ABSTRACT

This article coins and deploys the term kinetic health as part of a broader attempt to historicize the mobilities paradigm from the standpoint of past community prophylactics. It uses the example of Galenic or humoral medicine, which for millennia organized individual and group health as a dynamic systems balance among several spheres of intersecting fixities and flows. The radical situatedness it fostered emerges clearly from tracing preventative health interventions among different communities in ‘preindustrial’ Europe, including urban dwellers, miners and armies, whose different motilities both bound people to and released them from their immediate environment. Beyond reframing past practices, kinetic health benefits mobilities studies scholars by interrogating stagist narratives of civilization and modernization in two ways. First, as an analytic, because although humoralism and other medical systems continue to inform present-day approaches to health and disease around the globe, they are often obscured by layers of colonialism and biomedicine. And secondly, as a perch for viewing the long-term ebb, flow and mingling of ideas about ill/health as an assemblage of (social) bodies and their natural and social environments.

I Introduction

Engineers of the mobility turn rightly stress that understanding assemblages of the social has suffered from a sedentary bias (Cresswell Citation2006; Sheller and Urry Citation2006; Hannam, Sheller, and Urry Citation2006; Urry Citation2007, Citation2014; Ingold and Vergunst Citation2008; Adey Citation2009; Fincham, McGuinness, and Murray Citation2010; Büscher, Urry, and Witchger Citation2011; Merriman Citation2012; Merriman et al. Citation2013; Jensen Citation2015). The critique grew out of the spatial experience of late modernity, which saw an intensification in all forms of human travel and its constraints and, more broadly, the (un)intentional movement and blockage of myriad matters, including viruses, invasive species, natural gases, information and commercial goods. The marked difference in scale occasioned a reexamination of the relations between fixed and moving things, including the knowledge, technologies and infrastructures that shape societies. Embracing mobilities scholarship yet addressing its latent modernist bias, transportation and migration historians, as well as literary scholars and archaeologists, have made cogent observations on how to open mobility’s black box for earlier eras as well (Fumerton Citation2006; Greenblatt et al. Citation2010; Hahn and Weiss Citation2013; Leary Citation2014; Merriman and Pearce Citation2017; and implicitly, Jervis Citation2017). Their insights have shown that mobilities’ impact is fundamental to understanding past cultures and their interconnections centuries and even millennia before the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, traditional markers of modernity’s onset. The present article moves beyond the general claim of mobilities’ analytical relevance to studying past cultures. It argues that mobility did not merely ‘happen’ to earlier societies as well or impacted them in similar ways; rather, in certain well-documented cases groups consciously moored themselves by reflecting deliberately on a range of mobility regimes at different scales simultaneously, thereby construing their environments in terms of health and disease. This historical specificity emerges from a reconstruction of community prophylactics among different groups, and in ways that offer a robust emic perspective sometimes missing from existing historical scholarship on mobilities. Even more broadly, however, honing this perspective releases the study of g/local health, including its history, from a priori periodizations that lump certain cultures into an ‘old = local = static’ camp and others into a ‘new = global = mobile’ one (Ho Citation2017). Indeed, echoing recent scholarship on epigenetics (Melloni Citation2019), the concept of kinetic health allows us to see that bodies’ unboundedness (or plasticity), be it as a biological or psychological concept, has a more complex past than a linear decline since modernization.

The present section introduces ‘kinetic health’ as an umbrella term for the dynamism inherent to many earlier cultures’ understanding of health and disease, often stemming from Hippocratic, Galenic or humoral medicine. It demonstrates how the latter’s emphasis on the impact of intersecting (im)mobilities on individual and communal health gave meaning to complex human and material assemblages, a phenomenon that urban historians of Europe in particular have documented and analyzed in terms of fixities, flows and motilities. Moving past cities, sections II and III illustrate how kinetic health informed lesser-known interventions developed by mostly rural miners and often itinerant armies between the twelfth and sixteenth century. They explore diverse types of written, material and pictorial evidence for prophylactic programs and behaviors. These collectively shore up, not only the general relevance of mobilities, but earlier communities’ direct understanding of mooring as part of a preventative strategy cognizant of different environmental layers operating at once. Indeed, even the most ostensibly ‘terrained’ groups of miners and armies saw themselves as being impacted by (im)mobilities far beyond their reach, a tension that mobilities scholars at least implicitly associate with later modernity and globalization. Last but not least, beyond enriching historical prisms and exposing what Kathleen Davis has termed ‘the simplex of the “pre”’ (Davis Citation2008, Citation2018), the conclusion will discuss how kinetic health engages scholarship on the radical situatedness of health and disease, an awareness that medical ethnographers, among others, have begun to promote. If humoral or ‘wind’ medicine is thriving around the globe, it often does so concealed beneath more recent layers of (post)colonial and biomedical sediments. Unearthing them and especially their ongoing cultural relevance thus interrogates stagist narratives of civilization (Chakrabarty Citation2000) and provides a more granular emic perspective for medical cultures around the globe, including their understanding of how (social) bodies and environments mingle.

Recognizing the ubiquity of kinetic health and its influence between 1100–1600 requires briefly delving into coeval natural-philosophical theories and evidence for their social pursuit. Until the later eighteenth century, and for nearly two thousand years, the reigning paradigm of health across the Mediterranean world stemmed from Hippocratic and Galenic (or humoral) medical writings (Siraisi Citation1990; Jouanna and Allies Citation2012). The theory radiated from Greek city-states and circulated throughout the Roman Empire to shape medical discourses and practices in what was to become Byzantium (East Rome), the vast Islamic world and, especially since the twelfth century, Europe (Pormann and Savage-Smith Citation2010; Bouras-Vallianatos and Zipser Citation2019). Here, Latin translations of Greek and Roman Galenic authors, often mediated through Arabic and Hebrew renditions and commentaries, began to reach and be studied by local scholars, first in southern Europe, and soon throughout Latin Christendom. Revitalized centers of medical learning such as courts and monasteries, alongside the new urban universities, cultivated the study of Galenic medicine and adapted its ancient principles to Christian structures of knowledge and authority, a process long anticipated by Islamic and Jewish scholarship. By the later twelfth and thirteenth century, Galenism acquired a commanding position among academically-trained physicians. Yet it also insinuated itself into popular and institutional forms of care giving and preventative interventions, be it at the domestic, neighborhood, parish or municipal level, and indeed throughout many, if not all, professional sectors, both urban and rural (Kaye Citation2014, 128–240).

