Abstract

This paper investigates the life experiences of creative expats and the associated impact of, and on, the built environment of their host localities. Grounded on participants’ testimonies, we develop the concept of transient mentality as a potential mediating factor in-between such reciprocal relations. Employing an interview and survey-based research approach and drawing on grounded theory for data collection and analysis in Beijing, China, we found that the prevalence of a transient mentality among creative expats is influenced by the nature of their occupations, the fluidity of their social relationships, and the rapid transformations in the built environment. This transient mentality, in turn, affects the production of the cityscape through the consumption preferences of these expats. We argue that understanding such a transient mentality is crucial for urban planning and cultural policy, particularly in (emerging) global cities that work to brand themselves as international creative hubs.

Introduction

The term ‘creative city’ has become a catchphrase for urban planners and city leaders around the world trying to boost economic growth and/or urban regeneration (Peck Citation2005). In this line of thought, cities are deemed as the ideal locus of creative production since they are special arenas of intercultural exchange, accumulation of knowledge, and clustering of skilled labor (Jacobs Citation1961; Glaeser Citation2012). In recent decades, globalizing flows of ‘talented migrants’ have reinforced this centrality, to a degree that the geography of these individuals coincided with that of global cities (Beaverstock Citation2002). In fact, these professionals are an integral part of the ‘space of flows’ in a networked society (Castells Citation2010), whose core resides in global (creative) cities (Sassen Citation2001). In this regard, we can say that they are part of what Florida (Citation2002) theorized as the ‘creative class’, a group of supposedly cohesive, highly mobile individuals who specialize in the novel combination of knowledge and ideas to solve problems or create value. Their main occupations are related to ‘technology creativity or innovation’, ‘economic creativity or entrepreneurship’, and ‘artistic or cultural creativity’ (Florida Citation2002; Mellander and Florida Citation2021), and they arguably make disproportionately high contributions to economic growth in such global creative cities.

Subsequent empirical studies on the creative class thesis focus on two topics. The first one concerns the ‘pull effect’ of soft factors. While Florida (Citation2002, Citation2005) and others (Zenker Citation2009; Kaplan and Fisher Citation2021; Mellander and Florida Citation2021) believe that creative workers are attracted to cities with ‘place-specific characteristics’ that foster talent, technology, and tolerance, critics argue that Florida’s theory romanticizes the increasingly precarious market of creative work and puts a disproportionate emphasis on soft conditions as a source of attraction (Peck Citation2005; Bontje and Musterd Citation2009; Murphy and Redmond Citation2009; Lawton, Murphy, and Redmond Citation2013; Bereitschaft Citation2017; Miao Citation2021). The other research thread pays attention to the acclaimed urban and regional growth effect of the creative agglomerations, yet the evidence has been mixed, if not predominantly missing (Donegan et al. Citation2008; Boschma and Fritsch Citation2009; Hoyman and Faricy Citation2009).

Many urban scientists and geographers attribute these ambiguous or inconclusive findings to the rather broad definition of ‘creative class’ and its lack of sensitivity to context (Bontje Citation2016; Kim and Cocks Citation2017; Lin Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Few, however, have moved beyond a generalized statistical, and arguably reductionist, analysis to explore the rich life experiences of creative workers as a potential explanatory reason – although migration and sociology studies have provided valuable insights in this regard (Meier Citation2014b). This research gap is particularly noticeable concerning international creative workers, who may best exemplify the creative class’s pursuit of mobility and lifestyle (Dávila Citation2012; Sleutjes and Boterman Citation2014; Bontje, Musterd, and Sleutjes Citation2017; Lin Citation2019b; Pitts Citation2020). They choose to migrate to another country for various reasons (Sleutjes and Boterman Citation2014), but macro-level systemic disparities in the international job markets and wages, alondside security and geopolitical issues, tend to attract these highly skilled workers to global cities (Beaverstock Citation2012), where they can expect better income and career prospects, along with their ‘transnationally orientated industrial structures and networks’ and cosmopolitan lifestyles (Beaverstock Citation2012, 248; Gatti Citation2009; Sleutjes and Boterman Citation2014). However, the literature hasn’t sufficiently explored how the interweaving of their life experiences with the social and built environments of host countries ultimately affects their understanding of reality (mentality) as creative expatriates.

Drawing insights from studies in philosophy, migration (Yeoh and Huang Citation2013; Wilczewski Citation2019; Farrer Citation2019) and sociology (Meier Citation2014b; Rocha Citation2015; Nunan Citation2018; Dashefsky and Woodrow-Lafield Citation2020), this paper addresses these gaps by investigating the personal experiences of creative expats and their impact on, and interaction with, the built environment. This study focuses on a case study of Beijing, China, where international talent attraction has become a key development strategy amidst rapid urbanization and economic development. By exploring these questions, we aim not only to shed light and to help to unpack further the black box of the creative class, providing a potential alternative explanation for the lack of quantitative evidence on causality, but also to contribute to urban studies by linking urban amenities and clustering activities through the eyes, the needs, and the feelings of the creative class.

The paper starts with an analytical framework that examines the transient mentality of creative expats in global creative cities. The methodology used in this work is then presented, followed by an empirical section on the forming of transient mentality, and how this, in turn, relates to creative expats’ relationship with the urban environment. The conclusion section summarizes the main findings and discusses the implications for urban planning and cultural policies.

Creative expats and their transient mentality

In this study, creative expats are treated as a sub-category within the large and diverse group of the creative class, defined as those expatriates working in the creative sectors. First, we broaden the meaning of expatriates used to describe those skilled white ‘westerners’ migrating by choice from developed to developing worlds in colonial literature (Howard Citation2009). Instead, we align with Hannerz (Citation1996) in defining them as those workers who are enmeshed in a global web of fluid identities, away from their home country and living transnational lives. While various socio-economic circumstances, even the lack of choice (e.g. unemployment, war, etc.), impinge on their ‘decision’ to migrate (Santos Citation2017), we acknowledge their agency in that they can also be ‘people who have chosen to live abroad for some period, and who know when they are there that they can go home when it suits them’ (Hannerz Citation1996, 106).

Regardless of their incentive to embark on this transnational journey, we consider, however, that local and individual factors in the host country may jeopardize (or facilitate) their autonomy to decide and plan their careers. For instance, visa regulations in countries like China, which do not permit long-term work status for most immigrants, create a state of uncertainty regarding their length of stay (one of our participants is required to renew his work visa yearly, despite being married to a Chinese citizen and living in China for over twenty years). Understanding them as a ‘category of practice’ (Farrer Citation2019), we assume expatriates to be, therefore, highly context-dependent.

Secondly, by emphasizing their employment status as creative workers, we differentiate these expats from ‘lifestyle migrants’ who migrate mainly for enhancing their quality of life instead of work (Benson and O’Reilly Citation2009). Lastly, our focus on their creative occupations, as defined in Florida (Citation2002), sets this group apart from those employed in labor-intensive and mass-manufactured jobs such as catering, wholesale, and textile, as profiled in Gardner (Citation2010) and Gong (Citation2016).

