Abstract

I investigate the effect of family ownership on firms’ disclosure practices in their annual reports. In specific, I study Swedish publicly listed firms, which are typically characterized by controlling owners that have a strong influence in the corporate governance decisions of the firm, including corporate disclosures. To measure disclosure, I construct a comprehensive disclosure index covering information on (1) corporate governance, (2) strategic and financial targets and (3) notes to the financial statements. The results reveal that overall, family firms provide less disclosure in annual reports than non-family firms do. The finding is consistent with the premise that through their management positions, family owners can directly monitor managers and avoid costly public disclosures. Overall, the results suggest that ownership structure of firms is important to consider in understanding firms’ disclosure incentives, particularly in settings where controlling owners play a significant role in the governance of the firm.

1. Introduction

In recent years, accounting researchers have come to understand that many publicly listed firms have controlling owners that play an important role in the corporate governance of the firm (e.g. Burkart, Panunzi, & Shleifer, Citation2003; Hope, Langli, & Thomas, Citation2012; La Porta, López-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, Citation1999; Prencipe, Bar-Yosef, & Dekker, Citation2014; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). A well-accepted perception is that as the ownership stake of a shareholder increases, so does his willingness to monitor managers’ actions in line with those of the shareholders (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). However, when ownership reaches a certain level, controlling shareholders may get entrenched and extract private benefits from minority shareholders (Claessens, Djankov, Fan, & Lang, Citation2002; Morck, Shleifer, & Vishny, Citation1988; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). The existence of controlling owners provides contradictory predictions on agency problems, with the severity of these issues being dependent on existing levels of minority shareholder protection (La Porta, López-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, Citation1998).

In the disclosure literature, it is generally acknowledged that shareholders prefer more disclosure to less, particularly in firms where ownership is dispersed. However, shareholders are not a homogenous group and have different preferences for accounting information, which is why the ownership structure may have a considerable effect on firms’ accounting disclosure decisions. This study adds to a growing body of research on accounting quality and ownership structure (e.g. Ali, Chen, & Radhakrishnan, Citation2007; Hope, Citation2013; Mäki, Somoza-Lopez, & Sundgren, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2006; Weiss, Citation2014). In particular, I study the question of how ownership structure, specifically family ownership, impacts disclosure on corporate governance, strategic information and notes to the financial statements.

A large number of listed firms around the world are controlled and owned by families (Burkart et al., Citation2003) and constitute an important group of shareholders to understand. Their long-term presence in the firm, information advantage, close ties with management and large involvement in business decisions, make them relevant when studying financial disclosure practices. Hence, the characteristics of family owners suggest that they may have different preferences for accounting information than other shareholders do. Moreover, recent studies on disclosure emphasize owners as more than a homogenous group and take their varying preferences for accounting information into consideration in their analyses (e.g. Dou, Hope, Thomas, & Zou, Citation2016). To date, research on family firms and financial reporting quality provides contradictory findings. On one hand, results suggest that compared to non-family firms, family firms provide higher financial reporting quality (Ali et al., Citation2007; Chen, Chen, & Cheng, Citation2014; Wan-Hussin, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2006). On the other hand, studies find that family firms provide fewer earnings forecasts and conference calls (Chen, Chen, & Cheng, Citation2008), report low-quality accounting numbers (Yang, Citation2010) and disclose less on corporate governance practices (Ali et al., Citation2007).

The majority of the mentioned studies employ an Anglo-Saxon setting where minority shareholders have strong investor protection. Thus, it remains an empirical question how disclosure is affected by the ownership structure of a firm in a setting where voting rights and cash-flow rights are commonly separated via the usage of dual-class shares and pyramid structures. In these constellations, family owners can act as controlling minority shareholders and have the control of a firm’s votes, while only owning a small portion of the cash-flow rights (Cronqvist & Nilsson, Citation2003). This in turn increases the severity of agency problems, because the incentives to extract benefits are greater when controlling owners are less sensitive to cash-flow consequences (Claessens et al., Citation2002).

In this study, I focus on Swedish listed firms and their disclosure practices in annual reports for several reasons. First, Sweden has the highest proportion of firms with differentiated voting rights and the second-highest proportion of pyramids of all countries (Faccio & Lang, Citation2002; Institutional Shareholder Services, Citation2007). Second, by tradition, Swedish listed firms have a long history of long-term controlling owners (e.g. Handelsbanken and the Wallenbergs). Third, the majority of the members in Swedish boards are non-executivesFootnote1 and usually appointed by controlling shareholders (Swedish Corporate Governance Code, Citation2016). Whereas in the US the CEO and executives have a large influence on firm decisions, in Sweden the controlling shareholders have a central role in the corporate governance of the firm. In other words, this suggests that variations in corporate disclosure depend on the level of ownership concentration. I extend previous Anglo-Saxon studies on family firms and disclosure practices (e.g. Ali et al., Citation2007; Wang, Citation2006) by employing a Swedish setting, which is characterized by a moderate level of investor protection (La Porta et al., Citation1998). Thus, the prominent agency problem being studied is the one between controlling and non-controlling shareholders.

This study contributes to academics, policy-makers and investors in several ways. First, in the attempt to understand the contradicting empirical findings of disclosure practices by family firms, this study responds to the call of Salvato and Moores (Citation2010) by studying the disclosure practices of family firms in a different institutional setting and capital market (i.e. Sweden). Second, this study employs a broad self-constructed index, where disclosures on corporate governance, strategic information and notes to the financial statements have been hand-collected from companies’ annual reports. Previous studies measure financial reporting quality based on earnings quality proxies (Jaggi & Leung, Citation2007; Jaggi, Leung, & Gul, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2006; Yang, Citation2010), management earnings forecasts (Ali et al., Citation2007; Chen et al., Citation2008) and accounting conservatism (Chen et al., Citation2014). Few studies, though, apply disclosure indices and the disclosure categories differ: corporate governance practices (Ali et al., Citation2007); strategic, non-financial and financial information (Chau & Gray, Citation2002, Citation2010); and mandatory disclosure (Chen & Jaggi, Citation2000). Hence, this study contributes to the literature on controlling owners and disclosure practices by focusing on different aspects of disclosure categories. Third, the results of this study are timely with the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB) Disclosure Initiative project, which aims to improve disclosure in financial reports, as it contributes to a deeper understanding of the effects of the institutional setting and local governance structures on firms’ disclosure practices. Fourth, potential and current investors should be interested in these results, as the results of this study show that family firms are governed differently and are less forthcoming with the disclosure of accounting information in annual reports. This is important considering that prior disclosure research shows that firms’ disclosure practices have an incremental impact on capital markets (e.g. Botosan & Plumlee, Citation2002; Easley & O’Hara, Citation2004; Leuz & Verrecchia, Citation2000).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Sections 2 and 3 provide a review of the literature and the hypothesis of the study. Section 4 outlines the research methodology, including measurement of family firms and the dependent variable corporate disclosure. The empirical findings are presented in Section 5. Lastly, in Section 6, conclusions and limitations of the study are provided.

