ABSTRACT

In recent years, sustainability disclosure has increasingly become mandatory in many countries. The European Union (EU) is at the forefront of this change by adopting legislation that governs disclosure of (i) companies’ sustainability aspects (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive), (ii) the sustainability of economic activities (Taxonomy Regulation), (iii) the sustainability of financial products (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation), and (iv) the environmental, social and governance risks of credit institutions (Pillar 3 disclosures). In addition, international standard setting for sustainability disclosure is at a rapid pace, and both the International Sustainability Standards Board and the European Commission have published reporting standards. Overall, these reporting mandates and standards are interconnected and rapidly progressing, which makes it increasingly difficult to keep track. The aim of this article is to outline and compare the EU’s sustainability disclosure legislation and major standard-setting initiatives and thus identify important implications for both researchers and practitioners.

1. Introduction

The 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations in 2015 marked a turning point in societal awareness of the challenges of climate change and sustainable development. In March 2018, the European Commission introduced an ‘Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth’ (European Commission, Citation2018) in response to the recommendations of the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (EU High-Level Expert Group, Citation2018). The action plan comprises ten key actions that can be grouped into three broad categories: (i) reorientate capital flows toward a more sustainable economy, (ii) integrate sustainability into risk management, and (iii) foster sustainability disclosure and sustainable mechanisms of corporate governance. In December 2019, the European Commission introduced the ‘European Green Deal’, a set of policy actions that intend to make Europe climate neutral by 2050 (European Commission, Citation2019a). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in May 2020, the European Union (EU) announced a EUR 750 billion recovery package, of which the European Green Deal is an integral part.Footnote1 In line with the European Green Deal, in July 2021, the European Climate Law entered into force (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2021); this mandates member states to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Consistent with these developments, sustainability disclosure legislation is also evolving. The starting point for an EU sustainability reporting mandate was the Non-Financial Reporting Directive, known as the NFRD (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2014), which the EUFootnote2 adopted in 2014. The NFRD mandated the disclosure of nonfinancial information, including information on diversity, for large EU-based public-interest companies with more than 500 employees, effective from the financial year 2017.Footnote3 Other EU sustainability disclosure mandates followed the NFRD, including the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2019a), which requires that participants in financial markets and financial advisers disclose specific information on sustainability risks, the Taxonomy Regulation (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2020), which introduces a system for classifying environmentally sustainable economic activities, and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) II (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2019b), which incorporates climate-related risk disclosure standards within its Pillar 3 (i.e. regulatory disclosure requirements for certain large credit institutions). Moreover, in November 2022, the EU in 2022 adopted the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2022), which supersedes the NFRD from financial year 2024 onwards. The CSRD substantially increases the number of companies in scope of a sustainability reporting mandate and introduces more detailed reporting requirements, including the obligation to report in accordance with European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), the integration of sustainability information in the management report, an external assurance requirement, and digital tagging of the reported information. The first set of ESRS was adopted by the European Commission as delegated acts in July 2023 (European Commission, Citation2023d).

In parallel with these developments, at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference in November 2021 (COP26), the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation announced the establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), dedicated to developing the IFRS sustainability disclosure standards, and the consolidation of the IFRS Foundation with the Value Reporting Foundation (VRF) and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB). In June 2023, the ISSB published general requirements for the disclosure of sustainability-related financial information (IFRS S1) and climate-related disclosures (IFRS S2) (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023a).

The rapid pace of developments in sustainability reporting in the EU and the diversity in the underlying objectives and requirements makes it increasingly difficult for both decisionmakers in organizations and researchers to keep track of changes in legislation and reporting standards. Stolowy and Paugam (Citation2023) discuss the future of sustainability reporting. They find heterogeneity in the understanding of sustainability across standard-setters and companies and conclude that the probability of convergence in future sustainability reporting is low. Similarly, Baboukardos et al. (Citation2023) observe a ‘multiverse’ of sustainability reporting requirements. This ‘multiverse’ makes it increasingly difficult for researchers and practitioners to keep track. Against this background, this paper thus summarizes and contrasts the above-mentioned developments to help practitioners and researchers better understand them. Consequently, the aim of this article is to provide an overview of sustainability disclosure legislation and standards at the EU level and to compare and systematically discuss their key characteristics. Naturally, this overview is provided at the time of writing this article (December 2023) and cannot account for developments thereafter. Our starting point is the adoption of the NFRD, and we do not elaborate on national sustainability reporting requirements that preceded the adoption of the NFRD.Footnote4 We provide references to useful sources so that readers can more easily access detailed information on specific topics. In addition, we facilitate the overview of legislation and standards beyond the publication of this articleFootnote5 with an openly accessible and regularly updated register of regulatory developments in sustainability reporting in the EU.Footnote6

The article is structured as follows. In the next section, we briefly review the theory and literature on mandatory sustainability disclosure. Section 3 focuses on sustainability disclosure legislation. We start with a brief depiction of the NFRD, followed by a discussion of the CSRD, the Taxonomy Regulation, the SFDR, and the requirements of Pillar 3 on the disclosure of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks. Section 4 focuses on sustainability reporting standards: the GRI Standards, the ESRS, and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. Section 5 provides implications for practitioners and future research avenues. The final section concludes.

2. Theory and Literature

Economics-based theory suggests that companies voluntarily provide information as long as the benefits of disclosure exceed the costs (Verrecchia, Citation1983). Corporate disclosure reduces information asymmetries both among investors and between managers and shareholders. In turn, lower information asymmetry decreases estimation risk and increases market liquidity and the company’s investor base (Leuz & Wysocki, Citation2016). Additional capital-market effects associated with voluntary disclosures include lower costs of capital and higher coverage by financial analysts (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). In recent decades, a substantial body of empirical studies has evolved on the capital-market effects of disclosure. Valuable reviews of this literature are provided, for instance, by Healy and Palepu (Citation2001), Holthausen and Watts (Citation2001), Beyer et al. (Citation2010), Berger (Citation2011), and Leuz and Wysocki (Citation2016).

Researchers often apply this rationale to the disclosure of sustainability information. Thus, companies have an incentive to disclose sustainability information voluntarily as long as the marginal benefits of disclosure exceed its marginal costs. Following this rationale, reporting mandates impact these cost–benefit considerations by inducing additional costs. These costs include direct costs of preparation, certification, dissemination, and noncompliance and indirect costs resulting from the negative impact of revelation of proprietary information to competitors or litigation costs (Admati & Pfleiderer, Citation2000; Christensen et al., Citation2021; Leuz & Wysocki, Citation2016). The level of compliance thus depends on these costs, which are determined by the specification of the legislation, in particular how precisely the reporting requirements are outlined, the magnitude of potential sanctions for noncompliance, and the likelihood of detection and enforcement (Peters & Romi, Citation2013). Legitimacy theory offers another explanation for voluntary sustainability reporting among companies. Legitimacy can be defined as a ‘generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’ (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). According to legitimacy theory, companies voluntarily provide sustainability information to gain, maintain, or repair their legitimacy (O’Donovan, Citation2002). Empirical evidence suggests that companies with poor sustainability performance provide positive sustainability disclosure to influence public perceptions of their underlying sustainability performance (e.g. Cho et al., Citation2010; Cho et al., Citation2012; Cho & Patten, Citation2007; Hummel & Schlick, Citation2016; Patten, Citation2002). In that context, researchers assert that the disclosure of sustainability information is often ‘partial, and, mostly, fairly trivial’ (Cho et al., Citation2015; Gray, Citation2006, p. 803). Such reporting behavior is closely linked to so-called greenwashing, which is characterized by hiding negative actions through positive reporting (Christensen et al., Citation2021). Consequently, sustainability reporting mandates are needed ‘to transform [sustainability] reporting into a tool of transparency and accountability’ (Patten, Citation2014, p. 212). Researchers argue that only clearly specified sustainability reporting mandates in combination with rigid sanctioning and enforcement can ensure the transparency and accountability of sustainability information (Laine et al., Citation2022; Patten, Citation2014).

