ABSTRACT

Contemporary migration infrastructures commonly reflect imaginaries of technological solutionism. Fantasies of efficient ordering, administrating and limiting of refugee bodies in space and time through migration infrastructures are distinctive, but not novel as they draw on long historical lineages. Drawing on archival records, we present a case-study on post-World-War-II refugee encampments. By highlighting the deeply historical role of media in migration governance, i.e. the act of mediation through technological infrastructuring, we seek to bring together the fields of migration studies and media studies. We argue that this cross-fertilization helps to historically untangle power dimensions, inherent workings, as well as human experiences imbued in the tech-based management of migration ‘crises’. Uncovering historical underpinnings of digitalized asylum regimes through the prism of media infrastructures, and socio-technical imaginaries surrounding them, points at continuities and genealogies of containing and managing people in time and space, reaching into technologies of colonial and fascist projects. We thus seek to explore the assumptions that drive the build-up of migration and media infrastructures: How are migrants, camps, media and their infrastructural interrelations imagined? Which cultural horizons are reflected in technologies, which functions are imagined for whom, and how are utilitarian ideas about humanitarianism and migration control embedded?

1. Introduction

Across the globe, refugee governance and humanitarian actors are experimenting with ‘efficient’, ‘effective’, yet oppressive and impinging, technology-driven ‘solutions’ to manage migration. Across the humanitarianism-securitization nexus (Pallister‐Wilkins Citation2017), as a response to so-called ‘refugee crisis’ situations, refugee camps and borders are effectively rendered into ‘technology testing grounds’ (Molnar Citation2020; Metcalfe and Dencik Citation2019). Advanced experimental technologies of registering, profiling, risk-assessment, decision-making, surveillance, food and service provision are tested on populations, who often have no choice nor say over this process, realizing a techno-utopian ideology of ‘humanitarian neophilia’ (Scott-Smith Citation2016). Experiments include the mobilization of ‘Blockchain for Zero Hunger’ which promise to strengthen self-reliance of inhabitants in refugee camps in Jordan (WFP Innovation Accelerator Citation2020), and the embrace of ‘smart cities’ approaches based on computational design and mobile payments to ‘reimagine refugee camps’ from Kenya to Luxembourg (Nathan Citation2017; Daher et al. Citation2017). We argue these developments can be untangled and historicized by addressing them as cross-fertilizations of migration infrastructures and media infrastructures.

With the term ‘migration infrastructures’, migration researchers refer to the assemblages of human and non-human actors that mutually constitute migration management (e.g. Xiang and Lindquist Citation2014; Lin et al. Citation2017; Dijstelbloem Citation2020). In their realization, migration infrastructures reflect a distinctive historical, socio-cultural, economic and political conjuncture. Underlying technological developments not only reflect a moment in migration governance, they also reflect a distinctive moment in media history. Therefore, migration infrastructures are inseparably tied to ‘media infrastructures’ (Parks Citation2015; Holt and Vonderau Citation2015; Mattern Citation2016). Media and communication researchers use this concept to scrutinize the technological materialities of ‘situated socio-technical systems’ (Parks and Starosielski Citation2015, 4), which undergird media and practices of mediation: i.e. the circulation and storing of meaning, data, information, content and communication practices. Here, media can be broadly understood as materialities, technologies and techniques that constitute ‘enabling environments’ (Peters Citation2015), beyond being channels of content distribution, and instead organize and manipulate space and time, and thus obtain infrastructural power (cf. also Vismann Citation2000; Mattern Citation2016). Focusing on migration infrastructures through the lens of media infrastructures arguably situates them as yet another media-technological realization and materialization of refugee regimes.

Our argument in this paper is two-fold. First, while media infrastructures – the more promising, disruptive and innovative the better – are deployed to realize political aspirations of migration management, this techno-solutionist development of migration infrastructures also becomes the site of imagination itself: visions of protecting, provisioning and managing people’s mobility in time and space are projected on media-technological materialities. Secondly, we demonstrate that the recent upsurge of technological solutionism observable in migration infrastructural innovation is nothing new. As Collins (Citation2020, 8) notes, ‘[w]hile much research on migration industries and infrastructure has to date focused on contemporary patterns, many of their functions and effects have substantial historical lineages that have yet to be sufficiently examined’. We seek to provide a first intervention here. Through an analysis of empirical archival sources from post-World-War-II Germany, this article shows how historical migration infrastructures already projected specific trust and desires on media technologies. Outsourced to seemingly neutral (pre-digital) technologies such as paper-based registration files, food cards, stamps and filing cabinets, solutions always already served to distinguish and rank populations into neat categories of desirable/undesirable subjects, needed to establish parameters to correspondingly curtail the mobilities of these ordered subjects into a delimited time and space. While the deployment of sorting mechanisms in migrant infrastructures has remained unchanged, in the evolvement of media technologies we witness a shift from infrastructuring bodies to infrastructuring biographies.

Throughout the 20th century, institutions, practices and discourses of governing migration and irregular mobility have evolved into what is called the ‘modern refugee regime’ (Gatrell Citation2013). Forced migrations in the aftermath of both world wars have resulted in global initiatives, documents and institutions to recognize, administrate, govern, and cater for ‘the refugee’ subject; mainly manifested today in UNHCR and the ‘1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees’ (usually called Geneva Convention), but also in national asylum legislations, access to citizenship, and border protection mechanisms. Media technologies have played key roles throughout the historical trajectory of migration infrastructural development. The historical and contemporary process of registering, sorting and ranking mobile subjects as refugees, displaced persons and/or forced migrants reflects the inherent interrelatedness of migration and media infrastructures. Registering mobile bodies for the purpose of sorting on the basis of particular imaginaries and parameters of deservingness and non-deservingness requires distinctive administrative procedures and forms of documentation, always entangled with practices of mediation and underlying media infrastructures. Mobile subjects can only obtain any given status, any form of recognition, by accepting to make their bodies and biographical trajectories legible and codable through media and migration infrastructures. In their extreme, when migration infrastructures prioritize securitization over human rights – resulting, for example, in Europe being currently the deadliest migration destiny for irregular migrants in the world – media infrastructures can become complicit in the necropolitics of ‘infrastructural brutalism’ (Truscello Citation2020), which is reflective of ‘an aesthetic, a political program, and a psychological and material condition’ (15).

By highlighting the deeply historical role of media, i.e. the act of mediating performed through media technological infrastructuring, in migration governance, we seek to bring productively together the fields of migration studies and media studies. We argue that this cross-fertilization helps to explore historically and to untangle power dimensions, inherent workings, as well as human experiences imbued in the tech-based management of migration ‘crises’. Uncovering the historical underpinnings of digitalized asylum regimes through the prism of media infrastructures points at continuities, critical junctures and genealogies of managing people in time and space, reaching all the way into technologies of colonial and fascist projects. The article is structured as follows: first we review and connect literature on infrastructure in the fields of media and migration studies, foregrounding the role of the imagination. Secondly, we discuss how we take up a media history perspective to research migration infrastructures. The empirical section presents case studies on bureaucratic paper imaginaries of migration governance in post-war Germany, specifically administration of camps.

