ABSTRACT

Material culture can offer profitable primary sources for business historians, as several scholars have shown. This essay builds from a workshop held during the 2022 Business History Conference Mid-Year meeting, intended to challenge participants to rethink traditional sources through material culture methodologies. Broadly, the workshop asked participants to consider how material culture methods might amplify the use of ‘traditional’ business history sources (such as account books and advertisements). Here, the author offers a methodological framework for analyzing material culture in order to illustrate the utility of an object-centered approach when writing business history.

Introduction

When we study markets and production, it can be easy to overlook the objects that circulated through distribution channels, materializing the laborer’s toils for the end consumer, whose desires and fetishizations capitalists sought to harness. With so many different actors and processes at work in the production, distribution, and consumption cycle, the objects – seemingly inanimate beings without any agency – may seem to be mere props in a broader story. But I would like to suggest that returning focus to the material objects can be a very fruitful task for business historians. Material culture encompasses a wide range of things, and for historians, the phrase typically refers to the objects and environments made and/or altered by human beings. Such objects might include technological implements, housewares, luxury goods, tools, furniture, jewelry, clothing and textiles, objects intended for entertainment or play, architecture and the built environment, and even, for some scholars, the landscape itself. The interdisciplinary field of material culture studies is bound together by an emphasis on using the materials ‘to explore and understand the invisible systems of meaning that humans share – culture’ (Wajda and Sheumaker Citation2007, 4). Thus, beyond simple illustrations that might provide a ‘window’ to the past, material goods, like other primary sources, are artifacts of the historical interactions, creative decisions, and strategic thinking of the people who crafted them and the individuals who consumed them. In short, analyzing objects – especially in focusing on their materiality – can help historians get beyond what these cultural relics show, and find out what they did.

Materialism and materiality have varied constructions in the historical profession. For many business historians, the terms may call to mind Marxian examinations of the material constraints – economic conditions such as class and income – that characterized much of the literature on business and economic history in the second half of the twentieth century. Recently, a ‘new materialism’ has influenced business historians, pointing to the ways in which the social and economic spheres are formed through contingent interactions rather than structural determinants (Lipartito Citation2016). Incorporating cultural theories of network interaction, such as those posed by Bruno Latour (Citation2005), business historians have uncovered new ways of understanding economic developments, the flow of capital through markets, and the shifting meanings of commodities. In particular, Latour’s Actor-network theory (ANT) concentrates on the myriad interactions that constitute spheres of influence within past societies and cultures. In such networks, Latour asserts that even ‘nonhuman’ objects can have agency, and ought to be given equal weight, in historical analyses, to other human actors in the network (2005).

It is in this last point that Latour’s actor-network theory intersects with what material culture scholars have long understood as the central purpose of their field: to elucidate cultural interactions by focusing on objects. For material culture scholars, ‘materiality’ typically refers to an object’s physical properties: the raw materials used to make it, the design elements and symbolisms that might be visible, the object’s use and function, and generally, the tactile properties that generate its status as an artifact (Montgomery Citation1961). To understand culture – including the various interactions and ideas that circulate among, and constitute relationships between, different groups of people – we can look to the artifacts that they have left behind (Prown Citation1982). In other words, material culture studies promises to expand our understandings of the past by focusing on the relationships between objects and people (Schlereth Citation1999; Wajda and Sheumaker Citation2007). This is a lesson that material culture scholars have long emphasized in attempting to parse out culture itself, but one which business historians have increasingly embraced in the past two decades. While firms, distributors, and consumers each play a role in determining the shape and scope of a particular commodity market, it is also important to consider the role of the commodity itself – including its material (i.e., physical) properties, design, packaging, and even merchandising – in reciprocating influence upon the other historical actors in the network. As Pamela Laird (Citation1998) and others have argued, business and economic developments are very much embedded in the cultures of their time, and the material relics of such cultures can yield fruitful insights for business history.