Therefore, according to both theories, sustainability reporting mandates can lift the quantity and/or quality of sustainability information (Christensen et al., Citation2021; Jeffrey & Perkins, Citation2014; Patten, Citation2014). However, to prevent legitimacy-driven reporting practices, such reporting mandates need to be detailed and specific, entail severe sanctions for noncompliance, and be strictly enforced.Footnote7 Assurance also plays an important role because it can increase the quality and reliability of the information disclosed (Ballou et al., Citation2018; Maroun, Citation2019). Furthermore, assurance can prevent legitimizing reporting strategies, thus helping ensure the functioning of markets and improving confidence in the accuracy of sustainability reporting.

Recent reviews of archival studies on mandatory sustainability reporting find ambiguous evidence on the consequences of sustainability reporting mandates and call for further research to better understand the mechanisms underlying how sustainability reporting mandates translate into changes in reporting, capital-market consequences, and real effectsFootnote8 (Christensen et al., Citation2021; Haji et al., Citation2023). The overview of sustainability reporting mandates in the next section provides a starting point for both quantitative and qualitative researchers to examine these consequences in more detail.

3. Sustainability Reporting Legislation

In this section, we outline five sustainability reporting mandates that have been adopted in the EU since 2014: the NFRD, the CSRD, the Taxonomy Regulation, the SFDR, and the Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks. We discuss these mandates with a focus on companies in scope, objectives, disclosures required, and timeline of implementation. The chapter concludes with a comparison of the discussed mandates and a critical reflection.

3.1. Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD)

In September 2014, the EU adopted the NFRD (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2014), which amended the Accounting Directive (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2013a) and required the disclosure of nonfinancial and diversity information by large companies (and parent companies of groups) that are public interest entities (PIEs) with an average number of more than 500 employees (on a consolidated basis in the case of groups).Footnote9 According to the NFRD, its objective was to ‘increase the relevance, consistency and comparability of information disclosed by certain large companies and groups across the Union’ on nonfinancial and diversity topics (Recital 21) and to stimulate ‘change toward a sustainable global economy’ (Recital 3).

The NFRD extended the scope of management reports and required the inclusion of a nonfinancial statement encompassing the development, performance, position, and impact of activities related to at least the following areas:Footnote10,Footnote11 the environment, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, and anticorruption and bribery matters. Moreover, for EU companies traded on an EU regulated market, the NFRD extended the scope of the corporate governance statement, as defined in Article 20 of the Accounting Directive, to also contain diversity information.

The NFRD first became applicable for financial years starting on 1 January 2017 or during the calendar year 2017. The NFRD also had to be transposed into national legislation by each member state and Article 4 of the NFRD provided some discretion to member states in the transposition. We provide an overview of differences in national transpositions in the appendix (). Further nonbinding reporting guidelines were published by the European Commission in 2017 (methodology for reporting nonfinancial information; European Commission, Citation2017) and 2019 (supplement on reporting climate-related information; European Commission, Citation2019b). The guidelines detailed the concept of double materiality, thereby emphasizing that companies need to consider not only financial materiality but also its impact on people and the environment when defining reporting content.

3.2. Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

The NFRD was repeatedly criticized for deficiencies regarding comparability, consistency, and reliability of the information it requires and the limited number of companies in scope (European Commission, Citation2021e; La Torre et al., Citation2018; Mittelbach-Hörmanseder et al., Citation2021).Footnote12 These shortcomings paved the way for a substantial revision of the NFRD. In April 2021, the European Commission published a proposal for a new CSRD (European Commission, Citation2021d).Footnote13 A provisional agreement on the new requirements was reached in June 2022, and the CSRD was eventually adopted in November 2022 and published in the Official Journal of the EU in December 2022 (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2022). Compared to the NFRD, the main changes include an extension of the companies in scope, an extension of the reporting requirements for a company’s value chain, further specifications of the double materiality concept and reporting contents, requirements for the integration of sustainability information in the management report, the assurance and digital tagging of the information reported, and requirements for the sanctioning regime for statutory auditors and enforcement. In addition, the CSRD delegates the development of sustainability reporting standards to the European Commission, which, in turn, needs to consider technical advice from the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). The CSRD was adopted in November 2022 with the following phased-in application:

first reporting in 2025 covering the financial year 2024 by companies already subject to the NFRD (see section 3.1)

first reporting in 2026 covering the financial year 2025 by other large companies

first reporting in 2027 covering the financial year 2026 (with the ability to opt-out for another two years) by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) listed on EU regulated markets,Footnote14 small and noncomplex credit institutions,Footnote15 and captive (re)insurance undertakings,Footnote16 but excluding microenterprises.

In addition, from financial year 2028 onwards, EU branches and subsidiaries of non-EU undertakings are also subject to the CSRD if the non-EU undertaking has a net turnover of EUR 150 million in the EU for each of the last two consecutive years and either a large or listed EU subsidiary or an EU branch with a net turnover of at least EUR 40 million (Article 1, paragraphs 1, 4, 7, 14; Article 2, paragraph 2; Recitals 17–27).Footnote17

3.2.1. Double Materiality

The CSRD further clarifies the requirement of the double materiality concept (Article 1, paragraphs 4 and 7; Recital 29), which had already been introduced by the NFRD.Footnote18 The double materiality concept combines two perspectives. Financial materiality provides the outside-in perspective on the impact of sustainability issues on a company’s performance, position, and development. Impact materiality provides the inside-out perspective on the impact of the company on people and the environment. The CSRD specifies that ‘undertakings should consider each materiality perspective in its own right, and should disclose information that is material from both perspectives as well as information that is material from only one perspective’ (Recital 29).Footnote19

3.2.2. Reporting Content and Standards

Compared to the NFRD, the reporting content is extended and includes the following (Article 1, paragraphs 3, 4 and 7; Recitals 30-36):

a description of the company’s business model and strategy, particularly for sustainability matters;

a description of time-bound sustainability-related targets, including potential GHG emission reductions, a description of progress made to achieve these targets, and specification of whether the targets are based on scientific evidence;

a description of the role of administrative, management, and supervisory bodies in sustainability matters and their expertise and skills or access to these to fulfill this role;

a description of the company’s sustainability-related policies;

information about existing sustainability-linked incentive schemes for members of the administrative, management, and supervisory bodies;

a description of the due diligence processes, the principal actual or potential adverse impacts in the company’s own operations and ‘value chain,’ actions taken to identify and track these impacts, and actions to mitigate these adverse impacts;

a description of sustainability-related risks and how these risks are managed; and

indicators relevant to the disclosures of these issues.

In addition, companies need to provide information on key intangible resources, which are nonphysical resources that are fundamental to the business model and add to value creation. The CSRD highlights the consideration of the company’s complete value chain in the disclosure, including own operations, business relationships, and the supply chain and requires that in the case of information gaps on the value chain during the first three years of application, companies should disclose their efforts, reasons, and plans for obtaining missing information.

