ABSTRACT

This article aims to articulate the richness of the pedagogical relation and pedagogical tact in an age of the near ubiquitous presence of digital education. Drawing on Citton, we argue that there is an ecology of attentional influence that is pedagogically decisive. Our argument proceeds as follows: first, we introduce Citton’s theoretical frame; second, we examine the general conception of education that is established and articulated through the pedagogical relations between educator, student and world; third, we consider the concept of pedagogical tact and analyse how Citton’s framing of attention gives shape to understanding pedagogical tact; last, we connect attention to education, arguing that education concerns drawing attention to aspects of the world through pedagogically tactful action. We conclude by calling for greater reflection on aspects of education which are difficult to render digitally, and which rely on the speculative and interpretive capacities of the educator.

This question is by no means new. It extends and enriches the more basic question of what the differences between digital and face-to-face interactions are (Friesen Citation2011). A generation of philosophers of education and technology have responded to the changing circumstances brought on by digital education, from affirmation of digitalisation in education, to acquiescence, to resistance, to outright rejection. On the one side, there are those such as Dreyfus (Citation2001) who strongly reject the move to digital interactions on the grounds that it is disembodied, and that this lack of embodiment narrows the scope of perception, reduces sensitivity to shared social situations and limits engagement with others. This argument is refuted in equal measure by those such as Downes (Citation2002), who argues that interactions experienced digitally can be just as real, authentic and embodied as the face-to-face experiences that Dreyfus privileges. Unwilling to take sides, some scholars have emphasised the pharmacological nature of digital technology for education (Lewin Citation2016) emphasising the complexity and ambivalence of the debate (Blacker Citation1994; Lewin Citation2021; Selwyn Citation2013). Arguably the most interesting and significant reflections in recent years can be found where the binary between digital and face-face is undercut, what is generally described as a turn to the ‘post-digital:’ interactions should not be understood in terms of a binary of digital/face-to-face but are always a combination of both (Fawns Citation2019).Footnote1

What do these discussions mean for our understanding of the dynamics of pedagogy, such as pedagogical tact? And how might an elaboration of pedagogical tact reframe debates about the digitalisation of education? Norm Friesen has developed a significant phenomenological account of embodied and intersubjective relations which contrast with those digital affordances (Citation2011, Citation2014), arguing that ‘online and offline education are clearly different’ (Citation2011, 7) while acknowledging that the precise nature of that difference is elusive. For Friesen, pedagogy is a human science (Citation2017) which, he argues, needs to be expressed in a language that attends to human experience and to deal with questions of meaning and significance, rather than computational language such as ‘data,’ ‘information’ and ‘transmission’ (Citation2011, xv). For example, if considering the difference(s) between pedagogical tact enacted digitally as opposed to face-to-face, analysis should focus on finding the right language to express how it is experienced rather than the results or outcomes of the actions. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty (Citation2002), Friesen argues that language is the most effective means by which to explore the different experiences of pedagogical dynamics, and that finding an appropriate language to discuss digital and face-to-face education is of pedagogical significance.

Our argument builds on Friesen’s (Citation2011) phenomenological account of face-to-face education by enriching the language used to articulate two key pedagogical notions: the pedagogical relation and pedagogical tact. To do this, we draw on Yves Citton’s (Citation2017) ecological understanding of attention and frame our analysis of the pedagogical relation and pedagogical tact using his language of joint attention. Doing so, we argue, emphasises the importance of pedagogical tact and the pedagogical relation in understanding education in the digital age. Our account admits of a particular view which favours the experience and exposition of face-to-face education, but this analysis should nevertheless afford greater reflection on digital education by ensuring that the analysis of face-to-face education receives sufficient critical attention in discussions of digitising education. Our argument proceeds as follows: first, we introduce Citton’s theoretical frame; second, we examine the general conception of education that is established and articulated through the pedagogical relations between educator, student and world; third, we consider the concept of pedagogical tact and analyse how Citton’s framing of attention gives shape to understanding pedagogical tact; last, we connect attention to education, arguing that education concerns drawing attention to aspects of the world through pedagogically tactful action. We conclude by calling for greater reflection on aspects of education which are difficult to render digitally, and which rely on the speculative and interpretive capacities of the educator.

