Abstract

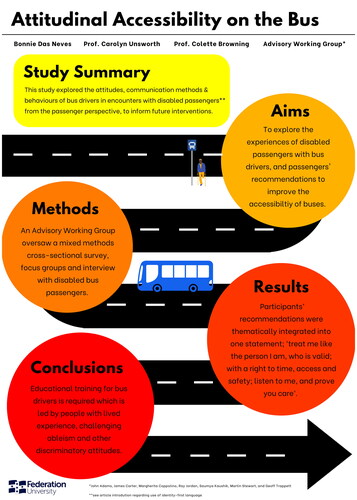

Whilst the essential nature of built environment accessibility has been well established in transport research, attitudinal, behavioural, and communication barriers experienced by transport users remain largely overlooked. Subtle and insidious, repetitive negative attitudes, behaviour, and communication can force disabled passengers out of the most affordable transport option available. Applying the Disability Justice Framework and a Mobility Justice approach, this study investigated disabled passengers’ reported experience of bus driver attitudes, behaviours, and communication methods, and the impact of these encounters. A mixed methods cross-sectional survey and focus groups with disabled adults and support persons were conducted. An Advisory Working Group of transport accessibility advocates, all with lived experience, were engaged to oversee the study design. Participants reported that some bus drivers demonstrated ableist attitudes, discriminatory behaviour, and communication methods. Many passengers had reduced or stopped catching buses altogether due to these negative encounters, restricting their community mobility, which further impacted their quality of life. Participants’ recommendations for drivers, operators, and transport authorities were thematically integrated into one statement, reinforcing the power of attitudinal access—‘treat me like the person I am, who is valid; with a right to time, space and safety; listen to me, and prove you care’.

Graphical Abstract

Language Note: Identity-first (‘disabled person’, ‘Autistic person’) rather than person-first (‘person with disability’) language is applied in the Disability Justice Framework (Berne et al. Citation2018). As this research applies this identity-based model, identity-first language has been used, with the exception of ‘people who are blind or who have low vision’ which is the preference of an Advisory Working Group (AWG) member. The researchers acknowledge alternative preferences and affirm all persons’ right to be referred to how they wish.

Introduction

Mobility represents not just an expression of autonomy (Asplund, Wallin, and Jonsson Citation2012), but of belonging (Fallov, Jørgensen, and Knudsen Citation2013). Given the significant barriers to private transport for many disabled people (Lubitow, Rainer, and Bassett Citation2017), accessing public transport becomes a prerequisite for community mobility. Whilst physical parameters of accessible public transport are well established (Velho et al. Citation2016), the impact of transport staffs’ attitudes and communication methods on accessibility remains under-researched, under-recognised, and under-addressed (Bigby et al. Citation2019). Questions of ‘transportation justice’ should reach beyond typical questions of access, to ‘also concern itself with the cultural meanings and hierarchies surrounding various means of and infrastructures for mobility’ (Sheller Citation2018); that is, understanding systemic, intersectional barriers and enablers to transport access. This study explored bus driver attitudes, behaviour, and communication in encounters with disabled passengers. ‘Bus’ was operationally defined as public, road-based, fixed-route buses in metro and regional areas which transport passengers within a locality, including government and privately run bus operators. This definition excluded coaches, which take passengers across longer distances to a small number of locations, and para-transit (segregated) services which exclusively transport disabled passengers, as they present different challenges to passengers and drivers which were not the focus of this investigation. The literature review defines access, specifically attitudinal access, drawing on identity-based and intersectional disability justice and mobility justice frameworks. It also asserts the need for attitudinal accessibility research on buses to facilitate mobility justice.

Defining attitudinal accessibility as mobility justice

Moving beyond the social model of disability, to identity-based disability models

Disability has historically been defined within ableist models which medicalised (Franklin, Brady, and Bradley Citation2020), individualised (Bollinger and Cook Citation2020), and tragedised (Swain and French Citation2000) disabled people. These perspectives, respectively: emphasised functional limitations over personhood; failed to recognise the impact of inaccessible environments initiated and perpetuated by ableist systems, on disabled persons; and, instead, marginalised disabled people as ‘tragic cases’ (Bollinger and Cook Citation2020). A paradigm shift to the social model was initiated in the 1970s, with activists arguing it is society’s physical and social inaccessibility that ‘disables’, rather than solely a persons’ functional barriers (UPIAS Citation1976). The social model asserted the right of disabled people to have choice, control, and independence, and the need for more accessible environments including inclusive attitudes. Alternative models of disability have since emerged, such as the minority (Hahn Citation2002; cited in Mitra Citation2018), and identity or affirmative models. These frameworks build upon the ‘liberatory imperative of the social model’ (Swain and French Citation2000), but also include positively identifying with ones’ disability, centring disability as a core part of identity, often likening disability identity to race for example (Frederick and Shifrer Citation2019). These models fail to acknowledge the multifaceted discrimination or privilege a person may experience as their disability intersects with other identity factors (Frederick and Shifrer Citation2019).

An intersectional approach to defining disability

A binary comparison of data from disabled people and non-disabled people erases the multiple, intersecting identities that many disabled people may embody (Goethals, Schauwer, and Hove Citation2015). Crenshaws’ formative work ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex’ (Crenshaw Citation1989) gave birth to the now broadly used term ‘intersectionality’, which, in its original context, challenged the framework whereby forms of social injustice, such as racism and sexism were seen as discrete. Beliefs about what disability is, and misconceptions about what disability ‘looks like’, all intersect with wider beliefs about race, gender, age, and many other factors. Whilst these factors are frequently considered in isolation in transport literature (Pyer and Tucker Citation2017), an intersectional framework is vital to understand the myriad of attitudinal discrimination experienced by many disabled people (Jampel Citation2018), and to see disabled people as ‘whole’ people, with complex histories and identities (Berne et al. Citation2018).

Reimagining disability rights as disability justice

The Disability Justice Framework is a lived-experience led framework that asserts that ‘all bodies are unique and essential’, and that;

‘each person has multiple identities, and…each identity can be a site of privilege or oppression’ (Berne et al. Citation2018).

As such, the framework is deeply intersectional, recommending the deconstruction of multiple systemic social injustices to change life experiences for all disabled people moving forward (Berne et al. Citation2018).

