ABSTRACT

Nature-based tourism is a mobile activity shaped by the capacity of tourists for displacement and the socio-material infrastructure allowing flows. However, the literature has scarcely addressed aspects of mobility in governing nature-based tourism. Taking the case of the National Park Torres del Paine we explore three aspects of mobility in nature-based tourism using the concepts of routes, frictions, and rhythms. Our findings show that the movement of tourists challenges spatially bounded forms of governance. Instead, we argue, new mobility-sensitive forms of nature-based tourism governance are needed that can complement the use of fixed-boundary conservation enclosures.

Introduction

The expansion of protected areas around the world has gone hand-in-hand with the growth of nature-based tourism (Brandon Citation1996; West, Igoe, and Brockington Citation2006; Balmford et al. Citation2009). This is in part because nature-based tourism has been thought as a non-extractive activity that can be performed in ecologically relevant places without compromising their sustainability (Novelli and Scarth Citation2007). Tourism in protected areas has one of the highest growth rates within the international tourism industry (Balmford et al. Citation2009; Buckley Citation2009). It has also been promoted as a win-win solution to reconcile conservation and development goals by, for example, providing a central source of financing for the maintenance of protected areas (Walpole, Goodwin, and Ward Citation2001; Lamers et al. Citation2014). However, the increasing flow of tourists to ‘natural’ spaces also reveals a number of social and ecological impacts that demand closer examination (Cole and Landres Citation1996; Buckley Citation2004; Kuenzi and McNeely Citation2008; Barros, Pickering, and Guides Citation2015; Poudel and Nyaupane Citation2015). Underlying these impacts, we argue, are questions on the compatibility of spatially delimited protected ‘areas’ and the inherent mobile character of nature-based tourism activities.

Figure 4. Group of tourists trekking in the trail section Paine Grande – Italiano ranger station.

Source: CONAF.

Mainstream conservation continues to be closely aligned to the establishment of conservation enclosures (Adams, Hodge, and Sandbrook Citation2014). The creation of these enclosures involves a process of territorialisation, or enacting material demarcations that include or exclude people within particular geographic areas and that establish, in turn, forms of access to and use of nature-based resources (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995). Boundaries in a national park, for instance, spatially delimit the division between non-extractive (conservation) spatial claims made by the state with pre-existing or alternative extractive land-use activities. As argued by Balibar (Citation1998), in separating extractive and non-extractive uses of space, protected areas establish ‘natural places’ that can be visited and consumed by people through the practice of nature-based tourism (Rutherford Citation2011). These bounded places are then continually reproduced through both static and mobile practices related to nature-based tourism (Lund and Jóhannesson Citation2014).

While tourism is often conceptualised as a static phenomenon (Zillinger Citation2007), it is also fundamentally shaped by mobility (Verbeek Citation2009). In fact, nature-based tourism relies on the capability of tourists to move to and through protected areas, crossing external and internal boundaries. Accordingly, different types of routes, including trekking trails and roads, are created to facilitate the continuous displacement of tourists to parks and reserves. Similarly, the development of nature-based tourism demands the establishment and maintenance of socio-material infrastructure, which is essential for tourists to stop and rest. Routes and infrastructure are established both inside and outside the boundaries of protected areas, linking nature-based tourism to the development of nearby villages, towns and cities (see Villarroel Citation1996). Accordingly, managers of protected areas and decision-makers linked to conservation and tourism must take especial attention in governing tourists’ movement across protected areas boundaries. This requires turning conservation and tourism governance on aspects of mobility, which is particularly challenging considering the boundary-based forms of governance that have dominated nature conservation (see Phillips Citation2004).

The global expansion of social connections, information networks, and means of transportation, has enabled nature-based tourism to include once remote places around the world. Chilean Southern Patagonia is of these places, having continued to grow in popularity over the last two decades. The most visited place within Chilean Southern Patagonia is the National Park and Biosphere Reserve Torres del Paine. In a contest organized by the travel website VirtualTourist.com in 2013, Torres del Paine was voted as the 8th Wonder of the World out of more than 300 destinations from 50 countries. Torres del Paine has an area of 227,298 ha, representing five different ecosystems of the Patagonian Region (Pisano Citation1974; Domínguez Citation2012). It encompasses mountains, glaciers, rivers and lakes, and hosts a variety of endemic plants and animals (Vela-Ruiz Figueroa and Repetto-Giavelli Citation2017). The park has the highest density of pumas in Chile (Barrera et al. Citation2010), while the populations of guanaco (Lama guanicoe) and huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus) have grown steadily in recent years (CONAF Citation2009). The centrepiece of the Park is the Cordillera del Paine, and particularly, the rock formations of Torres del Paine and Cuernos del PaineFootnote1 ().

The desire to closely admire these rock formations has attracted an increasing number of tourists year by year. Annual visitor numbers have fluctuated from around 6,000 in the middle of the 1980s, to more than 250,000 in 2017 (CONAF Citation2018). Increasing tourism has threatened the conservation objectives of the park, with control over the mobility of tourists a major challenge for both public and private actors. This article explores these threats by examining how movements of nature-based tourism are governed in Torres del Paine. In particular, we analyse routes, frictions and rhythms to understand how the mobile character of nature-based tourism confronts the relatively static boundaries of the park, and illustrate the ways in which tourism mobilities challenge boundary-based or ‘territorial’ forms of conservation governance.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces our theoretical framework focused on the relationship between spatial claims, mobility and governance. Section 3 provides a description of the study’s methods. Section 4 and section 5 provide the findings. Section 4 presents the historical development of spatial claims and boundary formation regarding protected areas in Southern Patagonia, while section 5 presents the analysis of routes, frictions and rhythms of nature-based tourism in Torres del Paine. In section 6, we discuss the potential for mobility-sensitive-governance of nature-based tourism before turning to our main conclusions.

A flows and mobilities approach

Nature conservation is a fundamentally spatial practice exemplified by the formation of bounded ‘protected areas’ or ‘parks’ (Adams, Hodge, and Sandbrook Citation2014). Establishing protected areas corresponds to a process of territorialisation, through which spatial claims over what can and cannot be done in a given area are negotiated (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995). The definition of spatial boundaries through this process then enables specific actors to assert control over a geographic area, including flows of people, activities and nature itself (Sack Citation1986). Though the territorialisation of nature conservation requires keeping people and nature in place within defined spatial boundaries (Lowe Citation2003), protected areas can be also considered as fluid spaces shaped by the intersection of different types of socio-material mobilities (see Lund and Jóhannesson Citation2014; Bush and Mol Citation2015). By socio-material mobilities, we are not merely referring to the movement of people, materials, species and information in an already taken for granted physical space. Rather, by using the concept we also recognise the capacity of the movement and of the infrastructure that allows the flow of different entities, to transform social and material relations (see Bonelli and González Gálvez Citation2016).

