ABSTRACT

Indigenous people of Ecuador have suffered for a long time from marginalisation in access to quality education, which for them means culturally and ecologically pertinent education close to their own communities. During the past decade, education reform and closure of small rural schools worsened the spatial accessibility of schooling and increased the eco-cultural distance of education from the students’ lives. These two elements – spatial and eco-cultural representation – are constitutive of territorial rights claimed by Indigenous people. In this study, we aim to articulate the relationship between access to eco-culturally pertinent education, and mobility and territorial justice. Based on the review of studies on education reform, fieldwork in Amazonia in 2018–2019, and remote conversations in 2020, we identified and analysed three events – education reform, Indigenous protests and the Covid-19 pandemic, which have disrupted access to education within Indigenous territories. These turbulent events make visible territorial and mobility injustices, including the dismissal of Indigenous visions of education, the strategic weakening of Indigenous territorial defence, and the lack of state support for access to education in remote areas. The analysis advocates for the recognition of mobility and territoriality as part of the social justice agenda in quality education.

Introduction

Equal access to quality education is a means for social justice across generations and places, but in the mainstream approaches, this principle has been interpreted in unifying terms based on Western standards. For instance, the United Nation’s Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 is to ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ (UN Citation2015), but its sub-target 4.5 includes Indigenous people only as one among other vulnerable categories. This contradicts the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) that recognises their cultures, cosmologies and livelihoods that deserve to be maintained and nurtured through customised education programmes (UN Citation2007). The lack of specific focus on cultural rights within the SDG4 on education indicates low sensitivity to diverse ontological realities, and inadequate coordination between international objectives within the UN system.

Unifying education policies that do not recognise the epistemic diversity of Indigenous people and other minoritised groups (Gillborn Citation2005) continue the colonial projects in which native and Afro-descendant peoples are not represented (Kerr and Andreotti Citation2018). In multicultural contexts, the standardised schooling designed by the state contributes to distancing children and youths from their territorialities and ancestral knowledges (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018). Therefore, it is crucial to highlight the importance of pluriversal education as a right based on cognitive justice (Zembylas Citation2017) and organised under the institutional control of Indigenous peoples, as also stated in the UNDRIP.

Along these lines, we interpret the accessibility of quality education as an exercise of the right to education encompassing ecological, cultural and linguistic diversities, and supporting the identities, emplacement and territorial control of Indigenous people. These principles should be present at all stages of education as decolonial alternatives for sustainable transformative futures and social justice for all (Nakata et al. Citation2012; Kerr and Andreotti Citation2018).

This study focuses on Ecuadorian Amazonia, where space, place and territorial struggles intersect with the category of indigeneity that is linked to educational disadvantage. Ecuador is a culturally diverse country with 14 Indigenous nationalities and other ethnic identities, including Mestizos, Montubios, Afro-Ecuadorians and Whites. This diversity is recognised in the Constitution that presents Ecuador as a Plurinational State (Republic of Ecuador Citation2008), but in reality, there is no equality among these groups as Mestizos (or White-Mestizos) have been hegemonic in terms of political, economic and cultural power since the colonial era. The modernity/rationality project (Quijano Citation2007) of the State has disempowered Indigenous forms of knowledge, depicting them as primitive, and involved the extraction of natural resources that has caused social and ecological disruptions in the Indigenous territories. Because of this marginalisation, Indigenous people have often adopted identity denial as a coping strategy, to scale up their socio-economic opportunities (Angosto-Ferrandez and Kradolfer Citation2017, 84). In this light, plurinationalism appears as a political goal claimed by Indigenous movements, rather than as an operational platform enforced by the state institutions.

From the Indigenous perspective, territorial sovereignty and deep interculturality are fundamental components of the political project of the Plurinational State of Ecuador. Territorial restitution was partly achieved in 1992, when, after a massive march of Indigenous people from Pastaza province to the capital Quito, the government granted more than one million hectares of land to the Indigenous groups of Amazonia (Whitten, Whitten, and Chango Citation1997). Nevertheless, the central state policy remained hegemonic across the country, and Indigenous organisations contest the lack of sovereignty in their territories, especially in areas ceded by the state to private companies for mining and oil extraction (Altmann Citation2020; Uzendoski Citation2018). In contrast, Indigenous territorialities based on deep connections to land, ancestral knowledges and communication require living languages and cultural practices. Therefore, Indigenous organisations oppose uniform education programmes superimposing external ontologies and epistemological models and strive for a substantial representation of local languages and cultures within intercultural bilingual education (IBE) that is fundamental in the realisation of the Plurinational State.

The spatial proximity of educational opportunities is another important dimension of socio-cultural justice from a territorial perspective. All children and young people should have the right to schooling in their communities or, at least at a reasonable distance from home and safe means to reach it. The type of home-school mobility is also important. Daily school journeys can be characterised as transitional and transformative spaces that are linked to educational aspirations, to the goals and wishes of ‘becoming somebody in life’ (Tuaza Castro Citation2016) and, in the Ecuadorian Amazonian Indigenous context, simultaneously pursuing a life in connection with their own community and the living forest (Gualinga Citation2019).

In this article, we aim to understand and articulate how mobility justice, evaluated in terms of Indigenous people’s access to eco-culturally pertinent education and modes of travel on school journeys, contributes to and is constitutive of territorial justice. Academic research in the field of mobility justice is becoming more diversified (Cook and Butz Citation2019; Verlinghieri and Schwanen Citation2020) and in this study we contribute to this particularly by answering the calls for increasing the understanding of the colonial, neocolonial and neoliberal forces that shape uneven mobilities in the Global South (Sheller Citation2016; Whyte, Talley, and Gibson Citation2019). We focus on observing how the historical and current power relations within educational politics shape Indigenous children’s and young people’s movement and access to schooling in Ecuadorian Amazonia.

We build our argument onan analysis of events of ‘turbulence’ that disrupt educational mobility and access to education within the Indigenous territories in the Pastaza province of Ecuador. We employ turbulence as a conceptual and analytical tool, which characterises the disruption of the normalised order caused by changing mobility patterns or immobility and addresses the issues of justice through its focus on the spatial differences in mobility and the exposure of the underlying politics and power dynamics (Cresswell Citation2006; Cresswell and Martin Citation2012; Ernste, Martens, and Schapendonk Citation2012, 513). Instances of turbulence themselves may also challenge mobility justice, particularly when they disturb mobility and accessibility among the disadvantaged and marginalised groups of the society. The events that we analyse in this study include: 1) an education reform that began during rule of the President Rafael Correa in 2011, which compromised Indigenous people’s access to eco-culturally pertinent education; 2) Indigenous protests linked to territorial struggles that interrupt school journeys dependent on roads and motor vehicles; 3) the Covid-19 pandemic that enforced a rapid transition to distance education. These events make visible the strained relationship between the diverging perceptions of the central government and the Indigenous organisations regarding the right to quality education and the intercultural principles that incorporate territoriality.

Next, we present theoretical and conceptual framework for this study, which is followed by a description of IBE and recent education reforms in Ecuador. Then, we explain the methodological process of our study, and the analysis of the three events of turbulence mentioned above. Finally, we will widen the discussion on the integration of the territorial and mobility approaches to social justice in education as a principle that should be recognised globally to deepen the meaning of quality in education.