Therefore, the research reported in this paper examines not only ableism, but also how other identity factors intersect with how ableist communication, attitudes, and behaviours are experienced by disabled passengers when interacting with bus drivers. Rather than exploring these factors as discrete categories, researchers are led by the participants’ narratives of their uniquely complex experiences of attitudinal discrimination and apply the Disability Justice Framework to the analyses undertaken.

Another applied key principle of the framework is Cross-Disability Solidarity (Berne et al. Citation2018). Physical mobility, and questions of built environment access have dominated understandings of disability and accessibility (Bigby et al. Citation2019). Acknowledging diversity in lived experience, requires acknowledging diversity in definition of disability and ableism; for example, many people in the Deaf community identify as a socio-cultural group (Leigh, Andrews, and Harris Citation2018) but may still experience ableism. It is argued that research exploring accessibility should be cross-disability-inclusive to ensure recommendations benefit all passengers.

Disability justice as mobility justice

Mobility justice is concerned with the power of ‘discourses, practices and infrastructures’ to promote or prevent mobility and asserts models which improve just mobility access (Sheller Citation2018). The Disability Justice Framework is a natural extension of mobility justice, in that it seeks to dismantle systems preventing the mobility of all disabled persons, and forge inclusive paths forward. From the width of the pavement to the way transport schedules are communicated, to the treatment of passengers by transport staff; every part of the transport journey of disabled people is decided by ‘mobility regimes that govern who and what can move (or stay put), when, where, how, and under what conditions’ (Sheller Citation2018, 26). Systemic ableism is therefore positioned to restrict the mobility of disabled people in a very literal sense. Mobility justice research not only provides ‘critical analysis of historical and existing mobility systems, but also models future transitions that might help to bring about alternative cultures of mobility’ (Sheller Citation2018, 20). Rather than explore the doomed-ness of disabled community members in an ableist society, research is required to deconstruct those barriers, centring on participants’ recommendations to improve transport for disabled passengers. Therefore, a mobility justice lens is applied in this research as it not only elevates understanding of what constitutes access, and barriers to the same but pivots on exploring emerging ways to improve mobility for all.

An occupational approach to attitudinal accessibility

As occupational therapists, the researchers apply an occupational lens to define attitudinal accessibility. Occupational therapists understand ‘occupation’ to be more than just ‘productive’ activities, such as work or leisure, rather meaningful ‘doing’, ‘being’, ‘belonging’, and ‘becoming’ (Wilcock Citation2002; Hitch, Pépin, and Stagnitti Citation2014). An occupational definition of accessibility is offered, which is the means to do, to be, to belong, and to become. Attitudinal accessibility, therefore, is concerned with the societal, systemic, or personal attitudes, beliefs, and ideas, and their consequential behaviours, which deny meaningful occupation. Following is a review of the emerging research available on attitudinal accessibility in transport.

The accessible bus imperative

Un- and underemployment of disabled people due to societal ableism (Schloemer-Jarvis, Bader, and Bohm Citation2022), and deficient funding options, restrict means to utilise accessible private transport (Lubitow, Rainer, and Bassett Citation2017), making public transport a prerequisite for community mobilisation for many disabled people. Buses in particular, which are available without extensive infrastructure, such as rail tracks and stations, and therefore able to enter non-metro locations, are in many countries the most common form of public transport accessed by disabled people (Beatson et al. Citation2020). Given the restrictions elsewhere, public bus inaccessibility can therefore literally end community mobilising for some disabled people, making inclusive bus transport essential. Whilst the built environment barriers to bus access (both in terms of infrastructure and the vehicles themselves) have been comprehensively researched (Park and Chowdhury Citation2022), the role of bus drivers, in facilitating the journeys of disabled passengers, has not been sufficiently investigated (Stjernborg Citation2019). The customer-facing nature of a bus drivers’ role; the requirement of practical assistance or bus equipment used by some disabled passengers; the environmental barriers surrounding bus access; and the lack of alternative transport options (Park and Chowdhury Citation2018), all point to inclusive bus drivers being essential determinants of bus accessibility.

Research explicating bus driver attitudes, behaviour, and communication

Very little research has been conducted specifically investigating disabled passengers’ experiences with bus drivers. Instead, comments on bus driver behaviour are often imbedded in wider studies looking at other aspects of transport accessibility (see e.g. Unsworth et al. Citation2019). Participants across transport accessibility research report bus drivers demonstrate inappropriate or ineffective behaviour (Risser, Iwarsson, and Ståhl Citation2012; Unsworth et al. Citation2019; Velho et al. Citation2016), or communication methods (Peck Citation2010) and negative attitudes towards disabled passengers (Buning et al. Citation2007; Belcher and Frank Citation2004; Øksenholt and Aarhaug Citation2018; Risser, Iwarsson, and Ståhl Citation2012; Stjernborg Citation2019). Complaints typically referenced bus drivers being rude (Stjernborg Citation2019), driving past passengers (Bezyak, Sabella, and Gattis Citation2017; Buning et al. Citation2007; Risser, Iwarsson, and Ståhl Citation2012; Unsworth et al. Citation2019); acceleration, cornering, and braking practices threatening to unbalance passengers (Risser, Iwarsson, and Ståhl Citation2012); and not calling out stops (Bezyak, Sabella, and Gattis Citation2017).

Only two articles that interviewed bus drivers were identified, both reporting negative attitudes towards disabled passengers (Fast and Wild Citation2019; Tillmann et al. Citation2013). Inadequate training among bus drivers was cited in these articles as contributing to a lack of knowledge of disability, and resultant attitudes towards disabled passengers (Fast and Wild Citation2019; Tillmann et al. Citation2013). Research to date has also not specifically investigated identity factors, such as gender, race, or age, and how they interact with experiences of ableism from bus drivers. The studies have adapted more restrictive definitions of disability or only looked at one ‘area’ of disability for example people who are blind or have low vision (Fast and Wild Citation2019). Given the lack of comprehensive and inclusive data sets on the issue, and the significance of the impact on disabled passengers of bus driver attitudes and behaviour identified in the existing literature, there is an urgent need for a targeted, inclusive investigation into bus driver encounters with disabled passengers, and the impact of these encounters. Therefore, the aims of this study were to explore:

the experiences of disabled passengers and/or support persons in relation to bus driver attitudes, behaviour, and communication methods

the impact of these experiences; and

disabled passengers and/or support persons’ recommendations to improve the attitudinal accessibility of bus transport.

