Abstract

COVID-19 ruptured mobilities within and between cities during 2020–2022. Empty urban landscapes came to define experiences, representations, and memories of lockdowns and ensuing periods of recovery. However, empty cities provided opportunities for play and exploration in subcultures like skateboarding. Skateboarders, among other groups, took advantage of relative emptiness to access known skate spots and to discover new spots, charting new cartographies of urban landscapes in the process. Performances at these spots were captured and circulated through skateboard media, especially video. Skateboarding footage captured in empty cities acts as a radical archive of alternative mobilities during the pandemic, unsettling dominant tropes of immobility. By analyzing a preeminent skate video shot in Sydney during the pandemic, this article makes three points of argument. First, skate video archives shifting speeds and scales of mobility and immobility during the pandemic; as some mobilities halted, others accelerated. Second, confusing legal geographies, what was permitted and where, created new surveillance priorities and multiple surveillance glitches. Skateboarders took advantage and accessed patches of cities usually obstructed. Third, as cities try and regain their buzz, playful, unpredictable, and unregulated mobile performances with the power to enliven the streets deserve reconsideration, even if they defy control.

Introduction

During the height of the alpha and delta variants of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2022, empty urban landscapes characterized by human and vehicular immobilities defined the ways the pandemic was experienced and represented in visual, sonic, and social media. The contrast between urban landscapes once buzzing with affective atmospheres (Thrift Citation2004) and empty, desolate streets are stamped on collective memory (Zumthurm and Krebs Citation2022). Emptying the urban landscape, limiting human contact, and slowing down/halting mobilities were crucial tactics for combatting the pandemic globally (Brail Citation2021). Poom et al. argue that responses to the pandemic constitute ‘the biggest disruption to individual mobilities in modern times’ (Citation2020, 1). During this period urban life itself was a threat to health (and life), turning ‘quotidian bodily mobilities into a threatening endeavor’ (Holwit Citation2021, 22).

Urban recovery buoyed by vaccinations and more manageable variants have reactivated mobilities at different speeds in different places. Crucial in reactivating urban mobilities is deeper enrollment of bodies in regimes of sensory power through COVID-19 apps, vaccination data, and subsequent spatial practices (isolation, distancing, capacity limits), enabling the ‘live governing of the dynamic relation between bodies and populations’ (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 11). In some cities, most famously Shanghai, lockdowns returned in 2022. In other cities life has resumed an approximation of pre-COVID rhythms. Whereas in others, something between these extremes is emerging, patchworks of mobility at different speeds, different rhythms with limits on proximity (to others), capacity (number of bodies in a space), and temporality (time spent in a space). This was certainly true in Sydney, the focus of this article, for months between lockdowns and following the end of official lockdowns.

As I will argue in this article, declarations of the death of street life during this period overlook the lively mobilities of different groups. For certain groups, empty cities provided an opportunity for play; play that was captured, circulated, and emulated in different cities. During a period lamented by commentators and scholars as weakening the creative, somatic, and affective buzz of urban spaces (see Low and Smart Citation2020), skateboarders—among others—brought creativity to cities around the world in otherwise bleak times. When considered from another perspective, from ‘below the knees’ (Vivoni Citation2009), the empty streets were buzzing.

Despite the resumption of mobilities, empty and partially empty cities have a deep hold on the collective experience and memory of the pandemic (Adams and Kopelman Citation2022; Arnold Citation2021; Erll Citation2020). Empty cities recalled tropes from horror and disaster film, television, and literature (Reis Filho Citation2020), feeding widespread anxieties about the virus and the future of everyday life. While most cities are no longer experiencing full lockdowns, recovering pre-pandemic flows, occupancy, use of infrastructure (especially public transport, see Gkiotsalitis and Cats Citation2021; Nikolaeva et al. Citation2022), and recapturing the buzz of street life is an ongoing challenge for authorities, businesses, communities, and citizens. I will use the term ‘empty cities’ in this article to refer to periods when cities were in full lockdown and for the period of recovery during which cities operated at different speeds and capacities from one another and when compared to pre-pandemic levels, what Adey et al. (Citation2021, 1) call ‘complex intersecting systems of mobilities and moorings’. In some of these periods, cities, and Sydney in this case, were not always completely empty, but the city was certainly operating at a dramatically reduced volume of human and vehicular traffic, reduced mobilities, and with a palpable sense of alterity.

Scholars have begun to consider the increase in ‘undirected’ as opposed to ‘directed’ mobilities during the pandemic (Hook et al. Citation2021). However there has been limited attention to mobilities that mix both directed (destination-specific) or undirected (without a destination). Skateboarders took advantage of the relative emptiness to access known skate spots (directed, known) and to explore and discover new spots (undirected, found) suddenly visible and accessible with decreased human and vehicular traffic. Performances of skateboarding in cities through the pandemic were captured and circulated in skateboarding media, including social media platforms, still image, and—primarily—in video. Content analysis of skate video and other media is a common methodology used in the study of skateboarding as it is a difficult act to witness in ‘real time’, especially when preformed illegally (see Borden Citation2019; Dixon Citation2011; McDuie-Ra Citation2021b). As such, footage and images captured in empty cities during 2020 and 2021 acts as a ‘radical’ archive (Zeitlyn Citation2012) of empty cities during the pandemic; an archive that was shared globally to thousands of viewers, distinct from personal archives of empty cities (Lupton Citation2022), which, even when shared, have a more limited reach. By analyzing the visual and sonic elements of media produced for this archive, I make three additional points of argument.

First, skate video archives shifting speeds and scales of mobility during the pandemic. Within cities, foot and vehicular traffic halted, then resumed slowly, while skateboarders moved through the urban landscape at high speed, less impeded by usual crowds, security, and hostile citizens. However, the mobility of skateboarders between cities within and across international borders was curtailed during the pandemic. This had the effect of turning the skater gaze to the proximate urban landscape, discovering new spots, and reviving existing spots that had either fallen into disuse or been heavily surveilled prior to the pandemic. Rather than simply travelling to other cities to skate particular spots, skateboarders made do with exploring local spots, enrolling more and more patches of urban landscapes into city-wide skate cartographies. As the pandemic eased, more spots had been unlocked for play in cities around the world.

Second, during the pandemic, skateboarders were able to exploit shifting and confusing legal geographies—what was permitted and where—to access skate spots. The urban ‘frontstage’, spaces of spectacle for display and consumption (Mohammad and Sidaway Citation2012, 610), was relatively empty during the pandemic giving skaters access to spots otherwise difficult (if not impossible) to skate. Skateboarders were also able to disappear into the ‘city’s mundane backstage’ (Mohammad and Sidaway Citation2012, 610), accessing commercial facilities, empty campuses, and underutilized infrastructure while authorities were focused on more significant risks, especially bodies in close contact moving at slow speeds.

Third, as cities work to regain their buzz, their rhythms of street life, skateboarding should be reconsidered for the ways it enlivens public and semi-public space. Skateboarding has a powerful socializing effect, bringing people together in urban landscapes of different ages, races, and genders (McDuie-Ra Citation2022). Arguably, it makes cities safer (Flynn, Citationn.d.; Rinvolucri Citation2017), and offers spectacles of urban festivity; atmospheres of happening witnessed by chance (O’Connor Citation2020, 194–197). It can be destructive, grinding down the surfaces of the city and getting in the way of other bodies moving through space. Yet if, as many scholars argue, the pandemic affords a rethinking of urban life, urban space, and the ways different mobilities are prioritized and marginalized, then playful, unpredictable, and unregulated mobile performances with the power to enliven the streets deserve reconsideration, both within and outside designated zones.

