Abstract

Many universities are transforming campuses by responding to globally significant, locally specific, economic, political, and social imperatives. Some are implementing urban and regional transformations in higher education delivery to increase student access and diversity. Their success can depend upon infrastructures provided by other parties. Public transport is an example. Transit accessibility and equity affect quality of life, livelihoods, life course, and liveability in cities. Growing numbers of international studies consider factors shaping student travel to and from university campuses by public transport; fewer address local socio-spatial experiences of travel. Informed by debates about differential accessibility of suburban and city campuses, we examined student experiences at an Australian regional university undergoing transformation. We report on a study assessing multiple trips to and from two campuses to five destinations. Rich insights were drawn from experiences of antisocial behaviour, vulnerability, and sub-optimal service provision and reveal why some students think public transport is a mode of last resort. Universities and their stakeholders need to know more about student experiences of mobility. Such knowledge could inform tailored transport interventions and universities’ willingness to encourage public transport providers to view their services as infrastructures of care.

1. Introduction

Experiences of travel profoundly affect lives and shape communities, and can exacerbate a sense that mobilities systems are uncaring when they need not be. Relations of care matter (Wiesel, Steele, and Houston Citation2020). One’s postcode affects life course outcomes and configures access to goods, services, employment, housing, healthcare, recreation, and education. Disparities in access to education then affect livelihoods, social capital, life-chances, and wellbeing. That observation pertains to both compulsory schooling and higher education.

Higher education is a focus in this paper because university attendance has consequences for what is often called ‘upward [social] mobility’ – individual and community prosperity. Education also has consequences for international, interstate, and intrastate mobilities. Social mobility is thus contingent on spatial mobility and access to safe, especially reliable and effective public transport, on which we focus here. Like other urban services and infrastructures, public transport is increasingly recognised as an ‘infrastructure of care’ integral to city life.

Placing ‘care’ into ideas about and practices affecting infrastructure is crucial because infrastructure does not stand outside our lives (Star Citation1999). People’s use of infrastructure is embodied, embedded, and habitual; learned and taken-for-granted; responsive to disruption; and multiscalar and multitemporal. On that very basis, Alam and Houston (Citation2020, 1) observe that infrastructures have material and social dimensions; as ‘political, performative and relationally constituted’ structures and practices, they shape life chances. In a similar vein, so does Bissell (Citation2018) in work reflecting deeply on the ethnographic and spatial elements of ‘transit life’. Thinking of infrastructures ‘care-fully’ exposes how they enact and instantiate privilege, power, inequality and oppression (Kathiravelu Citation2021).

Our broad argument is that university leaders and other stakeholders in communities of place and interest need to know both how experiences of public transport affect students’ mobility practices and whether students experience those infrastructures as caring. In empirical work reported below, we ask what can be learned from experiences recorded as narratives by university students on bus trips to and from two university campuses? The knowledge gained could, we suggest, inform transport interventions. We examine such experiences in a growing, mid-size Australian city struggling to deliver safe and efficient public transport. We consider how one university’s efforts to increase access to higher education are contingent on students’ abilities to get to university for at least part of the curriculum. We consider how transport infrastructures affect students’ ability to prosper and flourish, mindful of how an ‘ecosystem of cities and public services’ shapes the ways that students access higher education (Dache Citation2022, 2). We think about how frictions in public transport affect enrolments, study patterns, and success rates and are complicated by varied delivery modes.

Ultimately, this research represents a preliminary study. Its chief outcomes have been to generate a better understanding of what can be learned from documenting narratives about experiences of bus travel to and from two university campuses, enabling evidential argument in support of trust, reciprocity, and transparency (Koekkoek, Van Ham, and Kleinhans Citation2021; Mason Citation2018). The balance of the paper outlines that literature and presents the study context, methods, findings, and discussion and conclusion.

2. Concepts and literatures

Public transport concerns individuals and communities and stakeholders in government, non-government, and private sectors. The capacity to be mobile is a function of individual characteristics, lived and shared experiences, and structural processes. Little wonder city governments grapple with population growth and ageing, urban sprawl, transport congestion, and other factors that constrain mobility, affect economic prosperity, and harm wellbeing. In Australia, for instance, substantial investment is required in transport infrastructure. Without ‘action, road and public transport congestion [costs] could double to nearly $40 billion by 2031’ (Infrastructure Australia Citation2019, 17). Such action means attending to other ways of being mobile, including walking, cycling, and ride sharing. But evidence-based decision-making for investment and funding requires more understanding of suburban and regional disparities and opportunities in public transport use. We consider three aspects in turn – public transport as an infrastructure of care, university transformations and public transport accessibility, and the role of im/mobility in access to higher education.

2.1. Public transport as an infrastructure of care

Networks on which public transport relies are typically classified as physical infrastructure. These networks are crucial for outcomes assigned to social infrastructure, such as health care, aged care, education, recreation, arts and culture, social housing, justice, and emergency services (Infrastructure Australia Citation2019). Yet, as Steele (Citation2017, n.p.) suggests, there is a need to think about what could be gained ‘from reframing critical urban infrastructure, like public transport, as “infrastructures of care”’ and about the benefits of ‘recasting social infrastructures in those terms’. Her points are neither semantic nor rhetorical. In debates about infrastructure the emphasis tends to be on things; we think it is vital to rethink them in terms of relations. In short, infrastructures invite opportunities to care with (Tronto Citation1993; see also Bissell and Fuller Citation2017; Power and Mee Citation2020; Truelove and Ruszczyk Citation2022; Williams Citation2017). The idea that caring with is foundational to ideas about infrastructures of care implicates how we move or not; where, when, and with what intentions and effects, or, ‘how lives are lived within and across the city and to consider the im/mobilities that characterise city life and the practice of care’ (Power and Williams Citation2020, n.p.). By extension, public transport is social as well as physical infrastructure, and, by the terms laid down thus far, an infrastructure of care – which is crucial in disruptive times.Footnote1

Disruption is also common to universities (Addie Citation2017, Citation2020; Johnson Citation2019). Some comparative studies suggest universities are responding to campus refinancing and redevelopment agendas in response to government and economic imperatives (McNeill et al. Citation2022; Walker and East Citation2018). Some show universities are testbeds of pedagogical, technological, or design innovations (De Medici, Riganti, and Viola Citation2018; Karvonen, Martin, and Evans Citation2018; Shen Citation2022). Others more focused on individuals in universities find that staff and students want to understand the effects of change on public transport and lifestyle practices (Menzie and Marcenko Citation2022). Certainly, experiences of public transport have been tempered by COVID’s effects (Bagdatli and Ipek Citation2022). Experiences are shaped by bus service upgrades or shortcomings (Byrne Citation2018); by the variable qualities of urban walkability (Stratford, Waitt, and Harada Citation2020; Waitt, Stratford, and Harada Citation2019); by the weather as it affects office and remote work and commuting (De Vet and Head Citation2020); or by aspirations for sustainable futures (Inturri et al. Citation2021). And they are shaped by higher education reform and its transport correlates (Olena and Andrzej Citation2021; O’Shea, Koshy, and Drane Citation2021).