For example, seasonal changes in the availability of raw materials, such as mahogany woods, could force artisanal and ultimately consumer adaptation over time. In her interdisciplinary study of the colonial mahogany trade in the Atlantic world, Jennifer Anderson (Citation2012) reconstructs the scope and shape of the market in mahogany, an increasingly rare wood indigenous only to the Caribbean and parts of Central America. Anderson connects the ecological history of this tropical commodity to the history of capitalism in the Atlantic world, noting that different growing patterns, water supplies, and soils shaped the changing appearance of the wood over time and across different regions. Such factors would, in turn, shape consumer preferences as individuals learned to discern between different types of mahoganies in the eighteenth century. Likewise, artisans adjusted their orders of raw materials from different sources, to accommodate changing consumer tastes (Anderson Citation2012, 4). Tracing the force of unpredictable consumer preferences up the supply chain, Anderson elucidates the networks of merchants, cabinetmakers, and other craftsmen who fashioned new pieces for consumers; the white Europeans who brokered, commissioned, and distributed mahogany to colonial artisans; and finally, the indigenous and enslaved persons who played an important role in identifying and harvesting forests. Cultural factors prompted which trees were harvested (as well as how, where, and by whom), but harvesting was also contingent upon changing social, political, economic, and environmental conditions (Anderson Citation2012, 10–13). Scrutinizing the changing appearance and physical properties of mahogany furnishings in the eighteenth century helped Anderson uncover the various inner workings of the complex market for mahogany, and better understand why harvesting and production patterns shifted, swelled, and diminished over time.

Taking an object-centered approach requires a preoccupation with ‘looking’ or ‘close reading,’ in a way that requires the researcher to linger upon the details in order to discern broader meanings and clues that point toward new research pathways. This method is complementary to both visual and material culture, in my view, because analyzing both objects and images begins with observation and looking. Fully explaining these connections lies somewhat outside the scope of this article, however, and thus here I will focus only on material culture methodologies and their implications for business history. Some readers of Management & Organizational History will, no doubt, already be keenly familiar with these texts and methods. For others, I hope what follows will illustrate a fraction of the broad possibilities in applying material culture methodologies to the study of markets, firms, and industries, which may further deepen our historical understandings of production and consumption.

Many scholars begin by placing the object at the center of analysis, using it as an organizing principle to help illuminate economic discussions about labor, production, distribution channels, and consumption. For example, Pietra Rivoli’s focus on an ordinary cotton t-shirt facilitates her deep dive into the history of cotton production, into political economy and governmental regulation, and into the global consequences of American dominance in the cotton trade (Rivoli Citation2014). Likewise, in her microhistory of a 1743 portrait of a Philadelphia merchant’s wife, Anishanslin (Citation2016) uses the object to explore the various market interactions between silk weavers in England, intermediaries along the distribution chain (such as shipping channels, importers, and seamstresses in the colonies), consumers, and colonial portraitists. Business historians have also applied material culture analysis to rethink more traditional sources and topics, such as credit valuations and relationships (Martin Citation2010), organizational strategies (Hahn Citation2011), advertisements (Black Citation2017), branding tactics (Barnes and Newton Citation2022b), paper money and alternate currencies (Greenberg Citation2020; Barnes and Newton Citation2022a; Edwards Citation2022), and the economic dimension of reform movements (Goddu Citation2020). A key thread that weaves through many of these works is the acknowledgment of the interconnected nature of culture and markets, including an understanding that culture drives markets, and markets, in turn, can shape cultural developments. Focusing on the material objects – the products – prompts historians to question how and why the products changed at variable rates over time, and how and why certain firms diverged from what otherwise might have been industry standards in production. This, in turn, enables us to uncover the organizational strategies (such as technological investment or unique production processes) that facilitated better market competition for certain firms.