Skateboarding media is not the only subaltern archive of empty cities during the pandemic. Empty cities enliven a range of different subcultures usually curtailed by crowds and heightened security, including graffiti and stickering, which leave a trace on the urban landscape, and parkour and urban exploration which leave a limited trace but are captured as circulated as image and video. Simpler acts that challenge rules, laws and norms during the pandemic were commonplace but rarely recorded and circulated in a systematic way, if at all, including spontaneous play in urban space, loitering and sleeping, drug and alcohol use, picnics and foraging for food (Clouse Citation2022). The movement of animals and other species in and out of urban areas suddenly operating at low human volume, the so-called ‘anthropause’, generated unique observations and moments, revealing the thickness of more-than-human life in cities and the interdependencies of different species within and between urban landscapes (see Gibbs Citation2022; Searle, Turnbull, and Lorimer Citation2021). Sanctioned use of outdoor space such as outdoor dining became more common in some cities.

Sharing the spirit of these challenges, skateboarding offers a (somewhat) unique record of lively play in empty cities during the pandemic because the bodily performances are meant to be seen not hidden. Photography and video archive these moments for audiences across time and space. In some cases, images and video clips circulated on social media almost immediately, transporting viewers to other cities in real time. In other cases, images are saved for publication in magazines, ‘zines, and books (Sharratt and Schuh Citation2021) and clips edited into longer video parts released through streaming platforms, boosting the reputation of skateboarder/s and, at the professional end, promoting various brands (Dupont Citation2020; Nichols Citation2021).

This article has five sections. The next section discusses skate spots and the impacts of the pandemic on the ways skaters view the urban landscape, skate it, and capture and circulate their performances. The section following draws on one video, Chima Ferguson’s partFootnote1 in Nice to See You for Vans footwear (Hunt Citation2021a), filmed in Sydney, Australia. Chima’s part is an exemplar of the radical archive of Sydney under lockdown and heavily reduced mobilities in 2020 and 2021. Using Nice to See You, I advance the argument of the paper through three analytical sections, the first on mobilities at changing speeds, the second on uneven law enforcement and surveillance, and the third on the hope brought by seeing empty landscapes animated on screen. The conclusion connects the radical archive to the lived experience of lockdown, and the possibilities for more creative destruction in post-pandemic landscapes.

Spots and archives

For skateboarders, the urban landscape is a playground of spots: assemblages of objects, obstacles, and surfaces full of possibilities for play (Woolley and Johns Citation2001). Spots are animated by the skater gaze, a way of looking at the urban landscape and seeing the possibilities for creativity and somatic performance from found space, otherwise mundane urban objects, discussed at length by numerous scholars (see Borden Citation2019; Chiu Citation2009; Németh Citation2006; Snyder Citation2017; Vivoni Citation2009). As Borden argues in his foundational analysis of skateboarding and urban space, drawing on a Lefebrvrian analysis, ‘practices, objects, ideas, imagination and experience’ of space-production proffers the need to ‘think about histories of spatiality through different levels of consciousness, temporalities, and periodisation, social events and actions, and spatial scales’ (Citation2001, 11). Surfaces are crucial to spots, and cities are ‘the apotheosis of surface area’ (Chambliss Citation2020, 74), attracting skateboarders to downtown areas, suburban sprawl, and connective infrastructure alike. Attention to surfaces is growing in various fields (Coleman and Oakley-Brown Citation2017). As Forsyth et al. argue, ‘[s]urfaces and interfaces can be productive, enlivening, and enchanting spaces, where diverse materialities meet to produce physical and aesthetic mixtures, fluidities, turbulence, and movement’ (Citation2013, 1017). For skaters, surface texture determines movement and whether the spot will appeal. Grinding (using the trucks [axle] of the skateboard) and sliding (using any part of the wooden deck) along surfaces are fundamental to skateboarding, producing a visual and sonic spectacle for on-lookers and a multisensory experience of movement, friction and sound for participants (Maier Citation2016; McDuie-Ra Citation2022). Surfaces are altered by grinding and sliding, and by manipulation using wax, acrylic sealants, and synthetic bonds to plug gaps, leaving behind traces identifiable to other skateboarders, mysterious to passers-by, and vexatious for property owners and authorities (Vivoni Citation2013). Surfaces are where attempts to control skateboarding play out, materialized in the skate-stopper, a now-ubiquitous object installed along the surfaces in cities around the world (McDuie-Ra and Campbell Citation2022). Skaters respond by removing skate-stoppers, lobbying for access to spots, finding new spots, and building their own (Chiu and Giamarino Citation2019; LLSB Citation2021; Kyrönviita and Wallin Citation2022). Purpose-built skateparks are also becoming more common globally (see Glenney and O’Connor Citation2019, 847). Skateparks provide much-needed spaces to skate without harassment, however an increase in skateparks is often accompanied by a resultant crackdown on skateboarding in other parts of the city (Howell Citation2008; Németh Citation2006).

Despite the proliferation of skateparks, skateboard video shot in the streets remains the most respected, and consumed, artifact of performance. From the early 1980s, skateboarding has been captured on film, video tape and digital memory cards, edited into consumable forms and circulated around the world. The format has shifted from full-length videos running for 60–90 min purchased (or pirated) as VHS cassettes and DVDs to shorter videos (20–30 min) and stand-alone video parts (3–10 min) circulated online. There are behind the scenes videos too, released as stand-alone ‘rough cuts’, extended footage with minimal editing. Rough cuts show multiple attempts at a trick, encounters with the public and security, and injuries from unsuccessful trick attempts. Most rough cuts don’t have music, capturing the sonic atmosphere of the moment. Video also has the advantage of capturing bodies in motion, and in turn the footage is circulated, and the movements of the skaters emulated by viewers. In short, skate video is in constant motion: capture, circulation, consumption, replication.

During the pandemic, surfaces of the city that were usually full of people, cars, and policed by both officials (security guards, law enforcement) and citizens, were free to skate. Volume was drained from much of the surface area at ground level, whether horizontal, angled, and vertical, leaving more ‘play space’ (Sicart Citation2018). What distinguishes skateboarding from say, football, is that while football might be played in the streets using all manner of objects and surfaces, the zenith is to play on a proper field, a proper arena, ‘game space’, whereas for skateboarding the zenith of play remains performing tricks in the streets, ‘play space’ (Sicart Citation2018, 50). COVID-19’s impact on urban landscape as play space is logged in skate video captured in 2020 and 2021. Visual and sonic analysis of skate video provides alternative footage of cities during this period, challenging images of emptiness and immobility that dominated other media. While commuting, ‘non-essential’ work and consumption was halted and/or significantly disrupted, spots across the urban landscapes became accessible, lapsing the spatial barriers between frontage and backstage, and the temporal barriers between night and day, weekend, and weekdays. By the time volume returned to cities and flows of people, vehicles and goods resumed (sometimes to halt again), new spots had been found, previously inaccessible spots had been claimed, surfaces had been shredded, and these moments were archived in skate video.

Archiving Sydney in lockdown

There were hundreds of skate videos released in 2020–2021 generating an alternative archive of street life during the pandemic.Footnote2 Videos featured on the main streaming platforms, Thrasher (US), Solo (Germany), Place (Germany), VHS (Japan), Free Skate Mag (UK/Europe), and Jenkem (US) have a wide audience, (relative) longevity, and searchability when compared to videos uploaded by individual users or single companies. I will focus analysis on one video released during this period, Chima Ferguson’s part in Nice to See You, to illustrate the ways a single city is archived during the pandemic. Chima’s part was filmed in Sydney through 2020 and 2021 during periods of full lockdown and major restrictions on mobility.