2. Agency Conflicts in Family Firms

This study focuses on how the presence of controlling owners gives rise to a different type of agency problem in the publicly listed firm. In particular, it focuses on family ownership, and how this in turn influences firms’ disclosure practices in annual reports. Based on the contractual view of the organization, firms can be viewed as being engaged in multiple contracting relationships with various stakeholders, where accounting information is crucial in facilitating efficient contracts (Armstrong, Guay, & Weber, Citation2010). Moreover, a well-acknowledged premise in empirical accounting research is that managers possess firm-specific information, which the contracting party has limited access to, and that the interests between these two parties differ (e.g. Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In cases when ownership is dispersed, owners lack direct communication with management and are more dependent on public accounting information for monitoring purposes. Thus, detailed provision of accounting information becomes an important mechanism to alleviate information asymmetries between the firm and its various contracting parties (Armstrong et al., Citation2010). Similarly, prior research shows that a high quality of disclosure reduces both cost of equity (Botosan, Citation1997) and cost of debt (Sengupta, Citation1998), and improves the stock liquidity of the firm (Verrecchia, Citation2001).

In the publicly listed firm, there are two central equity agency problems. The Type I equity problem is a result of the separation of ownership and control between managers and shareholders (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In lack of substantial managerial ownership, managers may engage in self-maximizing behaviours that do not necessarily benefit outside shareholders. This agency problem is more severe when ownership is widely dispersed and where information asymmetries between the manager and owners are large. But as the manager’s ownership level increases, so does his incentive to act in the interest of the shareholders (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Similarly, as the ownership level of an individual owner increases so does his willingness to monitor the managers’ actions in line with those of the outsiders. However, when ownership reaches a certain level, controlling shareholders may get entrenched and extract private benefits from non-controlling shareholders (Claessens et al., Citation2002; Morck et al., Citation1988; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). Consequently, the central agency problem is the one between controlling and non-controlling owners, which is typically referred to as the Type II equity problem (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997; Villalonga & Amit, Citation2006).

As noted, the presence of controlling owners, which are typically present in family firms, offers us two opposing expectations. The goal alignment effect suggests that when equity ownership of controlling shareholders increases, they have greater incentives to monitor the management (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003; Demsetz & Lehn, Citation1985). Thus, the interests between managers and shareholders are more aligned and Type I equity problems decrease (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The entrenchment effect suggests that high levels of equity ownership entrench controlling owners, causing information asymmetries between insiders and outsiders of firms (Morck et al., Citation1988; Wang, Citation2006). In such situations controlling owners can maximize their own wealth at the expense of outside owners (Claessens et al., Citation2002; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997), consequently contributing to Type II equity problems.

In the following section, I continue the discussion on how Type I and Type II equity agency problems arise in family and non-family firms. The overall expectation in this study is that differences in the severity of various agency problems across the two ownership structures affect firms’ disclosure practices in the form of governance information, strategic information and notes to the financial statements.

3. Prior Research and Hypothesis Development

Around the world, a common ownership structure consists of family members who hold executive positions and thus have a large influence in the firm (Faccio & Lang, Citation2002; Isakov & Weisskopf, Citation2014; La Porta et al., Citation1999). The distinctive characteristics that separate the governance in family firms from non-family firms may have an incremental impact on their disclosure practices. In specific, compared to other controlling owners, founders have a ‘personal’ interest in the firm and wish to pass on the business to their next generation (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2004). Thus, founders may be more concerned about protecting their reputation and avoiding public scrutiny. For instance, Chen et al. (Citation2008) show that family firms are more likely to disclose earnings warnings and are less forthcoming with providing earnings forecasts because of litigation and reputation concerns. Furthermore, Fan and Wong (Citation2002) show that East Asian firms with concentrated ownership have low earnings informativeness as these firms avoid disclosure of proprietary information about their rent-seeking activities. Lastly, Ali et al. (Citation2007) show that US family firms are less inclined to provide disclosures about governance matters, which could increase interference from outside investors.

However, pressures from capital markets may incentivize managers to provide high financial reporting quality to lower agency costs. Burgstahler, Hail, and Leuz (Citation2006) show that as a result of the higher capital market pressures faced by publicly listed firms, these firms are less likely to manage their earnings than private firms are. Similarly, Botosan (Citation1997) shows that firms that provide higher levels of disclosure and those that are followed by few analysts are associated with a lower cost of equity. Because of these financial benefits of disclosure, it could be argued that firms are also willing to provide additional disclosure. However, in family firms, family members’ long-term presence in the firm suggests that they deal with the same contracting parties (e.g. capital providers and creditors) for longer periods. For instance, a consequence of founders’ long-term presence is that they enjoy a lower cost of debt compared to non-family firms (Anderson, Mansi, & Reeb, Citation2003). This suggests that family firms already have established relationships with their capital providers and information asymmetries between their contracting parties are low, which in turn make them less incentivized to engage in disclosures. Similarly, because of their long-term investment horizon, Chen et al. (Citation2008) find that among S&P 1500, family firms provide fewer management forecasts than what non-family firms do.

Another feature of family firms is the high presence of family members at the top management level and their personal ties to other executives in the firm (Hope et al., Citation2012). Family members thus have access to inside corporate information, which enables them to directly monitor the manager through private channels without being heavily dependent on public information (Chau & Gray, Citation2010; Chen et al., Citation2008). As such, they avoid leakage of costly proprietary information to competitors. This consequently reduces Type I equity agency problems between managers and shareholders but causes a surge in Type II equity agency problems between controlling and non-controlling shareholders.

In sum, family owners are a distinctive type of owners who value their reputation, have long-term investment horizons and close relationships with firm executives. Because of these features, there are reasons to expect that family owners may have little preference for high-quality financial reporting and provision of additional disclosure. Prior research in the field, however, provides contradicting findings on family firms’ financial reporting quality. On the one hand, evidence shows that family firms have higher levels of earnings quality (Ali et al., Citation2007; Cascino, Pugliese, Mussolino, & Sansone, Citation2010; Wang, Citation2006), have more incentives for conservative financial reporting (Chen et al., Citation2014), have higher levels of segment disclosure (Wan-Hussin, Citation2009) and provide more earnings warnings (Chen et al., Citation2008). On the other hand, findings show that family firms have lower levels of overall disclosure (Chau & Gray, Citation2002; Citation2010; Chen & Jaggi, Citation2000; Ho & Shun Wong, Citation2001) and corporate governance disclosure (Ali et al., Citation2007), exhibit higher levels of earnings management (Prencipe & Bar-Yosef, Citation2011; Yang, Citation2010), and provide fewer earnings forecasts and conference calls (Chen et al., Citation2008). These inconsistent results are likely due to national differences and varying features in capital markets (Salvato & Moores, Citation2010).