From economy to ecology of attention

Citton’s analysis begins by recognising that society is in danger of being overwhelmed by an abundance of knowledge and of potential educational subject matter. His general thesis invites a ‘reversal’ of focus away from the materiality of knowledge through forms of knowledge production, towards knowledge reception or consumption. The reversal describes a shift of scarcity – from production to consumption: ‘the new scarcity is no longer to be situated on the side of material goods to be produced, but on the attention necessary to consume them’ (Citton Citation2017, 8).Footnote2 Citton’s centring of attention as the scarce resource of our epoch extends the already substantial body of research analysing the attention economy (e.g. Crary Citation1999; Crawford Citation2015; Davenport and Beck Citation2001). But Citton calls for a shift in our thinking here away from the economistic framing of attention to a more holistic ‘ecology of attention.’ Acknowledging that ‘it can be enlightening to consider attention as the “capital” peculiar to a new level of the market economy,’ Citton goes on to say that ‘you trap yourself in a narrow and distorting perspective when you content yourself with an economic paradigm to account for attention’ (20). This paradigm is problematic because it rests on a ‘deceptive individualist methodology’ (21) that instrumentalises attention: it becomes a tool to optimise the satisfaction of individual desires. The basic point for Citton is that a far more compelling set of metaphors can be developed by a shift to conceiving of attention as an ecological phenomenon.

We believe that the shift to interpreting attention ecologically is especially relevant for educationalists since ecological terminology affords insights into pedagogical concepts that are overlooked or precluded by relying on the prevailing economic vernacular. A phenomenological account of the richness of pedagogical relations (between educator, student and content) opens our awareness of certain material conditions for the formation of attention. Citton’s book sets out to help us ‘[…] learn to make ourselves more attentive to one another, and to the relationships from which our communal lives are woven’ (x). This ecological view of attention opens us up to seeing attention as a collective, joint, and individuating phenomenon in contrast to a more individualistic notion suggested by the dominant economic discourse. Attention is formative through co-presence in ways not altogether easy to articulate but which Citton characterises as follows: ‘[t]he co-construction of subjectivities and intellectual proficiency requires the co-presence of attentive bodies sharing the same space over the course of infinitesimal but decisive cognitive and emotional harmonisations’ (18). This compelling expression suggests something about our educational relations that are central to this paper. The expression arises in a context: a discussion of joint attention and its operation within an educational situation, such as teaching in a classroom.

We take up Citton’s use of the concept of joint attention which he defines as: ‘being attentive to what the other pays attention to’ (94). It designates a set of localised situations in which my awareness of the attention of others affects the orientation of my own attention. ‘I turn my gaze in this direction as a consequence of the fact that someone else in my environment has previously turned theirs in the same direction’ (84). Joint attention is characterised by situations of presential co-attention in which ‘several people, conscious of the presence of others, interact in real-time depending on their perception of the attention of other participant’ (84).

Citton acknowledges that this presential co-attention does not necessarily require physical co-presence i.e. being in a shared physical space, but could also take place through a digital medium such as Skype. The key factor is the ability to be sensitive to the emotional variations of the other participants. Therefore, so long as one’s video does not freeze and microphones are working, it seems reasonable to extend the possibility of presential co-attention to digitally mediated forms of communication, or at least not to exclude it a priori.

Indeed, many have argued that embodiment is not done away with in the virtual world (Bayne Citation2015); on the contrary, digital interactions are their own kind of embodied co-presence (Bayne et al. Citation2020). It could be argued that being present together can take place within a virtual classroom, and that we do not, in such experiences and activities, disavow our physical bodies (Knox Citation2019). We acknowledge in line with Citton, that the valorisation of physical co-presence need not imply a dichotomy which entirely rejects or abhors the digital. But in what follows we argue that much of the richness of face-to-face education, characterised through the pedagogical relation and pedagogical tact, does not lend itself easily to being digitally rendered.

The central argument of our paper takes up Citton’s notion of joint attention to enrich an understanding of the dynamics of pedagogical situations. We do this by focusing the analysis on two key pedagogical concepts: first, through an exploration of the pedagogical relation; second, through pedagogical tact. We have chosen these two pedagogical elements since they are foundational and mutually related pedagogical concepts: that a precondition for the effective exercise of pedagogical tact is an established pedagogical relation. These concepts also most readily lend themselves to the analysis of educational events using joint attention.

The pedagogical relation

The ‘pedagogical relation’ is a term that can mean different things in different contexts: it can refer specifically to a personal relationship between an educator and a student (Friesen Citation2017) or it can refer more generally to the relations between elements of the pedagogical triangle: that is between the educator, student, and subject matter (Friesen and Kenklies Citation2022). According to one continental pedagogy tradition derived in part from Schleiermacher (Schleiermacher Citation2022), it refers to the intergenerational relation between the mature adult and the immature child (Friesen and Kenklies Citation2023, 6). While this intergenerational framing of the relation is significant, we take this structure to apply more generally to any educator-student relation.

