Abstract

How do habits change? Some mobility scholars describe habits as regularly evolving. Several psychologists, on the other hand, observe radical changes originating from disruptions in our environment. I show that these two perspectives can be integrated using Berger and Luckmann’s model of individual change. In the first phase, a shock from the environment disrupt a habit or habits, which are later replaced by new habits progressively learned as part of a group. I applied this model to two French bike workshops active in cycling subculture. I used interviews and participant observation in the two workshops to examine how communities potentially lead their members to change their body habits (their way of moving, seeing, touching), their perception of the car and social mobility, and to adopt a radical definition of the “good life”. I found that the depth and breadth of habit change depended on the individual’s involvement in the bike workshop and of the type of shock he/she experienced. As a result, I show how an instance of the cycling subculture transforms habits, both progressively and radically, by strengthening the relationship between individuals and their bikes. The article opens the path to applications of Berger and Luckmann’s theory to mobility.

Introduction

Many psychologists, sociologists, and mobility scholars use the notion of ‘habit’ to counteract the model of the ever-calculating individual upheld by transportation economists (Kaufmann Citation2000; Shove Citation2012). Yet they differ in their appreciation of habit change. Psychological theories often describe habits as stable and rarely modified (Verplanken and Orbell Citation2003; Verplanken and Wood Citation2006; Neal, Wood, and Quinn Citation2006). For several mobility scholars, however, this view is reductive. For them, habits are continuous sources of minor changes. Firstly, they describe habits as evolving (Bissell Citation2012; see Shove Citation2012). Secondly, habits increase an individual’s ability to adopt a complex series of gestures (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012; Buhler Citation2020; Doody et al. Citation2021; see Shove Citation2012).

In this article, I cross-pollinate these two lines of thought. Studies on turning points confirm that radical habit changes often stem from a disruption in the environment (Rau and Manton Citation2016; Flamm, Jemelin, and Kaufmann Citation2008). Meanwhile, Schwanen, Banister, and Anable (Citation2012) recognize that habits have collective origins. I show that the work of Berger and Luckmann (Citation1991), who have been key to social constructivist approaches, can integrate these two opposing perspectives (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012, p. 527). Berger and Luckmann propose that individual change happens in two phases: when a disruptive event is followed by a collective and progressive acquisition of new habits (Citation1991). Moreover, many theories used in mobility studies are concerned foremost with daily habits. On the contrary, Berger and Luckmann’s model can explain minor and major transformations of the individual, daily life and long-term identity.

Unlike mobility scholars, however, Berger and Luckmann do not account for the role of mobility in individual changes. A focus on cycling subculture (Cox Citation2015) could remedy to this point. Within cycling subculture, I chose to inquire in two French bike workshops, also called bike ‘cooperatives’, ‘kitchens’ or ‘churches’ (Batterbury and Vandermeersch Citation2016; Bradley Citation2018; Rigal Citation2020). In France, bike workshops number more than 250, with a total of 110,000 members in 2020.Footnote1 They are spaces where tools, bike parts, and reconstructed bikes are stored. Ultimately, these communities focus on challenging the still pervasive ‘system of automobility’ (Urry Citation2004). Over the course of one month in 2019, I lived with bike activists and became acquainted with basic body techniques by repairing and riding my bike, and based on the ideology of the two workshops. In addition, I interviewed 40 members and ex-members of the two workshops. In this article I describe the unconventional culture that underpins the workshops, the specific initiation to bike mechanics, and how the potential consequences, i.e. the depth and breadth of individual change, is experienced by members.

I begin the article by cross-fertilizing the main results of psychologists and mobility scholars on the theory of habit, based on Berger and Luckmann's model on individual change (Citation1991). This theoretical frame was then applied to the bike workshops, i.e. instances of cycling subculture. The next section presents the two case studies and methods applied. The empirical section exposes the ways in which the bike workshops foster body techniques and habits of thinking. Based on a description of these teachings, I draw conclusions regarding the relationship between habit change and the specific communities of cycling subculture. I find that the depth and breadth of habit change depend on the individual’s involvement in the bike workshop, and the type of shock that he/she experienced. As a result, I show how an instance of cycling subculture change habits, both progressively and radically, by strengthening the relationship between individuals and their bikes.

Background

Communities of changing habits

As various psychologists have demonstrated, daily life is governed by repetition (Verplanken and Orbell Citation2003, p. 1313), and each repetition hardens habits (Quinn et al. Citation2010, p. 499). Most of the time, an individual with habits does not actively decide, for example, to drive. Psychologists often affirm that it is why a habit is difficult to change, particularly if the habit is repeated. These researchers identify the source of change as being linked to changes in the natural and/or built environment. If the habit is still being learned, the source of change resides in the individual's intentions (Verplanken and Orbell Citation2003; Verplanken and Wood Citation2006; Neal, Wood, and Quinn Citation2006).

Radical change resulting from a transformation in the natural, built, and social environment is sometimes called a turning point (Chatterjee and Scheiner Citation2015). Turning points occur due to planned or unplanned life events (Rau and Manton Citation2016), and are not isolated events. Like a chain reaction, a major life event, e.g. moving house, increases the probability of repercussive changes in other practices, e.g. the end of car use (Flamm, Jemelin, and Kaufmann Citation2008). But recent research shows that minor events can also impact travel habits (Doody et al. Citation2021, p. 3). It is during such periods of habit change – both the breaking and the acquiring of – that individuals are at their most reflexive and also under the influence of others (Verplanken and Wood Citation2006, p. 90, 97). As such, it is at these times that individuals decide to adopt new habits.

Several mobility scholars (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012; Bissell Citation2012; Buhler Citation2020; Doody et al. Citation2021; see Shove Citation2012) contradict psychologists' definition of habit. A habit is not an irreversible state that follows a phase of conscious adoption. Repetition does not only harden habits but also reinforces skills (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012, p. 525–526; Shove Citation2012), even if sometimes habits fail (Bissell Citation2012, p. 139). Moreover, few habits are formed through conscious decision alone (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012, p. 524). Mobility habits, for instance, are not only the result of a conscious process (Graham-Rowe et al. Citation2011) but requires the adoption of new body techniques (Mauss Citation1973; see Bissell Citation2012).

These critiques allow for a less reductive definition of habit. A habit is not only a repeated behavior (Shove Citation2012) but 'a disposition and fundamental way of being' (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012, p. 524; see also Buhler Citation2020). Habits are not only individual and basic routines but also the internalization of intellectual processes and world views, i.e., habits of thinking initiated by groups. This is precisely the connection Berger and Luckmann were able to draw in discussing the collective learning of habits (1991).

