Abstract

Oil is linked to mobilities both as a substance that fuels movement and as a resource that is highly sought by mobility performances. Crude oil pipelines are not just physical and technological constituents of the commodity’s value chain, they are geometries of power that determine not just the manner and direction of the resource’s movement but also what other socio-material elements become (im)mobilized in the process of their making. In this paper, we examine the practice of governing (im)mobilities in the early stages of the process of establishing Uganda’s East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). We particularly interrogate the creation of the pipeline’s path—known as Right-of-Way (ROW)—as a process of making oil movement possible from Uganda to the international market via the port of Tanga in Tanzania. With the Right-of-Way as an empirical example, we revisit the concept of ‘governmobility’ by posing practical questions that we believe bring new insights into the practice, the art and the underlying rationale of governing (im)mobilities.

Introduction

Crude oil pipelines across different parts of the world have long been the subject of empirical research with much focus on their geopolitical configurations (Olanipekun and Alola Citation2020; Verma Citation2007; Bahgat Citation2002). In much of the literature, the understanding of crude oil (and gas) pipelines is one that often takes the perspective of ‘critical infrastructures’ (Murray and Grubesic Citation2007) in which case, the infrastructures appeal as spaces of energy security. There is no doubt that pipelines are physical manifestations of interconnections and geometries of power which, as pointed out by Murray and Grubesic (Citation2007, 1), encapsulate a broad range of socio-economic and political issues collectively conceivable as ‘material politics’ (Barry Citation2013).

This paper is an attempt to craft a new trajectory of the pipeline debate by viewing such infrastructures as physical geometries of power through which practices, standards, rationalities and the art of governing (im)mobilities manifest. However, these are not only evident when such infrastructures are in existence but also when they are mere visions, concepts and processes, such as in the case of Uganda’s East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) project.

The process of building the EACOP gained momentum in 2017 when the governments of Uganda and Tanzania signed an intergovernmental agreement that defines its transboundary course. By examining the rearrangement of socio-economic and socio-cultural configurations along and around the geocoded path of the planned pipeline project, we explore not just how its Right-of-Way (ROW) is produced and governed; but also what exactly inspires the rendering of the process into particular frameworks of governmental power. To do this in a more informative way, we not only conceptualize and problematize the concept of Right-of-Way—which itself is literally imbued with certain mobility relations—we also view its creation as a form of governing (im)mobilities thereby expanding Baerenholdt’s (Citation2013) concept of governmobility.

The empirical examples we offer at a later stage bring us to the understanding that the encounter between Right-of-Way and what we call Right-of-Place is enabled by particular sets of materialities, visions and expectations. These are pegged not just to the impending movement of oil but also to the (im)mobilities that are bound to take place around the pipeline infrastructure. It is on the basis of these materialities, visions, and expectations that we argue that relations of power are seen to perform the act of encouraging, discouraging, reconfiguring, restraining or blocking certain (im)mobility practices.

As Jensen (Citation2011, 267) points out, mobility practices are not only about being (placed) on the move but also about the role of governmental power in ‘producing and moulding perceptions, imaginaries and experiences’ of the mobile and the immobile. Building on the intersection between governmental power and mobilities, Baerenholdt (Citation2013) has deployed the concept of ‘governmobility’ to deepen the understanding of how power comes to bear on mobilities, by itself being mobile.

This paper revisits this concept by posing a practical question: what exactly does one govern when they are said to govern (by) mobilities? Posed more elaborately, what influences the decision of authorities to produce and mould perceptions and experiences of or around mobile and immobile constituents? With this question, we move a step away from attempting simply to understand how technologies of power are brought to bear on the mobile and the immobile, to deepening insights into what exactly drives the particular functionalities of such technologies of power.

To rise to this task, we begin by viewing the moulding of perceptions around, and the production of concrete spaces of, movement and/or stasis, as part of what Foucault (Citation1991) frames as the ‘conduct of conduct’: a short definition of government(ality) (see also: Dean Citation1999; Lemke Citation2015; Hannah Citation2017; among others). In practice, mobilities are multidimensional forms of conduct that, as Merriman (Citation2016, 556) suggests, are profoundly embedded with underlying governable ‘elemental logics’. To develop a clear grasp of these logics, it is an imperative to go beyond trying to explore the government of practices of (im)mobilities themselves, towards the socio-material, political and environmental drivers and configurations that are not always explicit.

We recall, in general terms, Foucault’s (Citation1991, Citation2007) idea that government has much to do with the appropriation of things. These things, as we later expound, are complex assortment of realities of everyday life of a given population around which socio-cultural, economic and political behaviours are regulated. Therefore, examining the materialities and materialization of (im)mobilities such as the creation of the Right-of-Way in the context of Uganda’s crude oil pipeline offers the possibility to concretize what governing (im)mobilities is predominantly about. This lays the empirical foundation of the central argument that we make in this paper, moulded around the effort of making oil’s movement effectively possible.

We argue that the making of the Right-of-Way for Uganda’s crude oil infrastructure is a space-production process of technical/technological, physical and socio-material significance. In this process, the very act of governing mobilities manifests in concrete terms, as being shaped by an array of concrete things, visions, standards, and practices. Of great significance are things such as oil, land, crops, machines, money and their association to competing mobility visions and narratives—i.e. speed, comfort and wealth-producing interconnections, on the one hand; and real practices and/or imagined possibilities of marginalization, deprivation, and containment, on the other.

With this empirical case study, we seek to carve out the socio-material elements of the entanglements between the Ugandan state and the affected communities in the process of territorializing the performance of (im)mobilities. This adds new evidential dimensions to a more general corpus of knowledge about governing mobility, which builds on Bærenholdt’s (Citation2013) concept of governmobility; going beyond the act of governing (through) mobility, to concrete objects to which the power of government comes to bear on.

