Abstract

The article engages with the relationship between the chronopolitics of mobility and migrants’ narratives of the past, their present suffering, and hope for the future. Data collected through observation and repeat interviews with migrants in the Moria and Kara Tepe camps in Lesvos, Greece, challenge the assumption that ‘time’ spent waiting in the camps by illegalized migrants represents a linear and singular metanarrative of the migrant in ‘temporal suspension’ from the ‘grid of modernity’. I suggest, that the concept of historical time allows for a critical analysis of illegalized migrants’ narratives of their past lives, their present suffering and future aspirations, through which they challenge the chronopolitics of control inherent in the current EU migration system. While such narratives might at first sight be understood as accepting a migration system based on suspension and gradual re-introduction into western historical and political time, they present a challenge to the exceptionality of western modernity and their suspension from it. I also argue, that narratives of ‘pasts’, ‘the present’ and hope for the ‘future’, challenge academic discourses of migration that centre on the notion of ‘bare life’, where historical and political time is suspended in the liminal space of the camp.

Introduction

Within migration scholarship, migration trajectories have mainly been explored from the perspective of space and the spatial considerations of migration routes and settlement. Human mobility and its immobilization at the border, in detention centres or in reception camps, have informed both the securitization of migration perspective (Ticktin Citation2005; Huysmans Citation2006; Salter Citation2006; Tsianos and Karakayali Citation2010; van Houtum Citation2010; De Genova Citation2013; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2015) and the ‘autonomous migration perspective’ (Mezzadra Citation2004; Isin and Neilsen Citation2008; Walters Citation2008; Mitropoulos and Neilson Citation2006; De Genova Citation2017; El-Shaarawi and Razsa Citation2019). In such accounts, spatial arrangements have been analysed either as a fundamental mechanism in sustaining migration regimes that illegalise and restrict movement, or have been understood as temporarily disrupting the force of human mobility as the latter contests and in turn disrupts migration regimes that attempt to monitor, channel and transform human mobility into a passive and governed flow.

It is only recently that time and temporality, have been considered as an important element in understanding uprootedness and precarity in migrant experience (Biehl Citation2015; Turnbull Citation2016). Increasingly, temporal connections and experiences of a number of migration related phenomena such as transience, suspension, waiting (Hage Citation2009, Citation2018; Jacobsen and Karlsen Citation2021; Khosravi Citation2014) have been explored as important categories of analysis of the politics of migration control (Mountz Citation2011; Andersson Citation2014; Tazzioli Citation2018; De Genova Citation2021). Such renewed interest in exploring migration through the perspective of time, has indeed enriched migration literature and has provided a different understanding of processes of being, becoming and belonging for migrants (Griffiths Citation2014).

In this article, I will engage with the relationship between the chronopolitics of mobility/immobility and migrant narratives of pasts left behind, present suffering and hope for the future. The aim is not to reject the importance of space and spatiality in understanding the complex experiences of migrant movement, but to provide an additional and equally important focus on the relationship between time and migrant understandings of being.Footnote1 I will be drawing on narratives of illegalized migrantsFootnote2 immobilized in space in situations of encampment, waiting for decisions on the legality or illegality of their claims for asylum. I argue, that the data analysed invite us to rethink our perception of ‘time’ as a linear description of events, or as a singular metanarrative experienced by illegalized migrants as ‘temporal suspension’ from, and reintroduction to the ‘grid of modernity’ (Ferguson Citation1999, Citation2002). A better way to understand time in situations of encampment is through the concept of ‘historical time’ (Koselleck Citation2004). For Koselleck (Citation2004), the dominance of a narrative of time defined by acceleration and endless progress, has shaped the present and the future, not just of the West, but of those that are seen as the West’s ‘Others’. This linear temporality has also defined the politics of control at the borders of Europe where migrants are immobilized in space and time, while their claims for asylum are checked, for either ‘normalising’ their status and therefore ‘allowed’ to the tempo of western time or deported. I argue, that through developing narratives of their past lives and their hopes towards the future, illegalized migrants attempt to challenge the chronopolitics of control imposed upon them from within the current EU migration system. While such narratives might at first, be understood as having internalised the priorities of a migration system that conditions their gradual ‘re-introduction’ to western modernity and eventual normalisation of their status on state policies (Arendt [Citation1951]Citation2017; van Houtum Citation2010; Ticktin Citation2005; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2015), they however, challenge the exceptionality of western modernity and their suspension from/in it. I also argue, that narratives of ‘pasts’, ‘present suffering’ and hope for the ‘future’, and the different temporalities they allude to, challenge the uchronic state of migrant existence embedded in academic discourses of migration that centre on the notion of ‘bare life’ (Agamben Citation1998; Sylvester Citation2006; van Houtum Citation2010; Minca Citation2015), where historical and political time ceases to pass after having entered the liminal space of the camp.

The field

This paper is part of a broader project focusing on illegalized migrants and perceptions of rights. In particular, the project questioned the criteria of ‘deservedness’ as applied by the EU’s migration management system, and as understood by migrants themselves. It explored conflicting accounts of rights and engaged with questions of agency and meaning production, in a system of migration management that enforces ‘graduated zones of sovereignty’ (Ong Citation2006), around the principle of the eventual normalisation of the status of those seen as worthy.