2. Imagining migration and media infrastructures

The specific scrutiny of how migration infrastructures operate in relation to and incorporate media infrastructures “allows” for the development of a multi-perspectival understanding of infrastructures in the lives of migrant subjects. Although building on similar groundwork, in pursuing specific orientations, migration infrastructure and media infrastructure scholarship have developed in different directions. In reviewing literature on migration and media infrastructures, at least three important commonalities and shared commitments to the study of infrastructures can be highlighted:

1) An infrastructural perspective is oriented towards scrutinizing taken-for granted systems and assemblages. The metaphor of the black box is commonly used in both discussions. This is a term originating from engineering, now taken up in infrastructure studies in a call to action to move from only addressing input and output characteristics of technological processes to uncover and make transparent their mundane, underlying inner logic and workings, which can have ‘possibility-fixing’ (Peters Citation2015, 21) characteristics. In studies on media infrastructure, the term is used to uncover the invisible material interiority of technical objects and processes (Parks Citation2009), and to reflect on the aesthetic, political, cultural and economic rationales covered by the ‘black-boxed-ness’ (Holt and Vonderau Citation2015, 74) of radios, televisions, the internet and data centers, but also deeply historical media such as lists, documents and forms, card catalogs, or writing and the inscription of bodies and materials. In migration infrastructure scholarship, opening the ‘black box’ of migration (Lindquist, Xiang, and Yeoh Citation2012; Lin et al. Citation2017) refers to teasing out processes like migrant recruitment, documentation and the broader political economy of transnational mobility. The black box metaphor serves as a reminder that infrastructures are purposefully rendered invisible to subjects who are not in charge of their design and aims (Parks Citation2009). This invisibility is problematic, because it hides power dynamics, makes forms of exclusion and exploitation possible and limits means to accountability or contestation. However, the black-boxed character is often left unscrutinized as a result of ‘infrastructural fetishism’ (Dalakoglou Citation2016, 828) and solutionist desires and fantasies projected on technology. It is our contention that media infrastructures – with their particular imagined promises of efficiency, objectivity and inevitability – further compound the black box effect of migration infrastructures.

2) Migration and media infrastructure scholars are both attentive to how infrastructure functions as an apparatus of governmentality in their maintenance of power geometries. Two shared points of reference can be discerned: Langdon Winner’s (Citation1980) classic piece ‘Do artifacts have politics?’, foregrounded the uneven infrastructural politics of transportation in New York City: tunnels were designed for automobiles used by white upper-class New Yorkers, and not for autobuses, so non-affluent African-American populations without access to cars could not visit parks. Brian Larkin’s (Citation2013) understanding of the ‘politics and poetics’ of infrastructures is a second shared reference point. With politics, Larkin (Citation2013) addresses the governmentality of infrastructures emerging from the interrelationships of political rationalities, administrative techniques and techno-material systems. With poetics, Larkin (Citation2013) refers to the distinctive forms and aesthetics of infrastructures: representations are variously experienced, embodied, affecting, often providing a sense of progress and development, while being oppressive to others (cf. Molnar Citation2020). Social media and digital governmental databases reflect a ‘new infrastructure for movement and control’, which enables connectivity with loved ones and family members across borders, and sharing of information (Latonero and Kift Citation2018, 1). However, in parallel, datafication is embraced by governments to increase surveillance and control over refugee movements and identity (ibid). Power and representation shape migration infrastructures as they are always reductionist in different ways and thereby unjust – consider, for example, how passports have evolved from a symbolic document to facilitate movement to a tool part of a ‘smart’ security system that enables smooth border crossing for some privileged subjects and limits it for most (Glouftsios Citation2020).

3) Building on Susan Leigh Star’s (Citation1999) call to approach ‘infrastructuring’ as a verb, and as a ‘fundamentally relational concept’ (380), infrastructures are commonly understood as a continuous dynamic assemblage, actively mutually constituted through top-down and bottom-up processes and practices. ‘Infrastructuring’ as a verb draws our attention to the active, constant rearrangement of human and non-human actors that lead to the infrastructural production of migration, which happens in conjunction with the infrastructural production of media technology. Infrastructural build-up in, for example, refugee camps is thus never to be seen as a ‘force majeure’. Rather, such tech experimentation ‘is not the result of an autonomously unfolding process, however, but rather of concerted actions on the part of those bodies (persons, agencies, corporations, states) invested in their proliferation’ (Suchman Citation2020, 4).

Migration and media infrastructure scholarship diverge in the way they draw attention to how infrastructures distinctively function as mediators. To put it starkly, migration infrastructure scholarship is mostly concerned with the infrastructural roles played by ‘intermediaries and brokers of different kinds’ (Lin et al. Citation2017, 172). These brokers involve state and non-state actors, migrants and non-migrants, professionally organized and amateur ‘middlemen’, mobile telephony providers, shipping companies, etc. In contrast to the more people-centered understandings of migration infrastructures, media infrastructure studies tend to over-emphasize physical materialities, which may date back from the original engineering understanding of the term infrastructure, as ‘the stuff you can kick’ (Parks Citation2015, 356), potentially overlooking entangled practices of people.

We propose here the concept of the imaginary, which allows for addressing human brokerage and the materiality of media and migration infrastructures together, in particular, with regard to their political and social intent. The imaginary can serve the purpose to grasp affective, discursive and psychological motivations behind certain forms of media technologies in migration infrastructures. Our understanding of the notion draws from Cornelius Castoriadis’ conceptualization of the imaginary as a culture’s ethos, Lacan’s understanding of the imaginary as a fantasy crafted in response to psychological needs and desires, and Benedict Anderson and Charles Taylor’s approach to the imaginary as shared cognitive schema (for a useful overview of multiple understandings of the imaginary, see Strauss Citation2006).

Infrastructural developments in media and migration infrastructures are the result of a specific ‘enthusiasm of the imagination’ (Mrázek Citation2002, 166), and reflect and reinforce power hierarchies. One’s positionality in migration infrastructures matters: ‘Imagination is situated; our imaginary horizons are affected by the positioning of our gaze. But, at the same time, it is our imagination that gives our experiences their particular meanings, their categories of reference. Whether it is “borders”, “home”, “oppression” or “liberation”, the particular meanings we hold of these concepts are embedded in our situated imaginations’ (Stoetzler and Yuval-Davis Citation2002, 327). Imaginaries of migration infrastructures and governance are coded into forms of mediation, including tools, discourses, images, and protocols. And, in turn, media infrastructures enable certain imaginaries and practices of governing and managing displacement. These reflect certain ‘structures of feeling’ (Williams Citation1977), in this case imaginative investments in desired solutions of control and curtailment of mobility into and within nation states, often at the expense, and hiding from view those deemed undesirable. Imaginaries are power-ridden because they 1) reflect limited cultural horizons, 2) commonly propose instrumental, utilitarian functionalities, and 3) are dominantly positively connoted (Sneath, Holbraad, and Axel Citation2009, 5–6). The point is therefore to explore the assumptions, or imaginary premises, of migration and media infrastructures: how are migrants, camps, media and their infrastructural interrelations imagined? Which cultural horizons are reflected in technologies of imaginations, e.g. how are nationalisms, modernity and progressivist thinking reflected? Which functions are imagined and for whom and by whom, e.g. how are utilitarian ideas about humanitarianism, migration management and control embedded, and how and why are they connoted? This negotiation is open-ended, subject to ongoing exchanges and contestations by a variety of stakeholders, including states, the humanitarian sector, tech-corporations as well as activists, solidarity groups and refugees themselves.

3. Charting media histories of migration infrastructures

The fundamental question of how infrastructures appear, for whom they work and for whom they do not, guides Geoffrey Bowker’s and Susan Leigh Star’s (Citation1999) classical study of classification systems in Western modernity. Based on analyses of categories, standards, and their socio-material articulation in infrastructures, they carve out a methodology of ‘infrastructural inversion’ (34) to tackle the invisibilized workings and arrangements of media technologies and respective practices of classification. Through inverting infrastructures, turning them on their head, processes of invisibilization can be reversed, and empirical observations of relations become possible, ‘recognizing the depths of interdependence of technical networks and standards, on the one hand, and the real work of politics and knowledge production, on the other’ (34). The methodology of infrastructural inversion orients us in uncovering the historical politics of naturalized standards, classifications and practices among stakeholders in migration and media infrastructures: the ubiquitous processes and interrelated systems, where categories have appeared, stabilized, and been invisibilized – or are decaying, instabilized and become visible over time.