For centuries, then, health (Latin: salus; salubritas) was a condition defined by many inhabitants of Europe as a dynamic systems balance among several moving spheres, most of which interacted outside, even far outside, the human body yet constantly impacted it. As medical historians have repeatedly shown, the integration of Galenism into European mentalities (itself reflecting the mobility of people, texts, ideas, institutions and practices) shaped the negotiation of health at the community level and thus its emergence as a major plank in the era’s biopolitics (Kinzelbach Citation2006; Jørgensen Citation2008; Rawcliffe Citation2013; Fay Citation2015; Skelton Citation2015; Geltner Citation2019a; Coomans Citation2021). From a mobilities standpoint in particular, Galenism promoted a form of fluid or kinetic health that organized the interaction of fixed and moving matters, and framed certain sites as bottlenecks capable of threatening individual and community wellbeing. Notable among the latter were public infrastructures such as wells, canals, drains and sewers, which were vulnerable to clogging through neglect, sabotage or reckless waste disposal. Stagnant refuse would not merely hinder a city’s metabolic flow, but was in fact seen as polluting the surrounding air, creating foul-smelling, disease-inducing miasmas. Yet communities – urban and rural, sedentary and mobile – faced additional health risks and designed their moorings on the basis of an ongoing analysis of flows and fixities that often began far from their specific location.

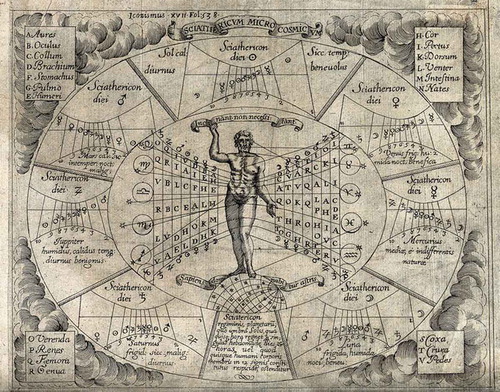

Fixities and flows thus directly shaped European prophylactic cultures. Drawing on the Hippocratic text Airs, Waters, Places (early fifth century BCE), Galenic authors identified several intersecting spheres of movement that impact health (see ; Dick Citation1946; Bober Citation1948; Gerin Citation1983; Page Citation2002; Carey Citation2004): 1) the in-body interaction of the four humors; 2) one’s immediate circumstances, including air quality, the ability to exercise, bathe, sleep, consume food and excrete it, and control one’s emotions (aka the six ‘non-naturals’); 3) the surrounding community, its attributes, activities and physical environment; 4) the rotation and operation of the seasons within a given climactic, topographical and geological region; and 5) stellar movement, as it impacts both the Earth’s regions and individuals’ organs. All but the third of these spheres have occupied generations of medical historians, although it is abundantly in the third (and second) sphere that the scope for impacting individual and especially communal health resides. Nor was the insight originally confined to circles of medical theorists and learned elites; as we shall see, contemporaries intervened to healthscape their surroundings, knowingly or unwittingly relying on preventative Galenic principles.

Figure 1. A Zodiac Man. The chart purports to show how different planets, each with its own climactic/humoral admixture, affect different parts of the human body (listed A to V in the four corners). Note that the man stands atop a tilted globe, his feet situated in particular coordinates, thereby connecting at least four of the five spheres discussed above: the internal and external body, the world region and the cosmos. Engraving by Pierre Miotte (Rome, 1646). Wellcome Collection No. 46389i. Republished under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Health, in other words, hardly ‘came to be associated with circulation’ as a result of the Scientific Revolution and William Harvey’s work, nor did ‘[u]rban planners seek to maximize flow and movement’ in response to that insight (Cresswell Citation2006, 7 and 8, respectively). Rather, prophylactic programs designed to promote health and fight disease at the population level are widely attested for earlier eras. What is more, such programs owed much to Galenic thinking about how bodies’ dynamic humoral balance is impacted by their fluid social, moral and material environments, including the home, the workplace and shared amenities such as markets, wells, roads and canals. Humoral health was premised on a nodal society networked with fixed and moving matter, a notion that remained highly influential in Europe until the eighteenth century and, as the field of epigenetics attests, scarcely passed with the rise of modern biomedicine.

At the individual level, the radical situatedness of Galenic health had major implications for curative and preventative measures, including the specific value attributed to spatial displacements such as eating, defecating and bloodletting, and the appropriate time to undergo certain medical procedures. Scaled up, the same contingency held true for groups, communities and populations, whose wellbeing was seen to depend on the cooperation (or coercion) of numerous individuals, potentially with different humoral constitutions (known as complexiones), agendas and restrictions, as well as matter. At each interconnected level, therefore, the flow of matter was generally welcome, but the negative or positive value of volumes, velocities and directionalities was always context-dependent (e.g. on climate, season, vessels and sinks’ location) and thus open to (inter)subjective interpretation. The Galenic paradigm thus provided communities with a means to negotiate the movement of matter as part of their preventative health programs by allowing them to both consider and transcend the locality of health.

To date, the richest evidence for such processes comes from European cities, whose proliferation since the twelfth century nearly coincided with the intensified pouring of Galenic knowledge into the region. Demographic, metabolic and other pressures on urban communities were substantial, and balancing them required monitoring, prioritization and the constant settlement of disputes (Rawcliffe and Weeda Citation2019). As a rule, urban policing was designed to safeguard the political and economic interests of local elites (Roberts Citation2019). It thus involved the imposition of an uneven mobilities regime and a top-down exercise of what scholars have termed ‘motility’ (Young Citation1980; Doherty Citation2015; Sheller Citation2016; Marston Citation2019; Blondin Citation2020). The surveillance principles these agents employed were grounded (and certainly legitimated) in Galenic terms, which emphasized the positive flow of air, water and other matters and their role in the reduction of nuisances and miasmas, major causes of humoral imbalance and therefore of disease. City governments regularly consulted physicians and astrologers (often similarly trained) in order to prepare for harms soon to be caused by the onset of plague or famine indicated by the stars (Nutton Citation1981). Urban officials also ensured that practitioners performed certain medical procedures only on auspicious dates (Bober Citation1948, 11–13). At an even more local level, they identified three clusters of threats to residents’ health which, unlike climate and stellar movement, they could ostensibly control: decaying matter, such as stagnant pools of blood and tainted water, carcasses, dung and various forms of artisanal waste; immoral behavior such as gambling, blasphemy, prostitution and selling corrupt produce; and the mistreatment or neglect of infrastructures, whose malfunction hampered commercial traffic, hydraulic energy input and waste removal, and risked causing injury to human and non-human animals. Balancing between the fixity of infrastructures and the flow of matter through them thus acted as a Galenic linchpin between individual and community health on the one hand, and the more expansive influence of region, climate and the cosmos, on the other (Zaneri and Geltner Citation2021). Decades of scholarship by urban historians and archaeologists have unearthed abundant evidence for interventions designed in this very light and traced their enforcement and impact. Yet the same quest for a dynamic systems balance that guided cities and their leaders, charitable organizations, guilds and neighborhoods, is richly attested for rural and non-sedentary groups, including miners, shipmates, armies, pilgrims and peripatetic princely courts. Resisting an urban and sedentary bias, therefore, is not merely possible for earlier eras, but it actually shores up further ways in which mobilities organized public health. The following two sections explore two such examples: miners and armies.

