality and time compliances. To start those conversations, a third-party intermediary – a local agent providing advice on the local administration requirements – proved essential. The contact was provided by the representative of a Spanish oil distribution company operating in the country, who also helped TYPSA critically to analyze the first drafts of its proposal.Footnote6 The resulting careful, personalized and painstaking relationship with the client became TYPSA’s modus operandi and proved essential for the company’s later expansion in the region.Footnote7

Since the very beginning of its history, TYPSA showed proactivity and competitive aggressiveness in responding to market opportunities and dealing with contextual challenges (Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996; Martin and Lumpkin Citation2003). This forward-looking approach to business became one of TYPSA’s essential pillars of entrepreneurial orientation, seeking opportunities in the market of engineering services from its inception through to its early internationalization, as we have explored.

4. Economic and corporate crisis (1976-1979)

The oil crisis and the transition to democracy after Francisco Franco’s death in 1975 plunged the Spanish economy into a severe recession that lasted until 1986, when the country joined the European Economic Community. In 1973, the end of the Bretton Woods exchange system and the rise in oil prices caused a severe economic crisis within industrialized countries. After Franco’s death in 1975, two years passed before the first democratic elections in Spain were held, in June 1977. The first democratic governments had to cope with the severe economic crisis, the rise of terrorism and the opposition to democracy that culminated in the coup d’état of 1981 (Carreras and Tafunell Citation2021, 189–209). Construction and engineering did not escape these adverse conditions. The crisis marked an end to the previous period of prosperity, causing a contraction in residential and public works and increasing the already considerably delays in government payments (SEOPAN Citation1984, 29). Consequently, the smaller construction firms and those too focused on the domestic market went bankrupt or were absorbed by larger groups. Construcciones Colomina – G. Serrano, TYPSA’s owner, was facing not only these difficulties in the domestic market, but also severe confrontation in top management positions following the retirement of its two founders. Ultimately, this triggered a split amongst the group into two founding divisions: real estate and construction.Footnote8 TYPSA, headed by Pablo Bueno, stayed within the second.

TYPSA managers soon realized that being part of a declining construction group focused on the domestic market could prove fatal.Footnote9 In order to survive and continue growing, the company needed independence and a stronger position in emerging markets. Accordingly, the Board decided to acquire TYPSA for its book value through a Management Buyout.Footnote10 The sale took place on 13 July 1976 making TYPSA one of the first Spanish engineering companies to operate completely independently from, and without shareholder ties to, any other business group (that is, a ‘modern’ engineering consulting firm). Pablo Bueno, with 500 shares or 5% of the share capital, became the main shareholder, a position that grew in subsequent years.Footnote11

The early period as an independent consultant were not easy.Footnote12 Although 1976 eventually saw a profit, thanks to TYPSA’s work abroad, by late 1977 the company was on the verge of collapse due to the cancellation of some of the its ongoing projects and of public biddings.Footnote13 This same year, a new project, awarded after three selection rounds from among 80 international submissions, and successively extended until the present day, gave the company a fresh direction for the future: the brand-new campus of Imam Mohammed Bin Saud University, with capacity for 20,000 students, including commercial, residential and public works. In short: a city for some 30,000 people (Cembrero Citation1983).Footnote14 The project, with an estimated investment volume of (current) USD 2,000 million, was the largest ever granted to a Spanish company.Footnote15 Moreover, it was the largest to be developed in a region, the Middle East, where the presence of Spanish engineering firms was by then unreliable.Footnote16 Thanks to this contract, by 1981 TYPSA’s production represented 2% of the total Spanish civil engineering consulting sector, with the company’s exports accounting for 70%.Footnote17

The Saudi venture marked a turning point in TYPSA’s fortunes. Not only had it saved the company from bankruptcy after several months of wage cuts and red numbers, but it also established TYPSA’s financial policy and international orientation for the following years. The distress prior to gaining the Saudi project was so immense, the company’s financial capacity so reduced, and the borrowing cost so high, that TYPSA’s president was determined to avoid, if at all possible, a similar scenario in the future. Since then, the company allocates at least 60% of its profits to increasing equity, which represents at least 50% of the total assets (and around 60% in the 1980s).Footnote18 Moreover, business and regional diversification became a permanent aim.

The Arabian project also allowed TYPSA to increase its expertise in foreign markets, managing expatriation policies and learning from the methods and standards applicable in other countries.Footnote19 TYPSA gradually incorporated those international standards into its own organizational routines, a key asset when, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, the company accelerated its international expansion.Footnote20

Looking back at the five dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation, it seems clear that TYPSA’s internationalization and diversification strategies clearly epitomized proactivity, starting with the company’s early orientation towards foreign markets as a response to crises in the domestic domain. Indeed, the award of the university project in Saudi Arabia afforded TYPSA a strong and pioneering position compared to other Spanish companies, in a promising market for the engineering consulting industry.

Entrepreneurial risk-taking was also crucial to ensure firm endurance. Our results show TYPSA’s clear willingness to take risks, including venturing into the unknown and committing a relatively large proportion of assets (Lassen, Gertsen, and Riis Citation2006). These two dimensions of risk were particularly evident when TYPSA decided to go for broke and seek an external client as distant, risky and complex as the Saudi State, and thus undertook a project as substantial as the Imam Mohammed Bin Saud University in Riyadh. The initiative involved operating in an unknown context and on a scale never before achieved, committing an enormous amount of resources, which greatly increased the financial burden on the company’s capital. TYPSA’s risk-taking is even more evident when compared to other companies in the sector that adopted a more conservative approach to the business in terms of both resources committed and geographical scope of operations. Interestingly, the risks taken set a precedent and influenced further decisions in TYPSA’s case; for instance, the financial pressure that the Saudi project imposed on the company led to Pablo Bueno’s decision to finance the company’s operations with its own funds in the following years.