In essence, creative workers generate value by inventing and/or innovating new knowledge and ideas – although the process of ‘creation’ in neoliberal capitalism has been seriously questioned (Mould Citation2018). In this vein, mentality, as the characteristic way in which one thinks and conceives the reality they live in, plays a crucial role for creative workers to bridge their internal-external explorations. To Florida (Citation2002), for instance, the creative ‘lifestyle mentality’ is a unique feature of the creative type, one that shapes their preferences toward experiences that cultivate their creative impulses. This concept of creative mentality that Florida’s theory inherits has been heavily criticized for framing mentality as an individualized (and individualist) construction of reality (Franklin Citation2023; Mould Citation2018). Conversely, mentality, as rich insights provided by scholars in psychology and anthropology suggest, is constructed not only by personal traits but also by cultural aspects (Berger and Luckmann Citation1990; Geertz Citation1973).

In this context, we take particular inspiration from studies of the ‘sojourner mentality’ often found in Chinese migrant workers, who use the expression ‘luo ye gui gen’ (a fallen leaf always returns to the root) to describe their strong belief that their ‘roots’ remain in their hometown, to where they will return eventually (Gong Citation2016). The sojourner mentality is a good example of how environmental factors impinge on the construction of one’s sense of reality and, consequently, behavior. It may, for example, inhibit their local integration (Sun, Ling, and Huang Citation2020) or, in other cases, stimulate them to seek out diasporic communities as ‘homes away from home’ (Eng and Davidson Citation2008).

The sojourner, therefore, faces a sense of rootlessness and a pre-disposition to avoid unfamiliarity when away. On the other hand, a creative mentality supposedly shows higher potency in being independent, non-conformist, open to new experiences, and risk-taking boldness (Simonton Citation2000), making it more likely to flourish in alien, uncertain, and unfamiliar environments. As Gatti (Citation2009) suggests, a creative mentality is ‘cosmopolitan’, ‘open to diversity and multicultural’, ‘sociable and friendly’, and ‘career-driven or at least job-oriented’,

Regarding creative expats, in particular, we argue that they are dealing with the paradoxical intermingling of a creative and sojourner mentalities. They pursue exposure to diversifying and challenging experiences that help to weaken the constraints imposed by conventional socialization while strengthening their capacity to persevere in the face of obstacles (Simonton Citation1994). At the same time, however, as ‘strangers’ (Simmel Citation1950) – due to cultural, language, regulatory, and socio-economic barriers – they may feel constrained or reluctant to immerse fully in the host country’s habituated life.

Each of these conceptions of mentality, when taken alone, however, lacks due consideration of the paradoxes of being a creative worker in a foreign land. Furthermore, and related to this, there is also an absence of serious inquiry into the role played by the built environment of the host country in shaping – and being shaped by – this paradoxical mentality, beyond considering personality and culture. Indeed, the very idea of mentality – as is the case for ‘expats’ (Farrer Citation2019) – is ‘fuzzy’ and problematic. But, as we will show later in the empirical section, this term is grounded in the participants’ materiality and imaginaries of being a foreigner in China – thus imbued with social meaning and deserving of further exploration.

It is here that we find Deleuze and Guattari's (Citation1980) metaphor of striated and smooth spaces inspirational. For them, the striated space is a sedentary space that is coded, bounded, and limited. It has easily identifiable directions and clearly marked boundaries, and represents the effort to shape and contain all that passes, flows, and varies. It resembles the common imagination of the built environment but also the social norms and expectations of a certain group of people. Conversely, the smooth space features openness, rulelessness, and multiplicities. It consists of continuous variations of free actions that are short-lived, leaving no visual model for points of reference or measurement. The smooth space characterizes our mental space, where ideologies are formed, dreams are composed, and psychoanalytic topologies are performed (Lefebvre Citation1991, 3). Importantly, the smooth and striated spaces are not separated but interdependent and penetrative. The striated space is constantly translating and traversing the smooth space, while at the same time being reversed and ‘backanalyzed’ to a smooth space.

The relative dominance of striated and smooth spaces in the specific environs of individual lives, as well as the speed of transversions between the two, are arguably some of the key features defining our identity and how we relate to our environment. For those creative expats who manifest a paradoxical mentality, oscillating between a creative and a sojourner, Deleuze and Guattari’s framework is especially illuminating. Building on this and drawing on examples from Farrer (Citation2019), Meier (Citation2014b), Leonard (Citation2020) and Yeoh and Huang (Citation2013), we suggest therefore that creative expats may possess a transient mentality. Diverging from the earlier view of elite transnational workers as hyper-mobile, perpetually in transit, and repeatedly unmoored (Dharwadker Citation2001), we define this transient mentality as a paradoxical feeling that, despite being surrounded by striated spaces, there are no predictable social processes, and lives are crossed by a sense of transitoriness. It is the preponderance of smooth spaces associated with the vagaries, or the irregularity, uncertainty and ephemeral trait, of reckoning with and being a creative expat, which, in turn, is inscribed by, and at times reshaping, their relationships with the striated job markets, social networks, and eventually, the built environment. As we further explore in the empirical section, this transient mentality encompasses the transitory nature of the creative occupations and the perceived transiency of their social networks and the built environment.

The nature of creative occupations and job markets set creative expats apart from migrants engaged in ‘mass culture and work patterns typifying Fordism’ (de Peuter Citation2011, 418). Of course, there is a global trend towards dismantling the legal and institutional commitment to job security, wage standards, and work-time regulations, and migrants have long experienced a sense of precarity, prejudice, and exploitation due to their temporary, uncertain status and associated restrictions in mobility and benefits (Chacko and Price Citation2021), especially so in China with its striated social, economic, cultural, and political structures and processes that regulate and constrain immigrants’ lives. Yet the very nature of precariousness and casualization in the creative industries (Huws Citation2007; Hesmondhalgh and Baker Citation2011; Comunian and England Citation2020) is fundamentally different from those in traditional, labor-intensive sectors.

For the former, its precariousness stems from the unscheduled process of creative production, the undefinable and unpredictable nature of many creative jobs and markets, and the associated incomplete legal coverage and protection of creative occupations. For the latter, uncertainty is primarily a symptom of the high substitutional nature of both their jobs and their labor (Ross Citation2009). Moreover, the maturity and standardization of many jobs in labor-intensive sectors mean that migrant workers could deploy their skills and experiences in a new working environment relatively easily. For creative expats, however, the job uncertainties associated with the sector, the market, the customers, and the institutional settings in a foreign environment are much more severe. This necessitates a transient mentality featuring fluency, sensitivity, and adaptability – or a smooth space working on the striated space around it –, which also helps creative expats to develop their ‘enterprising self’ as a responding strategy to such fluid – and yet, striated from the point of view of the ‘stranger’ – working conditions (Storey, Salaman, and Platman Citation2005).

To counter the precariousness of creative labor, these workers rely strongly on their social capital, especially reputation and networks (Blair Citation2001; Lee Citation2011). Yet it is the parameter of social networks that differentiates creative expats from their domestic creative peers. Except for a few global ‘big names’, the majority of creative workers build and sustain their stratified networks locally with peers such as promoters, agents, club owners, and resource providers. These professional networks inevitably blend in with their social lives in a process of commodified social relations and immaterial labor (Lazzarato Citation1996). These networks ‘are carefully built up over years of local involvement’, and simply ‘being present on the scene’ is ‘vitally important’ (Hoedemaekers Citation2018, 1361). This local network embeds creative workers within a community of peers who assess each other, fomenting reputation and offering a common pool of labor where intangible knowledge is shared. The absence of such local networks or the prevalence of weak ties for creative expats, particularly in the early stages of their sojourning life, could further heighten their transient mentality.

