ABSTRACT

How can we conceptualize travel in search of fertility treatment? While current research on transnational reproduction mostly conceptualizes mobility as horizontal movement from A to B, this article shows how horizontal mobilities converge, contradict, and are interdependent with other forms of mobility; namely vertical mobilities in terms of social upward and downward mobility, representational mobilities in form of imaginative geographies, and the actual embodied experiences of mobility. Based on ethnographic research on the reproductive tourism industry in Mexico, the article explores the multiplicity of mobilities that constitute transnational reproduction. The article evaluates how the concept of multiple mobilities contributes to the study of medical tourism from a critical mobilities’ perspective.

‘Cancún baby’

As a Carioca [a woman from Rio de Janeiro], it first seemed weird to me that the boys always called me ‘Cancún baby’ when I started to work as a showgirl in the Zona Hotelera. But what I found even funnier was when I read a Facebook post from the intended fathers from Spain who had bought my oocytes that they were desperately waiting to pick up their ‘Cancún baby’ at the end of the month (interview with Angela, oocyte vendor, Cancún, April 2015).

Angela first came to Cancún from Rio de Janeiro to work as a showgirl in the city’s booming tourism sector catering to North American spring breakers who travel to Cancún in search of sun, beach and party. In May 2014, when the spring break was over and Angela’s pockets risked being as empty as Cancún’s hotel beds in low season, she agreed to take on a very particular sideline job. She joined the fast-growing workforce of women who offer their reproductive body parts and capacities as oocyte vendors or surrogate laborers in Mexico’s expanding fertility industry. Just as Angela came to Cancún in search for a better life, Ricardo and Paul – after years of coming to Cancún to enjoy the Caribbean sun during the European winter – were overjoyed to find that they could realize their life-long dream of their own baby with the help of Cancún’s surrogacy industry. Angela, as with Ricardo and Paul, first came to Cancún through the city’s tourism industry before they became part of its fertility industry, revealing the close connection between Cancún’s emerging fertility industry and its tourism sector. In this paper I argue we cannot separate the mobilities engendered by tourism from mobilities constituting the new global bioeconomy of assisted reproduction.

Embedded in its fertility tourism industry, Mexico emerged as a new destination for transnational surrogacy in 2013 (Schurr Citation2014; Schurr and Walmsley Citation2014) after several governments in South (East) Asia started to restrict their surrogacy industries – particularly for international and homosexual clientele (Parry Citation2015; Rudrappa Citation2017; Whittaker Citation2016). In Mexico, surrogacy used to be legal only in the State of Tabasco, but after the closure of the Indian and Thai surrogacy markets Mexico became more prominent on the global surrogacy map, and between 2013 and 2015 blossomed as a destination for gay surrogacy between 2013 and 2015. While there are limited official numbers, surrogacy experts have suggested there are several hundred cases per year, with intended parents coming mainly from North America and Europe and contracting mostly with Mexican surrogates. Single or gay men use either local Mexican donors or global egg donors from Eastern Europe or South Africa (Schurr Citation2017). In December 2015, the State of Tabasco banned surrogacy for foreign couples and gay men – following regulations in India where surrogacy is now also only feasible for Indian citizens in heterosexual living arrangements (Schurr and Perler Citation2015). Surrogacy (both for homo- and heterosexual international clients), however, continues to be practiced both within the State of Tabasco by a number of surrogacy agencies and in other states such as Quintana Roo and Mexico City.

This article calls for a careful scrutiny of the multiple mobilities constituting therapeutic travel in general and reproductive travel in particular. This article draws on critical mobilities studies to develop the notion of multiple reproductive mobilities, understanding mobility always as something more than the mere horizontal displacement of bodies and objects from A to B. It explores the convergences, interdependences, and contradictions between different forms, logics, and experiences of mobility in the field of transnational reproduction. By doing so, the article integrates a critical mobilities lens into the study of transnational reproduction, revealing the entangled power relations at play in the constitution of reproductive mobilities stemming from diverse ontological realms such as tourism, reproductive medicine, migration, and development. Focusing on the multiplicity of mobilities constituting reproductive travel, allows for a more holistic and less polemic analysis of transnational surrogacy.

The article first revisits the literature on transnational reproduction with regard to the question of how mobility is conceptualized. In the second section, I develop the notion of multiple mobilities drawing on critical mobilities studies and Annemarie Mol’s (Citation2002) work on multiplicity. The manner in which different logics of mobilities converge, contradict, and become interdependent with each other in Mexico’s reproductive tourism industry lie at the core of the empirical section of this article. The article concludes by evaluating how the concept of multiple mobilities contributes to the study of medical tourism from a critical mobilities’ perspective.

Revisiting mobilities in transnational assisted reproduction

Reviewing how mobilities have been conceptualized in the medical and reproductive tourism scholarship, I aim to show the need for a more extensive engagement with the multiple modes of mobility involved in transnational forms of medical and reproductive care. While patients have long travelled to other countries for medical treatment, the use of the term ‘medical tourism’ to describe this has become highly contested. Critics state that the term does not adequately capture the diverse experiences of medical travelers and overemphasizes the ‘touristiness’ of patient travel. As a consequence scholars have advocated for alternative terms such as ‘international medical travel’ (Kangas Citation2010; Whittaker and Leng Citation2016) and ‘transnational healthcare’ (Bell, Holliday, and Ormond et al. Citation2015) that emphasize the transnational geographies inherent in the practice, or ‘health mobilities’ (Hartmann, Kaspar, and Schurr Citation2016) foregrounding movement and mobility itself. Despite the diversity of terminology, the horizontal movement of people from their home to the destination where they are treated across geographical and political borders seems the common denominator to characterize this phenomenon.

Similar discussions over terminology can be found in the field of reproductive health travel; a specific realm within the broader field of medical travel characterized by the transnational consumption of assisted reproductive technologies. Martin (Citation2012, 1) defines reproductive tourism as ‘a contemporary practice in which people cross political and geographic borders – usually national – in order to access assisted fertility services and reproductive technologies’. The term ‘reproductive tourism’ has been scrutinized as academics, consumer groups, and medical staff have argued that it is derogatory to describe intended parents’ travels as a form of tourism, since it implies that intended parents are engaging in fun, leisurely activity, or that it makes light of the utter desperation that leads many to cross borders for assisted fertility services (Martin Citation2012, 2). Critics say that using the term reproductive tourism in academic or public debate plays into the hands of the fertility industry that employs the term for marketing purposes to downplay the risks, hopes, and emotions at stake in fertility journeys. In response, several alternative terms have been suggested including ‘cross-border reproductive care’ (Inhorn and Gürtin Citation2011; Shenfield, Pennings, and De Mouzon et al. Citation2011), ‘cross border fertility care’ (Nygren, Adamson, and Zegers-Hochschild et al. Citation2010), ‘reproductive exile’ (Inhorn and Patrizio Citation2009; Matorras Citation2005), ‘reverse traffic’ (Nahman Citation2011), and ‘transnational circumvention’ (Bergmann Citation2011). While all these terms suggest that the crossing of a national boundary and related regulatory frameworks lies at the heart of the phenomenon described, each term carries different connotations.