5. Recovery and consolidation in the Spanish market (1980-c.2000)

The 1980s represented a period of democratic consolidation and international opening for Spain, with the entry into the European Common Market in 1986 marking a turning point in the diplomatic and economic history of the country. The relative backwardness of the Spanish economy qualified for access to European Cohesion Funds, which fueled infrastructure modernization and, as a result, governmental biddings for public works. In addition, the choice of Barcelona and Seville in 1992 as venues, respectively, of the Olympic Games and the Universal Exhibition, together with the first governmental plan to construct a national highway network, drove the expansion of the engineering and construction sectors (Ministerio de Fomento Citation1998). In 1992, Spain was considered the fifth most promising market in Europe for engineering professional services (European Innovation Monitoring System Citation1995). This opening-up to Europe also brought interesting internationalization opportunities for Spanish companies, reinforced by the attractive tax treatment of income from business investments abroad (Paredes Gómez Citation1992). Moreover, new opportunities arose in Spain with the growth of new services related to renewable energies and environmental, airport and air navigation engineering.Footnote21

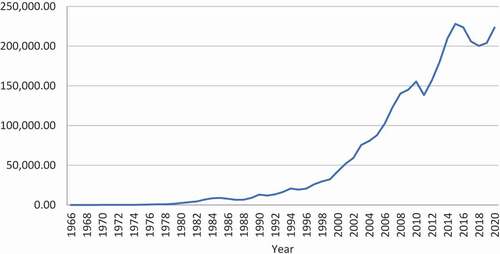

This economic opening-up also generated greater competition in an industry where, in 1995, 90% of companies had fewer than 5 employees, and only 7% of total civil engineering product was exported, in a highly volatile market where the public sector was still the largest client (Bueno Citation1995, 8; Ministerio de Fomento Citation1998, XIV). By contrast, TYPSA’s portfolio multiplied fivefold throughout the 1980s, from 536 million pesetas in 1980 to 2,838 million in 1990.Footnote22 Most of it still came from abroad (76% in 1986), yet the share of foreign operations fell over the course of the following years: to 50% in 1987 and 30% in the late 1990s.Footnote23 Meanwhile, turnover rocketed (see ) and profits before taxes rose from 70 million pesetas (slightly more than USD 1 million) in 1980 to 300 (USD 4,5 million) in 1999. By then the consulting firm had 477 employees, almost six times more than in 1980 (see ). The number of very qualified employees (university degrees in engineering, architecture or economics) had grown from 21 – that is, 19% of the total – in 1978 (when most of the staff had high technical studies, albeit not in engineering schools) to 93 (45%) in 1990 (with 40% more boasting some kind of technical background).Footnote24

TYPSA’s growth in the 1980s and 1990s was mainly organicFootnote25 and was structured around four pillars: (i) expansion in the domestic market for civil engineering; (ii) creation of regional delegations adapting to the new territorial order of the Spanish State; (iii) diversification, especially towards environmental engineering; and (iv) the export of services to other countries.Footnote26 Regarding the first, TYPSA took part in many of the largest works at the time, including the extension of the Madrid Metro network and several projects related with the modernization of the national highway network, among others. By the early 1990s, 38% of production concerned engineering services in transportation, with 40% involving construction and 22% involving environmental services.Footnote27

The second pillar of TYPSA’s growth consisted of the opening of several branches throughout the national territory. This decision derived from the opportunity to be closer to clients after the reorganization of the national administration into – apart from the central government – 17 regional autonomous units (or ‘autonomous communities’) from 1979, which assumed the responsibility for constructing the majority of new public works.Footnote28 This decision constitutes a notable example of proactivity and competitive aggressiveness as a response to the new administrative order of the Spanish State in the early 1980s. This political decision was followed by a new wave of public, local biddings after their decline in the late 1970s, this time supported by European cohesion funds. Nevertheless, the new regional administration required potential bidders to possess at least a branch office within its area of influence, a requisite that TYPSA cleverly anticipated. In short, it was an organizational innovation that supported a proactive attitude: the search for an agile response to changes in the market.

In order to facilitate coordination between branches (and also with offices abroad) and the projects underway, TYPSA’s president decided to implement a matrix structure. This structure, which Pablo Bueno had learnt about in his first years as an engineer working for a large American group, but which he could not introduce at TYPSA until the company achieved the minimum necessary size, combines teams for each of the projects in progress with functional units by specialization (to which the staff return at the end of the project). The matrix structure also combines general engineers – with a basic command in a wide array of engineering fields – and specialist engineers; that is, a holistic view of the project in progress (general engineers) with the systematic review of scientific advances in each field (specialized engineers) of potential interest to the client’s needs.

