ABSTRACT

What does utopian thinking have to offer students and scholars of mobility? Could ‘mobile utopias’ assist us in envisioning futures – including those of mobility – differently? Do utopias provide a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between mobile societies and lives and the environments against which these are formed? By providing different ways of reading and arguing within different theoretical frameworks and doing so in relation to the contexts their contributions engage, the articles included in this special issue explore the limits of what the mobile utopias of the future might be, their social and spatial dimensions, and their totalizing, fragmentary, or, personal definitions. As a whole, the issue contributes to the intellectual project of how to turn utopia into a method, as Levitas, Jameson, Harvey, and others have long encouraged us to do. With a few exceptions, utopias have not received the attention they deserve from mobilities scholars. Our aim in putting together this special issue is to redress this balance and invite further reflection on what utopian thinking might offer current debates in mobilities scholarship. This Introduction draws connections across approaches, foci, methods, geographies, and sources, including those deployed in the issue’s six articles, in the interest of excavating possible hopeful orientations through critique. Central to this is the recognition of the significance of critiquing the images of mobility which circulate widely (think of drones) and of the necessity to listen attentively to voices overlooked by mobility futures which stand far removed from the reactions and feelings of people in their everyday worlds. Ours is an invitation both to pay close attention to what utopian thinking does – rather than what utopia is – and to help us carve out a new intellectual space where to reflect on the how, when and where mobilities and utopias meet, now, but also in the past, and in the future.

KEYWORDS:

If society is now the laboratory, then everyone is an experimental guinea-pig, but also a

potential experimental designer and practitioner.

Felt et al (Citation2007)

Utopias and dystopias are histories of the present.

Gordin, Tilley and Prakash (Citation2010, 1).

Tradition and utopia cannot be disconnected.

Siebers (2013, 62).

What does utopian thinking have to offer students and scholars of mobility? Could ‘mobile utopias’ assist us in envisioning futures – including those of mobility – differently? Do utopias provide a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between mobile societies and the environments against which they are formed?

Writing in Citation1989, Krohn and Weyer observed how society and the larger environment had become the laboratory. In the process, everyone has become a subject of and in experimentation. Not only does this demand new scientific subjectivities and response-abilities (Haraway Citation2010; Freudendal-Pedersen Citation2014), but it also entangles everyday life in ‘experiment earth’ (Stilgoe Citation2015). Most people ‘are unaware of the systemness of their daily practices’ (Urry Citation2016, 73) in this experiment. Yet ‘the science is in’, showing that what the 7.5 billion people on the planet do every day, especially those in the global North, aggregates to reduce the earth’s capacity to support human flourishing (Urry Citation2016, 38). The Anthropocene is shaped by this systemness. The environmental dynamics of this new geological epoch are perhaps the ones posing the most apparent challenges: biodiversity loss, significant reductions in wildlife, species extinction, soil erosion, and climate-crisis related events, including the millions of people affected by the record-breaking 2017 series of hurricanes. But these challenges are by no means the only troubles we are facing. 244 million people are on the move across borders worldwide, 65.6 million of them displaced by conflict and persecution. By 2050, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) warns, there could be 200 million people displaced by climate change. Together with the movement of cheap arms and weapons this puts many societies in permanent conflict with each other or on the edges of war and violence. Intra-societal inequalities are rising, too, splintering the social from within. Gripped by the compulsive pursuit of growth and a culture of fear, many high-tech societies turn to digital technologies and surveillant assemblages to control people’s behaviour. This ‘partial return to an older, observational … political power of the visualization and mapping of administratively derived data about whole populations’ (Ruppert, Law, and Savage Citation2013) brings with it a crisis of democracy which undermines a sense of experimental response-able subjectivity in relation to the economic, political, scientific, technological and environmental dimensions determining how societies flourish, adapt, change and evolve.