In contrast to prior research, this study examines a setting in which controlling owners have a large influence in the governance of firms. Although a high ownership stake may incentivize the owner to act in the interest of outside owners (i.e. incentive alignment effect), Swedish listed firms are known for their wide usage of control-enhancing mechanisms, such as dual-class shares and pyramid structures. These mechanisms allow controlling owners to separate control (voting rights) from ownership (cash-flow rights) and as such only invest a small portion of their equity rights while retaining large control of the firm, i.e. acting as controlling minority shareholder (Cronqvist & Nilsson, Citation2003). These ownership constellations are likely to increase Type II equity problems as the controlling owner may get entrenched and act in his own interest without bearing the financial consequences of this. For instance, Fan and Wong (Citation2002) find that as the deviation between control ownership increases, the less informative earnings are. Their finding is further explained by two premises: (1) controlling owners are perceived to report accounting information for self-interested purposes and (2) controlling owners prevent leakage of proprietary information about the firm’s rent-seeking activities (Fan & Wong, Citation2002).

Essentially, the characteristics of family firms make Type I equity agency problems less severe compared to a firm where ownership is diffused. However, in the presence of controlling owners two opposing effects are noted: the incentive alignment effect and the entrenchment effect. The entrenchment effect is expected to be more severe in settings where control is separated from ownership (via the usage of e.g. dual-class shares). As mentioned, Swedish firms commonly employ these mechanisms, but at the same time are known for exhibiting low levels of earnings management in international comparisons (Leuz, Nanda, & Wysocki, Citation2003). Thus, it remains an empirical question how family ownership affects Swedish listed firms’ disclosure practices and therefore, in line with Wang (Citation2006), the hypothesis of this study is formulated as nondirectional:

Hypothesis 1: Disclosure practices by Swedish listed firms are systematically related to family ownership.

In sum, relying on the principal–agency theory, I expect that disclosure practices differ depending on the structure of ownership and the degree of agency conflicts present in a firm. Furthermore, the unique characteristics of family firms and the severity of Type II equity problems are likely to have different impacts on disclosure practices than those observed in non-family firms.

4. Data and Research Design

4.1. Sample

An overview of the sample selection is presented in . The empirical analysis is based on publicly listed firms on the Stockholm Stock Exchange in the years 2001–2010. Before any observations are excluded, the sample consists of 2671 firm-year observations (375 firms). Consistent with prior studies (e.g. Wang, Citation2006), foreign firms, investment firms and financial institutions are excluded from the sample as these types of firms may follow different disclosure rules. In addition, firms with revenues of less than SEK 25 million and negative equity are also excluded from the initial sample. After the aforementioned exclusions, the final sample consists of 2182 firm-year observations (314 firms), of which 990 (163 firms) are family firms. Further, in 494 firm-year observations (87 firms) the founder is present in the firm (as the largest owner or by possessing a management position). The industry distributions over the final sample are shown in Panel B in . The manufacturing industry with 1039 firm-year observations represents the largest industry group, whereas the wholesale and retail industry with 229 firm-years composes the smallest industry group.

Table 1. Sample selection

Accounting and capital market data are collected from data sources, including Thomson Datastream, Compustat Global and SixTrust. Ownership data for all Swedish firms are obtainable from SIS Ägarservice AB's publications (Fristedt & Sundqvist, Citation2001–2009; Sundqvist, Citation2010) and, when necessary, information on a firm included in the sample has been manually collected from annual reports. In general, Swedish publicly listed firms disclose detailed ownership statistics in their annual reports. Disclosure index data are manually collected from each firm’s annual report.

4.2. The Disclosure Index

A disclosure index is constructed to measure the extent of disclosure provided in firms’ annual reports. Although previous studies on family firms and financial reporting quality mainly employ metrics on earnings quality, accounting conservatism and frequency of management earnings (e.g. Ali et al., Citation2007; Chen et al., Citation2008; Wang, Citation2006), the purpose of this study is to extend this avenue of research by examining whether the information content of annual reports differs between Swedish family firms and non-family firms. The index applied in this study contains three disclosure categories: corporate governance, strategic information and notes to the financial statements. More specifically, corporate governance information includes matters that cover presentation of board members, internal control, largest owners and executive compensation practices.Footnote2 Strategic information includes disclosure items on financial targets, strategy, forecasts and competitors. The third category, notes to the financial statements, concerns the number of pages devoted to the annual report, notes to the financial statements and the length of the note concerning accounting policies. presents an overview of the scoring procedure and the disclosure items included in the index.

Table 2. The disclosure index

Each disclosure category includes a number of disclosure items that could potentially be disclosed by a firm. Following previous studies in the disclosure literature, all disclosure items are equally weighted, and no information is regarded as more valuable than any other information (e.g. Chau & Gray, Citation2010).Footnote3 The scoring procedure is based on a binary basis in which disclosure of an individual item provides one point and missing or insufficient disclosed information provides zero points. Some of the disclosure items listed in count the number of pages or the number of notes used for a certain type of disclosure information (i.e. disclosure items: 1–3 and 34–37), whereas other disclosure items require a qualitative assessment on the disclosure content by the data gatherer. For instance, disclosure Item_9 and Item_10 concern variable compensation of the CEO and require a qualitative assessment of the disclosure content. An example of a firm that obtains full points on Item_9 and Item_10 is the ball bearing factory SKF, which discloses following information in their 2010 annual report:

The variable salary of a Group Management member runs according to a performance-based programme. The purpose of the programme is to motivate and compensate value-creating achievements in order to support operational and financial targets. The performance-based programme is primarily based on the short-term financial performance of the SKF Group established according to the SKF management model Total Value Added (TVA). TVA is a simplified economic value added model. This model promotes improved margins, capital reduction and profitable growth. TVA is the operating result, less the pre-tax cost of capital in the country in which the business is conducted. The TVA result development for the SKF Group correlates well with the trend of the share price over a longer period of time. The maximum variable salary according to the programme is capped at a certain percentage of the fixed annual salary. The percentage is linked to the position of the individual and varies between 40% and 70% for Group Management members. If the financial performance of the SKF Group is not in line with the requirements of the variable salary programme, no variable salary will be paid. The maximum variable salary will not exceed 70% of the accumulated annual fixed salary of Group Management members.