In Germany, the appearance of labels and categories for forced migrants throughout the 20th century, as pointed out in the introduction, exemplifies such naturalized classifications: labels like ‘refugee’, ‘expellee’, ‘Displaced Person’ or ‘evacuee’ have been worked out as administrative classifications, which ‘filiate’ (Bowker and Star Citation1999, 315) bodies and categories, with real-life socio-material consequences. They regulate access to care and shelter, but also exclusion from further recognition or citizenship. To understand further the historical saturation of migration infrastructures with media technologies, the field of media history leads us to initiate the analysis of ‘historical, techno-medial constellations’ (Werkmeister Citation2016, 237), and then to trace imaginaries and practices of their implementation. John Durham Peters (Citation2015) captures the power dimensions imbued in these employments and developments of media as ‘leverage’, or ‘using a point to concentrate force over people and nature’ (20). Extracting this political project always already inside of media technologies and practices, of ordering and managing people in time and space, or in ‘nature’ in Peters’ words, adequately situates media in the creation of migration regimes and infrastructures.

The specific media technologies change and replace each other over time. Lisa Gitelman (Citation2006) suggests seeing media as both the materiality of the technology (a phone) and their connected protocols (saying ‘Hello’ when answering a call, paying monthly bills). This arrangement of social practices and technological dispositions forms historical contexts, both of which are never fully stable or defined: technological components, as well as practices and protocols, change and are adapted, in the form of new historical layers. Yet, in a non-linear understanding of history, they are always circular perpetuations and remediations of their predecessors. In the spirit of infrastructural inversion, media historical research in the field of administration and governance has pondered the relevance of media materiality to modern imaginaries of ordering and sorting the world. For example, within the medium of paper alone a myriad of practices can be uncovered, such as documenting, sorting, storing, catalogizing, categorizing, ranking, rating, and administrating, bureaucratizing or communicating knowledge and information at large. A body of work has carved out respective historical imaginaries and practices, forms and genres: tracing the genre of the ‘document’ from printing presses to the electronic PDF document (Gitelman Citation2014), the card catalogue as a predecessor of computing (Krajewski Citation2011), the standardization of office paper and forms (Järpvall Citation2016), files and filing as an undertaking of order and law (Vismann Citation2000) and the filing cabinet to automate memory through gendered forms of labor (Robertson Citation2021).

In approaching precisely the historicity of media technologies and infrastructures, Shannon Mattern (Citation2015) argues that media infrastructures have a ‘deep time’, which can become the object of study: ‘[T]hrough “excavation” we can assess the lifespans of various media infrastructures and determine when “old” infrastructures “leak” into new media landscapes, when media of different epochs are layered palimpsestically, or when new infrastructures “remediate” their predecessors’ (Mattern Citation2015, 103). In this manner, historiographical analyses can uncover situated, local meanings of media and migration infrastructures in the context of unfolding genealogies of both media technologies, practices and imaginaries. In order to trace empirically and methodically these historical trajectories of media and migration infrastructures and their imaginaries, we have conducted an analysis of archival files. Documents from post-war Germany (roughly 1945 to 1955) have been collected from state archives (State Archive Hamburg, State Archive Nuremberg, Red Cross Archive, UN Archives, Federal Archive Koblenz). The archive as an institution at the power-knowledge nexus is itself a media infrastructure, based on classifications systems. The state archives reflect practices of state power and administration, by hosting documents of authorities and their knowledge over people. Understanding the origin of the archival materials in their situated, historical contexts hence reveals practices of migration governance, which took place in the realm of the state, and its authorities and agencies. Migration governance and administration are fundamentally acts of state power.

In the spirit of infrastructural inversion, the documents can then be interpreted as instances and reports of techno-medial migration governance, hence revealing imaginaries of media and migration infrastructures. This media-historical approach to migration governance, furthermore, enables an urgently needed politicization of media infrastructures in migration. Bowker and Star (Citation1999) point out historical layers of how categories appear, are imagined and implemented, or disappear (42). A valuable contribution of historiography then becomes to read categories and classification systems into historical contexts, when they did not contemporarily exist. In this sense, Ann Laura Stoler (Citation2009) suggests, in her study of Dutch colonial archives about Indonesia, grasping the archive as an instrument of colonial state power, which needs to be read along and against its grain. This incorporates understanding the archive and its documents as ‘lettered governance’ (14), where ‘filing systems and disciplined writing produce assemblages of control and specific methods of domination’ (37). The state archive and its records – the document – are historical, mediated instruments of power. Thus, archival files can be entangled with colonial projects, as Stoler (Citation2009, 46) showed- as a site of ‘the imaginary’, they ‘concealed, revealed and contradicted the investments of the state’-; or with fascist genocide, which Hans Adler (Citation1974) showed in his famous study of the Holocaust from a bureaucratic perspective, aptly called ‘The Administrated Human’. Ultimately, these studies emphasize the need to rephrase media historically as non-neutral, non-objective components of migration infrastructures and their history, and archives can be a point of departure to access these histories.

Based on source criticism and contextual interpretation, the collected archival documents serve as an empirical basis for observing and reconstructing imaginaries and practices of media and migration infrastructures in the case of post-war Germany. The file collection consists of administrative documents (letters, forms, minutes, authorities’ correspondences), as well as photographs and newspaper clippings. The relevant documents have been identified through the archive catalogues by key word clusters around ‘media’ and ‘refugee camps’,Footnote1 and were then selected according to file titles and descriptions. Around 50 folders (roughly 2,000 pages) of archival material have been taken into account for the analysis, including documents produced by authorities on local, regional and national levels, as well as from UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), which was responsible for Displaced Persons-camps. More context will be offered in the case study below. The files are media themselves: they had mediating functions in their contemporaneous context, and mediate images of the past into the present. Through contextual reading, the files have been analyzed as both residuals and parts of historical media and migration infrastructures (e.g. forms or IDs), and as documents reporting and revealing imaginaries and practices in regard to infrastructures (e.g. internal documents or correspondences).

4. Case study: controlling refugee subjects in time and space in post-war Germany

Central Europe of the 1940s and 1950s was a site of critical developments of what was to become the ‘modern refugee regime’, or the global set of norms, discourses, laws and practices of refugee governance (Gatrell Citation2013; Betts Citation2010). Imaginaries of infrastructural administration of forced migration laid foundational groundwork for decades to come. World War II had displaced millions in Central Europe, groups which then were to be taken care of in occupied Germany under various bureaucratic labels. ‘Displaced Person (DPs)’ were those liberated from concentration, prisoner and labor camps, who found themselves far from home and were therefore also called ‘homeless foreigners’ (‘heimatlose “Ausländer*innen”’) (around 11 million). ‘Refugees’ (‘Flüchtlinge’), ‘expellees’ (‘Vertriebene’) and ‘resettlers’ (‘Umsiedler*innen’) became the official terms for ethnic Germans who had to leave the ceded areas East of the new border (around 12–14 million), as well as ‘war returnees’ (‘Kriegsheimkehrer’), soldiers and released prisoners of war returning home, sometimes many years later, or ‘evacuees’ (‘Evakuierte’), homeless from bombed cities.

