ABSTRACT

Cycling on the pavement is commonly seen in urban environments despite often being prohibited. This study explores this practice by analysing cycling on pavements in the wider socio-technical context in which it occurs. Using data from two field studies and one questionnaire study, as well as applying a Social Practice Theory (SPT) based analytical approach, the study explores the frequency of cycling on the pavement. The results show that riding on the pavement is common among cyclists. Three main configurations of meaning, material and competence constitutes this practice which is summarised as follows: avoiding the space of the car, increasing smoothness of the ride and unclear infrastructure design. Cycling on the pavement can be regarded as a way of managing safety and risk, seeking more efficient and comfortable paths of travel, as well as the outcome of perceiving the infrastructure as ambiguous. Overall, the study argues that cycling on the pavement is a consequence of skewed power relations between different modes of transport, as well as policies, urban planning and infrastructure not harmonising with demands for safe and smooth travel by cyclists.

Introduction

The necessity of shifting to sustainable transport solutions has increased the focus on cycling as a mode of transport (Banister Citation2008; Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012). Replacing car journeys with cycling decreases pollution and is also positive for public health (Oja et al. Citation2011). However, societal objectives do not always correspond to the objectives of the individual. Studies show that cyclists do value the physical benefits gained from cycling (Heesch, Sahlqvist, and Garrard Citation2012), however, they also appreciate the bicycle as an efficient and fast means of transportation (Börjesson and Eliasson Citation2012). To make cycling attractive as part of a modal shift in transportation, it is certainly necessary to address the individual’s objectives and wishes when developing new infrastructure for cyclists.

At the same time there is a growing literature arguing that urban planning should not be limited to the physical development and provision of road infrastructure and services, but also integrate the planning, design and construction of streets into the social, economic and ecological brickwork of a community (Khayesi, Monheim, and Nebe Citation2010). Due to the present automobile regime (Urry Citation2004; Böhm et al. Citation2006), there is a need that infrastructure, as well as planning ideals and practices, make a shift towards a more sustainable paradigm (Banister Citation2008). Several studies highlight that current cycling infrastructure often fall short and does not meet the needs and desires of diverse groups of cyclists. (Pucher, Dill, and Handy Citation2010; Koglin and Rye Citation2014; Aldred and Dales Citation2017; Steinbach et al. Citation2011). The same applies in Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, despite these countries being recognised as good examples of advocating infrastructures promoting cycling (Emanuel Citation2012a; Koglin Citation2015). Generally, cycling is still not sufficiently prioritised, resulting in various conflicts in urban planning (Koglin Citation2013; Hull and O’Holleran Citation2014; Balkmar Citation2019; Gössling et al. Citation2016), as well as in actual traffic situations in which different modes of transport and users meet (Balkmar Citation2018; Aldred and Crosweller Citation2015; Freudendal-Pedersen Citation2015). In a design that prioritises motor vehicles, cyclists can be seen acting ‘off the script’, e.g. using spaces in unintended and ‘inappropriate’ ways, reflecting their experiences and capacities more accurately (Spinney Citation2008).

Route choice modelling indicates that cyclists are willing to make detours to avoid very stressful routes (Heinen, van Wee, and Maat Citation2010; Broach, Dill, and Gliebe Citation2012; Vedel, Jacobsen, and Skov-Petersen Citation2017; Sorton and Walsh Citation1994). Factors such as topography, the surroundings and the presence of traffic lights, have also been found to affect route choice (Broach, Dill, and Gliebe Citation2012). However, route choice models do not take into account those completely refraining from cycling for reasons related to perceived risk and discomfort, which tend to correlate with age, gender and income, where women and children as well as people on low income, report distress in relation to cycling (Heinen, van Wee, and Maat Citation2010; Thomsen Citation2005; Emond, Tang, and Handy Citation2009). Geller (Citation2006) assumed that around 60 % of the population of Portland belonged to the refraining category, and there are reasons to believe that this is a global phenomenon. This sentiment is substantiated, as several studies indicate, by motorists expressing aggression towards cyclists both in attitude and behaviour (Delbosc et al. Citation2019; Fruhen, Rossen, and Griffin Citation2019; Fruhen and Flin Citation2015; Balkmar Citation2014, Citation2018). Motorists often express negative attitudes by implying that cyclists are inferior to drivers in terms of morale, that they regard cyclists as notorious rule-breakers (Chaloux and El-Geneidy Citation2019; Fincham Citation2006), to the extent of describing their status as less than human beings (Delbosc et al. Citation2019). Given that studies from different countries and continents have shown this, one can assume that this is a widespread phenomenon.

Research into the rule breaking of cyclists, aiming to investigate the factors behind the violations, generally focuses on jumping red-lights (Pai and Jou Citation2014; Johnson et al. Citation2013, Citation2011; Wu, Yao, and Zhang Citation2012; Shaw et al. Citation2015). Evidence shows, however, that cyclists do not choose to behave ‘undesirably’ to maximise their benefit at any cost, rather they either believe they will gain speed or be safer. Without rule-breaking, cycling would become unsafe, too slow and less attractive (Marshall, Piatkowski, and Johnson Citation2017; Latham and Peter Citation2015; Aldred Citation2013; Spinney Citation2008; Lachapelle, Noland, and Von Hagen Citation2013).

In this study we explore riding on the pavement as another typical ‘undesirable’ behaviour, one which usually is against traffic regulations but nevertheless frequently can be observed in urban contexts. As the study will demonstrate, riding on the pavement can be seen as a practice reflecting the socio-material relations in which cycling is embedded. In New South Wales, Australia, 65 % of the respondents of a questionnaire reported riding on the pavement, with the main reported reason being poor infrastructure design (Shaw et al. Citation2015). Another Australian questionnaire study (Haworth and Schramm Citation2011) found that 33% of the cyclists used the pavement, even though two-thirds of them did so reluctantly. The average weekly distance ridden on the pavement was 4.5% of the total distance reported to be ridden by all cyclists, including those reporting not riding on the pavement. Rossetti, Saud, and Hurtubia (Citation2019) report counts from several North American cities, estimating that 24 % to 45 % of cyclists ride on the pavement.

So far, most studies investigating this phenomenon use questionnaires, relying on self-reporting, which does not allow for an in-depth understanding of the underlying reasons and meanings. Furthermore, an understanding of individual behaviour as embedded in a social and material context is also lacking. In line with the growing body of recent work within mobility studies, we propose that cycling analytically should be understood as a social practice (Larsen Citation2017; Latham and Peter Citation2015; Spotswood et al. Citation2015; Watson Citation2012) where the links between norms, competences and materiality (such as infrastructure) are highlighted and can explain when and why a subpractice of cycling, namely cycling on the pavement can occur.

