ABSTRACT

Travelling by train is an activity that many people engage in on a daily basis, which is rarely performed alone. While trains are locations where many different strangers potentially encounter each other, they are also portrayed as non-social transient places of passenger conflict and disharmony. Especially the rapid rise of mobile devices has changed the way people interact on board. This mobile ethnography – based on observations, travel-diaries and diary-interviews with 16 frequent travellers of Dutch Intercity trains – contributes to earlier studies on passenger sociality by specifically focussing on how social interactions are influenced by these mobile devices. The findings illustrate that using a mobile phone is indeed the most reported on-board activity and direct interactions are limited. Nevertheless, people on the train speak a very subtle non-verbal language that enables them to interact without engaging in extensive direct interactions. Mobile devices are thus not just enabling or constraining but have become inherent parts of socialising. Furthermore, most people do watch out for each other and try not to bother others. Discomforts emerge from different interpretations and compliances of codes of conduct.

Introduction

Surrounded by familiar and unfamiliar strangers, travelling by public transport is an activity rarely performed alone (Thomas Citation2009; Bissell Citation2010, Citation2016; Wilson Citation2011; Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017). As such, trains, trams, metros and buses can be seen as places of potential encounter, although they are highly controlled spaces in terms of access and regulation. Koefoed, Dissing Christensen, and Simonsen (Citation2017), for example, show how bus A5 transects different neighbourhoods in Copenhagen and serves as cross-cultural arena where people with different socio-economic backgrounds meet, despite also occasionally causing feelings of discomfort, irritation and aggression. In contrast, Kim (Citation2012) describes how passengers on long-distance Greyhound bus journeys slip into a personal space of the self by actively avoiding contact with others. Labelling public transport as ‘non-social transient places’, she claims that social interactions between travellers have become exceptional as the new social norm is ‘to pretend to be busy, distracted, or apathetic’ (Kim Citation2012, 269).

Such ‘situational withdrawal’ (Goffman Citation1961) from social interaction is possible without any electronic devices, for example by reading a book or gazing through the window. However, the rise of mobile devices has certainly reconfigured social relations in public transport (Berry and Hamilton Citation2010), allowing people to create their own ‘auditory bubbles’ (Bull Citation2005). Although this can enhance travellers’ sense of comfort (Lyons et al. Citation2013), it also potentially undermines the social sphere of the train. Hence, the relationship between the use of technology and the actual journey experience is complex (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016), leading Lyons et al. (Citation2013, 576) to wonder: ‘are mobile technologies ultimately on a trajectory of positively enriching the experiences of travel time or are they conversely set to undermine some of the characteristics of the “interspace” of travel by reconnecting it with the world beyond?’

There already is a well-established body of literature that discusses the experience and value of travel-time (e.g. Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2013; Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016), which acknowledges that time spent in public transport should not be seen as wasted or empty (Watts and Urry Citation2008), but as a personal gift (Jain and Lyons Citation2008) or an opportunity for encounters and public engagement (Jensen Citation2009; Bissell Citation2010, Citation2016; Wilson Citation2011; Koefoed, Dissing Christensen, and Simonsen Citation2017). The academic debate is often dominated by such dichotomous interpretations, such as juxtaposing the unwanted with the ‘ideal’ journey (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016) or the social with the non-social (Kim Citation2012). Similarly, the use of mobile technologies is said both to enable and restrict social relations in public spaces (Bull Citation2005; Lyons et al. Citation2013). However, according to Bissell (Citation2018), it is more meaningful to unravel the complexities of travel instead of framing it as necessarily bad or good. Following this reasoning, and taking into account that mobile devices and the way we interact with them have changed quickly since many earlier publications on passenger sociality (e.g. Watts Citation2008; Bissell Citation2010), this paper investigates how mobile devices affect the sociality of travelling by Intercity trains of the Dutch Railways (Nederlandse Spoorwegen, from now abbreviated as NS).

In the Netherlands, over half a million people travel by train every weekday (NS Citation2017). As such, train-travelling might be one of the most important everyday life practices producing meaning and culture (Jensen Citation2009; Bissell Citation2016), despite its mundane character (Löfgren Citation2008). By gaining in-depth insights in the (social) practices of train-travelling, including passengers’ behaviour, interpretations, motivations and desires, we research what kinds of social relations exist on the train and how these are affected by mobile devices, including (implicit) codes of conduct and the governance of on-board spaces. Similar to Bissell (Citation2010), we specifically focus on the interplay between bodies, technologies, materialities/matter, in order to understand the (perception of) sociality of a specific user group: young adults (aged 17 to 28). As we will discuss more elaborately below, this group is particularly interesting as they are not only the ‘digital generation’ (Lindstrom and Seybold Citation2003, 24), but also – more than other age groups – highly dependent on the train for transportation (Kampert et al. Citation2017).

Below, we first examine theoretical discussions on the train as social sphere, followed by our mobile ethnographic research design consisting of participant observations, diary-keeping by and in-depth interviews with 16 passengers. Our findings illustrate that despite the dominant use of mobile devices, Dutch trains are far from socially stagnant, but are instead complex interplays of not just people and their devices, but also non-verbal communication and flouted codes of conduct.

Trains as social spheres

Modes of public transportation – including trains, buses and metros – can be regarded as semi-public or collective spaces. Often being privately-owned spaces that cannot be accessed 24/7 and without a valid ticket, they are not open to everyone but still often perceived as public. As such, they should rather be seen as collective spaces, which are neither public nor private, but comprised of elements of both (De Solà-Morales Citation1992). Such semi-public spaces of travel are part of the public realm; ‘the world of strangers’ (Lofland Citation1998, 10) with fleeting, ephemeral relationships (Soenen Citation2006) and unfocused interactions (Goffman Citation1963).

According to Augé (Citation1995, 178), they are the archetype of non-spaces, ‘where solitudes coexist without creating any social bond or even social emotion.’ A journey simply provides passengers with a ‘series of snapshots’ ((Augé Citation1995, 86), without the possibility to take in the identities of the places travelled through. Yet, precisely this moving aspect distinguishes the train and other forms of public transport from other public domains. Normally people move through public space, while in public transport the space itself moves. At the same time, passengers are limited in their mobility; ‘framed by a metal cage’ (Watts Citation2008, 716), they are not able to disembark when they want and become encapsulated groups who are closed off from the outside world and challenged in their autonomy of action and privacy (Zurcher Citation1979). Passengers are therefore very mobile and immobile at the same time.

Although the above applies to all forms of public transport, it is important to outline briefly their differences. Local buses and metros, for example, have more frequent stops than regional trains or coach services, resulting in constantly shifting passenger groups (Wilson Citation2011) and a lower propensity to interact (Kim Citation2012). Trips are generally shorter in duration, while longer travel allows for more elaborate encounters, but also for passengers ‘unpacking’ (Watts Citation2008) and creating their private bubbles (Berry and Hamilton Citation2010; Kim Citation2012). Passenger densities in regional, inter-city trains – like the ones we investigated – are usually not as high as in intra-city subways at peak time, resulting in different strategies to cope with crowdedness (Aranguren and Tonnelat Citation2014). Also interior design influences which activities can (not) take place on-board (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016). Consequently, sociality can vary amongst modes of public transport and different spatio-temporal contexts. That said, we continue to draw on a broad range of literature below, not limited to trains.

