ABSTRACT

This paper explores how physical mobility shapes migrant youth’s changing relationships to their or their parents’ country of origin. Increasing numbers of youth in the Global North have a migration background and are transnationally engaged in virtual, imaginative and material mobilities. Yet our knowledge of their physical mobility is lacking, having largely been based on retrospective accounts from the country of residence, resulting in depictions of static relationships to a monolithic country of origin. This study takes a processual approach, focusing on mobility trajectories and exploring the sensorial, embodied and emotional aspects of physical mobility as it unfolds. Drawing on 14 months of mobile ethnographic fieldwork with 20 Ghanaian-background young people (aged 15–25) living in Hamburg, Germany, we focus on visits to Ghana to explore how physical mobility changes relationships to the country of origin over time (across several visits) and space (between different places within one visit). We use Urry’s typology of proximity to analyse the specific and changing constellations of people, places and moments that constitute visits and thus shape these relationships. We also reflect on the methodological implications of using three mobile methods: mobility trajectory mapping, following mobility in real-time, and before-and-after interviewing.

Introduction

Young people with a migration background comprise up to half the youth population in major European cities (OECD/European Union Citation2015, 231), constituting a significant demographic with global ties beyond their countries of residence. Second-generation transnationalism literature explores migrant youth’s various practices that connect their countries of origin and residence, such as the sending and receiving of remittances; political activism; religious, cultural and linguistic practices (Haikkola Citation2011; Levitt Citation2009; Levitt and Waters Citation2002); and the use of information and communications technologies to stay in touch with friends and family abroad (Madianou and Miller Citation2011). This literature emphasizes transnational activities from within the country of residence, paying less attention to young people’s physical mobility (Kibria Citation2002; Smith Citation2002). As such, the material, imaginative and virtual mobilities of migrant youth have been well researched, while less is known about their physical mobility, including to and from their or their parents’ country of origin and the effects this mobility has on their lives. Yet recent research suggests that migrant youth’s physical mobility is an empirically and theoretically important phenomenon. Approximately half of migrant youth in several European countries travel to their or their parents’ country of origin at least annually (Schimmer and Van Tubergen Citation2014) and many have diverse transnational mobility patterns, travelling to visit family and for education, among other reasons (Van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018). Building on second-generation transnationalism, second-generation returns literature has shown how and why migrant youth travel to and from their or their parents’ country of origin (King, Christou, and Ahrens Citation2011; Vathi and King Citation2011) and that visits affect their sense of belonging (Binaisa Citation2011; McMichael et al. Citation2017).

However, migrant youth’s physical mobility is not only understudied, it is also unique. Mobilities research shows that physical travel is qualitatively different to other mobilities, comprising embodied, sensorial experiences that cannot be substituted by other transnational practices (Urry Citation2002). Yet the ways in which the embodied experience of physical mobility shapes migrant youth’s changing relationships to the country of origin remain unstudied.

Given the centrality of embodiment to the experience of physical mobility, methodology makes an important difference to how migrant youth’s mobility is studied. Both second-generation transnationalism and returns literatures largely investigate country-of-origin visits retrospectively from the country of residence, making it difficult to generate nuanced and dynamic accounts of how physical travel shapes changing relationships with the country of origin. The mobilities turn (Sheller and Urry Citation2006) spurred a more processual approach to migrant mobility, viewing it as a dynamic process to be studied as it happens (Schapendonk Citation2012). Emerging research on transnational youth mobilities asks how often, why, and in what ways migrant youth are physically mobile, and what this mobility means for their lives (Mazzucato Citation2015; Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2018). Fundamental to this research is a focus on youth mobility trajectories, that is, their physical moves in time and space and their concomitant family constellations (Van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018). A mobility trajectories approach enables researchers to account for what transpires during mobility, including its sensorial, embodied and emotional aspects, and for how mobility experiences change migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin over time and space.

This paper draws on 14 months of mobile ethnographic fieldwork with 20 transnationally mobile young people of Ghanaian background living in Hamburg, Germany. We focus explicitly on physical mobility to analyse how visits to Ghana change migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin over time (across several visits) and space (between different places within one visit). ‘Migrant youth’ include young people aged 15–25 who either migrated internationally themselves or whose parents did. ‘Relationships to the country of origin’ encompass young people’s changing feelings about travelling to the country where they or their parents were born, and the relationships, resources and opportunities they associate with it. While second-generation returns literature often refers to ‘return visits’ to a ‘homeland’, ‘home country’ or simply ‘home’, we speak instead of ‘visits’ to the ‘country of origin’, be it theirs or their parents’. This is because, while migrant youth often have strong attachments to the country of origin, they do not necessarily consider it a home, nor are their visits there always perceived as a ‘return’, especially for those visiting for the first time. ‘Mobility’ thus refers to young people’s physical mobility, specifically, their visits to Ghana. To explore this question, we employ an expanded version of Urry’s (Citation2002) typology of proximity, whose three ‘bases of co-presence’ – face-to-face, face-the-place, and face-the-moment proximity – provide a starting point to analyse the embodied aspects of mobility and understand how the interlinked people, places and moments that constitute these mobility experiences shape young people’s changing relationships to Ghana over time and space. At the start of the century and the advent of the digital age, Urry argued that ‘[t]he global world appears to require that whatever virtual and imaginative connections occur between people, moments of co-presence are also necessary’ (264). Nearly twenty years on, we return to Urry’s typology of proximity to argue for a renewed research focus on physical mobility and its effects on the transnational lives of migrant youth.

Migrant youth transnationalism, mobility and visits to the country of origin

Viewing mobility from afar: second-generation transnationalism and returns

The literature on second-generation transnationalism, although some studies also include first and 1.5 generations, has shown that migrant youth, like adult migrants, engage in diverse transnational practices and build varied relationships with their country of origin. Much of this literature has focused on transnational practices within the country of residence, such as language use, maintenance of cultural and religious practices, and participation in organisations linked to the country of origin. Visits to the country of origin are discussed rarely and only alongside transnational activities in the country of residence. Due to the limited attention given to physical mobility in this literature, the country of origin is often represented in broad brushstrokes as a monolithic, static entity, to which young people either feel a sense of belonging or which reinforces their identification with the country of residence (Kibria Citation2002; Levitt Citation2002, Citation2009; Louie Citation2006; Smith Citation2002).

The mobilities turn prompted transnational migration scholars to look beyond transnational practices within the country of residence and focus specifically on people’s movements. Recent research on second-generation returns focuses on physical mobility as a shaping force of relationships to the country of origin among migrant youth, often also including first and 1.5 generations. While this literature addresses varied return mobilities, including permanent relocation to the country of origin, we focus on the studies that address country-of-origin visits. Such visits help migrant youth shape their identities and sense of belonging to different countries and cultures, learn about their heritage, and establish and maintain family relationships transnationally (Binaisa Citation2011; Conway, Potter, and Bernard Citation2009; McMichael et al. Citation2017; Vathi and King Citation2011).

The second-generation transnationalism and return literatures mostly represent visits as maintaining a stable relationship to a monolithic country of origin – an anchor of unchanging family relationships, cultural heritage, and personal identity within the dynamic fluidity of a life based elsewhere and a turbulent life stage. For example, Conway, Potter and Bernard describe country-of-origin visits as ‘short-term exercises in which much stays the same and little dislocation or little change in circumstances occurs’ (Citation2009, 266). As such, changes and complexities in relationships to the country of origin have been oversimplified and the role of visits in shaping these changes, understudied.