This structure allowed the firm easily to adapt to the volatile demand that characterized project-based industries (see Appendix), while offering customized and novel engineering solutions including project management services. Hiring personnel on a contract basis was certainly an alternative, but this entailed high recruitment and selection costs, and above all hindered knowledge accumulation within the firm and the forging of a corporate culture. The matrix structure facilitated the transfer of work between the different national and foreign offices and subsidiaries and the different projects underway, enabling the company to adapt of to changes in demand. While commonplace nowadays in the sector, the matrix structure was extremely rare when implemented by TYPSA, at least among Spanish firms.Footnote29 Its implementation constituted an organizational innovation in TYPSA’s history that highlights the role of innovation as another dimension of entrepreneurial orientation. Within established organizations, CE seeks to support their viability and competitiveness through the utilization of various innovation-based initiatives. Despite the existence of multiple definitions of what actually constitutes innovative activity, most include common features such as the creation of a new product, service, idea, method of production, business structure, or the development of novel forms of combining existent resources (Shane Citation2003; Gürol and Atsan Citation2006; Miller Citation1988; Chandler Citation1962, Citation1990). In line with the Chandlerian approach to entrepreneurship, the case of TYPSA shows the outstanding role of organizational innovation as a way to support greater autonomy in decision-making, increase employees’ engagement, and, as a result, quickly adapt to market trends.

In addition, the matrix structure helped enhance the commitment of employees by making them more involved in decision-making. Therefore, it supported greater autonomy, another dimension for CE, while simultaneously decentralizing decision-making and representing a key element of organizational innovation. This, in turn, helped the firm to match the individual elements of a CE strategy with its external situation by stimulating an entrepreneurial vision, implementing entrepreneurship-supportive reward structures, and engaging in entrepreneurial behaviors in response to environmental hostility (Kreiser, Patel, and Fiet Citation2013). In this sense, an entrepreneurial climate can facilitate the engagement of personnel throughout the firm in the innovation effort (Kuratko, Ireland, and Hornsby Citation2001; Hornsby et al. Citation2009). Aware of the importance of enhancing this engagement, Pablo Bueno also introduced a remuneration system quite unusual in Spain at the time, based on a fixed base plus a share in the company’s profits depending on objective achievement. In addition, employees participated in the company profits and enjoyed direct communication with the top managerial positions, as illustrated by the president’s regular tours around the office, and the results presentation at the end of the year. The determination of an exact professional profile of each of the job categories – from the project manager to the engineering assistants, supervisors, and foremen – in the university project in Saudi Arabia constitutes another example of innovative behavior at an organizational level.

Conscious of the growing public concern with sustainability, TYPSA also pioneered the creation of a subsidiary specializing in environmental consulting. Inaugurated in 1990, this came just three years after the United Nations had first introduced the concept of ‘sustainable development’ and the Montreal Protocol had been signed with a view to protecting the ozone layer, and coincided with the publication of the EEC’s first green paper on environment and sustainability (European Commission Citation1990).Footnote30 Due its lack of experience in this field, TYPSA created the new subsidiary, TECNOMA, as a joint venture with Dutch consulting firm DHV.Footnote31 Although the Spaniards had a controlling participation of 54% in the share capital, the agreement reached meant that some decisions could only be taken unanimously. However, corporate cultures and companies’ vision of the sector were so distant, even affecting the balance sheet (with losses its very first years), that TYPSA decided to acquire the total capital of TECNOMA in 1993.Footnote32 In 1995, the creation of a pioneering laboratory for environmental analysis allowed TECNOMA to triple its turnover rapidly. Tecnoma also provides an example of proactivity. Broadening the Spanish and even the European market, TYPSA – and in particular its president, Pablo Bueno – successfully recognized market and societal changes towards sustainability, quickly capitalizing on this commercial niche.

The fourth and final pillar supporting TYPSA’s growth during the last two decades of the twentieth century was its international expansion. In 1994, when the highest number of projects abroad was achieved (24), TYPSA was operating in Latin America (13 projects), Asia (3), Africa (3), Eastern Europe (2), Oceania (2) and the Middle East (1), including a wide array of services in commercial, residential, environmental and public works.Footnote33 By destination, TYPSA exportation was on a par with engineering consulting as a whole (Álvaro-Moya Citation2009, 104). Contracts were mainly funded by the European Commission (11) and the Inter-American Development Bank (12). Spain’s entrance into the European Economic Community therefore boosted the internationalization of Spanish consulting engineering, including TYPSA. This impact may also hae been enhanced by the permanent offices that Tecniberia, the professional association, established near the headquarters of the World Bank and IMF groups. In the case of TYPSA, however, the importance of the Saudi market, more in terms of contracting volume than number of projects (though not reflected in the previous benchmark), is evident in the fact that ‘Saudi Arabia’ – ‘Middle East’ hereafter – was the firm’s sixth territorial office in 1992, after the previous five on the Spanish mainland.Footnote34 This was a particularity of TYPSA, grounded on its previous projects in the region.

Spain, however, generated the greater part of TYPSA’s income from the late 1980s. Foreign turnover, which exceeded 80% by 1985, rarely exceeded 20% thereafter until 2006.Footnote35 Nonetheless, that continuity in overseas operations, both in promotion and contracting services, provided TYPSA with extensive experience and a wide network of associated consultants which would facilitate, with the turn of the century, its definitive internationalization – as assessed also for other companies within the sector (Torres Citation2009; Gándara Citation2006; Guillén and García-Canal Citation2011).Footnote36 TYPSA became a global group by the turn of the century, coinciding with the definite internationalization of the Spanish economy, as the country’s outward foreign investment surpassed inward investment for the first time in its history.

