ABSTRACT

This article explores the ways in which precolonial understandings of the Pacific as a cross-cultural space involving extensive interpelagic networks of trade and cultural exchange, notably elaborated in Tongan scholar Epeli Hauʻofa’s 1990s series of essays celebrating Oceania as a “sea of islands”, are evident in pan-Pacific indigenous protests against nuclear testing in the region. It explores indigenous literary and artistic condemnations of both French and US nuclear testing (which collectively spanned a 50-year period, 1946–96), touching on the work of a range of authors from Aotearoa New Zealand, Kanaky/New Caledonia and Tahiti/French Polynesia, before discussing a recent UK government-funded research project focused on the legacy of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands. The project involved Marshallese poet and environmental activist Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, and a range of her anti-nuclear poetry commissioned for the project (including “History Project”, “Monster” and “Anointed”) is analysed in the closing sections of this article.

On Kili island

The tides were underestimated

patients sleeping in a clinic with

a nuclear history threaded

into their bloodlines woke

to a wild water world

a rushing rapid of salt

(Jetñil-Kijiner Citation2017, 78)

In her poem “Two Degrees” (quoted above), Marshallese performance poet and eco-activist Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner reflects upon the successive waves of environmental and corporeal damage visited upon the people of Bikini Atoll, where the US undertook 23 nuclear bomb tests between 1946 and 1958. Persuaded by the US governor of the Marshall Islands to leave their homeland “for the good of mankind”, and initially believing their displacement would be temporary, Bikini islanders are living in near-permanent exile, with the half-life of the plutonium that has contaminated their homeland estimated at 24,000 years (Johnston Citation2015). The Bikini people have experienced multiple phases of displacement, relocating first to Rongerik (an atoll 200 kilometres east of Bikini) in 1946, then in 1948 – after insufficient food resources brought them to the brink of starvation – to Kwajalein Atoll (site of a US military base, and subsequently a ballistic missile testing range), and on to Kili Island in the southern Marshall Islands. Kili was chosen by Bikini islanders – who initially believed the island would be a temporary home – because it was uninhabited and not within the jurisdiction of any chief (iroij) from any other Marshallese community. Kili was uninhabited for good reasons: it has no lagoon; the surrounding sea is so rough that fishing is unfeasible for several months each year; and at only one-sixth of the size of Bikini Atoll, it does not afford sufficient food or dwelling space for the Bikini community. Some Bikinians have moved to other locations – including Majuro and Jaluit atolls, and Ebeye in Kwajalein Atoll – but those who remained have suffered further hardships as rising sea levels and intensifying storm conditions, resulting from global warming, triggered recurring flooding of the entire island during spring high tides (known as “king tides”) from 2011 onwards (Niedenthal Citation2013). The floods contaminate all the freshwater lenses on the island, destroy crops, spread disease, and have prompted the community to investigate options for relocating somewhere outside the Marshall Islands, which, if global temperatures rise by just two degrees, will disappear below the waves. Through her eco-political activism (including the establishment of Jo-Jikum, her environmental non-governmental organization for Marshallese youth), as well as performance poems such as “Two Degrees”, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner has sought to “turn the tides” against climate change, and to advocate for nuclear justice for the Marshall Islands, which is still waiting for the US to atone for the environmental and socio-economic damage resulting from its military exploitation of the islands across generations (https://jojikum.org/). I will return to Jetñil-Kijiner’s work later in this article, after outlining the broader context of nuclear testing across the Pacific region, and the various indigenous protest movements and literatures that have emerged in response to nuclear imperialism, as these have set a precedent for Jetñil-Kijiner’s more recent interventions.

Figure 1. Panel from “History Project: A Marshallese Nuclear Story”. Adapted from the poem “History Project”, by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner. Illustrator: Munro Te Whata.

As Tongan scholar Epeli Hauʻofa (Citation2008) has pointed out, colonial conceptualizations of the Pacific as a constellation of tiny, putatively isolated and sparsely populated “islands in a far sea” have played a key role in creating a context in which Britain, France and the US justified their decisions to test nuclear weapons in the region during the half-century following the Second World War (31, 37, 46). Long-established western understandings of the Pacific as a realm remote from metropolitan centres of power and comparatively “empty” of people created a context in which, as Hauʻofa notes, “certain kinds of experiment and exploitation can be undertaken by powerful nations with minimum political repercussions to themselves” (46). Britain, France and the US all minimized the risk of international scrutiny by undertaking their nuclear tests in sites over which they had colonial jurisdiction: Christmas and Malden in the Northern Line Islands for Britain; Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia; and Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands for the US. Britain also gained permission to test at Maralinga, Emu Field, and Mote Bello Island in Australia, its former settler colony. Not only have these tests caused significant environmental damage and health problems for Pacific peoples; they have also created what have been termed “nuclear dependencies” in French Polynesia and the Marshall Islands in particular. Significantly, while the majority of Pacific Islands states are now independent, a substantial number of the heavily militarized Pacific Islands remain under US and French colonial or semi-colonial jurisdiction (see Davis Citation2015). It is these contexts of protracted military imperialism upon which I focus in this article.