Finally, the interactions between creative expats and the built environment also distinguish them from both their domestic peers and non-creative migrants. For domestic creative workers, living in a familiar and slow-changing built environment may have sheltered them from engaging with the physical environment consciously, curiously, and critically (Charalambous and Hadjichristos Citation2011; Black, Fox Miller, and Leslie Citation2019). For non-creative migrants, built environments are primarily viewed in their functional terms as places for living, working, commuting, and networking. They tend to cluster in specific neighborhoods with familiar architectural morphologies to their hometowns and rub shoulders with people from similar ethical, language, and cultural backgrounds, thus creating ‘expatriate ambiances’ (Beaverstock Citation2012; Dávila Citation2012). These communities conscientiously engage in the rebuilding of their built environments so that some of the social practices and cultural icons could be retrieved and reproduced, and that migrants could ‘remember’ and reconstruct the customary meanings in a foreign land (Eng and Davidson Citation2008).

Comparatively, creative expats are proactively sensing and engaging in a different and transforming built environment in a foreign country, reproducing zones of contact (Farrer Citation2019) which are then projected back to their transient mentality (Maslova and Chiodelli Citation2018). Such mentality also implies that, instead of seeking familiarity in morphology – although it happened for some creative expats in Buenos Aires (Dávila Citation2012) –, creative expats make residential and educational choices based on the images of a particular neighbourhood, their own experiences of the locations, and the ease of integration into the social networks of other creative expats (Meier Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Mulholland and Ryan Citation2014). Opposite to what underpins the idea of a creative mentality, therefore, we see transient mentality as contingent on larger social processes, smoothing and contracting striated spaces.

Through collective image-making and identity-building, jostling between smooth and striated spaces, creative expats’ transient mentality and preferences may feed back to the city, as the built environment and social networks respond to these inputs (Farrer Citation2019): private entities start investing in particular spatial products to satisfy creative expats’ consumption needs, opening cafes, boutiques, retrofitting houses, etc. For instance, the growing popularity of pop-up galleries, restaurants, and cultural amenities tries to attend to this transience. Furthermore, local governments also answer to their preferences, planning mixed-used neighborhoods or constraining creative activities in certain places. Such reciprocal relations could, as we perceived in Beijing, stimulate the fragmentation of the intra-urban habitat of global cities by creating patches of transnational places. Along with other studies on creative cities, we thus argue that the transient mentality of creative expats contributes to the production of a creative urban space that is localized and territorialized, and yet remarkably transient.

Methodology

Since we are primarily concerned with ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, and the phenomenon we are exploring is deeply embedded in its social-institutional context, a case study is regarded as the most suitable approach (Yin Citation2018). Specifically, we have chosen Beijing, the capital of China, to conduct this pilot study.

Beijing is a global city of more than twenty million residents, comprising approximately 12.7 million employees as of 2019 (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics Citation2020). According to official data, among these employed persons, there were 618,000 workers within the Cultural IndustriesFootnote1 sector, accounting for 5% of the municipal workforce. They contributed to over 9.3% of the city’s GDP in 2018 (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics Citation2020). Considering Florida’s (Citation2002) broader categorization of the creative class, the value of Beijing’s cultural and creative sector is even higher. For instance, the ‘Creative Development Index’, devised by Song et al. (Citation2021), shows considerable improvements in all indicatorsFootnote2 since 2012, driven by the city’s dedication to boosting its ‘cultural and creative influence’. In comparison to Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, Song et al. (Citation2021) find that Beijing is the most creative city in China.

In jostling for a spot on the global city map, Beijing’s urban development, similar to other post-industrial cities at home and abroad, is characterized by the fabrication of authenticity, where the creation of a ‘saleable aesthetic’ takes primacy in urban planning (Zhang Citation2018). Beijing is also regarded as a creative city due to its intensive transitional nature (Hall Citation2000). The city has witnessed the sprawl of the urban landscape in the past decade with the engulfing of rural and village areas and the demolition of old neighborhoods (hutongs), which were supplanted by mid- and high-rise residential units and urban amenities aimed at the upper classes. Urban expansion and renewal in Beijing replicated the main aspects of Chinese urbanization, namely ‘speed, scale, spectacle, sprawl, and segregation’ (Campanella Citation2008, 281).

Strong governmental oversight and market-driven strategies led to the ‘districtification’ of creative scenes in the city (Ren and Sun Citation2012; Liang and Wang Citation2020). Since 2006, when Beijing’s municipal government first referred to Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) by releasing the Outline of the National Cultural Development Plan During the 11th Five-Year Plan Period, a considerable number of regulations and initiatives have been carried out to promote cultural development in the city – much of which was encapsulated in the Beijing Municipal Master Plan 2016–2035 (Li Citation2021) and the various Beijing Cultural and Creative Industries White Papers (Beijing Citation2020). Moreover, in 2012, Beijing was designated by UNESCO as the Capital of Design and became a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (Beijing City of Design Coordination and Promotion Commission Office Citation2017).

However, as Liang and Wang (Citation2020, 63) contend, ‘[a]lthough Beijing has issued talent policies to attract and retain the highly skilled and highly educated, ironically artists are seldom beneficiaries of these special policies or special funds targeting the “creative class,”’ a trend that reinforces other authors’ assumption that this type of urban regeneration prioritizes ‘exchange value’ of creativity and property speculation over the ‘use value’ of CCI (Zhang Citation2018). This model of urban renewal, referred to as ‘artistic urbanization’ (Ren and Sun Citation2012), can be observed in areas that are highly attractive to creative expats, such as Nanluoguxiang and the 798 Art District.

In addressing our research questions, this article applied the interview-based method (Mears Citation2009), supported by qualitative survey and field observations, and drew on grounded theory for analysis (Auerbach and Silverstein Citation2003). As comprehensive official data on CCI employment are not available, let alone specific data regarding creative expats, this article does not offer a comprehensive picture of this population, but rather a thick description of participants’ experiences and feelings. The selection of participants was guided by Florida’s categorization of the super-creative core: computer and math occupations; architecture and engineering; life, physical, and social science; education, training, and library positions; arts and design work; and entertainment, sports, and media occupations. Interviews were anonymized and the sample is balanced in terms of occupation and the length of living in Beijing, but European and US nationals accounted for the bulk of interviewees in our sample, as was the case in other localities (Dávila Citation2012; Farrer Citation2019). By utilizing purposive and snowball sampling methods, we conducted 14 semi-structured, in-depth interviews between June 2021 and August 2022 (see below). Interviews were delivered online and lasted no less than 50 minutes. After collecting and analyzing the data, we applied the ‘narrator check’ technique (Mears Citation2009) to enhance transparency, communicability, and coherence (Auerbach and Silverstein Citation2003).

Table 1. List of participants.

To corroborate the interviews, we also conducted field observations in Beijing and qualitative surveys with creative expats. Field observations took place between 2017 and 2020 and focused mainly on documenting changes in the built environment, setting up informal conversations with foreigners, and finding patterns of foreigners’ locations along city districts. The observations were conducted by one of the authors, who self-identified as a creative expat in Beijing, providing valuable autoethnographic data alongside the other methods employed.