In the study, we combine data from a questionnaire looking into cyclist preferences with respect to infrastructure design in Sweden, with data from two semi-controlled field studies, where cyclists’ observed behaviour was explored further through interviews and verbal protocol analysis. The goal of the study was to investigate the extent of cycling on the pavement in Sweden and to explore this phenomenon in depth using a social practice theory analytical approach. The study aims to contribute to the growing body of bicycle mobility literature that regards the wider socio-technical aspects of where the practice of cycling occurs, and thereby connects with literature that moves beyond simplistic individual explanations for unexpected and ‘undesirable’ behaviours. Below we will give a brief overview of literature, and present our stance on social practice theory and how it will be applied to pavement cycling.

Social practice theory in mobility research

A growing body of literature have highlighted how social practice theory can contribute to mobility research (Berg and Henriksson Citation2020; Sersli et al. Citation2020; Ravensbergen, Buliung, and Sersli Citation2020; Sopjani et al. Citation2020; Larsen Citation2017; Cass and Faulconbridge Citation2016a; Spotswood et al. Citation2015; Nettleton and Green Citation2014; Spurling et al. Citation2013). This approach has been successful in explaining the difficulties in steering towards more sustainable mobility, where mobility practices are connected to a variety of other practices and to norms about ‘the good life’, space-time-constraints, gendered relations and cycling identities. Moreover, social practice theory highlights how sustainable travelling (walking, cycling, public transport) is marginalised and closely related to the dominant mode of car driving (Scheurenbrand et al. Citation2018; Latham and Peter Citation2015). More spaces solely for cars and fewer bicycle lanes risks leading to less active transport, regardless of campaigns promoting sustainable living. Furthermore, as Larsen (Citation2017) highlights, due to a tendency within transportation research and practice to predominantly focus on physical design, social practice theory on the other hand, encourages analysis of the interplay between physical, social and cultural factors.

Theoretically, social practice theory implies a move away from the focus of individual choice as explanatory for behaviour. Rather than regarding behaviour as the cause of an external reality or mental processes, practices are explained as the combined outcome of the material context, norms and skills in which the performers interact. (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012; Reckwitz Citation2002; Warde Citation2005). Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012) define a practice as a successful configuration between different elements. The elements are identified as materials (objects, technology, infrastructure), competence (skills, embodied knowledge) and meaning (ideas, norms, ambitions, symbols). Seemingly isolated practices are connected to wider socio-technical networks, making some actions more likely than others. Practices are embedded in a wider network of practices that people perform to support everyday life, such as working or buying groceries. Practices can be divided into ‘subpractices’, basic activities that in ‘bundles’ constitute more comprehensive practices. As an example, to become the practice of urban cycling, pedaling a bicycle must ‘bundle’ with various subpractices such as braking and parking (Scheurenbrand et al. Citation2018, building on Schatzki (Citation2012)). Accordingly, a researcher should typically not exclusively examine a single practice, but also ‘capture relationships among “bundles” of practices’ (Scheurenbrand et al. Citation2018).

A few studies have analysed bicycle practices, and what elements the practice of urban cycling comprise. According to Larsen (Citation2017) the materials include the bicycle and biking equipment such as bicycle parts, locks, helmets, but also the road design and racks available for parking. Larsen also highlights how weather, topography and ‘sweating bodies’ (Citation2017:878) are important material aspects. With regard to competence, knowledge of the local traffic system is important, as is steering and balancing skills. Spotswood et al. (Citation2015) also points out that fitness is an important skill, and that perceived lack of fitness prevents people from cycling. Both Spotswood et. al. and Larsen denote that there are many contradictory meanings ascribed to cycling, while cycling can be viewed as unsafe and dangerous it can also be a source of freedom and wellbeing.

Related to these studies, a study of urban cycling in Las Palmas highlights some interesting points about practices (Scheurenbrand et al. Citation2018). Through ethnographic fieldwork they demonstrate that cycling practices are shaped by habits and routines rather than individual identities and preferences. To their account, urban cyclists make sense of moving in urban surroundings through engagement in cycling practices.

Latham and Wood (Citation2015) understand urban cycling in London as a site for practices and materials inserted into the existing infrastructural space of the city’s roads. The idea of ‘obduracy’ is vital for their analysis. Applying Hommels (Citation2005) definition of obduracy, they describe obduracy as the ‘inertia and resistance that existing socio-material configuration exhibits in the face of efforts to alter them’ (2015:304). Modern streetscapes, Latham and Wood argue, are configured to meet demands of smooth and rapid movement of motorised traffic and to keep people on foot safe, providing urban cyclists with an infrastructure they are struggling to find space to move within. Their ethnographic case study of London cyclists visualises the difficulties cyclists experience in simultaneously following the flow of traffic, staying in motion as well as adhering to rules and norms. To break, mend or bend rules can therefore be understood as developing practices that make cyclists safer and more efficient road users, where the existing rules are unfair or unreasonable for cyclists. Latham and Wood conclude that rule breaking can be regarded as an indicator of infrastructural tension or pressure, rather than moral ambiguity. For urban cyclists, infrastructural encounters are barriers or difficulties that must be worked around or solved.

In this paper, building on previous work on urban cycling from a social practice perspective, we view pavement cycling as an element, a subpractice, of urban cycling. To understand this subpractice, sense must be made of the practice of urban cycling. This will be done by emphasising how meaning, materials and competence play out in our empirical material.

Materials and methods

The data material used in this study stems from three different studies, two of which were field studies employing a semi-controlled approach (Kircher et al. Citation2017), and one a questionnaire study with web-based data collection. For each study, the methodological aspects relevant to this work are outlined.

