Abstract

This paper studies recreational mobility as it unfolds as an integral part of the heterogeneity of practices staged in front of a camera on a busy street in Stockholm, Sweden. By analyzing the production- and recognition-work of ‘doing-jogging/dog-walking-in-the-city’ we argue that recreational mobility accomplishes something more than walking in these settings. In the modern layout of a condensed city, mobility is prioritized due to its utility. In this context, recreational mobility, in all its forms, becomes what anthropologists and sociologists describe as an ‘othered’ – and as such it exists as an odd curiosity. While this puts recreational mobility at a marginal position it also enables us to better understand mobility in general – though the alterity of recreational mobility. Based on the empirical observations the paper highlights three findings in relation to recreational mobility: (1) its nestedness within everyday mobility; (2) its work of being different than ordinary use of the space – as alterity; and (3) its role as a methodological challenge, especially for studies of on-street level mobility, where different teleologies of mobility and different modalities coexist. Here the materiality of the street and the assemblages play a crucial role as observable materialities within the production- and recognition-work of doing more than walking.

Introduction

The growing interest in recreational mobility highlights the struggle with categorizations of mobility and the inclusion/exclusions that these taxonomies have created (Cook, Shaw, and Simpson Citation2016, Qviström, Fridell, and Kärrholm Citation2020). Predominantly mobilities tend to be categorized according to modality, such as driving, public transport, cycling, walking, etc., or through purpose such as commuting, grocery shopping and so forth. Categorizing mobility according to these taxonomies inevitably defines recreational mobility as othered, excluded or as a marginal complement to more useful mobility. Hence, focusing on recreational mobility can be a way to focus on what we leave out of mobility (Vannini Citation2009). Many of these studies also rely on the spatial space in which the mobility takes place. A road is expected to facilitate driving and public transport, a nature reserve allows for recreation and a sidewalk allows the pedestrians to walk. But different modes of mobility can appear where they are not expected to be conducted. In this paper we study a busy street to identify the potential presence of recreational mobility at a site which is more known for its commercial and commuting practices. This differs considerably from the existing studies of recreational mobility – that tend to focus on sites of recreation (Qviström Citation2016, Citation2017) or the qualitative sensations of doing recreational mobility (Cook, Shaw, and Simpson Citation2016, Collinson Citation2006, Larsen Citation2019). By focusing on a busy street, this paper can be seen as a way to study recreation as an integral part of the heterogeneity of practices that are staged on streets and pathways (for an exception see McGahern Citation2019). Focusing on recreational mobilities alters the production- and recognition-work of doing-walking-in-the-city by accomplishing something more than walking in these settings. In particular, we will study the accomplishments of dog-walking and jogging as forms of recreational mobility taking place in the same setting as commuting or shopping by looking at the practice in situ. The street that we study is a busy street that is designed for commerce as well as a large amount of pedestrian and cycling mobility. That recreational mobility takes place on this street should, in itself be seen as peculiar.

In the following, we will start with an introduction to the ethnomethodological tenets that enable us to observe doing-being-different as it unfolds on a busy street. Second, we discuss the methodological challenges that a video camera imposes on us. Third, we question the membership categories that we can identify as dog-walking and jogging, highlighting both what we can identify but also its inherent ambiguity. Fourth, we focus on the accomplishments of doing-being-different by analyzing the work that joggers do in concert with co-present pedestrians. Finally, we acknowledge the nestedness of recreational mobility that in turn problematizes all categorizations of membership categories if they are regarded as exclusive.

On doing being different and just-thisness

Whatever we may think about what it is to be an ordinary person in the world, an initial shift is not to think on an ‘ordinary person’ as some person, but as somebody having as their job, as their constant preoccupation, doing ‘being ordinary’. It’s not that somebody is ordinary, it’s perhaps that that’s what their business is. And it takes work, as any other business does… They and the people around them may be coordinatively engaged in assuring that each of them are ordinary persons, and that can then be a job that they undertake together. (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson Citation1992, 216)

This extensive quote from Harvey Sack’s lecture held in spring 1970 nicely captures a central tenet in ethnomethodology. What we are is accomplished through the work we do to be what we are. Even ‘being ordinary,’ as bland and mundane as it may seem, requires work to be enacted (on enacted, see Law and Urry Citation2004). Thus, personal characteristics, identity, gender (Czarniawska Citation2013) or even temporary characteristics such as being an ordinary pedestrian or a jogger can be regarded as occupations – as the accomplishment of work. This is also a collaborative work; it requires both someone doing that work (whatever it might be) and onlookers that see and acknowledge this work (whatever it might be). Ryave and Schenkein (Citation1974) phrased this duality of work as production- and recognition-work, emphasizing the mutual effort both by those that make the work and by the ones that witness this work being done. Ethnomethodological approaches to mobility can both affirm a focus on modalities (such as driving (Laurier Citation2019, Laurier, Brown, and Lorimer Citation2012), cycling (McIlvenny Citation2015, Lloyd Citation2020) and walking (Liberman Citation2013)), as well as assist studies that categorize mobility through its motives and meanings (such as commuting, shopping or jogging (Collinson Citation2006)). Taken together, these studies provide a detailed empirical account of the social accomplishments as they are unfolding in situ, but they also highlight two significant aspects of whatever mobility they study. First of all, work that ethnomethodologists observe is related to the spatial place where this work is conducted. Production- and recognition-work is situated, and as such the setting - including people, materialities and the spatial place – is participating in this co-production. One could argue that it is much easier to do ‘being ordinary’ at home in front of a television, or to do ‘being a clerk’ standing behind a counter in a store. Place plays a significant role in which at times have been described as affordances (Gibson Citation1977, Citation1979), the local site providing a series of more or less possible topics of practice and behavior.