Territorial and mobility perspectives on social justice in education

Social justice and decolonising agendas in education could be broadened through the inclusion of the recognitive and representational forms of justice which address the cultural and political dimensions of marginalisation (Cuervo Citation2012; Bastidas Redin Citation2020). Researchers in education in rural areas have also drawn attention to the notion of spatial justice of Soja (Citation2010). Drawing from that concept Roberts and Green (Citation2013) opposed the essentialised constructions of the rural, typically as backward and disadvantageous in terms of education and other socio-economic aspects, also related to the remoteness from the city. In the Amazonian Indigenous context, this could be further explored through the territorial and mobility perspectives of social justice. Territoriality that offers a lens to examine Indigenous ways to exercise symbolic and political control in their territory opposes essentialising notions and extends our understanding beyond the particularities of places by illuminating the dynamics between state and Indigenous territorial strategies (Ulloa Citation2015; Castro-Sotomayor Citation2020). The mobility perspective, on the other hand, helps to understand the multifaceted role of people’s movement in these dynamics, and to detach from the sedentarist conceptions of societies, territories and (in)equalities (Cook and Butz Citation2019).

From the Indigenous perspective, territoriality can be understood as ‘a strategic construction of space produced via spiritual, material, and political dimensions at three different scales: body, territory, and nationalities (Ulloa Citation2015)’ (Castro-Sotomayor Citation2020, 55). Education is set in this scalar framework through the complex interplay between the national educational policies and Indigenous perceptions on eco-culturally pertinent learning as well as through educational mobility that shapes students’ body-territorial experience (Ulloa Citation2016). Castro-Sotomayor (Citation2020) has also characterised territoriality as pragmatic environmental communication, which refers to ‘the pragmatic and constitutive modes of expression – the naming, shaping, orienting, and negotiating – of our ecological relationships with the world, including those with nonhumans systems, elements, and species’ (Pezzullo and Cox Citation2018, 13). Education plays a significant role in forming these relationships and may be used strategically to influence students’ interactions with land (Meek Citation2015). Thus, the educational institutions also participate in constructing students’ eco-cultural identities that are tied to territoriality.

Halvorsen (Citation2018, 5) emphasises ‘the plurality of power relations and political projects (both emancipatory and dominating) through which territory is produced’, which means that a state’s strategies for exercising territorial control may coexist, overlap and entangle with the local Indigenous group’s attempts to appropriate space. Regarding education, the state has the potential either to support Indigenous territoriality by investing in culturally pertinent education in Indigenous territories or to impede it by exercising control on its overlapping national territory, for example, through lack of investment in educational infrastructure or by enforcing its own educational agenda in the Indigenous territories. This may force people to move elsewhere to seek pertinent education, which weakens Indigenous territorial control. This also brings forward the link between territorial and mobility justice that can be evaluated from the perspectives of access and body-territorial relations.

It has been stated that mobility justice is fundamental for achieving ‘access, participation and inclusion’ (Sheller Citation2019, 25) and ‘enabling ‘meetingness” (Cook and Butz Citation2019, 13), both in the society and in ‘post-societal’ contexts, i.e. beyond national or ‘territorially bounded’ (10). The UNDRIP states that ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic, social and cultural life of the State’ (UN (United Nations) Citation2007, article 5, emphasis added), including education (article 14). The realisation of this right to participate requires access supported by ‘networks and mobilities’ (Cook and Butz Citation2019, 12). On the other hand, as the above quote from UNDRIP indicates, Indigenous people also may choose not to participate or at least determine their own level of participation, which may mean continuing living in their ancestral territory and keeping the desired distance, in terms of travel times and cultural difference, to the cities and towns inhabited by the majority population, or even to live in voluntary isolation (Republic of Ecuador Citation2008, chapter 4). (In)access and (im)mobilities are governed by power relations but also shape them (Sheller Citation2019) within the Indigenous population and between the Indigenous people and the wider society. This makes the educational (im)mobility of Indigenous people, in different spatial and structural scales, a highly political issue. It contributes to the construction of the Indigenous presence and participation, their agency and citizenship (Cresswell Citation2013; Bastidas Redin Citation2020).

It is also important to consider mobility justice in the Indigenous context from a body-territorial perspective. Latin American communitarian feminism perceives body and territory as interconnected, ontologically the same, and thus ‘what is done to the body is done to the territory and vice versa’ (Zaragocin and Caretta Citation2021, 1508). Therefore, mobility justice from the Indigenous perspective should also mean the realisation of the right to certain modes of travel and movement that do not cause harm to the territory and allow the creation and maintenance of a bodily connection to it, also on school journeys. These modes include walking, running, cycling and swimming that in western mobilities literature, are often termed as ‘active modes of travel’ (Cass and Manderscheid Citation2019), and have been associated with improved spatial cognition of children and young people (Fang and Lin Citation2017) and with the stimulation of ‘experiences of belongingness, freedom and autonomy, and self-esteem’ (Kwan and Schwanen Citation2016, 251). From the Indigenous perspective, active observational movement across Indigenous land is important for connecting with the natural world and ‘learning with lands/waters and more-than-humans’ (Marin et al. Citation2020, 272). The active movement on school journeys, moving like their ancestors did, through their territory on their own terms also resists the colonial mobility regimes (Clarsen Citation2019) dominated by motorised transportation associated with environmental and social justice problems (Cass and Manderscheid Citation2019) and can thus be considered an enactment of mobility justice from the Indigenous perspective.

In Ecuador, the IBE model has aimed to support Indigenous territoriality through the engagement with local ecological knowledges and ancestral wisdom having relational and holistic understanding of the cosmos (Macas Citation2005; Ministerio de Educación Citation2013; Veintie Citation2013). However, Walsh (Citation2010) distinguishes between deep interculturality, aligned with a decoloniality project, and functional interculturality, which is rather manipulative. The latter in education refers to superficial absorption of cultural practices and values without a curriculum adjusted to the local eco-cultural environment and the use of Indigenous languages in instruction, which cause epistemological challenges in learning. Before 2012, there were more small schools in the communities, which maintained the relationship between communities and education and made them accessible to a larger number of students, which guaranteed mobility justice from the Indigenous perspective. Through the reform of the IBE system that began in 2012, the State’s hegemonic educational policies disregarded the existence of the pluriverse of values and knowledges, compromised the accessibility of eco-culturally pertinent education and thus occupied the Indigenous territories (Bastidas Redin Citation2020; Rodríguez Caguana Citation2011).

Intercultural bilingual education in Ecuador: history of conflicting understandings of education rights

Article 45 of the Ecuadorian Constitution states that ‘Children and adolescents have the right […] to be educated as a priority in their own language and in the cultural context of their own people and nation’. In addition, according to article 347, ‘The responsibility of the State is […] to guarantee the intercultural bilingual education system, where the main language for educating shall be the language of the respective nation and Spanish as the language for intercultural relations, under the guidance of the State’s public policies and with total respect for the rights of communities, peoples and nations’ (Republic of Ecuador Citation2008). These articles mark an important recognition for Indigenous people, but their enforcement has been discontinuous. Observers (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018; Rodríguez Cruz Citation2018) have noted that the 2008 constitution was issued when the intercultural project and, more generally, the historical partnership between central government and Indigenous organisations, were already declining.