II Miners

There are compelling reasons to see mines as multi-layered bottlenecks (Halpern Citation2020). Yet from a kinetic health perspective they are an amalgam of fixities as well as flows whose risk management required careful manipulation by the communities digging, smelting and living around them (Hitzinger Citation1860; Häbler Citation1897; Tomaschek Citation1897; Von Wolfstrigl-Wolfskron Citation1903; Hoppe Citation1908; Bailly-Maître Citation2004). By the mid sixteenth century hundreds of mines dotted Europe, providing work for more than 100,000 people (Nef Citation1964, 43). And although mining sites came in different shapes and sizes, they shared certain characteristics that allow us to analyze them as a group. First, to an even greater extent than city dwellers, miners occupied relatively small worlds; they seldom moved around, for the seams they tapped were often quite rich and the tools they had meant that progress was slow. Modest velocity, however, did not define miners’ motility, as we shall see. Next, many mining communities were occupationally diverse, not only in terms of labor division and specialization underground, but also thanks to metallurgical and mineralogical processing above ground, including by women and children. Thus, and perhaps in contrast to their rough, isolated and masculine ethos since the nineteenth century (Barragán Romano and Papastefanaki 2020), earlier miners could live in multigenerational communities, occupy family households, engage in animal husbandry, artisanship, horticulture and trade, see a doctor and celebrate mass in similar fashion to members of any urban parish (Bailly-Maître and Benoit Citation2006; Verna Citation2020; Geltner and Weeda Citation2021). I emphasize their relatively stronger resemblance to city dwellers since, unlike the vast majority of rustics (and not a few members of the urban underclasses), miners had significant privileges both individually and as a community, in recognition of their unique hardships and special contribution to landlords’ coffers. These privileges made thinking preventatively about mines’ salubriousness both pertinent and likely.

From a mobilities perspective, mines epitomize the mingling of society and matter, their networked ecology, and how the relations between flow and fixity shaped preventative health programs above and below the ground. The flow of all matter (including people) within the mine, and to an extent above it, impacted communities’ safety and wellbeing and was understood as such in Galenic terms. Putting aside open-pit and alluvial mining, which certainly existed at this time, mines’ depth before the Industrial Revolution typically never reached more than several dozen meters vertically or a few hundred meters horizontally. Yet even in those modest sites things threatened to move in excessive quantity, a destructive direction, too slowly or too fast to maintain the required systems balance for safeguarding workers’ health. Health and safety concerns here, too, were grounded in the humoral tradition, and it is possible to follow their rationale, as surmised and stemming from the Hippocratic treatise, Airs, Waters, Places. Yet while the latter text and its many later commentators focused on how the inherent qualities of winds (‘airs’), water and places impacted people (and indeed, peoples), our attention here is devoted mainly to the flow of air, water and other matter within a fixed place. For, well before the trained physician Georgius Agricola’s influential De re metallica was published posthumously in 1556 (Agricola Citation1991), Galenism shaped people’s assessment of mines’ risks to health and the design of specific preventative measures to counter them. Such programs, as numerous texts, images and material remains attest, reflected the limits imposed by local ecologies upon miners’ and mine matters’ movement, and strove to reduce injury and disease.

To begin with air: ventilation, the movement of air into and out of mine systems, was a great source of concern, as its deterioration through pollution or a blockage of supply could cost lives. Air quality underground is naturally reduced when newly exposed rock begins to absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide and water vapor, a phenomenon known for centuries as black damp (Hendrick and Sizer Citation1992). Non-mechanized mining, however, entailed two additional hazards. First, it often involved lighting fires in order to soften the rock, a procedure which depleted the supply of oxygen and led to asphyxiation and other risks, from spreading fire to collapsing walls. Secondly, miners could accidentally punch into pockets of flammable gas, or simply encounter toxic or even asphyxiant gases, with greater risk of suffocation and injury, immediately or through long exposure. Recognizing such hazards, in 1208 the Bishop of Trent, in northern Italy, instructed that silver miners in nearby Mount Calisio who encountered ‘wind’ (ventum) while digging should refrain from hastening its release, and instead ‘leave that aperture in peace and quiet’ (quiete et pacifice illud apertum dimittant) (Curzel and Varanini Citation2007, no. 137 [2: 821–25]). This suggests the presence of two related insights, which mobilities scholars tend to associate with late modern experiences: first, that sudden flows may be dangerous while chokeholds could in fact promote health when treated properly; and secondly, that human interventions designed to increase flow may well generate new risks of blockage (Law 2006).

Galenic medicine certainly explained the resulting death, respiratory diseases and other symptoms differently than biomedicine would, but miners’ awareness to such dangers was hardly lower on that account. In Trent and elsewhere, mines’ salubriousness and miners’ health could be redefined at any moment by their creation of (or encounter with) a bottleneck through which a substance had to move or become dangerous. A sudden change in fluidity circumstances within a preexisting infrastructure spelled danger below- and even above ground, and reorganized mobilities in both spheres as workers had to leave a tunnel or even a site behind, temporarily or for good. Conscious of such potential disruptions and their costs, many years before the invention of flow-enabling safety lamps in the late nineteenth century and the introduction of domestic canaries in 1911, miners took caution and exercised motility when encountering or anticipating ‘winds’, and dedicated significant resources to digging ventilation shafts for improved air circulation. They also created the unhappy position known in some quarters as the ‘penitent’, a colleague tasked with walking before an advancing group of miners bearing an extended candle to induce preemptive explosions of trapped gas (Sébillot Citation1894, 544–46). This example of a human-material assemblage, including a handheld mobile device meant to negotiate miners’ surroundings demonstrates how miners’ safe conduct intertwined with the circulation of air around them, as both a supplier of oxygen and an evacuator of toxins (see Holton Citation2019).

Another form of preventative mobility revolved around water. Floods in mines could be sudden and deadly, as either rain or subterranean water easily entered shafts and adits, followed the gradient of tunnels and gathered by default at their bottom, that is, precisely where most people would be hard at work and farthest from the exit. To limit such risks, mountainside tunnels were dug where possible with a slight incline from the entrance, allowing water and other unfixed matter to run counter to the direction of miners’ advance. The flow-inducing preventative design had the added advantage of helping to convey excavated matter out of the mine, which from the fifteenth century sometimes used wooden rail technology to deal with their heavy weight (Lewis Citation1970, 8–10). Yet tunnels could also feature drain channels running along their bottom in order to keep the ground surface as dry as possible, slippery ground being another safety challenge that miners faced, especially under poor lighting conditions. Working within a vulnerable system, therefore, miners’ safety was also defined by their position relative to the lowest drain, and of course whether or not that drain had a free exit. Where the location of seams or other factors militated against positive inclines or prevented water from being evacuated outside the mine, miners could use water screws, probably the most ancient form of a positive-displacement pump, dating to the third century BCE (Hanan Citation2003). This manual technology provided excellent protection from light rainfall and even regular internal trickling, but had limited impact during long wet seasons or flash floods, eventually stimulating the development of human-, water- and animal-operated pumps (Hollister-Short Citation1994).