Some studies focus on systems. Tsioulianos, Basbas, and Georgiadis (Citation2020, 13) emphasise how transport networks are inherently spatial and profoundly affect ‘mobility patterns, land use development, and … modal split, and thus the environmental footprint of transport systems’. They refer to systems’ complexities: urban space; spacing and number of stations and stops; routes; nodes; network density [stops within 10 minutes’ walk]; and network centrality [mean distance to nodes by mode of transport]. Such complexities affect overall commute times. Time and duration are likely the critical factors shaping public transport uptake, and are closely associated with driving and walking distances – with people’s appetites for the latter shrinking to less than 500 metres (p. 13).

2.2. University transformations, access to public transport, and care

Networks and systems are often instrumentally planned using the logics of physical infrastructure and econometrics, so how might a care-full lens influence such planning? In one study with 986 students from Laval University in Quebec, Canada, De Vos, Waygood, and Letarte (Citation2020) find that survey respondents wanted commute times below 20 minutes’ duration and often experienced public transport as inflexible, inconvenient, unpredictable, unreliable, boring, unsafe, unclean, and physically and psychologically uncomfortable. The authors suggest comfort and seating capacity would improve if there was ‘free Wi-Fi and power sockets on board’ (p. 96) but do not frame such provision in terms of infrastructure’s caring capacities, including in terms of outcomes such as embodied ease and digital equity. Likewise, Barr et al. (Citation2022) examine how to promote changes in travel behaviour and increase public transport uptake. They analyse insights from five workshops with commuters in Exeter, UK, which has both ‘chronic problems with commuting congestion during peak hours’ (n.p.) and large numbers of students in vocational and higher education. They focus on ‘private cars, public transport, walking, cycling, and a combination of modes’ (n.p.) in a survey and interviews. They note how, across workshops, people commented on public transport’s prohibitive costs, poor service quality, and unreliability, which – we think – can be read as uncaring.

In turn, Ly and Irwin (Citation2022) argue that university students in London, Ontario, Canada, are sub-optimally active for sound health and wellbeing outcomes, and they assume that most students could combine physical and mental health practices with transport practices. Time and distance are critical factors and weather a significant influence. In a pilot intervention, the authors produce point-of-choice or ‘behavioral prompts … posters or signs with informative health messages’ to shift intention to action (p. 183). An online questionnaire about those prompts asked 31,322 students if they had seen the posters, had any views on them, or had changed behaviours as a result. They received 346 returns – mostly from White females under 25 years of age living off campus who already walked or used buses. No account seems to have been taken of less mobile cohorts or multiple responsibilities that lead to complex trip requirements. Those responsibilities often increase among mature-age or higher degree students and inform motives and aspirations to study and deal with consequential complexities (Brailsford Citation2010; Spronken-Smith Citation2021).

2.3. Universities and im/mobilities

In higher education settings, immobilities gain expression in other ways, including in relation to fear, risk, sexual harassment, and victimisation. In one study, travel by 1,122 Stockholm university students on trains and the metro was partly shaped by the need to ‘avoid particular stations or routes at particular times’ (Ceccato, Langefors, and Näsman Citation2023, n.p.), a consequence of which is reduced choice, especially among females. The authors establish that ‘situational conditions are important for explaining precautionary behaviour’ and that diverse moral norms in place signal the extent to which criminal conduct is tolerated. Their findings prompt them to ask questions about ‘formal and informal social control’ mechanisms such as crime prevention by design measures or use of transport security guard services (n.p.).

Such measures can be understood as caring. Their deployment can also be poorly achieved or used to profile groups, as Dache (Citation2022, 1) establishes in work on the relation of location, income, race, and public bus services ‘between a Latinx urban neighborhood … from Rochester, New York, and college campuses’ in the city and suburbs. First, ‘public transportation and higher education [influence] … the economic mobility of people of colour … [but] external processes of college student access and enrollment … are rarely situated within the context of public transportation access’ (p. 2). Second, ‘public transit is largely invisible in efforts by researchers to understand local access to postsecondary institutions of higher learning’ (p. 2), despite transit and education privileging Whites. Dache uses QGIS to consider routes; wait times; wait environ characteristics; riding times; bus types; shelter types; and observations about passenger demographics. Bus systems do not cater for people wanting to travel outside city limits to access 4-year colleges and universities, and clean and comfortable commuting environs in wealthier White areas are ‘in stark contrast to bus areas and buses accessed by working-class, lower-income, Black, and Latinx people’ (p. 24). Third, long wait times represent ‘opportunity costs’ for people who have comparatively less access to ‘other technologies and services … [such as] cars, computers, high-speed internet … [that] contribute to educational and economic success’ (p. 24). Last, messaging on Latinx and Black routes were criminalising; those on White routes were oriented to college content. In short, ‘the public system of transportation is part of … racialized college access geographies’ (p. 25).

Work by Lades, Kelly, and Kelleher (Citation2020) examines links between transport and health and wellbeing at University College Dublin. Their study focuses on satisfaction levels arising from the most recent commute to the main campus among 4,134 staff and students. Their large cohort study partly deals with geospatial determinants of transport and shows that because the campus is in a privileged area, ‘travelers in affluent areas close to the campus more frequently use active travel modes’ (n.p.), and had higher levels of satisfaction and better chances to increase health and wellbeing.

Finally, in work providing a segue to our study, Kotoula et al. (Citation2018) examine how university campus decentralisation affects students’ mode choice at Democritus University of Thrace in Xanthi, Greece. There, university leaders decided to move operations from the city centre to a location five kilometres away. In 2018, three of five faculties had moved to the suburban location and two – with 1,000 students – were still in the city. Students in civil engineering at the new campus were selected for the study and, of 800 in the sample, 235 responded to a survey about sociodemographic characteristics and travel habits. Students were asked to rank factors affecting their travel choices. Between the old and new campuses, distance and time to reach destination remained top-ranked. But after the relocation, cost concerns emerged; the suburban campus is not easily reached on foot from the city where most students live, and public transport is not cheap. Comfort, socialising, environment, entertainment, and safety were of less concern. Those using public transport were then asked about their trips and invited to evaluate their experiences in terms of 13 qualitative factors across the whole of a trip’s duration.Footnote2 They found unsatisfying ‘routes frequency, comfort at the bus stop, bus capacity, cleanliness inside the bus, seat comfort, driver behavior, and passenger safety at the bus stop’ (p. 213).