Pennings (Citation2005, 3571) coined the term ‘cross-border reproductive care’ arguing that it ‘is objective and descriptive since it holds no value judgment regarding the movements’. Pennings’s work focuses on the travels of fertility patients and other would-be parents across international borders in hope of fulfilling their dream of a baby and the care they receive abroad to assist them on their way to parenthood. Gamete donors and gestational surrogates who ‘assist’ these patients to fulfil these dreams often receive little in the way of care, however; ‘it must be acknowledged that “care” may not be part of the cross-border reproductive experience of all participants’ (Inhorn and Gürtin Citation2011, 668). In short, ‘cross-border reproductive care’ focuses exclusively on consumers and overemphasizes care in a market shaped more by economic interest than medical care. The term also does not address the fact that fertility treatment abroad is often sought out because of regulatory constraints in the home country.

Matorras (Citation2005) developed the term ‘reproductive exile’ to highlight exactly these regulatory constraints that ‘force’ parents to travel across borders to seek fertility treatments. Scholars advocating this term emphasize that reproductive travel is not necessarily an individual choice, but rather an ‘undeserved punishment’ (Inhorn and Patrizio Citation2009, 906) due to restrictive reproductive politics, long wait lists or a lack of access to certain technologies due to one’s sexual identity, marital status or medical situation. Both concepts – cross border reproductive care and reproductive exile – put the reproductive consumers’ border crossings at the center of the phenomena; the first underemphasizing the political and juridical context by highlighting the provision of care, the second overemphasizing regulatory frameworks that force consumers to cross juridical borders. Neither refers to those who provide the materials and labor for transnational reproduction.

Employing a critical mobilities lens to this phenomena demands that we integrate into our analysis those who provide reproductive tissues and become ‘bioavailable’ in the process of transnational reproduction (Cohen Citation2005)’ (Deomampo Citation2013, 516; Perler and Schurr Citationforthcoming). Michal Nahman (Citation2011) coins the term ‘reverse traffic’ to refer to the reversal of the usual mobility which focuses exclusively on reproductive consumers. The notion of ‘traffic’ implies the ‘trafficking of women and their donor gametes’ (Inhorn and Patrizio Citation2012, 510) across borders where they are ‘eggs-ploited’ (Pfeffer Citation2011) in a global bioeconomy which ‘outsources’ reproductive labor to certain women. The concept of ‘reverse traffic’ hence turns the ‘reproscope’ (Nahman Citation2016a) upside down, putting in its focus the reproductive travels and experiences of oocyte vendors and surrogate laborers rather than the cross-border movements of reproductive consumers. While the term ‘reverse traffic’ has come to stand for the travels of global egg donors (Kroløkke Citation2015; Vlasenko Citation2015), Nahman’s original work contains a broader understanding of this term, when she argues that ‘the doctors, embryologists, gametes, hormones and equipment all make transnational journeys rather than the patients’ (Nahman Citation2011, 627). ‘No people are moved around, only substance’ writes Nahman (Citation2016b, 83), highlighting that this practice seeks to circumvent the laws in some European countries against egg donation by ‘importing’ biological substances that ‘are not eggs, nor are they considered embryos yet’.

Bergmann (Citation2011, Citation2014) places the circumventive routes that fertility travelers and fertility experts alike employ to overcome national bans at the center of his work. Circumvention refers both to the geographical rerouting of fertility journeys which include travels across borders, as well as regulatory maneuvering between and across legal grey zones. Bergmann (Citation2011, 283) favors the term ‘circumvention routes’ over the term reproductive tourism as it represents the complex constellation of ‘traveling users, mobile medics, sperm and egg donors, locally and globally operating clinics, international standards, laboratory instruments, pharmaceuticals, biocapital, conferences and journals, IVF Internet forums, and differing national laws’. Like Nahman, Bergman points to the fact that not only reproductive consumers travel but also a whole range of other (non-)human actors ranging from biological substances to technologies, pharmaceuticals, and equipment. Nahman and Bergmann’s conceptualizations of reproductive travel firstly pay attention not only to reproductive consumers but also laborers, and secondly take account of the circulation of technologies, socio-technical devices, and biological substances. Bergman is in effect calling attention to the multiple human and non-human mobilities involved in transnational reproduction, a perspective which explicitly draws attention to the differential power relations at play with regard to the mobilities involved in reproductive travel – a central demand of critical mobilities studies. While the term ‘reverse traffic’ implies the reversal of a linear movement from A to B in search of services, the term ‘circumventive routes’ suggests the travels of reproductive agents are also framed by regulatory constraints and avoidance, and include detours, blind alleys, and circular movements.

Building on Nahman and Bergmann’s work, I propose the concept of reproductive mobilities as a conceptual lens to understand not only the multiplicity and multi-directionality of mobilities at play in the global fertility industry, but also how these mobilities are framed by various regulatory forces. Such a critical mobilities perspective serves to understand how differently marked human bodies, body parts, and body substances participate in this global industry, and how this participation in a (post)colonial (bio)economy is contextualized in terms of gender, sexuality, class, race, body ableness, and nationality.

I argue that even though physical movement across national borders from A (home country) to B (treatment country) is at the core of any definition of reproductive tourism, the resultant mobility itself remains under-theorized in scholarship on transnational reproduction. In the next section, I draw on critical mobilities studies and Mol’s (Citation2002) notion of multiplicity to further articulate my concept of multiple reproductive mobilities.

Rethinking reproductive tourism through the multiplicity of mobilities

As the editors of the special issue highlight in their introduction, ‘travelling across national borders to receive or to provide health care has transformed into a phenomenon with ample economic and social relevance’ (p.x). In face of the fast growing reproductive tourism industry, it is fair to say that assisted reproduction is a form of therapeutic mobility since ‘mobility is endemic to [reproducing] life’ (Kwan and Schwanen Citation2016, 243). Given the centrality of mobility to transnational reproduction, a critical mobilities approach to this empirical phenomenon is both timely and useful (Büscher, Sheller, and Tyfield Citation2016; Cresswell Citation2006, Citation2010, Citation2011; Sheller and Urry Citation2006, Citation2016; Söderström, Randeira, and Ruedin et al. Citation2013). The ‘mobility turn’ advocates for elevating mobility to a core concept within social science research. While recognizing the central role mobility has played in past societies and the development of the different disciplines, Urry (Citation2009, 479) argues that ‘thinking through a mobilities “lens” provides a distinctively different social science productive of different theories, methods, questions and solutions’. Critical mobilities often focus on ‘diverse mobile entities considered as problematic’ (Söderström, Randeira, and Ruedin et al. Citation2013, 9) in public discourse or by certain actors. The travels of Western parents to the Global South are one example of such a ‘problematic mobility’. In public discourse they are often considered ‘problematic’ as they take advantage of social inequalities and commodify the child (Schurr and Militz Citation2018). In this paper I argue that the interplay of mobility and power lies at the heart of critical analysis of (reproductive) mobilities. While scholars have looked at how interlocking power relations play out in transnational reproduction, my analysis focuses on how certain im/mobilities (re)produce, challenge, and contest the social inequalities shaping the power-laden global bioeconomy.