Second, both the spatial affordances and the social organization of the place rely on the familiarity of our encounters with similar situations, as part of practical matters of what at times was recognizable as ‘common sense’ (Pollner Citation1974). We recognize a practice or a behavior as part of the just-thisness of the work that we label it as – as it unfolds – or what ethnomethodologists term haecceity. Haecceity, from Latin, was used by GarfinkelFootnote1 to refer to the ‘just thisness’ of a setting but it also highlights that the concreteness of things is part of the phenomenon of social order (Lynch Citation1993). Ethnomethodologists have been using the phrase ‘every next first time’ as a way to highlight thisness (Garfinkel and Rawls Citation2002 see also Cooren Citation2009). Returning to Sack’s work of doing ‘being ordinary,’ haecceity refer to the details of this production- and recognition-work that enable us to account it as doing ‘being ordinary’. (Garfinkel (Citation1967) also described this as passing – that we pass as something through the work that we do which consists of ‘just-thisness’). Haecceity was presented as the details that ‘makes an object what it uniquely is’, not based on an essentialist assumption but rather from an indexical condition. Thus, the ‘just thisness’ that we are looking for is indexical to the situation as well as to the place, the street where it is enacted. In a situation such as recreational mobility or doing-jogging and doing dog-walking, then we have to look at the membership categories that arise in the production- and recognition-work. Membership categories was coined by Harvey Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (Citation1992) as a way to connect the ‘just thisness’ with identity. As Sacks pointed out, the membership categories are simultaneously also membership categorization devices whereby the identity is co-produced by the work. For example, holding a lit cigarette, doing-smoking, is both a membership category (of a smoker) and a membership categorization device (as the cigarette and smoking). Jogging is a work of both membership and a categorization device; more specifically, it can be seen as a category-bound activity. These membership categories are the ethnomethodological equivalent to what most sociologists refer to as identity, with the caveat that ethnomethodologists do not adhere to the analytical explanatory force that many sociologists inscribe to identity. The identity we talk about here is the result of the situation and not the individual (Liberman Citation2019).

Returning to the taxonomies of mobility: pedestrians, cyclists and drivers can be seen as membership categories belonging to the collection of ‘means of transport’ whereas shopper, commuter, and vagabond belong to the collection of ‘purpose of mobility’. Thus, initially the ethnomethodological approach can at first resemble contemporary categorizations of mobility. However, the shift from individual identity to collaborative, situated work of membership categories is both substantially methodological and theoretical. Especially when focusing on membership categories that explicitly are in conflict with important membership categorization devices such as the place where the work takes place. Having shown how ethnomethodology could be used to study recreational mobility, we will in the following look at how ethnomethodology could be used to study alterity - doing-being-different.

We choose Sack’s example of the somewhat boring work of doing ‘being ordinary’ for a reason since we do not think that recreational mobility, how ordinary it might seem, is doing ‘being ordinary’, especially along a busy street in the middle of a European city. The place plays a very important role in the production- and recognition work of membership categories. It’s much easier to do ‘being-ordinary’ in a living room or to do ‘being a clerk’ in a store. The site is a membership categorization device and therefore jogging on a track and field’s arena is something entirely different from jogging on a busy street. If we disregard these details, just-thisness of the situation, then we also disregard the foundation for accomplishing the social order that we argue that we study in the first place.

Recreational mobility can often be regarded as, what anthropologists and sociologists describe as, an ‘othered’ form of mobility, especially on a busy street. – As such it exists as a curiosity to mainstream mobility studies (what Vannini (Citation2009) for example describes as alternative mobilities). With this in mind it might be easier to talk about an occupation, a job, that is doing ‘not-being ordinary’ or doing ‘being different’, that is doing ‘being alterity’. This has been pointed out by ethnomethodologists, that the preoccupation of being different, just like being ordinary, requires work. This is what this paper wants to describe – the work of doing alterity. But what do we mean with alterity?

To exist is to differ; difference, in a sense, is the substantial side of things, is what they have only to themselves and what they have most in common. One has to start the explanation from here, including the explanation of identity, taken often, mistakenly, for a starting point. Identity is but a minimal difference, and hence a type of difference, and a very rare type at that, in the same way as rest is a type of movement and circle a peculiar type of ellipse. (Tarde Citation[1893] 1999, 72–73 translated by Czarniawska Citation2008: 255).

Drawing from Gabriel Tarde, Barbara Czarniawska (Citation2008) proposes the study of difference as the study of alterity, the ‘otherness’ of others but also the otherness of the self. In particular, she sees the possibility of affirming these differences as central to alterity and thus, a central part of negotiating selves (Czarniawska Citation2013). However, most of the times, social science is preoccupied with identity (whom are we like? and how?) and less on the question of alterity (how are we different? And from whom?). Looking at recreational mobilities on a busy street enables us to see the work of distinguishing oneself as different from the large cohort of pedestrians when doing-jogging or doing-dog-walking. In the setting of the busy street, jogging is a work of doing ‘being different’ rather than doing ‘being ordinary’. But as a job, it also has its own production- and recognition-work, its own membership categories that are in stark contrast with the expectations that the place, the busy street, provides. Thus, we will here describe the notion of alterity and how it can be used as a way to describe recreational mobilitýs marginal position, which also enables us to better understand mobility in general, though the alterity of recreational mobility. The way this paper approaches the alterity of recreational mobility, the combination of haecceity and alterity, even though there are challenges in combining them will, we hope, shed some new light on the phenomena of recreational mobility in particular dog-walking and jogging.

A day in a streets life

The theoretical approach as outlined above, inspired by ethnomethodology, also sets forth a set of methodological limitations. Ethnomethodology, with its phenomenological inspiration, focuses on that which is available for those that participate in the situation in their process of making their performances accountable. As such, ethnomethodologists do not rely on interviews since that itself would be its own interview-situation, instead they focus on what can be observed in naturalistic settings (see Silverman Citation1998). Hence, the extended use of camera and video in research has invigorated these theories and been instrumental but also changed considerably the last decades. In part this is due to accessibility. Mobile phones that can film and record are more or less an omnipresent extension of human bodies, and portable point-of-view cameras are cheap and easy to use. Almost everyone has the ability to visually tell their own stories as Vannini (Citation2020b, 4) points out. As video use is no longer exclusive, its use in research increases. This has changed the practice of ethnography where fieldnotes are no longer the main recourse; the experiences can be corroborated by a non-human in the form of a camera. The role of the camera within the mobilities turn with its mobile methodologies has also been substantial (Büscher Citation2006; Laurier Citation2014; Bates Citation2015; Vannini Citation2020a, on mobile methodologies see Büscher and Urry Citation2009; Büscher, Urry, and Witchger Citation2010; D'Andrea, Ciolfi, and Gray Citation2011). In particular the camera has: first, enabled documenting, editing and following sequences on the move – thus capturing the practice of moving (for a good example see Bates and Moles 2023) and second, opened up the interpretation to the sensory, emotional and kinaesthetic dimension of experiences (as pointed out by Law and Urry Citation2004: see also Law Citation2004 on the critique of social science methods).Footnote2 This is particularly obvious in the growing corpus of micro-oriented and phenomenological studies of mobilities and everyday life (see for example Pink Citation2008). This has also revitalized the possibility of communicating the ethnographic accounts through films, thus providing another means of academic communication (see for example Vannini Citation2017).

