Abstract

Shocks linked to climate disasters are increasingly understood as intertwined with inequities, devastating livelihoods, exacerbating food insecurities and impacting migration economies. Yet there is often a lack of sustained and situated attention to how these – and diverse secondary and tertiary shocks – are experienced in relation to gender and class inequalities, other social differences and underlying forces shaping differentiated mobility-related challenges over time. Divergent experiences and histories of shocks are often simplified, with (im)mobility-related struggles misunderstood or only abstractly represented. Amid these concerns, this article explores the ‘mobilities turn’ in climate disaster research, focusing on experiences articulated by people along the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border, examining multiple impacts of climate disasters and changing dynamics of (im)mobility converging with pandemic shocks and interrelated political and socio-economic struggles. In this region, impacted by one of the world’s most severe tropical cyclones in recent memory, we explore the embeddedness of shocks in dynamic political-economic landscapes and life trajectories. Part of a multi-method 5-year project, we focus on stories where articulations around mobilities, translocal connections and mobility disruptions, including from COVID-19, call for carefully understanding socio-economic ties and histories, land alienation and access inequities, mutating meanings of borders, and factors intensifying economic insecurities amid increasingly severe and frequent climate shocks.

1. Introduction

Globally, there are now intensifying debates on ways of conceptualising linkages between various climate shocks and human mobility dynamics. Substantial shortcomings exist in dominant narratives of migration and climate crises, which often perpetuate simplified representations that obscure class inequalities, fluctuating power relations, capitalist processes and sociological differences that inflect dissimilar experiences (Baldwin, Fröhlich, and Rothe Citation2019; Whyte, Talley, and Gibson Citation2019). As argued by Parsons (Citation2019), too often in place of situated understandings are ‘abstractions on ever greater scales, which bear little resemblance to the lived experiences of migration and mobility’ (p. 684). With increasing numbers of people forced to turn to migratory practices to cope with impacts of climate change, recent literature has thus called for more detailed attention to how such shocks and mobility struggles are experienced alongside intersecting political and socio-economic injustices, including, recently, those tied to the COVID-19 pandemic (Nyahunda, Chibvura, and Tirivangasi Citation2021, Sultana Citation2021; Sheller Citation2021). These add to growing calls for in-depth qualitative approaches that attend to multifaceted landscapes of mobility and different senses of struggle for different people (Parsons Citation2019; Bettini Citation2019) and, as Baldwin and Fornalé (Citation2017) put it, the ‘pluralising’ of climate-linked migration debates in social science writing. Against the backdrop of these debates, we explore what a ‘mobilities turn’ means in understanding interlinked climate disaster-related shocks and migration-related struggles along the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. We underscore the importance of understanding migration histories, class dynamics and interrelating shocks from heterogeneous vantage points. We focus particularly on mobilities and interrupted mobilities in Chimanimani District, Eastern Zimbabwe, where a confluence of related shocks has converged, shaped by Cyclone Idai, a tropical cyclone that has been regarded as one of the southern hemisphere’s most deadly storms (Devi Citation2019).

This study is part of a larger 5-year project (2016 to 2021) employing mixed-methods approaches to understand mobilities, climate crises and livelihoods along the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. Here we draw from several of the methods employed including extensively from three of our life history interviews, particularly examining how climate disasters, including from Cyclone Idai, which hit this region in March, 2019 (almost exactly one year before COVID-19 officially emerged as a global pandemic), were experienced in different socio-economic situations, including both before and during the first year of the COVID-19 era. Our purpose is to share findings that challenge overly schematic narratives and abstractions that tend to under-recognise the diversity of climate-linked and mobility-related struggles and that risk dislocating effects from underlying inequalities and political-economic trajectories that shape them. In this sense, we are concerned here with how cyclone-related mobility changes are narrated in relation to pre-existing mobility challenges as well as how post-cyclone shocks further amplified struggles associated with disaster – all critical to ‘mobility justice’ (Sheller Citation2018) concerns that shape individual and collective experiences of change.

Globally, as COVID mobility restrictions disrupted migration and economies on massive scales, rupturing long-standing rural and urban livelihoods (Tom Citation2021), scholars have highlighted the need for more rigorous understanding of heterogeneous challenges in regions where economic, political and climate shocks are driving internal and cross-border mobility as well as immobility (Adey et al. Citation2021; Hut et al. Citation2020; Spiegel and Mhlanga Citation2022; Moze and Spiegel Citation2022). Part of the story we encountered in our research relates to migration-dependent coping strategies after Cyclone Idai and drought periods – including migratory practices in search of viable irrigated farmlands – severely disrupted by the pandemic. However, beyond a search for water/irrigated land, a range of other (sometimes-overlapping) scenarios played out, embedded in histories that speak to varying experiences of socio-economic and political change, nested in complex dynamics of grappling with contesting land and navigating power asymmetries. Our approach here includes attention to both reconfigured (im)mobilities in the form of internal mobility challenges as well as struggles for those whose cross-border social and economic movements have been disrupted, or conversely, for whom crossing borders became a lifeline. In the section that follows, we present background to the study and the multi-method approach we adopted to explore understandings of differentiated mobility and class dynamics, social ties and experiences of shocks and reconfigured (im)mobilities. While our research draws on diverse ethnographic techniques, we focus in the next section on particular life history interviews – reflecting distinct positionalities and experiences, engaging various inequities and coping struggles linked to mobility and climate disaster in this border region. Finally, we conclude with some broader messages, linking this work to wider critical propositions for advancing work on climate crisis-linked (im)mobility struggles in relation to diverse migration drivers, impacts and politically shaped socio-economic relations.

2. Background and methods – approaching shocks and mobilities

Social geographies of shocks and mobilities can be only partially understood through discrete event-based analyses. Robust understandings require a variety of relational analyses that extend beyond single time-bound ruptures, including multiple land and migration histories, labour relations, transformation triggers – and situated experiences, including experiences of overlapping shocks through time. This study discusses research in Eastern Zimbabwe that – in part – traces diverse shocks and struggles shaped by Cyclone Idai – a climate disaster that hit Zimbabwe as well as Mozambique and Malawi in mid-March of 2019. This cyclone destroyed farmlands, road infrastructures, homes, lives and livelihoods in this region on unprecedented scales (Manatsa et al. Citation2020). As others have stressed, socio-economic shocks of Cyclone Idai have been devastating throughout Chimanimani District (along the border with Mozambique), resulting in population displacements, lost livelihoods in the short and long term, intensified concerns about inequitable governance, and a disproportionately high loss of life compared with other places affected by the cyclone (Nhamo and Chikodzi Citation2021; Manatsa et al. Citation2020). In the days and months following the cyclone, Chimanimani became known globally as a disaster zone – and a place receiving insufficient donor assistance and inadequate national government support. Pledges to ‘build back better’ and relocate settlement infrastructures were only fractionally implemented after vast mudslides and flash floods that, in some cases, destroyed entire settlements beyond a trace (Nhamo and Chikodzi Citation2021). A noted horrific cross-border impact was epitomized by the sight of Zimbabwean dead bodies being swept away in rushing flooded rivers that took them to Mozambique, some found eventually, but some never identified and repatriated.

As short-term post-cyclone assessments stressed, Cyclone Idai affected 270,000 people in Zimbabwe, with 51,000 displaced, more than 340 officially confirmed dead and many others missing, in addition to the fact that ‘Scores of children were orphaned, while female survivors faced gender-based violence…Roads and bridges in Chimanimani and Chipinge were severely damaged; some 1,500km of the road network was rendered unusable for months, affecting market access’ (Chatiza Citation2019, p. 5). In the aftermath of this cyclone, we ask how are the impacts of this climate disaster understood as embedded in wider socio-economic and political processes shaping mobilities? The three authors, two of whom are Zimbabweans local to this province (Manicaland), draw upon numerous stages of our collective ethnographically immersive research in Chimanimani District since 2016, including each year since. This includes multiple phases working directly with members of the Chimanimani Rural District Council on post-cyclone recovery research and with traditional leaders and a range of people throughout the 2016–2021 period (with numerous phases contributing to learning about shocks, livelihood challenges, water insecurities and other facets of life for local and migratory populations). The specific part of our methodology that informs a major part of this article centres on oral life histories shared during fieldwork carried out in April 2021. A central aim was to generate insights on how people experienced shocks associated with climate disaster and saw these altered/exacerbated by impacts of the COVID pandemic and interrelated mobility-related struggles.