Berger and Luckmann did not discuss the aforementioned psychological theories. Still, the two social constructivists are at odds with them. They ascertain that 'all human activity is subject to habitualization' (Citation1991, p. 70), insisting on the processual acquisition of habits, in line with mobility scholars. For Berger and Luckmann, learning a new habit does not happen by repetition (contra Verplanken and Orbell Citation2003, p. 1313; Quinn et al. Citation2010, p. 499) but by following two distinct phases: first, a disruptive event occurs, i.e. a thesis that parallels the results about turning points; second, subsequent 'habitualizations' are learned in a community (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012). The role that Berger and Luckmann confer to groups also contradicts psychologists who view habits as individual processes.

In addition, Berger and Luckmann point out an alternative barrier to changing habits. A new 'habitualization' is adapted to 'something' and not 'nothing' (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991, p. 150). Interpreting a shock and becoming a member of a new community can be difficult because of old habits acquired during 'primary' and 'secondary' socialization (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991, p. 150). A near-total replacement of former habits necessitates 're-socialization' (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991, p. 181), including new affective bonds.

What do Berger and Luckmann brings to the study of habits that the approaches used by mobility scholars do not, including the theory of practice? Berger and Luckmann’s model has three advantages. First, they deal with minor and radical individual changes (re-socialization). On the contrary, mobility scholars are interested first in mobility habits.

Second, Berger and Luckmann attribute a role to communities. Most mobility scholars I quoted lack a deep analysis of groups. For example, Schwanen, Banister, and Anable mention only twice ‘community’ and three times ‘group' in a ten-page article (2012). Bissell (Citation2012), Buhler (Citation2020), and Doody et al. (Citation2021) do not mention collective entities in their respective analyses of habits. In the same vein, in her chapter on habits, Shove writes that 'habit-demanding practices' recruit their hosts (Shove Citation2012, p. 101). This metaphor hides the fact that groups (and not habits) recruit new members and that groups teach habits and norms.

Third, Berger and Luckmann analyze the compatibility between past, present, and new habits. Because the theory of practice and other theories about mobility habits barely consider radical change, they neglect the effects of new habits on individual identity. For example, Shove recognizes that new habits are ‘displacing or reconfiguring others’ (Shove Citation2012, p. 106). But the theory of practice does not deal with the issues caused by a radical re-socialization, notably the renewed definition of the self.

Meanwhile, contrary to mobility scholars and the proponents of the theory of practice, Berger and Luckmann do not account for body techniques, spaces, and mobilities. That is why, informed by works from mobility scholars, it is innovative to apply their theory to mobilities in general and bike workshops in particular.

The cycling subculture and French bike workshops

In their model of individual change, Berger and Luckmann deal with abstract groups and neglect mobility. To develop their model, an unconventional group (i.e. in which the meaning-making work is idiosyncratic) with a strong interest in objects linked to use of the body was an interesting choice. That is why I chose to study French bike workshops, which are manifestations of the cycling subculture.

A subculture is a set of 'beliefs, values, norms, and customs associated with a relatively distinct social subsystem (a set of interpersonal networks and institutions) existing within a larger social system and culture' (Fischer Citation1975, p. 1323). Subcultures are vectors of social change that are at odds with tradition and/or the majority. Cox characterizes the cycling subculture based on three traits (2015). A first trait common to daily cyclists and bike activists is that they are a 'distinct' minority in most Western cities, with well-known exceptions such as Amsterdam. A second trait is that cyclists have always gathered in 'interpersonal networks and institutions' (e.g., Friss Citation2019 ). This creates the conditions that make the forming of specific 'beliefs, values, norms' possible. A third point highlighted by Cox (Citation2015) is that cycling subculture stands in conflict with the 'larger social system and culture,' that is the 'automobility system’ (Urry Citation2004).

Bike workshops are connected to different communities within cycling subculture. To begin, the workshops participate in and sometimes organize critical mass rides (Furness Citation2007; Candipan Citation2019), and other experimental activities (for the cicLAvia, see Lugo Citation2013), which are arguably the most spectacular manifestations of this subculture (Bradley Citation2018, p. 1679).Footnote2 Secondly, on a daily basis, bike workshops allow individuals to do maintenance on their own bikes - a must for every bike rider. In an inquiry of 580 cyclists in France, 73% of members of bike workshops participated in at least one other bike associations (versus only 20% for non-members of bike workshops).Footnote3

French bike workshops are associations funded by member fees and are likewise occasionally financed by cities and public agencies. Half of the 250 French workshops belong to a national network called L’Heureux Cyclage. The aim of this network is to promote bike use – which was less than 5% daily for the French population in 2016Footnote4 – by teaching how to recycle, repair and reuse their bikes. This work is perceived as in opposition to mass consumption (Graham and Thrift Citation2007). The national network’ ideology centers on the norms for teaching how to become autonomous in terms of the bike, and beyond.Footnote5 The workshops’ pedagogy is explicitly practice-oriented, collaborative and anti-authoritarian.5 On the contrary, the workshops view the car, which was used daily by 54% of the French population in 2019Footnote6, as synonymous with an absence of autonomy, notably because repairing as car has become difficult and costly (Bradley Citation2018). In 2017, a third of members of French bike workshops did not own a car, versus 19% of French households (Meixner Citation2017, p. 12).

Bike workshops have been proven 'vectors of social change' at the local scale (Batterbury and Vandermeersch Citation2016, p. 191). To begin, 69% of the members of workshops that belonged to the national network declared having repaired their bikes by themselves, versus 47% of non-members.Footnote7 17% of French workshops members declared they had stopped using their car or had renounced the intention to buy one (Meixner Citation2017, p. 21). When workshop members experienced a bike breakdown, only 10% declared having used a car, versus 23% of frequent bike users.Footnote8 These results show that bike workshops create and reinforce the conditions necessary for cycling among their members, with a median age of 35 years and a median of 37% female members.Footnote9

Based on these first considerations relative to the relationship between individual change and bike workshops, our main hypothesis was that the depth and breadth of habit change depends on the degree of the individual’s involvement in the bike workshop. The first level of involvement is the discovery of minor repair techniques; the final stage is adopting the habits ways of thinking of an unconventional bike mechanic. Based on Berger and Luckmann’s model, the first stage is correlated to small shocks (e.g. a bike breakdown) and the latter to major life events.

Cases and methods

The study was based on 40 in situ interviews over a one month period in two French bike workshops during the summer of 2019, with workshop employees, ex-wage earners, volunteers, members, new members, and ex-members. Following my informants in their day-to-day activities led me to visit three other workshops, to participate in a critical mass, to collect bikes in public dumps, to eat with fellow participants and to be a guest in several participants' homes.