How might one proceed in applying material culture analysis to their work in business history? Like any primary source, analyzing an object requires careful consideration of the source’s content, language, meaning, and context in order to reach broader historical understanding. But reading images and objects is not the same as interpreting texts or numbers. Any good historian would probably advise you not to take such documents at face value, and with objects, historians need to be just as critical. It can be useful to think of the object as possessing a different language in and of itself; one needs to find the right dictionary to be able to understand the object’s properties, and what it is trying to say. While it may seem simplistic, the best glossary for decoding material culture comes from a deep understanding of relevant contexts. As in any historical research project, it will be helpful to have a good grasp of the various economic, political, intellectual, social, and cultural frameworks of the time, which will help the researcher identify and interpret underlying references, symbolism, and other factors shaping the object’s production and consumption.

Additionally, material culture scholars generally acquire an understanding of the evolving styles and aesthetics that shaped artistic, artisanal, and/or mass production, both in the period at hand, and in the broader sequence of developments within which the period fits. For example, if one is studying American furniture created in the Arts and Crafts style (c.1900), it is helpful to know that craftsmen and designers working in this movement largely rejected the ornament and over-the-top styles of the Gilded Age. This may seem like an obvious point, but if one has never researched visual or material culture before, it can be useful to begin with broad overviews of art, architecture, and design for the specific period/region, to get a sense of the different styles one might encounter. Studying these developments will help one identify stylistic convergence or divergences in the object, and will serve as a useful reference for follow-up research. As an interdisciplinary field, material culture studies draws heavily from the disciplines of art history and anthropology, but it is important to note that these disciplinary relationships (and thus methodological approaches) can differ regionally and internationally: Scholarship on material culture may look different in the United States, as opposed to that in Europe, Asia, or even the UK. While it may feel elementary, speaking to knowledgeable colleagues may also help yield reading recommendations, as they can orient the business historian to key trends and methodologies in the literature – both universal, and particular to one’s global region.

Finally, before beginning analysis, one should consider the driving questions behind the project, and how they relate to this particular source material. What are you hoping to learn from this object? Do you want to know about its production, or are you more interested in learning about consumption or reception? The following questions are intended to spark the researcher’s conversation with the literature and with the object itself, aiming to help researchers decode the object’s language, in order to better understand what it is trying to say to us and what it did in the past.

Consider the object’s physical properties and content

Material culture specialists generally begin their excavations by surveying the object, looking for visual (and perhaps textual) clues (Fleming Citation1982; Prown Citation1982). Resist the urge to come to interpretive conclusions right away; allow your eyes to move slowly around the object as you consider its properties. Try to identify any key features or focal points on the object. What do you notice about these? Different types of material culture will have different content areas that will require further examination. Some objects, such as ceramics, furniture, and textiles, may include representational images and designs. At different points in time, such objects might have been loaded with ornament – as in the eighteenth-century Rococo style in Europe, or the late-nineteenth century Gilded Age in the US – or, conversely, the objects might feature simplified aesthetics and sleek or minimalist designs – as in the mid-twentieth century ‘modern’ style. Recognizing these elements, and any deviations from what one might otherwise expect, can help the historian situate the production of the item in context and understand why such deviations in style might have occurred.

Consider any ornaments and/or images that may be present, and their content. Can you identify any important symbolism, hierarchies, or other elements that might indicate significance? If there are figures present, consider how the producer has represented the figures, their clothes, their features, and/or emotions. What can you learn from these details? Next, consider the environment or background surrounding the primary figures or focal point. What details are there? How are they rendered? Consider design elements, such as lighting, perspective, proportion, color, balance, and form. How does the artist use shape, size, or balance to privilege (or hide) certain elements? How might negative or blank space help to foreground certain elements? How might such compositional elements provoke a certain response, or emotion in the viewer? Considering these basic visual principles can help historians understand how the producer might be using particular design elements, content, and symbolism to direct the viewer’s attention in one way or another, or to provoke a certain reaction.