The Pacific decolonization era, which began with the independence of (Western) Samoa in 1962, gave rise to various political and literary movements designed to counter the isolationalist colonial strategies that had expedited nuclear testing in the region. One of the earliest movements designed to rekindle trans-Pacific alliances was the “Pacific Way” ideology, which emphasized cultural commonalities between Oceanic peoples but foundered after the right-wing military coups in Fiji in the 1980s and 1990s exposed the interracial tensions that have hampered attempts to foster a regional identity (Hauʻofa Citation2008, 43). In an effort to transcend these divisions, in the 1990s Hauʻofa produced a series of influential essays advocating a new regional “Oceanic” politico-ideological identity that would not only help unite and protect Pacific Islanders against the vicissitudes of global capitalism and climate change (a significant consideration given that Pacific Islanders are among the earliest casualties of rising sea levels, as well as suffering the long-term effects of nuclear imperialism), but could also serve as a source of inspiration to contemporary Pacific artists and creative writers (see Hauʻofa Citation2008). Hauʻofa’s model acknowledges the complex and interweaving local, regional and global networks that shape the lives of contemporary Pacific peoples:

The development of new art forms that are truly Oceanic, transcendant [sic] of our national and cultural diversity [ ... ] allows our creative minds to draw on far larger pools of cultural traits than those of our individual national lagoons. It makes us less insular without being buried in the amorphousness of the globalised cultural melting pot [ ... ]. We learn from the great and wonderful products of human imagination and ingenuity the world over, but the cultural achievements of our own histories will be our most important models, points of reference, and sources of inspiration. (Hauʻofa Citation2000, n.p.)

Such a formulation, awash with imagery signalling Hauʻofa’s belief in the ocean as the basis of indigenous Pacific epistemologies and lifeways, offers a compelling paradigm through which to locate “unity in diversity”, resonating with the work of other critical regionalists (such as Gayatri Spivak and Arif Dirlik) who have argued for the importance of recognizing plurality and difference within “new regional” constructs such as “Asia” or the “Asia-Pacific” (Spivak Citation2008; Dirlik Citation1997; see also Wilson Citation2000; Appadurai Citation2001; and Keown and Murray Citation2013).

Western nuclear testing in the Pacific, and in particular the French programme, which stretched across three decades (1966–96), has generated protest movements and literatures that – in keeping with Hauʻofa’s model – transcend imposed colonial divisions in the Pacific by fostering regional solidarity. Notably, some of these movements have involved not just indigenous communities, but also members of the white settler cultures in Australia and New Zealand. Notable examples of regional anti-nuclear activity include the establishment of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone (with the signing of the Treaty of Rarotonga in 1985);Footnote1 the founding of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement (a coalition of NGOs) in 1975; and the mobilization of regional and international opposition to the French resumption of nuclear testing in French Polynesia in 1996, which led to the cessation of the tests and to the US, UK and France becoming Treaty of Rarotonga signatories in 1996. (The US, however, has not yet ratified the three Treaty protocols, unlike the UK and France; see www.nti.org.)

Indigenous responses to nuclear testing are frequently informed by long-standing beliefs (as recorded in oral traditions and cosmologies) in the vital importance of a balanced relationship between humans and the environment (see Hauʻofa Citation2008, 71–77). Many Pacific religions, for example, feature deities who protect and inhabit particular realms of the natural world, and the spirits of the dead are, in many cases, believed to dwell within the bodies of particular birds or animals, or within other living entities such as trees. Environmental conservationism has been central to many Pacific subsistence economies for centuries, with intricate rituals and protocol (surrounding activities such as fishing and hunting) that have served to protect the fragile ecosystems upon which Pacific Islanders have depended for their survival (see Keown Citation2007, 89). These traditions have played a significant role in the emergence of a wide range of Indigenous Pacific protest literature produced in response to US and French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Below I offer a short summary of the historical circumstances of the testing, before going on to analyse the protest literature itself.

The US inaugurated the nuclear era with the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, closely followed by testing of atomic and later hydrogen bombs in the Marshall Islands from 1946 to 1958, with a final series of tests at Johnston Atoll and Christmas Island (by then an Australian territory) in 1962. France’s Pacific nuclear testing programme began later (1966), but its programme lasted much longer (periodically until 1996), generating a significantly larger proportion of regional and international protest, so I will begin with an overview of the French testing programme before returning to the US context.

When Algeria gained its independence from France in 1962, France was forced to end its nuclear testing programme in what is now the Algerian Sahara, and chose French Polynesia as its new testing site, establishing facilities on two atolls in the Tuamotu Island group: Fangataufa and Moruroa (known in French as Mururoa). In May 1966, the Centre d’Experimentation du Pacifique (CEP) began testing on Moruroa in spite of widespread local opposition, offering assurance that bombs would only be exploded when winds were blowing towards the south, where there were no inhabited islands nearby. For the first decade, France conducted atmospheric tests, in spite of the fact that the US, Britain and the Soviet Union had already signed a Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, agreeing to move their tests underground to reduce environmental pollution. As international protest against nuclear testing escalated in the 1970s, France finally abandoned atmospheric testing in 1975, first testing below the coral atoll and then under the lagoon, primarily in Moruroa. These tests caused immense environmental damage, creating cracks in the reef from which radioactive waste leaked into the ocean; in 1981, severe storms caused plutonium residues from the atmospheric tests to traverse the Moruroa Lagoon (Firth and von Strokirch Citation1997; Keown Citation2007, 96).

As knowledge of the adverse impact of French nuclear testing became more widely publicized in the 1970s, increasing numbers of newly independent Pacific island nations (as well as settler and indigenous communities in Australia and New Zealand) expressed vigorous opposition to the tests. The Conference for a Nuclear-Free Pacific, convened in Fiji in 1975, initiated an organized movement that came to be known as the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement (as noted above), and in the ensuing years the movement intersected with other campaigns against large-scale military manoeuvres, the testing of intercontinental ballistic missiles at Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, test bombing at Kahoʻolawe Island in Hawaiʻi, the mining of uranium in Australia, and the dumping of radioactive waste in the Pacific by Japan (Firth and Karin Citation1997, 355). In 1985 (the same year in which the Treaty of Rarotonga was drafted), the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior, which was about to travel to Moruroa to disrupt French nuclear tests, was bombed and sunk in Auckland Harbour by French government-sponsored saboteurs, provoking widespread international condemnation. In 1987, the New Zealand government instituted a strict ban on nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships visiting New Zealand ports, leading to New Zealand’s partial exclusion from the ANZUS pact, which had been formed between New Zealand, Australia and the US in 1951 to maintain security in each nation’s “sphere of influence” within the Pacific (see Keown Citation2007, 97).