As public realm, trains are potentially social spheres; they allow a heterogeneous mix of people to share space. Consequently, public transport not only links different places to each other, but should also be recognised as sites of connection in and of themselves (Jensen Citation2009; Wilson Citation2011). Watson (Citation2009) uses the term ‘everyday sociality’ to describe a range of social encounters in marketplaces; from intense interactions that contribute to the formation of social bonds, to people sharing the same space and engaging in ‘casual encounters’. Bissell (Citation2010, 284) applies the notion of sociality to public transport, and concludes that it emerges ‘through the complex interplay of technologies, matter, and bodies.’ Hence, sociality is not just about people sharing space and interacting, but also the specific location and material elements that determine the everyday experience of travelling with others. Like Watson, he also emphasises the importance of less intensive interaction by discussing ‘abstract’ (non-verbal) forms of communication that can nevertheless contribute to an affective atmosphere.

In this paper, we understand sociality as the manner in which people associate with one another while being on the train, including the deliberate choice not to engage in interaction. Most studies discussing sociality in public space are rather about being unsocial than social. For example, labelling the bus as ‘intensely public’ space, Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst (Citation2016) focus on the social discomfort that the close proximity of strangers might bring. However, their findings also illustrate that passengers who feel more comfortable in the social environment of the bus had better experiences than those who felt less comfortable. Similarly, Jensen (Citation2009) and Wilson (Citation2011) talk about unavoidable interactions with others, which are often forced but can nevertheless be meaningful.

Below, we argue that (the experience of) sociality is the outcome of socio-material relations; an ‘interplay’ (Bissell Citation2010) or ‘crafting’ (Watts Citation2008; Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017) of multiple aspects, such as ‘the arrangement of train seats, timetables, windows, tickets, newspapers, rain clouds, mobile phones, rucksacks, railway cuttings, and all the social and technological flotsam of train travel’ (Watts Citation2008, 712). Although these different aspects are all entangled, we draw them apart here for analytical purposes. Following Bissell (Citation2010), we specifically focus on how bodies, technologies and matter potentially influence sociality on the train.

Bodies

In trains, trams, buses and other forms of public transport, people from different backgrounds encounter each other in random compositions (Soenen Citation2006). According to Thomas (Citation2009, 3), ‘travelling on public transport forces strangers into an intimate social distance (…) typically reserved for people with strong personal relationships.’ Therefore, travelling can be a very uncomfortable experience, as strangers potentially intrude your personal, intimate space. Kim (Citation2012, 274) illustrates how people judge and deliberately discriminate their consociates based on their bodily characteristic (Thomas Citation2009; Wilson Citation2011), quoting one of her respondents: ‘you don’t want to sit next to a crazy person, a fatty, a chitchatter, and especially not a smelly one.’ As ‘encapsulated group’ (Zurcher Citation1979, 78), travellers form a cluster of people ‘who share physical but not necessarily social closeness for the purpose of attaining some goal or reaching some destination.’

Intimately sharing space, passengers adopt different strategies to deal with strange bodies and diversity, such as Goffman’s (Citation1963) rule of ‘fitting in’. This implies that people try to behave ‘properly’ to limit chances of creating agitation or conflicts. Rules – or ‘instructions for use’ (Augé Citation1995) – give indications of what is regarded as appropriate behaviour and can be prescriptive (‘place your bags under your seat’), prohibitive (‘smoking is not allowed’) or informative (‘the next station will be … ’). Quiet carriages are examples of places with clear rules on appropriate behaviour (i.e. no talking), in order to reduce ‘sensory infections’ (Watts Citation2008), such as ringing mobile phone and loud conversations. They first emerged in the early 2000s in several global cities such as London, Boston, and New York, and have since been implemented more widely in the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Japan (Hughes et al. Citation2017). Butcher (Citation2011) describes how such codes of conduct are not just disciplining but also comforting, as they provide clarity on how to behave.

In contrast, Goffman’s rule of fitting in is not about such prescribed rules, but about commonsensical, tacit interpretations of what proper behaviour is. One rule is ‘civil inattention’ (Goffman Citation1963, 84), giving other persons ‘enough visual notice to demonstrate that one appreciates that the other is present (…) while at the next moment withdrawing one’s attention from him so as to express that he does not constitute a target of special curiosity or design.’ Hirschauer (Citation2005, 41) refers to this as ‘display of disinterestedness without disregard.’ Such ways of minimizing expressivity, body contact and eye-contact are part of the ‘urban etiquette’ used to assure privacy and anonymity in order to ‘survive’ in a world of strangers (Lofland Citation1973). Below, we discuss how both technologies and other artefacts such as travel-bags help passengers in so-doing.

Technologies

Smart-phone use and the rise of other technologies (laptops, headphones, tablets) have greatly changed the way people use public space and public transport (Lyons et al. Citation2013; Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016; Hatuka and Toch Citation2016). Hampton, Sessions, and Albanesius (Citation2015) downplay both the extent and negative consequences of mobile phone use in public space (by arguing that it should be positively associated with an increased likelihood to linger and spend time in public space rather than with public isolation), while Lyons et al. (Citation2013) show that on-board talks only decreased a little between 2004 and 2010 despite a greater prevalence of mobile technologies potentially discouraging interaction between fellow passengers. Nevertheless, most studies emphasise how mobile communications have greatly reconfigured social relations in public space. Valentine (Citation2008) describes how the use of mobile phones has contributed to incivility in public space, locking individuals up in the private world of their conversations with remote others. According to Kumar and Makarova (Citation2008, 333): ‘we might be talking. But we are not talking to each other, not conversing. We are holding separate conversations on our mobile phones with others people who are not here in bodily presence but in remote or virtual space.’ Hatuka and Toch (Citation2016) argue that smartphone users are more detached from their physical surroundings, while Kim (Citation2012) describes how mobile technologies are increasingly used to pretend to be busy in order to avoid contact. Goffman (Citation1961) would describe such practices as ‘situational withdrawal’; by reading or listening to music, people are able to ‘zone-out’ and maintain their ‘stranger status’ (Zurcher Citation1979).

Although considered to be a defensive strategy (Thomas Citation2009), of course such practices are not necessarily intentionally defensive; one can simply enjoy browsing or listening music on their mobile phones as it provides ‘entertainment for the bored and connection to a friend for the lonely’ (Berry and Hamilton Citation2010). Also, mobile devices are said to influence travel time experience positively, as they provide passengers with more control to manage, manipulate, shape or craft their own experiences while riding a train or bus (Lyons et al. Citation2013; Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016). Bull (Citation2005, 353) argues that such ‘auditory bubbles’ create ‘a form of accompanied solitude for its users in which they feel empowered, in control and self-sufficient as they travel.’