For example, in his examination of the decorative arts in the colonial United States, David Jaffee discovered a divergence in the styles that appeared in the rural areas surrounding America’s budding cities of Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. His close reading of domestically-produced goods between 1790 and 1815 shows that domestic markets emerged apart from imperial ones as colonial artisans sought to satisfy divergent local tastes (Jaffee Citation2012). Analyzing clocks, chairs, and portraiture, Jaffee finds that rural artisans produced simpler versions that were derivative of British styles, yet still distinct. Reducing ornamentations allowed many artisans in the hinterlands to produce these goods with greater efficiency, in a move that prefigured the mass production techniques that would emerge later in the nineteenth century (Jaffee Citation2012, 48). From this object-centered analysis, Jaffee is thus able to trace the development of new domestic markets for artisanal goods in the US, explaining the ways in which print culture and itinerant peddlers attempted to disburse urban styles from the cities outward with varying degrees of success, and the adaptations that rural artisans made to meet their customers’ local tastes and preferences.

Like Jaffee, other historians have also used material culture to rethink the common theme of Anglicanization in the eighteenth-century American colonies (Alexander Citation2018; Cooke Citation2019). Questioning the cosmopolitan motifs appearing on Boston-made material goods after 1700, Edward Cooke (Citation2019) attributes deviations from typical British styles to a system of cultural exchange that characterized Boston’s position as an entrepot in the British empire. Sailors and traders brought objects from around the world to the port, exposing Bostonians to global styles that would subsequently influence Boston-made goods (Cooke Citation2019). Like Anderson (Citation2012), Cooke finds that the availability of raw materials and finished goods circulating through the port of Boston – especially those originating outside the British empire – had a profound influence on the production and sale of durable goods within Boston. Yet while consumer tastes might influence the demand for raw materials, as Anderson showed, Cooke demonstrates how such tastes might also be shaped by evolving global trade patterns and markets in the eighteenth century. In these ways, material culture analysis can help elucidate the reciprocal relationship between objects and markets.

Research production

The next step in analyzing an object is to consider the factors of its production. Who produced this object; when; where; and how? What materials were used? What do you know about the process required to create this item? Consider the producer’s relationship to the raw materials: would it have been easy or difficult to acquire and work with these? Can you draw any significance from this information? Why was the item produced (i.e., decorative purposes, functional use, educational purposes, entertainment, etc.)? Who do you think was the intended audience for this object? What do you think the producer might have been trying to achieve, in reaching that audience? How did the item reach its audience? What distribution channels might it have gone through, and how might other historical actors have influenced or interacted with the item along the way?

Understanding changes in the products and their appearance has enabled historians to uncover the organizational strategies that facilitated better market competition for certain firms. In her influential study of twentieth-century ceramics and glassware manufacturers, Blaszczyk (Citation2000) traces the firms’ shifting product designs and uncovers the important role of ‘fashion intermediaries’ in determining production cycles. Channeling information about consumer preferences to the manufacturers, these intermediaries enabled firms to deploy flexible, batch-production manufacturing processes that enabled them to respond more quickly and efficiently to changes in consumer tastes. In many ways then, a focus on material goods shows how consumer preferences could also shape manufacturing strategies, which in turn allowed firms like Corning to be more competitive (Blaszczyk Citation2000). As Blaszczyk (Citation2000), Anderson (Citation2012), and Cooke (Citation2019) suggest, production and consumption are always intertwined: Producers and distribution chains respond to consumer spending habits and fluctuating tastes, but producers and supply chains also shaped tastes when introducing new products to the market. A keen understanding of the material properties of the goods themselves helped these scholars to illuminate these interconnections between culture and economics, and the network interactions behind the objects’ production and consumption (Yaneva Citation2009).

