Abstract

The Öresund Bridge between Sweden and Denmark was opened in 2000, allowing both road traffic and fast commuter trains to travel between Malmö and Copenhagen. Various agreements have long facilitated passport-free travel. However, at the end of 2015, temporary border controls were first introduced. This paper aims to provide a deeper understanding of portrayals in the news media and everyday mobility experiences relating to border controls, with a special focus on Hyllie Station in the city of Malmö, in southern Sweden. The article is based on a compilation of the way Hyllie Station has been depicted in the news media for a deeper contextual understanding combined with a public participation GIS dataset focusing on the safety and security experiences of public transport nodes. Hyllie station, border controls and the presence of security personnel are depicted in different ways and at different levels. The complexities of life are intensified due to the daily cross-border commute and extra time required by border controls. The issue of mobility justice is raised, and the interrelationship between power and mobility becomes more and more tangible. Hyllie is a traffic node wherein the barriers of mobility and immobility become blurred, and power is displayed on different levels.

Introduction

The so-called ‘refugee crisis’ in the autumn of 2015 laid bare those very boundaries, emphatically splitting the Øresund region into two nations once again, while making very clear that certain groups of people were not welcome to participate in the Øresund imaginary (Chow Citation2021, 28).

Since at least early 2000, there has been a common vision in the Öresund region to promote cooperation and integration between Sweden and Denmark (Malmö Stad Citation2023). Nowadays, this area is often referred to as Greater Copenhagen and is described as a Danish-Swedish political cooperation for economic growth and development (e.g. Greater Copenhagen n.d.; Persson and Persson Citation2021). The Öresund region is described as ‘the largest labour market in the Nordic region’, with about 16,900 people commuting across the border from Sweden to Denmark, and about 1,400 commuting in the opposite direction, from Denmark to Sweden, in the year 2022 (Statistics Denmark Citation2023). The Öresund Bridge links Copenhagen (the capital of Denmark) with Malmö (Sweden’s third-largest city). Inaugurated in the year 2000, the Öresund Bridge is an approximately 16-kilometre-long combined railway and motorway bridge. For many years, it has been possible to move freely between the two cities.

However, in November 2015, temporary border controls were introduced in Sweden for those entering from Denmark, including via the Öresund bridge. This was a result of the large movements of refugees, mainly from Syria and Afghanistan (e.g. Chow Citation2021; Degerman Citation2021). This measure followed a decades-long absence of border controls, first by the Nordic Passport Union (see Nordic Co-operation n.d.), and then the Schengen Agreement (see EUR-Lex n.d.). Since then, continuous controls have been carried out, and, as in the case of the coronavirus pandemic, borders have been periodically partially closed, with border controls being intensified. Recent measures are reported to have served four main purposes since November 2015: managing the reception of asylum seekers, reducing the spread of infection in connection with the coronavirus pandemic, preventing terrorism and controlling cross-border crime (Øresundsinstituttet Citation2022).

Additionally, in September 2022, a new government was elected in Sweden. In contrast to the previous government, political parties with a more right-wing ideology were elected. The parties forming the government have made it a priority to significantly reduce immigration and combat irregular migration by increasing and intensifying border controls (Moderaterna, Sverigedemokraterna, and Kristdemokraterna Citation2022). On the 12th of November 2023, border controls were reintroduced due to a new security situation in Sweden with an assessed increase in the national terrorist threat level. These measures are planned to remain in place until the 11th of May 2024 (Regeringskansliet Citation2023). In recent years, the news media have reported on how border controls have affected people’s everyday mobility in different ways and posed various challenges in the daily lives of cross-border commuters.

News media representations and everyday mobility experiences related to border controls in the Öresund region can be viewed from the perspective of uneven mobility (for conceptual discussions see e.g. Cresswell Citation2010; Sheller Citation2016, Citation2018a, Citation2018b) and mobility justice (Sheller, 2018 a, b). Mobility is unevenly distributed (Cresswell Citation2010; Sheller Citation2016,Citation2018a, Citation2018b) and experienced differently depending on different preconditions and/or embodied differences, such as income, gender, age, race, disability, migrant status, number of children and more (see research review of Hidayati, Tan, and Yamu Citation2021). Mobility justice is seen as one of the most pressing political and ethical issues in contemporary society, given the ongoing challenges posed by, for example, climate change and the global refugee crisis (which encompasses complex issues of borders and humanitarianism) (Sheller Citation2018a, Citation2018b). According to Sheller (Citation2018a, p 17), these challenges ‘produce the sharpest contours of uneven mobility’.

Furthermore, unequal mobility regimes operate at different levels and scales (e.g. macro, meso, micro), and their interconnectedness can be demonstrated through a variety of examples. These include relationships between elite mobilities and refugee movements, and in turn relationships between climate change and urban resilience, military mobilities, racial segregation and more (see p. 18). According to Sheller (Citation2018a, 18), further research is needed:

Current approaches to transport justice, environmental justice, and even spatial justice have not spent enough time showing how embodied differences […] influence accessibility and interact with the mobility regimes and control systems that reproduce uneven mobilities.

However, there seems to have been a limited focus on issues related to cross-border commuting in the region and impacts on daily life from the perspective of uneven mobilities and mobility justice; yet, the issue is to some extent highlighted, for example, in a Swedish research report about cross-border commuters’ everyday experiences related to the changes that occurred in 2015-2016 following the introduction of border controls (Winter Citation2016), and in a Swedish book chapter about a so-called ‘double-exposed injustice’ (Winter Citation2023).

This paper aims to provide a deeper understanding of portrayals in the news media and everyday mobility experiences relating to border controls in the Öresund region, with a special focus on Hyllie Station in the city of Malmö. The article is based partly on a compilation of how Hyllie Station has been portrayed in the media in recent years to gain a deeper contextual understanding, and partly on a public participation GIS (PPGIS) dataset collected in 2021, using a mixed-method approach including both qualitative and quantitative elements about experiences related to Hyllie Station. The paper starts by discussing the concept of cross-border mobility and cross-border commuting, followed by everyday mobility, (in)security, the fabric of urban life, mobility justice and the interrelation of power. The study context will then be presented, followed by the method. The results are structured in two parts; first, findings from portrayals in the news media will be presented, with the ambition of providing a deeper contextual understanding; this is followed by the findings from the online PPGIS survey. The paper ends with a discussion.

Cross-border mobility and cross-border commuting

Cross-border mobility can include the movement of goods, commuters, posted workers and migrants. Furthermore, cross-border mobility is often seen as ‘one of the most important factors to solidify European integration’ (Parenti and Tealdi, 2020, 185), as well as being ‘a way to improve an efficient allocation of labour resources, improve the economic performance of border regions and reduce economic and territorial inequality’ (Edzes, van Dijk, and Broersma Citation2022, 1). However, borders can also be regarded as ‘complex textures’ (Brambilla Citation2023, 1), and perceived as ‘social, cultural and political constructions’ (Sohn Citation2023, 4). Consequently, cross-border mobility often faces a variety of obstacles, such as administrative boundaries (Medeiros Citation2019), as well as legal, social, and infrastructural barriers (Parenti and Tealdi Citation2021).

Cross-border mobility has been studied from different perspectives, such as to research European identity and attitudes toward the EU among adolescents and young adults (Mazzoni et al. Citation2018; Kuhn Citation2012; Sigalas Citation2010) to study cross-border mobility experiences among migrants in EU (Consoli, Burton-Jeangros, and Jackson Citation2022) or to study effects of ‘covidfencing’ in Europe due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Medeiros et al. Citation2021).

Cross-border commuting is here defined as working in one EU country and living in another, returning home daily or at least once per week (EU Citation2023). Cross-border commuting has been studied from different perspectives, including examining specificities of transboundary commuting together with transport challenges in Central Europe (Cavallaro and Dianin Citation2019), or studying labour mobility in the Danish‐German border region with a focus on increasing labour market integration (Buch, Dall Schmidt, and Niebuhr Citation2009). Few studies have focused on the Öresund Bridge, cross-border commuting, and border controls, especially concerning issues of uneven distribution of mobility and mobility justice.