Lastly, the survey ran from July to August 2022 and consisted of multiple choice and open questions, which were designed according to the findings from interviews and field observations. The survey had an average response time of approximately 20 minutes, submitted by 20 creative expats from 12 nationalities, of which 10 identified as Female, 8 as Male, and 2 as non-binary. For the survey questionnaires, data entry was anonymous. In addition, we consulted secondary sources, such as policy documents, academic studies, and other media or non-academic publications. By applying these multiple methods of data collection, we sought to produce a collage (Freeman Citation2020) that synthesises diverse, and often fragmented, information about the expat life in China.

Creative expats in Beijing and their transient mentality

As a capital city of more than twenty million residents, Beijing is widely regarded by many creative expats as ‘a great place to take the pulse of China’. But this comes at a cost: air pollution, traffic congestion, and an urban environment that ‘feels incredibly tense’, in Rebecca’s words. Creative expats live and work amid a ‘paradoxical openness’, according to Ronald, where they perceive opportunities for realizing their aspirations, yet these opportunities are framed within the city’s growing environmental transformation, urban sprawl, and stricter regulations. As one of the participants acknowledges, living in Beijing, ‘you never really know what’s going on, there’s so much guesswork’. In this context, our data allow us to extract insights into the influences of occupational, social, and physical factors on the development of a transient mentality.

Flexible work hours, relatively high incomes, and the uncalculated nature of their creative production give most creative expats an occupational choice that nurtures their transient mentality and their urban lifestyles amid constant social and physical transformations in Beijing. Felicity, in her very artsy way of expressing things, explained that ‘creative communities are like water, they’ll spill and flow into other areas and find space’.

Consistent with other studies (Black, Fox Miller, and Leslie Citation2019), creative expats in Beijing engage in various projects that may not necessarily align with their formal occupation or legal status in China. Most survey respondents, for instance, agreed that ‘I have flexible work hours and productivity’ (65%) and ‘My occupation is dynamic and I’m always starting new projects’ (60%).

Alice laments that due to her ‘hectic schedule’, she didn’t have time for leisure: in fact, work and leisure were blended and re-signified. According to another participant, his formal occupation grants him ‘a visa and a salary’, but what he does ‘actually is quite varied because of [his] background’. Certain creative expats, such as schoolteachers or university professors, have joined music bands, whereas others are spouses that also found themselves immersed in the artistic community. To Gregory, he ‘never had anything like a real job, where you actually do something you hate, eight hours a day’. He got an offer as a university professor early on but has been playing jazz for decades in various venues in Beijing. Other creative expats found different sources of inspiration throughout their time in the city, which corroborated their investment in a myriad of projects and experiences.

The transient mentality of creative expats is also constituted by a social dimension defined by the inconstancy of their personal and work relationships. Marcus, for instance, admits that ‘the life cycle of an expatriate in Beijing generally lasts for about five years; every five years the city is kind of rolled over’. Many creative expats view Beijing as ‘a stop on the train’, where their social bonds during their time in the city are impacted by a sense of transitoriness. In the survey, only 25% of the creative expats indicated that their personal relationships ‘rarely change’, and those who have lived in Beijing for less than 5 years have confessed a prevalent sense of ‘awkwardness’ in their interactions with locals. Participants and survey respondents also mentioned additional factors, such as language barriers, different worldviews, and limited opportunities.

However, there is probably an unspoken, mutual acknowledgment that superficial relationships may shield both expats and Chinese individuals from greater suffering later when one party eventually departs Beijing. Several creative expats demonstrated a genuine yearning for broadening their social circles to include Chinese friends or workmates. However, depending on their age, occupation, and plans for the future, their efforts tended to be jeopardized and were ultimately put on hold. Matt illustrates this by admitting that he did a ‘rare thing among foreigners’ when he decided to move in with Chinese roommates upon his arrival in Beijing. But even after two years of living together and boasting an ‘excellent relationship’ with them, they would never hang out together – they had remarkably different lifestyles.

For other creative expats who have lived in Beijing for over a decade, their social network is mixed and diverse, which facilitated a certain amount of ‘crossover’ to mitigate isolation. As Marcus contends, ‘the nature of our work means that there has to be a lot of cooperation’ with the Chinese, and ‘cooperation leads to hanging out’. Becoming a member of bands and opening studios in art villages have contributed to these creative expats’ immersion in Beijing’s local life. Echoing this view, 60% of our survey respondents confirmed that most of the people they collaborate with are Chinese. As these creative expats extended their stay in Beijing, they increasingly became ‘outsider-within’ subjects (Collins Citation1986). Never totally part of the native community, but they have shortened the distance between them and Chinese social groups, hence less a ‘stranger’ in Simmel’s terms (Simmel Citation1950). They have married Chinese nationals; improved their language skills; and expanded their work relationships beyond the confines of the ‘expat bubble’, as reported by 15% of our survey respondents. They were ‘less of an expat to some people, but still sort of an expat’, as Gregory reflected.

So even for some of these long-time expats, their transient mentality still endures. They have witnessed several waves of expats and Chinese moving in and out of the city, entailing countless farewells and new bonds emerging. To Andrew, this presents a ‘paradox:’ both Chinese and expats know and live the ‘inevitability’ that eventually ‘you have to leave…, or else you’ll always be a foreigner’. Reflecting on this, he concludes that ‘it’s extremely rare for a foreigner to integrate himself to the point where he feels like he belongs’.

What has resulted from this, in Ronald’s words, is a ‘hard boundary between what is Chinese and what is foreign’, which ‘tends to impoverish the [cultural] scene a lot more’. The survey confirmed this, with 90% of responses indicating a hard boundary between what is foreign and what is Chinese. To another participant, ‘there’s still some collaboration with foreigners, but the content has gone, the content has become very bland, safe’. For him, only a few will dare to produce critical art in collaboration with foreigners. At the same time, some foreigners ‘are a bit snobby and enjoy feeling they’re not in China’, so they tend to only interact with other expats in foreigner-designed venues. How this affects their creativity, nevertheless, is ambivalent: whereas some lamented that ‘it will be difficult to feel creative if many of my close friends here are leaving’, some others would agree that ‘more people and more brains and more perspectives improve creativity’.

The third entangled factor contributing to the transient mentality of creative expats is a physical one, which stems from China’s rapid urbanization, particularly in Beijing. Veteran creative expats sound nostalgic when they reflect upon the transformations Beijing has gone through over the last two decades. Some of them reminisce about the ‘good old days’ when the city used to be more open, ‘authentic’, with ‘great accessibility’ and ‘very easy to navigate’. At that time, the Hutongs composed most of the inner cityscape and rural villages sat at the fringes of the capital. High-rises on the outskirts of the city were regarded as an exception. As participants recall conversations with peers, Beijing was ‘like New York in the 70s’. Creative workers would get ‘huge lofts’ and ‘large, industrial spaces for very, very convenient prices’. As another participant remembers, ‘as long as you steer[ed] clear of politics… the government mostly ignored [artistic manifestations]’. Beijing, and the Hutongs more specifically, was a ‘thriving cultural center’ with ‘grassroots’ initiatives, a ‘sporadic development’ that wasn’t ‘necessarily condoned or understood by the government’. Rob concludes: ‘it was so friendly, so warm, so simple’.