Nevertheless, many studies illustrate how the use of mobile phones in public transport blurs the distinction between public and private (Soenen Citation2006; Berry and Hamilton Citation2010) and can have disruptive effects. Ling (Citation2004, 140) talks about ‘forced eavesdropping’ to describe how private phone calls compel other travellers to listen in and become part of someone’s personal life, potentially causing feelings of embarrassment to both callers and their involuntary audience. Other uses of technical devices such as reading the news, checking social media or listening to music are less disruptive, yet can also be considered as uncivil as they reduce chances of interaction. Although mobile phone use might thus create a private realm in which travellers feel comfortable, it potentially undermines the social sphere of the train.

Matters and materialities

Other factors that might influence the train’s sociality are its design, personal belongings such as bags, and the time and duration of the travel. Numerous studies have shown how people use their bodies and belongings to claim their territory in public space and create shields of privacy (Lofland Citation1973; Watts Citation2008; Kim Citation2012; Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017). Based on their research on metro use in New York City, Tonnelat and Kornblum (Citation2017) conclude that people look for the most defendable territory, one that minimises contact. Sommer (Citation1969) distinguishes two strategies: retreat (offence) and active defence seating. In a standard train layout, a window seat in a two-seater is considered as the ideal retreat position, as it limits contact to only one other person. However, having someone sit next to you hampers a hasty exit (Thomas Citation2009). Therefore, some people prefer aisle seats; a form of active defence seating that sends the message that the window seat is not to be occupied. People in retreat positions have similar ways of conveying such messages, like placing objects such as bags or jackets next to them to mark their territory. Kim (Citation2012) vividly describes the unspoken system of avoiding and inviting people to one’s adjacent seat by quoting her respondent Loretta:

Avoid eye contact with people getting on the [Greyhound] bus; lean against the window and stretch your legs on the other seat; place a large (sleeping) bag on the empty seat and blast your iPod, and if someone asks for the window seat, pretend you don’t hear them; place several small items on the empty seat so that it is clearly difficult and not worth their time to wait for you to clean the seat; pretend to sleep; sit on the aisle seat and look out the window with a “blank stare” (…) if all else fails, you can lie and say that you are saving the seat for someone (Kim Citation2012, 274–5).

Hence, a combination of body management and object placement, of retreat and defence, is used to avoid discomfort during the trip. Being able to choose one’s seating also gives a feeling of control. Research has shown that commuters who had the opportunity to pick their own seat and create a defendable space feel less stressed than people who embark at a more crowded moment of the journey (Lundberg Citation1976).

Timing and duration of the train ride thus influence its experience. Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall (Citation2017) show how the morning commute differs significantly from the evening in terms of travellers and their behaviour, with the former consisting of a more homogenous, less conflicting ‘passenger collective’. Similar to Watts (Citation2008), they also describe how the embodied experience of travelling precedes and exceeds time on the train, for example when feelings of stress or anxiety continue long after the carriage has been exited (Hughes et al. Citation2017, 754). Kim (Citation2012) argues that in contrast to short, fleeting interactions on the street, the long and encapsulated journey of a train or bus trip decreases the propensity to interact. Longer travels allow for more elaborate encounters to occur but enable passengers to ‘privatise’ public transport by using it as extension of the home or workplace (Berry and Hamilton Citation2010).

Mobile ethnographies

In order to investigate the sociality of train-travelling we relied upon a mobile ethnography carried out in the early summer of 2018. Mobile ethnographies focus on the world in transit, including the meanings and processes of movement. This method seeks to understand the mobile everyday by focussing on the interplay between observations, cognitions and sensations in motion (Urry Citation2007; Watts and Urry Citation2008). This section outlines three phases of data-generation, of which particularly phase two (diary-keeping) has methodological novelty as participant, auto-ethnographic observations (e.g. Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017; Watts Citation2008; Wilson Citation2011) and surveys (e.g. Lyons et al. Citation2013; Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016) are more common when studying public transport behaviour (with some notable exceptions like Ocejo and Tonnelat’s (Citation2014) use of subway diaries). We believe that the mixed method approach of using observations, travel-diaries and in-depth interviews allowed us to ‘capture both what people are doing with their time as well as why they are doing it and with what significance to them and others’ (Lyons et al. Citation2013, 577, original emphasis).

Observations

Phase one consisted of participant observations in the train by one of the authors, documenting in total 25 single trips and two sessions of about five hours each. In mobile ethnography, traditional participant observations are applied to the context of mobility, which means that the researcher not only observes the setting, but should also ‘experience, feel and grasp the textures, smells, comforts and discomforts, pleasures and displeasures of a moving life’ (Novoa Citation2015, 99). As part of the ‘moving fieldsite’ (Watts Citation2008), the researcher is not only ethnographer but also passenger and switches between these roles during the journey. As data on sociality of Dutch trains is largely missing, the observational phase was mainly used for explorative purposes by focussing on the practices of passengers, such as selecting a seat, spending time and encountering strangers. In addition, we observed material artefacts such as train design and travellers’ belongings. Next to these predetermined aspects, we tried to be ‘cognitively open’ to the unexpected as well. All observations were captured in elaborate fieldnotes. In addition, both authors are experienced commuters themselves, travelling by train to work on a daily basis. This allowed us not only to experience sociality and travel-time management ourselves (cf. Watts Citation2008) and hence relate to our respondents, but also to place our official observations in a wider perspective (of other times and trajectories).

The observations took place in the second-class compartment of Dutch ‘Intercity’ trains on different trajectories throughout the country (as opposed to other studies that tend to focus on a single route such as Wilson Citation2011; Hughes et al. Citation2017; Bissell Citation2016). These Intercity trains – in contrast to ‘Sprinter’ trains for shorter distances – are designed for medium to long journeys and hence offer amenities such as toilets and quiet carriages. We decided to focus on the Intercity as this type is used most often (52% of rides; NS Citation2017). Travelling in second class is more common than first class, making them potential meeting grounds for a wide range of people.

It is important to note that the Intercity is not a long-distance train like those discussed in other studies (Watts Citation2008; Bissell Citation2016; Hughes et al. Citation2017); average train commutes are 30–35 minutes (NS Citation2017) and no reservations are necessary. As the name denotes, Intercity trains run between rather than within cities, consequently they have a different level of crowdedness and atmosphere than, for example, metros or Sprinter-trains. Depending on the trajectory and timing of the journey, it is often possible to sit down; according to the 2017 annual report (NS Citation2017), chances for a seat are 95% even during rush hours. Moreover, Intercity trains are equipped with Wi-Fi, (folding) tables and increasingly also with power sockets, making certain activities such as working on laptops common practice.