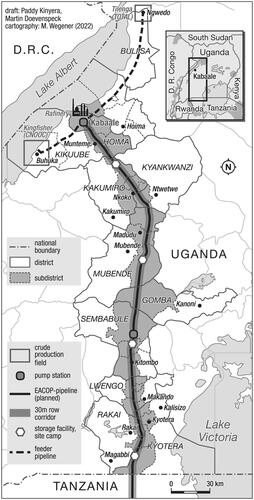

Our field study entailed a mixture of different methods, pursued in a mobile ethnography (D’Andrea, Ciolfi, and Gray Citation2011, 152)—giving accounts of how the Right-of-Way is being negotiated across different locations (see ). Across these locations (in southern districts of Lwengo, Rakai and Kyotera), we conducted 42 qualitative interviews, held numerous informal conversations and observed stakeholder interactions at meetings, where we took stock of the crucial socio-material talking points around the ROW-making process. In addition, we got deeper insights into the institutional problematization of the ROW-making by analysing policy papers, statutory instruments, property claim forms, compensation valuation and declaration forms for some of the individuals affected by the pipeline’s ROW, among others. To capture the general picture of community perceptions about the coming of the pipeline, we administered a total of 120 questionnaires among the affected communities, posing general questions about their interaction with the process, in relation to their everyday realities.

As a general overview, we came to the realization that the wave of anxieties associated with the EACOP’s ROW is not entirely about the planned movement of oil from Hoima in Western Uganda to Port Tanga in Tanzania through a pipeline, but the multiple and contextually unique forms of (un)desirable movements for which the ROW paves the way. These include the (de)mobilization of people and their property by way of changing the patterns of performance of everyday micro-mobilities through, for instance, displacements and relocations, among others. The pipeline—in its imagined and narrative forms—appeals as a new geography of anticipations and uncertainties (Witte Citation2018) about the future of Uganda’s emerging oilscape. To put the ROW-making process in context, it is a structural imperative to offer a brief overview of Uganda’s oil complex.

Uganda’s oil infrastructure and mobilities

Over a decade ago, Roberts (Citation2004) indicated that the oil industry had continued to consolidate its position in the global political economy as the currency for political transactions which hegemonized and hierarchized nations on the basis of oil-driven material advancements. Despite the call for countries to develop alternative sources of energy at different global climate change forums, such calls may take decades to have a game-changing effect on what Watts (Citation2012, 439) calls oil’s ‘Olympian power’.

As new oil fields continue to emerge, such as in Uganda, oil’s power keeps manifesting in contentions, visions, anticipations and expectations at various levels. Oil remains a powerful currency for global energy (re)configuration, evident with the recent energy crisis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a war that incentivized massive gains for oil corporations such as Shell and BP in 2022. In Uganda, the vision of oil futures—although under threat from intense campaigns by environment activists—has become the vortex for expectations and development practices that are seen to be driving the country’s socio-economic and socio-spatial reconfiguration over the years (Kinyera Citation2020). For communities in the oil-bearing districts such as Hoima and Buliisa, and recently, those communities in whose areas the country’s crude oil pipeline will pass, anxieties continue to grow day by day, driven by their interaction with different infrastructural facets of the country’s orientation towards a future oil economy.

Uganda’s crude deposits are estimated to have a recoverable potential ranging between 1.4 and 1.6 billion barrels, depending on the deployed extractive technology. If the often talked about peak production of 200,000 barrels per day is arrived at quickly and maintained, the lifespan of the country’s oil is estimated to be just over 2 decades. Respective of volatilities of crude oil prices, a fully operational oil industry in Uganda is anticipated to inject at least USD 15 billion into the country’s economy. With these figures in mind, the ongoing pre-production activities—which have attracted different forms of oil narratives, institutional and corporate strategies, and socio-economic pulses—demonstrate how Uganda navigates its way into the future as a net oil producer (Kinyera and Doevenspeck Citation2019; Witte Citation2018; Hickey et al. Citation2015).

As the vision for first oil continues to hover in the unforeseeable future, the hope that oil could push Uganda to the next level of development continues to be the most desirable narrative by the state against the pessimism that particularly questions the country’s structural, politico-moral and infrastructural preparedness for oil (Olanya Citation2012; Mbabazi Citation2013; Gwayaka Citation2014). However, the risks associated with poorly planned domestic foundations for oil extraction have often been overshadowed by impressive economic visions and imaginations. At the signing of the final investment decision (FID) for three projects including the EACOP-project on 1 February 2022, for instance, Proscovia Nabbanja, the CEO of Uganda National Oil Company, indicated that the country’s entanglement in the oil business will return ten times more on every dollar invested (see Atuhaire Citation2022).

As the wait for ‘real’ oil goes on, the visions and expectations that are mediated by the development of mega infrastructures such as, in this case, the pipeline project continue to change in shape and complexion across space and time. The crude oil pipeline is not just the most important, single largest (USD 3.6 billion) investment project in Uganda’s oil. It is also the most contentious infrastructure that could be the turning point in the country’s over-a-decade-long endeavour to transform into a ‘Petro-state’ (Kinyera Citation2020). The most crucial aspect of the pipeline has been the search for its passage—commonly known as the Right-of-Way (ROW)—a prerequisite for the country to materialize the mobility of its oil.

There is an explicit mobilities dimension in the pipeline project, both in terms of visions of the future and politics of the time. Evidently, not only does the ROW define the path of the pipeline, it also defines how other constituents move in, along with, as well as around it. This includes the technologies, expertise, policies, materials, the narratives, people, practices and standards, among others, that are likely to move in the process of materializing the crude oil pipeline. It is the configuration of these adjunctive pre-pipeline mobilities that draw our attention to the materialities of the ROW. The forthcoming conceptualisation demonstrates why we believe the ROW is a good example for extending the strands of the concept of governmobility later in the third section.

The concept of ROW and why its making matters

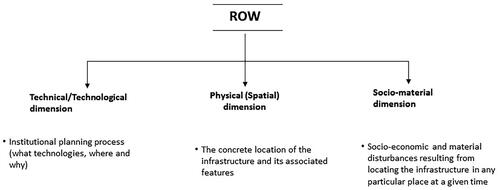

The term Right-of-Way (ROW) is by no means new. Academic and policy papers that make reference to this term give the impression that it is obvious, hence often used in-passing (Jayawardena Citation2011; Synergia Citation2016). As we shall endeavour to show in this section, ROW is an action-packed term, characterized by contextually unique relations of different dimensions of power. Technically, ROW, in its conventional sense, is associated with the practice of easement—a process of one’s ‘conveyance of certain property rights to another individual or entity’ (Šnajberg Citation2015, 421). This process is built around careful politico-technical, technological, logistical and economic considerations that are often brought to bear on contextually unique subaltern socio-material organisation. The schema below summarizes our a tri-dimensional conceptualisation of ROW ().