The data analysed in this article are collected through observation and repeat interviews with 50 asylum seekers in the Moria and Kara Tepe camps in the island of Lesvos, Greece. The Moria camp, is one of the ‘hot spots’ in the Eastern Mediterranean migration route. It is highly securitized and run by the Greek Border Police and FRONTEX, the EU’s body for migration control. It is a registration camp, where all migrants arriving in the island are taken to undergo the lengthy process of registration which involves deploying the EU’s digital firewall (fingerprinting, iris scans, blood and DNA samples, examining people’s papers and stories, interviews to determine the ‘validity’ of these and issuing ‘case’ paperwork on each migrant). It is after this process, that some migrants, especially families, unaccompanied and vulnerable people, are moved to the Kara Tepe camp, just 30 min away from Moria. Although Kara Tepe is run by the municipality of Mytilene and is less securitized, it is worth noting, that at the time of the research, it had closed to visitors. Visitors had to obtain permission to enter the camp both by the relevant municipality officials and the director of the camp. The analysis will focus on material collected over a period of twelve weeks in the summers of 2016 and 2017. The researcher spent most days in the two camps, conducting what can be broadly termed participant observation, combined with long and repeated informal discussions with camp residents and more formal interviews with guards, the director of the Kara Tepe camp and municipality officials, in order to obtain a more holistic understanding of the operation of, and situation in the camps. The informal discussions, which this paper draws on for the most part, involved meeting and getting to know camp residents, opening and sustaining conversations that continued throughout the duration of the fieldwork. Repeat conversations, walks, tea drinking, translating from Greek to English, reading and discussing administrative decisions (written in Greek, without any translation to other languages) and visits to the city of Mytilene, were part of the research and were intended to provide the researcher with a better sense of life in the camps, reflections on my interlocutors’ journey and their aspirations for the future. The frequency of the conversations with each of my participants varied, between four with some, to almost daily chats with others. Distinctions between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ migrants, ‘refugees’ and ‘economic’ migrants were avoided in selecting my interlocutors. Instead attention was placed on developing trust and allowing them to develop their own stories. In contrast to 2015, when crossing the EU borders could best be characterized by acceleration of movement (Rozakou Citation2021), the years that the data were collected, were years of deceleration or even suspension of mobility across the borders of the EU, the outcome of the reshaping of the EU’s migration system after the EU – Turkey Statement signed in March 2016. By the summer of 2016, both camps were overpopulated, with Moria holding triple the intended capacity of the camp, while Kara Tepe held twice its intended capacity. Power cuts were frequent in both camps, the facilities were basic with constant problems in the camps’ infrastructure. Although people fleeing countries that were included in the UNHCR list of legitimate asylum seeking were prioritised in terms of access to facilities, I talked to Syrians who were sleeping under impromptu tents constructed from blankets they were given, in an effort to protect themselves from the intense June and July sun and the high summer temperatures. This was more so in the case of Moria, as the capacity of the camp was at stretching point and as people could not move on to the next stage of their journey. Delays in organising the sorting interviews, the closure of the borders that would allow migrants to continue their journey (the outcome of the indecision or refusal on the part of some EU member countries to comply with the agreed EU quota system), and a number of court cases won by Greek human rights lawyers against the agreed externalisation of the EU borders as defined in the Turkey/European Union agreement (Migroeurop Citation2016)Footnote3 had substantially reduced movement.

In conversations, people described uncomfortable sleeping arrangements in both camps, ‘sleeping like sardines in a can’, lack of privacy, the noise from crying, overheated children, and the rising temperatures in restricted spaces, that kept them awake throughout the long summer nights.Footnote4

Daniel, an Ethiopian, who had been allocated in the Moria section housing those under repatriation orders, but had applied for asylum status, described conditions in Moria as far from ideal and reflected on the impact of the combination of the overcrowding, the inadequate facilities over long periods without a concrete prospect of a change. Specifically, he said:

We live in small tents with the sun burning us throughout the day. It is hot, hot, hot. We cannot stand, we cannot sleep, we cannot breathe. If I put you under the sun for five minutes you will get crazy, your mind will go. Imagine having to live like this for three months, four months, who knows for how long. Your mind slowly goes, you get angry, you get desperate, you get frustrated. This is how it is.

And Sesuna, an Eritrean woman, also in Moria, who was placed with her family in a cabin, echoed Daniel’s account,

it is too hot in there. We sleep in plastic UN cabins, all together in a cabin. We are given blankets to put down on the floor but not mattresses… We still are in a better place than others that are given just a small tent to sleep in. But we are crowded, nine people in a small plastic cabin and we can just lie down when we sleep. There is no space for anything else. (Moria camp).

The overcrowded camps, the lack of facilities that could make even bare living more bearable, the waiting, as well as the way this waiting was managed by the authorities and experienced by the residents of the two – not fit for purpose – camps, and the feelings of desperation and frustration generated, informed the ways in which illegalized migrants, processed and reacted to their situation.

Chronopolitics as an analytical lens in migration studies

Several studies on mobility within the current border regimes, have focused on the power of the border to halt or regulate the mobility of specific groups of people (asylum seekers or the ‘illegal’ migrants) through a number of mechanisms ranging from controlling queues, halting movement altogether in detention centres and fenced camps and unleashing a complex bureaucracy of registration, detention and removal technologies that aim to regulate movement in space and time. In such literature, ‘waiting’, ‘deceleration’, ‘suspension’, are central themes, understood to be pivotal elements of the technologies of control produced within the current systems of migration management (Mountz Citation2011; Andersson Citation2014; Cabot Citation2014; Griffiths Citation2014; Khosravi Citation2014, Citation2021; Biehl Citation2015; Tazzioli Citation2018; Turnbull Citation2016; Bendixsen and Eriksen Citation2018; McNevin and Missbach Citation2018).

Although such an approach to time and migration, generated from within a securitizing approach to migration, allows for an in depth understanding of how power operates at the border, it also produces an understanding of time as linear, and linked to representations of specific mobile subjects as experiencing temporal insecurities, waiting or even stuck in camps, where time ‘stands still’, is suspended or is experienced as ‘unproductive’ (Malkki Citation1995, Citation1996; Sylvester Citation2006; Andersson Citation2014; Tazzioli Citation2018). Rozakou (Citation2021), in her analysis of accelerated mobility and the new temporalities experienced by police officers, NGO workers and border crossers during the 2015 summer of migration in Greece, uses Paul Virilio’s (Citation1986) critique of the political economy of speed associated with modernity, to explore the severe effects of accelerated time on border crossers and the continuing cruelty of a border regime that although was reconfigured at the time, still exerted violence over those migrants that were illegalized.