There were other videos filmed in Australian cities during COVID restrictions, including Welcome to Melbourne (Campbell 2020), Scenic (Newcastle and Melbourne, Brisdon Citation2021), and Jack O’Grady’s Pass ∼ Port Part (Campbell Citation2021a). Other skate videos filmed in empty or near-empty cities around the world were released in this period too, however as restrictions varied in different cities and some footage included in the videos may have been from before COVID-19 it is difficult to analyze with the same certainty as Chima’s part. I focus on Chima’s part in Sydney as I grew up in the city and am familiar with many of the skate spots in the video. Furthermore, as a resident of New South Wales (NSW), I lived through the same lockdown restrictions, and the contrast between Chima’s on-screen play in the empty city and the lived experience of lockdown and associated media, including dire daily COVID-19 updates by state leaders, resonates deeply. Nice to See You is easily accessible online, and readers are encouraged to access it, and other videos mentioned, and view alongside this article to appreciate the sonic and visual experience. This approach is easily replicated for researchers in other cities focusing on skate videos produced during the pandemic.

COVID-19 generated a series of responses in NSW and Sydney that can be considered strict by the standards of parts of the US and Europe, but less strict than many parts of Asia (Hong Kong, China, Japan for instance) and even other states in Australia (Victoria and Western Australia for example). Responses in Sydney ranged from strict lockdowns and careful contract tracing prior to vaccine development (early-mid 2020—52 days), a period of resumed intra-state mobility and highly restricted inter-state and global mobilities (mid-2020-mid-2021), lockdowns and live surveillance of vaccinated bodies following the Delta outbreak (mid-late 2021—107 days), a relinquishment and then revival of live surveillance with the rise of the Omicron variant (early 2022), to a self-surveillance/self-reporting model mid-2022 in conjunction with resumed interstate and overseas travel (mid-2022). Lockdowns and restrictions were implemented at varied scales, including NSW-wide, ‘Greater Sydney’, and in specific local government areas (LGAs). Attempts to impose lockdowns at the LGA level were controversial with communities in several LGAs, especially in south-western Sydney, feeling unfairly targeted by authorities for alleged breaches of lockdowns rules (Amin Citation2021). Controversial too was the definition of ‘essential workers’ and ‘essential businesses’, seen as disadvantageous to many workers who relied on travel out of their LGA for daily labour (Malone Citation2021).

Despite these variations, generally during periods of full lockdown (159 days total) schools, universities, colleges, non-essential businesses were closed, public transport was drastically reduced, visits between households limited, and interstate and overseas travel halted. Even as lockdown rules eased, schools, universities and colleges remained closed for different periods, limits on capacity inside buildings were instated, opening hours were limited, and distancing measures were in place reducing the volume of bodies and vehicles on the move in Sydney and between Sydney and other cities. The NSW Government allowed residents to exercise outdoors during the long 2021 lockdown, provided distancing measures were observed. Skateboarders took advantage of these rules to skate spots in small groups, claiming the city as playground, field, arena.

Chima Ferguson is from Sydney but has spent much of the last two decades in the US and other parts of the world as a professional skateboarder. He is sponsored by large, well-recognized skate brands, and thus his past video parts have a high standing in global skate culture. Chima’s part in Nice to See You includes footage from in the inner-city suburbs of Redfern, Surry Hills and Ultimo, the CBD, and Rhodes and Parramatta in the city’s west. Upon release, Chima’s part was a sensation globally. Based on the part Chima was in the running for the celebrated Skater of the Year prize from Thrasher Magazine in 2021.Footnote3 The video part has been viewed over 1.4 million times,Footnote4 suggesting Sydney’s empty and empty-ish landscapes were consumed by a global audience. The video as produced by Vans footwear, which has a long presence in skateboarding and sponsors skaters in different parts of the world. Vans is a large multinational company, yet skate videos are made in similar ways by large and small brands; outsourced. Filmers go out with a skater over many months, clips of successful tricks are edited into a stand-alone video part or as a section of a larger whole (D’Orazio Citation2020). There is rarely any special access or relaxed laws for skaters and filmers regardless of the profile of the company.

A brief point of clarity. Chima’s part is included in the full 45-min Nice to See You video featuring skateboarders in different parts of the world, including other cities in Australia, Canada, Japan, Russia, and the US; the whole video an archive of skateboarding in lockdown affected cities around the world (Hunt Citation2021c). Chima has the last part in the video. Usually, the last part of a skate video is reserved for the showcase skater, marking the pinnacle of the audio-visual experience. Chima’s part was also released as a stand-alone part running 6:18 through Thrasher Magazine identical to the part in the full-length of Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021b). A few months later a longer version was released as a rough cut (subtitled ‘Raw Files’) running 35:53 (Hunt Citation2021a). In this article I will refer to the Raw Files unless noted. The Raw Files shows multiple attempts at a trick over time, establishing the rhythms of the urban landscape during this period. The Raw Files are not edited to music, allowing the sonic atmosphere of landscape to be experienced by viewers. Surprisingly, at the time of writing, viewer numbers for the shorter edited version of Chima’s part and the much longer Raw Files version were similar (277k to 231k, excluding viewers for the full-length Nice to See You), suggesting a large portion of the audience is eager for the more in-depth exploration of the backstage in the Raw Files. Nice to See You highlights three main characteristics of the radical archive of empty cities during COVID-19: mobilities at changing speeds, the unevenness of surveillance, and hope for the future. These will be discussed in turn.

Speed

At a basic level skateboarding is about mobility, free mobility unbound by rules or laws; provided there are adequate surfaces, and until a human or object gets in the way. In their account of skateboarding in the school yards of Los Angeles in the 1970s, Platt argues that skateboarding is a unique and valuable form of mobility to consider, that assigns ‘new value’ from the ‘rhythmic experience with the sidewalks, curbs, steps, streets, and other physical networks’ (Citation2018, 841). Skateboarding as a culture and practice is also mobile, in that it has traveled around the world where its adherents take to it because of the sense of free mobility (see Hölsgens Citation2021; O’Connor Citation2018, Citation2020). Skateboarders are themselves mobile, and sponsored skaters travel internationally to skate in different cities, different spots, in the hopes of compiling footage for their sponsors. Within the industry, the capacity of sponsors to provide travel is an important part of the labour exchange of sponsorship. Even skateboarders without this level of support still travel, self-funded, to skate different spots domestically and internationally (O’Connor Citation2020, 163).

For many skateboarders, COVID-19 cut off regular routes of mobility and play. Closed borders, limited flights, and the difficulty gaining entry to other countries for non-citizens meant that many skateboarders accustomed to frequent travel had to stay put. Skateboarders and filmers, especially those with livelihoods bound up in the capture and circulation of footage (Nichols Citation2021), had to focus on spots near where they live. Further, in cities with famous spots usually crowded with visiting skateboarders—such as Barcelona, Berlin, Los Angeles, Milan, Melbourne, San Francisco, or Shanghai for example—local skateboarders had more access to local spots, resulting in more local footage. This led to the discovery, and/or rediscovery of spots in cities where, simultaneously, mobilities of people and goods were halted, leaving spots exposed.