Originally, the interest of the Indigenous people in formal education in Ecuador was related to the option to operate independently without intermediaries in negotiations over their land rights and territorial claims (Tuaza Castro Citation2016). In 1944, indigenous leader Dolores Cacuango and feminist pedagogist María Luisa Gómez de la Torre established the first bilingual schools for the Indigenous students in Cayambe, Pichincha province. As the ‘fight for land and liberty’ spread around Ecuador, it became important to establish a school for each Indigenous community where people could learn to read and write in Spanish and thus become able to defend their land against the Mestizos and Whites. The Ministry of Education never recognised the first bilingual schools and they were closed in 1964 by the military dictatorship (Rodas Citation2007).

The project of intercultural bilingual education (IBE) truly re-emerged in 1988, through a collaboration between the Ministry of Education and the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) that introduced the Modelo del Sistema de Educación Intercultural Bilingue (MOSEIB; for a reformed version, see Ministerio de Educación Citation2013) – an educational model aimed to revitalise Indigenous languages, cultures, knowledges, cosmologies and aspirations (Rodríguez Cruz Citation2018). Thus, MOSEIB enhanced the role of education in cultivating students’ social, cultural and language ties to their territories. MOSEIB also proposed pedagogical ideas that are compatible with the Indigenous territorialities, including stronger emphasis on experiential learning and environmental observation, open-air classes, involvement of local experts in the teaching of Indigenous cosmologies and relations with more-than-human beings, practices of agroforestry and handicrafts, closer collaboration between school and students’ families and the community life, and engagement with ceremonies and festivals. Overall, the pedagogical content of MOSEIB is in line with the Indigenous ideology of sumak kawsay that highlights holistic and relational onto-epistemologies, a harmonious human-nature relationship and collective well-being (Viteri Gualinga Citation2002). In addition, the presence of community schools in all rural areas is considered to be fundamental to guarantee access to IBE for all.

However, access to IBE was severely jeopardised during the government of President Rafael Correa in 2007–2017, when CONAIE lost its autonomy over the management of the IBE system and centralised technocratic bureaucracy and modernisation ideology began to dominate the educational policies (Rodríguez Caguana Citation2011; Bastidas Redin Citation2020). In 2011, the parliament issued a new law of intercultural education (Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural, Asamblea Nacional Citation2011) that aimed to improve the quality of education through the revisions of curricula, recruitment of international teachers and researchers, increasing English lessons and construction of new large ‘Millennium schools’ with modern laboratories and other facilities and wider student catchment areas.Footnote1 Simultaneously, approximately 13,000 community schools were closed, which caused enormous problems of access to schooling for children living in communities (Martínez Novo Citation2018). Moreover, the reform ended university-level education for IBE teachers (ibid.) and led to the closure of several universities that did not fulfil the criteria set by the government (Rubaii and Lima Bandeira Citation2018). The Intercultural University of Indigenous Peoples and Nations ‘Amawtay wasi’ (UIAW) was closed in 2013 because, according to the evaluation based on western standards, it did not offer good-quality education (Mato Citation2016; Martín-Díaz Citation2017). At the same time, four new universities were opened with a focus on teacher training, bio-knowledge, technology, and arts, aligned with the Millennium model for higher education (Rodríguez Cruz Citation2018). The subsequent government led by President Lenin Moreno dropped the expensive modernisation policy and relaunched the IBE system with the promise to reopen the community schools.Footnote2 However, these ambitious goals face many challenges because of the persistence of the western ideals of civilisation and modernity (Sarango Macas Citation2019), austerity budget and the lack of teachers with intercultural pedagogical training and language skills due to the closures of IBE teacher education programs. The UIAW will inaugurate its first courses on languages and cultures in the end of 2021. A decentralisation of teaching in different areas of the country will facilitate their accessibility for many and possibly overcome the dilemma between education and territorial belonging.Footnote3

Methodology

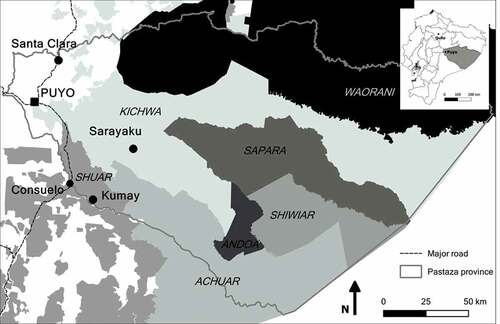

An earlier study indicated that many children have difficult paths to schools in rural areas of Ecuadorian Amazonia (Hagström et al. Citation2016), which prompted our interest to further study the accessibility of education and particularly the impact of education reform on it. In 2018–2020, we produced data on education and mobility in the Kichwa and Shuar communities of Pastaza province () in collaboration with the Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA) based in Puyo. During the field visits, we noticed that Indigenous children’s and young people’s access to school is not only tied to educational policies but is also affected by a complex and intertwined set of factors that are linked to the general marginalisation of Indigenous people in the society. Our attention was especially drawn to the frequent demonstrations on the streets that blocked educational mobility for days and weeks in September and October 2019 as well as the Covid-19 pandemic that reached Ecuador in March 2020 and caused a national lockdown and rapid transition to distance education.

Figure 1. Map of Pastaza province and its Indigenous territories (source of territory borders GIS data: RAISG 2020)

In his writing on the Mobile Lives Forum on March 18, 2020, Tim Cresswell characterised Covid-19 as turbulence that disrupts ‘the established and largely taken for granted mobilities of everyday life’. Mobility turbulence makes visible the logics of smooth and predictable movements and thus can reveal ‘much that is wrong with the ways we move’.Footnote4 In general, ‘turbulence’ can be characterised as a ‘bridging’ or a ‘meso-theoretical’ concept, which ‘shows how the different ordering and disordering forces create different degrees of mobilities and immobilities, different designs of mobility and different inclusions and exclusions of mobility’ (Cresswell and Martin Citation2012; Ernste, Martens, and Schapendonk Citation2012, 513). The analytical potential of the concept extends to the realm of complex societal dynamics and power relations revealing, not only things that are wrong with the ways we move, but also the underlying politics (Cresswell and Martin Citation2012). In this article, we harness turbulence as a conceptual and analytical tool for characterising and studying education reform, protests and the Covid-19 pandemic in Ecuador. These three events have disrupted the educational mobility of the Indigenous students and continue to affect their access to education. At the same time, they make visible the problems of justice, opening an opportunity to envision alternative ways to organise education and mobility.

Our study draws from a review of earlier studies of the education reform and its impact on Indigenous communities. The impact of school closures on educational accessibility has previously been studied, particularly in the Sierra (e.g. Tuaza Castro Citation2016; Granda Merchán Citation2018; Bastidas Redin Citation2020). Certain consequences, such as the longer school journeys, increasing costs of travel, worse nutrition and discrimination, also apply to the Amazonian region. However, their nuances are tied to the socio-cultural and geographical settings. In addition, our study draws from the interviews and discussions with the members of the Indigenous communities on the education reform process, from spatial field observations and home-school walks with upper secondary school students, and from expert interviews with people working in educational institutes and administration. The case of Covid-19 was followed remotely. The research followed the ethical principles in human sciences (TENK Citation2019) approved by the funding organisation. The study included only participants older than 15 years of age (including the students) and verbal or written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The data were anonymised and the privacy of the participants protected. In the Indigenous communities we visited, the research team followed the appropriate cultural norms and sought permission to conduct the study from the community leaders and school directors.