The German pedagogue Hermann Nohl develops a rich analysis of the pedagogical relation that focuses on the personal relationship between an educator and a student (Nohl Citation2022). Nohl identifies several features of this relation that make it pedagogical, the most significant being that the influence of the educator is ‘specifically for the sake of the latter [the student], so that he comes to his life form’ (Citation2022, 79). There is much to unpack in this short phrase. Acting ‘specifically for the sake of the latter’ could mean acting for the child as they are, or the becoming of the child as imagined by the educator (80). The idea of the child coming to their ‘life form’ is also ambiguous, though perhaps understandable within the context of Bildung which, though also notoriously difficult to define or translate, can refer to a ‘kind of formative “becoming human” that spans the biographical, collective, institutional, and historical dimensions of life’ (Friesen and Kenklies Citation2023, 10). The ambiguities of Nohl’s definition of what makes influence pedagogical can be mitigated if we focus on his elaboration of more precise features of the pedagogical relation (Citation2022, 75–76).

First, the pedagogical relation is asymmetrical: there is a responsibility for the educator to act for the good of the student that is not reciprocal. Second, there is a particular temporality: that it is oriented to the future becoming of the student, not only their present. Third, the relation is impermanent: that the relation seeks to make itself redundant by fulfilling its aim. Fourth, the relation has a proximity to tact which is discussed in detail later. The last feature, which we elaborate in more detail here, is that the pedagogical relation is founded on love. While some definitions of love highlight intense feelings and deep affections between teachers, students, and the subject matter, we emphasise one dimension central to pedagogy: that love is an action specifically for the sake of another (in this case, the student).

The general idea is common enough: parents and educators routinely act for the sake of their children or students. And there is a general logic to supposing that such actions would come at some cost. Acting for the sake of the student could mean the sacrifice – or at least temporary suspension – of the educators’ own satisfaction. Consider, for example, the teacher giving up their break time to talk to an upset student, or the parent making time to spend drawing with their child. But not all teachers, or even parents, act on the purest of motivations, so can we assume that the pedagogical relation is characterised by this kind of love? While Nohl defines the pedagogical relation as actions specifically for the sake of the student, we must acknowledge that, in practice, determining whether an action is for the sake of another is complex since the sacrifice of the parent (or educator) oftentimes seems to bring about a different, indirect, kind of satisfaction: any apparently selfless act may contain a seed of self-interest. On this basis we could wonder whether a purely pedagogical relation can ever be realised. Rather than choose between acknowledging the complex dynamics of love between self and other, or sticking with Nohl’s definition, we suggest a practical refinement of Nohl’s theory: that acting for the sake of another need not entirely rule out self-interest. This argument is not meant to disparage parents or educators by suggesting their intentions are muddied with self-interest but is intended to show that the educator’s love of student and of themselves can be conjoined and harmonised. This is where Citton’s shift to the ecological framing of attention can be enlightening since he shows how an individualised and scarce framing (of attention) is insufficient to describe the inter-subjective dynamics of love in pedagogy. There is, we argue, a connection between the love for the student (expressed as action for their sake) and self-love (action for one’s own sake) which can be analysed through Citton’s idea of the ecology of attention. To elaborate the dynamics of love in the pedagogical relation, we will say more about not only two, but three forms of love that, we suggest, are operative therein.

These three forms of pedagogical love are: the educator’s love for the student; the educator’s love for themselves; the educator’s love for the world (or subject matter). We have already noted that pedagogical love for the sake of the student does not need to be in opposition to the educator’s self-love. For example, as professionals, teachers also work for themselves no matter how much they work (or claim to work) for the sake of the student.

In addition, there is a love for the world (or for some aspect of it) that animates a certain idea of thing(s)-centred, or world-centred, education (Biesta Citation2022; Vlieghe and Zamojski Citation2019). Here the educator’s love for the thing animates pedagogical relations because it provides the interest and energy for the thing to be shared with others.

There can be an ecology of love here in which these three loves find mutual expression and that requires sensitivity to emotional variance which, we believe, relies on ‘the co-presence of attentive bodies’ (18). In a pedagogical situation (whether classroom, home, or elsewhere), the educator initiates a shift of attention to some thing e.g. an idea, object or experience. This being-oriented is by no means only a matter of words but is hinted at by the apparent passion of the educator and the gestures thereby expressed. This passion indicates, or testifies to, a love for the thing as worthy of attention. The student may observe some kind of love for the thing in the attention shown by the educator and may, therefore, be enticed to attend to it themselves.