Where changes in migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin have been addressed, they have often been accounted for by macro-level changes in the country of origin or residence, or by generalised life stages. Van Liempt (Citation2011) shows how political shifts, including in migration policy, can change how welcome migrant youth feel when visiting countries that have been ‘home’ in the past. Smith (Citation2002) found that the transnational engagements, including visits, of the Mexican-American second generation peaked during their adolescence, then waned as adult responsibilities increased. Other researchers have argued that country-of-origin visits are experienced differently at different life stages (Zeitlyn Citation2015; Gardner and Mand Citation2012), either finding that interest increases during adolescence (Levitt Citation2002) or decreases with age (King, Christou, and Ahrens Citation2011; Vathi and King Citation2011). These studies rarely point to what actually transpires during visits to cause such changes.

Similarly, various studies document mixed feelings about country-of-origin visits, particularly around identity and belonging (Kibria Citation2002; Louie Citation2006; Mason Citation2004; McMichael et al. Citation2017; Vathi and King Citation2011; Zeitlyn Citation2015). However, such complexity has been attributed to differences between (groups of) young people rather than to complexity and change in individuals’ experiences. For example, McMichael et al. (Citation2017) show that country-of-origin visits can foster a sense of belonging within family networks for some refugee youth and alienation from a national community for others, yet they do not show these conflicting feelings within individuals. Vathi and King (Citation2011) note that, for Albanian-background youth living in the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, gender roles in Albania led to boys and girls holding different associations with their visits there. What remains to be explored is which details of young people’s mobility experiences prompt changes and mixed feelings, and when, how and why such changes occur. As such, a gap exists in our knowledge of how transnational mobility changes migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin, and what transpires during mobility to produce changes over time (across several visits) and space (between different places within one visit).

Viewing mobility up-close: mobility trajectories research

The mobilities turn engendered a processual approach to mobility that focuses on what occurs during the movement of people, objects, and ideas (Urry Citation2002; Sheller and Urry Citation2006). While the mobilities paradigm originally focused on everyday, local mobilities, transnational migration research on mobility trajectories applied this processual approach to migrant mobilities. In doing so, it moved beyond a view of mobility from afar to instead explore the texture of mobility experiences up-close, including the ‘turbulence’ and non-linear components of the migration trajectory (Schapendonk Citation2012; Wissink, Düvell, and Mazzucato Citation2017). Mazzucato (Citation2015) developed the concept of ‘youth mobility trajectories’, meaning young people’s physical moves in time and space and their concomitant family constellations, to study not just the migration move itself but also other forms of mobility, including visits and changes of residence. Van Geel and Mazzucato proposed a typology of transnational youth mobility trajectories, arguing that engaging with the complexity and diversity of such trajectories brings ‘analyses closer to the lived experience of mobile youth’ (Citation2018, 2158). The authors advocate for processual studies of migrant youth mobility, as ‘more research is […] needed on the different kinds of moves that young people engage in, what transpires during these moves, and how this shapes their transnational lives’ (Mazzucato and Van Geel CitationForthcoming, 10, our emphasis). We build on these studies of youth mobility trajectories by exploring the diversity and meaning of migrant youth’s experiences during mobility and how these change their relationships to the country of origin over time and space.

The importance of method

A significant difference between static and processual representations of mobility is methodological. Most second-generation transnationalism and returns studies conduct research in the country of residence about mobility to the country of origin. They often rely on retrospective interviews about past mobility (Van Liempt Citation2011; Kibria Citation2002; Levitt Citation2002; Vathi and King Citation2011), sometimes several years later (Binaisa Citation2011; King, Christou, and Ahrens Citation2011; Louie Citation2006), or use participatory arts to conjure past mobility experiences (Gardner and Mand Citation2012). Some scholars value research in the country of origin, but not necessarily during the mobility studied. For example, second-generation returns studies occasionally conduct interviews about past visits with migrant youth who later relocated to the country of origin, but not during such visits (Binaisa Citation2011; Conway, Potter, and Bernard Citation2009; King, Christou, and Ahrens Citation2011). Similarly, while Levitt argues that understanding the second generation’s transnational orientations, including their physical mobility, requires ‘long-term ethnographic research in the source and destination countries’ (Citation2009, 1225), her descriptions of mobility rely on retrospective interviews with migrants, while her research in countries of origin is conducted with their families. Rare exceptions are Zeitlyn’s (Citation2015) and Bolognani’s (Citation2014) studies of country-of-origin visits by second-generation British Bangladeshis and British Pakistanis, respectively. However, both studies focus on single visits rather than contextualising visits within broader mobility trajectories. In sum, these literatures’ methods are characterized by physical and temporal distance from the actual mobility experiences studied, hindering nuanced representations of the country of origin and of how mobility experiences change relationships to it over time and space.

By contrast, ‘mobile methods’ rely on conducting processual research during mobility (Sheller and Urry Citation2006, 217). Mobile methods were developed to research ‘local’ and transport forms of mobility, such as cycling, car-driving, and navigating neighbourhoods and cities (Büscher and Urry Citation2009; Fincham, McGuinness, and Murray Citation2010) and have been brought into transnational migration research through the use of ‘trajectory ethnographies’ (Schapendonk and Steel Citation2014; Van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018). For example, Schapendonk (Citation2012) followed migrants’ journeys through phone calls, emails and visits en route. Van Geel and Mazzucato (Citation2020) mapped young people’s mobility trajectories and accompanied their visits to Ghana to understand how mobility shaped their educational resilience in The Netherlands.

Unpacking mobility experiences: people, places and moments

Urry’s seminal article on ‘Mobility and Proximity’ (Citation2002) addressed ‘why travel takes place’ (255). In exploring four types of travel – virtual, imaginative, material and corporeal – Urry highlighted the embodied proximity with people, places and moments that physical (or corporeal) mobility enables, which cannot be fully replaced by other forms of travel. Processual mobile methods provide access to these ‘fleeting, multi-sensory, distributed, mobile and multiple’ meanings of mobility as it unfolds (Büscher and Urry Citation2009, 103; Cheung Judge, Blazek, and Esson Citation2020; Sheller and Urry Citation2006).

Some second-generation transnationalism and returns studies acknowledge that country-of-origin visits are ‘significantly experiential’ (Conway, Potter, and Bernard Citation2009, 257; Gardner and Mand Citation2012). Yet their temporal and spatial distance from the studied mobility limits researchers’ ability to adequately capture ‘the centrality of material and bodily experiences of encounters with places’ (McMichael et al. Citation2017, 385), resulting in general descriptions, for example, that ‘the food was too spicy, the weather too hot, and the living conditions unhealthy’ (394).