While acknowledging these benefits, we will in the following use the video-camera somewhat differently. Inspired by the classical use (when they were bulky and difficult to maneuver), static cameras were located on the streets to capture the life in the city in the 1970s, by for example Whyte Citation[1988] 2009, and to document work by ethnomethodologists in workplaces (see for example Heath, Hindmarsh, and Luff Citation2010). We propose a continued use of the tripod and stationary cameras to study mobilities as a complement to the more novel approaches. While much of the methodological progress in mobilities research has stemmed from qualitative use of the camera for interpretative practices, the use of stationary positions can enable collaboration between qualitative and quantitative investigations (Goertz and Mahoney Citation2012). Qualitative studies have utilized the camera extensively but also problematized its role as a methodological tool, while quantitative research simultaneously has used cameras to equal amount but without any real methodological problematization.

The use of a tripod camera has also been used in quantitative studies, for example in documenting pedestrian movements. In a classical study of pedestrians in Copenhagen Lene Herrstedt (Citation1981) used a Sony video camera, a tripod and a TV connected to a VCR to collect and analyze pedestrians. While this practice was not visible in her findings, she described her methods in an appendix. Her account resembles the qualms qualitative researchers usually obsess about. Identifying a good location to place the tripod, testing several sites; placing the camera at an entrance portal at a building on the street level; filming from inside a car, parked beside the sidewalk; mounting the tripod on light post 3–4 meters above the street level; having pedestrians obscured by cars, passing busses and other pedestrians; struggling with the shades and lighting of the sun; these were all examples of the challenges that a quantitative researcher faced when using a camera, not unlike what we still struggle with. All these fascinating and situated conditions were absent in the main report and the findings – reporting on the statistical basis of pedestrians. For a qualitative researcher, these obstacles and tricks both reveal the challenges we all encounter when using camera as well as a confirmation of the situatedness of any investigation, even the ones with recording devices.

Despite these limitations, as with most qualitative studies, they are still aimed at comprehension and understanding rather than causality and prediction, more specifically what Vannini (Citation2020b) calls the ethnographic intent. With this paper, we intend to provide a bridge between the qualitative and the quantitative but remain focused on the interpretative practice.Footnote3 These situated, indexical conditions for filming are central to the use of camera for research. In a study by Weilenmann, Normark and Laurier (Citation2014) the researchers experimented with the location of their tripod in an ethnomethodological study of mobile formations walking through a revolving door. While Herrstedt preferred the birds-view perspective (in church towers), Weilenman, Normark and Laurier concluded, by testing birds-view, shadowing, participants-view (lending the camera to the mobile formations) and a pedestrian-level view, that the static camera on the same level as the participants was optimal. Many transport studies have a tendency to prefer birds view as they make it easier to count. However, the ‘street level’ perspective also has its methodological and theoretical advantages, central for this study as they provide the same view as the actors in the production- and recognition-work as it occurs. Hence the camera can potentially capture that which is available for the actors from within, and not the ‘hidden’ result/consequences of actions.

This is both the major strength and a potential weakness with the proposed method. If we assume that the membership categories are the result of the devices available within the production- and recognition-work, then we have to capture the devices available within that situation. But our ability to identify these devices is dependent not only on the situation, but rather our recognition-work as interpreters when analyzing the footage. Hence it is important that the interpreter identifies, participates and acknowledges their dependency as part of the commonsense, public, shared and transparent knowledge (or documents of) that they use to associate membership category devices with membership categories. This challenge of membership categories has been contested in ethnomethodology (Silverman Citation1998), and we argue that the authority of assessing membership categories thus does not derive from the images themselves but rather from the interpreter’s comprehension and participation in the setting similar to the main objective of the ethnographic intent (Vannini Citation2020b).

As we look closer on the performances that unfold in this paper on doing-alterity, we will also use membership category devices to make quantitative observations using an approach that Cochoy and colleagues have labeled observiaire (Cochoy, Hagberg, and Canu Citation2015, Calvignac and Cochoy Citation2016, Cochoy et al. 2019). This means documenting, like a questionnaire, the things that are observable in the video into a spreadsheet. Like a survey, this approach provides a description of the situation in numbers. But unlike an average – a non-exceptional person on some statistical basis – this survey provides a temporary image of a street view compilation and not a statistical construct in the traditional sense. The camera can be used to identify observable materialities such as dogs, dog-leads, clothing and so forth: concrete things that are membership categorization devices for the ‘just thisness’ that is used to enact social order or to identify the job of doing ‘being ordinary’ as well as the job of doing ‘being non-ordinary’. The challenge proposed by the existing taxonomies of mobility is not only limited to the scant interest for recreational mobility alone; it is largely a methodological challenge. This is especially true for studies of on-street level mobility, where different teleologies of mobility and different modalities coexist ‘nested’ within each other. Such studies have struggled with the heterogeneity of mobility practices (un)intentionally capturing more than purposeful mobility.

Thus, drawing from previous visual methods in mobilities studies (Normark, Cochoy and Hagberg Citation2019), we have identified all occasions of joggers and dog-walkers for one day in a street’s life, based on the observable tokens of that individual. We have obviously missed those concealing their jogging attributes or their dogs (for example one person carried her dog). Still, a considerable number of pedestrians passing the video lens passed as joggers or dog-walkers. Collecting all these instances enables us to say something about the alterity of recreational mobility, and analyzing the videos of this recreational mobility enables us to say something about the just-thisness of doing jogging and doing dog-walking.