We offer a scenario drawn from the experience of one of the authors not because that experience is special or interesting, rather the opposite. We suspect that this type of experience is commonplace in schools, colleges and universities because teaching is fundamentally relational and attentional. So, this example is not exemplary in any normative sense, but illustrates the relational structure of everyday teaching practices as well providing an instance of pedagogical tact:

With a wry smile and a twinkle in his eye, our seminar tutor passes round a photocopied text (informing us simply that there is one each) with the title ‘The Lord (Eesha Upanishad).’ I wonder if we are meant to read the text now. Without instruction the tutor puts on his glasses and gazes intently at his own text as the chatter quickly dissipates. I see him become absorbed and a quick glance around the room tells me that my fellow students have begun to read. I follow suit:

That is perfect. This is perfect. Perfect comes from perfect. Take perfect from perfect, the remainder is perfect.

What on earth does it mean? I glance up again to see the tutor also glance up at us, his eye momentarily catching mine. Again, he has that wry smile. Then he goes back to reading and I notice the intensity with which he reads. What is it about this text? My attention is drawn again to the page on the desk and so I read on with a renewed interest.

The educator’s love for something is magnetic in drawing others to it. Citton’s concept of ‘joint attention’ is suggested here in that ‘my consciousness of the attention of others affects the orientation of my own attention’ (83). But more significant are what Citton calls the ‘infinitesimal but decisive cognitive and emotional harmonisations’ (18) that draw us together before the text. The love for the thing appears to be connected to the love for the students. The tutor’s gestures – his smile and glances – suggest he is relishing the opportunity to share and later discuss this text, thus indicating a self-interest that is not incidental, but which harmonises with his love for the students. It is as if the students attend to the text more because the tutor loves it and loves himself enough to indulge his own passion. This love for the subject is not at the expense of the students, but, in fact, out of love for them.

There is a looping, tria-lectical movement between these three loves. Some might say that this is initiated by the love of the thing or the world (Biesta Citation2022; Vlieghe and Zamojski Citation2019). But the love must be shared for the sake of the student – a sharing which also pleases the tutor – for that love to be pedagogical love or for a pedagogical relation to be realised.

Furthermore, the activities of the educator in this case, from the infinitesimal gestures that seek cognitive and emotional harmonisation, to the choice of text, are all informed by a sensitivity to the place, time and relations of teaching, a sensitivity which is nothing other than the epitome of pedagogical tact (Van Manen Citation2016) (further developed in the following section).

And what of physical co-presence? Citton says that ‘[…]we all hunger for irreplaceable affective resonances that only an ecosystem of reciprocal attention experienced in the immediacy of co-presence can bring’ (99). While this claim may seem somewhat overstated, we affirm the pedagogical significance of those affective resonances afforded by the immediacy of physical co-presence. The mutual recognition and reinforcement of love between educator and student here relies on affective resonance and the exercise of pedagogical tact that physical co-presence enables. The student discerns the educator’s love primarily through infinitesimal emotional harmonisations expressed by myriad gestures, many of which are not straightforwardly quantifiable and therefore do not seem to lend themselves to virtual rendering.

Pedagogical tact

To extend our analysis, this section first introduces the concept of ‘pedagogical tact,’ and then considers it through Citton’s frame of joint attention by referring to an example. Pedagogical tact affords deeper insight into the pedagogical relation, specifically, how the educator relates to a student’s relation to content, i.e. the act of educating (Friesen and Kenklies Citation2022). The need for pedagogical tact follows from understanding pedagogy as a scienceFootnote3 following Herbart and Schleiermacher. Pedagogy as a science (Wissenschaft) is the means to orient oneself, to support and guide judgements based on a combination of principles which collectively form a comprehensive system for making sense of educational practice. Pedagogy provides the educator with a framework to perceive the world through an educational lens, which can then guide practice. But pedagogy is not a handbook for what to do in every pedagogical situation or relation since education as a practice necessitates consideration of the uniqueness of the single case. Pedagogy does not prescribe to the educator how to relate to the student in each specific instance. Herein is the role for pedagogical tact, to bridge the gap between theory and practice in any pedagogical relation.

As with the pedagogical relation, pedagogical tact has been defined in different ways. We take up Herbart’s (Citation1896) definition as ‘a Classic theorem of pedagogical thinking, especially within Continental Pedagogy,’ which was intended to solve the systematic problem of connecting universal theory to particular practice (Kenklies Citation2023, 114). Herbart introduces pedagogical tact in his 1802 Introductory lecture to students in pedagogy:

There is, to wit, a certain tact, a quick judgment and decision, not proceeding like routine, eternally uniform, but, on the other hand, unable to boast, as an absolutely thorough-going theory should, that virile retaining strict consistency with the rule, it at the same time answers the true requirements of the individual case… [Pedagogical tact] inevitably originates in man as he is, out of continued practice, a mode of action which depends on his feeling… and exhibiting his emotional state, than the resultant of his thinking. (20)

In other words, tact is that judgment and action that arise from continued educational practice. In a sense, pedagogically tactful action thus eludes advanced planning. It is situated in an aporia: since every student is unique, there is no pedagogical prescription for dealing with the totality of actions. As Muth (Citation2022) notes, ‘tactful action cannot be realised in a pre-planned educational operation, but always in the unforeseeable situation in which the educator is engaged’ (89). An educator could have the most detailed plans for their practice but would nevertheless not be able to take account of every possible student response.