The CSRD prescribes the adoption of sustainability reporting standards based on delegated acts and technical advice provided by the EFRAG (Article 1, paragraphs 4, 7, 8, 14 and 17; Recitals 37-54). These delegated acts are to be adopted sequentially. A first set of sector-agnostic standards was adopted by means of a delegated act by the Commission (European Commission, Citation2023d) in July 2023. Further delegated acts shall be adopted by the end of June 2024 to define sector-specific standards, proportionate standards for listed SMEs, and standards for third-country companies in scope of the CSRD. The ESRS are described in more detail in section 4.2.

3.2.3. Reporting Location, Format, and Assurance

The CSRD requires the inclusion of sustainability information in the management report (Article 1, paragraphs 4 and 7; Recital 57); providing the necessary disclosure under the CSRD in a separate sustainability report is therefore no longer possible. In addition, sustainability information should be prepared and marked up in an electronic reporting format (Article 1, paragraphs 9 and 10; Recitals 55-56).

The CSRD prescribes limited assurance on the company’s sustainability reporting, including compliance with the reporting standards, the process for identifying the information reported, the mark-up of sustainability reporting, and the reporting requirements detailed in Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation. The assurance can be carried out by the statutory auditors. Furthermore, member states can define whether auditing firms other than the ones carrying out the statutory audit of financial statements or independent assurance service providers are also allowed to provide assurance on sustainability reporting.Footnote20 The European Commission shall also adopt standards for limited assurance by October 2026 (Article 1, paragraphs 12 and 13; Article 3 and Article 4; Recitals 60–78). Moreover, the CSRD foresees a potential transition to reasonable assurance based on a preceding assessment of its feasibility for auditors and undertakings. If that assessment is positive, the European Commission shall adopt applicable standards for reasonable assurance by October 2028, including a date by which reasonable assurance has to be performed.

3.3. Taxonomy Regulation

In June 2020, the EU adopted the Taxonomy Regulation (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2020), which provides a classification system for environmentally sustainable economic activities. It was proposed as part of the EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth (European Commission, Citation2018), which aims to redirect capital flows toward a more sustainable economy. Thus, the Taxonomy Regulation applies to policy measures targeting sustainable financing activities, financial market participants within the scope of the SFDR, and companies subject to the NFRD and the CSRD (Article 1). The Taxonomy Regulation differs from other sustainability reporting mandates, such as the NFRD and the CSRD, first because it provides a classification system to define which economic activities qualify as environmentally sustainable and second because it requires companies to report on their activities based on this classification.

The classification of the Taxonomy Regulation is organized around six environmental objectives (Article 9):

climate change mitigation,

climate change adaptation,

the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources,

the transition to a circular economy,

pollution prevention and control, and

the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

Each environmental objective is delineated in greater detail in Articles 10–15. The Taxonomy Regulation defines three conditions that an economic activity must meet to qualify as environmentally sustainable (Article 3), also referred to as ‘taxonomy-aligned’:

the activity must substantially contribute to meeting at least one of the six environmental objectives (SC criteria),

the activity does not significantly harm meeting any of the six environmental objectives (DNSH criteria), and

the activity is carried out in compliance with minimum safeguards.

These conditions are further delineated in Articles 16–18. For instance, the condition of ‘substantial contribution’ requires a ‘substantial positive environmental impact, on the basis of life-cycle considerations’ (Article 16); for a lack of ‘significant harm’ to meet any of the six environmental objectives, such damage is defined for each environmental objective (Article 17). The technical screening criteria that an economic activity must meet for the SC and the DNSH criteria are defined in the delegated regulations for climate change mitigation (Annex I) and climate change adaptation (Annex II) (European Commission, Citation2021b)Footnote21, and for sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources (Annex I), the transition to a circular economy (Annex II), pollution prevention and control (Annex III), and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems (Annex IV) (European Commission, Citation2023c). Moreover, a separate delegated regulation was adopted to define criteria for fossil gas and nuclear energy sectors (European Commission, Citation2022b).

The minimum safeguards require that activities are, for example, aligned with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights must be ensured (Article 18). Another delegated regulation specifies the content and presentation of the information (European Commission, Citation2021a).Footnote22

The Taxonomy Regulation distinguishes between taxonomy-eligible and taxonomy-aligned economic activities. An economic activity is taxonomy eligible if it is listed in the annexes of the delegated regulations that defines the technical screening criteria. Taxonomy alignment further requires adherence to the SC and DNSH criteria and the minimum safeguards. To meet the reporting requirements, nonfinancial companies must disclose the proportion of their turnover, capital expenditures (capex), and operating expenditures (opex) associated with environmentally sustainable activities (Article 8). Further information needs to be provided on the description and classification of the economic activities, the composition of the numerators and denominators of the KPIs, the link to the financial reporting, the comparison with previous years’ KPIs, and on how double counting is avoided. Financial companies must report KPIsFootnote23 that reflect their financing, investment, and insurance activities towards environmentally sustainable activities and certain qualitative information to facilitate understanding of the reported KPIs (European Commission, Citation2021a).

The Taxonomy Regulation does not need to be transposed into the national law of EU member states. Companies in the scope of the Taxonomy Regulation must apply it in their reporting since January 2022, covering financial year 2021 onward, with a gradual phasing in.Footnote24 The European Commission describes the Taxonomy Regulation as a ‘living document’ that will evolve over time. In particular, the technical screening criteria will be reviewed regularly to account for technological progress (European Commission, Citation2021g). Furthermore, the EU provides administrative support with a taxonomy compass, taxonomy calculator, and taxonomy FAQs.Footnote25

3.4. Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)

In November 2019, the EU adopted the SFDR (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2019a) with the aim of increasing transparency about the sustainability of financial productsFootnote26 and strengthening investor protection. Along with the Taxonomy Regulation, the SFDR forms an integral part of the EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth (European Commission, Citation2018). The SFDR applies to financial market participants (e.g. credit institutions and investment firms providing portfolio management) and financial advisers (e.g. credit institutions and investment firms providing investment advice) and introduces harmonized disclosure rules in the EU on the sustainability of financial products (Recital 9). Hence, the disclosure requirements of the SFDR are closely focused on investment products and services and target the mechanisms for financing a transition to a more sustainable economy. The SFDR has gradually been phased in, with the first disclosure requirements being effective since 10 March 2021. provides an overview of the disclosure requirements.

Table 1. Overview of the SFDR disclosure requirements.

The SFDR distinguishes between disclosure requirements for entities and for products. At the entity level, financial market participants and financial advisers have to provide website disclosure on their policies for integrating sustainability risksFootnote27 in investment processes or financial advice, the consideration of principal adverse impacts (PAIs) in investment decisions or financial advice,Footnote28 and the consideration of sustainability risks in their remuneration policies.