My participant observation was that I was learning to deal with minor repairs and upgrades to my bicycle. My stay in each workshop was short (one month), but intensive. The aim was to (1) experience the challenges that beginners encounter in learning new body techniques and (2) become a member of these two workshops. This short period of time parallels, and even extends beyond, the time it takes newcomer to learn to repair a bike after a breakdown.

Contrary to long-term participant observation that aims to embody complex body techniques, particularly in communities that are unknown to the researcher, my aim was to be in the shoes of a newcomer and not to become an experienced mechanic. Ideologically, the task was facilitated by the fact that I do not have a driving license and that I study alternatives to the car. On a day-to-day basis, my status of scholar also conferred me privileges, like working in the two workshops when they were not open to the public. Socially, my integration was fostered by my work: I needed to enter into contact with as many members as possible ().

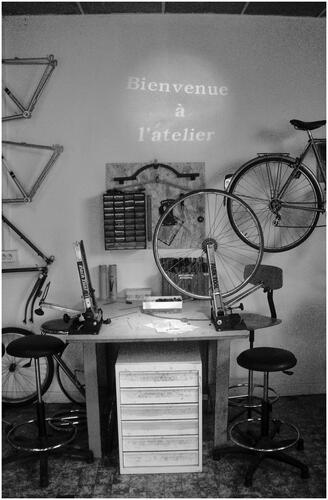

The first workshop was Small Bike in your Head (abbreviated here as Small Bike), which was founded in the city of Grenoble (451,096) in 1995. Small Bike is located in a lower middle-class, ethnically diverse neighborhood (e.g. there is a migrant squat located a few streets away from the workshop). It has around 1,000 members and is managed by volunteers and intermittent salaried employees. Small Bike is still rooted in radical experimentation. The second site was City by Bike (abbreviated as City Bike). City Bike is less revolutionary in its mission and modus operandi, and actively collaborates with public authorities. City Bike is two years old and has similar membership base. The workshop, which is located in a small city outside the Greater Geneva area (one million inhabitants) in a poorer, ethnically diverse area of the agglomeration, has one or two paid employees. There is a squat located on the top floor of the building, where the shop is located ().

The sites were not selected at random: the first workshop was based on a utopian model that influenced the development of French workshops; the second was designed as a progressive association. By studying the two bike workshops, I was able to identify commonalities in terms of the use of objects and the relationship to the body. Additionally, I observed differences that influence the variety of habits possible in each workshop (e.g. the frequency of shared meals).

These two communities recruit new members with any background and attempt to stave off the male domination (an aim mentioned in the national network’s 2018 annual report).Footnote10 Both workshops are accessible for an annual membership fee of 20€or less for migrants in need. One out of four French workshops also proposes a ‘bike school,’ which is particularly useful for individuals who do not know how to ride a bike (van der Kloof Citation2015). From a daily perspective, the two associations are predominantly frequented by a white, male population with traits close to mine (see Lubitow, Tompkins, and Feldman Citation2019). In general, one third of French bike workshop members are middle to upper middle class (Meixner Citation2017, 12), like French associations in general (INSEE Citation2010). The French workshops are populated by bohemians, who are often included in the creative class (see Hoffman and Lugo Citation2014). Members tend to be more educated but not necessarily richer on average than the French population at large due of the presence of unemployed persons and students. The contribution to gentrification of the two workshops is not as obvious as in the cases highlighted by Hoffman and Lugo (Citation2014) but nonetheless merit research in its own right.

Findings

Changing the perception of objects

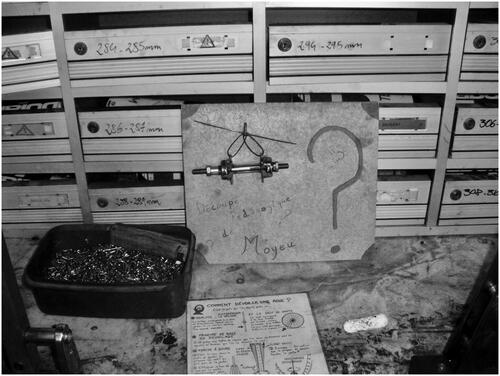

The first workshop I spent time in was Small Bike. When I arrived, I hardly knew which way to look. Five of the people I interviewed likened the workshop to Ali Baba's cave, another called it a 'bazar.' When TatianaFootnote11, a Russian engineer in her twenties, discovered the workshop, she was 'shocked.' During my first few days there, I spent long minutes studying posters showing different bike parts, from the frame to tiny bearings ().

At both sites, experienced members used educational modelsFootnote12 to teach how bikes are built and work. One example I saw in both workshops was that of the wheel hub. A 3D model was presented with a legend and shown to all members. I was able to play with the parts and learn how it works before fixing my own bike. This example illustrates the need to develop dexterity and visual skills on a micro-scale. Such skills are also required on a larger scale for handling objects (e.g. hanging my bike on a rack).

Yet, as a novice, making use of the tools and objects in the workshop was impossible initially. I am not alone in this sentiment. Although France ranks 4th in the world for bike ownership, the level of daily cycling is low due in part to poor quality and a lack of repair and maintenance (Atout France Citation2009). That is why the posters on the walls of the two workshops encourage people to ask for help and to help others. My bike problems – an over-stretched chain, a faulty brake, a defective freewheel – were handled collectively. My informants helped me to memorize the names of bike parts and tools. With their advice and through practice dismantling old bikes, I was able to take the first steps towards acquiring the basic skills necessary for rudimentary bike mechanics ().

On the contrary, as will become clear in the following examples, individuals already used to handling tools are better prepared for the workshop environment. Salomé was one of the few women highly involved in Small Bike. Her boyfriend, a volunteer there, encouraged her to join as well. Ever since childhood, Salomé had had a strong interested in understanding mechanisms; she explained, 'my parents told me ‘that […] you are our only child who has always been interested in making things, in how to rebuild a house, or a bicycle’.' For others, the knowledge of mechanical tools comes from their manual jobs. Paul told me that his degree in engineering helped him to 'understand' bike mechanics. Yet, only a small portion of the most actively involved members in the workshops had had training as engineers or mechanics (15 out of 40 interviewees), and not more than 7% were able to rebuild a bike in two hours in French workshops in general – an expert level according to the French network of bike workshopsFootnote13.

In the bike workshop, both a newcomer like me and experienced mechanics must physically manipulate bikes as well as take an interest in them. The French names of the workshops make this clear: ateliers d'autoréparation, i.e. 'self-repair workshops.' This requirement is not accepted by all of the individuals who frequent the workshops. The founder of the Small Bike declares that 'the guy who considers himself as a client […] we like less.' On average, 69% of workshop members - but only 43% of non-member regular bike users - declared having repaired their bikes themselvesFootnote14. Ideally, French bike workshops are communities created so that every cyclist can learn to perceive, at least temporarily, his/her bike as an object to repairFootnote15. For Gabriel, the bike even symbolizes 'zero waste.’