In such accounts, time, understood as speed and acceleration, is associated with modernity (Koselleck Citation2004; Bauman Citation2000; Eriksen Citation2001) and capitalism (Ngai Citation2005; Tomlinson Citation2007; Miyazaki Citation2010) while slowing down, stasis and suspension are associated with the inability to inhabit western modernity that structures the sense of tempo around speed and productivity as defined within a capitalist logic. As Koselleck states,

Our modern concept of history has initially proved itself for the specifically historical determinants of progress and regress, acceleration and delay. Through the concept “history in and for itself,” the modern space of experience has in several respects been disclosed in its modernity. (2004, 103)

Ferguson (Citation1999, Citation2002) in his study of the Zambian copperbelt, describes stasis and frozenness juxtaposed by the residents of the copperbelt to progress and productivity. Feelings of temporal stagnation and abjection through neoliberal reform and environmental degradation, were experienced as historical elimination from the metanarrative of a productive life. It is through the binary of time as productive and time experienced as existential stasis, that the linear and singular metanarrative of time in western modernity as linked to acceleration, technological emancipation and progress (Koselleck Citation2004) is sustained. Binary constructions of some movements as desired and of others as undesired or even dangerous (Ngai Citation2005) and their link to how time is experienced by those subjects that are immobilized, have been attributed to the hegemonization of a particular understanding of historical time that eliminates narratives contrary to technological speed and capitalist accumulation. Bakewell (Citation2008) and Anderson (Citation2013) argue that such binaries between the mobile and those that ought to be immobilized, and the artificiality of the border as it is exercised differently for different groups, were produced during the colonial era and were mobilised by state institutions to argue that the movements of poor and disadvantaged groups ought to be controlled and allowed only for the economic benefit of those same institutions. Today, the same binaries are drawn between the mobile and the immobile, as it is still the case, that the mobility of the underprivileged or illegalized ‘Others’ is either considered to present an existential threat to the economic and cultural reproduction of western nations, or it is monitored and regulated for the benefit of global capitalism (Bauman Citation1998; Balibar Citation2004; de Haas Citation2008; Oliveri Citation2016). It is also the case, that immobilization on borderlands, part of technologies of control, is understood to be experienced by those subjected to it, as time ‘outside modernity’, as nothing happening, as deceleration, uneventfulness and dejection (Malkki Citation1995; Coutin Citation2003; Appadurai Citation2013). In such perspectives, the politics of time as structured within the current system of migration management and control, strips the illegalized migrant from rights and turns her into ‘bare life’ (Agamben Citation1998; Minca Citation2015; Sylvester Citation2006; van Houtum Citation2010) as after having entered the liminal space of the camp, historical and political time ceases to flow. It also involves the setting of precedents (Aradau Citation2004; Mountz Citation2011; Appadurai Citation2013; Yaris and Castaneda Citation2015) that have to be met for the gradual reintroduction of the liminal subject to an aspired future.

Time as multiple and relational

The chronopolitics of migration as discussed above, has indeed exposed the cruelty of a migration system that works through suspension in time and space and ‘re-incorporation’ into the social, political and economic priorities of western nations. However, from within anthropological and historical perspectives (Fabian Citation1983; Malkki Citation1995; Koselleck Citation2004; Hutchins Citation2008; Herzfeld Citation2009) a critique of accounts of time that hegemonize the temporal structures of western modernity and capitalism, have attempted to draw attention to the unquestioned acceptance and internalisation of the very structuring of time within western modernity. Herzfeld, commenting on anthropological accounts of ‘allochronism’ – time experienced as deceleration and even stasis by peoples considered as outside western modernity – positions such knowledge production as ‘embedded in the anthropologist’s own cultural specificity that assumes that non-Western peoples inhabit a time historically distinct from the (predominantly Western) anthropologists’ own experience of time as linear and linked to western modernity’ (Citation2009, 109; see also Fabian Citation1983). Moreover, he insists, time is experienced in different ways by different peoples living in different contexts, and temporalities are neither linear nor experienced uniformly. They are produced within specific contexts, through contestation and mediation between different actors. Time is both affective and shaped within social structures. Countering a linear understanding of time as hegemonizing a specific geopolitical imagination linked to capitalist modernity, is also proposed by Hutchings (Citation2008). She suggests the use of the concept of ‘heterotemporality’, as it refutes the idea that there is a single metanarrative of time determining contemporary temporal experience, and instead she espouses a ‘mutual contamination of ‘nows’ that participate in a variety of temporal trajectories’ (Hutchings Citation2008, 166). For Hutchins, to understand time as predetermined within the priorities of capitalist modernity, is to reject and devalue understandings of time outside it. It is also to link speed and technological acceleration to an everlasting progressivism while deceleration and slowing down is understood as suspension and regression from capitalist modernity. A similar conclusion is reached by Malkki, in her work on Hutu refugees in Tanzania (Citation1995) when exploring how refugees inside and outside the camp construct multiple and differing notions of Hutu time. Inside the camp, Hutus drew on ideas of a timeless, reified Hutu Nation to manage other determination. This she understands (Citation1995, 13), as a response to both the structures of a regime of control that imposed specific daily rhythms upon them, and the priorities of western humanitarian organisations -working in the camp- that dealt with refugees within a universal and abstract discourse of ‘suffering’ and ‘victimhood’. However, Hutus that lived outside the camp, ‘adapt to and adopt the temporal rhythms of their host nation, assimilating new cultural and economic systems’ (Citation1995, 14). It is the comparison of the differing interpretations of historical time constructed inside and outside the camp, that allows for an understanding of time as multiple and existing ‘in between’ and beyond hegemonic temporal structures (Citation1995).

Historical time is also at the centre of Koselleck’s (Citation2004) criticism of the politicization and singularization of time in historical accounts of the past and visions of the future. His examination of the rise of a modern temporality linked to the Enlightenment, the establishment of the capitalist logic and technological acceleration, allows for a critique of time as linked to a future-oriented progressivism that has become hegemonic and has been transformed into a ‘historical process’ (Koselleck Citation2004, 35). The major contribution of Koselleck, is to reject the singularization of history and to suggest an understanding of historical time as plural. He insists that there is not one history but many. There is not one present and future but many. For Koselleck (Citation2004), chronology and lived time coincide and also diverge. It is therefore possible to break away from a predetermined and singularized understanding of the past and therefore a singular future, and to consider persons with respect to their past experiences, possibilities and prospects. He therefore, understands history as multi-layered as the past is structured from different perspectives. The multi-layeredness of history, not only structures the past from different perspectives, but also the present and future in synchronic points of time. Knowledge production that singularizes the experience of time by illegalized migrants as primarily defined through suspension, therefore, risks reinforcing a logic of ‘Otherness’ by reproducing narratives of illegalized migrants as occupying a different temporality due to their migration status (Çag˘lar Citation2016; Ramsey Citation2020; Jacobsen and Karlsen Citation2021; Rozakou Citation2021). It also exemplifies a logic that denies migrants their pasts while freezing them to a present defined exclusively by lives lived in ‘crisis’ (Ramsay Citation2020), waiting to be incorporated into the normative time structure associated with global capitalism. As Jacobsen and Karlsen state, such knowledge production ‘rests on the idea of a passage, thus problematically implying a temporal linearity where the subject is, or should be, reincorporated into a particular normative social structure’ (Jacobsen and Karlsen Citation2021, 5). Such critiques have questioned the hegemonizing of a specific geopolitical imagination linked to capitalist modernity, while not losing sight of the relationship between time and power as exercised within the camps.

