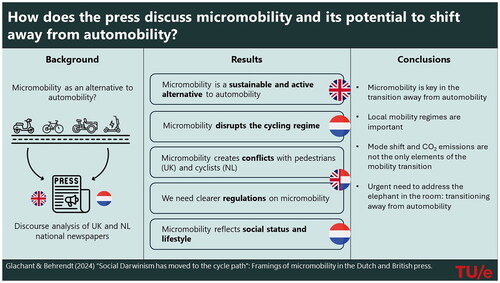

Abstract

The media’s agenda-setting function in terms of selecting and presenting issues to the public and policymakers is crucial for the urgently needed transition towards more sustainable mobilities, including how the media frames micromobility. Media framings are representations, a key component of mobility, alongside physical movement and practice, all involving power relations. Drawing on mobility studies and discourse analysis, this paper compares how the Dutch and British national press frame micromobility. We identify five frames of micromobility: (1) as sustainable and active shift, predominant in the British press; (2) as disruption of the Dutch pedal-powered cycling regime; (3) as catalyst of conflicts in public space, both in the Dutch and British press; (4) around the shortcomings of micromobility regulations in both contexts; and (5) concerning lifestyle in the Dutch context. We demonstrate how media framings of micromobility only limitedly discuss its potential to transition from automobility, focusing instead on social status changes, regulatory challenges, and conflicts between different forms of micromobility, that are already marginalized. Our findings emphasize the urgency to put the transition from automobility—the elephant in the room—on the agenda.

Introduction

‘Social Darwinism has moved to the cycle path’ reads the title of a recent Dutch newspaper article, highlighting conflicts between modes – often key to how the media portray micromobility (Giesen Citation2022). The term ‘micromobility’ has recently gained traction in academic, business, and policy discussions, particularly with the rise of shared bicycle and scooter schemes across American, Asian, and European cities (ITF Citation2020; O’hern and Estgfaeller Citation2020). Micromobility encompasses small human-powered or partially or fully electric vehicles operating at low speeds, including bicycles, scooters, mopeds, cargo bikes, and three- and four-wheeled light vehicles (Behrendt et al. Citation2023). Micromobility is often regarded as a way to decarbonize transport and improve living environments. However, it has raised concerns regarding public space conflicts and safety.

Drawing on mobilities scholarship, this paper considers (micro)mobility beyond specific mobility modes to include embodied and socially constructed practices and representations. This involves power relations and politics in mobility (Cresswell, Citation2010). Representation as a component of mobilities entails how power and politics are discursively articulated, by whom, and which narratives are associated with specific actors, for example in the press.

As the term suggests, micromobilities should be understood in the context of the dominant automobility system: not only automobiles, but also the related industries, infrastructure, cultures, consumption, and practices (Urry Citation2004). Together they shape the ‘specific character of domination’ of automobility which needs to be transformed toward more sustainable mobility (Urry Citation2004, 25). If representations are central to mobilities – and micromobilities have the potential to move us away from automobility – they may yield important insights for transitions towards more sustainable mobilities.

Scholars have extensively examined micromobility as a sustainable alternative to automobility, especially for short trips and in combination with public transit (Oeschger, Carroll, and Caulfield Citation2020). Despite public transit’s important role in the transition toward more sustainable mobilities, this paper focuses on individual modes. However, some studies question micromobilities’ positive impact on ecological sustainability (Şengül and Mostofi Citation2021; Abduljabbar, Liyanage, and Dia Citation2021). In addition, previous research has examined human-powered micromobilities as forms of active travel, offering health benefits, in contrast with motorized modes (Cook et al. Citation2022; Cairns et al. Citation2015). Debates persist regarding micromobility’s sustainability and health benefits, alongside public space use and safety issues.

Safety concerns and policy implications surrounding micromobility have been a major concern, in both research and public debates. Shared micromobility schemes in cities have impacted access to public space, particularly for vulnerable groups like people with disabilities (Bennett et al. Citation2021). Previous studies focused on conflicts regarding walking and e-scooters (Tuncer et al. Citation2020; Fitt and Curl Citation2020) and privately owned and shared bicycles (Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong Citation2020). Research highlights the importance of appropriate regulations to limit conflicts induced by shared micromobility modes (Gössling Citation2020; Latinopoulos, Patrier, and Sivakumar Citation2021). These controversies are also reflected in media coverage analyzed in this article.

Most social science micromobility-related scholars focus on safety, regulations, user behavior, and environmental impact (O’hern and Estgfaeller Citation2020; Şengül and Mostofi Citation2021). Few have investigated how micromobility is discursively constructed through media representation. Those who have (Gössling Citation2020; Lipovsky Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Rissel et al. Citation2010; Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong Citation2020) examine either one specific theme, mode, or country. While some humanities studies have explored representations of micromobility modes like cycling (e.g. Oldenziel and Albert de la Bruhèze (Citation2011)), they do not use the term ‘micromobility’ or explore its potential for shifting away from automobility. This paper addresses this gap by examining media representations of micromobility.

This study analyzes media representations of micromobility through the concept of framing. Media shape public opinion by using framing to accentuate particular topics or highlight perspectives of specific actors (Linström and Marais Citation2012). Framing is thus central to how social phenomena, like mobilities, are represented. We combine this approach with a mobilities perspective, as we regard representation as a key component of mobility, alongside physical movement and practice, all involving power relations (Cresswell Citation2010). By studying the media framings of micromobility, we aim to uncover to what extent micromobility representations in the press – imbued in power dynamics – challenge the automobility system.

This paper conducts a comparative analysis to understand how micromobility is represented in the print media in the European context. Specifically, we focus on the Netherlands and the UK, to compare a mature cycling country (Harms, Bertolini, and Te Brömmelstroet Citation2014) with a country where cycling has a marginal status (Pucher and Buehler Citation2008) while in both countries the automobility regime dominates. Recently, cities in both countries have experienced the growth of micromobility-sharing schemes. This has generated strong public and policy debates.

The research question guiding this paper is: How is micromobility framed in the Dutch and British print media, including its potential to shift away from automobility?

The next section presents the theoretical background of this study, drawing on mobility scholarship and media and communication studies. In the third section, we present our cases and methodological approach. Sections 4, 5, and 6 detail the five frames resulting from our analysis, grouped into three topics. We draw our conclusions in the final section.

Theoretical background

This section discusses studies of the representation of micromobility in the press. This is followed by a discussion of how framing works in such media representations.

Representations and framings of (micro)mobility

Few studies have addressed the representation of micromobility in the print media, all with a focus on specific modes. The growth of e-scooter sharing schemes prompted some research on media representation. Gössling (Citation2020) conducted a content analysis of how local newspapers represented the issues and challenges with e-scooters in several cities across the US, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand and discussed policy responses to promote e-scooter mobility, while also reflecting on how e-scooters may become a transformative mobility innovation. Lipovsky (Citation2020b) analyzed news media representation of shared e-scooters in Paris, finding in contrast with Lipovsky’s (Citation2020a) case of the representation of cycling, that e-scooters are mostly framed negatively. The negative responses focused on the dockless rental schemes’ impact on public space, sustainability, and users’ behavior.

Some scholars have also explored the representation of cycling. Lipovsky (Citation2020a) studied how cycling is represented in two national French newspapers and found a positive framing of cycling due to its social, economic, environmental, and health benefits. These findings for Paris confirm Rissel et al. (Citation2010, 7)’s analysis of Australian newspapers, except for the media representations of cyclists, who were considered ‘irresponsible, law-breaking, dangerous ‘others’ who behave badly’. Te Brömmelstroet, Boterman, and Kuipers (Citation2020, 114) discuss the representation of cargo bike users: ‘Particularly in conservative media, the cargo bike is often used as a shorthand for anything that is despised: assertive mothers, emasculated men, naïve and privileged urban liberals’. Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong (Citation2020, 45) have also analyzed the predominately negative press discourse around the introduction of dockless bike-share in Amsterdam, and points to the competition between owned and shared forms of cycling within the subaltern regime of cycling ‘itself under pressure from and in competition with the dominant regime of automobility’.