Bike workshops welcome new members following a bike breakdown, as shown by a study of 418 members in five workshops in Lyon (Ferrand Citation2016, p. 32). The breakdown disturbs the perception of the normal functioning of the bike. Even a minor disruption – such as a flat tire or a loose handlebar - challenges the habitual perception of the bike and daily travel practices. 17% of workshop non-members do not know how to repair a flat tire versus only 3% of membersFootnote16. My informants explained that, once the bike is repaired, the member stops frequenting the workshop before the next breakdown. Yet, a small portion of individuals carry on at the workshop in the optic of fixing up or tuning their bikes. These individuals not only learn to repair their bikes, but they are also more fully socialized.

Juan, a Latino activist, became involved in the community when his girlfriend's bike broke down with a cracked crank. At first, he 'wanted to buy her a new bike.' 'But she wanted it fixed.' So he 'stopped by the workshop' and learned how to repair her bike, even if he had never been interested in mechanics before. After only a few months as part of the community, he became a bike activist on the local, national, and international levels. As he said, 'these days, all of my civic activities center around the bike.' A change in his perception of the bike as a commodity to an object one can repair thanks to the opportunity afforded by the workshop was the catalyst for a series of subsequent major changes. He even adopted the cycling subculture’s ways of thinking, namely in terms of sustainable transport. This change was made possible by a contingent and minor crisis – a breakdown – and a specific community challenging the perception of objects – the bike workshop.

On dirt and membership

In the workshops, I handled bike parts covered with grease, oil, dust, and grime. As Antoine explained, 'many people would find [a workshop] a bit dirty.' ‘Dirt’ is an inside joke in the community, with bike workshops referring to the dirt that comes with the territory. One French workshop is called Crusty (Crade in French); another's official name is Dirty Nails in Mourning (Les Ongles en Deuil in French, referencing the black stains that develop from grease); the title of a workshop fanzine is Magic Dirty Grease (Magik Cambouik). The naming process is meaningful and suggests the centrality of this value. For Peter, an ex-engineer, it is even a moral stance: in Small Bike 'you free yourself, you aren’t there to stay clean’ ().

Workshops also employ a pedagogical tool to help novices adapt to the dirt. To instill the learning of new habits participation in a workshop requires, some experienced mechanics wear white gloves. Their aim is to keep their gloves immaculate; they help novices by explaining what they must do to fix their bike, but do not handle the bikes themselves. This is yet another technique for overcoming the ‘fear of getting dirty’, and to help new members perceive bikes as repairable objects. The trick of the white gloves is also political. As Richard Sennett said, a workshop is usually a place where authority is exerted and obedience may be required because of inequalities in skills (Sennett Citation2008, p. 54). Clean white gloves signify the superior skills of those workshop members. But the gloves also regulate the exercise of their authority, allowing beginners to learn. As Guillaume, founder of Small Bike, explains, for experienced mechanics, it is difficult to resist to the temptation to repair someone else’s bike. Personally, I observed that the idea of self-repair and actually doing it are often at odds, especially at City Bike, where there are two mechanics – a special status.

In spite of myself, I began to feel proud of having dirty hands, at least temporarily. It was a sign of my progressive integration into this subculture. Yet, one of my informants explained to me that, as an expert mechanic, his pride was in keeping clean hands. To pursue their socialization process, newcomers unaccustomed to handling tools and grease needs to re-learn how to wash their hands. Julien, a tall volunteer, joked with me about needing to wash one's hands eight times before cooking at Small Bike. In the first workshop I visited, I read a sign advising the use of oil and soap. In the second, coffee grounds are mixed with soap before rubbing and rinsing. In both cases, techniques for caring for the body (Mauss Citation1973, p. 84) are relearned.

The valuing (or at least the tolerance) of ‘dirty bikes’, i.e. bikes from public dumps usually thrown away as waste, is a decisive trait that distinguishes unconventional communities from dominant norms in terms of how objects are handled (e.g. the freegans: Barnard Citation2016). Bourdieu notably explained the negative connotation of dirt and its association with the lower classes (1984, p. 552). Meanwhile, the French sociologists identified counter-instances of dirt becoming a source of pride for specific groups, like for the bike workshops in this case study.

Conflict with the car

I don't need a war to fuel my bikeFootnote17

Being involved in bike workshop is linked to criticisms of the car. The struggle against the car is a unifying point of the collectives in which I participated. This conflict is spectacularly exemplified by critical masses. I participated in one such critical mass organized by Small Bike. Inside the workshops, cars are symbols of everything the most ardent mechanics reject. 'Long live the car!' was written on a blackboard in a workshop in Strasbourg, with 'You're stupid,' written right below it.Footnote18 When Régis wanted to put up a poster of a motorized vehicle in City Bike, the other members mocked him. The founder of City Bike openly declared that he dreamed of replacing cars with bikes. Members could get visibly agitated or angry when discussing the topic. One informant seethed during a long diatribe about the car – the cause of climate change – as the 'absurdity of the century'. As a recent daily cyclist, Benoît explains that he 'prefers being a forerunner than a sheep [in a car].' For Thérèse, unlike the car, the 'bike is a tool of freedom.’

The car/bike standoff is not only verbal; it can be a way of life, as revealed in the radical changes experienced by individuals who gave up their car for a bike. An automobile engineer like his sister, Paul had simply continued along the path his parents had taken until becoming painfully aware of the problem of traffic jams and the counter-productivity of his work.

We were producing cars for going out of work and being stuck in traffic jams. And you think 'but why?' […] I felt that the social environment of the factory was screwed up. And I knew that at some point, we needed to do otherwise, without having the answer. And the answer was the bike.

Paul, 40, bike activist, volunteer at Small Bike

These thoughts led Paul to leave the hierarchical bureaucratic environment of the car industry and backpack for months. Upon arriving in Nepal, he was enchanted by bicycle travelers and was eager to join them. Once back in France, he decided to start commuting by bike, then began training in bike mechanics, and was later hired at Small Bike. He stopped visiting his parents for several years, as the workshop and its members had become his home and family, a source of friendship and even romantic relationships. Paul’s re-socialization began with a 'revelation' on the ineffectiveness of the car, which led to his travels abroad, and ended with his becoming involved at Small Bike, rejecting his conservative family values and adopting the bike mechanics subculture.