Götgatan: a busy street linking the city of Stockholm together

As part of a research project (Pilotplats Cykel) and an urban redesign/experiment (försöket Götgatan) of a busy street in Stockholm, researchers and the municipality filmed Götgatan on three locations one weekend and one weekday before and after the urban redesign in 2014. In the following, we will focus on the footage from 6:00 in the morning to 20:00 in the evening on a weekday in the spring prior to the redesign of one of the locations. During the project, the researchers also spent a considerable time on the street, observing and taking notes to account for the commonsense experiences of being part of that place.

Götgatan is a central road south of Stockholm connecting the city center with the south of Stockholm through the island called Södermalm. There is both a car tunnel and a subway in parallel with Götgatan increasing the street's importance as a directional throughway but also alleviating part of the traffic that otherwise would have used the same road. Still, it is busy. A pedestrian count was conducted during the project, estimating that on average 350 persons passed the location every ten minutes (Envall and Breyer 2014). Södermalm is not in the city center but at times been described as the SOHO of Stockholm with many restaurants and inhabitants engaged in creative occupations. As such it is an attractive area, and the street, along which many stores and cafés are located, is busy both with people visiting the street and pedestrians and cyclists passing by. While some of the buildings contain offices, most of the houses are apartments. Thus, the street can be seen as an active place 24/7, or simply put, it is a very busy street of both mobility and activities.

For this paper, we identified all the joggers and dog-walkers that passed the video lens during the day of filming in spring 2014. In total, 103 dogs passed (with their human companions) and 47 joggers ran past the camera. Considering the vast amount of people passing that location, this was of course very small population; we can estimate that they were between 1% and 1‰ of the cohort of pedestrians passing the camera. Yet for that particular reason – as an othered form of mobility – they become important to study.

Challenges of observing dog-walking as recreational mobility

Can recreational mobility be observed? Unless we ask people, we cannot definitively pinpoint the motives for individuals. However, as members of a society we do, in practice, regard some activities as more recreational than others, and as people perform these activities, we regard them as members of doing recreation. One of these recreational activities is dog-walking. In the following, we will first observe the presence of dog-walkers on the busy street of Götgatan, and second, discuss whether this participation on the street is recreational or not.

Götgatan, despite being in a central urban area in Stockholm, is inhabited by animals. Even though we tend to ignore their urban existence (Holmberg Citation2015; Bull, Holmberg, and Åsberg Citation2018), we do share the city with birds and other, non-domesticated animals. They adjust to our rhythms and inhabit the street when the human population is low. Domesticated animals however, and in particular dogs, are bounded and connected to the ways humans populate the street. The ordering of dog-walking, forcing the human and the non-human to be physically connected, enabled us to regard them as an assemblage, a hybrid, or what Mike Michaels (Michael Citation2000) termed a co(a)gent (Laurier, Maze, and Lundin Citation2006). The main aspect here is that they are seen as one assemblage by both the one viewing the film and by those co-present in the production- and recognition-work of walking in the street. We could observe dog-walkers by the presence of a dog and a dog-lead, as membership category devices for the assemblage. As pointed out by Michaels (Michael Citation2000) on his description of the Hudogledog (human-dog-lead-dog) we miss those occasions when such co(a)gent passes the camera without their dog (sundered from parts of their assemblage).Footnote4 Thus, we only captured the occasion when these members of dog-walkers were displayed together. This highlights the strength and simplicity with the proposed methodology while simultaneously acknowledging its limitations in regard to what is being presented, especially in relation to the representativity that such methodology allows.

Observing a dog on Götgatan was simple even when it was intensely crowded. These 103 assemblages appeared regularly, with at most 10 assemblages within a 30-minute period (between 12:00–12:30 and 13:30–14:00). But was their existence evidence of recreational mobility? Dogs have been, and still are used for hunting, searching, guiding, working and comforting as well as companions, they are after all the animal what have been domesticated the longest (McHugh Citation2004). In this context, the ‘ritual’ of dog-walking is both a necessity for the animal and a process of contemplation for the human (Holmberg Citation2015 makes this especially clear), if not always so at least often enough to consider the practice of dog-walking as recreational (Holmberg Citation2015, Redmalm Citation2013). Thus, our assumption regarding dog-walking is not based on what is observable on the street, but rather on the detailed ethnographic studies of understanding dog-walking. Urban settings have been adapted to accommodate dogs, with services, dog parks, etc. (Instone and Mee Citation2011; Holmberg Citation2015; Laurier, Maze, and Lundin Citation2006), and similarly dogs that work, such as hunting and sheep-herding are practices tightly related to the place where the activity is situated. Dog-walking on a busy street is at least a form of doing-alterity. We also identified one category of dog-at-work, during our observation, a seeing-eye-dog, strengthening the perception and mobility of a person with impaired sight ().

Considering the place, a busy street, the dog-walking practice of mobility did not fit the taxonomy regularly used for that place. While the practice could be questioned as utilitarian or recreational (and for whom), it still highlighted the otherness of dog-walking on the urban street, making the alterity its strength of investigation. The dog-walkers blended into the urban street, usually ignored (what Goffman (Citation1966) called civil inattention) by co-present pedestrians. Yet they were there, avoiding collision like the other pedestrians but with a rope connecting the two motional bodies. They were a mobile formation (McIlvenny, Broth, and Haddington Citation2014) where the dog at times was in-front, behind or beside the human. The motion was accomplished by the coordination; at times this motion was disturbed by the dog or the human pulling in other direction or the other, micro-struggles that were quickly resolved. At times the coordination between the bodies were fascinating to witness.

Challenges of observing jogging as recreational mobility

Doing dog-walking was easy to observe through the presence of dogs. For joggers the identification was not as straightforward. One apparent work for joggers was the physical activity of running. This was not only a relative difference in speed between a jogger and a pedestrian but also observed in the way the body and the legs were used. However, even though running was the main job, we also identified people that ran without having other membership categorization devices (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson Citation1992) associated with jogging. They were doing-being-different by running on the busy street, but at the same time not doing the work associated with doing-being-jogging. During the observed day 139 persons ran on Götgatan but only one third of them were joggers.