Framing in the press

Media outlets have the power to set agenda as much as they do report: in selecting and presenting issues to the public and policymakers, journalists and their editorial teams make choices about which information to share, how to present it, which sources to use, and which specific facts to highlight (Crow and Lawlor Citation2016). The media also frames and constructs narratives; they give meaning to a situation to shape readers’ interpretation of reality (Crow and Lawlor Citation2016).

We use Entman’s definition of framing: ‘To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendations for the item described’ (Entman Citation1993, 52). Frames are operationalized through framing devices, for instance: wording, rhetorical tools, writing style, arguments, or visuals (Linström and Marais Citation2012). In addition, the study of frames involves examining what is included and what is excluded from news stories (Connolly-Ahern and Broadway Citation2008). In this paper, we use issue-specific frames (Matthes Citation2009) to uncover how micromobility is framed in British and Dutch national press. Our analysis selects frames inductively.

Media discourse contributes to how people construct meaning, while some actors also co-construct media discourse (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989), often the most vocal, resourceful, and powerful. They strategically discuss issues by positioning themselves in debates. Hence, looking at the actors represented in the media, directly, through quotes or interviews, or indirectly, provides a context for understanding how the public views issues (Connolly-Ahern and Broadway Citation2008). This paper thus considers which actors are represented and which actors are absent or marginalized. Moreover, the extent to which a press article reflects the author’s position varies. How press articles frame issues depends on social norms and values, organizational constraints, pressure from interest groups, and so on (Linström and Marais Citation2012). In sum, framing revolves around the selection of specific aspects of reality, to give meaning to social phenomena. This paper uses the concept to understand how far the aspects of micromobility presented in the press challenge automobility.

Methodology

This section presents the two studied cases, the Netherlands and the UK, and the rationale for selection. We then elaborate on the process of data collection and discourse analysis as a method to analyze framings.

Case selection and context

The Netherlands and the UK were selected as cases for their contrasting mobility contexts but also their similarities: both countries show hesitancy to fully integrate all types of micromobilities into their transport systems. The Netherlands is renowned for its high cycling share of 28% of all trips in 2019 (De Haas, Hamersma, and Hoogte Citation2020). Dutch cycling covers various types like the increasingly popular cargo bikes and e-bikes. E-bikes sales doubled between 2016 and 2020 (BOVAG Citation2022). Other micromobility modes, like mopeds, have long been a part of the Dutch transport system (Dekker Citation2021) and have resurfaced with the introduction of rental schemes in 2017. Authorities, however, have sought to heavily regulate shared schemes with a quota and permit system, particularly after the Amsterdam-based shared bicycle ban in 2017 (Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong Citation2020). Some micromobility, like e-scooters, is prohibited on Dutch roads, except for ‘special mopeds’ which include e.g. Segways and Kickbikes (Knoope and Kansen Citation2021). This exemption led to forceful policy debates, notably after the 2018 accident involving the Stint—a vehicle to shuttle kids whose form resembled both a cargo bike and a Segway—resulting in the deaths of four children and intense political debates about safety and regulation of new micromobilities (Onderzoeksraad Voor Veiligheid Citation2019).

In contrast, the UK is a country with a low cycling share of 0.9% of all trips in 2019 (Cycling UK Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic marked a discursive shift when authorities sought—at least temporarily—to promote cycling and walking as a healthy alternative for collective transit modes (Department for Transport Citation2020). Though still small in overall numbers, e-bikes have grown popular with a 60% sales growth since March 2020 (Bicycle Association Citation2021). British cities have installed—docked and dockless—bicycle hire schemes. Dockless schemes expanded rapidly, though some were discontinued in 2019 because of vandalism and theft (McIntyre and Kollewe Citation2019). As for e-scooters, they became partially legal as part of government-led trials in some cities in 2020. Privately owned scooters are illegal on British roads, although they are widely used. Both privately owned and shared mopeds are significantly less common in the UK compared to the Netherlands (ACEM Citation2017; Invers Citation2022).

Data collection and analysis

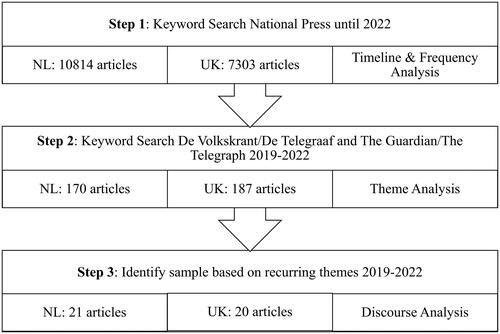

The data used in this study consists of articles published in Dutch and British national newspapers, chosen to examine framing from a perspective accessible to broader audiences. Our data collection and analysis occurred in three steps as presented in .

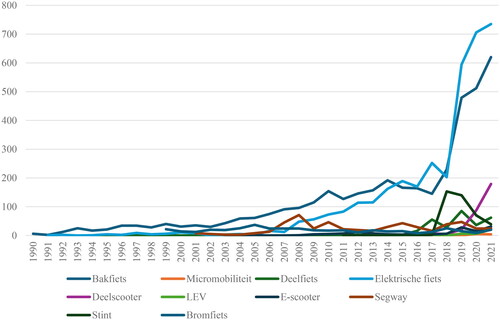

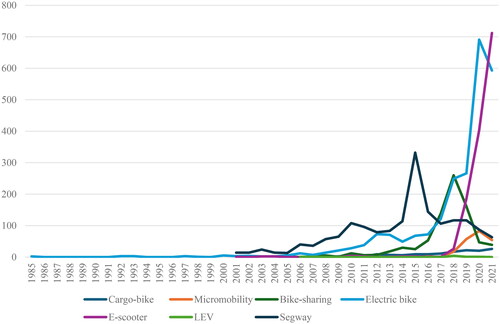

In step 1, we searched Nexis Uni, a paid online database of national newspapers worldwide, using the keywords indicated in . These terms derive from the introduction’s definition of micromobility but also include context-specific terms (e.g. Stint/NL, LEV/UK). We analyzed the data by creating timelines that display the frequency of articles mentioning the selected keywords over time for each case (see Appendix 1). This allowed for the identification of relevant newspapers and a timeframe for step 2.

Table 1. Keywords for step 1 data collection.

In step 2, we narrowed down the sample to two newspapers per country: De Telegraaf and De Volkskrant for the Netherlands, and The Telegraph and The Guardian for the UK; all for 2019–2022. This choice is guided by three elements: (1) step 1 showed that these newspapers discuss micromobility consistently over time. (2) They are widely read in their respective countries (Bakker and Vasterman Citation2008; Firmstone Citation2018). (3) These newspapers are ideologically contrasting and relatively comparable: The Telegraph and De Telegraaf are socially and politically conservative, while The Guardian and De Volkskrant lean towards the left of the political spectrum (Bakker and Vasterman Citation2008). We analyzed the data by identifying recurring themes across modes and countries, inductively from the data and deductively by drawing on the theoretical background.