However, urbanization and rapid economic growth have transformed the metropolitan landscape. Urban renewal involved ‘brightening things up and modernizing everything’. As one participant puts it, in the good old days, ‘an enormous amount of culture, businesses, restaurants, small shops, the mom-and-pop stores, the sort of stands where they sell Jianbing popsicles’ were part of their everyday life in the city. Conversely, in present-day Beijing ‘nothing is [of] human scale’. To Ronald, ‘The roads are gigantic, the walls are gigantic, so it doesn’t feel intimate’. As a result, ‘everything is spread out to the point where it just feels monotonous and endless’ and ‘lost the feeling of the local people, the local cuisines, and also of the divers[ity]’. Art villages, where many creative expats had established studios, were ‘rebuilt, taken down, and repurposed again’.

To adapt to Beijing’s new market-driven planning, there has been an ‘increasing reliance on malls as sites of both cultural events and retail in general’, ‘so a lot of stuff that used to exist on the streets or in hutongs or mixed-use neighborhoods have largely been moved into malls’. Constant shutting down and opening up of venues ‘at an insane pace [compared to Europe]’ imprints a sense of uncertainty and transition that nothing is permanent there. This survey corroborates this trend: 85% of respondents agree that Beijing is ‘always changing’ (50%) or ‘changing very often’ (35%) – although some of our survey responses did find such dynamics attractive. One respondent commented that:

It’s very exciting to be in such a dynamic global city, you feel more connected to the world, alive. At the same time, as new things pop up in the city, new social groups emerge or merge in these spots, giving a sense of a very small village that is always changing. But this is often a bit lonely too.

For creative expats, these transformations affect their relation to the city. Gulou, for instance, until very recently could have been depicted as a prime example of Florida’s (Citation2002) bohemian neighborhoods, which symbolized the effervescence of the creative class. Exotic, picturesque architecture, narrow laneways with cafes, pubs, and social density, walkable and safe, Gulou ‘was the real attraction’ in Beijing, a ‘small-scale shopping street’ (Kasinitz, Zukin, and Chen Citation2016) where expats could create a sense of place - it is such the case that all interview participants, except one, either lived in or within walking distance from the hutongs. However, according to many expats, its cultural vibrancy has faded due to the ‘Hutong rectification campaigns’ – the crackdown on sanitary and community-related matters – from 2017 onwards. Now, for them, ‘people were told to kill this sense of community’ for the sake of modernity.

Transient mentality, urban life and expat clusters

How does this transient mentality affect the preferences for housing and the use of urban amenities among creative expats? As creative expats understand their reality to be very transient, we could observe that their housing choices and location patterns reflected a complex, often dialectic, interplay between their transient experiences in creative activities, social relations, and uses of the built environment. We could identify the formation of expat clusters in a few places in Beijing, either due to their housing preferences, workplaces, or social needs. Our data reveal while creative expats have disparate housing experiences in Beijing, they are united by a similar sense of transience – this is where the materiality of their transience, or the intermingling of striated and smooth spaces (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1980), took place.

The most important locational factors for housing were proximity to work and leisure, which are typically located near expat clusters, and affordable rent. But as prices have substantially increased over the past years, many felt compelled to rent apartments in cheaper neighborhoods and further away from their workplaces. According to Ronald, housing in Beijing is ‘deeply unaffordable’ and ‘often [of] very poor quality for the price you pay’. In some areas ‘you pay a premium just to live there’, but the quality of the buildings does not reflect the price. To him, there is also a ‘foreigner tax’ since ‘it’s just accepted that foreigners will pay more’. And this also rebounds against their creative production, as one survey participant lamented:

creative characters have left the city to go live somewhere more affordable, or they have had to join the workforce to be able to afford to live here. Life is much more expensive too, so there is not as much room for much creativity when earning has become the number one priority.

Based on their testimonies, creative expats (except for those who have married Chinese spouses) found housing in Beijing a burden, in which ‘there are so many substandard products’, as Felicity reckons. This is evident in their constant moves between different apartments, as survey responses attested: 80% had moved at least twice, and 50% had moved more than 3 times. Alice, perhaps the most extreme case, changed apartments three times in less than one year. Therefore, their experience with housing differs from Chinese residents in general, and domestic creative migrants specifically, who view real estate as an investment opportunity that may provide various perks related to education for their children and formal status as city residents. Marcus reflects on this difference:

At some point, I expect to leave China and so I’m not planning to put down roots here… so buying doesn’t make a lot of sense, not the least of which is that, you know, property here is expensive, not very well constructed, and frankly, not the best investment.

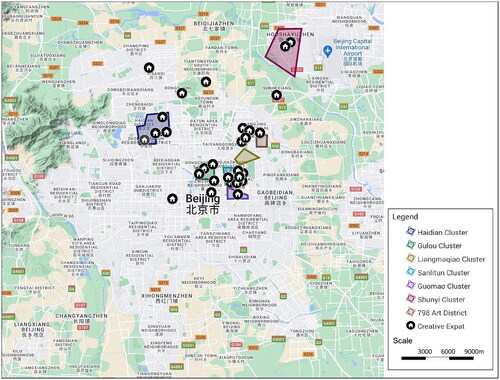

These international CWs shaped the built environment and influenced urban life (Farrer Citation2019) through the formation of informal expat clusters in a few places in Beijing where they could work, socialize, or live more comfortably – they were lured to specific neighborhoods that stand out, in their point of view, for their socio-economic density, networks, and flows of ideas (Wood and Dovey Citation2015, 53). In this sense, they affixed ‘their own territorialisation mode to the existing social construction of urban space’ (Gatti Citation2009, 3). We could identify, from interview and survey responses, at least six major expat clusters (see map below in ): Haidian, which comprises most of the education-related expats; Guomao, where ‘a lot of expats work for consultancies, law firms, accounting firms, it’s much more business-y over there’; Sanlitun, with the highest concentration of white westerners and ‘where foreigners go to parties’; the Gulou area, where there are ‘cool foreigners’ and cozy Hutongs; Shunyi, where ‘big international school’ teachers and ‘richer foreigners’ reside; and Liangmaqiao-Wangjing, where diplomats and other more stable professionals live with their families.

Expat clusters offer urban amenities that facilitate their connection with the local environment, where some want to ‘find the authentic city’ to live whereas others interact with people with whom they ‘have things in common’. There, creatives not only formed art collectives, set up companies, and met their friends; the built environment around them also responded to their preferences and needs. The Spittoon Arts Collective, for instance, transformed into ‘an artsy literary microcosm of Beijing’. Located in the hutongs, the collective was run by foreigners and frequented mainly by expats, although its ‘open-door policy’ did not forbid the Chinese to participate. Modernista, which has been shut down and opened up twice over the past two years, is another venue located in the hutongs where many creative expats would gather. Peach, a restaurant where a participant felt she ‘was in California or something’, epitomized these expatriate ambiances: ‘no one inside even tried to speak Chinese’.