Our discussion here is nested in a context of ongoing, protracted economic and political crises that have been deepening across Zimbabwe for years – shaping what has long been conceptualised as a ‘kukiya-kiya’ economy (in Shona) or informal economy of ‘making do’ (Jones Citation2010). Writings on migration in Zimbabwe have accentuated diverse roles of informal trade and ‘translocal’ livelihoods that at times include non-agricultural activities such as artisanal mining, exploring mobilities within Zimbabwe and across its borders (Kachena and Spiegel Citation2019; Mkodzongi and Spiegel, Citation2019; Mkodzongi and Spiegel Citation2020). This work explores trajectories of migration and social struggle that can also be traced back, in part, to the deleterious effects of Economic Structural Adjustment Programmes in the 1990s but also high degrees of military spending that have crippled public budgets and ongoing governance crises that influence high unemployment rates (Tendi, McGregor, and Alexander Citation2020; Hammar Citation2014; Helliker, Bhatasara, and Chiweshe Citation2021). Complementary critical work that engages mobility/displacement in agrarian settings invites attention to exploitation, reconfigured labour regimes, land alienation and roles of social networks in Zimbabwe (Shonhe, Scoones, and Murimbarimba Citation2022) as well as cross-border migrant insecurities (Rutherford Citation2020; Bolt Citation2019). Increasingly, climate change studies in Zimbabwe have also cautioned against neglecting the inequalities bound up with different trends in climate-linked migration, with women, for example, particularly vulnerable to suffering disproportionately (Chidakwa et al. Citation2020).

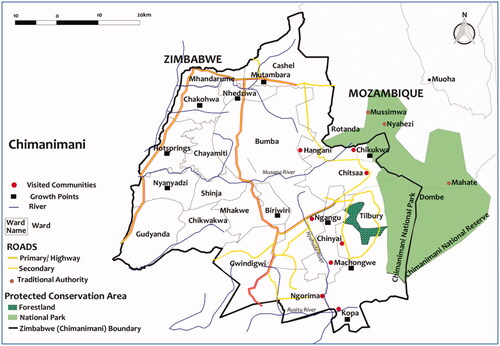

Among various critical questions regarding mobilities in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai, we focused on various vulnerable groups severely affected by ongoing shocks. The fieldwork closely engaged peasant farmers, informal traders, artisanal miners, business operators and community leaders who possess vast knowledge of dynamics unfolding in the region. Interviews also frequently highlighted the critical need to problematise these very categories and how they may be simplistically invoked by outsiders; we sought to explore how ‘local’ and ‘migratory’ people may weave in and out of multiple kinds of livelihoods and occupying fluid – rather than fixed – identities in their lives, often transforming to cope with difficulties. Our fieldwork explored situated understandings and approaches to withstand impacts of shocks, including food security strategies under various forms of restrictions linked with the pandemic, along with how mobilities were shaped at multiple points before and following cyclones – both Cyclone Idai and other cyclones. We used various combinations of in-depth oral history interviews, community maps, role plays, photovoice and transect walks with people from the main communities involved in this research including in Chimanimani Urban, Chinyai, Chitsaa, Chikukwa, Ngorima, Kopa and Machongwe, areas that have been described in only limited ways in past analyses of Cyclone Idai, and only in terms of short-term impacts (Chatiza Citation2019; Manatsa et al. Citation2020). While specific details of each of these methods along with insights and results from the various techniques adapted in different locations at different phases of the research programme will comprise separate articles currently in progress, our focus here is on drawing some broader critical observations, with particular focus around Kopa and Machongwe () – places heavily affected by Cyclone Idai.

Methodological orientations often prioritise large surveys and aggregated datasets, prompting arguments by Parsons (Citation2019), as alluded to in our introduction, to resist ‘abstractions on ever greater scales’. Notwithstanding the importance of quantitative and meta data analyses that cover multiple community settings, intimate narrative approaches can provide more sustained attention to particularised vantage points, voices and personalised experiences, exploring how multiple reflections from an interviewee may co-exist in a single narrative. It is in this spirit that our discussion below explores specific oral life histories. While our research in Chimanimani in the 2016–2021 period involved more than 200 people in storytelling and arts-based methods, this article focuses on just a few examples of the oral life histories, understanding this research technique as a method that carries the power to convey symbolic and material meanings of change, including interviewees’ multi-faceted narrations of recent and longer-reaching histories (Osterhoudt Citation2018). The main interviewees whose stories we discuss here intimately shared both personal histories prior to 2019 and recollections of 2019–2021 shocks. Different from ‘disaster storytelling’ where prioritisation might be on bringing interviews somewhat quickly to particular resilience and recovery policy themes, the purpose of oral life histories here is to narrate, through personal lenses, situated senses of socio-economic struggles negotiated through converging shocks and aspects of positionality, class and mobility in this border zone.

Oral life history methodologies can, as Rogaly (Citation2015) suggests, disrupt routine migration simplifications through attention to class and other social dimensions, sometimes subtly. Part of the first author’s long-term research programme in Chimanimani – entitled ‘Reconfiguring Livelihoods, Re-Imagining Spaces of Transboundary Resource Management’ – the authors were in Chimanimani both before Cyclone Idai struck (in March 2019), conducting research on a range of mobility issues, and afterwards, including when the COVID pandemic was declared (March 2020) and a year later. At these various points we heard from residents and migrants about concerns regarding what new shocks might bring. In the weeks and months after the cyclone, we also actively participated in various aspects of community support (including distributing solar chargers to help with phone communication, along with workshops that supported two Chimanimani District Council-supported clean water programmes for marginalised settlementsFootnote1). While the early months of the pandemic involved virtual/telephone contact with people in Chimanimani whom we had come to know well over the preceding years, the interviews below, thirteen months post start of the pandemic, were conducted through physically-distant on-site interviews (with pseudonyms used for interviewees’ names, to preserve anonymity).

Our discussion here stresses that understanding the synergistic impact of one shock merging with another in the long-term post-cyclone period requires attending to socio-economic and mobility dynamics that can be narrated in heterogeneous ways by different people, with variances that may relate to aspects of geography, gender, age, disability, livelihood practices, mobility routes, trajectories, different abilities to build alliances for mitigating challenges, and otherwise. To understand struggles of people affected by the cyclone requires engaging diverse narratives of trans-local livelihoods, diverse ‘layering on’ effects of climate shocks that include ongoing droughts (Chingombe and Musarandega Citation2021), subsequent economic shocks that materialised, in this case, in the form of COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions across Zimbabwe (Tom Citation2021), and intersecting political forces and economic relations that transcend Zimbabwe’s borders. Gender, class, age, ethnicity and political networks all need to be understood as connected dimensions, all inflecting different understandings of mobility and inextricably linked forms of mobility that make up what Mimi Sheller refers to as ‘mobility justice’. Below we begin by presenting various stories to illustrate the multiple mobility trajectories and impacts following Cyclone Idai, focusing extensively on the life history of one female cyclone survivor’s displacement. We then situate struggles with two main stories, each offering avenues for seeing different life trajectories and positionalities: first, a case of internal displacement/domestic mobility and second, a case of cross-border mobility.