As is explicit in the above illustration, ROW is a space that is rationalized, produced and materialized by technologies of governmental power, and other forms of power (technical, logistical, financial) to shape and reshape discrete practices of mobile and immobile constituents. It is a complex entity that is embedded with particular expressions of power of/over (im)mobilities—the power to prioritize, allow and/or restrain the movement of things of competing significance.

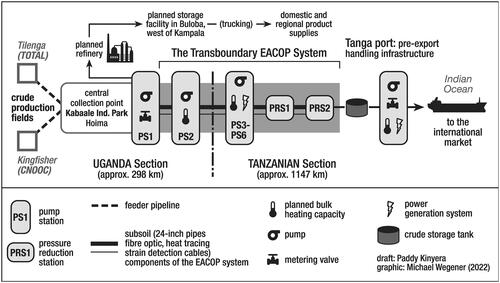

As a terminology, Right-of-Way itself depicts certain mobility relations: one thing having priority of movement over another. In the case of the EACOP-ROW, the planned prioritisation of the movement of oil from Uganda’s western district of Hoima to Tanga in Tanzania is operationalized by an exclusive right-of-access to an extensive space stretching across approximately 1445 kilometres to be occupied by crude oil pipeline and its associated features. Evidently, the invocation of this right and priority of oil’s movement produces different forms of (im)mobilities which include, among other things, the evident restraint to, and reconfiguration of, pre-existing subaltern practices and socio-economic process of production in and around the areas in question.

In the context of critical infrastructure projects such as onshore oil and gas pipelines, the enforcement of injunctions on communities to accept project-induced socio-economic displacements and/or involuntary resettlements are general features of the ROW-making process. Therefore, the process renders visible instances in which governmental power is seen to be producing, shaping and governing (im)mobilities. What this means exactly is a conceptual dilemma that has compelled us to revisit the concept of governmobility (Bærenholdt Citation2013).

Theoretical approach: Governmobility

Mobilities in the twenty-first century are of such significance as they express not just the global order but also its modernity (Cresswell Citation2006, 15). At the same time, mobility is one of the most fragile practices of this modernity on various fronts, arguably making it the most governed element. This understanding evidently became prominent in the mid-2000s with the conceptualization of the idea of a ‘mobility turn’ (Hannam, Sheller, and Urry Citation2006). Since then the mobilities debate has focused both on a wide range of topics ranging from empirical approaches of studying mobilities (Büscher and Urry Citation2009; D’Andrea, Ciolfi, and Gray Citation2011; Manderscheid Citation2014) to those perspectives that feature issues around mobility-politics—particularly the power framework and practices of governing mobilities (Bærenholdt Citation2013; Sheller Citation2016; Jensen Citation2011).

As a reiteration, the concept of mobility alludes to the ‘actual and potential movement of people, goods, ideas, images and information from place to place’ (Jensen Citation2011). Without doubt, these actuals and potentials of movements are shaped by relations of power (Bærenholdt Citation2013, 21, citing Cresswell Citation2006) which are held in multiple forms and are functionalized in different ways in different spatiotemporal contexts. This theoretically explains the unevenness of distribution of and access to mobilities (Sheller Citation2016), bringing about critical perspectives such as the question of mobility justice (Sheller Citation2018).

The idea that mobility’s unevenness results from the practice of power that (re)organizes the social around different nodes of interconnection (Hannam, Sheller, and Urry Citation2006, 12) begs a series of governmobility questions. These questions should go beyond the configuration of mobile frameworks of power that govern mobile constituents, to exploring what exactly one governs in governing mobilities: Is it the people, their ideas, their practices, or is it their visions? Is governing mobilities about the infrastructure and its components? Responding to these questions requires unpacking, first of all, the very idea of government: what is government?

Our view of government draws on a Foucault’s idea summarized as the ‘conduct of conduct, aiming to effect the actions of individuals by working on their conducts’ – that is, on the ways in which they regulate their own behaviour (Hindess Citation1996, 97). Distilled further, the conducting of conducts has, as its primary foci, the right disposition of what is collectively known as ‘things’ (Dean Citation1999; Lemke Citation2015; Foucault Citation2007); and the responsibilization of human actions on the basis of these things (Hannah Citation2017; Lemm and Vatter Citation2015). In terms of mobilities, therefore, we can hypothetically state that governmobility is about the ordering of (im)mobility practices to achieve a sense of responsibility around the discursive array of things. Understanding what these things are, is an imperative. According to Foucault (Citation2007, 97), things are:

…[people] in their relationships, bonds and complex involvements with things like wealth, resources, means of subsistence, and of course, the territory with its borders, qualities, climate, dryness, fertility and so on. ‘Things’ are [people] in their relationship with things like customs, habits, ways of acting and thinking. Finally, they are [people] in their relationships with things like accidents, misfortunes, gamine, epidemics and death.

Indicatively, the things that matter to government at the moment constitute more than just technical and technological materiality of the pipeline: they also constitute the population’s socio-material encounter with the ROW-making process, and their orientation to the narratives about the material benefits of the pipeline. Here, it is not just the strategic (im)mobility calculus and injunctions of state institutions that are at play. There are also the aspirations and imaginations of surrounding oil movements, encompassing narratives of potential material benefits, and impending risks. The two empirical case studies that we present in what follows indicate how the affected communities interpreted the ROW-making process in terms of their own socio-material realities.

ROW-making in Southern Uganda

The ROW-making process in Uganda started with the identification and mapping of the districts, sub-counties and villages and then the point coding of the exact locations where these features would be established. Within Uganda, the pipeline is planned to run between Hoima and Kyotera, a distance of 296 km, cutting through 11 districts and 172 villages (Government of Uganda Citationn.d., 5). The initial scoping activities covered a width of up to 100 meters. This was later reduced to 30 meters, pegged to specific geo-coded locations published in the government’s ‘Statutory Instrument No. 105’ (Government of Uganda Citation2019).

The EACOP Environment Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) report indicates that an estimated half-a-million tonnes of equipment and materials will be imported into the country to facilitate the construction of the 1443 km crude oil pipeline. The infrastructure is planned to come along with visible above-ground installations: 2 pump-stations (within Uganda), a mainline block valve and electrical heat-tracing substations (Government of Uganda Citationn.d.). These are nodal points for regulating the flow of oil. Other nodes include construction camps which will also double as pipe yards to be linked to the geocoded pipeline traction by a network of planned and existing access roads (see ).

