ABSTRACT

In this short essay, we draw on recent studies in history, communication, information science, and social sciences to offer a concise review of the history of social media both as a business model and as a distinctive academic data source. We start with an overview of the development of social media platforms in the past several decades and then move into a brief survey of the state of the field, examining how business, economic, and management historians engage with social media. Next, we introduce several commonly adopted analytical approaches and computational tools for processing historical social media data. Our final discussion addresses several key issues surrounding the analysis of historical social media data in business and economic history.

1. The rise of social media as business

Social media has become an essential component of people’s life in the world today. It is estimated that in 2021 Twitter received nearly 217 million daily users, and the number has continued to grow rapidly, reaching about 237.8 million by the second quarter of 2022.Footnote1 Social media platforms not only serve as the main place for ordinary people to record daily lives, but also constitute the central arena for engaging in social, political, and economic debates. For example, in about twenty days after George Floyd’s death, about 390 million tweets, about 17% of all Twitter conversations in the US during the time, were posted about Black Lives Matter.Footnote2 Through multi-forms of expression including posts, chats, images, audios, and short videos, social media plays an increasingly significant role in shaping people’s identities, emotions, and opinions.

The history of social media can be traced back to the 1980s and 1990s, when the first online social sites were launched. E-Mails, blogs, and real-time chatting started to enter people’s life. BBS (Bulletin Board System), AOL (America Online), and other online meeting forums brought about to users the new concept and experience of digital communication.Footnote3 What followed was the era of boom and bust in the history of internet and digital media: In 2002, LinkedIn was founded, then Myspace (2003), Twitter (2006), Facebook (2008), Instagram (2010), Snapchat (2011), Google+ (2012), and TikTok (2016).Footnote4 Although some platforms vanished from sight in the end, others gained dominance. Social media has yielded out some of the largest and most valued businesses in modern history. In 2012, when Facebook held its initial public offering (IPO), it became the third largest U.S. IPO ever and was valued at a staggering $104 billion.Footnote5

Facebook’s success demonstrates that social media can be a viable business model. The value of the social media business lies in the access to user data. Users not just chat with others on the platforms but also also leave trackable information about themselves as potential customers – their locations, preferences, and other valuble personal characteristics, which are often unreachable to traditional marketing companies. Social media firms soon capitalized on their wealthy user databases. Beginning 2006, Facebook put up ads for their users, followed by Twitter in 2010 and then LinkedIn, Instagram, and TikTok.Footnote6 Advertizing while providing free service to users becomes the standard business mode for social media. It is reported that in 2020 each Facebook (Meta) user can on average bring revenue of $32.03.Footnote7

2. New data, new genre, and new questions

Social media with data millions of users generated on their platforms not only give rise to giant ads companies but also offers scholars a new genre. As a new primary source, social media data allows scholars to ask new questions about human activity and social events. Social media data is the information collected from social networks and channels. It involves both traditional, macro-level statistics – date, time, location, text, images, audio, and video, etc. – and more individual metrics – likes, dislikes, retweets, follows, shares, and comments. The data gathered from individual users are effective indicators of users’ views, preferences, and networks.Footnote8

Like other types of digital data scraped from online sources, social media data shares the common characteristics of big data. First, its size and scale are unprecedentedly big; the nature of the data is dynamic (active and drafting) and nonreactive (‘a direct reflection of people’s behavior or attitudes’); it is also sometimes incomplete, difficult to access, and nonrepresentative and biased; most importantly, social media data can be algorithmically confounded, loaded with trash, spam, and useless information, and ethically and politically sensitive (Salganik Citation2018, 17–41).