6. Discussion and conclusion: TYPSA in the light of CE theory

This paper, focused on the history of the engineering consulting firm TYPSA, has examined how and why the company engaged in corporate entrepreneurship. It aimed to contextualize CE theory and enrich dialogue between history and entrepreneurship studies.

Starting from small foundations in 1966, and through an extensive operation abroad and at home, by the early 2000s TYPSA had become a multinational company and leading player in the sector. Indeed, between 1966 and 2000, and despite its turbulent initial years, turnover and staff had increased exponentially – multiplying 900% and 800%, respectively () – and business lines had diversified. Profits, innovation and business growth show the impact of CE on business performance. Moreover, although TYPSA never reached the size of the world’s American giants (Álvaro-Moya Citation2014), the case deserves attention for illustrating how entrepreneurial action took place in a knowledge-based industry and in a late-developing country, as Spain was in the Western context until the mid-1980s. In addition, our case study analyzes an industry based on the execution of customized projects. Their temporary, teamwork-based and one-off-problem-solving character means that projects do not fit neatly into managerial hierarchies (Scranton and Fridenson Citation2013), the focus of traditional Chandlerian studies on entrepreneurship from a business history perspective.

How did TYPSA develop its entrepreneurial orientation in accordance with the theoretical framework synthesized in the second section? Firstly, through organizational innovation, which supported a greater autonomy in decision-making and increased employee engagement, thereby facilitating the company’s rapid adaptation to market trends. Secondly, through its proactive and competitive response to market opportunities at home and abroad. Finally, it promoted entrepreneurial risk-taking through challenging international projects.

The case of TYPSA suggests that behind the five explored dimensions of entrepreneurship at a company level (innovation, autonomy, proactivity, competitive aggressiveness and risk-taking) lie critical internal and external drivers. Regarding the former, literature has highlighted variables such as organizational structure, decision-making processes, control systems, motivation and organizational culture (Baum and Wally Citation2003; Bozeman and Kingsley Citation1998; Baird and St-Amand Citation1995; Heskett and Kotter Citation1992). In general, it is assumed that organizations with less formalized structures, more flexible and decentralized decision-making systems, and a culture that fosters motivation and rewards are those that will show more entrepreneurial orientation. While this research does not dismiss such assumptions, it shows that TYPSA’s CE was also fueled by continuous market prospecting to acquire new knowledge, subsequently absorbed and integrated into company operations. Whereas all novel projects resulted in critical new knowledge to be integrated, their successful completion often depended on the proactive search for technological partners and licensees, subcontractors and other agents with complementary assets. For instance, the Kuwaiti or Saudi Arabia projects provided TYPSA with strategic technical and managerial knowledge on how international engineering worked. However, to develop new ventures like TECNOMA, TYPSA partnered with another company (DHV) which already possessed the strategic knowledge to operate in the new environmental service industry. Therefore, our study of CE in a professional services firm emphasizes the critical role of a proactive attitude to acquire knowledge as an internal driver for entrepreneurship.

Existing literature has also suggested the crucial role of top managers in guiding the ongoing execution of projects and planning for the future (Andrews Citation1980). However, leadership has seldom been theoretically linked to CE, though calls have been made to pay greater attention to the role of the individual in corporate strategy (Corbett et al. Citation2013; Hitt et al. Citation2011). By studying CE in a professional services firm, our paper shows that the human element is what ultimately sustains the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. Indeed, the vision and ambition of TYPSA’s president, Pablo Bueno, proved critical in the company’s engagement in new and challenging projects as well as in organizational change. Accordingly, this research demonstrates the close relationship between innovation and leadership, and calls for a further integration of leadership into CE theory (Ireland, Covin, and Kuratko Citation2009).

Moving now to external drivers of CE, our case study exemplifies the role played by external networks in opportunity identification and the generation of new business opportunities, while assessing the effect of the business context on entrepreneurial action. Regarding networks, TYPSA’s regular participation in a number of international and national forums on engineering and engineering consulting facilitated opportunity identification and strategic knowledge acquisition, which encouraged proactive innovative activity while increasing the likelihood of success.Footnote37 In addition, TYPSA’s integration in the professional association Tecniberia not only facilitated its participation in several projects carried out in the Middle East and Latin America, but it also contributed to reputation building. As an active partner of this association, TYPSA also contributed to reshaping the relationship between its peers and the sector’s main clients (the central and regional governments), and the quality of service offered in public biddings. Success in international biddings, finally, also relied heavily on the selected local sponsors, collectively demonstrating the relevance of networks in sustaining CE behaviors.

The nature of the context in which TYPSA operated directly influenced its orientation towards CE. Yet, what characterized that context? As summarized in the introduction and , the foundation and rise of TYPSA coincided with profound changes in both the external and industry environments. At a national level, the decade of the 1960s was one of rapid growth and rising public investment in public works in a still protected country. This favored the expansion of local consulting firms, but also partnerships with foreigners which offered financial and, above all, technological and reputational resources. Crisis, instability and growing competition followed, building an increasingly mature and fragmented domestic market that rendered geographical and business diversification a key strategy for survival.