In addition to the disclosure requirements for entities, the SFDR stipulates precontractual,Footnote29 website, and periodic disclosures for product information on sustainability aspects. The SFDR distinguishes two types of sustainable investment products:

financial products that promote environmental or social characteristics (Article 8),Footnote30 and

financial products with sustainable investment objectives (Article 9).Footnote31

For all types of financial products, regardless of whether they address sustainability according to Article 8 or Article 9 or not, precontractual disclosures need to include information on the integration of sustainability risks into investment decisions or investment/insurance advice as well as an assessment outcome of the likely impacts of sustainability risks on the financial returns of financial products, on a comply-or-explain basis (Article 6). Furthermore, since 30 December 2022, financial market participants that consider PAIs at entity level are required (Article 7) to explain if and how financial products consider the PAIs of investment decisions on sustainability factors and a statement that information on PAIs is available in the periodic reporting. Regarding Article-8 investment products, information on how the environmental and social characteristics are met needs to be provided. Regarding Article-9 investment products, disclosure is required on how the objective is to be met.Footnote32

In addition, the SFDR imposes certain disclosure requirements for financial market participants’ websites (Article 10) and periodic reports (Article 11) regarding the consideration of PAIs (Article 7) as well as investment products defined according to Article 8 and Article 9. Article 10 requires a description on the website of the environmental and social characteristics or objectives and information on the methodologies applied to measure these characteristics or the impact of the investments. Furthermore, the information in precontractual disclosures and in periodic reporting required for Article-8 and Article-9 products must be provided on the website. Starting with the reporting year 2022, periodic reporting (Article 11) needs to include any information on PAIs considered, the extent of alignment with environmental and social characteristics for Article-8 products and the overall sustainability-related impact for Article-9 products. Moreover, financial market participants and financial advisers need to ensure that there is no contradiction between their marketing communications and their disclosures according to the SFDR (Article 13). Further information on the degree of alignment of the investment products with the Taxonomy Regulation objectives and activities must be provided in the precontractual disclosures and in periodic reports if products focus on environmental characteristics (Article 8) or objectives (Article 9).

In April 2022, the European Commission adopted a delegated regulation on regulatory technical standards (RTS) specifying the details of the content, methodologies, and presentation of disclosures (European Commission, Citation2022a).Footnote33 These standards apply from 1 January 2023. Another delegated regulation, adopted in October 2022 and applicable from February 2023, stipulates disclosures for the exposure of financial market participants to the fossil gas and nuclear energy sectors as defined by the Taxonomy Regulation (European Commission, Citation2023a). However, in 2023, the European Commission called for a review of the RTS to broaden the disclosure framework and to address technical issues (EBA, EIOPA & ESMA, Citation2023a) and a proposal for changes to the RTS was provided by EBA, EIOPA and ESMA (Citation2023b) in December 2023. Moreover, at the time of writing this article (December 2023) a public consultation by the European Commission is taking place to assess potential shortcomings of the SFDR (European Commission, Citation2023e).

3.5. Pillar 3 Disclosures on ESG Risks

In May 2019, the EU adopted the CRR II (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2019b), which amends the original CRR (European Parliament and Council of the EU, Citation2013b) and takes into account the reform measures of the Basel Committee of Banking Supervision (BCBS)Footnote34 regarding its Pillar 3 disclosure requirements to promote market discipline.

The CRR II amends Part Eight of the original CRR and introduces Article 449a, which requires large institutions (i.e. credit institutions and certain investment firms)Footnote35 with issued securities publicly listed on a regulated EU market to disclose their ESG risks from the end of June 2022. Hence, in contrast to the CSRD, the Taxonomy Regulation, and the SFDR, the sustainability-related disclosures required under Pillar 3 focus particularly on risks.

To specify uniform disclosure formats and instructions, the European Commission adopted implementing technical standards (ITS) in November 2022 (European Commission, Citation2022c) based on a draft developed by the EBA. The ITS contain templates, tables, and detailed disclosure instructions for both quantitative and qualitative disclosure requirements. The quantitative disclosures relate to climate-change transition risks, climate-change physical risks, and institutions’ mitigation actions, in particular the GAR required by the Taxonomy Regulation and the Banking Book Taxonomy Alignment Ratio (BTAR).Footnote36 The qualitative disclosures focus on how governance arrangements, business strategy and processes, and risk management consider risks in each ESG dimension. According to the EBA, the ITS will be developed further to integrate the developments of the technical screening criteria for the environmental objectives other than climate change mitigation and adaptation according to the Taxonomy Regulation (EBA, Citation2022).

The disclosure requirement under Article 449a of the CRR II started in June 2022 and required a first annual disclosure for the financial year 2022.Footnote37 However, to account for challenges in data collection, several disclosure requirements were phased in, including disclosures on institutions’ financed GHG emissions, for which the reference date was set to end of June 2024. Moreover, the reference dates for first disclosures of information for the GAR and the BTAR were set to end of December 2023 and December 2024, respectively.

3.6. Discussion

3.6.1. Comparison

provides an overview of the key characteristics of the CSRD, the Taxonomy Regulation, the SFDR and the Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks.

Table 2. Overview of regulatory initiatives.

The sustainability disclosure mandates are evidently interconnected. The CSRD and the Taxonomy Regulation all apply to a broad range of EU companies, and the CSRD and therefore also the Taxonomy Regulation are also relevant to certain non-EU companies. In contrast, the SFDR and the Pillar 3 disclosures of ESG risks target participants in financial markets and large banks, respectively. They also seek to induce ‘real’ effects on the sustainability performance of the companies within their scope. Additionally, the Taxonomy Regulation aims to prevent greenwashing, the SFDR aims to stimulate sustainable financing and investment and improve investor protection, and the Pillar 3 disclosures of ESG risks aim to promote market discipline. The SFDR focuses only on investors, whereas the CSRD, the Taxonomy Regulation and the Pillar 3 disclosures address a broad range of stakeholders including non-financial stakeholders (e.g. employees, customers, etc.).

The CSRD, and the SFDR cover all matters of sustainability, whereas the Taxonomy Regulation in its current version focuses exclusively on environmental sustainability in the reporting, and the Pillar 3 disclosures embrace the ESG concept, which is prominent in the financial sector. Reporting requirements on environmental aspects across all mandates refer to the classification system of the Taxonomy Regulation.Footnote38 In particular, the ESRS are required to align with the Taxonomy Regulation (CSRD, Recital 38), and specific disclosure requirements under the SFDR and Pillar 3 directly build on classifications according to the Taxonomy Regulation. The classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities introduced by the Taxonomy Regulation therefore provides an overarching framework for reporting on sustainability and aims to address the need for uniform criteria for environmental sustainability across the EU. Its classification scheme links the reporting requirements imposed on the financial market by the SFDR and Pillar 3 disclosures with the reporting requirements in the real economy (through the CSRD). In addition, the ESRS are also aligned to meet certain data requirements for disclosures under Pillar 3 and under the SFDR (see Appendix B of ESRS 2).

The Taxonomy Regulation does not embrace the concept of materiality, whereas the CSRD, the SFDR and the Pillar 3 disclosuresFootnote39 employ the double materiality concept. All mandates stipulate granular and specific reporting requirements directly or indirectly through sustainability reporting standards. In particular, similar to the SFDR and the reporting requirements of Pillar 3, the Taxonomy Regulation also stipulates the disclosure of specific KPIs. In addition, for every mandate more detailed reporting requirements are provided in specific legal acts adopted by the European Commission. The CSRD refers to the ESRS adopted by a delegated regulation, and the disclosure requirements for the Taxonomy Regulation are also laid out in a separate delegated regulation. Similarly, technical standards were adopted by the Commission regarding the disclosures under the SFDR and Pillar 3.

Moreover, reporting requirements differ significantly for financial and nonfinancial companies. In particular, although the CSRD and the Taxonomy Regulation are relevant across sectors, the Pillar 3 disclosures and the SFDR apply only to specific companies in the financial industry.

All these mandates except the CSRD are directly legally applicable, thus providing no discretion to the member states in their implementation of disclosure requirements and ensuring regulatory consistency throughout the EU. Most mandates also become effective almost immediately after their publication, which highlights the urgency with which EU legislators have approached the regulation of sustainability disclosure.