These and several other places have renovated and redesigned themselves to adapt to foreigners’ tastes. As a consequence, many creatives cite a process that Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen (Citation2016) called the ‘global ABCs of gentrification:’ with the establishment of art galleries, boutiques, and cafés, rents have skyrocketed, and a very specific kind of consumer was welcomed. Nonetheless, to many creatives, clustering with their expat peers made sense: they confessed that after a week of working and ‘living’ in a Chinese environment, they meet their expat friends to get a ‘taste of home’. In this sense, creative expats, whose smooth space is in constant interaction with striated spaces, need to cope with the duality of being near and far; physically present, imprinting marks on the city with their consumption habits and lifestyles, but also socially distant. Their transient lives asked for spaces – both physical and symbolic – that smoothened their uprootedness.

Discussion and conclusion

Our paper strives to make two contributions to the proliferating literature on the creative cities and creative class. First of all, drawing insights from ethnographic research, especially migration studies, we unpack the black box of creative workers by focusing on the creative expats, who have become a substantial component of global and/or creative cities. Conceptually, and grounding on our findings, we distinguish creative expats from both non-creative migrations and their domestic creative peers by highlighting their transient mentality, which is related to the vagaries, or the irregularity, uncertainty and ephemerality, of reckoning with and being a creative expat. Moreover, the samples in our empirical study are primarily the ‘middling’ expatriates in between the elites and the low-waged, who represent a rather wide segment of the internationally mobile population that are in the middle of class positions at both their origin and destination contexts (Conradson and Latham Citation2005) and who have only recently gained attention in migration scholarship (Yang Citation2022).

Second, borrowing Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1980) metaphor of striated and smooth spaces, we respond to the call for more theorization and situated studies of the relationship between mentality and built environment, or between mobility and stasis (Lehmann Citation2014), by portraying the life experiences of creative expats, and in particular, how their transient mentality is framed by, and framing, the striated job markets, social networks, and the built environments in a foreign setting.

Our framework also addresses Farrer’s (Citation2019) criticism of the ‘methodological individualism’ in migration studies. In this sense, we argue that this transient mentality is used by creative expats as a coping strategy to manage a paradoxical, dialectical, and sometimes ambivalent process of sense-making, place-making, and subject-making. It helps to explain their precarious investment in career capital, social capital, and financial capital locally, their precarious lifestyles (Lin Citation2019b), as well as the inconclusive findings on their contributions to urban and regional economic growth as noticed in the existing literature. This study not only corroborates but also bridges important gaps in Lin’s (Citation2019b) account of creative expats in Beijing. We align with Lin’s findings – such as creative expats’ cosmopolitan subjectivity and ‘highly mobile work and life in Beijing’ (Lin Citation2019b, 462) –, while also emphasizing the significance of the built environment in shaping their transient mentality.

Flexible work arrangements and commodification of common and immaterial labor have long been rife in the creative sector. But for creative expats, such precariousness is intensified in a foreign context where the maturity of the creative industry, market conditions, and institutional arrangements are different and changing. In our case study of Beijing, creative practices often exist as ‘hobbies’ subordinate to ‘established job categories’ either because of immigration constraints or survival needs. Their liminal state, while providing flexibility in dealing with conventional social expectations of conformity and civility, also impedes the development of thick local networks and reputations. Here in Beijing, creative expats renegotiate the time and space through their transient mentality in balancing between integrating with the locals and bonding with other creatives who experience similar transience and foreignness. The speed and scale of urban transformations in Beijing, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, further strengthen their transient mentality, where places and practices of remembrance are regenerated, commercialized, and regulated at an insane speed, pushing the creative expats to hunt for the last Holy Land of authenticity or seek refuge in purposely built expatriate communities, stimulating the fragmentation of Beijing’s intra-urban habitat by creating patches of transnational places.

This transient mentality has several implications for urban planning and cultural policy, especially in global cities that work to brand themselves as international creative hubs. First, recent urban planning in Beijing didn’t seem to take into account creative expats’ preferences but rather pursued a more abstract sense of modernity that is represented by glass-windowed skyscrapers, clean-cut neighborhoods and gated communities, more controlled production of culture, car-friendly streets, etc. This modernization push is also witnessed elsewhere in the form of a ‘global toolkit of urban revitalization’ (Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen Citation2016). However, this urban revitalization often entails the dismantling of organic, local communities to make room for ‘pre-manufactured’ cultural spaces aligned with market demands. This creates a sense of uncertainty for creative expats and, possibly, other groups, i.e., a suspicion that they will eventually be forced out of their workspaces or places of living. They won’t invest in a permanent place to live or work and will migrate amongst expatriate ambiances and cities. Consequently, much of the cultural vibrancy that attracted developers in the first place may fade out with standard revitalization.

In agreement with Ren and Sun (Citation2012) and Liang and Wang (Citation2020) regarding the implications of the state-led creative policies in China, our exploration of the transient mentality of creative expats raises questions about their future in Beijing. Although some of our participants are long-term residents, our evidence suggests that, as a mobile class, creative expats will leverage their transient mentality to minimize the impact of standard urban renewal, seeking ‘uncharted’ places for a restart. Furthermore, environmental and regulatory constraints – as explored in other urban contexts in China (Farrer Citation2019) –, combined with the unfolding of a transient mentality, could act as a centrifugal force for these expats. Looking beyond indexes, we believe that the grounded experiences of creative expats cast doubt on Song et al. (Citation2021) assertion that Beijing is China’s most creative city. It also challenges Hall’s (Citation2000) idea of creative cities as highly transitional spaces: the evidence above shows that an accelerated transformation of the built environment, the institutional setting, and the urban demography may have the opposite effect.

Beijing, as an aspirational creative city, is thus pushing international creatives away. Cultural policies play an important role in this regard. For instance, Beijing’s cultural policy puts an overwhelming emphasis on economic outputs and upscaling the city’s international competitiveness with little reference to creative expats’ experiences (Beijing Citation2020). Urban planning and cultural policies converge in their market-driven dynamics, but creative expats’ story tells that these policies can be ineffective in the long term if they don’t understand what attracts and retains international talents. That is one of the reasons why creative expats witness a rapid turnover of establishments in Beijing amid an unsustainable urban regeneration approach that prioritizes ‘exchange value’ in creative production while dismissing hard conditions (Zhang Citation2018).

To accommodate and enrich creative expats’ experiences, not only short-term projects, such as art festivals, should be sponsored, but policies that convert their transient mentality into forms of belonging should also be encouraged. Furthermore, cultural policy and urban planning should converge in promoting the sporadic development of creative activities by avoiding intensive revitalization of creative clusters. Creative expats’ transient mentality is therefore a symptom of the increasing socioeconomic division that market-driven urban planning and cultural policies have instigated in Beijing (and global cities alike).

We hope the conceptual framework developed in this paper provides a starting point for conversation while bearing in mind its limitations. Constrained by the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews and surveys were conducted online, which could restrain the rich information conveyed in face-to-face meetings. Due to their relative immobility, participants devoted more time to reflecting on their lives prior to the pandemic. However, it is worth noting that the concept of transient mentality we develop may indeed be a significant explanatory factor for many expats’ decision to leave the country during the pandemic (several participants included). For those who chose to remain, their life experiences in cultivating a transient mentality were not adversely affected by COVID-19 – if anything, the pandemic only heightened such a feeling of transience.