Scholarship suggests that the greater the dynamism, hostility, and complexity of the environment, the greater the entrepreneurial orientation of firms (Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996). The case of TYPSA confirms this interpretation. TYPSA faced an extremely unfavorable, complex environment from its earliest years as an independent consultant, which encouraged a proactive search for opportunities to ensure the company’s survival. For instance, the 1970s shock forced internationalization, imprinting the organization with a clear international orientation. The new administrative structure built in the early 1980s fostered the creation of a branch network adapted to the bidding requirements of the new regional governments, and established, within the firm’s culture, the need to be close to potential clients – a policy strengthened with the adoption of the matrix structure. That is, context changes and TYPSA’s adaptation to them embedded the company organization and culture, developing another internal driver of CE directly related to how context shapes entrepreneurial action: resilience. This in turn shows how CE is embedded within contexts that shape – not merely constrain – entrepreneurial agency (Wadhwani et al. Citation2020).

Resilience, as a concept in business and management research relating to the ability to recover under adversity, was originally formulated in two seminal papers by Staw, Sandelands, and Dutton (Citation1981) and Meyer (Citation1982). It is a key trait for entrepreneurs and generally, at an organizational level, is understood as a process leading to firms’ reliability, underpinned by alertness to opportunities and willingness to make decisions in the face of adverse and complex environments (Hedner, Abouzeedan, and Klofsten Citation2011; Linnenluecke Citation2017; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld Citation1999; Chrisman, Chua, and Steier Citation2011). The case of TYPSA allows us to extend the conceptualization of resilience and interpret it as a powerful internal driver for CE, which emerges from the firm’s contextual embeddedness. Entrepreneurial resilience, in TYPSA’s case, arises from the adverse, complex environment that the organization had to deal with from its conception. However, its commitment to survive despite that adversity, from the outset, created a culture of resilience that reinforced CE over time as a way to tackle and respond to future adversity and opportunities.

In sum, our study illustrates the role of some of the entrepreneurial processes proposed by the so-called new entrepreneurial history (Wadhwani and Lubinski Citation2017), such us how organizations pursue and exploit opportunities through external networks (i.e. Tecniberia, engineering professional associations and national and international forums), and the role played by managers’ professional backgrounds (i.e. TYPSA’s president) and emotional reactions to adverse circumstances (i.e the 1970s crisis) in establishing organizations’ culture and actions and, consequently, generating resilience. Therefore, our historical analysis of TYPSA offers a dynamic and contextualized view of CE dimensions and its internal and external drivers,Footnote38 while also contributing to business history research by showing how CE evolves and establishes organizational behavior, bounded by the firm’s context. We also contribute to CE theory and to business history research by analyzing the case of an overlooked company type. By studying a professional services firm, our paper addresses the imbalance within the existing literature on entrepreneurship that has examined CE mainly in manufacturing and technology firms (Popowska Citation2020). This imbalance swayed findings and implications toward these types of businesses. Nevertheless, the differences between organizations between sectors in terms of goals, organizational capabilities and the sources of their competitive advantage make it inappropriate to extrapolate these findings to service organizations. Professional services firms depend very specifically on the talent and capability of their personnel. These differences emphasize the need for further research on CE in these types of company.

From a business history perspective, the study of CE has focused on Chandler´s work on the modern industrial enterprise. Our study has proposed a historical examination of CE from a completely different angle: the case of a small company in the service sector that became a family-based multinational. Our research confirms the pivotal role of organizational innovation for efficient coordination and control of resources, but not of hierarchies. At least in project-based services, it seems that flexible organizational structures work better, supported by mechanisms that enhance employees’ participation in company performance. Our study also highlights the key role of leadership within the organization to drive entrepreneurial activity forward.

While the internationalization of the Spanish enterprise has not been the primary focus of this paper, some fundamental observations can be derived from our case study. Although the international expansion of Spanish multinationals was consolidated in the 1990s (Guillén Citation2005), it was preceded, particularly among family and small and medium enterprises, by a prior exploratory period, as noted in historical scholarship (Puig and Torres Citation2009). TYPSA projects of the 1960s and 1970s are a good example, showing moreover how they encourage the company’s skillset and political capabilities to execute projects in foreign markets. It has been argued, furthermore, that it is not certain that diplomatic action accompanied the overseas expansion of Spanish firms, since their expansion was never at the forefront of the diplomatic effort (Guillén Citation2005, chapter 7). In the case of the engineering consulting sector, the activities carried out by the state-supported professional association Tecniberia, at least when in freqeuent collaboration with the diplomatic service, may shed new light on the issue. The case of TYPSA also suggests that dealing with domestic bureaucracy in the company’s early years helped to develop its political capability, enhancing skills that were applied to its first projects abroad. TYPSA’s early exposure to international markets – only a few short years after its creation – would have had a persistent consequence as well, in line with the imprinting theory (García-Canal et al. Citation2018). All this is, however, beyond the scope of this article.

The opportunities and challenges that historical contextualization poses to entrepreneurship theory deserve some final comments. Historical approaches offer the necessary longitudinal and contextual insights to understand why firms may choose to develop CE, how entrepreneurship within firms evolves over time, and how historical contexts, time and change affect those entrepreneurial processes (Jones and Wadhwani Citation2008; Wadhwani et al. Citation2020). These are important, specific gaps in CE research (Miller Citation2011), which, we claim, only historical studies have the potential to address fully. That said, enriching entrepreneurship theory through historical research also faces several challenges. These include investing the significant amount of time needed to gather, study and triangulate historical sources of data to undertake rigorous historical research, questioning existent claims and common methods, and, above all, overcoming the prevailing assumption that history only serves as the testing ground for theory to adopt a wider perspective in which ‘historical consciousness’ serves as an extensive method and approach for criticizing theories or generating new ones.