At the same time, critical events have in recent years come to challenge cross-border commuting and the notion of a Free Movement Principle in the EU (the free movement of workers is described as one of the fundamental principles of the EU, see European Commission n.d.a) and the Schengen Agreement (with the ambition of ‘the border-free Schengen Area’, see European Commission n.d.b). Such events include the so-called ‘refugee crisis’, Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic, the security situation following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and more. Public and political debates have increasingly focused on security issues and how the EU can be protected against external threats and terrorism. Recent research describes mobility in the EU as being ‘under pressure in an increasingly closed Europe’ (Lund Thomsen Citation2020) and, among others, highlights the spatial perspective of border controls inside the Schengen area following the terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels (year 2015 and 2016) (Evrard, Nienaber, and Sommaribas Citation2020). Overall, these are issues that can also be linked to the Öresund Bridge and border controls.

However, some regard the fear created by terrorism to itself be something that threatens to ‘undermine democratic governments’ and that it can ‘empower political extremes, and polarize societies’ (Byman Citation2019;1). Beauchamps and colleagues discuss the ‘conceptualisations of threat’ to, among other things, discourses about organisational crime, migration, and terrorism (Beauchamps et al., Citation2017; Walters Citation2006), and further reflect on how mobility is ‘both a condition of global modernity’ as well as a ‘source of insecurity’ (p. 1).

Everyday mobility, (in)security and the fabric of urban life

Mobility must be considered an essential part of people’s everyday lives for managing day-to-day activities, participating in society, maintaining social relations and activities, and for social inclusion (e.g. Urry Citation2007; Cass, Shove, and Urry Citation2005). Mobility is manifold and contextual (Schwanen and Ziegler Citation2011), and is experienced differently depending on varying preconditions and embodied differences (e.g. Adey Citation2017; Sheller Citation2016, Citation2018a, Citationb; Hidayati, Tan, and Yamu Citation2021), where factors such as class, ethnicity and age can significantly affect the possibility of mobility (Cresswell Citation2010; Cresswell Citation2006). This also includes gender (e.g. Bohman et al. Citation2021), whether one moves as a tourist or refugee (e.g. Sheller 2018; Cresswell Citation2010), and individual capability or disability (e.g. van Holstein, Wiesel, and Legacy Citation2022).

In spatial terms, mobility is shaped by a variety of both tangible and intangible, individual, contextual, and environmental barriers. Mental maps, fear of crime and insecurity are examples of intangible barriers (Massey Citation2006). Hence, security is a complex concept intertwined with several issues, such as what/who is to be protected, and from what/whom it or they are to be kept safe (for a conceptual discussion, see Beauchamps et al., Citation2017, 3-4).

Feelings of insecurity can manifest themselves in different ways on a micro level and often result in things such as behavioural consequences (Keane Citation1998), precautionary behaviour (Ceccato, Langefors, and Näsman Citation2021; Kappes, Greve, and Hellmers Citation2013), avoidance and/or defensive behaviour (Rader, May, and Goodrum Citation2007). Additionally, Church, Frost, and Sullivan (Citation2000), argue that insecurity is a barrier to mobility. Feeling unsafe on, for instance, public transport can, among other things, lead to an individual’s mobility being restricted, and may mean that people choose not to use public transport or perhaps only travel at certain times of the day (Stjernborg Citation2024; Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris Citation2021; Church, Frost, and Sullivan Citation2000). Feelings of insecurity may also mean that other types of mobility strategies are used, such as taking detours and avoiding certain places, streets or areas (Condon, Lieber, and Maillochon Citation2007; Jackson and Gouseti Citation2012). News media can also influence the sense of security in different locations, not least through the creation of stereotypical images and by building on discourses of fear. Media can influence the stigmatization of locations, people’s mental maps and thus people’s everyday mobility (Stjernborg, Tesfahuney, and Wretstrand Citation2015).

Furthermore, more than a decade ago, Professor Stephen Graham described a paradigmatic shift in cities, where municipal and private places, infrastructure and population are increasingly seen as targets for various threats. He referred to this shift as ‘the new military urbanism’, something that can be reflected in the constant usage of the term ‘war’ as the prevailing metaphor to characterise situations in cities; ‘at war against drugs, crime, terror, and insecurity itself’. He further argued that this development incorporates the ‘militarization’ of everything from political debates to the urban landscape, leading ‘to the creeping and insidious diffusion of militarized debates about security in every walk of life’ (Graham Citation2010, xiv). Graham claimed that:

…New Military Urbanism permeates the entire fabric of urban life, from subway and transport networks hardwired with high-tech 'command and control’ systems to the insidious militarization of a popular culture corrupted by the all-pervasive discourse of 'terrorism’ (2010, back cover).

Mobility justice and the interrelation of power

Mobility justice is based on the concept of social justice, which aims to establish a fair and equal society in which individual rights are recognized and protected, and where decisions are made with equity and fairness in mind (see Oxford Reference 2023). Mobility justice describes the uneven distribution of mobility and immobility as well as the power that shapes, modifies, perpetuates, and controls those uneven movements (Sheller Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Furthermore, mobility justice can be detected on a micro (e.g. individual), meso (e.g. local transportation), or macro level (e.g. transnational mobility) (ibid.). Additionally, mobility justice, among others, ‘concerns the control of borders, migration, refugee policy, and citizenship’ (Sheller Citation2018a, 27). The concept has been examined concerning ‘infrastructures of injustice’ and migration and border mobilities (Kathiravelu Citation2021), concerning different contexts, such as mobility justice in rural areas (Barajas and Wang Citation2023; Flipo, Ortar, and Sallustio Citation2023), or for studying experiences of driver attitudes and behaviour among travellers with disabilities (Das Neves, Unsworth, and Browning Citation2023), and more.

Moreover, the interrelation of power and mobility can be displayed in different ways. Urry discussed this interrelation based on the possibility of movement, which is conditioned by ‘Network capital’ (Urry Citation2007). This includes relevant necessary documents such as visas, financial capital, physical capital, cultural capital, or social capital and the power that has been granted to each of those attributes. Thus, mobility can create or maintain power structures (e.g. Sheller Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Furthermore, organizational challenges such as infrastructural conditions, temporal limits or transport timetables can interfere with mobility. Hence, mobility and power structures can be reflected on different levels.

Study context

Sweden is a part of Scandinavia, and shares borders with Norway, Finland, and Denmark. It has a population of approximately 10.5 million people. Immigration to Sweden has increased since the turn of the century. In 2016, the total amount of immigration was the highest the country so far had ever seen, with more than 163,000 people immigrating to Sweden. The number fell in 2017 to just over 144,000 people and has remained lower since then (SCB (Statistics Sweden) Citation2022).

In November 2015, due to the large immigration flows, temporary border controls were introduced in Sweden for those entering from Denmark (including those travelling via the Öresund Bridge). Since then, border controls have been periodically reintroduced for various reasons. The most recent reintroduction was in November 2023, because it had been determined that there was an increased security risk – from level three to four on a five-point scale (Regeringskansliet Citation2023). The Swedish Security Service describes how Sweden’s image has changed, due in part to demonstrations where holy scriptures have been desecrated by individual operators and because of various disinformation campaigns (Swedish Security Service Citation2023). In addition to this, Sweden is struggling with an increase in gang criminality, which is identified as ‘Sweden’s most pressing societal problem’ by Sweden’s main governing party (Moderaterna Citation2023). In 2022, there were 391 shootings, with a total of 62 deaths. There were also 90 ‘successful’ bombing attacks in the country (Swedish Police Citation2023).