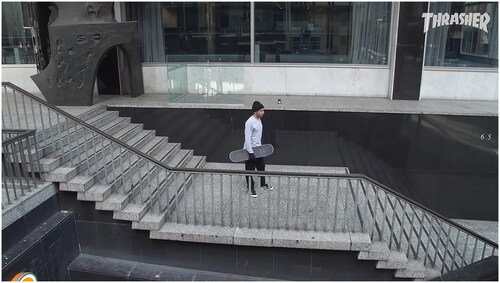

In Nice to See You, Sydney’s urban landscape is almost entirely empty. Where there is movement, it is at low volume—a few cars ambling along the roadways, a few pedestrians passing in the street. In many shots the only people that can be seen are filmers and photographers catching an alternative angle, a cluster of skaters, or lone pedestrians at the edge of the frame. In an interview following the release of Nice to See You, Chima reflects on skating during the lockdown: ‘[f]or skating, it was actually great for a while because there was limited security and basically no one on the streets’ (Ferguson in O’Neill Citation2021). Though he notes that during some periods he was limited to a five-kilometer radius from his house (as part of NSW lockdown rules), and adds, ‘…with the second lockdown and the growing restrictions, I’ve found it a little harder to get and skate spots I’d like to’. Many of the spots skated in Nice to See You that might be considered backstage would probably look the same pre-pandemic, especially if skated on weekends or after hours, including footage in schoolyards, suburban pedestrian precincts (Rhodes in Sydney’s north-west, Union square in Pyrmont), stair sets and handrails of office buildings. However, the pandemic made the backstage even more accessible in ‘regular’ hours, especially as school and office buildings were empty or operating at low capacity. What makes Chima’s part striking is the emptiness of Sydney’s frontstage spots, including Martin Place, Green Square train station, Railway Square, Circular Quay, the streets of King’s Cross, the Art Gallery of NSW, Museum of Sydney (), State Library of NSW, and Parramatta Powerhouse (museum) among others. The empty frontage contrasts with the back catalogue of skate video shot in Sydney over the years and particularly Chima’s other video parts in Since Day One (Wolfe Citation2011), Propeller (Hunt Citation2015), Spinning Away (Lovell Citation2018), From Here to There (Fulton Citation2019). In these older videos, frontstage spots feature spectators and crowds, encounters and interactions with tourists, workers, loiterers, and security. Chima vies for space amidst the flows of people at different speeds and at different times of the day and week. In Nice to See You, these crowds are absent from the same spots, the frontstage is open, time is flat, and Chima is moving through it at high speed.

Figure 1. Chima skating the front steps of the Museum of Sydney in Vans Skateboarding’s Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021a). Screenshot from Thrasher Magazine. Used with permission.

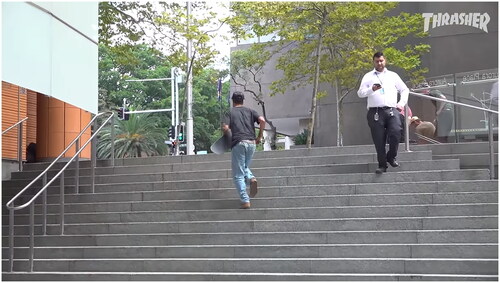

The open frontstage creates new possibilities for tricks otherwise difficult to attempt and capture, especially at landmark public buildings, the Art Gallery of NSW, the State Library, and an empty Martin Place. Chima’s final trick of the part, an ollie down the enormous 18 stair double set from the front of the Reserve Bank building at Martin Place and onto Phillips Street, seems to have been performed in the middle of the day (). There is some traffic, and other skaters are deployed to stop cars as Chima tries the trick, towed in on the back of a push-bike to gain enough speed. In the Raw Files, Martin Place echoes. There are few pedestrians around, no curious crowds watching, and snapping photos (as in Chima’s footage at Martin Place in Spinning Away for example), and no noticeable security or police presence. When Chima eventually lands the trick after a series of heavy falls, he is mobbed by the skaters and photographers who’ve gathered to witness the performance, and they almost barrel into a lone suited figure ambling along the sidewalk with earphones in, oblivious to the spectacle.

Figure 2. Chima between attempts at the Reserve Bank Building in Vans Skateboarding’s Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021a). Screenshot from Thrasher Magazine. Used with permission.

There is a further point to make about the changing speeds and flows of mobilities here. Chima’s part contains only Sydney footage because he was unable to travel anywhere else. In past video parts Chima skate’s spots in Sydney, other Australian cities, the US, and cities in Europe and Asia. During the pandemic, Chima had to make do with familiar spots near home and to explore the city for new spots where high-level skateboarding could be performed. While Nice to See You features many well-known Sydney spots, it also enrolls new spots into the skateboarder’s map of Sydney, the radical cartography of desirable surfaces.

Surveillance

In Nice to See You the lack of security and overt surveillance of spots is striking, especially at frontstage spots. Surveillance of skate spots focuses on what bodies and boards do, the somatic performance, and where they do it, the specific surfaces on which these bodies and boards perform. The actions of skaters and the surfaces upon which they perform matter in the moment, not later as abstracted or aggregated data. Therefore, surveillance of skate spots works when it happens in real time or when the time between detection and intervention is brief. Race structures surveillance of skateboarding bodies too; responses are harsher and faster when ‘blackness enters the frame’ (Browne Citation2015, 11, 162–164).Footnote5 There may be some connection to—or overlaps with—surveillance infrastructures tracking mobilities at scale, such as all city control rooms (Luque-Ayala and Marvin Citation2016), drones (Jensen Citation2016) or specific urban zones monitored by live surveillance (Caprotti Citation2019). However, such overlaps are incidental. At some spots the response to skateboarding is swift; security guards or police appear quickly, harass, detain, or pursue fleeing skaters. In other spots the response to surveillance is slower, underscoring the distance between ‘controlled space’ and the ‘control space’ (Klauser Citation2017, 132). Slow surveillance gives skaters more time to attempt complex tricks, to set up camera equipment to capture the performance, and to hang out. Surveillance at a single spot may be uneven or flow in a regular rhythm. For instance, some spots are surveilled during the day but not at night, during the week but not the weekend.

Surveillance rhythms can change over longer periods of time too; a spot might have been free of surveillance for years but following material improvements, an increase in value, a new tenant, or the targeting of damage and trespassing—among a myriad of factors—surveillance is upgraded and the response much faster. Therefore, skateboarding activates surveillance at certain spots and reveals the varied speeds of surveillance responses. And in turn, surveillance keeps skateboarders moving through the urban landscape to new spots, from spots with swift surveillance to spots with a longer lag between attention and intervention. Skateboarders are thus highly attuned to the surveillance networks at spots, their rhythms, their irregularities, their glitches (McDuie-Ra Citation2022).

COVID-19 ruptured the surveillance rhythms of skate spots in unanticipated ways creating irregularities, glitches, and absences. On the one hand, there is logical assumption that during COVID-19 surveillance of the urban landscape would be unprecedented. Isin and Ruppert (Citation2020) make a compelling argument that COVID-19 accelerated the spread of what they call ‘sensory power’, ways of governing people through ‘technologies of detecting, identifying and making people sense-able through various forms of digitized data’ (2020, 2). COVID-19 apps, data and subsequent spatial practices enable the ‘live governing of the dynamic relation between bodies and populations’ by tracking bodies infected with the virus, ‘notifying, testing, and isolating (if necessary) them’ and ‘tracing all bodies that infected bodies came into contact with, notifying, testing and isolating (if necessary) them as well’ (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 11). On the other hand, the attention of specific surveillance tools and practices were focused on particular kinds of movement during the pandemic, and skateboarding at high speed in empty space was rarely a priority. This will be discussed further below.

In Nice to See You, Chima and crew face few encounters with surveillance systems, electronic or human. In the Raw Files of Nice to See You, there is only one notable encounter with a security guard in the CBD (03:14 to 04:50). Chima skates down Bent Street rounding the corner and heads backwards towards a huge set of 12 granite stairs running alongside a tall corporate building. Chima attempts a fakie kickflipFootnote6 down the enormous drop and into the small plaza at the base of the building’s main entrance. The Raw Files show several of Chima’s attempts. This spot is in the heart of Sydney’s financial district. Neighboring buildings are emblazoned with the stalwarts of contemporary global capitalism; in fact, the spot is in view of both McKinsey and Goldman Sachs offices, under work from home orders at this time. There are no pedestrians, just a few vehicles passing in the background. The CBD is so quiet that the wind is picked up on the mics, along with whirl of Chima’s wheels, the crack of the tail end of his skateboard at the edge of the stairs, a quiet pause, and then a crash when he hits the ground in the plaza ().