3.6.2. Critical Reflection

Generally, all mandates are supplemented by delegated and/or implementing acts by the European Commission to prevent those mandates from being overloaded with technical specifications and requirements. Although this addition of further technical specifications is explicitly stipulated by the mandates, it eventually enables the European Commission to exert a great deal of influence. The drafting of these legal acts is typically carried out by technical expert groups or committees, which, unlike the European legislators, have the necessary expert knowledge. Because these entities are not elected parliamentary representatives and to limit the risk of lobbying, it is important to ensure that the process for developing those drafts is transparent. In addition, the composition of these expert groups needs to be balanced to ensure a broad stakeholder perspective. These entities only provide a draft of the delegated act, whereas the final delegated act that is passed by the European Commission does not necessarily implement the suggestions one-to-one.

For instance, the delegated act finally adopted by the European Commission in July 2023 differs from the draft ESRS provided by EFRAG in November 2022. Specifically, the European Commission made three major modifications to the draft ESRS: phasing-in certain reporting requirements for companies with less than 750 employees, making all reporting requirements of the topical standards subject to the outcome of the double materiality assessmentFootnote40, and converting some of the mandatory reporting requirements into voluntary. In light of the tight implementation period, companies are challenged by the need to prepare for reporting according to the ESRS against the background of changing draft legislations. In particular, the short implementation period can be criticized for all the mandates under study. Recently, Hummel and Bauernhofer (Citation2024) concluded that complex and detailed reporting requirements in combination with a tight implementation period result in a reporting response in the first implementation years they describe as an ‘endeavor to comply’; companies aim to comply with reporting requirements, but have not yet assembled the reporting processes and systems needed.

Several critical points can be raised about specific mandates, particularly the CSRD. First, the CSRD extends the number of companies in scope of a sustainability reporting mandate substantially, from approximately 11,700 companies in scope of the NFRD to about 50,000 companies (European Commission, Citation2023f) and the additional reporting burden may be disproportionate, particularly for SMEs in scope, in light of their sustainability impact. Although the CSRD provides reduced reporting requirements for those SMEs, a proposal for proportionate ESRS for listed SMEs has not been published at the time of writing this article (December 2023). These standards will decide whether the EU will find an acceptable balance between reporting burden for listed SMEs and the information needs of other stakeholders. Furthermore, SMEs’ sustainability disclosures are needed by other companies in the value chain to fulfill their own reporting requirements. Another critical point concerns the reporting obligation for non-EU companies. Importantly, CSRD reporting covers the company at a consolidated level and not only the EU-based subsidiary or branch. There will be specific sustainability reporting standards for non-EU companies, but these standards have not been developed at the time of writing this article (December 2023). Furthermore, the CSRD also provides the option of reporting in accordance with standards that are deemed to be equivalent, yet it is unclear on what basis this equivalence will be defined. Another critical point concerns the assurance of sustainability information. Although financial and sustainability information are becoming more integrated (also due to the CSRD’s requirement to report the sustainability information in the management report), it is currently unclear how responsibilities will be shared between the statutory auditor and the assurance provider.

The Taxonomy Regulation takes a rather novel and innovative approachFootnote41 that combines a classification system for environmental sustainability with reporting requirements. Although the clear definition of sustainability for economic activities provides guidance to companies and has the potential to limit greenwashing, this guidance becomes questionable in light of the power that lobbying has played in the regulatory development of the Taxonomy Regulation.Footnote42 However, the practical implementation of the Taxonomy Regulation is challenging and resource intense due to the detailed definitions of technical screening criteria. Moreover, not all industries are currently covered by the Taxonomy Regulation. Since economic activities that are not taxonomy eligible – by definition – cannot be taxonomy aligned, someone who is not familiar with the Taxonomy Regulation might assume that companies operating in industries not currently covered by it are ‘unsustainable’. To overcome these shortcomings, the Platform on Sustainable Finance has recommended an extension of the current binary classification into a traffic-light system (Platform on Sustainable Finance, Citation2022). Such an extended taxonomy would cover all economic activities and categorize them into green for substantial contributions to environmental sustainability, amber for intermediate environmental performance, red for unsustainable performance, and grey for low or neutral environmental impact. However, this would substantially increase companies’ costs of implementing the reporting requirements.

The SFDR targets firms that provide or advise on financial products and thus focuses particularly on product disclosures as a means for increasing transparency about sustainable investment opportunities. To fulfill the SFDR’s disclosure requirements, reporting entities also need to categorize products into whether they promote environmental or social characteristics, pursue a sustainable investment objective, or fall into neither of those categories (see section 3.4). However, the primary focus of the SFDR on defining transparency requirements rather than setting technical boundaries for those product categories, has led to rather broad product criteria (Eurosif, Citation2022). Cremasco and Boni (Citation2022) found evidence that investment funds exhibit a degree of fuzziness in their category memberships, suggesting loose boundaries and a potential need for adapting the SFDR to better fulfill its aim.Footnote43 Moreover, disclosures in line with the SFDR are rather complex and extensive. As noted by Eurosif (Citation2022), the technical details that are required by the SFDR may be difficult for retail investors to understand.

A limitation of the Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks is its narrow scope: it currently only applies to large EU-listed institutions. This is remarkable given the crucial role of the banking sector in financing the transition to a more sustainable economy and considering the EU’s ambitious regulatory initiatives on sustainability. However, the narrow scope and hence the limited effectiveness of this disclosure rule was acknowledged by the European Commission in October 2021, which plans to extend the disclosure requirement to encompass all institutions proportionally as part of a larger proposal to amend the CRR (European Commission, Citation2021f). However, this extension is still at the proposal stage, and at the time of writing this article (December 2023) it has not been decided if and when it will become effective.

4. Sustainability Reporting Standards

In this section, we outline three major sustainability reporting standards: the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards, the ESRS, and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. We discuss those three standards due to their connection to the CSRD. On the one hand, the ESRS are an integral part of the CSRD (see section 3.2). On the other hand, the ESRS also link to both, the GRI Standards and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards.Footnote44 We discuss each set of standards in more detail in sections 4.1–4.3 and provide a systematic comparison and critical reflection at the end of this section.

4.1. GRI Standards

4.1.1. Institutional Arrangement

Founded in 1997, the GRI was among the first organizations to provide universal guidelines for sustainability reporting. The first version of the GRI guidelines was published in 2000, with continuous updates in subsequent years. In 2014, the GRI set up a new governance structure, the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB), which is responsible for setting sustainability reporting standards. In 2016, the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards were launched to set the first global standards for sustainability reporting. In October 2021, the GSSB launched a major update, of the GRI Universal Standards, which became effective starting in 2023. The GRI Standards, or prior versions of them, are currently the most commonly used sustainability reporting standards worldwide. In 2022, 78 percent of the 250 largest global companies and 68 percent of the largest 100 companies across 58 countries reported in accordance with the GRI Standards (KPMG, Citation2022).

