Abstract

Airports are designed to work efficiently. Specifically, they seek to efficiently process and ‘control’ people’s movements across landside and airside spaces, as well as to entice consumption through the architectural engineering of atmospheres and passenger experiences using architecture (Adey Citation2008; Fuller and Harley Citation2004; Hubregtse Citation2020). However, studies of the design and human sensorial perception of spaces of mobilities have shown that the way people move through and inhabit such spaces transcends the intended functionality of their design (Jensen and Lanng Citation2017). This includes work that considers airports as not only machines of movement, control and profit, but also city-like spaces (Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021; Nikolaeva Citation2013). Based on the conceptualisation of the airport as an ambiguous and city-like space, this paper uses thermal camera video recordings, ethnography, and design mappings to analyse the passenger movements, practices, embodied interactions, and mobile affordances of Copenhagen Airport’s meet and greet area. Focusing on a micro scale, the analysis shows the comparability of people’s practices and ways of inhabiting the airport with practices common to urban public spaces. This facilitates broader reflection on how to speculatively re-design and re-imagine the airport like an urban ‘public’ space.

Introduction

The design of airport spaces prioritises efficiency and commercial profit, seeking to optimise the flow of people from landside to airside, and vice-versa, as well as to entice consumption through the architectural engineering of atmospheres that shape passengers’ experiences, practices and movements (Adey Citation2008; Hubregtse Citation2020). Peter Adey has investigated the relationship between passenger experience and airport design in one western European airport, showing how its architecture creates atmospheres of ‘motion and emotion’ and ‘stimulation and restrain[t]’ (2008, 446). Thus, the architecture of the airport (including signage supplied at the right place and at the right time) is designed such that, at successive stages of the process (check-in, security, the gate), passengers have the feeling of ‘having made it’: a reassuring sense of control over their journey that allows them to remain calm – and to shop (447). Following a similar line of thought, Hubregtse (Citation2020) has investigated design and passenger movements in various airports in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, showing how the design and placement of artworks in terminals creates a feeling of movement while simultaneously enticing passengers to consume, with artworks typically being used as landmarks located close to food courts and retail areas.

However, other research on airports with a focus on passenger experience and design has shown the city-like qualities of airport spaces and demonstrates that they are not only machines of efficient movement, control and commercial profit, but also meaningful places inhabited by people performing their everyday life activities (Gottienner Citation2001; Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021, Citation2022; Lassen Citation2009; Nikolaeva Citation2013). In addition, research within the fields of urban design and mobilities, particularly the field of mobilities design (Jensen and Lanng Citation2017), has shown how spaces of mobilities are inhabited by people in ways that deviate from intended and scripted practices as well as the functionality of their design. Indeed, the design of such spaces affords diverse sensorial and embodied responses that are part of its users’ mundane and meaningful everyday practices. Airports are no exception: They are used and inhabited in multiple and unpredictable ways that frequently transcend their intended functionality, as argued and illustrated by Hubregste (Citation2020) (see also Cresswell Citation2006; Hernandez-Bueno Citation2022). As I will show here, in the case of Denmark’s Copenhagen Airport (CPH), passengers and people inhabit and interact with the airport space much as they do in urban public spaces.1 This similarity reflects and unpacks the urban character and qualities of airport spaces in the way they allow unforeseeable uses and spontaneous forms of inhabitation, despite being designed in rigorous and ‘rigid’ ways to comply with requirements of efficiency, security and safety. As argued by Sendra and Sennett (Citation2020), designing for disorder (i.e. for unforeseen, spontaneous and unpredictable everyday life practices and interactions) is perhaps one of the main qualities that urban environments should provide to build a ‘civil society’ and thereby contribute to the construction of fairer cities by developing ‘life-enhancing design’ (7). This is one of the aims of this paper, which analytically and methodologically explores how design (for spaces of mobilities like the airport) can be humanised to provide, acknowledge and support life-enhancing experiences.

This paper contends that the airport is not solely a city-like space but also an ambiguous space. This is attributed to (1) airport spaces’ unpredictability and changeability in terms of flows, usage and design; (2) the different activities and functions that take place there; (3) the contradictory interests of the different stakeholders and airport authorities; and (4) the diverging definitions and understandings of what an airport is, as I will also explain in the theoretical section of this paper.