However, this uncertain nature of educational practice should not be confused with a form of ‘pedagogical naturalism,’ i.e. abandoning pedagogical training and relying on what comes ‘naturally.’ On the contrary, the elusiveness of tact should in fact open a horizon for even greater pedagogical consideration. Muth (Citation2022) continues: ‘because it is manifest in unplannable instructional phenomena, a decisively more intensive planning of instruction is needed in comparison to […] slavishly anticipating, in a strictly determined sense, all of the events possible in the classroom’ (89–90). Advanced planning and understanding pedagogy as a science should not be disregarded, but the educator should also balance this with retaining the flexibility to deviate from a preconceived course of action. In each individual case, the educator must ‘use his head as well as his heart for correctly receiving, apperceiving, feeling, and judging the phenomena awaiting him and the situation in which he may be placed’ (Herbart Citation1896, 21). This means that pedagogical tact is always situated in the position of the individual case, as an educational response to the riddle(s) presented by each unique student.

We think that Citton’s concept of joint attention enriches an understanding of pedagogical tact. This is helpful since, as Van Manen (Citation2016) notes, ‘pedagogical tact is an elusive and slippery notion’ (78). Tact cannot be reduced to a blueprint or set of rules since it is always specific to each unique pedagogical occasion and governed by the moral intuitiveness of the educator. However, it can be stimulated and strengthened if educators better understand it. We argue that understanding tact framed through Citton’s joint attention can help do this.

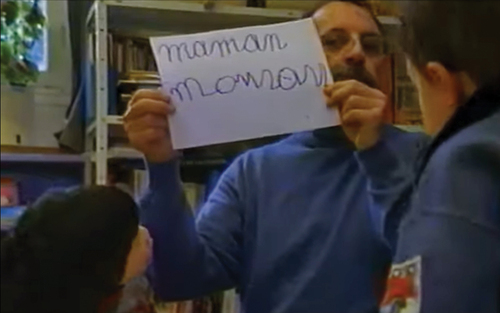

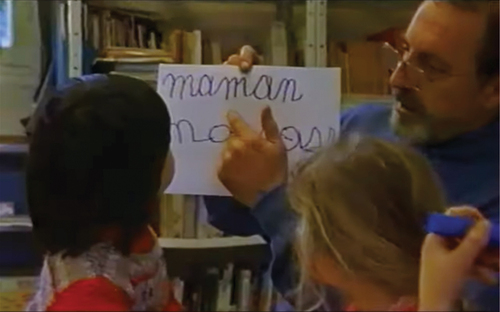

To illustrate how Citton’s frame enriches an understanding of pedagogical tact, consider the following example from Nicholas Philibert’s 2002 documentary, Être et Avoir.Footnote4 The chosen clip shows teacher Georges Lopez with his kindergarten class reviewing the students’ handwriting practice.

Partial transcript

Georges Lopez (GL): ‘I want you all to show your work. Let’s look at Jojo’s. What do you think?’Marie: ‘Good.’GL: ‘Good. You could go on … ’Marie: ‘It’s a little bit good.’GL: ‘A little bit good. What do you think, Jojo? Look. What’s it like?’Jojo: ‘Good!’GL: ‘You say “good.” Marie says, “a little bit good.” What about you, Létitia?’Létitia: ‘Good.’GL: ‘And you, Johann?’Johann: ‘Yes.’GL: ‘There may be something missing here. The stick going down isn’t there. There!’

To analyse the example, we consider pedagogical tact, framed by Citton’s notion of joint attention.

First, pedagogically tactful action entails a principle of reciprocity: for joint attention, ‘attention must be able to circulate bidirectionally between the parties involved’ (85). Environments and the actions of the educator must be conducive to joint attention to afford pedagogically tactful practice. ‘Size appropriateness’ is certainly a consideration here: reciprocal attention occurs on a one-to-one scale, with two-way attention between educator and student. In the example, the classroom size seems ‘appropriate’ to afford pedagogical tact: Lopez can clearly see each of the children to allow for the affective resonances Citton deems decisive, and they can see him.