Urry (Citation2002) recognized that the embodiment of physical travel comprises proximate encounters with people, places and moments (see also Conradson and McKay Citation2007). In this paper, we draw on Urry’s (Citation2002) typology of proximity to explore the factors that constitute migrant youth’s mobility experiences and thus shape their changing relationships to Ghana. Urry outlines three types of proximity that occur during physical travel and make it necessary or desirable: face-to-face, face-the-place, and face-the-moment proximity. Face-to-face emphasises the richly layered in-person interactions during mobility that maintain and shape social relationships. Drawing on Bodon and Molotch’s (Citation1994) analysis of ‘thick’ co-presence, Urry says such interactions include ‘not just words, but indexical expressions, facial gestures, body language, status, voice intonation, pregnant silences, past histories, anticipated conversations and actions, turn-taking practices and so on’ (259). Face-the-place acknowledges the importance of specific locations encountered during mobility, including their embodied and sensorial elements: ‘to meet at a particular house, say, of one’s childhood or visit a particular restaurant or walk along a certain river valley […]. It is only then that we know what a place is really like’ (261). Face-the-moment emphasises the often-obligatory attendance at planned and formal key life events like weddings, funerals, and religious celebrations as ‘a further kind of travel to place, where timing is everything’ (262).

Urry’s typology of proximity is not foreign to research on migration, having been employed to retrospectively study how physical mobility shapes migrants’ relationships to friends and family in the country of origin (Janta, Cohen, and Williams Citation2015; King and Lulle Citation2015). While Urry’s typology has often been applied to understand the motivations for physical mobility, we use his typology to explore what transpires during young people’s visits to Ghana and how the specific and shifting factors that constitute these mobility experiences change their relationships to Ghana over time (across several visits) and space (between different places within one visit). In applying this typology specifically to migrant youth’s visits to the country of origin, a number of necessary modifications emerged from our data and are outlined in the analysis and discussion below.

Research setting and methods

This ethnographic study is part of the MO-TRAYL project (Mobility Trajectories of Young Lives: Life chances of transnational youth in Global South and North) led by Mazzucato (Citation2015). The project investigates the role of transnational mobility in the lives of Ghanaian-background youth in cities in Germany, Belgium, The Netherlands and Ghana, and was approved by Maastricht University’s Ethics Committee.Footnote1 This paper relates to the German case study in Hamburg, for which the first author conducted fieldwork. The second author is the project’s Principal Investigator. The authors collaboratively conducted data analysis and wrote the paper, drawing on insights and approaches developed through the MO-TRAYL team’s collaborative praxis.

Hamburg is home to roughly one fifth of Germany’s Ghanaian community, which dates back to the educational migrants of the 1950s and 1960s and is the second-largest in continental Europe (Mörath Citation2015; Nieswand Citation2008). Approximately 13,200 people of Ghanaian background, including those who migrated from Ghana or have at least one parent who did, were registered in Hamburg in 2017 (Statistikamt Nord Citation2018).

Fieldwork included 12 months in Hamburg and 2 months in Ghana in 2018 and 2019. Twenty research participants (14 female and 6 male) aged 15–25 were recruited through high schools, Ghanaian churches, youth groups, and snowball sampling. Informed consent was obtained processually by reminding participants of the research aims throughout fieldwork and regularly re-confirming their willingness to participate.

Participants were selected based on the following criteria: they (1) are of Ghanaian background, with both of their parents born in Ghana, regardless of their own birthplace (12 were born in Germany and 8 in Ghana); (2) currently reside in Hamburg; (3) attend(ed) secondary school in Hamburg; and (4) have spent time in Ghana, ranging from a single weeks-long visit to several years of residence and schooling. The 20 participants had together made 28 visits to Ghana, ranging from no visits (for 6 of the 8 Ghanaian-born participants) to five visits each. Visits were primarily to see family and friends, but sometimes also included vocational education or tourism. By including youth of migrant background with diverse mobility trajectories – rather than categorising them as ‘first generation’ or ‘second generation’ – we focus on the nature and impact of diverse youth mobility experiences. Our methods further highlight the diversity of experiences by contextualising mobility within our participants’ particular life stage.

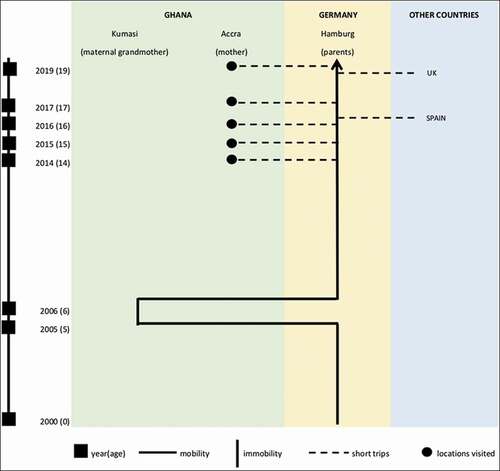

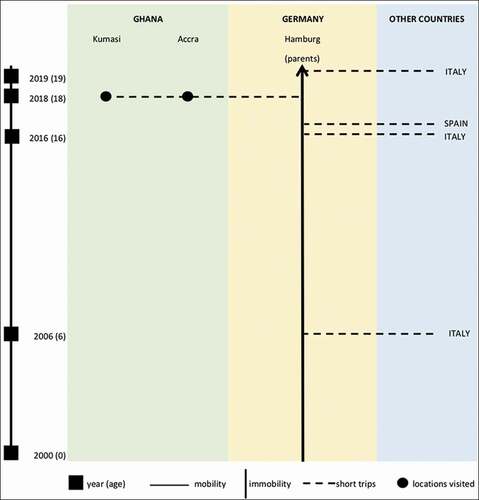

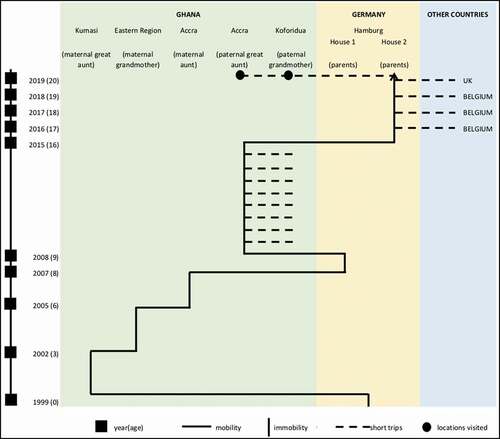

Data for this paper were collected by combining ‘traditional’ ethnographic research methods like participant observation and interviews with ‘mobile methods’ (see Merriman Citation2014 on the benefits of a mixed approach). First, the mobility of all 20 participants was tracked through mobility trajectory mapping (Mazzucato Citation2015; Van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018), which builds on early techniques to capture demographic events within their socio-economic contexts (Antoine, Bry, and Diouf Citation1987) that have been adapted for use within large-scale quantitative migration surveys (Beauchemin Citation2012). Mobility trajectory mapping systematically collects information on a participant’s geographical moves in time and space (including short trips and changes of residence and caregivers, both nationally and internationally), schools attended, and the location of important relatives, resulting in a visualization of their mobility and educational trajectory (Mazzucato et al. CitationForthcoming; see ). These maps were constructed over the course of fieldwork with participants and informed interviews about their various mobility experiences. Second, we followed mobility to Ghana in real-time by accompanying trips physically and following them digitally, both of which are rare in research. Participants’ visits were accompanied physically from one to 19 days and followed digitally mostly through WhatsApp messages and voice memos, which enabled us to gather impressions of and ask questions about visits as they unfolded, rather than relying on retrospective accounts weeks, months or even years later. Five female participants visited Ghana during fieldwork, all of whom were followed physically and digitally to different degrees. Third, we conducted before-and-after interviews with these five participants, meaning we spoke with them before and after visits to Ghana to document the anticipated and actual impacts of these trips on their relationships to the country.