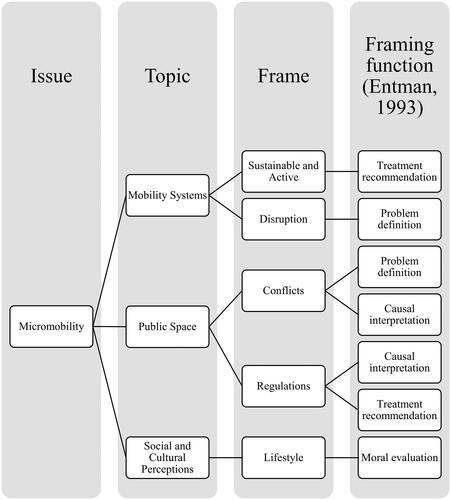

In step 3, we narrowed down the sample to 21 (NL) and 20 (UK) articles for 2019–2022 (see dataset for the list). The process involved excluding accident, theft, and vandalism reports and articles that did not discuss micromobility in depth. Subsequently, we selected articles representative of themes and modes identified in step 2 and those we deemed richest for discourse analysis. The material is analyzed holistically to identify frames, engaging extensively with the texts (Connolly-Ahern and Broadway Citation2008). Subsequently, we coded the material (see ) for (a) the identified themes and sub-themes in step 2, (b) the mentioned types of actors, their relationships, and how perspective is represented, and (c) technical and written framing devices (Linström and Marais Citation2012), using the software NVivo. For (b), we used a list of actors composed deductively and inductively. We then refined themes and sub-themes and looked for relationships among them. Lastly, we integrated these themes into a ‘central story’ consisting of five frames, that fall into three topics that structure the results. gives an overview of topics, frames, and their framing functions. Longitudinal insights are captured in our dataset and in article codes used in-text.

Figure 2. Overview of topics, frames, and Entman’s (Citation1993) framing functions found in step 3.

Table 2. Codes used in step 3.

Although the discourse analysis method seemed suitable, it also has limitations. Defining the frames is subjective, potentially hindering the external validity of the study (Linström and Marais Citation2012; Schäfer and O’Neill Citation2017). To counter this tendency, we assessed recurring themes in a larger sample before analyzing media discourse (steps 1 and 2).

Framing micromobility’s impact on mobility systems

This section presents the result of our discourse analysis of Dutch and British national press that have micromobility’s impact on mobility systems as key topic, with two associated frames: the Sustainable and Active frame, mainly in the UK, and the Disruption frame, mainly in the Netherlands.

The Sustainable and Active frame

The Sustainable and Active frame discusses micromobility in terms of its potential to disrupt the car-centric mobility regime. This frame dominates in the UK with its less mature cycling context, especially in the ideologically progressive Guardian (see dataset on frame coverage per newspaper). E-micromobility modes are prevalent, framed as a sustainable change opportunity by operators, cycle and automobile industry actors, and government actors who emphasize the electrification of (micro)mobility as a key to sustainable mobility futures. Micromobility is also presented as an active alternative to cars—a frame contested in the Dutch press because of its mature cycling culture, but presented in the British press as a narrative of technological substitution to replace automobility and address social challenges of sustainability and public health. This reflects Entman’s (Citation1993) ‘treatment recommendation’ framing function. Despite the user focus of the active travel narrative, users are involved in this frame to a lesser extent and typically projected.

Micromobility as an opportunity for sustainable change

In this Sustainable and Active frame, e-micromobility is positioned as an opportunity for sustainable change in the mobility regime. Media depicts e-micromobility as replacing cars for short trips, limiting CO2 emissions and congestion, and improving living environments. It uses the terminology of change like ‘transformative’, ‘paradigm shift’, and ‘revolution’ (UK-TG-1-20; 5-20; UK-TT-3-20). Just as the bicycle was constituted as a symbol of a green lifestyle in environmentalist discourse in the 1970s, today e-micromobility appears as a ‘green machine’ i.e. a materialization of ecological goals, as opposed to the dominant car regime (Horton Citation2006). Supporting the emergence of these modes suggests ‘the way forward’ to address social and environmental problems, mostly due to automobility (Horton Citation2006, 41). Articles often refer to issues in the mobility system, especially regarding the commute: ‘commuting problems’ (UK-TG-3-20), ‘saviour of the commute’ (UK-TG-9-20), ‘rented e-scooters ride to the rescue of English commuters’ (UK-TG-4-20), ‘commuter chaos’ (UK-TT-3-20).

The frame of micromobility as an instrument to change the mobility regime is especially prevalent in British articles from 2020 (see dataset for frame coverage per year), in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic because it significantly shifted transport practices and policies. Articles highlight how micromobility allowed commuters to avoid public transit during lockdowns (UK-TG-2-20; 3-20; 4-20; 6-20; 11-22; UK-TT-3-20), facilitating social distancing and relieving pressure on overloaded public transit networks. Yet, one article acknowledged the complexity of such change, stating ‘electric scooters are not going to solve all the problems, but they can help’ (UK-TT-3-20).

Our analysis demonstrates that government and industry actors instrumentalize micromobility as a driver of ecologically sustainable change. Micromobility appears in the press as a central component of the 2019 national government’s strategy for the ‘future’ of mobility, making ‘low carbon transport cheaper, safer and more reliable’ (UK-TT-2-19). This strategy rests on ‘emerging technologies’ (UK-TG-1-20) like e-scooters and other electric vehicles. Further, the analyzed articles show how industry actors foreground environmental concerns to boost sales. Advocating for a ‘green economic recovery’ (UK-TG-5-20) post-pandemic, micromobility and energy industry actors argue for a shift to electric energy. The electrification of scooters, bikes, and cars would contribute to this ‘revolution’ (UK-TG-5-20). Furthermore, shared micromobility operators use this frame to legitimize their rapid expansion.

The Sustainable and Active frame prevails in the British press, contrasting with the Dutch case where it is invoked primarily concerning cargo bikes as alternatives to cars. One article suggests cargo bikes compete with cars because they are similar in terms of size and use (NL-DV-4-20), projecting the ambiguous status of cargo bikes as mini cars rather than as large bicycles because they can transport heavier loads (Cox and Rzewnicki Citation2015). In the British case, cargo bikes are discussed as sustainable alternatives to business vans (UK-TG-10-22).

Micromobility as an active alternative to automobility

The Sustainable and Active frame presents micromobility as an active alternative to automobility. While scholarship usually limits active travel to walking and cycling (Cook et al. Citation2022), the analyzed newspaper articles expand the term’s scope to include motorized modes like e-bikes and e-scooters. British articles especially reference health benefits as motivators to use micromobility. This justification often involves scientific evidence on the—sometimes contested—health benefits of motorized modes (UK-TG-3-20). In contrast to the Sustainability aspect of this frame, articles focusing on the Active aspect lend users more ‘voice’ through indirect and direct quotes.

The articles frame e-micromobility as more inclusive than other active modes like cycling, highlighting how e-bikes allow those unable to bicycle to exercise (UK-TG-2-20; 3-20; 6-20). In the case of e-scooters, one user is quoted: ‘Anyone can ride a scooter – it’s more democratic than a bicycle’ (UK-TG-9-20). In other words, scooters rather than bicycles are discussed as a mode accessible to more people. Micromobility is also lauded for its mental health benefits in both cases, allowing users to connect with their environment (NL-DV-5-21; 12-22; 13-22; UK-TG-2-20). Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the newspapers introduced a new (or temporary) justification, suggesting micromobility could tackle people’s social contact and outdoor needs without the threat of spreading the virus.

The Active frame differs in the UK and the Netherlands–especially regarding e-bikes and users’ age. Originally popular among the elderly, the Dutch press reports on how teenagers use e-bikes for their school commute (NL-DV-7-22; 8-22; 9-22; 10-22; 13-22). Most acknowledge the practical aspects of e-bikes for commuting trips (NL-DV-8-22; 13-22), but they also question e-bikes’ presumed health benefits for younger people (NL-DV-7-22; 12-22; 14-22; 15-22). While in the Dutch case, young users are framed negatively, describing them as ‘brats’ (NL-DV-10-22) and ‘lazy children with rich parents’ (NL-DV-8-22) and e-bikes as a transport mode for lazy people (NL-DV-8-22; 9-22; 12-22), in the UK case, by contrast, e-bikes are praised for their health benefits.