Paying attention to how global power relations are mapped out and enacted through the body, I ask how differently marked bodies in terms of class, gender, sexuality, race, nationality, dis/ability, etc. have different capacities to move and how the im/possibility to move across national borders marks bodies as ‘different’ in the first place (Ahmed Citation2000). Here, I take up in particular Cresswell’s (Citation2006, 249) concern about ‘how mobility for some is based on and assumes the immobility of others’. Framing mobility itself as ‘central to Western modernity’ (Cresswell Citation2006, 15), this article examines how postcolonial ideas around modernity shape im/mobilities in transnational reproduction. It asks how ideas related to modernity such as scientific and economic progress, development, and empowerment inform reproductive travels of both reproductive laborers and clients as well as the way the fertility industry portrays itself.

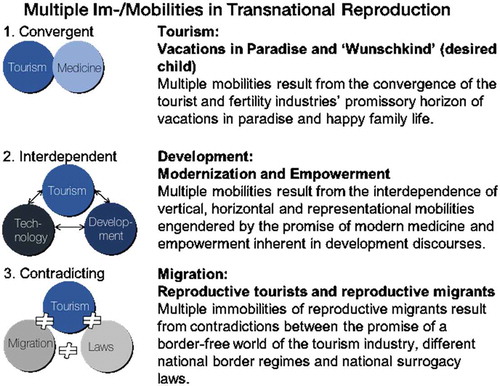

I develop in the following four different modes of mobilities that serve as an analytical tool to research the phenomena of medical and reproductive tourism in a critical fashion (see ). First, horizontal mobilities, represent the linear movement from A to B to access a service, the basic driver or producer of mobility. Such a positivist idea of movement through Euclidian space is often still at the heart of studies on medical and reproductive travelling, but as Cresswell (Citation2010, 16) argues ‘understanding physical movement is one aspect of mobility, [b]ut this says next to nothing about what these mobilities are made to mean or how they are practiced’. In short, horizontal movement is reduced to the actual physical movement from A to B; it sparks many questions (while providing few answers) about who and what is able to travel (or not) under which circumstances, what meanings are attached to these movements and how they are experienced by (non)human actors themselves.

Second, the concept of vertical mobilities allows to address the question, who is able to travel under which circumstances and to what ends? It refers to the material effects of upward or downward mobility as explicated in Ulrich Beck’s (Citation1986) sense of the ‘Fahrstuhleffekt’ (elevator effect). The study of gradients of inequality has long been central to mobility studies (Adey and Bissell Citation2010), with inequality conceptualized as the differential social distribution of mobility, which itself is a resource and capital. Inequality produces and is produced by the unequal access ‘to means of mobility and to know-how concerning technologies of mobility understood in a broad sense’ (Söderström, Randeira, and Ruedin et al. Citation2013, 7). This ranges from access to transportation and complex information and communication technologies to passports and visas.

Third, representational mobilities motivate horizontal and vertical mobilities. Practices like walking or taking a plane are not just ways of getting from A to B; they are, at least partially, discursively constituted. The productive potential of mobility is conveyed through a diverse array of imaginary geographies evoked through film, photography, marketing, and politics; representational mobilities therefore ‘capture and make sense of [these representations] through the production of meanings that are frequently ideological’ (Cresswell Citation2006, 3). Representational mobilities look at the meanings associated with mobility such as freedom, adventure, education, and modernity. While representational mobilities often motivate and evoke actual horizontal mobilities, they are more than a kind of ‘pre-mobility’. They rather shape and at the same time are shaped by the actual mobility across space (horizontal mobility) and society (vertical mobility).

Fourth, embodied mobilities engage with mobilities from a phenomenological and emotional perspective. They investigate the ways in which different bodies practice and experience mobilities. Asking how mobility is embodied is to ask how it feels to move, to be on the move, to be moved, whether it is comfortable or painful, forced, or free. Scholars exploring the embodiment of mobility (Mai Citation2012; Ormond Citation2013; Sheller Citation2004; Spinney Citation2015) have shown how the emergence and normalization of particular spatial/mobile practices ‘are deeply embedded in experiences of space and mobility through emotions, sensing, feeling and ambiences’ (Jensen Citation2011, 263). Further, work in the field of emotional geographies (Ho Citation2009; Pratt Citation2012; Richter Citation2015; Schurr and Militz Citation2018) has explored how ‘happiness, sadness, frustration, excitement and ambivalence […] accompany emplacement and mobility’ (Conradson and McKay Citation2007, 169). What’s central for my argument here is how differently marked bodies in terms of gender, sexuality, class, race, nationality, dis/ableness, etc. not only have different capacities to move but also actually affectively experience mobile practices and moments of immobility very differently according to their particular position in the global (bio-)economy. To pay close attention to how intersecting forms of social inequality and power relations shape im/mobilities in the fertility industry is crucial for a critical mobilities approach on reproductive tourism.

In practice, the actual horizontal movement from A to B, desires for and enactments of vertical mobility, the represented meanings attached to movement in space and within a societal hierarchy, and the embodied experience of im/mobility are all connected. The conceptual disentangling that follows serves to show the multiplicity of reproductive mobilities in terms of how different logics, representations, and practices converge, are interdependent and can contradict each other within reproductive tourism.

Focusing explicitly on the multiplicity of reproductive mobilities, I seek to reveal the complex and often contradicting logics at play in transnational reproduction and the effects these logics have on differently marked and positioned bodies who consume and labor in this industry. Developing such a critical mobilities lens on reproductive tourism reveals the power relations, manifold inequalities, and co-constitution of mobility and immobility in the workings of the global fertility industry. This critical analysis seeks to paint a more differentiated picture of reproductive tourism rather than either celebrating it as a new form of ‘cross border care’ or condemning it as a postcolonial form of ‘eggs-ploitation’.

My notion of multiplicity is indebted to Annemarie Mol’s (Citation2002) work outlined in the ‘The Body Multiple’. Mol’s (Citation2002, 83) ethnographic research in a Dutch hospital reveals how the disease of atherosclerosis is enacted, and she argues that ‘if we no longer presume “disease” to be a universal object hidden under the body’s skin, but make the praxiographic shift to studying bodies and diseases while they are being enacted in daily hospital practices, multiplication follows’. In analogy to Mol, I argue that if we study the enactment of different modes of mobilities, we are able to reveal the multiplicity of ontologies constituting the phenomenon of reproductive tourism. The question then is how these multiple modes are related as ‘far from necessarily falling into fragments, multiple objects tend to hang together somehow’ (Mol Citation2002, 5). Charis Thompson has coined the term ‘choreography’ to describe how multiple enactments of things belonging to different ontologies achieve to come together in the fertility clinic. The ‘choreographing’ work balances and juggles the ‘coming together of things that are generally considered parts of different orders (part of nature, part of the self, part of society)’ (Thompson Citation2005, 8). In short, a focus on multiplicity and the coordinating efforts of choreographing aims to show how diverse logics and practices belonging to different ontological spheres enact multiple mobilities. The focus on multiplicity expands the current focus in the field of reproductive tourism on the mere horizontal movement from home to destination country. Paying attention to the way different modes of mobilities involved in reproductive tourism are shaped by different ontological logics, it contributes to understand how different ontological logics enact power relations inhabiting multiple forms of mobility.

In the following section, I am not only interested in how different mobilities are saturated with different power-laden logics belonging to different ontological orders such as tourism, development, or migration, but also how these different logics converge, interdepend, and contradict (with) each other and by doing so affect the different actors involved in the fertility industry to different extent.