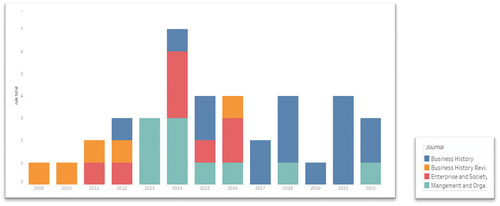

While the history of social media itself is relatively short, business historians are among the first to utilize its data. Over the past ten years, business historians have produced a robust body of scholarship with meaningful engagement with social media data. To illustrate the pattern of scholarly output, we performed a keyword search in four leading business history journals.Footnote9 The results are shown in . Between 2008 and 2022, the four journals published a total of 39 research articles containing words related to social media. The publications appeared over a period of thirteen years, excluding 2009 and 2020, and resulted in an average of 3 articles per year. There is no surprise that the degree of business historians’ engagement with social media varies. In some articles, social media-related terms are simply mentioned in the abstract or the main text, while other articles deal with social media data or topics in depth. The social-media-related publication peaked in 2014 and in recent years starts to stabilize and concentrate on selected journals.

Figure 1. The number of articles containing social media-related keywords published in major business history journals in recent years.

Social media and the hashtag movements they undergirded have accelerated the digitalization and transformation of our life, exposing scholars to new questions. According to Sloan and Quan-Haase (Citation2017), there are at least two primary groups of questions that scholars ask through an analysis of social media data. The first set concerns social media use itself and often originates from ‘from individuals’, organizations’, and governments’ interaction and engagement on these information and social spaces.’ In this case, scholars tend to focus on social media activity and explore its related social, economic, health and mental, and organizational impacts. The goal of these types of questions is to understand the logic and motivation of social media behaviors and then propose suggestions for adjustment. The second group of new questions is related to understanding social phenomena, examining questions, issues, and social problems that are otherwise inaccessible for comprehensive analysis through traditional research approaches. In the next session we offer several examples where scholars utilize multiple data-powered techniques to uncover complexities in social movements and events and reveal the delicate mechanisms underlying dynamic social change.

3. Examples of social media data analysis

To analyze social media data and understand the underlying social problems, scholars have developed a series of computational analytical methodologies. Ferguson-Cradler (Citation2021) provides a summary of computational text analysis in the context of business and economic history. One of the most fundamental methods is to count and classify words. This method is based on the fact that text constitutes the principal form of the social media data source. By counting the words, researchers are able to detect the frequency of the topics or events of interest, therefore establishing a broader event chronology or drawing a big picture of the context. And, by comparing texts to a pre-compiled list of terms, researchers can quickly go through a large corpus of texts and develop a basic understanding of their similarity with the benchmark (the pre-compiled list of words). This method is often used in sentiment detection, where scholars are interested in knowing what emotions the social media users try to express in the texts.

Another situation where the comparison and counting of words can be adopted is the analysis of discourse or narratives. When scholars attempt to depict the rise and fall of certain styles over a long time period, the focus of analysis is often on specific verbs or nouns. The frequency of the appearance of a particular term serves as the indicator of a discourse or narrative’s prevalence. The comparison of course can be expanded into full documents. When reading and comparing documents, researchers use standard metrics such as the term frequency-inverse document frequency scores to make the evaluations. The scores are designed to evaluate both term frequency and its unusualness in the entire text (Ferguson-Cradler Citation2021, 11).

In analyzing social media data texts, business historians have also experimented with more advanced machine learning methods such as topic modeling and word embedding. Topic modeling is a text-mining method that analyzes the semantic structure of a given text to derive its basic meanings or ‘topics.’ Word embedding is a method that tends to understand and compare the meaning of texts across contexts. This method assigns similar values to words that appear in similar contexts. The value assigned is not a single number but a vector of numbers, indicating similarity or distance along different directions. Word embedding denotes words of similar meanings in directions that can be analyzed by various tools. According to Ferguson-Cradler (Citation2021), the two most popular algorithms for estimating word embeddings are word2vec and GloVe.