3. Climate shocks and experiences of mobilities before and after Cyclone Idai’s devastation

3.1. A multitude of trajectories shaped by Cyclone Idai

In the early period after Cyclone Idai, our learning about post-cyclone shocks focused on immediate economic challenges across all sectors, with effects including psychological trauma and loss of farmlands, livelihoods, seeds and infrastructures. What was particularly poignant was the extent to which shocks mapped onto many complex histories of land alienation and economic marginalisation, inflected by years of capitalist dispossession and colonial planning that shaped land zoning. These factors, in turn, stemmed from the subordination of traditional governance structures to commercial interests and population management regimes that have served extractive interests by the powerful (Hughes Citation2011; Kachena and Spiegel Citation2019). These patterns of land access shaped migration trends and trans-local social, ethnic and kinship ties in this region, sometimes including social networks that long transcended Zimbabwe’s border with Mozambique (Hlongwana Citation2021), with cross-border linkages continuing to critically impact social and economic life. Over time, our fieldwork encountered many migratory people in Chimanimani who do not neatly fit into categories and whose stories were quite diverse. Some rarely crossed the border into Mozambique; some, by contrast, regularly crossed the border. In many cases, residents we came to know well – both before and after the cyclone – did not necessarily cross the border regularly but were confronted with ever-growing challenges including increased reliance on new migration dynamics to access water and viable/irrigated farmlands after the cyclone and found themselves traversing new ‘property’ borders (without leaving Zimbabwe) to pursue food security strategies. New challenges sometimes mapped onto pre-existing displacement threats and pre-existing mobility trends, amplifying a sense of already-existing injustice. Some people were fearful of moving locations, even if they knew their current locations were vulnerable still to mudslides. In some cases, we met people who were told by state officials that they needed to move from their current location, but believed strongly that such edicts had to do with powerful actors’ interest in controlling the land to exploit its resources. Life histories in the short-term after the cyclone gave us insight on some of the material and symbolic struggles of people who lost their homes.

We begin our observations with what we learned from various women we interviewed in Kopa, Machongwe and, particularly ‘Grandma Muusha’, in Ngangu (Chimanimani Urban) who shared with us detailed stories on moving to the neighbourhood that turned into one of Zimbabwe’s worst ever climate disaster zones. Granda Muusha moved to the area when she married a man who was working for a white family in Chimanimani’s Low Density Suburb. They spent much of their lifetime living in Ngangu Traditional Village (opposite to the current Ngangu Urban Village). When her husband retired, they bought a Council Stand in Ngangu Urban using his pension funds. However, when the Council was supposed to hand her over the residential stand, the stating that her money was devalued since she was paying the amount in Zimbabwe Dollars through the instalment method during the 2006-8 economic meltdown period. With the stand they had bought now sold to someone who paid the full amount in USD at once, she was given another stand, alongside a waterway, in the area later affected by floods, lamented how the Council ignored her concerns in this regard. Over the years when her husband retired and after he died, she survived by sewing clothes and knitting jerseys. When we interviewed her, it was her first day to return back to her house 30 days after the cyclone because ‘she could not get the courage of going back to her homestead’ until her son visited her from Harare to recover household items that were swept by floods. She was overwhelmed with emotion that they were able to find sewing machine still safe, amidst the rubble.

Grandma Muusha described how she was awoken in the middle of the night on March 14 of 2019, finding herself engulfed in rushing water that felt both cold and hot at the same time, hearing horrible loud sounds and seeing her house utterly destroyed to rubble and her neighbours’ houses washed away by a dead-of-night flash-flood. Her life history was shared with us 30 days after these horrible events, and she reflected on her hopes that all people, not just those who owned houses, would find a safe settlement. She commented on the district council’s complicity, shaped by years of colonial planning and then post-colonial district politics, that resulted in people living where they were, in precarious settlement places that stood in potential waterways. Grandma Muusha also reflected on her life history alongside the history of the settlement planning, where houses were built too close to each other. Since the cyclone 14 March 2019 Grandma Muusha have been living at the Roman Catholic Church, later the Chimanimani Hotel and later given a tent in Ngangu among other victims. She would be one of many, ultimately, to await a much-delayed more robust government resettlement support plan.

Other stories shared by women in Kopa and Machongwe – two other places, the former’s settlement structures completely wiped away by flash-floods – detailed how the cyclone caused unimaginable suffering (e.g. see and ). A local female farmer who was selling fruits at Kopa Market showed how the disaster has left many people in abject poverty without food, since gardens were washed away by the floods. She stated that people are now surviving on gold panning in the Nyahode River (). Pointing to the photo of her destroyed granary she brought to one of our photovoice sessions, another a woman explained ‘…This picture will always remind me of the life I lived before the cyclone…. I lost not only my home but my business and loved ones…. As a woman I am struggling to deal with the disaster as aid is male dominated and far reaching for us women’. Some survivors told us that many people from Kopa ultimately choose to relocate in Machongwe, as we discuss in the next section, sometimes amid highly patriarchal relations that mediated donor agency assistance.

Figure 2. ‘These are the remnants of what was formerly a hub of business and urban growth point, with homes and shop – laid to the ground by the ravage of Cyclone Idai’. The female farmer who shared this (in a photovoice narrative at the Peacock tuckshop area, near Machongwe) described how this place became desolate and filled with rock debris, with the picture hinting at how people lost homes, businesses, land for agriculture and loved ones due to the cyclone.

Figure 3. ‘I took this picture because I still cannot comprehend what happened here. Here is where I lived and did subsistence farming. My crops were destroyed and what remains is this flowing river to remind me of the water that we cried for. Taichemera n’anga ichadya mai…We wanted rain because our crops were drying and we didn’t want a drought, not knowing the coming of rains will bring us destruction. We were happy when it rained non-stop until the rain started to take our own’. (Female farmer, discussing cyclone impacts in Kopa, photovoice narrative during site visit, 2019).

Figure 4. ‘Disaster left many people in poverty without food…gardens were washed away by the floods…People are now surviving on gold panning. Nyahode River and its streams are congested with [gold] panners – both local and migrants. Red muddy water in this pool is coming upstream where mining is happening, we used to get fish from Mozambique but very few vendors are crossing to buy fish for reselling here because everyone is hesitant of crossing Haroni River due to Cyclone Idai events, therefore local men are now resorting to fishing in mining polluted waters. They are selling the fish here at the market’. (Female farmer, photovoice narrative during site visit, Nyahode River in 2020).

![Figure 4. ‘Disaster left many people in poverty without food…gardens were washed away by the floods…People are now surviving on gold panning. Nyahode River and its streams are congested with [gold] panners – both local and migrants. Red muddy water in this pool is coming upstream where mining is happening, we used to get fish from Mozambique but very few vendors are crossing to buy fish for reselling here because everyone is hesitant of crossing Haroni River due to Cyclone Idai events, therefore local men are now resorting to fishing in mining polluted waters. They are selling the fish here at the market’. (Female farmer, photovoice narrative during site visit, Nyahode River in 2020).](/cms/asset/dfd68d9d-5ecc-460d-8dd6-6cd8f9835ebc/rmob_a_2099756_f0004_c.jpg)

Land availability for displaced and migratory people in Chimanimani has been inhibited, in part, by systems of monopolistic forest and land concessions that constrict where areas for relocation and livelihoods are ‘legally’ allowed. Delays in state-administered support for displaced populations, and ongoing disaster risks, have been some of the most prominently reported consequences of governance failures after cyclone impacts. One very specific population of concern were those stranded in government-designated ‘tent communities’ for more than two years, awaiting government-promised resettlement – a highly public controversy that has been discussed elsewhere as part of national government failures to implement equitable resettlement programmes, akin to how the infamous Tokwe Mukose resettlement programme was unjustly implemented (Mucherera and Spiegel Citation2021). Yet, other people in Chimanimani were less visible in public media debates, differently situated in ongoing struggles around space, identity, economic ties and land – with no anticipated ‘resettlement’ programme ever emerging, and with no ‘tent communities’ dictating people’s whereabouts either.

3.2. Trans-locality, class and reconfigured mobilities – a life history explored in Machongwe

When we visited Machongwe in the weeks after the cyclone, we encountered many stories of suffering and shock, with class inequalities conspicuously at play, as many of the most affected people in the cyclone were people who had little economic means. Two years later – and one year after the COVID pandemic was declared, our research focused on what was referred to as the ‘Machongwe Business Centre’ or (informally) ‘Machongwe Growth Point’.Footnote2 Here we conducted in-depth discussions with women and men of diverse age groups involved in various economic activities; they included shop owners, welders, carpenters, taxi drivers, vegetable vendors, and motor mechanics. Participants shared stories about their life histories and how they came to settle in Machongwe. Some of the participants grew up in the Machongwe area, while others migrated from elsewhere. We also discussed issues related to trans-local, circular, and distance mobility in the region and how much movement is being shaped by climate disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the economic hardships following Cyclone Idai, many participants shared how they ventured into new livelihoods such as mining and farming in order to survive. Machongwe’s experiences were thus arguably an acute microcosm of a wider trend across Zimbabwe – of depending increasingly on ‘translocal’ (Mkodzongi and Spiegel Citation2020) coping strategies for food security.