With this background in place, next we consider both the context for our intrinsic case study and allied decisions about the research design and methods.

3. Context for the case study

Our research focuses on Greater Hobart, in Tasmania’s south, which comprises several local governments. More generally known as Hobart, it is Australia’s second-oldest capital city, and a mid-size city of c.259,000 people. Such small to mid-size cities are underrepresented in urban research (Kendal et al. Citation2020). In contrast to other Australian states and territories, Hobart’s population is also comparatively dispersed; just 44% of Tasmania’s population resides in Hobart itself in low-density suburbs of around 125 people per square kilometre.

Despite the city being first in the southern hemisphere with an electrified tram network, Hobartians are now car-dependent. After World War II, there were high rates of suburbanisation and, between 1965 and 1978, tram and rail infrastructures were removed in favour of buses. Public transport use declined from a peak of 34.4 million passenger journeys per annum in 1950 to 7.8 million passenger trips by 2013 (BITRE Citation2014). Only 5% of all journeys to work were by public transport in 2021. Of Australia’s major urban populations, Hobartians have the fourth worst access to public transport, and only 13% of residents live within 400 metres of a regularly serviced bus stop (BITRE Citation2021). Bus services such as Metro and Tassie Link are provided by the Tasmanian government and private operators, respectively. Some services to outlying suburbs run just twice a day. In a context of high employment, with an ageing and disillusioned driver workforce, and accounting for under-investment in public transport, up to 100 services per day can be cancelled.

Hobart is also the original location of Tasmania’s sole and Australia’s fourth oldest university – the University of Tasmania, founded in 1890. It has more than 31,000 students and 2,500 staff, multiple campuses in Tasmania, and a satellite in Sydney, New South Wales. The University is facing headwinds experienced across the sector: dwindling government funding, declining student numbers due to structurally ageing populations, and competition. In response, it is consolidating its footprints in a state-wide project of campus transformations in Hobart, Launceston in the north, and Burnie in the northwest; shifting suburban campus locations into central business districts; offering more courses online; upgrading student services and information technology; and redeveloping landholdings. Three principles inform these initiatives: improve accessibility to education, strengthen partnerships, and deliver sustainability outcomes (University of Tasmania Citation2022). And in Hobart, the public transport implications of the university’s city move are crucial considerations for campus transformation and any possibility of caring outcomes. They also inform public transport discussion embedded in allied debates about precinct, urban, and regional transport planning (City of Hobart Citation2021, Citation2022).

4. Research design and methods

The study’s intent has been to inform the university’s campus transformation projects. Planning for public transport is crucial for operations. But more – as refinements are made to organisational understandings of staff and students’ public transport practices and aspirations, we think it is crucial to acknowledge that everyday lived experiences shape our lives (Clayton, Jain, and Parkhurst Citation2017; Stradling et al. Citation2007).

However, gaps exist in understandings of qualitative and subjective components of bus travel to and from the university’s campuses; annual travel behaviour surveys do not always focus on those components (University of Tasmania Travel Behaviour Surveys Citation2013–2021). Thus, the qualitative research design was based on an understanding that knowledge is constructed and interpreted; there may be a world beyond our perceptions, but we access it through those perceptions and make meanings according to where we are literally and metaphorically placed. To aid rigour, we used mixed methods (Creswell Citation2013): observations, field trips and notes, and interviews. The work was authorised by the University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee [Project No. 27184] and subject to a formal risk assessment in our home School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences.

We sought to contextualise challenges faced by students who use public transport to access the university. The goal was to investigate what can be learned from experiences captured as rich or thickly descriptive narratives recorded by students using public transport to and from aforesaid campuses. In particular, we wanted to know whether there are locational variations in experiences of catching buses to and from university and whether some experiences of catching buses might contribute to perceptions of public transport as a mode of last resort (see Fitt Citation2018). Two doctoral candidates with fieldwork experience were employed to document their experiences taking public transport from those two sites to five outer metropolitan areas of Greater Hobart. We have assigned them the pseudonyms Jo and Alex and note that both live south of the CBD. On completion of all trips, they reflected on those experiences in an interview with us and those reflections were analysed and synthesised with the literature.

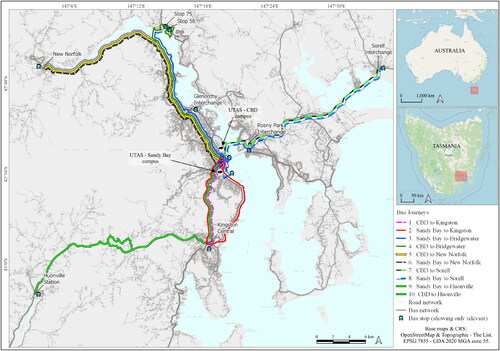

Jo and Alex documented their experiences on ten trips to and from Sandy Bay and Hobart CBD campuses at different times and days over three weeks between late March and early April 2022. They travelled to five outer metropolitan locations – New Norfolk, Bridgewater, Sorell, Kingston, and Huonville – and then back to Sandy Bay or the CBD (). All five are key sites of increased effort to raise educational attainment in compulsory schooling, and all could be more significant feeder locations for the university. Their distances from Sandy Bay and the CBD interested us, but we acknowledge that complex and time-consuming trips also characterise access to the university from inner suburbs poorly serviced by public transport.

Specifically, Jo and Alex observed and recorded trip dates, times, lengths, and durations; subjective observations about weather conditions; points-of-origin infrastructure; responses to bus conditions such as ambient noise, light, and temperature; transfer experiences; changes in conditions from one bus to another; and experiences of any activities or events on trips. They were not authorised to approach anyone for reasons related to the study but could take non-identifiable photographs, but that proved difficult in practice without seeming invasive.

When all trips were finished, we interviewed Jo and Alex for over an hour to learn more about each trip and about comparisons across all trips. The interview was then transcribed and analysed and, together with the field notes Jo and Alex took, was checked against findings from studies such as those reviewed in Section 2. Words are data and their use and sense and meaning were derived from their thematic analysis and an understanding of the power of discourse and story (Hajer Citation2006; Hajer and Law Citation2006; Hajer et al. Citation2010). We have been comprehensive in our analysis because we want to convey what we, as researchers, experienced working with Jo and Alex and writing up the findings: the labour of moving around Greater Hobart was, they said, exhausting, and the narrative is written exhaustively to echo that effect.