Consider consumption and reception

Reception is one of the most difficult things to uncover, because direct reflections – telling us what historical actors intended, or how they understood and responded to particular images and objects – are incredibly rare in the archive. Without such sources, how might historians piece together the audience’s response? Some of the most interesting attempts at doing this try to triangulate producers’ intent and consumer reception through careful and interdisciplinary consideration of supplementary materials, such as design trends amongst printers and advertisers (Laird Citation1998; Jury Citation2012; Greenhill Citation2017), shifting market demands for certain goods (Iskin Citation2014; Woloson Citation2020), and varying exchange values based on users’ activities (Martin Citation2010; Greenberg Citation2020).

Sometimes reception can be elucidated by asking the right questions of the object and of supplementary sources. Consider, for example, how the material properties may have affected the item’s use, function, and the relative stability or fragility of the item. How might these properties have changed the object’s value in the eyes of various historical actors? In their explorations of banknotes in nineteenth-century America, Stephen Mihm (Citation2007) and Joshua Greenberg (Citation2020) demonstrate that the notes’ materiality had a direct influence on individual understandings of the notes’ authenticity and exchange value. In the absence of a standardized currency in the US before 1860, banknotes were produced regionally and locally, leading to a highly confusing marketplace where value fluctuated constantly and counterfeit notes circulated widely. The quality of the note’s engravings, as well as the inclusion of the bank managers’ signatures, became important signifiers that figured into individual assessments and valuations of the notes (Mihm Citation2007, 221). Moreover, the images and iconographies depicted on the notes’ faces show how cultural symbolism helped configure and symbolize the notes’ trustworthiness. Popular iconographies of Greco-Roman goddesses associated with republicanism, truth, justice, and industry were common tropes on banknotes, as they were on other ephemera at the time (Greenberg Citation2020). As Greenberg points out, users’ understandings of the notes’ visual and material factors (in the images included, or the wear and tear of the note itself) directly influenced exchange value: Note values declined as they moved farther away from their points of origin, where individuals were less likely to recognize the names and signatures supposedly authenticating the notes. Greenberg thus demonstrates that, when it came to banknotes, economic exchange value was contingent upon the object, including its material properties, its appearance, its bearer, and the subjective interpretations of the many users who handled the notes. This point is reinforced by Mihm, who shows that the more counterfeiting became a problem in the US, the more printers and others sought ways to manipulate the material properties of banknotes to keep them secure and concretize authenticity (Citation2007: 299).

When considering reception, it is also important to question how the object’s audiences and functions may have changed over time. Did the actual audience differ from the intended audience for this object? How, and why? Were there secondary audiences, or subsequent functions, that developed apart from the object’s intended function? How might those later audiences have used and/or responded to the object? What does that tell us about the object’s mutability, consumer adaptations, and permutations of the object after the point of sale or acquisition? For example, in researching the history of trademark regulation in the United States, I noted that the New York City Junk Dealers’ Association objected to the expansion of the federal trademark statute in 1876, because the proposed bill criminalized the possession of used packaging containing trademarked labels (Rosen Citation2012, 845). These ‘junk dealers’ formed a common link in the distribution and supply chain in the nineteenth century, facilitating the recycling of packaging materials such as bottles, boxes, and other ephemera, among other roles. Collecting used product boxes and glass bottles from the accumulating trash heaps in American cities, junk dealers participated in an important secondhand economy (Gamble Citation2015, 39). For example, such dealers often sold boxes of used patent medicine bottles back to the manufacturer for reuse, or, in some cases, they sold them to other manufacturers who recycled the bottles for their own preparations. As American manufacturing expanded through the middle decades of the nineteenth century, junk dealers would become integral to the trade in counterfeit goods, especially patent medicines. A particular counterfeiter might, for example, pay a premium price for a lot of genuine bottles for Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. Pinkham’s was one of the more popular patent medicines by the 1890s, and one of the most widely copied (Engelman Citation2003, 80–90). Following this chain of research, the reference to the junk dealers’ association in the legal record allowed me to examine how the material goods circulated beyond the initial point of purchase and consumption. In this subsequent trade, secondary consumers – such as junk dealers and the manufacturers of counterfeit wares – used labels and product packaging in ways that deviated from their original intended purpose. The material goods took on a new life through this secondhand economy, and their material properties – including bottle shapes, label designs, and authenticity – helped determine their exchange value and subsequent use in this alternate market.