In a sense, then, mines were bottlenecks full of bottlenecks. They required much energy to create, could be wet and slippery, challenging to drain and costly to ventilate. Their preventative design, moreover, had to contend with perennial darkness. Galenic medicine considered the absence of light as having some therapeutic qualities, for instance in alleviating melancholia (Dijkdrent Citation2020, 38–40). But whatever its positive impact on miners’ mental health, darkness was a constant disruption. It undermined safe labor involving sharp and heavy tools, and impeded efficient movement, especially in case of emergency. Vertical ventilation shafts offered limited help in this regard, but archaeological remains attest the regular use, at standard intervals, of lighting fixtures dug deep enough into tunnel walls to render this preventative program compatible with, for instance, another program concerned with sufficient ventilation. Archaeologists have likewise found sturdy, mobile lamps, lit by oil or lard, that could be constantly repositioned. Still, deep darkness was a default condition underground, and as miners advanced vertically and horizontally, they could harness themselves, using a leather belt they strapped on, to a guiding rope fastened along the walls (Panella Citation1938, no. 38 [80]). If darkness struck, this assemblage steered them in the right direction, be that away from or towards the exit, as the case may require. These simple guiding systems have since found many later applications in labor and leisure, presumably because they are cheap, reliable and mobile anti-programs and, as in earlier centuries, give users confidence they can trust their lives with them.

Exhibiting miners’ motility, then, safe movement was affixed, dug and carved onto the mine’s walls, ground and ceiling, as well as sewn and fastened onto human clothes and bodies. The mine’s materiality, its environment and the specific tools and garments miners used, summoned other preventative measures targeting and disciplining workers’ bodies. Financial records, along with depictions of miners and mining communities (see ), attest the use of protective gear, or at least the expectation of its use: thick leggings, leather boots, leather aprons, broad-rim hats, leather gloves and canvas pants, which were often padded at the knees and buttocks to accommodate squatting and sitting at length without causing discomfort and injury. Most importantly, perhaps, they seem to have fulfilled their purpose. Numerous skeletal remains from mining sites in Brandes (French Alps) and Rocca San Silvestro (Tuscany) attest normal heights and life expectancies at birth for the period. Even more surprisingly, they show very little evidence of work-related trauma (Bailly-Maître and Bruno-Dupraz Citation1994, 105–52; Francovich and Gruspier Citation1999).

Figure 2. The Kutná Hora silver mines and metallurgical works. Tempera, parchment, 643 mm (height) x 442 mm (width). The image conveys the dynamism of the Central Bohemian site, straddling under- and over-ground activities, and the variety of tools and contraptions for extracting, sifting and manipulating excavated matter. Note the range of people of different statuses occupying the site, including women, men and children, and their protective work apparel. Unknown painter, fifteenth century. By kind permission of GASK: The Gallery of the Central Bohemian Region, Kutná Hora. Digital scan by Aip Beroun, Klementinum

Certainly, these communities’ health, and the mobility regimes governing them, neither began nor ended underground, nor even in the mine’s direct vicinity. By coeval notions of kinetic health, they relied on a further set of mobilities whose operation too can be taken out of their black boxes. Miners’ relative privilege meant that, even compared with other rustics performing hard manual labor, they had access to reasonable diets and comfortable accommodations, adequate rest periods and a combination of salaries and amenities that rendered life more than tolerable, certainly in coeval terms. A combination of nutritious diets and protective measures consciously promoted positive health outcomes. These in turn relied upon transportation infrastructures connecting relatively fixed activities such as agriculture and fairly mobile ones such as animal husbandry, and whose seasonality and tenuous nature were mitigated through the construction of local warehouses, a fixture of rural as well as urban public health and social order. Further, mine owners relied on Galenic principles to promote cleanliness and behaviors understood as maintaining a salubrious environment above ground, including the preservation of a correct flow of waste matter. In this spirit, miners near Lyons in the mid fifteenth century were liable to lose at least one week’s salary if caught littering, a steep penalty justified according to the ordinances because ‘the stench and infection caused by such filth create numerous inconveniences to the laborers, operators and other people reliant on these mines’ (Luce Citation1877, no. 36 [201]).

On the other hand, the free circulation of toxins generated by metallurgical processing could leave major, indeed dangerously high residues that attached themselves to their surroundings. Skeletal remains from thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Brandes, for instance, confirm that, however difficult and dangerous underground activities may have been, some of the greatest risks mining communities faced actually stemmed from unhealthy flows above ground which impacted entire communities (Bailly-Maître and Bruno-Dupraz Citation1994, 105–52). Hazardous fumes spread through the air, which people and the animals they raised breathed, and left permanent traces in local flora and fauna, which were in turn consumed directly by humans and/or indirectly via grazing animals. There is however archaeological evidence to suggest that mining communities recognized and acted prophylactically also against such hazardous flows (albeit differently understood) through zoning, a common practice for manipulating flows in the era’s cities and, as we shall soon see, military camps (Van Oosten Citation2019). Locating noxious activities far from domiciles, and harnessing the prevalent winds to blow miasmatic fumes away from population centers, reduced the impact of polluting activities on strategic resources such as cisterns and wells. As such, they were measures integral to these communities’ prophylactic programs.

Promoting the health of miners at the community level involved additional mobilities, especially above ground, from general waste disposal, to the importation of food and other provisions, to religious activities such as processions and visits by local priests and friars, which in turn followed a mostly lunar calendar. Yet none of these appear to have traits that were unique to mines, and can thus be fruitfully explored by the still richer historiography on urban prophylactics.

III Armies

Unlike the sedentary miners, armies were the mobile group par excellence for much of the period under consideration, reflecting and responding to several (infra)structural realities. First and foremost, these outfits’ formation was always in flux; soldiers were mustered and gathered for short terms and often ad hoc to train and fight. Whether they were urban militias, mercenaries or ‘feudal’ contingents, therefore, armies rarely garrisoned in a castle or a permanent camp in times of peace, when guard duty was reduced to a bare minimum and carried out by non-combatants. Stable, recognizable military barracks were accordingly scarce (certainly compared to Roman times) and deemed an unnecessary expense. With the partial exception of fortifications, watch towers and arsenals, moreover, military infrastructures (including roads, gates, ports and waterways) tended to be a subset of civilian ones. Next, campaigns were short and weather-dependent and combatants were expected to supply their own weapons, provisions and transport, notwithstanding some pooling of resources and the occasional contribution of a wealthy benefactor. This meant that the transportability of equipment remained a paramount concern. Finally and relatedly, before the invention of canons, large apparatuses such as siege machines were assembled on site and locally sourced (De Vries Citation1992, 2008). In sum, illustrating an apparent disjuncture between mobility and motility, armies and their equipages continuously reassembled and relied considerably on scarce material, financial and intellectual infrastructures, albeit without having regular control over them.

Armies’ wellbeing depended on their ability to balance limited infrastructures with an urgent need to reduce friction with their environments. From a broadly shared kinetic health perspective, moreover, armies had to consider several spheres of movement intersecting with their group profile and shaping specific hygienic needs. Here as elsewhere, preventative programs were considered far more practical than curative ones, also since under most circumstances armies’ greatest killers were starvation and disease, not battle wounds, which nonetheless remain the focus of the era’s medical historiography (Majno Citation1975; Gabriel and Metz Citation1992; Mitchell Citation2004; Tracy and De Vries 2015). Between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries armies pursued such programs, often drawing on Galenic insights. Military elites, which largely overlapped with political and economic ones, were products of a Galenic culture. Even if generals did not realize it (which is unlikely), their training steeped them in ancient Greek and Roman letters, including engineering, architecture, natural philosophy, veterinary science and medicine. The ensemble sensitized them to the dangers they should expect on the campaign trail and provided them with guidelines on how to avoid them or reduce their harm (Geltner Citation2019b).