However, the temporary border controls have had an impact on travel in the region. The ID checks have meant longer travel times with fewer departures during rush hours, which has created challenges for many cross-border commuters. Train commuters have shown to be particularly affected, and the number of season tickets sold in, for example, 2016 decreased by 8.3% compared to 2015, while commuting by car across the bridge increased (Øresundsinstituttet n.d.).

Hyllie station

Hyllie is a district located on the southern outskirts of Malmö, the third largest city in Sweden with approximately 350,000 inhabitants. With its proximity to the Öresund Bridge that connects Sweden to Denmark, it is seen as a rather attractive location on a local and international scale. Hence, since 2012, Hyllie district has been growing rapidly. In 2021, 5,500 people lived in the Hyllie district, and by 2040, this number is expected to increase to 25,000 (Malmö Stad Citation2021, Citation2022).

Hyllie Station is located in the heart of the Hyllie district and is one of the largest traffic nodes in Sweden. The so-called City Tunnel that connects to Hyllie Station allows passengers to reach Malmö city centre within 3 minutes, Copenhagen Airport within 13 minutes, and Copenhagen city centre within 28 minutes. By 2016, Hyllie Station had become Malmö’s third busiest station with approximately 20,000 boarding/disembarking travellers daily (Region Skåne, Citation2016).

Hyllie station opened in 2010 (Malmö Stad Citation2022), with what is described as a ‘high level of security’ thanks to patrolling security guards and round-the-clock camera surveillance (Skånetrafiken Citation2011). Hyllie Station is also the final station in Sweden before entering the Öresund Bridge and Denmark, and it is there that border controls have been carried out from time to time for travellers arriving from Denmark.

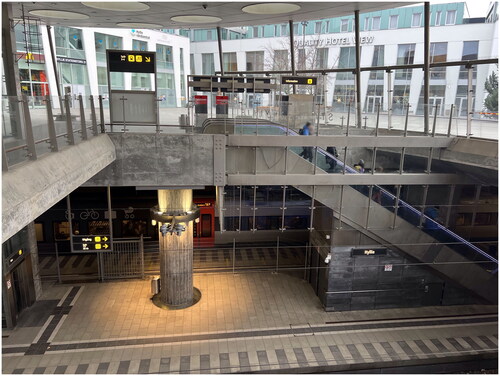

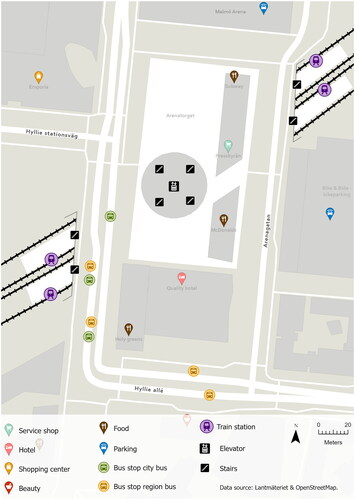

Hyllie Station is located next to a large shopping mall, a hotel, a large arena, and several restaurants. The main square offers seating areas and provides space for people to gather, and more (see ).

Figure 1. Map of hyllie station map: Felicia Gauffin Jatta.

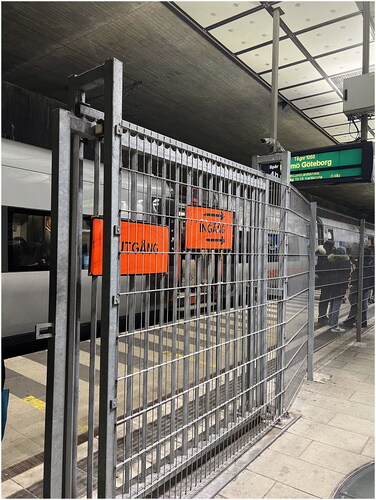

Hyllie Station is divided across two levels from which international and regional trains can depart, as well as regional and local buses. Access to the trains is on the lower level via stairs, escalators, or elevators. Trains arriving from Denmark stop on a track that is separated from other tracks by a fence. A customs and police office are located on the platform. When passport controls are in place, passengers who want to enter a train must wait behind the closed fence until border controls have been carried out and the fence is opened so that passengers can enter the platform (see ). Bus stops can be found on the upper level close to the entrance.

Material & method

The study is based on an overall description of how Hyllie station (and border controls) have been portrayed in the news media in recent years for a deeper contextual understanding. In 2021, a web-based survey was also undertaken for a greater understanding of traveller experiences of public transport nodes in Malmö, spread through social media, to highlight issues of safety and security concerning public transport nodes in the city. This study is based on the parts of the survey that concern Hyllie station, for a more comprehensive review of the study (see Stjernborg Citation2024).

Newspaper articles

To gain a deeper contextual understanding of how Hyllie station, with border controls, was portrayed in the media, searches were made in the Media ArchiveFootnote1 via the search string border control AND Hyllie station, the searches were carried out in the spring of 2024. The search resulted in a total of 1968 hits between the years 2015 and 2023, with 723 hits (after the system grouped articles that were the same but published in different newspapers, as it is common for the same article to be published in several newspapers). Some articles were excluded from the analysis because they were deemed irrelevant and had limited relevance to border controls, Hyllie station and the Öresund region. Other articles were excluded because they, for example, addressed border controls in Sweden in general, or from a more general perspective at the EU level. Similarly, audio media (such as radio clips and the like) were also excluded.

The articles were published in local, regional, and national daily newspapers. The search results were reviewed, in some cases, only the headline was read, and in most cases, entire articles were read. Several reviews of the articles were conducted to identify themes and to gain a deeper understanding of the content. The study is mainly based on qualitative textual analyses (see Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004), and the articles were categorized into different themes (see ). After the screening of articles, 1287 articles remained (many of which were the same article but published in different newspapers).

The purpose is to present a more general picture of how border controls have been depicted in the media, incidents that received special attention over the years, and to give examples of the language used in many of the articles. The analysis is presented here at a broader level, including descriptions of border controls in general, perceptions of threat, the issue of free movement, the impact on the daily lives of cross-border commuters and criticisms of border controls.

Public participation GIS

The study is also partly based on empirical material that was collected in the spring of 2021 through a web-based survey developed with the help of Maptionnaire. Maptionnaire is a participatory tool developed by researchers. With the tool, it is possible to design web-based surveys where questions are combined with maps and images (SoftGIS). This web survey included four components. The analyses in this article are mostly focused on the components of the survey that affect Hyllie station.

The initial part of the online survey focused on respondents’ travel habits, including amongst other questions on how frequently they leave home, or how frequently they travel by public transport. The questions were asked with regard both to before COVID-19 and based on the situation at the time. Thereafter, experiences of perceived insecurity and travel habits in public transport in Malmö were looked at, with questions about whether respondents refrained from travelling by public transport due to concerns about being subjected to crime, at specific times of the day or due to unsafe traffic environment. Respondents could also mark locations on a map with digital pins where they felt insecure. The pins also triggered a pop-up box, where respondents could explain why the location was perceived as unsafe, both through free text and fixed question options.

After that, questions were asked about the city’s major public transport nodes and perceived feelings of insecurity. Hyllie station was included, in addition to the city’s five other major public transport nodes. Photographs were shown from each node in combination with questions about how frequently respondents visit the node, how safe the area is experienced during different times of the day and the reasons for possible feelings of insecurity. The questions included pre-defined response options in combination with an opportunity to provide their comments. For Hyllie station, questions were asked about possible feelings of insecurity for both the station environment and the platform. The final part dealt with background issues that relate to age, gender, level of education, marital status, number of children in the household and main occupation.

The web survey was spread via social media and digital advertising aimed at people in Malmö. The online survey was open for about a month between April and May 2021 and provided a total of 833 responsesFootnote2. A thinning out of the responses was made based on consent or if the survey was interrupted before the last question. After the thinning out, 529 complete responses remained, constituting a non-representative basis.