Finally, we need to recognise the role of our own bodies as mobile knowledge producing subjects in the research process. The composition of our field research team varied between school visits, but most of us were non-Indigenous. Only two team members belonged to the Indigenous Kichwa nationality, but they mainly reside in the city. For example, travels with the students to their homes after school in tropical forested areas often turned out to be a large physical exertion for our bodies that are accustomed to a relatively sedentary metropolitan office-life in Europe and Ecuador. Moving in the forest and jumping over rivers or surfing in a crowded recklessly driven bus required bodily skill that our group members did not have, unlike the students who were often very skillful movers and whose bodies had adjusted to their living environment. Therefore, our perspective for observing distance and accessibility of education is likely to be different from that of the local students, and we cannot claim to understand their body-territorial mobility experience completely. Nevertheless, the normalisation of the dominance of motor traffic and long school journeys does not mean that problems would not exist and thus we hope that our outsiders’ analysis of the events of mobility turbulence will draw attention to the underlying injustices.

Turbulent events affecting accessibility of education

Event 1: education reform

At the time when the government decided that the small schools would be merged to the Millennium schools, they said that our school had very few students and did not meet the requirements. […] They arrived with practically no notice […] to say that they came to close the school. (Interview with a community member, Shuar territory, 20 March 2019, translated from Spanish)

The quote above is from the account of a member of the Shuar community in Consuelo who told us about the government’s intentions to close down the local primary school and move the children to a larger school because of the education reform. This community, as many others, resisted school closures by organizing demonstrations and, after long negotiations, it managed to keep its school open. Many other schools in the Shuar territory and in Pastaza, however, were closed and some were also merged into one educational unit. Some schools that the government did not first intend to close were also eventually closed only because the parents anticipated their closure and enrolled their children in other schools (interview with the director of an educational district, January 31, 2019). The statements of Correa that labelled the community schools as ‘the schools of poverty’ (Granda Merchán Citation2018, 298) and the creation of new large Millennium schools with attractive modern facilities, often in the oil block areas (Lang Citation2017; Granda Merchán Citation2018; Bastidas Redin Citation2020), enforced this pattern. In Pastaza, the closed units were mainly primary schools, but the increasing drop-out rates at this level have probably affected the numbers of students entering secondary, upper secondary and higher education.

The education reform was driven by the government’s intention to provide quality education for all and to increase the enrolment rate, especially in Ecuador’s marginalised areas. However, instead, it caused turbulence that compromised both the cultural relevance and accessibility of education in Indigenous areas. The authorities justified the school closures typically with a small number of students or teachers and/or if two or more schools were relatively close to each other (Tuaza Castro Citation2016). Based on cartographic analysis, the Ministry of Education determined which schools should remain and where the new ones would be established (Ministerio de Educación Citation2012). However, the measurement of distances between communities and school locations based on coordinate points did not consider the environmental and social conditions that affect the real accessibility between the points on the ground (Tuaza Castro Citation2016; Granda Merchán Citation2018). Thus, the spatial redistribution of schools was based on a masculinised power-geometrical gaze over territory that marginalised the local Indigenous knowledge (Jackman et al. Citation2020). The mountainous and hilly topography of the country and particularly the numerous rivers in the Amazonian region, pose severe challenges for travel, especially in rural areas with inadequate or poorly maintained road infrastructure. Road connections, where they existed or could be constructed, also justified the extension of home-school distances during the spatial reorganisation of education even though the road did not always guarantee easy access to schools. For example, the Puyo-Macas highway (E45) that traverses the Shuar territory in the eastern part of Pastaza makes the schools along it seem accessible on a map. However, especially for the smallest students, the reality is very different, as they do not always live along the highway but deeper in the forest. The government also failed to guarantee adequate and inexpensive transportation to them:

When the government of Correa began to create Millennium schools in large communities, they said they would close the small ones and that they will give buses to all the students. From here, they went to Chuwitayo but the proposal of Correa turned out to be a lie, as there was no car for the students. […] The other centre is far away and sometimes we have problems with the [public] buses, which do not take the children, and they do not go to school two, three days […], and if they do not take a bus, they do not leave, they fall behind, and they lose the year. (Community member at a closed primary school, Shuar territory, 20 March 2019, translated from Spanish)

Even in semi-urban and urban areas, due to the lack of resources, schools have problems in providing transportation for all the students who live in remote communities. For example, this is the case in the Camilo Huatatoca school in Santa Cara, whose number of students grew from less than a hundred up to 500 due to the closure of schools in the communities of Pueblo Unido and Rey del Oriente (Interview with the school director, April 1, 2019).

Education reform illuminated the lack of recognition of the Indigenous territorial principles and rights in the State’s education policy. The closure of community schools made the school journeys longer and increased Indigenous people’s migration to towns, which meant more involvement in the monetary economy due to higher expenditure on transportation and/or higher living costs, which contributed to increasing poverty (Tuaza Castro Citation2016). Lack of access to culturally pertinent education also increased school dropout rates due to discrimination, lack of feeling secure in a strange learning environment and the demands for standardised education, especially in subjects like mathematics (Tuaza Castro Citation2016; Granda Merchán Citation2018; Bastidas Redin Citation2020). Because of new requirements for teacher training, it has also been difficult to find Indigenous and local teachers to teach in IBE schools. For example, the local elders or wise people of the communities are not recognised as teachers by the formal education system. Instead, the Mestizo teachers from other parts of the country are assigned to teaching positions in Indigenous areas of Amazonia. We noticed that the teachers who had arrived from outside sometimes expressed a lack of motivation and did not have the knowledge of the local culture and language and thus ended up enforcing Hispanic education in IBE schools.

From the territorial perspective, the most severe consequence of the education reform is that cultural and physical distancing is likely to weaken the linkage between learning and the fight for the land that has been the core goal of Indigenous people’s education since the 1940s. Because of the decrease in the educational opportunities in the local communities, the number of people capable of defending their territories and fighting against injustices is decreasing due to migration to larger towns. In Amazonia, this serves the interests of the state and large companies who wish to appropriate Indigenous lands for oil extraction, mining and hydropower production (Lang Citation2017) and thus the conversion of the Indigenous territory into the ‘state-space’ (Castro-Sotomayor Citation2020). The Indigenous leaders of Ecuador have strongly protested about it being impossible for their children to follow the culturally and territorially pertinent IBE (Bastidas Redin Citation2020), but it remains to be seen what its effect will be.

Event 2: indigenous protests

In mid-September 2019, our research team visited the Camilo Huatatoca school in Santa Clara for one week. One morning, our journey to the school was interrupted by a roadblock on the Puyo-Tena highway (E45), which stopped all the motor traffic, including the buses that were carrying the students and us to the school. The blockade was set up by the local Kichwa community as part of a protest that had continued already for five years against the hydropower project plan on the Piatúa River by the company Generación Eléctrica San Francisco (GENEFRAN S.A.). The Piatúa River has a high cultural value for the local Kichwa people, and it is a strategic hotspot for environmental conservation because its ecosystem provides a habitat for various endemic species (Paz Cardona Citation2019). The blockade on a major road represented a means to take over control and draw national attention to the activities that threaten the cultural and natural values of the river. The demonstration continued for two days during which the local schools remained closed.