Limitations exist. The study is a snapshot in time, but every utterance has value in an intrinsic case study (Stratford and Bradshaw Citation2021). The study also involves some stratification by day and time but does not explicitly account for intersectionality – different forms of identity (Hopkins Citation2019). Indeed, the four of us speculated about what the ten trips might have been like under other conditions and thought about how they might have changed if other researchers with different sociodemographic characteristics or forms of identity had collected the primary data. Risk attends such speculation but diminishes where participants ‘are well positioned to actively and knowingly speculate with [researchers] … in our inquiry in ways that we cannot alone’ (Wakkary et al. Citation2018, 94). In short, all four of us have disciplinary understandings of intersectionality and think empathetically. Third, the study does not account for multimodal approaches to travel or complex and interrupted trips, including those from Hobart’s inner suburbs. Last, it captures student experiences of bus travel, but does not explicitly feature them having to reach classes or work in real time.

5. Findings

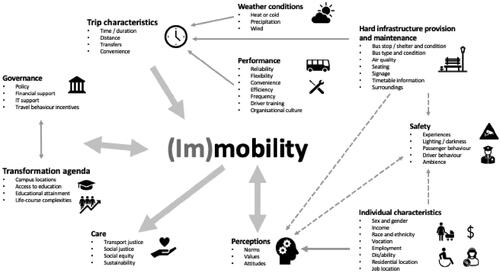

Below, findings from the data are presented primarily in narrative form and are contextualised in relation our goal to establish what can be learned from experiences captured as descriptive narratives by university students on bus trips to and from Hobart campuses. A conceptual framework that summarises the findings and synthesises them with the literature is provided in .

Trips started on 30 March and finished on 26 April, coinciding with some relaxation to COVID regulations – but not on public transport – and with Metro Tasmania’s short-term free bus experiment, two factors touched on briefly below. We have not considered the trips in relation to Jo and Alex’s perceptions of weather conditions but are aware that the weather significantly affects people’s perception of travel and public transport. With the exception of Kingston, when trips started in Sandy Bay, Jo and Alex still needed to go through the CBD to catch connecting buses. When trips started in the CBD, they often walked into the city together or met there. We have not recorded those preliminaries but note in passing that they added between eight and 40 minutes to the total experience.

In what follows, we consider each return trip on the understanding that lives accumulate from embodied geographies and the microspatial and micro-temporal choices we make or conditions we have to deal with each day. How our lives unfold matters, and understanding that point can be the difference between empathic and suboptimal transformation. In this sense, the findings are, themselves, a fly-through journey of experiences of transport around Greater Hobart from the perspectives of two individuals organised first by destinations and then by which trip the narrative relates to; because of that choice on our part, trips are not described in order.

5.1. Kingston

Trip 1 from the CBD to Kingston was on Wednesday 30 March 2022. Jo and Alex travelled from Hobart CBD to Kingston on an express service in just under 20 minutes from 10.08 am following a 15 minute wait at a roadside bus stop. The trip down the Huon Highway was direct and quick. After studying on the riverfront for a while, from 1.58 pm they took a return trip from Kingston Central, taking just over 20 minutes to get to the CBD, mostly along the same route.

When asked at interview about why they lingered in Kingston, Alex said, ‘we decided to actually try and … have an experience of studying and riding buses at the same time. So, we took a walk down to Kingston Beach just to clear our minds and do some study together’. She recalled that the return journey went through suburbs and, if marginally longer, was still straightforward. Of that trip, Jo said:

… we met a few people at the bus stop … unfamiliar with catching buses. A lot of people made comments about not having caught the bus for a long time [and about] being unsure about the travel timetables and things. So …that was an undercurrent throughout the journey … [with] a lot of new travellers on the bus because [Metro made transport] … free during the period we were travelling.

Trip 8 from Sandy Bay to Kingston was on Saturday 23 April, departing a shelterless bus stop in Sandy Bay with no timetabling or destination information. The trip took 20 minutes from 12.08 pm on one bus that wound through southern suburbs. As Alex recalled at interview:

There was no shelter and a little bench … was tucked in a hedge. That trip was a lot longer … and it was very windy. And I got quite … sick on the way there … And … yeah, it was actually more scenic … more beautiful. I remember us both noting it was a really nice trip as far as the landscape [was concerned] … But … you can just feel every corner.

Jo and Alex also noted that the route information referred to only two weekday buses on a weekday as having disability access, but that made little sense to them because other buses on other trips had full disability access. Either way, the system’s ambiguity was unthinking, unsettling, and could be read as uncaring.

5.2. Bridgewater

Trip 2 from Sandy Bay to Bridgewater was on Thursday 31 March. The outbound trip of eight minutes started for them at Sandy Bay Road into the CBD from 3.32 pm. There was a 15 minute wait in Elizabeth Street Bus Mall and another 40 minute express bus to Bridgewater from 3.48 pm. Because of COVID, wearing masks was mandatory but few complied.

The first bus was overfull and comprised mostly of school students, so Jo and Alex stood. Little happened on that leg, and in contrast, the second leg on the second bus was less full but the trip was confronting because they witnessed overt racism directed towards the bus driver by a mature female passenger accompanied by a young male. Jo and Alex felt very uncomfortable and thought other passengers seemed noticeably shocked at the passenger’s uncaring attitude. At interview, they said the following:

Jo: … we were on an express bus with fewer stops than usual. And a passenger was unhappy that the bus driver wasn’t stopping at the stop that they wanted to get off at because they didn’t realise it was an express, and another passenger “told them it’s an express and it doesn’t stop there”. They were trying to diffuse the situation and this other passenger proceeded to racially abuse the driver at length …

Elaine: And the bus driver …

Alex: South Asian …

Jo: I was worried for the bus driver … [but] he managed to diffuse it and he was incredibly calm and handled the situation very well, but he was clearly very frustrated and annoyed and had to resort to pulling over at a random spot in order to get this passenger off his bus. He said, “Get off my bus.”

Alex: Yeah. He said, “I’m not going to argue with you. Get off.”