Methods

The empirical data on which my argument is based stems from ethnographic research conducted from December 2013 until April 2015 (a total of 6 months in four stays). Ethnographic research took place in fertility clinics, surrogacy agencies, and surrogate housing in Mexico City, Cancún, Villahermosa, and Puerto Vallarta, as well as at conferences and exhibitions of assisted reproductive technologies and surrogacy in Mexico City, Munich, Madrid, Barcelona, and London. 116 interviews were conducted in these different places with 21 physicians, 5 biologists, 11 psychologists/nurses responsible for egg and sperm donors, 15 agents of reproductive tourism, 10 CEOs of surrogacy agencies, 19 intended parents, 21 surrogates, and 14 egg donors. Intended parents, surrogates, and egg donors were recruited through multiple strategies ranging from contacts facilitated by surrogacy agencies and fertility clinics to recruitment through Facebook groups, surrogacy fairs and snowballing. Interviews were all conducted by myself in English, Spanish, or German and lasted between 40 min and 3 h. All interviews have been recorded, transcribed and analyzed with the qualitative data software Maxqda.

Convergent mobilities: all-inclusive holidays, ‘Wunschkind’,Footnote1 and vacations in paradise

Let us return to the intended fathers Ricardo and Paul whose story has opened this article. They have come to Cancún for years, considering that ‘this is a paradise on earth’ (interview, Cancún, January 2014). The imaginary geographies of Cancún’s white beaches, its eternal sun and the Caribbean turquoise sea, produced by the tourism industry, have first attracted them and finally dragged them all the way over from Spain to Cancún. Their decision to choose Cancún as a destination for their surrogacy journey is hence closely entangled with their vacation experience. They both loved the idea that ‘we would have the chance to spend a considerable amount of time in our little paradise, in our little timeshare flat in Cancún while doing all the necessary things to become parents: leaving a sperm sample, signing contracts, caring for our surrogate, and spending time with our newborn while waiting for her/his passport to be issued’ (interview, Cancún, January 2014).

It is the same narrative that reproductive tourism agencies and fertility clinics in Cancún love to spread: ‘You can combine your medical tourism in reproduction with the recreational tourism’Footnote2 writes a local fertility clinic on their website; a surrogacy agency claims that ‘the incredibly beautiful and sunny Cancún offers the perfect holiday and surrogacy packages’.Footnote3 The idea of literally an ‘all-inclusive holiday package’ including both the dream for a baby (Wunschkind) and a holiday in paradise is at the center of most marketing material the Mexican fertility industry produces. In framing fertility journeys within the context of holidays, the fertility industry normalizes the ‘problematic’ mobility of reproductive travel and the health risks associated with it for reproductive consumers and laborers alike.

This kind of marketing material evidences the convergence of the logics of two industries: the global fertility industry and the global tourism industry. The imaginary geographies of a paradise-like landscape and a beautiful pregnant body staged in front of this landscape both provoke desires: The desire to be in this paradisiac place, the desire for the child in the womb. In short, the representational mobility evokes desires to move, it sets people on the move; it inspires them to travel from their home country to Cancún (horizontal mobility) to fulfil their dream of their Wunschkind and their dream holiday at the same time. The imaginary geographies of a particular place (paradise Cancún) bring into being a particular representational mobility. The representational mobilities produced by the industry suggest that travelling to this place promises happiness, good mood, party, relaxation, etc. The representational mobility works not only as driver to move people in the first place but also shapes their actual embodied experiences of mobility as they measure their actual vacation experiences against the backdrop of these imaginary geographies. In doing so, we see the power held by players of the global fertility and tourism industry in shaping and manipulating through their marketing their consumers’ embodied experiences of passing a vacation in Cancún while consuming assisted reproductive technologies and services.

The tourism industry’s promise of a better – sunnier, more relaxed, happier – future converges with the ‘promissory horizon’ (Rajan Citation2006, 113), which can be considered the special feature of mobility in the area of reproductive technologies. Medical therapy with assisted reproductive technologies is marketized as ‘promissory capacity of ineffable intrinsic worth, which will unfold over the future life of a child’ (Thompson Citation2005). Given the fact that both the consumption of an all-inclusive holiday package and of assisted reproductive technologies are unpredictable (the hotel can be dirty, the weather rainy, the treatment may fail, the baby might have disorders) and everyday family life often fails to live up to representations about the ‘happy family’ (Ahmed, Citation2010), both industries work hard to make people believe in their promissory horizons. Successfully associating certain ideologies (progress, liberty, choice) and emotions (happiness) with the representational mobility of (reproductive) tourism is hence key to motivate people to move horizontally, to consume in the (reproductive) tourism industry.

As studies from historical to recent forms of tourism have shown, ‘moving between places physically […] can be a source of status and power’ (Sheller and Urry Citation2006, 213). Being able to afford a prestigious holiday serves to express or even elevate one’s social status. The constant need to share representations of one’s tourist mobility on social media is a sign of how the mobility itself serves as a means for social status. For many, not just the yearly holiday is crucial to their understanding of a happy life, but also the existence of a family, as an intended father narrates:

Already around twenty-four, we kind of were feeling ready to do it [to have a child], we had both managed to have successful careers as dancers. When we were twenty-six, we got married and then, you know, it’s just the process of life that you cannot really explain, we just wanted a child (interview with intended father, Switzerland, December 2014).

To have a family was part of his expectations of a happy life. According to Ahmed (Citation2010, 46): ‘The family also becomes a pressure point, as being necessary for a good or happy life’. The development of assisted reproductive technologies and their transnational consumption can ease infertile people from this pressure as they promise a way out of the life as an ‘unhappy queer’ (Ahmed, Citation2010, 88). They do, however, also increase the pressure on those not able to reproduce through their ‘technocratic imperative – if it can be done, it must be tried’ (Dumit and Davis-Floyd Citation1998, 7). While successful fertility treatment comes with the promissory horizon of a happy family life and its associated higher social status, it is important to take into account that destinations such as Mexico cater their surrogacy services to those who cannot (or no longer) afford fertility treatment/a surrogacy process in their home country and/or have no legal access to these services in their home country. Despite the significantly lower costs, I could observe during my fieldwork in Mexico that intended parents nevertheless often indebt themselves to finance their fertility/surrogacy journey to Mexico or lose their jobs while spending months in Mexico when medical or legal problems appear in the surrogacy journey. Hence, while many depart on their fertility journey in hope of increasing their social status, to respond to the social norm of the family by becoming parents, many actually suffer downward social mobility. The extent to which intended parents are affected by unsuccessful fertility journeys, surrogacy scams, or legal hazards often depends on their own social capital to mobilize their networks and pay for lawyers. National regulations, the advancement of LGBTQ-rights (e.g. maternity leave for gay people’s surrogate baby) and societal acceptance of alternative families in their home societies all shape the potential vertical upward or downward mobility experienced by intended parents with different national backgrounds, sexual orientations and class belongings.

The tourism and the fertility industry’s imaginary geographies of a happy family life and a dream vacation in paradise associate (representational) mobility with all kinds of positive emotions and experiences, which encourage consumers to travel to a certain destination (horizontal mobility). The successful convergence of horizontal and representational mobility in reproductive tourism is crucial to fuel people’s hopes and sustain their interest even in face of stories of treatment failure, medical side effects, legal hassles, and disappointments with regard to the quality of the medical and touristic experience, and failed families in terms of high divorce rates and patchwork families. In short, reproductive tourism must bolster the future oriented promise of happiness in order to overcome the threat that the promissory horizon of fertility treatment, a vacation or the aspired happy family life may fail. This threat shapes the logics and results in similar marketing efforts for both industries. The imaginary geographies of representational mobility must be guarded carefully in order to highlight the Mexican fertility industry’s therapeutic promissory horizon rather than associate the country with any kind of negative press (Mexico as a violent holiday destination, Mexico as a destination for surrogacy scams). The image of Mexico as a destination for therapeutic travel is crucial in order not to endanger the aspired horizontal movement of intended parents.