From 1945, the Allied military governments (British, American, French and Soviet), in collaboration with restructured local authorities, took care of governing and organizing these forced migration processes, alongside organizations, such as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the Red Cross. Distribution of housing was the main issue with large-scale destruction and damage of buildings in Germany in 1945, which made the refugee camp a central infrastructural tool for both providing shelter, but also effectively administrating social benefits, labor and onward migration. The 1940s, hence, become a critical juncture, where public administration systems of the Third Reich devolve into Allied occupation and the new German states, including continuities and ruptures in staff, administration structures and practices, as well as places, e.g. concentration camps becoming refugee camps.

After 1949, the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) incorporated a historically unique asylum law. §16 of the constitution (Grundgesetz) grants the right to asylum to anyone ‘politically persecuted’, with no further conditions (conditions were added later on, mainly in changes during the 1980s and 1990s). This law, enabling asylum-based immigration until today, was initially mainly geared towards refugees from the Communist Eastern bloc, used, for example, by Hungarians fleeing the anti-communist uprising in 1956. Simultaneously, millions of citizens from East Germany, first from the SBZ (Soviet Occupation Zone, 1945–1949) and later the German Democratic Republic (GDR), fled to the West throughout the Cold War years, forming another key group of forced migrants.

As the key infrastructural solution to post-war refugee governance, the refugee camp became a common space for all these diverse groups. Institutionalized shared accommodation spatialized and materialized an infrastructure of governing forced migrants in time and space. The camp was an emergency tool of order as well as relief, where other modalities of infrastructuring, such as registration and case filing could take place. In post-war Germany, the camp as a spatial instrument of population control did not come from a void. The Third Reich had installed a country-wide network of camps, which often became repurposed for accommodating refugees, DPs, evacuees or other homeless people in the post-war turmoil. Notwithstanding the fact that housing was generally scarce due to large-scale destruction and that the use of concentration or labor camps was an emergency solution, camp spaces carry historical continuities in their setup, spatial logic and operations.

As critical studies on the camp as a ‘modern space paradigm’ have shown (Schwarte Citation2007), the camp as a biopolitical modern endeavor includes a continuum of institutions, manifesting itself in leisure camps, education and, training camps, but also refugee camps, and in their utmost extreme, in the concentration and annihilation camp. Transforming former Nazi-German camps into refugee camps, in this sense, inscribed a new historical layer of purpose in the same material surroundings: spatial distinction and separation, barracks and common accommodation with the collapse of the private, mass catering, camp rules – all means of population control which were distinctively sustained through diverse infrastructures. As emergency, crisis-solutions, camps were imagined with the promise of temporariness; in reality they often became protracted or permanent. German refugees and expellees often continued to live in camps until the 1960s. Until today, the refugee camp globally constitutes a central humanitarian migration infrastructure. Within this historical context of camp-based forced migration governance, the following section traces the role of media infrastructures in creating, upholding and forming administrational practices of the emerging refugee regime during the post-war years.

4.1. Bureaucratic imaginaries of paper-based migration governance

The fundamental goal of administrations, who took care of forced migrants after 1945, reflects distinct desires of control and order, (some kind of) justice and fairness, and a durable solution. Millions were on the move, and resources were scarce, fueling even more movements. This put authorities into a position where they imagined their task to revolve around the navigation and steering of refugee movements, accommodations and care.

In 1945, the city of Hamburg saw thousands of arrivals every day, refugees coming from the East, as well as war returnees. Sources from the city’s authorities provide insight into the formation of refugee-oriented migration infrastructures. An adequate management system was imagined allowing authorities to solve the so-called ‘refugee question’. This phrasing, speaking of a ‘Flüchtlingsfrage’, runs through administrational files, as well as societal discourses of that time. Not only is this metaphor inherently solutionist, as it naturally implies a resolution with respective, well-developed answers; also is this phrasing reminiscent of other historical ‘questions’ across German history, such as the so-called ‘German Question’ in the 19th century about the achievement of national unification, or the so-called ‘Jewish Question’, debating the treatment of Jews in Europe during the 1800s and 1900s, ultimately leading to the so-called ‘Final Solution’, the genocide of Jews during World War II.

In November 1945, the British military government had installed 2,600 ‘Nissen-hut’ camps in the city, allowing the local authorities to ‘steer the housing shortage’Footnote2.Footnote3 The city government, reporting to the British military, as well as a ‘refugee committee’, consisting of charity organizations and different authority representatives, designed the procedures. A government memo,Footnote4 dated 20 November 1945, commanded the different city districts how to prioritize, register, report and control the allocation of benefits and the mobility of the arriving forced migrants. The correct ratio of single men and women and families was to be kept in the camps in the allocation of an exact number of square meters per person, and food stamps were to be distributed. Specific groups such as generally homeless people or people living ‘unworthily in basements’ were ordered to be listed on reserve lists.

This camp ‘admission’ processing took place in a centralized housing bureau in the BieberhausFootnote5 in central Hamburg – which leads us directly to the heart of the workings of media infrastructures as part of the emerging refugee apparatus: the imaginaries and logics of paperwork. This entire operation relied on a system of lists, reservation cards (‘Vormerkungskarte’), file indexes, running slips, camp and refugee passports, health status documents and other permits and certificates allocating specific groups of bodies a specific regiment of mobility and employment.

The medium of paper, as a mobile portable device of identification, storing and authenticating information, realized imaginaries of sorting, controlling and administrating people in time and space. Efficient paper-based forms of office administration and communication, which had evolved in the early 20th century in office reforms and technological innovation such as standing folders, as described by Cornelia Vismann (Citation2000) or Charlie Järpvall (Citation2016), bureaucratically enabled objectives of getting control over and influencing forced migration processes. These infrastructures reveal how imaginaries of social engineering were coded into media forms allowing a specific sorting and classifying of subjects, and arranging them accordingly. In the moment of inscription, these documents filiated bodies with categories, mobilities, and access to benefits, translating biological and biographical data into administrationable units. By way of media practices of filiation, templates for the management of refugees emerged, which ultimately reduce and dehumanize refugee bodies into identified and identifiable units.

Identification as a practice of determining between same and different (cf. ‘identical’ vs. ‘identity’), reaches at least into the late Middle Ages (Groebner Citation2007), emerging as a practice of making populations manageable, and is always already enabled by media (such as images). While in the post-war context, humanitarian imaginaries of providing shelter and care after the horrors of the war surely guided the deployment of media and migration infrastructures, their media practices of template-like filiation, identification, and categorization of bodies hold inherent potentially dehumanizing and reductionist consequences, which still undergird and become ever more apparent in media and migration infrastructures today.

4.2. Permits, IDs and other documents

This emergent system became a prototype of the global refugee regime and its infrastructures to come. Tracing its historical functioning demonstrates how media have always been (made) complicit in controlling refugee subjects in time and space. As a forced migrant in Germany of the late 1940s, one had to fit into the classification system through navigating its media infrastructures: being assigned a label and specific refugee status, passes and IDs allowing for movement, access to accommodation, benefits and food. The planning of these infrastructures provides insight on the brutal imaginaries reflecting the steep power imbalances between administrators and those subjects to-be-administrated. In August 1945, Hamburg introduced tight measures to lower refugee arrivals through

[t]ighter control over the issue of food cards. Issue of food cards in Hamburg is dependent on previous grant of permission to stay in the city. This is already managed on such strict lines that in Hamburg food cards are issued only to individuals entitled to stay.