While such events created severe schisms between the nuclear powers and white settler nations in the Pacific, they also prompted indigenous Pacific peoples to unite against the nuclear desecration of their homelands, triggering affiliations that transcended the geopolitical and linguistic divides that often hamper creative dialogue between, for example, anglophone and francophone Pacific writers. (This has particular significance given that it was the French explorer Dumont d’Urville who devised the tripartite geocultural division between Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia that still operates to this day [see Dumont D’Urville Citation1832].)

Maori artist Ralph Hotere, for example, made a significant gesture of solidarity with French Polynesians in his “Black Rainbow” series of lithographs and paintings produced in 1986, lamenting not just the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, but also the French nuclear testing programme that continued in the wake of the attack. Hotere’s work inspired Samoan author Albert Wendt (Citation1992) to write a dystopian novel, also entitled Black Rainbow, which establishes a homology between nuclear testing and other forms of environmental degradation and exploitation as a result of European incursion into the Pacific (see Keown Citation2005; Sharrad Citation2003; DeLoughrey Citation1999; Boyd, Citation2016).

French nuclear testing in the Pacific also precipitated substantial protests within French Polynesia itself – riots and demonstrations occurred throughout the 30-year testing period, for example – but France was able to maintain its operations largely by creating economic dependency within the region. In the early 1960s, the economy in French Polynesia was depressed, and the CEP brought prosperity through massive investment in infrastructure, customs revenue, local expenditure, and employment. However, these measures did not prevent the emergence of a wide variety of indigenous protest literature that emerged in French Polynesia and New Caledonia throughout the nuclear testing period. I have discussed much of this Ma‘ohi material – by poets and novelists such as Hubert Brémond, Henri Hiro, Charles Manutahi and Chantal Spitz – elsewhere (Keown Citation2007, Citation2010, Citation2014), so will here focus on Kanaky (indigenous New Caledonian) writer Déwé Gorodé as an example of a francophone Pacific author who, like Hotere and Wendt, has offered her support for the anti-nuclear efforts of her fellow (Ma‘ohi) Oceanians.

Gorodé is a significant figure to consider within this context of transoceanic anti-nuclear protest, as like many indigenous Pacific women she has been closely involved in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement. She was also one of the founders of Groupe 1878 (a Kanak independence movement named after a 19th-century indigenous uprising against French colonial rule), and when she was jailed in Camp-Est prison (in Noumea) for “disturbing the peace” during a 1974 sit-in at local law courts, she wrote two anti-nuclear poems: “Clapotis” (“Wave Song”) and “Zone Interdite” (“Forbidden Zone”). As the title of “Clapotis” (which could be translated more literally as “the lapping of water”) suggests, imagery of the sea is central to the poem, which begins by contrasting the sere, inhospitable environment of the prison exercise yard with the plentitude and dynamism of the sea beyond the prison walls. Anticipating Hauʻofa’s model of an interconnected Oceania, Gorodé posits the movement of the waves as conveying ripples of protest from Oceania’s easternmost island, Rapanui, against the violence of the Chilean political regime that holds jurisdiction over “Easter Island”, and subsequently bearing witness to the nuclear violence “infecting the sky” over Moruroa. The wave also holds the potential to “carry” indigenous Pacific peoples forward in their resistance to imperialism, gathering and imparting radical energies through its transoceanic trajectories (Gorodé Citation2004, 42).

Thus the poem establishes what Édouard Glissant terms a “poetics of relation”, a referential system that, rather than remaining rooted in individual national contexts, engages in a horizontal, transoceanic dialogue with other cultures, languages and value systems in its critique of colonialism (Glissant Citation1997, 44–46). Glissant’s theory (which takes the Caribbean as its main point of reference) is comparable to Hauʻofa’s in positing the sea as a basis for elaborating a regional, interpelagic identity, and as Elizabeth DeLoughrey has noted, Edward Kamau Brathwaite’s concept of tidalectics (another Caribbean theoretical model) is also a productive paradigm for analysing the “cyclic” ebb and flow of the Pacific, and of the diasporic populations that have moved across and within it (see Brathwaite Citation1991 and DeLoughrey Citation2007). DeLoughrey relates these theories primarily to anglophone Pacific literatures, but Glissant’s and Brathwaite’s work is also pertinent to the large corpus of francophone, hispanophone and indigenous-language material that has emerged from the successive waves of colonial and postcolonial encounter in the region, not least because an increasing amount of francophone Pacific literature is now available in English translation (see Keown Citation2010, Citation2014).

Notably, Gorodé’s “Wave Song” extends its poetics of relation not just to francophone and hispanophone cultures elsewhere in Oceania, but also to the internal politics of Chile in the 1970s, making reference to the deposing of Salvador Allende’s socialist government and the torture and murder of left-wing activists such as Victor Jara and Pablo Neruda. A tacit homology is established between Jara and Neruda (a musician and a poet persecuted for their political views) and Gorodé (writing poetry during her incarceration for involvement in the Kanaky self-determination movement). Chile’s internecine violence, enacted on its own nationals, is shown to be redolent of its colonial conquest of Easter Island/Rapa Nui, and resonates, in a tidalectic pattern of ebb and flow, with the waves of French colonial violence rippling out from New Caledonia, via French Polynesia, towards the easternmost point of Oceania and back again.