The return journey departed across the street from the shopping centre and took 50 minutes from 5.15 pm. It included a seven-minute stop at the City Interchange, and then took in a second leg back to a university bus shelter on Sandy Bay that took 10 minutes from 6.13 pm. A man with three children on the bus seemed frazzled and Jo and Alex said there were several such occasions when they observed lone carers with children, during which:

Alex: They were having to gather their bags and the children and get off a packed bus, sometimes with a pram. It was just like a logistical nightmare … We saw with a dad with three kids and we [silently] applauded him at the end because he was keeping it together. These three kids were screaming, shouting, fighting and he was having to pick them up and put them on different seats and he kept his cool … it was taking a lot of emotional and mental labour, along with physical work …

three big dudes right in front of us, all unmasked … Felt intimidated but they were only on for a short amount of time … There was a learner bus driver—felt safer with two bus drivers to handle any situation. The supervisor kept handing masks to passengers … lots of people getting on the bus without them. He stopped at the Glenorchy Interchange to grab more. Bus was stuffy. Felt relieved when doors opened to get air flow … Went through the ‘burbs. Trip felt long. Shocked at the stark contrast in socio-economics compared with Sandy Bay.

5.3. New Norfolk

On the third trip on Thursday 7 April, Jo and Alex went to New Norfolk, an outbound journey that took over three hours. The bus from the City Interchange to the Glenorchy Interchange took 20 minutes from 1.20 pm but the scheduled 2.15 pm bus from there to New Norfolk did not arrive so their departure was delayed until 3.49 pm and it took 40 minutes to reach the township. Those delays would have been deeply disruptive had Jo and Alex been working to a tighter time frame.

In their field notes, Jo and Alex described how the ‘sun was fierce and although there was a bus shelter [in Glenorchy] the sun went straight into it and didn’t shade us’. Given the time of day, significant numbers of school students were present, and the bus felt ‘busy and crowded … too close to other passengers and stuffy’. They also recalled that one passenger ‘shouted aggressively at the bus driver’ when the latter braked sharply. Although there was police signage on the bus about zero tolerance for aggressive behaviour, that incident affected their sense of safety. In contrast, the coach from Glenorchy to New Norfolk was more spacious and well-ventilated. In our reading, there is much here about care and its lack: lack of design skills and sensibility; lack of preparation for warming urban environments; lack of civil and caring behaviour; lack of sense of safety, an outcome of caring.

The return express journey to the CBD was markedly different, departing from New Norfolk Central carpark and taking about 60 minutes from 4.53 pm. According to Jo and Alex, to get to the main street it was possible to follow the road around – probably five minutes on foot – but was quickest to traverse an alley with no lighting, and for them the effect felt uncaring and unsafe in ways that might affect their choices about how to attend university:

Alex: … it was daylight, but … I don’t know—you just notice those things when you feel unsafe all of a sudden. And I think that if it had been night-time, it probably would have been worse.

Elaine: How would you feel about the prospect of doing this trip regularly?

Jo: In winter, when it’s dark earlier—I guess people do what they have to do. If that’s the only way you can get places, then you have to put yourself in that position. But if you could, you’d probably like somebody to meet you at the end of the line to pick you up. You wouldn’t really want to have to walk home, particularly when it’s dark …

Alex: I think it depends if you were brought up in New Norfolk actually and –

Jason: Let’s suppose you had then.

Alex: It’s a small community. So, you might recognise more faces. But … if I was a 17-year-old getting on and off that bus and it was night, I don’t think I’d feel very comfortable, especially walking down the alleyway to the other side. It’s hidden, no lights, and I’d be pretty uncomfortable …

Jo: I probably wouldn’t go to campus if I could do uni online. I probably wouldn’t put myself through it … and if you’re by yourself, you’re on high alert … Doing it together was very different … and I would have had a totally feeling about safety if I’d been alone.

Alex: Yeah, I agree.

Kids on bus were shouting and being bratty, tearing open meat trays and throwing them around the bus stop. Bus was packed and guy with backpack kept knocking Jo in head … Mum with pram and toddler has lots of bags—took her awhile to get on and off. Bus driver was patient but [it seemed] … hard work navigating between people and gathering items and children to get on and off.

Jo: We had about 20 minutes at Glenorchy and we had that chap … trying to bum cigarette papers off us and … making comments about how we looked like hippy girls. … We were lucky there were two of us and it was broad daylight, and we didn’t feel unsafe … even though he was clearly drug or alcohol affected. And he got on our bus to New Norfolk. Then he got off the bus, and in that alleyway Alex was referring to before, he went and took a leak right in the alleyway that goes through to the shops. So, we were—it was mildly confronting, I suppose.

Alex: Yeah. And he actually offered us drugs when we were at the bus stop in Glenorchy.

5.4. Sorell

Trip 4 from the CBD to Sorell was a 40-minute journey on Monday 11 April from 4.00 pm. The bus arrived at the Sorell Bus Interchange seven minutes early and departed on time, and the journey ‘felt quick and easy’ (field notes). Again, few passengers were wearing masks, and most joined the bus at the interchange. Although it was not an express, there were few stops. Jo and Alex noted that the last bus to Sorell was at 6.00 pm, which they thought less than ideal for students in the event of late classes or extramural or employment activities after class. Alex said, ‘that made us a bit panicky. When we got on the bus, we were like, ‘Well, what’s the last bus to the city from Sorell?’ So we also had to think about that because we hadn’t really worried about it on a lot of our trips’. The return journey was from the same bus stop at Sorell Interchange, which had a lot of litter and broken glass, and felt uncared for. The duration was short – 35 minutes from 5.00 pm – and most passengers were young people going into the city. Jo and Alex saw dolphins in the river and were talking about it, for which they were mocked by one man and that ‘made us feel uncomfortable’.

Trip 7 from Sandy Bay to Sorell was on 22 April, departed from outside the Tasmanian University Union, and took 90 minutes. The first leg of 20 minutes from 1.10 pm went to the Rosny Park Interchange near a large, pleasant retail precinct on the inner eastern shore. There, Jo and Alex waited 46 minutes for the Sorell bus, which was a few minutes late. It departed at 2.13 pm and took about 30 minutes. Field notes described a ‘very full [bus] in the city on the way to Rosny. Most people masked. Different route from last time. Route was very long and did a lap at Midway Point [a peninsula]. 45mins from Rosny to Sorell. Less ventilation as it didn’t have back doors. Felt stuffy’.

The return journey was just under 90 minutes from 2.57 pm. The first leg to the City Interchange took about 50 minutes, and the second from there to Sandy Bay departed at 4.00 pm and took 15 minutes. Again, field notes point to a general sense of discomfiture: ‘Quick turnover. 2 buses. Very stuffy on way back. Lots of teens with music playing. Snuffling and girls with feet up on seats’. An emphasis on perceptions about safety was also apparent in these observations.