Based on the idea of considering airports as both ambiguous and city-like spaces – where contradictory interests co-exist – this paper explores users’ situational micro-practices and movements in the CPH ‘meet and greet’ (M&G) area. This is accomplished by drawing on urban design and mobilities theories that focus on the study of urban life and affective atmospheres of people’s practices in urban spaces (Bissell Citation2007; Chowdhury and McFarlane Citation2021; Gehl Citation2011; Jensen Citation2013; Jensen and Lanng Citation2017; Whyte 1988 [Citation2009]). This study demonstrates the city-like qualities of the airport to develop design speculations, re-imagining the airport as an urban public space. These design speculations are used as a potential analytical mobile method for design research. Thus, the aim is to advance and more precisely unpack the idea of developing airport design as ‘agile’, a notion first introduced by Hernandez-Bueno (Citation2021, 17). The paper sets out to answer the following research questions:

RQ1a: Are airports like cities? If so, RQ1b: how can airports be (re)designed like urban public spaces?

After this introduction, the remainder of the paper is divided into nine parts. The first three parts introduce the theoretical framework, starting with the concept of the airport as an ambiguous and city-like space, followed by a framework that conceptualises the city life and social life of airport space, and finally the airport design approach. The fourth part introduces the methods. The site, analysis of data and the findings and discussion are presented in the fifth, sixth and seventh parts, respectively. These are followed by the explorative development of site-specific design speculations that serve as a base for reflection upon the design of airport spaces from a human perspective. Finally, the paper’s conclusion discusses the implications of this research for transport and urban design and mobilities, as well as potential avenues for future research.

The airport as a city-like space

Within the extensive body of research on airports, there has been an ongoing debate that defines the airport either as a ‘place’ (due to its urban qualities), or a ‘non-place’ (due to its lack of identity and historical meaning) making it clear that the airport is a contested and ambiguous space that conveys multiple meanings.

On the one hand, some research studies define the airport as a city-like place by describing the multifaceted ways in which people inhabit and attach meaning to airport spaces (Adey Citation2008; Cresswell Citation2006; Gottdiener Citation2001; Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021, Citation2022; Nikolaeva Citation2013; Roseau Citation2012). For instance, Cresswell (Citation2006) has unpacked the urban life occurring in the landside areas of Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, as well as the different types of people who inhabit it, such as homeless people and taxi drivers. In this sense, he contends that the airport constructs different types of identities that are both contextual and historically rooted – and, thus, that different citizenships converge at the airport that are ‘assigned’ or performed depending on people’s capacity, abilities and life conditions (citizen, tourist, homeless, taxi driver, frequent flyer, commuter, traveller etc.). In the same line of thought, Nikolaeva (Citation2013, Citation2017) shows in her studies of the design process of Amsterdam Schiphol Airport that the airport is a new kind of urban space that is, in fact, ‘complex and ordinary’ (2013, 47), because different parties involved in the design of the airport work together to create an ‘airport city’, which means imbuing airport spaces with what she calls ‘citiness’. This ‘citiness’ is achieved, for example, by developing identity and sense of place through the design and incorporation of urban space typologies and facilities in both the airside and landside areas of the airport, such as museums, commercial plazas, boulevards, and playgrounds. In addition, Roseau (Citation2012, 50) has analysed airports’ historical development, showing that they are historically and spatially rooted places in that they are developed in symbiotic relation to the cities that host them, as well as according to global and local trends and changes. Recent studies have also advanced the field of study and demonstrated the urban-like characteristics of airport spaces by adopting situational and non-representational approaches to unpack people’s experiences and practices for making sense and meaning of airport space as a place (Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021, Citation2022).

On the other hand, airports also represent inequality, control, segregation and intrusive surveillance in that they unevenly distribute human and non-human flows, information, power and rights, while also profiting from the commodification of people’s experiences (Adey Citation2008). Airports are thought of as efficient machines of movement for different kinds of flows (Fuller and Harley Citation2004) and strategic nodes for exclusively economic (and urban) development (Kasarda and Lindsay Citation2011), perspectives that position them as ‘non-places’. Augé (Citation1995, 94–96) defines ‘non-places’ as spaces that lack historical meaning and are not rooted in the place that hosts them; he further posits that airports are standardised spaces ruled by commands communicated through signs and text (e.g. signage systems) where people inhabit a ‘modern form of solitude’ (93). Thus, as Fuller and Harley (Citation2004, 38) affirm, airports’ design and identity are themselves standardised.