The study of CE within TYPSA has identified future avenues for research. An empirical exploration of the different dimensions of CE, with a particular emphasis on individual factors that drive CE over time, merits deeper analysis. Moreover, further research could explore how CE develops as ‘context embedding’, i.e. how firms are intertwined with contexts whose changing institutional and economic conditions shape entrepreneurial agency. Resilience, as a driver of CE, could also be explored in types of companies other than the one presented here. Although the analysis of collaborative networks as a means of strengthening innovation and entrepreneurship is beyond the scope of this article, the case of TYPSA suggests that collective action – within the state-sponsored professional association Tecniberia and by networking in specialized international forums – could have played a role in the international expansion of the Spanish engineering consulting firms – as it did, for instance, in the case of the Spanish family firms (Puig and Fernández Pérez Citation2009; San Román, Puig, and Gil-López Citation2020, 2021). Temporary agreements to execute projects, a major characteristic of this industry, are also suggested as a collaborative means of increasing firms’ capabilities (Scranton and Fridenson Citation2013), yet have been underexplored to date from a longitudinal and contextualized perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adoración Álvaro-Moya

Adoración Álvaro-Moya is an Associate Professor of Economic and Business History at CUNEF University (Madrid). Her research, awarded twice by Spanish Association of Economic Historians, has focused on the long-term effects of foreign direct investment in late developing economies and on the development of knowledge-based industries in 20th century Spain. Email: [email protected]

Águeda Gil López

Águeda Gil López is an Assistant Professor of Economic History at Complutense University of Madrid (Spain), where she obtained her PhD degree in Economics with an European mention. In 2018 she was awarded with the Complutense Extraordinary PhD Prize of Economics. Her research interests include business history, entrepreneurship and family business. She currently belongs to the research team of a competitive project funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education. E-mail: [email protected]

Elena San Román

Elena San Román is a Professor at Complutense University of Madrid (Spain) and an Associate Member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain). Her research interests are focused on business history, entrepreneurship, and family business. She is currently leading a research team of a competitive project funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education and the Spanish team of a project funded by the EU. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1. TYPSA, Annual Report. 2020, 4 and 11. TYPSA Archives.

2. Interview with Pablo Bueno Sainz, TYPSA Honorary Chairman and former President (25 April 2013).

3. Interview with Pablo Bueno Sainz (November 11, 2013); Interview with TYPSA’s former managing director of the architecture business, José Ignacio Casanova (January 16, 2014).

4. Interviews with Pablo Bueno Sainz (April 25, 2013 and November 11, 2013); “Historia del grupo TYPSA” [History of the TYPSA Group], TYPSA Archive.

5. “Informe del viaje a Kuwait de los ingenieros Bueno y Villanueva de TYPSA entre los días 29 de septiembre y 7 de octubre de 1970” [Report of the journey to Kuwait by TYPSA engineers Bueno and Villanueva from September 29 to October 7, 1970], TYPSA Archive.

6. “La experiencia práctica de un empresario español en Arabia Saudita” [The experience of a Spanish entrepreneur in Saudi Arabia], conference given by Pablo Bueno at Saudes Bank (Madrid, May 1985), TYPSA Archive; “Informe del viaje a Kuwait” [Report of the journey to Kuwait], TYPSA Archive.

7. Interview with Pablo Bueno (November 11, 2013); Interview with José Ramón González Pachón, TYPSA director for Africa and Asia (January 20, 2014).

8. Interview with Pablo Bueno Sainz (November 11, 2013); Interview with TYPSA’s former managing director of the architecture business, José Ignacio Casanova (January 16, 2014).

9. “TYPSA, Reuniones en El Paular, enero de 1974” [TYPSA Meetings at El Paular, January 1974], TYPSA Archive; “Charla de Pablo Bueno Sainz al personal de TYPSA” [Talk by Pablo Bueno to TYPSA staff], September 6, 1979, TYPSA Archive.

10. “Acuerdo compra participación de Colomina en TYPSA” [Agreement of TYPSA Management Buyout], June 22, 1976, TYPSA Archive.

11. Agreement of TYPSA Management Buyout, June 22, 1976, TYPSA Archive; Talk by Pablo Bueno to TYPSA staff 6 September 1979 TYPSA Archive; Interview with Pablo Bueno (November 11, 2013).

12. Talk by Pablo Bueno to TYPSA staff, September 6, 1976, TYPSA Archive.

13. Talk by Pablo Bueno to TYPSA staff, December 31, 1976 and November 22, 1977, TYPSA Archive.

14. “Proyecto del nuevo campus universitario” [Project of the new university campus], November 7, 1981, TYPSA Archive; Noticias de la Ingeniería y Consultoría Española, 1984, 42, June4–6, TYPSA Archive; Cauce 2000, Revista cultural, técnica y profesional de los Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos, 1992, 50, marzo-abril, 112–113, TYPSA Archive.

15. Noticias de la Ingeniería y Consultoría Española, 1981, 3, julio-agosto, 1, TYPSA Archive. Interview with Pablo Bueno (November 28, 2013).

16. Only approximately 10% of the contracts signed for providing services abroad in the early 1980s took place in this region (Álvaro-Moya Citation2009, 103–104).

17. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1981, TYPSA Archive. Industry data refers to the members of ASEINCO, the main professional association of engineering consulting firms. In 1984, TYPSA would receive the Export Award from the Madrid Chamber of Commerce and Industry, in addition to the Individual Exporter Charter a year later from the Ministry of Economy and Finance. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1985, TYPSA Archive.

18. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1980–2000, TYPSA Archive. Interview with Pablo Bueno (November 28, 2013 and April 25, 2015); Interview with Miguel Ángel Ezquerra, former Production Manager and Managing Director of TYPSA (February 14, 2014).

19. Interview with Luis Moreno, TYPSA General Director of International Coordination (January 20, 2014); Interview with José Ramón González Pachón, Director for Asia and Africa (December 16,2013); Interview with Pablo Bueno Tomás, TYPSA president (April 3, 2015); Pablo Bueno, “El reto de la ingeniería civil ante la crisis. La actividad internacional” [The challenge of civil engineering in the face of crisis. Activity abroad], TYPSA Archive; “Los ‘francotiradores’ españoles en Arabia Saudí” [The Spanish “snipers” in Saudi Arabia], El País, 17 April 1983.

20. Pablo Bueno, “Las empresas consultoras de ingeniería. El proyecto, las empresas consultoras y las relaciones contratista-consultor” [Engineering consulting. The project, the consulting firms and the contractor-consultant relationships], September 1989, TYPSA Archive.

21. Pablo Bueno, “Los consultores de ingeniería en España. Origen y evolución” [Engineering Consulting in Spain: Origins and Evolution], 4th National Congress of Civil Engineering proceedings, College of Civil, Canal and Port Engineers (Madrid, 2002), TYPSA Archive.

22. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1980 and 1990, TYPSA Archive.

23. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1986, TYPSA Archive.

24. Ministerio de Industria y Energía 1978; TYPSA, Annual Report, 1990, TYPSA Archive.

25. In 1995 TYPSA received recognition from the European Foundation of Entrepreneurs Research (Shipol, The Netherlands), and was included for more than ten consecutive years in the Europe’s 500 Honorary Listing, the 500 largest European companies recognized for sustained organic growth and job creation.

26. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1980–2000, TYPSA Archive; interviews to Pablo Bueno (November 11 and December 10, 2013); interview to Julio Grande, TYPSA deputy CEO (February 20, 2014).

27. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1990, TYPSA Archive.

28. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1982–1992, TYPSA Archive. In 1979 the reorganization of the Spanish territory into autonomous units was approved. One year later, the Basque Country and Catalonia achieved their autonomy statute. They were followed by Galicia, Andalucía, Asturias, and Cantabria in 1981. In 1995, the national territory was organized into a total of 18 autonomous regions.

29. Revista de Obras Públicas, 1984

30. Pablo Bueno, “Ingeniería civil y calidad de vida” [Civil Engieering and Life Quality], 2nd National Congress of Civil Engineering, Santander, October 1991, TYPSA Archive; Juan Gros Ester, “Nuevas oportunidades de negocio: medio ambiente” [New business opportunities: environment], Expomanagement 2007, Madrid, 23 de mayo de 2007, TYPSA Archive.

31. TYPSA, Bulletin, 38, TYPSA Archive; interview to Pedro Domingo, TYPSA corporate manager (January 9, 2014); interview with Carlos del Álamo, president of Tecnoma (February 25, 2014).

32. TYPSA, Bulletin, 38, TYPSA Archive; interview with Pedro Domingo, TYPSA corporate manager (January 9, 2014); interview with Carlos del Álamo, president of Tecnoma (February 25, 2014).

33. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1995, TYPSA Archive.

34. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1992, 11, TYPSA Archive.

35. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1980–2006, TYPSA Archive.

36. TYPSA, Annual Report, 1992, TYPSA Archive; Interviews with Pablo Bueno (April 25, November 11 and December 10, 2013); Interview with Pablo Bueno Tomás, TYPSA president (April 3, 2015).

37. International forums included the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) and the European Federation of Engineering Consultancy Associations (EFCA). In Spain, TYPSA was part of associations like Tecniberia and ASINCE (Asociación de Empresas Consultoras de Ingeniería Civil y Arquitectura).

38. See the comprehensive annotated bibliography of Business History Special Issue on Entrepreneurship and Transformations, accessed 30 May 2020

References

- Alvarez, S. A., and L. W. Busenitz. 2001. “The Entrepreneurship of Resource-based Theory.” Journal of Management 27 (6): 755–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700609.

- Álvaro-Moya, A. 2009. “Los inicios de la internacionalización de la ingeniería española, 1950-1995.” Información Comercial Española 849: 97–112.

- Álvaro-Moya, A. 2014. “The Globalization of Knowledge-Based Services: Engineering Consulting in Spain, 1953-1975.” Business History Review 88 (4): 681–707. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680514000725.

- Amatori, F. 2006. “Entrepreneurship.” Imprese e Storia 34: 233–267.

- Andrews, K. R. 1980. The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Homewood, IL: R.D. Irwin.

- Argyres, N. S., A. De Massis, N. J. Foss, F. Frattini, G. Jones, and B. S. Silverman. 2020. “History-informed Strategy Research: The Promise of History and Historical Research Methods in Advancing Strategy Scholarship.” Strategic Management Journal 41 (3): 343–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3118.

- Baden‐Fuller, C. 1995. “Strategic Innovation, Corporate Entrepreneurship and Matching Outside‐in to Inside‐out Approaches to Strategy Research.” British Journal of Management 6: S3–S16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.1995.tb00134.x.