The three cases presented below were chosen because they represent a broad range of mobility trajectories between Ghana and Germany, and their experience of visits to Ghana encompass the variety of dynamics we observed across our entire sample. Further, we used all three mobile methods with them, generating rich data on the topic to exemplify these diverse dynamics. While these methods are ideally used together, the nature of ethnographic research means this is not always possible, and each of the methods enables the collection of relevant data about young people’s mobility experiences and changing relationships to their country of origin.

It is important to acknowledge that mobile methods can shape the very mobility being studied or influence its effects (Boas et al. Citation2021). For example, physically accompanying participants’ visits to Ghana as a ‘guest’ may have influenced the activities undertaken and places visited; and the reflection required by before-and-after interviews could potentially have heightened how participants experienced and recollected a visit to Ghana. Similarly, the potential influence of researchers’ positionality must be acknowledged. The fieldwork researcher is a white woman in her thirties, who grew up transnationally mobile between Australia and Britain and is herself a migrant in The Netherlands. As such, she does not share participants’ age nor national backgrounds, but does share the experience of being transnationally mobile and maintaining transnational networks.

How visits shape changing relationships to Ghana

Although we address each type of proximity from Urry’s (Citation2002) typology separately, our analysis shows that they constitute a nested typology in which each type is interwoven with the others. That is, what is experienced (the moment) has a lot to do with the environment (the place) in which and the people (the face) with whom it is experienced. In each sub-section below, we also introduce modifications to each type of proximity that emerged during our analysis. First, we introduce the participants whose mobility we discuss in detail. Participants chose their own pseudonyms.

Akosua

Akosua (19) was born in Hamburg. At age 5, she lived with her maternal grandmother in Kumasi, Ghana, for 18 months – a time she has vague but unpleasant memories of. Akosua has since made five summer trips to Ghana between the ages of 14 and 19, always staying with her mother, who lives between Hamburg and Ghana’s capital, Accra, where she runs a small business. Akosua describes her four first teenage trips as boring: she felt restricted to her mother’s house and shop with limited social contact and ‘nothing to do.’ She is more positive about her most-recent trip, during which she attended a make-up school full-time for six weeks, got to know her young neighbours, and visited a music festival with friends from Hamburg who also spent their summers in Ghana. During this trip, Ghana opened up to Akosua, and she is now considering returning there to do an FSJ (Freiwilliges Soziales Jahr), a voluntary service year for German students, to ‘get to know Ghana in another way.’ Before this trip, Akosua and I completed her mobility trajectory map and discussed her expectations for the visit. We were in Ghana at the same time and sent each other WhatsApp voice memos every few days. We met in person at Accra Airport on the night we both flew back to Europe. A few weeks later, we conducted a follow-up interview in Hamburg.

Esra

Esra (19) was born in Hamburg and lives with her mother and two sisters. Esra has visited family in Italy a few times and made her first trip to Ghana when she was 17. Before the trip, Esra’s image of Ghana consisted of tropical weather and bumper-to-bumper traffic, gleaned from her mother’s stories of home. She did not know what to expect beyond visiting tourist landmarks and her parents’ hometown and meeting family. During the trip with her mother and sisters, she stayed in relatives’ homes in Accra and Kumasi and visited smaller towns of family significance. Having completed her mobility trajectory map and discussed her expectations before her trip, Esra and I stayed in touch while she was in Ghana through WhatsApp messages and occasional phone calls. I also spent an afternoon with Esra at her aunt’s house in Kumasi, and ran into her and her cousins at a shopping mall in Accra the following week. Months later, we conducted a follow-up interview in Hamburg.

Ella

Ella (20) was born in Hamburg but moved to Ghana before her first birthday. Aged 8, she spent a year in Hamburg, then returned to Ghana until she was 15. In Ghana, Ella attended school in Accra, but spent the holidays in Koforidua with her paternal grandmother, with whom she grew very close. Ella’s summer trip to Ghana aged 19 was her first visit in four years. During the trip with her mother and siblings, she stayed in relatives’ homes in Accra and Koforidua, visited her old school, and caught up with many relatives and friends. The trip was a mixed experience for Ella, including happy reunions and outings as well as painful conflicts and frustrations. I mapped Ella’s mobility slowly throughout fieldwork. I accompanied her 5-week trip to Ghana physically for 19 days and followed it digitally through WhatsApp the rest of the time. We had many conversations about her expectations and plans for the trip beforehand and conducted a follow-up interview a month after returning to Hamburg.

Face-to-face: changing relationships

We consider face-to-face proximity to include not only the maintenance of existing relationships with people residing in the country of origin, as outlined by Urry (Citation2002), but also the beginning of new relationships, the deterioration of existing relationships, and the renewal of relationships from the country of residence in the country of origin. These types of face-to-face proximity all play a role in migrant youth’s visits and changing relationships to Ghana over time and space. We demonstrate each type of face-to-face proximity – the maintenance, beginning, deterioration and renewal of relationships – with examples from our data below.

Akosua’s relationship to Ghana shifted over the course of various visits (see ). From the negative memories of living with her grandmother as a child, to the boredom and isolation of her earlier teenage trips, to the companionship and independence that characterised her recent visit, Ghana has been many things to Akosua. These changes are largely due to the changing relationships that populated Akosua’s visits to Ghana as she grew up. These changes were not caused by a shift in existing relationships with people in Ghana, but rather by the beginning of relationships with other young people in her neighbourhood and at the make-up school. Through conversations with her new friends, Akosua gained connection, a sense of common experience, and new perspective. She found Ghanaians

[…] to be really nice, very, very curious. […] And even when they have little, they are happy. [I]n Ghana, I like that everyone has the same skin colour, and that you just feel at home, because everyone knows the same struggles, [like] with your hair.

The beginning of new relationships can also occur when distant family networks are brought to life through mobility. During Esra’s first trip to Ghana at age 17 (see ), she developed relationships with aunts, uncles and cousins whom she had previously only known from photos and phone calls. When I visited Esra at her aunt’s house in Kumasi, she and her sisters spoke excitedly about the prospect of returning to Ghana the following summer. Months later in Hamburg, Esra spoke of her relationship to Ghana now being closely connected to her newfound family relationships there, so much so that she had decided to postpone returning to Ghana because many relatives had since left to study abroad. ‘We wanted to go to Ghana again this year, but … it’s much more exciting when the whole family is there.’ The temporary suspension of the possibility of face-to-face proximity led to a different relationship and (temporarily) less mobility to Ghana.

Face-to-face proximity in Ghana is not only with local Ghanaians, but also consists of the renewal of relationships from the country of residence in the country of origin. Akosua’s newly positive feelings about Ghana also came from spending time with Ghanaian-background friends from Hamburg who were similarly spending their summers in the country. One highlight of Akosua’s trip was attending a beach music festival on the outskirts of Accra with two friends from Hamburg. With them, she rubbed shoulders with Ghanaian artists, danced in thick crowds, and posted glamorous selfies on social media. Far from the social isolation she had felt in Ghana on previous trips, despite staying in touch with friends in Hamburg through social media, Akosua now gained closeness, comfort and confidence through face-to-face social interactions, which gave her insights into various aspects of life as a young woman in Ghana.