Lastly, beyond COVID-19, creative expats’ lives are also enmeshed in overarching global trends and constrained by institutional/regulatory settings, as we discussed. The geopolitical tensions between China and Global North countries, for instance, add extra uncertainty to visa options and shorten expatriates’ length of stay in China. We argue that these trends are intimately correlated with creative expats’ transient mentality by making long-term prospects to be perceived as even more ephemeral. Therefore, we encourage more research on the macro-level dynamics that underpin such a transient mentality. Accordingly, we believe that more research should be carried out to explore and compare the mentalities of creative expats from different global cities in order to theorize what this entails for the particular urban contexts within which they are embedded.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 According to the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, Cultural Industries are officially divided into “Core Fields of Culture” and “Culture-related Fields.” For a detailed display of all subsectors, see Liang and Wang (Citation2020, 56).

2 Indicators include: Environment and support, Talent base, Benefit output, and Cultural and creative influence (Song et al. Citation2021, 182–183).

References

- Auerbach, C. F., and L. B. Silverstein. 2003. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Beaverstock, J. V. 2002. Transnational elites in global cities: British expatriates in Singapore’s financial district.” Geoforum 33 (4): 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00036-2

- Beaverstock, J. V. 2012. “Highly Skilled International Labour Migration and World Cities: Expatriates, Executives and Entrepreneurs.” In International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities, edited by B. Derudder, M. Hoyler, P. Taylor, & F. Witlox, 240–250. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Beijing 2020. Beijing Wenhua Chanye Fazhan Baipishu 2020. Beijing, China: Beijingshi guoyou wenhua zichan guanli zhongxin, zhongguo meiti daxue wenhua chanye guanli xueyuan.

- Beijing City of Design Coordination and Promotion Commission Office 2017. Beijing, China: Beijing City of Design – Monitoring Report 2017. UNESCO.

- Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics 2020. 2020 Beijing Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: China Statistical Press.

- Benson, Michaela, and Karen O’Reilly. 2009. “Migration and the Search for a Better Way of Life: A Critical Exploration of Lifestyle Migration.” The Sociological Review 57 (4): 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2009.01864.x

- Bereitschaft, B. 2017. “Do “creative” and “non-creative” workers exhibit similar preferences for urban amenities? An exploratory case study of Omaha, Nebraska.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 10 (2): 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2016.1223740

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1990. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

- Black, S., C. Fox Miller, and D. Leslie. 2019. “Gender, Precarity and Hybrid Forms Of Work Identity in the Virtual Domestic Arts and Crafts Industry in Canada and the US.” Gender, Place & Culture 26 (2): 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1552924

- Blair, H. 2001. “′You’re only as Good as Your Last Job’: The Labour Process and Labour Market in the British Film Industry.” Work, Employment and Society 15 (1): 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170122118814

- Bontje, M. 2016. “At Home in Shenzhen? Housing Opportunities and Housing Preferences of Creative Workers in a Wannabe Creative City.” Creativity Studies 9 (2): 160–176. https://doi.org/10.3846/23450479.2016.1203832

- Bontje, M., and S. Musterd. 2009. “Creative Industries, Creative Class and Competitiveness: Expert Opinions Critically Appraised.” Geoforum 40 (5): 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.07.001

- Bontje, M., S. Musterd, and B. Sleutjes. 2017. “Skills and Cities: Knowledge Workers in Northwest-European Cities.” International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 8 (2): 135. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKBD.2017.085152

- Boschma, R. A., and M. Fritsch. 2009. “Creative Class and Regional Growth: Empirical Evidence from Seven European Countries.” Economic Geography 85 (4): 391–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01048.x

- Campanella, T. J. 2008. The Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Castells, M. 2010. The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd ed., with a new pref. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Chacko, E., and M. Price. 2021. “(Un)settled sojourners in cities: The scalar and temporal dimensions of migrant precarity.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4597–4614. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1731060

- Charalambous, N., and C. Hadjichristos. 2011. “Overcoming Division in Nicosia’s Public Space.” Built Environment 37 (2): 170–182. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.37.2.170

- Collins, P. H. 1986. “Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought.” Social Problems 33 (6): S14–S32. https://doi.org/10.2307/800672

- Comunian, R., and L. England. 2020. “Creative and Cultural Work Without Filters: Covid-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy.” Cultural Trends 29 (2): 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577

- Conradson, D., and A. Latham. 2005. “Transnational Urbanism: Attending to Everyday Practices and Mobilities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2): 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000339891

- Dashefsky, A., and K. A. Woodrow-Lafield. 2020. Americans Abroad: A Comparative Study of Emigrants from the United States. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1795-1

- Dávila, A. M. 2012. Culture Works: Space, Value, and Mobility across the Neoliberal Americas. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- de Peuter, G. 2011. “Creative Economy and Labor Precarity: A Contested Convergence.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 35 (4): 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859911416362

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1980. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dharwadker, V. (Ed.). 2001. Cosmopolitan Geographies: New Locations in Literature and Culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Donegan, M., J. Drucker, H. Goldstein, N. Lowe, and E. Malizia. 2008. “Which Indicators Explain Metropolitan Economic Performance Best? Traditional or Creative Class.” Journal of the American Planning Association 74 (2): 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360801944948

- Eng, K.-P. K., & Davidson, A. P. (Eds.). 2008. At Home in the Chinese Diaspora. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230591622

- Farrer, J. 2010. “New Shanghailanders’ or ‘New Shanghainese’: Western Expatriates’ Narratives of Emplacement in Shanghai.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (8): 1211–1228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691831003687675

- Farrer, J. 2019. International Migrants in China’s Global City: The New Shanghailanders. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York, NY: Basic Books (AZ).

- Florida, R. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203997673

- Franklin, S. W. 2023. The Cult of Creativity: A Surprisingly Recent History. Chicago, MI: The University of Chicago Press.

- Freeman, C. 2020. “Multiple Methods Beyond Triangulation: Collage as a Methodological Framework in Geography.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 102 (4): 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2020.1807383

- Gardner, A. 2010. City of Strangers: Gulf Migration and the Indian Community in Bahrain. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

- Gatti, E. 2009. “Defining the Expat: The Case of High-Skilled Migrants in Brussels.” Brussels Studies 28. https://doi.org/10.4000/brussels.681

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Glaeser, E. L. 2012. Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Gong, T. 2016. “Bridge or Barrier: Migration, Media, and the Sojourner Mentality in Chinese Communities in Italy and Spain.” In Media and Communication in the Chinese Diaspora: Rethinking Transnationalism, edited by W. Sun. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hall, P. 2000. “Creative Cities and Economic Development.” Urban Studies 37 (4): 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980050003946

- Hannerz, U. 1996. Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and S. Baker. 2011. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hoedemaekers, C. 2018. “Creative Work and Affect: Social, Political and Fantasmatic Dynamics in the Labour of Musicians.” Human Relations 71 (10): 1348–1370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717741355

- Howard, R. W. 2009. “The Migration of Westerners to Thailand: An Unusual Flow From Developed to Developing World.” International Migration 47 (2): 193–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00517.x

- Hoyman, M., and C. Faricy. 2009. “It takes a Village: A Test of the Creative Class, Social Capital, and Human Capital Theories.” Urban Affairs Review 44 (3): 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087408321496