Interdependent mobilities: making modern Mexico and empowering poor women

Reproductive tourism is definitively a win-win situation: the intended parents profit from the first world technology at third world cost and the poor surrogates earn a fortune they would not be able to gain in other kinds of jobs (interview with medical agent, Cancún, January 2014).

This quote reproduces a dominant narrative in the surrogacy industry: market actors and intended parents alike frequently justify their participation in the surrogacy industry through framing their travels to reproductive tourism destinations in the Global South in terms of compassion and development aid. The quote begins by constructing Mexico as a modern nation. In comparing its technological standard to other Western countries and referring to them as ‘first world’, a term that by now is often perceived as politically incorrect and stems from the Cold War area, Mexico is pictured as a modern, developed nation with regard to its medical sector. Promoting Cancún as a (medical) tourism destination, medical agents often emphasize that ‘Cancún is a city built for the US-American tourist. It is like any other Southern American City, you have Wal-Mart, a Starbucks at every corner. It is clean, white; the only difference to an US city is that it is surrounded by the beautiful Caribbean Sea’ (interview with medical agent, Cancún, January 2014).

The fertility industry, in a similar vein, does not become tired of repeating that treatment and success rates in Mexico do not differ from the US or Europe. This is done by highlighting, first, that ‘most of the fertility doctors here in Mexico have been trained in the US or in Spain’ (interview with IVF physician, Cancún, August 2014); second, that ‘if you look at the technology we use, it is the same machines, the same ultra-sound machine, the same ICSI microscope that you see in IVF clinics in the US, Spain or Germany’ (interview with IVF physician, Mexico City, December 2013); and third, that therefore the success rates are exactly the same – or some claim even higher – than in other countries in the Global North. In short, just like in India (Rudrappa and Collins Citation2015, 953), reproductive tourism in Mexico is promoted through the slogan ‘First World medicine at Third World prices’.

The representational mobility produced through these discourses combines ideologies of scientific progress and modernization with a reproductive labor outsourcing economy where women earn a fraction of what surrogate mothers would in western countries where commercial surrogacy is legal. Mexico secures horizontal mobility by investing in becoming a destination for reproductive tourism with high technological standards, Western medical expertise and low costs. Representational mobility supports this by offering the allure of a vacation while becoming a family, however, this veils the reality that only certain bodies have the capacity to make this journey. Mexican same sex couples, for example, rarely have the financial means to contract a surrogate laborer.

In its second part, the quote frames the consumption in the Mexican surrogacy industry as a form of development aid. This narrative, just like the first one, has also travelled from India’s surrogacy industry (Rudrappa and Collins Citation2015) together with the multinational agencies offering surrogacy in different destinations in the Global South to Mexico (Müller and Schurr Citation2016). In India, clients often insist that ‘What makes me happy about my decision is that the [life] of my surrogate would change with the money. Without our help, her family would not be able to get out of the situation they are in, not even in a million years’ (Pande Citation2014, 100). The intended parents I interviewed in Mexico reproduced a similar narrative when highlighting that ‘we decided to go for Mexico because we felt that with the same money, a surrogate mother in the US perhaps treats herself to a spa or takes her family to Disney Land, but here in Mexico, our money really transforms the life of a whole family’ (interview with intended father, Puerto Vallarta, April 2015).

The intended parents assumed that the largest part of the money they had paid to the agency – between USD 38,000 and USD 57,000 – would go to the surrogate mother, very few were aware of how much a surrogate mother actually ‘earned’ through her surrogate labor, and were surprised when they heard the surrogate earned as little as USD 12,000–16,000. Mexican law prohibits the commercialization of body parts, and ‘compensation’ is the preferred term employed by agencies in order to frame surrogate labor as a form of altruism. One surrogacy professional highlighted: ‘When we calculated the compensation, we aimed at helping the surrogate climb up one “quintile” [in her socio-economic status] that means, if now she belongs to the poorest quintile of the Mexican population, we want to push her up to the second quintile, towards the lower middle class’ (interview with surrogacy professional, Cancún, September 2014).

This surrogacy professional makes clear that intended parents’ travels to Mexico are supposed to result in some form of social upward mobility for the reproductive laborers. At the same time, the Mexican surrogacy industry seduces reproductive laborers to travel from all parts of Mexico and especially from poor States like Chiapas to Cancún by promising them an apparently ‘fast gained fortune’. We see here not only the interdependences between the consumers’ and the reproductive laborers’ mobility but also between horizontal and vertical forms of mobility. Women can just profit from this new possibility of upward mobility if there are consumers willing to fly to Mexico to fulfil their dreams of a baby. At the same time, intended parents can only realize their dream of the desired happy family life, if Mexican women are willing to travel to Cancún to offer their reproductive labor in search of social upward mobility.

As much as these different forms of mobilities are interdependent, one kind of mobility does not necessarily engender the other. Lidia, for example, a single mother of a two-year-old, had travelled together with her daughter from her hometown to one of the surrogate houses in Cancún, hoping to offer her daughter a better future with the help of the money she would receive by being a surrogate mother. She spent eight months in Cancún, but after several failed embryo transfers, she returned to her hometown with as little money as she had left it. Maria, another surrogate mother, was more fortunate. She successfully completed her first surrogacy contract and was able to pay off the medical debts her chronically ill mother had accumulated. In hope of some form of social upward mobility, Maria embarked on her second journey. She did receive the money when she handed over the baby to the intended fathers from the US, but unfortunately, three months later their dream of a happy family life abruptly ended when the baby died in a neonatal care unit in a private hospital in Villahermosa, Tabasco. The Spanish parents underwent psychological therapy to deal with their loss and have now embarked on a new surrogate journey in Kiev, Ukraine. Maria, the surrogate mother had no access to psychological counselling and was left alone to deal with her trauma about the death of the baby. These are just two of many examples where some forms of horizontal mobility did not meet the promises made through representational mobility, of happy family life. Intended parents and surrogates have different capacities to deal with unexpected events such as the loss of the baby due to their particular situation in the global (bio)economy.

Contradicting mobilities: (Im)mobile repro-consumers and – laborers

Both the tourism and the medical/reproductive tourism industry generate an impression of the world as a border-free place. Maps of medical tourism suggest that (medical and reproductive) tourists can move freely to any country in the world in search for the perfect holiday or (fertility) treatment experience. The tourism and medical/reproductive tourism industry’s logics converge in associating ideas about free movement and a borderless world to the representational mobilities they promote. Agencies portray transnational surrogacy journeys as straightforward and made possible through the modern comforts of globalization such as cheap air travel, new information and communication technologies, international banking services and the spread of English as a global language.