The emphasis in the analyses is on the subjective dimension, i.e. the individual’s perceived feelings of insecurity, and the study is mainly based on qualitative textual analyses (see Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004). The open comments submitted for Hyllie station have been read through repeatedly and thematized according to various subthemes identified during a step-by-step analysis process. Open comments included various physical and social attributes around public transport nodes. In this study, there is a special focus on open comments about Hyllie station, many of which dealt with the presence of border controls and security personnel.

The proportion of women (n = 385) who participated in the study was higher than the proportion of men (n = 144). The majority were aged between 16-35 years (n = 317), then 36-65 years (n = 191), followed by people over 65 years old (n = 21). Most people worked (n = 298) or studied (n = 167) and the level of education is significantly higher than the average in the city (n = 357, with a post-upper-secondary education, more than three years/postgraduate education).

Results

‘The fence that will stop refugees’: news media depictions of border controls and Hyllie station

On the 4th of January 2016, the newspapers reported on the fence that was put up by the police at Hyllie station, with the aim of ‘distinguishing between domestic and international travellers’ in connection with the new border controls (Västerbottens-Kuriren Citation2016). A few weeks earlier, the media reported, among other things, about how ‘asylum queues make the hunt for terrorists more difficult’ (Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2015a) and that ‘The Migration Agency warns that the refugee crisis is delaying the detection of suspected terrorists’. In the same article, a picture caption claims, ‘The reason why this autumn’s large influx of refugees to Sweden hasn’t made an impression on the statistics of suspected terrorists is that the agency has poor control over who the people who have arrived this year are’. In another article, a picture of the Home Secretary on a visit to Hyllie station can be seen, the headline informs its readers ‘Hunting for terrorists continues in Sweden’ (Dagens industri Citation2015). At the same time, the then prime minister of Sweden was quoted as saying that the intention with the border controls was to ‘have a greatly reduced number of asylum seekers to Sweden—and that other countries need to take their responsibility’ (Norrbottens-Kuriren Citation2015).

Particularly in the early days of border controls, there were reports of how the border controls affected asylum seekers. Foreign news coverage also draws attention to the issue, describing, among other things, the ‘new image of Sweden’, citing ‘Reputable newspapers in the UK, France, Germany and the Netherlands, among others, have analysed and reported on the tightening of Swedish immigration policy, using Malmö as a starting point’ (Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2015b).

After a few of months of border controls (in the first half of 2016), a proposal from the Police was reported to the Swedish Transport Administration. It stated that ‘the police want to build a refugee platform’ between Hyllie and the Öresund Bridge, which would facilitate border controls and make it easier for travellers at Hyllie station (Svenska Dagbladet Citation2016b). However, the proposal was not well received and a week later the Southern Swedish Chamber of Commerce demanded that the new platform proposal be stopped, stating that ‘the establishment of a fixed structure for border control risks hampering growth in Sweden and Denmark’ (Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2016a). There were also reports on the need for resources for border control, with discussion of whether the Home Guard could relieve the police (e.g. Sydsvenskan Citation2017a). At the same time, it was stated early on how ‘the police want military assistance’ (Svenska Dagbladet Citation2015).

Further, it can be noted that border controls in the Öresund region have in various ways attracted media attention over the past few years, both nationally and internationally. In the years following 2015, several articles were published describing how border controls were repeatedly extended. The decisions were justified in the media on the grounds that border controls in general could, for example, ‘combat theft gangs’ and ‘continued raised terrorist threat’ (Svenska Dagbladet Citation2019), or that there ‘continues to be a threat to public order and internal security in Sweden’ (Svenska Dagbladet Citation2018). The effects of the tightened border controls are continuously reported, and the public is constantly updated with peaks in refusals of entry (e.g. Nyhetsbyrån Citation2018). Later, the reintroduction of border controls was justified by the COVID-19 pandemic and the changed level of security in Sweden.

An event on 11 September 2020 was highlighted in several articles and on social media. It relates to how a man was ‘dragged off the train at border control’ (Svt Nyheter Citation2015). A video of the incident was said to have spread quickly becoming viral, and thousands of people signed a protest list against the police. According to the same article, the petition was based on allegations of ‘racial profiling and excessive force by the police’. While on the train, the man was allegedly asked to come along for an in-depth interview, which he allegedly questioned. In a letter from the police, highlighted in the article, the criticism was met with an explanation that all passengers on a train were checked, and if the passenger does not cooperate, the passenger may be asked to get off the train (Polisen Citation2020).

‘The future of the öresund region is at risk’: the issue of free movement

At the same time, in editorials and debate articles, border controls were criticised early on, and decisions questioned, not least in connection to free movement. The future was described as ‘compromised’ (Lundagård Citation2016). There were also many reports of major delays in train services due to border controls, cancellations, and delayed departures (e.g. Sydsvenskan Citation2017b). There were articles about staff shortages and/or a lack of skills to carry out border checks, sometimes resulting in inadequate checks (e.g. Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2017). Some articles referred to high fines for operators if ID checks were not carried out as required (e.g. Aftonbladet Citation2015). In 2022, ‘several years of decline for Öresund traffic’ were reported, with commuter trips falling by up to 45 per cent in the worst periods (e.g. Aftonbladet Citation2022).

From the start, border controls were also described as having led to several ‘online protest petitions’ and the creation of social media groups such as the ‘Öresund Revolution’ (Dagens ETC Citation2016). The group reportedly quickly amassed ‘tens of thousands of outraged Danes and Swedes’ (ibid.), a group that at the time of writing were still active with nearly 22,000 followers.

The complexities of life were portrayed in a way that seemed impossible to put together, with daily cross-border commuters subjected to lengthy checks and delays in train traffic. People considered changing jobs to be closer to home or commuting by car instead of train (e.g. Dagens ETC Citation2016). Later that year, there were several reports of commuters seeking other ways to cross the strait, such as carpooling (e.g. Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2016b), but also that ‘many people stop commuting across the bridge’ as the day-to-day stress ‘became a threat to health’ (Svenska Dagbladet Citation2016a). Some described this development as a ‘threat’ to ‘EU development’ in general, but it also alludes to the fact that the purpose behind the decisions on border controls seemed ‘unclear’ (Helsingborgs Dagblad Citation2016c), and some claimed that border controls were in violation of Swedish/EU law (e.g. Landskrona Posten Citation2023).

Other articles put the events into greater perspective, describing how border controls have been met with ‘criticism from human rights organisations, trade unions, the Law Council and asylum law experts’. In one article, it was linked to a depiction of their feelings when witnessing people who have had to leave the trains. ‘… I cried and tried to keep my mouth shut so my cries wouldn’t be heard. Then the train pulled off…’ (Metro Citation2015). Critical reference was made to the Refugee Convention (1951) and the right to seek asylum. In one editorial, the fences at Hyllie station and Kastrup are likened to ‘…the iron curtain that once began to be built to stop refugees from the east…’ analogous to the escape from communism and the construction of the Berlin Wall ‘…fence and concrete…’. The article ends with a quote from the Swedish journalist Per Svensson; ‘Those who build a wall to shut others out at the same time shut themselves in’ (Aftonbladet Citation2016).

Experiences of Hyllie Station: Results from the online survey

In 2021 experiences of perceived insecurity and travel habits in relation to public transport nodes in Malmö were studied by an online survey, temporary border controls had by this time been a fact back and forth for about five-six years. Various depictions of the presence of border controls and security personnel appeared in the open questions in relation to Hyllie station.

From a more general perspective on how the respondents experience Hyllie station, overall, the respondents felt rather safe at Hyllie station, especially during the daytime. However, many respondents stated that they did not know because they rarely or never remained at the station for long (see ).

Table 1. Responses regarding safety perception.