Two weeks later, on October 3, our research team witnessed the beginning of the national strike against the removal of subsidies for petroleum and rising living costs, which lasted for 11 days and was characterised by severe police violence (Altmann Citation2020). Major roads across the country were blocked, public buses did not move and schools and universities stayed closed. Moving between large centres was difficult unless you were privileged enough to be able to pay for expensive private drivers who found alternative routes. Indigenous organisations actively participated in the protests from the beginning and continued them after the transportation sector that had initiated the strike retreated with compensatory measures. For the Indigenous groups, the strike was primarily about resistance against neoliberal economic measures proposed by the government that would have hit the poor hardest and jeopardised the construction of the Plurinational State (Altmann Citation2020; Ponce et al. Citation2020).

Both of these protests were fuelled by the trampling of the rights of Indigenous people, and thus, they illustrate well how social and territorial injustices drip down and violate children’s access to education. However, this is a side effect that goes almost unnoticed, while there are more urgent things to take care of. While autumn 2019 was somewhat exceptional whole Latin America in terms of social unrest that sparked mobility turbulence (Altmann Citation2020), it drew attention to the need for social stability that guarantees safe and uninterrupted school journeys, and thus mobility justice. The protests also made visible the dependence of the educational and other mobilities on motor vehicles. Especially in or close to urban areas, school journeys occur in the same space where private cars, taxis, trucks and buses dominate the streets. Access to education in these areas largely depends on bus or car services, not only because of the distance, but because in that sometimes chaotic space, there are not many opportunities for the safe alternative and active modes of travel such as walking and cycling, which creates a condition of mobility injustice (Sheller Citation2019). Even though buses and cars provide better and safer access to schools far away from the Indigenous communities than other modes of travel, the road connections and motor traffic also seem to increase cultural erosion and resource extraction in Indigenous areas. For example, the extensive felling of timber was visible in the Shuar community of Kumay where the connection to the Puyo-Macas highway was constructed only a few years ago. In contrast, the Kichwa community of Sarayaku has resisted the construction of the road connection and has thus retained a higher degree of cultural integrity and environmental protection.

The Indigenous protests have normally led to intense negotiations between Indigenous representatives and state authorities. While they have sometimes led towards alleviating the societal inequalities and enhancement of Indigenous territorial rule, as in the case of the October strike (Altmann Citation2020; Ponce et al. Citation2020), they have not directly addressed the dependence on motor vehicles. However, in the context of the October strike, the Indigenous organisations made a statement in which they announced that petrol exploitation is the root cause of the current problems and demanded a ‘post-petrol economic model’ that also respects the principles of sumak kawsay and plurinationalism (Altmann Citation2020, 224).

Event 3: Covid-19 pandemic

In 2020, the difficult access to education in remote areas of Amazonia gained a new dimension when the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted normal everyday mobility. In mid-March, the Ecuadorian government suspended classes at all levels and declared a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the virus (Asanov et al. Citation2020; Benítez et al. Citation2020). Like in other countries worldwide, teaching in Ecuadorian schools was organised remotely through the Internet or other media such as television, radio or printed materials.

The rapid transition to distance schooling has raised concerns over the widening educational inequalities in Ecuador. The results of the initial survey indicated that especially in remote areas, Indigenous students lacked access to remote learning technologies, which increased their risk of falling behind and dropping out from school (Asanov et al. Citation2020). In May–June 2020, our research team conducted a round of phone surveys with the directors of nine IBE upper secondary schools in Pastaza. It revealed that most students and teachers, especially those who live in rural areas, had problems with access to the Internet and technical devices, and thus, in nearly half of the schools, none of the students participated in virtual education. To continue studying, most students relied on printed learning materials. However, teachers at several schools had problems printing and delivering them to the students, which caused interruptions in learning activities for several days or even months (Machoa, et al., Citation2021). Another survey for the students of UEA indicated problems with access to technological devices also within higher education.4

The Covid-19 pandemic has drawn attention to the digital divide between Indigenous people and the majority population in Ecuador as well as to the lack of State’s investment in education in remote areas of the Indigenous territories. Amid the health and economic crises linked to Ecuador’s pre-pandemic indebtedness to the International Monetary Fund (Benítez et al. Citation2020), in the early stages of the pandemic the government did not express any interest in providing economic support to vulnerable groups nor improving access to distance education. Instead, there were targeted budget cuts to the education sector (Aguirre Rea, Zhindon Palacios, and Pomaquero Yuquilema Citation2020). Despite the lack of state initiatives, UEA organised transportation to take students back to their communities and provided them with tablets and connecting devices (personal communication with rector of UEA, April 22, 2020). However, the transfer of devices faced challenges because some students were not reached, while others felt signing the lease to be intimidating.4 Currently, many students communicate with the teachers through WhatsApp and it seems that after the most critical times, a new student mobility pattern has emerged, between the households and points of Internet. However, wide areas of Amazonia still have no connectivity, and therefore such mobility does not reduce the potential increase in the number of students dropping out. On September 10, 2020, the Ministry of Telecommunications and the Information Society announced a plan on its website to invest in increasing digital connectivity in the whole country, but so far, its implementation has been limited.

It must be noted that the mere distribution of devices and access to the Internet does not close the digital divide between student groups, but access to equitable support, encouragement and safe and culturally relevant digital learning content are also crucial (Gorski Citation2005). Furthermore, face-to-face teaching is better for supporting learning, and earlier experiences of virtual higher education in indigenous areas have proven to be ineffective (personal communication with a teacher from the Salesian Polytechnic University, September 11, 2019). Even though many Indigenous students are currently active users of the Internet and social media services such as Facebook and WhatsApp, it does not mean that they would be able to study independently online, when they lack support for reading, understanding and producing academic texts.

Discussion

The centralising and modernising tendencies of education reform have contributed to the adverse impacts of the Indigenous protests and the Covid-19 pandemic on educational mobility and accessibility in Ecuadorian Amazonia. The scrutiny of these events suggests that it would be important to reconsider the social justice agenda of education in Ecuador from the Indigenous territorial and mobility perspectives.

Correa’s investment in education was important, but within a logic of ‘extractivist developmentalism […] with calls for social justice, often within a socialist discourse, but which at the same time rejected environmental and ecological justice goals as well as minority rights’ (Gudynas Citation2019, 4). The spatial re-organisation of education during the education reform was founded on the distributive approach on social justice (Roberts and Green Citation2013) with essentialised perception on the educational disadvantage of marginalised and Indigenous areas whereby their needs were determined in relation to the values of modernity and homogenised standards set by the centralised governance (Bastidas Redin Citation2020). The aim of the reform was the standardisation of educational content, educational pathways, learning environments and to some extent, even the school journeys. The closure of community schools converted education into a privilege of the wealthy and of those who live in the regional centres or in the cities, contradicting the right to education stated in the constitution and in the SDG4 (Tuaza Castro Citation2016). For many Indigenous people who live in remoter areas, it meant facing the core dilemma of mobility and territorial justice from an Indigenous perspective because it forced them to make the difficult decision between moving closer to school or staying in their home community without access to education. Therefore, instead of exercising the right to eco-culturally pertinent education, access to education came to mean ‘access to privilege’ grounded on the frame of modernity (Ahenakew Citation2017, 81). Consequently, the educational aspiration of the Indigenous students ‘to become somebody in life’ (Tuaza Castro Citation2016) became to mean, ‘to become less Indigenous’, which contradicts the idea of the Plurinational State.