From a flows and mobilities perspective, conservation and tourism practices cannot be conceptualised as fully contained within spatially fixed terrains. They are instead understood as being established, reaffirmed and changed through open-ended networks (Sheller and Urry Citation2006; Castells Citation2009; Sheller Citation2014). Although boundaries are relevant elements in the conformation of conservation spaces and in the practice of nature-based tourism, addressing conservation and tourism practices from the perspective of movement requires attention to the elements of mobility as well. These elements are fundamental to understand the ways in which mobility produces, and at the same time is produced by, socially mediated processes and practices. From Cresswell (Citation2010), we take three aspects of mobility that we consider relevant for the sociological study of nature-based tourism mobility in protected areas: routes, frictions, and rhythms.

First, routes operate as spaces of flows through which people, species, materials, and information move (Castells Citation2009). Identifying routes therefore makes movement an object of analysis, challenging ‘a-mobile’ social science research that commonly ignores or trivialises its relevance (Sheller and Urry Citation2006; Sheller Citation2014). Nature-based tourism as a social practice in particular relies on the operation of routes through which tourists, guides, park rangers and others move. Though social studies on tourism have mostly concentrated on destinations, recent tourism research has focused on routes that connect tourists’ origin and destinations, and on social relations that happen on the move (Verbeek Citation2009; van Bets, Lamers, and van Tatenhove Citation2017). Similarly, we concentrate on routes towards and inside nature-based tourism destinations, where tourists go mainly to practice trekking in mountain circuits.

Second, frictions cause mobilities to stop or slow down (Cresswell Citation2010). In a wider conception, frictions can be also understood as the encounter between mobility and place (Tsing Citation2004; Cresswell Citation2014, Citation2016). Although some approaches to networks, flows and globalization assume seemingly frictionless environments through which flows of people, materials and information move, many forms of friction are distributed unevenly in social space (Tsing Citation2004; Scott Citation2009). Borders and boundaries, for instance, impose friction on those who try to pass them. In the domain of protected areas and nature-based tourism, tourists experience both environmentally derived frictions (from bushes, rivers, lakes, cliffs, wind, slopes, etc.) and social derived frictions (from rules and checkpoints that control and channel tourist movement). Socio-material infrastructures including airports, accommodation and ground transportation also all condition the displacement of tourists.

Third, rhythms represent alternations between moments of movement and of rest (Cresswell Citation2010), or crescendos of activity and relative quietness (Seamon Citation1979). Henry Lefebvre highlights the relevance of rhythms as an analytical perspective to interpret social life. In the conception of Lefebvre, the existence of rhythm is immanent to time and space, and entails repetition, measure and difference (Lefebvre (Citation1992) 2004, 6). In the context of protected areas and nature-based tourism, patterns of tourists’ rhythms can be produced for several reasons. For instance, intervals of movement and rest could be steered according to the distance between campsites along a certain trekking circuit, but can also be generated spontaneously by tourists themselves by choosing their own time to sleep and walk. Based on the work of Lefebvre, Rantala and Valtonen (Citation2014) develop a ‘rhythmanalysis’ of nature-based tourism, defining ‘nature tourists, as walking and sleeping beings’ (20), who synchronise their body ‘to the rhythm of nature as a part of the flow of nature-based tourism activities’ (22).

The state has had a central role in the territorialisation of nature conservation, often through hierarchical and centralised modes of governance. Spatial boundaries are particularly central to hierarchical modes of governance, as they assert state ownership over conservation spaces, as well as delimit the enforcement of law and rules assosiated with nature conservation and tourism. However, nature-based tourism has driven changes in conservation governance, associated with the inclusion of new actors, rules, and power relations. These changes configure new governance arrangements, in which hierarchical modes have been transformed into more network-shaped modes of governance through which the territorial claims of state and private actors are negotiated (see Arnouts, van der Zouwen, and Arts Citation2012). As we go on to argue in the rest of this paper, networked forms of governance can provide a lens to reinterpret protected areas as internally constituted by flows and mobilities, and as such enable the possibility for new forms of nature-based tourism to emerge rather than being prescribed.

Methodology

We investigate nature conservation and nature-based tourism using case study methodology. Case study methodology enables the investigation of a specific phenomenon, while taking into account the context and processes involved in its generation (Meyer Citation2001). A particular case is not chosen because of its representativeness of certain social relations, processes, institutions or structures, but rather as a mean for abstracting social processes from the course of the events analysed (Mitchell Citation2006). Case study methodology enables the use of different methods for collecting disparate sources of data, and providing multiple lenses to observe and understand different facets of the phenomenon under investigation (Baxter and Jack Citation2008). We used three methods to develop our research, participant observation, interviews and secondary data analysis.

Two of the authors carried out fieldwork in Chilean Southern PatagoniaFootnote2 from September 2016 to January 2018. Participant observation and interviews were developed by both observing and participating in tourist movements (see Büscher and Urry Citation2009). Observation locations included Punta Arenas, Puerto Natales, Puerto Williams, and Torres del Paine, while displacements included the marine route between Puerto Montt to Puerto Natales in the ferryboat Evangelistas (during summer season where most of the passengers of the ferry are tourists going to Torres del Paine), as well as trail sections of mountain circuits inside the National Park Torres del Paine.

In Torres del Paine, the first author accompanied the interim superintendentFootnote3 of the park in his work activities during one week in peak season. Interviewing while participating in informants’ regular practices and activities has been an important strategy in this study (see also Anderson Citation2004; Evans and Jones Citation2011). Walking along with the interim superintendent enabled an understanding of the day-to-day practices, relations and conflicts produced by the development of nature-based tourism. During those guided transect walks (see Chambers Citation1994), the first author also engaged in spontaneous conversations with park rangers based in mountain refuges, managers of campsites and tourists. Data from these observations and conversations were recorded daily in a field notebook.

Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with public and private actors involved in the governance of Torres del Paine. Interviews were designed to obtain information on three key subjects regarding nature conservation and nature-based tourism: 1. The identification of relevant actors to the governance of Torres del Paine; 2. The identification and explanation of spatial claims and disputes over boundaries in and around the park; and 3. The description of mobile practices related to both conservation and nature-based tourism. The interviews were conducted in Spanish and varied in length between 40 minutes and two hours. Prior informed consent for conducting and audio recording was sought before all interviews. Five respondents gave permission to record interviews while two declined. Answers from the latter two respondents were recorded directly in the field notebook.

In addition, we carried out a comprehensive search and analysis of secondary sources, including scientific articles, theses, statistical records, technical reports, legal documents, newspaper articles, online information and news, photographs and maps. We focused on documents related to conservation and tourism in Patagonia and Torres del Paine. These secondary sources were not taken for granted as descriptions of reality ‘out there’; the analysis included obtaining an understanding of how documents were produced and circulated (Atkinson and Coffey Citation2004) and how they related to discourses on tourism and conservation in Patagonia.

Data were analysed using hermeneutic and collective hermeneutic methods (Molitor Citation2001; James et al. Citation2010). Data analysis started in parallel with data collection. Data were coded under the key concepts that support the theoretical approach of the study (i.e. spatial claims, routes, frictions and rhythms). Within each of these categories, further coding was developed based on key subjects used to structure the interviews listed above.