Travel-diaries

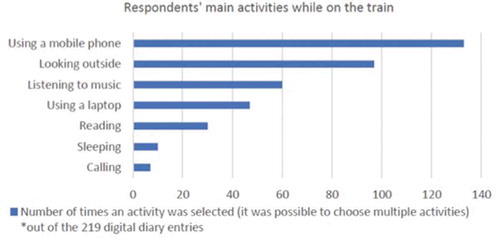

‘Observation yields rich data but is not exempt from bias, especially in an environment dominated by non-verbal communication’ (Tonnelat and Kornblum Citation2017, 231). Lyons et al. (Citation2013, 572) also state that simply knowing what people are doing through observations is not enough, as the same activity can have different appeal to different individuals and appeals might vary per journey. Therefore, we complemented the observations with participatory diary research. We turned train passengers in the Netherlands into ‘surrogate observers’ (Zimmerman and Wieder Citation1977) or ‘co-researchers’ (Ocejo and Tonnelat Citation2014) by asking them to keep journals of their travels. A call for participation was posted on various social media channels, including Facebook, LinkedIn and the ‘NS Community’, an online platform for people wanting to share experiences of riding the train. Sixteen travellers agreed to participate; 9 are female, 7 male; most of them are predominantly ‘must travellers’ commuting to work (4x), school (7x) or both (2x). Only two are recreational (or ‘lust’) travellers, although in practice all respondents travel for various purposes. All respondents have the Dutch nationality, which limits our options to research to what extent Dutch trains are meaningful in composing intercultural relations like Wilson (Citation2011) and Koefoed, Dissing Christensen, and Simonsen (Citation2017). With ages varying from 17 to 28, our respondents are relatively young. We did not specifically intend to study this particular age group, but it is an interesting population for numerous reasons. First, they are frequent train riders out of necessity, as opposed to, for example, the age group between 30 and 50 who often have the option to travel by car (Kampert et al. Citation2017). They are the potential passengers of the future that need to be attracted or retained, yet research has shown younger people have more negative experiences of public transport than older people (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016) and consequently find their travel time less worthwhile (Watts and Urry Citation2008; Lyons et al. Citation2013; Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016). Moreover, they are often seen as ‘perpetrators of disruptive acts’ (Ocejo and Tonnelat Citation2014, 497) and the digital generation that was ‘born with a mouse in their hands and a computer screen as their window to the world’ (Lindstrom and Seybold Citation2003, 24). Not surprisingly, using their mobile phone turned out to be the most performed activity while on the train (). Hence, young people are an interesting cohort to study the effects of mobile technologies on travel experiences.

The respondents were offered the choice to keep their diaries either on paper or digitally. In total 255 diary entries, documenting an equal number of trips, were collected over a period of 1.5 month. Some respondents made more trips than others, ranging from 8 to 23 trips reported per person. The diaries were used to reveal the participants’ travel behaviour while riding the train (where/when to board, travelling alone or together, selection of seats, ways to spend time, etc.), as well as reporting performances of other travellers with whom they interacted (or not) (Zimmerman and Wieder Citation1977).

Diary-interviews

‘Diaries can produce more detailed, more reliable and often more focused accounts than other comparable qualitative methods’ (Latham Citation2010, 191). As such, the diaries were used to verify our own observations, while also constituting a great basis for follow-up interviews. All sixteen diary-keepers agreed to a so-called ‘diary-interview’ (Zimmerman and Wieder Citation1977) of about 35–45 minutes, in which their notes were discussed in addition to more general questions on travelling by train. Since travelling is a very habitual, mundane practice (Löfgren Citation2008; Bissell Citation2016, Citation2018), the diaries proved to be a good way to remember what happened during their travels and to address specific situations. The diary thus helped ‘to determine what riders actually do, rather than what they think they do when they are interviewed in other locations’ (Tonnelat and Kornblum Citation2017, 231). The interviews were audiotaped, transcribed and coded for analysis. All quotes in this paper were translated from Dutch by the authors. To respect the respondents’ anonymity, we only use their first names.

Jointly, the three ethnographic methods yield rich data on the practice of riding the Dutch Intercity trains from a social perspective. In this paper, we specifically focus on on-board sociality, although we acknowledge that interaction can also occur on the platforms and train stations.

Social interaction on Dutch Intercity trains

The most recent NS commercial represents the train as a meeting place of a wide range of people, potentially even leading to romance. It depicts two flirting women and ends with the multi-layered quote ‘taste the freedom’. Being both applauded and criticised for its liberal message, the commercial obviously paints a very positive picture of train-travelling. This is very different from a Dutch satirical sketch, in which the conductor fines a passenger for not using his phone while travelling by train: ‘This is an obligatory phone carriage’ (Klikbeet Citation2018). The latter actually confirms our initial research findings more than the NS commercial. Both observations and travel-diary entries reveal that using a mobile phone is the most reported on-board activity (). Dutch Intercity trains indeed appear to be ‘technosocial spaces’ (Berry and Hamilton Citation2010, 112), extensions of the workplace or home where most travellers are seemingly withdrawn into their own ‘privatised auditory bubbles’ (Bull Citation2005, 344), listening to music or conversing to distant others over the phone. In contrast, conversations between passengers are rare, unless they are travelling with friends or acquaintances. From the 255 reported trips in the diaries, 205 (80%) were solo travels; travelling together mainly happens outside rush hours. Most respondents agree that such joint travels are nicer and make time go by faster, but only when travelling with people they feel comfortable with instead of being stuck in ‘forced conversations’. Hence, at first sight, the train appears a socially stagnant space, in which solo travellers have more attention for their phones than for fellow passengers. However, upon closer investigation, the sociality of the train is multifaceted, context-dependent and complex.

Mobile devices

Not being social seems to be the most common practice on-board Dutch trains. This already starts with passengers’ boarding and seating strategies. From the travel-diaries, it becomes clear that most participants have a strong preference for entering the train at the same spot each time, often a non-crowded entrance: ‘you choose a spot with as few people as possible, so you can enter the train as quickly as possible to make sure you are able to sit down’ (Jordan). Of course, the preferred seating arrangement is not always possible due to crowded circumstances. When offered the opportunity, people prefer to sit alone. According to Lola and Juliette, it is even considered inappropriate when people sit next or opposite someone when there are many vacant seats. Milou and Jennifer specifically choose two-seaters because they do not want to sit opposite to strangers. Matching Goffman’s (Citation1963) rule of civil inattention, they dislike their eyes constantly meeting those of opposite travellers. Sitting alone allows travellers to ‘protect’ their intimate and personal space. Respondents talk about creating ‘their own little space’ or ‘cocoon’, thus temporarily territorialising a small part of the train and actively ‘defending’ it (Sommer Citation1969) by placing bags on the chair next to them.

This presumably anti-social behaviour continues during the train ride. Many observed passengers are occupied with personal activities such as working on their laptops, playing on their mobile phones, wearing headphones or reading a newspaper. Most of our respondents even use multiple devices or activities to create their own private (auditory) bubble, for example by simultaneously listening to music and looking at their phones. However, according to our respondents, engaging in these activities is not primarily meant as situational withdrawal (Goffman Citation1961) from the discomfort of being surrounded by strangers. In contrast and confirming Jain and Lyons (Citation2008), the train ride is regarded as a gift; a space in between the public, private and ‘professional’ realm that allows them to work, eat or chill. For Dimitri, the train is ‘a riding office’, while others use their time on the train as transition time or time out (Jain and Lyons Citation2008).