In the remainder of the article, I will explore the experiences of time from the perspective of my participants. Temporalities around queues, accessing facilities and public services, as well as waiting for decisions on the legality or illegality of claims and their link to uncertainty, precarity and stuckedness, will be analysed as part of the fabric of biopolitical power and control (Foucault Citation2010) in the camps. However, a key concern of the article, is not to focus exclusively on the ways that temporal structures related to irregular migration are shaped by legal regimes and power relationships, but to also consider how they are encountered, made sense of, and incorporated or resisted by migrants. Are we as researchers, running the danger of reproducing dominant discourses of the experience of time by the illegalized migrant as ‘wasted’, ‘unproductive’ and set outside modernity (Bauman Citation2004)? Is there a possibility of an alternative chronopolitics that could contest a reified understanding of illegalized migrants as people without past, future and without agency shaped by neoliberalization and its accelerating temporalities as imposed at the border?

Time and encampment

In the interviews with the director of the Kara Tepe camp, Mr. Mirogiannis, the migration official of the Mytilene municipality, Mr. Marios Andriotis and conversations with the guards in Kara Tepe and Moria, it became clear, that there is a plethora of regulations, rules and procedures that attempt to structure the daily life of the inhabitants of the camps and the interactions between inhabitants and camp authorities.

These included, the limits of movement of migrants as defined within international legal frameworks, responsibilities of care giving to ‘guests’ (as stated in the interview conducted with the director of the Kara Tepe camp), details on the daily menu in the camps, the zoning of the camps for different ‘populations’ depending on the strength of their applications for asylum or the zoning of the camps for daily activities such as charging mobiles, collection of food, distribution of clothing etc.

Asylum seekers, during conversations with the researcher, described endless procedures and rules to be followed with reference to daily activities, access to facilities, access to personnel and services, procedures for getting in and out of the camp, procedures during mealtimes.

Hannah, an Eritrean young woman described a highly regulated environment that is designed to structure and micromanage the daily rhythms of life in the camp. She said,

there is no violence as such, but instruction. We are told what to do, where to go. We are instructed to do this, to do that. We are not given information about what the process is, what is next, when we will have our interviews. We are just told to wait, wait, wait. For how long do we have to wait? For what reason? (Moria camp)

Hannah’s reference to violence as such and its juxtaposition to instruction, implies an element of coercion in instruction while distinguishing it from naked force (Foucault Citation2010). She clearly understands instruction, been told where to go, what to do, and the luck of information about the future, as mechanisms of power that are intended to strip them of agency. Rules on where and when to queue for breakfast, lunch and dinner, where to change their mobiles, when the lights will turn off for the night, what paperwork they had to carry with them when getting in and out of the camps, were intended to structure the daily rhythms of life through queueing and repetition. Mr. Mirogiannis, discussing life in Kara Tepe, stressed that ‘predictability and structure are important in running the camp, as order is necessary for the wellbeing of the guests’. Repetition and routinization are productive from the point of view of those managing the camps, as they contribute to the disciplining of the body of the migrant through replacing creativity and action with predictable behaviour (Arendt [Citation1958]Citation1998)). Obedience and conformity also reproduce the priorities imposed by the current EU migration system that ‘illegalises’ specific migrants (Jacobsen and Karlsen Citation2021) following criteria of deservedness or undeservedness (Aradau Citation2004; Mountz Citation2011; Appadurai Citation2013; see also: COM 2015, 240) imposed within the priorities and agendas of states and of global capitalist reproduction (Arendt [Citation1951]2017; Mountz Citation2011). It is in this context, that migrants such as Hannah, Daniel and others in similar situations to them, were located in the zone of the camp allocated to those under repatriation orders. In these instances, we can see different migrant topographies within the camps, whereby space and the facilities afforded to specific migrants that fit the criteria of the ‘deserving’ refugee, were withheld to others due to their provenance, the reasons for crossing to Europe or even the routes they took. For all, queueing, waiting, and suspension were a major part of life in the camps and they have to be understood as an integral part of complex technologies of control within the camps. As Khosravi states, ‘systematically making people stand in queues, facilitates control over bodies both spatially and temporally’ (Khosravi Citation2021, 139). Experiences of waiting or suspension, have also to be understood within specific contexts and for different activities. Quotidian forms of waiting (Hage Citation2009) or situational waiting (Dwyer Citation2009) such as waiting for services (meals, charging mobiles, distribution of necessities, seeing the doctor etc.), cannot be equated to more long term and open-ended forms of waiting such as, legal decisions, awarding or rejecting asylum status and therefore been regularised or deported, waiting for and looking forward to building what seems to be an uncertain future. It is also the case, that suspension and been stuck are not experienced uniformly. They are context dependent, subjective and experienced personally (Hage Citation2009; Dwyer Citation2009; Jacobsen Citation2021). One such example is Astar’s (one of my Syrian respondents who crossed to Lesvos from Turkey with his mother and sister) feelings of anxiety over his future. Astar’s aunts, settled in France some 30 years ago, had filled in family reunification papers and he knew they will be able to travel to France to unite with their family there. However, helping in one of the canteens in the perimeter of Moria, had facilitated acquaintances with young people from the area that had eventually led to a relationship with a young woman from the city of Mytilene. It was the possibility of having to end this relationship that was the main source of Astar’s anxiety, rather than feelings of stuckedness and of an existential worry about his moving on. For Astar, the present was experienced as a time of love and hope, in contrast to the time of despair experienced in Aleppo where he comes from. His hopes and worries for the future, were weaved both through the lens of his past experiences and of his present joy of having found love in the most unexpected of places.

Always in a queue

Comments around queues for facilities and services were one of the most important issues in discussions with illegalized migrants in both camps. It was not uncommon for people to describe ‘queues everywhere’, for food, for boiling water for tea, for charging their mobiles. It was also the case that interviewees preferred, and were indeed trying, to spend time in the canteens, outside the sun and away from queues as much as possible.