Gorodé’s “Zone Interdite”, also written during her 1974 imprisonment, reflects upon the stark contrast between “postcard” images of the Pacific paradise (centred on tropes of scantily clad, flower-adorned Polynesian female dancers) and the “forbidden” zones (such as Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls) where the nuclear fallout “poisons” Oceania, and transforms the watery Pacific into a realm of fiery destruction (“minant le Pacifique maintenant enfer”; Gorodé Citation1985, 17). “Wave-Song” also alludes to the fiery heat of nuclear explosions, contrasting the liquid mutability of the sea beyond the prison walls with the “overwhelming heat” of the sun, thereby invoking and transfiguring the “heliotropes” that (as DeLoughrey [Citation2011] notes) are widely evident in atomic discourse. In the early years of the US nuclear testing programme, politicians, journalists and other commentators figured the nascent atomic era as “a new dawn, a rising sun, and the birth of a new world”, positing the bomb “as the product of a new kind of divinity” achieved through technological innovation (DeLoughrey Citation2011, 246). Influential New York Times journalist William Laurence, for example, compared one of the early atomic bomb blasts in the Marshall Islands to “a gigantic white sun” harnessing the “awe of a new cosmic force”, and likened the mushroom cloud from the 1946 Baker test (the first underwater detonation at Bikini Atoll) to a gigantic tree of knowledge, thus positing man-made weapons of mass destruction as “ordained by nature, the cosmos, and divinity” (Laurence Citation1946, 280; DeLoughrey Citation2011, 247–248; see also Keown Citation2018).

Given that such rhetorical sleights of hand were used by Americans to deflect attention away from the destructive toxicity of the nuclear bomb, it is significant that Gorodé’s poem rejects this convention, pointing towards the deadly potential of the bomb in the references to the sun’s destruction of the fragile flora inside the prison yard. Here the sun’s heat seems unnatural: it “melts” the scent of flowers and “burns” their petals as they lie “dying on the sand” (“agonisant sur le sable”) of the exercise yard, like fish poisoned by nuclear radiation (Citation2004, 42). Gorodé’s heliotropes are redolent of those invoked in “No Ordinary Sun”, a 1964 anti-nuclear poem by Maori author Hone Tuwhare that also posits nuclear technology as a perversion of the generative power of nature. In Tuwhare’s poem, the detonating bomb appears as a “monstrous sun” that, rather than fostering growth through its light and warmth, creates apocalyptic destruction, encapsulated in the image of an anthropomorphized tree obliterated by the nuclear blast (Citation[1993] 1994, 28; see also Keown Citation2007, 93).

This recurring analogy between the sun and the nuclear bomb has a specific resonance within the context of US nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands, particularly with reference to the 1954 detonation of a hydrogen bomb codenamed BRAVO. As noted above, 23 nuclear tests were conducted on Bikini Atoll between 1946 and 1958, but the 15-megaton BRAVO bomb – 1000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima – was the largest and “dirtiest” ever tested by the US. Visible from 250 miles away, with a mushroom cloud stretching across 60 miles, the explosion vaporized three islands on Bikini Atoll, left a mile-wide crater through the reef, and spread radioactive fallout across a 50,000-square-mile area, including the inhabited northern atolls of Rongelap, Ailinglae and Utirik (Johnston Citation2015, 144–145). These islanders had no advance warning that the test was about to take place (though they had been evacuated for previous, smaller tests), and the day on which the BRAVO bomb was detonated was described as “the day of two suns” by Marshallese witnesses, because many of them mistook the orange glow of the explosion for a sunrise (Dibblin Citation1988). The irony of this misapprehension is explored in Tuwhare’s poem through imagery of destruction redolent of Romantic nature poetry, with the atomic age posited as a disastrous new phase in the history of industrialization. Tuwhare’s blending of solar and arboreal imagery is redolent of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Binsey Poplars” – “My aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled, / Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun” ([1879] Citation1985, 39) – and both poems condemn an imbalance in nature precipitated by human violence and hubris (see Keown Citation2007, 93).

The rupture in the natural order caused by the BRAVO bomb had devastating consequences for the people living downwind from the explosion. The nuclear fallout, which was mixed with pulverized coral, resembled snowflakes falling from the sky, and local children played in the debris, not realizing it was deadly “poison”, as the radioactive particles came to be known afterwards. The people of Rongelap, Ailinginae and Utirik were not evacuated from their islands for several days, and by the time they were taken to Kwajalein Atoll for medical treatment, they were suffering various symptoms of severe radiation poisoning, including vomiting, skin lesions and hair loss. Nuclear survivors such as Darlene Keju-Johnson and Lijon Eknilang, women who subsequently became international advocates for Marshallese nuclear justice, have reported a wide range of longer-term health problems affecting not just those Marshall Islanders directly exposed to the radioactive fallout, but also later generations. (Eknilang gave testimony at the 1992 inaugural World Uranium Hearing, and to the International Court of Justice in 1995, while Keju-Johnson addressed many international organizations, including the World Council of Churches in 1983, before her death from cancer in 1996.) From the 1960s and to this day, many islanders have developed thyroid tumours, blood and metabolic disorders, cataracts, cancers and leukaemia. Many women have experienced reproductive problems, including multiple miscarriages, stillbirths, and babies with severe birth defects; many have reported giving birth to “jellyfish” babies: children without bones, heads or limbs, and with transparent skin that reveals the organs underneath. These babies typically live for just a few hours before they stop breathing. Other women have reported giving birth to what look like bunches of grapes, while others have observed serious disabilities in surviving children, including musculoskeletal degeneration and lowered immunity to diseases (Eknilang Citation1998; Keju-Johnson Citation1987; Johnston Citation2015).