4.1.2. Scope and Structure of the Standards

The GRI Standards have a modular structure comprising three sets of standards: the GRI Universal Standards, the GRI Topic Standards, and the GRI Sector Standards. The GRI Universal Standards consist of GRI 1: Foundation 2021, GRI 2: General Disclosures 2021, and GRI 3: Material Topics 2021. GRI 1 outlines the purpose of the GRI Standards and defines four key concepts and eight reporting principles. It also specifies the scope of reporting, distinguishing between reporting ‘in accordance with the GRI Standards’ and reporting ‘with reference to the GRI Standards.’Footnote45 GRI 2 specifies disclosures of the reporting organization’s structure, activities and workers, governance, strategy, policies, practices, and stakeholder engagement. Stakeholders are defined as ‘individuals or groups that have interests that are affected or could be affected by an organization’s activities’ (GSSB, Citation2021, p. 12). It also specifies how to report on restatements of information and external assurance provided. GRI 3 outlines the standards’ concept of materiality and describes the process for determining material topics. Material topics are defined as those ‘that represent the organization’s most significant impacts on the economy, environment, and people, including impacts on their human rights’ (GSSB, Citation2021, p. 30). Thus, the GRI Standards focus exclusively on impact materiality (GRI, Citation2022c). The GRI Topic Standards prescribe detailed reporting requirements for all sustainability-related topics, including economic matters (GRI-20x), environmental matters (GRI-30x), and employee-related, human-rights-related, customer-related, and social matters (GRI-40x). The GRI Sector Standards indicate sector-specific disclosures for topics that are likely to be material in each sector. Sector Standards have thus far been published for the oil and gas industry, the coal industry, as well as agriculture, and aquaculture and fishing.

4.2. European Sustainability Reporting Standards

4.2.1. Institutional Arrangement

In January 2020, the European Commission announced a proposal to develop sustainability reporting standards (European Commission, Citation2020). In June 2020, the European Commission mandated Jean-Paul Gauzès ad personam to suggest changes to the governance and funding of EFRAG related to sustainability reporting and EFRAG to conduct preparatory work for the development of EU sustainability reporting standards. This work was performed by a project task force for the elaboration of possible EU nonfinancial reporting standards (PTF-NFRS)Footnote46 and was summarized in a final report providing proposals for the development of EU sustainability reporting standards (European Reporting Lab, Citation2021). In response to the suggestions made by Jean-Paul Gauzès and the PTF-NFRS, the European Commission requested that EFRAG undertake the relevant governance reforms and start with the technical work on the development of EU sustainability reporting standards. Consequently, the PTF-NFRS has been renamed the Project Task Force on European Sustainability Reporting Standards (PTF-ESRS).

In addition, in June 2021, EFRAG initiated a consultation on due process procedures for setting EU sustainability reporting standards (EFRAG, Citation2021b), and a final version of due process procedures was approved in March 2022 by EFRAG’s General Assembly (EFRAG, Citation2022a). These procedures outline the principles and oversight applied when preparing draft standards and setting agendas and standards. Moreover, in July 2021, the PTF-ESRS announced a statement of cooperation with GRI (EFRAG, Citation2021a). In March 2022, a Sustainability Reporting Board (SRB) was established within EFRAG (EFRAG, Citation2022c); the SRB is ‘responsible for all sustainability reporting positions of EFRAG including technical advice to the European Commission on draft EU sustainability reporting standards’ and composed of members representing European stakeholder organizations, national organizations, and civil society (EFRAG, Citation2022e).

In April 2022, the PTF-ESRS issued exposure drafts for a first set of European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) and initiated a public consultation process with comments to be received until the beginning of August 2022 (EFRAG, Citation2022b). In November 2022, the EFRAG SRB adopted the first set of draft ESRS and submitted them to the European Commission (EFRAG, Citation2022d). By means of a delegated act, the European Commission adopted a first set of standards in July 2023 (European Commission, Citation2023d). This delegated act also passed a subsequent two-month scrutiny during which it may have been objected by the European Parliament or the Council of the EU (European Commission, Citation2023g).

4.2.2. Scope and Structure of the Standards

The ESRS comprise three categories of standards: (i) cross-cutting standards, (ii) topical standards, and (iii) sector-specific standards. The adopted first set of ESRS consists of cross-cutting standards (ESRS 1 and ESRS 2) and topical standards (ESRS E1 to E5, ESRS S1 to S4, ESRS G1) and is sector agnostic: the standards apply to companies irrespective of which sector they operate in (European Commission, Citation2023d). A separate annex provides relevant acronyms and a glossary with definitions of terms used in the standards.

The cross-cutting standards contain general reporting requirements (ESRS 1) and general disclosures (ESRS 2). ESRS 1 also explains the standards’ double-materiality approach: an ‘impact’ means a sustainability-related impactFootnote47 of a company’s business on people or the environment (impact materiality) whereas ‘risks and opportunities’ refer to a company’s financial risks and opportunities that are generated by sustainability matters (i.e. financial materiality). According to ESRS 1.25, a materiality assessment is the starting point for disclosures on sustainability matters according to the topical standards, and AR16 of ESRS 1 also delineate the sustainability matters to be considered by a company and which are covered by the topical standards. The reporting requirements of ESRS 2 and the topical standards focus on a company’s governance, the interaction of its strategy and business model with material impacts and risks and opportunities, the management of impacts and risks and opportunities, and the use of metrics and targets.

The topical standards contain additional disclosure requirements for material sustainability topics and are divided into environmental (ESRS E1 to E5), social (ESRS S1 to S4), and governance (ESRS G1) matters. ESRS 2 requires companies to provide general information on the materiality assessment process for sustainability matters and the material impacts and risks, and opportunities. If a specific sustainability matter is assessed as material (i.e. based on double materiality) by the company, it needs to disclose information according to the topical standard for that matter.

The ESRS also connect to other EU disclosure legislation. In particular, ESRS 2 contains a list that reconciles disclosures according to the standards with certain data requirements of the SFDR and the Pillar 3 disclosures (Appendix B of ESRS 2). Moreover, references are made throughout the standards whenever disclosure requirements are related to the Taxonomy Regulation. To relieve the reporting burden on companies, certain disclosure requirements in the first set of ESRS are to be phased in (Appendix C of ESRS 1). Moreover, EFRAG set up a Q&A platform to answer technical questions on the ESRS and to support the standards’ implementation.Footnote48

4.3. IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards

4.3.1. Institutional Arrangement

In May 2020, the IFRS Foundation Trustees publicly announced to explore its role in establishing sustainability reporting standards (IFRS Foundation, Citation2020a). The starting point for the IFRS sustainability disclosure standards was in September 2020, when the IFRS Foundation Trustees published a consultation paper on sustainability reporting (IFRS Foundation, Citation2020b) in which it emphasized the need for a global framework to ensure the comparability of reporting information and for reducing the reporting complexity for companies. At the same time, five sustainability reporting standard-setters, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the GRI, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), published a ‘statement of intent to work together toward comprehensive corporate reporting’ (CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIRC & SASB, Citation2020). In November 2020, the IIRC and the SASB announced their consolidation into the Value Reporting Foundation (VRF), which was then formed in June 2021 (IFRS Foundation, Citation2021a). In April 2021, the IFRS Foundation delineated the strategic direction for the development of sustainability reporting standards (IFRS Foundation, Citation2021b). In November 2021, at the COP26, the Chair of the IFRS Foundation Trustees announced the Foundation’s consolidation with the VRF and the CDSB (IFRS Foundation, Citation2021c)Footnote49 and the establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) with the purpose of developing a ‘comprehensive global baseline of sustainability disclosures for the financial markets’ (IFRS Foundation, Citation2021c). In March 2022, the ISSB issued exposure drafts for its first proposed disclosure standards (IFRS Foundation, Citation2022b), followed by the publication of its inaugural standards in June 2023 (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023a).