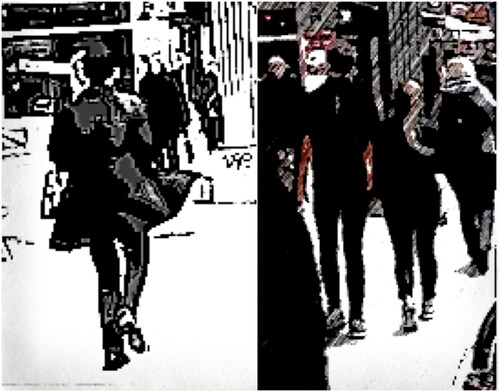

Beside running, another observable membership category device was clothing. Many of the humans that ran were not dressed as joggers. Among the 139 persons that ran 82 wore other types of clothing associated with commuting, working or other forms of casual dress (for example ). One could say that they were dressed as pedestrians that ran. The membership category devices of being dressed as a jogger was a collection of different materialities such as tight pants or shorts, headphones, cap or a woolen cap, colorful soft jackets, etc., that gave an overall impression of a person engaged in jogging. Thus, by looking at how the population was dressed we could identify joggers (for example ). Again, the members dressed as joggers were greater than the persons that ran while dressed as joggers, 89 persons were dressed as joggers but only 47 of them ran ().

Figure 2. (a) An example of a man dressed in ordinary clothing, running to the subway entrance. (b) An example of two persons both dressed for jogging that was walking along the street.

Table 1. A documentation of every person running passed the camera as well as those dressed in jogging-clothing. Grouped in 30 minutes interval. The people are divided into three categories (I) those that run dressed with normal clothing (pedestrians-that-run) (II) those that walk with jogging-clothing(joggers-that-walk); and (III) those that run with jogging-clothing (joggers).

We could, based on the membership category devices visible, speak of three membership categories: joggers, joggers-that-walk and pedestrians-that-run. While the pedestrians-that-run were doing-being-different they could by changing pace return into the production- and recognition-work of doing being-pedestrians. The joggers-that-walk on the other hand were doing being-different even though their pace was adjusted to the surroundings. Even though these three populations were small and not sufficient for quantitative calculations (a consequence of deliberately focusing on micro-minorities such as this paper does), the patterns that emerged in do show rhythms of difference and correspondence between the populations. Joggers and pedestrians-that-run don’t share the same rhythm of participating on the busy street, but the joggers and the joggers-that-walk do. Pedestrians-that-run had a peak in between 8 and 10:30 whereas joggers and joggers-that-walk became more visible from 17:30 to 20. These rhythms could be an indication that joggers-that-walk and joggers more likely are the same membership category whereas pedestrians-that-run belongs to other membership categories of the street. As a jogger, you do not have run continuously. You can stop, walk and run by your own accord. For example, a jogger passed the camera, as he came close to a group of pedestrians he started to walk until the he came to a crossing, where he started to run again and turned left. Joggers could walk to a park or to other more suitable urban grid than a busy urban street as Götgatan in order to do recreational mobility. The location of the camera was only a small part of the urban setting where running was possible. Hence, we can draw the conclusion that the urban setting was inhabited by more joggers than those we will focus on. However, that people jogged on a busy street, a place not suited for this activity, still remains fascinating considering that they could easily avoid this by walking over to more suitable locations.

In doing-being-different: joggers on a busy street

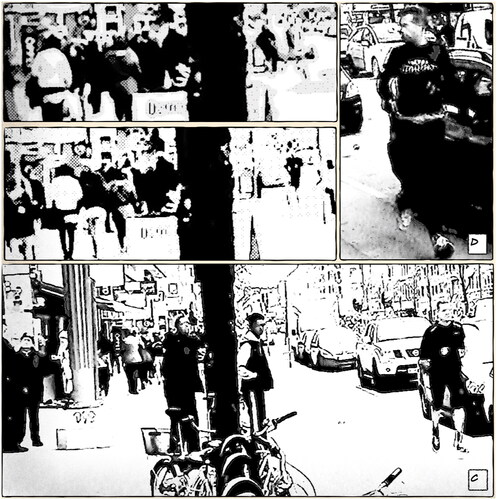

In the following, we will focus on the 47 cases that include both the practice of running with the clothing of jogging. The significant difference between jogging and walking was the speed or pace; a jogger will therefore potentially pass other walkers as she or he runs. Therefore, the crowding on the street was of particular importance when jogging (Alrabadi Citation2020). One way to avoid crowding was to do jogging when the street was used by only a few pedestrians (), and depending on the joggers’ experiences of running this was of course possible (what ethnomethodologists would call ‘documents of’ from previous jogging routes). Another possibility was to move from the pavement over to the cycleway and use this space that had another rhythm of ‘crowdedness’. This practice was particularly common during the afternoon and evening and 20 joggers (out of 47) ran on the cycleway instead of the pavement (). For example, we can see a difference between the two occasions in regarding the number of pedestrians using the sidewalk, as an example of potential risk of pedestrians being in-the-way. Moving to the cycleway also shifted the role of the jogger that instead of passing slower pedestrians was overtaken by faster cyclists. One could argue that for this group of joggers, it was easier to be in-the-way of cyclists rather than having to navigate between all pedestrians on the sidewalk (Normark Citation2021). Furthermore, using the cycleway was possible as they encountered a crowded street; the choice was not necessarily planned but an adaption to the situation. While many pedestrians, dog-walkers and other membership categories on the street temporarily occupied the cycleway, this ‘breach’ was significant for the joggers. Out of the 47 persons that were jogging, 43% of them used the cycleway, making this space a jogging-lane along the busy street.

Figure 3. (a) A jogger out in the early morning commute, on an almost empty street. (b) A jogger using the cycleway in a time when the road is more occupied and crowded.

The examples show that the cycleway was part of the membership categorization devices that joggers deliberately used to differentiate themselves from the cohort of pedestrians – they were something else – cyclists on feet even. This could be seen as performing a deliberate alterity – a production-work of doing-being-different. They othered themselves by making use of this additional space as part of their deviation from the norm and the normal among pedestrians on Götgatan. This production-work of doing-being-different in turn led to a negotiation between cyclists and joggers. When looking at those occasions, we could identify two tactics of negotiation: either the jogger ran to the far left of the street, as close to the parked cars as possible (as seen in ), or they ran close to the trees that separated the sidewalk and the cycleway ().