The Active aspect of this frame presents micromobility, especially electric modes, as fun and convenient. British articles suggest that this aspect makes e-micromobility more attractive than other non-electrified modes like cycling (UK-TG-9-20; 11-22). Still, some non-users consider micromobility modes like e-scooters gadgets for tech-savvy individuals instead of serious commuter modes (UK-TG-7-20). In the Dutch case, e-biking appears as a social activity among teenagers riding side-by-side to school, while those using human-powered bicycles are excluded because they no longer ride at the same speed as their peers (NL-DV-13-22).

In short, the British press presents micromobility as a way to shift the car-dominated mobility regime towards sustainable and active mobilities, with electrification plays an important role. These recall the e-mobility discourse as a panacea for sustainable transport revolving around e-automobility (Behrendt Citation2018). This frame focuses on technological innovation as the key to stepping away from automobility, but it ignores other social, political, cultural, and spatial aspects sustaining the car system. Conversely, in the Netherlands, where cycling has already a major modal share in the mobility regime, this frame is more nuanced.

The Disruption frame

While the previous Sustainable and Active frame portrays micromobility as a remedy in the (mostly) British mobility system, the Disruption frame shows micromobility as a problem for the Dutch mobility system (Entman Citation1993). This frame unfolds in two ways. The electric-powered micromobilities that replace human-powered cycling are neither considered a sustainable nor an active alternative to the Dutch automobility. The articles, moreover, stress that micromobilities disrupt the country’s strong cycling culture and identity. This frame highlights the cultural and social aspects of mobility, providing an insight into user perspectives. Bicycle users, governmental actors, and organizations like the Dutch Cyclists’ Union actively support this frame through direct quotes or as authors in opinion pieces.

Micromobility as a sustainable substitute

A Disruption frame’s key aspect is that some micromobilities, especially electric modes, are not considered sustainable alternatives in the Dutch mobility regime. While some articles discuss micromobility’s potential for active and sustainable change like in the first frame, they usually question whether micromobility could replace car use (NL-DT-5-21; NL-DV-7-22; 8-22; 9-22; 12-22). As NL-DV-10-22 puts it: ‘By no means do all e-bikers leave their car behind to relieve the burden of commuting or to increase their range by bike. They replace the regular bicycle for short trips’. In other words, e-micromobilities may replace cycling and walking rather than car use, failing to fulfill its promises as featured in the Sustainable and Active frame.

The analyzed articles point out that some e-micromobilities like e-mopeds and e-scooters may not effectively reduce CO2 emissions, despite their ‘image of being sustainable’ (NL-DT-5-21; NL-DV-6-22). This draws on scientific evidence, notably a Dutch report on LEVs (Knoope and Kansen Citation2021). Criticism extends to e-bikes, seen as business-driven ‘hype’ (NL-DV-5-21) and ‘smart marketing’ (NL-DV-7-22), pointing at the agency of the bicycle industry. In addition, articles refer to the problem of emissions related to production, recycling, or shared modes redistribution. Overall, this criticism concerns mainly electric and/or shared modes, resonating with academic debates on e-micromobility’s role in decarbonizing transport (Şengül and Mostofi Citation2021). This criticism evolved over time. In 2019, e-mopeds were ‘good news for air quality’ according to automobile lobby organizations in NL-DV-3-19 while this sustainability narrative is mostly deconstructed in more recent articles e.g. NL-DT-5-21, NL-DV-6-22; 7-22.

In short, Dutch articles question environmental promises as an incentive to use micromobility. This concurs well with the environmentalism and cycling scholarship that finds that in mature cycling countries like the Netherlands, people who cycle do not necessarily identify with environmental causes (Horton Citation2006). In contrast, in the UK, environmental goals locally and globally seemed to motivate cycling (Aldred Citation2010).

Micromobility as a disruption of Dutch cycling culture

Another key aspect of this frame, specific to the Dutch press, is that the new micromobilities disrupt cycling culture. One article expresses the concern that cycling will disappear over time: ‘The joy of ordinary cycling will become something like the art of bobbin lace, or (in the longer term) reading a paper newspaper, a craft skill that only a few older people still master’ (NL-DV-5-21). E-micromobility is framed as ‘modern life’, compared to ‘old-fashioned’ micromobility practices like cycling (NL-DV-14-22).

Analyzed articles frame the perceived decline of cycling due to the success of e-micromobility as a disturbance of Dutch national identity. Our analysis demonstrates that human-powered cycling is considered a pillar of Dutch identity: ‘The people who built the country used to just pedal seventeen kilometers each day there and back to school with headwinds’ (NL-DV-10-22). NL-DV-11-22 also mentions the association of Dutch identity with cycling: ‘On the bike, I felt like a perfectly normal Dutchman, like Prime Minister Rutte who openly cycles to the Torentje.Footnote1 The moped does not look as good’. It is also reflected by the Dutch terminology to designate a bike: gewone (‘simple’) or normale fiets (‘normal bike’). The normalcy of Dutch cycling is discussed by Te Brömmelstroet, Boterman, and Kuipers (Citation2020, 110-111) as a ‘culturally- and socially-shaped second nature’; with the appearance of new types of bicycles becoming increasingly a means to show one’s identity. Our analysis expands this argument to new micromobility types e.g. speed pedelecs, e-mopeds, and more recently fatbikes since their emergence altered Dutch habitual cycling (Kuipers Citation2013).

The electrification of cycling is important in this frame. The Dutch articles question whether e-bikes should be considered bicycles because they barely require pedaling (NL-DT-6-21) but also because accidents are more severe (NL-DV-8-22). Skills needed to maneuver e-bikes are different than those of so-called normal cycling (NL-DV-8-22). Articles highlight that the electrification of bicycles and induced speed differences lead to safety issues on the cycle path. Discourse on human-powered cycling focuses on individuals, depicted as vulnerable road users, pedaling ‘in a relaxed way’ (NL-DV-15-22). On the contrary, discourse on e-cycling focuses on monstrous worked-up vehicles: ‘bigger motorized beasts’ or ‘strongest lions fighting for supremacy’ (NL-DV-15-22). E-bikes are also oftentimes associated with automobility (NL-DV-14-22; 15-22).

In short, the Dutch press frames the emergence of micromobility as disturbing the Dutch cycling regime and interrupting deeply engrained socio-cultural patterns of the Dutch mobility system. These two frames thus suggest that local mobility contexts matter in the framing of micromobility. The Disruption frame also touches on the impact of the emergence of new micromobility modes on public space.

Framing micromobility’s impact on public space

This section focuses on how micromobility’s impact on public space is framed. Specifically, we identified two frames used in both Dutch and British articles: the Conflict frame and the Regulation frame.

The Conflict frame

The Conflict frame in the Dutch and British press describes conflicts between micromobility and individual and non-automotive modes in public space. Covered equally by all newspapers in both cases, this frame addresses the spaces and users involved in these conflicts i.e. the sidewalk and pedestrians in the UK and the cycle path and cyclists in the Netherlands. Articles discuss how micromobility collides with already marginalized modes in contested spaces and raises safety concerns. The Conflict frame is particularly pertinent in the 2020–2021 British press, around the introduction of e-scooter trials. While this frame appears to fulfill a ‘problem definition’ function regarding conflicts in public space, it also presents a ‘causal interpretation’ of the issue by highlighting micromobility’s lack of safety (Entman Citation1993). This Conflict frame of micromobility relates to its spatial as well its legal aspects: it draws attention to the allocation of space among uses, without challenging the domination of automobility in public space.

In both countries, micromobility is negatively framed, using the terminology of conflict and death. Arguments are rarely nuanced, for example, micromobility use is described as ‘antisocial’ (NL-DV-11-22; UK-TG-7-20). Actors supporting this frame are non-users and organizations like the Royal National Institute of Blind People, traffic safety organizations, and government actors. The Conflict frame follows from the Disruption frame of the Dutch cycling regime, and it contrasts with the Sustainable and Active frame in the British regime. Notably, actors involved in the British press are different from the Sustainable and Active frame, often opposing micromobility.