5.5. Huonville

Trip 5 to Huonville on Wednesday 20 April departed Sandy Bay from a shelterless stop and took 15 minutes from 2:48 pm, followed by 10 minutes at the City Interchange before the 30 minute journey south from 3.17 pm. The same route was used back to Sandy Bay.

The first leg from Sandy Bay into the CBD was very quiet – it was the Tuesday after Easter. The express bus from the CBD to Huonville had few occupants, and ‘felt fancier and safer. Smelt clean, [had] aircon and [was] less stuffy. Everyone was masked’ (field notes). Jo and Alex decided it ‘felt weird to go back down Davey [Street] and [be] so close to Sandy Bay but [we had] had had to go into city to then come back out. We used Google’s “our location” maps to navigate but we weren’t sure if [there] … was there a stop in walking distance’. They noticed the bus stop at Huonville is hidden behind buildings and poorly signed from the road, and could easily be missed. A solar-panelled shelter and rubbish bin were in place at what passes for the bus terminal, but timetables and bus signs were absent.

The return journey of 50 minutes started at 5.10 pm, followed at 5.50 pm by three minutes at the City Interchange – an uncomfortably rushed transition – and then by the final leg back to Sandy Bay, which took eight minutes from 5.53 pm. The first leg was in a ‘nice clean Tassie Link coach, radio on with music but pleasant. Only two people got on. Guy cracked [opened] what looked like alcohol but wasn’t bothersome and kept to himself at the back of the bus. Seemed friendly’ (field notes). Jo and Alex also thought the bus was much brighter than that used on Metro services. They noticed a QR code for real time bus tracking and the driver paused at one village for two minutes to wait and stay on schedule. On the final leg between the CBD and Sandy Bay, there were lot of people on the bus and a learner driver under instruction.

Trip 10, the last, took place on Tuesday 26 April. Jo and Alex caught a bus from Davey Street in the CBD after standing for about 35 minutes. The bus was on time at 12.10 pm and took about 40 minutes. The direct service provided by Tassie Link felt easy and safe but long because lots of stops were made. Jo and Alex ‘observed wholesome interactions between passenger and bus driver asking to stop at Woollies [shopping centre] “please” and him giving her a big wave and thumbs up. Coach dipped down for disability and pram access’ (field notes). The return trip of 50 minutes departed the same station at 5.10 pm and arrived in the CBD. Again, the bus made several stops along the route, including in Kingston. This leg also felt ‘quiet and felt safe despite being after dark’ (field notes).

6. Discussion and conclusions

Earlier, we observed that many universities around the world are having to respond to globally significant and locally specific pressures and working through major transformations. University staff and, for our purposes here, students are also members of larger communities in place, including urban settlements where public transport provision is usually a given. We think these two forms of physical and social infrastructure – the reorganisation of higher education and innovations to public modes of mobility – are infrastructures of care and need to be viewed as such in political, policy, and community contexts. We are not alone in doing so (Alam and Houston Citation2020; Power and Mee Citation2020; Power and Williams Citation2020; Wiesel, Steele, and Houston Citation2020; Williams Citation2017).

The University of Tasmania is gradually shifting suburban operations in Sandy Bay to Hobart CBD. Some have questioned the move, suggesting that relocating three kilometres down the road is unjustifiable. The university has inferred that the decision is not about Euclidean (linear) distance but about improving access to education for those from areas not traditionally part of its catchment, placements with employers, or innovation in design and high quality infrastructure, among other reasons. Its leaders are cognisant that Hobartians are highly car dependent (Mees and Groenhart Citation2014); that more than 80% of trips involve drivers or passengers in private automobiles (RACT Citation2022); and that residents have among the poorest levels of access to public transport characterised by high frequency, efficiency, reliability, and safety (Taylor and Fink Citation2013).

Inside those larger contexts are students’ everyday lives and experiences of catching buses, some of which have been documented here. Connections to Sandy Bay often have to be made by backtracking to the CBD, and we know from work we have in progress that over two-thirds of university staff and students live north and east of the CBD, not south of Sandy Bay. So the complications of connection can add more than an hour to the time it takes to move from origin to destinations such as the five we selected, which are target areas for improved educational access and attainment. Waiting times are often longer than 30 minutes, services can be cancelled with little notice, and conditions can be unpleasant because of weather, passenger interactions, lack of facilities and amenities, or poorly maintained infrastructure. A cancelled bus may mean missing critical university content or paid casual work – or both. For students with lower incomes who may not be able to afford or run private vehicles for long trips, the situations described above amount to transport disadvantage (Hine and Mitchell Citation2001).

Jo’s and Alex’s experiences are corroborated by other studies (Levin Citation2019; Mohammadzadeh Citation2020; Nguyen and Pojani Citation2023). Some show that transit accessibility and equity affect quality of life, livelihoods, and life course outcomes (Loukaitou-Sideris et al. Citation2020). Actions taken by governments and service-providers to improve public transit experiences can then improve public transport mode-share (Taylor and Fink Citation2013). That improvement can have flow-on benefits such as enhanced physical and mental health, lower levels of traffic congestion and air pollution, increased productivity, and better liveability in cities. If Jo’s and Alex’s experiences are commonplace, and anecdotal evidence suggest they are, steps taken to develop and refine access to public transport could benefit residents and visitors to cities and regions.

In effect, among expressions of care are those enabling access to higher education, including by means of public transport. Governments and transport providers need to ensure infrastructures are efficient and effective – and caring is often stated by them as an ethos and practice. Yet, Jo and Alex often experienced public transport as uncaring – and that pertained to both physical infrastructure (buses, bus stops, interchanges, surrounding areas) and to social infrastructure (stressed drivers, antisocial passengers, or others in local environs behaving likewise). Such outcomes are problematic in places such as Greater Hobart, where access to education and educational attainment outcomes and access to public transport are comparatively poor by national standards. These experiences are crucially important to take into consideration in any work that aims to improve both public transport itself and the relationship of public transport to participation in education.

Beyond these observations are other implications for mobilities studies. First, there is need for more studies of university students’ local and subjective experiences of public transport to augment larger, often quantitative studies. Second, it would be useful to test the extent to which conceptual frameworks that position physical and social infrastructures as integral to care could be applied to the sorts of qualitative studies we have in mind. Third, qualitative studies of student mobilities, when conceptualised in terms of infrastructures of care, could enrich other and increasing numbers of studies of university transformation at a time when students are among those in our populations experiencing high levels of precarity. Last, we wonder what beneficial philosophical, ethical, and practical outcomes might arise for diverse stakeholders in varied settings were public transport to be seen as both physical and social infrastructure and then as infrastructures of care. More grounded, experiential, qualitative, and real-time studies could, we think, assist with such tasks.