A local carpenter operating at Machongwe, Mr Moyo, offered a history that situated exclusion in land ownership as well as past environmental struggles that preceded recent shocks in this region. Mr Moyo shared that his father migrated from Dzingire in 1981 to Kushinga Village (which is along the Nyahode River) during early resettlement program that was initiated soon after independence:

Very few people were eager to migrate by that time. My father migrated because he wanted to acquire good land for us since there were 10 boys in our family. He got 10 hectares of land. My father further acquired other pieces of land in the area for gardens and pastures…During those days land was accessible because the area was less populated…I recall that there were only 10 black families and three white farmers in Machongwe. Having tracks of land made my father very popular during that time.

He continued to share how his livelihood and migratory history was shaped by climactic and weather factors. ‘We used to farm potatoes for sale. However, we later stopped because of the rains. Apart from farming my father used to have a huge flock of sheep. Due to deteriorating weather conditions, we started to grow maize and practiced cattle ranching’. When he got married in the early 1990s, he migrated to Harare to look for a job, explaining: ‘that’s where I learned to do carpentry though I was once doing it at Allied Timbers. In 2006 I lost my job at a construction company I was affiliated with for years in Harare, mainly due to poor environmental conditions prevailing in the country during that time’. He thus described how he decided to migrate back to the village. ‘I worked for a few months as a seasonal worker at Allied Timbers before I migrated to Mozambique for employment opportunities’. In Mozambique, he opened a furniture shop. He spent three years in Mozambique before he migrated to Botswana and later to South Africa. ‘I worked for five years in South Africa before I decided to return here to Zimbabwe. I decided to upgrade my homestead. In 2012 I opened a furniture shop here at Machongwe Growth Point. I was the first carpenter to start this business here. I am the one who has fitted the shelves of these shops’.

Migrants from various regions in Chimanimani and abroad settled in this area. Mr Moyo recalled how Machongwe was established during colonial times by white settlers as a resting point for timber trucks from Tarka Sawmill, then further populated by banana farmers from nearby reserves such as Ngorima. After independence, the area was revamped by the government to service newly established schools, such as Kushinga Primary School and Nyahode Secondary School. Managed by Chimanimani Rural Council, the area was planned to be both residential and commercial, with metered water and electricity attracting many people to establish their businesses here. The residential area now accommodates more than 1000 houses – settled by locals as well as outsiders,Footnote3 some from Rusitu whilst others from as far as Chipinge, Masvingo, and Mutare. The population is diverse and intermarriages are common. Popular because of its central location, close to towns and communities, business people can buy supplies from Chipinge, Mutare, or Mozambique where they are cheap, and resell them here to diverse communities. People with capital have opened grocery shops to serve the growing surrounding population, with people migrating here attracted by an increasing population of artisanal miners and bush millers. Commenting that ‘It is well known that artisanal miners spend so much, so businesses just follow wherever artisanal mining is happening,’ Mr Moyo further indicated that ‘business people pretend they are solely operating grocery shops yet they are buying precious stones from illegal miners’. This dynamic, he explained, exploded after Cyclone Idai.

Mr Moyo also shared how settlers in Machongwe reacted to Cyclone Idai and how the aftermath of the disaster shaped business and other activities. Expressing that the cyclone painfully devastated the entire Chimanimani region, he described it as a ‘natural war with an invisible commander’, adding: ‘we lost relatives and loved ones….but we need to move forward and think of the future…We were fortunate that unlike other growth points and residential areas like Kopa and Ngangu, Machongwe survived the Cyclone Idai devastation’. The havoc wrought by Cyclone Idai on other business areas such as Kopa, Ndima and Ngangu led to the massive outward migration of people to establish their business in Machongwe: ‘People have seen Machongwe as a safer zoneFootnote4 than other growth points, recently when Cyclone Charlene was announced I witnessed other Cyclone Idai victims migrating here for safety. Even outside migrants find Machongwe a safer settlement area as compared to many other growth points’. Apart from road networks being more viable and easier to navigate in the event of any disaster, people can more easily connect to Chipinge, Mutare, and Chimanimani compared to other growth points. ‘Imagine those in Kurwaisimba when a disaster occurred like a Cyclone Idai it will take time for them to get assistance’.

Apart from claiming lives, we learned from Mr. Moyo how other impacts of Cyclone Idai are amplified by COVID-19: ‘the impacts of the pandemic on the community are unbearable…We cannot afford the methods to protect ourselves…Many people have never worn a mask since COVID-19 started…. In December last year, we heard that two people (a father and son) in Rusitu died after contracting COVID-19 at a funeral in their village. Following this incident no one was doing business here, people became hesitant to gather or associate with strangers’. This growth point, he explains, became ‘a ghost place’ for three months; this was further amplified by the government's lockdown policies aimed at restricting the movement of people. ‘It became difficult for everyone to access food, health care, and above all education given that all services were absolutely closed or partially functional. The lockdown was monitored by police, several roadblocks were instated in highway roads connecting us to Chimanimani, Chipinge and Mutare. In some cases, police would do patrols at Machongwe to ascertain if people are adhering to stipulated lockdown regulations’. Explaining the difficulties, he lamented: ‘Apart from being socially monitored, we were economically crippled as a result we became very poor and incapacitated to live a decent life. No one wants the life we are living under this COVID-19 pandemic. All basics are now expensive, very few people can afford to buy basics such as cooking oil, sugar, soap, and salt. This is because the shop owners are taking advantage of lockdown to increase the prices of basic commodities’.

Various economic parallels exist between Cyclone Idai and COVID-19. While Cyclone Idai in 2019 led to raised prices due to the presence of donorsFootnote5 and disruption in road networks needed for delivery of goods,Footnote6 during the lockdowns prices of all basic commodities dramatically increased, attributed in large part to restriction in crossing into Mozambique where commodities were less expensive:

COVID-19 has brought suffering to us; we cannot survive in this situation. For people like me who are conducting business that is not related to food [in his case, being a carpenter], it is now worse because no one can opt for having a kitchen table instead of food – everyone is prioritizing getting food before anything. It is the time we need similar food assistance that we got from donors during Cyclone Idai, but I think the problem is that everyone across the world is in this similar condition therefore no one can assist us. Some locals used to receive groceries from relatives in South Africa but this has changed during lockdowns because public transport is not allowed to operate and it is expensive for many to utilize the services of runners (Malaicha) from South Africa to Chimanimani.

As a personal story of migration across Mozambique, Botswana and South Africa, as well as internally within Zimbabwe, Mr. Moyo’s story was a stark illustration of how mobility within and across borders was both driven by and restricted by various shocks, with the pandemic dramatically exacerbating the impact of climate disaster. While COVID-19 is affecting poor peasant farmers in the region, Mr Moyo also reflected how business people in the area are shifting their economic activities to focus on acquiring land – contributing to what has elsewhere been termed ‘climate gentrification’ (Aune, Gesch, and Smith Citation2020) to refer to the buying up of desirable land,Footnote7 rendering it more expensive in turn (and thus less accessible to certain marginalised segments of society):

Following Cyclone Idai land demand was high since many victims were searching for new safer places to settle. This also gave pressure to business people and those living peri-urban setups who want to at least own two or more homesteads in case of any future disasters such as floods, to avoid becoming stranded following a disaster like what is happening to Cyclone Idai victims who have now two years living in camps…We also have instances of other community members who have sold both their farmland and residential land to migrants.