Micromobility conflicts with pedestrians (UK) and cyclists (NL)

The Conflict frame depicts clashes between micromobility users and other subaltern users who have been allocated relatively limited public space. In the British press, this frame emphasizes contestations between pedestrians and e-scooter users on the sidewalk, despite regulations mandating shared space with cars. The press argues that e-scooter users tend to ride on the sidewalk, ‘mak[ing] the pavements intolerable for pedestrians’ (UK-TT-7-21). This highlights how pedestrians are already marginalized in public space: ‘For pedestrians it makes no difference whether cars, bicycles or e-scooters are the enemy: on the pavements it remains sauve qui peutFootnote2 as usual’. (UK-TT-7-21). The encounter of e-scooters with other modes should according to traffic laws take place on the road, but occur on the sidewalk. This affirms the domination of automobility in space allocation (also referred to in UK-TG-11-22), rendering the sidewalk as ‘a residual category that collects all non-car mobility modes and uses’ (Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong Citation2020, 21).

In the Dutch press, by comparison, this frame stresses conflicts involving e-micromobilities and cyclists on the cycle path. Articles often argue that the overcrowded cycling infrastructure reached its maximum capacity (NL-DT-4-21; NL-DV-1-19; 8-22; 9-22). In contrast with its British counterpart, this frame is endorsed by organizations like Safety Traffic Netherlands and the Dutch Cyclists’ Union. Non-users, referenced through direct quotes, also support this frame but to a lesser extent. They focus on cycle paths’ residual aspect:

The cycle path threatens to become the drain of the traffic system. Now that light electric vehicles (LEVs) like cargo bikes and scooters may soon be allowed to use them, there will be even greater chaos on the already overcrowded cycle paths. (NL-DT-4-21)

Overall, micromobility modes are framed as conflicting with modes they share space with, whether it is legally on cycle paths in the Netherlands, or illegally on sidewalks in the UK. Our findings suggest that, in both countries, these conflicts do not challenge automobility’s dominance in public space.

Safety concerns

Safety concerns are central to this Conflict frame, attributing inherent risks to micromobility vehicles. Speed is one of them: because of their ‘hectic speeds’ (UK-TT-4-20), e-scooters are deemed more dangerous than others like bicycles (UK-TG-11-22). Similarly, the Dutch press highlights speed differences between cycle path users, leading to ‘chaos’ (NL-DT-1-19; 6-21). E-scooters’ instability is also seen as contributing to safety issues. Lastly, the sonic experience of mobility is altered. E-scooters are described as ‘mostly silent’ (UK-TG-11-22), ‘silently speeding’ (UK-TT-5-20), ‘glid[ing] along our streets’ (UK-TT-2-19), or ‘whizzing around’ (UK-TG-9-20) and therefore dangerous.

Following from this, in the British press, e-scooters are framed as dangerous, particularly for people with disabilities and the visually impaired (UK-TG-9-20; 11-22; UK-TT-4-20): they cannot use public space safely because of parked or moving micromobilities. Such framing suggests a concern about mobility justice because some micromobilities may impede people’s access to public space (Prytherch, Citation2018). This frame uses value-laden expressions like ‘lethal form of transport’ (UK-TT-8-21), ‘death traps’ and ‘silent killing machines’ (UK-TT-6-21), ‘enemy’ (UK-TT-7-21), ‘menace’ (UK-TT-5-20), ‘threat’ (UK-TT-4-20).

A few articles place the safety debate in the broader frame of automobility (UK-TG-11-22; UK-TT-2-19). As UK-TG-2-20 puts it: ‘Cycling is an inherently safe form of transport where the danger is almost all external – that is, from drivers and other motor vehicle users’. UK-TT-4-20 explains that e-scooter users ride on the pavement because they are afraid to use them on the road.

Another critical aspect of the Conflict frame in the UK is how in the press e-scooter users are discussed by non-users and governmental actors like the police and policymakers. Users are portrayed as careless riders, driving under the influence, without a license, or even speeding away from the police (UK-TG-7-20; 11-22; UK-TT-5-20; 6-21). They ‘misuse’ vehicles (UK-TG-7-20) and show ‘malpractice or bad user behaviour’ (UK-TT-5-20). Articles report that reckless behavior damages the image of the scooter industry actors and users. Given the limited and only recent legality of e-scooters in the UK, e-scooter users are also framed as resisting traffic rules: ‘There are hundreds of thousands of these lawbreakers in the country today (…) they’re the e-scooter riders of the UK, and they have already come to a street near youf’ (UK-TG-11-22). The framing of e-scooter users echoes the framing of cyclists as inherently dangerous in scholarship (Fevyer and Aldred Citation2022; Rissel et al. Citation2010; Bonham and Cox Citation2010; Oldenziel and Albert de la Bruhèze Citation2011). Users are designated through impersonal expressions and pronouns e.g. ‘e-scooter rider’ or ‘one of them’ (UK-TG-9-20). Overall, described e-scooter users are disliked, ‘in the same way that some people don’t like cyclists (…) they are perceived to be ‘other’ or doing something that is not normal’ (UK-TG-11-22).

In sum, in both the Dutch and British press, micromobilities are negatively framed as competing with other subaltern modes in public space. This frame rarely questions the predominately car-oriented allocation of space. Yet, the framing of conflicts varies across cases. In the Netherlands, micromobilities are framed as generating conflicts due to insufficient cycling infrastructure capacity. In the UK, the illegal use of some modes like e-scooters is central.

The Regulation frame

The Regulation frame concerns who is to blame for these problems and potential solutions. This frame was identified in Dutch and British articles, especially in the ideologically conservative Telegraph and Telegraaf. The shortcomings of existing micromobility regulations are presented as a causal interpretation of the abovementioned public space conflicts (Entman Citation1993), while this frame suggests that regulations need to change to create the safe use of micromobility, hence as a treatment recommendation. Despite the identification of possible solutions to regulation inadequacies, most analyzed articles fail to challenge existing regulations centered around facilitating the uninterrupted speed of cars, called ‘flow’. Yet, some hint at radical approaches to space allocation, questioning the domination of automobility. In both cases, the frame mobilizes many actors whether presented as micromobility proponents or opponents. This frame builds on the legal and policy aspects of mobility.

Inadequacies of micromobility regulations

The downsides of micromobility regulations are central in the Regulation frame. Analyzed articles assert unclear regulations using terms like ‘proliferation’ (NL-DT-1-19; 4-20), ‘mess’ (UK-TG-11-22), ‘makes no sense’ (UK-TG-9-20), or ‘chaos’ (NL-DV-1-19). Articles mention that clear regulations would address the abovementioned public space and safety issues (NL-DT-3-20; NL-DV-1-19; UK-TG-9-20; UK-TT-8-21). Consequently, the government is cast as responsible for these issues (NL-DT-5-21; NL-DV-1-19; UK-TT-2-19; 8-21). This coincides with the call for enforcing existing rules (NL-DT-6-21; UK-TT-7-21). The frame questions regulatory coherence and highlights how easy it is to buy e-scooters in both countries (NL-DT-1-19; NL-DV-1-19; UK-TG-9-20; 11-22) although they are illegal in public space but legal in private property (UK-TG-9-20; UK-TT-5-20). An important aspect of this frame is that micromobility’s sudden popularity demands rapid policy reaction (NL-DT-1-19; UK-TT-2-19). Especially with the advent of e-scooters in 2020, British media argues that ‘legislation needs to urgently catch up’ (UK-TT-5-20), stressing the discrepancy between policymaking and practice.

Our analysis demonstrates how the perceived ambiguity of some micromobility modes partly results from the unclarity of regulations. Pondering where e-scooters belong, we find in the British press (in UK-TT-5-20) the notion of the ‘pavement dilemma’. The ambiguity of some modes echoes previous research. According to Dekker (Citation2021) and Tuncer et al. (Citation2020), new modes tend to have an ambiguous status because they do not yet belong to a set category of vehicles, usually characterized as the automobility-velomobility dichotomy. Consequently, users, who are unfamiliar with these modes, tend to use pedestrian space to avoid the rules that apply to them (Tuncer et al. Citation2020). This ambiguity may lead to conflicts, as discussed above.