The intense co-presence experienced during visits to Ghana can also lead to the deterioration of relationships. Ella (20) was born in Germany but spent 14 years living in Ghana (see ). Her paternal grandmother was one of her main caregivers there. Since moving to Germany at age 15, Ella stayed in regular contact with her grandmother and their close connection was central to Ella’s relationship to Ghana. Before her 2019 visit, she told me, ‘What I’ve missed the most in Ghana is, I think, my family, especially my grandmother.’ At a birthday party in Hamburg before the trip, I chatted with Ella and her friend Irene. Speaking of trips to Ghana, Irene screwed up her nose and shook her head: she did not want to go back to Ghana. Ella explained to me, ‘It depends on who you are with in Ghana. If she had stayed with my grandmother, she would want to go back.’

During her trip, however, Ella’s relationship with her grandmother deteriorated drastically. Both Ella and her grandmother had changed in the four years since their previous face-to-face contact. Ella was no longer the 15-year-old who had lived there previously, but rather a 19-year-old with four years of experience as a teenager in Germany. Her grandmother’s age (73) made her more dependent on younger relatives, and Ella felt that her supposed ‘menopause’ was making her more irritable. Her grandmother regularly sat in a chair by the living-room doorway, her feet resting in a bucket of warm water, wearing sunglasses to protect her recently operated eyes. From this position, she would call out to the youngsters of the household – ‘Ella!’ ‘Richmond!’ ‘Grace!’ – telling them to fetch her eye drops, prepare the yams for dinner, or fold her washing. Ella resented her grandmother’s expectations that she resume her former roles of cooking, cleaning, and following orders. I regularly observed her rolling her eyes and muttering under her breath. After yet another disparaging comment, I asked Ella, ‘Weren’t you looking forward to seeing your grandmother?’ She replied, ‘Yeah, but now it’s all gone, now it’s a nightmare.’ Months later, Ella reported that she barely spoke to her grandmother anymore.

With my grandmother now, I feel more distant, […] I don’t call her personally because I really had enough [during the visit].

Did you used to call her personally?

Of course! Like three, four times [a week]. She even told me the other time, ‘You don’t call me anymore’. I was just quiet and said nothing.

While Ella’s ‘virtual travel’ (Urry Citation2002) through regular phone calls with her grandmother had maintained their close relationship during four years of distance, their face-to-face encounters during her physical mobility prompted a significant change to it. The damage to their relationship was so severe that, when planning her next trip to Ghana more than a year later, Ella did not inform her grandmother to avoid having to visit her.

Other existing relationships, however, were maintained by Ella’s visit, as in Urry’s (Citation2002) original formulation of face-to-face proximity. She relished the opportunity to spend time with her long-distance boyfriend, cousins and old classmates, including at a wedding, highlighting how face-to-face encounters are facilitated during face-the-moment proximity. These varied experiences point to the shifting terrain of Ella’s relationship to Ghana and the multiple meanings the country holds for her. As such, Ella’s desire to be mobile to Ghana remained consistent, but the reasons for this – the elements that constitute her relationship to Ghana – shifted over time and (as we see below) space.

Face-the-place: changing contexts

As discussed above, much research on migrant youth’s visits depicts a monolithic country of origin. By contrast, face-the-place proximity refers to the specific locations visited during mobility, such as a ‘particular restaurant’ or ‘certain river valley’ (Urry Citation2002, 261). Our data show that broader types of spaces are also important in migrant youth’s experience of place during visits to the country of origin. These broader contexts are made up of various specific places, which together embody certain associations that shape migrant youth’s relationships to Ghana across space. We illustrate each type of face-the-place proximity – specific places and broader spaces – with examples from our data below.

Akosua’s relationship to Ghana changed not only due to the people she spent time with on her trips, as shown above, but also the changing places that formed the background of her visits. In fact, these two elements were intimately connected. On her earlier trips, Akosua had felt restricted to her mother’s shop and house in Accra, limiting her opportunities to build face-to-face social relationships. However, on her most recent trip, her age (19) expanded the places that constituted Akosua’s Ghana, bringing her into contact with new people. At the make-up school she attended in Accra, she met other young women her age with similar interests; she attended a music festival at a popular local beach with friends from Hamburg; and she befriended other young people in her neighbourhood. The specific places that Akosua ‘faced’ during this trip changed what Ghana meant for her, consequently changing her relationship to the country. Places were no longer boring and limited, but diverse and multiple: these professional, recreational, and communal spaces gave her new windows onto various facets of Ghana and the possibilities they offered her; for example, the opportunity to volunteer and ‘get to know Ghana in another way.’

Ella’s worsening relationship with her grandmother was also inseparable from the physical environment in which it played out, which contrasted to other spaces she visited in Ghana. However, in Ella’s case, we see that specific places together formed broader spaces that held contrasting associations for her: the two cities of Accra, the nation’s bustling capital of 2.5 million residents, and Koforidua, a quiet, green city 90 minutes away. In Accra, Ella stayed in the house of her young, entrepreneurial uncle and was driven around in the family 4-Wheel-Drive by her ‘cool’ cousin, Kobi, her ‘favourite person on this trip’. In Accra, Ella seemed confident, playful, and independent. She spent her time visiting family and friends, shopping, and going to the mall, cinema, and hotel pools – the objective was ‘to chill, relax and lead my best life’. In Koforidua, by contrast, she commonly complained of being bored and frustrated. Exacerbating this tension was the family’s nervousness about Ella ‘roaming’ in public, due to a recent spate of kidnappings. Consequently, she was forbidden to leave the house alone and her days were filled with long waits for a ride into town, or repetitive visits between her grandmother’s home, the market and church. The city as a whole came to represent Ella’s frustration, boredom and lack of independence. Despite her initial enthusiasm to travel there, Ella soon tired of Koforidua and wanted to return to Accra. Her relationships, especially with her grandmother, foregrounded her face-the-place proximity during this trip. Lounging on her bed in Koforidua one hot afternoon, Ella whispered, ‘Laura, I’m pissed, everyone in this house is disturbing me, I want to go back.’ ‘To where?’ ‘Accra … I’m not enjoying Ghana.’ The frustrations of Koforidua came to symbolise Ella’s experience of and relationship to Ghana while she was there, though she acknowledged that, with a change of place, Ghana would become something different yet again.

The experience of place for Esra, who had imagined Ghana as tropical and congested, was defined by the different meanings that public and private spaces came to hold during her first visit. In public among strangers, the naturally shy Esra felt constantly observed and very uncomfortable. On a visit to her parents’ rural hometown, she recalled people lining up to watch their car arrive. ‘I felt like Beyoncé’, she grimaced, ‘It was so uncomfortable, really weird.’ Her reception in public spaces – of admiration, but distance – emphasised Esra’s feelings of foreignness among local Ghanaians. I observed this when I visited her in Ghana’s second major city, Kumasi. As we strolled through the neighbourhood, Esra walked with her hands in her pockets, shoulders hunched, and her head down, avoiding eye contact with curious pedestrians. I asked her if she felt stared at right now. ‘Yeah, a bit,’ she replied, explaining that she coped with her discomfort by avoiding eye contact with people on the street.