Spatial claims and boundary formation: the territorialisation of conservation and nature-based tourism in Chilean Southern Patagonia

The development of conservation and tourism in Chilean Southern Patagonia

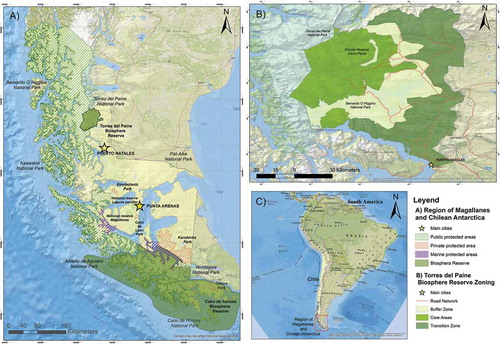

Spatial claims regarding nature conservation and tourism in Chilean Southern Patagonia began in the middle of the 20th century through the creation of national parks and reservesFootnote4. The creation of large protected areas was one of the strategies used by the Chilean State to control and set sovereignty over the Southern Patagonian territories. Using the Forestry Law of 1931, the Chilean State decreed the first national park in the region, the Cape Horn National Park (63,000 ha) in 1945, under the banner of virgin land (Ministerio de Tierras y Colonización Citation1945). During the second half of the century, the Chilean State continued with the creation of the National Park for Tourism Lago Grey (1959), the National Park Alberto de Agostini (1965), the National Reserve Alacalufes (1969)Footnote5, and the National Park Bernardo O’Higgins (1969). As a result, Chilean Southern Patagonia has been consolidated as a conservation region both at national and international scale. Nowadays, around 50%Footnote6 of the land in the Region of Magallanes and Chilean Antarctica – the southernmost administrative region of the country – is under some form of conservation (see ), and this process continues to expand through the conformation of state and private alliances.

Figure 2. Protected Areas in the Region of Magallanes and Chilean Antarctica. (a) Shows public and private protected areas in Southern Patagonia. (b) Shows the National Park Torres del Paine and the projected expansion of the Biosphere Reserve Site, including core (public protected areas), buffer and transition zones. (c) Shows Chilean Southern Patagonia in South America.

In 2018, the state increased protected areas by 9.27%, incorporating 1,356,993 ha to the National System of Wild Protected Areas (SNASPE), administrated by the National Forestry Corporation, CONAFFootnote7. This was the largest increase in protected areas since 1969, and the result of an agreement signed by the Chilean state and the Tompkins Conservation FoundationFootnote8. The agreement led to the creation of the Red de Parques de la Patagonia (Network of Parks of Patagonia), including the donation of 407,625 ha by the Tompkins family, and the inclusion of 949.368 ha of public lands to the SNASPEFootnote9.

As the state and private actors strive to delimitate and expand protected areas, a range of other activities (including mining, fishing, aquaculture and livestock farming) compete to access, use, and control resources and spaces in Patagonia (Frodeman Citation2008; Pollack, Berghöfer, and Berghöfer Citation2008). At the same time, as nature-based tourism has become a core activity in the development of Patagonia, various actors involved in these sectors have turned to develop tourist facilities and experiences connected to protected areas. Roughly, 20% of the tourists that visited the areas of the SNASPE in 2017 were concentrated in the territory of Patagonia, which encompasses 23 protected areas. In turn, 82% of those tourists could be found in just one of these areas, the National Park Torres del Paine, in the province of Última Esperanza (CONAF Corporación Nacional Forestal Citation2018).

The National Park and Biosphere Reserve Torres del Paine

Sheep farming was the central development project promoted by the state as well as by national and foreign settlers in both Argentinian and Chilean Patagonia in the 19th and 20th centuries (Martinic Citation2002; Coronato Citation2010). In 1915, the largest livestock company in the area was the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego (SETF), which controlled more than 3,000,000 ha, mainly in Chilean territory. In the Province of Última Esperanza alone, the SETF came to control more than 450,000 ha. While most lands were bought in public auctions, the company also annexed publically titled land de facto (Martinic Citation2011). Thus, the potential occupation of public property by private farmers – who perceived these terrains as freely available – was a main concern for the state around the first half of the 20th century. In order to set effective control over these territories, the Department of Conservation and Administration of Agricultural and Forestry Resources of the Ministry of Agriculture decided to create the National Park for Tourism Lago Grey in 1959. The Lago Grey Park started out with an area of around 4,332 ha, but was expanded shortly after, in 1962, to more than 20,200 ha, mainly to include the terrains of the rock formation called Torres del Paine: ‘a set of scenic beauty of exceptional tourist value’ (Ministerio de Agricultura de Chile Citation1962). From that time onwards the park became officially the National Park Torres del Paine.

Although the creation and demarcation of conservation enclosures were meant to exert sovereignty and control over spaces in Southern Patagonia, cattle farming continued to dispute these expansions. In 1964, Juan Radic, a cattle farmer, acquired the Estancia Cerro Paine (4,400 ha), located on the southeast slope of the rock formation Torres del Paine. Although at that time the National Park Torres del Paine had been recently created, the area of the park continued to expand towards the neighbouring lands until 1979, when the current boundaries were established. The continuous expansions ended up surrounding the Estancia Cerro Paine. Fearing that the state would expropriate his property, in 1979 Radic decided to sell Estancia Cerro Paine to Antonio Kusanovic, son of Croatian immigrants, who was an experienced rancher in Patagonia. A year before, in 1978, UNESCO declared the National Park Torres del Paine as a Biosphere Reserve Site at the request of the Chilean state (see about Biosphere Reserve Sites here http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/). The recognition granted by UNESCO promoted Torres del Paine’s international visibility for both tourism and scientific research.

Although Kusanovic and his family bought Estancia Cerro Paine to continue with livestock business, the growing tourist numbers visiting the park increasingly approached Estancia Cerro Paine asking for food, water, accommodation or a place to camp, which made Kusanovic family realise the potential economic benefits that nature-based tourism could bring them. The family started to explore nature-based tourism as alternative livelihood by setting up a camping zone, while they continued to be dedicated mainly to livestock ranching. In 1992 they opened the Hostería Las Torres, and in 1997 the family created Fantástico Sur, a tourist company that currently owns one hotel, four lodges, cottages and domes, as well as five camping areas that comprise 450 camping places. In 2012, the Kusanovic family ceased livestock activities to turn completely to tourist business. Recently, they made a further shift to conservation, when in 2017 the Estancia Cerro Paine became the Reserva Cerro Paine, a private protected areaFootnote10. This shift to conservation happened when the relation between CONAF and Kusanovic family were in a conflicting stage because CONAF decided to present a lawsuit against Fantástico Sur for the illegal occupation of 157 ha of public property in the sector of Francés Valley. The disputed space is located at the heart of the mountain circuits, where this tourist company owns different facilities for tourist accommodation. Nevertheless, as we explain in the next section, recent boundary disputes mask a more central challenge related to controlling the flow of tourists in the mountain circuits of the park.