We learned that apart from migrants, local people were also buying land, especially those who were living along rivers, streams, or valleys. ‘People panic when Cyclone Charlene was announced this year; locals are living in fear of these natural disasters so they are doing anything they deem possible to prepare themselves for any future hazard like Cyclone Idai. Increasing demand for land has led to an increase of its value…’ He spoke of an example of the selling of a 200 m2 piece of land (for USD1, 500) and how Chimanimani Rural District Council is selling residential stands of the same size double the price. It was clear that COVID-19 had further increased the demand for land in this region because lockdowns impoverished the peri-urban population who were depending on their business for survival:

Imagine owning a shop that you need to pay rent each month for stocking your goods but not operating, it was a really tough time for many. As a result, many of them quit their business to join farming. As you know, the residential stands in Machongwe are small, measuring 200m, so many people looked for plots for farming. We have witnessed migrants who are living in Machongwe making farm renting arrangements with farmers in surrounding villages such as in Kushinga, Chirawu, and Chinyai. For instance, my neighbour rented out three hectares to two families from Machongwe peri-urban.

Prices varied based on land size and soil type and that sometimes payments were made with fertilizer seeds or basic food commodities such as sugar, salt, and soap. ‘In Kushinga’, Mr Moyo expressed, ‘I know of several villagers who rented out their fields to people in peri-urban Machongwe…. This arrangement has become a relief for many villagers because it allowed them to access food during a difficult era’. When asked if this is a balanced arrangement Mr Moyo explained that the ‘business people renting land are the main benefiting much because their harvest will be worth more than groceries they paid each for three months…but it is a win-win case because villagers are renting out fields that they are not tilling’. Notably, other interviewees indicated to us that land renting is often not always a win-win situation and, indeed, far from it – occasionally narrated through the language of ‘exploitation’ – with land rental dynamics presenting highly uneven socio-economic arrangements. To ‘disrupt’ the migration story here, to underline our argument and the methodological point made by Rogaly (Citation2015) now requires attending to how a very different narration of economic exploitation that unfolded in different spaces, times and social settings within our research area.

Further narratives by others offered additional perspectives on the economic challenges of Cyclone Idai, exacerbated by COVID19, resulting not only in mobilities that relate to land sharing arrangements but that also led to intensified dynamics of ‘going into the bushes’. As one nearby neighbour (Patience [another pseudonym]) narrated, also someone who left Kopa after the horrific flash-floods, maintaining a food shop in Machongwe has required extensive engagement in trans-local states of being. ‘…We suffered severe losses. Instead of operating in shops, I was forced to transport my stuff into the forests and mining fields so that I can reach out to bush millers and artisanal miners who are our main buyers’. He continued: ‘…However, this was not an easy task to move into the mountains with goods, but there was no option because I was trying to beat the expiring date of some food items that were in stock since November 2019. It was a stressful time to do business in the lockdown era…It was supposed to be time for our business to flourish but it was the opposite’.

In this post-cyclone context, allegations by locals that businesses doubled prices of basic commodities after the crisis hit speak to what might be understood as a form of what Naomi Klein called ‘disaster capitalism’. Stories of leaving Kopa and relocating in Machongwe speak to a social mobility path that is unevenly experienced by people of different classes, and although UN agencies and UN assistance organiations have often given short-term support, aid programmes have not invested in long-term infrastructure for farming; and not everyone has managed to settle from Kopa. These variations also make up different lived components of ‘trans-locality’ – a notion that has been important to extend beyond oversimplified views that fix people to particular places. As Naumann and Greiner (Citation2017) wrote, this notion – translocality – may be used to conceptualise how relations and practices spanning multiple localities play essential roles in social and economic life around mining. In their case, addressing South Africa, struggles are conceptualised in relation to forces of colonialism and capitalism that have widely structured limitations on people’s movements as well as the desire to be mobile – and to build relationships and pursue new mobilities. Here too, we argue for deeper historicizing mobility research in ways that link ‘colonial histories, political ecologies, and bio-politics, as well as a deeper excavation of the material bases of mobility in extractive industries’ (Sheller Citation2016). Machongwe’s trajectory fits powerfully into this call, with the pressures of climate disasters and pandemics layering onto other socio-economic pressures to critically constrain livelihood prospects.

3.3. Struggle and mobility through the prism of border-crossing

While dramatic reconfigurations to internal (domestic) migration dynamics have been pervasive in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai and the emergence of COVID-19, the border’s meanings and cross-border experiences have also transformed, materially and symbolically. Restrictive measures have been unevenly navigated by different people, with the borderland movement differently conceptualised in relation to droughts, cyclone impacts and other shocks. Writings by Hughes (Citation2011) detail historically fluctuating power dynamics and changing notions of ‘flexible citizenship’ linked with people who cross the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. His work, contextualising how cross-border trade has long been a pillar of everyday life, forms a useful backdrop upon which to frame experiences of Walter, a cross-border trader from Manica, Chimoio, who sells second-hand clothes for men, women, and children. In 2021, Walter shared with us how the border zone, which long existed as a space of interaction for Zimbabweans and Mozambicans, was devastated by Cyclone Idai, then, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, mobility was further severely constricted, severely affecting trade opportunities for him and others. He also shared a further ‘new’ shock: like other Mozambicans, Walter is afraid of the Islamic extremists’ attacks unfolding in Mozambique in 2021, noting that if measures are not taken to halt these insurgencies, he foresees many Mozambicans feeling forced to migrate to Zimbabwe, imperilling both countries’ efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 and further exacerbating livelihood struggles.

Although from the Mozambican side of the border, Walter has maintained strong ties with Zimbabwe since he was 16 years old when he started working for a family in Sakubva, Mutare for two years. It was during this time when he learned to speak chiShona. When he returned to Mozambique, he started selling footwear, clothes, and basic food commodities in areas where artisanal gold mining was taking place, supplying food commodities to miners in Manica from 1999 to 2003, before shifting to Chimanimani Mountains in 2004 following the gold boom in the region. Given that by this time he was conversant in Shona, he managed to trade (cigarettes, beer, food and clothes) in Zimbabwean-dominated mining fields along the border especially in Musanditeera (‘no man’s land’). Having had to cease selling his goods in Musanditeera due to massive raids on artisanal miners by both Zimbabwean and Mozambican police (mainly Mozambican Park guards and police, and sometimes ZIMPARK rangers), he later tried selling his goods in Zimbabwean townships along the border of Mozambique, and since 2013, has been selling clothes and footwear in Vumba, Chigodora, Chikukwa, Rusitu, and Mutambara. He narrated that cross-border trading is not an easy business especially when using unregulated cross-points:

…In 2016 I was caught by Chimanimani Police at Jandiya (a crossing point in Chikukwa) I was also fined and spent three days in custody…I was not sent to court. They asked me to go back to Mozambique immediately. However, I managed to hold the matter and befriended some of the police officers at the camp; to date, we are now good friends, and am no longer afraid of being arrested. Every trip I bring them nice clothes and shoes. Some of them are now assisting me to find more customers…

Apart from having formed relations with state security, he developed strong ties with other business owners such as shopkeepers and taxi drivers. ‘Such a relationship is helping to conduct business in Zimbabwe. Since I do not rent a house here’, he explained, ‘whenever I come I put over at a friend's shop in Chimanimani Township’. In some cases, when business is low, he described distributing his items to local shop owners so that they can sell his wares and collect the proceeds on the next trip, sharing details of bringing bath soap and soup for friends in Ngangu – an urban Chimanimani settlement severely damaged by Cyclone Idai.

Walter also describes his identity as someone who works with more than 10 cross-border traders, operating in Nyanga and Chipinge as well as Chimanimani, selling different items such as kapenta, dried fish, plastic ware, soap, beer, and cigarettes. Emphasising the importance of good relations with communities, especially people in Chikukwa, their crossing point into Zimbabwe, he noted:

We use some traditional paths when crossing from Rotanda-Mozambique to Chikukwa-Zimbabwe through the Jandiya road. Along the way, some communities make our journey quite easy…On the Mozambican side, the communities along the border are sparsely populated so we hire locals in Rotanda to ferry our stuff to the Zimbabwean side. Apart from ferrying goods for us, these locals are so knowledgeable about the area, given that the border area was once full of landminesFootnote8, they took us through safe paths.