Too much dystopia for utopia? We think not. This special issue invites reflection on the necessity of envisioning alternative futures from a place enabled by hope rather than risk, crisis and fear. It builds on ongoing work around ‘mobile utopias’ at Lancaster University in the UK, in particular the AHRC-funded project ‘Mobile Utopias 1851-2051ʹ and the international conference Mobile Utopia: Pasts, Presents, Futures, which took place on 2–5 November 2017, joining the work of three main international academic and professional networks, namely, the Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster, the Cosmobilities Network, and T2M – International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic and Mobility. As part of the Mobile Utopias project, two of the editors of this special issue (Büscher and López Galviz) organized with Lancaster colleagues a series of workshops and events during which we asked participants to tell us what their utopia in 2051 might be. Unsurprisingly, the response was diverse, plural, stimulating and, often, completely unexpected. This isn’t the place to discuss the data collected nor the preliminary findings of this project. However, two of the images we gathered at two different project events are a fitting vehicle to introduce two broad themes which are developed in full by the articles of this special issue.

As its heading makes clear, depicts ‘mobile utopias’ of the kind familiar to those interested in the future of mobility in the past, and reminiscent of powerful enduring images by the likes of Albert Robida in late-nineteenth-century Paris, and shortly after by Arturo Eusevi in Buenos Aires, Harvey Wiley Corbett, William Robinson Leigh, and many others (Duthilleul Citation2012). Theirs were the kinds of images that the spectacular film sets of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, released in 1927, would epitomize. The drawing is one of fourteen a scribe made during a workshop in Lancaster on 19 April 2016. The workshop, entitled ‘Mobile Utopias, 1851-2051ʹ, asked participants to imagine their vision of utopia in 2051, with an emphasis on the kind of everyday mobility they envisioned as being part of a not-too-distant future. To stimulate discussion, we prepared posters with historical and contemporary images and text, made available a range of ‘mobile’ personal objects, and circulated a number of questions about travel in 2051 related to family, shopping, holidays, seeing friends and relatives, and more. This resonated with the ‘lively experimentation with multiple methods’ (Jensen, Sheller, and Wind Citation2015; see also Büscher, Sheller, and Tyfield Citation2016) that has been central to mobilities research from the outset as well as a previous workshop on Mobile Futures organised jointly with the Centre for Mobility and Urban Studies, Aalborg University.

Figure 1. Postcard of ‘Mobile Utopias’ inspired by the discussions during a workshop in Lancaster on 19 April 2016. Drawing by Jess Milton. Scriberia.

The drawings, in turn, became a unique means of capturing a discussion that covered a wide range of topics, including the design of and behavior in public spaces; the relationship and important differences between road infrastructure and the vehicles that use it; the necessity and desire for undisciplined spaces; socially inclusive communities; diversification in higher and vocational education; driverless cars; all-year-round cycling; workshops for repairing and tinkering; the role of nostalgia in shaping visions of the future; generative locally-grounded ways of living; the greening of urban areas and the dispersion of food production. Mobility was central to each and every one one of these ideas as was the desire to think creatively about what life in Lancaster might and should have in store for us thirty-five years into the future.

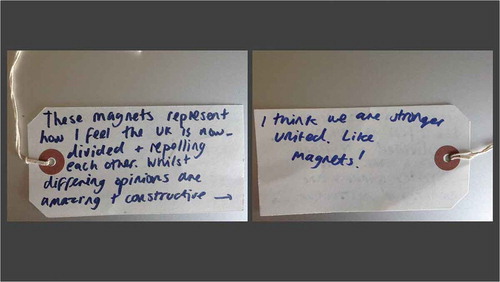

tells a different story. The photos are of both sides of a tag we collected at a different event, namely, a ‘Utopia Fair’ organized by the AHRC in Somerset House in London.Footnote1 The fair launched on 24 June 2016, the very same day when the results of the EU Referendum that year were released, showing that a majority of 51.9 per cent of voters had voted Leave. The irony wasn’t lost on the people who manned the thirty or so project stalls which the AHRC and Somerset House had invited to the fair in order to showcase work on utopias across the UK.