4.3.2. Scope and Structure of the Standards

The IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards provide general requirements for the disclosure of sustainability-related financial information (IFRS S1) and standards on climate-related disclosures (IFRS S2), each accompanied by guidance and a basis for conclusions (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023b). The standards integrate the reporting recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)Footnote50 and the reporting concepts of the standard-setters that were consolidated with the IFRS Foundation (CDSB, SASB, and IIRC).Footnote51

IFRS S1 (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023d) outlines general reporting requirements, including the objective, scope, conceptual foundations, core content, and general requirements for judgements, uncertainties, and errors. The aim of the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards is to provide sustainability disclosure to ‘primary users of general purpose financial reporting’ (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023d, p. 6), which are defined as ‘existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors’ (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023d, p. 23). Reporting has to include material information about all sustainability-related risks and opportunities, which is in line with the definition of financial materiality in the ESRS (see also section 4.2). The disclosures are required to cover governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets following the structure of the TCFD. The conceptual foundations define principles of fair presentation, the materiality of information, and the reporting entity. The conceptual foundations also emphasize the connectivity of sustainability-related financial information with other disclosures, such as in the financial statement. The general requirements define that disclosures are to be made concurrently with the financial statement and may be included in the management commentaryFootnote52 or in a similar section within the financial report.

IFRS S2 (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023e) covers climate-related disclosures. The disclosures are to focus on climate-related physical and transition risks, and the structure of reporting follows IFRS S1. IFRS S2 requires the disclosure of cross-industry metrics and targets (including GHG emissions) and industry-based metrics and targets. The ISSB also issued guidance for industry-based disclosures based on the SASB Standards for elevenFootnote53 sectors (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023f).

As mentioned in subsection 4.3.1, the stated aim of the ISSB is to provide a global baseline for sustainability disclosure with its IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. The ISSB therefore emphasizes the standards’ compatibility with multistakeholder-focused reporting standards and additional jurisdictional disclosure requirements (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023b). To establish a potential connectivity with the GRI Standards, the IFRS Foundation for example signed a memorandum of understanding with the GRI (GRI, Citation2023a) and the ISSB also underlines its efforts to align disclosures on climate-related risks and opportunities (i.e. IFRS S2) common to those in the ESRS (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023b). Moreover, according to the ISSB companies may rely on the ESRS or the GRI Standards for disclosure of other identified sustainability-related risks and opportunities that are not covered by IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards provided that disclosures are in line with the IFRS standards’ objectives and serve the information needs of investors (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023d, Citation2023g).

4.4. Discussion

4.4.1. Comparison

provides an overview of the three standards by objective, focus, topics, materiality, location of information, and legal character.

Table 3. Overview of sustainability reporting standards.

A general comparison of the ESRS with the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards reveals key differences.Footnote54 The IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards focus primarily on investors, whereas the ESRS consider the information needs of multiple stakeholders of sustainability reporting. This narrow focus of the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards on investors’ needs and enterprise value has repeatedly been criticized by several accounting researchers for ignoring the findings of prior literature and applying an understanding of sustainability that is too narrowly focused on financial materiality (Adams, Citation2021; Adams & Mueller, Citation2022; Cho et al., Citation2022; Professors of Accounting, Citation2020).

The standards also differ in their legal character. While the GRI Standards are a voluntary framework, the IFRS Foundation co-ordinates its standard-setting activities closely with the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO)Footnote55 (IFRS Foundation, Citation2022d), which endorsed the IFRS S1 and S2 in July 2023 (IOSCO, Citation2023) as a result of which the standards may apply to companies listed on member stock exchanges in the future. In contrast, the ESRS are mandatory through the CSRD and were adopted as delegated acts.

Moreover, the standards also differ in the sustainability matters covered and the location of reporting. As indicated above, the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards currently focus mainly on climate-related information. In contrast, both the ESRS and the GRI Standards incorporate a broad spectrum of sustainability-related reporting topics. The GRI Standards allow reporting either within the annual report or in a separate sustainability report. However, there is less flexibility for reporting according to the ESRS and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. The disclosures according to the CSRD, and thus the ESRS, are required within the management report, but the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards specify the management commentaryFootnote56 or a similar report within the financial report as potential locations for sustainability disclosure. The management commentary is currently under revision by the IASB (IFRS Foundation, Citation2022c), and therefore, the role that it might play for sustainability disclosure is still unclear at the time of writing this article (December 2023). However, the IASB also gathered public feedback on its proposed revision, and several stakeholdersFootnote57 called for collaboration between the IASB and the ISSB on the future of the management commentary project, as it could become an important tool for connecting financial with sustainability disclosures.

Another distinction between the standards refers to the materiality focus. IFRS S1 and S2 have a single focus on financial materiality. This approach is also evident in the VRF, which was consolidated with the IFRS Foundation. In contrast, the ESRS apply the double materiality concept. Again differently, the GRI Standards focus solely on an organization’s impact materiality.

At the 27th UN Climate Change Conference (COP27), the ISSB highlighted its aim of maximizing interoperability between IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and the ESRS. The published standards of the ISSB allow the ESRS disclosure requirements to be followed if an identified sustainability-related risk is not covered by the former (see section 4.3.2). The interoperability between the ESRS and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards is also emphasized by the European Commission in its delegated act for the first set of ESRS (European Commission, Citation2023d). Moreover, in August 2023, the EFRAG published a preliminary mapping table on the alignment of disclosures according to the ESRS and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards (EFRAG, Citation2023a).Footnote58

Both EFRAG and the IFRS Foundation also entered into collaborative arrangements with the GRI with the aim of achieving interoperability between the standards (GRI, Citation2022a).Footnote59 Accordingly, the ISSB states that efforts were made so that the IFRS S1 and S2 also connect with the GRI Standards (see section 4.3.2), underscoring the ISSB’s approach to interoperability (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023b). Following the publication of the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards, the GRI also announced the development of technical mapping of the GRI Standards and the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and a digital taxonomy for streamlining disclosure. According to the GRI, the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and the GRI Standards together constitute a ‘comprehensive corporate reporting regime’ encompassing impact reporting and sustainability-related financial reporting (GRI, Citation2023a). In June 2022, the GRI also provided technical mapping of EFRAG’s exposure drafts of the ESRS against the GRI Standards as part of its response to EFRAG’s public consultation on the drafts (GRI, Citation2022b). Moreover, the European Commission’s delegated act for the first set of ESRS also highlights the standards’ interoperability with the GRI Standards (European Commission, Citation2023d). In a joint statement issued by the EFRAG and the GRI in September 2023, the two organizations also highlight that their respective standards closely align with respect to the reporting on impact materiality (EFRAG, Citation2023b). Related to this, the two organizations issued a draft interoperability index of their respective standards in November 2023, which maps common data points and outlines how reporting under the ESRS can be used to report with reference to the GRI Standards (GRI, Citation2023c).

4.4.2. Critical Reflection

The publication of the IFRS Foundation’s consultation paper on sustainability reporting in September 2020 was the starting point for a critical debate among accounting scholars on the optimal path towards sustainability standard setting (Adams, Citation2021; Adams & Mueller, Citation2022; Cho et al., Citation2022; Laine & Michelon, Citation2020; Professors of Accounting, Citation2020). These scholars argue that the IFRS Foundation largely neglected insights from the academic community on sustainability reporting in the initial phase of standard setting. They criticize the IFRS Foundation’s approach for its neglect of stakeholders other than investors, the climate-first approach, and the focus solely on financial materiality. We also advocate a well-founded and inclusive approach to standard setting that comprehensively embraces the diversity of stakeholders’ needs so that companies’ reporting activities account for the multiple challenges of future sustainability developments.