Figure 3. Chima returning to his mark, security calling for reinforcements in Vans Skateboarding’s Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021a). Screenshot from Thrasher Magazine. Used with permission.

Chima’s attempts are filmed from multiple angles: there is a filmer following Chima on a skateboard, one stationed down in the plaza, and one on an adjacent glass railing and all angles are shown in the Raw Files. On the first attempt, Chima clears the stairs, but his board flies out from under his feet. After a few more attempts to get the roll up right, the camera in the plaza is blocked by a security guard. One of the filmers tracks the camera up from the security guard’s waist to his face and says, ‘what’s up?’. The security guard replies, ‘you are not allowed to skateboard here’. The filmer replies, ‘what do you mean?’. From here things fall into a familiar pattern in the liminal time between surveillance being activated and enforced at a skate spot. The skaters and filmers don’t escalate the situation nor do they leave. Chima keeps trying the trick. The security guard can be seen on the edge of the frame, pacing up and down talking on his mobile phone. On one attempt Chima hurts his ankle and is slow to get up, then hobbles. At the top of the stairs the security guard tells the filmers that ‘he’s coming there’ or something similar, the audio is hard to pick up so it’s unclear if he is suggesting that reinforcements are on the way or asking a question.

At 04:23 Chima performs the line perfectly. He begins with a frontside kickflipFootnote7 on Bent Street, rolls backward around the coroner and lofts a fakie flip down the 12 stairs and into the plaza rolling away clean. He lets out a victory cry that echoes off the empty street scape. The filmers and supporters erupt in cheers. The security guard, still without backup, stands awkwardly between his post and Chima, taking a step towards him and then one back. Chima shadow boxes the camera, calls out again in victory then turns to the security guard and says, ‘thank you!’. The security guard moves into the frame and asks, ‘all good guys?’, as if this was all part of the plan. One of the filmers says, ‘yep we’re all done.’ And someone else from off camera says to the security guard, ‘thanks mate you’re a legend!’. The security guard says, ‘thank you’ and gives a thumbs up. It’s a very tame encounter between breach and enforcement ().

Figure 4. Chima fakie flips into the empty entry plaza in Vans Skateboarding’s Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021a). Screenshot from Thrasher Magazine. Used with permission.

There are contrasts in other videos from this period. The independent skate video Diplomatic Immunity (Brini Citation2020) was shot in an eerily empty Shanghai in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak (February–March 2020). The skaters interviewed in the video, mostly expatriate Americans and Europeans, talk about having access to spots that are usually always teeming with people, but also of the eerie atmosphere of the empty city. The skate footage is certainly eerie. In contrast to empty cities in the West, the skaters in Shanghai get kicked out of almost everywhere by security guards, police, and caretakers. Other popular skate cities in East Asia generated similar footage, with enhanced surveillance a common feauture.

In the rest of the 35 minutes of Nice to See You Raw Files there are no other encounters with security guards or police. The lack of security in the CBD and at landmark buildings and plazas is surprising, especially given the raft of rules limiting mobilities in constant application and revision during this period. Similar absences are notable in Scenic (Brisdon Citation2021) and Welcome to Melbourne (Campbell Citation2021b), also filmed during the pandemic in different parts of Australia. There are several possible explanations. First, geographic unevenness. Surveillance was enforced in different parts of Sydney—and other cities—to different degrees of intensity. Sydney’s CBD and inner-suburban commercial areas featured in Nice to See You were empty through lockdowns and at reduced volume in between, especially with many people working from home and forgoing public transport. Outdoor patches of the frontstage appear, at least through the lens of skate video, a low priority. Geographic unevenness appears intentional, and stronger surveillance was widely reported and condemned in certain LGAs in Sydney based on racist calculations of where risk and disobedience were most likely. It also appears unintentional, in that not everywhere across the city could be surveilled all the time, especially with few citizens on the streets to perform proxy surveillance duties (such as call the police or alert building security). Citizens aren’t always hostile. They can be enthusiastic onlookers cheering, laughing, and marveling at the unexpected feats in front of their eyes, and these reactions and interactions are a staple in skate videos worldwide. Empty cities take those layers of texture away. Laid bare, the urban landscape is ideal for skateboarding, but less thrilling without encounters between skaters and onlookers.

Second, temporal unevenness. There were periods—weeks and months—when surveillance of the urban landscape was intensified, especially during Sydney’s first and second lockdowns and when vaccination rates were low (which in Sydney overlapped with the second lockdown). During periods in between, responsibility for surveillance fell to frontline workers in health, retail, security, and transport. These workers were focused on building access, mask wearing, social distancing, and checking vaccine status as bodies moved between and within confined spaces. What happened outside in open space was rarely a concern, especially when it happened at high speed. Mobilities were a surveillance priority during this period, yet techniques like contact tracing, for example, mapped mobilities after a COVID-19 case was reported, in contrast to real time surveillance of skateboarders at a spot. Individual bodies moving at high speed were quickly out of the frame and out of mind.

Third, somatic unevenness. Surveillance was activated depending on what bodies were doing in the urban landscape. Bodies loitering, crowding, or passing close to other bodies were a concern. Skateboarders moving at high speed and throwing themselves at, off and onto different surfaces in mostly empty spaces were not. They were far less alarming than slow moving bodies clustered in proximity in confined spaces.

Hope

When Nice to See You was released in October 2021, Chima’s part received global acclaim in the skateboard community and industry. Over a million viewers watched the empty landscape of Sydney as the arena where Chima performed staggering somatic feats. Locally, in Sydney and surrounding cities in NSW, the video generated a palpable sense of hope among skateboarders and associated subcultures. After enduring months of lockdowns, and ‘anxious immobilities’ (Zuev and Hannam Citation2021), videos like Nice to See You showed that Sydney was indeed alive, even if most people didn’t witness this liveliness in real time. Liveliness didn’t come from the resumption of essential (directed) mobilities, of dominant flows of pre-pandemic life, rather the mobilities on display in videos like Nice to See You were for play, for joy, for mischief (undirected). Empty landscapes were brought back to life, reanimated, in contrast to media footage showing emptiness, low volume mobility, quarantine spaces, false starts at ramping up mobilities, or dire graphs and tables of infection rates. There was a feeling that the long-extended present might now make way for the future (Kattago Citation2021).

A similar buzz was generated in my current home city of Newcastle, two hours north of Sydney, with the release of the Spitfire Wheels video Scenic (Brisdon Citation2021) in the same month. Scenic featured two skateboarders, Riley Pavey skating an empty Melbourne and Rowan Davis skating an empty Newcastle. Like Nice to See You, the video premiered on the Thrasher platform to global acclaim. The world premiere was held in Newcastle in October 2021, just as restrictions on outdoor gatherings were lifting, held on the lawn outside Newcastle Museum amidst one of the city’s best known skate plazas. Attended by director Izrayl Brisdon and star Rowan Davis, the premiere drew a few hundred people of all ages, pets, and even local news media. Attendees from other cities were not allowed under rules at the time. On the screen, spots in Newcastle and surrounding areas were animated by Davis’ skating, an empty church carpark, ledges and handrails around usually crowded beach pathways, handrails in the city centre, infrastructure around railways stations, empty primary schools and university campuses. Off screen in the plaza, a few hundred people shared a collective moment of wonder, in real time, for the first time in months.