Setting for the field studies

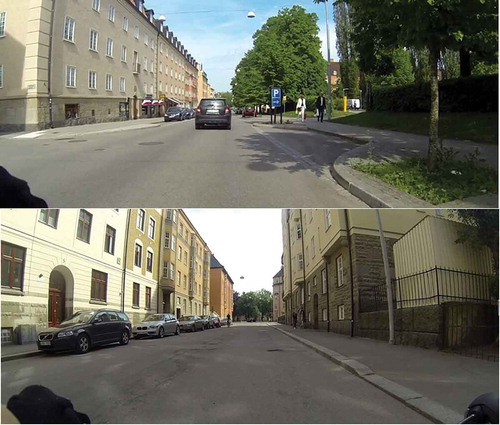

Both field studies were conducted in the centre of Linköping, a middle-sized municipality in eastern Sweden. Traffic volumes are generally low to medium, cyclists and pedestrians are common, and overall traffic can be characterised as calm. While there is a certain degree of cyclist infrastructure, the design is not consistent. Dedicated cycle paths, cycle lanes, shared cycle/pedestrian paths and cycling in mixed traffic occur and right-of-way rules are not readily comprehensible from the infrastructural layout (Kircher and Ahlström Citation2020). For the analyses herein, a stretch with mixed traffic was chosen ( and contain screenshots from Field Study 1. In Field Study 2 the cyclists rode in the opposite direction).

Figure 1. Screenshots from a handle-bar mounted, forward-facing camera in Field Study 1, where the cyclist rode on the street

Figure 2. Screenshots from a handle-bar mounted forward-facing camera in Field Study 1, where the cyclist rode on the pavement

The cyclist population in Linköping is heterogeneous both with respect to the bicycles ridden and the self-reported and observed riding style (see also Kircher et al. (Citation2018)). In Sweden, cycling on the pavement is prohibited. However, a recent change (2014) in policy has now legalised cycling on the pavement for children up to the age of eight years if an adjacent cycle path is not available. The risk of incurring a fine when cycling on the pavement in Linköping is though virtually non-existent.

Field study 1

The original purpose of the study was to investigate the interaction with smartphones in traffic for different groups of cyclists (Nygårdhs et al. Citation2018). The 41 participants were recruited via a web-based questionnaire, which was answered by approximately 500 respondents. They were selected and categorised into four groups, three of which were based on the respondents’ self-reported cycling speed in relation to others, the remaining group was for e-bicycles, regardless of reported speed.

Each participant rode a pre-determined route, twice in a row, for a total of approximately 6 km. The participants used their own bicycles, which had been equipped with one forward-facing camera and one camera facing the participant. Each participant also wore a head-mounted eye tracker. On the ride, the participants were followed by an experimental leader on a bicycle, similarly equipped with a forward-facing camera. The participants were asked to behave as if they did not partake in a study, with respect to speed choice, smart phone interaction and placement in the infrastructure along the route. The section of interest in this study was a 685 m long road stretch consisting of a street and a pavement, without any dedicated cycling facilities.

In order to capture direct experiences along the route, the participants were asked to ‘think aloud’ (Ericsson and Simon Citation1980) while cycling. This meant commenting out loud on anything relating to how they experienced the ride, for example what was on their mind here and now, different choices or strategies they used, how they felt, etc. The think aloud talk was recorded via the cameras mounted on the participants’ handlebars, and later transcribed verbatim.

After completing the cycling route, the participants were interviewed about any special occurrences along the route, at the discretion of the following experimental leader. Cycling on the pavement may have been one such occurrence. Notes were taken by the experimental leader during the interviews.

Field study 2

The original purpose of this study was to investigate attention allocation for car drivers and cyclists, depending on whether they were used to cycling or driving, and whether they, as cyclists, were confident or not about riding in mixed traffic. Again, using a recruitment questionnaire, participants were categorised into ‘drivers’ and ‘cyclists’ who considered themselves either ‘confident’ or ‘unconfident’. This study comprised 23 participants and was also situated in Linköping. Each participant both drove a car and rode a bicycle along a 5 km long route. The mixed-traffic stretch from Field Study 1 was also included in this study, this time in the opposite direction. The cycling condition applied the same set-up and instructions as in Field Study 1. This time, however, the participants did not perform any additional tasks. Also, they were not asked to think aloud while cycling/driving, instead they were asked to do so afterwards while watching a film of their ride/drive. In addition, they were interviewed with regard to how they viewed the two transport modes with respect to safety, comfort, efficiency, ease of use, etc. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim ().

Questionnaire study

As part of a project investigating infrastructural aspects and their relation to accidents between cyclists and motorised traffic, 2,492 respondents answered an on-line questionnaire. The respondents were recruited via a panel from Swedish urban areas including Stockholm (811 respondents), Gothenburg (403), Malmö (454) and Lund (230), and the remaining 594 were from towns with 20,000 to 50,000 inhabitants in the southern third of Sweden. Following a few demographic and background questions, including how confident they felt about cycling in mixed traffic, the respondents were asked to indicate their preferred route for turning left when riding a bicycle, depending on the design of the infrastructure. For eight different intersection designs, route options included riding on the street, either using the centre of the intersection or remaining at the right edge, using cyclist facilities (if present), using pedestrian facilities, a mix of options, or, for one design, using a tunnel. The participants indicated whether they typically dismounted and walked the selected route, and how efficient and how safe the chosen route felt.

Data sources for cycling on the pavement

For the two field studies, cycling on the pavement was determined via video analysis of the camera mounted on the experimental leader’s bicycle. For the questionnaire study, the indicated route choice for each intersection was analysed.

The data used for the qualitative analysis came from three different sources, of which two were from Field Study 1 and one from Field Study 2. The first source (Field Study 1) were the spontaneous expressions the participants made while thinking aloud on the route segment where cycling on the pavement was possible. All ‘think aloud’ expressions were listened to, and any statements related to cycling on the pavement were transcribed. In total, data from 14 ‘think aloud’ occasions were included. The second data source (Field Study 1) consisted of notes made during the interview after the trial made by the experimental leader following the participants. In this interview, the experimental leader asked about situations they had found to be of interest to discuss. Riding on the pavement was one of the topics that participants may have been asked about. Six such interviews were included in the analysis. The third data source (Field Study 2) comprised of interviews conducted with the participants after the trial. The interviews were semi-structured and performed following an interview guide, focusing on differences and similarities regarding aspects of being a cyclist versus a car driver in an urban environment. The interview segments that concerned cycling on the pavement, comprised this third data source.

Analysis

The data analysis process was inductive in its character (e.g. Patton Citation2002) and consisted of three central steps. First, all data material was looked through several times to become familiar with it. Thereafter, the data was coded in a content analysis-based approach, where statements were assigned different conceptual codes based on content. In the last step the codes were grouped into different categories, and categories were created and assigned names based on the condensed meaning of the conceptual codes. The categories created in this step are the ones appearing in the results section below. In the further analysis, we identified and used the different elements constituting a social practice as defined by Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012) as analytical categories. Hence, we explored what materials, competences and meanings that constitute cycling on the pavement in our empirical material to identify different configurations of the social practice of pavement cycling.