These representational mobilities, however, contradict sharply with the embodied mobilities reproductive consumers actually experience. Depending on their citizenship, the laws regarding (commercial) surrogacy in their home and in the destination country, and the support they receive (or not) from their surrogacy agency, local authorities and their embassy, reproductive journeys are marked by different intensities of border regimes. As the majority of intended parents travelling to Mexico for surrogacy come from Northern America, Latin America, or Europe, most of them have no trouble getting visas to enter Mexico. It is rather at the moment when they want to return home with their baby that national borders appear as obstacles to the smooth flow of their surrogacy journey, as an intended father from California laments: ‘Our baby was born after the change of law. The civil registry in Tabasco doesn’t want to issue the birth certificate. We are here for four months now. I had to quit my job and Andrew is flying back and forth between Los Angeles and Cancún to help me take care of the twins. I never thought it would be so difficult to bring back the twins, I mean it was so easy to bring our embryos from LA to Cancún and now they make such a fuss’ (Skype interview, June 2016). The apparently borderless world of (reproductive) tourism contradicts here with the horizontal and embodied immobilities of these intended fathers and their babies. When borders become impermeable through national border regimes, reproductive consumers turn into migrant-like subjects who are dependent on the mercy of national and local authorities and their willingness to issue the necessary papers such as a birth certificate or a passport to cross national borders.

Borders often become insuperable obstacles in moments when things go wrong in the surrogacy process. On the one side, medical complications may occur where babies are not able or allowed to travel due to their premature birth, severe illness or disabilities. On the other side, legal issues such as the prohibition of surrogacy in the home country or a change of law in the destination country may complicate horizontal mobility across national borders. Legal changes, such as in the civil code of the State of Tabasco, the only State in Mexico were surrogacy used to be legal, have now prevented intended parents from a fast return to their home countries. Intended parents, like the one quoted above, often spent months in this immobile state while waiting for travel documents. Their horizontal mobilities that were supposed to be characterized by fast and effortless movements across borders result then in new forms of embodied immobilities shaped by waiting, anxieties, distress, and uncertainty. Depending on their social capital, class and citizenship status as well as their sexual orientation, they have different capacities to escape, shorten, or make their times of waiting more comfortable.

Not only intended parents, however, experience embodied forms of immobility that sharply contradict with the representational mobilities promoted by the reproductive tourism industry suggesting effortless horizontal movements. Reproductive laborers, due to their less privileged economic, racialized, and citizenship status, often experience moments of immobility that can be life threatening: ‘We were seduced with the images of Cancún. I mean for every Mexican it is a dream to visit once in your life Cancún. But it turned into a nightmare. We were locked into the surrogate house; we were not allowed to leave the house. There was not enough food. I tried to contact my [intended] parents, but the agency didn’t even tell me their names’ (interview with surrogate mother, Cancún, January 2014). The imaginary geographies of Cancún, the representational mobility promising life in paradise promoted by (reproductive) tourism agencies lure reproductive consumers and laborers alike to Cancún. But for some, this dream turns into a nightmare. This is nowhere more evident than in the scam around the US-based surrogacy agency ‘Planet Hospital’. Having offered medical and reproductive services in India for over ten years, Planet Hospital’s CEO Rudy Rupak was among the pioneers to offer international surrogacy in Mexico. By 2013, the company went bankrupt, but not before he had betrayed a dozen intended parents who had wired their money without any service in return. Media reports have portrayed this surrogacy scandal ‘as a cautionary tale about the proliferation of unregulated surrogacy agencies […] and their ability to prey on vulnerable clients who want a baby so badly that they do not notice all the red flags’ (Lewinjuly Citation2014). These heart-breaking stories on the fate of the intended parents veiled the effects of the scandal on the surrogate mothers in Mexico who were locked in their shanty surrogate hostel without food supplies and any information on what was happening. The intended parents affected by the scandal organized themselves and a lawyer among them initiated a lawsuit and an FBI investigation against Rupak in the US. For some of the intended parents, the financial loss they experienced meant the end of their surrogacy journey, but many moved on to other destinations or agencies to continue their quest to parenthood. The surrogate mothers, in contrast, were left to their own fate. Some of them managed to get in touch with their intended parents, others returned home after months of waiting in the surrogate hostel, with even less money than before. Most of them never saw any form of financial compensation.

What this case shows is that intended parents are able to resort to more social capital and a wider support network (e.g. through support from the intended parents’ online community or their professional networks) than the reproductive laborers who often enter the world of surrogacy without anyone in their families or social networks knowing that they will do so. They do not count on any type of legal support and frequently face enormous economic pressures. While the Planet Hospital case is for sure an extreme case that does not represent the overall experience of most surrogate mothers in Mexico, especially those surrogate mothers who lived in surrogate housing experienced some form of control over their embodied mobilities, having to follow strict rules regarding when they were supposed to exercise, to return home, or to rest.

Different forms of mobility and immobility are hence highly stratified in the sense that consumers and laborers – depending on their classed, racialized, sexualized, nationalized, and gendered identity and the particular economic, political, and institutional context in which they are embedded – have different capacities and resources to move or to liberate themselves from states of (forced) immobility. When we focus on moments of immobility, the contradictions between the logics of a borderless world saturating representational mobilities, the promise of a better life thanks to upward social mobility and the actual embodied experiences of (im-)mobility by consumers and laborers become evident.

Recognizing the multiplicity of mobilities constituting global therapeutic landscapes

This article argues for recognizing the multiple mobilities constituting the phenomenon of reproductive tourism. In this conclusion, I first summarize the main findings of the paper to make the multiplicity of reproductive mobilities visible. In a second step, I connect the case study discussed in the paper to the overall questions of the special issue by asking how my concept of multiple mobilities can inform the notion of therapeutic mobilities put forward in this special issue.

The concept of multiplicity has been used to describe the ‘multiple geographies of reproductive tourism’ (Deomampo Citation2013) that emerge through the increasing global demand for reproductive technologies, the willingness of reproductive consumers to cross national borders to access them, and the readiness of reproductive laborers to travel to sell their reproductive body parts and labor. In short, research on reproductive tourism has mainly focused on how the mobilities of different human bodies ranging from consumers to laborers and health professionals bring into being the global phenomenon of reproductive tourism. Others have emphasized that not only humans but also non-human actors are on the move to bring the global assemblage of reproductive tourism into being (Müller and Schurr Citation2016; Parry Citation2008; Parry, Greenhough, and Brown et al. Citation2015): medication, medical, and laboratory equipment, patients’ records, money, business models, therapies are among the material ‘mobile prosthetics’ (Bissell Citation2010; Ormond Citation2013) that all have different capacities and face different difficulties when crossing borders.

In this article I have built on this body of scholarship to advance my notion of multiple mobilities looking not only at the multiple actors that are on the move but also at the multiple logics and practices at play in reproductive tourism.

Convergent promises of mobility

I have shown in the first step how reproductive tourism is based on the multiple promises of happiness resulting from the horizontal movement from A to B: if you travel to Cancún you will not only realize your dreams of a holiday in paradise but also of your Wunschkind. The logic of the tourism industry and the global fertility industry converge in their promissory horizon of a better life, respectively a happier life as a family. They do so by linking one’s horizontal mobility to her/his vertical mobility as they stage the mobility to Cancún and the mobility to become a parent as a gain in social status and prestige.