From this overview, the Right-of-Way is an emerging space for the operationalisation of mobilities that can be expressed in three dimensions. First, it is a technical and technological space, being created by institutions of the Ugandan government, in close cooperation with corporate agencies such as Total Energies, China National Offshore Oil Corporation and NEWPLAN, among others. Second, the ROW is also a physical space, the making of which resulted from the consorted activities of the above agencies, built around specific geological, environmental, and socio-technical knowledge systems. Third, the Right-of-Way is space where real and imagined encounters of oil’s movement with the communities living along its mapped path. It is this third aspect that gives the ROW-making process its discrete socio-material dimension—i.e. the concrete material effects on future pipeline-riparian communities.

What follows are empirical accounts of the concrete realization of ROW—the encounter between institutional technologies of power and the socio-material realities of the riparian communities in Lwengo, Rakai and Kyotera. With these examples, we attempt to answer the question: what does one govern when they are said to be governing (im)mobilities? As this has had the effect of destabilising subaltern micro-movements and stasis of the local communities, the institutional process of its making points us to the material dimension of governing mobilities.

Infrastructuring Oil movement

The ROW-making process in Uganda is part of the process of infrastructuring oil movement that has resulted in injunctions to displace an estimated 4000 people together with their belongings such as houses, animals, gardens; and socio-cultural materials such as shrines and graves, among others. Asked what he thinks about the stories about the oil pipeline that are going around in his village, a local leader from Lwengo answered:

… we never knew that this oil story would reach us. We heard about this in places like Hoima… I have never been to Hoima, so I could not relate. Until these pipeline people came here asking questions about land, then we knew it was serious. That is when they told us that they are looking for where to pass the oil pipeline. I trembled in my heart because I did not know what to say… After some time, we started receiving many visitors … some were even going to Rakai. Then we started receiving other information about how the government will take away our land if we allowed this pipeline to pass here. As a leader, I was first of all, confused. I did not know how to guide my community… Then eventually, the truth came out that part of our land will be taken. I think it will disorganize us. It will disorganize how people in our community go about their daily business… Honestly, I am not really sure if I should worry or not. The government is saying this pipeline will bring us rewards in the future. That we shall profit from it, but there is another group of NGOs who also tell us that the pipeline will cause damage to our surrounding. So I don’t know who to believe. If you don’t have clear information, you have every reason to be worried.Footnote1

The journey to construct what is likely to be the world’s longest electrically-heated crude oil pipeline commenced with the government of Uganda together with the lead project developer TotalEnergies contracting and deploying a survey team from NEWPLAN to map and define the pipeline’s ROW. The team, which became known by the communities as ‘the EACOP people’ was made up of engineers, geologists, environmentalists and sociologists, escorted by security personnel. With the movements of this team, encounters with oil––particularly the associated narratives––moved the frontiers of expectations, benefits and risks beyond the planned production fields in and around the Albertine Graben districts of Hoima and Buliisa, to communities across the country’s rural south.

Most pronounced in these narratives are the economic opportunities linked to the pipeline, on the one hand; and the threats of temporary and permanent loss of land and means of livelihood, on the other. The ESIA report for the EACOP that was finalized in February 2020 particularly highlights the negative impacts of the project on land (access and use)—the primary source of livelihood for the affected communities. In the imaginations of an oil future, land issues are among the most sensitive axes of mobility relations: dynamic relations that go beyond human actors to wild animals (Kinyera and Doevenspeck Citation2019).

This sensitivity is not unfounded. Land is a significant component of mobility performances (Dargay and Hanly Citation2004; Breusers Citation2001). This is not just in the way of providing passages for mobile constituents but also as a point of the often neglected micro-movements through which rural and predominantly agrarian communities realize their livelihoods. In the context of the ROW-making process in Uganda, land is the very point of contact where the pipeline is seen to compete with what we frame as Right-of-Place. Right-of-Place on a specific area of land is the foundation for the performance of productive micro-mobilities.

In 2016, the so-called Joint Venture Partners in the development of Uganda’s oil industry—i.e. TotalEnergies (formerly Total E&P), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and Tullow Oil—alongside the government developed a policy guide for the transfer of land ownership and use rights to the government. The key aim of the new ‘Land Acquisition and Resettlement Framework’ (LARF; hereafter, the Framework) is to standardize modalities of land acquisition and resettlement planning (CNOOC, Total, and Tullow Citation2016). The Framework was not only meant to ensure consistency with existing national laws, but also to align local land acquisition practices with international Performance Standard 5 (PS5) of the International Financial Corporation (IFC)—a subsidiary of the World Bank. LARF is depicted as an ‘overarching policy framework’ for

…[standardising] the way in which land acquisition and resettlement planning is conducted across the project areas [in ways that] ensure a consistent approach in line with the laws of Uganda as well as the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC’s) Performance Standards (PS), particularly PS5 on Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement (2016, 4).

According to the Framework, land acquisition in the context of oil activities is a process that involves project operators acquiring rights over land from private owners on behalf of the government, and then transferring these rights to the government. The Framework is an elaborate document that anchors its policy logic not just on existing legal regimes of land governance but also on corporate policies and international standards of involuntary mobilization of people (2016, 6). However, the Framework is a tool of hierarchisation of (im)mobility injunctions. This is evident with its proposal to call on the inter-ministerial Resettlement Advisory Committee (RAC)—that was established in 2015 by a joint effort of the Uganda government and the oil corporations—to guide the process of land acquisition.

The services of the committee are sought when resettlement of communities and individuals are inevitable and potentially contentious. The complexion of this unit of power produces what one might call governmental relations of domination (Hindess Citation1996) in the process of land acquisition. LARF is an institutional tool of power that produces as well as renders governable subaltern project-induced (im)mobilities. However, private land owners whose tenure rights become the subject of discussions by the RAC are not represented at that level. Potentially aware of this, the Framework guides that community level representation through local committees can only be created and incorporated into the land acquisition agenda at a later stage: i.e. when the resettlement plan starts (2016, 14).

The significance of this power structure lies with contentious relations that it produces once it begins, as a top-level state organ, to extend its powers to a population that is not adequately informed about potential displacements. The ROW-making process offers a clear example of this. In what follows, we explore two aspects of this process that highlight the significance of producing (im)mobilities.