Ethics

Ethics clearance was obtained from Federation University Australia’s Human Ethics Committee (Project No. A21-064).

Methodology

Design statement

The pragmatic, mixed methods study, included a cross-sectional survey and qualitative focus groups, overseen by an Advisory Working Group with lived experience of disability.

A pragmatic approach to study design

Pragmatism understands knowledge as socially constructed (Cersosimo Citation2022), recognising the need for both constructivist and positivist lenses as means (Creswell and Creswell Citation2018). This study sought to centre and amplify the knowledge of disabled people as experts in their needs. Qualitative questions in the survey and focus groups provided the freedom for participants to share the depth and breadth of their experiences without being limited by the researchers’ expectations. This approach was extended through the focus groups. For example, participants were openly asked in both the survey and focus groups what personal/identity factors in addition to their disability they felt impacted how bus drivers interacted with them. This ensured greater diversity in identifying factors impacting the reported bus travel experience, such as a person’s weight, which the researcher might not anticipate as being a significant factor, as well as capturing complex intersections of multiple factors. Quantitative questions were also included in the survey, so that diverse experiences could be reliably analysed together to identify common themes, and potentially inform recommendations. To ensure that both the survey and focus groups were relevant and accessible, an Advisory Working Group was engaged.

Lived experience led approach

An Advisory Working Group (AWG) was established and engaged to ensure the research was designed and conducted in a way that was accessible to all participants and addressed the priorities of their wider communities. This was particularly important, as whilst one of the researchers is neurodiverse, none are disabled, so cannot speak to the experience of their participants. Seven professionals working in transport accessibility or advocacy with lived experience were recruited through snowball sampling after emailing an advertisement to disability led consumer groups. Cross-disability diversity was represented in the group. The AWG met three times, as well as individually with the researcher, to review and advise the researchers on the survey and focus group form and content to optimise accessibility and relevance. Recommendations from the AWG included the language used throughout the survey and focus group questions and marketing for the same, as well as the formatting for survey questions to enable access. The AWG also reviewed and commented on the emerging results, providing insights on inclusive data sharing methods.

Study participants, instruments, procedure, and data analysis

The study participants, instruments, procedure, and data analysis are detailed below, divided into Phase 1: Survey; and Phase 2: Focus Groups.

Participants

Phase 1: Survey

To be eligible to complete the survey, a participant needed to be 18 years or older; living in Australia; have caught a bus in the last 5 years in Australia; and identified as having a disability/ies and/or health conditions impacting their bus experience, and/or they are a support person for someone meeting these criteria. Cluster and snowball sampling were undertaken with the support of: All Aboard and the National Inclusive Transport Advocacy Network (state and national based disability led consumer transport advocacy groups, respectively); AWG members; and disability led and supporting organisations, sharing the survey to their networks via email and social media. Qualtrics panels were also used to recruit additional participants to ensure there was sufficient data for analysis.

Phase 2: Focus groups

On completion of the survey, participants were provided with the researchers’ details to indicate if they wished to participate in virtual focus groups. Additional participants were obtained through the sharing of focus group information through the AWG and their wider networks, disability organisations, and social media. Consenting focus group participants completed an online or phone survey to provide their contact details; to provide their access needs and preferences for the virtual focus group; to select attendance dates; and to give their consent to participate. The inclusion criteria for the focus group was the same as for the survey.

Instruments

Phase 1: Survey

The Passenger Experience Survey was an original, mixed methods, cross-sectional survey, determined as the most suitable initial data collection method due to it being easily disseminated, low cost, and easily made accessible. The AWG assisted with both the language and the questions used in the survey. The Survey featured ten questions exploring identity factors including those related to disability (vision, hearing, mobility, sensation, etc.), age, gender, cultural identity, and location. Given the complex relationships between identity factors, and the lack of research available on bus drivers’ attitudes, an open question on intersectional factors were included so that participants could detail their unique intersectional experiences. These questions were followed by six simplified Likert Scale questions on participants’ attitudes towards bus drivers, two open questions about positive and negative bus driver experiences, and 23 scale questions regarding experiences of bus driver attitudes, behaviour, and communication methods. Specific experiences were targeted to increase the accuracy of reporting. Given the lack of research in the area of bus attitudinal accessibility, the inclusion of open questions ensured additional information outside the known scope. The survey concluded with a multi-choice question on what factors should be included in a bus driver educational program, and an opportunity to provide feedback by evaluating how easy the survey was to complete and provide any additional comments.

Phase 2: Focus groups

Focus group questions (Supplementary Appendix 2) were developed from the survey then workshopped and finalised with the AWG. The questions targeted what attitudes, behaviour, and communication methods participants had experienced from bus drivers; what personal and environmental factors they felt impacted how bus drivers engaged with them; how they defined a safe transport journey; and what recommendations they had to improve bus driver encounters.

Procedure

Phase 1: Survey

Participants were able to access the survey online, on paper, and over the phone to optimise accessibility, but only online submissions were received. A guide for support persons assisting a disabled participant in completing the survey was also included, to ensure that they were obtaining informed consent, and not speaking on behalf of a disabled participant. A plain language consent form was also included to enable informed consent. The survey was administered on both Qualtrics and Google Forms, to optimise access for participants.

Phase 2: Focus groups

Consenting focus group participants were allocated to one of three focus groups depending on their availability across three dates, and preference for person-first or identity-first language. Three virtual focus groups were run on the Zoom platform, with third-party software used for improved closed captioning for participants. One follow-up interview was completed with a participant who missed his focus group but still wanted to contribute to the research. Following the completion of the focus groups, an evaluation was sent to participants to nominate if they felt heard, and how accessible they found it. Participants were thanked via AU$60 visa card for attending, and also emailed a thematic summary of the findings for member checking.

Data analysis

Phase 1 Survey data were managed in SPSS (IBM Corp Citation2020). For the focus groups, the close captioning software produced a transcript of each virtual meeting, which was checked against the meeting recording. Qualitative analysis of both survey questions and focus group data was completed using Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) approach to reflexive thematic analysis, manually coding transcribed focus group scripts and qualitative survey questions together. One researcher coded all three focus groups (and the additional interview) and the survey, and the other two researchers coded a focus group each, to ensure coding consistency. Quantitative data from the survey were analysed using descriptive statistics as well as using Chi-Square analyses and Fisher’s Exact Test to determine any significant correlations between identity factors and the reported experience of bus drivers.