These conflicting understandings of the (definition of the) airport make it an ambiguous space: a space of contradiction (Adey Citation2010, 12) and ‘dialectical tensions’ (Mela Citation2014, 1). This is reflected in the process of developing and (re)designing airport spaces, where different actors negotiate their different and oftentimes conflicting interests (see Nikolaeva Citation2017). In addition, Mela contends that cities are, to some extent, characterised by rules and norms that aim to ‘control’ people’s behaviour; however, cities are also subject to people’s behaviour and practices that counter such norms of control and order (2014, 1). Like city spaces, airport spaces operate within the same dialectical tensions, as I will show in some examples of the data analysis of the ‘M&G’ of CPH, where passengers and other airport visitors engage in practices that contradict the operational, safety and security interests of the airport (for example, by waiting in restricted areas). Therefore, it is within such ambiguity and dialectical tensions that the city-like qualities of the airport flourish and can be recognised. Of course, depending on the country airport authorities might be more stringent in discouraging people’s practices that contradict the airport ‘rules.’ Moreover, policing of behaviour may be subject to emergency periods (e.g. terrorism alerts or pandemics).

Building on the idea of the airport as an ambiguous space, this paper advances the understanding of the airport as a unique typology of urban space in its own right: a city-like space that is both an efficient machine and a place (that is, a space for temporary human inhabitation). In so doing, this paper provides detailed ethnographic and affective accounts of people’s micro-practices, movements and interactions with space in specific situations within the CPH M&G, thereby showing how the built environment ‘affords’ a variety of behaviours (see section 3 for an explanation of the meaning of affordance). Such ethnographic accounts showcase the ambiguity of the space, as well as how specific designed artefacts mediate the tensions between the different actors’ practices, thereby unpacking the city life and ‘urban-ness’ of airport space.

The concept of ambiguous space has been addressed in recent years by other scholars within the arena of urban design (see Hajer and Reijndorp Citation2001, 33). What the concept of ambiguous space allows us to understand, especially in relation to design, is the urban qualities of spaces of mobilities (such as airports), as well as the potentialities of these spaces to become (recognised as) agorae of human inhabitation (Jensen Citation2020). These potentialities are usually ‘hidden’ behind orthodox design ideas and narratives of order (Jacobs Citation1961, 150), functionality and efficiency that spaces of mobilities ‘require’ and are designed for. However, this does not mean that functionality and efficiency are unimportant parameters for the design of spaces of mobilities; rather it is the manifestation and interplay of order and disorder, as well as the ‘messiness’ of human life, that characterise both the city itself and city-like spaces (Jensen and Lanng Citation2017).

By adopting the approaches of urban design, mobilities and affectivity, I will provide detailed accounts of three situations during the arrival experience: (1) passengers arriving (being on the move), (2) ‘meeters and greeters’ waiting (people waiting to meet and greet), and (3) the act of meeting and greeting itself. This understanding can potentially be used to inform airport design decisions from the human perspective. Within the body of research on passenger experience there is a tendency to inform design solely in terms of efficiency, functionality, flexibility, safety, security and profit (see, e.g. Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021). In that respect, the findings of this paper will discuss and draw implications within the field of urban design and mobilities to humanise the design of spaces of mobility (i.e. make them spaces for human inhabitation).

The city life of airport space: Social practices, affective atmospheres and urban rhythms

To advance the understanding of the airport as a unique urban space typology – and thereby provide new insights into its ambiguity and city-like attributes – I will analyse the body of literature that studies the experiential and affective dimensions of urban life, especially research into practices of being ‘on the move’, inhabiting and waiting in mobility, and urban public spaces. In so doing, I will discuss the implications of such analysis for informing urban design and airport design from a human perspective.

First, I will show that people’s micro-practices of inhabitation, interactions and movement in the M&G area are comparable with practices unfolding in urban public spaces. In so doing, I will draw upon the work conducted by Jan Gehl, William Whyte and Ole B. Jensen within the field of urban design for studying people’s behaviour in urban public spaces. The investigations of Gehl (Citation2011) and Whyte (1988 [Citation2009]) cemented the importance of putting people at the centre of design and planning decisions to ‘make cities for people’ – an idea that proved crucial in creating liveable, sustainable and vibrant places, especially against the urban challenges that arose from modern life as well as ideas of order and zoning for city design (see Jacobs Citation1961). In addition, Jensen (Citation2013) provided a vocabulary to understand nuanced and situated interactions of people on the move. However, their research does not actively explore how the affective dimensions of micro-scale practices have implications in terms of developing (and transferring) skills and competencies for contemporary urban inhabitation (urban literacy). Nor have such studies explored the role of design in co-shaping and co-developing people’s urban practices based on the affective responses of people’s interactions with and within space. In this sense, I will address the affective dimensions of people’s practices and ways of inhabiting airport space on an intimate scale.