The first one is an account of the entry of forces of state-corporate alliance into the spaces of everyday mobility practices of local communities in southern Uganda. While this entry signalled impending flow of oil, it had the effect of destabilizing ontological socio-material mobility performances that have been the feature of the communities’ routines. The second example is what one might call commodification of risks associated with (im)mobility injunctions. Here, the value and valuability of things in the context of the ROW-making process proved to be the difference between local aspirations and the impending forces of change brought about by ‘strangers’ who intend to create spaces for moving oil.

In an informal conversations in southern Uganda, we met Rukia, a 47 year old so-called Project Affected Person (PAP) from Rakai district. Rukia narrated her first, somewhat frightening, encounter with ROW-making activities, recalling how strangers silently moved around her village, going through, and marking parts of their land:

About two and a half years ago, we first heard that oil was coming. We were not aware which areas [the oil] was going to pass… but we had started seeing different people going through our villages. Then, we started seeing men passing through our homes, gardens without saying a word… yes… they just made way through our gardens, destroying our crops with their heavy boots without saying a word… not even ordinary greeting. We became scared and disorganized… Later, the area chairpersons talked to us and assured us that these people meant no harm. We later got solid information when they started marking the areas with sign posts that showed exactly where the pipeline was going to pass. They took measurements to find the width but as they did that, the only thing they said was ‘What is your name…’ which they recorded… and then they went on.Footnote2

In the middle of our conversation with Rukia, 63 year-old Benna weighed in. She explained how she had just been informed that her land in Kamuli village lies within the ROW. She is the owner of a banana plantation that would be destroyed to make way for the pipeline project. Even when the pipeline surveyors went through her plantation, ‘…they hardly said anything, apart from asking for my name’.Footnote3 In the villages of Lwengo district and in other parts of the so-called greater Masaka area, communities also wondered why there is no information that oil is coming soon and how.

The local council chairperson of a village in Lwengo attempted to draw connections between the immobility of information about oil and micro-mobility practices on which the livelihoods of communities depend. In his view, not only did a widespread lack of information create spaces for the flow of misinformation that consequently brought different micro-mobility-dependent aspects of the local economy to what he described as a ‘standstill’; it also sent waves of speculation and multiple ideas about how his community can align itself to profit from oil-related activities. A case pointed out by the chairperson was the halting of commercial tree growing when unclear information about the pipeline’s Right-of-Way reached the communities:

…people were worried because they were not informed about anything. So their economy was at a standstill. We have people who specialize in commercial tree growing—eucalyptus mainly; and we have people who grow coffee. These are land-based businesses that require time and patience to establish. All of a sudden, you are beginning to think of moving away and setting it up somewhere else because of the pipeline.Footnote4

The fundamental concern here should be about the rationale for regulating flow of information on the pipeline’s Right-of-Way. From a largely governmental point of view, this instance of disinformation is part of the commonplace ‘culture of silence’ associated with oil-related operations (Beamish Citation2000). In countries with debateable transparency standards in the extractive sector, the tendency to render oil-related developments confidential, and the public’s relentless efforts to get to know what is happening, are the industry’s two competing operational dynamics (Basedau and Lacher Citation2006; Welskopp Citation2013). One way to deepen the understanding of this culture of silence is to examine its socio-material and institutional foundation. This is a domain that has predominantly been about institutional caution on the amount and nature of information concerning oil-related activities that the public receives.

From an institutional perspective, the regimes of secrecy may not necessarily be accidental omissions or what are often called ‘institutional gaps’. They are also sometimes selective choices that render constituents adequately governable (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008). The existence of political geographies of knowledge and ignorance, as the scholars point out (2008, 6), make these variables more or less strategic ploys of government. As a ploy, therefore, non-knowledge may be cultivated as a product of a deliberate plan (2008, 9). In the context of the oil industry in Uganda, this widely goes by the expression ‘managing expectations’—a way of controlling the zeal and anxiety about oil. In this case, it is not necessarily the expectations that are being managed but the anticipated socio-material effects of such expectations. The wood-economy in the case above offers a good example: the practices and subaltern systems of wood production that rely on certain patterns of social organisation of micro-mobilities and stasis were affected by the strategic production of disinformation about the Right-of-Way.

Through our multiple field visits, we got to learn that the project affected persons (PAPs) were advised by ‘the EACOP people’ not to speak to anybody about the pipeline and if somebody came to talk to them, they should seek clarification from the EACOP staff.Footnote5 The sort of information that the local communities sought for had nothing to do with the detailed account of the sophisticated engineering design of the pipeline. Rather, the communities wanted to relate the Right-of-Way to their ontologies of socio-economic production.

Building on the idea that the ROW-making process could aid our understanding of the socio-material dimension of governing mobilities, we suggest that the specific framework for regulating the flow of information was not necessarily about the containment of knowledge. Rather, it was the socio-material effects of being adequately informed that was being governed. This is substantiated in the next section, where we explore how the anxieties associated with disinformation effectively materialized into concrete contentions over dispossession, displacement and compensation, at the heart of which lies the question of (im)mobilisation and monetisation of the properties of the communities affected by being within and around the Right-of-Way.

(Im)mobilizing and monetizing things

As an interim conclusion we can say that the effects of ROW-making and eventually the pipeline itself on properties of the affected communities remain inevitable. Since the communities realized that they could not stop the pipeline from going through their villages, it was an imperative that the state develops a mechanism to attach monetary value to the things that would be destroyed, displaced, and/or relocated by the pipeline project. In the process, things that were formerly rooted in these areas as nodes of micro-pulses had to be moved by means of institutional injunctions. In light of this, three sets of empirical observations are noteworthy pointers, on the one hand, to Foucault’s idea that one governs things, and on the other, to the idea that governmobility is about governing the socio-material aspects of movement and stasis.

The first pointer is the destabilising effect of the ROW-making process on socio-economic processes of property production among communities along its path. The wood economy is just one example among many others, such as the restructuring of settlement patterns by inducing the relocation of some project affected persons. The second pointer is the pre-existing and project-inspired attachment between people and an assortment of things that are part of their socio-economic organisation. In this regard, as we demonstrate in the following, the ROW-making process strengthened the bond between people and things, which had to be factored in the calculus of the state in the form of matrices of property valuation. Therefore, as a third pointer, the production and government of displacement in the process of seeking to move oil tended to be more about institutional navigation of the people–thing relationship among the affected communities.