From the perspective of territorial and mobility justice, it would be important to bring eco-culturally pertinent education physically closer to the Indigenous communities, such as by re-establishing the community schools up to the final grades and enforcing the IBE agenda in them. Eco-culturally and territorially pertinent quality education would be characterised by diverse school calendars organised in modules following the local agroforestry cycles and festivities, instead of academic years, by pedagogies based on experiential learning through outdoor practices, Indigenous philosophies and cosmologies, and by integrated subjects, instead of disciplinary-framed topics, taught in the language of the nationality, and in close cooperation with the communities (and their wise, elderly, shamans and expert members) where the schools are located. This educational model would also respect seasonal cycles challenging school attendance, such as heavy rains and flooding, or periods of harvesting, hunting, fishing or other activities. Organising quarterly modules instead of calendar years would allow temporary suspension of the studies, limiting dropping out. This model corresponds to the practice of indigenous education that had originally inspired the IBE model. Some educational units have relaunched it as part of a larger territorial plan for the kawsak sacha (living forest).Footnote5 The restarting of UIAW courses on intercultural education will prepare new teachers that will be able to connect education with territoriality3.

However, suggesting that schools should be closer to communities is not to argue for sedentarism or to defend localism ‘hostile to mobilities’ (Cresswell Citation2020, 10). On the contrary, frequent movement and extra-local mobilities between the home community and farms further away as well as fishing and hunting trips, are part of Indigenous territoriality in Amazonia. While the longer school journeys caused by the education reform have seemingly increased the mobility of some students, especially the travels on the bus may be perceived as a form of sedentarism on the move, which challenges Indigenous mobility justice particularly from a body-territorial perspective. Motor vehicles and roads represent attempts ‘to produce order and predictability’ to channel motion (Cresswell and Martin Citation2012, 520) that is in contrast with walking that allows the more spontaneous and unexpected ‘creative adventures’ (Cresswell Citation2020; Massumi Citation2018), learning from the surrounding environment (Marin et al. Citation2020) and creating connections to the territory. In addition, encounters with occasions of turbulence of various types and magnitudes, such as floods and dangerous animals, are part of the mobility system and embodied learning process in the Amazonia.

Bringing educational opportunities closer to communities, however, could reduce the dependency on motor vehicles and mobility turbulence on the roads. The general detachment from the dominance of motor traffic would be important, not just for enabling the safe active modes of travel, but also for decolonising the space because, the current Ecuadorian mobility infrastructure has been built to serve the globalised hegemony of motor cars and oil dependency (Miller and Ponto Citation2016) as well as the urban development of new oil-based towns and the Millennium schools in them. The road infrastructure that is built in terms of motor vehicles is a physical manifestation of the power of petroleum on everyday travels (Huber Citation2013), the power that also threatens the Indigenous territories through increased cultural erosion, resource extraction and climate change (Mena et al. Citation2017).

The territorial and mobility approaches to social justice in education would also support the improvement of virtual and other distance education opportunities especially in those areas where the establishment of schools is not meaningful. It would also guarantee the continuation of studies during wide-scale crises such as the global pandemic. The current digital exclusion ofAmazonian Indigenous groups is part of the broader economic and social exclusion ofIndigenous people around the world (Resta and Laferrière Citation2015). However, Gorski (Citation2009) has warned against hailing computers and the Internet as ‘the great equalisers’ before ‘critical examination of the ways in which a growing reliance on these technologies may contribute to the very inequities multicultural education is supposed to eliminate’. While it is necessary for the younger generations to learn the technical skills and to understand how the digitised world operates, also to defend their own territories, the increasing access to the Internet that privileges the Spanish and English languages and Western knowledge systems may also contribute to digital neocolonialism and cultural erosion (Resta Citation2011; Adam Citation2019). However, information and communication technologies may also be supportive of Indigenous cultures and languages when they are employed under the control of Indigenous people and serve their purposes (Resta Citation2011).

Conclusion

In this article, we have discussed three events of turbulence that have affected educational mobilities and accessibility in Ecuador. These events expose the problems of spatial organisation of education, and the underlying political dynamics, from the territorial and mobility justice perspectives. The education reform and the associated reduction of eco-culturally pertinent education opportunities and extension of school journeys draw attention to the discrepancy between the Indigenous territoriality and the State’s assimilative modernisation ideology. The education reform also increased the dependence on motor vehicles on school journeys, which has contributed to the emergence of a second type of mobility turbulence related to Indigenous protests that employ roadblocks and transportation stoppages as strategic means to take over control. It points to the need for social justice and stability that guarantee the success of everyday school journeys. The third and most recent mobility turbulence, triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, brings attention to the lack of state support for education in remote areas and the digital divide in Ecuadorian society.

Making schooling accessible and flexible in accordance with the livelihoods, mobilities and temporalities of indigenous students would mean alleviating the burden of dramatic choices between education and indigeneity, territoriality, and sumak kawsay. Justice for indigenous youths requires educated professionals from their native territories to fight for their lands. Survival and transmittance of indigenous knowledge will improve the control over the environmental resources, agency and resilience to confront turbulence caused by global environmental change and extractivism. We would like to think that these turbulent times provide humanity with several ‘moments of creativity’ (Cresswell Citation2006) that open the possibility to proceed towards a more just future.

Above all, the realisation of both mobility and territorial justice means the opportunity to make sustainable life choices that do not force uprooting of Indigenous people from their territories but allow access to education and thus participation in the wider society. In addition, mobility justice means the possibility to move in a sustainable way that allows the creation and maintenance of body-territorial connection and learning without damaging the environment. Territorial and mobility justice perspectives should be integrated into the social justice agenda of quality education globally. This would allow the emergence of reformative actions that move beyond the essentialised constructions of the social and educational disadvantages of the Indigenous areas and people, and instead, recognise the particularities of Indigenous places and mobilities and support Indigenous territorial strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Kichwa and Shuar communities who participated in the research and shared their valuable stories and knowledge. Experts on IBEs are also thanked for the interviews and sharing their knowledge. The research team members Tuija Veintie, Katy Machoa, Andrés Tapia, Nathaly Pinto, Tito Madrid and Ruth Arias and the assistants are also thanked for their contributions to the fieldwork and insightful discussions and feedback. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions on how to improve the article before publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The reform did not follow any participatory process. The involvement of a few indigenous members in ministerial boards was stigmatised by CONAIE as a governmental strategy of political infiltration aimed to divide the indigenous movement (‘Con el “levantamiento” contra Rafael Correa los indígenas buscan recuperar protagonismo politico.’ El Comercio, 19 July 2015, 1. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/politica/conaie-levantamiento-indigenas-paro-rafaelcorrea.html)

2. Heredia, V. 2019. ‘Moreno anuncia la reapertura de escuelas rurales en Ecuador.’ El Comercio, January 30. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/moreno-anuncia-reapertura-escuelas-rurales.html

3. Universidad Amawtay Wasi – Universidad en los territorios: https://www.uaw.edu.ec/comunidad-en-accion

4. Pinto, N. 2020. ‘The pandemic and the right to inclusive education: identifying participatory design interventions against structural marginality and infrastructural weaknesses.’ Eco-cultural pluralism in Ecuadorian Amazonia, July 31. https://blogs.helsinki.fi/ecocultures-ecuador/2020/07/31/the-pandemic-and-the-right-to-inclusive-education-identifying-participatory-design-interventions-against-structural-marginality-and-infrastructural-weaknesses

5. Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku. 2016. Kawsak Sacha – Living forest. Pastaza, Ecuador. https://kawsaksacha.org

References

- Adam, T. 2019. “Digital Neocolonialism and Massive Open Online Courses (Moocs): Colonial Pasts and Neoliberal Futures.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (3): 365–380. doi:10.1080/17439884.2019.1640740.