[…] Additionally, Tom Johnstone was entitled to short-term variable salary of SEK 2,220,960 related to 2009 performance. The short-term variable salary was, however, not paid out in cash to Tom Johnstone but converted into additional pension contribution. Tom Johnstone’s fixed annual salary 2011 will amount to SEK 10,000,000. The variable salary in 2010 was according to a performance-based programme divided into two parts, a short-term and a long-term part, both based on the financial performance of the SKF Group established according to the Group’s management model which is a simplified economic value-added model called Total Value Added (TVA), see page 22 […]. (SKF Annual report Citation2010, pp. 87–88)

Finally, an aggregated disclosure score is estimated for each firm-year observation by adding up all scores obtained from each disclosure item listed in (hereafter referred as the DScore). Thus, the total DScore a firm-year observation can possibly obtain is 37 points, which implies that the higher the DScore, the more informative the annual report is. The following equation represents the calculation of the aggregated DScore for each firm-year observation:

4.2.1. Assessing the validity of the disclosure index

Estimating the Cronbach’s alpha is a common way to assess the validity of the disclosure index for capturing disclosure (e.g. Botosan, Citation1997; Gul & Leung, Citation2004). Cronbach’s alpha measures the internal consistency of the disclosure index and to what extent all disclosure items measure the same construct, i.e. disclosure of accounting information in annual reports. Hence, if a firm-year observation scores high on strategic information, it is expected to score high in the remaining disclosure categories. The Cronbach’s alpha for the three categories in the index is 0.61, suggesting a quite poor internal consistency and that random error could decrease the power of tests in this paper. However, prior disclosure studies also obtain similar low Cronbach’s coefficient alphas of 0.51 (Gul & Leung, Citation2004) and 0.64 (Botosan, Citation1997). Additionally, the Pearson’s correlation test presented in shows that the DSCORE is positively correlated with firm size (SIZE), leverage (LEV), reputable audit firm (BIG4) and firm performance (ROA), which is consistent with prior disclosure and firm-level determinant studies (e.g. Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999). Therefore, the disclosure index is believed to be a reliable measure of disclosure quality in this study.

4.3. Defining Family Firms

Initially, the overall question of this study is whether family firms exhibit disclosure practices different from those of non-family firms? To answer this question, a measure that captures the distinctive family firm effect on disclosure practices needs to be constructed. Previous studies generally capture family members’ influence on corporate decisions by examining their ownership, control and management in the firm (e.g. Villalonga & Amit, Citation2006). A firm is commonly classified as a family firm depending on whether the founder and/or their descendants hold positions in the top management, serve on the board of directors or are among the firm’s largest shareholders (Ali et al., Citation2007; Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003; Chen et al., Citation2008, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2006). As detailed disclosure of ownership information is not always mandatory in annual reports, a majority of previous Anglo-Saxon studies adopt a five per cent ownership cut-off to identify a family owner. In Sweden, however, publicly listed firms choose to provide detailed disclosure on their owners and are known for transparent ownership structures (Cronqvist & Nilsson, Citation2003). This allows us to identify founders and family members who own less than five per cent of the voting rights. Moreover, recognizing that Swedish firms frequently use dual-class shares (Faccio & Lang, Citation2002), a more stringent family firm definition is needed, which considers the ownership of voting rights. Studies find that firm value increases with cash-flow ownership and decreases when the level of control rights of the largest shareholder exceeds its cash-flow ownership (Claessens et al., Citation2002; Cronqvist & Nilsson, Citation2003; Villalonga & Amit, Citation2006).

Similar to prior research (e.g. Ali et al., Citation2007; Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003), a firm is defined as a family firm in this study if the founder or a member of his or her family is the largest owner of the firm and/or possesses one of the following management positions: CEO, chairman or board member. However, because of the highly concentrated ownership structure in the studied setting, I use a higher threshold of ownership to define a family firm, namely the founder or a family member should own at least 20% of the voting rights. Furthermore, because of the access to detailed ownership data, I am also able to identify whether the founder is present in the management of the firm. Thus, in additional analyses, I test the presence of founders in the management (i.e. CEO, chairman of the board or a board member) on firms’ disclosure practices. Lastly, family firms are also identified by solely examining the total percentage of voting rights possessed by the founder or a member of his or her family.

4.4. The Regression Model

To test the hypothesis, the following general model is applied:where DSCORE is the disclosure score obtained by firm i at time t, where a higher disclosure score means higher levels of disclosed information. The maximum disclosure score is 37, which implies that a firm-year observation has scored the highest on each disclosure item included in the disclosure index; FAMILY is a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if the firm is controlled and owned by the founder or a member of his or her family (i.e. owns ≥20% of the voting rights and/or possesses one of the following management positions: CEO, chairman or board member) for firm i at time t. In additional tests, two alternative variables on family firms are employed: (1) a continuous variable, OWNERSH, which captures the total level of voting rights possessed by the founder or a member of his/her family, (2) a dummy variable FOUNDER, which takes on the value of 1 when the founder is present in the management of the firm. Controls include the control variables firm size (SIZE), firm age (AGE), a dummy for main auditor being employed by one of the four largest audit firms (BIG4), leverage (LEV), firm performance (ROA), market-to-book (MTB), for firm i at time t. See for a description of the test and control variables.

Table 3. Definition of test and control variables

In accordance with the hypotheses, I expect the coefficient of FAMILY to be related to DSCORE, but with no prior expectation on its direction. Furthermore, prior disclosure research suggests that there are several reasons why firm size is positively correlated with disclosure behaviours of firms. First, according to agency theory, larger firms have higher agency costs and thus disclose more information to overcome these costs (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Second, larger firms are likely to have more widespread ownership structures (Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999). Third, larger firms have higher political costs (higher media exposure) and are more concerned about reputational damages and are therefore expected to provide higher levels of disclosures (Watts & Zimmerman, Citation1986). Prior disclosure research consistently documents that firm size is associated with corporate disclosures, but also that traditional proxies of firm size are noisy for testing political or agency cost hypotheses (Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999; Ball & Foster, Citation1982). For this reason, the regression analyses in Section 5 are performed in two alternative ways in which firm size is controlled for. First, I conduct a regression analysis on the total sample while controlling for firm size (SIZE). Second, I perform the regression analysis on the 25% largest firms in the sample, excluding the control variable firm size (SIZE) from the model.

Furthermore, AGE is included to control for firms that have been listed on the stock exchange for several years, as they are expected to provide higher levels of disclosure. Audit literature suggests that large audit firms provide higher audit quality because of reputational cost concerns (DeAngelo, Citation1981). In line with the finding of Francis, Maydew, and Sparks (Citation1999) that Big 6 auditors are associated with higher earnings quality, I expect that firms that are audited by one of the Big 4 (BIG4) provide more detailed disclosure. Moreover, I expect that firms that rely on public debt financing (LEV) provide higher levels of disclosure in order to lower monitoring costs (e.g. debt financing) and meet the information demands of creditors and credit agencies (Armstrong et al., Citation2010; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). I also control for firms’ growth prospects (MTB) and firm performance (ROA). Firms with growth opportunities may provide more disclosure to minimize information asymmetries with their contracting parties and poorly performing firms are likely to be less forthcoming with providing additional disclosure that conceals their bad performance (Chau & Gray, Citation2010). In addition, performance differs between family and non-family firms (Ali et al., Citation2007; Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003). Lastly, industry and year dummies are included to control for disclosure variations across industries and over years.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

provides the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between all the test variables. Not surprisingly, all four disclosure variables (DSCORE, GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES) correlate highly positively with each other (p-value < .05). Furthermore, there is a significant negative correlation between family firms (FAMILY) and level of disclosure. This is evident for all the four disclosure variables (DSCORE, GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES), which show a correlation coefficient of −0.188, −0.203, −0.084 and −0.144 (p-value < .05), respectively. As consistent with prior disclosure studies (e.g. Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999) DSCORE, GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES are positively correlated with firm age (AGE), firm size (SIZE), leverage (LEV), reputable audit firm (BIG4) and firm performance (ROA). Notable, is that firm size (SIZE) is highly positively correlated with disclosure levels (coefficient < 0.325).