The question of government becomes even more significant if one interrogates—as we do—two things: first, the political geographies of knowledge (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008) about things; and second, the subaltern geographies of things whose attachment and value to the people are the primary concern of government (Foucault Citation1991, 93). Succinctly put, government is about the power relations that produce not just a well-calculated knowledge about things that are (to be) located in the midst of particular social groups, but also the power to render certain things more valuable than others. In respect of this, things that are deemed to be more valuable such as oil are made to gain Right-of-Way, by pushing aside those that are deemed to be less valuable.

In Uganda, the attachment of value on things is an institutional but decentralized process that begins with periodic update of property inventories at subnational levels. These inventories also highlight the matrices of rates that guide the central government authority known as the chief government valuer (CGV) to calculate and allocate monetary compensation to persons whose property would be impinged upon by government projects. As a result of this aspect of decentralization, both the value of things and valuable things in Uganda differ across space and time.

Given that districts are only administrative units that are not always differentiated in terms of social, economic and cultural practices, the creation of what one might term as ‘bordered properties’ tends to have significant polarizing effects across communities. By bordered properties, we refer to a situation whereby something is part of the subnational property inventory in one administrative unit but not in another. Asked about the issues he had to deal with when his people got to know that they would be displaced by the pipeline’s Right-of-Way, but compensated for losses, damages and disturbances to their socio-economic organisation, the response from the already cited chairperson provides an example of bordered properties:

Many… very many, but some of them are beyond me. One PAP complained a lot about his local herbs. I gave him a letter to go to the district but he was told that the district did not have compensation rates for herbs like Aloe Vera […]. He had many other kinds of herbs that he had planted, but will lose everything. In other districts like Sembabule you could find that these herbs were allocated compensation rates, but in Lwengo they were not accounted for because different districts listed all the items and plants to be included in the compensation rates booklets differently. We are told it is done every year. Our district had not attached value to things like herbs, yet the locals find them important.Footnote6

The ROW-making process underlines the interface between crude oil and subaltern socio-material organisation of production processes bringing about a competing attribution and reconfiguration of values to governable property as well as to those that are simply ungovernable. Evidently, oil as a mega property imbued with a kind of value-power dislodges as well as erratically relegates other property to the realms of the ‘not valuable’. This refers us back to the question of power: who determines what makes way for what, where and when, and most importantly, why? To highlight this further, we take land—the axis of property claims in the search for the pipeline’s path—as an example.

Although land has multiple socio-economic and cultural meanings, the attributes that the delegated state agencies evaluated in the context of the ROW-making process were basically size, land-use type, and the extent of disturbance or loss. In the process of making these evaluations, the same agencies were also empowered to determine the nature and extent of project-induced disturbance or loss. In this regard, the understanding of losses, damages and disturbances was no longer based on the explicit experience of the affected individual, but on what the agencies understood to be right. As a result, land-based constituents such as food crops, commercial trees and housing were among the constitutive valuable materialities of land. In this evaluation process, however, we observe a problematic tendency: the attachment of land value to the fraction of the land that was totally or partially damaged or lost but not to the qualitative ways in which the damage affects the life of the land owner.

We reviewed some property declaration forms issued to property-owners by NEWPLAN, the agency contracted to develop the property inventory for compensation. One case indicated that a project affected person would lose close to an acre of his land to the pipeline project. This portion of the individual’s land was valued at 2.87 million Ugandan Shillings (UGSHs, approx. 680 Euros). But because this particular individual also had other valuable things on this land, his compensation value rose to UGSHs 18.7 million (approx. 4,400 Euros).

A second case is of a female small-scale retail shop owner in Luanda (Rakai district)—a claimant for compensation for loss of about a quarter of an acre of her land to the ROW. Her hope to raise enough money to build a small house on this land has waned with the pipeline. The valuation assessment indicated that the shop-owner receives UGSHs 468,000 (approx. 114 Euros). Added to what is assumed to be the value of all other associated disturbances, the shop-owner was allocated on UGSHs 660,000 (approx. 157 Euros). In her view, this is considerably less than what she paid for the land and it will never get her another piece of land anywhere in the village. Besides, she cannot make any good use of the remaining piece which is now called ‘orphaned land’. Let us place this into perspective.

The cases of the two affected individuals above illustrate the visibility of governmental power not just in determining the pattern of movement of oil, but also the pattern of stasis of those who are to be affected by it. There is a concrete power framework with a geometric bearing that relentlessly reverberates outwards from a known center (Massey Citation2005; Green Citation2016) of the Ugandan state. With this power framework, the relatively stable, subaltern and somewhat sedentarist social processes of production in this part of Uganda have been drawn into complex socio-material relations veering towards producing new forms of elemental (im)mobilities. This example can apply to a multitude of mega infrastructure projects across different parts of the world that are embedded with certain mobility visions and aspirations.

There are two salient analytical dimensions to the Ugandan experience. The first is the country’s push to materialize and operationalize its oil industry by extracting oil out of the ground, pumping it to the central collection facilities and having the oil transported to willing buyers at great distances. However, this is more than just having the oil moving from Hoima to Tanga, and beyond. It is also about navigating an assortment of technological, geopolitical, socio-economic and environmental preconditions. The second is how this agenda is arrived at. At the heart of this, lies the practical manifestation of mobility politics, founded around what can be defined as governmentalities of oil movement. The epicentre of this mobility politics is the function of state-centred power in transferring people’s Right-of-Place, to produce the pipeline’s Right-of-Way.

The stakes in this Right-of-Way and Right-of-Place encounter are largely socio-material in nature: for the Right-of-Way, the stake is oil and its envisioned future benefits to Uganda’s political economy as a whole; and for the Right-of-Place, it is a collection of all those ‘things’ (Foucault Citation2007, 96) that matter to the pipeline-affected communities, such as commercial tree-gardens, herbal plants, graveyards, shops, houses and banana plantations. This oil-vision has been rationalized against people’s elemental Right-of-Place, resulting in institutional injunctions of (dis-)placements. The significance of the institutional (dis-)placements can be better understood by zooming into the multiple material dimensions of their undertaking: that is, the concrete effect of people having to get-on-the-move, to search elsewhere for those things that matter to their wellbeing.