The analyzed articles tend to emphasize the politics of micromobility regulations. Some British articles condemn the government’s decision to legalize e-scooter trials to some degree. UK-TT-7-21 blames the government for making ‘perverse’ unilateral decisions on e-scooters for the sake of ‘green, sustainable recovery from coronavirus’. Proponents of the Regulation frame position themselves as defenders of pedestrians, whom they present as unheard voices in the political process. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Safety Board quoted in one article stresses the political agency behind LEV regulation, ‘born of the political desire to get new vehicles on the road as quickly as possible’ (NL-DV-2-19). This discussion emerged in 2019 during the legal case of the Ministry against the Stint manufacturer in the wake of the 2018 accident. Drafted rapidly in 2010 to accommodate the Segway on the roads, the Dutch special moped category does not accommodate all vehicle types very well. In response, the Dutch Safety Board proposes to shift the authority from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management to an independent body ‘which takes the decisions without political interference’ (NL-DV-2-19). Overall, our findings underscore the intertwining of regulations and politics in the discourse surrounding micromobility.

Recommendations for enabling safe micromobility

In both cases, the Regulation frame also includes suggestions on how to ensure micromobility’s safe use. This aspect formulates ‘treatment recommendation[s]’ (Entman Citation1993, 52) like enforcing regulations better (UK-TG-8-20) and stricter regulations on shared modes in public space (NL-DT-3-20). From this perspective, responsibility lies with both the government and users, with an emphasis on disciplining user behavior through rule enforcement. These approaches address issues through incremental changes, thus maintaining the status quo based on car domination.

Dutch traffic organizations propose another type of recommendation such as providing e-bike training for children (NL-DV-8-22), implementing new speed limits, and redefining space allocation to protect vulnerable groups (NL-DT-4-21; 6-21). In Amsterdam, the Dutch Cyclists’ Union suggests e-bikes should ride on the road with cars like mopeds, implying it considers e-bikes’ speed closer to mopeds, or even cars, than bikes. In the British press, cycling and micromobility advocates call for better cycling infrastructure to ensure the safe use of micromobility (UK-TG-3-20; UK-TT-5-20; 9-20). These actors thus prescribe more radical approaches, somehow challenging the ubiquity of automobility in space.

In short, the Regulation frame highlights the need for regulatory changes to solve micromobility conflicts in public space and safety issues. It would include clarifying the status of some micromobility modes. Yet, our analysis shows that such change is much more complex and depends on the broader political context. Furthermore, suggesting that rules should be enforced better implies maintaining the car-dominated status quo while protecting pedestrians from reckless driving. At the same time, other articles suggest re-thinking car-oriented space allocation, including legal and spatial aspects, hence hinting at radical change in policies and regulations aiming at transforming the dominant car regime. Equally important are the cultural perceptions of micromobility that are the focus of the next frame.

Framing social and cultural perceptions of micromobility

This section lays out the result of our analysis around the topic of social and cultural perceptions of micromobility. Here, we identified the Lifestyle frame as main frame.

The Lifestyle frame

The Lifestyle frame evokes the cultural perceptions of micromobility modes and their users, mostly in the Dutch press, including changes over time. Our analysis demonstrates that micromobilities may be a way for users to flaunt their social status, intersecting with their demographic characteristics like gender, class, age, or ethnicity. Whereas the previous frames discussed problems, causes, and remedies related to micromobility, the Lifestyle frame entails a moral evaluation (Entman Citation1993). The Lifestyle frame predominantly features in recent articles from ideologically progressive newspapers, frequently emphasized through direct and indirect quotes from non-users who are critically commenting on the micromobility phenomenon.

Micromobility as a lifestyle choice

The Lifestyle frame foregrounds how certain micromobilities affirm users’ social status. The Dutch press routinely mentions the relatively high cost of the new micromobilities especially compared to the one of an ordinary bicycle (NL-DV-4-20; 8-22; 13-22; 14-22). One satirical article depicts different e-bike users and their attributes (NL-DV-14-22):

The rider of the VanMoof (usually equipped with AirPods Pro, loose-fitting vintage denim jacket, and Birkenstock Bostons – or a high-necked raincoat and gel hairs) can be on the doorstep of the Rocycle studioFootnote3 in no time (without seeing the irony in that), quickly home after class to take a shower and then quickly to that one liquor store that sells natural wine, to then join the vegan brunch without any trace of effort on the face, nor a drop of sweat under the armpits. Any noises too.

Similarly, (female) gender and (white) ethnicity intersect with (middle) class. A striking example is how gender at the intersection of the two, more specifically white middle-class motherhood, shapes the cultural perceptions of the cargo bike user. As NL-DV-11-22 points out:

The cargo bike mother. A cheerful, part-time working woman who takes her children from pillar to post sustainably and drinks fresh mint tea during her break. Cargo bike mothers park directly in front of the entrance so that no one can pass (…) they are also a sign of the gentrification of certain neighborhoods in the city.

A blond woman on a cargo bike or a white man on an e-bike, if they lose their keys and then try to break their lock, are not thieves, but needy citizens. As a darker-skinned man, I am extremely suspect in such a context, a criminal.

Our results suggest that these class, gender, and ethnic identities are entangled with speed and public space collisions, resulting in the cycle path’s social stratification. As critically explained by NL-DV-15-22: ‘Social Darwinism has moved to the cycle path’, where e-micromobility users, who belong to ‘a successful professional caste’ rule. Articles discuss power relations resulting from the combination of high speed and social status. As quoted from NL-DV-14-22: ‘The wealth gap manifests itself in the different speeds at which we can send our children to school’. This finding concurs with the politics of speed, first introduced by Norton (Citation2008), and later discussed by Cresswell (Citation2010, 22) on the role of speed ‘in the constitution of mobile hierarchies and the politics of mobility’, especially in relation to automobility. This suggests that these micromobility-related identities may play a role in public space contests discussed in the Conflict frame.

In both cases, some micromobility users are framed as the Other. This means that these users have a different identity than those from the dominant group. In the British case, UK-TG-11-22 explains that the e-scooter user is the Other, while the norm is the car driver. Evidence of othering around ‘mamils’ was not found. In the Dutch case, where mopeds and bicycles share the cycling path, the ethnic moped rider is described as the Other, while the ‘hard-working citizen’ i.e. a cyclist is the norm (NL-DV-11-22). This finding illustrates the difference between the Dutch regime, in which cycling is the norm operating within a car regime, and the British regime, largely car-dominated.

Changing meanings of micromobility

The Lifestyle frame also shows micromobility’s changing meanings over time—particularly in the Dutch case. For one, cargo bikes have not always been a symbol of the well-off. Like mopeds, cargo bikes were first associated with left-wing policies and anarchist movements (Te Brömmelstroet, Boterman, and Kuipers Citation2020). Working-class men rode mopeds in the 1950s before they became associated with youth culture in the 1960s (Dekker Citation2021). Today, mopeds are framed in terms of ecological sustainability as ‘fine dust cannons’ (NL-DV-3-19), while shared e-mopeds have acquired a sustainable and trendy image – even while being increasingly contested (NL-DV-6-22). Lastly, articles mention the changing image of microcars (NL-DT-2-20; NL-DV-13-22) that used to be driven by people with disabilities but recently have been discovered by ‘trendy Amsterdam-South girls and boys’ (NL-DT-2-20) in the context of the changing helmet regulations. New practices have led to new identities associated with status and lifestyles. This is reflected in the scholarship on the changing meanings of micromobility in the Dutch context of cycling as the nation’s identity and norm. Cycling became ‘a means of showing your identity and your social status’ (Te Brömmelstroet, Boterman, and Kuipers Citation2020, 112; Kuipers Citation2013). Our findings expand this claim to other micromobility modes in this specific context.