One of the most important but often overlooked issues in utilizing social media data is the tactics of interpretation. Digital data, like paper-based archival sources, is often difficult to comprehend, especially given the massive amounts of non-useful or irrelevant trivial information collected during the scraping process. The real information researchers are in search of can be embedded in the corpus of digital data. Tong et al. (Citation2022) provide an interesting example of interpreting the meaning of historical events through large social media datasets. The researchers focus on the two major social movements in 2020–2021, Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Stop Asian Hate (SAH), and collect more than one million tweets with the hashtags #blacklivesmatter and #stopasianhate. By constructing this large digital social media database, the researchers delve into the concrete topics and issues being discussed or covered with the hashtags and explore the two movements’ connections with other social events that happened offline. They also compare the differences and similarities in the topics of the two social movements.

Through performing modeled text analysis, the researchers find that both groups of tweets discuss a variety of influential topics in depth and address serious judicial and social concerns. For example, both movements denounce racism, encourage social participation, and express emotional responses. Each movement nonetheless contains distinctive subtopics. For example, the researchers find that the BML’s main concerns lie in the public’s discontent with police brutality while the SAH revolves around COVID-19's negative imaging of Asian communities. The researchers also find a concerted pattern between the social movements on media platforms and the ones offline, as the volume of tweets corresponds to the activities of both movements on the ground (Tong et al. Citation2022).

Despite various analytical strategies and computerized tools to collect big data and construct an accurate characterization of the social media events, misinformation presents a major challenge to social media data analytics. Unverified and sometimes purposefully fabricated information, or even fake news, is rampant on social media platforms. Pasquetto, Swire-Thompson, and Amazeen (Citation2020) identify a couple of areas where scholars can collaborate to combat misinformation. These areas include improved data measurement metrics and research design, understanding who engages with misinformation and why they do so, better and richer datasets with increased validity, online community actions and campaigns on enhancing ethical standards and actions, and active interventions.

4. Discussions

The rise of social media as a new source creates both opportunities and challenges for business historians. It accelerates the application of data-oriented quantitative and computational methods in the fields of economic and business history (Eloranta, Nevalainen, and Ojala Citation2020; Bashir Citation2022). Digital humanities specialists have also started to integrate social media into their research agenda. Warwick, Terras, and Nyhan (Citation2012) offer a useful instructional book that summarizes common strategies in digital humanities. This book in particular discusses how to crowdsource social media information and connect it to digital humanities projects. They also showcase several examples of using social media sites and applications to enhance engagement with conference and museum audiences.

Also, social media can be a valuable teaching tool. Giacomin and Lubinski (Citation2020) offer a detailed instructional note on using Instagram in the classroom. This essay overviews the useful functionalities of Instagram in teaching and demonstrates the ways to integrate Instagram into different course assignments, projects, and modules. The authors show that the appropriate adoption of social media can help create a joyful hybrid classroom attractive to the younger generation. Bennett (Citation2019) is an innovative dissertation that analyzes the impact of social media on history education and students’ responses. The work itself adopts a data-based integrated format that contains links, codes, and datasets. Based on a comprehensive analysis of multiple sources, the author is able to build up a new analytical framework to observe and evaluate students’ class participation and performance under the condition of social media materials.

Finally, the information age we are living in has a historical path leading to where it is presently. While we are predicting the future, it is helpful to ask how such a relationship comes to being and what forces have shaped its course. Blair et al. (Citation2021, 238–58) explain how communication channels and computer technologies intertwined to redefine the idea of information and how its data could be used. Today, computers with much stronger supercomputing power have brought humans into the era of big data. The new era requires unconventional methodologies and approaches to understand its meanings, significance, and implications. Social media will be an essential part of our toolbox to unlock the mystery and excitement of a digital future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/970920/monetizable-daily-active-twitter-users-worldwide accessed 15 December 2022.

2. Thorbecke, Catherine. 2021. ‘Twitter Turns 15: A Look Back at How the Platform Changed Our Lives.’ ABC News. 11 March 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Business/twitter-turns-15-back-platform-changed-lives/story?id=75804702.