On a very general level, oil is a substance whose role to the global economy remains capacious (Watts Citation2012, 439). In this sense, mobility, both in the search for oil, and in the development of consumption networks, has shaped the geopolitical landscape and resource struggles around the world today (Ikenberry Citation2008; Labban Citation2008; Watts Citation2018). Oil movements embody the flow of oil itself and also other materialities, such as oil policies, standards, risks, ideas, practices, technologies and, most importantly, money.

At different scales, these flows are networked through a geopolitical configuration of power, some of which operate at a distance. For instance, the invocation of the so-called international standards depicts a certain configuration of governmobility practices that allows for fluidity of standards and practices. Here, the notion of ‘material politics’ explored by Barry (Citation2013) comes to mind, as much as does the recent call by the European ParliamentFootnote7 for Uganda to revisit its modes of operation in the context of the EACOP pipeline. This is part of the ‘standards’ discourse embedded in the oil industry: but what else do standards allude to, if not socio-materialities—the things that matter to the wellbeing of a given social group in space and time?

The EACOP represents not only the infrastructure for standardized movement of oil but a multiplicity of socio-economic materialities—the things that are often the concern of government. That said, governmobility can be redefined in view of the framework of power that is brought to bear on (im)mobile things: that is, the socio-material, politico-economic and cultural flows across space and time. Thus, if government is to be understood as the conduct of conduct, yet conduct is not entirely static, governmobility should be viewed as the conduct of (im/mobility) conducts, around things that are both tangible and intangible, real and imagined.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have made an attempt to draw an empirical and theoretical nexus between the process of establishing spaces for an oil infrastructure, and the concrete everyday (im)mobility practices of the riparian communities in Uganda. With the three-dimensional conceptualization of the ROW-making as a technical/technological, physical and socio-material process, we gained insights into the fundamental (im)mobility concerns that such mega projects pose to the realities of local communities.

From a mobility perspective, the processual realization of the ROW highlights three things: first, the performance of (im)mobilities is a thought process: that is, they are preconceived and concretized by the establishment of enabling spaces and conditions such as the Right-of-Way, to enable their operationalisation. Second, (im)mobilities are inherently about competing socio-materialities and standards that are shaped by mobile functions of governmental power. In the case of the EACOP, as maybe elsewhere, the technical and technological aspects of such infrastructures are only modalities for the realization of these socio-materialities. To Uganda as a country, the crude oil pipeline is only a valuable vessel because of the crude oil that it will carry. At the level of the pipeline–riparian communities, frictions surrounding the communities’ displacement in the making of the pipeline’s ROW are only important because of the losses and gains associated. The third aspect is the question of government of mobility. Having framed (im)mobilities as being inherently socio-material, governing mobility has very little to do with movement itself, but with the underlying inspirations, standards and potential outcomes of such movements.

The Foucauldian approach to government offers the leeway to unpack the concept of governmobility: one governs things as we pointed out. So if one has to govern (im)mobility, it is about governing the things that inspire or that are associated with particular (im)mobilities rather than the practice itself. Whereas technologies of power are seen to bear on mobilities by, for instance, posing restrictions, displacements and relocations, it is the underlying logic that is the concern, and how this is reinstantiated and reaffirmed, actively and dynamically, by specific exercise of power over (im)mobilities. We believe this framing opens up a new perspective on the understanding of the government of (im)mobilities, with particular relevance to policy and academic research; more so, in the context of mega infrastructures such as the EACOP pipeline.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview, Lwengo, February 2020 (original recording in Luganda, the local language).

2 Interview, Kamuli village, Luanda sub-county, Rakai district, October 2020 (conducted in Luganda).

3 Interview, Kamuli village, Luanda sub-county, Rakai district, October 2020 (conducted in Luganda).

4 Informal conversation with a local council chairperson, in Mbirizi, Lwengo district (January, 2020).

5 Conversation (in Luganda) with two female Community-Rights Activists from Rakai and Kyotera. (Kyotera, November 2020).

6 Informal conversation with a local council chairperson, in Mbirizi, Lwengo district (January, 2020).

7 Plenary sitting of European Parliament, Wednesday, 14.09.2022; <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2022-09-14-ITM-015-02_EN.html> Accessed 28 September 2022.

References

- Adey, Peter. 2006. “If Mobility is Everything Then It is Nothing: Towards a Relational Politics of (Im)Mobilities.” Mobilities 1 (1): 75–94. doi:10.1080/17450100500489080.

- Atuhaire, Patience. 2022. “Why Uganda Is Investing in Oil despite Pressures to Go Green.” BBC News. 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-60301755.

- Bærenholdt, Jørgen Ole. 2013. “Governmobility: The Powers of Mobility.” Mobilities 8 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.747754.

- Bahgat, Gawdat. 2002. “Pipeline Diplomacy: The Geopolitics of the Caspian Sea Region.” International Studies Perspectives 3 (3): 310–327. doi:10.1111/1528-3577.00098.

- Barry, Andrew. 2013. Material Politics: Disputes along the Pipeline. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Basedau, Matthias, and Wolfram Lacher. 2006. “A Paradox of Plenty ? Rent Distribution and Political Stability in Oil States.” In Dynamics of Violence and Security Cooperation, Vol. 21. Hamburg: German Institute of Global Area Studies.

- Beamish, Thomas D. 2000. “Accumulating Trouble: Complex Organization, a Culture of Silence, and a Secret Spill.” Social Problems 47 (4): 473–498. doi:10.2307/3097131.

- Breusers, Mark. 2001. “Searching for Livelihood Security: Land and Mobility in Burkina Faso.” Journal of Development Studies 37 (4): 49–80. doi:10.1080/00220380412331322041.

- Büscher, Monika, and John Urry. 2009. “Mobile Methods and the Empirical.” European Journal of Social Theory 12 (1): 99–116. doi:10.1177/1368431008099642.

- CNOOC, Total, and Tullow. 2016. Land Acquisition and Resettlement Framework for the Lake Albert Petroleum Development Project. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2006. On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World. London: Routledge.

- D’Andrea, Anthony, Luigina Ciolfi, and Breda Gray. 2011. “Methodological Challenges and Innovations in Mobilities Research.” Mobilities 6 (2): 149–160. doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.552769.

- Dargay, Joyce, and Mark Hanly. 2004. “Land Use and Mobility.” In World Conference on Transport Research Istanbul, Turkey, July 2004. Istanbul: UCL Discovery. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1236.