Ethical approval

The terms of the ethics clearance for this study involved undertakings about confidentiality and anonymity and subject to a data management plan but are not accessible.

Disclosure statement

The authors are professors in the School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences and are also seconded for a part of each week to Campus Futures in the the university’s Academic Division to undertaken transformation research.

Data availability statement

Information about data may be sought from the corresponding author.

Notes

1 We recognise, but here avoid, an argument can be made that all infrastructures are, in principle, about caring because they are about supporting life.

2 The variables are: (i) availability of trip information; (ii) service frequency; (iii) bus stop locations; (iv) walking time to bus stop; (v) waiting time at bus stop, (vi) comfort at bus stops; (vii) safety and security at bus stops; (viii) bus capacity; (ix) bus cleanliness; (x) seat comfort; (xi) safe driving; (xii) driver behaviour; and (xiii) safety and security inside buses.

References

- Addie, J.-P. D. 2017. “From the Urban University to Universities in Urban Society.” Regional Studies 51 (7): 1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1224334

- Addie, J.-P. D. 2020. “Anchoring (in) the Region: The Dynamics of University-Engaged Urban Development in Newark, NJ, USA.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 102 (2): 172–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2020.1729663

- Alam, A., and D. Houston. 2020. “Rethinking Care as Alternate Infrastructure.” Cities 100: 102662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102662

- Bagdatli, M. E. C., and F. Ipek. 2022. “Transport Mode Preferences of University Students in Post-COVID-19 Pandemic.” Transport Policy 118: 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.01.017

- Barr, S., S. Lampkin, L. Dawkins, and D. Williamson. 2022. “’I Feel the Weather and You Just Know’. Narrating the Dynamics of Commuter Mobility Choices.” Journal of Transport Geography 103: 103407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103407

- Bissell, D. 2018. Transit Life: How Commuting is Transforming Our Cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bissell, D., and G. Fuller. 2017. “Material Politics of Images: Visualising Future Transport Infrastructures.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (11): 2477–2496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17727538

- BITRE. 2014. Long-Term Trends in Urban Public Transport, Information Sheet 60. Canberra: BITRE, Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.bitre.gov.au/sites/default/files/is_060.pdf.

- BITRE. 2021. National Cities Performance Framework Dashboard. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.bitre.gov.au/national-cities-performance-framework/hobart.

- Brailsford, I. 2010. “Motives and Aspirations for Doctoral Study: Career, Personal, and Inter-Personal Factors in the Decision to Embark on a History PhD.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 5: 15–27. https://doi.org/10.28945/710

- Byrne, Jason. 2018. “Don’t Forget Buses: Six Rules for Improving City Bus Services.” The Conversation, May 2.

- Ceccato, V., L. Langefors, and P. Näsman. 2023. “The Impact of Fear on Young People’s Mobility.” European Journal of Criminology 20 (2): 486–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708211013299

- City of Hobart. 2021. Central Hobart Precincts Plan. Discussion Paper. Hobart: City of Hobart.

- City of Hobart. 2022. Public Meeting of 10 May: Notes on the Analysis of Submissions. Hobart: City of Hobart.

- Clayton, W., J. Jain, and G. Parkhurst. 2017. “An Ideal Journey: Making Bus Travel Desirable.” Mobilities 12 (5): 706–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2016.1156424

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=EbogAQAAQBAJ.

- Dache, A. 2022. “Bus-Riding from Barrio to College: A Qualitative Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analysis.” Journal of Higher Education 93 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1940054

- De Medici, S., P. Riganti, and S. Viola. 2018. “Circular Economy and the Role of Universities in Urban Regeneration: The Case of Ortigia, Syracuse.” Sustainability 10 (11): 4305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114305

- De Vet, E., and L. Head. 2020. “Everyday Weather-Ways: Negotiating the Temporalities of Home and Work in Melbourne, Australia.” Geoforum 108: 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.022

- De Vos, J., E. O. D. Waygood, and L. Letarte. 2020. “Modeling the Desire for Using Public Transport.” Travel Behaviour and Society 19: 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.12.005

- Fitt, H. 2018. “Habitus and the Loser Cruiser: How Low Status Deters Bus Use in a Geographically Limited Field.” Journal of Transport Geography 70: 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.06.011

- Hajer, M. A. 2006. “Doing Discourse Analysis: coalitions, Practices, Meaning.” In Words Matter in Policy and Planning: Discourse Theory and Method in the Social Sciences. Netherlands Geographical Studies, edited by M. van den Brink and T. Metze, 65–74. Utrecht.

- Hajer, M., and D. Law. 2006. “Ordering through Discourse.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, edited by M. Moran, M. Rein, and R. D. Goodin, 251–268. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M., S. A. van’t Klooster, J. Grijzen, and E. Dammers. 2010. Strong Stories: How the Dutch are Reinventing Spatial Planning. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Hine, J., and F. Mitchell. 2001. “Better for Everyone? Travel Experiences and Transport Exclusion.” Urban Studies 38 (2): 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020018619

- Hopkins, P. 2019. “Social Geography I: Intersectionality.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (5): 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517743677

- Infrastructure Australia. 2019. An Assessment of Australia’s Future Infrastructure Needs. The Australian Infrastructure Audit 2019. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/publications/australian-infrastructure-audit-2019.

- Inturri, G., N. Giuffrida, M. Le Pira, M. Fazio, and M. Ignaccolo. 2021. “Linking Public Transport User Satisfaction with Service Accessibility for Sustainable Mobility Planning.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10 (4): 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10040235

- Johnson, A. 2019. “The Roles of Universities in Knowledge-based Urban Development: A Critical Review.” International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 10 (3): 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijkbd.2019.103205

- Karvonen, A., C. Martin, and J. Evans. 2018. “University Campuses as Testbeds of Smart Urban Innovation.” In Creating Smart Cities (Chapter 8), edited by C. Coletta, L. Evans, L. Heaphy, and R. Kitchin. London; New York: Routledge.

- Kathiravelu, L. 2021. “Introduction to Special Section ‘Infrastructures of Injustice: Migration and Border Mobilities’.” Mobilities 16 (5): 645–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1981546

- Kendal, Dave, Monika Egerer, Jason A. Byrne, Penelope J. Jones, Pauline Marsh, Caragh G. Threlfall, Gabriella Allegretto, et al. 2020. “City-Size Bias in Knowledge on the Effects of Urban Nature on People and Biodiversity.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (12): 124035. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc5e4

- Koekkoek, A., M. Van Ham, and R. Kleinhans. 2021. “Unravelling University-Community Engagement: A Literature Review.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 25 (1): 3–24. https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/2643/2649.