However, in private spaces, like relatives’ homes, Ghana took on a different meaning. In such spaces, Esra felt comfortable and connected to family. On my visit to her aunt’s house, Esra showed me photos and paintings of her relatives on the living-room walls and introduced me to several people (translating fluently between German and Twi). Back in Hamburg, Esra reflected on how visiting private family-related places – and their interconnections with family relationships – had shaped the meaning of Ghana for her:

The focus of this trip was really the family, that I understood a few things … I could see what the foundations of the family were […] Before I was like, ‘Whatever, I know my mum comes from Ghana’, that was it. But now I know where my mother was in Ghana, where my father was in Ghana […] And it’s more real [in person] than when you hear [about] it. I think that’s what I brought: no longer these open questions; now it’s like, okay, I have my answers, everything’s good.

Far from being a monolithic country, Esra’s Ghana was composed of various public and private spaces, representing different aspects of her relationship to the country.

Face-the-moment: changing events

The places that constituted participants’ visits to Ghana were not only backdrops to relationships but were also the stages on which impactful moments of their mobility played out. The original formulation of face-the-moment proximity refers to planned, formal and ‘live’ events at which travellers’ presence is specifically timed to meet a familial or social obligation, like weddings, funerals, and religious celebrations. We found that two other types of ‘moment’ also shape our participants’ relationships to Ghana: planned but informal events and unanticipated encounters. These three types of key moments – planned and formal, planned but informal, and unanticipated – are intricately interwoven with people and places. Each type is explained with an example from our data below.

The first type of key moment is the planned, formal event that Urry (Citation2002) describes. During her trip, Ella attended the wedding of Blessing, whom Ella considered a ‘sister’ because she worked for years in Ella’s grandmother’s household. Ella’s participation in the wedding allowed her to rekindle relationships and fulfil social obligations. Blessing asked Ella to be a bridesmaid and to manage the gift table, tasks Ella interpreted as a great responsibility and sign of trust. Before her trip to Ghana, Ella offered to buy Blessing’s bridal shoes in Hamburg. At the wedding itself, I observed Ella reconnect with the other bridesmaids, whom she knew from childhood, and receive social recognition of her generosity (for paying for a drinks stand at the wedding reception), her VIP status (as a bridesmaid), and her own romantic relationship (another bridesmaid teased, ‘Who will be the next bride, Ella?’). Not only did this event provide the opportunity to maintain social relationships and fulfil social obligations (Urry Citation2002), but it also represented change in Ella’s relationship to Ghana, because she could demonstrate her maturity to her social network by now fulfilling these obligations independent of her parents. Back in Hamburg, Ella reflected on how ‘the comment that people gave me [in Ghana] was, […] I’ve really changed into a woman. […] People said I’ve grown, I’ve become more independent, more serious with life’. Planned and formal events like Blessing’s wedding gave Ella the platform to show that her relationship to Ghana had changed over time: she had left Ghana a girl and returned a woman.

Esra’s visit to her parents’ hometown exemplifies the second type of key moment: planned but informal events. When I visited Esra in Ghana, she and her two sisters vividly described this visit they had made days earlier. They had seen their parents’ family houses and school, met their parents’ old classmates, and visited the graves of their father (who died when Esra was a young child) and other relatives. Esra moved closer on the couch to show me photos of the graves on her phone, including that of her great-grandmother Esra, for whom she was named. The sisters chatted animatedly about the mix of poor local and rich migrant houses, their efforts to clear overgrown shrubs from the graves, and the fact that villagers still recognised their mother after so many years. Esra’s understanding of her family history had a strong connection to place and relationships (as shown above), and was exemplified by this visit to her parents’ hometown, a planned but informal event that crystallised these meanings of Ghana.

The third and final type of key moment is unanticipated encounters. Although such moments are unplanned and unpredictable, they can nevertheless shape young people’s relationships to Ghana in significant ways. A key moment on Akosua’s trip, which she described to me weeks later in Hamburg, provides an instructive example. While sharing a taxi one day, Akosua and her mother bickered over Akosua’s desire for more independence. Much to Akosua’s shock, their driver suddenly intervened.

All of a sudden, the taxi driver – who we didn’t know – yells at me, ‘Be quiet! Be quiet! You are so disrespectful! Shut up!’ I was like, ‘Huh?’ I didn’t understand it. The taxi driver [said]: ‘Foreign kids are so rude! Disrespectful! No respect!’

Addressing Akosua’s mother, the driver continued:

Madam, […] I know how you feel, I’m also a father, I have seven kids, and it’s so hard to let them go. Don’t let them out, don’t give them the chance!

Akosua described her shock: ‘I was sad, I cried, I didn’t say anything. […] For the next two days, I cried.’ This example demonstrates how the constellation of shifting people, places and moments can change migrant youth’s relationships to Ghana across space during a single visit. Places like the make-up school and her relationships with neighbours, classmates, and friends from Hamburg represented parts of Ghana where Akosua gained a newfound confidence and independence. Impactful moments in other contexts, however, like this unanticipated encounter with the taxi driver, represented a side of Ghana where Akosua’s confidence was shaken and her independence far more limited.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have studied the visits to Ghana of Ghanaian-background youth living in Germany. In doing so, we have shown that migrant youth’s relationships to their or their parents’ country of origin are not static and singular, but rather changing and multiple, due to their diverse mobility experiences over time (across several visits) and space (between different places within one visit). By engaging with migrant youth’s mobility experiences processually, we gain a deeper understanding of how transnational mobility shapes their lives in dynamic and evolving ways. Here, we discuss two main conclusions and contributions of our study – the first theoretical and the second methodological – before concluding.

Our theoretical contribution regards the importance of the various ‘moving parts’ of mobility experiences and how they influence migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin. In much literature on second-generation transnationalism and returns, meanings of mobility are depicted in relation to a monolithic country of origin. However, migrant youth’s visits to Ghana are made up of relationships with specific people, time spent in particular places, and experiences of certain moments. Together, the shifting factors that constitute mobility experiences change the meanings of such trips and thus change migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin over time and space.

When one begins to look at the details rather than at retrospective narratives of mobility, the reality can seem overwhelmingly messy. Urry’s (Citation2002) typology of proximity provides the framework for our analysis, untangling experiences of lived mobility into discrete parts. His three ‘bases of co-presence’ – face-to-face, face-the-place and face-the-moment proximity – provide windows onto the interconnected relationships, locations and events that together make up the sensorial, embodied and emotional experiences of mobility that shape its changing meanings. In applying Urry’s typology of proximity to our data on migrant youth’s visits to Ghana, three further articulations of the typology emerged.

First, we show that people, places and moments are made up of and embedded within each other. Urry (Citation2002) described these three bases of co-presence separately, while Sheller and Urry (Citation2006) theorized the ‘complex relationality’ between them (see also Hannam, Sheller, and Urry Citation2006; Mason Citation2004). In our study of young people’s mobility trajectories, we show empirically how this complex relationality shapes migrant youth’s changing relationships with the country of origin over time and space. Relationships play out in specific places and are composed of particular moments; places are populated by people and set the stage for events; and encounters include certain people meeting in precise locations. Especially when we consider the embodied aspects of mobility, we see that people, places and moments become inseparable. For example, the experience of a deteriorating relationship is infused with memories of the place in which the relationship was embedded and the particular moments that composed the fall-out. As such, Urry’s (Citation2002) typology of proximity is useful not as separate bases of co-presence, but as a way to study the complex relationality of people, places and moments encountered during mobility.