- Dean, Mitchell. 1999. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Foucault, Michel. 1991. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality with Two Lectures by, and an Interview with Michel Foucualt, edited by G Burchell, G Colin, and P Miller, 87–104. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979. Translation by Graham Burchell. New York: Macmillan.

- Government of Uganda. n.d. Environmental & Social Impact Assessment: The East African Crude Oil Pipeline Project – Technical Extract. Kampala: National Environment Management Authority.

- Government of Uganda. 2019. “The Land Acquisition (Development of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline) Instrument, 2019.” Statutory Instrument No. 105, Kampala: Government of Uganda.

- Green, Kathryn E. 2016. “A Political Ecology of Scaling: Struggles over Power, Land and Authority.” Geoforum 74: 88–97. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.007.

- Gwayaka, Peter Magelah. 2014. “Local Content in Oil and Gas Sector: An Assessment of Uganda’s Legal and Policy Regimes.” 28, 2014. Kampala.

- Hannah, Matthew. 2000. Governmentality and the Mastery of Territory in the Nineteenth-Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hannah, Matthew. 2017. “Governmentality.” In He International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology, edited by D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, and R. Marston, Vol. 6, 3188–3194. Chichester: John Willy & Sons.

- Hannam, Kevin, Mimi Sheller, and John Urry. 2006. “Editorial: Mobilities, Immobilities and Moorings.” Mobilities 1 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/17450100500489189.

- Hickey, Sam, Badru Bukenya, Angelo Izama, and William Kizito. 2015. “The Political Settlement and Oil in Uganda.” 48. March 31. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2587845.

- Hindess, Barry. 1996. Discourses of Power: From Hobbes to Foucault. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2008. “Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy.” Foreign Affairs 87 (5): 165.

- Jayawardena, Sharni. 2011. “Right of Way: A Journey of Resettlement.” 5.2011.

- Jensen, Anne. 2011. “Mobility, Space and Power: On the Multiplicities of Seeing Mobility.” Mobilities 6 (2): 255–271. doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.552903.

- Kinyera, Paddy. 2020. The Making of a Petro-State: Governmentality and Development Practice in Uganda’s Albertine Graben. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Kinyera, Paddy, and Martin Doevenspeck. 2019. “Imagined Futures, Mobility and the Making of Oil Conflicts in Uganda.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 13 (3): 389–408. doi:10.1080/17531055.2019.1579432.

- Labban, Mazen. 2008. “Space Oil and Capital.” Space Oil and Capital, 2008, 1–179. doi:10.4324/9780203928257.

- Lemke, Thomas. 2015. Foucault, Governmentality, and Critique. Foucault, Governmentality, and Critique. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315634609.

- Lemm, Vanessa, and Miguel Vatter. 2015. “The Government of Life: Foucault, Biopolitics, and Neoliberalism.” In Contemporary Political Theory. New York: Springer Nature. doi:10.1057/cpt.2015.24.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2008. “Social Reproduction, Situated Politics, and the Will to Improve.” Focaal 2008 (52): 111–118. doi:10.3167/fcl.2008.520107.

- Lund, Christian. 2016. “Rule and Rupture: State Formation through the Production of Property and Citizenship.” Development and Change 47 (6): 1199–1228. doi:10.1111/dech.12274.

- Manderscheid, Katharina. 2014. “Criticising the Solitary Mobile Subject: Researching Relational Mobilities and Reflecting on Mobile Methods.” Mobilities 9 (2): 188–219. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.830406.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- Mbabazi, Pamela K. 2013. “The Oil Industry in Uganda; a Blessing in Disguise or an All Too Familiar Curse?.” In The 2012 Claude Ake Memorial Lecture, edited by Peter Wallensteen, 1–66. Uppsala: The Nordic Africa Institute.

- Merriman, Peter. 2016. “Mobilities II: Cruising.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (4): 555–564. doi:10.1177/0309132515585654.

- Miller, Peter. 2004. “Governing by Numbers: Why Calculative Practices Matter.” In The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader, edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift, 179–190. Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell.

- Murray, Alan T, and Tony H. Grubesic. 2007. “Overview of Reliability and Vulnerability in Critical Infrastructure.” In Critical Infrastructure: Reliability and Vulnerability, edited by Alan T. Murray and Tony Grubesic, 1–8. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

- Olanipekun, Ifedolapo Olabisi, and Andrew Adewale Alola. 2020. “Crude Oil Production in the Persian Gulf Amidst Geopolitical Risk, Cost of Damage and Resources Rents: Is There Asymmetric Inference?” Resources Policy 69 (101873): 101873. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101873.

- Olanya, David Ross. 2012. “Resource Curse, Staple Thesis and Rentier Politics in Africa.” In Acumulação e Transformação Em Contexto De Crise Internacional. Maputo: Instituto de Estudos Sociaise Económicos.

- Proctor, Robert N, and Londa Schiebinger. 2008. Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Roberts, Paul. 2004. The End of Oil: On the Edge of a Perilous New World. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Sheller, Mimi. 2016. “Uneven Mobility Futures: A Foucauldian Approach.” Mobilities 11 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1080/17450101.2015.1097038.

- Sheller, Mimi. 2018. “Theorising Mobility Justice.” Tempo Social 30 (2): 17–34. doi:10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2018.142763.

- Šnajberg, Oxana. 2015. “Valuation of Real Estate with Easement.” In 16th Annual Conference on Finance and Accounting, ACFA Prague 2015, 420–427. Prague: Procedia Economics and Finance.

- Synergia. 2016. Nicala Corridor Resettlement Status for Lenders. Sao Paulo: Synergia.

- Verma, Shiv Kumar. 2007. “Energy Geopolitics and Iran–Pakistan–India Gas Pipeline.” Energy Policy 35 (6): 3280–3301. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.11.014.

- Watts, Michael. 2012. “A Tale of Two Gulfs: Life, Death, and Dispossession along Two Oil Frontiers.” American Quarterly 64 (3): 437–467. doi:10.1353/aq.2012.0039.

- Watts, Michael. 2018. “Frontiers: Authority, Precarity, and Insurgency at the Edge of the State.” World Development 101: 477–488. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.024.

- Welskopp, Thomas. 2013. “Bottom of the Barrel.” Behemoth 6 (1), 004. doi:10.1515/behemoth-2013-0004.

- Witte, Annika. 2018. An Uncertain Future – Anticipating Oil in Uganda. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.