This phenomenon of use and reuse is prominent in the literature on advertising, particularly among scholars who investigate ephemera that circulated primarily between 1870 and 1900. When printers first issued trade cards as an advertising medium, many middle-class individuals had already been primed to love the colorful, hand-held objects because of an ongoing cultural fascination with chromolithography and album-making, especially in the US and Europe. Individuals tended to collect these cards in scrapbooks alongside other ephemera, using the found objects to craft imaginative narratives, to memorialize personal experiences, and to mark important occasions and/or relationships (Black Citation2017). Several scholars have adapted lessons from the history of readership to consider the materiality of these advertisements, in order to better understand how and why trade cards were used in scrapbooks, and what the cards may have meant to individuals (i.e., Garvey Citation1996; Tucker et al. Citation2006).

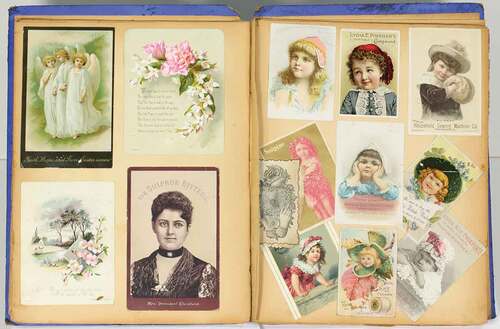

For example, Fanny Keene’s scrapbook dating to the 1880s includes a range of advertising trade cards and other ephemera (). Keene compiled this book from materials gathered throughout New England. She arranged the materials in a variety of ways, indicating attention to aesthetic form and design and categorizing the materials according to content or product advertised. Like other album-makers, Keene mixed commercial trade cards for products such as sewing machines, patent medicines, and soaps alongside noncommercial materials, including a portrait of First Lady of the United States, Frances Cleveland; holiday greeting cards; and religious cards. Keene’s disregard for the categoric differences between these media suggests that she largely overlooked the original commercial function of these cards when using them to craft her scrapbook. Children, women, flowers, and other sentimental topics were the dominant theme on trade cards during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and Keene has shown her preference for the pictorial content over the commercial messages, through the arrangement on the page. On the right-hand page, we can see that she has pasted several cards in an overlapping fashion, obscuring the full title for Horsford’s Acid Phosphate in the black and white card at the lower right, as well as that of HUB Ranges (a stove manufacturer) on the card closest to the binding at the lower left. The HUB card has been torn across its lower half to make it fit on the page, or perhaps to crop out the name of a local sales representative or merchant (which the latter often added to trade cards as the medium became increasingly popular after 1880) (Black Citation2017).

Figure 1. Fanny Keene, scrapbook (c.1885–1889), p14–15. Library company of Philadelphia Digital Collections (P.9763). Online at https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A120293 (accessed 7 February 2023).

In this and thousands of other scrapbooks crafted in the US, trade cards became meaningful raw materials to craft narrative stories, to memorialize and celebrate life events, and to fantasize about the future. Like many other album-makers, Fanny Keene showed her disregard for the commercial information contained on the front (and on the back) of the card by manipulating it with scissors and paste to fit in her scrapbook. Cropping out and obscuring these commercial reminders, Keene arranged the images to privilege the chubby and rosy-cheeked faces of the young girls on the cards. Considering hers alongside other scrapbooks compiled in the period would allow the researcher to find patterns – not only of the content and images selected for advertisements during this period, but also of the ways in which individuals interacted with advertising ephemera after the point of sale. Further analyzing these arrangements, we can extrapolate out the meanings that individuals may have attributed to trade card advertisements, considering, for example, the ways in which producers leveraged sentimental ideals – such as children – to sell more goods, while likewise, consumers appropriated advertisements such as these to express their own personal sentiments for themselves, and toward others (Black Citation2017). Thus, adapting the methodologies of material culture studies to study the business history of advertising – considering trade cards’ materiality and use, rather than just their content – provides a mode of uncovering consumer reception.