Further, the respondents had to state reasons for the possible feelings of insecurity at the location through pre-defined response options. The most common reason given in the fixed options for perceived insecurity at the station was the feeling that it was a desolate place or that there was a fear of being subjected to violence or the threat of violence. Respondents also complained about poor lighting, having previously experienced an unpleasant event at the location, and more. Some also cited reasons such as a lot of traffic, poor maintenance (a lot of litter and other waste), high vehicle speeds, and physical obstacles (such as raised kerbs).

When it came to the open questions where the respondents could describe the station, Hyllie station was repeatedly portrayed as a windy place. Several people also described the environment as ‘unattractive’, ‘sterile’, ‘grey’, and ‘boring’. There are many people during the daytime at Hyllie because of the nearby shopping centre and the many trains that come and go throughout all hours of the day. However, the place was described as ‘desolate’ during the evenings and at night, with an ‘absence’ of people during the evenings. One respondent described the place as ‘remote’. Similarly, another respondent described how it can feel unsafe to be there after the larger shopping centre has closed.

‘The guards and police are scary. You want to feel a sense of freedom when you are travelling…’: the presence of border controls and security personnel

The police presence at Hyllie station was portrayed in different ways in the empirical material. Several respondents associated this presence with negative connotations, such as that the ‘guards and police are scary’ or where police and security personnel ‘behave horribly’. The depictions related both to negative behaviour by the security personnel and to how these experiences were based on things that respondents had experienced themselves and things that they had heard other people say.

One respondent felt that a police presence created a harsher climate and a ‘threatening atmosphere’ rather than providing security and described the presence as ‘aggressive’ (Male, 36-40 years old). The same respondent related to how young people may be particularly negatively affected by a police presence. Several respondents linked the presence of the border police with emotions of various kinds such as nervousness, worry, insecurity and discomfort. In some cases, particular attention was made to how the presence of the police can arouse both feelings of security, but also feelings of concern about why they were there.

I always see a lot of police officers there, which I see as positive, but at the same time, it makes me worried about why they need to be there. But mainly positive of course (Female, 16-20 years).

Or to increased feelings of insecurity when the border police are not there.

I think the fact that the police are almost always there (border police) increases the feeling of insecurity when they are sometimes not there (Female, 31-35 years old).

A few individual respondents highlighted how the presence of the border police contributes to increased feelings of security. In this context, for example, one respondent described the police presence as positive, without any further justification as to why it was perceived in this way.

‘The fences are reminiscent of border controls’: concerns about ‘violations’, both for themselves and for others

Some of the respondents further emphasised the importance of border controls and police presence in terms of the risk of increasing concern about ‘violations’, both for themselves and for others. One respondent related in this context to it all being ‘abuse’ and ‘political actions’.

Concern about abuse from the police, against me, but mainly against others. Concern about having to witness and act on abuse by the police, or outright actions but which are political actions. I would feel bad about and have to react to (Female, 31-35 years old).

One person referred to ‘racism’ and another respondent described repeated exposure in the past when the person in question worked in Hyllie, describing how he was ‘repeatedly shouted at and harassed’ by the police (male, 31-35 years). This was still described as creating feelings of nervousness when arriving at the station.

Another respondent portrayed how the police allegedly ran onto the tracks when the respondent was last at the station, and he associated his comment on the place with ‘crime’. However, a few respondents expressed a desire for an even higher presence of guards and police officers within the station area, especially during the evening and at night. Again, varying emotions linked to border controls and the police presence were depicted.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to gain a deeper understanding of media representations and everyday mobility experiences related to border controls in the Öresund region, with a special focus on Hyllie station in the city of Malmö. The results show that border controls and the increased presence of security personnel have caused different types of reactions. Border controls appear to have potentially caused effects at different levels (micro, meso and macro) and may have long-term social, economic, and environmental consequences, which can be seen in terms of uneven mobility (e.g. Cresswell Citation2010; Sheller Citation2016, Citation2018a, Citation2018b) and mobility justice (Sheller Citation2018a, Citation2018b), among others.

Resistance to the border controls was portrayed in the news media in different ways, at the macro level the future of the Öresund region was questioned, as was the issue of whether border controls could affect free movement and exchanges in the region. This discussion can in the broader context be related to the notion of free movement of workers as explained as one of the fundamental principles of the EU, especially since critical events in recent years have come to challenge cross-border commuting and the Free Movement Principle in the EU in various ways (e.g. Evrard, Nienaber, and Sommaribas Citation2020).

In addition, it is crucial to continue to examine how such challenges risk leading to increased fragmentation of our societies, which can also have a significant impact on people’s daily mobility, while at the same time such a development risks creating a continuing trend towards more unequal and uneven mobility. For instance, at the micro level, it was described how border controls complicated the everyday lives of cross-border commuters. The media reported time-consuming checks and delays in train services, resulting in stress and health problems, protests and ‘outraged’ commuters considering changing jobs and avoiding commuting in the region. The vision of growth and integration in the Öresund region seems to be challenged in more ways than one, while the securitisation of our societies continues with the creation of more and more borders, fences, and walls (Vallet Citation2016). In many ways, these challenges are similar, among others, to those discussed by Sheller (Citation2018a, Citation2018b). According to Sheller (Citation2018b), unequal mobility regimes operate at different levels and scales (e.g. macro, meso, micro), and their interconnectedness can be demonstrated through a variety of examples, which were also demonstrated in various ways in this study.

In addition, and from a more environmental and sustainability perspective, previous research has shown how many cross-border journeys in Europe are made by private car, causing several negative externalities, often due to the lack of sufficient public transport (Cavallaro and Dianin Citation2019). In this case, the public transport system could be considered as well developed, but other external circumstances led cross-border commuters to consider abandoning the use of public transport or to stop commuting altogether.

The news media have reported how the negative impact of border controls has led cross-border commuters to consider changing jobs or commuting across the border by car rather than by public transport (and by the train across the Öresund Bridge). At the same time, research reported about major time and economic losses related to the changed conditions for commuting due to the border controls. The uneven conditions for mobility became increasingly prominent, and those who were considered most affected were those who commuted by train rather than those who did so by car. At a macro level, large socio-economic losses due to border controls were also further discussed (see Winter Citation2016).

For further research, and from the perspective of uneven mobilities and mobility justice, it would be relevant to explore the issue in more depth in order to increase our understanding of how the presence of security personnel and border controls in the Öresund region - an expansive region - affects different groups of people at different stages of life, as well as to study the risks of wider societal impacts (including social, environmental and economic). At a micro level, it is also important to have a better understanding of how this type of measure affects people’s attitudes and willingness to commute across the border by public transport. As noted by Lund Thomsen (Citation2020), public and political debates have increasingly focused on security issues and how to protect the EU from external threats and terrorism, leading to mobility ‘under pressure’. Several of the findings in this study point to the same negative trend.

Emotional, in-depth portrayals were also included in media coverage of border controls. At a micro level, tears and upset emotions were portrayed; tears for those with a diminished ability to move more freely, and the uneven distribution of mobility became visible, hierarchies evident and power structures revealed. Accusations were directed against perceived abuses of power and unfair treatment based on factors such as ethnicity. The issue of mobility justice could be raised, while the interrelationship of power and mobility became more and more tangible. People’s mobility capital varies depending on who they are and what their situation in life is like, such as the migrant with a more limited ‘network capital’ (Urry Citation2007) compared to the cross-border commuter; the cross-border commuter using public transport who is more greatly affected by border controls than the one using a private car; and so forth. The uneven distribution of mobility becomes visible – almost palpable – and gives an understanding of mobility justice that goes beyond the sole access to transport, and where hierarchies, and power structures, as well as individual capacity and capital for being mobile become evident.