In brief, micromobilities’ cultural meanings change over time and are influenced by the groups that use them and their social status. These frames present micromobility as a way to reproduce class, gender, and ethnic relations either within micromobility modes in the Dutch case or in relation to automobility. We also find that qualities traditionally associated with automobiles, like speed or status are associated with micromobility. This frame of micromobility thus echoes the ‘specific character of domination’ of automobility (Urry Citation2004, 25) and seems to perpetuate rather than challenge automobility.

Conclusion

The media’s agenda-setting function in terms of selecting and presenting issues to the public and policymakers is crucial for the urgently needed transition towards more sustainable mobilities, including how the media frames micromobility. It is clear that extending automobility into the future, via the current research and policy focus on e-cars, cannot be the only solution (Brand et al. Citation2020). While micromobilities are not the sole solution either, they can play a more significant role in decarbonizing transport than currently reflected in policy and research (Şengül and Mostofi Citation2021). How is micromobility’s potential to shift away from automobility reflected in our discourse analysis of the Dutch and British national press?

Overall, our analysis shows that the frames identified in the print media only limitedly address micromobility’s potential to transition from a car-based to a more sustainable society. Progressive newspapers tend to be more critical of automobility, influenced by their political leanings (Linström and Marais Citation2012). Articles mainly focus on micromobility in relation to ‘non-automobile’ elements of society like conflicts between different forms of micromobility in public spaces, social status, and regulatory challenges. Following Petzer, Wieczorek, and Verbong (Citation2020)’s work on shared bikes in Amsterdam, we argue that micromobility and subaltern regimes compete for scarce resources like public space and policy priorities while being pressured and dominated by the automobility regime. In sum, framings of micromobility as competing with cyclists and pedestrians confirm the ‘assumed primacy and normativity of ‘motor traffic flow’ over other considerations in transport planning’ (Fevyer and Aldred Citation2022, 775).

Our results underscore the significance of local mobility regimes in representing micromobility and its potential to mitigate automobility. In the Netherlands, micromobility is framed as replacing pedal-powered cycling as the existing sustainable and active alternative to automobility. In the UK, where cycling is marginal, micromobility is framed as an opportunity to develop and diversify cycling practices especially with electrification, fostering a sustainable and active shift from automobility. Yet, this study highlights the complexity of mode substitution narratives which tend to overlook cultural, political, social, and spatial aspects sustaining the car system.

Specifically, our findings show how these discussions happen through five frames, grouped under three topics.

The topic ‘Impact on Mobility Systems’ contains the ‘Sustainable and Active frame’, prominent in the British press, promoting micromobility – especially electric micromobility – as a sustainable and active alternative to car use. Secondly, the ‘Disruption frame’, prevalent in the Dutch press, views micromobility as potentially threatening the well-established Dutch cycling culture.

Within the topic ‘Impact on Public Space’, the ‘Conflict frame’, found in the UK and the Netherlands, discusses contestations between micromobility users and others in public space. In addition, in both cases, the ‘Regulation frame’ presents micromobility regulations as potential solutions to public space conflicts, with proponents urging radical changes to space allocation logic, while opponents suggest strengthening existing rules.

The topic ‘Social and Cultural Perceptions’, and the centrally associated ‘Lifestyle frame’ mainly found in the Dutch press, examines cultural perceptions of micromobility, portraying new e-micromobilities as ways for users to flaunt their social status within the country’s norm of pedal-powered cycling.

Our study contributes to mobilities research about the representation of (micro)mobility by providing a nuanced understanding of micromobility’s potential to alleviate the dominance of automobility, through the study of media framing. Unlike previous scholarship that focused on single modes and countries, we adopt a multi-modal and comparative perspective on micromobility. We also broaden the scope of mobilities research by considering modes like mopeds and call for considering micromobilities in their relationship to the macromobility of automobility. Finally, we emphasize the significance of lifestyles and social status in mobility transitions, challenging the dominant discourse centered on CO2 emissions and mode shift.

Our study has some limitations. While newspaper articles offer valuable insights into framing, some voices may be systematically underrepresented based on their gender, age, or race. We attempted to capture whose voices were marginalized or absent in our coding structure, but future work could explore their discourses on micromobility, for instance by analyzing social media framing (López-Rabadán Citation2021).

Our findings have several policy implications. First, media framings often overlook the questioning of automobility and its supporting elements like policies and infrastructure. We hope that this paper shows the urgency to put the transition from automobility—the elephant in the room—on the agenda. Second, our study highlights the challenge of allocating limited and contested public space among subaltern modes, including micromobility. To unlock micromobility’s potential in challenging automobility, policymakers should rethink how public space is allocated to different uses in the first place. We argue that challenging automobility requires regulatory changes that disrupt the status quo instead of reinforcing it through stronger regulations for instance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ruth Oldenziel, Hanbit Chang, Eriketti Servou, and Leon Vauterin for their feedback that contributed to improving the quality of this paper. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

The dataset associated with this article is available at: https://doi.org/10.4121/6e729fe8-32c9-4c0c-a86f-6e95074568f8

Notes

1 The official office of the Dutch Prime Minister.

2 ‘Run for your life’, in French.

3 Spinning studio in the Netherlands.

References

- Abduljabbar, Rusul L., Sohani Liyanage, and Hussein Dia. 2021. “The Role of Micro-Mobility in Shaping Sustainable Cities: A Systematic Literature Review.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 92 (March): 102734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.102734.

- ACEM 2017. “Motorcycle, Moped and Quadricycle Registrations European Union. 2010-2017.”

- Aldred, Rachel. 2010. “On the Outside’: Constructing Cycling Citizenship.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (1): 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903414593.

- Bakker, Piet, and Peter Vasterman. 2008. “The Dutch Media Landscape.” In European Media Governance: National and Regional Dimensions, 145–157.

- Behrendt, Frauke, Eva Heinen, Christian Brand, Sally Cairns, Jillian Anable, Labib Azzouz, and Clara Glachant. 2023. “Conceptualising Micromobility.” Preprint. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202209.0386.v1.

- Behrendt, Frauke. 2018. “Why Cycling Matters for Electric Mobility: Towards Diverse, Active and Sustainable e-Mobilities.” Mobilities 13 (1): 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1335463.

- Bennett, Cynthia, Emily Ackerman, Bonnie Fan, Jeffrey Bigham, Patrick Carrington, and Sarah Fox. 2021. “Accessibility and the Crowded Sidewalk: Micromobility’s Impact on Public Space.” DIS 2021 – Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference: Nowhere and Everywhere, June, 365–80. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461778.3462065.

- Bicycle Association 2021. “Building On The Boom: The UK Cycling Market in 2020 and Beyond.”

- Bonham, Jennifer, and Peter Cox. 2010. “The Disruptive Traveller? A Foucauldian Analysis of Cycleways.” Road & Transport Research 19 (2): 42–53.

- Boterman, Willem R. 2018. “Carrying Class and Gender: Cargo Bikes as Symbolic Markers of Egalitarian Gender Roles of Urban Middle Classes in Dutch Inner Cities.” Social & Cultural Geography 21 (2): 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1489975.

- BOVAG. 2022. “Mobiliteit in Cijfers.” www.bovagrai.info.

- Brand, Christian, Jillian Anable, Ioanna Ketsopoulou, and Jim Watson. 2020. “Road to Zero or Road to Nowhere? Disrupting Transport and Energy in a Zero Carbon World.” Energy Policy 139 (April): 111334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111334.

- Brömmelstroet, MarcoTe, Willem Boterman, and Giselinde Kuipers. 2020. “How Culture Shapes – And Is Shaped by – Mobility: Cycling Transitions in The Netherlands.” In Handbook of Sustainable Transport, 109–118. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Cairns, Sally, Frauke Behrendt, David Raffo, and Clare Harmer. 2015. “Electrically-Assisted Bikes: Understanding the Health Potential.” Journal of Transport & Health 2 (2): S17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.04.512.