Five respondents explain that they use technological devices such as (head) phones to actively ‘zone-out’ and signal that they do not want to be interrupted: ‘When I am using my phone, or reading with headphones on, I put up a barrier’ (Renske). However, for most respondents, the phone is not used to avoid but to enable contact, albeit with remote others instead of fellow passengers (cf. Kumar and Makarova Citation2008): ‘When I am at my internship, I don’t have much time to check my phone. Therefore, when I am riding the train home, I like to call my roommate to discuss dinner or I call my sister or parents to catch up. I enjoy doing those things’ (Lola). Many observed passengers make phone calls during their ride, suggesting this has become accepted social behaviour (Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016). Calls vary from short and concise to elaborate and personal, from soft and discrete to rather loud. Half of our respondents admit they sometimes call on-board, but of all them try to keep it short and shallow, not to bother others: ‘I try to adjust my volume a bit, but on the other hand, I don’t have to be completely silent there. People who travel together might be having louder conversations than I am having on the phone’ (Juliette). Yet, most respondents agree that loud or very personal conversations on the phone are inappropriate. Although such ‘forced eavesdropping’ (Ling Citation2004) might be discomforting, it can also provide entertainment: ‘At first, I am annoyed by a loud phone call, but after a while, I start to listen to the conversation. Sometimes you hear the most ridiculous things and I enjoy listening to those. It might not be a completely decent thing to do, but it has its kicks’ (Loek).

While direct interaction between passengers might thus be limited, sociality stretches beyond the physical confines of the train, turning travel time into time for making contact with distant others using the mobile phone (Jain and Lyons Citation2008). Nevertheless, this does not mean people are completely shut off when using such devices. Observations revealed various situations in which people seemingly withdrawn in their own private bubbles immediately responded when something required their attention, for example when the conductor entered the carriage. As such, they demonstrate a ‘highly attuned awareness of others’ (Wilson Citation2011, 636). Conversely, even when travelling and socialising together, people tended to wear headphones or be occupied with their phone or laptop, instead of being focused on their company. This illustrates that such mobile devices are not merely meant to shut others out, but that people are conditioned to use those devices at all times, even when travelling jointly.

Non(verbal) interaction

Most of the social relations on the train are with remote others, yet our respondents do interact with fellow passengers albeit often non-verbally (Aranguren and Tonnelat Citation2014; Kim Citation2012). For example, observations revealed that many travellers non-verbally show their intentions, by lingering a bit when they want to sit down, or they already pack their bags and sit up straight to signal they want to get off. Body language or body management (Lofland Citation1973) thus enables people to express their intentions without requiring engagement in an actual encounter.

Smiling and brief eye-contact are frequently used expressions of acknowledgement. Such gestures are seen as friendly and enjoyable: ‘When entering the train, I made eye-contact with two people who were already seated. This “greeting” made me feel welcome in the compartment’ (Daan’s diary-entry). Positive body language is thus associated with positive affect (Sherer Citation1974; Bissell Citation2010). Furthermore, people exchange glances when something unusual happens: ‘I made eye-contact with a fellow traveller as the conductor said something funny. I felt comfortable knowing that we probably thought the same thing’ (Jennifer’s diary-entry). Such unexpected situations, also negative ones like a delay, contribute to the community feeling, or ‘you-rationale’ (Tonnelat and Kornblum Citation2017), on board: ‘you have something in common, you are both affected by the same thing. This makes you feel somewhat connected and makes it easier for conversations to arise’ (Jordan). However, these are temporal bonds only; unlike Soenen (Citation2006), we did not find bonds between familiar strangers travelling the same trajectory evolving into primary relationships.

Nevertheless, almost all respondents do not mind chatting with strangers, although they rarely start such conversations themselves. In most cases, such encounters are even experienced as enjoyable (Epley and Schroeder Citation2014), as Daan notes in his diary:

This trip I had a lot of verbal encounters with other travellers. There was an elderly man sitting next to me who wanted to tell all about his visit to a museum in Leeuwarden. After a while, another older man entered the carriage, who I offered my seat. He was very happy about this and started talking about what the Bible says about helping others. The two elderly men got along really well and started performing some sort of a comedy-act. I really loved that those guys found each other and everyone was enjoying their presence. Later on, I asked a lady if she could pass me my bags, as I could not reach them. She was fine with helping me out and happily handed me the bags. It looks like the two guys really lightened up the mood in the carriage!

Such extensive conversations amongst strangers do not occur very often, but positively affect those involved. Yet Daan also indicates that it was fun during that recreational trip, but that he also enjoys silent travels. Jennifer concurs in her diary: ‘Having a conversation can be nice if you have time available and feel like it.’ Conversations are more common and appreciated during such recreational trips (Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016), as Lola describes: ‘my mind-set is different then and I am engaged in different activities (…) When you’re travelling in the afternoon and someone drops something, you smile at each other signalling that something like that could have happened to you as well. But when someone drops her mascara during the morning rush hour, I think: “watch yourself!”’

Timing of the trip, its purpose, the traveller’s mood and whom he/she is interacting with hence all influence whether an encounter is perceived as pleasant or unwanted (Wilson Citation2011). Overall, however, it seems the presence of older people induces more interaction: ‘I think that’s quite cute, an elderly lady travelling by train. I don’t know, I feel like smiling at her. Just to be social’ (Loek). Also Juliette explicitly smiles at older people. Although this could be seen as act of chivalry, it is also a matter of expectation. Most respondents assume that older people are open and looking for a chat: ‘They travel with a completely different motive, for recreational purposes. They like talking to others while on the train’ (Dimitri).

In general, this tendency to fill in other’s thoughts and feelings is something that occurs frequently on the train; ‘everyone thinks/does that’ was a phrase regularly used during the interviews. Due to the dominance of non-verbal interaction, train riders are very dependent on their own interpretation of other people’s behaviour and expressions. Thinking for others can be harmless, like Jennifer supposedly laughing about the same thing as her fellow traveller. However, it can also trigger irritation: ‘sometimes I feel people are deliberately putting their stuff away very slowly, as if they want to let you know that they are annoyed by you wanting to sit next to them’ (Joanne). Other respondents suspect that fellow travellers are annoyed by their behaviour. Jelle believed people disliked him eating a hamburger, while Jennifer had the impression people found her noisy after returning from a party. When asked how they knew they were annoying other people, it turned out they simply assumed this was the case, even though they did not receive any (non) verbal signals. Although this illustrates an awareness of acceptable behaviour within the context of the journey (Wilson Citation2011), it also indicates the danger of thinking for/about others, as Paul summarises: ‘the biggest mistake we make, is believing we know what others want or think, but we do not.’

Flouted codes of conduct

Despite these positive encounters described above, our respondents often complained about fellow consociates – although unlike Wilson (Citation2011) or Bissell (Citation2016) they rarely described real conflicts. Irritations vary per respondent and per situation, it indeed is a ‘circumstantial thing’ (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016): while it might be fun to be surrounded by tipsy, singing riders when you are one of them, like Juliette, they might get on your nerves when you are looking forward to a quiet trip. Loud noises (music, conversations) are mentioned most often as irritating, as well as smelly people, those who chew in an unappetizing way, passengers who get too close, staring people and those who leave their bags on a chair when it is crowded.