Bivouacking and setting up temporary camps illustrate the complexity of military mooring in this period, as well as the conscious deliberations it involved. Rest itself, like diet, formed part of any army’s preventative program. Yet, with limited fixed infrastructures, including supply lines, choosing a resting place involved some tough choices, balancing efficiency, safety and strategy. The tactical literature of the period, with its deep roots in ancient learning, consistently defined the salubriousness of places in Galenic terms, including their associated mobilities. If miners had little choice about where they lived and how they moved underground, a marching army had to consider a site’s distance, topography and climate, especially with respect to its human and animal constituents. Such considerations, as befits any humoral assessment of health hazards, took kineticism for granted, including the ramifications of a current stellar constellation, the influence of seasons and climate on provisions, and what would constitute a healthy diet for a specific army under changing circumstances. What is more, according to the most popular military treatise of the era, Vegetius’ De re militari (early fifth century), limited marching, like regular periods of inactivity, were insufficient to ward off disease. It was how armies rested, and where, which were of paramount concern. In other words, soldiers’ health too was recognized as being kinetic, subject to intersecting mobilities, and attempts to promote it had to be defined ecologically and materially in order to maintain a dynamic systems balance. As Vegetius summarized it, armies’ salubriousness,

depends on the choice of situation and water, on the season of the year, medicine and exercise. As to the situation, the army should never continue in the neighborhood of unwholesome marshes any length of time, or on dry plains or eminences without some sort of shade or shelter. In the summer, the troops should never encamp without tents. And their marches, in that season of the year when the heat is excessive, should begin by break of day so that they may arrive at the place of destination in good time. Otherwise they will contract diseases from the heat of the weather and the fatigue of the march. In severe winter they should never march in the night in frost and snow, or be exposed to want of wood or clothes. A soldier, starved with cold, can neither be healthy nor fit for service. The water must be wholesome and not marshy. Bad water is a kind of poison and the cause of epidemic distempers (Vegetius Citation2004, III, ii [67]).

As the earliest Latin treatise on the topic, De re militari had an outsized influence on the genre in Europe, having also been copied and translated into different vernaculars since at least the thirteenth century (Richardot Citation1998; Allmand Citation2011). Even those military strategists who paved their own literary path remained indebted both to Vegetius and the insights of Hippocratic and Galenic medicine more broadly. Christine de Pizan (1364-c. 1430), for instance, explicitly linked an army’s good health to a combination of mobilities in several spheres, namely the quality of a camp’s location, including its water sources and climate, and soldiers’ exercise (De Pizan Citation1999, 1.14 [42–43]). Her contemporary, the Benedictine monk Honoré Bonet (c. 1340-c. 1410), likewise stressed a general’s duty to assess the health of a place before setting up camp, as defined in the traditional terms of airs, waters and places (Bonet Citation1949, 4.1 [125–26]; and see Da Legnano Citation1917, 19 [96]). A generation later, the Italian military engineer Roberto Valturio (1410–1475) reminded readers of his own eponymous treatise that an area’s fecundity and quality of local resources is meaningless without considering the occupiers’ own humoral and thus dynamic constitution (Valturio Citation2006, 78). And Niccolò Machiavelli’s Arte della guerra (1519–20) encouraged his audience to follow the example of the ancient Romans, and in particular their study of camps’ location, a process that involved forensic assessment, including of its inhabitants: ‘[S]o when the latter seemed to have a bad complexion, broken-winded, or hosting another infection, they did not tarry there’ (Machiavelli Citation1769, 243).

Since military medical historians have tended to focus on the theory and practice of healing battlefield wounds, it remains unclear how thoroughly generals obeyed the era’s textbook (or, indeed, commonsensical) prophylactic guidelines. That knowledge gap is beginning to shrink thanks to recent developments in military bioarcheology, which augments traditional osteoarcheologists’ study of trauma. Along with environmental data gathered from trees, soil and waste deposits, our knowledge of diets and disease conditions continues to evolve, even if linking those specifically to military communities and their preventative measures remains a challenge (Mitchell Citation2007; Pluskowski Citation2019). There is significant evidence, at any rate, to suggest that kinetic health was a prevalent paradigm in non-combat military contexts. For instance, medical advice informed by Galenism permeates the numerous military ordinances throughout and beyond the crusading era (King Citation1981, 42, 47, 57, 77, 127, 169–70). Adam of Cremona’s health regimen for pilgrims, the Regimen iter agentium vel peregrinatium, was in fact presented to emperor Frederick II prior to his (aborted) crusade of 1227 (Adam of Cremona Citation1913). And, in early 1310, renowned physician and royal envoy Arnauld of Villanova (1240?-1311) drafted a health policy brief specifically for the Aragonese army laying siege at the time to Almería, in Muslim-controlled Andalusia.

Arnauld’s text was brief and pragmatic, devoid of direct citations or references, and relied (indeed, consciously underscored) the author’s authority in such matters. Even without referencing his sources, however, Arnauld’s debt to Airs, Waters, Places and later Galenic insights, not to mention Vegetius (a copy of whose manual Arnauld owned), is manifest. In particular, the text advocates optimizing the camp’s location, and the king’s tent in it, according to the direction of health-promoting winds; the regular consumption of prophylactic tisanes, which could be produced to suit different budgets; the forensic testing of water sources, including springs, rivers, wells and cisterns, which may have been poisoned or were otherwise unfit for this particular army’s consumption; and the digging of trenches outside the camp for depositing animal waste as well as dead bodies, all of which were to be covered with earth. The latter measures are explicitly counselled ‘so that the army may avoid epidemic disease’ (ut exercitus ab epidemia preservetur) (McVaugh Citation1992, 210). Arnauld’s regimen probably arrived too late for the Aragonese army to benefit from it directly. Yet given the traditional underpinnings of his advice, and the well-documented presence of similarly trained physicians during various military campaigns (Pellegrini Citation1932; Jacquart Citation1981, 118–19; Cifuentes and García-Ballester Citation1990), such recommendations were probably common, albeit perhaps delivered orally. In any event, and as the text strongly implies, military leaders were prepared to conduct their own assessment of environmental health risks, which in turn manipulated flows and fixities impacting their camp and marches. Thus, during his invasion of Sardinia in 1354–55, Peter IV regularly corresponded with army leaders and medical personnel about health conditions in various parts of the island, (re)directing movements and revising strategies to address changing health situations on the ground. The letters he exchanged routinely describe locations in terms of good ‘airs’ and ‘places’ and later justified summoning reinforcements on the grounds that soldiers were succumbing to the ‘bad health of the land’ (Cifuentes and García-Ballester Citation1990, 193–95). Clearly, then, a Galenic analysis of dynamic health conditions informed policy and decision-making in real time concerning the pace, direction and length of armies’ movement and rest, and in consideration of the quality and availability of local infrastructures.