Many Marshall Islanders believe that they were deliberately exposed to fallout, so that US researchers could study the effects of radiation on human beings. These claims are corroborated by Holly Barker’s and Barbara Rose Johnston’s analysis of US documents declassified in the early 1990s, when an international investigation into the effects of radiation on the human body resulted in the US having to share information about its testing programme with the Marshallese government (Barker Citation2004; Johnston Citation2015). The documents reveal that just six hours prior to the BRAVO test, military staff were informed that the wind was blowing in the direction of inhabited atolls, but chose to detonate the bomb without evacuating the islanders, even though evacuations had taken place for previous, smaller nuclear tests (as noted above). Further, shortly after the tests took place, under the guise of humanitarian aid, the people of Rongelap, Ailinginae and Utirik were enrolled as human subjects in Project 4.1, a US scientific study of the effects of radiation on human beings. When the Rongelap people were returned to their contaminated atoll in 1957, studies of the biological consequences of living in a radioactive environment were undertaken without the informed consent of islanders under observation. Although US scientists assured islanders they were safe, grave concerns among the islanders about the longer-term health problems they were experiencing motivated them to evacuate their islands again in 1985 (when the Rainbow Warrior transported them to Mejatto Island, in Kwajalein Atoll, on its final voyage before being bombed in Auckland Harbour). By 2011, 79 people were resettled at Rongelap after partial decontamination of the atoll, but the majority of the Rongelap community are still living in exile (https://edin.ac/2pmqzCI). Some resettlement of Enewetak took place in 1980 after a partial clean-up operation by US servicemen (who removed contaminated topsoil and debris), but most of the islands in the atoll remain uninhabitable, and the Runit Dome, site of a bomb crater filled with radioactive waste and capped with concrete in 1979, is leaking radioactive material into the lagoon. The waste drifts downwind to nearby settlements and enters the food chain, causing ongoing health problems for local communities.

By the time the first international nuclear justice conference was held in Majuro in 2017, Marshall Islanders were still battling for more substantial efforts on the part of the US to decontaminate their islands, and to compensate their communities for the major displacements and health problems experienced as a result of nuclear testing and other military activities in the islands. (Kwajalein Atoll, for example, is still being used for US ballistic missile testing.) Some limited compensation has been paid to members of the four atolls (Rongelap, Utirik, Enewetak and Bikini) officially recognized by the US as having been directly affected by nuclear testing and fallout. A $150 million reparations fund was established, and in 1988 the RMI Nuclear Claims Tribunal began investigating and awarding compensation for personal injury and property damage (Johnston Citation2015, 148). But the funds set aside by the US have proved grossly inadequate: the Tribunal ruled that over $2 billion was owed to claimants, but was unable to pay over the vast majority of this once the reparations fund was exhausted. Further, the US reparations agreement made no provision for the 24 other atolls (some in the southern parts of the RMI, hundreds of miles away from the Cold War testing sites) that have also been contaminated by nuclear fallout (147).

Radiation poisoning has been described by eco-critic Rob Nixon (Citation2011) as a form of “slow violence”, a “delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space”. In discussing the “long dyings” that result “from war’s toxic aftermaths or climate change”, he notes that “the staggered and staggeringly discounted casualties, both human and ecological [ ... ] are underrepresented in strategic planning as well as in human memory” (1–2). As Nixon observes, such forms of slow violence are disproportionately evident in socio-economically deprived and formerly colonized communities, such as those Pacific Island nations suffering the consequences of British, French and US nuclear colonialism (33).

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner has sought, through her performance poetry and political activism, to make this “slow violence” visible to the global community. Though born in the Marshall Islands, Jetñil-Kijiner was raised in Honolulu, where a substantial Marshallese diaspora has formed since the 1986 Compact of Free Association between the US and the Marshall Islands (Lyons and Tengan, Citation2015). (The Compact ended the post-war US Strategic Trusteeship over the Marshall Islands and other parts of Micronesia, granting Marshall Islanders the right to work and live in the US in exchange for the continuing US military use of Kwajalein.) As a young woman, Jetñil-Kijiner became involved with the Honolulu-based Oceanic arts organization Pacific Tongues, and began experimenting with spoken word and slam poetry as a means by which to communicate her own experiences of racism (as a member of a stigmatized immigrant community), as well as drawing attention to the Marshallese nuclear legacy and the detrimental effects of climate change on the low-lying Marshall Islands (which average just two metres above sea level). Her work has reached a wide global audience through her blog and video-poems on the Internet, as well as her public appearances at international literary and climate change conventions. One of her first international appearances entailed representing her country at the “Poetry Parnassus” performance events during the 2012 Olympics, during which video recordings of her anti-nuclear poem “History Project”, and her eco-poem “Tell Them”, were made at the South Bank Centre in London. “Tell Them”, her first video-poem to be uploaded to the Internet, offers an impassioned response to the impact of rising sea levels on the Marshall Islands, and played a part in gaining her nomination for the role of Civil Society Speaker to the UN Climate Summit in New York in 2014. Watched by a global audience, she spoke powerfully about the impacts of climate change on indigenous island communities and offered a moving performance of her poem “Dear Matafele Peinam”, which considers the potential impact of climate change on future generations of Marshall Islanders through an intimate message to her young daughter.