Figure 2. Tag collected at the Utopia Fair, Somerset House London, 24–26 June 2016. The anonymous handwritten text on both sides reads: ‘These magnets represent how I feel the UK is now divided + repelling each other. Whilst differing opinions are amazing + constructive I think we are stronger united. Like magnets!’.

Our approach to Mobile Utopia at the fair needed adjusting regardless of the referendum results. The question about one’s personal utopia in 2051 didn’t change, nor did the questions about everyday mobility in the future. But rather than a closed intimate workshop with residents of a small city in the northwest of England, we now had the open courtyard of a Georgian palace attracting thousands of daily visitors from all over the world for three days. As visitors walked from stall to stall, they learned about climate change, gothic stories, black history, utopian presses, faith in the London suburbs, the future of health and much more. Our strategy was to invite people to tell us – some were adventurous enough to draw – whatever they thought was important for them in a utopia of their choosing or making in 2051. Most visitors felt comfortable with writing on tags, which then became the very ornament of our stall as the fair progressed. We ended up with over 200 tags. Needless to say, our choice of the tag in is arbitrary. There were many tags addressing the EU referendum as well as the refugee crisis and the melting of ice caps in the Arctic. This tag came with the magnets mentioned in the handwritten text, one on each side, firmly coupled to each other. In hindsight, the tag tells the story of what happens when you take your utopia to the street and invite people to comment on it. Some might possibly join should your ideas resonate with the making of futures others find appealing, forming the desire to change the worlds around us for the better. Others won’t see the point, or, agree with the premise that movement and mobility have any role to play in their visions of the future.

For us, and in the context of this special issue, the contrast between the tag and the drawing serves a dual purpose. The drawing captures the familiar; the visual trope of endless circulation, often framed in terms of new technologies, which populates much of the thinking of the future of cities and places, East and West, North and South, since at least the mid nineteenth century (Dunn, Cureton, and Pollastri Citation2014; López Galviz Citation2013). The same could never be said of the message that the visitor to our Utopia Fair stall left for us with her tag. In contrast with the drawing, the message captures a personal feeling at a particular time in a particular place. Without creating too sharp a contrast, we may see something universal, a-contextual, and a-historical in the drawing, while the handwritten note is a personal response to the news on 24 June 2016 concerning the EU referendum. The drawing might be aligned with the mobilities of the future, in the way that, for example, drones become the main characters of the fictions and realities that Hildebrand and Sodero explore in their articles in this issue. The message might be a signal, weak, strong, or, otherwise, of voices that failed to be heard during what historians of the future may call a turning point in the history of Europe. Together, the drawing and the tag remind us of the significance of critiquing the images of mobility which circulate widely and of the necessity to listen attentively to voices overlooked by the common orientation of futures that stand far removed from the everyday reactions and feelings of people.

Our key aim in putting together this collection is to pay close attention to what utopian thinking does rather than what utopia is. With a few exceptions (Raithelhuber, Sharma, and Schröer Citation2018; Jensen and Freudendal-Pedersen Citation2012; Freudendal-Pedersen et al. Citation2017), utopias have not received the attention they deserve from mobilities scholars. For Urry (Citation2016, 93–95), utopias are one of six ‘methods for making futures’, in other words, ways in which the future can be made present in current thinking and action in the interest of directing change, either by encouraging certain routes, or, by inhibiting others. Ours is also a methodological question: it concerns the how, where and when of mobile utopias; the definition and process of how to turn utopia into a method, as Levitas (Citation2007, Citation2013), Jameson (Citation2010) and others have encouraged us to do. Moreover, we wish to stress the significance and utility of two aspects of utopian thinking, which we think will have particular resonance with students and scholars of mobilities: Utopia both as critique and orientation.