Finally, Arnauld’s health regimen also treats two items that armies tend to leave behind, and which created clear health hazards: organic waste and dead bodies, both of which could clog pathways and cause miasmas. The text accordingly instructs how to dispose of them in order to conserve the army’s health, assuming troops were to stay put for a while, and perhaps out of consideration to neighboring communities and other passersby. This may strike present-day readers as an overly optimistic reading of such behaviors, or else their misrepresentation as typical ecological thinking. However, as Sander Govaerts (Citation2021) has ably shown for the Meuse region between the thirteenth and mid nineteenth century, armies consciously engaged in longer-term planning and indeed the sustainable management of lands that they temporarily occupied or merely traversed, and not only out of courtesy to local populations. Food scarcity was an army’s gravest fear, and given minimal storage infrastructures and short supply lines, a scorched-earth policy would have been generally ill-advised. Moreover, leaving large and untreated amounts of miasma-inducing cadavers would have likewise constituted a recognizable and unwieldy form of medical warfare, which armies accordingly avoided if they could. All this suggests that, however different the paradigm might be from a modern biomedical perspective, ecological thinking and action were common, cognizant and strategic among armies as well, and often, if not exclusively, informed by the kinetic health principles articulated by Galenic medicine.

IV Conclusions

Galenic kineticism, that is the intersection of different scales of mobilities impacting individual and communal health, gave meaning to complex human and material assemblages. Between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, miners and armies, much like coeval urban dwellers and numerous other groups, relied on humoral principles to design preventative interventions suited to highly specific and changing circumstances. Their moorings involved a multiscalar understanding of different types of interactions occurring simultaneously in individual bodies, their direct material environments, neighboring communities, climatic regions, and even the globe and cosmos. Despite real and perceived differences in their resources and the spatial configurations of g/local fixities and flows, hygienic norms and practices among many communities were grounded in the notion that matter moved and mobilities mattered. If so, the history as well as theory of mobilities is longer and richer than is often implied by the paradigm’s scholars, and augments the nuanced perspective already being shaped by literary, migration and transportation historians of earlier eras. While some qualitative differences are manifest between the era in focus and later (and earlier!) centuries in Europe, societies across this conventional divide clearly shared key spatial practices, even profoundly so, and thought in environmental terms. Indeed, given the multiple scales it straddled, there is little doubt that Galenism, which linked bodily fluids, planets and anything in between (see ), situated every community’s and every individual’s health within a cosmic matrix, global and regional events and seasonal rotations.

Beyond interrogating the implicit chronology and periodization of mobilities studies (and those of many other fields), the present article has several further implications. First, while modernity is often described as comprising a cluster of interconnected global phenomena, it is nonetheless experienced socially and culturally, much like globalization itself (Tsing Citation2005). Understanding global (and arguably even cosmic) events too have a social past, which likewise benefits from being reconstructed through the spatial prism of mobility. Given its kinetic principles, Galenic medicine is clearly a case in point, directly binding several scales of movement, which are nonetheless experienced and recollected in a highly local and historically contingent manner. Such specific experiences, or at least their representations, are sometimes possible to trace back in time, even among non-elites. The cases of miners, armies and city dwellers briefly reviewed above illustrate this and suggest the fruitfulness of further research, including on communities such as mariners, princely courts, monasteries, trade caravans and pilgrims, groups that are by no means unique to western Europe. Collectively these provide programmatic coordinates which students of these cultures’ mobilities may wish to consult.

Secondly, as mentioned at the outset, well before Galenism emerged as a major medical paradigm in Europe, it inhabited Byzantine and Islamic cultures, and especially through the latter’s spread found its way across Asia and Africa centuries prior to Europeans’ dominant presence there. In the Indian subcontinent, for instance, the medical system introduced by Muslim communities arriving from Persia and central Asia came to be known as Unani (‘Greek’) medicine, and has continued to evolve, intersect and wield its influence regionally since at least the thirteenth century (Attewell Citation2007; Speziale Citation2014). What is more, the principles of humoral or ‘wind’ theory, and especially the linked movements of human humors, environmental elements, climates and planets are independently attested in other medical cultures, including Buddhism and several Indic religions, which developed their own emphasis on health as a kinetic state straddling bodies and places (Horden and Hsü Citation2013; Salguero Citation2017; Yoeli-Tlalim Citation2010, Citation2019; Köhle and Kuriyama Citation2020). Recognizing kineticism’s ubiquity, durability and malleability thus provides health historians of different regions and eras with further subjects and objects of long-term, transregional and comparative study. These could in turn help (re)evaluate qualitative changes supposedly impacting mobilities and which were introduced by new industrial technologies, economic regimes, political systems and medical theories, to name a few commonly invoked triggers or paradigm shifts associated with modernization in Europe and colonialism abroad.

Lastly, mobilities scholars at large may find that this particular historical dimension enriches existing perspectives on cultural practices, for instance those honed by medical anthropologists such as João Biehl (Citation2005, Citation2007), Margaret Lock and Vinh-Kim Nguyen (2018). It is possible, for instance, that the interconnectivity and radical situatedness their work underscores has (precolonial) precedents worth considering, and which may continue to shape epistemologies of health and disease. At both the individual and community level, such investigations may benefit from greater attention to ill/health as a mingling of bodies and things, as these assemblages are sometimes understood. Furthermore, it sensitizes scholars of mobilities to the ecological thinking, or indeed cosmology, underpinning kinetic health, and which is broadly shared by literally billions of people around the globe, whether that type of kineticism is a hegemonic concept where they live or an epistemology they carry with them as travelers, migrants, refugees, soldiers or seasonal workers. As Kyle Whyte, Jared Talley and Julia Gibson (2019) have recently shown, recovering indigenous practices obfuscated by layers of colonialism and modernization interrogates the novelty of certain mobilities and help us rethink strategies of community resilience. By taking longstanding kinetic paradigms of health into account, the same can be done in various de-, non- or postcolonial contexts around the world.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Johan Lindquist and Markus Stauff; and to Janna Coomans, Sophie Page, Claire Weeda and Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam of Cremona. 1913. “Regimen iter agentium vel peregrinantium.” In Ärztliche Verhaltungsmaßregeln auf dem Heerzug ins Heilige Land für Kaiser Friedrich II. Geschrieben von Adam v. Cremona (ca. 1227). Ed. F. Hönger. Leipzig: Robert Noske.

- Adey, P. 2009. Mobility. London and New York: Routledge.

- Agricola, G. 1991. De re metallica. Trans. Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. New York: Dover Publications.

- Allmand, C. 2011. The De re militari of Vegetius. The Reception, Transmission and Legacy of a Roman Text in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Attewell, G. 2007. Refiguring Unani Tibb: Plural Healing in Late Colonial India. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

- Bailly-Maître, M.-C. 2004. “Les agglomerations minières au moyen âge en Europe occidentale.” In Naissance et développement des villes minières en Europe, edited by J.-P. Poussou and A. Lottin, 215–226. Arras: Artois Presses Université.