Nature-based tourism mobility in Torres del Paine

Routes

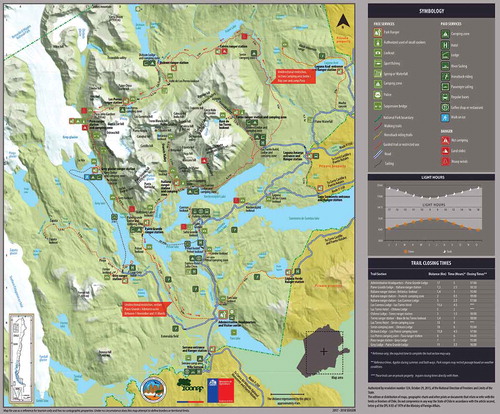

The boundary conflict between CONAF and Fantástico Sur reflects broader disputes related to the growth of nature-based tourism in the park. However, these disputes are not only about the spatial limits between public and private conservation enclosures, but also about how to gain control over key routes – or sections of these routes – that are strategic for the displacement of tourists, and that cross public and private property. As the main activity in Torres del Paine is mountain trekking, the most prominent routes correspond to several trekking trails that surround the rock formations Torres del Paine, Cuernos del Paine and Paine Grande Hill, which are in the centre of the park (see ). There are fifteen trails enabled for trekking, which are in turn grouped in two main circuits named by their shapes as the ‘W’ and the ‘O’ (also known as Macizo Paine). Trekking trails that conform these circuits are delimitated and at the same time connected by resting places, i.e. camping zones, lodges, cottages and domes that allow tourists to stop and rest while traveling in the circuits. The W and O circuits thereby form a network that enables the displacement of mainly tourists, but also park rangers, guides, porters and scientists moving through this network.

Figure 3. National Park Torres del Paine. The dark green strip that is observed towards the East and South of the rock formations bordering the Nordernskjöld Lake correspond to the Reserva Cerro Paine.

Source: CONAF.

The layout of the trekking circuits challenges boundary configuration in the park. CONAF formally manages the park for conservation purposes within the spatial limits that have been drawn over time. However, as nature-based tourism has become increasingly relevant in terms of volume, impacts, and benefits, spatial limits are no longer central factors to set the scope and traits of governance. The W and O circuits are intersected by public (the park) and private (the Reserva Cerro Paine) property. Furthermore, CONAF started a policy of concessions years ago, as its institutional capacities could not deal with the influx of tourists, leasing out four concessions in the west, northwest, and southwest sections of the park to the company Vértice, who currently use this land to run three camping zones and three lodges. Yet CONAF still controls three free public camping zones, located strategically in the three valleys that compose the W circuit. Besides ownership considerations, it is in the mutual interest for CONAF, Fantástico Sur and Vértice to govern tourists’ movement along the circuits rather than within property boundaries.

In order to steer the movement of visitors, CONAF has eight mountain refuges distributed along the W and the O circuits they use to base groups of park rangers working in a system of shifts. The number of park rangers varies considerably from winter to the peak tourism summer season. There is no regular distance between each of these refuges and the uneven spatial distribution of topographical conditions, such as altitude changes, slope, and sinuosity of the trails (as well as particular spatial and temporal weather conditions that normally include rain and strong winds) make the use of these trails variable in terms of velocity and experience. CONAF has established unidirectional movement in the north section of O circuit, from Serón Camping Zone to Paso Ranger Station, in order to better control the flow of tourists in this less accessible area of the park, where CONAF does not control resting places (see ). CONAF has also established a special schedule including different closing times for different trails sections, taking into consideration their length and the average time it takes tourists to walk them.

Nevertheless, these and other measures have not prevented tourists to perform their own shortcuts and routes that avoid the control of CONAF. In some of the most winding trails sections, tourists have cut corners creating shortcuts that reduce the length of the trails. The frequency and volume of tourists have led that some of these shortcuts have been incorporated as new connecting routes in the circuits, disturbing the original design, which was made considering a minimum impact on soil degradation and fauna dynamics. Similarly, the massive congregation of tourists in specific places, such as at the Salto Grande Lookout, at the Nordernskjöld Lake, has led tourists to find new lookouts in contiguous sites and consequently create new paths to reach them. Furthermore, mountain guides and park rangers have discovered hidden camping sites, which apparently have been used systematically by groups of tourists, who in an organized way have shared their location to avoid paying at private and given-in-concession resting places of the W circuit. As a guide who participated in cleaning the park after summer season explained:

[some visitors of the same nationality] shared information about different informal campsites established along the W where they didn’t have to pay to stay overnight. We discovered these places, because one of them forgot his map […] I was in three of these campsites, and we realised at that time that the places were in use.

Overwhelmed by not being able to face the increasing flow of tourists on the W circuit, in 2016 CONAF planned to lease out the three last camping zones under its control. However, the initiative gained the opposition of the Association of Local Guides of Puerto Natales, the Association of Tourist Operators and Tourist Agencies of Torres del Paine, and other local organizations and workers of Torres del Paine, who conformed the Comité de Defensa Torres del Paine (Committee for the Defence of Torres del Paine). This process was explained by one of the members of the board of the Association of Local Guides of Puerto Natales as follows:

The Committee for the Defence of Torres del Paine arose because [CONAF] wanted to grant concessions for the last public camping areas, so no place would be left for free. The prices are high in Torres del Paine, and it is supposed that the management plan of the park states that there should be a benefit for local community. This was the only benefit that was going to be lost.

The local opposition to the concessions – as a form of virtual privatization – of the public camping zones stopped the initiative, although later, the collapse of the sanitary services both in public and in private camping zones triggered the creation of a system of reservations oriented to control the number of tourists along the W and O circuits. The implications of this reservation system will be discussed in the following section.

Frictions

The making of mountain circuits by CONAF, private agents and tourists, has been a process oriented to overcome frictions that stop or slow down the mobility of climbers, trekkers and day-trippers. The bridge to access the Italiano camping zone, and the three 20+ meter high suspension bridges that cross the ravines between the Grey and Paso Ranger Stations, are clear evidence of this. In fact, Paso Ranger Station owes its name to the opening of a pass in the Olguín Mountain Range in 1976, by John Garner, an English climber, and Óscar Guineo, one of the five park rangers at that time. This pass enabled the circumnavigation of the Paine Grande Massif, thereby configuring the O circuit. This landmark was later known as the Paso John Gardner (with ‘d’ because of a misspelling), and is nowadays the highest point of the O circuit at 1,200 m above sea level (see ). Since the opening of the Paso John Gardner, the volume of tourists has changed dramatically. John Garner claims to have seen one single tourist in three months in early 1976, while 264,800 tourists visited the park in 2017 (CONAF Citation2018). The rapid increase in the number of tourists in recent years has led to the imposition of friction through rules.