Skate videos like Nice to See You and Scenic demonstrate that even in the darkest months of lockdown, the urban landscape was still alive. They remind us that somaesthetics—moving bodies through urban landscapes creating visual and sonic spectacles—are a gift; essential to urban life all over the world. These performances were muted during the pandemic, but the performers never went away completely, instead they adapted, quickly, to the empty landscapes before them (). As Young writes of cities during lockdowns, ‘[t]he emptiness of urban spaces allows us to, first, notice the absence of people or noise, and second, to notice the city itself. The withdrawal of the crowds of commuters, workers and tourists shows us streetscapes and cityscapes in a way that we have never seen before’ (Citation2021, 998). Skate video archives the city in this period, in this emptiness, by following playful acts that animate landscapes marked by absence, filling these spaces with activity and noise in ways never seen before.

Figure 5. Chima, trolleys and filmer in central Paramatta in Vans Skateboarding’s Nice to See You (Hunt Citation2021a). Screenshot from Thrasher Magazine. Used with permission.

Conclusion

COVID-19 affords radical rethinking of mobilities. As Cresswell writes, ‘[t]here is a danger that COVID-19 and reactions to it will pathologize mobility in general and ignore the various kinds of joy and opportunity that arise from the ways we move’ (2020, 61). As dominant mobilities were paused and then resumed at a lower volume, other ways of moving through the landscape, in this case for play through appropriation of spots, were more possible, more visible, and offered hope during anxious times. Following vaccines and changing variants of the virus, mobilities have resumed at various volumes and intensities the world-over. The empty landscapes enjoyed by skateboarders during the pandemic are becoming crowded, especially the frontstage. Through this pandemic, skateboarding cartographies (McDuie-Ra Citation2021a, 31–35) were overlayed with pandemic cartographies (Pase et al. Citation2021). The pandemic created an accidental golden age for skateboarders in many cities, unlocking new frontstage spots usually inaccessible and new backstage spots discovered out of necessity. And all this is archived in video, photographs, and other media forms, contrasting memories of emptiness with experiences of lively play. However, among skateboarders, the easing of restrictions creates uncertainty over future access to spots.

A wider question is whether there are long-term lessons for urban mobilities more generally as the pandemic eases? Globally cities race to brand themselves as creative and playful, seeking to commoditize urban imaginaries of vibrant street life (Grodach Citation2013). At certain times, skateboarding catches the eye of municipal authorities and the firms they hire to brand their cities as creative (Howell Citation2008; Sansi Citation2015). Yet to attract skateboarders and the cultural capital that may drift in, municipal authorities need to tolerate different uses of the urban landscape, even if these uses lead to uncontrolled appropriations of surfaces. To generate the desired buzz, it is not enough to corral skateboarding into designated spaces, such as skateparks, and crackdown on skateboarding in other parts of the city. As O’Keeffe and Jenkins (Citation2022) show in the case of Melbourne’s 2017 skateboarding plan, authorities tend to celebrate skate culture while also seeking to control the surfaces and spaces where it can happen.

In their pontifications on the near future, Florida et al write that the pandemic, ‘offers an opportunity to reinvent the way we see the city and, especially, city centres. It offers a window of opportunity where cities can reset and re-energize; where old practices can be called into question’ (Citation2021, 19). Others have explored what the pandemic might mean for the future of mobilities in the context of environmental and energy crises. Modelling future scenarios, von Schönfeld and Ferreira suggest that ‘leisure could be provided through proximity’ (Citation2022, 20). A more permissive approach to playful activities like skateboarding in the existing urban landscape might evolve from such a scenario. When scholars and planners talk about reinventing city centres, the frontstage, in this experimental period, it is unlikely they are thinking about skateboarding. However, in the rush to ‘re-energize’, it is worth paying closer attention to the energy that never went away, generated through subcultures like skateboarding. Future research into mobilities at different speeds and for different reasons is needed, including mobilites for play.

As Nice to See You demonstrates, skateboarders and other subcultures are drawn to the urban landscapes for the possibilities of play, but also for the possibilities of mobile exploration. Emptiness and the recalibration of surveillance away from high-speed mobilities towards COVID-19 risks removed obstructions to undirected mobility throughout the built environment. As dominant mobilities resume at increasing volume, these obstructions are returning. However, there is an opportunity to reconsider the laws, surveillance practices, and obstructions that interrupt playful mobilities and mute vital affective atmospheres.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank the College of Human and Social Futures at the University of Newcastle for supporting this project through the PPP scheme, Greg Hunt, Izrayl Brinsdon, and the anonymous reviewers of the article for their generous input.

Notes

1 Parts once referred to sections of a larger whole. A standard skate video might have between 5 and 15 individual parts. Each part features one skater or perhaps a montage of skaters. As stand-alone skate videos featuring one skater have become more common since the 2010s, there are fewer long videos, fewer ‘wholes’ from which to isolate a particular ‘part’. However, the descriptor ‘video part’ has stuck.

2 According to the Skate Video Site database, searchable by year, where were 214 skate videos released in 2020–2021. See https://www.skatevideosite.com/videos?year=2020%2C2021 accessed 12 October 2022. Not all videos released in the first half of 2020 were filmed during COVID. Not all videos released ruing this period are captured in this database.

3 Ultimately won by US skater Mark Suciu who released four parts in 2021 and he too benefited from empty urban landscapes in various US cities. Chima’s Nice to See You part was voted video of the year in the Australian skateboard magazine, Slam. See Slam Skateboarding (Citation2022).

4 The 1.4 million view count is current in October 2022 taken by adding views on the Thrasher YouTube channel combining views of Nice to See You as a whole video, Chima’s edited stand-alone part, the Raw Files of Chima’s part. By way of comparison with videos by companies with a similar profile, Nike SB’s Constant (Travis Citation2021) has 1.65 million views (released 4 months earlier), Supreme’s Stallion (Strobeck Citation2021) has 1.49 million views (released 5 months earlier). Videos from footwear and clothing brands average more viewers than videos from hardgoods brands, for example, hardgoods brands with high views in the same period are: Chocolate’s Bunny Hop 532k (Marello Citation2021), Palace’s Beyond the 3rd Wave 408k (Palace Skateboards Citation2021), Creature’s Gangreen 504k (Rhoades Citation2021) and Krooked Magic Art Supplies 337k (Scharff Citation2021). The big surprise from 2021 is board brand Worble’s Worble III (Mull Citation2021) with 1.4 million views.

5 Chima has Nigerian heritage (his father is Nigerian) and in interviews he has reflected on the ways race plays out for him as a skateboarder in Australia and in his years living in the United States. See O’Dell (Citation2015) from 01:00 to 04:05.

6 Fakie kickflip: traveling backwards the board flips in the air after being flicked with the toe while the skater’s body stays in the original direction of movement in the air above the board before landing back on it.

7 Frontside kickflip: the board flips in the air after being flicked with the toe while the skater’s body turns 180 degrees, and the board also turns with the skater to face the opposite direction.

References

- Adams, T., and S. Kopelman. 2022. “Remembering COVID-19: Memory, Crisis, and Social Media.” Media, Culture & Society 44 (2): 266–285. doi:10.1177/01634437211048377.

- Adey, P., K. Hannam, M. Sheller, and D. Tyfield. 2021. “Pandemic (Im) Mobilities.” Mobilities 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/17450101.2021.1872871.

- Amin, M. 2021. “Why Sydney’s COVID-19 Response Could Be a Tale of Two Cities.” ABC News [online]. Accessed 10 November 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-10/nsw-covid-19-response-is-a-tale-of-two-cities/100281710

- Arnold, E. 2021. “Mercurial Images of the COVID-19 City.” In Volume 3: Public Space and Mobility edited by Rianne van Melik, Pierre Filion, and Brian Doucet, 199–212. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Borden, I. 2001. Skateboarding, Space and the City: Architecture and Body. London: Bloomsbury.