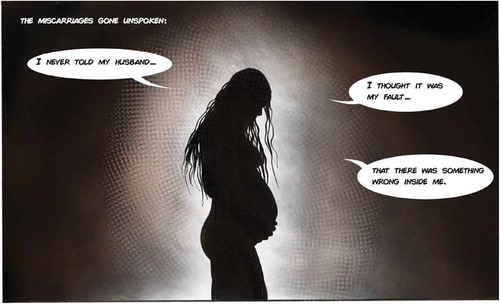

I have written at length elsewhere about “History Project”, one of Jetñil-Kijiner’s most searing and wide-ranging condemnations of US nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands (see Keown Citation2017, Citation2018). The poem explores her experience as a 15-year-old schoolgirl choosing to focus her school history project on the nuclear history of the Marshall Islands. She describes “sifting” through statistics and photographs recording the moment at which the Bikini community agreed to leave their atoll; a child suffering radiation injuries under observation by an apparently indifferent US scientist; animals left as test subjects on naval ships; and US marines and medical staff enjoying leisure time on Marshallese beaches. This American archive (the official “record”) is juxtaposed with the testimonies of Marshallese women giving birth to “jelly babies”, as well as suffering multiple miscarriages which they were too ashamed to reveal to their husbands for fear it would be seen as the women’s “fault”. The poem reflects on the injustice of the fact that nuclear tests described as being “for the good of mankind” had such devastating effects on Marshall Islanders and their environment. Using heliotropic imagery that resonates with the work of Gorodé and Tuwhare, Jetñil-Kijiner posits Marshall Islanders as martyrs for “all of humanity’s sins” which are “vomit[ed]” onto “impeccable white shores / gleaming / like the cross burned / into our open / scarred palms” (Citation2017, 22). Here, the nuclear explosion is figured as a blast of heat searing stigmata onto the bodies of islanders who were, ironically, persuaded to leave their homeland on the grounds of Christian duty and then sacrificed to the secular interests of a post-war US determined to achieve global dominance in nuclear weapons technology.

A striking feature of Jetñil-Kijiner’s poetry is her insight into the impact of nuclear imperialism upon women. In both “History Project” and her poem “Monster”, she engages directly with the trauma of women who, as a result of exposure to radiation (or descent from irradiated Marshall Islanders), give birth to “jellyfish babies”, or experience other reproductive problems. As Jetñil-Kijiner reveals, she wrote “Monster” partly as a result of reading Lijon Eknilang’s testimony on the effects of radiation on Marshallese women’s health, given at The Hague in 1995. As Eknilang notes, in finding names for reproductive problems that did not exist prior to nuclear testing, Marshallese women likened the “monster babies” to creatures from their marine environment, such as jellyfish, turtles and octupuses (International Court of Justice Citation1995, 27). These comparisons to creatures of the sea are significant, given that the “monster babies” emerged from the watery realm of the womb, and in this context it is also significant that some women described giving birth to what looked like “intestines”, using imagery redolent of Kristeva’s notion of the abject: here, the inside of the body becomes an externalized object – other, but also part of the self.

Jetñil-Kijiner’s “Monster” is laden with imagery of abjection drawn from the Marshallese legend of the mejenkwaad, a female demon that engulfs pregnant women, babies, and even whole islands and canoes within her monstrous jaws. In one of her blog posts, Jetñil-Kijiner explains that some Marshall Islanders believe the legend may have emerged as an allegory for postnatal depression, which can result in a kind of “deep sadness” and “madness” that inhibits bonding between mother and baby. Jetñil-Kijiner is candid about the ways in which this legend resonated with her own personal experience of postnatal depression, and speculates: “what if the mejenkwaad was not eating her child as a brutal act – but was instead attempting to return her child to her body – that in consuming her child, she was returning the child to her first home?” (www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/blog/). In the final lines of “Monster”, this neo-Kristevan return to the womb/chora is presented as an ultimate act of compassion by the mejenkwaad-as-mother reabsorbing a child deformed by radiation poisoning: “She kneels next to the body / and swallows” to “bring the child peace” (https://edin.ac/2MOGu5S). Here, the mejenkwaad is humanized as an embodiment of all the grieving Marshallese women who have experienced miscarriages or birth defects across the decades following the nuclear testing.

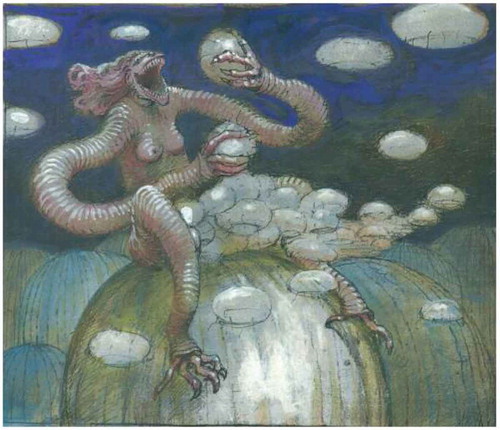

In various funded projects, I have collaborated with Kathy and two Pacific artists in making the “slow violence” of nuclear imperialism “visible” by transforming some of her poetry into graphic adaptations. In 2016, with Kathy’s permission and University of Edinburgh funding,Footnote2 I undertook the textual adaptation and storyboarding of “History Project”, which Māori-Niuean artist Munro Te Whata then transformed into a comic. Because neither of us is Marshallese, we avoided explicit representations of “jelly babies” (whose boneless bodies and skin “red as tomatoes” are referenced in the poem) for ethical reasons. As Eknilang points out, “Our culture and religion teaches us that reproductive abnormalities are a sign that women have been unfaithful to their husbands” (International Court of Justice Citation1995, 27), and Te Whata captured these sensitivities through the silhouetted (and therefore anonymized) image of a pregnant woman against a white background suggestive of the sudden flash of a nuclear explosion (see ).

This resonates with a section of “Monster”, where Jetñil-Kijiner imagines some unknown agent selecting Marshallese women to “Give birth to nightmares” and “Show the world what happens. When the sun explodes inside you” (https://edin.ac/2MOGu5S). Another heliotrope appears towards the end of the poem, as the mejenkwaad is figured as a woman “Turned monster from agony and suns exploding in her chest”, again posited as a victim of nuclear violence.