Table 4. Pearson correlation test between the test variables

provides descriptive statistics on firm characteristics of the whole sample (Panel A) and of family and non-family firms (Panel B). Consistent with previous findings, the results indicate that, on average, family firms rely on external debt funding to a lesser extent than non-family firms (e.g. Ali et al., Citation2007). Moreover, family firms are both smaller in size and younger in age compared to non-family firms. Both SIZE and AGE are significantly different at the one percentage level. Furthermore, family firms are more profitable than their counterpart. This is in line with the findings of Anderson and Reeb (Citation2003) and also holds true when Tobins Q is used as a performance variable instead (t = 2.55) (untabulated).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics

Furthermore, the data in show that the mean of BIG4 is significantly lower for family firms than for non-family firms, suggesting that family firms employ one of the four largest audit firms less frequently. In sum, from the descriptive statistics, we can clearly note that there are significant differences between family and non-family firms in their capital structures, size, age, profitability and likelihood of employing a Big4 auditor.

presents governance characteristics of the 163 family firms in the sample. From the table, it is evident that a founder is the largest owner in 27 per cent of the family firms in our sample. Moreover, provides an overview of founders’ possible involvement in different management positions. A founder or his/her family member possesses a management position, i.e. is the CEO, chairman of the board or a board member, in 35 per cent of the family firms. More precisely, the founder is a CEO in 13 per cent of the family firms, a board member in 24 per cent and the chairman of the board in 11 per cent of the family firms. The data indicate that founders do play an important role in family firms’ corporate governance, because their significant presence in influential management positions is hard to overcome.

Table 6. Governance characteristics of the 163 family firms

Furthermore, it is also evident that founders and their heirs own 41 per cent of the total voting rights in family firms. The presence of voting rights is enabled by the issuance of dual-class shares, which provide the holder with distinct voting rights and dividend payments. More specifically, 26 per cent of the family firms in the sample employ dual-class shares.

5.2. Descriptive Statistics for the Disclosure Index

To obtain a better understanding of disclosure differences between family and non-family firms, presents detailed descriptive statistics of each specific disclosure item included in the index.

Table 7. Descriptive statistics on the disclosure index

All corporate governance related disclosure items, except for the termination item, are significantly different for family firms than for non-family firms. Specifically, family firms devote fewer pages on corporate governance matters and internal control than non-family firms (t = 5.09 and 4.92, respectively). Furthermore, on average, family firms also provide less information on their board members’ attendance level on meetings, previous working experience and information about financial analysts following the firm, with t-statistics of 3.07, 7.81 and 4.29, respectively. With regard to information on the CEO’s compensation package (including the variable component pay), retirement and severance conditions, family firms provide significantly less information than non-family firms do (t = 5.70, 6.55, 6.24, 7.61, 6.12 and 2.73, respectively). This pattern is also similar for disclosure on other top executives’ compensation packages, where family firms significantly score lower than non-family firms do (t = 6.74, 8.65 and 10.50, respectively). However, a somewhat interesting result is that family firms are more forthcoming with presenting detailed information about their largest shareholders (t = −3.07) and information regarding the firm’s shares (t = −1.75) than non-family firms are.

The majority of the disclosure items in the second disclosure category, strategic information, are significantly different for family and non-family firms. Specifically, the descriptive statistics indicate that family firms are more reluctant to disclose any kind of financial target than non-family firms are (t = 1.94, 3.61 and 5.26, respectively). Further, family firms evaluate their past performance in relation to their targets to a lesser extent than non-family firms do (t = 4.79). Family firms are also less forthcoming in providing disclosure regarding their corporate strategies and strategies on how to reach targets (t = 5.04 and t = 2.87). Moreover, family firms appear to be less willing to provide information about their competitors (t = 2.27) and about their position in product markets (t = 4.09), than non-family firms are. However, family firms are more forthcoming with providing forecasts on their financial targets than what non-family firms are (t = −3.18 and t = −1.72)

The third disclosure category concerns the notes to the financial statements, including the number of notes provided, the length of the note covering accounting principles and the number of total pages in the annual report. From the data in , it is notable that annual reports of family firms contain fewer pages than annual reports of non-family firms (t = 5.48). In addition, family firms, on average, also have fewer notes and devote fewer pages to the notes (including the note describing accounting policies).

Overall, we see a clear pattern from the results provided in , and that family firms provide significantly less disclosure on the majority of the disclosure items included in the disclosure index. However, it is also observable that family firms are more likely to disclose information about their largest owners, the firm’s shares and about their future prospects than non-family firms are.

The data support the notion that information asymmetries in family firms are less severe than in non-family firms (i.e. lower Type I equity agency problems), which is why these firms are less forthcoming in providing disclosures. However, these results do not take additional determinants of disclosure into consideration, which could have a significant impact on our interpretations. Therefore, in the following analyses, multiple regression analyses are adopted where well-known disclosure determinants are controlled for.

5.3. Regression Results

To examine whether family ownership affects the level of disclosure provided by firms, pooled OLS regression is employed in the analyses. Panel A in provides regression results for the hypothesis on whether family ownership affects the disclosure practices of Swedish listed firms. Results are reported for the whole disclosure index (DSCORE), but also for each disclosure category: GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES. Each model includes controls for market-to-book (MTB), firm age (AGE), leverage (LEV), Big 4 audit firm (BIG4), performance (ROA), firm size (SIZE), year and industry fixed effects. Furthermore, to avoid serial correlation in the independent variables and in the residuals, standard errors are clustered at the firm level. The main variable of interest is the FAMILY variable, which is the indicator for family firms and captures Type II agency problems, i.e. agency conflicts between family owners and non-controlling owners. FAMILY takes on the value of 1 if a firm is controlled and owned by the founder or a member of his or her family (i.e. owns ≥ 20% of the voting rights and/or possesses one of the following management positions: CEO, chairman or board member). Model (1) in shows that FAMILY is negatively related to the overall disclosure (DSCORE) provided in firms’ annual reports, however, the relationship is insignificant.