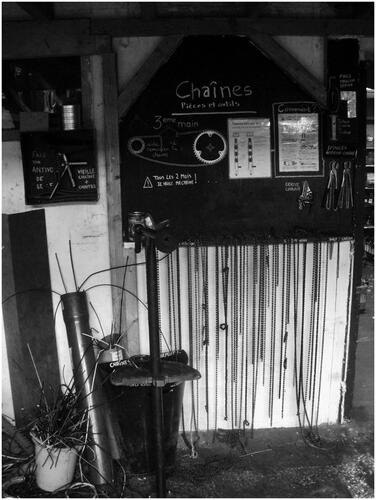

In French bike workshops, vélonomie is a neologism that summarizes the criticism of the car and the subculture’s general stance against authority and for individual autonomy.Footnote19 The term Vélonomie was born in bike workshops. The prefix - vélo - comes from the word meaning bicycle and the suffix from the word autonomie. The term conveys two meanings. The first is the use of the bicycle in association with the notion of autonomy, namely rebellion against hierarchies and the lack of ability to move by one's own means. Secondly, the prefix auto – as in autonomy – also evokes the auto in automobile, and thus is replaced by vélo, meaning bike, the car being identified as the enemy. This general philosophy is also expressed in the maxim 'Give a man a fish and he’ll eat for a day, teach him how to fish and he’ll eat forever.' This maxim is often featured on posters, blackboards in bike workshops, and on their websites. Thus I observed that bike workshops not only teach body techniques but also create and reinforce anti-car thinking habits.

Consuming less

We are left-wing, alternative, a bit dirty, with faces that are less pretty. We don't care about our clothes. We use slang. What I love here is the people who are not part of our circle…when I see that these people are uncomfortable, I enjoy it thoroughly.

Eric, 37, unemployed, member of Small Bike

As illustrated by the citation above, in bike workshops, promoting cycling ultimately consists of defending a standpoint with regard to social mobility. The latter is particularly clear in the trajectories of most active members, who experience downward social mobility, dirty hands and clothes being a sign of this process (Horton 1997 cited by Barnard Citation2016, p. 41). Moreover, seven of the 40 interviewees declared being voluntarily unemployed (with a middle or lower class background). Others had experienced a radical job change. For example, Isabelle, an energetic woman in her forties, left a career as an international businesswoman for casual jobs, art and bike activism.

Peter, an ex-engineer who started training at Small Bike, explains that he saw people in the community ‘living with very little’ and said to himself that ‘it was possible’. Joshua is one such person. A Dutchman living in France for years, Joshua left his previous job after his employer refused to promote him to a management position. Shortly thereafter, he traveled by bike across France for the first time to visit his daughter. This trip gave him the ‘bike travel bug’. Joshua’s atypical story was motivated by his ‘deep disagreement with how our society works today’. The result is a very independent way of life: he is 'always on a trip, far from a sedentary life.' Traveling by bike allows him to live a simple life at a pace he sets for himself. Joshua lives without a stable job, car, or even a home address. Though less radical than Joshua, several involved members of the workshops exchanged intellectual jobs for more manual ones. These individuals also moved from higher income categories (than those of their parents or themselves) to income categories below the national average. Paul, for instance, started his career as an automobile engineer until becoming a part-time bike mechanic at Small Bike, earning 700€per month. Downward mobility is not easy to come to terms with. Guillaume explains that, at first, his ‘family looked at him quizzically: from [a master's in] sociology to working on bikes, it was difficult to understand’. Even today, as he says, ‘I’m 50, I haven’t got a Rolex, and I ride a Raleigh [bike brand]. In a sense, [people can say] “your life isn’t a success”’.

Both founders of the bike shops expressed oppositional attitudes towards bourgeois values (e.g. Guillaume mentioned his bohemian delivery tricycle; Gérard criticized the Porsche Cayenne drivers). A graduate in sociology and a theater lover, Guillaume is the founder of Small Bike. The founder of the other workshop, Gérard of City Bike, is the son of a Swiss professor. In his youth, he was a community center worker and later the head of a carpentry company, before experiencing a 'burn out.' It was after this low point that he founded the bike workshop, in which he became a salaried employee. If Guillaume chose to leave sociology and ‘respectability’ (in the eyes of his family), Gérard seems to justify his status only in retrospect, more than having chosen a lower social status.

Less consumption can offer alternative 'consecrations' to those offered by schools, bureaucracies, and lifestyles defined by consumption (Bourdieu Citation1984, p. 96). The most active members of the bike workshops are identified with the bike subculture. The founder of the Small Bike told me that for years, people have been stopping him as he is riding his bike because they need repairs on their bikes. This identity confers some prestige in the microcosm of the workshops, in cycling subculture, and even beyond (e.g. like the two founders who have built relationships with public authorities in their respective cities).

Three types of socialization: discontinuous, continuous, and re-socialization

In this section, I generalize the findings detailed in the previous sections. I expose three degrees of involvement in the two bike workshops corresponding to three degrees of habit change.

Discontinuous socialization to bike mechanics

Luka, a Latvian man, rides his bike several times a week. He has been an irregular member of Small Bike for a decade. His membership depends on micro-crises, i.e. bike breakdowns.

Self-repairing one’s bike, I find that it comes naturally. Sooner or later a problem happens. I don’t go to a shop and pay. It is nicer to do it […] My idea of the bike is a transportation mode over which I have control. I’ve never had a new bike.

Luka, 29, student, member of Small Bike

Luka studied mechanics; he was not shocked by the dirt and had the skills necessary to use the tools at the Small Bike workshop. But Luka drives during his vacation, which he explains with embarrassment during the interview. Above all, he wants to become a school teacher and does not share the ideal of downward mobility. As a result, his identity is not deeply defined by the bike workshop.

Luka, like Tatiana, who experienced a shock during her first visit, is part of a group of 12 interviewees. They frequent the bike workshop when a breakdown occurs, with the intention of buying a bike, or through curiosity and luck. These workshop members learned to identify different types of breakdowns and tools, to put up with dirt, and to practice mechanics. But they have not necessarily adopted a philosophy that critiques the car and social mobility. Their socialization via the community of the workshop is 'partial' (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991, p. 181).

Yet these members went further than many others. They found enough time and desire to self-repair in a workshop. They were also able to speak French and to learn mechanics, which is difficult for recent migrants, as expressed by a student from Mexico and observed among several West Africans. But they are not part of the community in the strongest sense. Raphaëlle, a bike rider in her thirties, explains that she does not know the names of the employees and volunteers at City Bike. To summarize, I can say that these people stopped their socialization after experiencing a few micro-crises and new body work techniques.

Continuous socialization to bike mechanics

At City Bike, Robert is nicknamed 'Mr. Wheel'. He specializes in repairing and teaching how to repair wheels.

Researcher: How did you discover City Bike?