Samer, when describing the conditions in Moria, made the link between the temporal structures of a detention centre and that of Europe, in order to challenge the idea of Europe as a hospitable host. Specifically, he said:

You have to queue all the time. For breakfast, you queue for two hours, then you queue again for another two hours for lunch and then again, the same for dinner. You queue for the doctor, for cloths, for water, for making a cup of tea, for preparing milk for the children, for charging your mobile. So, I prefer to come to the canteens for a bit of shadow and to charge my mobile. Europe is a large queue. (Iraqi, Moria camp)

Similarly, Amanuel, discussing the conditions in the camp, and reflecting on the daily rhythms and tempos of life, stressed that feelings of being stuck were conditional to peoples’ ability to access alternative resources and to break the routines imposed by administrative decisions:

It is so hot that we cannot sleep. We wake up as early as the sun rises and then we have to queue in huge queues for food. Too many people in the camp and getting food takes hours. I prefer to come to the canteen to eat, although this costs money. We are new here [referring to the group of people he crossed with], and we have some money, but we know of others who are here for five or six months who have spent the money they had, and have to wait in queues for a plate of food. They find it difficult; No escape from this. (Eritrean, Moria camp)

Participants, reflecting on the routinization of everyday life (broadly understood as in Arendt [Citation1958]Citation1998), recognized that the imposed waiting, deceleration and even immobilization they experience, is part of technologies of managing hope for a future in Europe through routinisation, repetition and waiting.

However, as the conversations with Samer, Amanuel, and many others signify, queues were not experienced uniformly and were dependent on opportunity structures or constraints faced by people (Klinke Citation2013). They were also shaped by their ability to access support networks and mobilise friendships that they had developed while crossing the Mediterranean Sea or in the camps. Family and friendships struck during the journey, were a source of daily support, not only in terms of sharing limited resources, but also for protection, for keeping a place in the queue for a friend, or getting food for a relative that was not well enough to queue. Although, the mundane and repetitive nature of time as structured by administrative decisions was indeed disempowering, it was also meaningful and active (Brun Citation2015), perforated and disrupted by long walks, fishing at the harbour and teaching children how to fish, tea drinking, friendship networks gathering around the canteens outside the camps, visits to the fruit market, and digital surfing that provided important information on current news that might impact on their future. It also opened possibilities for organizing,Footnote5 volunteering,Footnote6 connecting, supporting and learning from others. As Zein, who was running his family’s fashion company in Damascus, said:

When we were in Syria, my wife [a model] and I were busy working. We were married for ten years and had no children. We now have two girls, both born outside Syria. They are a blessing. It seems we [his wife and he] were too busy working. (Moria camp)

It is therefore important to stress, that time can be both experienced as deceleration or even stasis, but also as a time of creativity. Of thinking, of building, of looking meaningfully into what has been achieved or has been lost, as well as looking forward. In this instance, for Zein, deceleration had opened up different avenues for looking forward. His love for his daughters, although did not mitigate boredom with his predicament, narrated a future filled with hope as a family unit. His comparison between speed (in his past life in Damascus) and productive deceleration in the camps (both in Turkey and Greece), narrates the possibility of a different temporality that negates Eurocentric narratives of illegalized migrants as relegated to the margins of the historical process, defined within the logic of capitalist accumulation and technological acceleration (Koselleck Citation2004).

The past erased and reclaimed

When discussing the effects of the administrative system on their ability to take decisions about their lives, feelings of being stuck, and being suspended were repeated throughout the conversations. It became clear, that perhaps, worse than the difficult conditions and queueing for services, the uncertainty of when one would be able to move on, to be able to start building a life, was by far the most challenging aspect of life in the camps as an asylum seeker.

Mariam, an Iranian young woman, talked of ‘suffering’ as an emotion that would best describe her own feelings at the time:

I was suffering in my own country and I am suffering here too. I thought it would be better here, but, there is uncertainty, no decision about what we are to do, when we will be able to move on, if we will be able to move on, and how and where. (Moria camp)

Mohamed, who crossed with his wife and two children aged 4 and 2, added that

it is worse for those that have been waiting for longer. There are people in the camp that are waiting for five or six months to move on, and although they are Syrians, there has not been any movement at all. We [he and his family], have been waiting for three months and waiting has become almost a way of life. We used to be active, working people and waiting is hard. We want to move on, to settle and to be able to rebuilt our lives, but this seems difficult. (Syrian, Kara Tepe camp)

Waiting for decisions on their futures (referred to by my participants and camp personnel as ‘cases’), was understood as part of the deployment of biopolitical technologies of control (Foucault Citation2010) that legitimize power by dealing with human beings as cases to be dealt with and sorted out. Imposed immobility and suspension of people’s productive lives through administrative controls, paperwork, numbering people, aimed at transforming doctors, nurses, teachers, translators into asylum seekers, illegals or guests. Such suspension of peoples’ creative and productive lives, were aimed at erasing their past histories and therefore erasing the possibility of a productive future or at least linking such a possibility, to decisions that they could not control (Koselleck Citation2004). In discussions on daily routines, Ahmed and Mariam said:

we spend our days in the camp, in the canteens, drinking tea and chatting, going back and forth. Not much to do and not knowing when this will end. Waiting is like being frozen. (Drinking tea with Ahmed and Mariam, from Iran, Moria Camp)

Such comments were not unusual and it is indeed the case, that time experienced as suspension was disempowering them. However, in discussions with my interlocutors, about the past and the future, two different narratives developed. For those that had fled a repressive or unfulfilling and impossible past, leaving it behind, was experienced as moving forward in search of a better future. The present was understood as a frustration, as suspension, as loss of time in the struggle for a better future, while the past formed the measure for building a better, freer and productive future. The feelings of stasis were more pronounced as the hope of escaping a torturous past seemed to become distant (see also de Genova Citation2021).