Such imagery informs a second graphic adaptation on which I have collaborated with Hawaiian artist Solomon Enos. In 2017, supported by a UK Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) award,Footnote3 we took a team of artists and researchers (including Kathy and Solomon) to the Marshall Islands to run a series of participatory arts workshops with Marshallese schoolchildren.Footnote4 Part of the project involved Solomon adapting “Monster” into a section of a graphic novel (exploring the Marshallese nuclear legacy) that he produced as a series of hand-painted panels (one of which features as the cover image of this special issue). In the panel representing the final lines of the poem, the mejenkwaad is depicted in the act of swallowing a large, luminescent egg suggestive not just of female fertility, but also of “jellyfish babies”, as the egg comes from a pile of other ovoid shapes, some of which appear to be drifting in water (like jellyfish), or perhaps manifesting as mushroom clouds following a nuclear bomb detonation (see ).

The globular structure on which the mejenkwaad is sitting is also evocative of the womb, and of the fecund “green globes of [bread]fruit” and “ripe watermelon[s]” Jetñil-Kijiner invokes in another anti-nuclear poem, “Anointed”, as a symbol of the vitality of Runit Island (in Enewetak Atoll) prior to the detonation of the nine nuclear bombs tested there during the Cold War. Here, the Runit Dome is represented both as a “tomb” representing the nuclear “death” of the island, and as an “empty belly” that is contrasted with the rounded abdomens of “women who could swim pregnant for miles beneath a full moon”. The water imagery in the poem is poignantly linked both with a lost fertility, but also with the nuclear contamination of the “rising sea” surrounding the island (and the plutonium-leaking dome), as climate change and nuclear violence converge in tides of devastation. This is counterpointed by references to the fiery heat of nuclear explosions, but also linked with the legend of the Marshallese trickster Letao, who first introduced fire by turning himself into kindling used by a small boy who “almost burned his village to the ground”. Letao’s capriciousness pales, however, in comparison to the terrible violence of the atomic era: this is a new “story of a people on fire”, and the poem ends with a question that invokes the biblical rhetoric once used to persuade the Bikini islanders to leave their homeland: “Who anointed them with the power to burn”? (https://edin.ac/2ppLHI1).

Our project team travelled to the Dome in February 2018 to film Kathy reading “Anointed”, and Daniel Lin’s resulting video-poem is replete with the contrasting fire and water imagery that pervades the text.Footnote5 We travelled hundreds of nautical miles to Enewetak and Bikini atolls on board the Okeanos RMI, a coconut-oil-powered walap (canoe) based on traditional Pacific designs, and footage of the ocean journey, as well as the islands we visited, pervades the film, with the sound of waves featuring prominently in the soundtrack.

To conclude: while nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) have been widely documented and news of them disseminated across the globe, the slow violence of radiation poisoning in the Marshall islands is barely registered outside the islands themselves – even within the continental US, according to Sasha Davis (Citation2015). Clearly Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner has been striving to make that hidden slow violence, as well as the detrimental effects of climate change (particularly rising sea levels) on low-lying Pacific islands, visible to a global audience, building on the work of Oceanic predecessors such as Hone Tuwhare and Epeli Hauʻofa. “Two Degrees”, the poem from which I quoted at the beginning of this article, is presented as a kind of creative manifesto registering Jetñil-Kijiner’s commitment to her task: she describes herself as “writing the tide towards / an equilibrium / willing the world / to find its balance”, reminding her global audience that Oceania is not an “empty” space, nor what has been dismissively termed by outsiders as the “hole in the doughnut” of the affluent Pacific Rim (Hauʻofa Citation2008, 42), but rather a vibrant, living space populated by people who, according to Jetñil-Kijiner’s ecopoetics, are “nothing without [their] islands” (Citation2017, 67). To paraphrase Derek Walcott (Citation1992), in Oceania “the sea is history”, but that sea is richly stocked with atolls and islanders, on the front line of climate change, whose stories teach vital lessons about the future of our planet.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle Keown

Michelle Keown is Senior Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh. She has published widely on Pacific and postcolonial literatures and theory, and is the author of Postcolonial Pacific Writing: Representations of the Body (2005) and Pacific Islands Writing: The Postcolonial Literatures of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Oceania (2007), and editor of Comparing Postcolonial Diasporas (2010) and Anglo-American Imperialism and the Pacific (2018).

Notes

1. Original Treaty signatories included Australia, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Western Samoa.

2. The funding took the form of an Innovative Initiative Grant, and we are also very grateful to Edinburgh’s School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures (LLC) for further funding that enabled the translation of the comic into Marshallese, and to Island Research and Education Initiative (iREi) for bearing the costs of printing copies of “History Project” for distribution within the Marshall Islands. An electronic copy of the comic is also available at www.map.llc.ed.ac.uk.

3. The Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) award was provided by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). The Global Challenges Research Fund scheme forms part of the UK’s Official Development Assistance commitment to promote the long-term sustainable growth of countries eligible for support from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

4. Fellow researchers and artists who worked on the Marshallese Arts Project include: Marcus Bennett (REACH-MI); Dr Polly Atatoa-Carr (University of Waikato); Olivia Ferguson (University of Edinburgh); Christine Germano (Constant Arts Society); Dustin Langidrik (Okeanos RMI); Sara Penrhyn Jones (Bath Spa University); Dr Alex Plows (Bangor University); Dr Shari Sabeti (University of Edinburgh); Aileen Sefeti (USP [The University of the South Pacific] Marshall Islands); and Dr Irene Taafaki (Director of USP Marshall Islands).

5. The video-poem can be viewed on Kathy’s blog (https://edin.ac/2ppLHI1) and various other Internet sites, including our GCRF-funded “Marshallese Arts Project” website (www.map.llc.ed.ac.uk).

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2001. “Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination.” In Globalization, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 1–21. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barker, Holly M. 2004. Bravo for The Marshallese: Regaining Control in a Post-nuclear, Post-colonial World. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Boyd, Julia A. 2016. “Black Rainbow, Blood-Earth: Speaking the Nuclearized Pacific in Albert Wendt’s Black Rainbow.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 52 (6): 672–686. doi:10.1080/17449855.2016.1165279.

- Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. 1991. “An Interview with Edward Kamau Brathwaite [With Nathaniel Mackey].” Hambone 9: 42–59.

- Davis, Sasha. 2015. The Empire’s Edge: Militarization, Resistance, and Transcending Hegemony in the Pacific. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 1999. “Towards a Post-Native Aiga: Albert Wendt’s Black Rainbow.” In Indigeneity: Construction and Re/Presentation, edited by James N. Brown and Patricia M. Sant, 137–158. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2007. Routes and Roots: Navigating Caribbean and Pacific Island Literatures. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2011. “Heliotropes: Solar Ecologies and Pacific Radiations.” In Postcolonial Ecologies, edited by Elizabeth DeLoughrey and George B. Handley, 235–253. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dibblin, Jane. 1988. Day of Two Suns: US Nuclear Testing and the Pacific Islanders. London: Virago.

- Dirlik, Arif. 1997. The Postcolonial Aura: Third World Criticism in the Age of Global Capitalism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Dumont D’Urville, Jules-Sébastian-César. 1832. “Sur les Îles du Grand Océan.” Bulletin de la Société de Géographie 17 (1): 1–21.

- Eknilang, Lijon. 1998. “Learning from Rongelap’s Pain.” In Pacific Women Speak Out for Independence and Denuclearisation, edited by Zohl Dé Ishtar, 15–26. Christchurch: Raven Press.

- Firth, Stewart, and von Strokirch Karin. 1997. “A Nuclear Pacific.” In The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders, edited by Donald Denoon and Malama Meleisea, 324–358. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Glissant, Edouard. 1997. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Gorodé, Déwé. 1985. Sous les cendres des conques. Nouméa: Edipop.

- Gorodé, Déwé. 2004. Sharing as Custom Provides: Selected Poems of Déwé Gorodé, edited and translated by Raylene Ramsay and Deborah Walker. Canberra: Pandanus.

- Hauʻofa, Epeli. 2008. We are the Ocean. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Hauʻofa, Epeli. 2000. “Opening Address for the Red Wave Collective Exhibition at the James Harvey Gallery, Sydney.” Unpublished paper given to the author by Hauʻofa.

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley. [1879] 1985. Poems and Prose. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics.

- International Court of Justice. 1995. Testimony of Lijon Eknilang to the International Court of Justice, The Hague, 14 November. www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/93/5968.pdf. 24–28.

- Jetñil-Kijiner, Kathy. 2017. Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Johnston, Barbara Rose. 2015. “Nuclear Disaster: The Marshall Islands Experience and Lessons for a Post-Fukushima World.” In Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities: A Postcolonial Approach, edited by Elizabeth DeLoughrey, Jill Didur and Anthony Carrigan, 140–161. London and New York: Routledge.

- Keju-Johnson, Darlene. 1987. “Ebeye, Marshall Islands.” In Pacific Women Speak, edited by Women Working for a Nuclear-free and Independent Pacific, 6–10. Oxford: Green Line.

- Keown, Michelle. 2005. Postcolonial Pacific Writing: Representations of the Body. London and New York: Routledge.

- Keown, Michelle. 2007. Pacific Islands Writing: The Postcolonial Literatures of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Oceania. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Keown, Michelle. 2010. “Littérature-Monde or Littérature Océanienne? Internationalism versus Regionalism in Francophone Pacific Writing.” In Transnational French Studies: Postcolonialism and Littérature-Monde, edited by Alex G. Hargreaves, Charles Forsdick, and David Murphy, 240–257. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Keown, Michelle. 2014. “‘Word of Struggle’: The Politics of Translation in Indigenous Pacific Literature.” In Language and Translation in Postcolonial Literatures: Multilingual Contexts, Translational Texts, edited by Simone Bertacco, 145–164. London and New York: Routledge.

- Keown, Michelle. 2017. “Children of Israel: US Military Imperialism and Marshallese Migration in the Poetry of Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner.” Special Issue “All That Glitters Is Not Gold: Pacific Critiques of Globalization,” edited by Melissa Kennedy and Janet Wilson. Interventions 19 (7): 930–947. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2017.1403944.

- Keown, Michelle. 2018. “War and Redemption: Militarism, Religion and Anti-Colonialism in Pacific Literature.” In Anglo-American Imperialism and the Pacific: Discourses of Encounter, edited by Michelle Keown, Andrew Taylor, and Mandy Treagus, 25–48. London and New York: Routledge.

- Keown, Michelle, and Stuart Murray. 2013. “‘A Sea of Islands?’ Globalization, Regionalism and Nationalism in the Pacific.” In The Oxford Handbook of Postcolonial Studies, edited by Graham Huggan, 607–627. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laurence, William. 1946. Dawn over Zero: The Story of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Lyons, Paul, and Ty P. Kawika Tengan. 2015. “COFA Complex: A Conversation with Joakim ‘Jojo’ Peter.” American Quarterly 67 (3): 663–679. doi:10.1353/aq.2015.0036.

- Niedenthal, Jack. 2013. For The Good of Mankind: A History of the People of Bikini and Their Islands. Majuro: Bravo.

- Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and The Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sharrad, Paul. 2003. Albert Wendt and Pacific Literature: Circling the Void. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Spivak, Gayatri. 2008. Other Asias. Malden, MA, and Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tuwhare, Hone. [1993] 1994. Deep River Talk. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Walcott, Derek. 1992. “The Sea Is History.” In The Oxford Book of the Sea, edited by Jonathan Raban, 500. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wendt, Albert. 1992. Black Rainbow. Auckland: Penguin.

- Wilson, Rob. 2000. Reimagining the American Pacific. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.