Table 8. Regression results

Continuing with the regression results for the three sub-components of the index: GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES (i.e. Models 2, 3 and 4), we note that family firms are significantly less forthcoming with disclosures on specifically corporate governance matters (Model 2). This is in line with Ali et al. (Citation2007), who show that S&P 500 family firms provide less corporate governance disclosure than non-family firms do. For the two disclosure categories covering strategic information (STRATEGIC) and notes to the financial statements (NOTES), no significant association is documented with the FAMILY variable.

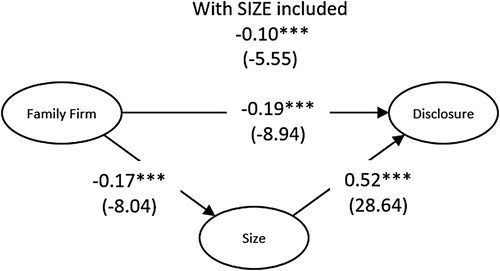

When significant, the control variables exhibit relations that are consistent with expectations, except for firm performance (ROA) in Model 4. Accordingly, it appears that well-performing firms provide fewer disclosures in their notes. Further, firm size (SIZE) is, as expected, strongly significant and positively related to the disclosure in the four models. In addition, from the correlation matrix in , it is also notable that SIZE is strongly correlated with our disclosure variables (DSCORE, GOVERNANCE, STRATEGIC and NOTES). As discussed in Section 4.4, prior disclosure research suggests that there are several reasons why firm size is positively correlated with disclosure behaviours of firms and that traditional proxies of firm size are noisy for testing political or agency cost hypotheses (Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999; Ball & Foster, Citation1982). In order to test for a possible mediation effect of firm size (SIZE) on the family firm (FAMILY) and disclosure (DSCORE) association, I conduct path analysis and follow the mediation test logic of Baron and Kenny (Citation1986). From the path analysis illustrated in , it is evident that the significant standardized beta coefficient of FAMILY drops to about half (i.e. from −0.19 with t-value: −8.94 to −0.10 with t-value: −5.55), when firm size (SIZE) is also included in the model. Important to mention is that FAMILY remains significant and has the same and negative association with disclosure score (DSCORE), even when firms size (SIZE) is included. Thus, from the path analysis, it is notable that firm size has a partial mediation effect on the family firm and disclosure relationship. This explains why FAMILY has a stronger significant relation with DSCORE when SIZE is left out from the regression analysis (untabulated).

Figure 1. Path analysis

Note: Reported values are the standardized beta coefficients and t-values within parentheses, where the significant levels are denoted as follows: *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .001. Following steps are followed in the path analysis: Step 1: DSCORE = β0 + β1FAMILY1 + e; Step 2: DSCORE = β0 + β1SIZE1 + e, Step 3: SIZE = β0 + β1FAMILY1 + e and Step 4: DSCORE = β0 + β1FAMILY1 + β1SIZE1 + e.

Due to the strong effect of firm size, I conduct a follow-up analysis on the quartile of firms including the largest firms in the sample. In specific, this quartile includes 542 firm-year observations and represents the largest firms by total assets in each financial year. Thus, firm size as a control variable is left out from this test. The regression results from this analysis are presented in Panel B in , and it is notable that our variable of interest, FAMILY, is statistically significant and negatively related with the overall disclosure in annual reports (DSCORE). Similarly, consistent with prior tests, family firms are less willing to provide disclosure on corporate governance matters (GOVERNANCE). Interestingly, FAMILY is significant and positively related to disclosures regarding notes (NOTES) to the financial statements. This could be explained by the fact that the test is performed on the largest group of the firms in the main sample and that larger firms generally have more complex business structures. Last, no significant association is noted for the strategic disclosure category (STRATEGIC).

In sum, the regression results reported in exhibits that family firms provide less disclosure in their annual reports than their counterparts do. This is particularly evident in the disclosure category covering corporate governance matters. Because of the strong correlation between the firm size and the disclosure measures, an additional test on the largest groups of firms in the sample is performed. The additional tests further strengthen the perception that family firms are less willing to provide overall disclosure than non-family firms are.

5.4. Additional Tests

As the definition of family firms may be sensitive to the results, I conduct additional tests in which different family firm variables and definitions are adopted. First, I employ a continuous variable which indicates the percentage of voting rights controlled by the founder and his/her family members (OWNERSH). Second, I use a dummy variable, FOUNDER, which takes on the value of one if the founder is present in the management of the firm (i.e. as the CEO, chairman or board member).

The results for the continuous family variable OWNERSH are tabulated in Panel A in , where Model (1) presents the results for the overall disclosure measure (DSCORE) and Models (2–4) exhibit the results per disclosure category: Governance, Strategic and Notes. The same control variables used in the main analysis, firm and industry fixed effects, are used again here. From these results, it is apparent that as family ownership in voting rights increases, lower levels of overall disclosure are provided (Model 1). Further, a strong significant and negative association between family ownership (OWNERSH) and corporate governance disclosure (GOVERNANCE) is documented in Model (2). Regarding strategic disclosure (STRATEGIC) and notes to the financial statements (NOTES), no significant association is found. However, as documented in the path analysis, firm size (SIZE) has a partial mediation effect on the family and disclosure relationship. Thus, I also perform the same test on the largest group of the firms in the sample (542 observations) and exclude firm size (SIZE) from the analysis. Untabulated results show that family ownership (OWNERSH) is strongly significant and negatively related with all of the four different disclosure categories.

Table 9. Regression results

Next, I utilize the access to detailed ownership data, which allows me to examine whether the presence of a founder in the management team (FOUNDER) has an incremental effect on disclosure practices of firms. The results for the whole sample are presented in Panel B in and it is noted that the presence of founders in the firm has a negative association with the level of overall disclosure (DSCORE) provided by firms. Similarly, founding firms are also less willing to provide information on corporate governance matters (GOVERNANCE). In line with the main results, founder (FOUNDER) has no significant relation with disclosure on strategic information (STRATEGIC) and notes to the financial statements (NOTES).

Last, I also perform the same test on the largest group of the firms in the sample and document a negative association between FOUNDER and overall disclosure (DSCORE), corporate governance matters (GOVERNANCE) and strategic information (STRATEGIC). However, the founder is positively related with notes disclosure category (NOTES), which is likely due to the fact that larger firms are more complex and therefore use more disclosure to explain their accounting choices (untabulated results).

In sum, the regression analyses show that family firms are less forthcoming with accounting disclosure in their annual reports after the known disclosure determinants are controlled for. This is further supported by a number of additional tests. In specific, three different definitions of family firms are tested: (1) a dummy variable which combines possession of a management position and a threshold of 20% of the voting rights, (2) a continuous variable capturing the percentage of voting rights of founder and their heirs and (3) a dummy variable for founder presence in the management team. A clear trend is that family firms have a negative association with overall levels of disclosure and with disclosures concerning the firm’s corporate governance matters. These findings confirm the expectation that family firms are systematically associated with the disclosure practices of firms and reluctant with providing additional disclosures. This is in line with the findings of Chau and Gray (Citation2002), who find for a sample of Hong Kong and Singaporean firms that family-controlled firms have little motivation for disclosure because of the weak demand from the stakeholders.