- Aguirre Rea, D. H., L. A. Zhindon Palacios, and J. C. Pomaquero Yuquilema. 2020. “COVID-19 Y La Educación Virtual Ecuatoriana.” IAC Investigación Académica 1 (2): 53–63.

- Ahenakew, C. R. 2017. “Mapping and Complicating Conversations about Indigenous Education.” Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education 11 (2): 80–91. doi:10.1080/15595692.2017.1278693.

- Altmann, P. 2020. “Eleven Days in October 2019 – The Indigenous Movement in the Recent Mobilizations in Ecuador.” International Journal of Sociology 50 (3): 220–226. doi:10.1080/00207659.2020.1752498.

- Angosto-Ferrandez, L. F., and S. Kradolfer. 2017. The Politics of Identity in Latin American Censuses. New York: Routledge.

- Asamblea Nacional,. 2011 Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural. Segundo suplemento, No 417, 31 de Marzo. Quito: Registro Oficial Organo del Gobierno del Ecuador.”

- Asanov, I., F. Flores, D. McKenzieb, M. Mensmann, and M. Schulte. 2020. “Remote-Learning, Time-Use, and Mental Health of Ecuadorian High-School Students during the COVID-19 Quarantine” Policy Research Working Paper, 9252. Washington DC: World Bank. Accessed 9 July 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33799

- Bastidas Redin, M. C. 2020. “Dilemmas of Justice in the Post-Neoliberal Educational Policies of Ecuador and Bolivia.” Policy Futures in Education 18 (1): 51–71. doi:10.1177/1478210318774946.

- Benítez, M. A., C. Velasco, A. R. Sequeira, J. Henríquez, F. M. Menezes, and F. Paolucci. 2020. “Responses to COVID-19 in Five Latin American Countries.” Health Policy and Technology 9 (4): 525–559. doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.014.

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2019. “The Autonomobility System. Mobility Justice and Freedom under Sustainability.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 101–115. New York: Routledge.

- Castro-Sotomayor, J. 2020. “Territorialidad as Environmental Communication.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (1): 50–66. doi:10.1080/23808985.2019.1647443.

- Clarsen, G. 2019. “Black As: Performing Indigenous Difference.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 159–172. New York: Routledge.

- Cook, N., and D. Butz. 2019. “Moving Toward Mobility Justice.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 3–21. New York: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T., and C. Martin. 2012. “On Turbulence: Entanglements of Disorder and Order on a Devon Beach.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 103 (5): 516–529. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2012.00734.x.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. One the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. London: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T. 2020. “Valuing Mobility in a Post COVID-19 World.” Mobilities 16 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1863550.

- Cresswell, T. 2013. “Citizenship in Worlds of Mobility.” In Critical Mobilities, edited by O. Soderstrom, S. Randeria, D. Ruedin, G. D’Amato, and F. Panese, 105–124. London and New York: Routledge.

- Cuervo, H. 2012. “Enlarging the Social Justice Agenda in Education: An Analysis of Rural Teachers’ Narratives beyond the Distributive Dimension.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 40 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2012.669829.

- Ernste, H., K. Martens, and J. Schapendonk. 2012. “The Design, Experience and Justice of Mobility.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 103 (5): 509–515. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2012.00751.x.

- Fang, J.-T., and J.-J. Lin. 2017. “School travel modes and children's spatial cognition.” Urban Studies 54 (7): 1578–1600. doi:10.1177/0042098016630513.

- Gillborn, D. 2005. “Education Policy as an Act of White Supremacy: Whiteness, Critical Race Theory and Education Reform.” Journal of Education Policy 20 (4): 485–505. doi:10.1080/02680930500132346.

- Gorski, P. 2005. “Education Equity and the Digital Divide.” AACE Journal 13 (1): 3–45.

- Gorski, P. 2009. “Insisting on Digital Equity: Reframing the Dominant Discourse on Multicultural Education and Technology.” Urban Education 44 (3): 348–364. doi:10.1177/0042085908318712.

- Granda Merchán, J. S. 2018. “Transformaciones de la educación comunitaria en los Andes ecuatorianos.” Sophia: Colección De Filosofía De La Educación 24 (1): 291–311. doi:10.17163/soph.n24.2018.09.

- Gualinga, P. 2019. “Kawsak Sacha.” In Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary, edited by A. Kothari, A. Salleh, A. Escobar, F. Demaria, and A. Acosta, 223–226. New Delhi: Tulika Books.

- Gudynas, E. 2019. “Value, Growth, Development: South American Lessons for a New Ecopolitics.” Capitalist Nature Socialism 30 (2): 234–243. doi:10.1080/10455752.2017.1372502.

- Hagström, O., A. Ropponen, M. Rönnberg, and E. Saari. 2016. “Accessibility to Schools for Kichwa Pupils of Santa Clara, Ahuano and Sarayaku in Ecuadorian Amazonia.” In Cultures, Environment and Development in the Transition Zone between the Andes and the Amazon of Ecuador. Field Trip 2015, edited by A. Häkkinen, P. Minoia, and A. Sirén, 44–59. Department of Geosciences and Geography C 12. Helsinki: Department of Geosciences and Geography, University of Helsinki.

- Halvorsen, S. 2018. “Decolonising Territory: Dialogues with Latin American Knowledges and Grassroots Strategies.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (5): 790–814. doi:10.1177/0309132518777623.

- Huber, M. 2013. Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom and the Forces of Capital. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Jackman, A., R. Squire, J. Bruun, and P. Thornton. 2020. “Unearthing Feminist Territories and Terrains.” Political Geography 80: 102180. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102180.

- Kerr, J., and V. Andreotti. 2018. “Recognizing More-Than-Human Relations in Social Justice Research. Gesturing Towards Decolonial Possibilities.” Issues in Teacher Education 27 (2): 53–67.

- Kwan, M.-P., and T. Schwanen. 2016. “Geographies of Mobility.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2): 243–256. doi:10.1080/24694452.2015.1123067.

- Lang, M. 2017. ¿Erradicar la pobreza o empobrecer las alternativas? Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Sede Ecuador, Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Macas, L. 2005. “La necesidad política de una reconstrucción epistémica de los saberes ancestrales.” In Pueblos Indígenas, Estado y Democracia, edited by P. Dávalos, 35–42. Buenos Aires: Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales.

- Machoa, K., T. Veintie, and J. Hohenthal. 2021. “La educación desde los territorios amazónicos en tiempos de pandemia.” In Los pueblos indígenas de Abya Yala en el Siglo XXI. Un análisis multidimensional, edited by M. Rodriguez-Cruz., 53-64. Quito: Abya-Yala & Fundación Pueblo Indio del Ecuador.