3. (Shah Citation2016). ‘The History of Social Media.’ Digital Trends, 14 May 2016. https://www.digitaltrends.com/computing/the-history-of-social-networking/

4. Source: ‘The Evolution of Social Media: How Did It Begin and Where Could It Go Next?’ 2020. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/evolution-social-media/ accessed 30 January 2023.

6. Source: ‘The Evolution of Social Media: How Did It Begin and Where Could It Go Next?’ 2020. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/evolution-social-media/ accessed 30 January 2023.

7. McFarlane, Greg. ‘How Facebook (Meta), Twitter, Social Media Make Money From You,’ Investopedia, 2 December 2022.

9. The four journals are Business History, Business History Review, Enterprise and Society, and Management and Organizational History. Our search follows two different rules. The first is to use ‘social media’ as the key search identifier to locate articles published in the four journals that contain the identifier. The second rule is to replace social media with a different set of identifiers, or search iterms. We searched for selected social media platforms, such as TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, but excluded the term ‘social media.’ The results reported in are the outcomes produced by two search rules combined. For more details on how we performed the search and what articles are located, see the link (we will produce a detailed online appendix before next review).

References

- Bashir, S. (2022). “Composing History for the Web: Digital Reformulation of Narrative, Evidence, and Context.” History and Theory. November hith. 12275. 10.1111/hith.12275.

- Bennett, H. L. 2019. “Hashtag History: Historical Thinking & Social Media in an Undergraduate Classroom.” In ProQuest LLC. Drew University.

- Blair, Ann, Paul Duguid, Anja-Silvia Goeing, and Anthony Grafton, eds. 2021. Information: A Historical Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Eloranta, J., P. Nevalainen, and J. Ojala. 2020. “Towards Big Data: Digitising Economic and Business History.” In Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches within the New Digital History, edited by M. Fridlund, M. Oiva, and P. Paju, 45–67. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. doi:10.33134/HUP-5-3.

- “The Evolution of Social Media: How Did It Begin and Where Could It Go Next?” 2020. Maryville Online (blog). 28 May 2020. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/evolution-social-media/

- Ferguson-Cradler, G. 2021. “Narrative and Computational Text Analysis in Business and Economic History.” Scandinavian Economic History Review: 1–25. doi:10.1080/03585522.2021.1984299.

- Giacomin, V., and C. Lubinski. 2020. “Technical Note: Instagram for Educators.” Greif Center for Entrep. Studies-USC Marshall. https://store.hbr.org/product/technical-note-instagram-for-educators/SCG864

- “How Facebook (Meta), “Twitter, Social Media Make Money From You.” Investopedia. Accessed 30 January 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/stock-analysis/032114/how-facebook-twitter-social-media-make-money-you-twtr-lnkd-fb-goog.aspx

- Pasquetto, I., B. Swire-Thompson, and M. A. Amazeen. 2020.“Tackling Misinformation: What Researchers Could Do with Social Media Data.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, December. doi:10.37016/mr-2020-49.

- Salganik, M. J. 2018. Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Shah, S. 2016. “The History of Social Media.” Digital Trends. 14 May 2016. https://www.digitaltrends.com/computing/the-history-of-social-networking/

- Sloan, L., and A. Quan-Haase, eds. 2017. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. London: SAGE reference.

- Tong, X., L. Yixuan, L. Jiayi, R. Bei, and L. Zhang. 2022. “What are People Talking about in #backlivesmatter and #stopasianhate? Exploring and Categorizing Twitter Topics Emerged in Online Social Movements through the Latent Dirichlet Allocation Model.” In Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 723–738. AIES ’22. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/3514094.3534202.

- Warwick, C., M. Terras, and J. Nyhan, eds. 2012. “Digital Humanities in Practice.” Facet. https://doi.org/10.29085/9781856049054