Results

Sample description

Data from 120 surveys were analysed, following the removal of 29 participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria or who did not complete more than the demographic questions. Demographic data of participants is presented in and . The age of survey participants was normally distributed, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples were represented at slightly higher rates compared to the Australian population [5.9% in study, 3.3% in Australia (ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) Citation2019)], with 85 participants identifying as disabled and 35 as support persons. Eleven people participated across the focus groups and interviews, targeting Melbourne bus drivers, which prevented comparison between regional and metro drivers, though a regional participant reported similar bus accessibility barriers when accessing Melbourne from services across the state, and a Tasmania participant also reported commonality in experience. As the frequency of catching a bus for the most part was not significantly correlated with differences in reported experience of bus drivers, this was not controlled for in the analysis.

Table 1. Demographic data of participants.

Table 2. Age.

Themes arising from surveys and focus groups

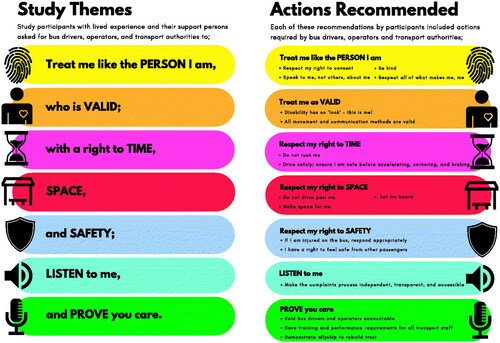

The qualitative themes identified across the survey and focus groups (and one interview, now simply termed focus group data for ease) are presented with numerical data from the surveys supporting each theme. This is to ensure participant perspectives lead to the reviewing of the quantitative data, to minimise researcher bias (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). Whilst the numerical data will be referred to throughout the results, , and , detail the frequency of survey question responses. and present a summary of relationships and statistical significance of these for between person factors and driver related questions from the survey using Chi-square analyses and Fisher’s Exact Test. Themes were taken directly from the language used by participants; for example, variations of wording around being ‘treated like an actual person’, became the theme ‘treat me like the person I am’. Quotes are presented verbatim to minimise the impact of researcher bias. First person perspective has been used for the themes and summary statement, to honour the direct, personal call to action made by some participants who wished for their desires to be made know directly to bus operators and governmental bodies. Given that the onus to push for accessibility is too often born by disabled people (Lewthwaite and James Citation2020; Kattari, Olzman, and Hanna Citation2018), the research sought to place the work to improve attitudinal accessibility at the feet of bus drivers, operators, and transport authorities. Therefore, passengers’ recommendations for change are emphasised in the themes, to evoke a ‘call to action’, and summarised later in the paper. The seven themes were summarised into one statement;

Table 3. Survey participant attitudes towards bus drivers.

Table 4. Relationships between person factors and attitudes towards drivers survey questions using Fisher’s Exact Test.

Table 5. Relationships between person factors and driver related questions from the survey using Chi-square analysis.

Table 6. Passenger experience survey participants’ recommendations for bus driver training.

‘Treat me like the person I am, who is valid, with a right to space, time, and safety; listen to me, and prove you care’.

These themes (and sub themes) are presented in and explored below. All identified themes were expressed across each of the focus groups and the survey data. Focus group participants have been numbered to indicate they represent the voices of a variety of participants. Quotes were selected that best illustrated the overall themes identified.

Treat me like the person I am

Participants reported bus drivers do not respect disabled passengers’ right to consent; unnecessarily direct questions to support workers; communicate inappropriately; and behave differently depending on a passengers’ identity factors. All three focus groups reported bus drivers do not respect passengers’ right to consent over their body, equipment, and assistance animals, one participant remarking on the danger of such behaviour;

‘There’s no handle on my chair, so they go push me in the back…if you push me in the back, you’re gonna push me straight out because I'm spinal cord, so I'm paralyzed from the chest down…Don’t push me please, just leave me alone…sometimes I say don’t push me but they just push you anyway.’ (‘Luca’, Participant 7).

Although the frequency of catching a bus for the most part was not significantly correlated with differences in the reported experience of bus drivers, it was important to note that passengers who caught the bus 5–7 times per week were nearly twice as likely to say bus drivers ‘always’ do not respect personal space compared to people catching buses once a week.

Nearly a quarter of survey participants reported bus drivers always direct questions to support persons or other passengers; a focus group participant explained she wanted bus drivers to instead ‘speak to the person’ and not the support worker as they would any passenger.

‘This is, you know, doesn’t just apply to bus drivers… speaking to the person and not just to the support worker, you know, that’s a real little things like I could go on forever about these sorts of things, but yeah, respectful, courteous attitude, I think would go a long way.’ (‘Jaime’, Participant 6).

Survey participants reported bus drivers were ‘always’ making inappropriate comments about passengers’ disabilities (43.5%), and ‘always’ interrupting (26.1%) and being patronising (17.4%) (for more examples see Supplementary Appendix 1 and ). A focus group participant explained how such comments made her feel shamed in front of other passengers;

‘They’ll just like abuse you in front of everyone on the bus about [the disability pass] …it’s made strangers on the bus turn against me…like abuse me because they think that I'm a free rider’. (‘Nadia’, Participant 4).

Survey participants were also asked to reflect on positive bus driver experiences. Participants reported nearly or all positive ‘all bus drivers I have had are nice and polite’, or nearly or all negative experiences (for example 9 survey participants responded ‘no/nah/nope’ when asked for any positive bus driver encounters). This binary experience was explored through examining the impact of identity factors on reported experience.

Both survey and focus group participants reported identity factors including age, gender, gender expression, weight, and race intersected with their disability to impact their risk of harassment. A significant relationship between gender, and bus drivers’ negative attitudes (Fisher’s Exact Test p = .004 ), and behaviour and communication () was identified in the survey. One woman mentioned direct sexual harassment from a bus driver, and harassment and abuse from other passengers. Trans and non-binary survey participants reported that when they were perceived as young women, they received better treatment than when they were seen as a member of the LGBTQIA + community, but that being perceived as women was associated with a risk of harassment. Multiple focus group participants reported observing or experiencing racism, especially mothers of disabled children;

‘Because I feel like sometimes racism…they will wish somebody good morning, you know like, but some they don’t wish to everyone.’ (‘Desiree’, Participant 10).