Seeing utopia as a method has a long tradition within critical action research where the productive forces of utopia have been at the center of enquiry (Jungk and Müllert Citation1987; Nielsen and Nielsen Citation2006; Freudendal-Pedersen et al. Citation2017). As Jameson (Citation2010) has argued, an important part of what utopian thinking does is revealing ‘the limits of our own imaginations of the future, the lines beyond which we do not seem able to go in imagining changes in our own society and world’, except, Jameson adds, ’in the direction of dystopia and catastrophe’. The limits of utopia are both social and spatial. These limits place utopias between the fragmentary, where desire is formed, and the totalising, self-contained, systematic vision, which takes us as far back as Thomas More’s (Citation1516) well-known, non-existent, non-locatable island. Building on the work of Ernst Bloch, Jameson develops the fragmentary in line with what he calls the ‘utopian impulse’ in contrast with the ‘utopian program’ of the plans for states, cities, gardens, which have characterised an important part of twentieth-century social and architectural thought. Raymond Williams identified a similar tendency in the utopias of the late 1970s and early 1980s, particularly in Britain. In his book Towards 2000, published in 1983, Williams distinguished between two different versions of utopia: one ‘systematic’ in its scope as proponent of alternative social orders which, by their very nature, constitute too a critique of the existing societies from which they emerge. This kind of utopia offers, Williams argued, ‘an imaginative reminder of the nature of historical change: that major social orders do rise and fall, and that new social orders do succeed them.’ Through their dreaming, which may take the form of ‘systematic nightmare’ (think of Totalitarianism) or ‘rosy fantasy’ (say, the refuge of the pastoral), utopias contrast existing and new imagined orders, leaving it up to the ‘general temper of the period’ to see them as better or worse (Williams Citation1983, 13). The key purpose of the other kind of utopias ‘is to form desire’. These utopias speak to feelings. Their purpose is private and subjective; particular and often subject to the marketisation of the lifestyle they purport (Williams Citation1983, 13–14).

Questions around the limits of what the mobile utopias of the future might be, their social and spatial dimensions, and their totalizing or fragmentary character, permeate the arguments of the articles contained in this issue. The articles illustrate and discuss alternative ways of envisioning the future, that of mobility in particular, including the extent to which we can and should critique visions of future mobility and transport by reference to the utopian and dystopian worlds these visions seek to create. The articles all point to a desire for change central to which is the critical potential to break through the ‘barriers of convention’ (Pinder Citation2005, Citation2015; Harvey Citation2000), most evocatively in the context of cities such as Delhi, Calcutta, Turku and Brighton. To an important degree, this is a process that involves recognizing alternatives and possibilities as well as devising the means by which critiques of the present might leave us in a better position to envision the future. A brief discussion of the work of Henri Lefebvre, who saw himself as a ‘partisan of possibilities’ (Citation1984, 192); David Harvey, who has summoned us to become the ‘conscious architects of our fates’ (Citation2000, 159); and Ruth Levitas whose work over the last three decades has centred on utopias and the ‘imaginative reconstitution of society’ will assist us in developing this point.

In his book The Survival of Capitalism (Lefebvre Citation1976 related the utopian possibilities to the working class’ ability to fight their way out of capitalism’s growth paradigm as the inherent logic that determines urban processes. With a philosophical starting point in the everyday life, Lefebvre emphasized the importance of lived lives and their inherent ability for change. Based on the work of the young Marx and inspired by Heidegger and Nietzsche, Lefebvre’s approach to utopias calls for the recognition and making of possible impossibilities. This idea is based on the opposition of what is possible and impossible. As Lefebvre noted (Citation1976, 36) ‘in order to extend the possible, it is necessary to proclaim and desire the impossible’. For Lefebvre, the impossible is often located in ideological blind spots – places of practice where constitutive socio-spatial relationships are opaque. Utopian critique can be a vehicle to recognise, reconsider and reimagine these opaque socio-spatial relationships, emphasizing the importance of everyday life and the kernels of change therein. The articles by Bagchi and Raleigh et al in this issue, for example, demonstrate the centrality of care for the environment by women in two feminist utopias set in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Calcutta and contemporary Delhi; and the possible consequences of overlooking care as a means of ‘nurturing the social networks to which one belongs’ in Turku, Finland. Combining the critique inherent in utopian thinking with the recognition of the potential of everyday life in cities enables us to highlight the precise role that care can play in the imagining and planning of future mobilities.