Furthermore, Hyllie station was depicted in the news media in different ways. Graham (Citation2010, xiii-xiv) described a recurring use of the term ‘war…’ in depictions of the state of cities: ‘…against drugs’ ‘…against terror’ and so on. An increasingly central ongoing issue is the strengthening of national borders, which is, for example, manifested in political measures against migration and extended political power and surveillance. This is something that also blurs the lines between politics and urban life, and thus the lines between power and mobility. The presence of security personnel and border controls were depicted in various ways by those responding to the online survey and were perceived differently by different respondents, which can probably be related to an individual’s attributes and previous experiences. The chosen method and combining portrayals in the news media with the everyday mobility experiences of travellers, allowed for a deeper understanding of the complexity of the studied phenomenon and how border controls can have a broader impact on our societies. However, given that this was a small-scale study, there are several issues that need to be considered for further research at different levels.

The results, for instance, show some gender differences, e.g. women reported feeling less safe than men at Hyllie station, especially during the evening/night. As noted in Stjernborg (Citation2024) these are issues that need to be addressed in further research. As also noted in the same study, working with questions using maps and photos of the public transport nodes proved to be useful and the dissemination via social media worked well. However, it was difficult to reach a variety of groups, and more women than men tended to respond, which is also worth noting for further research.

In addition, the issue of security has come to the fore in recent years as a result of several critical events and increased security threats, not least in Sweden. In November 2023, border controls were reintroduced due to a new security situation in Sweden and an assessed increase in the national terrorist threat level (Regeringskansliet Citation2023). The decision was taken since ‘Sweden has gone from being considered a legitimate target to a prioritised target for terrorist attacks’ (Government Offices of Sweden Citation2023). The new security situation in 2023 has also involved other measures being taken, such as the presence of heavily armed police during the Christmas shopping period, as was the case at the shopping centre adjacent to Hyllie Station. The presence of heavily armed police was discussed in media as well, in combination with descriptions of how the changed situation affects people in different ways (Expressen Citation2023). The assessed need to protect our society seems to be steadily increasing, as claimed by Graham (Citation2010), which continues to challenge our societies and has consequences for urban life in different ways and at different levels.

At the same time, knowledge of actual wider impacts on people’s everyday life mobility seems to be rather lacking, as is the case of our understanding of the wider societal impacts thereof. Again, some scholars maintain that fear of terrorism threatens to ‘undermine democratic governments’ and ‘empower political extremes, and polarize societies’ (Byman Citation2019;1). This also underlines the importance of continuing research on the impact of these developments on our societies on the micro-, meso- and macro levels, as well as further highlighting interrelated and long-term social, economic, and environmental impacts.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the former research assistants; Sofia Rutberg for the valuable contribution to the design of the questionnaire and dissemination of the questionnaire, Felicia Gauffin Jatta for the production of a map for the paper, and Marcella Holtz for photographing and for being helpful in some limited parts of an earlier draft of the paper. The author also wishes to thank the respondents and the reviewers who generously gave their time and shared their thoughts and experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Media Archive, also referred to as ‘Retriever Research’, is a digital news repository that collects printed Nordic newspapers, magazines and business press. The media archive includes media from across the Nordic region and around 100,000 international sources.

2 All participants received written information about the purpose of the study, that no IP addresses or technical information were stored and about how to contact the project leader. To proceed with the web survey, participants had to tick a consent box. They were also informed that they at any time could withdraw from the study and that their responses would be anonymous. They were also given information about where they could access the results of the study. According to the Swedish Law on Ethical Review, the study was not subject to ethical review as it did not collect sensitive personal data or use methods that could physically or psychologically affect or harm the participants. As no participant is identifiable, written consent for publication was not required and was therefore not obtained from the participants.

References

- Adey, P. 2017. Mobility. 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315669298.

- Aftonbladet 2016. “Staketet som ska stoppa flyktingar” ["The fence to stop refugees”]. https://www.aftonbladet.se/ledare/a/WLaw6j/staketet-som-ska-stoppa-flyktingar

- Aftonbladet 2015. “Missad id-kontroll kan ge böter på 50 000 kr” [”Missed ID check can result in a fine of SEK 50,000”]. https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/samhalle/a/BJz8M9/missad-id-kontroll-kan-ge-boter-pa-50000-kr

- Aftonbladet 2022. “Flera års ras för trafiken över Öresund” ["Several years of collapse for traffic across the Öresund”] https://www.aftonbladet.se/minekonomi/a/qWxPLo/flera-ars-ras-for-trafiken-over-oresund

- Barajas, J. M., and W. Wang. 2023. "Mobility Justice in Rural California: Examining Transportation Barriers and Adaptations in Carless Households.” UC Davis: National Center for Sustainable Transportation. http://doi.org/10.7922/G2X928NC.https://escholarship-org.ludwig.lub.lu.se/uc/item/0dv3b769.

- Beauchamps, M., M. Hoijtink, M. Leese, B. Magalhães, S. Weinblum, and S. Wittendorp. 2017. “Introduction: Security/Mobility and the Politics of Movement.” In Security/Mobility: Politics of Movement, edited by M. Leese & S. Wittendorp, 1–14. Manchester University Press, UK. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1wn0s9r.6.

- Bohman, H., J. Ryan, V. Stjernborg, and D. Nilsson. 2021. “A Study of Changes in Everyday Mobility During the Covid-19 Pandemic: As Perceived by People Living in Malmö, Sweden.” Transport Policy 106: 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.03.013.

- Brambilla, C. 2023. “Rethinking Borders Through a Complexity Lens: Complex Textures Towards a Politics of Hope.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2023.2289112.

- Buch, T., T. Dall Schmidt, and A. Niebuhr. 2009. “Cross‐border commuting in the Danish‐German border region ‐ integration, institutions and cross‐border interaction.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 24 (2): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2009.9695726.

- Byman, D. 2019. “Terrorism and the Threat to Democracy.” Policy Brief, Democracy & Disorder. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/FP_20190226_terrorism_democracy_byman.pdf

- Cass, N., E. Shove, and J. Urry. 2005. “Social Exclusion, Mobility and Access.” The Sociological Review 53 (3): 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00565.x.

- Cavallaro, F., and A. Dianin. 2019. “Cross-Border Commuting in Central Europe: Features, Trends and Policies.” Transport Policy 78: 86–104. Volume ISSN 0967-070X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.04.008.

- Ceccato, V., L. Langefors, and P. Näsman. 2021. “The Impact of Fear on Young People’s Mobility.” European Journal of Criminology 20 (2): 486–506. 14773708211013299. https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708211013299.

- Ceccato, V., and A. Loukaitou-Sideris. 2021. “Fear of Sexual Harassment and Its Impact on Safety Perceptions in Transit Environments: A Global Perspective.” Violence Against Women 28 (1): 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801221992874.

- Church, A., M. Frost, and K. Sullivan. 2000. “Transport and Social Exclusion in London.” Transport Policy 7 (3): 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-070X(00)00024-X.

- Condon, S. A., M. Lieber, and F. Maillochon. 2007. “Feeling Unsafe in Public Places: Understanding Women’s Fears.” Revue Francaise De Sociologie 48: 101–128. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfs.485.0101.

- Chow, P. S. 2021. “A Region Under Transformation: From 'Øresund’ to 'Greater Copenhagen.” In: Transnational Screen Culture in Scandinavia. Palgrave European Film and Media Studies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85179-8_3.

- Consoli, L., C. Burton-Jeangros, and Y. Jackson. 2022. “Transitioning out of illegalization: Cross-border mobility experiences.” Frontiers in Human Dynamics 4: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2022.915940.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. 1st ed. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

- Cresswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407.

- Dagens ETC 2016. “Id-kontrollerna på Öresundsbron möter massiva protester” [“ID Checks on the Öresund Bridge Meet Massive Protests”]. https://www.etc.se/inrikes/id-kontrollerna-pa-oresundsbron-moter-massiva-protester, published 2016-01-04.

- Dagens industri 2015. “Jakt På Terrorister Fortsätter i Sverige.” [“Hunting for Terrorists Continues in Sweden”].

- Das Neves, B., C. Unsworth, and C. Browning. 2023. “Being Treated like an Actual Person’: Attitudinal Accessibility on the Bus.” Mobilities 18 (3): 425–444. Volume Issue p https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2022.2126794.