Second, to unpack the affective dimension of urban life and show how skills and literacy acquired in urban public spaces are mobilised by people in the airport, I will draw upon Bissell’s (Citation2007) and Chowdhury and McFarlane's (Citation2021) work on waiting and density and crowds, respectively. These authors offer a critique of the understanding of the events and experiences of waiting and being in crowds, phenomena which are often viewed from normative and productivist perspectives within the research areas of mobilities and urban studies. They insist that such urban events must be taken seriously by unpacking them as they are: lived and corporeal experiences enmeshed in everyday and quotidian life. This approach aims to shed light onto, and provide nuanced insights into, city and urban life experiences. Waiting and crowd experiences are also present in the CPH M&G. In fact, and according to Chowdhury and McFarlane (Citation2021), such events characterise and thus define the city and urban contemporary life as we know it.

By taking a phenomenological, performative and affective approach, Bissell (Citation2007) calls for a shift in the way we understand waiting within the mobilities field. In particular, he criticises how the relationship between mobilities and immobilities is often framed under economic and productivist rationales. In Bissell’s words, the mobile body is usually seen as 'the more desirable relation in the world’, with focus on how travel time is spent ‘and, as a consequence, focus is often directed towards different modalities of engaged activity’ (278). In that sense, and to counter such perspectives, Bissell describes the event of waiting as a ‘relative embodied activity or inaction’ rather than dead time (278, original emphasis). Through that concept, he aims to animate the event of waiting by viewing it ‘through the activities of the active and engaged body-in-waiting and the various bodily demands and corporeal attentiveness that waiting entails’ (278). In that regard, this paper advances knowledge on the ‘corporeal experience’ and ‘suspension’ of waiting by adding a nuanced layer of the micro-practices of ‘different species of waiting’ and their implication for (urban) design (282). I will show how waiting in the M&G produces a variegated ‘affective complex’ (294) that, in turn, advances the idea of waiting ‘as a social event, rather than a collection of feeling individuals’ as well as how ‘the affectivity of waiting becomes transpersonal’ (291).

In addition, Chowdhury and McFarlane study the relations that bind crowd and city life beyond normative claims (e.g. ‘good’ or ‘bad’ density), which entails approaching density and crowd ‘not through numbers, a priori definition of technical categorisation (e.g. for optimisation) but as experiences of urban compression’ (Chowdhury and McFarlane's Citation2021, 1357). By adopting this approach, and through ethnographic accounts of passengers in Tokyo’s train stations, both authors illustrate ‘crowd relations’ that represent ‘evocations of city life’ and position the crowd as a vital part of social life (1360). Drawing upon their work, this paper also adds a nuanced layer for understanding urban rhythms and crowds as lived experiences, with the aim of expanding scholarly understanding of how the crowd, as they argue, cultivates ‘practical competencies of citylife… and how these capacities and ascriptions are contingent on differentiations of urban space’ (1369). In this paper, I will show how such practical competencies acquired in urban public spaces are mobilised and thus performed in the M&G to make sense and meaning of place, rendering it a city-like space. This also means that the urban-ness of airport space does not rely solely on its design and level of ‘publicness’ (or lack thereof), but rather on the way people use, inhabit and appropriate it.

Third and finally, to present the urban design implications of my analysis of the M&G, I will draw upon the concept of airport design as ‘agile’, originally developed by Hernandez-Bueno (Citation2021), to show that design and infrastructure are agile, rather than fixed (Graham and Thrift Citation2007). To expand the concept of agility, I will draw upon Mobilities Design by Jensen and Lanng (Citation2017), particularly their call for re-imagining spaces of mobilities through the use of design speculations. I will also draw upon Graham and Thrift’s Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance (2007) to showcase how, like the city, the airport requires constant upkeep and re-adjustment of its spatial design. However, I will pay particular attention to the human-design element on a micro scale, as exemplified in the constant clearing of passengers by security personnel and implementation of nudging elements, as well as the renovations they underwent during this research. In particular, leveraging the work of Graham and Thrift (Citation2007), I will show how the agility of design relies on the ‘laboratory conditions’ of airport space (Fuller and Harley Citation2004; Roseau Citation2012). This means that processes of ‘repair and maintenance’ of small-scale designed artefacts and situations can produce ‘feedback loops for experimentation and learning’ (Graham and Thrift Citation2007, 5), or can even produce a ‘learning airport’, a term coined by Lassen, Jensen, and Hernandez-Bueno (Citation2020). Thus, the agility of design relies not solely on its capacity to be flexible, adaptable, changeable or expandable, but also in its utility as a tool to exploit the airport’s laboratory conditions.