Compare and follow-up

As this example suggests, it is important to consider how particular objects compare with other extant examples from the period, both within similar product lines and object categories, but also among other items made from the same materials, for the same function, or by the same producer. Look for patterns and trends in terms of the materials used, content represented, and production processes employed. Consider what else you might need to know, and how you might find it. Will you need to research more about consumers? What potential sources could you find? How does your object fit within the existing literature? How does it relate to the relevant contexts of the period? How might you explain any divergences, or anomalies in the design, content, function, or audience? Finally, formulate your interpretation. What have you learned about markets, producers, or consumers by looking and analyzing the object? What does the item tell us about firms and organizations?

To return to the trade cards depicted in , analyzing the use of the cards in scrapbooks demonstrates how the cards’ materiality – their physical properties – were as important as the commercial messages from producers. After the cards had passed the initial point of acquisition, scrapbook-makers molded the medium to fit their own personal needs. Printers knew and understood how meaningful trade cards would be to the public; they purposefully designed these advertising cards in order to capitalize upon the public’s fascination with colorful pictures. Moreover, advertisers showed flexibility in selecting images and themes that would best speak to viewers, and gradually, they found ways to assert the primacy of their commercial messages while still crafting visually appealing advertisements. All of this becomes clear when reading and rereading the material objects themselves. Decoding the reception of trade cards in scrapbooks thus reveals the ways in which the advertising industry adapted to consumer preferences after 1870 (Black Citation2023).

Conclusion

As these brief examples suggest, placing the object at the center of historical analysis offers broad possibilities for better understanding economic actors and processes. Over the past two decades, more and more business historians have embraced the methodologies of material culture analysis, offering exciting new pathways for reimagining our interpretations of markets, firms, and organizational strategies. In particular, recent works have opened up multiple avenues for research, exploring technological and organizational innovations prompted by the challenging properties of raw materials (Styles Citation2017; Hisano Citation2019); the complicated transition from state-sponsored to capitalistic regimes in the early modern period (Marchand Citation2020); material goods as alternate currencies (Edwards Citation2022); fundraising and organizational tactics amongst reform groups (Goddu Citation2020); and iconographic and semiotic readings of commercial imagery, internal business communications, and trademarks (Barnes and Newton Citation2022b; Black Citation2023). Examining the material qualities of commodities affords ample possibilities for deepening our understandings of economic forces and business practices. While often challenging, applying material culture analysis can be deeply rewarding for writing business history.

Acknowledgments

For their help in preparing and encouraging this essay, the author wishes to thank Marina Moskowitz, Dan Wadhwani, and the peer-reviewers assigned by the journal. Special thanks are also due to the H-Material Culture community, which has stimulated the author’s thinking and writing over the past decade.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jennifer M. Black

Jennifer M. Black is Associate Professor of History and Government at Misericordia University. She holds a PhD in American History and Visual Studies from the University of Southern California. Her research examines ways in which people interact with images and objects, and the power of visual and material culture to influence trends in politics, the law, and society. Black’s forthcoming book, Branding Trust: Advertising and Trademarks in the US, traces the uneven development of American branding practices and trademark regulation through the nineteenth century (Black Citation2023).

References

- Alexander, K. S. 2018. Treasures Afoot: Shoe Stories from the Georgian Era. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Anderson, J. L. 2012. Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Anishanslin, Z. 2016. Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Barnes, V., and L. Newton. 2022a. “Corporate Identity, Company Law and Currency: A Survey of Community Images on English Bank Notes.” Management & Organizational History 17 (1–2): 43–75. doi:10.1080/17449359.2022.2078371.