- Degerman, H. 2021. “Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden.” Infrastructures 6 (8)106. : 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6080106.

- Edzes, A. J. E., J. van Dijk, and L. Broersma. 2022. “Does Cross-Border Commuting Between EU-Countries Reduce Inequality?” Applied Geography 139, p. 1-13: 102639. Volume ISSN 0143-6228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102639.

- EUR-Lex n.d. “Schengen Agreement and Convention.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/schengen-agreement-and-convention.html

- EU 2023. “Cross-Border Commuters.” https://europa.eu/youreurope/citizens/work/work-abroad/cross-border-commuters/index_en.htm

- European Commission n.d,a. “Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion.” https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=457

- European Commission n.d, b. “Migration and Home Affairs.” https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/schengen-area_en

- Evrard, E., B. Nienaber, and A. Sommaribas. 2020. “The Temporary Reintroduction of Border Controls Inside the Schengen Area: Towards a Spatial Perspective.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 35 (3): 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1415164.

- Expressen 2023. “Tungt beväpnad polis övervakar julhandeln i Malmö” ["Heavily armed police monitor Christmas shopping in Malmö”]. https://www.expressen.se/nyheter/sverige/abbe-och-markus-patrullerar-emporia-med-forstarkningsvapen/

- Flipo, A., N. Ortar, and M. Sallustio. 2023. “Can the Transition to Sustainable Mobility be Fair in Rural Areas? A Stakeholder Approach to Mobility Justice.” Transport Policy 139: 136–143. Volume Pages https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.06.006.

- Government Offices of Sweden 2023. “Swedish Security Service Raises Terror Threat Level.” https://www.government.se/articles/2023/08/swedish-security-service-raises-terror-threat-level/

- Graham, S. 2010. Cities under Siege: The New Military Urbanism. London; New York: Verso.

- Graneheim, U. H., and B. Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24 (2): 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Greater Copenhagen n.d. “Together for Economic Growth & Development.” https://www.greatercph.com/en

- Hansen, P. A., and G. Serin. 2007. “Integration Strategies and Barriers to Co‐operation in Cross‐Border Regions: Case Study of the Øresund Region.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 22 (2): 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2007.9695676.

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2015a. “Asylkö Försvårar Terroristjakten.” [“Asylum Queue Complicates Terrorist Hunt”].

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2015b. “Rapporter Ger En Ny Sverigebild.” ["Reports Provide a New Picture of Sweden.”].

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2016a. “Handelskammaren Kräver Stopp För Ny "Flyktingperrong" ["Chamber of Commerce Calls for an End to New 'Refugee Platform’”]. https://www.hd.se/2016-03-16/handelskammaren-kraver-stopp-for-ny-flyktingperrong

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2016b. “Pendlarna Som Söker Nya Vägar.” [Commuters looking for new ways].

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2016c. “Revisorer Risar Regeringen. Gränskoll Har Oklart Syfte.” [“Auditors Criticise the Government. Border Controls have Unclear Purpose”]

- Helsingborgs Dagblad 2017. “Brist På Poliser Stoppar Upp Gränskontroller.” [“Lack of Police Officers Stops Border Controls.”].

- Hidayati, I., W. Tan, and C. Yamu. 2021. “Conceptualizing Mobility Inequality: Mobility and Accessibility for the Marginalized.” Journal of Planning Literature 36 (4): 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211012898.

- Hospers, G.-J. 2006. “Borders, Bridges and Branding: The Transformation of the Øresund Region into an Imagined Space.” European Planning Studies 14 (8): 1015–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310600852340.

- Jackson, J., and I. Gouseti. 2012. “Fear of Crime: An Entry to the Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology.” In Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology, edited by J. Mitchell Miller. Wiley-Blackwell, UK. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2118663.

- Kappes, C., W. Greve, and S. Hellmers. 2013. “Fear of Crime in Old Age: Precautious Behaviour and its Relation to Situational Fear.” European Journal of Ageing 10 (2): 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0255-3.

- Kathiravelu, L. 2021. “Introduction to Special Section 'Infrastructures of Injustice: Migration and Border Mobilities.” Mobilities 16 (5): 645–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1981546.

- Keane, C. 1998. “Evaluating the Influence of Fear of Crime as an Environmental Mobility Restrictor on Women’s Routine Activities.” Environment and Behavior 30 (1): 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916598301003.

- Kuhn, T. 2012. “Why Educational Exchange Programmes Miss Their Mark: Cross‐Border Mobility, Education and European Identity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (6): 994–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02286.x.

- Landskrona Posten 2023. “Gränskontrollerna Kan Snart Förklaras Olagliga.” [“Border Controls Could soon be Declared Illegal.”].

- Lundagård 2016. “Öresundsregionens framtid äventyrad” [”Future of the Öresund region at risk”]. https://www.lundagard.se/2016/11/23/debatt-oresundsregionens-framtid-aventyrad/

- Lund Thomsen, T. 2020. “EU Mobility under Pressure in an Increasingly Closed Europe.” In Changes and Challenges of Cross-Border Mobility within the European Union, edited by T. Thomsen Lund. Berlin: Peter Lang Verlag. https://doi.org/10.3726/b17336.

- Malmö Stad 2021. “Fortsatt högt byggtempo i Hyllie” [“Construction pace remains high in Hyllie”]. https://malmo.se/Aktuellt/Artiklar-Malmo-stad/2021-03-24-Fortsatt-hogt-byggtempo-i-Hyllie.html

- Malmö Stad 2022. “Hyllie.” https://malmo.se/Stadsutveckling/Stadsutvecklingsomraden/Hyllie.html, accessed 2022-11-25.

- Malmö Stad 2023. “Öresundssamarbetet” ["The Øresund Co-operation”]. https://malmo.se/Sa-arbetar-vi-med…/Omvarld/Nationellt-och-regionalt-samarbete/Oresundssamarbetet.html

- Massey, D. 2006. “The Geographical Mind.” In Secondary Geography Handbook, edited by D. Balderstone, 46–51. UK: Geographical Association.

- Mazzoni, D., C. Albanesi, P. D. Ferreira, S. Opermann, V. Pavlopoulos, and E. Cicognani. 2018. “Cross-border mobility, European identity and participation among European adolescents and young adults.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 15 (3): 324–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1378089.

- Medeiros, E. 2019. “Cross-Border Transports and Cross-Border Mobility in EU Border Regions.” Case Studies on Transport Policy 7 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2018.11.001.

- Medeiros, E., M. Guillermo Ramírez, G. Ocskay, and J. Peyrony. 2021. “Covidfencing Effects on Cross-Border Deterritorialism: The Case of Europe.” European Planning Studies 29 (5): 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1818185.

- Metro 2015. “Jag Gråter När Jag Ser Polisen Tvinga Flyktingpojken Att Gå Av Tåget.” [“I cry when I see the police forcing the refugee boy to get off the train”].

- Moderaterna 2023. “Krafttag Mot Gängkriminaliteten.” [“Taking action against gang crime”]. https://moderaterna.se/var-politik/gangkriminalitet/

- Moderaterna, Liberalerna Sverigedemokraterna, Kristdemokraterna. 2022. “Tidöavtalet - Överenskommelse för Sverige” ["Tidö Agreement - Agreement for Sweden”]. https://www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/tidoavtalet-overenskommelse-for-sverige-slutlig.pdf

- Nordic Co-operation n.d. “Nordic Agreements and Legislation, Nordic Agreements and Legislation.” https://www.norden.org/en/information/nordic-agreements-and-legislation

- Norrbottens-Kuriren 2015. “Stor Oenighet Om Den Nya Flyktingpolitiken.” [“Major disagreement on the new refugee policy”].

- Nyhetsbyrån, T. 2018. “Fler Effekter Av Skärpt Gränskontroll.” [“More effects of stricter border control”].