For Harvey, the utopian and revolutionary task remains one of defining ‘an alternative, not in terms of some static spatial form or even of some perfected emancipatory process. The task is to pull together a spatiotemporal utopianism – a dialectical utopianism – that is rooted in our present possibilities at the same time as it points towards different trajectories for human uneven geographical developments’ (Citation2000, 196). The contrast between geographies and histories is important as is the unevenness of how utopias of mobility get shaped by different kinds of processes, often involving the few while excluding the many. In his own utopia, Edilia, Harvey tells us that hearths are the basic unit of habitation within a model organised according to pradashas, neighbourhoods, edilias, nationas and regionas. All this after the world stock market collapsed in 2013; George Soros became the first president of the Concert of the World; the first Manifesto of the Mothers of Those Yet to be Born, a worldwide movement led by women ‘destroying every weapon and firearm they could find’, was published in 2019; and the utopian revolution was complete, with the whole world disarmed by 2020 (Harvey Citation2000, 257–81). The world stock market did experience an important shock earlier than 2013 (in 2008), but neither the Concert of the World, nor the Mothers, nor a much-needed disarmed world are among the building blocks of the world we currently live in. What both Harvey and Lefebvre invite us to dwell on is precisely the limits of and constraints within which our imagination of the future emerge. Demanding the impossible and creating the architecture of our common fate, we argue, implies both critique and propositional orientation.

The use of utopia as a method for the imaginary reconstitution of society (Levitas Citation2007, Citation2013) can be mobilised to imagine futures beyond precarity, supplementing reflections on the capitalocene (Tsing Citation2015) and the ‘chthulucene’ (Haraway Citation2016). For Levitas, utopia as method involves a process whereby archaeology, ontology and architecture come together to help reconfigure the societies we wish to live in. In its archaeological mode, utopia ‘unearths’ ideas and assumptions of social institutions embedded in visions of the future, it assembles a synthesis of the society envisaged from the visions’ fragments and critiques the intended and unintended consequences for its members. Building on utopian archaeology, utopia as ontology digs deeper, questioning what it means and what it should mean to be human in present and future societies. In its third move, utopia as architectural method pursues the imaginative reconstitution of society in light of the archaeological and ontological critique. Based on this threefold conceptual structure, Levitas (Citation2013) envisages the making of and thinking about utopias as an iterative process, ‘eternally’ accompanying societal change. Also inspired by Bloch, Levitas (Citation2007, 53) sees utopia as ‘the expression of desire for a better way of living. This allows for variations in form, content, and location, and enables us to see that the function of Utopia may be compensation, critique, or change.’

The articles of this special issue engage with Levitas’ work especially and do so in a variety of ways. The authors discuss different forms (technological, vital, fictional), each addressing distinct contents (blood, gender, night-time citizenship, cycling, and the role that care might play in future mobility choices), in locations which take us across South India, southern England, Finland, and the European Union as an institutional whole. By interrogating agency, structures and processes of change in the specific contexts their contributions focus on, the authors provide a series of counterpoints through which we see what might be utopian and dystopian of mobility futures in the making. We believe the diversity of approaches, foci, methods, geographies, and sources leaves us closer to a ‘genuine holistic thinking about possible futures’ (Levitas Citation2013, xi). Our aim is the drawing of meaningful connections in the interest of excavating possible hopeful orientations through critique. The issue thus provides different ways of reading and arguing within different theoretical frameworks contrasting several sources including the familiar ethnographies, diaries, documentary analysis, and photographs, as well as fictions both contemporary and past and what is known in Futures scholarship as ‘weak signals’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, drones are the foci of the first two articles by Sodero and Rackham, and Hildebrand. Theirs is an exploration of how drones have become one of the new means by which companies, governments and enthusiasts envision and claim the mobility utopias and dystopias of the future. Through a series of four vignettes, Sodero and Rackham construct ‘vital mobilities’ in 2050, in particular, the mobilities of blood, from donation to storage, distribution and use. Their article explores the possibilities as well as the limitations and likely consequences derived from fictional paths, each, in turn, favouring the transport of blood as local, big business, universal or spilled. Hildebrand, in turn, examines the conflicting yet enticing narrative lines of the short film Donny the Drone (2017). The film places the drone as the agent of change through fiction, blurring the boundaries between a humanist utopia and a drone-led dystopia. Interestingly, Hildebrand also considers important ramifications of other related yet different fictional drones, particularly in activism as per the work of Rexiste, a Mexican activist movement and boastful critic of the Mexican government, triggered in part by the disappearance of 43 students from a teacher training college in Ayotzinapa, southwestern Mexico (see for example the Wikipedia entry for 2014 Iguala mass kidnapping).