Another disabled passenger spoke about having to be an ally for other passengers, giving up her needed priority seat;

‘I've witnessed a lot of racism on public transport against mothers and against disabled people and disabled children…[other passengers] won’t give them a seat and there are times where I have to get up and I'm staggering around all over the fucking place like trying not to fall over and then I go to sit on the floor so that I don’t fall…. still no one will give you a seat’ (‘Nadia’, Participant 4).

A wheelchair user described being regularly and openly asked for her weight by bus drivers when boarding in front of other passengers, to ascertain if within weight clearance for bus ramp (typically 300 kg in Australia), which she described as ‘none of their business’. Focus group participants from all focus groups called for bus drivers to treat passengers ‘like they’d like to be treated’ asserting their right to ‘get onto a bus equitably. Just like everyone else’.

Treat me as valid

Participants reported that bus drivers openly question and challenge the validity of disabled passengers’ disability. A passengers’ age and equipment use (particularly if this changes due to fluctuating needs) both reportedly impacted if they were believed, and consequentially how they were treated, by bus drivers. Age group (18–34, 35–64, 65+) was significantly correlated with passengers feeling understood (p = 0.008) and heard (p = .019) by bus drivers () with 18–34 year old disabled passengers reporting less confidence in bus drivers understanding them compared to the older groups. Three focus group participants reported being abused or being denied appropriate assistance, due to not ‘looking’ disabled, particularly due to a hidden disability, their young age, or when using equipment other than a wheelchair:

‘Bus driver asked ‘do [you] have an aged card?’ and said ‘we don’t get many people like you’. Because someone who’s only 30 wouldn’t you know, we couldn’t be disabled as like a younger person.’ (‘Belle’, Participant 5).

Participants from two focus groups identified the need for bus drivers to understand that not all disabilities are visible, and particularly assert the rights of passengers with a hidden disability and young people to use whatever assistance or bus equipment they require, without commentary.

Two focus group participants described bus drivers abusing passengers for ‘faking’ when they used varied equipment depending on their fluctuating needs, sometimes denying service or assistance based on this assumption.

‘with the fluctuating my disability, some days I'm okay to use my crutches and other days I can’t walk very well or very far at all. Having to sort of prove that? I just feel like there’s a lot of discrimination’ (‘Alice’, Participant 3).

Both disabled passengers and support persons reported in focus groups that bus drivers may assume a passenger is intoxicated or dangerous due to how they communicate or move, in particular passengers who are neurodiverse;

‘Because behaviour may not be what a neurotypical person might do…So…a lot of [passengers] may be seen as difficult and sort of get a lot of discrimination’. (‘Jamie’, Participant 6).

Respect my right to time

Survey participants reported bus drivers would ‘always’ (17.4%) or ‘sometimes’ (25.2%) not wait until passengers were sitting down, or equipment or assistance animal were positioned before driving off, even when being asked to wait by the passenger. This was confirmed by all the focus groups. Many participants reported being generally rushed by bus drivers.

‘(bus driver said) “f-ing hurry up, hurry up” to my friend.’ (‘Fatima’, Participant 8).

Nearly half of survey participants reported bus drivers only ‘sometimes’ brake, corner, and accelerate appropriately. Falls and other injuries were reported in the surveys and two of the focus groups due to bus drivers’ driving, which left participants vulnerable to be thrown from their seats/position.

‘The bus driver went too fast. The first time I fell over in my wheelchair on the bus. I hit the seat…then the other time at the same corner, going back home, three days later, I fell over and I kiss the floor…I’ve had problems with my hips ever since’ (Leah, Participant 9).

Respect my right to space

Passengers reported being excluded from buses due to bus driver behaviour, such as being driven past; denied access due to their mobility equipment or assistance animal; denied bus equipment use, such as putting down the ramp or providing assistance they require; and/or denied access to priority seating. Almost a third of survey participants reported always (29.6%) being driven past whilst waiting at the bus stop. In all focus groups a participant reported being driven past, one participant reporting this was despite making eye contact with the bus drivers or lodging complaints. One participant felt passengers were resented for the space wheelchairs (in particular powered wheelchairs) take up on the bus. Another participant felt being driven past was linked to the difficulty in securing priority seating; often prams or non-disabled people were sitting there, and therefore the bus was considered ‘full’, rather than the bus driver moving along with these passengers. One participant described not being offered priority seating even when sitting on the floor of the bus to prevent falling over. Participants reported ‘always’ being denied access to a bus due to an assistance animal (34.8%), and 36.5% ‘always’ denied access because of their mobility device, despite legislation to the contrary. Focus group participants also reported being denied use of a ramp or lowering of the bus due to bus driver perception of their disability or mobility equipment; two participants reported going up bus steps on their bottom or their hands and knees due to being denied access to the lowering of the bus or ramp, despite requesting this.

Respect my right to safety

In addition to the safety issues mentioned, focus group participants reported drivers inappropriately assist passengers resulting in injuries; falls and other injuries were not being appropriately followed up on or followed up at all; and that passengers receive inappropriate behaviour from other passengers, including abuse and harassment, bus drivers taking action, or taking inappropriate action, such as yelling at passengers and escalating the situation. Participants from two focus groups identified a need for better emergency procedures in place for when people are harassing or abusing others on the bus, or for when there is a significant injury.

Listen to me, and ‘prove [you] care’

The final two themes, listen to me and prove you care, include participant recommendations targeting operators and transport authorities as well as bus drivers. Every focus group reported issues with the complaints process, including not receiving an apology or not receiving a response at all following the lodging of a complaint with an operator and/or transport authority. The process itself was reportedly inaccessible, participants with lived experience and a support worker stated that the complaint system is difficult to navigate, particularly if the passenger has an intellectual disability, another participant articulated the barriers of costs associated with escalating complaints. One focus group participant explained the need for greater accountability and allyship, calling on ‘bus drivers and the Transport Authority to ‘prove that they care about us’, another stating how they do not feel heard; ‘They’ll never really listen to disabled people. Like unless they’re actually forced to.’