Second, while mobilities research has shown that places are dynamic and on the move (Adey Citation2006; Sheller and Urry Citation2006), we show that young people’s relationships to the country of origin are also on the move because the factors that constitute their mobility change: people age, places transform, and events are unpredictable. Various studies have pointed to the dynamism of life stages to explain changes in migrant youth’s relationships to the country of origin over time (King, Christou, and Ahrens Citation2011; Levitt Citation2002; Smith Citation2002). Yet equally important is the dynamism of the mobility experience itself, which interacts with the developing young person to produce changing relationships to the country of origin.

Third, we add new elements to each type of proximity. The original formulation of face-to-face focuses on the role of physical proximity in maintaining existing relationships with people in the place visited. We add the beginning and deterioration of relationships, and the renewal of relationships from the country of residence in the country of origin. These changes continually reshape the social fabric of young people’s experiences of Ghana. Visits can provide opportunities for young people to establish new relationships; similarly, they can damage relationships: as described by Mason, visits can be socially ‘risky business’ because they can ‘emphasise differences as much as generate shared understanding’ (Citation2004, 427). Finally, visits can provide a new context in which to connect with others from young people’s transnational networks. While face-the-place originally refers to specific places visited, we show that broader spaces – for example, the contrasting environments of public and private spaces or of different cities – also hold particular associations for migrant youth and therefore shape important parts of their relationships to Ghana. Located between the specific locations of Urry’s original typology (Citation2002) and the monolithic depiction of countries of origin of much second-generation transnationalism and returns research, these broader spaces represent the different sides of Ghana that our participants experience and develop mixed feelings towards. While face-the-moment for Urry indicated planned and formal life events that ‘cannot be “missed”’ and which ‘set up enormous demands for mobility at very specific moments’ (Citation2002, 262), we supplement them with planned but informal events and unanticipated encounters. So, beyond key life events like weddings and funerals, they also include experiences such as a personal pilgrimage to a meaningful place or an unexpected yet impactful confrontation. In the analysis above, we show that such moments play an important role in shaping our participants’ changing relationships to Ghana. With these modifications, Urry’s typology of proximity comes closer to capturing the ways in which the mobility experiences of migrant youth shape their changing relationships to the country of origin.

A mobility trajectories approach to the study of changing relationships to the country of origin also has important methodological implications. As described above, second-generation transnationalism and returns literatures have largely studied mobility from afar, relying mostly on research in the country of residence. These studies provide interesting insights into the role of mobility in migrant youth transnationalism, but their exclusion of or distance from mobility experiences tends to produce generalised depictions of both the country of origin and young people’s mobility, flattening out differences across time and space and attributing change to macro-level contexts and life stages. While sharing a thematic interest in people’s physical movement with mobilities research, these literatures largely do not employ mobile methods (D’Andrea, Ciolfi, and Gray Citation2011).

Bridging this gap, the use of mobile methods within multi-sited ethnographic research allows us to study these changing and complex meanings up-close and enables ‘a focus on embodied practices, sensations and the material aspects of mobilities’ (Boas et al. Citation2021, 143). We employed three main techniques that combine traditional ethnographic methods of participant observation and interviews with mobile methods (Merriman Citation2014). These include mobility trajectory mapping, following mobility in real-time, and before-and-after interviewing. These methods enabled us to examine the nature and meaning of individual mobility experiences within broader mobility trajectories and how these changed over time and space, rather than collapsing several mobility experiences into one generalised narrative. They also allowed us to develop nuanced understandings of how visits shape changing relationships to the country of origin by capturing the meaning-making process in action and accessing sensorial, embodied and emotional information that is likely to be glossed over in retrospective narratives.

One final point on the importance of studying youth mobility trajectories is pertinent. We have shown the importance of mobility experiences in shaping changing relationships to the country of origin for migrant youth with diverse mobility trajectories. The participants featured in this paper were all born in Germany, and as such would be classified as ‘second generation’, but they have very different mobility trajectories: Ella lived for 14 years in Ghana and has made one visit to the country; Akosua lived for 18 months in Ghana and has visited five times; and Esra has made a single trip to Ghana. The visits of Akosua, Esra and Ella all include shifting constellations of people, places and moments that shape their changing relationships to Ghana over time and space in different ways. Looking beyond migrant-generation categories, and instead exploring the detail of young people’s mobility experiences, brings us closer to understanding the diverse impacts of physical mobility among migrant youth.

The limitations of our study suggest fruitful avenues for future research. First, the participants who travelled to Ghana during the fieldwork period were all female. Further research could explore how gender shapes migrant youth’s mobility experiences and relationships to the country of origin (cf. Vathi and King Citation2011). Second, studies could investigate the consequences of transnational mobility experiences and changing relationships to the country of origin for the lives of migrant youth in their countries of residence, on which there exists very little research (Van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2020).

While migrant youth engage in diverse mobilities that sustain virtual, imaginative and material connections with their countries of origin, the embodied nature of physical mobility plays a unique role in shaping their relationships to the country of origin over time and space. Just as young people change as they grow up, so do their mobility experiences – the specific and shifting people, places and moments that make up their visits to the country of origin. We argue that taking mobility seriously requires analytical and methodological approaches that make visible what transpires during physical mobility and how mobility experiences change both over time and space. Such processual approaches bring us closer to fully accounting for the role of mobility in the lives of transnational migrant youth.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sara Fürstenau, the MO-TRAYL team, and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Maastricht University’s Ethical Review Committee Inner City, reference number ERCIC_053_15_11_2017.

References

- Adey, P. 2006. “If Mobility Is Everything Then It Is Nothing: Towards a Relational Politics of (Im)mobilities.” Mobilities 1 (1): 75–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100500489080.

- Antoine, P., X. Bry, and P. D. Diouf. 1987. “The ‘Ageven’ Record: A Tool for the Collection of Retrospective Data.” Survey Methodology 13 (2): 163–171.

- Beauchemin, C. 2012. “Migrations between Africa and Europe: Rationale for a Survey Design.” MAFE Methodological Note 5. Paris: INED, 45.

- Binaisa, N. 2011. “Negotiating ‘Belonging’ to the Ancestral ‘Homeland’: Ugandan Refugee Descendents ‘Return’.” Mobilities 6 (4): 519–534. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.603945.

- Boas, I., J. Schapendonk, S. Blondin, and A. Pas. 2021. “Methods as Moving Ground: Reflections on the ‘Doings’ of Mobile Methodologies.” Social Inclusion 8 (4): 136–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v8i4.3326.

- Bodon, D., and H. L. Molotch. 1994. “The Compulsion to Proximity.” In Nowhere: Space, Time and Modernity, edited by R. Friedland and D. Boden, 257–286. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bolognani, M. 2014. “Visits to the Country of Origin: How Second-generation British Pakistanis Shape Transnational Identity and Maintain Power Asymmetries.” Global Networks 14 (1): 103–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12015.

- Büscher, M., and J. Urry. 2009. “Mobile Methods and the Empirical.” European Journal of Social Theory 12 (1): 99–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431008099642.

- Cheung Judge, R., M. Blazek, and J. Esson. 2020. “Editorial: Transnational Youth Mobilities: Emotions, Inequities, and Temporalities”. Population, Space and Place 26(6). Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2307.