- Huws, U. 2007. “The Spark in the Engine: Creative Workers in a Global Economy.” Work Organisation, Labour and Globalisation 1 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.13169/workorgalaboglob.1.1.0001

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Kaplan, S., and Y. Fisher. 2021. “The Role of the Perceived Community Social Climate in Explaining Knowledge-Workers Staying Intentions.” Cities 111: 103105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103105

- Kasinitz, P., S. Zukin, and X. Chen. 2016. “Local Shops, Global Streets.” In Global Cities, Local Streets: Everyday Diversity from New York to Shanghai, edited by S. Zukin, 1st ed., 195–206. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kim, H. M., and M. Cocks. 2017. “The role of Quality of Place factors in expatriate international relocation decisions: A case study of Suzhou, a globally-focused Chinese city.” Geoforum 81: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.01.018

- Lawton, P., E. Murphy, and D. Redmond. 2013. “Residential Preferences of the ‘Creative Class’?” Cities 31: 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.04.002

- Lazzarato, M. 1996. “Immaterial Labor.” In Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, edited by P. Virno & M. Hardt, vol. 1996, 133–147. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lee, D. 2011. “Networks, Cultural Capital and Creative Labour in the British Independent Television Industry.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (4): 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711398693

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space, Translated by D. Nicholson-Smith. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Lehmann, A. 2014. Transnational Lives in China. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137319159

- Leonard, P. 2020. Expatriate Identities in Postcolonial Organizations: Working Whiteness. London, UK: Routledge.

- Li, J. 2021. “Advancing Cultural Progress to Build Beijing into a National Cultural Center.” In Analysis of the Development of Beijing, 2019, 243–290. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6679-0_8

- Liang, S., and Q. Wang. 2020. “Cultural and Creative Industries and Urban (Re)Development in China.” Journal of Planning Literature 35 (1): 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412219898290

- Lin, J. 2019a. “Be Creative for the State: Creative Workers in Chinese State-Owned Cultural Enterprises.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (1): 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877917750670

- Lin, J. 2019b. “(Un-)becoming Chinese Creatives: Transnational Mobility of Creative Labour in a ‘global’ Beijing.” Mobilities 14 (4): 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1571724

- Maslova, S., and F. Chiodelli. 2018. “Expatriates and the City: The Spatialities of the High-Skilled Migrants’ Transnational Living in Moscow.” Geoforum 97: 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.010

- Mears, C. L. 2009. Interviewing for Education and Social Science Research. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230623774

- Meier, L. 2014a. “Learning the City by Experiences and Images: German Finance Managers’ Encounters in London and in Singapore.” In Migrant Professionals in the City: Local Encounters, Identities and Inequalities, edited by L. Meier, First issued in paperback, 59–76. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Meier, L. 2014b. Migrant Professionals in the City: Local Encounters, Identities and Inequalities. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mellander, C., and R. Florida. 2021. “The Rise of Skills: Human Capital, the Creative Class, and Regional Development.” In Handbook of Regional Science, edited by M. M. Fischer & P. Nijkamp, 2nd ed., 707–719. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23430-9_18

- Miao, J. T. 2021. “Getting creative with housing? Case studies of Paintworks, Bristol and Baltic Triangle, Liverpool.” European Planning Studies 29 (6): 1050–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1777942

- Mould, O. 2018. Against Creativity. London, UK: Verso.

- Mulholland, J., and L. Ryan. 2014. “Londres Accueil’: Mediations of Identity and Place among the French Highly Skilled in London.” In Migrant Professionals in the City: Local Encounters, Identities and Inequalities, edited by L. Meier, First issued in paperback, 157–174. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Murphy, E., and D. Redmond. 2009. “The Role of ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ Factors for Accommodating Creative Knowledge: Insights from Dublin’s ‘Creative Class.” Irish Geography 42 (1): 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00750770902815620

- Nunan, D. 2018. Other Voices, Other Eyes: Expatriate Lives in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Blacksmith Books.

- Peck, J. 2005. “Struggling with the Creative Class.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (4): 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Pitts, F. H. 2020. “Expat Agencies: Expatriation and Exploitation in the Creative Industries in the UK and The Netherlands.” In Pathways into Creative Working Lives, edited by S. Taylor & S. Luckman, 159–174. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38246-9

- Ren, X., and M. Sun. 2012. “Artistic Urbanization: Creative Industries and Creative Control in Beijing: Creative industries in Beijing.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (3): 504–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01078.x

- Rocha, Z. L. 2015. Mixed Race” Identities in Asia and the Pacific: Experiences from Singapore and New Zealand. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Ross, A. 2009. Nice Work If You Can Get It: Life and Labor in Precarious Times. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Santos, M. 2017. Toward an Other Globalization: From the Single Thought to Universal Conscience. 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53892-1

- Sassen, S. 2001. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400847488

- Sennett, R. 2019. Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. London, UK: Penguin books.

- Simmel, G. 1950. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Simonton, D. K. 1994. Greatness: Who Makes History and Why. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Simonton, D. K. 2000. “Creativity: Cognitive, Personal, Developmental, and Social Aspects.” The American Psychologist 55 (1): 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.151

- Sleutjes, B., and W. R. Boterman. 2014. Stated Preferences of International Knowledge Workers in The Netherlands. HELP-International Report, 1–127. UvA.

- Song, M., W. Peng, and H. Zhongming, Beijing Academy of Social Sciences 2021. “A Study of Beijing Creative Development Index.” In Analysis of the Development of Beijing, 2019, 163–197. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6679-0_5

- Storey, J., G. Salaman, and K. Platman. 2005. “Living with enterprise in an enterprise economy: Freelance and contract workers in the media.” Human Relations 58 (8): 1033–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726705058502

- Sun, J., L. Ling, and Z. (Joy) Huang. 2020. “Tourism Migrant Workers: The Internal Integration from Urban to Rural Destinations.” Annals of Tourism Research 84: 102972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102972

- Wilczewski, M. 2019. Intercultural Experience in Narrative: Expatriate Stories from a Multicultural Workplace. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Wood, S., and K. Dovey. 2015. “Creative Multiplicities: Urban Morphologies of Creative Clustering.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (1): 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2014.972346

- Yang, P. 2022. “Differentiated Inclusion, Muted Diversification: Immigrant Teachers’ Settlement and Professional Experiences in Singapore as a Case of ‘Middling’ Migrants’ Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (7): 1711–1728. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1769469

- Yeoh, B., and S. Huang. 2013. The Cultural Politics of Talent Migration in East Asia. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles, LA: SAGE.

- Zenker, S. 2009. “Who’s Your Target? The Creative Class as a Target Group for Place Branding.” Journal of Place Management and Development 2 (1): 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538330910942771

- Zhang, A. Y. 2018. “Pop-up Urbanism: Selling Old Beijing to the Creative Class.” In Chinese Urbanism: New Critical Perspectives, edited by M. Jayne, 137–148. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Zukin, S., P. Kasinitz, and X. Chen. 2016. “Spaces of Everyday Diversity: The Patchwork Ecosystem of Local Shopping Streets.” In Global Cities, Local Streets: Everyday Diversity from New York to Shanghai, edited by S. Zukin, 1st ed., 1–28. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.