- Bailly-Maître, M.-C., and P. Benoit. 2006. “L‘habitat des mineurs: Brandes-en-Oisans et Pampailly.” In Cadre de vie et manières d’habiter (XIIe-XVIe siècle), edited by D. Alexandre-Bidon, F. Piponnier, and J.-M. Poisson, 259–265. Caen: Publications du CRAHM.

- Bailly-Maître, M.-C., and J. Bruno-Dupraz. 1994. Brandes-en-Oisans. La mine d’argent des Dauphins (XIIe-XIVe siècles), Isère. Lyons: Alpara.

- Biehl, J. 2005. Vita: Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment. Berkeley, etc.: University of California Press.

- Biehl, J. 2007. The Will to Live: AIDS Therapies and the Politics of Survival. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Blondin, S. 2020. “Understanding Involuntary Immobility in the Bartand Valley of Tajikistan through the Prism of Motility.” Mobilities 15 (4): 543–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1746146.

- Bober, H. 1948. “The Zodiacal Miniature of the Tres Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry: Its Sources and Meaning.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 11: 1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/750460.

- Bonet, H. 1949. The Tree of Battles. Ed. and trans. G. W. Coopland. Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press.

- Bouras-Vallianatos, P., and B. Zipser, eds. 2019. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen. Leiden: Brill.

- Büscher, M., J. Urry, and K. Witchger, eds. 2011. Mobile Methods. London: Routledge.

- Carey, H. M. 2004. “Astrological Medicine and the Medieval English Folded Almanac.” Social History of Medicine 17 (3): 345–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/17.3.345.

- Chakrabarty, D. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cifuentes, L., and L. García-Ballester. 1990. “Els professionals sanitaris de La Corona d’Aragó en l’expedició militar a Sardenya de 1354-1355.” Arxiu De Textos Catalans Antics 9: 183–214.

- Coomans, J. 2021. Community, Urban Health and Environment in the Late Medieval Low Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York: Routledge.

- Curzel, E., and G. M. Varanini, with D. Frioli 2007. Codex Wangianus: I cartulari della Chiesa trentina (secoli XIII-XIV). Vol. 2. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Da Legnano, G. 1917. Tractatus de bello, de represaliis et de duello. Ed. H. Thomas Erskine. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Carnegie Institution.

- Davis, K. 2008. Periodization and Sovereignty: How Ideas of Feudalism and Secularization Govern the Politics of Time. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Davis, K. 2018. “From Periodization to the Autoimmune Secular State.” Griffith Law Review 27 (4): 411–425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2018.1669266.

- De Pizan, C. 1999. The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Ed. W. Charity Cannon. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University. Trans. Sumner Willard.

- De Vries, K. 1992. Medieval Military Technology. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

- De Vries, K. 2008. Medieval Warfare, 1300–1450. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Dick, H. G. 1946. “Students of Physic and Astrology: A Survey of Astrological Medicine in the Age of Science.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1 (3): 419–433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/1.3.419.

- Dijkdrent, M. 2020. Healing through Space: An Essay on the Meanings of Space in the St. Caeciliagasthuis in Leiden. MA thesis: Leiden University.

- Doherty, C. 2015. “Agentive Motility Meets Structural Viscosity: Australian Families Relocating in Educational Markets.” Mobilities 10 (2): 249–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.853951.

- Fay, I. 2015. Health and the City: Disease, Environment and Government in Norwich, 1200-1575. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Fincham, B., M. McGuinness, and L. Murray, eds. 2010. Mobile Methodologies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Francovich, R., and K. Gruspier. 1999. “Relating Cemetery Studies to Regional Survey: Rocca San Silvestro, A Case Study.” In Reconstructing Past Population Trends in Mediterranean Europe (3000 BC - AD 1800), edited by J. Bintliff and K. Sbonias, 249–257. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Fumerton, P. 2006. Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gabriel, R. A., and K. S. Metz. 1992. A History of Military Medicine. Vol. 2. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Geltner, G. 2019a. Roads to Health: Infrastructure and Urban Wellbeing in Later Medieval Italy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Geltner, G. 2019b. “In the Camp and on the March: Military Manuals as Sources for Studying Premodern Public Health.” Medical History 63 (1): 44–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2018.62.

- Geltner, G., and C. Weeda. 2021. “Underground and over the Sea: More Community Prophylactics in Europe, 1100–1600.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrab001.

- Gerin, E. 1983. Astrology in the Renaissance: The Zodiac of Life. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Govaerts, S. 2021. Armies and Ecosystems in Premodern Europe. The Meuse Region, 1250–1850. Kalamazoo, MI: ARC Humanities Press.

- Greenblatt, S., et al. 2010. Cultural Mobility: A Manifesto. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Häbler, K. 1897. Die Geschichte der Fugger’schen Handlung in Spanien. Weimar: E. Felber.

- Hahn, H. P., and H. Weiss, eds. 2013. Mobility, Meaning and Transformations of Things. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Halpern, O. 2020. “Golden Futures.” LIMN 10: https://limn.it/articles/golden-futures/( accessed 3 May 2020).

- Hanan, D. Z. 2003. “Pumps, Displacement.” In Encyclopedia of Water Science, edited by B. A. Stewart and T. A. Howell. s.v., 759–763. New York: Marcel Dekker.

- Hannam, K., M. Sheller, and J. Urry. 2006. “Editorial: Mobilities, Immobilities and Moorings.” Mobilities 1 (1): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100500489189.

- Hendrick, D. J., and K. E. Sizer. 1992. “‘Breathing' Coal Mines and Surface Asphyxiation from Stythe (Black Damp).” BMJ Clinical Research Ed 305 (6852): 509–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.305.6852.509.

- Hitzinger, P. 1860. Das Quecksilber-Bergwerk Idria. Ljubliana: Laibach.

- Ho, E. 2017. “Inter-Asian Concepts for Mobile Societies.” The Journal of Asian Studies 76 (4): 907–928. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911817000900.

- Hollister-Short, G. 1994. “The First Half Century of the Rod-Engine (C1540-c1600).” In Mining Before Powder, edited by T. D. Ford and L. Willies, 83–90. Vol. 12. PDMHS Bulletin.

- Holton, M. 2019. “Walking With Technology: Understanding Mobility-Technology Assemblages.” Mobilities 14 (4): 435–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1580866.

- Hoppe, O. 1908. Der Silbergebau zu Schneeberg bis zum Jahre 1500. Freiberg: Gerlachsche Buchdruckerei.

- Horden, P., and E. Hsü, eds. 2013. The Body in Balance: Humoral Medicines in Practice. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Ingold, T., and J. L. Vergunst, eds. 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Jacquart, D. 1981. Le milieu médicale en France en XIIe au XVe siècle. Geneva: Droz.

- Jensen, O. B. 2015. Mobilities. London: Routledge.

- Jervis, B. 2017. “Assembling the Archaeology of the Global Middle Ages.” World Archaeology 49 (5): 666–680. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1406397.

- Jørgensen, D. 2008. “Cooperative Sanitation: Managing Streets and Gutters in Late Medieval England and Scandinavia.” Technology and Culture 49 (3): 547–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.0.0047.