In the summer of 2016–2017 CONAF began to implement a system to regulate the entrance of tourists on the mountain circuits. The design and application of this system was triggered by the collapse of sanitary services, both in public and concessional camping zones, mentioned before, which brought land and water pollution, as well as health problems to some tourists. However, its implementation was the consequence of accumulative impacts caused by massive tourism in the park, including three huge forest fires provoked by tourists that devastated around 47,000 ha in the last 30 years (Vidal Citation2012). Specifically, what was put into practice was an online system of reservation, through which anyone who wants to trek on the mountain circuits should register previously. For doing this, tourists should consider that trekking in mountain circuits entails spending several nights in different resting places, including those managed by CONAF, Vértice and Fantástico Sur. As a result, tourists had to arrange their accommodation with different operators and estimate a particular pace on the trails of the mountain circuits.

The lack of an integrated accommodation reservation system created confusion among tourists, guides and tourist operators. Tourists had to book their accommodation on three different online platforms intending to organize their trekking trips considering the available spots in camping zones or lodges. Many tourists complained about the lack of organization between the three main controllers of the mountain circuits. Particularly, local tourist operators claimed that the park, being a public space, is administrated by a duopoly controlled by Fantástico Sur and Vértice, which has negatively affected local tourist agencies, operators and guides, and which has affected Torres del Paine as tourist destination as a whole.

While it contributed to reducing the number of tourists on the mountain circuits, the reservation system also created new issues related to the distribution of tourists in the park. Without having a reservation for resting places on the mountain circuits, tourists could still buy a ticket to visit the park, being valid for three consecutive days. Tourists without reservation for accommodation on the mountain circuits started to concentrate during the day on some of the trails of the W circuits. This concentration of tourists affected the most the route to the most iconic spot of the park, the Base de las Torres lookout, which offers visitors a postcard view of the Torres del Paine rock formation. In the words of a local guide:

Apparently [the new system of reservation] is working well, because there is no congestion, I mean it is okay, [the flow of tourists] is normal in the Francés Valley and in Grey [Lake sector]. However, Base de las Torres is a mess. All the people who did not get a reservation go to Base de las Torres for the day.

The starting point of this trail is located in the Reserva Cerro Paine, so to trek this path tourists can bed at the hotel, lodges or camping zones managed by Fantástico Sur, or even come for the day from Puerto Natales or Punta Arenas.

The implementation of the system of reservation, however, did not avoid some tourists trekking on mountain circuits without booking in advance. As the starting point for the mountain circuits is in Las Torres camping zone, in Reserva Cerro Paine, CONAF started to check whether the trekkers had their reservations at that point. Although Reserva Cerro Paine accounts for its own private rangers, which control the displacement of tourists in the 4,400 ha of the reserve, rangers of CONAF are allowed to come in the private reserve to carry out monitoring and control tasks. However, in practice, it has been difficult to prevent tourists without reservation in resting places from having access to mountain circuits and remain there overnight. For example, in Reserva Cerro Paine, the lead author observed:

Two backpackers being asked by CONAF rangers about their reservations to access to mountain circuits. They said they did not have reservation because they were only going for the day to Base de Las Torres, although their big backpacks indicated that the trip would last several days. The rangers asked then them to leave their backpacks in a secure location in Fantástico Sur, but they replied they did not have money for doing so and preferred to keep their backpacks with them. (Field notes, Torres del Paine, 12 February 2017)

Due to the extension of the park and the reduce number of rangers, it is not possible for CONAF to exert an effective control of tourists on the trail sections of mountain circuits. Furthermore, once in the resting places, rangers cannot drive out tourists outside the park due to the risk of traveling on the trails without daylight. In this sense, the topographic and climatic conditions present in the park, impose their own frictions for the displacement of people.

Rhythms

In order to manage the flow of tourists on trails and in resting places, CONAF decided that tourists could stay only one night in each of the public camping zones under its administration. Since visitors can book accommodation for more than one night in the private and concessional camping zones and lodges, the restriction of one night implemented by CONAF therefore configured particular rhythms of displacement in traveling around the circuits. The relevance of and demand for public camping zones does not only build on the fact that these are free of charge, but also that they are spatially distributed along the circuits. In fact, the distance and topology of the trail make it necessary for tourists to stop in specific resting places. This is the case for the Paso camping zone (CONAF), which is located around six hours walking from Los Perros camping zone (Vértice), and five hours from Grey lodge and camping zone (Vértice) (see ).

Thus, to cope with restrictions imposed by the system of reservation, tourists should plan their routes, their resting places and their time allocated for movement and for repose. Patterns of rhythms in mountain circuits entail specific social practices and routines in different times of the day. In resting places, dawn is time to break camp and start a new day by trekking in the next trails section, while sunset is the time to set up camp again and get some rest after trekking. On trails, by comparison, trekking occurs during daylight presenting a variety of paces to ().

Besides the rhythm of tourism on the mountain circuits, restrictions imposed by the system of reservation created rhythm patterns that transcend the boundaries of the park. As mentioned above, tourists without reservations began to concentrate on specific trails in the park, while being accommodated outside the park in the city of Puerto Natales mainly. As the ticket for the park can be used for three consecutive days, a considerable number of tourists started to do daily visits into the park, going back and forth from Puerto Natales to Torres del Paine. The effects of this changing rhythm on tourists’ mobility have been particularly visible at the Laguna Amarga entrance, generating further congestion of motorised tourist transport, sanitary issues, as well as management problems for CONAF. Neither CONAF, Vértice, nor Fantástico Sur foresaw these rhythmic ‘side effects’ of the implementation of such a system of reservation.

A recent strategy of Fantástico Sur and Vértice has been to promote tourism in the park during wintertime. This is intended to distribute the number of tourists during the year, instead concentrating around 85% of the total number of visitors from October to April. This more proportional distribution of tourists during summer and winter seasons is also a goal shared by the National Service of Tourism (SERNATUR) at region scale, and the tourist department of the municipality of Puerto Natales. It could contribute to decongest the summer season, enabling a better management of the resting places and giving the tourist the possibility of having a better experience within the park. However, CONAF reduces the number of park rangers considerably during winter, which complicates the regulation and control of the activities taking place within the park. For that reason, some of the mountain circuits are closed during winter, thereby limiting the mobility of tourists, while driving rhythms of daily trekking activities and returning to the same resting place.

The same patterns are also reproduced by different alternatives of full-day trips to the park, or personalised and flexible alternatives of daily trips promoted by luxury hotels and lodges located close to the park. The growth of those rhythms that involve a single full day or more than one day getting in and getting out of the park, lead to an increase of motorised displacement to and inside the park. Motorised tourism then generates its own rhythms along the road, with a proliferation of informal guides conducting groups of tourists. As recorded by the lead author:

On the way back from Laguna Amarga [to Serrano Ranger Station], CONAF rangers were complaining that tourist vans often park to take photos in places along roads were stopping is prohibited, when we suddenly found a seemingly tourist van parked and a group of tourists taking photos in one of those places. We stopped the car and one of the rangers asked who the guide was. One woman said that there was no guide because they were just a group of friends, leaving the rangers with little scope for regulation. (Field notes, Torres del Paine, 13 February 2017)

While measures have been taken in order to reduce the number of tourists in mountain circuits, tourism to Torres del Paine is still promoted through the creation of travel connections. In 2016, a new airport was established in Puerto Natales, creating a direct connection with the city of Santiago, which is the central point of arrival of international tourists to the country. This poses a new challenge for the governance of nature-based tourism. On the one hand, as we have shown, increasing tourism defied the management of activities in the park, which is led by CONAF but also involves the participation of private actor. The latest set of measures taken by these actors have tended to control the entry of tourists to the park, and, at the same time, organize the displacement of tourists within the park boundaries. On the other hand, and contradictory to this new set of measures, national, regional and local authorities have continued to foster the arrival of tourists to Torres del Paine and in doing so increasing the visiting pressure of the park. Conflicting interests and relations between different groups around the access and use of Torres del Paine are central to ongoing debates and practices over the park’s governance.