Robert, 73, retired, volunteer at City Bike: I didn’t discover the workshop. I was part of the association [before the creation of the workshop] and I love making things. I’d already spoken about it with the ex-president. I know bike mechanics and especially wheels. And the former president said 'it would be interesting to open a workshop.’ And one thing lead to another, and the workshop was created with the help of the mayor.

Robert declares himself a bike enthusiast. In the past, he worked in a bike shop. In his neighborhood he is known for helping to repair the bikes of family and friends and as the former president of the mountain bike club. Robert’s identity – and nickname – are deeply defined by the bike. In the workshop, he found a community where he was able to use his bike mechanic skills and conserve his identity, even after retirement. He frequents the workshop several times a week but he is not an anti-car or bike activist.

Like Robert and Régis, who wanted to hang a poster of a car in the City Bike workshop, nine interviewees are deeply involved in this cycling subculture. Their socialization was not as complete as those individuals who had adopted the more radical philosophies of bike workshop community (i.e. rejection of the car and the promotion of downward mobility). However, these individuals are deeply defined by cycling both inside and outside of the bike workshops. For most, this coincided with a renewed desire to practice bike mechanics (more so than teaching self-repair) following retirement, unemployment, or a breakdown. Many had previous exposure to mechanics and cycling. They interpret their present attraction to bike mechanics as a continuation of their previous habits, despite having experienced shocks. Re-socialization on the contrary demands a discontinuous reinterpretation of the past, e.g. a critique of past habits (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991, p. 182).

Re-socialization through bike mechanic

Since he was a child, Fabrice has defined ‘the good life’ as a life of hard work. He discovered the workshop thanks to a friend when he was working as an electrician, one of his many unsatisfactory and shocking job experiences. He felt that Small Bike was the community he had been looking for after years of research. He started getting involved in workshop life on weekends, and explained that it was a relief from his work week. Later, he found stability there as a bike mechanic for a couple of years, before the workshop lost an important funding source. Today, he declares that he is not looking for a job. Raised in a rural family with a grandfather who worked 16 hours a day, he experienced many deceptions as a worker. Then he discovered the bike workshop which, although it was not lucrative and demanded hard work, improved his quality of life, as he explains through a story exoticizing a Caribbean fisherman and using a radicalized trope:

This Caribbean fisherman says, 'I will work only in the morning, for my family'. But a banker comes and says 'if you work more, you can have a bigger boat, and then many boats, and more money'. The fisherman answers 'what for? In the afternoon, I take a nap, I watch my children playing… No. I have no need for what you’re talking about’.

Fabrice, 40, unemployed, ex-employee of Small Bike

Fabrice had many negative job experiences in connection with the car, the transportation mode he used to get to and from work. It was an unresolved conflict in his way of thinking. At Small Bike, he finally found a place with a very different philosophy and where he was still able to work manually. Workshop life was not only about work, but also about promoting the bike as a symbol of autonomy. His case highlights some of the difficulties inherent to the re-socialization process, as finding the right community and ‘ideal life’ can be difficult and/or a long-term process.

Like Fabrice, Paul, the automobile engineer who became a cycling mechanic, and Joshua, the bike traveler, 18 interviewees come close to achieving a re-socialization process. For these individuals, habit change was both broad and deep, either within a bike workshop itself or within the network of subculture places connected to the workshop. In addition to being trained to participate at the workshop, these individuals also criticized the car and rejected the goal of upward social mobility. Re-socialization often began with a negative work experience. I identify radical habit changes as those that broadly and profoundly impact bike workshops members’ lives.

Other individuals on the same potentially transformational path stopped before their re-socialization was complete. Mario, an unemployed Italian, explains that because he lives with his girlfriend, he cannot adopt a radical definition of ‘the good life’ and stop using the car and/or other products of mass consumption. Jonathan's inheritance of a strong religious identity from his parents created contradictions that can only be overcome by leaving the family circle and religious community. On the contrary, the case of Juan, who discovered the bike and became a regular member and representative of his workshop in just a few months, shows that the transition from the first degree of involvement and change to the third can happen rapidly if one does not have strong ties to a particular community before discovering the bike workshop.

In the bike workshops, the individuals who aspired and/or were close to a total re-socialization had a dominant position. For example, they had priority access to recently collected and/or special bikes. Above all, they were identified as ‘models’ within the workshops and were instrumental in shaping the identity of this community (e.g. praise of dirt and downward mobility, a leftist orientation, etc.) thanks to their cultural skills. On a local scale, tension existed between involved members who promoted a ‘subculture’ slant at the workshops, and those who simply wanted to promote the bike in a neutral way - in their minds - to a larger population. This latent conflict is translated, among other things, in the appearance of the workshops. The frontage of Small Bike is covered with slogans and signs promoting bikes, concerts, abortion, and criticizing cars and nuclear energy (). The frontage of City Bike, on the other hand, is store front with posters from the French government and information about the workshop (). This tension is also present in the French network of bike workshops. In 2019, I attended the workshops’ annual meeting in Strasbourg. During the day, conferences with officials and bike workshop members took place in the City Hall. At night, the members – without the officials – gathered at an underground venue with industrial esthetics. With the spread, growing popularity, and public recognition of French bike workshops, what is at stake for the highly involved (and transformed) members is safeguarding the dual definition of bike workshops as local bike utopias, and as tools for promoting the bike for everyone.Footnote20

Our main hypothesis was that the depth and breadth of habits’ change depend on the degree of the individual’s involvement in the bike workshop. This seems to be confirmed by the qualitative results exposed in this article. Learning new body work techniques require for several habit changes and demands further refinement, thus illustrating mobility scholars’ conception of habit (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012, p. 524; Buhler Citation2020). But one’s convictions can also curb one’s habit changes, for instance if one does not adhere to the ideology of the bike workshops. In such cases, the transformation superficial and limited, in part because it is not directly associated with a major biographical chock (e.g. leaving one’s job, undertaking a bike trip). On the contrary, adopting a new definition of ‘the good life’ – i.e. new habits of thinking – and a new identity (expressed notably in nicknames), deeply changes the individual and many of his/her habits. This re-socialization tends to occur after major biographical shocks. However, a new finding shows that it can also occur after minor shocks in daily habits, such as breakdowns.

In the three gradual types of habit change (discontinuous socialization, continuous socialization and re-socialization), the bike is central, even if objects were neglected by Berger and Luckmann in their model of individual change (1991). The bike is an instrument that one learns to deal with. It is also the symbol of a community (cycling subculture), of its autonomy-centered ideology (vélonomie), and of the identity of several individuals (e.g. for the founders of the bike workshops). The case of Fabrice, among others, highlights that the first 'shock' described by Berger and Luckmann can also be comprised of several crises (multiple negative work experiences), and that finding the right group for interpreting these crises can take years, and also require traveling (e.g. Paul and Joshua). By comparison with mobility scholars, I describe in depth the role of groups for fostering the redefinition of habits and even identity.