- Borden, I. 2019. Skateboarding and the City: A Complete History. London: Bloomsbury.

- Brail, S. 2021. “Patterns Amidst the Turmoil: COVID-19 and Cities.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 48 (4): 598–603. doi:10.1177/23998083211009638.

- Brini, A., dir. 2020. “Diplomatic Immunity.” Independent/The Berrics [video file]. Accessed 20 November 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zevlzKy-mHA.

- Brisdon, I., dir. 2021. “Scenic.” Spitfire Wheels [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 18 November 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZXiLI_O4VgE

- Browne, S. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Campbell, G., dir. 2021a. “Jack O’Grady’s Pass ∼ Port Part.” Pass ∼ Port [video file]. Accessed 2 April 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mLOKobipqUo

- Campbell, G., dir. 2021b. “Welcome to Melbourne.” Nike SB [video file]. Accessed 2 February 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NS6ejKU1yhM.

- Caprotti, F. 2019. “Spaces of Visibility in the Smart City: Flagship Urban Spaces and the Smart Urban Imaginary.” Urban Studies 56 (12): 2465–2479. doi:10.1177/0042098018798597.

- Chambliss, W. 2020. “Spoofing: The Geophysics of Not Being Governed.” In Voluminous States: Sovereignty, Materiality, and the Territorial Imagination, edited by Franck Billé, 64–77. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Chiu, C. 2009. “Contestation and Conformity: Street and Park Skateboarding in New York City Public.” Space and Culture .” 12 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1177/1206331208325598.

- Chiu, C., and C. Giamarino. 2019. “Creativity, Conviviality, and Civil Society in Neoliberalizing Public Space: Changing Politics and Discourses in Skateboarder Activism from New York City to Los Angeles.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 43 (6): 462–492. doi:10.1177/0193723519842219.

- Clouse, C. 2022. “The Resurgence of Urban Foraging under COVID-19.” Landscape Research 47 (3): 285–299. doi:10.1080/01426397.2022.2047911.

- Coleman, R., and, L. Oakley-Brown. 2017. “Visualizing Surfaces, Surfacing Vision: Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society 34 (7-8): 5–27. doi:10.1177/0263276417731811.

- Cresswell, T. 2021. “Valuing Mobility in a Post COVID-19 World.” Mobilities 16 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1863550.

- D’Orazio, D. 2020. “The Skate Video Revolution: How Promotional Film Changed Skateboarding Subculture.” International Journal of Sport & Society 11 (3): 55–72.

- Dixon, D. 2011. “Getting the Make: Japanese Skateboarder Videography and the Entranced Ethnographic Lens.” Postmodern Culture 22 (1). doi:10.1353/pmc.2012.0006.

- Dupont, T. 2020. “Authentic Subcultural Identities and Social Media: American Skateboarders and Instagram.” Deviant Behavior 41 (5): 649–664. doi:10.1080/01639625.2019.1585413.

- Erll, A. 2020. “Afterword: Memory Worlds in Times of Corona.” Memory Studies 13 (5): 861–874. doi:10.1177/1750698020943014.

- Florida, R., A. Rodríguez-Pose, and M. Storper. 2021. “Cities in a Post-COVID World.” Urban Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/00420980211018072.

- Flynn, N. n.d. “Can Skateboarding Save Your City?” Huckmag x Vans. Accessed 2 May 2022. https://www.huckmag.com/shorthand_story/can-skateboarding-save-your-city/

- Forsyth, I., H. Lorimer, P. Merriman, and J. Robinson. 2013. “What Are Surfaces.?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (5): 1013–1020. doi:10.1068/a4699.

- Fulton, T., dir. 2019. “From Here to There.” Real Skateboards [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 3 January 2020. https://youtu.be/4kJy0ld0TgY

- Gibbs, L. 2022. “COVID‐19 and the Animals.” Geographical Research 60 (2): 241–250. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12529.

- Gkiotsalitis, K., and O. Cats. 2021. “Public Transport Planning Adaption under the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: Literature Review of Research Needs and Directions.” Transport Reviews 41 (3): 374–392. doi:10.1080/01441647.2020.1857886.

- Glenney, Brian, and Paul O’Connor. 2019. “Skateparks as Hybrid Elements of the City.” Journal of Urban Design 24 (6): 840–855. doi:10.1080/13574809.2019.1568189

- Grodach, C. 2013. “Cultural Economy Planning in Creative Cities: Discourse and Practice.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (5): 1747–1765. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01165.x.

- Hölsgens, S. 2021. Skateboarding in Seoul: A Sensory Ethnography. Groningen: University of Groningen Press.

- Holwit, P. 2021. “Governing Corporeal Movement in India during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Body & Society 27 (4): 81–107. doi:10.1177/1357034X211036490

- Hook, H., J. De Vos, V. Van Acker, and F. Witlox. 2021. “Does Undirected Travel Compensate for Reduced Directed Travel during Lockdown?” Transportation Letters 13 (5-6): 414–420. doi:10.1080/19427867.2021.1892935.

- Howell, O. 2008. “Skatepark as Neoliberal Playground: Urban Governance, Recreation.” Space and Culture 11 (4): 475–496. doi:10.1177/1206331208320488.

- Hunt, G., dir. 2015. “Chima Ferguson’s Propellor Raw Files.” Vans Skateboarding [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 9 July 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9uNtX5_Y2U

- Hunt, G., ed. 2021a. “Chima Ferguson’s Nice to See You Raw Files.” Vans Skateboarding [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 3 December 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ZL2poJZXE0

- Hunt, G., ed. 2021b. “Nice to See You [Chima Ferguson].” Vans Skateboarding [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 14 October 2021. https://youtu.be/J-tCWu7TY3c

- Hunt, G., ed. 2021c. “Nice to See You [Full Length].” Vans Skateboarding [video file]. Accessed 14 October 2021. https://youtu.be/A4CcloyO2mE

- Isin, E., and E. Ruppert. 2020. “The Birth of Sensory Power: How a Pandemic Made It Visible?” Big Data & Society 7 (2): 205395172096920. 2053951720969208. doi:10.1177/2053951720969208.

- Jensen, O. B. 2016. “New ‘Foucauldian Boomerangs’: drones and Urban Surveillance.” Surveillance & Society 14 (1): 20–33. doi:10.24908/ss.v14i1.5498.

- Kattago, S. 2021. “Ghostly Pasts and Postponed Futures: The Disorder of Time during the Corona Pandemic.” Memory Studies 14 (6): 1401–1413. doi:10.1177/17506980211054015.

- Klauser, F. 2017. Surveillance and Space. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- Kyrönviita, M., and A. Wallin. 2022. “Building a DIY Skatepark and Doing Politics Hands-on.” City 26 (4): 646–663. doi:10.1080/13604813.2022.2079879.

- Long Live Southbank (LLSB). 2021. Space and Why It Matters. London: Long Live Southbank. https://www.llsb.com/pdf/space-and-why-it-matters-v4.pdf.

- Lovell, R., dir. 2018. “Spinning Away.” Vans Skateboarding [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 2 January 2019. https://youtu.be/pBKJoDxUaNM

- Low, S., and A. Smart. 2020. “Thoughts about Public Space during COVID‐19 Pandemic.” City & Society 32 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/ciso.12260.

- Lupton, D. 2022. “Socio-Spatialities and Affective Atmospheres of COVID-19: A Visual Essay.” Thesis Eleven 172 (1): 36–65. doi:10.1177/07255136221133178.

- Luque-Ayala, A., and S. Marvin. 2016. “The Maintenance of Urban Circulation: An Operational Logic of Infrastructural Control.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0263775815611422.