Figure 4. (a–c) From an occasion when the jogger used the space between the parked cars and the cycleway to avoid being in the way of cyclists while not having pedestrians in the way of the jogger. In c), there are also two onlookers that observe the jogger. (d) another similar occasion where the jogger temporarily looks back while jogging in the space between the parked cars and the cycleway.

In the examples visualized in , we can observe that the practice of running as close to the car traffic was initiated as the jogger in arrived at Götgatan. He ran out onto the cycleway and over to the right side. In he even rounded a traffic sign with information regarding the carpark in order to not be in the way. Still, that narrow part of seldom-used road provided a liminal area where the jogger could maintain a high pace and he passed the camera quickly. In , another jogger acted similarly but the Figure also revealed that the decision to run at that place required attentive awareness of the cyclists that might sneak up on you from your right-hand side. The ones jogging on the right side of the cycleway were overtaken in more traditional fashion as if they were a slow bike, thus being in a larger degree a slow-moving-cycle on two legs.

The practice of running on the sidewalk required another form of coordination and doing-being-different, as reveals. In the example, we followed a tall man running wearing a red cap that made it easier to follow his movement through the crowd even before passing the camera. The man with the red cap was using the entire width of the sidewalk between the buildings and the trees. Through the dense population of heads, the red cap moved from the left to the right again and again, avoiding collisions by moving away from the directions that other pedestrians were heading. Following his movement, as in , showed that it was the jogger that had to adapt to the other pedestrians. The jogger was doing-being-different and thus, he had to create new paths by changing directions to avoid running into someone. In many ways it resembled the practice of jogging in a forest where you have to avoid trees in your path. But for the jogger on Götgatan, these ‘trees’ were also moving, requiring a high degree of adaptation and adjustment. When he approached the camera, we could see how he zigzagged as he passed a large pillar (that showed the entrance for the subway) on the left side, then changing direction to run on the right side of a pedestrian that he met. He then altered his direction again to the left as he encountered two women walking. After passing them, he immediately shifted again to the right as he got very close to parked cycles just before passing the location of the camera. This back-and-forth movement adapting to all the other pedestrians can also be regarded as production-work of doing-being-different, doing alterity. These examples show the adaptability of joggers moving between the sidewalk and the cycle-way as well as other ‘just-thisness and just-hereness of jogging’ (haecceities).

Nested mobility: for dog-walkers and joggers

Having in this article described two purposeful modes of mobility, the recreational mobility of dog-walking and the recreational mobility of jogging, we will in the following question these categories as they also can be part of other equally purposeful activities of mobility. As humans we seem to be more heterogeneous than the taxonomy or the membership categories affords. The assumption that the studied occasions reveal multiple objectives is, as in the entire article, based on what can be observed in the video. For example, studies on consumer logistics explicitly used the different types of container technologies as indicators for shopping (Normark, Cochoy and Hagberg Citation2019; Calvignac and Cochoy Citation2016). Thus, the combination of jogging-clothes and shopping bags () or shopping bags and dog () reveal the merger of membership categories of jogging and shopping mobility or dog-walking and shop-walking. More explicitly, among the dog-walkers we could observe: 14 personal bags, 7 backpacks and 17 shopping bags. That dog-walkers possibly conducted shopping as well was confirmed by one occasion where a dog-walker passed the camera without bags and afterwards passed again with a shopping bag walking in the opposite direction. Other occasions of nested dog-walking mobility included mobile-phone talking, carrying a newspaper and posting a letter.

Figure 6. (a) A woman with shopping-bags and a dog. (b) A man dressed as a jogger carrying two distinctive blue shopping-bags. (c) A jogger running with a backpack.

Joggers did not display as large array of heterogeneousness in regard to observable container technologies (Sofia Citation2000, Calvignac and Cochoy Citation2016). However, two joggers-that-walked carried bags () and seven joggers carried backpacks (), five of whom were running – maybe these joggers were running as part of their commute? The time when they ran opened up for that possibility, and membership categories are not exclusive in that sense. Two instances also combined joggers and dog-walkers with another technology – strollers. For example, an assemblage passed the camera consisting of a father, two children, a stroller and a dog. The dog was playful and one of the children was walking beside the stroller, perhaps more difficult to keep connected to than the dog on a leash. With two available hands the father steered the stroller while pulling the dog-leash. These hybrids, or families enacted on the street, reveal another dimension of nested mobility – that such assemblages can consist of more than one human body but still move and exist as one sutured cogency – and this nestedness affects the labeling of recreational or utilitarian mobility. These occasions could be both and neither.

These instances of dog-walkers and joggers reveal that they are part of a nested mobility – the recreational mobility is entwined in other purposes and mobilities such as commuting or shopping. The examples show that mobility, and urban mobility in particular, is a heterogeneous activity that consists of recreational mobility as well as childcare mobility or commuting or shopping mobility. The taxonomies in mobility studies cannot be created with strict boundaries.

Conclusion

A careful observation of a day in a busy street’s life provides an alternative approach to categorizations of mobility, especially for marginal practices such as recreational mobility. Analyzing all the situations when dog-walkers or joggers passed the camera provided insights into the production- and recognition-work of doing recreational mobility. We could show that recreational mobility is not only confined to places of recreation (as studied by Qviström Citation2016, Citation2017). Recreation is part of everyday life and can be enacted even on a busy street. But this work is not only the performance of the individual (highlighted through the sensuous impressions that the joggers experience, see Cook, Shaw, and Simpson Citation2016, Collinson Citation2006, Larsen Citation2019). It is also a collaboration between those that participate in recreational mobility and those that witness it. Yet, as it is collaborative it is also situational, and the form of recreational mobility that is enacted on a busy street is not the same as recreational mobility on a track and fields.

Doing being-jogging and doing being-dog-walking are simultaneously doing being-not-ordinary. This alterity is the ‘just thissness’ that distinguishes recreational mobility on a busy street from other forms of recreational mobility. As a practice, it is enacted in a way to show that it is not really in the right place. This was particularly apparent in the production-work that joggers did: using the cycleway, running close to the parked cars as if they were cyclists with feet rather than pedestrians or zigzagging through the forest of pedestrians. This also shows that the membership categories of being a jogger, for example, is not only the accomplishment of the individual but a result of the situation and those co-present in the production- and recognition-work. Hence, in order to understand recreational mobility, we have to see how it is enacted and uncover how spatiality, materiality and other co-present humans collaboratively accomplish this work.