Governing flows in relation to bounded space

The case of Torres del Paine shows how routes, frictions and rhythms as aspects of nature-based tourism mobility, challenge territorial forms of conservation governance. Routes, in the form of trekking trails on the mountain circuits, transcend park boundaries and in doing so implicate public and private actors in steering the mobility and immobility of tourists around the Cordillera del Paine. Moreover, routes are not merely connections between fixed places, such as trekking trails connecting resting places. Routes also emerge as places in themselves and trekking becomes the way of experiencing and enacting the park as a tourist destination (Lund and Jóhannesson Citation2014). Thus, nature-based tourism’ mobility defies the logic of ‘spatial fixation of people, places, and borders, which has been predominant in conservation’ governance (Pauwelussen Citation2015, 332), turning the focus of governance on keeping tourists moving through routes. Seen as such, the velocity, direction and experience of tourists become equally, if not more important than spatial boundaries to the governance of conservation areas.

Similarly, we have highlighted the importance of frictions and rhythms that reconfigure the movement of tourists within and across spatial boundaries. For instance, the reservation system for staying overnight in the park has implications for the dynamics of movement both within the park and outside its boundaries, which were not foreseen by CONAF and other actors involved in the park governance. This system reorganizes the rhythms of tourists who cannot get reservations, and in doing so creates concentrations of day visitors on specific trail sections within the park. In response, rhythms beyond the boundaries of the park are also reorganised, with changing volumes and frequencies of tourist movements from Puerto Natales or Punta Arenas to Torres del Paine. Moreover, frictions imposed on tourists’ mobility are generating flows of visitors to other protected areas in the region of Patagonia where local actors are less organised, and therefore less able to deal with increasing flows of tourists. This in turn could also jeopardise efforts beyond major tourism sites to promote nature conservation.

Our case study shows how nature-based tourism mobility is implicated in the production of a tourist destination like Torres del Paine. Though the movement of tourists is shaped by the existence of different routes, imposed frictions and rhythms, it is at the same time the flow of tourists which shapes those routes, frictions and rhythms in a particular way. As mentioned above, mobilities have the capacity to affect social and material relations. Just as Bonelli and González Gálvez (Citation2016) demonstrate, the construction of routes (roads in their case) can trigger profound socio-material transformations. As they argue, routes should not be considered an inert infrastructure in a landscape, but instead an entity that can modify wider socio-material relations. Our results build on their argument by showing that mobilities associated with nature-based tourism can drive material transformations through establishing routes, overcoming frictions and producing rhythms in and around protected areas. Furthermore, we show how such material transformations in turn shape the social relations between park managers, tourists, mountain guides and land owners that constitute the governance of nature-based tourism and conservation.

The results therefore indicate that the governance of mobilities, rather than the governance of spatial boundaries, requires engagement with the fluidity and socio-material nature of tourists in addition to their capacity to cross boundaries (see also Boas et al. Citation2018). In the case of nature-based tourism in Torres del Paine, this is demonstrated by tourists creating their own routes and rhythms, while overcoming imposed frictions, escaping from planned governance and channelling. Examples include the establishment of hidden camping sites along the mountain circuits, the growth of full-day trips on buses or private cars generating its own stopping places, and the ways tourists have found to escape from the restrictions imposed by the system of reservation. As argued by Büscher and Urry (Citation2009), it is therefore important to reconceptualise mobile tourists as producers of rules as much as they are subjects of governors alone. Furthermore, the results therefore demonstrate that mobility-sensitive conservation governance is not only a deliberate attempt of certain actors to channel and control the movement of other actors, but the immanent power of mobilities to influence self-organization among actors involved in a movement phenomenon (Bærenholdt Citation2013, 26).

Considering this, our findings also demonstrate how routes, frictions and rhythms reconfigure power relations among actors involved in the governance of Torres del Paine. As nature-based tourism has gained more centrality in the functioning of the park, so too have private actors that control spaces and infrastructure associated to its development. We have shown how, by controlling routes and resting places, powerful private actors, such as Fantástico Sur and Vértice, govern access to and movement in mountain circuits, raising claims from other less powerful actors, such as local guides, tourist operators and porters, who are concerned about what they consider the existence of a duopoly managing the park. Nevertheless, the latter, who participate actively in producing patterns of mobility within and in connection with the park, have also formed alliances to stop the granting of additional concessions, which in turn weakens the role of CONAF in controlling the park.

These findings hold broader relevance for orienting the territorial expansion of conservation in Chilean Southern Patagonia and beyond, towards forms of governance that are more sensitive to tourist mobility. This is particularly relevant in the ongoing expansion of the boundaries of Torres del Paine in response to mandatory requirements set by UNESCO for Biosphere Reserve Sites (see Gamonal Citation2014 and ), as well as for the enlargement and establishment of new protected areas in the framework of the Red de Parques de la Patagonia. Both of these expansions entail the creation of new spatial boundaries to define and demarcate nature to be conserved. However, we advocate for a more integrative view of tourism and conservation that encompasses both boundaries and mobilities interacting in conservation spaces.

Conclusion

This article has presented a sociological analysis of nature-based tourism and conservation governance using a theoretical framework that highlights the importance of the interactions between boundaries and mobility. By integrating spatial claims, routes, frictions and rhythms, we have analysed how the intrinsically mobile character of nature-based tourism challenges existing territorial forms of conservation governance in the National Park Torres del Paine, in Chilean Southern Patagonia. But we have also demonstrated how conservation and nature-based tourism can be made more sensitive to the routes, frictions and rhythms generated by the movement of tourists and park’s workers. Using this more nuanced mobility-sensitive perspective enables a means of reconceptualising the governance of nature-based tourism and conservation in a way that goes beyond the spatial boundaries that delimitate protected areas. Incorporating mobility-sensitive governance can be useful to address the challenges presented by the expansion of protected areas in Chilean Patagonia, particularly in orienting the zoning of Torres del Paine as a Biosphere Reserve Site. But it can also enable a starting point for a far wider transition to alternative approaches to boundary-based territorial modes of control so commonly used in nature conservation governance. To further explore this alternative we advocate for the integration of a broad range of human and non-human mobilities in future social science research of nature-based tourism and nature conservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support of Chilean National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (CONICYT), through its Programs FONDAP, Project N°15150003, and Becas Chile. The authors also thank the two anonymous referees that reviewed the article for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This astonishing landscape fascinated Lady Florence Dixie, an English aristocrat who travelled to Patagonia in 1879. She is considered the first tourist to visit the land were today is located the National Park Torres del Paine, and her field trip notes, helped her to write the book Across Patagonia (Dixie Citation1880).