- Marin, A., K. H. Taylor, B. R. Shapiro, and R. Hall. 2020. “Why Learning on the Move: Intersecting Research Pathways for Mobility, Learning and Teaching.” Cognition and Instruction 38 (3): 265–280. doi:10.1080/07370008.2020.1769100.

- Martín-Díaz, E. 2017. “Are Universities Ready for Interculturality? The Case of the Intercultural University ‘Amawtay Wasi’ (Ecuador).” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 26 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1080/13569325.2016.1272443.

- Martínez Novo, C. 2018. “Ventriloquism, Racism and the Politics of Decoloniality in Ecuador.” Cultural Studies 32 (3): 389–413. doi:10.1080/09502386.2017.1420091.

- Massumi, B. 2018. 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value: A Postcapitalist Manifesto. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mato, D. 2016. “Indigenous People in Latin America: Movements and Universities. Achievements, Challenges, and Intercultural Conflicts.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (3): 211–233. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1163536.

- Meek, D. 2015. “Learning as Territoriality: The Political Ecology of Education in the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (6): 1179–1200. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.978299.

- Mena, C. F., F. Laso, P. Martinez, and C. Sampedro. 2017. “Modeling Road Building, Deforestation and Carbon Emissions Due Deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The Potential Impact of Oil Frontier Growth.” Journal of Land Use Science 12 (6): 477–492. doi:10.1080/1747423X.2017.1404648.

- Mignolo, W., and C. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Miller, B., and J. Ponto. 2016. “Mobility among the Spatialities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2): 266–273. doi:10.1080/00045608.2015.1120150.

- Ministerio de Educación. 2012. Reordeniamento de la oferta educativa. Quito: Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador.

- Ministerio de Educación. 2013. MOSEIB. Modelo Del Sistema De Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Quito: Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador.

- Nakata, N. M., V. Nakata, S. Keech, and R. Bolt. 2012. “Decolonial Goals and Pedagogies for Indigenous Studies.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 120–140.

- Paz Cardona, A. J. 2019. “Pleito: Indígenas Kichwa se oponen a polémica hidroeléctrica en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana” MONGABAY Accessed 9 July 2021,. https://es.mongabay.com/2019/07/hidroelectrica-rio-piatua-amazonia-ecuador-kichwa

- Pezzullo, P. C., and R. Cox. 2018. Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ponce, K., A. Vasquez, P. Vivanco, and R. Munck. 2020. “The October 2019 Indigenous and Citizens’ Uprising in Ecuador.” Latin American Perspectives 47 (5): 9–19. doi:10.1177/0094582X20931113.

- Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 168–178. doi:10.1080/09502380601164353.

- RAISG (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada). 2020. “Datos Cartográficos” Accessed 23 February 2020. https://www.amazoniasocioambiental.org/es/mapas/#descargas

- Republic of Ecuador. 2008. “Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador” October 20. Accessed 9 July 2021.http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html

- Resta, P. 2011. “ICTs and Indigenous Peoples.” UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education Policy Brief. UNESCO, June.

- Resta, P., and T. Laferrière. 2015. “Digital Equity and Intercultural Education.” Education and Information Technologies 20 (4): 743–756. doi:10.1007/s10639-015-9419-z.

- Roberts, P., and B. Green. 2013. “Researching Rural Places: On Social Justice and Rural Education.” Qualitative Inquiry 19 (10): 765–774. doi:10.1177/1077800413503795.

- Rodas, R. 2007. Dolores Cacuango. Pionera En La Lucha Por Los Derechos Indígenas. Quito: Crear Gráfica.

- Rodríguez Caguana, A. 2011. “El derecho a la educación intercultural bilingüe en el Ecuador.” Ciencia UNEMI 4 (5): 54–61. doi:10.29076/.2528-7737vol4iss5.2011pp54-61p.

- Rodríguez Cruz, M. 2018. Educación Intercultural Bilingue, Interculturalidad Y Plurinacionalidad En El Ecuador. Quito: Abya Yala.

- Rubaii, N., and M. Lima Bandeira. 2018. “Comparative Analysis of Higher Education Quality Assurance in Colombia and Ecuador: How Is Political Ideology Reflected in Policy Design and Discourse?” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 20 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1080/13876988.2016.1199103.

- Sarango Macas, L. F. 2019. “La universidad intercultural Amawtay Wasi del Ecuador, un proyecto atrapado en la colonialidad del poder.” Revista Universitaria Del Caribe 23 (2): 31–43. doi:10.5377/ruc.v23i2.8929.

- Sheller, M. 2016. “Uneven Mobility Futures: A Foucauldian Approach.” Mobilities 11 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1080/17450101.2015.1097038.

- Sheller, M. 2019. “Theorising Mobility Justice.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 22–36. New York: Routledge.

- Soja, E. W. 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- TENK (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity). 2019. The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland. Helsinki: TENK.

- Tuaza Castro, L. A. 2016. “Los impactos del cierre de escuelas el medio rural.” Ecuador Debate 98: 83–95.

- Ulloa, A. 2015. “Environment and development: Reflection from Latin America.” In Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by T. A. Perreault, G. Bridge, and J. McCarthy, 320–331. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Ulloa, A. 2016. “Feminismos territoriales en América Latina: Defensas de la vida frente a los extractivismos.” Nómadas (45): 123–139. doi:10.30578/nomadas.n45a8.

- UN (United Nations). 2007. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- UN (United Nations). 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 Accessed 9 July 2021.

- Uzendoski, M. A. 2018. “Amazonia and the Cultural Politics of Extractivism: Sumak Kawsay and Block 20 of Ecuador.” Cultural Studies 32 (3): 364–388. doi:10.1080/09502386.2017.1420095.

- Veintie, T. 2013. “Practical Learning and Epistemological Border Crossings: Drawing on Indigenous Knowledge in Terms of Educational Practices.” Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education 7 (4): 243–258. doi:10.1080/15595692.2013.827115.

- Verlinghieri, E., and T. Schwanen. 2020. “Transport and Mobility Justice: Evolving Discussions.” Journal of Transport Geography 87: 102798. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102798.

- Viteri Gualinga, C. 2002. “Visión indígena del desarrollo en la Amazonía” Polis 3. Accessed 10 December 2020. http://journals.openedition.org/polis/7678

- Walsh, C. 2010. “Interculturalidad Crítica Y Educación Intercultural.” In Costruyendo Interculturalidad Critica, edited by J. Viana, L. Tapia, and C. Walsh, 75–96. La Paz: CAB.

- Whitten, N. E., D. S. Whitten, and A. Chango. 1997. “Return of the Yumbo: The Indigenous Caminata from Amazonia to Andean Quito.” American Ethnologist 24 (2): 355–391. doi:10.1525/ae.1997.24.2.355.

- Whyte, K., J. L. Talley, and J. D. Gibson. 2019. “Indigenous Mobility Traditions, Colonialism, and the Anthropocene.” Mobilities 14 (3): 319–335. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1611015.

- Zaragocin, S., and M. A. Caretta. 2021. “Cuerpo-territorio: A Decolonial Feminist Geographical Method for the Study of Embodiment.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (5): 1503–1518. doi:10.1080/24694452.2020.1812370.

- Zembylas, M. 2017. “The Quest for Cognitive Justice: Towards a Pluriversal Human Rights Education.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 15 (4): 397–409. doi:10.1080/14767724.2017.1357462.