This initial reaction to highlight their annoyances probably has to do with the encapsulated context of the train, as mentioned by Pascal: ‘When you are outside, you can go wherever you like, you can escape if you want to, on the train you can’t.’ In this sealed-off environment, annoyances become easily exaggerated: ‘Once something gets on your nerves, it gets bigger and bigger’ (Jelle). Some respondents choose to flee unwanted situations by walking to another seat or compartment: ‘When someone is bothering me, I am gone in a second’ (Lola). However, she does this in a subtle way: ‘I just pretend to go to the toilet. I exaggeratedly look at the sign pointing at the toilet and then just go and sit somewhere else. I don’t want that person to feel like I am leaving because of them, so I pretend to leave for another reason. I don’t want to be unkind.’ This corresponds to Gintis (Citation2000) observation that people behave pro-socially, even when it concerns people they might never see again. In contrast to Lola, Renske feels uncomfortable changing seats, while Sandra does not want to be chased away.

Fleeing is thus not a popular strategy for dealing with annoying circumstances, but neither is speaking up. According to Jordan, ‘this is part of our zeitgeist: people do not really dare to speak up when things bother them.’ Although characterising himself as ‘a bit of a pussy’, Jordan is certainly not alone in his view. Daan equates speaking up with ‘seeking a confrontation’ and also Sandra thinks ‘it only leads to conflict (…) you merely have to accept the rules and behaviour of others, since it is a communal thing; you can’t start acting like a cop.’ Juliette refers to the train’s public character: ‘everyone is allowed to travel by train, I just have to accept that.’ Similarly, Loek mentions: ‘Who am I to tell that woman she is not allowed to tap her feet? (…) I just deal with it and say to myself: “it’s part of the ride, no big deal”’, while Joanne also believes she should ‘mind her own business.’

The respondents unanimously feel they do not have the right to confront others. Instead, they deal with irritating persons or situations by ignoring them or retreating in their own (auditory) bubbles. Dimitri softens his irritations with the thought he will not be in the train for long, while Sanne even takes responsibility for her own grievances: ‘If I chose to sit in a regular compartment instead of the quiet carriage, I would not speak up if something bothers me. In that case, it is my problem that I am annoyed.’

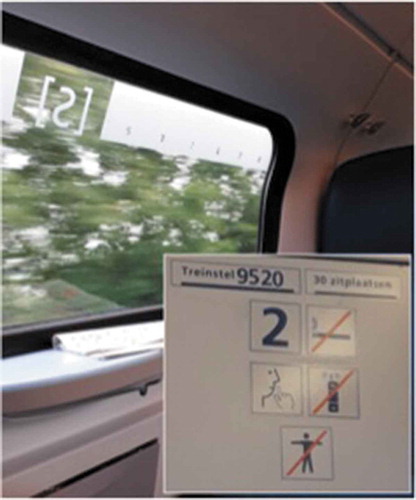

The quiet carriage often reappeared in the diaries and interviews. It was introduced in Dutch Intercity trains in 2003, at a time when such quiet carriages pioneered worldwide (Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017), in response to the rise of mobile phones. There are usually one or two of these carriages per train. The house rules of the NS read as follows (): ‘we really want it to be quiet in the Silence zone, and [you] should not disturb your fellow passengers with noisy conversations (including phones) or loud music anywhere in the train.’ Window stickers () indicating ‘silence’ (stilte) have to remind passengers to be quiet; something that is occasionally reiterated during conductor’s announcements.

Many respondents referred to the quiet carriage as space with clear rules and expectations, which empowered them to speak up. Though the code of conduct might come across as limiting or even patronising, it offers our respondents great comfort: ‘In the quiet carriage, you know you have to be silent, there you are allowed to say something if someone is loud. In a “normal carriage”, you would only speak up based on unwritten behavioural rules’ (Jelle). Renske agrees and feels she has ‘the right’ to speak up in the quiet carriage. Our observations also confirm that requesting other passengers to be silent is common practice in Dutch quiet carriages, without seemingly leading to conflict (with some exceptions, see De Gelderlander Citation2019). In contrast, Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall (Citation2017) found that travellers in Australian quiet carriages use less direct ways to manage noise interruptions, such as glancing, head-shaking and eye-rolling; verbal confrontations only occurred if the interruption was sustained for a long period of time.

Travelling in Dutch quiet carriages offers our respondents a perception of being in control: people know what is expected and accepted, and feel they have the right to address unwanted behaviour. Moreover, the clear rules of the quiet carriage make it easier for travellers to comply with Goffman’s (Citation1963) rule of ‘fitting in’ and to get into the right ‘passenger role’ (Zurcher Citation1979). Chances of agitation and conflict are limited when rules are clear; the presence of a homogenous group of silent people or ‘passenger collective’ (Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017) with similar expectations contributes to a comfortable journey.

The NS is currently adjusting the designs of their new Intercity trains, distinguishing two ‘zones’ with each different seating arrangements: the ‘work-and-rest’ carriages, including quiet zones (mainly two-seaters), and the ‘meet-and-greet’ carriages (with four-seaters and sofas). These adjustments illustrate that the NS increasingly acknowledges the importance of passengers’ emotional well-being, in addition to instrumental service provision such as punctuality.

Conclusions and discussion

The sociality on the train is dependent on many factors; not only the people present (and their mood, reason for travelling, experience and choice of seating), but also materialities and technologies (particularly the use of mobile devices), crowdedness and (unwritten) rules. Consequently, it is not a fixed but fluid concept; assembled differently in every given context (Watts Citation2008; Wilson Citation2011; Bissell Citation2018). There is also variability across travel experiences (Lyons et al. Citation2013) – some people enjoy social contacts more than others, and sociality might be appreciated during particular (often recreational or afternoon) trips and not at other times. Consequently, in essence, no train ride is the same (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2016), but it is nevertheless possible to distinguish certain trends in behaviour and representation.

Contrary to (media) discourses on the alleged lack of social behaviour in public transport (Kim Citation2012; Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017; Klikbeet Citation2018), our research shows that the train is far from socially stagnant. Although most respondents are mostly withdrawn into their own (auditory) bubbles (Bull Citation2005) and admit to prefer phone calls with family and friends over conversations with fellow travellers, this does not mean that such bubbles are impenetrable: when a situation requires rides to act or pay attention, they immediately know how to respond. Passengers are not seeking to act distinctly social, but they do look out for each other and are able to communicate in very subtle ways. Three findings are particularly important in understanding sociality on the train: (1) the role of technological devices, (2) the values but also dangers of non-verbal sociality, and (3) the discomforts emerging from different interpretations and compliances of codes of conduct.