Of course, the permit to stay legally in Hamburg was tied to a respective document as well. Those travelling through the city and wanting food cards were required to provide a certificate from a mayor of a town ‘showing permission of the burgomaster of the community into which the refugee desires to move’.Footnote7

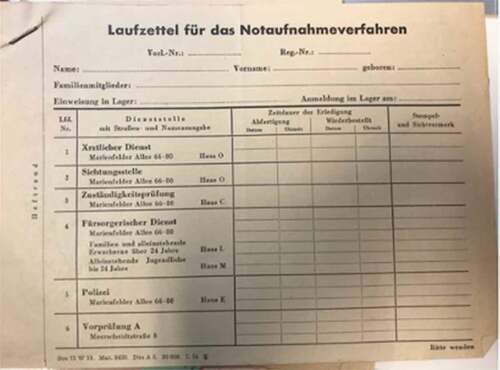

depicts the respective slip, which gave the right of passage. The Allied governments were eager to prevent further movements throughout the late 1940s, especially as migration from the ‘Soviet Zone’ into the ‘Western’ zones increased. Border closures between the zones, crossing tied to permits, and transit camps appeared as tools to slow down, control and verify movements. To navigate the complexity of these systems, eventually an ‘information sheet for East-refugees’ was issued explaining the bureaucratic procedures, as well as ‘press and radio propaganda’ undertaken to influence potential movement and discourage from migrating to specific places.

Figure 1. ‘Certificate’, to be signed by a mayor, stating that the named forced migrant receives accommodation in this municipality. (Staatsarchiv Hamburg, 131–1 II Senatskanzlei – Gesamtregistratur II, Nr. 1233, ”Betreuung von Heimatvertriebenen, Fl– chtlingen und Evakuierten, 1945-1956”)

Indicative of how the hierarchical ‘politics of mobility’ reproduces unequal social relations (Creswell Citation2010, 21), the provision of information was channeled to specifically desired, entitled mobile subjects. Effectively, through curating a specific ‘condition of information stability’ through propaganda and selective information provision, this media infrastructure served to further exclude undesirable subjects (Wall, Campbell, and Janbek Citation2020, 504). We note many parallels between this example of the strategic deployment of media infrastructural ‘information precarity’ (ibid.), with contemporary migrant-oriented information provision schemes, which target desirable migrants, and actively seek to under-inform and deter undesired mobile subjects.

Tracing the ‘choreography’ of human movement (Sheller Citation2018, 199) further in the archival material makes visible different kinds of paper-based infrastructures, mediating emerging imaginaries of refugee governance and humanitarian action. Once arrived in a camp, mobility was controlled in various specific ways. The camp per se already infrastructuralized imaginaries of migration control through its physical arrangement, namely segregation and controllability. In Nuremberg, the so-called ‘Valka-camp’ was established in 1946 to accommodate and administer ‘heimatlose Ausländer’, DPs, and later on foreign asylum-seekers. It became the key registration place for foreign asylum immigration in West Germany of the 1940s and 1950s, until numbers of asylum-seekers rose to such levels that admission had to be distributed across the entire country. Until today, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) is located next to this historical site, in Nuremberg-Zirndorf.

As a newspaper reports in 1953, ‘a part of the Valka-camp is therefore set up as a quarantine station. The inmates of this camp section are separated from the other inmates by a high fence, in order to guarantee a strict political examination.’Footnote8 Mainly sheltering refugees from the Eastern bloc, the process of ‘political examination’ alluded to in the newspaper account most likely referred to a political ‘quarantine’ reflecting a stance of Cold War anti-communism. As this and other contemporary newspaper coverage of camps show, the residents of the camp – or as they were called back then ‘inmates’ – were othered not only spatially, but also symbolically. Often prejudices and attitudes towards camp residents lingered on from pre-1945 discourses, among the wider population, but also journalists or policymakers: perceiving camp populations as ‘homo barrackensis’ (camp people) or pathological ‘social outcasts’, ‘dirty’, and ‘antisocial’.

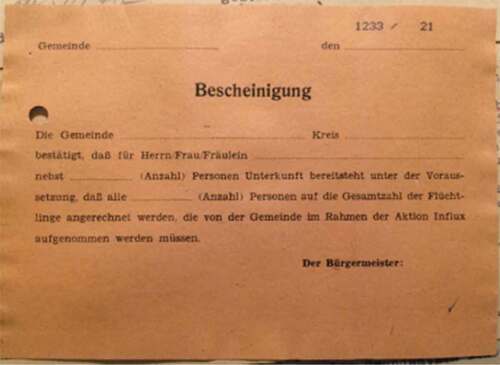

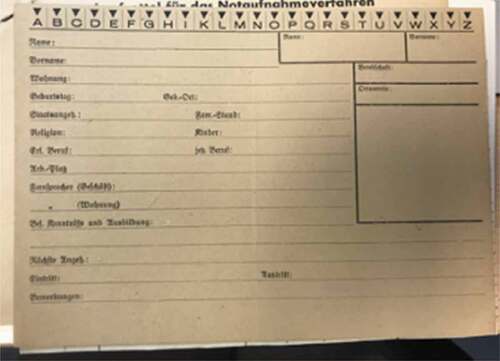

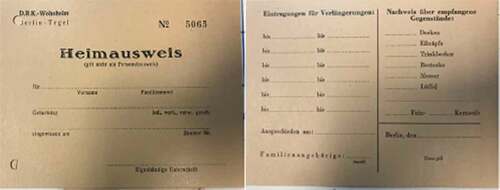

Extreme concentration coupled with spatial separation from the rest of the city is a first layer of migration infrastructure. This layer perpetuates itself in forms of media technologies, such as specific permits, camp IDs and documentation sheets structuring camp life, and monitoring its residents’ activities. show different types of IDs and passports issued to refugees. Such documents could both enable and disable mobility: not only would they function as proof of the identified individual’s entitlement to social benefits and residency in the camp, they would also define the limits of one’s movement range and enable moments of control.

Figure 2. Registration card, filable (alphabet on top), documenting entry and exit (second to last row) (Red Cross Archive, Berlin: DRK 4750)

Figure 3. ‘camp identification card’. Front (left), back (right). Registering name, birthday, marital status, admission date, room number, signature. Backside: documenting prolongations and receipt of goods: blankets, eating bowls, drinking cups, cutlery, knife, spoon (Red Cross Archive, Berlin: DRK 4750)

Infrastructures that ‘contain and isolate’ (Mountz Citation2020, p. 20) are much like the offshore United States and Australian immigration detention facilities (see Julia Morris in this Mobilities special issue), or low-wage migrants in Dubai or Singapore who are housed in dormitories at the edges of the city (Kathiravelu Citation2016). They can be understood in a longer historical genealogy of normalizing and legitimating the separation (excluding from public view) and encampment of specific groups of mobile people on the basis of a ‘concentrationary imaginary’ (Pollock Citation2015, p. 5), making refugee camps into heterotopias of simultaneous and paradoxical inclusion (into care and shelter) and exclusion (from recognition and citizenship) (Seuferling Citation2019).

Issued documents reflect how these media infrastructures are imbued with power hierarchies shaped by intersecting axes of nationality, gender, sexuality and age. An internal UNRRA document from DP-camps Greven and Reckenfeld reports about Polish troops visiting the camps ‘for the purpose of taking Polish girls out to “dances”. On some occasions, these so-called “dances” have lasted two and three days.’Footnote9 The angry ‘Major R.A.’ then emphasizes ‘that all applications to take girls to dances from the camps should be made to the UNRRA Welfare Officers at the camp who will issue late passes up to midnight’ and ‘that all DPs must observe curfew’.Footnote10

Here we see how refugee camps became institutionally gendered, through forms of infrastructuring. ‘Major R.A’ sought to accommodate patriarchal norms of Polish men having control and ‘ownership’ over Polish female refugees through administrative measures. In creating specific administrative conditions, refugee camps may thus have enabled and thereby legitimated sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), which ‘comprises violence inflicted on a person due to their gender and/or her perceived status as a sexual object’ (Olsen and Scharffscher Citation2004, 377).