Providing groceries and other items that are difficult for others to access in their areas, Walter further recalled that two years previously he was assisted by a Headman (traditional leader) in Jandiya after one of the streams he crossed in the village was too full for him to cross. ‘I cannot count how many times I was assisted by local leaders during my trips’, he reflected, recalling how social relationship are also cemented through trading relations. He shared with us that they trade fairly with local people in Chikukwa and that being fair is deeply important: ‘Since people in rural communities rarely have access to cash, I exchange my stuff with grain particularly rapoko (finger millet) and wheat which I will later sell to communities…in Mozambique. Apart from rapoko, I have benefited much from farming communities along the way. I even exchange clothes with beans, for instance, a jacket that goes for USD 5,00 will be equivalent to 5kgs of beans. The only challenge of exchanging crops or small livestock is transporting them back to Mozambique which is also costly’.

Apart from trading, Walter adds ‘I also help unemployed Mozambicans to get some on-farm jobs in newly resettled areas such as Jandiya and Hangani. I cannot recall the number of cattle herders I have connected with farmers in Hangani’. All these details help us to understand his adaptive social capital as well as the uneven social terrain for informal economic affairs. Walter is clearly able to cope relatively well compared with many others we met; he has access to US dollars and to relatively regular selling markets (many people have neither), and he is able to be mobile and navigate multiple police/authority structures. Notwithstanding these relations, however, climate struggles – including both droughts and recent cyclones – have presented deep challenges to mobility and trade – and Walter shares some of his experiences, too.

Echoing stories by Granda Muusha and Mr. Moyo after Cyclone Idai on how food security and livelihood security are major challenges, Walter recalled that in 2014 when Zimbabwe was struck not by cyclones but rather by droughts, his livelihood went through difficult hardships and changes; he explains: ‘In areas like Mutambara, for instance, people are not interested in buying clothes or shoes because they rarely harvest well due to poor rains so they often spend their money on buying grain’. He adds: ‘As a result of droughts, cross border trading is becoming very common among locals here in Zimbabwe’. He recounted how he also witnessed people from Nhedziwa who are involved in cross-border trading buying foodstuffs such as cooking oil, fish, and kapenta from Chimoio for barter exchange with grain in their communities. ‘Recently’, he explains ‘due to increasing droughts in the Nhedziwa area, people are receiving money as food donations from donors’. He is able to sell some of his ware because some people are diverting part of these funds to buy clothes, shoes, or other foodstuffs like cooking oil, spaghetti, rice, and even beer. When asked about cyclone events, Walter shared some of the difficulties he had faced since March 2019: ‘Due to Cyclone Idai, I spent three months not coming to Zimbabwe; my family was hesitant for me to come here…When I decided to resume my trading here in August 2019 the journey was hectic…because our usual pathways and crossing points on rivers and streams were significantly transformed making it difficult to move…’

In addition, he explained that due to Cyclone Idai he is no longer conducting business during the rainy season because of safety concerns in crossing rivers – given stories of people washed away by Cyclone Idai. ‘Last year, for instance, when Cyclone Charlene was announced on the radio [announced late December 2020] I immediately stopped all my cross-border activities…I am now working less than six months a year’. His reference to Cyclone Charlene – a storm that triggered fears of a repeat of Cyclone Idai (although ultimately not as bad) and temporary mobilities in Chimanimani – hints at the state of fear that many people experience in the sensitive mountain landscape where deforestation and other extractive activities have intensified vulnerabilities (Truscott Citation2019).

Walter briefly recounted how some people sustain a livelihood by taking up sporadic opportunities in resettlement areas like Hangani, such as digging water trenches. These are ‘piece jobs’ – part of a disaster recovery effort that is constricted by cash shortages, where short-term digging is done in exchange for food. From our discussions with the Chimanimani Rural District Council and Agritex (the extension service that supports agricultural projects) as well as interactions with people in Hangani, we became aware that these have been highly limited ad-hoc jobs. Although the International Organization for Migration (IOM) conducted snapshot survey analyses that indicated that some of Chimanimani’s internally displaced people ‘do not intend to relocate from their current places of residence and that support in terms of livelihoods is required’ (IOM Citation2021), government programmes to facilitate jobs have not materialised and sometimes have stymied livelihood opportunities. Walter notes that ‘people have received donations in the form of clothes, blankets, and shoes so they are no longer buying my stuff because they have already received the items’. He also expressed how deeply uneven the donor assistance has been – some communities have been cut off completely from receiving food aid, six months after Cyclone Idai therefore increasing competition of accessing menial farm jobs for food with mobile Mozambican migrants.

Apart from climate disaster, Walter shares how the COVID-19 pandemic was shaping cross-border mobility (from Mozambique to Zimbabwe): ‘Surviving in this pandemic period is luck – how can we survive whilst mobility from one town to another is restricted?’ Furthermore, a wider context clearly affects this: ‘Since COVID-19 lockdowns are being initiated by all countries this affects shipping of second-hand bales of clothes to Mozambique, therefore the quantity of the clothes is now low compared to the last years. In addition, the stuff is now expensive given that the demand is also high whenever the lockdowns are lifted’. Walter reflected that due to lockdowns, mobility from Chimoio to Zimbabwe is now expensive, as well. ‘Before we used to pay an amount equivalent to USD 10.00 for a taxi from Chimoio to Rotanda, but now we are paying USD20.00’, he details. ‘This is because there are many more roadblocks than before so at each roadblock I have to pay a bribe to the police so that they allow me to go without explaining to them where and why I am traveling’. He also shared that during his first trip after lockdown he was caught by Zimbabwean police who were patrolling the border region, particularly illegal border crossing points: ‘It was unfortunate that I was caught. The police who caught me was new to the region and they confiscated 75 pairs of shoes which I later redeemed after paying a bribery token of USD 50.00 to them’. He adds: ‘Mobility is now problematic…of course, I now know how to deal with Zimbabwean police. If they caught me I would just bribe them but I am afraid that I might come across Zimbabwean soldiers along the border. A friend of mine shared with me that here in Zimbabwe soldiers are now part of the roadblocks and border patrols following COVID-19’.

While, for Walter, the shocks created immobility constraints hindering his cross-border livelihood, for others, crossing the border was a lifeline to survival because the shocks had devastated other possibilities for them. Other cross-border mobilities we encountered in our research included travels of women in highly precarious labour crossing the border to form relations with artisanal miners and earn some foreign currency through sex work – some of whom endure far more arduous journeys and exploitation. A changing pattern to transnational commercial sex work was specifically noted: ‘Normally I do not want to talk about this – even so, this has become my reality and that of many women here due to loss of livelihoods. I am a single mother with four children aged between 3 and 15’. Sharon went further to explain how it has become difficult for her to reconstruct livelihoods after the cyclone:

I had lost all my goats, chicken and banana business. I was left with nothing. Some women are engaging in transactional sex with local leaders to get food and tents in exchange but I prefer to do my hustles away from my children. Personally, I prefer to work in Mozambique, you know the idiom muroyi royera kure vepedo vakutye [‘in order to maintain respect where you come from never expose your bad works to your neighbours.’]

She added,:

Of course Kopa was known to be the Sodom and Gomorah of Chimanimani [co-operatives formed for selling agricultural produce which had a the high circulation of money, hence attracting commercial sex work] and I used to judge women [who went] into commercial sex work. Now things have changed, after realising that my children can no longer eat at least once a day, I had no option but to get into Mozambique. Initially my plan was to find a job but with no place to stay I soon resorted to commercial sex work. I have no passport. I cross illegally into Mozambique through Cashel. Now I go to Mozambique usually after every 2 months and I can stay there for at least a month, the longest I have stayed is three months. I met there with many women from Chimanimani and many from Kopa especially those previously in the trade. Most women who worked as commercial sex workers here in Kopa are now migrating to and from Mozambique due to loss of business and limited money after the cyclone. Though not legal it was confirmed that many female migrants migrate to sell sex in the bordering Mozambique area, going as far as Beira, contributing to increased numbers of feminised migration which is both risky and exhausting as routes have even become longer.