- Kotoula, K. M., A. Sialdas, G. Botzoris, E. Chaniotakis, and J. M. Salanova Grau. 2018. “Exploring the Effects of University Campus Decentralization to Students’ Mode Choice.” Periodica Polytechnica Transportation Engineering 46 (4): 207–214. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPtr.11641

- Lades, L. K., A. Kelly, and L. Kelleher. 2020. “Why is Active Travel More Satisfying than Motorized Travel? Evidence from Dublin.” Transportation Research. Part A, Policy and Practice 136: 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.04.007

- Levin, L. 2019. “How may Public Transport Influence the Practice of Everyday Life Among Younger and Older People and How May their Practices Influence Public Transport?” Social Sciences 8 (3): 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030096

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., M. Brozen, M. Pinski, and H. Ding. 2020. “Documenting # MeToo in Public Transportation: Sexual Harassment Experiences of University Students in Los Angeles.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20960778

- Ly, H., and J. D. Irwin. 2022. “Skip the Wait and Take a Walk Home! The Suitability of Point-of-Choice Prompts to Promote Active Transportation Among Undergraduate Students.” Journal of American College Health 70 (1): 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1739052

- Mason, J. 2018. Qualitative Researching. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications. http://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/author/jennifer-mason.

- McNeill, D., M. Mossman, D. Rogers, and M. Tewdwr-Jones. 2022. “The University and the City: Spaces of Risk, Decolonisation, and Civic Disruption.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54 (1): 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211053019

- Mees, P., and L. Groenhart. 2014. “Travel to Work in Australian Cities: 1976–2011.” Australian Planner 51 (1): 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.795179

- Menzie, C., and D. Marcenko. 2022. “University of Tasmania’s CBD Move Incites a Diverse ‘Chorus of Voices’.” Togatus, May 8. https://togatus.com.au/2022/05/university-of-tasmanias-cbd-move-incites-a-diverse-chorus-of-voices/.

- Mohammadzadeh, M. 2020. “Exploring Tertiary Students’ Travel Mode Choices in Auckland: Insights and Policy Implications.” Journal of Transport Geography 87: 102788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102788

- Nguyen, M. H., and D. Pojani. 2023. “Why are Hanoi Students Giving Up on Bus Ridership?” Transportation 50 (3): 811–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-021-10262-9

- O’Shea, S., P. Koshy, and C. Drane. 2021. “The Implications of COVID-19 for Student Equity in Australian Higher Education.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 43 (6): 576–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1933305

- Olena, K., and K. Andrzej. 2021. “Comparative Analysis of Success in Higher Education in Ukraine and the USA.” Scientific Journal of Polonia University 42 (5): 78–87. https://doi.org/10.23856/4211

- Power, E. R., and K. J. Mee. 2020. “Housing: An Infrastructure of Care.” Housing Studies 35 (3): 484–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1612038

- Power, E. R., and M. J. Williams. 2020. “Cities of Care: A Platform for Urban Geographical Care Research.” Geography Compass 14 (1): e12474. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12474

- RACT (Royal Automobile Club Tasmania). 2022. Our Vision for the Future. Accessed 29 July 2022. https://www.ract.com.au/membership/related-articles/our-vision-for-the-future.

- Shen, J. 2022. “Universities as Financing Vehicles of (Sub)Urbanisation: The Development of University Towns in Shanghai.” Land Use Policy 112: 104679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104679

- Spronken-Smith, R. 2021. “Supporting Students to Complete Their Doctorate.” In The Future of Doctoral Research (Chapter 27), edited by A. Lee and R. Bongaardt. London; New York: Routledge.

- Star, S. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (3): 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

- Steele, W. 2017. “Infrastructures of Care.” Planning News 43 (7): 14. 10.3316/informit.981266609130522.

- Stradling, S., M. Carreno, T. Rye, and A. Noble. 2007. “Passenger Perceptions and the Ideal Urban Bus Journey Experience.” Transport Policy 14 (4): 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.02.003

- Stratford, Elaine, and Matt Bradshaw. 2021. “Rigorous and Trustworthy: Qualitative Research Design.” In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography. 5th ed. (Chapter 6), edited by I. Hay and M. Cope. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Stratford, Elaine, Gordon Waitt, and Theresa Harada. 2020. “Walking City Streets: Spatial Qualities, Spatial Justice, and Democratising Impulses.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (1): 123–138. 10.1111/tran.12337.

- Taylor, B. D., and C. N. Fink. 2013. “Explaining Transit Ridership: What has the Evidence Shown?” Transportation Letters 5 (1): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1179/1942786712Z.0000000003

- Tronto, J. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

- Truelove, Y., and H. A. Ruszczyk. 2022. “Bodies as Urban Infrastructure. Gender, Intimate Infrastructures and Slow Infrastructural Violence.” Political Geography 92: 102492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102492

- Tsioulianos, C., S. Basbas, and G. Georgiadis. 2020. “How Do Passenger and Trip Attributes Affect Walking Distances to Bus Public Transport Stops? Evidence from University Students in Greece.” Spatium 2020 (44): 12–21. https://doi.org/10.2298/SPAT2044012T

- University of Tasmania Travel Behaviour Surveys. 2013–2021. https://www.utas.edu.au/infrastructure-services-development/sustainability/transport/utas-travel-surveys.

- University of Tasmania. 2022. Transforming Our University. December 2022. https://www.utas.edu.au/about/campuses/transforming-our-university.

- Waitt, G., E. Stratford, and T. Harada. 2019. “Rethinking the Geographies of Walkability in Small City Centers.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (3): 926–942. 10.1080/24694452.2018.1507815.

- Wakkary, R., D. Oogjes, H. W. J. Lin, and S. Hauser. 2018. “Philosophers Living with the Tilting Bowl.” In Proceedings of The 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’18), Montreal, Quebec. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173668

- Walker, L. A., and J. F. East. 2018. “The Roles of Foundations and Universities in Redevelopment Planning.” Metropolitan Universities 29 (2): 33–56. https://doi.org/10.18060/22342

- Wiesel, I., W. Steele, and D. Houston. 2020. “Cities of Care: Introduction to a Special Issue.” Cities 105: 102844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102844

- Williams, M. J. 2017. “Care-Full Justice in the City.” Antipode 49 (3): 821–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/anit.12279