Evidence of injuries and violations of personal autonomy as a result of obligatory ‘mixing’ – as is the case with the example above of soldiers taking women from camps – is corroborated in testimonies from Polish women in exile during and in the aftermath of World War II (e.g. Jolluck Citation2002, 156). The early trace of how refugee camps become gendered infrastructurally, as documented above, is thus long overdue, particularly when considering that ‘conflict-based gender-based violence has only gained attention over the past 25 years’ (ibid.).

Apart from ‘late passes’ and camp IDs for entering and exiting, such documents further infrastructuralized and bureaucratized the process of being and being made a refugee in the administrational sense: social and political norms of difference are inscribed and surveilled by logging biological and biographical features in documents (Browne Citation2015). For instance, refugee transit camps for GDR-refugees in West Berlin, run by the German Red Cross, had a systematic media infrastructure in place, which documented the refugees’ ‘reasons of escape’ (used for verifying individual asylum claims), their movement around the different stages of registration, e.g. health checks, delousing, X-rays, police checks etc., as well as the reception of donations, such as clothes. Illustratively, shows a ‘running slip for the emergency reception procedure’, literally controlling the refugee’s movements from stage to stage: ‘medical service’, ‘review office’, ‘responsibility check’, ‘charity service’, ‘police’, ‘pre-check A’. Similarly, the camp ID card in documented ‘evidence of received objects’ in the back. Thereby, received welfare could be communicated between the different camps, which a refugee would go through, and a doubling of donations could be avoided. Ultimately, a small note in internal Red Cross files on the monitoring of personal hygiene reveals the pervasiveness of documentation: ‘Experience: Women are reluctant to shower (one camp introduced stamps on food cards for that).’Footnote11 The depths of power hierarchies and dehumanization become ingrained into disciplinary media and migration infrastructures. Obviously, camp structures requiring women inhabitants to shower in shared, mixed-gender bathrooms expose these women to potential gender harassment and violence. The widespread occurrence of SGBV in refugee camps such as rape has been explained commonly to result from institutionalized ‘latent conditions’ of man-made ‘organisational failures’ (Olsen and Scharffscher Citation2004, 377). This instance shows how the infrastructural assemblage of the built environment, logistical procedures and administration setup to monitor personal bodily hygiene fail women: at best it appears oblivious to (and at worst seemed wilfully to create) SGBV risks. Regulating showering through food stamps as a viable solution demonstrates the brutalism that infrastructural regimes can assume. Infrastructural control reduces people into administrative units. The process of producing knowledge on Others differentially impacted refugees. The reinforcement of the vulnerability of specifically gendered subjects is a practice painfully reminiscent of rape culture in camps under the Nazi Regime (Rayson Citation2018) and is haunted by the logic of sexualization which permeated the colonial project (Coetzee and Du Toit Citation2018).

4.3. Case files, registries, and their labor

Lisa Gitelman (Citation2014) has conceptualized the ‘document’ as a media genre, a socio-material object of ‘knowing and showing’, recognizable to its users as carrying evidence of an external reality. Understanding the presented archival sources as such foregrounds their entanglement with distinctive value-laden imaginaries of the emerging refugee regime. As media and migration infrastructures, these media artefacts were once envisioned as efficient solutions for managing the ‘refugee question’ of the time, able to create, store and communicate knowledge about people. Translating and coding human stories and fates, their biographies into cases, registries, and file indexes is an act of mediating imaginaries of bureaucratic solutionism, statistics and humanitarianism. The idea of registering and processing refugee cases based on their respective stories is still the fundamental organizing system informing asylum procedures today. No case decision is made without bureaucratically mediated proof and documentation of one’s story and experiences. As the initial examples already hint at, this practice has historical traces in post-war refugee administration too. Authorities started building registries of case files, first and foremost for better and allegedly fair processing of benefits and shifting people around camps. Becoming a refugee, hence, means being infrastructuralized and becoming a case file, a traceable document.

However, such registries also grew out of the need of forced migrants themselves, to find lost relatives and friends again. For that reason, UNRRA and later the Red Cross eventually built a European media infrastructure called the ‘International Tracing Service’, whose aim was to reconnect people lost in the post-war turmoil. Based on file indexes, and a European network of mail and telegraphy, headquartered in the small town of Bad Arolsen, this media infrastructure collected biographies in order to match searching and sought-after individuals. Similarly, the social ministry in the state of North-Rhine-Westphalia created a so-called ‘registry of misery’, collecting stories and cases of refugees. Specifically, these last two examples foreground the involvement of refugees themselves in the labor of media and migration infrastructures. Infrastructures are always built on the labor involved in materializing social relations. First, forced migrants contributed the very content of any mediated migration infrastructure. All documents would be meaningless without the subjects and bodies they relate to. But not only did refugees build the registers by telling their stories, also did they partake in the physical labor of administrational work.

The International Tracing Service relied on the work of camp residents in recording, filing and other chores of the operation. In general, it was not unusual that camp administration included refugee residents for camp work, also for purely economic reasons: ‘Every effort will be directed towards reducing the cost to British funds of maintaining Displaced Persons, and to this end the maximum use is to be made of Displaced Persons for their own administrative work. […] Signed by Sgd M.C. Brownjohn, Major-General, Acting Deputy Military Governor’.Footnote12 UNRRA even offered specific training programs, where selected DPs could be sent to be educated on administrational tasks, as part of vocational training to qualify them for later life, but also so they could take over administrative work in the UNRRA operations.

5. Conclusions

Considering early forms of mediation in migration infrastructures of the immediate “post-World-War-II” years demonstrates the historicity of imaginaries and practices materialized in infrastructures of refugee governance. The social relations formed between forced migrants and authorities, based on the refugee regime, became mediated, materialized and, hence, infrastructuralized in media, such as paper, registries, files, and procedures. Vice versa, media infrastructures create social relations between forced migrants and state authorities. Dissecting these processes reveals how controlling, managing and policing people in time and space, i.e. mobility and specific activities, as well as benefits distribution, becomes a project of state governance, imbued in technological solutions, drawing on specific media technologies. Exposing ‘uneven infrastructures’ is important to scrutinize the unjust mobilities they ‘enforce, normalize, and legitimate’ (Sheller Citation2018, 485). In particular, we highlighted how historical media infrastructural set-ups and routines designed for an efficient camp operation were built on inscribing biological and biographical information about refugee bodies and subjects into documents, which in consequence subjectivizes and disciplines individuals, and can lead to harm, by e.g. exposing women to risks of sexual and gender-based violence. Camp infrastructures and their mediated bureaucratic systems render the lives contained into public matters by default, purposefully curtailing and surveilling the private, autonomous realm of camp dwellers.

The historical perspective unravels a genealogy of media technologies, and their deployment in migration governance, namely pointing out how imaginaries of efficient categorizing, ranking, and sorting are realized across media technologies. When we fast-forward in time, tracing media and migration infrastructures of asylum administration leads to another critical moment of media history: digitization and parallel outsourcing of migration management during the 1990s. While countries of origin of forced migrants arriving to Germany have globalized, the key features of the refugee regime in place remain constant: obligatory camp accommodation for asylum-seekers, dependent on benefits and case processing, saturated by media technological infrastructures. During the mid-1990s, a computer-readable chip card system was introduced in German asylum-seeker shelters in order to digitize existing migration infrastructures of controlling mobility and benefit-related activities, such as shopping. The ‘Infra-Card’ – literally an infrastructuralization – by the French company Sodexho (later Sodexo) was implemented in refugee administration. Sodexo is a global corporation in catering and facility management, including asylum-seeker shelters and also prisons. In the neoliberal manner of the 1990s, the German state outsourced more and more services of relief and welfare through public-private-partnerships. The Infra-Card was topped up monthly by social services with the exact sum of money to be received. Then, the asylum-seeker could use the card to pay – but only in specific shops and for specific goods, enabling full surveillance.