Understood together, Walter’s life history narrative and Sharon’s story of cross-border sex trade gesture to multiple forms of unevenness in mobility-related socio-economic possibilities: between encountering police versus encountering soldiers, between informal livelihood prospects for who may have experience transacting with these authority figures versus those who might not, and class dynamics that may influence uneven abilities to pay the high costs of keeping afloat; they also gestures to how the border has mutating social meanings, between those for whom the crossing the border had long been part of their social and economic well-being, and those for whom crossing the border was forced upon them to conduct commercial activities best done far from one’s local community.

4. Concluding remarks

Struggles linked to climate disasters and mobility changes can be shaped by deep losses, powerful emotional experiences and profound economic impacts months and years after initial shocks. This article has provided a glimpse into just a small selection of experiences of ‘secondary’ shocks of climate disasters and COVID-19 shocks in Eastern Zimbabwe, where multiple mobility-related struggles converge, and where a critical ‘mobilities turn’ is layered onto different identities and connections to place. Narratives here illustrate that close attention to positionality, including dimensions of class and multiple social histories and place histories, are needed when cultivating understandings of what we might call ‘social geographies of shocks and mobilities’. Life histories hint at how variations exist in experiences of crossing borders (encountering exploitation, engaging securitised borders with soldiers and/or police, etc.) and how vast differences exist, as well, with regards to internal mobilities that have changed in the 2019–2021 period. Mobilities – such as migration from flash-flood-hit places such as Kopa to ‘safer’ business centres like Machongwe – present uneven life trajectories, land access challenges and power-laden inequities. To invoke one of Maxim Bolt’s arguments about life history narratives (in his case, exploring the South Africa-Zimbabwe border), ‘a single case cannot generalise’ (Bolt Citation2016) – and indeed it would be amiss to broadly generalise from a few stories; rather, exploring subtleties in different stories offers indispensable ways of countering generalisations. Each narrative here points to alternatives to broad-brush accounts that might flatten, schematise and reduce social experiences to a mere trajectory of movement – devoid of situated social, emotional and economic meanings. Our first and foremost concluding point, therefore, is that a mobility lens in relation to impacts of climate disasters such as floods, mudslides and droughts requires critical understandings of various socio-economic aftermaths of multiple climate shocks and variable languages of life histories and place connections.

Secondly, narratives here point to specific histories of exclusionary forms of capitalism– how histories of landlordism and exploitation, as well as vulnerabilities and struggles inflected by economic marginalisation – are deepened by climate crisis. While the COVID-pandemic has both amplified challenges from climate disaster shocks and dramatically curtailed institutional efforts to ‘build back better’ after Cyclone Idai, class and land ownership inequalities have intensified. Contemporary land struggles in Zimbabwe have origins in a colonial system of land monopolisation that has only partially been altered (Helliker, Bhatasara, and Chiweshe Citation2021). Although the life stories we emphasized in this study were not those experiencing immanent threats of forced eviction (which are stories we also encountered and are the subject of other articles in progress), they reflect how economic struggles are not being alleviated despite government ministries’ and United Nations agencies’ pledges to support climate adaptation and recovery. Some of the regional land-based exploitation dynamics squarely fit within the rubric of disaster capitalism; others perhaps less conspicuously to the ways in which land ownership domination, pricing and purchasing by powerful and/or economic actors inadvertently marginalise others. Cheap labour regimes also emerge, opportunistically for powerful actors, in post-disaster relocation spaces, reconfiguring meanings of livelihoods and coping. From the United States to Zimbabwe to Bangladesh and beyond, the global community is now repeatedly hearing stories of how ‘historic investments’ are needed after disasters – as, we saw, for example, after Hurricane Ida in the United States brought flash floods to New York in 2021 (BBC Citation2021) – flood scenes not entirely unreminiscent of Eastern Zimbabwe. Yet, failures to support families of those washed away and failures to alter systemic patterns and structures of economic inequality persist. Systemic inequities, highly situated social experiences and altered connections to place all together form part of challenges to mobility justice. While the mantra of climate adaptation (Bose Citation2016) easily misses how climate adaptation practices may result in new struggles, the case study of Machongwe, as discussed here, also illustrates a tendency towards informal resource extraction booms and land buying sprees, in some cases involving policy, military and other powerful actors, highlighting the need for a critical ‘mobility’ turn that pays attention to these consequential relationships.

Third and finally, as life histories can offer valuable methods for interrogating climate disaster’s diverse relationships to (im)mobility, we stress that different gendered, class and cultural points of emphasis in life history interviews all provide a vital nexus for learning and re-imagining movement near and across borders. Borders may be both internal (e.g. property borders) and international. While the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border is notably less securitised than the Zimbabwe-South Africa border, the life histories explored here highlight some of the power-laden experiences at play in crossing it and also raises the question of whose voice in articulating border-crossing, economic shocks and social networks governs the wider meta narrative of disaster mobilities. To ‘interrupt’ a migration history, as Rogaly (Citation2015) suggests, is to challenge overly schematic narratives of movement and of ‘fixity’, recognising a plurality of possibilities. Critical mobilities studies, Rogaly argued, should ‘both focus attention on connections between mobility–fixity and structural inequalities and provide a more nuanced account of individual subjecthood that militates against caricatures and stereotypes that can themselves contribute to experiences of inequality and oppression’ (p. 541). If climate disaster and COVID-19 have taught us nothing else, it is to engage that thought again – and to ask: whose sense of oppression and whose sense of inequality will structure how these profound interlinked challenges will be narrated in the years to come? And how will places be re-imagined not only alongside large policy and institutional debates but also alongside the rich life histories of the people who inhabit them?

Acknowledgements

This research emerged from a multi-method project funded by an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Future Research Leader Award to the first author, further supported by various grants from the Global Challenges Research Fund and the University of Edinburgh. It was possible due to generous and kind support from local traditional leaders, local council members and many others in Chimanimani. Special thanks to Farayi Mujeni for invaluable contributions and support, and to this journal's peer reviewers who offered helpful comments. We are deeply grateful to everyone who participated in this research, shared experiences, offered advice and support and welcomed us in the many learning processes in Chimanimani throughout the various phases of the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

Notes

1 Our approach to exploring mobilities and mobility-related struggles included actively working with community participants in following up stories shared and engaging organisations, for example, to secure funding for two robust water infrastructure projects, serving households and students in Masiza and Westward Ho! Primary School in Chinyai. Both communities are facing unending marginalisation from resource extraction induced-displacements. The community in Masiza was displaced from Charleswood by a large mining company in 2014. While this will be the subject of a separate article, our point here is that exploring the ‘mobilities turn’ through action research surfaces a multitude of injustices and histories of displacement and displacement-in-place, water access struggles and impacts of institutional structures of oppression.

2 The term ‘growth point’ is widely used in Zimbabwe to denote settlements in rural areas designed for economic and physical development with basic infrastructure and a strong residential element offering variety of services that attract rural non-farm activities. Although the term ‘Machongwe Growth Point’ is sometimes used by residents in Chimanimani, Machongwe does not have the formal status of a government-designated growth point – and often is referred to as ‘Machongwe Business Centre’. Designated growth points elsewhere have been understood as part of state efforts at curbing or managing rural and urban migration, through provision of services in established centres, and for economic growth planning. The informal invoking of ‘growth point’ reflects the sense of Machongwe becoming increasingly significant as an economic hub, sometimes thought of as a semi-urban hub. (In a wider review of terminology, Scoones and Murimbarimba [Citation2021] discuss a hierarchy of terms reflecting varying levels of semi-urban/urban development in the lexicon of planners – consolidated villages, business centres, rural service centres, district service centres, growth points, towns and cities.) The discussion here includes ‘growth point’ to reflect economic imaginaries and language that participants invoked.

3 On the 25th of March 2019 when two of the researchers were distributing non-food items to Cyclone Idai survivors in Machongwe, one of the female survivors expressed that ‘many people living in Machongwe area are not from within Chimanimani but actually are migrants who used to work in commercial farms (timber plantations and tea estates)…when farms ceased operations following land reform migrant workers ventured into trading business and many are acquiring residential stands as their permanent homes in the growth point area’.