- Jouanna, J., and N. Allies. 2012. “The Legacy of the Hippocratic Treatise ‘On the Nature of Man’: The Theory of the Four Humors.” In Greek Medicine Form Hippocractes to Galen, edited by P. Van Der Eijk, 335–360. Leiden: Brill.

- Kaye, J. 2014. A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of A New Model of Equilibrium and Its Impact on Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- King, E. J., ed. 1981. The Rule, Statutes and Customs of the Hospitallers, 1099-1310. New York: AMS Press.

- Kinzelbach, A. 2006. “Infection, Contagion, and Public Health in Late Medieval and Early Modern German Imperial Towns.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 61 (3): 369–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrj046.

- Köhle, N., and S. Kuriyama. eds. 2020. Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra: ANU Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020.

- Law, J. “Disaster in Agriculture: Or Foot and Mouth Mobilities.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 227–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a37273.

- Leary, J., eds. 2014. Past Mobilities: Archaeological Approaches to Movement and Mobility. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Lewis, M. J. T. 1970. Early Wooden Railways. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Lock, M., and V.-K. Nguyen. 2018. An Anthropology of Biomedicine. 2nd ed ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

- Luce, S. 1877. “De l’exploitation des mines et de la condition des ouvriers mineurs en France au XVe siècle.” Revue des questions historiques 21: 189–203.

- Machiavelli, N. 1769. I sette libri dell’Arte della guerra. Venice: G. Pasquali.

- Majno, G. 1975. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

- Marston, G. 2019. “To Move or Not to Move: Mobility Decision-Making in the Context of Welfare Conditionality and Paid Employment.” Mobilities 14 (5): 596–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1611016.

- McVaugh, M. R. 1992. “Arnald of Villanova’s Regimen Almarie (Regimen Castra Sequentium) and Medieval Military Medicine.” Viator 23: 201–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301280.

- Melloni, M. 2019. Impressionable Biologies: From the Archaeology of Plasticity to the Sociology of Epigenetics. London: Routledge.

- Merriman, P. 2012. Mobility, Space and Culture. London: Routledge.

- Merriman, P. et al. 2013. “Mobility: Geographies, Histories, Sociologies.” Transfers 3 (1): 147–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/trans.2013.030111.

- Merriman, P., and L. Pearce. 2017. “Mobility and the Humanities: An Introduction.” Mobilities 12 (4): 493–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1330853.

- Mitchell, P. D. 2004. Medicine in the Crusades: Warfare, Wounds, and the Medieval Surgeon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, P. D. 2007. “Challenges in the Study of Health and Disease in the Crusaders.” In Faces from the Past: Diachronic Patterns in the Biology and Health Status of Human Populations of the Eastern Mediterranean, British Archaeological Reports (British Series, 1603), edited by F. Marina, et al., 205–212. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Nef, J. 1964. The Conquest of the Material World. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Nutton, V. 1981. “Continuity or Rediscovery? The City Physician in Classical Antiquity and Mediaeval Italy.” In The Town and State Physician in Europe, edited by A. W. Russell, 9–46. Wolfenbüttel: Herzog August Bibliothek.

- Page, S. 2002. Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Panella, A., eds. 1938. Ordinamenta super arte fossarum rameriae et argenteriae Civitatis Massae. Florence: Felice Le Monnier.

- Pellegrini, F. 1932. La medicina militare nel regno di Napoli dall’avvento dei normanni alla cadua degli aragonesi [1139-1503]. Verona: Cabianca.

- Pluskowski, A., ed. 2019. Ecologies of Crusading, Colonization, and Religious Conversion in the Medieval Baltic: Terra Sacra II. Environmental Histories of the North Atlantic World 3. Turnholt: Brepols.

- Pormann, P. E., and E. Savage-Smith. 2010. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Rawcliffe, C. 2013. Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Rawcliffe, C., and C. Weeda, eds. 2019. Policing the Urban Environment in Premodern Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Richardot, P. 1998. Végèce et la culture militaire au Moyen Âge (Ve-XVe siècles). Paris: Institut de Stratégie Comparée: Economica.

- Roberts, G. 2019. Police Power in the Italian Communes, 1228-1326. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Salguero, C. P., ed. and trans. 2017. Buddhism and Medicine: An Anthology of Premodern Sources. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sébillot, P. 1894. Les travaux publics et les mines dans le traditions et les superstitions de tous les pays. Paris: n.p.

- Sheller, M. 2016. “Uneven Mobility Futures: A Foucauldian Approach.” Mobilities 11 (1): 15–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2015.1097038.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a37268.

- Siraisi, N. G. 1990. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Skelton, L. J. 2015. Sanitation in Urban Britain, 1560–1700. London: Routledge.

- Speziale, F. 2014. “A 14th Century Revision of the Avicennian and Ayurvedic Humoral Pathology: The Hybrid Model by Šihāb al–Dīn Nāgaawrī.” Oriens 42 (3–4): 514–532. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/18778372-04203007.

- Tomaschek, J. A. 1897. Das alte Bergrecht von Iglau und seine bergrechlichen Schöffensprüche. Innsbruck: Wagner.

- Tracy, L., and K. DeVries, eds. 2015. Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture. Leiden: Brill.

- Tsing, A. L. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Urry, J. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

- Urry, J. 2014. Sociology beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century. New York and London: Routledge.

- Valturio, R. 2006. De re militari. Umanesimo e arte della guerra tra medioevo e rinascimento. Rimini and Milan: Guaraldi and Y. Press.

- Van Oosten, R. 2019. “Smelly business: de clustering en concentratie van vieze en stinkende beroepen in Leiden in 1581.” Holland: Historisch Tijdschrift 51: 128–132.

- Vegetius, R. F. 2004. De Re Militari. Ed. M. D. Reeve. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Verna, C. 2020. L’industrie au village. Essai de micro-histoire (Arles-sur-Tech, XIVe et XVe siècles). Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Von Wolfstrigl-Wolfskron, M. 1903. Die Tiroler Erzbergbaue, 1301-1665. Innsbruck: Wagnersche Universitäts-Buchhandlung.

- Whyte, K., J. L. Talley, and J. D. Gibson. 2019. “Indigenous Mobility Traditions, Colonialism and the Anthropocene.” Mobilities 14 (3): 319–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1611015.

- Yoeli-Tlalim, R. 2010. “Tibetan ‘Wind’ and ‘Wind’ Illnesses: Towards a Multicultural Approach to Health and Illness.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 41 (4): 318–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.10.005.

- Yoeli-Tlalim, R. 2019. “Galen in Asia?” In A Companion to the Reception of Galen, edited by Bouras-Vallianatos and Zipser. 594–608.

- Young, I. M. 1980. “Throwing Like A Girl: A Phenomenology of Female Body Comportment, Motility and Spatiality”. Human Studies 3 (1): 137–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02331805.

- Zaneri, T., and G. Geltner. 2021. “The Dynamics of Healthscaping: Mapping Communal Hygiene in Bologna, 1287–1383”. Urban History 48. FirstView August 2020 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926820000541.