Interdependent practices of mobilities

In the second step, I have shown that different types of mobilities not only converge but are actually interdependent. The vertical social upward mobility of reproductive laborers depends on successfully mobilizing positive representations of Mexico as being high-tech, modern, but cheap as the main driver to attract intended parents to consume in Mexico’s reproductive tourism industry. The horizontal mobility of reproductive consumers at the same time interdepends with the horizontal mobility of reproductive laborers who in search for social upward mobility travel to Cancún to offer their reproductive body parts and services and vice versa.

Contradicting experiences of Im/mobilities

In the third step, I have argued that multiple immobilities emerge from the contradictions between the representational mobilities promoted by reproductive tourism associating mobility with a free flow across space and the actual embodied experiences of mobility shaped by border regimes, national regulations of reproductive technologies, and medical precarities. The promissory horizon of the (reproductive) tourism industry of realizing one’s dream of a vacation in paradise and for a Wunschkind contradicts in practice when medical or legal obstacles appear in the process, when treatment fails, the baby suffers disabilities, or legal changes or illicit activities complicate the mobility of reproductive consumers and laborers, condemning them to forms of immobility, stillness, and waiting.

How can my conceptualization of medical mobilities as multiple (see ) contribute to the debates around therapeutic mobilities at the center of this special issue? It urges scholars to think of the multiplicity of mobilities beyond the actors inhabiting the mobility. It is of course important to recognize that ‘therapeutic mobilities combine movements of humans and things’ (special issue introduction). But this article argues that to research therapeutic mobilities from a ‘critical mobilities’ (Söderström, Randeira, and Ruedin et al. Citation2013) perspective, we need to pay attention not only to the multiplicity of actors travelling but also to the multiplicity of modes of mobility and how and why they are constituted. We need to expand our focus from the mere horizontal movement from A to B to the representational, vertical, and embodied mobilities and how these different modes of mobilities converge, become interdependent and contradict each other in the global spaces of medical tourism. Looking at how horizontal mobilities are entangled with representational mobilities, interdependent with vertical mobilities and are shaped by embodied mobilities also serves to recognize that the horizontal movements at the center of medical tourism are not linear but rather messy, multi-directional mobilities saturated by specific national contexts and their legal regulations, national health care systems, and culturalized ideologies of care and cure.

Lastly, when we analyze horizontal and representational modes of mobilities together with vertical and embodied modes of mobilities, questions of social inequality, power and agency are brought to the center of any analysis of the phenomenon of medical tourism. Focusing on moments of immobilities, on differently marked bodies’ (in)capacities to become mobile and to cross national borders reveals much about the power relations saturating medical tourism. For any study of therapeutic mobilities to turn into ‘critical mobilities’, a critical assessment about the stratification of mobilities along axes of gender, sexuality, marital status, race, ethnicity, class, education, nationality, citizenship status, dis/ability, etc. is key. Such a critical analysis of therapeutic mobilities is facilitated by paying attention to the way multiple modes of mobilities converge, are interdependent and contradict, in short by paying attention to the multiplicity of mobilities itself.

Acknowledgments

I would first like to thank the surrogate mothers, oocyte donors, intended parents, medical staff, and surrogacy professionals who have kindly shared their experiences in and with the global fertility industry in Mexico with me. A generous grant from ‘The Branco Weiss Fellowship – Society in Science’ has made this translocal project possible. I am grateful for the intellectual stimulation of the research group ‘Transcultural Studies’ – namely Laura Perler, Elisabeth Militz, and Suncana Laketa – who during one of our retreats have helped me to shape my ideas around multiple mobilities. The critical questions of the hiring committee at the University of Passau where I presented the first draft of this article have further helped to mold this article. The paper has been written during an Erasmus Faculty Exchange at the Centre Norbert Elias in Marseille and the IMERA Marseille. Lastly, I want to thank the special issue organizers Heidi Kaspar, Margaret Walton-Roberts, and Audrey Bochaton for inviting me to contribute to this special issue and their extensive editing work that significantly improved the quality of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. German for planned child, but literally desired child, which for me comes closer to the desires saturating consumption in the fertility industry.

2. http://www.fertilitycentercancun.com/blog/medical-tourism-assisted-reproduction/ (last accessed 27 November 2017).

3. https://www.newlifemexico.net/fertility-blog/2017/11/09/ten-reasons-surrogacy-cancun/ (last accessed 27 November 2017).

References

- Adey, P., and D. Bissell. 2010. “Mobilities, Meetings, and Futures: An Interview with John Urry.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 1–16. doi:10.1068/d3709.

- Ahmed, S. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Postcoloniality. London: Routledge.

- Ahmed, S. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Beck, U. 1986. Risikogesellschaft. Frankfurt a.M. Suhrkamp.

- Bell D, Holliday R, Ormond M, M Ormond, and T Mainil 2015. “Transnational Healthcare, Cross-Border Perspectives.” Social Science & Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.014.

- Bergmann, S. 2011. “Fertility Tourism: Circumventive Routes that Enable Access to Reproductive Technologies and Substances.” Signs 36: 280–289.

- Bergmann, S. 2014. Ausweichrouten der Reproduktion. Biomedizinische Mobiliät und die Praxis der Eizellenspende (German). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Bissell, D. 2010. “Passenger Mobilities: Affective Atmospheres and the Sociality of Public Transport.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 270–289. doi:10.1068/d3909.

- Büscher, M., M. Sheller, and D. Tyfield. 2016. “Mobility Intersections: Social Research, Social Futures.” Mobilities 11: 485–497. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1211818.

- Cohen, L. 2005. “Operability, Bioavailability and Exception.” In Global Assemblage: Technology, Politics and Ethics as Anthropological Problems, edited by A. Ong and S. J. Collier, 79–90. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Conradson, D., and D. McKay. 2007. “Translocal Subjectivities: Mobility, Connection, Emotion.” Mobilities 2: 167–174. doi:10.1080/17450100701381524.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 17–31. doi:10.1068/d11407.

- Cresswell, T. 2011. “Mobilities I: Catching Up.” Progress in Human Geography 35: 550–558. doi:10.1177/0309132510383348.

- Deomampo, D. 2013. “Gendered Geographies of Reproductive Tourism.” Gender & Society 27: 514–537. doi:10.1177/0891243213486832.

- Dumit, J., and R. Davis-Floyd. 1998. “Introduction: Cyborg Babies. Children of the Third Millenium.” In Cyborg Babies: From Techno-Sex to Techno-Tots, edited by J. Dumit and R. Davis-Floyd, 1–18. New York: Routledge.

- Hartmann, S., H. Kaspar, and C. Schurr. 2016. “Health Mobilities.” Feministisches Geo-RundMail 52.

- Ho, E. L.-E. 2009. “Constituting Citizenship through the Emotions: Singaporean Transmigrants in London.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99: 788–804. doi:10.1080/00045600903102857.

- Inhorn, M., and Z. Gürtin. 2011. “Cross-Border Reproductive Care: A Future Research Agenda.” Reproductive BioMedicine Online 23: 665–676. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.08.002.

- Inhorn, M., and P. Patrizio. 2009. “Rethinking Reproductive “Tourism” as Reproductive “Exile”.” Fertility and Sterility 92: 904–906. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.055.

- Inhorn, M. C., and P. Patrizio. 2012. “Procreative Tourism: Debating the Meaning of Cross-Border Reproductive Care in the 21st Century.” Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology 7: 509–511. doi:10.1586/eog.12.56.