4 Similarly, during an in-depth interview with a local government engineer (28 August 2019), reflections were shared on being part of the planners who designed Machongwe residential stands in 1995. As he expressed: ‘I am so proud that Machongwe was not affected by Cyclone Idai, it shows that we did a very a good planning job and the settlement is the safest growth point settlement in Chimanimani East developed after 1980’.

5 Many disaster response workers and experts from dozens of United Nations agencies and other international agencies descended upon Chimanimani for a period in 2019 leading to increased costs for hotel bookings and related services across the region.

6 This was also extensively debated by participants in Chikukwa during a knowledge sharing workshop (26th July 2019) where participants fumed that whilst many lives were lost to Cyclone Idai, economic hardships associated with price increases compounded the disaster for cyclone survivors. To some, the price increases following Cyclone Idai were simply a reflection of costs business people had to incur to deliver goods into the region due to much longer and more treacherous road networks having to be used following damage to the original roads. Others reflected that the price increases were a sign of increased demand for food across the region since many lost food reserves and crops to the cyclone. Based on social media reports, youth participants, however, saw the price increase as largely consistent with the broader economic dynamics unfolding at the national level.

7 Cases we encountered are associated with what Chimhowu and Woodhouse (Citation2006) described as ‘vernacular markets’; like other Shona ethic groups, among the Ndau (Chimanimani) people, land is customarily owned. In our findings, locals with excess pieces of land were selling the land to migrants (non-locals or strangers); to legitimise, the buyer will pay token of legitimising ownership to the Chief/village head; by doing so the buyer becomes an official land holder and then ceases to be an outsider or stranger – but will remain a non-local since belonging is not only characterised by ownership of land but ancestral ties to the land.

8 Landmines were implanted in the 1970s along the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border by Rhodesian forces during the second liberation struggle, in a bid to prevent mobility of guerrilla fighters crossing to Mozambique for military training or returning from Mozambique to execute military operations in the country.

References

- Adey, Peter, Kevin Hannam, Mimi Sheller, and David Tyfield. 2021. “Pandemic (Im)Mobilities.” Mobilities 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/17450101.2021.1872871.

- Aune, Kyle T., Dean Gesch, and Genee Smith. 2020. “A Spatial Analysis of Climate Gentrification in Orleans Parish, Louisiana Post-Hurricane Katrina.” Environmental Research 185: 109384. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109384.

- BBC. 2021. “Storm Ida: Death Toll Climbs to 45 Across Four US North-East States.” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-58429853.

- Baldwin, Andrew, Christiane Fröhlich, and Delf Rothe. 2019. “From Climate Migration to Anthropocene Mobilities: Shifting the Debate.” Mobilities 14 (3): 289–297. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1620510.

- Baldwin, Andrew, and Elisa Fornalé. 2017. “Adaptive Migration: Pluralising the Debate on Climate Change and Migration.” The Geographical Journal 183 (4): 322–328. doi:10.1111/geoj.12242.

- Bettini, Giovanni. 2019. “And yet It Moves! (Climate) Migration as a Symptom in the Anthropocene.” Mobilities 14 (3): 336–350. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1612613.

- Bolt, Maxim. 2016. “Accidental Neoliberalism and the Performance of Management: Hierarchies in Export Agriculture on the Zimbabwean-South African Border.” The Journal of Development Studies 52 (4): 561–575. doi:10.1080/00220388.2015.1126252.

- Bolt, Maxim. 2019. “Crisis, Work and the Meanings of Mobility on the Zimbabwean-South African Border.” Social Im/Mobilities in Africa: Ethnographic Approaches 155–177.

- Bose, Pablo. 2016. “Vulnerabilities and Displacements: Adaptation and Mitigation to Climate Change as a New Development Mantra.” Area 48 (2): 168–175. doi:10.1111/area.12178.

- Chatiza, Kudzai. 2019. Cyclone Idai in Zimbabwe: An Analysis of Policy Implications for Post-Disaster Institutional Development to Strengthen Disaster Risk Management. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Chidakwa, Patience, Clifford Mabhena, Blessing Mucherera, Joyline Chikuni, and Chipo Mudavanhu. 2020. “Women’s Vulnerability to Climate Change: Gender-Skewed Implications on Agro-Based Livelihoods in Rural Zvishavane, Zimbabwe.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies 27 (2): 259–281. doi:10.1177/0971521520910969.

- Chimhowu, Admos, and Phil Woodhouse. 2006. “Customary vs Private Property Rights? Dynamics and Trajectories of Vernacular Land Markets in Sub‐Saharan Africa.” Journal of Agrarian Change 6 (3): 346–371. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2006.00125.x.

- Chingombe, Wisemen, and Happwell Musarandega. 2021. “Understanding the Logic of Climate Change Adaptation: Unpacking Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation by Smallholder Farmers in Chimanimani District, Zimbabwe.” Sustainability 13 (7): 3773. doi:10.3390/su13073773.

- Devi, Sharmila. 2019. “Cyclone Idai: 1 Month Later, Devastation Persists.” The Lancet 393 (10181): 1585. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30892-X.

- Hammar, Amanda (Ed.). 2014. Displacement Economies in Africa: Paradoxes of Crisis and Creativity. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Helliker, Kirk, Sandra Bhatasara, and Manase Kudzai Chiweshe. 2021. Fast Track Land Occupations in Zimbabwe: In the Context of the Zvimurenga. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Hlongwana, James. 2021. “Borderless Boundary? Historical and Geopolitical Significance of the Mozambique/Zimbabwe Border to the Ndau People (c. 1940–2010).” Doctoral diss., North-West University, South Africa.

- Hughes, David McDermott. 2011. From Enslavement to Environmentalism: Politics on a Southern African Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Hut, Elodie, Caroline Zickgraf, François Gemenne, Tatiana Castillo Betancourt, Pierre Ozer, and Céline Le Flour. 2020. “COVID-19, Climate Change and Migration: Constructing Crises, Reinforcing Borders.” IOM Environmental Migration Portal Blog Series. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/covid-19-climate-change-and-migration-constructing-crises-reinforcing-borders.

- IOM. 2021. “Zimbabwe Return Intention Survey – July 2021”. https://displacement.iom.int/reports/zimbabwe-return-intention-survey-july-2021?close=true.

- Jones, Jeremy. 2010. “Nothing is Straight in Zimbabwe’: The Rise of the Kukiya-Kiya Economy 2000–2008.” Journal of Southern African Studies 36 (2): 285–299. doi:10.1080/03057070.2010.485784.

- Kachena, Lameck, and Samuel J. Spiegel. 2019. “Borderland Migration, Mining and Transfrontier Conservation: Questions of Belonging along the Zimbabwe–Mozambique Border.” GeoJournal 84 (4): 1021–1034. doi:10.1007/s10708-018-9905-0.

- Manatsa, Desmond, Kudzai Chatiza, Terence DarlingtonMushore, et al., 2020. Building Resilience to Natural Disasters in Populated African Mountain Ecosystems. Case of Cyclone Idai, Chimanimani. Zimbabwe, Chimanimani: TSURO.

- Mkodzongi, Grasian, and Samuel J. Spiegel. 2019. “Artisanal Gold Mining and Farming: Livelihood Linkages and Labour Dynamics after Land Reforms in Zimbabwe.” The Journal of Development Studies 55 (10): 2145–2161. doi:10.1080/00220388.2018.1516867.

- Mkodzongi, Grasian, and Samuel J. Spiegel. 2020. “Mobility, Temporary Migration and Changing Livelihoods in Zimbabwe’s Artisanal Mining Sector.” The Extractive Industries and Society 7 (3): 994–1001. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2020.05.001.

- Moze, Francesco, and Samuel J. Spiegel. 2022. “The Aesthetic Turn in Border Studies: Visual Geographies of Power, Contestation and Subversion.” Geography Compass 16 (4): e12618: 1–17. doi:10.1111/gec3.12618.