First, our findings bring nuance to the dominant idea that mobile devices like laptops, headphones and mobile phones contribute to incivility (Valentine Citation2008), detachment (Hatuka and Toch Citation2016) and ignorance (Kumar and Makarova Citation2008; Kim Citation2012). Certainly, these devices have greatly reconfigured (the perception of) travel time (Jain and Lyons Citation2008; Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016) and social relations in public spaces. Our observations illustrate that passengers are often very self-absorbed; gazing at their screens, seemingly shutting others out. However, similar behaviour can be observed when people travel together; it is not uncommon to see young people socialising with each other, while each wearing earphones. As habitus, mobile phones have become ubiquitous, integral parts of social life (Lyons, Jain, and Weir Citation2016, 96). Simply recognising such devices as limitations to direct interaction would negate peoples’ skills to multitask and quickly shift focus when attention is needed. Mobile devices are as much interwoven in social interactions as a person’s voice, body language or communication skills; they have become part of what Gell (1998, quoted in Watts Citation2008: 714) refers to as ‘distributed personhood.’ Social relations are not per se limited or facilitated by them; instead these devices are inherently and increasingly part of these relations. This might be particularly so for the younger, ‘digital’ generations (Lindstrom and Seybold Citation2003) that we investigated in the present study, although we expect little differences with other generations that have also embraced these technologies.

Second, we found little direct interactions on the train, but myriad examples of subtle, non-verbal communication (Lofland Citation1973; Wilson Citation2011), which enables riders to communicate without actually engaging in (verbal) encounters. Their strategies are more complex and wide-ranging than merely placing bags on the next seat (Kim Citation2012) or showing civil inattention (Goffman Citation1963), but also comprise of facial expressions (smiling, nodding) and silent negotiations and unspoken conversations (cf. Aranguren and Tonnelat Citation2014). Our respondents refrain from direct interactions because they view the train as a functional rather than social space. As ‘mobile office’ (Bissell Citation2010), the train offers opportunities to work or relax, or simply ‘my-time’ (Jain and Lyons Citation2008) that should not be interrupted by conversations with strangers. While this seems to be a deliberate choice, a more pressing finding illustrates that limited conversation is not just a matter of not wanting, but also not knowing how to start a conversation. Most respondents have no idea what to talk about and believe others do not want to engage in conversation either (Epley and Schroeder Citation2014). This is unfortunate, as temporal contact initiated by others is often considered as pleasant and convivial (Lyons et al. Citation2013). Moreover, relying on non-verbal contact only also creates room for misconception as it depends on one’s own interpretations and judgement (Burgoon, Guerrero, and Floyd Citation2010), for example regarding what is believed to be proper behaviour.

Third, these findings illustrate that sociality on the train is often non-discursive; based on unspoken words and unwritten rules. This unarticulated situation seems to result in discomforts emerging from different interpretations of and compliances to codes of conduct. Hughes, Mee and Tyndall (Citation2017, 743) highlight the importance of routines and expectations to facilitate comfort and consistency by claiming that many commuters seek a consistent travel experience. That might explain why our respondents enjoy the predictability and feeling of being in control that they experience in the quiet carriage. Here they know what to expect from fellow passengers and which ‘passenger role’ (Zurcher Citation1979) to take on. Furthermore, the clear rule (being silent) empowers riders to speak up if someone disobeys. This raises the question to what extent more rules and regulations are needed, or if they need to become more discursive – for example by providing clear guidelines at the train’s entrance (see ) – and/or officially monitored (Wilson Citation2011).

Published in 1862, when only few people were acquainted with travelling by train, the Railway Traveller’s Handy Book contained rules, suggestions and advice to teach people how to become a railway traveller (Löfgren Citation2008; Bissell Citation2010). It not only provided technical information on tickets and class carriages, but also described appropriate ways (not) to interact. Such guidelines seem particularly relevant when a new mode of transportation or practice is introduced, like the opening of a metro system in Delhi in 2002, as described by Butcher (Citation2011, 254). She depicts a long list of disciplining codes of conduct such as ‘make way for the physically challenged’ and ‘don’t sit on the floor of the carriage’. These rules were criticised for being patronising, subjective and affecting some passengers more than others, yet ‘it could be argued that some level of instruction was necessary. It might even be thought of as comforting rather than disciplining to have instrumental instructions on how to use the Metro’ (Butcher Citation2011, 243).

Rules can thus be disciplining and comforting at the same time, they can offer clarity and a sense of being in control even when passengers have already learned how to be a railway traveller. However, we are not advocating for more surveillance and regulation on the train, nor are our respondents. In fact, one could argue that is not a lack of rules but a lack of compliance that is causing most discomfort, as rules are flouted. Challenging those people who have failed to show consideration can be stressful and potentially cause conflict (Hughes, Mee, and Tyndall Citation2017; De Gelderlander Citation2019). This applies to all public spaces, but even more so to the train carriage as ‘sealed capsule with little escape’, as Bissell (Citation2016, 398) illustrated in his account of a conflicting event on the Sydney-Wollongong commute.

Our results illustrate that riders get great comfort in knowing what is expected from them, and subsequently, what is not. Making these expectations more discursive – as done in the Railway Traveller’s Handy Book – could improve their travelling experience. Such ‘instructions for use’ (Augé Citation1995) should not be formulated as solely prohibitive (‘don’t do this’), but also hint at positive behaviour (‘it is okay to have conversations with fellow passengers here’). Conductors could play a decisive role here, not necessarily as ‘law-keepers’, but as so-called ‘street-level bureaucrats’ gently reminding travellers of codes of conduct and appropriate behaviour in a playful manner, and acting as intermediary to achieve what Goffman (Citation1959) and Tonnelat and Kornblum (Citation2017) denote as ‘working consensus’ amongst passengers. Such interventions to improve on-board experiences (similar to Watts and Lyons’ (Citation2010) ‘travel remedy kit’) are worthwhile exploring in more depth. After all, NS and other transport operators are becoming increasingly aware that a positive travel experience goes beyond instrumental service provision and also includes the creation of comfortable social environments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the three anonymous referees, whose comments greatly helped to improve the paper. Moreover, we would like to express our gratitude to all travellers participating in this research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aranguren, M., and S. Tonnelat. 2014. “Emotional Transactions in the Paris Subway: Combining Naturalistic Videotaping, Objective Facial Coding and Sequential Analysis in the Study of Nonverbal Emotional Behaviors.” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 38 (4): 495–521. doi:10.1007/s10919-014-0193-1.

- Augé, M. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso.

- Berry, M., and M. Hamilton. 2010. “Changing Urban Spaces: Mobile Phones on Trains.” Mobilities 5 (1): 111–129. doi:10.1080/17450100903435078.

- Bissell, D. 2010. “Passenger Mobilities: Affective Atmospheres and the Sociality of Public Transport.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 270–289. doi:10.1068/d3909.

- Bissell, D. 2016. “Micropolitics of Mobility: Public Transport Commuting and Everyday Encounters with Forces of Enablement and Constraint.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2): 394–403.

- Bissell, D. 2018. Transit Life: How Commuting Is Transforming Our Cities. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Bull, M. 2005. “No Dead Air! The iPod and the Culture of Mobile Listening.” Leisure Studies 24 (4): 343–355. doi:10.1080/0261436052000330447.

- Burgoon, J., L. Guerrero, and K. Floyd. 2010. Nonverbal Communication. London: Routledge.

- Butcher, M. 2011. “Cultures of Commuting: The Mobile Negotiation of Space and Subjectivity on Dehli’s Metro.” Mobilities 69 (2): 237–254. doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.552902.