This early digital device of controlling asylum-seekers’ activities materializes the principle of ‘benefits in kind’, which since the 1980s has been growing in German asylum-seeker welfare and was made obligatory in 1997. Benefits to asylum-seekers were to be paid only in goods, not cash. Chipcards hence enabled the authorities to further monitor and police mobility and activities of forced migrants. As critical reports from activist groups as well as news coverage reveal,Footnote13 the chipcard materialized a continuation of imaginaries around media technologies and their role in migration governance: a new technological layer replacing and perpetuating the control of individuals in time and space and administration of this monitoring: imaginaries, we could already trace back into the post-war years.

Thus, the recent high-tech mediated migration infrastructural experiments illustrate the fundamental role of the imaginary in managing so-called ‘refugee crises’ situations. Consider, for instance, requiring refugees in Za’atari refugee camp, Jordan, to access personal benefits through having their irises scanned, or expected cheap refugee labor in mapping camps using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) or refugees in Uganda entering the gig economy by training algorithms (Litman-Navarro Citation2018; Tomaszewski Citation2018; Macias Citation2020). The post-war German ‘refugee question’ has evolved to a global ‘refugee crisis’.

The massive pain and suffering of large-scale displacement are not felt, perceived and processed outside of ideological frames and fantasies. In this article, we showed how the widespread black-boxed technological solutionism reflected in the infrastructural imaginaries of efficient ordering, administrating and limiting of specific mobile people in space and time does not come from a void. To avoid technological exceptionalism, more attention is needed to historical lineages and precedents.

At extreme scales, during the colonial and Nazi Third Reich era, othered, and dominated populations became the testing ground for new technologies and infrastructures. In the 19th and early years of the 20th century, places like South Africa, India and Japan became ‘techno-colonial’ (Madianou Citation2019) laboratory sites to experiment with, for example, biometrical racial classification through fingerprinting (Nishiyama Citation2020). Punch-card tabulation technologies are identified as part of the infrastructure that ‘rationalized the management of concentration camp labor’ in Nazi Germany (Luebke and Milton Citation1994, 25).

Uncovering these genealogies points at the central role of media technologies, and their ‘leverage’ (Peters Citation2015, 20), as components of migration infrastructures, which need to be politicized. As the focus on post-war migration infrastructures show, the colonial and fascist lingerings of infrastructuring and documenting the body and its biology coincide with and evolve into a focus on the biographical as the criterion for categorization. Always at the center is the ‘graphical’, the moment of inscription and mediation. Historicizing research here makes visible the negotiation processes that are reflected in circulating imaginaries, uncovering how they are not static or pregiven, but always contingent and evolving.

Further research can address exactly the circulation and commodification of technological innovation from experimental sites, contestations from below, which we have largely left unaddressed here and the specific implications of extracting refugee labor through infrastructures. Without a critical reconsidering of the implications of black-boxed tech-driven innovations, contemporary imaginaries of migration infrastructures, that in the humanitarianism-securitization continuum increasingly shifts towards the latter, risk continued violation of specifically targeted mobile subjects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Key word clusters denotating the different terms for ‘camp’ have been applied to the respective search catalogues and crossed with key words around ‘media’. Search words (English translations): ‘Camp’: refugee camp, refugee accommodation, asylum-seeker home, central contact point, common accommodation, camp of first reception, emergency reception camp, transit camp, asylum-seeker accommodation, asylum-seeker home. ‘Media’: media, communication, radio, newspaper, magazine, television, phone, telecommunication, cinema, film, mail, letter.

2. All German quotations from the material have been translated by the authors.

3. Staatsarchiv Hamburg (StAHH), StAHH, 131–5_151/24: ‘Wohraumangelegenheiten; Flüchtlingslager, Nissenhütten; Bewirtschaftung von Lagern, Baracken und Wohnheimen’, 1945–1950.

4. Ibid.: ‘Rundschreiben Nr. 11, 20.11.1945’.

5. The Bieberhaus is a historical building in central Hamburg, which has always housed an array of activities under the same roof, such as theaters, cafés, dance locales, but also refugee registration and help, a clothing donation center, or a reception center for street children. During the refugee arrivals of 2015 it once again became a refugee transit center.

6. [sic!], English original (probably translated by German civil servant for the British Military Government), StAHH, 131–1 II_1233: ”Betreuung von Heimatvertriebenen, Flüchtlingen und Evakuierten, 1945–1956”.

7. Ibid.

8. Federal Archive Koblenz (BArch), B115/5753, 8-Uhr Blatt Nürnberg Nr 16, 21.1.1953: ”Valkalager wird zum Bundes-Auffanglager”.

9. UN Archives, S-0409-0038-05, ‘BZ/ZO:WEL/Welfare and Education-387-Welfare-Education-Entertainment, Religion, Amenities, Post, Newspapers, 1945–1946’.

10. Ibid.

11. Red Cross Archive, Berlin: DRK 530.

12. UN Archives, S-0399-0003-03, ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’.

13. See e.g. the ‘Initiative gegen das Chipkartensystem’ (http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~wolfseif/verwaltet-entrechtet-abgestempelt/texte/chipini_chipkarten.pdf), or an Indymedia report on Sodexho (https://de.indymedia.org/2002/01/14593.shtml). An Infra-Card is also exhibited in the Stuttgart’s City Museum: https://bawue.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&suinin=4&suinsa=6&oges=278

References

- Adler, H. G. 1974. Der verwaltete Mensch. Studien zur Deportation der Juden aus Deutschland. Tübingen: Mohr.

- Betts, A. 2010. “The Refugee Regime Complex.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 29 (1): 12–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdq009.

- Bowker, G. C., and S. L. Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Browne, S. 2015. Dark Matters. On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Coetzee, A., and L. Du Toit. 2018. “Facing the Sexual Demon of Colonial Power: Decolonising Sexual Violence in South Africa.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 25 (2): 214–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506817732589.

- Collins, F. L. 2020. “Geographies of Migration I: Platform Migration.” Progress in Human Geography. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520973445.

- Creswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407.

- Daher, E., S. Kubicki, and A. Guerriero. 2017. “Data-driven Development in the Smart City: Generative Design for Refugee Camps in Luxembourg.” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 4 (3): 364–379. doi:https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2017.4.3S(11).

- Dalakoglou, D. 2016. “Infrastructural Gap. Commons, State and Anthropology.” City 20 (6): 822–831. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1241524.

- Dijstelbloem, H. 2020. “Borders and the Contagious Nature of Mediation.” In Handbook of Media and Migration, edited by K. Smets, K. Leurs, M. Georgiou, S. Witteborn, and R. Gajjala, 311–320. London: Sage.

- Gatrell, P. 2013. The Making of the Modern Refugee. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gitelman, L. 2006. Always Already New. Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gitelman, L. 2014. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Glouftsios, G. 2020. “Governing Border Security Infrastructures: Maintaining Large-scale Information Systems.” Security Dialogue. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620957230.

- Groebner, V. 2007. Who are You? Identification, Deception, and Surveillance in Early Modern Europe. Brooklyn, NY: Zone.

- Holt, J., and P. Vonderau. 2015. “Where the Internet Lives: Data Centers as Digital Media Infrastructure.” In Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, edited by L. Parks and N. Starosielski, 71–93. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press.