- Øresundsinstituttet 2022. “Fakta: Gräns- och ID-kontroller mellan Danmark och Sverige sedan 2015.” ["Facts: Border and ID checks between Denmark and Sweden since 2015”]. https://www.oresundsinstituttet.org/fakta-granskontroller/

- Øresundsinstituttet n.d. “FAKTA: Pendlingen över sundet.” [“FACTS: Commuting across the Öresund”]. https://www.oresundsinstituttet.org/fakta-pendlingen-over-sundet/

- Oxford Reference 2023. “Social Justice.” https://www.oxfordreference.com

- Parenti, A., and C. Tealdi. 2021. “Cross-Border Labour Mobility in Europe: Migration Versus Commuting.” In The Economic Geography of Cross-Border Migration. Footprints of Regional Science, edited by K. Kourtit, B. Newbold, P. Nijkamp, M. Partridge. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48291-6_9.

- Persson, C., and H.-Å. Persson. 2021. The Oresund Experiment. Making a Transnational Region. Ystad: Ängavången AB.

- Polisen 2020. “Gränspolisen bemöter kritik efter id-kontroll.” [“Border Police respond to criticism after ID checks”]. https://polisen.se/aktuellt/nyheter/2020/september/granspolisen-bemoter-kritik-efter-id-kontroll/

- Rader, N. E., D. C. May, and S. Goodrum. 2007. “An Empirical Assessment of the "Threat of Victimization:" Considering Fear of Crime, Perceived Risk, Avoidance, and Defensive Behaviors.” Sociological Spectrum 27 (5): 475–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170701434591.

- Regeringskansliet 2023. “Återinförd tillfällig gränskontroll vid inre gräns.” [“Reintroduction of temporary border control at internal borders”]. https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2023/11/aterinford-tillfallig-granskontroll-vid-inre-grans/

- Region Skåne 2016. “Skånetrafikens tågresande 2016”, https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/hassleholms_kommun/documents/skaanetrafikens-taagresande-2016-66124, accessed 2024-05-31.

- SCB (Statistics Sweden). 2022. “Sveriges befolkning.” [“Population of Sweden”]. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/sveriges-befolkning/

- Schwanen, T., and F. Ziegler. 2011. “Wellbeing, Independence and Mobility: An Introduction.” Ageing and Society 31 (5): 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001467.

- Sigalas, E. 2010. “Cross-Border Mobility and European Identity: The Effectiveness of Intergroup Contact During the ERASMUS Year Abroad.” European Union Politics 11 (2): 241–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510363656.

- Sheller, M. 2016. “Uneven Mobility Futures: A Foucauldian Approach.” Mobilities 11 (1): 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2015.1097038.

- Sheller, M. 2018a. “Theorising Mobility Justice. Dossiê - Mobilidades.” Tempo Social 30 (2): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2018.142763.

- Sheller, M. 2018b. Mobility Justice - the Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. Verso Books, UK.

- Skånetrafiken 2011. “Värmande nyheter på Hyllie station.” [“Warming news at Hyllie station”] https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/skanetrafiken/news/vaermande-nyheter-paa-hyllie-station-30653

- Sohn, C. 2023. “The Impact of Rebordering on Cross-Border Cooperation actors’ Discourses in the Öresund Region. A Semantic Network Approach.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2023.2266436.

- Statistics Denmark 2023. “Hvem pendler fra Sverige til Danmark?” [“Who is Commuting from Sweden to Denmark?”]. https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/nyheder-analyser-publ/Analyser/visanalyse?cid=51280

- Stjernborg, V. 2024. “Triggers for Feelings of Insecurity and Perceptions of Safety in Relation to Public Transport; the Experiences of Young and Active Travellers.” Applied Mobilities 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2024.2318095.

- Stjernborg, V., M. Tesfahuney, and A. Wretstrand. 2015. “The Politics of Fear, Mobility, and Media Discourses: A Case Study of Malmö.” Transfers 5 (1): 7–27. https://doi.org/10.3167/TRANS.2015.050103.

- Svenska Dagbladet 2015. “Polisen vill ha militär hjälp.” [“The police want military assistance.”]. published 2015-12-20.

- Svenska Dagbladet 2016a. “Många slutar att pendla över bron.” [“Many people stop commuting over the bridge”].

- Svenska Dagbladet 2016b. “Polisen vill bygga flyktingperrong.” [“Police want to build refugee platform”]. https://www.svd.se/a/a0e83402-7309-4d6a-a670-74dc6b41fecb/polisen-vill-bygga-flyktingperrong

- Svenska Dagbladet 2018. “Förlängd inre gränskontroll [Prolonged internal border control], published 2018-11-09.

- Svenska Dagbladet 2019. “Gränskontroller förlängs: "Kan bekämpa stöldligor." ["Border controls extended: 'Can fight theft gangs’”]. https://www.svd.se/granskontroll-forlangs-ett-halvar

- Svt Nyheter 2015. “Släpades av tåget vid gränskontroll – tusentals har skrivit under protest mot polisen.” [“Dragged off train at border control - thousands have signed protest against police”]. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/skane/slapades-av-taget-vid-granskontroll-tusentals-har-skrivit-under-protest-mot-polisen

- Sydsvenskan 2017a. “Avlasta polisen genom att utnyttja hemvärnet” [“Relieve the police by utilising the Home Guard”]. https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2017-02-17/avlasta-polisen-genom-att-utnyttja-hemvarnet

- Sydsvenskan 2017b. “Skärpta gränskontroller vid Hyllie gav 795 försenade tåg.” [“Tighter border controls at Hyllie resulted in 795 delayed trains”]. https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2017-11-10/skarpta-granskontroller-vid-hyllie-gav-795-forsenade-tag

- Swedish Police 2023. “Sprängningar och skjutningar - polisens arbete.” ["Explosions and shootings - police work”]. https://polisen.se/om-polisen/polisens-arbete/sprangningar-och-skjutningar/

- Swedish Security Service 2023. “Security Situation Worsens as Image of Sweden Changes, Security Situation Worsens as the Image of Sweden Changes.” https://sakerhetspolisen.se/ovriga-sidor/other-languages/english-engelska/press-room/news/news/2023-07-26-security-situation-worsens-as-the-image-of-sweden-changes.html

- United Nations. 1951. “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (189 U.N.T.S. 150, Entered into Force April 22, 1954).”

- Urry, J. A. 2007. “Mobilities.” ISBN: 978-0-745-63419-7, Polity.

- van Holstein, E., I. Wiesel, and C. Legacy. 2022. “Mobility justice and accessible public transport networks for people with intellectual disability.” Applied Mobilities 7 (2): 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2020.1827557.

- Vallet, E. 2016. Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity? London: Routledge.

- Västerbottens-Kuriren 2016. “Polisstaket På Hyllie Station.” [”Police Fence at Hyllie Station”].

- Walters, W. 2006. “Border/Control.” European Journal of Social Theory 9 (2): 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431006063332.

- Westlund, H., and S. Bygvrå. 2002. “Short‐Term Effects of the Öresund Bridge on Cross-Border Interaction and Spatial Behavior.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 17 (1): 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2002.9695582.

- Winter, K. 2016. “Ny vardag för pendlarna över Öresund; Konsekvenser av införandet av ID-kontroller mellan Danmark och Sverige, del 1.” https://www.oresundsinstituttet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20160610-Analys-ID-kontroller-Karin-Winter-webb.pdf

- Winter, K. 2023. “Dubbelexponerad Orättvisa: mobilitetsfrågor i Krisernas Tidevarv.” In Rättvist Resande; Villkor, Utmaningar Och Visioner För Samhällsplaneringen, edited by T. Joelsson, M. Henriksson, & D. Balkmar. Boxholm, Seden: Linnefors förlag. Open access. https://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1815683/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Appendix A

Table A1. Newspaper articles categorized in different themes.