2. Administratively, Patagonia includes the Province of Palena, the Region of Aysén and Region of Magallanes and Chilean Antarctica. We refer to the latter as Chilean Southern Patagonia.

3. Torres del Paine is the only protected area in Chile that accounts the position of superintendent, which was created in order to address the complexities derived from the development of an increasing nature-based tourism in the park. The first superintendent started in 2012 after the third big tourist-related forest fire that consumed 17,600 ha in the Grey Lake sector, during the summer of 2011–2012.

4. Notwithstanding, it is important to highlight the role of the private sector in promoting nature-based tourism in Patagonia, especially in the territories where today is Torres del Paine, in the first decades of the 20th Century (see CitationFerrer 2009).

5. In 2018, the National Reserve Alacalufes was upgraded to a National Park, changing its name to National Park Kawésqar. National parks are the most restrictive type of protected areas contemplated in the Chilean law.

6. This was calculated using data of the terrestrial area of the region, as well as of the area of private and public protected areas on land only.

7. CONAF’s main task is to manage Chile’s forestry policy and promote the development of the forestry sector. Current changes in the Chilean environmental policy, such as the creation of the Service of Biodiversity and Protected Areas under the Ministry of Environment, condition the role of CONAF in the administration of national protected areas. See https://www.amchamchile.cl/en/2011/06/protegiendo-la-biodiversidad-de-chile/for further discussion on this issue.

8. Douglas Tompkins was a conservationist that engaged in a controversy with the Chilean State regarding the establishment of private protected areas during the 1990s (see Nelson and Geisse Citation2001; Humes Citation2009).

9. For details see http://www.conservacionpatagonica.org/home.htm#modal.

10. Reserva Cerro Paine is part of Así Conserva Chile, a national organization integrated by around 100 private protected areas’ owners, who together own more than 600,000 ha alongside Chile (see http://asiconservachile.cl/acch/).

References

- Adams, W., I. D. Hodge, and L. Sandbrook. 2014. “New Spaces for Nature: The Re-Territorialisation of Biodiversity Conservation under Neoliberalism in the UK.” Transactions 39 (4): 574–588. doi:10.1111/tran.12050.

- Anderson, J. 2004. “Talking Whilst Walking: A Geographical Archaeology of Knowledge.” Area 36 (3): 254–261. doi:10.1111/area.2004.36.issue-3.

- Arnouts, R., M. van der Zouwen, and B. Arts. 2012. “Analysing Governance Modes and Shifts - Governance Arrangements in Dutch Nature Policy.” Forest Policy and Economics 16: 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2011.04.001.

- Atkinson, P., and A. Coffey. 2004. “Analysing Documentary Realities.” In Qualitative Research. Theory, Method, and Practice, edited by D. Silverman, 56–75. London: Sage Publications.

- Bærenholdt, J. 2013. “Governmobility: The Powers of Mobility.” Mobilities 8 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.747754.

- Balibar, E. 1998. “The Borders of Europe.” In Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling beyond the Nation, edited by P. Cheah and B. Robbins, 216–232. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Balmford, A., J. Beresford, J. Green, R. Naidoo, M. Walpole, and A. Manica. 2009. “A Global Perspective on Trends in Nature-Based Tourism.” PLoS Biology 7 (6): e1000144. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144.

- Barrera, K., N. Soto, J. Cabello, and D. Antúnez. 2010. El Puma: Antecedentes para su Conservación y Manejo en Magallanes. Punta Arenas: SAG.

- Barros, A., C. Pickering, and O. Guides. 2015. “Desktop Analysis of Potential Impacts of Visitor Use: A Case Study for the Highest Park in the Southern Hemisphere.” Journal of Environmental Management 150: 179–195. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.11.004.

- Baxter, P., and S. Jack. 2008. “Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers.” The Qualitative Report 13 (4): 544–559.

- Boas, I., S. Kloppenburg, J. van Leeuwen, and M. Lamers. 2018. “Environmental Mobilities: An Alternative Lens to Global Environmental Governance.” Global Environmental Politics 18 (4): 107–126. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00482.

- Bonelli, C., and M. González Gálvez. 2016. “¿Qué Hace un Camino? Alteraciones Infraestructurales en el Sur de Chile.” Revista de Antropología 59 (3): 18–48. doi:10.11606/2179-0892.ra.2016.124804.

- Brandon, K. 1996. “Ecoturism and Conservation: A Review of Key Issues”. Paper N.O. 033, Environmental Department Papers, Biodiversity Series, World Bank.

- Buckley, R. C., ed. 2004. Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publ.

- Buckley, R. C. 2009. Ecotourism: Principles and Practices. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publ.

- Büscher, M., and J. Urry. 2009. “Mobile Methods and the Empirical.” European Journal of Social Theory 12 (1): 99. doi:10.1177/1368431008099642.

- Bush, S., and A. Mol. 2015. “Governing in a Placeless Environment: Sustainability and Fish Aggregating Devices.” Environmental Science and Policy 53: 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.07.016.

- Castells, M. 2009. Communication Power. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chambers, R. 1994. “The Origins and Practice of Participatory Rural Appraisal.” World Development 22 (7): 953–969. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)90141-4.

- Cole, D. N., and P. B. Landres. 1996. “Threats to Wilderness Ecosystems: Impacts and Research Needs.” Ecological Applications 6: 168–184. doi:10.2307/2269562.

- CONAF (Corporación Nacional Forestal). 2009. Censo de Huemul en el Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, Puerto Natales, Magallanes. Puerto Natales: CONAF.

- CONAF (Corporación Nacional Forestal). 2018. Estadística Visitantes Unidad SNASPE para el Año 2017. Santiago: CONAF.

- Coronato, F. 2010. “El Rol de la Gandería Ovina en la Construcción del Territorio de la Patagonia”. PhD diss., Institut des Sciences et Industries du Vivant et de l’Environnement (Agro Paris Tech).

- Cresswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 17–31. doi:10.1068/d11407.

- Cresswell, T. 2014. “Friction.” In The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities, edited by Adey P., D. Bissell, K. Hannam, P. Merriman, and M. Sheller, 107–115. London: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T. 2016. “Afterword - Asian Mobilities/Asian Frictions?” Environment and Planning A 48 (6): 1082–1086. doi:10.1177/0308518X16647143.

- Dixie, F. 1880. Across Patagonia. London: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Domínguez, E. 2012. Flora Nativa de Torres del Paine. Santiago: Editorial Ocho Libros.

- Evans, J., and P. Jones. 2011. “The Walking Interview: Methodology, Mobility and Place.” Applied Geography 31: 849–858. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

- Ferrer, D. 2009. “Geographical Knowledge of Inner Patagonia and the Configuration of Torres Del Paine as a Natural Heritage to Be Preserved.” Estudios Geográficos 70266: 125–154. doi:10.3989/estgeogr.0456.