Results

From Field Study 1, the observed frequency of cycling on the pavement and its effect on efficiency have been published elsewhere (Kircher et al. Citation2018). It was shown that the relationship between efficiency and pavement usage was complex, depending on the design of the infrastructure and cyclist group. The data presented for Field Study 1 in represent a summary of those results, extended with additional information and the corresponding results of Field Study 2.

Table 1. Pavement riding propensity for different cyclist groups in Field Studies 1 and 2, on the 685 m long road stretch with mixed traffic. (part. = participant, conf. = confident, unconf. = unconfident; total time is presented as mean and standard deviation.)

In total, more than 30% of the cyclists taking part in the studies used the pavement for at least a part of the mixed traffic stretch, although the propensity to use the pavement differed between the self-selected groups (). This is also true for the percentage of time during which the pavement was used. Slower cyclists were more prone to use the pavement than faster cyclists, and they used the pavement during a longer percentage of time. However, the behavioural data from Field Study 2 indicate that cyclists who report feeling unconfident in mixed traffic were not more likely to ride on the pavement than cyclists who feel confident in mixed traffic. Rather, a tendency to the opposite could be observed, which may reflect cautious behaviour in general in the sense that people who are uncomfortable with cycling in mixed traffic, might also feel obliged to adhere to the stipulated rules, or do not want to be a nuisance to pedestrians.

Overall, the figures for observed behaviour and for self-reported behaviour are in the same ballpark. As indicated in , 30% of the questionnaire respondents reported that they exclusively used pedestrian facilities, in non-signalled intersections with mixed traffic, when turning left, while an additional 25% indicated that they made partial use of pedestrian facilities, typically by choosing the zebra crossing at the actual intersection. In other types of intersections, somewhat fewer cyclists reported using the pedestrian facilities, although it is still a common occurrence, and even a dedicated cycle path does not prevent cyclists from using the pavement or the road. Thus, it is evident that further factors than the mere presence of cycling infrastructure influences a cyclist’s choice of location. The self-reported confidence in riding in mixed traffic was only marginally related to the choice of avoiding mixed traffic as reported in the questionnaire (Spearman’s rho = 0.28; p <.01), indicating that further reasons are involved.

Table 2. Distribution of indicated route choice depending on the infrastructural design in percentage. The figures do not add up to 100%, as respondents had the option of indicating ‘other’ when marking their route choice

Results from the qualitative analysis – three main configurations of cycling on the pavement

In the analysis, three main configurations for cycling on the pavement were identified, namely; avoiding the space of the car, increasing smoothness of cycling and unclear infrastructure design. A configuration constitutes a specific arrangement of meaning, material and competence.

Avoiding the space of the car

The most pronounced configuration of the practice of cycling on the pavement was connected to the purpose of avoiding riding among motorised traffic. To share the space and cycle among motorised traffic were expressed by participants as something they wanted to avoid. Below, one participant illustrates this perception in the follow-up interview:

Cycles on the pavement if there are not too many pedestrians there. Wants to get away from [motorised] traffic. (Notes from interview, Field Study 1)

If the pavement is not too crowded with pedestrians, cycling on the pavement was considered a better option than among motorised traffic. Reasons for avoiding cycling among motorised traffic were related to either a perception of risk, fear or discomfort, or that the space not actually being meant for them as cyclists. This can be interpreted as a meaning ascribed to cycling that it is not safe to cycle among cars, as exemplified by the participant below. He expresses how he does not feel safe cycling in the same space as motorised vehicles:

If I am out with a bicycle in traffic among the [motorised] vehicles it doesn’t feel safe. I don’t feel safe in that space. You are very unprotected as a cyclist. Even if I see the cars I’m not sure that they see me. I’d rather have separate lanes for cyclists and [motorised] vehicles. (Interview, Field study 2)

In the shared space he explains how he perceives the environment to be unsafe and that he as a cyclist is unprotected alongside the cars. He is also critical that plans have not been made for separating bicycles and cars. The uncertainty whether he is seen by the drivers of cars is something that worries him. This indicates that the meaning is strongly associated with the material aspects of cycling in traffic. The lack of separated lanes leads to the interpretation of the road space as unsafe. Choosing to cycle on the pavement emerges as a measure to avoid sharing space with motor vehicles:

I really wouldn’t dare biking along the road, it is a street crowded with traffic. I go on the pavement. (Think aloud, Field Study 1).

Rode on the pavement often. Expressed not feeling comfortable with sharing space with cars. (Notes from interview, Field Study 1)

The participants above illustrate how they choose to ride on the pavement to avoid the road and motor vehicles, thereby avoiding a feeling of risk and vulnerability in the shared space.

Even though cycling on the pavement was an option for some who were uncomfortable sharing space with motorised traffic, others would not consider that appropriate behaviour despite feeling as uncomfortable:

I avoid biking on the pavement as far as possible because I really don’t like people biking on the pavement. Bicycles don’t belong on the pavement. (Interview, Field Study 2)

Instead, the mode choice of transport can be influenced from the start when an environment is perceived unsafe for cycling, because it would demand uncomfortable interaction with motorised traffic. The same participant explains how safety affects his choice of transport mode, taking the car even though the distance is short, and driving being more time consuming:

Yes, because in terms of distance and time there isn’t really a saving. It’s a safety issue. I’m safer in the car, I am more protected in the car. Biking in town [where cycle lanes are limited] doesn’t feel very good really. (Interview, Field Study 2)

The quote also illustrates that the car, in relation to the bicycle, is perceived as offering a more protected environment where safety is higher.

Cyclists experiencing risk or discomfort while sharing the space with motorised traffic, or having the notion that the road is not actually intended for cyclists, may thus ride on the pavement as a way of alleviating the risk or avoiding a non-granted space. Here, meaning (feeling unsafe) is closely related to material aspects, the lack of infrastructure that supports safe cycling.

Increasing smoothness of cycling

Another configuration of the practice of riding on the pavement is related to the perceived smoothness of cycling in the urban environment. The term smoothness should here be understood as being closely linked to saving time, keeping up speed, conserving energy and avoiding obstacles. Riding on the pavement is herein defined as being smoother than going on the road in the shared space. One participant illustrates this as follows:

Now I go up here [on the pavement]. As matter of fact it’s a pavement but it is smoother to go here [than on the road]. (Think aloud, Field Study 1)

This participant expresses an awareness of choosing to go up on the pavement, but also an understanding that this area is not really meant for her as a cyclist. However, because she perceives it as smoother to ride there, than the alternative to ride on the road, she actively chooses that option. When certain circumstances are defined as disturbing in mixed traffic, i.e., a lot of traffic, poor infrastructure design, road construction or certain traffic regulations, riding on the pavement from a cyclist’s perspective can be one way to avoid such disturbances. As noted by Spinney (Citation2008), cycling is a self-propelled mode of transport and constitutes a natural inclination to conserve energy and keeping speed. To use the pavement to increase smoothness by keeping a higher speed and/or reduce energy expenditure could therefore be seen as following a sensible path.