6. Conclusions

Although several studies have explained the determinants of corporate disclosure, few have explored the effect of ownership structure in a context in which controlling owners have a large influence in the governance of the firm. In this study, I examine the effect of family owners on disclosure practices in firms’ annual reports. The Swedish setting being examined is characterized by a large presence of controlling owners at the board level and wide usage of dual-class shares and pyramid ownership structures, and the central agency conflict being studied is the one between controlling and non-controlling owners. Overall, I predict and find that the specific characteristics of family firms and the occurrence of distinctive agency conflicts other than those observed in non-family firms affect firms’ disclosure behaviours.

Multivariate regression analyses on a sample of Swedish listed firms during the years 2001–2010 suggest that family firms are less forthcoming with providing overall disclosure than what non-family firms are. Further, examining the sub-components of disclosure categories, i.e. Governance, Strategic and Notes, the results indicate that family firms are especially less forthcoming with providing disclosure on corporate governance matters. These results are in line with the idea that family firms face less severe Type I equity problems (i.e. between the management and the owners) and with the information effect explanation (Fan & Wong, Citation2002). Specifically, because of the characteristics of family firms, information asymmetries with their contracting parties are lower and thus family firms are able to avoid costly proprietary disclosures.

This study positions the family firm in a different light, as previous US studies on the subject support the incentive goal alignment hypothesis and the premise that family firm ownership mitigates agency conflicts (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2014). However, this study suggests that family firms do not necessarily mitigate agency conflicts through disclosure. Rather, the results indicate that either agency conflicts are mitigated differently or are not as pronounced as in non-family firms. This could be explained by the Swedish setting in which ownership and control are commonly separated via the usage of dual-class shares and pyramid structures. Thus, family owners could use this opportunity to avoid public disclosures of sensitive information and utilize informal communication channels instead. The findings, however, do not suggest that investors in Swedish listed firms are ‘worse off’, but rather that family firms are traditionally governed differently.

This study provides several contributions. First, this study contributes to the debate on family firms and financial reporting quality, which as of yet is inconclusive (e.g. Ali et al., Citation2007; Cascino et al., Citation2010; Chau & Gray, Citation2002; Chen et al., Citation2008, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2006; Yang, Citation2010). It does so by examining a different institutional setting and by employing a self-constructed disclosure index that captures both quantitative and qualitative aspects of the disclosure in firms’ annual reports. In a setting with strong controlling owners, I find that ownership structure is an important determinant of firms’ cost–benefit decision to provide disclosure. Second, this study should be of interest to international policy-makers whose institutional context is similar. Generally, Sweden is referred to as a country with low earnings management and high disclosure quality (Leuz et al., Citation2003). However, this study shows that at the country level, disclosure variations persist, and ownership structure is an important aspect to consider in framing international disclosure regulations. Given IASB’s disclosure initiative project, these results are particularly timely.

I acknowledge that this study has some limitations which, in turn, suggest opportunities for future research. First, I employ a self-constructed disclosure index, which contains both quantity and quality features of the disclosure. Future research could benefit from recent advances in text analysis, and construct measures focusing on the qualitative aspect of disclosure (e.g. Li, Citation2008). Second, an important implication of disclosure studies is whether high-disclosing firms are rewarded in the form of lower cost of equity. This study, however, does not investigate the capital market effect of family firm ownership. Thus, future studies could investigate whether the information disadvantage observed in family firms in this study is reflected in their cost of equity or other capital market effects such as liquidity and bid–ask spread. Third, this study, as other disclosure studies, suffers from endogeneity issues (Beyer, Cohen, Lys, & Walther, Citation2010). Although additional tests have been performed to overcome concerns related to measurement error and partial mediation effects, this study might not fully account for all potential endogeneity problems.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editor of this journal and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Furthermore, I thank the participants of the 39th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association (Maastricht, May, 2016), and the 12th workshop on European Financial Reporting (Fribourg, September, 2016) for useful comments on earlier versions of the paper. Furthermore, I would like to thank Mattias Hamberg, Associate Professor at the Department of Business Studies at Uppsala University, for instructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper and for providing access to compilation of ownership data. I also thank David Andersson, researcher at the Department of Business Studies, Uppsala University.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to Swedish law, the same person cannot hold the positions of both CEO and chair of the board (Swedish Company Act, Citation2005). In addition, Swedish listing regulations restrict the number of executives on the board to only one executive (which is usually the CEO).

2 The part of the index concerning the executive compensation disclosure was collectively gathered and used in another study by Cieslak, Hamberg, and Vural (Citation2018).

3 Prior disclosure studies also apply an alternative method and allow weight to certain disclosure items/information that is regarded as more informative or has different importance to different user groups. For instance, Botosan (Citation1997) provides additional points for firms providing quantitative information and for a directional prediction or point estimate on forecasted information. However, researchers have raised the concern of subjectivity involved in weighting disclosure items and it is also expected that firms better at disclosing ‘important’ items are also good at disclosing ‘unimportant’ items (Ahmed & Courtis, Citation1999; Chau & Gray, Citation2010; Meek, Roberts, & Gray, Citation1995). Similarly, in line with mentioned concerns, this study follows an unweighted scoring procedure.

References

- Ahmed, K., & Courtis, J. (1999). Associations between corporate characteristics and disclosure levels in annual reports: A meta-analysis. British Accounting Review, 31(1), 35–61. doi: 10.1006/bare.1998.0082

- Ali, A., Chen, T.-Y., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2007). Corporate disclosures by family firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44(1–2), 238–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.01.006

- Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding family ownership and the agency cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 68, 263–285. doi: 10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00067-9

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00567

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2004). Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 209–237.

- Armstrong, C. S., Guay, W. R., & Weber, J. P. (2010). The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 179–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001

- Ball, R., & Foster, G. (1982). Corporate financial reporting: A methodological review of empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research, 20, Supplement: Studies on current research methodologies in accounting: A critical evaluation, 161–234. doi: 10.2307/2674681

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Beyer, A., Cohen, D. A., Lys, T. Z., & Walther, B. R. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 296–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.003

- Botosan, C. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323–349.

- Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 21–40. doi: 10.1111/1475-679X.00037

- Burgstahler, D., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2006). The importance of reporting incentives: Earnings management in European private and public firms. The Accounting Review, 81, 983–1016. doi: 10.2308/accr.2006.81.5.983

- Burkart, M., Panunzi, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58(5), 2167–2202. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00601

- Cascino, S., Pugliese, A., Mussolino, D., & Sansone, C. (2010). The influence of family ownership on the quality of accounting information. Family Business Review, 23(3), 246–265. doi: 10.1177/0894486510374302

- Chau, G., & Gray, S. J. (2010). Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 19(2), 93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2010.07.002

- Chau, G. K., & Gray, S. J. (2002). Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosure in Hong Kong and Singapore. The International Journal of Accounting, 37(2), 247–265. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7063(02)00153-X

- Chen, C. J. P., & Jaggi, B. (2000). Association between independent non-executive directors, family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 19(4), 285–310. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4254(00)00015-6

- Chen, S., Chen, X., & Cheng, Q. (2008). Do family firms provide more or less voluntary disclosure? Journal of Accounting Research, 46(3), 499–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00288.x

- Chen, S., Chen, X., & Cheng, Q. (2014). Conservatism and equity ownership of the founding family. European Accounting Review, 23(3), 403–430. doi: 10.1080/09638180.2013.814978

- Cieslak, K., Hamberg, M., & Vural, D. (2018). Executive compensation disclosure incentives: The case of Sweden. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Business Studies, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J. P. H., & Lang, L. H. P. (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2741–2772. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00511

- Cronqvist, H., & Nilsson, M. (2003). Agency costs of controlling minority shareholders. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38(4), 695–719. doi: 10.2307/4126740

- DeAngelo, L. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-4101(81)90002-1

- Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. (1985). The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155–1177. doi: 10.1086/261354

- Dou, Y., Hope, O.-K., Thomas, W. B., & Zou, Y. (2016). Individual large shareholders, earnings management, and capital-market consequences. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 43(7–8), 872–902. doi: 10.1111/jbfa.12204

- Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (2004). Information and the cost of capital. Journal of Finance, 59(4), 1553–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00672.x

- Faccio, M., & Lang, L. H. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65(3), 365–395. doi: 10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00146-0

- Fama, E., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. doi: 10.1086/467037

- Fan, J. P. H., & Wong, T. J. (2002). Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings in East Asia. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 401–425. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00047-2

- Francis, J., Maydew, E., & Sparks, H. (1999). The role of Big 6 auditors in the credible reporting of accruals. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 18(2), 17–34. doi: 10.2308/aud.1999.18.2.17

- Fristedt, D., & Sundqvist, S. I. (2001–2009). Ägarna och Makten i Sveriges Börsföretag 2001–2009. [Ownership and Power in Swedish Listed Corporations], Stockholm: SIS Ägarservice AB.

- Gul, F. A., & Leung, S. (2004). Board leadership, outside directors’ expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 23(5), 351–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2004.07.001

- Ho, S. S. M., & Shun Wong, K. (2001). A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 10, 139–156. doi: 10.1016/S1061-9518(01)00041-6

- Hope, O.-K. (2013). Large shareholders and accounting research. China Journal of Accounting Research, 6(1), 3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cjar.2012.12.002

- Hope, O.-K., Langli, J. C., & Thomas, W. B. (2012). Agency conflicts and auditing in private firms. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 37(7), 500–517. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2012.06.002

- Institutional Shareholder Services. (2007). Proportionality between ownership and control in EU listed companies. External study Commissioned by the European Commission. Retrieved from www.ecgi.org/osov/documents/final_report_en.pdf

- Isakov, D., & Weisskopf, J.-P. (2014). Are founding families special blockholders? An investigation of controlling shareholder influence on firm performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 41, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.012

- Jaggi, B., & Leung, S. (2007). Impact of family dominance on monitoring of earnings management by audit committees: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 16(1), 27–50. doi: 10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2007.01.003

- Jaggi, B., Leung, S., & Gul, F. (2009). Family control, board independence and earnings management: Evidence based on Hong Kong firms. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 28(4), 281–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2009.06.002

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 303–431. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(76)90025-8

- La Porta, R., López-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–518. doi: 10.1111/0022-1082.00115

- La Porta, R., López-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155. doi: 10.1086/250042

- Leuz, C., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. D. (2003). Earnings management and investor protection: An international comparison. Journal of Financial Economics, 69, 505–527. doi: 10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00121-1

- Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2000). The economic consequences of increased disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 91–122. doi: 10.2307/2672910

- Li, F. (2008). Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 221–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.02.003

- Meek, G., Roberts, C. B., & Gray, S. J. (1995). Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by U.S., U. K and continental European multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 555–572. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490186

- Morck, R. K., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1988). Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20(1-2), 293–315. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(88)90048-7

- Mäki, J., Somoza-Lopez, A., & Sundgren, S. (2016). Ownership structure and accounting method choice: A study on European real estate companies. Accounting in Europe, 13, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2016.1154180

- Prencipe, A., & Bar-Yosef, S. (2011). Corporate governance and earnings management in family-controlled companies. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 26(2), 199–227. doi: 10.1177/0148558X11401212

- Prencipe, A., Bar-Yosef, S., & Dekker, H. C. (2014). Accounting research in family firms: Theoretical and empirical challenges. European Accounting Review, 23(3), 361–385. doi: 10.1080/09638180.2014.895621

- Salvato, C., & Moores, K. (2010). Research on accounting in family firms: Past accomplishments and future challenges. Family Business Review, 23(3), 193–215. doi: 10.1177/0894486510375069

- Sengupta, P. (1998). Corporate disclosure quality and the cost of debt. The Accounting Review, 73(4), 459–474.

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- SKF (2010). 2010 annual report of SKF. Retrieved from http://www.skf.com/irassets/afw/files/press/skf/SKF_ar_2010_en.pdf

- Sundqvist, S.-I. (2010). Ägarna och makten i Sveriges Börsföretag. [Ownership and Power in Swedish Listed Corporations], Stockholm: SIS Ägarservice.

- Verrecchia, R. (2001). Essays in disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 97–180. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00025-8

- Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.12.005

- Wan-Hussin, W. N. (2009). The impact of family-firm structure and board composition on corporate transparency: Evidence based on segment disclosures in Malaysia. International Journal of Accounting, 44(4), 313–333. doi: 10.1016/j.intacc.2009.09.003

- Wang, D. (2006). Founding family ownership and earnings quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(3), 619–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679X.2006.00213.x

- Watts, R. L., & Zimmerman, J. (1986). Positive Accounting Theory. London: Prentice-Hall.

- Weiss, D. (2014). Internal controls in family-owned firms. European Accounting Review, 23(3), 463–482. doi: 10.1080/09638180.2013.821814

- Yang, M. L. (2010). The impact of controlling families and family CEOs on earnings management. Family Business Review, 23(3), 266–279. doi: 10.1177/0894486510374231

- Laws and regulations

- Swedish Corporate Governance Code. (2016). The Swedish Code of Corporate Governance. The Swedish Corporate Governance Board, Stockholm: Kollegiet för Svensk bolagsstyrning.

- Swedish Company Act (Aktiebolagslagen). (2005: 551). Retrieved from http://www.notisum.se/Rnp/SLS/lag/20050551.htm