Moreover, a principle of reciprocity does not mean that there should be a perfectly equal relation between both parties, nor an equitable amount of speaking time. As was noted earlier, the pedagogical relation is asymmetrical. What is important is that a conversation can occur, either between educator and student(s), or amongst students. Stoy (in Muth Citation2022, 96) stresses the importance of how educators communicate in relation to tact:

The tactful person is one who has the right word for every occasion, the right content for his speech, the right tone, the correct emphasis, the right sequence in speech and action. And the educator who handles individual’s natures correctly, valuing the meek and humble, not pressuring the slow, never harsh to the sensitive […] they receive from every unbiased observer the recognition of tactfulness.

In the example, Lopez appears to do just this by addressing each individual student in a gentle tone, not rushing them to respond but inviting their contributions in a sequence that builds on and values the responses that have preceded. As a result, the students seem engaged, attentive to the task, and enter conversation with Lopez by answering his questions.

Second, Citton argues that joint attention is characterised by a striving for affective harmonization: ‘you cannot be truly attentive toward the other without being considerate toward them’ (86). Being ‘considerate’ means making ‘micro-gestures of encouragement, sympathy, prevention, precaution or reassurance’ (86). In other words, forming an emotional connection is important for pedagogically tactful practice when understood through joint attention.

In the example, Lopez establishes an emotional connection with the children in his class in several ways. First, by moving from standing to sitting around the table (), Lopez demonstrates that he is sympathetic toward his students and that he is willing to strive for affective harmonisation. To name just one effect of this gesture, it makes it easier for the students to have eye contact with Lopez, since they are now closer to the same level. Then, Lopez holds up the sheet of paper for Jojo to see (). This micro-gesture of encouragement shows Jojo that Lopez values his work and reassures Jojo that Lopez cares about him. Turning next to Létitia and Johann (), Lopez makes eye contact with them each in turn and invites them to respond in a reassuring tone. Last, observing that none of the class has spotted the missing ‘stick,’ after having gone to great lengths to elicit a response, Lopez points to the error (). In doing this, Lopez prevents a misunderstanding: were he not to draw attention to the error, the students would likely not perceive it as such. Whilst these might seem like infinitesimal actions taken by Lopez, they also appear decisive in establishing an emotional connection and fostering the joint attention needed for pedagogically tactful action.

Figure 1. Moving from standing to sit between the students: ‘I want you all to show your work. Let’s look at JoJo’s’.

Figure 3. ‘You say ‘good.’ Marie says, ‘a little bit good’.’ Turning his attention to Létitia and Johann in turn: ‘What about you, Létitia? And you, Johann?’.

Figure 4. Pointing to the error: ‘There may be something missing here. The stick going down isn’t there. There!’.

Third, pedagogically tactful teaching involves improvisation practices that ‘require learning to get out of the pre-programmed routines, so you can open yourself to the risks (and techniques) of improvisation’ (88). In any dialogue, there is exposure to risk: by starting a sentence, one opens the possibility of failure, to the risks of micro-improvisations which are relied on to bring the sentence to an end. But the risk goes further than just the words spoken: in a shared physical space such as the classroom Lopez is teaching in, practices such as pointing, movement around the classroom, Lopez’s appearance, etc. – all of these are at stake. Furthermore, at the end of the lesson, the students will still be in the same space. In contrast, imagine Lopez were instead teaching in a virtual classroom: at the end of the lesson, he could simply turn off his screen.

Considering the example, Lopez first asks his class questions to see if they notice the handwriting error (the missing ‘stick’). By structuring the activity in this way (trying to draw out the error from the students by asking questions), Lopez allows for the risk that they do not spot the error. If they noticed it themselves, his teaching would have taken a different course. But, on realising that none of the class has spotted the error that he intends to highlight, Lopez changes his approach and identifies the error himself (). To do this, he holds up the piece of paper and, instead of asking more questions, points to the error with his finger, concurrently redirecting his attention to the paper in his hands. Lopez is improvising here, tactfully gauging the students’ responses to his questions and using these as the basis for his next action (either more/different questions or pointing to the error himself). There is a risk that this approach fails, and the students do not understand the teaching point of the handwriting error. Indeed, exercising tact is in fact always speculative in that the educator can never be certain of the outcomes – there is a risk that the actions of the educator will be judged differently to how they were intended. That risk would also be present in a virtual classroom, but there seems more at stake here. When asking the students questions, Lopez adjusts the direction of his gaze, the tilt of his head, the amount he leans into the circle of students. In every one of these actions, there is a risk that they might be perceived differently to how Lopez intends. As before, these seemingly infinitesimal actions appear pedagogically decisive.