This article is also a methodological experiment. What can we observe by using a camera and how can that be used to inform on the membership categories that occupy the street? Whereas quantitative approaches rely on representativity through numbers, our study focuses on the odd and unfamiliar cases within a situation in order to highlight that which is overlooked. By observing the small cohorts, we still could recognize similarities and differences. These should not be equated with representative patterns, but rather membership category devices in themselves that reveal how we make our production- and recognition-work in the first place. But, using this approach to study recreational mobilities along a busy street provides ambiguous conclusions.

Finally, the findings on recreational mobility were ambiguous in regard to the taxonomy itself, considering that recreational mobility was nested with other equally valid iterations of mobility such as shopping, working, commuting, parenting etcetera. Mobility is a multi-teleological heterogenous practice, where recreational mobility is one (of many) valid reason nested in other valid purposes, which also makes it difficult to govern, as showed for example by Kaaristo et al. (Citation2020). Further research on the nestedness and heterogenous character of everyday mobility is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Who in turn was inspired by the phenomenologist Husserl’s use of the same word (see Husserl and Melle (Citation2008)).

2 As Law (Citation2004) points out – new methods, despite their virtues, will still other and make things othered, and a drawback of the growing use of video cameras is the subsequent ocularcentrism that it feeds, pushing out other senses such as smell, touch and taste from the ethnographic accounts. For a more sensuous ethnography, see Pink (Citation2015).

3 This division has many names and roots, stemming for example back to the debates between Gabriel Tarde and Emile Durkheim (Vargas et al. Citation2008). Garfinkel and Rawls (2002) refers to a misunderstanding of Durkheim’s aphorism – that social science at large has confused explananda with explanandum.

4 For instance, there was only one observation with a man walking with a cage for a cat, even though we might expect that the human-cat assemblages are far more common in Södermalm than represented by this single individual.

References

- Alrabadi, Sahar. 2020. “Crowdability of Urban Space: Ordinary Rhythms of Clustering and Declustering and their Architectural Prerequisites.” PhD diss., Lund University, Lund.

- Bates, Charlotte. (ed.). 2015. Video Methods: social Science Research in Motion. New York: Routledge.

- Bates, Charlotte., and Kate Moles. 2023. "Immersive Encounters: Video, Swimming and Wellbeing.” Visual Studies 38 (1): 69–80.

- Bull Jacob, Tora Holmberg and Cecilia Åsberg. (eds.,) 2018. Animal Places: Lively Cartographies of Human-Animal Relations. 1st ed. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Büscher, Monika. 2006. “Vision in Motion.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 281–299. doi:10.1068/a37277.

- Büscher, Monika, and John Urry. 2009. “Mobile Methods and the Empirical.” European Journal of Social Theory 12 (1): 99–116. doi:10.1177/1368431008099642.

- Büscher, Monika, John Urry, and Katian Witchger. 2010. Mobile Methods. London: Routledge.

- Calvignac, Cederic, and Franck Cochoy. 2016. “From 'market Agencements’ to 'Vehicular Agencies’: Insights from the Quantitative Observation of Consumer Logistics.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1): 133–147. doi:10.1080/10253866.2015.1067617.

- Cochoy, Franck, Johan Hagberg, and Roland Canu. 2015. “The Forgotten Role of Pedestrian Transportation in Urban Life: Insights from a Visual Comparative Archaeology (Gothenburg and Toulouse, 1875–2011).” Urban Studies 52 (12): 2267–2286. doi:10.1177/0042098014544760.

- Collinson, Jacquelyn Allen. 2006. “Running-Together: Some Ethnomethodological Considerations.” Ethnographic Studies 8: 17–29.

- Cook, Simon, John Shaw, and Paul Simpson. 2016. “Jography: Exploring Meanings, Experiences and Spatialities of Recreational Road-running.” Mobilities 11 (5): 744–769. doi:10.1080/17450101.2015.1034455.

- Cooren, Francois. 2009. “The Haunting Question of Textual Agency: Derrida and Garfinkel on Iterability and Eventfulness.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 42 (1): 42–67. doi:10.1080/08351810802671735.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2008. “Alterity/Identity Interplay in Image Construction.” In The SAGE Handbook of New Approaches in Management and Organization, edited by Daved Barry and Hans Hansen, 49–62. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2013. “Negotiating Selves: Gender at Work.” Tamara Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry 11 (1): 59–72.

- D'Andrea, Anthony, Luigina Ciolfi, and Breda Gray. 2011. ”Methodological Challenges and Innovations in Mobilities Research.” Mobilities 6 (2): 149–160. doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.552769.

- Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity.

- Garfinkel, Harold, and Aane Warfield Rawls. 2002. Ethnomethodology’s Program: Working out Durkeim’s Aphorism. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Gibson, James Jerome. 1977. “The Theory of Affordance.” In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology, edited by Robert Shaw and John Bransford, 62–82. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gibson, James Jerome. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co.

- Goertz, Gary, and James Mahoney. 2012. A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Goffman, Erving. 1966. Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings (1. Free Press paperback ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Heath, Christian, Jon Hindmarsh, and Paul Luff. 2010. Video in Qualitative Research: Analysing Social Interaction in Everyday Life. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Herrstedt, Lene. 1981. Fodgaengertrafik i byområder. [Pedestrian traffic in Cities] Lyngby: Institut for Veje, Trafik og Byplan.

- Holmberg, Tora. 2015. Urban Animals: Crowding in Zoocities (1st ed.). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Husserl, Edmund, and Ullrich Melle 2008. Introduction to Logic and Theory of Knowledge: Lectures 1906/07. Dordrecht :Springer.

- Instone, Lesley, and Kathy Mee. 2011. “Companion Acts and companion species: boundary transgressions and the place of dogs in urban public place” In Animal Movements. Moving Animals. Essays in Direction, Velocity and Agency in Humanimal Encounters, edited by Jacob Bull, 229–250. Crossroads of Knowledge No. 17, Uppsala: Centre for Gender Research, Uppsala University.