- Barnes, V., and L. Newton. 2022b. “Women, Uniforms and Brand Identity in Barclays Bank.” Business History 64 (4): 801–830. doi:10.1080/00076791.2020.1791823.

- Black, J. M. 2017. “Exchange Cards: Advertising, Album Making, and the Commodification of Sentiment in the Gilded Age.” Winterthur Portfolio 51 (1): 1–53. doi:10.1086/693448.

- Black, J. M. 2023. Branding Trust: Advertising and Trademarks in Nineteenth-Century America, forthcoming. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Blaszczyk, R. L. 2000. Imagining Consumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood to Corning. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Cooke, E. 2019. Inventing Boston: Design, Production, and Consumption. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Edwards, L. F. 2022. Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Engelman, E. R. 2003. “‘The Face That Haunts Me Ever’: Consumers, Retailers, Critics, and the Branded Personality of Lydia E. Pinkham.” PhD diss., Boston University.

- Fleming, E. M. 1982. “Artifact Study: A Proposed Model.” In Material Culture Studies in America, edited by T. J. Schlereth (1999), 162–173. Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History.

- Gamble, R. J. 2015. “The Promiscuous Economy: Cultural and Commercial Geographies of Secondhand in the Antebellum City.” In Capitalism by Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America, edited by B. P. Luskey and W. A. Woloson, 31–52. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Garvey, E. G. 1996. The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture, 1880s to 1910s. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goddu, T. A. 2020. Selling Antislavery: Abolition and Mass Media in Antebellum America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Greenberg, J. R. 2020. Bank Notes and Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Greenhill, J. A. 2017. “Flip, Linger, Glide: Coles Phillips and the Movements of Magazine Pictures.” Art History 40 (3): 582–611. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12290.

- Hahn, B. M. 2011. Making Tobacco Bright: Creating an American Commodity, 1617–1937. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hisano, A. 2019. Visualizing Taste: How Business Changed the Look of What You Eat. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Iskin, R. E. 2014. The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s-1900s. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press.

- Jaffee, D. 2012. A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jury, D. 2012. Graphic Design before Graphic Designers: The Printer as Designer and Craftsman, 1700-1914. New York: Thames & Hudson.

- Laird, P. W. 1998. Advertising Progress: American Business and the Rise of Consumer Marketing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. London: Oxford University Press.

- Lipartito, K. 2016. “Reassembling the Economic: New Departures in Historical Materialism.” American Historical Review 121 (1): 101–139. doi:10.1093/ahr/121.1.101.

- Marchand, S. L. 2020. Porcelain: A History from the Heart of Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Martin, A. S. 2010. Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Backcountry Virginia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mihm, S. 2007. A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Montgomery, C. 1961. “The Connoisseurship of Artifacts.” In Material Culture Studies in America, edited by T. J. Schlereth(1999), 143–152. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press.

- Prown, J. D. 1982. “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method.” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/496065.

- Rivoli, P. 2014. The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Markets, Power, and Politics of World Trade. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rosen, Z. S. 2012. “In Search of the Trade-Mark Cases: The Nascent Treaty Power and the Turbulent Origins of Federal Trademark Law.” St John’s Law Review 83 (3): 827–904.

- Schlereth, T. J., ed. 1999. Material Culture Studies in America. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press.

- Styles, J. 2017. “Fashion and Innovation in Early Modern Europe.” In Fashioning the Early Modern: Dress, Textiles, and Innovation in Europe, 1500-1800, edited by E Welch, 33–55. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tucker, S., K. Ott, and P. Buckler, eds. 2006. The Scrapbook in American Life. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Wajda, S., and H. Sheumaker eds. 2007. Material Culture in America: Understanding Everyday Life. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Woloson, W. 2020. Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Yaneva, A. 2009. “Making the Social Hold: Towards an Actor-Network Theory of Design.” Design and Culture 1 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1080/17547075.2009.11643291.