The Long-Term impact of negative bus driver encounters

Participants in all focus groups shared the impact of transport anxiety following negative experiences, which meant that they had reduced or stopped bus use altogether. One participant described the impact of this on her community mobilisation;

‘I personally haven’t gotten public transport in a little while. I've now got a taxi card, just because it’s become so difficult, nearly impossible for me to get around on public transport…it’s really hard so I just tend not to use it anymore. And that’s not good, because that’s caused me a lot of social isolation’. (‘Alice’, Participant 3).

Alice’s described social isolation of having to switch to taxi services was reflected in the limitations of using a taxi card (a voucher used in Australia to discount taxi services) reported by another participant, remarking on how essential buses are for disabled people;

‘I’ve never liked buses as a rule, and I cause I had to use them…because there’s no other way getting around unless you get a taxi- too expensive’ (‘Luca’, Participant 7)

Participants 5 and 6 similarly commented on the importance of buses given their reach, and the costs associated with taxis.

Participants’ recommendations

Recommendations from the survey and focus groups included a lived experience led educational training program for transport staff, improvements to the complaint process, and a means to signal hidden disability. Participants were asked in the survey and focus groups what they would include in an educational training for bus drivers. Survey participants ranked bus drivers learning how to assist and communicate with disabled passengers as the two most important elements to include (). Ensuring that the educational training program was developed and presented by disabled people, to provide bus drivers the opportunity to understand disabled people as individuals with agency, was raised in two of the focus groups;

‘It would be great to understand…what sort of disability education…[bus drivers] have, and how many of them have actually met us with disabilities before? Because I think if they meet us, and they understand that we’re not scary…we’re actually people. Please don’t feel like you can’t engage with us and treat us like normal people.’ (‘Grace’, Participant 2)

One focus group participant recommended that this training sits within wider cultural diversity and inclusion training, and another participant recommended bus drivers have performance standards to ensure their interactions with all passengers are professional.

All focus groups identified a need for passengers with hidden disabilities to subtly signal to bus drivers and other passengers that they need assistance and/or priority seating. One participant recommended having hidden disability inclusive signage by the priority seating, and another participant recommended the use of a symbol, such as the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower on a lanyard and/or cards, a program rolled out in the UK so that passengers wishing to be approached and offered assistance can indicate as much. All focus groups reported wanting an accessible, unified, and transparent complaint system, with one participant recommending it sit independently from operators and/or the Department of Transport.

Discussion

This study examined bus driver attitudes, behaviour, and communication methods towards disabled passengers, the impact of these encounters on public bus use, and passenger recommendations to improve the attitudinal accessibility of buses. Participants reported bus drivers questioned the validity of their disability; excluded safe access; and ignored requests for assistance. Falls and other injuries requiring hospitalisation, as well as harassment and abuse, mark some of the more significant ramifications of bus driver interactions. Some participants reported having reduced or stopped bus use due to negative experiences with bus drivers. Reduced or cessation of access to the community on buses led to impacted opportunity for social interactions. Intersectional factors further placed passengers at risk of inappropriate or ineffective interactions with bus drivers. Participants asserted their right to catch the bus and feel safe and respected, asking to be treated like a valid person, with a right to time, space, and safety. Participants recommended that: their complaints to be heard through an accessible, transparent, accountable complaints system; hidden disability be better included; and that performance requirements for transport staff, particularly bus drivers, include an educational training program created and led by disabled people.

Bus driver behaviour and communication methods

The reported attitudes and behaviour of bus drivers appear consistent with the dominant cultural understanding of disability imbedded in Australian culture and indeed globally, drawing from the charity, tragedy, and medical models (Rees, Sherwood, and Shields Citation2021). The impact of these attitudes was apparent in bus drivers’ reported paternalistic behaviour, and misperceptions about disability, for example seeing their role to ‘help’ disabled passengers without ascertaining consent, and questioning the validity of passengers with hidden disabilities. The issues reported by passengers were consistent with the limited research in this area; rudeness of drivers (Stjernborg Citation2019), unsafe accelerating, cornering and braking (Risser, Iwarsson, and Ståhl Citation2012), and driving past passengers (Unsworth et al. Citation2019). Whilst other elements were not reported in the literature on bus drivers, they are found in a similar context, for example, drivers directing questions to support persons rather than the passengers themselves was reported in a study on train driver communication with disabled passengers (Bigby et al. Citation2019).

Understanding the impact of attitudinal accessibility on mobility

Being able to safely mobilise in one’s community is essential for any quality of life (Park and Chowdhury Citation2022). The current attitudinal accessibility of buses prevents mobility in the literal sense in that disabled people report they are being driven past, being denied entry, and denied the supports they need to catch the bus, stopping them from accessing the community to perform the activities they need or wish to do. The secondary way in which bus driver encounters are restricting passenger mobility is the emotional impact their behaviour and communication has on passengers. In learning to anticipate discrimination (Farrelly et al. Citation2014), disabled people may choose to not catch the bus to protect their safety. In doing so, given the inaccessibility of alternatives, disabled people are excluded from belonging to their communities, and consequentially less seen in all aspects of society.

Limitations

Key limitations identified in this study included the modest sample size; the use of self-reported data; unvalidated survey and focus group questions; and the potential for researcher bias. The limited sample size prevented quantitative comparison between certain identity factors and participants’ experience with bus drivers, resulting in qualitative analysis only. Both the survey and focus groups analysed self-reported experiences of bus driver behaviour (rather than observed), as the number of bus observations required were beyond researchers’ resources. Asking participants to target specific incidences of bus driver behaviour rather than speaking in general terms and having a requirement that participants must have caught a bus in the last five years to promote participants to report recent issues they have experienced, was used to mitigate this limitation. Researcher bias is always of concern when qualitative data are analysed. Member checking with focus groups of thematic summaries from each data collection, oversight of the project from the AWG, and having all three researchers involved in cross-coding were methods employed to reduce this risk. The AWG was limited in the number of meetings possible, and the nature of the study as part of a Ph.D., requiring a large component of the work to be completed by the primary researcher. To optimise their role, suggestions by AWG members in meetings were all minuted as actions to ensure members’ contributions were not only heard but acted upon. Future studies should include the AWG alongside a grassroots collaborative working group to further the role of disabled participants at all levels of the research. Finally, the perspectives of bus drivers were not included in this study, as a separate study exclusively surveying and interviewing bus drivers has also been conducted. The results of both studies will be applied in future research, ensuring interventions are informed by the perspectives of both passengers and drivers.