- Maier, C. J. 2016. “The Sound of Skateboarding: Aspects of a Transcultural Anthropology of Sound.” The Senses and Society 11 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1080/17458927.2016.1162945.

- Malone, U. 2021. “Anyone Leaving Fairfield LGA to Perform Essential Work Must Be Tested for COVID-19 Every Three Days under New Rules.” ABC News [online]. Accessed 11 May 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-13/nsw-covid-19-outbreak-new-fairfield-testing-rules-explainer/100288354

- Marello, J., dir. 2021. “Bunny Hop.” Chocolate Skateboards [video file]. Accessed 30 December 2021. https://youtu.be/3_GbwLwooTg

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2021a. Skateboarding and Urban Landscapes in Asia: Endless Spots. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2021b. Skateboarding Video: Archiving the City from Below. Singapore: Springer.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2022. “Skateboarding and the Mis-Use Value of Infrastructure.” ACME.” An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (1): 49–64.

- McDuie-Ra, D., and J. Campbell. 2022. “Surface Tensions: Skate-Stoppers and the Surveillance Politics of Small Spaces.” Surveillance & Society 20 (3): 231–247. doi:10.24908/ss.v20i3.15430.

- Mohammad, R., and J. D. Sidaway. 2012. “Spectacular Urbanization Amidst Variegated Geographies of Globalization: Learning from Abu Dhabi’s Trajectory through the Lives of South Asian Men.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (3): 606–627. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01099.x.

- Mull, T., dir. 2021. “Worble III.” Worble Skateboards [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 3 June 2021. https://youtu.be/kWhyPZgiXI8

- Németh, J. 2006. “Conflict, Exclusion, Relocation: Skateboarding and Public Space.” Journal of Urban Design 11 (3): 297–318. doi:10.1080/13574800600888343.

- Nichols, L. D. 2021. “Gnarly Freelancers: Professional Skateboarders’ Labor and Social-Media Use in the Neoliberal Economy.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 45 (5): 426–446. doi:10.1177/0193723520958349.

- Nikolaeva, A., Y.-T. Lin, S. Nello-Deakin, O. Rubin, and K. Carlotta von Schönfeld. 2022. “Living without Commuting: experiences of a Less Mobile Life under COVID-19.” Mobilities : 1–20. doi:10.1080/17450101.2022.2072231.

- O’Connor, P. 2018. “Hong Kong Skateboarding and Network Capital.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 42 (6): 419–436. doi:10.1177/0193723518797040.

- O’Connor, P. 2020. Skateboarding and Religion. Cham: Palgrave.

- O’Dell, P., dir. 2015. “Epicly Later’d: Chima Ferguson.” Vice Media [video file]. Accessed 7 June 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWIglBe9jvk

- O’Keeffe, P., and L. F. Jenkins. 2022. “Keep Your Wheels off the Furniture’: The Marginalization of Street Skateboarding in the City of Melbourne’s ‘Skate Melbourne Plan.” Space and Culture. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/12063312221096015.

- O’Neill, L. 2021. “Always Nice to See Chima Ferguson.” Monster Children [online]. Accessed 30 November 2021. https://www.monsterchildren.com/always-nice-to-see-chima-ferguson/

- Palace Skateboards, dir. 2021. “Beyond the 3rd Wave.” Palace Skateboards [video file]. Accessed 20 November 2021. https://youtu.be/Jm63skCJUiw

- Pase, A., L. Lo Presti, T. Rossetto, and G. Peterle. 2021. “Pandemic Cartographies: A Conversation on Mappings, Imaginings and Emotions.” Mobilities 16 (1): 134–153. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1866319.

- Platt, L. 2018. “Rhythms of Urban Space: Skateboarding the Canyons, Plains, and Asphalt-Banked Schoolyards of Coastal Los Angeles in the 1970s.” Mobilities 13 (6): 825–843. doi:10.1080/17450101.2018.1500100.

- Poom, A., O. Järv, M. Zook, and T. Toivonen. 2020. “COVID-19 is Spatial: Ensuring That Mobile Big Data is Used for Social Good.” Big Data & Society 7 (2): 2053951720952088.

- Reis Filho, L. 2020. “No Safe Space: Zombie Film Tropes during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Space and Culture 23 (3): 253–258. doi:10.1177/1206331220938642.

- Rhoades, L., dir. 2021. “Gangreen.” Creature Skateboards [video file]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 30 December 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdYu20nVBlY

- Rinvolucri, B. 2017. “How Skaters Make Cities Safer – and the Fight to Save the Southbank Skate Spot.” The Guardian [online]. Accessed 5 June 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/aug/07/skaters-make-cities-safer-fight-save-southbank-centre-skatepark

- Sansi, R. 2015. “Public Disorder and the Politics of Aesthetics in Barcelona.” Journal of Material Culture 20 (4): 429–442. doi:10.1177/1359183515603078.

- Scharff, M. 2021. “Magic Art Supplies.” Krooked Skateboards [video files]. Thrasher Magazine. Accessed 22 April 2021. https://youtu.be/bd4co_Fiwtw

- Searle, A., J. Turnbull, and J. Lorimer. 2021. “After the Anthropause: Lockdown Lessons for More‐than‐Human Geographies.” The Geographical Journal 187 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1111/geoj.12373.

- Sharratt, N., and M. Schuh. 2021. “In the Hands of Skaters.” Portable Gray 4 (2): 398–404. doi:10.1086/717476.

- Sicart, M. 2018. Play Matters. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Slam Skateboarding. 2022. “Chima Ferguson: Video Part of the Year 2022.” Slam Skateboarding [online]. Accessed 8 March 2022. https://www.slamskateboarding.com/item/5014-chima-ferguson-video-part-of-the-year-2022.

- Snyder, G. 2017. Skateboarding LA: Inside Professional Skateboarding. New York: NYU Press.

- Strobeck, W., dir. 2021. “Stallion.” Supreme. Accessed 9 May 2021. https://youtu.be/-5bHL3pw80I

- Thrift, N. 2004. “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (1): 57–78. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x.

- Travis, A., dir. 2021. “Constant.” Nike Skateboarding [video file]. Accessed 2 July 2021. https://youtu.be/AB2kpLrXYWA.

- Vivoni, F. 2009. “Spots of Spatial Desire: Skateparks, Skateplazas, and Urban Politics.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 33 (2): 130–149. doi:10.1177/0193723509332580.

- Vivoni, F. 2013. “Waxing Ledges: Built Environments, Alternative Sustainability, and the Chicago Skateboarding Scene.” Local Environment 18 (3): 340–353. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.714761.

- von Schönfeld, K., and A. Ferreira. 2022. “Mobility Values in a Finite World: pathways beyond Austerianism?” Applied Mobilities. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/23800127.2022.2087135.

- Wolfe, D., dir. 2011. “Since Day One.” Real Skateboards [video file]. Mp4/DVD.

- Woolley, H., and R. Johns. 2001. “Skateboarding: The City as a Playground.” Journal of Urban Design 6 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1080/13574800120057845.

- Young, A. 2021. “The Limits of the City: Atmospheres of Lockdown.” The British Journal of Criminology 61 (4): 985–1004. doi:10.1093/bjc/azab001.

- Zeitlyn, D. 2012. “Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (1): 461–480. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721.

- Zuev, D., and K. Hannam. 2021. “Anxious Immobilities: An Ethnography of Coping with Contagion (Covid-19) in Macau.” Mobilities 16 (1): 35–50. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1827361.

- Zumthurm, T., and S. Krebs. 2022. “Collecting Middle-Class Memories? The Pandemic, Technology, and Crowdsourced Archives.” Technology and Culture 63 (2): 483–493. doi:10.1353/tech.2022.0059.