- Frodeman, R. 2008. “Philosophy Unbound: Environmental Ethics at the End of the Earth.” Environmental Ethics 30: 313–324. doi:10.5840/enviroethics200830335.

- Gamonal, E. 2014. El Papel de la Participación en la Ampliación de la Reserva de la Biosfera Torres del Paine. Antecedentes, Situación Actual y Propuesta de Modelo Participativo. Fundación Universitaria Fernando González Bernáldez. Madrid: Master Espacios Naturales Protegidos.

- Humes, E. 2009. Eco Barons: The Dreamers, Schemers, and Millionaires Who are Saving Our Planet. New York: Harper Collins.

- James, I., B. Andershed, B. Gustavsson, and B.-M. Ternestedt. 2010. “Emotional Knowing in Nursing Practice: In the Encounter between Life and Death.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 5 (2): 5367. doi:10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5367.

- Kuenzi, C., and J. McNeely. 2008. “Nature-Based Tourism.” In Global Risk Governance, edited by, O. Renn and K. D. Walker. Dordrecht: International Risk Governance Council Bookseries. 1 Vol. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6799-0_8.

- Lamers, M., R. Nthiga, R. van der Duim, and J. van Wijk. 2014. “Tourism–Conservation Enterprises as a Land-Use Strategy in Kenya.” Tourism Geographies 16 (3): 474–489. doi:10.1080/14616688.2013.806583.

- Lefebvre, H. (1992) 2004. Rhythmanalysis. Space, Time, and Everyday Life. London: Continuum.

- Lowe, C. 2003. “The Magic of Place; Sama at Sea and on Land in Sulawesi, Indonesia.” Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 159 (1): 109–133. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003753.

- Lund, K. A., and G. T. Jóhannesson. 2014. “Moving Places: Multiple Temporalities of a Peripheral Tourism Destination.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 14 (4): 441–459. doi:10.1080/15022250.2014.967996.

- Martinic, M. 2002. “La Participación de Capitales Británicos en el desarrollo Económico del Territorio de Magallanes (1880–1920).” Historia 35: 299–321. doi:10.4067/S0717-71942002003500011.

- Martinic, M. 2011. “Recordando a un Imperio Pastoril: La Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego (1893–1973).” Magallania 39 (1): 5–32. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442011000100001.

- Meyer, C. 2001. “A Case in case Study Methodology.” Field Methods 13 (4): 329–352. doi:10.1177/1525822X0101300402.

- Ministerio de Agricultura de Chile. 1962. Decreto 1050. Santiago: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile.

- Ministerio de Tierras y Colonización. 1945. Decreto 995. Santiago: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile.

- Mitchell, J. C. 2006. “Case and Situation Analysis.” In The Manchester School. Practice and Ethnographic Praxis in Anthropology, edited by T. M. S. Evens and D. Handelman, 23–43 New York: Berghahn Books.

- Molitor, M. 2001. “Sobre la Hermenéutica Colectiva.” Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales 5: 3–14. doi:10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.

- Nelson, M., and G. Geisse. 2001. “Las Lecciones del Caso Tompkins para la Política Ambiental y la Inversión Extranjera en Chile.” Ambiente Y Desarrollo 17 (3): 14–26.

- Novelli, M., and A. Scarth. 2007. “Tourism in Protected Areas: Integrating Conservation and Community Development in Liwonde National Park (Malawi).” Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development 4 (1): 47–73. doi:10.1080/14790530701289697.

- Pauwelussen, A. P. 2015. “The Moves of a Bajau Middlewoman: Understanding the Disparity between Trade Networks and Marine Conservation.” Anthropological Forum 25 (4): 329–349. doi:10.1080/00664677.2015.1054343.

- Phillips, A. 2004. “The History of the International System of Protected Area Management Categories.” Park 14 (3): 4–14.

- Pisano, E. 1974. “Estudios Ecológicos de la Región Continental Sur del Área Andino- Patagónico. II: Contribución ala Fitogeografía de la Zona del “Parque Nacional Torres del Paine”.” Anales Del Instituto Patagonia 5 (1–2): 59–104.

- Pollack, G., A. Berghöfer, and U. Berghöfer. 2008. “Fishing for Social Realities - Challenges to Sustainable Fisheries Management in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve.” Marine Policy 32: 233–242. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2007.09.013.

- Poudel, S., and G. P. Nyaupane. 2015. “Assessing the Impacts of Nature-Based Tourism: Host and Guest Perspectives.” Tourism Travel and Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally 31.

- Rantala, O., and A. Valtonen. 2014. “A Rhythmanalysis of Touristic Sleep in Nature.” Annals of Tourism Research 47: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2014.04.001.

- Rutherford, S. 2011. Governing the Wild: Ecotours of Power. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sack, R. D. 1986. Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, J. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Seamon, D. 1979. A Geography of the Lifeworld. Movement, Rest, and Encounter. London: Croom Helm.

- Sheller, M. 2014. “The New Mobilities Paradigm for a Live Sociology.” Current Sociology Review 62 (6): 789–811. doi:10.1177/0011392114533211.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environmental and Planning A 38: 207–226. doi:10.1068/a37268.

- Tsing, A. 2004. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- van Bets, L., M. Lamers, and J. van Tatenhove. 2017. “Governing Cruise Tourism at Bonaire: A Networks and Flows Approach.” Mobilities 12 (5): 778–793. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1229972.

- Vandergeest, P., and N. Peluso. 1995. “Territorialization and State Power in Thailand.” Theory and Society 24 (3): 385–426. doi:10.1007/BF00993352.

- Vela-Ruiz Figueroa, G., and F. Repetto-Giavelli, eds. 2017. Guía de Conocimiento y Buenas Prácticas para el Turismo en el Parque Nacional Torres del Paine. Punta Arenas: Ediciones CEQUA.

- Verbeek, D. H. P. 2009. “Sustainable Tourism Mobilities. A Practical Approach”. PhD diss., Tilburg University.

- Vidal, O. J. 2012. “Torres del Paine, Ecoturismo e Incendios Forestales: Perspectivas de Investigación y Manejo para una Biodiversidad Erosionada.” Revista Bosque Nativo 50: 33–39.

- Villarroel, P. 1996. “Efecto del Turismo en el Desarrollo Local. El Caso de Puerto Natales-Torres del Paine, XII Región.” Ambiente Y Desarrollo 12 (4): 58–64.

- Walpole, M., H. Goodwin, and K. Ward. 2001. “Pricing Policy for Tourism in Protected Areas: Lessons from Komodo National Park, Indonesia.” Conservation Biology 15 (1): 218–227. doi:10.1111/cbi.2001.15.issue-1.

- West, P., J. Igoe, and D. Brockington. 2006. “Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 251–277. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123308.

- Zillinger, M. 2007. “Tourist Routes: A Time-Geographical Approach on German Car-Tourists in Sweden.” Tourism Geographies 9 (1): 64–83. doi:10.1080/14616680601092915.