In conversations with Nataniel and Sessay, who escaped an imposed life sentence in the Eritrean army, they both insisted that they started the journey because they wanted ‘to live free, to build a life, to live like human beings’ (Moria camp) while Elyias, a fellow Eritrean that crossed the Mediterranean in the same boat, said:

We thought that Europe is good. We thought that people have rights, that we would have rights once we reached Europe. But we are uncertain now of a future. We hope, but waiting is like been frozen. (Moria camp)

Worries but also hope about the future, were repeated in discussions. Fiyori, reflecting on her frustration of not been in control of her and her family’s future, also used hope as a way to counteract her feelings of being stuck:

I still have hope, but I know of people, that as time goes on, they lose hope. They think and think and think about this place, about moving on, about why they cannot move on and get frustrated and their minds go. I thought that Europe would be different. Europe was good. People had rights. But now I do not know what to think any longer. (Eritrean, Moria)

In such narratives, I encountered a more complex discursive configuration where aspiration, the will to create, to do, instead of just ‘being’, emerged. It was not just safety that they were aspiring to achieve, but a future that would be comparable to others that live in counties freer to the ones they come from. By stressing the impossibility of a productive life in the pasts they left behind, they claimed the right to enter the western temporality that in their eyes, could secure them recognition and access to a better life. The demand was to be counted, to be recognized as human beings with rights to a ‘normal’ and ‘productive’ life. However, their criticisms of Europe, were also intended to challenge established narratives that posit illegalized migrants as devoid of agency, and to resist administrative decisions that stripped them of rights by immobilizing them and administering their access to their aspired future.

For those that were forced to leave behind what they perceived as productive pasts, their past lives were discussed as a time of productivity and pride and formed the source of resistance to narratives of ‘allochronism’ (Fabian Citation1983; Herzfeld Citation2009) that illegalized them. Javid and Farnaz, brother and sister, in an attempt to voice and substantiate their right to be recognized as equals, talked with pride about their past lives in Kabul. They explained, they were forced to leave Afghanistan with their younger brother, because their family were threatened by people linked to the Taliban, demanding Farnaz, a nurse, stopped working. They stressed that they come from a reasonably well-off and modern family with educated parents and siblings that were engineers and teachers.

Javid, shared photos, stored in his mobile, of family weddings, of his sisters in colourful elaborate dresses, of their garden, and photos of his mother and father in their comfortable house. Similarly, Ali, and his wife Aster, countered narratives of migrants as moving in search of a western lifestyle with providing photos of their house, their car and their neighbourhood in Iran. He said: ‘We had no reason to go. We had to run for our lives. I am an artist. I had a job. My wife had a job. We had a good life’. Ali, whose job is to design and mold the highly decorative plaster cornices found in Iranian houses of well off families, shared photos of his work in situ, with immense pride (Ali and Aster, Afghanis from Iran, Kara Tepe camp).

Their life in Iran, was experienced by both him and his wife, as not dissimilar to the lives of people in western countries. His photos, were a testament to having nothing to envy from western lifestyles.

Similarly, in a discussion with Farid, his wife Fatima and her brother Mahdi, Fatima countered narratives of backwardness with references to their past lives:

We were well off. We had good jobs, a big house and a comfortable lifestyle. We are educated. We run for our lives. This is not my war. This is Assad’s war and the West’s war but we pay the price for it.

And Mahdi added:

We expected better. If you are in Syria, although there was peace, …you know that Assad rules you. But you believe that in Europe there are human rights, there is democracy. This is not what I see. Here I am a number, a case, I am a problem and not a human being. Is this what human rights mean to Europe? (Kara Tepe camp)

Discussions about cases, being numbered were repeated in order to stress that the current border regime works through depersonalizing and dehistoricizing those that find themselves on the threshold of standards of citizenship and rights defined within the priorities of western nations (Arendt [Citation1951]2017). In such accounts and many more, reclaiming the past, becomes the only way to reclaim time and history and therefore to reclaim the future.

Although my respondents used western narratives of aspiring to ‘built a good life’, or of having had a ‘fulfilling and comfortable life’, of ‘been busy, active people’ back home, as a way of claiming inclusion to the metanarrative of time as defined within western historical time (Koselleck Citation2004), it is important to observe the ways in which claims to aspired inclusion to such a narrative, or claims that rejected their exemption from it, work through recalling their pasts in order to regain their futures. They were intended to destabilize and challenge their dejection from western modernity and the conditionality of their re-entrering it. It would therefore be a misinterpretation of their agency to assume that their urgent calls to be ‘unstuck’ and to move on, are internalized as wanting and accepting a ‘gift’ or a ‘concession’ made by political institutions such as national states and the EU. In their narratives of past lives lived to the full and of future lives to be built and lived to the full, a more inclusive language that unsettles definitions of historical time as exclusively western, serves as a strategy to counter and to challenge the uchronic state of migrant existence embedded in current migration regimes (Sylvester Citation2006).

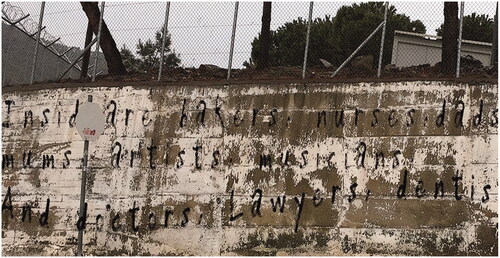

As the graffiti at a side wall of the Moria camp signifies – written in English as it was not for the consumption of those that were suspended inside – their subjugation was achieved through the marginalization of their own pasts. It has therefore to be read as an effort to resist, or at least unsettle, such technologies of control and to reclaim the future through reclaiming the past (Koselleck Citation2004) ().