From vignettes of possible drone futures the issue moves on to alternative readings of urban spaces and future mobility choices. Through a close reading and analysis of photographs, Murray and Robertson reflect on the possibilities of a ‘porous utopia’, particularly concerning the night-time use of a street in Brighton, including the role that lighting techniques play in encouraging certain activities to the detriment and invisibility of others. Theirs is an ethnography that tests the limits and possibilities of ‘utopia as mobile method’ which incorporates ways of seeing, feeling and thinking. Reading photographs as ‘mediators of feeling that narrate our street space during the hours of darkness’, Murray and Robertson are able to reflect on what night-time citizenship means and what its relationship to the making and unmaking of utopias can and should be. In their article, Raleigh, Kirveennummi and Puustinen treat mobile utopias and future signals as tools to analyse ‘some prefigurative patterns in individual mobility practices.’ Discussing a group of mobility diaries kept by residents and workers of Turku, Finland, we learn about the signals of what the desirable features of future mobilities for people might be. The signals are striking because of their lived qualities and their embeddedness in everyday lives rather than their being the abstraction implicit in plans by, say, transport engineers and their models. By incorporating diaries into their analysis of future mobility in Turku, Raleigh, Kirveennummi and Puustinen highlight the importance of flexible day-care schedules, the anxiety that a driverless lorry is likely to cause to other drivers on the same route, choices of routes other than the shortest and fastest, all three of which might be a determinant factor for choosing to drive in the future or not. Recognising ‘signals’ such as these is also a means of foregrounding the values and aspirations that people have in light of the ‘systemness’ in which their (and our) lives are embedded. It is also a recognition of alternative renderings of the future which are ‘rich in meaning’ and with ‘the capacity to support care’ across generations.

Bagchi’s article asks us to consider the alternative spaces and times that fiction creates so that future better worlds – and the im/mobilities in them – might flourish and take root in the imagination. In her reading of two feminist utopias by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and Vandana Singh, we learn about the reaction against and the rendering of alternative realities in Delhi and today’s West Bengal in India and Bangladesh, at different times in their history. Although the generic tropes of transport technologies and time travel feature prominently, these are utopias that speak to and spring from particular contexts, different from the Western canon and its traditions, and, in the case of Hossain’s story Sultana’s Dream (1905), anticipating the connections made nearly two decades later between flying and freedom by Margery Brown and others, themselves similar to the connections that early female cyclists and motorists made in connection to the freedoms that the bike and the automobile afforded them (Pearce Citation2016, Dando Citation2018). If crafted through visions of flying and walking, these feminist utopias had a practical and lived dimension for the future and changing worlds of girls and women, and those of characters, real and imagined, on the margins of society.