Despite this strategy being applied, a perception that cycling on the pavement representing an undesirable cycling behaviour was also apparent:

The participant expressed the view that cyclists should not ride on the pavement, but regard that as a natural consequence given how the infrastructure is planned. (Notes from interview, Field Study 1)

While disapproving of the act of cycling on the pavement, the participant simultaneously articulates an understanding that such behaviour can occur if the infrastructure design is mismatched with the needs of cyclists. This is an example of meaning and material not being as closely integrated, as in the case of cyclists who expressed notions of fear and unsafety. Even if cyclists express awareness that they should not use the pavement for cycling, they do so because it is easier for them. Thus, ignoring the rules can be interpreted as regulations prohibiting pavement cycling not thought of as a strong dictate. Rather, pavement cycling is interpreted as such a common practice, that is thought of as a possibility, embedded within the practice of urban cycling.

Unclear infrastructure design

Cycling on the pavement was also found to be the outcome of perceiving the infrastructure design as ambiguous. When the design is perceived as unclear, confusion arises which results in various behaviours. This was articulated in the follow-up interviews and could also be observed in the video footage. Below, in a think aloud session, one participant articulates this uncertainty and also reasons strategically about where to actually ride:

Here one could think it’s a bicycle lane, maybe it is? But if you don’t know you choose to go where it feels safest or smoothest. (Think aloud, Field Study 1)

The quote here clearly illustrates a feeling of confusion about where to ride. He reasons that being uncertain, he seeks to find the path he believes will offer him the safest or smoothest ride. Later, the participant realises that the path he has chosen is a pavement, and states that if more cars had been present, he would have chosen to ride on the pavement anyway in an attempt to avoid the traffic.

In relation to social practice theory, uncertainty as to which route to take can be interpreted as an outcome of the element ‘competence’. The performer may be regarded as lacking the competence to interpret the environment correctly. However, the infrastructure, the material, can in fact be difficult to interpret. Consequently, if the infrastructure appears unclear to the cyclist, the choice of route will be determined by a combination of how the cyclist perceives and evaluates the infrastructure and the surroundings. Rather than lack of competence, riding on the pavement would therefore be one possible result of such evaluation. This is also in line with how Latham and Peter (Citation2015) understands the social practice of rule-breaking in urban cycling, where breaking or bending rules is a way for cyclist to make urban cycling safer or more efficient.

Discussion

Cycling on the pavement is a practice common among cyclists. The analysis identified three main configurations of this practice, namely: avoiding the space of the car, increasing smoothness of cycling and unclear infrastructure design. The practice of pavement cycling was found to be configured differently in relation to the different rationales.

Avoiding the space of the car was the most pronounced reason for cycling on the pavement in our study. Cycling among motorised vehicles was related to feelings of fear or discomfort, thus choosing the pavement instead of the road was a strategy adopted for managing this perceived risk. Riding on the pavement was therefore connected to a local context and an aspiration for a mobility without risking accidents and injuries. One UK study (Aldred Citation2013) also found similar reasons in relation to riding on the pavement, where cyclists revealed that they chose to cycle on the pavement because they found the roads intimidating and dangerous. Despite police efforts including penalties in limiting cycling on the pavement, cyclists claimed they would continue to do so as they believed police measures illegitimate. A relevant question that needs answering is why do cyclists perceive the mixed-traffic road space intimidating or unsafe?

We have highlighted how cyclists in general do not strictly adhere to the prohibition of pavement cycling. Since the empirical material indicates that pavement cycling is continuously occurring, we would argue that pavement cycling is a normal and even rational subpractice of urban cycling, which is characterised by riding in mixed traffic and poor infrastructure. The configurations of meaning, material and competence that constitutes pavement cycling above highlight a prerequisite for urban cycling, namely the interaction with motorised vehicles. This type of interaction becomes problematic due to the innate skewness in material power between the different transport modes. Cars possess obvious material power over bicycles in terms of size, weight and protection (Dery Citation2006; Balkmar Citation2014). While on the one hand being beneficial to their users, cars on the other hand create a physical, psychological and social chasm between modes of transport (Nixon Citation2014). In the car–bicycle relation, cars thus pose potential danger to cyclists, which puts cyclists into an inferior and vulnerable position.

Another issue relates to the construction and design of infrastructure and what transport mode the space primarily is intended for. Cyclists have previously been depicted as marginalised road users, with little or no usage rights in car-oriented cultures (Koglin and Rye Citation2014; Prati, Marín Puchades, and Pietrantoni Citation2017; Emanuel Citation2012b). Streets planned, designed and constructed primarily targeting motorised transport, further communicates whose right to occupy the space is most legitimate, and thereby also who does not have equal rights to the space. In a car-oriented infrastructure, the cyclists’ position is thus inferior, leading to a necessary need to negotiate their right to occupy the space. This is however a problematic negotiation. Cyclists can, from a car-driving perspective, be regarded as barriers to high-speed and smooth travelling which constitute the innate opportunity of car travel (Urry Citation2004). Cyclists in the road space represent disruptions in flow that must be dealt with and tend to generate feelings of disharmony and irritation for car drivers wanting to get through. It is in this interaction and negotiation of right to the space that fear and discomfort can arise among cyclists. Riding on the pavement can thus be understood partly as an outcome of measures taken to avoid sharing the space and having to interact with motorised traffic, thereby avoiding feelings of fear or discomfort. With reference to Spinney (Citation2008), cycling on the pavement is part of an effort to create a space in which cyclists feel less vulnerable.

The cyclists do not appear to particularly take into consideration the reduction in safety that may be experienced by pedestrians as a result of them riding on the pavement. This can also be viewed as a reflection of the power struggle within a motorised regime, where conflicts between different groups are reinforced by the material surroundings (Gössling et al. Citation2016; Koglin Citation2013; Balkmar Citation2019).