Conclusion: a different chronopolitics

In this article, I have engaged with the relationship between the chronopolitics of mobility/immobility and illegalized migrants’ experiences and narratives of time, as forming a possibility of resistance towards the current EU migration regime that illegalizes specific mobilities through suspension on space and time. I have argued that the increasing academic focus on the politics of time as a category of analysis in migration studies, has brought into focus the relationship between temporality and power. This has indeed allowed for a comprehensive critique of the current regimes of migration control that have submitted understandings of space and time to processes of reproducing the current dominant geopolitical relations of power. However, inadvertently, it might also have helped in hegemonizing the very same chronopolitics that structure the life of the illegalized migrant through suspension from the tempo of modernity understood as movement, speed, and progress. I have further suggested, that migrant experiences of time and narratives of the past, the present and hope to build a ‘good’ or ‘better’ future, invite us to rethink our perception of ‘time’ experienced as inaction and suspension. A fitting way to understand time in situations of encampment is through paying attention to the developing narratives of illegalized migrants as they attempt to challenge the chronopolitics of control imposed from within the current EU migration system. For this purpose, I have used the lens of historical time (Koselleck Citation2004) as it allows us to explore demands for the future through narratives of the past. While such narratives might at first be understood as having internalised the priorities of a migration system that suspends illegalized migrants in space and time and conditions their gradual ‘re-introduction’ to the priorities of western nations, they are intended as a challenge to its exceptionality and their suspension from it. Stories of unbearable and unliveable pasts, point towards the demand to build good futures and to live ‘normal’ lives as is demanded within western modernity, while stories of pasts lived well, strengthen demands to review discourses of ‘otherness’ based on criteria of ‘exceptionality’ from it. They narrate multiple temporal trajectories, that both reproduce the chronopolitics of control experienced through feelings of temporal stagnation, but also challenge understandings of migrant subjectivities as suspended and in stasis. A vital part in challenging the hegemonic relation between time and power, is the question of voice – to claim narrative authority over one’s past and present and to be heard, as an author of one’s own future. By focusing on the voices of illegalized migrants, I suggest the possibility of an alternative chronopolitics, that understands history as multi-layered and shaped within opportunity structures and constraints that pluralise conceptions of time. Understanding time as experienced differently, ‘in between’ and beyond hegemonic temporal structures’ (Malkki Citation1995), allows us to hear those that refuse to be silenced and to acknowledge their own understandings of their self, their situation, of their rights and aspirations. It also suggests, that we ought to pay attention to acts of resistance, however small and mundane these may be. It is through these, through narratives of lives lived and lives to be lived, that express ‘affects of longing, hope or despair (Klinke Citation2013, 9), that demands to be counted are formalized and press for action.

Notes

1 Although the analysis has mainly focused on time and immobilization, space and time are both viewed as technologies of power. The camp is a form of spatialized power and the 'waiting' and other temporal practices within the camp are temporal manifestations of the very same power.

2 The term illegalized migrant is used to stress the politics of exclusion that illegalise specific movements according to predetermined criteria of deservedness or undeservedness.

3 By the summer of 2016, there was barely any movement between borders. The only migrants that were still able to move on, were those whose families already established in the EU, had submitted reunification papers.

4 All names used in the article are pseudonyms in order to protect the anonymity of my participants.

5 One such example was women organising in groups for their safety, when walking in the camp in the evenings. Parents would also organise to play and teach football to children and organising to demand services or better facilities was increasingly becoming an ‘issue to be addressed’ by camp authorities.

6 A number of young migrants, fluent in English, would volunteer their services to the NGOs that were working in the camp. The relationship between volunteers and other camp inhabitants was not always smooth, as they were often viewed as ‘having taken the role of the saviour’. They were however, mediators of accessing services, especially translation of documents for other inhabitants.

References

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller Roazen. Stanford. CA: Stanford University Press.

- Anderson, B. 2013. Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Andersson, R. 2014. “Time and the Migrant Other: European Border Controls and the Temporal Economics of Illegality.” American Anthropologist 116 (4): 795–809. doi:10.1111/aman.12148.

- Appadurai, A. 2013. The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. New York: Verso.

- Aradau, C. 2004. “The Perverse Politics of Four-Letter Words: Risk and Pity in the Securitization of Human Trafficking.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33 (2): 251–277. doi:10.1177/03058298040330020101.

- Arendt, H. [1951]2017. The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Penguin Modern Classics

- Arendt, H. [1958]1998. “With an Introduction by Daniella Canovan.” In The Human Condition. 2nd ed. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bakewell, O. 2008. “‘Keeping Them in Their Place’: The Ambivalent Relationship between Development and Migration in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 29 (7): 1341–1358. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20455113. doi:10.1080/01436590802386492.

- Balibar, E. 2004. “We, the People of Europe?” In Reflections on Transnational Citizenship. Princeton, NJ and Oxford: Princeton University Press

- Bauman, Z. 1998. Globalization: The Human Consequences. New York: Columbia University Press

- Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Bauman, Z. 2004. Wasted Lives. Modernity and Its Outcasts. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bendixsen, S., and T. H. Eriksen. 2018. “Time and the Other: Waiting and Hope among Irregular Migrants.” In Ethnographies of Waiting: Doubt, Hope and Uncertainty, edited by A. Bandak and M. K. Janeja, 88–112. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Biehl, K. S. 2015. “Governing through Uncertainty: Experiences of Being a Refugee in Turkey as a Country for Temporary Asylum.” Social Analysis 59 (1): 57–75. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590104.

- Brun, C. 2015. “Active Waiting and Changing Hopes: Toward a Time Perspective on Protracted Displacement.” Social Analysis 59 (1): 19–37. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590102.

- Cabot, H. 2014. On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Çağlar, Ayse. 2016. “Still ‘Migrants’ after All Those Years: Foundational Mobilities, Temporal Frames and Emplacement.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (6): 952–969. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126085.

- COM. 2015. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A European Agenda on Migration.” /* COM/2015/0240 final */. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=celex%3A52015DC0240.

- Coutin, S. B. 2003. Legalizing Moves: Salvadoran Immigrants’ Struggle for U.S. residency. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- De Genova, N. 2013. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1180– 1198. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.783710.

- De Genova, N. 2017. “Introduction. The Borders of ‘Europe’.” In The Borders of Europe: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering, 1–35. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- De Genova, N. 2021. “‘Doin Hard Time on Planet Earth’: Migrant Detainability, Disciplinary Power and the Disposability of Life.” In Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration, edited by C. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Karlsen, and S. Khosravi, 186–201. London and New York: Routledge.

- De Haas, H. 2008. “The Myth of Invasion: The Inconvenient Realities of African Migration to Europe.” Third World Quarterly 29 (7): 1305–1322. doi:10.1080/01436590802386435.

- Dwyer, P. D. 2009. “Worlds of Waiting.” In Waiting, edited by G. Hage, 15–26. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

- El-Shaarawi, N., and M. Razsa. 2019. “Movements upon Movements: Refugee and Activist Struggles to Open the Balkan Route to Europe.” History and Anthropology 30 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1080/02757206.2018.1530668.

- Eriksen, T. H. 2001. Tyranny of the Moment: Fast and Slow Time in the Information Age. London: Pluto Press.

- Fabian, J. 1983. Time and the Other. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ferguson, J. 1999. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ferguson, J. 2002. “Global Disconnect: Abjection and the Aftermath of Modernism.” In The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, edited by J. X. Inda and R. Rosaldo, 136–153. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Foucault, M. 2010. Michael Foucault: The Birth of Biopolitics. Lectures at the College de France 1978-1979. New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Griffiths, M. B. 2014. “Out of Time: The Temporal Uncertainties of Refused Asylum Seekers and Immigration Detainees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (12): 1991–2009. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.907737.