Completing this special issue is Behrendt’s analysis of EU policy documents concerning smart mobilities and the Internet of Things (IoT). Central to her discussion are the ‘data asymmetries’ between automobility and cycling, which, as her analysis shows, reproduce a bias towards the car. Asking ‘who gets to speak in [these policy documents] and who remains silent’ is for Behrendt a means of revealing the interests and the assumptions behind what future European mobilities might look like and the prevalence of car-centred visions in these. What would it take for ‘cycling [to] take center stage in IoT policy conversations’ is one of the article’s main questions and, returning to Jameson we may add, what are ‘the lines beyond which we do not seem able to go in imagining changes in our own society and world’, that of mobility, in general; that of the worlds automobility has created in Europe and beyond, more specifically. The very absence of bikes in IoT EU policy reports, by no means a new phenomenon (Oldenziel et al. Citation2016), is a way of recognising the lines drawn on our behalf, shaping the future of mobilities by reference to the limits of, and the forces limiting, our imagination. The degree of familiarity or estrangement that we face when, for example, trying to imagine what Popan (Citation2019, 34) calls the London Bike and Train system, prominent in London in 2036 – in Popan’s own version of a mobile utopia – is an indication of how such limits are at work, officially, in policy documents, and personally, in what we deem acceptable to change in our everyday worlds.

Utopia is significantly more than the dream of a better future. It involves contextual critique and the crafting of orientations through which we can imagine and build lives better than at present. In this way, allowing ourselves to think and work with utopias opens up a clearer picture of which path-dependent and locked-in processes in mobile lives we wish to change.

‘[W]hen I consider and weigh in my mind all these commonwealths which nowadays anywhere do flourish […] I can perceive nothing but a certain conspiracy of rich men procuring their own commodities under the name and title of the commonwealth.’ Thus Raphael Hythloday, the main narrator of More’s Utopia, states nearing the end of his story in Book Two, the first book (of two) which More wrote. In her Introduction to More’s work and that of Francis Bacon and Henry Neville, Susan Bruce reminds us that one way of reading Utopia, and indeed any utopia, is as ‘an ideological critique of the dominant ideology’ (Citation2008 [1999], xv). The ideologies shaping our times are often hidden, buried beneath crisis, fear, risks, as well as the promises of technological progress and innovation. What happens to the wealth and the future of our commons in the process is something that should concern us all. Defining a new commonwealth of mobilities may be a good place to start so that we change course and capitalise on hope.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. See the site Utopia 500, Utopia in the 21st Century for further details: http://www.utopia500.org.uk, accessed on 12 September 2019.

References

- Bruce, S. 2008 [1999]. “Introduction and Note on the Texts." In Three Early Modern Utopias, Utopia, New Atlantis and the Isle of Pines.” Oxford World’s Classics, ix–xliv. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Büscher, M., M. Sheller, and D. Tyfield. 2016. “Mobility Intersections: Social Research, social Futures.” Mobilities 11 (4): 485–497. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1211818.

- Dando, C. E. 2018. “‘She Scorches Now and Then’: American Women and the Construction of 1890s Cycling.” In Architectures of Hurry – Mobilities, Cities and Modernity, edited by P. G. Mackintosh, R. Dennis, and D. W. Holdsworth, 25-44. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dunn, N., P. Cureton, and S. Pollastri. 2014. A Visual History of the Future. London: Foresight Government Office for Science, HMSO.

- Duthilleul, J.-M., edited by. 2012. Circuler. Quand Nos Mouvements Façonnent la Ville. Paris: Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine. Éditions Alternatives.

- Felt, U., and B. Wynne, eds. 2007. “Taking European Knowledge Society Seriously.” European Commission, Accessed 9 December 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/european-knowledge-society_en.pdf

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M. 2014. “Searching for Ethics and Responsibilities of Everyday Life Mobilities: The Example of Cycling in Copenhagen.” Sociologica 8 (1). doi:10.2383/77045.

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M., K. Hartmann-Petersen, A. Kjærulf, and L. D. Nielsen. 2017. “Interactive Environmental Planning: Creating Utopias and Storylines within a Mobilities planning Project.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60 (6): 941–958. doi:10.1080/09640568.2016.1189817.