To sum up the section, we have argued that an understanding of pedagogical tact can be enriched and elucidated through a framing of joint attention. We drew on the documentary Être et Avoir to show this through an analysis of teacher Georges Lopez’s actions. Moreover, we hope to have shone light on the pedagogical dynamics within this face-to-face education through the above analysis. With Citton we recognise that there is something infinitesimal yet decisive about the presential enthralment which ‘weave[s] our affectivity through the inter-fertilisation of crossed attention communicating in a relation of immediate bodily presence’ (104). The richness of these pedagogical dynamics should not be overlooked in rendering educational forms digital.

Attention, pedagogical tact and education

Our interpretations of the above examples are made to illustrate how education is a relational phenomenon in which educator, student and world are brought together into a mutual resonance where educators, students and the world are gathered in moments of joint attention. Korsgaard (Citation2024) makes a similar point, noting that education is about ‘foster[ing] moments of attention to something common without a specific aim or outcome in mind. Only thus can we establish a pedagogical relation between the new generation and the world’ (66). Moreover, this attention should be fostered in such a way, using pedagogical tact, so that the student comes to understand the thing/content in a particular form and history, as part of something made common. Put differently, education concerns drawing attention to aspects of the world through pedagogically tactful action.

Despite the differences in the chosen examples (the first is based on one of the author’s own university experiences; the other is taken from a documentary film set at a French primary school), in both cases the attention of the educators and the students are mutually engaged with something in the world. And in both cases the encounter between the student and thing/world was facilitated by the exercise of pedagogical tact of the educators within the context of face-face pedagogical relations. However, these examples were not meant to suggest that the educator’s exercise of tact in gathering attention operates in only one direction – from educator to student. Rather the influence is better understood as a resonance in which the tact of the educator is also responsive to the ways in which the students’ attention is drawn: the nature of tact is, of course, its sensitivity to context. In our account attention is exercised simultaneously by both educators and students even though we talk primarily of the tact of teaching and the attention of the student. The point here has been to explore the ecological nature of joint attention in line with Citton and Norman (Citation2017) and to show how this helps to understand the richness of pedagogical dynamics exhibited in instances of education.

Conclusion

We have argued that Citton’s Ecology of Attention, in particular the notion of joint attention, enriches and elucidates an understanding of the dynamics of pedagogy. The ‘infinitesimal but decisive cognitive and emotional harmonisations’ articulated by Citton provided a ‘way in’ to our analysis. We then explored this further through a focus on two foundational pedagogical concepts: the pedagogical relation and pedagogical tact to make a case for the richness of physical co-presence in education.

But perhaps we cling to this idea of physical co-presence out of a romantic attachment that valorises our own proclivities and experiences. Maybe we have succumbed to confirmation bias in our reading of Citton, encountering an argument that was well-aligned with our own prejudices.

In consideration of this possibility, our argument is not set out as an attack on digital forms of education, but rather as a call for greater reflection on aspects of education which are difficult to measure, quantify, and render digitally, and which rely on the speculative and interpretive capacities of the educator. In other words, we wonder about those aspects of education that fall through the cracks of many conceptions of digitised forms of education; we worry that in our haste to make digital education ubiquitous, those aspects will be lost. While it is insufficient to rely only on anecdotal or personal experiences, there is, we believe, sufficient reason to question the hasty reduction of education to transmission of information through digital platforms. The issue is, then, partly to do with how education itself is too often misconstrued as transmission which allows us to forget the other dimensions of education that are not so easily digitised.

We think this theoretical exploration is pertinent at a time of ever-increasing, and often unquestioned, digitisation of educational forms. We conclude by dwelling on the richness of pedagogical relations that concerns drawing attention to aspects of the world through pedagogically tactful action. We therefore call for greater attention to drawn to aspects of education which are difficult to render digitally, and which rely on the speculative and interpretive capacities of the educator.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. In the context of the post-digital, we must acknowledge that finding the most appropriate terminology is not straightforward. There are various candidates to describe face-to-face encounters, e.g. embodiment, physical co-presence, inter-corporeal relations. But being online does not mean we are not in some sense face-to-face, co-present or embodied. Hence the post-digital observation that this binary is in risk of collapse. So, a post-digital reflection on our general argument may demand further reflection on the distinctions we are relying on than space allows. For practical purposes, we refer here to face-to-face vs digital or physical co-presence vs virtual.

2. References to this text are numerous and are therefore abbreviated to page numbers listed parenthetically hereafter.

3. ‘Science’ is used here as a translation of the German Wissenschaft, which Friesen and Kenklies (Citation2023, 23) note does not have the same connotation of ‘natural sciences,’ which the term has in English, but instead designates any rigorous academic pursuit.