- Kaaristo, Maarja, Dominic Medway, Jamie Burton, Steven Rhoden, and Helen L. Bruce. 2020. "Governing Mobilities on the UK Canal Network.” Mobilities 15 (6): 844–861. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1806507.

- Larsen, Jonas 2019. “Running on Sandcastles: Energising the Rhythmanalyst Through Non-Representational Ethnography of a Running Event.” Mobilities 14 (5): 561–577. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1651092.

- Laurier, Eric. 2014. “Capturing Motion: Video Set-Ups for Driving, Cycling and Walking.” In The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities, edited by Peter Adey, David Bissell, Kevin Hannam, Peter Merriman and Mimi Sheller, 493–502. London: Routledge.

- Laurier, Eric. 2019. “Civility and Mobility: Drivers (and Passengers) Appreciating the Actions of Other Drivers.” Language & Communication 65: 79–91. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2018.04.006.

- Laurier, Eric, Barry Brown, and Hayden Lorimer. 2012. “What it Means to Change Lanes: Actions, Emotions and Wayfinding in the Family Car.” Semiotica 2012 (191): 117–135. doi:10.1515/sem-2012-0058.

- Laurier, Eric, Ramina Maze, and Johan Lundin. 2006. “Putting the Dog Back in the Park: Animal and Human Mind-in-Action.” Mind, Culture and Activity 13 (1): 2–24. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1301_2.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method: mess in Social Science Research. 1st ed. London: Routledge

- Law, John., and John Urry. 2004. “Enacting the Social.” Economy and Society 33 (3): 390–410. doi:10.1080/0308514042000225716.

- Liberman, Kenneth. 2013. More Studies in Ethnomethodology. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Liberman, Kenneth. 2019. “A Study at 30th Street.” Language & Communication 65: 92–104. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2018.04.001.

- Lloyd, Michael. 2020. “Getting By: The Ethnomethods of Everyday Cycling Navigation.” New Zealand Geographer 76 (3): 207–220. doi:10.1111/nzg.12274.

- Lynch, Michael. 1993. Scientific Practice and Ordinary Action: Ethnomethodology and Social Studies of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McGahern, Una. 2019. “Making space on the run: exercising the right to move in Jerusalem.” Mobilities 14 (6): 890–905. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1626082.

- McHugh, Susan. 2004. Dog. London: Reaktion Books.

- McIlvenny, Paul, Mattias Broth, and Pentti Haddington. (eds.). 2014. “Moving Together: Mobile Formations in Interaction.” Special Issue in Space and Culture 17 (2): 104–106.

- McIlvenny, Paul. 2015. “The Joy of Biking Together: Sharing Everyday Experiences of Vélomobility.” Mobilities 10 (1): 55–82. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.844950.

- Michael, Mike. 2000. Reconnecting Culture, Technology, and Nature: From Society to Heterogeneity. London: Routledge.

- Normark, Daniel, Franck Cochoy and Johan Hagberg. 2019. “Funny Bikes: A Symmetrical Study of Urban Space, Vehicular Units and Mobility through the Voyeristic Spokesperson of a Video-Lens.” Visual Studies 34 (1): 3–27.

- Normark, Daniel. 2021. “Pitstops and Liminal Spaces – the Usefulness of Uselessness.” In: Tillämpad Stadsbyggnad, Nationellt möte 2020, edited by Ann Lege. [Applied Urban Design].

- Pink, Sarah. 2008. “An Urban Tour: The Sensory Sociality of Ethnographic Place-Making.” Ethnography 9 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1177/1466138108089467.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography (2nd ed.). London: SAGE.

- Pollner, Melvin. 1974. “Sociological and Common-Sense Models of the Labelling Process.” In Ethnomethodology, edited by Roy. Turner. Harmondsworth: Penguin

- Qviström, Mattias. 2016. “The Nature of Running: On Embedded Landscape Ideals in Leisure Planning.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 17: 202–210. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2016.04.012.

- Qviström, Mattias. 2017. “Competing Geographies of Recreational Running: The Case of 'Jogging Wave’ in Sweden in the Late 1970s.” Health & Place 46: 351–357. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.12.002.

- Qviström, Mattias, Linnea Fridell, and Mattias Kärrholm. 2020. “Differentiating the Time-Geography of Recreational Running.” Mobilities 15 (4): 575–587. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1762462.

- Redmalm, David. 2013. “An Animal Without an Animal Within. The Powers of Pet Keeping.” PhD diss., Örebro University, Örebro.

- Ryave, A. Lincon, and James N. Schenkein. 1974. “Notes on the Art of Walking.” In Ethnomethodology, edited by Roy, Turner. Harmondsworth: Penguin

- Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1992. Lectures on Conversation. Vol. 2. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

- Silverman, David. 1998. Harvey Sacks: Social Science & Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Sofia, Zoe. 2000. “Container Technologies.” Hypatia 15 (2): 181–201. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2000.tb00322.x.

- Tarde, Gabriel. (1893) 1999. Monadologie et sociologie [Monadology and Sociology]. Paris: Institut Synthélabo.

- Vannini, Phillip. (ed.) 2009. The Cultures of Alternative Mobilities: Routes Less Travelled. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Vannini, Phillip. 2017. “Low and Slow: Notes on the Production and Distribution of a Mobile Video Ethnography.” Mobilities 12 (1): 155–166. doi:10.1080/17450101.2017.1278969.

- Vannini, Phillip. (ed.). 2020a. The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

- Vannini, Phillip. 2020b. “Introduction.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video, edited by Phillip Vannini. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Vargas, Eduardo Viana., Bruno Latour, Bruno Karsenti, Frédérique Aït-Touati, and Louise Salmon. 2008. “The Debate Between Tarde and Durkheim.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26 (5): 761–777. doi:10.1068/d2606td.

- Whyte, William Hollingsworth and Paco Underhill. (ed.) [1988] 2009. City: Rediscovering the Center. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Weilenmann, Alexandra, Daniel Normark and Eric Laurier. 2014. “Managing Walking Together: The Challenge of Revolving Doors”. Space and Culture 17(2): 122–136.