- Clayton, W., J. Jain, and G. Parkhurst. 2016. “An Ideal Journey: Making Bus Travel Desirable.” Mobilities 12 (5): 706–725. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1156424.

- De Gelderlander. 2019. “Zo mondt geklaag over een kind in een stiltecoupé uit in een vechtpartij met de conducteur in Dieren.” De Gelderlander, July 2.

- De Solà-Morales, M. 1992. “Openbare En Collectieve Ruimte: De Verstedelijking Van Het Privé-domein Als Nieuw Uitdaging.” OASE 22: 3–8.

- Epley, N., and J. Schroeder. 2014. “Mistakenly Seeking Solitude.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 143 (5): 1980–1999. doi:10.1037/a0037323.

- Gintis, H. 2000. “Strong Reciprocity and Human Sociality.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 206 (2): 169–179. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2111.

- Goffman, E. 1959. Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

- Goffman, E. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Immates. New York: Doubleday.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. New York: Free Press.

- Hampton, K. N., L. Sessions, and G. Albanesius. 2015. “Change in the Social Life of Urban Public Spaces: The Rise of Mobile Phones and Women, and the Decline of Aloneness over Thirty Years.” Urban Studies 52 (8): 1489–1504. doi:10.1177/0042098014534905.

- Hatuka, T., and E. Toch. 2016. “The Emergence of Portable Private-Personal Territory: Smartphones, Social Conduct and Public Spaces.” Urban Studies 53 (10): 2192–2208. doi:10.1177/0042098014524608.

- Hirschauer, S. 2005. “On Doing Being a Stranger: The Practical Constitution of Civil Inattention.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 35 (1): 41–67. doi:10.1111/jtsb.2005.35.issue-1.

- Hughes, A., K. Mee, and A. Tyndall. 2017. “‘Super Simple Stuff?’: Crafting Quiet in Trains between Newcastle and Sydney.” Mobilities 12 (5): 740–757. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1191797.

- Jain, J., and G. Lyons. 2008. “The Gift of Travel Time.” Journal of Transport Geography 16 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.05.001.

- Jensen, O. 2009. “Flows of Meaning, Cultures of Movement: Urban Mobility as a Meaningful Everyday Life Practice.” Mobilities 4: 139–158. doi:10.1080/17450100802658002.

- Kampert, A., J. Nijenhuis, M. van der Spoel and H. Molnár-in 't Veld. 2017. Nederlanders en hun auto: Een overzicht van de afgelopen tien jaar. Den Haag: CBS

- Kim, E. C. 2012. “Nonsocial Transient Behavior: Social Disengagement on the Greyhound Bus.” Symbolic Interaction 35 (3): 267–283. doi:10.1002/symb.21.

- Klikbeet. 2018. “Trein Controle.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gcLSMhsPlro

- Koefoed, L., M. Dissing Christensen, and K. Simonsen. 2017. “Mobile Encounters: Bus 5A as a Cross-Cultural Meeting Place.” Mobilities 12 (5): 726–739. doi:10.1080/17450101.2016.1181487.

- Kumar, K., and E. Makarova. 2008. “The Portable Home: The Domestication of Public Space.” Sociological Theory 26 (4): 324–344. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00332.x.

- Latham, A. 2010. “Diaries as a Research Method.” In Key Methods in Geography, edited by N. Clifford, S. French, and G. Valentine, 189–202. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Lindstrom, M., and P. Seybold. 2003. BrandChild. London: Kogan.

- Ling, R. 2004. The Mobile Connection: The Cell Phone’s Impact on Society. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Löfgren, O. 2008. “Motion and Emotion: Learning to Be a Railway Traveller.” Mobilities 3 (3): 331–351. doi:10.1080/17450100802376696.

- Lofland, L. 1973. A World of Strangers: Order and Action in Public Space. Illinois: Waveland Press.

- Lofland, L. 1998. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Lundberg, U. 1976. “Urban Commuting: Crowdedness and the Catecholamine Excretion.” Journal of Human Stress 23: 26–32. doi:10.1080/0097840X.1976.9936067.

- Lyons, G., J. Jain, and I. Weir. 2016. “Changing Times: A Decade of Empirical Insight into the Experience of Rail Passengers in Great Britain.” Journal of Transport Geography 57: 94–104. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.10.003.

- Lyons, G., J. Jain, Y. Susilo, and S. Atkins. 2013. “Comparing Rail Passengers’ Travel Time Use in Great Britain between 2004 and 2010.” Mobilities 8 (4): 560–579. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.743221.

- Novoa, A. 2015. “Mobile Ethnography: Emergence, Techniques and Its Importance to Geography.” Human Geographies 9 (1): 87–107.

- NS. 2017. NS Jaarverslag 2017. Utrecht: Nederlandse Spoorwegen.

- Ocejo, R., and S. Tonnelat. 2014. “Subway Diaries: How People Experience and Practice Riding the Train.” Ethnography 15 (4): 439–515. doi:10.1177/1466138113491171.

- Sherer, S. E. 1974. “Influence of Proximity and Eye Contact on Impression Formation.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 38 (2): 538. doi:10.2466/pms.1974.38.2.538.

- Soenen, R. 2006. “An Anthropological Account of Ephemeral Relationships of Public Transport: A Contribution to the Reflection of Diversity.” Paper presented at the EURODIV Conference, Leuven, September 19–20

- Sommer, R. 1969. Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Thomas, J. 2009. The Social Environment of Public Transport. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Tonnelat, S., and W. Kornblum. 2017. International Express: New Yorkers on the 7 Train. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Urry, J. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

- Valentine, G. 2008. “Living with Difference”: Reflection on Geographies of Encounter.” Progress in Human Geography 32: 323–337. doi:10.1177/0309133308089372.

- Watson, S. 2009. “The Magic of the Marketplace: Sociality in a Neglected Public Space.” Urban Studies 46 (8): 1577–1591. doi:10.1177/0042098009105506.

- Watts, L. 2008. “The Art and Craft of Train Travel.” Social & Cultural Geography 9 (6): 711–726. doi:10.1080/14649360802292520.

- Watts, L., and G. Lyons. 2010. “Travel Remedy Kit: Interventions into Train Lines and Passenger Times.” In Mobile Methods, edited by M. Büscher, J. Urry, and K. Witchger, 89–213. London: Routledge.

- Watts, L., and J. Urry. 2008. “Moving Methods, Travelling Times.” Environment and Planning D 26 (5): 860–874. doi:10.1068/d6707.

- Wilson, H. F. 2011. “Passing Propinquities in the Multicultural City: The Everyday Encounters of Bus Passengering.” Environment and Planning A 43 (3): 634–649. doi:10.1068/a43354.

- Zimmerman, D. H., and D. L. Wieder. 1977. “The Diary: Diary-interview Method.” Urban Life 5 (4): 479–498. doi:10.1177/089124167700500406.

- Zurcher, L. 1979. “The Airplane Passenger.” Qualitative Sociology 193: 77–99. doi:10.1007/BF02429895..