- Conradson, D., and D. McKay. 2007. “Translocal Subjectivities: Mobility, Connection, Emotion.” Mobilities 2 (2): 167–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100701381524.

- Conway, D., R. B. Potter, and G. S. Bernard. 2009. “Repetitive Visiting as a Pre‐return Transnational Strategy among Youthful Trinidadian Returnees.” Mobilities 4 (2): 249–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100902906707.

- D’Andrea, A., L. Ciolfi, and B. Gray. 2011. “Methodological Challenges and Innovations in Mobilities Research.” Mobilities 6 (2): 149–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.552769.

- Fincham, B., M. McGuinness, and L. Murray, eds. 2010. Mobile Methodologies. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gardner, K., and K. Mand. 2012. “‘My Away Is Here’: Place, Emplacement and Mobility Amongst British Bengali Children.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (6): 969–986. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.677177.

- Haikkola, L. 2011. “Making Connections: Second-generation Children and the Transnational Field of Relations.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (8): 1201–1217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.590925.

- Hannam, K., M. Sheller, and J. Urry. 2006. “Editorial: Mobilities, Immobilities and Moorings.” Mobilities 1 (1): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100500489189.

- Janta, H., S. A. Cohen, and A. M. Williams. 2015. “Rethinking Visiting Friends and Relatives Mobilities.” Population, Space and Place 21 (7): 585–598. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1914.

- Kibria, N. 2002. “Of Blood, Belonging, and Homeland Trips: Transnationalism and Identity among Second-generation Chinese and Korean Americans.” In The Changing Face of Home: The Transnational Lives of the Second Generation, edited by P. Levitt and M. C. Waters, 295–311. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- King, R., A. Christou, and J. Ahrens. 2011. “‘Diverse Mobilities’: Second-Generation Greek-Germans Engage with the Homeland as Children and as Adults.” Mobilities 6 (4): 483–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.603943.

- King, R., and A. Lulle. 2015. “Rhythmic Island: Latvian Migrants in Guernsey and Their Enfolded Patterns of Space-time Mobility.” Population, Space and Place 21 (7): 599–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1915.

- Levitt, P. 2002. “The Ties that Change: Relations to the Ancestral Home over the Life Cycle.” In The Changing Face of Home: The Transnational Lives of the Second Generation, edited by P. Levitt and M. C. Waters, 123–144. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Levitt, P. 2009. “Roots and Routes: Understanding the Lives of the Second Generation Transnationally.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (7): 1225–1242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903006309.

- Levitt, P., and M. C. Waters, eds. 2002. The Changing Face of Home: The Transnational Lives of the Second Generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Louie, V. 2006. “Second-generation Pessimism and Optimism: How Chinese and Dominicans Understand Education and Mobility through Ethnic and Transnational Orientations.” International Migration Review 40 (3): 537–572. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00035.x.

- Madianou, M., and D. Miller. 2011. “Mobile Phone Parenting: Reconfiguring Relationships between Filipina Migrant Mothers and Their Left-behind Children.” New Media & Society 13 (3): 457–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810393903.

- Mason, J. 2004. “Managing Kinship over Long Distances: The Significance of ‘The Visit’.” Social Policy and Society 3 (4): 421–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746404002052.

- Mazzucato, V. 2015. “Mobility Trajectories of Young Lives: Life Chances of Transnational Youths in Global South and North (MO-TRAYL).” ERC Consolidator Grant No. 682982.

- Mazzucato, V., G. Akom Ankobrey, S. Anschütz, L. J. Ogden, and O. E. Osei. Forthcoming. “Mobility Trajectory Mapping for Researching the Lives and Learning Experiences of Transnational Youth.” In Innovative Migration Methodologies, edited by C. Magno, J. New, S. Rodriguez, and J. Kowalczyk

- Mazzucato, V., and J. Van Geel. Forthcoming. “Transnational Young People: Growing up and Being Active in a Transnational Social Field.” In Handbook of Transnationalism, edited by B. Yeoh and F. Collins. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- McMichael, C., C. Nunn, S. Gifford, and I. Correa-Velez. 2017. “Return Visits and Belonging to Countries of Origin among Young People from Refugee Backgrounds.” Global Networks 17 (3): 382–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12147.

- Merriman, P. 2014. “Rethinking Mobile Methods.” Mobilities 9 (2): 167–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.784540.

- Mörath, V. 2015. The Ghanaian Diaspora in Germany. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

- Nieswand, B. 2008. “Ghanaian Migrants in Germany and the Social Construction of Diaspora.” African Diaspora 1 (1–2): 28–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/187254608X346051.

- OECD/European Union. 2015. Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2015: Settling In. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Robertson, S., A. Harris, and L. Baldassar. 2018. “Mobile Transitions: A Conceptual Framework for Researching A Generation on the Move.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (2): 2013–2217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1362101.

- Schapendonk, J. 2012. “Turbulent Trajectories: African Migrants on Their Way to the European Union.” Societies 2 (2): 27–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/soc2020027.

- Schapendonk, J., and G. Steel. 2014. “Following Migrant Trajectories: The Im/mobility of Sub-Saharan Africans En Route to the European Union.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (2): 262–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.862135.

- Schimmer, P., and F. Van Tubergen. 2014. “Transnationalism and Ethnic Identification among Adolescent Children of Immigrants in the Netherlands, Germany, England, and Sweden.” International Migration Review 48 (3): 680–709. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12084.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment & Planning A 38 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a37268.

- Smith, R. C. 2002. “Life Course, Generation, and Social Location as Factors Shaping Second-generation Transnational Life.” In The Changing Face of Home: The Transnational Lives of the Second Generation, edited by P. Levitt and M. C. Waters, 145–167. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Statistikamt Nord. 2018. “Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund in den Hamburger Stadtteilen Ende 2017. [Population with Migration Background in Hamburg Neighbourhoods at the End of 2017.]. Statistik Informiert 3, 23 August. https://www.statistik-nord.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Statistik_informiert_SPEZIAL/SI_SPEZIAL_III_2018.pdf

- Urry, J. 2002. “Mobility and Proximity.” Sociology 36 (2): 255–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038502036002002.

- Van Geel, J., and V. Mazzucato. 2018. “Conceptualising Youth Mobility Trajectories: Thinking Beyond Conventional Categories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13): 2144–2162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1409107.

- Van Geel, J., and V. Mazzucato. 2020. “Building Educational Resilience through Transnational Mobility Trajectories: Young People between Ghana and the Netherlands.” Young29(2): 119-136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308820940184.

- Van Liempt, I. 2011. “Young Dutch Somalis in the UK: Citizenship, Identities and Belonging in a Transnational Triangle.” Mobilities 6 (4): 569–583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.603948.

- Vathi, Z., and R. King. 2011. “Return Visits of the Young Albanian Second Generation in Europe: Contrasting Themes and Comparative Host-country Perspectives.” Mobilities 6 (4): 503–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.603944.

- Wissink, M., F. Düvell, and V. Mazzucato. 2017. “The Evolution of Migration Trajectories of sub-Saharan African Migrants in Turkey and Greece: The Role of Changing Social Networks and Critical Events.” Geoforum 116: 282-291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.12.004.

- Zeitlyn, B. 2015. Transnational Childhoods: British Bangladeshis, Identities and Social Change. Hampshire: Springer.