In the second configuration of cycling on the pavement, a wish to increase the smoothness of the ride was in focus for the cyclists. However, participants of the study did not express any specific motivation for why they found riding on the pavement smoother than riding in the mixed space, only that it was actually smoother per se. However, as argued above by Spinney (Citation2008) for instance, cycling is a human-powered mode of transportation, where it is natural for cyclists to both conserve time and energy thus seeking the smoothest route. In an environment planned for motorised movement, human expenditure is not often considered. If circumstances experienced as energy-consuming in the shared space, for instance excess traffic, poor design, road construction or traffic regulations not suited for cyclists, riding on the pavement is one way to avoid such circumstances. In choosing the pavement, the efficiency and smoothness can be enhanced or kept at the best possible level. Again, we see that the element of meaning in the practice of pavement cycling is not related to traffic regulations. It is rather demonstrated here by practice, that it is more important to have a smoother ride than to respect traffic regulations. This correlates with cyclists’ demand for decent cycling infrastructure. This was for instance demonstrated by Ghanayim and Bekhor (Citation2018) who found that cyclists are willing to cycle 57 % longer than the shortest route to avoid highly trafficked roads.

The third configuration of the practice of cycling on the pavement occurred when the infrastructure appeared ambiguous or unclear to the cyclist. Stemming from a feeling of uncertainty of where to cycle, choosing the pavement was the outcome of experiencing the pavement as either the appropriate path, in accordance with the perceived intention of the design, or the safest or smoothest option. In this study, it was the (self-reported) slowest cyclists that used the pavement the most. This may indicate that they lack the experience of cycling in mixed traffic that faster cyclists have. However, none of the interviewed cyclists speak of themselves as lacking cycling competence, neither in broad terms nor in relation to cycling in mixed spaces. Rather this can be interpreted as managing an unclear infrastructure being part of the competence cyclists require to practice urban cycling. When it is unclear where to cycle, cyclists choose routes, including pavements, where they can cycle in a safe and efficient manner.

Methodological reflections

In the field studies, the cyclists were asked to behave as if cycling by themselves for reasons of transportation. Therefore, our findings should not be transferred to cycling for other reasons, such as training, neither for cycling in groups or with children.

The qualitative part of this study raises some methodological concerns that should be addressed. These relate to how valid the results are and to what other contexts the results can be transferable to (Patton Citation2002; Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). One strength of the current study is that it uses triangulation of different data sources (think aloud and interviews) and that it combines data from different studies, which according to Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) is one technique of enhancing a study’s credibility. Another strength being that the empirical data stemming from thinking aloud gives access to a very direct experience as it is generated when being ‘in action’. However, the data available concerning cycling on the pavement in this study was limited as none of the studies included were initially designed for research on cycling on the pavement as such. It is therefore unclear if theoretical saturation was reached, meaning that no novel information would emerge with additional data collection, which is the ideal when making qualitative inquiry (Patton Citation2002). Hence, we can therefore not say that no other configurations for cycling on the pavement exist than those found in this study. Nevertheless, the data available were consistent and it is our belief that they are comprehensive and stringent enough for the analysis and conclusions that have been made in this study.

Regarding transferability, the hypothesis suggested by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) is that the results of one study are transferable to contexts which are similar to the original study, i.e., the results found in our study should be transferable to contexts which are similar in terms of infrastructure and culture to a Swedish middle-sized city. However, it is very likely that its transferability also stretches beyond this context, as similar conditions exist for cyclists in many places.

Conclusion

The main conclusion from the current study is that riding on the pavement is a persistent and recurring element within the practice of urban cycling. We argue that this practice should be viewed as a sensible outcome as seen from the cyclists’ perspective. The practice of riding on the pavement is partly connected to the interpretation of urban traffic as unsafe. To manage personal safety is a competence that urban cyclists must master to feel safe, and to reach destinations in due time. Riding on the pavement represents this part of such management. Policies, urban planning and infrastructure design not harmonising with cyclists’ demands for safe and smooth infrastructure are therefore likely to continue to generate unwanted behaviour and conflicts to some extent. Moreover, if a physical environment is perceived as dangerous, it will also prevent certain groups from considering cycling as a mode of transport (Pucher and Dijkstra Citation2003; Jacobsen, Racioppi, and Rutter Citation2009) which was also illustrated by the present study.

If there is a serious wish, in the strive for more sustainable transport, to increase cycling, making it a safe and comfortable mode of transport, planning and design of urban space must to a higher degree take into account the perspectives and needs of cyclists.

This study aims to build on a tradition that acknowledges the necessity of viewing the transport system as consisting of interplays between material aspects, users, norms, and meanings. Hereby, the study also aims to contribute to the growing body of literature that utilises a social practice theory perspective on mobility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldred, R. 2013. “Incompetent or Too Competent? Negotiating Everyday Cycling Identities in a Motor Dominated Society.” Mobilities 8 (2): 252–271. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.696342.

- Aldred, R., and J. Dales. 2017. “Diversifying and Normalising Cycling in London, UK: An Exploratory Study on the Influence of Infrastructure.” Journal of Transport and Health 4: 348–362. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2016.11.002.

- Aldred, R., and S. Crosweller. 2015. “Investigating the Rates and Impacts of near Misses and Related Incidents among UK Cyclists.” Journal of Transport & Health 2 (3): 379–393. doi:10.1016/J.JTH.2015.05.006.

- Anders, E. K., and H. A. Simon. 1980. “Verbal Reports as Data.” Psychological Review 87 (3): 215–251. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.215.

- Balkmar, D. 2014. “Våld I Trafiken: Om Cyklisters Utsatthet För Kränkningar, Hot Och Våld I Massbilismens Tidevarv.” Tidskrift För Genusvetenskap 35 (2–3): 31–54.

- Balkmar, D. 2018. “Violent Mobilities: Men, Masculinities and Road Conflicts in Sweden.” Mobilities 13 (5): 717–732. doi:10.1080/17450101.2018.1500096.

- Balkmar, D. 2019. „Towards an Intersectional Approach to Men, Masculinities and (Un) sustainable Mobility: The Case of Cycling and Modal Conflicts.„ In Integrating Gender into Transport Planning, 199–220. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Banister, D. 2008. “The Sustainable Mobility Paradigm.” Transport Policy 15 (2): 73–80. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.10.005.

- Berg, J., and M. Henriksson. 2020. “In Search of the ‘Good Life’: Understanding Online Grocery Shopping and Everyday Mobility as Social Practices.” Journal of Transport Geography 83. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102633.

- Böhm, S., C. Land, C. Jones, and M. Paterson. 2006. Against Automobility. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing .

- Börjesson, M., and J. Eliasson. 2012. “The Value of Time and External Benefits in Bicycle Appraisal.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 46 (4): 673–683. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2012.01.006.

- Broach, J., J. Dill, and J. Gliebe. 2012. “Where Do Cyclists Ride? A Route Choice Model Developed with Revealed Preference GPS Data.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 46 (10): 1730–1740. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2012.07.005.

- Cass, N., and J. Faulconbridge. 2016a. “Commuting Practices: New Insights into Modal Shift from Theories of Social Practice.” Transport Policy 45: 1–14. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.08.002.

- Chaloux, N., and A. El-Geneidy. 2019. “Rules of the Road: Compliance and Defiance among the Different Types of Cyclists.” Transportation Research Record. doi:10.1177/0361198119844965.

- Delbosc, A., F. Naznin, N. Haslam, and N. Haworth. 2019. “Dehumanization of Cyclists Predicts Self-Reported Aggressive Behaviour toward Them: A Pilot Study.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2019.03.005.

- Dery, M. 2006. “‘Always Crashing in the Same Car’: A Head-on Collision with the Technosphere.” Sociological Review 54 (SUPPL. 1): 223–239. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00646.x.

- Emanuel, M. 2012a. “Constructing the Cyclist Ideology and Representations in Urban Traffic Planning in Stockholm, 1930–70.” The Journal of Transport History 33 (1): 67–91. doi:10.7227/tjth.33.1.6.

- Emanuel, M. 2012b. Trafikslag På Undantag. Cykeltrafiken I Stockholm 1930-1980. Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag.

- Emond, C. R., W. Tang, and S. L. Handy. 2009. “Explaining Gender Difference in Bicycling Behavior.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2125 (1): 16–25. SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA. doi10.3141/2125-03.

- Fincham, B. 2006. “Bicycle Messengers and the Road to Freedom.” Sociological Review. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00645.x.

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M. 2015. “Cyclists as Part of the City’s Organism: Structural Stories on Cycling in Copenhagen.” City and Society 27 (1): 30–50. doi:10.1111/ciso.12051.

- Fruhen, L. S., I. Rossen, and M. A. Griffin. 2019. “The Factors Shaping Car Drivers’ Attitudes Towards Cyclist and Their Impact on Behaviour.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 123: 235–242. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2018.11.006.

- Fruhen, L. S., and R. Flin. 2015. “Car Driver Attitudes, Perceptions of Social Norms and Aggressive Driving Behaviour Towards Cyclists.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 83: 162–170. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2015.07.003.

- Geller, R. 2006. Four Types of Cyclists. Portland, Oregon: PortlandOnline.

- Ghanayim, M., and S. Bekhor. 2018. “Modelling Bicycle Route Choice Using Data from a GPS-Assisted Household Survey.” European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research18 (2): 158–77. https://doi.org/10.18757/ejtir.2018.18.2.3228

- Gössling, S., M. Schröder, P. Späth, and T. Freytag. 2016. “Urban Space Distribution and Sustainable Transport.” Transport Reviews 36 (5): 659–679. doi:10.1080/01441647.2016.1147101.

- Haworth, N., and A. Schramm. 2011. “Adults Cycling on the Footpath: What Do the Data Show?,” 10p. http://acrs.org.au/publications/conference-papers/database/%0Ahttps://trid.trb.org/view/1131436.

- Heesch, K. C., S. Sahlqvist, and J. Garrard. 2012. “Gender Differences in Recreational and Transport Cycling: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Comparison of Cycling Patterns, Motivators, and Constraints.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-106.

- Heinen, E., B. van Wee, and K. Maat. 2010. “Commuting by Bicycle: An Overview of the Literature.” Transport Reviews 30 (1): 59–96. doi:10.1080/01441640903187001.

- Hommels, A. 2005. “Studying Obduracy in the City: Toward a Productive Fusion between Technology Studies and Urban Studies.” Science Technology and Human Values. doi:10.1177/0162243904271759.

- Hull, A., and C. O’Holleran. 2014. “Bicycle Infrastructure: Can Good Design Encourage Cycling?” Urban, Planning and Transport Research 2 (1): 369–406. doi:10.1080/21650020.2014.955210.

- Jacobsen, P. L., F. Racioppi, and H. Rutter. 2009. “Who Owns the Roads? How Motorised Traffic Discourages Walking and Bicycling.” Injury Prevention 15 (6): 369–373. doi:10.1136/ip.2009.022566.

- Johnson, M., J. Charlton, J. Oxley, and S. Newstead. 2013. “Why Do Cyclists Infringe at Red Lights? an Investigation of Australian Cyclists’ Reasons for Red Light Infringement.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 50: 840–847. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.07.008.

- Johnson, M., S. Newstead, J. Charlton, and J. Oxley. 2011. “Riding through Red Lights: The Rate, Characteristics and Risk Factors of Non-Compliant Urban Commuter Cyclists.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 43 (1): 323–328. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.08.030.

- Khayesi, M., H. Monheim, and J. M. Nebe. 2010. “Negotiating ‘Streets for All’ in Urban Transport Planning: The Case for Pedestrians, Cyclists and Street Vendors in Nairobi, Kenya.” Antipode 42 (1): 103–126. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00733.x.

- Kircher, K., and C. Ahlström. 2020. “Attentional Requirements on Cyclists and Drivers in Urban Intersections.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 68: 105–117. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2019.12.008.

- Kircher, K., J. Ihlström, S. Nygårdhs, and C. Ahlstrom. 2018. “Cyclist Efficiency and Its Dependence on Infrastructure and Usual Speed.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 54: 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2018.02.002.

- Kircher, K., O. Eriksson, Å. Forsman, A. Vadeby, and C. Ahlstrom. 2017. “Design and Analysis of Semi-Controlled Studies.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 46: 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2016.06.016.

- Koglin, T. 2013. Vélomobility-A Critical Analysis of Planning and Space. Bulletin/Lund University, Lund Institute of Technology. http://lup.lub.lu.se/record/3972511.

- Koglin, T. 2015. “Organisation Does Matter - Planning for Cycling in Stockholm and Copenhagen.” Transport Policy 39: 55–62. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.02.003.

- Koglin, T., and T. Rye. 2014. “The Marginalisation of Bicycling in Modernist Urban Transport Planning.” Journal of Transport and Health 1 (4): 214–222. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.006.

- Lachapelle, U., R. B. Noland, and L. A. Von Hagen. 2013. “Teaching Children about Bicycle Safety: An Evaluation of the New Jersey Bike School Program.” Accident Analysis & Prevention 52: 237–249. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.09.015.