- Innovation Accelerator, W. F. P. 2020. “Building Blocks. Blockchain for Zero Hunger.” World Food Programme. Accessed 26 Jul 2021. retrieved from: https://innovation.wfp.org/project/building-blocks

- Järpvall, C. 2016. Pappersarbete. Formandet Av Och Föreställningar Om Kontorspapper Som Medium. Lund: Lund University.

- Jolluck, K. R. 2002. Exile & Identity. Polish Women in the Soviet Union during World War II. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Kathiravelu, L. 2016. Migrant Dubai. Low Wage Workers and the Construction of a Global City. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Krajewski, M. 2011. Paper Machines. About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Larkin, B. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

- Latonero, M., and P. Kift. 2018. “On Digital Passages and Borders: Refugees and the New Infrastructure for Movement and Control.” Social Media + Society 4 (1): January – March. 1–11.

- Lin, W., J. Lindquist, B. Xiangm, andB .S. A. Yeoh. 2017. “Migration Infrastructures and the Production of Migrant Mobilities.” Mobilities 12 (2): 167–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1292770.

- Lindquist, J., B. Xiang, andB. S. A. Yeoh. 2012. “Opening the Black Box of Migration: Brokers, the Organization of Transnational Mobility and the Changing Political Economy in Asia.” Pacific Affairs 85 (1): 7–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.5509/20128517.

- Litman-Navarro, K. 2018. “Using Refugees to Train Algorithms Is Some Dystopian Shit.” The Outline, Accessed 26 Jul 2021. retrevied from https://theoutline.com/post/6619/paying-refugees-to-train-algorithms-is-a-bad-idea?zd=2&zi=ypg2u4v2

- Luebke, D. M., and S. Milton. 1994. “Locating the Victim: An Overview of Census-taking, Tabulation Technology and Persecution in Nazi Germany.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 16 (3): 25–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.1994.298418.

- Macias, L. 2020. “Digital Humanitarianism in a Refugee Camp.” In Handbook of Media and Migration, edited by K. Smets, K. Leurs, M. Georgiou, S. Witteborn, and R. Gajjala, 334–345. London: Sage.

- Madianou, M. 2019. “Technocolonialism: Digital Innovation and Data Practices in the Humanitarian Response to Refugee Crises.” Social Media + Society 5 (3): 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119863146.

- Mattern, S. 2016. “Scaffolding, Hard and Soft – Infrastructures as Critical and Generative Structures”. Spheres. Journal for Digital Cultures. No 3. Accessed 26 Jul 2021. https://spheres-journal.org/contribution/scaffolding-hard-and-soft-infrastructures-as-critical-and-generative-structures/

- Mattern, S. 2015. “Deep Time of Mediatization.” In Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, edited by L. Parks and N. Starosielski, 94–112. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Metcalfe, P., and L. Dencik. 2019. “The Politics of Big Borders: Data (In)justice and the Governance of Refugees.” First Monday 24 (4): 1–15.

- Molnar, P. 2020. “Technological Testing Grounds.” European Digital Rights/Refugee Law Lab, Accessed 26 Jul 2021. retrieved from: https://edri.org/our-work/technological-testing-grounds-border-tech-is-experimenting-with-peoples-lives/

- Mountz, A. 2020. The Death of Asylum. Hidden Geographies of the Enforcement Archipelago. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mrázek, R. 2002. Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Nathan, T. 2017. “How to Turn Refugee Camps into Smart Cities.” World Economic Forum, Accessed 26 Jul 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/08/can-we-turn-refugee-camps-into-smart-cities-e5281afc-7213-40f6-bf13-d304e20c8943/

- Nishiyama, H. 2020. “Bodies and Borders in Post-Imperial Japan: A Study of the Coloniality of Biometric Power.” Cultural Studies. 1–21. Online first. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1788619.

- Olsen, O. E., and K. Scharffscher. 2004. “Rape in Refugee Camps as Organisational Failures.” The International Journal of Human Rights 8 (4): 377–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1364298042000283558.

- Pallister‐Wilkins, P. 2017. “Humanitarian Rescue/sovereign Capture and the Policing of Possible Responses to Violent Borders.” Global Policy 8 (1): 19–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12401.

- Parks, L. 2009. “Around the Antenna Tree: The Politics of Infrastructural Visibility.” Flow 6 (3). Accessed 26 Jul 2021. http://flowtv.org/2009/03/around-the-antenna-tree-the-politics-of-infrastructural-visibilitylisa-parks-uc-santa-barbara

- Parks, L. 2015. “Stuff You Can Kick: Toward a Theory of Media Infrastructures.” P. Svensson and D. T. Goldberg edited by. Between Humanities and the Digital. 2015 Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 355–373.

- Parks, L., and N. Starosielski. 2015. “Introduction.” In Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, edited by L. Parks and N. Starosielski, 71–93. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press.

- Peters, J. D. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Pollock, G. 2015. “A Concentrationary Imaginary.” In Concentrationary Imaginaries: Tracing Totalitarian Violence in Popular Culture, edited by G. Pollock and M. Silverman, 1–46. London: IB Tauris.

- Rayson, D. 2018. “Women’s Bodies and War.” In Rape Culture, Gender Violence and Religion, edited by C. Blythe, E. Colgan, and K. Edwards, 119–142. Cham: Palgrave.

- Robertson, C. 2021. The Filing Cabinet. A Vertical History of Information. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Pres.

- Schwarte, L., ed. 2007. Auszug aus dem Lager. Zur Überwindung des modernen Raumparadigmas in der politischen Philosophie. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Scott-Smith, T. 2016. “Humanitarian Neophilia: The ‘Innovation Turn’ and Its Implications.” Third World Quarterly 37 (12): 2229–2251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1176856.

- Seuferling, P. 2019. ““We Demand Better Ways to Communicate”: Pre-Digital Media Practices in Refugee Camps.” Media and Communication 7 (2): 207–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1869.

- Sheller, M. 2018. Mobility Justice. The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. London: Verso.

- Sneath, D., M. Holbraad, and P. M. Axel. 2009. “Technologies of the Imagination.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 74 (1): 5–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840902751147.

- Star, S. L. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (3): 377–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326.

- Stoetzler, M., and N. Yuval-Davis. 2002. “Standpoint Theory, Situated Knowledge and the Situated Imagination.” Feminist Theory 3 (3): 315–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/146470002762492024.

- Stoler, A. L. 2009. Along the Archival Grain. Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Strauss, C. 2006. “The Imaginary.” Anthropological Theory 6 (3): 322–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499606066891.

- Suchman, L. 2020. “Introduction.” In Sensing In/Security. Sensors as Transnational Security Infrastructures, edited by N. Klimburg-Witjes, N. Poechhacker, and G. C. Bowker, 3–5. Manchester: Mattering Press.

- Tomaszewski, B. 2018. “Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Displacement.” In Digital Lifeline? ICTs for Refugees and Displaced Persons, edited by C. Maitland, 165–184. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Truscello, M. 2020. Infrastructural Brutalism. Art and the Necropolitics of Infrastructure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Vismann, C. 2000. Akten. Medientechnik und Recht. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

- Wall, M., M. O. Campbell, and D. Janbek. 2020. “Refugees, Information Precarity, and Social Inclusion.” In The Handbook of Diasporas, Media, and Culture, edited by J. Retis and R. Tsagarousianou, 503–514. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Werkmeister, S. 2016. “Postcolonial Media History.” In Postcolonial Studies Meets Media Studies: A Critical Encounter, edited by K. Merten and L. Krämer, 235–256. Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag.

- Williams, R. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Winner, L. 1980. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus 109 (1): 121–136.

- Xiang, B., and J. Lindquist. 2014. “Migration Infrastructure.” The International Migration Review 48 (1): 122–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12141.