- Gordin, M. D., H. Tilley, and G. Prakash. 2010. “Introduction Utopia and Dystopia beyond Space and Time.” In Utopia/Dystopia Conditions of Historical Possibility, edited by M. D. Gordin, H. Tilley, and G. Prakash, 1-17. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Haraway, D. J. 2010. “Sowing Worlds: A Seed Bag for Terraforming with Earth Others.” In Beyond the Cyborg Adventures with Donna Haraway, edited by M. Grebowicz, and H. Merrick. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harvey, D. 2000. Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Jameson, F. 2010. “Utopia as Method, or the Uses of the Future.” In Utopia/Dystopia Conditions of Historical Possibility, edited by M. D. Gordin, H. Tilley, and G. Prakash, 21–44. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Jensen, O., and M. Freudendal-Pedersen. 2012. “Utopias of Mobilities.” In Utopia: Social Theory and the Future, edited by M. H. Jacobsen and K. Tester, 197–217, Farham: Ashgate.

- Jensen, O., M. Sheller, and S. Wind. 2015. “Together and Apart: Affective Ambiences and Negotiation in Families’ Everyday Life and Mobility.” Mobilities 10 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.868158.

- Jungk, R., and N. Müllert. 1987. Future Workshops: How to Create Desirable Futures. London: Institute for Social Inventions.

- Krohn, W., and J. Weyer. 1989. “Gesellschaft als Labor: Die Erzeugung sozialer Risiken durch experimentelle Forschung.” Soziale Welt 40 (3): 349–373.

- Lefebvre, H. 1976. The Survival of Capitalism. London: Allison and Busby.

- Lefebvre, H. 1984. Everyday Life in the Modern World. New Jersey: Transaction Books.

- Levitas, R. 2007. “The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society: Utopia as Method.” In Utopia Method Vision. The Use Value of Social Dreaming, edited by T. Moylan and R. Baccolini, 47–68. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Levitas, R. 2013. Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- López Galviz, C. 2013. “Mobilities at a Standstill: Regulating Circulation in London C.1863–1870.” Journal of Historical Geography 42: 62–76. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2013.04.019.

- More, T. 2008 [1516]. “Three Early Modern Utopias, Utopia, New Atlantis and the Isle of Pines.” Utopia, translated by Ralph Robinson. In Oxford World’s Classics, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Susan Bruce. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nielsen, K. A., and B. S. Nielsen, eds. 2006. Methodologies in Action Research: Action Research and Critical Theory. Maastricht: Shaker publishing.

- Oldenziel, R., M. Emanuel, A. de la Bruhèze, and F. Veraart. 2016. Cycling Cities: The European Experience. Hundred Years of Policy and Practice. Eindhoven: Foundation for the History of Technology; Munich: Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society.

- Pearce, L. 2016. Drivetime: Literary Excursions in Automotive Consciousness. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Pinder, D. 2005. Visions of the City: Utopianism, Power and Politics in Twentieth- Century Urbanism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Pinder, D. 2015. “Reconstituting the Possible: Lefebvre, Utopia and the Urban Question.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (1): 28–45. doi:10.1111/ijur.v39.1.

- Popan, C. 2019. Bicycle Utopias. Imagining Fast and Slow Cycling Futures. Abingdon, UK, and New York: Routledge.

- Raithelhuber, E., N. Sharma, and W. Schröer. 2018. “The Intersection of Social Protection and Mobilities: A Move Towards a ‘practical Utopia’ Research Agenda.” Mobilities 13 (5): 685–701.

- Ruppert, E., J. Law, and M. Savage. 2013. “Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge of Digital Devices.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (4): 22–46. doi:10.1177/0263276413484941.

- Siebers, J. 2013. “Ernst Bloch’s Dialectical Anthropology.” In The Privatization of Hope. Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia, edited by P. Thompson and S. Zizek, 61–81. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Stilgoe, J. 2015. Experiment Earth: Responsible Innovation in Geoengineering. London: Routledge.

- Tsing, A. L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Urry, J. 2016. What Is the Future? . Cambridge: Polity.

- Williams, R. 1983. Towards 2000. London: Chatto & Windus, The Hogarth Press.