Implications for future research

The recommendations provided by participants included the introduction of bus driver educational training, complaint system reforms, standardising hidden disability signalling methods, better emergency procedures, and greater accountability generally for bus drivers. The need for bus driver training has been raised in most of the relevant literature regarding bus driver attitudes including Fast and Wild (Citation2019), Stjernborg (Citation2019), and Tillmann et al. (Citation2013). The detail in recommendations made; the inclusion of recommendations other than training; cross-disability diversity in recruitment and detailed inclusion of intersectional considerations are, however, unique to this study. The Disability Justice Framework provided a lens to review these recommendations provided by participants (Berne et al. Citation2018). Intersectionality, Cross-disability Solidarity, and Leadership of the Most Impacted are the key principles applied (Berne et al. Citation2018). As per the results of the study, participants proposed an anti-ableist educational training program for bus drivers, stating it needs to:

be Intersectional: the training program needs to address race, gender, age, and other intersectional factors as well as disability, as so much of the ableism experienced, was layered with other attitudes toward participants’ identity factors;

be in Cross-Disability Solidarity: the training program needs to be inclusive of all communities experiencing ableism in the attitudes and beliefs it addresses, teaching bus drivers the diversity in experience of their passengers to create a more inclusive bus experience for all; and

include Leadership of the Most Impacted: be led by lived experience in its development and presentation.

These principles also need to be applied in the additional recommendations of participants, for example in complaint system reforms. Further research and implementation of recommendations, including the introduction of an educational training program, should be led by disabled people, include all people who experience ableism, and consider intersectional factors.

Conclusion

It is easy to dismiss attitudinal accessibility for disabled people on buses as low priority, given other injustices faced by this community. Such a perspective fails to consider the mobility that buses represent. A Mobility Justice approach calls us to view buses as the gateway to jobs, dates, parties, and appointments, and therefore contribute to how people exercise their personhood. Therefore, without safe, accessible, inclusive bus access, disabled people are excluded from so much more than just the bus, such as belonging and participating in their communities. Applying a Disability Justice lens in this research demonstrated how reported ableist attitudes were entwined with other discriminatory beliefs. As such, proposed interventions must move beyond the disability rights mantra of ‘nothing about us without us’ to ‘nothing about us without all of us’. Interventions must challenge histories of myth and misinformation and assert disabled people not as a homogenous group, but whole persons with complex, intersecting identities, and layered experiences of injustice, including mobility injustice. The role of bus drivers must be considered in both Mobility Justice and Disability Justice literature as an example of how systems of inaccessibility can play out even in short interpersonal interactions. Individuals, such as bus drivers can become inadvertent gatekeepers for mobility. The attitudes, behaviour, and communication methods of bus drivers are therefore imperative to enabling disabled passenger mobility. Disabled passengers want to be treated like the valid people they are, with a right to time, space, and safety, and for their voices to be not just heard, but answered. Without change, ableist attitudes and systems will continue to endanger the emotional and physical well-being of disabled bus passengers.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (149.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our Advisory Working Group members listed alphabetically: John Adams, James Carter, Margherita Coppolino, Ray Jordan, Saumya Kaushik, Martin Stewart, and Geoff Trappett. Additional thanks to Kelly Clark for our Acknowledgement of Country, and to Department of Transport, Victoria, for funding and supporting this work. Final thanks to our study participants, and all the people and organisations we consulted, many of whom have advocated for so long in the accessibility and transport spaces; without their sharing of experience and knowledge, this project would not have been possible.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asplund, Kjell, Sari Wallin, and Fredrik Jonsson. 2012. “Use of Public Transport by Stroke Survivors with Persistent Disability.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 14 (4): 289–299. doi:10.1080/15017419.2011.640408.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 to 2031. 3238.0. Canberra: ABS.

- Beatson, A., A. Riedel, M. Chamorro-Koc, G. Marston, and L. Stafford. 2020. “Encouraging Young Adults with a Disability to Be Independent in Their Journey to Work: A Segmentation and Application of Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach.” Heliyon 6 (2): e03420. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.203420.

- Belcher, M. J. H., and A. O. Frank. 2004. “Survey of the Use of Transport by Recipients of a Regional Electric Indoor/Outdoor Powered (EPIOC) Wheelchair Service.” Disability and Rehabilitation 26 (10): 563–575. doi:10.1080/09638280410001684055.

- Berne, P., A. L. Morales, D. Langstaff, and Sins Invalid. 2018. “Ten Principles of Disability Justice.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 46 (1–2): 227–230. doi:10.1353/wsq.2018.0003.

- Bezyak, J. L., S. A. Sabella, and R. H. Gattis. 2017. “Public Transportation: An Investigation of Barriers for People with Disabilities.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 28 (1): 52–60. doi:10.1177/1044207317702070.

- Bigby, C., H. Johnson, R. O’Halloran, J. Douglas, D. West, and E. Bould. 2019. “Communication Access on Trains: A Qualitative Exploration of the Perspectives of Passengers with Communication Disabilities.” Disability and Rehabilitation 41 (2): 125–132. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1380721.

- Bollinger, H., and H. Cook. 2020. “After the Social Model: young Physically Disabled People, Sexuality Education and Sexual Experience.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (7): 837–852. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1639647.

- Braun, B., and V. Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

- Buning, M. E., C. A. Getchell, G. E. Bertocci, and S. G. Fitzgerald. 2007. “Riding a Bus While Seated in a Wheelchair: A Pilot Study of Attitudes and Behaviour regarding Safety Practices.” Assistive Technology 19 (4): 166–179. doi:10.1080/10400435.2007.10131874.

- Cersosimo , 2022. “Pragmatism.” In SAGE Research Methods Foundations, edited by P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J.W. Sakshaug, and R. A. Williams. SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781526421036837556.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Focum.

- Creswell, J. W., and J. D. Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Fallov, M. A., A. Jørgensen, and L. B. Knudsen. 2013. “Mobile Forms of Belonging.” Mobilities 8 (4): 467–486. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.769722.