4. We are not the first to draw on this documentary to illustrate pedagogical tact. Accordingly, thanks to Friesen (Citation2018) for the inspiration to watch the documentary and Morten Korsgaard and Johan Dahlbeck for guiding discussion during their Foundational Educational Theories course to arrive at a deeper understanding. Etre et Avoir, film, directed by Nicolas Philibert (Paris: Les Films du Losange, 2003).

References

- Bayne, S. 2015. “What’s the Matter with ‘Technology-Enhanced learning’?” Learning, Media and Technology 40 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.915851.

- Bayne, S., P. Evans, R. Ewins, J. Knox, J. Lamb, H. Macleod, C. O’Shea, J. Ross, P. Sheail, and C. Sinclair. 2020. The Manifesto for Teaching Online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Biesta, G. 2022. World-Centred Education: A View for the Present. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Blacker, D. 1994. “Philosophy of Technology and Education: An Invitation to Inquiry.” Philosophy of Education Society Yearbook. http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/EPS/PES-Yearbook/94_docs/BLACKER.HTM.

- Citton, Y. 2017. The Ecology of Attention. Translated by B. Norman, Cambridge, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- Crary, J. 1999. Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle and Modern Culture. London, England: MIT Press.

- Crawford, M. 2015. The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction. London, England: Penguin.

- Davenport, T. and J. Beck. 2001. The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Downes, S. 2002. Education and Embodiment. Stephen Downes ‘Knowledge, Learning, Community’ (blog). April 26, 2002. https://www.downes.ca/post/92.

- Dreyfus, H. L. 2001. On the Internet. London, England: Routledge.

- Fawns, T. 2019. “Postdigital Education in Design and Practice.” Postdigital Science & Education 1:132–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0021-8.

- Friesen, N. 2011. The Place of the Classroom and the Space of the Screen: Relational Pedagogy and Internet Technology. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Friesen, N. 2014. “Telepresence and Tele-Absence. A Phenomenology of the (In)visible Alien Online.” Phenomenology & Practice 8 (1): 17–31. https://doi.org/10.29173/pandpr22143.

- Friesen, N. 2017. “The Pedagogical Relation Past and Present: Experience, Subjectivity and Failure.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (6): 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1320427.

- Friesen, N.,and K. Kenklies. 2022. “Continental Pedagogy & Curriculum.” In edited by R. Tierney, F. Rizvi, and K. Ercikan. 4th ed. International Encyclopedia of Education, 245–255. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Friesen, N., and K. Kenklies. 2023. F.D.E. Schleiermacher’s Outlines of the Art of Education. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Herbart, J. 1896. Herbart’s ABC of Sense-Perception, and Minor Pedagogical Works. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.

- Kenklies, K. 2023. “Pedagogies in Dissonance: The Transformation of Pedagogical Tact.” Global Education Review 10 (1–2): 114–127.

- Knox, J. 2019. “What Does the ‘Postdigital’ Mean for Education? Three Critical Perspectives on the Digital, with Implications for Educational Research and Practice.” Postdigital Science & Education 1 (2): 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00045-y.

- Korsgaard, M. T. 2024. Retuning Education: Bildung and Exemplarity Beyond the Logic of Progress. Abingdon, England: Taylor & Francis.

- Lewin, D. 2016. “The Pharmakon of Educational Technology: The Disruptive Power of Attention in Education.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 35 (3): 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-016-9518-3.

- Lewin, D. 2021. “The Pedagogical Relation in a Technological Age.” In Interpreting Technology: Ricoeur on Questions Concerning Ethics and Philosophy of Technology, edited by W. Reijers, A. Romele, and M. Coeckelbergh. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. C. Smith). 2002. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by. London, England: Routledge.

- Muth, J. 2022. “Pedagogical Tact: Study of a Form of Educational and Instructional Engagement (selections).” In Tact and the Pedagogical Relation: An Introduction, edited by N. Friesen. New York: Peter Lang.

- Nohl, H. 2022. “The Pedagogical Relation and the Formative Community.” In Tact and the Pedagogical Relation: Introductory Readings, edited by N. Friesen, 75–84. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Schleiermacher, F. 2022. F.D.E. Schleiermacher’s Outlines of the Art of Education: A Translation & Discussion. Translated by N. Friesen and K. Kenklies. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Selwyn, N. 2013. Distrusting Educational Technology: Critical Questions for Changing Times. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Van Manen, M. 2016. Pedagogical Tact: Knowing What to Do When You don’t Know What to Do. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Vlieghe, J., and P. Zamojski. 2019. Towards an Ontology of Teaching: Thing-Centred Pedagogy, Affirmation and Love for the World. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.