Conclusion

How do habits change? Applying Berger and Luckmann's model of individual change (1991) to two bike workshops in France, this study describes how individuals were drawn together to learn cycling and body work mechanics. Technical skills like being able to repair one's bike are necessary in order to participate in bike workshops. My investigation show that being a member increases the probability that new body work techniques will be acquired. The pedagogy of French bike workshops, which were developed with the goal of handling breakdowns and the many other quirks of bikes, notably leads to changes in the perception of objects as ‘usable’ and/or ‘dirty’. The gradual habitualization to waste, dirt, and tools closely corresponds to mobility scholars’ definition of habit (Schwanen, Banister, and Anable Citation2012; Bissell Citation2012; Buhler Citation2020; Doody et al. Citation2021; see Shove Citation2012) as a tendency reinforced by repetition but open to modification.

In certain cases, becoming involved in a bike workshop was a stepping stone for abandoning old habit and learning new ones. I identified three degrees/types of individual change: discontinuous socialization to bike mechanics; continuous socialization to bike mechanics; re-socialization through bike mechanics. The importance of an individual’s transformation is determined by the breadth of the acquisition of body work skills — discontinuous socialization to bike mechanics —, as well as the depth of influence of the bike workshop on the individual’s identity — continuous socialization to bike mechanics —. In the case of re-socialization through bike mechanics, bike workshops lead to radical individual changes that redefine one’s identity, especially following biographical shocks but also after bike travels and breakdowns. These radical changes are closer to those highlighted by psychologists and scholars who focus on turning points. Retirement, unemployment and changing jobs are important catalysts for getting involved in a bike workshop. It seems that the degree of involvement in the bike workshop and the degree of biographical shock are correlated. These re-socializations illustrate that, while the bike workshops specialize in bike mechanics, they are also subculture communities that foster wider changes.

Complementing Berger and Luckmann’s model, these results highlight the importance of the subculture for fostering habit changes. These results also opens the path to further research inspired by Berger and Luckmann’s theory on demotorization, sustainable mobility and low-carbon lifestyles and groups.

Acknowledgments

I would like thank Margot Abord-de-Chatillon, Anne Fuzier, Christophe Gay, David Joseph-Goteiner, Vincent Kaufmann, Marc Antoine Messer, and Emmanuel Ravalet for their insightful comments. The comments of the editor and two Mobilities reviewers greatly improved this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See https://www.heureux-cyclage.org/les-ateliers-dans-le-monde.html?lang=fr&afficher_regions=oui&afficher_gis=oui. (accessed 04/19/2021)

2 See the wiki for French bike workshops ‘critical mass’, often called vélorution in French (https://wiklou.org/wiki/V%C3%A9lorution.(accessed 08/29/2021).

3 These results are based on the ‘Enquête sur les pratiques et les attentes des cyclistes en mécanique vélo’ (2011) from the French network of bike workshops. It was compiled based on answers to an online questionnaire, posted on the websites of the national network, the workshops, and international partners, as well as face-to-face interviews, for a total of 571 cyclists interviewed in 107 bike workshops in France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada. The prerequisite for taking the survey was riding a bike at least once a month. 32% of the answers were given by members of a bike workshop, and 68% were given by non-members. Among the non-members, 20% were members of other bike associations. The results were reinforced by this sample. It shows that even bike riders are less skilled at repairing their bikes than members of bike workshops. Members of the workshops cycle more regularly, take better care of their bikes, tend to use second-hand bikes and use the car less in the event of a bike breakdown. For the details of the results, see enquete_no1_l_hc_-_pratiques_mecanique_velo_-_avril_2011.pdf and see also https://www.heureux-cyclage.org/local/cache-vignettes/L500xH193/enquete1-cb853.png?1568920512. (accessed 08/27/2021)

4 See ‘Enquête sur les pratiques environnementales des ménages’: ree.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/themes/enjeux-de-societe/les-francais-et-l-environnement/pratiques-environnementales-des-francais/article/les-francais-et-le-velo (accessed 08/27/2021)

5 On the website of the French network, one can read that: 'Workshops are places of learning to enable everyone to become autonomous […]. This self-actualization through mechanics is cooperative and based on solidarity: everyone is invited to teach others how to maintain and repair one’s bike.' (https://www.heureux-cyclage.org/presentation.html, 11/28/2019)

6 http://fr.statista.com/themes/2830/les-conducteurs-en-france-/#topicHeader_wrapper. (accessed 08/29/2021)

7 See endnote 3

8 Ibidem

9 Ibidem

10 Annual report 2018 of the national network (rapport_d_activites_2018_lhc.pdf, accessed 08/29/2021). Moreover, in 2015, Small Bike mandated an association specialized in dealing with male domination to inquire about the shop. Like in other workshop environments (e.g. the surfing industry, Warren Citation2016), homosociality led to the sexualization of women. However, this culture has changed. During my stay in the two workshops I heard no jokes about or remarks on women’s bodies.

11 The names of the individuals are pseudonyms, as I explained to the shop members before the interviews. The interviewees were informed of the aim of my research project – describing individual habit change in bike workshops – and of the subsequent publications of my results. Most were eager to speak about their practices, in order to promote the bike shops. More generally, my research in the two workshops was announced and discussed during a formal meeting at City Bike, and an informal meeting at Small Bike (where I presented the first results of my research a few months after my inquiry). I also asked members for the right to take pictures of the workshops, but avoided photographing individuals.

12 For a complete overview of the pedagogical objects used by the bike workshops in France, see: https://wiklou.org/wiki/Catégorie:Pédagogie (11/28/2019)

13 See endnote 3

14 Ibidem

15 The name of the French network of the bike workshops is revelatory (L'Heureux Cyclage). This name is a play on words meaning means both happy cycling and recycling.

16 See endnote 3

17 A slogan identified on a picture taken during the critical mass organized by Extinction Rebellion, in Grenoble (https://a480.org., accessed 01/17/2021)

18 Discussion written in a bike workshop called Bretz'selle, Strasbourg (https://www.bretzselle.org, accessed: 01/17/21).

19 e.g. http://wiki.cyclocoop.org/Vélonomie/. (accessed 05/16/2019)

20 Tension explicitly expressed in an exchange of emails I participated in with a representative of the French network of bike workshops.

References

- Atout France. 2009. Etude complète - Spécial Économie du Vélo. Paris: Atout France.