- Baird, R., and R. St-Amand. 1995. Trust within the Organization. Otawa, CA: Public Service Commission of Canada.

- Baum, J. R., E. A. Locke, and K. G. Smith. 2001. “A Multidimensional Model of Venture Growth.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (2): 292–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/3069456.

- Baum, J. R., and S. Wally. 2003. “Strategic Decision Speed and Firm Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 24 (11): 1107–1129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.343.

- Bozeman, B., and G. Kingsley. 1998. “Risk Culture in Public and Private Organizations.” Public Administration Review 58 (2): 109–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/976358.

- Bueno, P. 1995. “El momento actual de las empresas consultoras de ingeniería civil.” Revista de Obras Públicas 3349: 7–14.

- Burgelman, R. A. 1983. “A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm.” Administrative Science Quarterly 28: 223–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2392619.

- Carreras, A., and X. Tafunell. 2021. Between Empire and Globalization: An Economic History of Modern Spain. Palgrave Studies in Economic History, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cembrero, I. 1983. “Los ‘francotiradores’ españoles en Arabia Saudí.” El País April 17

- Chandler, A. D. 1962. Strategy and Structure. Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Chandler, A. D. 1990. Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Chrisman, J., J. H. Chua, and L. P. Steier. 2011. “Resilience of Family Firms: An Introduction.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (6): 1107–1119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00493.x.

- Colli, A. E. G.-C., and M. F. Guillén. 2013. “Family Character and International Entrepreneurship: A Historical Comparison of Italian and Spanish ‘New Multinationals’.” Business History 55 (1): 119–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.687536.

- Cooper, R., and E. Martyn. 2006. “Breaking from Tradition: Market Research, Consumer Needs, and Design Futures.” Design Management Review 17 (1): 68–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2006.tb00032.x.

- Corbett, A., J. G. Covin, G. C. O’Connor, and C. L. Tucci. 2013. “Corporate Entrepreneurship: State-of-the-art Research and a Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 30 (5): 812–820. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12031.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin. 1989. “Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments.” Strategic Management Journal 10 (1): 75–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin. 1991. “A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 16 (1): 7–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879101600102.

- Cuff, R. D. 2002. “Notes for a Panel on Entrepreneurship in Business History.” Business History Review 76 (1): 123–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/4127754.

- da Silva Lopes, T., C. Lubinski, and H. J. S. Tworek. 2019. “Introduction to the Makers of Global Business.” In The Routledge Companion to the Makers of Global Business, edited by T. da Silva Lopes, C. Lubinski, and H. J. S. Tworek, 3–16. Abingdon: Routledge.

- de Fomento, M. 1998. Estudio del sector de las empresas de ingeniería civil en España. Documento de síntesis e informe técnico. Madrid: Ministerio de Fomento.

- El Economista. 2020. Ranking de Empresas del sector Servicios técnicos de ingeniería y otras actividades relacionadas con el asesoramiento técnico. Accessed 6 July 2020, https://ranking-empresas.eleconomista.es/sector-7112.html.

- Empson, L., D. Muzio, J. P. Broschak, and B. Hinings. 2015. “Researching Professional Service Firms: An Introduction and Overview.” In The Oxford Handbook of Professional Service Firms, edited by L. Empson, D. Muzio, J. P. Broschak, and B. Hinings, 1–22. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Engineering News Record. 2020. “ENR 2019 Top 225 International Design Firms.” Accessed 6 July 2020 https://www.enr.com/toplists/2019-Top-225-International-Design-Firms-1.

- European Commission. 1990. Green Paper on the Urban Environment. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- European Innovation Monitoring System. 1995. Consulting Engineering Services in Europe. Luxenburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Gándara, A. 2006. Sener, la historia de su tiempo. Bilbao: Sener.

- García-Canal, E., M. F. Guillén, P. Fernández-Pérez, and N. Puig. 2018. “Imprinting and Early Exposure to Developed International Markets: The Case of the New Multinationals.” Business Research Quarterly 21: 141–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.05.001.

- Gil-López, Á., U. Arzubiaga, E. San Román, and A. De Massis. 2020. “The Visible Hand of Corporate Entrepreneurship in State-owned Enterprises: A Longitudinal Study of the Spanish National Postal Operator.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00700-y.

- Gil-López, Á., R. Zozimo, E. San Román, and S. Jack. 2016. “At the Crossroads. Management and Business History in Entrepreneurship Research.” Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business 2 (1): 156–200.

- Guillén, M. F. 2005. The Rise of Spanish Multinationals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guillén, M. F., and E. García-Canal. 2011. The New Multinationals: Spanish Firms in a Global Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gürol, Y., and N. Atsan. 2006. “Entrepreneurial Characteristics Amongst University Students.” Education + Training 48 (1): 25–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910610645716.

- Hedner, T., A. Abouzeedan, and M. Klofsten. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Resilience.” Annals of Innovation & Entrepreneurship 2 (1): 7986. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/aie.v2i1.6002.

- Heskett, J. L., and J. P. Kotter. 1992. “Corporate Culture and Performance.” Business Review 2 (5): 83–93.

- Hitt, M. A., R. D. Ireland, D. G. Sirmon, and C. A. Trahms. 2011. “Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating Value for Individuals, Organizations, and Society.” Academy of Management Perspectives 25 (2): 57–75.