- Hage, G. 2009. “Waiting out the Crisis: On Stuckedness and Governmentality.” In Waiting, edited by G. Hage, 97–106. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Hage, G. 2018. “Afterword.” In Ethnographies of Waiting: Doubt, Hope and Uncertainty, edited by M. K. Janeja and A. Bandak. 203–208. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Herzfeld, M. 2009. “Rhythm, Tempo and Historical Time: Experiencing Temporality in the Neoliberal Age.” Public Archaeology 8 (2–3): 108–123. doi:10.1179/175355309X457178.

- Hutchings, K. 2008. Time and World Politics: Thinking the Present. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Huysmans, J. 2006. The Politics of Insecurity: Fear, Migration and Asylum in the EU. London: Routledge.

- Isin, E. F., and G. M. Neilsen. 2008. Acts of Citizenship. London: Bloomsbury Academic

- Jacobsen, C. M. 2021. “‘They Said “Wait, Wait” – and I Waited’: The Power Chronographies of Waiting for Asylum in Marseille, France.” In Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration, edited by C. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Karlsen and S. Khosravi, 40–56. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jacobsen, C. M., and M. A. Karlsen. 2021. “Introduction: Unpacking the Temporalities of Irregular Migration.” In Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration, edited by C. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Karlsen, and S. Khosravi, 1–19. London and New York: Routledge.

- Khosravi, S. 2014. “Waiting.” In Migration: A COMPAS Anthology, edited by B. Anderson and M. Keith. Oxford: COMPAS. Available from: https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/2014/migration-the-compas-anthology/.

- Khosravi, S. 2021. “Afterword: Waiting, a State of Consciousness.” In Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration, edited by C. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Karlsen, and S. Khosravi, 202–207. London and New York: Routledge.

- Klinke, I. 2013. “Chronopolitics a Conceptual Matrix.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (5): 673–690. doi:10.1177/0309132512472094.

- Koselleck, R. 2004. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. Translated and with an Introduction by Keith Tribe. New York: Columbia University Press

- Malkki, L. 1995. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Malkki, L. 1996. “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization.” Cultural Anthropology 11 (3): 377–404. http://www.jstor.org/stable/656300. doi:10.1525/can.1996.11.3.02a00050.

- McNevin, A., and A. Missbach. 2018. “Luxury Limbo: Temporal Techniques of Border Control and the Humanitarianisation of Waiting.” International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 4 (1/2): 12–34. doi:10.1504/IJMBS.2018.091222.

- Mezzadra, S. 2004. “The Right to Escape.” Ephemera 4 (3): 267–275. http://ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/4-3mezzadra.pdf.

- Migroeurop. 2016. “The Turkey/European Union Agreement: Externalising Borders to End the Right to Asylum.” https://migreurop.org/article2681.html?lang=en.

- Minca, C. 2015. “Geographies of the Camp.” Political Geography 49: 74–83. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.12.005.

- Mitropoulos, A., and B. Neilson. 2006. “Exceptional Times, Non-Governmental Spacings, and Impolitical Movements.” Vacarme, 34 [online]. Available from: http://www.vacarme.org/article484.html

- Miyazaki, H. 2010. “The Temporality of No Hope.” In Ethnographies of Neoliberalism, edited by C. J. Greenhouse, 238–249. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Mountz, A. 2011. “Where Asylum-Seekers Wait: Feminist Counter-Topographies of Sites between States.” Gender, Place and Culture 18 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2011.566370.

- Ngai, P. 2005. Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Oliveri, F. 2016. “Where Are Our Sons?” Tunisian Families and the Repoliticization of Deadly Migration across the Mediterranean Sea.” In Migration by Boat: Discourses of Trauma, Exclusion and Survival, edited by L. Mannik, 154–177. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Ong, A. 2006. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

- Pallister-Wilkins, P. 2015. “The Humanitarian Politics of European Border Policing: Frontex and Border Police in Evros.” International Political Sociology 9 (1): 53–69. Available from. doi:10.1111/ips.12076.

- Ramsay, G. 2020. “Time and the Other in Crisis: How Anthropology Makes Its Displaced Object.” Anthropological Theory 20 (4): 385–413. doi:10.1177/1463499619840464.

- Rozakou, K. 2021. “The Violence of Accelerated Time: Waiting and Hasting ‘during the Long Summer of Migration’ in Greece.” In Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration, edited by C. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Karlsen, and S. Khosravi, 23–39. London and New York: Routledge.

- Salter, M. B. 2006. “The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 31 (2): 167–189. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40645180. doi:10.1177/030437540603100203.

- Sylvester, C. 2006. “Bare Life as a Development/Postcolonial Problematic.” Geographical Journal 172 (1): 66–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4134874. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00183.x.

- Tazzioli, M. 2018. “The Temporal Borders of Asylum. Temporality of Control in the EU Border Regime.” Political Geography 64: 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.002.

- Ticktin, M. 2005. “Policing and Humanitarianism in France: Immigration and the Turn to Law as State of Exception.” Interventions 7 (3): 346–368. doi:10.1080/13698010500268148.

- Tomlinson, J. 2007. The Culture of Speed: The Coming of Immediacy. London: Sage.

- Tsianos, V., and S. Karakayali. 2010. “Transnational Migration and the Emergence of the European Border Regime: An Ethnographic Analysis.” European Journal of Social Theory 13 (3): 373–387. doi:10.1177/1368431010371761.

- Turnbull, S. 2016. “‘Stuck in the Middle:’ Waiting and Uncertainty in Immigration Detention.” Time & Society 25 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1177/0961463X15604518.

- van Houtum, H. 2010. “Human Blacklisting: The Global Apartheid of the EU's External Border Regime.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6): 957–976. doi:10.1068/d1909.

- Virilio, P. [1986] 2006. Speed and Politics (Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series). MIT Press.

- Walters, W. 2008. ‘Acts of Demonstration: Mapping the Territory of (Non-)Citizenship’. Acts of Citizenship, edited by E. F. Isin and G. M. Nielsen, 182–206. London: Zed Books.

- Yaris, K., and H. Castaneda. 2015. “Discourses of Displacement and Deservingness: Interrogating Distinctions between “Economic” and “Forced” Migration.” International Migration 53 (3): 64–69. doi:10.1111/imig.12170.