- Farrelly, Simone, Sarah Clement, Jheanell Gabbidon, Debra Jeffery, Lisa Dockery, Francesca Lassman, Elaine Brohan, et al. 2014. “Anticipated and Experienced Discrimination Amongst People with Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Psychiatry 14 (1): 157. doi:10.1186/1471244X14157.

- Fast, D. K., and T. A. Wild. 2019. “Transporting People with Visual Impairments: Knowledge of University Campus Public Transportation Workers.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 113 (2): 156–164. doi:10.1177/0145482X19844078.

- Franklin, A., G. Brady, and L. Bradley. 2020. “The Medicalisation of Disbled Children and Young People in Child Sexual Abuse: Impacts on Prevention Identification, Response and Recovery in the United Kingdom.” Global Studies of Childhood 10 (1): 64–77. doi:10.1177/2043610619897278.

- Frederick, A., and D. Shifrer. 2019. “Race and Disability: From Analogy to Intersectionality.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 5 (2): 200–214. doi:10.1177/2332649218783480.

- Goethals, T., E. D. Schauwer, and G. V. Hove. 2015. “Weaving Intersectionality into Disability Studies Research: Inclusion, Reflexivity and anti-Essentialism.” DiGeSt Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 2: 75–94. doi:10.11116/jdivegendstud.2.1-2.0075.

- Hahn, H. 2002. “Academic Debate and Political Advocacy: The US Disability Movement.” In Disability studies today edited by C. Barnes, M. Oliver, and L. Barton. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Hitch, D., G. Pépin, and K. Stagnitti. 2014. “In the Footsteps of Wilcock, Part One: The Evolution of Doing, Being, Becoming, and Belonging.” Occupational Therapy in Health Care 28 (3): 231–246. doi:10.3109/07380577.2014.898114.

- IBM Corp. 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Jampel, C. 2018. “Intersections of Disability Justice, Racial Justice and Environmental Justice.” Environmental Sociology 4 (1): 122–135. doi:10.1080/23251042.2018.1424497.

- Kattari, S. K., M. Olzman, and M. D. Hanna. 2018. ““You Look Fine!”: Ableist Experiences by People with Invisible Disabilities.” Affilia 33 (4): 477–492. doi:10.1177/0886109918778073.

- Leigh, I. W., J. F. Andrews, and R. L. Harris. 2018. Deaf Culture: exploring Deaf Communities in the United States. San Diego: CA: Plural Publishing Inc.

- Lewthwaite, S., and A. James. 2020. “Accessible at Last?: What Do New European Digital Accessibiltiy Laws Mean for Disabled People in the UK?” Disability & Society 35 (8): 1360–1365. doi:10.1080/09687599.2020.1717446.

- Lubitow, A., J. Rainer, and S. Bassett. 2017. “Exclusion and Vulnerability on Public Transit: experiences of Transit Dependent Riders in Portland, Oregon.” Mobilities 12 (6): 924–937.

- Mitra, S. 2018. “The Human Development Model of Disability, Health and Wellbeing.” In Disability, Health and Human Development, edited by Sophie Mitra, 9–32. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Øksenholt, V. K., and J. Aarhaug. 2018. “Public Transport and People with Impairments – Exploring Non-use of Public Transport through the Case of Oslo, Norway.” Disability & Society 33 (8): 1280–1302. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1481015.

- Park, J., and S. Chowdhury. 2018. “Investigating the Barriers in a Typical Journey by Public Transport Users with Disabilities.” Journal of Transport & Health 10: 361–368. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2018.05.008.

- Park, J., and S. Chowdhury. 2022. “Towards an Enabled Journey: Barriers Encountered by Public Transport Riders with Disabilities for the Whole Journey Chain.” Transport Reviews 42 (2): 181–203. doi:10.1080/01441647.2021.1955035.

- Peck, M. D. 2010. “Barriers to Using Fixed-Route Public Transit for Older Adults.”

- Pyer, M., and F. Tucker. 2017. “With us, we, like, Physically Can’t’: Transport, Mobility and the Leisure Experiences of Teenage Wheelchair Users.” Mobilities 12 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1080/17450101.2014.970390.

- Rees, L., M. Sherwood, and N. Shields. 2021. “Tragedy or over-Achievement: A Media Analysis of Spinal Cord Injury in Australia.” Media International Australia 181 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1177/1329878X20938062.

- Risser, R., S. Iwarsson, and A. Ståhl. 2012. “How Do People with Cognitive Functional Limitations Post-Stroke Manage the Use of Buses in Local Public Transport?” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 15 (2): 111–118. doi:10.116/j.trf.2011.11.010.

- Schloemer-Jarvis, A., B. Bader, and S. A. Bohm. 2022. “The Role of Human Resource Practices for Including Persons with Disabilities in the Workforce: A Systemic Literature Review.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 33 (1): 45–98. doi:10.1080/09585192.2021.1996433.

- Sheller, M. 2018. Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. Verso.

- Stjernborg, V. 2019. “Accessibility for All in Public Transport and the Overlooked (Social) Dimension – A Case Study of Stockholm.” Sustainability 11 (18): 4902. doi:10.3390/su11184902.

- Swain, J., and S. French. 2000. “Towards an Affirmation Model of Disability.” Disability & Society 15 (4): 569–582. doi:10.1080/09687590050058189.

- Tillmann, V., M. Haveman, R. Stöppler, S. Kvas, and D. Monninger. 2013. “Public Bus Drivers and Social Inclusion: Evaluation of Their Knowledge and Attitudes towards People with Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 10 (4): 307–313. doi:10.1111/jppi.12057.

- (UPIAS) Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation 1976. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS.

- Unsworth, Carolyn A., Vijay Rawat, John Sullivan, Richard Tay, Anjum Naweed, and Prasad Gudimetla. 2019. “‘I’m Very Visible but Seldom Seen’: Consumer Choice and Use of Mobility Aids on Public Transport.” Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 14 (2): 122–132. doi:10.1080/17483107.2017.1407829.

- Velho, Raquel, Catherine Holloway, Andrew Symonds, and Brian Balmer. 2016. “The Effect of Transport Accessibility on the Social Inclusion of Wheelchair Users: A Mixed Method Analysis.” Social Inclusion 4 (3): 24–35. doi:10.17645/si.v4i3.484.

- Wilcock, A. A. 2002. “Reflections on Doing, Being and Becoming.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 46 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x.