- Barnard, Alex V. 2016. Freegans: Diving into the Wealth of Food Waste in America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Batterbury, Simon, and Inès Vandermeersch. 2016. “14 Community Bicycle Workshops and 'Invisible Cyclists,” In Bicycle Justice and Urban Transformation: Biking for All?, edited by A. Golub, M. L. Hoffmann, A. E. Lugo and G. F. Sandoval, 189–202. London: Routledge.

- Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. 1991. The Social Construction of Reality, a Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Penguin Books.

- Bissell, David. 2012. “Agitating the Powers of Habit: Towards a Volatile Politics of Thought.” Theory & Event 15 (1) doi:10.1353/tae.2012.0000.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction, A Social Critique of Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bradley, Karin. 2018. “Bike Kitchens–Spaces for Convivial Tools.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1676–1683. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.208.

- Buhler, Thomas. 2020. “Habits as a Better Way to Understand Urban Mobilities.” In Handbook of Urban Mobilities, edited by O. B. Jensen, C. Lassen, V. Kaufmann, M. Freudendal-Pedersen and I. S. Gøtzsche Lange, 214–223. London: Routledge.

- Candipan, Jennifer. 2019. “Change Agents’ on Two Wheels: Claiming Community and Contesting Spatial Inequalities through Cycling in Los Angeles.” City & Community 18 (3): 965–982. doi:10.1111/cico.12430.

- Chatterjee, Kiron, and Joachim Scheiner. 2015. “Understanding Changing Travel Behaviour Over the Life Course: Contributions from Biographical Research.” 14th International Conference on Travel Behaviour Research, Windsor.

- Cox, Peter. 2015. “Cycling Cultures and Social Theory.” In Cycling Cultures, edited by P. Cox, 14–42. Chester: University of Chester Press.

- Doody, Brendan J., Tim Schwanen, Derk A. Loorbach, Sem Oxenaar, Peter Arnfalk, Elisabeth M. C. Svennevik, Tom Erik Julsrud, et al. 2021. “Entering, Enduring and Exiting: The Durability of Shared Mobility Arrangements and Habits.” Mobilities : 1–17. doi:10.1080/17450101.2021.1958365.

- Ferrand, Bruno. 2016. Les Ateliers D’autoréparation de Lyon. Lyon: Mémoire VetAgroSup.

- Fischer, Claude S. 1975. “Toward a Subcultural Theory of Urbanism.” American Journal of Sociology 80 (6): 1319–1341. doi:10.1086/225993.

- Flamm, Michael, Christophe Jemelin, and Vincent Kaufmann. 2008. “ Travel Behaviour Adaptation Processes During Life Course Transitions.” Lasur Report 16. https://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/128461?ln=fr

- Friss, Evan. 2019. On Bicycles: A 200-Year History of Cycling in New York City. New York City: Columbia University Press.

- Furness, Zack. 2007. “Critical Mass, Urban Space and Velomobility.” Mobilities 2 (2): 299–319. doi:10.1080/17450100701381607.

- Graham, Stephen, and Nigel Thrift. 2007. “Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Theory Culture & Society 24 (3): 1–25. doi:10.1177/0263276407075954.

- Graham-Rowe, Ella, Stephen Skippon, Benjamin Gardner, and Charles Abraham. 2011. “Can we Reduce and, If so, How? A Review of Available Evidence.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 45 (5): 401–418. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2011.02.001.

- Hoffman, Melody L., and Adonia Lugo. 2014. “Who is ‘World Class’? Transportation Justice and Bicycle Policy.” Urbanities 4 (1): 45–61.

- INSEE. 2010. Vie Associative: 16 Millions D’adhérents en 2008. Paris: INSEE.

- Kaufmann, Vincent. 2000. Mobilité Quotidienne et Dynamiques Urbaines. Lausanne: Presses Polytechniques Romandes.

- Lubitow, Amy, Kyla Tompkins, and Madeleine Feldman. 2019. “Sustainable Cycling for All? Race and Gender–Based Bicycling Inequalities in Portland, Oregon.” City & Community 18 (4): 1181–1202. doi:10.1111/cico.12470.

- Lugo, Adonia. 2013. “CicLAvia and Human Infrastructure in Los Angeles: ethnographic Experiments in Equitable Bike Planning.” Journal of Transport Geography 30: 202–207. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.04.010.

- Mauss, Marcel. 1973. “Techniques of the Body.” Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88. doi:10.1080/03085147300000003.

- Meixner, Evan. 2017. Etude D’évaluation Sur Les Services Vélos. Enquête Sur Les Ateliers D’autoréparation de Vélos. Angers: ADEME.

- Neal, David T., Wendy Wood, and Jeffrey M. Quinn. 2006. “Habits: A Repeat Performance.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 15 (4): 198–202. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00435.x.

- Quinn, Jeffrey, Anthony Pascoe, Wendy Wood, and David T. Neal. 2010. “Can’t Control Yourself? Monitor Those Bad Habits.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36 (4): 499–511. doi:10.1177/0146167209360665.

- Rau, Henrike, and Richard Manton. 2016. “Life Events and Mobility Milestones: Advances in Mobility Biography Theory and Research.” Journal of Transport Geography 52: 51–60. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.02.010.

- Rigal, Alexandre. 2020. Changer la vie dans un atelier d’autoréparation de vélo. Mobile Lives Forum. https://forumviesmobiles.org/sites/default/files/editor/rigal_alexandre_changer_la_vie_dans_un_atelier_dautoreparation_de_velo.pdf.

- Schwanen, Tim, David Banister, and Jillian Anable. 2012. “Rethinking Habits and Their Role in Behaviour Change: The Case of Low-Carbon Mobility.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 522–532. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.06.003.

- Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven, CO: Yale University Press.

- Shove, Elizabeth. 2012. “Habits and Their Creatures.” In The Habits of Consumption, edited by A. Warde, and D. Southerton, 100–113. Helsinki: Collegium.

- Urry, John. 2004. “The ''System'' of Automobility.” Theory Culture & Society 21 (4–5): 25–39. doi:10.1177/0263276404046059.

- van der Kloof, Angela. 2015. “Lessons Learned through Training Immigrant Women in The Netherlands to Cycle.” In Cycling Cultures, edited by P. Cox, 78–105. Chester: University of Chester.

- Verplanken, Bas, and Sheina Orbell. 2003. “Reflections on Past Behavior: A Self-Report of Habit Strenght.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 33 (6): 1313–1330. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01951.x.

- Verplanken, Bas, and Wendy Wood. 2006. “Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 25 (1): 90–103. doi:10.1509/jppm.25.1.90.

- Warren, Andrew T. 2016. “Crafting Masculinities: gender, Culture and Emotion at Work in the Surfboard Industry.” Gender, Place and Culture 23 (1): 36–54. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2014.991702.