The different approaches to materiality in the three standards discussed and the sustainability topics covered may also offer significant challenges to reporting entities. Although the ISSB intends the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards to be compatible with the GRI Standards to serve stakeholders other than investors, how disclosures according to both standards may in practice connect is currently not fully clear. How reporting may be streamlined therefore remains to be seen, because at the time of writing this article (December 2023), technical mapping between the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and the GRI Standards has not yet been published (GRI, Citation2023a). Consistent with Stolowy and Paugam (Citation2023) and Baboukardos et al. (Citation2023), we therefore remain skeptical whether interoperability between the standards will eventually be achieved.

The different approaches to standard setting taken by the ISSB and by the European Commission and EFRAG (see section 4.4.1) highlight the importance of compatibility between standards in keeping the reporting burden for companies reasonable. Following the above, reporting under double materiality is achieved either by applying the ESRS or by applying the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards in conjunction with the GRI Standards. Avoiding duplicate reporting efforts therefore hinges crucially on how much the standards are streamlined and on the options for cross referencing. However, the standards of the ISSB currently only cover climate-related topics whereas the CSRD requires reporting on a broad spectrum of sustainability topics. In general, given the growing number of sustainability policy measures and their inherently long-term view, a focus on financial materiality and solely on environmental topics might miss both the connection with other sustainability dimensions and the potential for inside-out risks to become financially relevant in the long run.Footnote60

Aside from potential differences in the content of disclosure required, uncertainties in the format of reporting may also pose challenges for companies. An important open topic is the management commentary project of the IASB mentioned above in section 4.4.1. According to the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards, disclosure may be contained in the management commentary. However, the management commentary is currently under revision and may change. The IASB has recently also published a comparison between its management commentary exposure draft and the integrated reporting framework (IFRS Foundation, Citation2023h). It therefore remains an open topic at the time of writing this article (December 2023) exactly how sustainability-related financial disclosures in line with the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards may be integrated into the reporting in the revised management commentary.

5. Implications for Practitioners and Researchers

5.1. Implications for Practitioners

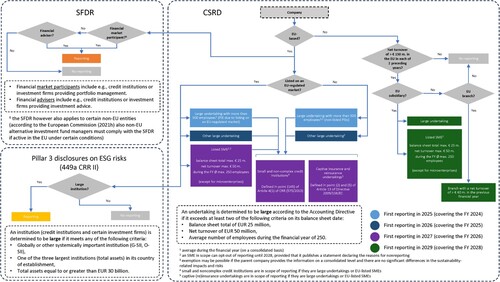

Section 3 outlined the different sustainability reporting mandates in the EU along key characteristics and inter alia also highlighted differences in their scopes. To facilitate a better understanding of which companies are affected by the legislation, provides a generic decision tree.

Figure 1. Decision tree for reporting according to the CSRD, SFDR and Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks.

Nonfinancial companies are mainly targeted by sustainability reporting requirements via the CSRD, which provides for a phased-in application depending on a company’s size, listing status and whether it is located or generating turnover in the EU. In addition to the CSRD reporting requirements, financial companies are also affected by the Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks (large credit institutions and certain investment firms) and the SFDR (financial market participants and financial advisers).

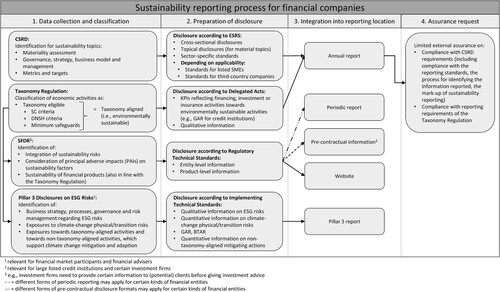

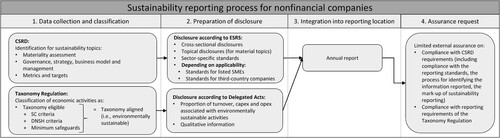

The different requirements in terms of content and reporting formats also lead to different reporting processes. Again, due to the strong focus of the discussed mandates on the financial sector, reporting requirements and processes differ significantly between financial and nonfinancial companies. and illustrate the reporting implications from the mandates separately for financial and nonfinancial companies, respectively.

The CSRD requires reporting according to the ESRS, the disclosure requirements under the Taxonomy Regulation are defined in delegated acts. Similarly, the SFDR and the Pillar 3 disclosures define disclosures in technical standards (both implemented also via delegated acts). In general, all mandates require some disclosure in periodic reporting. Additionally, the SFDR also stipulates disclosures on websites and in pre-contractual formats. Finally, the disclosures according to the CSRD and the Taxonomy Regulation are also subject to external (limited) assurance.

5.2. Implications for Researchers

We develop the future research agenda with recent literature reviews on the consequences of sustainability reporting mandates (Christensen et al., Citation2021; Haji et al., Citation2023), a recent discussion of the developments in sustainability reporting (Baboukardos et al., Citation2023; Stolowy & Paugam, Citation2023), and our own overview of sustainability reporting mandates in the EU.

Every regulatory initiative poses specific challenges and opportunities for researchers. A specific feature of the NFRD was the differences in its national transpositions, which varied across EU member states in the firms that are in its scope, the contents that firms need to disclose, whether external assurance of the content of disclosure is required, and whether firms need to integrate sustainability information into their management reports or may provide the information in a separate sustainability report (see in the appendix). Because empirical evidence on the effectiveness of specific regulatory parameters is currently scarce, the NFRD provides a suitable setting to study the consequences of various regulatory parameters on companies’ sustainability reporting and capital-market and real effects. Insights into the role of these regulatory parameters help tailor sustainability reporting mandates to the needs of specific stakeholders. Similar remarks apply to the national transpositions of the CSRD, albeit the specific national transpositions were not known when writing this article (December 2023).

Furthermore, the CSRD will result in significant increases in sustainability-related data by large unlisted companies and small and medium-sized listed enterprises. Researchers can use this data to better understand the currently under-researched role of smaller and unlisted companies in achieving the transition to a sustainable economy. Furthermore, the digital tagging of sustainability information has the potential to provide researchers with a large dataset independent of third-party data providers. Here, a particular challenge for future research could be to aggregate the immense amounts of data into measures of sustainability (Wagenhofer, Citation2023) that enable high-level cross-sectional and intertemporal comparison. Furthermore, the reporting of sustainability information in companies’ management reports poses questions about whether such integration improves integrated thinking within the company. Researchers can also examine whether digital reporting formats could help mitigate information overload among stakeholders. Furthermore, the role of assurance in sustainability reporting is another topic worth investigating in depth, particularly whether it can encourage companies to improve their sustainability performance.

Researchers could utilize the Taxonomy Regulation’s classification scheme to detect greenwashing (Kim & Lyon, Citation2015; Lyon & Montgomery, Citation2015) and potentially manipulative reporting. At both the company level and the macro levels, the Taxonomy Regulation can help compare and assess the sustainability performance of various companies and therefore society’s overall progress toward a more environmentally sustainable economy. The Taxonomy Regulation itself is worth researching for its consequences on companies’ reporting and capital-market and real effects.

Another area that would benefit from further research is sustainability reporting and the performance of banks and other financial market participants, because these organizations play a major role in achieving the transition toward a sustainable economy. However, research in this area is limited, not least because of the difficulties entailed in measuring and monitoring sustainability in the financial sector. Both the SFDR and the Pillar 3 ESG risk disclosures have the potential to overcome some of these difficulties by increasing standardization in sustainability reporting in this sector. The Pillar 3 disclosures mainly address the sustainability risks that have been dominant in the financial sector over the last decade, and the SFDR also addresses the potential of sustainability to create value for companies, investors, and other stakeholders.