- Larsen, J. 2017. “The Making of a Pro-Cycling City: Social Practices and Bicycle Mobilities.” Environment and Planning A 49 (4): 876–892. doi:10.1177/0308518X16682732.

- Latham, A., and R. H. Peter. 2015. “Inhabiting Infrastructure: Exploring the Interactional Spaces of Urban Cycling.” Environment and Planning A 47 (2): 300–319. doi:10.1068/a140049p.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Vol. 75. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Marshall, W. E., D. Piatkowski, and A. Johnson. 2017. “Scofflaw Bicycling: Illegal but Rational.” Journal of Transport and Land Use. doi:10.5198/jtlu.2017.871.

- Nettleton, S., and J. Green. 2014. “Thinking about Changing Mobility Practices: How a Social Practice Approach Can Help.” Sociology of Health and Illness 36 (2): 239–251. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12101.

- Nixon, D. V. 2014. “Speeding Capsules of Alienation? Social (Dis)connections Amongst Drivers, Cyclists and Pedestrians in Vancouver, BC.” Geoforum 54: 91–102. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.04.002.

- Nygårdhs, S., C. Ahlström, J. Ihlström, and K. Kircher. 2018. “Bicyclists’ Adaptation Strategies When Interacting with Text Messages in Urban Environments.” Cognition, Technology and Work 20 (3): 377–388. doi:10.1007/s10111-018-0478-y.

- Oja, P., S. Titze, A. Bauman, B. de Geus, P. Krenn, B. Reger-Nash, and T. Kohlberger. 2011. “Health Benefits of Cycling: A Systematic Review.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 21 (4): 496–509. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01299.x.

- Pai, C. W., and R. C. Jou. 2014. “Cyclists’ Red-Light Running Behaviours: An Examination of Risk-Taking, Opportunistic, and Law-Obeying Behaviours.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 62: 191–198. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.09.008.

- Patton, M. P. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Sage. Vol. 3rd vols. London: Sage. doi:10.2307/330063.

- Prati, G., V. M. Puchades, and L. Pietrantoni. 2017. “Cyclists as a Minority Group?” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 47 (May): 34–41. doi:10.1016/J.TRF.2017.04.008.

- Pucher, J., J. Dill, and S. Handy. 2010. “Infrastructure, Programs, and Policies to Increase Bicycling: An International Review.” Preventive Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.028.

- Pucher, J., and L. Dijkstra. 2003. “Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling to Improve Public Health: Lessons from the Netherlands and Germany.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (9): 1509–1516. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12948971%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1448001.

- Ravensbergen, L., R. Buliung, and S. Sersli. 2020. “Vélomobilities of Care in a Low-Cycling City.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 134: 336–347. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2020.02.014.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002. “Toward A Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Rossetti, T., V. Saud, and R. Hurtubia. 2019. “I Want to Ride It Where I Like: Measuring Design Preferences in Cycling Infrastructure.” Transportation 46 (3): 697–718. doi:10.1007/s11116-017-9830-y.

- Schatzki, T. R. 2012. “A Primer on Practices: Theory and Research.„ In Practice-Based Education, edited by Higgs J., Barnett R., and Billett S., 13–26. London: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-128-3.

- Scheurenbrand, K., E. Parsons, B. Cappellini, and A. Patterson. 2018. “Cycling into Headwinds: Analyzing Practices that Inhibit Sustainability.” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 37 (2): 227–244. doi:10.1177/0743915618810440.

- Schwanen, T., D. Banister, and J. Anable. 2012. “Rethinking Habits and Their Role in Behaviour Change: The Case of Low-Carbon Mobility.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 522–532. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.06.003.

- Sersli, S., M. Gislason, N. Scott, and M. Winters. 2020. “Riding Alone and Together: Is Mobility of Care at Odds with Mothers’ Bicycling?” Journal of Transport Geography 83. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102645.

- Shaw, L., R. G. Poulos, J. Hatfield, and C. Rissel. 2015. “Transport Cyclists and Road Rules: What Influences the Decisions They Make?” Injury Prevention. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041243.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. London: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781446250655.

- Sopjani, L., J. J. Stier, M. Hesselgren, and R. Sofia. 2020. “Shared Mobility Services versus Private Car: Implications of Changes in Everyday Life.” Journal of Cleaner Production 259. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120845.

- Sorton, A., and T. Walsh. 1994. “Bicycle Stress Level as a Tool to Evaluate Urban and Suburban Bicycle Compatibility.” Transportation Research Record 1438: 17–24.

- Spinney, J. 2008. “Cycling between the Traffic: Mobility, Identity and Space.” Urban Design 108 (Autumn): 28–30.

- Spotswood, F., T. Chatterton, A. Tapp, and D. Williams. 2015. “Analysing Cycling as a Social Practice: An Empirical Grounding for Behaviour Change.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 29: 22–33. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2014.12.001.

- Spurling, N., A. Mcmeekin, E. Shove, D. Southerton, and D. Welch. 2013. Interventions in Practice : Re-Framing Policy Approaches to Consumer Behaviour. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester, Sustainable Practices Research Group.

- Steinbach, R., J. Green, J. Datta, and P. Edwards. 2011. “Cycling and the City: A Case Study of How Gendered, Ethnic and Class Identities Can Shape Healthy Transport Choices.” Social Science and Medicine 72 (7): 1123–1130. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.033.

- Thomsen, T. U. 2005. “Parents’ Construction of Traffic Safety: Children’s Independent Mobility at Risk?” Social Perspectives On Mobility (Transport and Society), 11–28. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315242880/chapters/10.4324/9781315242880-9.

- Urry, J. 2004. “The ‘System’ of Automobility.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (5): 25–39. doi:10.1177/0263276404046059.

- Vedel, S. E., J. B. Jacobsen, and H. Skov-Petersen. 2017. “Bicyclists’ Preferences for Route Characteristics and Crowding in Copenhagen – A Choice Experiment Study of Commuters.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 100: 53–64. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.04.006.

- Warde, A. 2005. “Consumption and Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture 5 (2): 131–153. doi:10.1177/1469540505053090.

- Watson, M. 2012. “How Theories of Practice Can Inform Transition to a Decarbonised Transport System.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.04.002.

- Wu, C., L. Yao, and K. Zhang. 2012. “The Red-Light Running Behavior of Electric Bike Riders and Cyclists at Urban Intersections in China: An Observational Study.” Accident Analysis and Prevention. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2011.06.001.