- Jensen, A. 2011. “Mobility, Space and Power: On the Multiplicities of Seeing Mobility.” Mobilities 6: 255–271. doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.552903.

- Kangas, B. 2010. “Traveling for Medical Care in a Global World.” Medical Anthropology 29: 344–362. doi:10.1080/01459740.2010.501315.

- Kroløkke, C. 2015. “Have Eggs, Will Travel: The Experiences and Ethics of Global Egg Donation.” Somatechnics 5: 12–31. doi:10.3366/soma.2015.0145.

- Kwan, M.-P., and T. Schwanen. 2016. “Geographies of Mobility.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106: 243–256.

- Lewinjuly, T. (2014) A Surrogacy Agency That Delivered Heartache. The New York Times.

- Mai, N. 2012. “Embodied Cosmopolitanisms: The Subjective Mobility of Migrants Working in the Global Sex Industry.” Gender, Place & Culture 20: 107–124. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2011.649350.

- Martin, L. J. 2012. Reproductive Tourism. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization, 1–5. Malden, MA and Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- Matorras, R. 2005. “Reproductive Exile versus Reproductive Tourism.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England) 20. doi:10.1093/humrep/dei223.

- Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Müller, M., and C. Schurr. 2016. “Assemblage Thinking and Actor-Network Theory: Conjunctions, Disjunctions, Cross-Fertilisations.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41: 217–229. doi:10.1111/tran.2016.41.issue-3.

- Nahman, M. 2011. “Reverse Traffic: Intersecting Inequalities in Human Egg Donation.” Reproductive BioMedicine Online 23: 626–633. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.08.003.

- Nahman, M. 2016a. “Reproductive Tourism: Through the Anthropological “Reproscope”.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 417–432. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-030459.

- Nahman, M. 2016b. “Romanian IVF: A Brief History through the ‘Lens’ of Labour, Migration and Global Egg Donation Markets.” Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online 2: 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.rbms.2016.06.001.

- Nygren K, Adamson D, Zegers-Hochschild F, et al. 2010. “Cross-Border Fertility care—International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies Global Survey: 2006 Data and Estimates”. Fertility and Sterility 94: e4–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.049.

- Ormond, M., D Adamson, F Zegers-Hochschild, J de Mouzon, and International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies 2013. “En Route: Transport and Embodiment in International Medical Travel Journeys between Indonesia and Malaysia.” Mobilities 1–19. 10(2): 285-303.

- Pande, A. 2014. Wombs in Labor: Transnational Commercial Surrogacy in India. New York, NY: Columbia Univ. Press.

- Parry, B. 2008. “Entangled Exchange: Reconceptualising the Characterisation and Practice of Bodily Commodification.” Geoforum 39: 1133–1144. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.02.001.

- Parry, B. 2015. “May the Surrogate Speak?.” In Opendemocracy. Opendemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/beyondslavery/bronwn-parry/may-surrogate-speak

- Parry B, Greenhough B, Brown T, et al. 2015. Bodies across Borders: The Global Circulation of Body Parts, Medical Tourists and Professionals. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Pennings, G. 2005. “Reply: Reproductive Exile versus Reproductive Tourism.” Human Reproduction 20: 3571–3572. doi:10.1093/humrep/dei223.

- Perler, L., and C. Schurr. forthcoming. “Beyond Bioavailable Bodies into the Reproductive Biographies of Egg Providers.” In Body & Society.

- Pfeffer, N. 2011. “Eggs-Ploiting Women: A Critical Feminist Analysis of the Different Principles in Transplant and Fertility Tourism.” Reproductive BioMedicine Online 23: 634–641. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.08.005.

- Pratt, G. 2012. Families Apart: Migrant Mothers and the Conflicts of Labor and Love. Minneapolis, Minn: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rajan, K. S. 2006. Biocapital: The Constitution of Postgenomic Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

- Richter, M. 2015. “Can You Feel the Difference? Emotions as an Analytical Lens.” Geographica Helvetica 70: 141–148. doi:10.5194/gh-70-141-2015.

- Rudrappa, S. 2017. “Reproducing Dystopia: The Politics of Transnational Surrogacy in India, 2002–2015.” Critical Sociology: 0896920517740616.

- Rudrappa, S., and C. Collins. 2015. “Altruistic Agencies and Compassionate Consumers.” Gender & Society 29: 937–959. doi:10.1177/0891243215602922.

- Schurr, C. 2014. “Mütter zu verleihen: Erst Indien, dann Thailand und jetzt auch Mexiko: Warum das globalisierte Baby-Business boomt”. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 26 August, 2014, 2. doi:10.5167/uzh-102558.

- Schurr, C. 2017. “From Biopolitics to Bioeconomies: The ART of (Re-)Producing White Futures in Mexico’s Surrogacy Market.” Environment and Planning D 35: 241–262. doi:10.1177/0263775816638851.

- Schurr, C., and E. Militz. 2018. “The Affective Economy of Transnational Surrogacy.” In Environment and Planning A Online First, 1–20. Published April 16, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18769652

- Schurr, C., and L. Perler. 2015. “‘Trafficked’ into a Better Future? Why Mexico Needs to Regulate Its Surrogacy Industry (And Not Ban It).” Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/beyondslavery/carolin-schurr-laura-perler/trafficked-into-better-future-why-mexico-needs-to-regulate

- Schurr, C., and H. Walmsley. 2014. “Reproductive Tourism Booms on Mexico’s Mayan Riviera.” International Medical Travel Journal. May.

- Sheller, M. 2004. “Automotive Emotions: Feeling the Car.” Theory, Culture & Society 21: 221–242. doi:10.1177/0263276404046068.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A 38: 207–226. doi:10.1068/a37268.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2016. “Mobilizing the New Mobilities Paradigm.” Applied Mobilities 1: 10–25. doi:10.1080/23800127.2016.1151216.

- Shenfield F, Pennings G, De Mouzon J, AP Ferraretti, V Goossens, and ESHRE Task Force ‘Cross Border Reproductive Care’(CBRC). 2011. “ESHRE’s Good Practice Guide for Cross-Border Reproductive Care for Centers and Practitioners”. Human Reproduction 26: 1625–1627. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der090.

- Söderström O, Randeira S, Ruedin D, et al. 2013. Critical Mobilities. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Spinney, J. 2015. “Close Encounters? Mobile Methods, (Post)Phenomenology and Affect.” Cultural Geographies 22: 231–246. doi:10.1177/1474474014558988.

- Thompson, C. 2005. Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Urry, J. 2009. Mobilities and Social Theory. The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, 475–495. Malden, MA and Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Vlasenko, P. 2015. “Desirable Bodies/Precarious Laborers: Ukrainian Egg Donors in Context of Transnational Fertility.” In (In)Fertile Citizens: Anthropological and Legal Challenges of Assisted Reproduction Technologies, edited by V. Kantsa, G. Zanini, and L. Papadopoulou, 197–216. Aegean: In-Fercit.

- Whittaker, A. 2016. “From ‘Mung Ming’ to ‘Baby Gammy’: A Local History of Assisted Reproduction in Thailand.” Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online 2: 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.rbms.2016.05.005.

- Whittaker, A., and C. H. Leng. 2016. “‘Flexible Bio-Citizenship’ and International Medical Travel: Transnational Mobilities for Care in Asia.” International Sociology 31: 286–304. doi:10.1177/0268580916629623.