- Connolly-Ahern, Colleen, and S. Camille Broadway. 2008. “To Booze or Not to Booze?’: Newspaper Coverage of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.” Science Communication 29 (3): 362–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547007313031.

- Cook, Simon, Lorna Stevenson, Rachel Aldred, Matt Kendall, and Tom Cohen. 2022. “More than Walking and Cycling: What Is ‘Active Travel’?” Transport Policy 126 (September): 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.07.015.

- Cox, Peter, , and Randy Rzewnicki. 2015. “Cargo Bikes: Distributing Consumer Goods.” In Cycling Cultures, 130–151. Chester: University of Chester Press. http://hdl.handle.net/10034/554288.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2010. Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 17–31.

- Crow, Deserai A., and Andrea Lawlor. 2016. “Media in the Policy Process: Using Framing and Narratives to Understand Policy Influences.” Review of Policy Research 33 (5): 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12187.

- Cycling UK. 2022. “Cycling Statistics.” www.cyclinguk.org.

- Dekker, Henk-Jan. 2021. “An Accident of History? How Mopeds Boosted Dutch Cycling Infrastructure (1950–1970).” The Journal of Transport History 42 (3): 420–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/00225266211011935.

- Department for Transport 2020. “Gear Change: A Bold Vision for Cycling and Walking.”

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Fevyer, David, and Rachel Aldred. 2022. “Rogue Drivers, Typical Cyclists, and Tragic Pedestrians: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Media Reporting of Fatal Road Traffic Collisions.” Mobilities 17 (6): 759–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1981117.

- Firmstone, Julie. 2018. “The Media Landscape in the United Kingdom, Media Landscapes: Expert Analyses of the State of the Media.” https://medialandscapes.org/country/united-kingdom.

- Fitt, Helen, and Angela Curl. 2020. “The Early Days of Shared Micromobility: A Social Practices Approach.” Journal of Transport Geography 86 (June): 102779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102779.

- Gamson, William A., and Andre Modigliani. 1989. “Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach.” American Journal of Sociology 95 (1): 1–37. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213.

- Giesen, Peter. 2022. “Terwijl de Automobilist in de Stad Wordt Getemd, Heeft Het Sociaal-Darwinisme Zich Naar Het Fietspad Verplaatst.” De Volkskrant, August 2, 2022.

- Gössling, Stefan. 2020. “Integrating E-Scooters in Urban Transportation: Problems, Policies, and the Prospect of System Change.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 79 (February): 102230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102230.

- Haas, MathijsDe, Marije Hamersma, and Anp-Hollandse Hoogte. 2020. “Cycling Facts: New Insights.” The Hague.

- Harms, Lucas, Luca Bertolini, and Marco Te Brömmelstroet. 2014. “Spatial and Social Variations in Cycling Patterns in a Mature Cycling Country Exploring Differences and Trends.” Journal of Transport & Health 1 (4): 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.012.

- Horton, Dave. 2006. “Environmentalism and the Bicycle.” Environmental Politics 15 (1): 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010500418712.

- Invers 2022. “Global Moped Sharing Market Report 2022.” https://go.invers.com/hubfs/Downloads/INVERS%20Global%20Moped%20Sharing%20Market%20Report%202022.pdf?utm_campaign=INVERS%20GC&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=233017645&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-8LDT0LleYdERSUnYFGoewNpCVD2y08Q0TTtFjQm8ZwYwXWaWsvnwLYdZhGYgNtyjg-JaluRAb2jRQu_aIcmU-4xVzHGQ&utm_content=233017263&utm_source=hs_automation.

- ITF. 2020. “Safe Micromobility.”

- Knoope, Marlinde, and Maarten Kansen. 2021. “De Rol van Lichte Elektrische Voertuigen in Het Mobiliteitssysteem.” The Hague.

- Kuipers, Giselinde. 2013. “The Rise and Decline of National Habitus: Dutch Cycling Culture and the Shaping of National Similarity.” European Journal of Social Theory 16 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431012437482.

- Latinopoulos, Charilaos, Agathe Patrier, and Aruna Sivakumar. 2021. “Planning for E-Scooter Use in Metropolitan Cities: A Case Study for Paris.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 100 (November): 103037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.103037.

- Linström, Margaret, and Willemien Marais. 2012. “Qualitative News Frame Analysis: A Methodology.” Communitas 17: 21–38.

- Lipovsky, Caroline. 2020a. “Cycling the City: Representation in the French Media.” Language, Context and Text. The Social Semiotics Forum 2 (2): 334–367. https://doi.org/10.1075/langct.19012.lip.

- Lipovsky, Caroline. 2020b. “Free-Floating Electric Scooters: Representation in French Mainstream Media.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 15 (10): 778–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2020.1809752.

- López-Rabadán, Pablo. 2021. “Framing Studies Evolution in the Social Media Era. Digital Advancement and Reorientation of the Research Agenda.” Social Sciences 2022 Sciences 11 (1): 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010009.

- Matthes, Jörg. 2009. “What’s in a Frame? A Content Analysis of Media Framing Studies in the World’s Leading Communication Journals, 1990-2005.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 86 (2): 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900908600206.

- McIntyre, Niamh, and Julia Kollewe. 2019. “Life Cycle: Is It the End for Britain’s Dockless Bike Schemes?” The Guardian, February 22, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/22/life-cycle-is-it-the-end-for-britains-dockless-bike-schemes.

- Norton, Peter. 2008. Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- O’hern, Steve, and Nora Estgfaeller. 2020. “A Scientometric Review of Powered Micromobility.” Sustainability (Sustainability 12 (22): 9505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229505.

- Oeschger, Giulia, Páraic Carroll, and Brian Caulfield. 2020. “Micromobility and Public Transport Integration: The Current State of Knowledge.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 89 (December): 102628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102628.

- Oldenziel, Ruth, and Adri Albert de la Bruhèze. 2011. “Contested Spaces.” Transfers 1 (2): 29–49. https://doi.org/10.3167/trans.2011.010203.

- Onderzoeksraad Voor Veiligheid 2019. “Veilig Toelaten Op de Weg: Lessen Naar Aanleiding van Het Ongeval Met de Stint.”

- Petzer, Brett, Anna Wieczorek, and Geert Verbong. 2020. “Dockless Bikeshare in Amsterdam: A Mobility Justice Perspective on Niche Framing Struggles.” Applied Mobilities 5 (3): 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2020.1794305

- Prytherch, David. 2018. Law, Engineering, and the American Right-of-Way, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham . 1–210.

- Pucher, John, and Ralph Buehler. 2008. “Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany.” Transport Reviews 28 (4): 495–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640701806612.

- Rissel, Chris, Catriona Bonfiglioli, Adrian Emilsen, and Ben J. Smith. 2010. “Representations of Cycling in Metropolitan Newspapers – Changes over Time and Differences between Sydney and Melbourne, Australia.” BMC Public Health 10 (1): 371. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-371/TABLES/5.

- Schäfer, MikeS, and Saffron O’Neill. 2017. “Frame Analysis in Climate Change Communication.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-487.

- Şengül, Buket, and Hamid Mostofi. 2021. “Impacts of E-Micromobility on the Sustainability of Urban Transportation—A Systematic Review.” Applied Sciences 11 (13): 5851. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11135851.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K., and Jonn Axsen. 2018. “Functional, Symbolic and Societal Frames for Automobility: Implications for Sustainability Transitions.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 118 (December): 730–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.008.

- Tuncer, Sylvaine, Eric Laurier, Barry Brown, and Christian Licoppe. 2020. “Notes on the Practices and Appearances of E-Scooter Users in Public Space.” Journal of Transport Geography 85 (May): 102702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102702.

- Urry, John. 2004. “The ‘System’ of Automobility.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (4-5): 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046059.