My contribution differs methodologically from the above-mentioned references by combining different sources of data to depict practices of urban inhabitation at a small, intimate scale, in turn revealing the politics of airport experiences and design at a larger scale. With this paper, in which I posit a need to explore ‘mobile methods’ for design research (Büscher, Urry, and Witchger Citation2011), I seek to encourage exploratory and experimental forms of graphical urban analysis and ethnographic accounts of urban life. In daring to mobilise sketching and design iterations through design speculations to explore these gaps, I humbly hope that they will have a significant impact within design fields. In this regard, I follow Jensen and Lanng's (Citation2017) ideas of studying the material sensitivities of spaces, as I will explain in the next subsection.

Airport design as agile: Mobility affordances and design speculations

Airport design is intended primarily to streamline – and profit from – the flow of people, information and goods. Airport architecture is designed with the goal of facilitating movement and atmospheres conducive to consumption (Adey Citation2008; Hubregste Citation2020), as well as to accommodate flexibility and expandability to cope with risk and the unpredictable and changeable nature of aviation, aeromobilities and passenger behaviour (Edwards Citation2005; Magalhães, Vasco, and Rosário Citation2017, Shuchi, Drogemuller, and Buys Citation2017; Nikolaeva Citation2013).

In the context of the airport as a city-like space, the field of airport design is contested ground: Whereas some stakeholders prioritise efficient movement of passengers, others want to make them stay longer and spend more time (and money) in airport shopping areas (Nikolaeva Citation2017). In this sense, airport design should not only permit the secure and efficient processing of people, goods and information, but must also allow and provide space for different forms of inhabitation by people. In other words, as Hernandez-Bueno (Citation2021) contends, airport design should be ‘agile’ in how it accommodates and responds to multiple meanings that people ascribe to the same space, and people’s ways of making sense of space.

Hernandez-Bueno's (Citation2021) conceptualisation of airport design agility is based on her empirical analysis of CPH from the mobilities design perspective (Jensen and Lanng Citation2017). The field of mobilities design seeks to understand the design (decisions) of spaces of mobilities, as well as the meanings of mundane mobilities, from a material, pragmatic and non-representational viewpoint. According to Jensen and Lanng (Citation2017, 40) mobilities design calls for a ‘material turn’, which means incorporating a new sensitivity into the material surfaces as well as people’s interaction with, and perception of, the environment beyond canons of efficiency and functionality. To incorporate this new sensitivity, mobilities design invites designers to understand specific mobile situations, which Jensen (Citation2013) describes as social and material interactions on the move – in particular, the affective and embodied practices of people, as well as the ‘affordances’ of designed artefacts beyond what they ‘represent’, by asking: ‘how are design decisions and interventions staging mobilities?’ (2017, 40). The concept of ‘affordance’, originally coined by Gibson ([1979] Citation2015, 119), refers to what the environment offers to the animal. The notion of affordance adopted here aligns with Jensen and Lanng's (Citation2017, 53) definition of ‘mobility affordances’ inspired byHarry Heft's reworking of Gibson's concept, where focus is given to the ‘situational and action-oriented’ understanding of people’s spatial experience and perception (2017, 18).

In addition, this new sensitivity also calls for the implementation of design speculations and experimentation to critically and creatively re-design spaces of mobilities by asking ‘what if…?’ (41). In their studies of parking lots and tunnels in Aalborg East in Denmark, Jensen and Lanng (Citation2017) show how spaces are inhabited in different ways, as well as how design affords and entices not only efficient movement from A to B and scripted practices, but also embodied, sensorial and meaningful experiences and activities of people inhabiting space. (These include activities and practices that allow people to make sense of space.)

This paper draws upon the concept of ‘agility’ and the mobilities design field to analyse the spaces of the M&G beyond functional, operational and commercial aspects, paying serious and sustained attention to the mundane practices and meanings of people’s practices and movements in space. This is done with the aim of developing design speculations that can, in turn, inform design decisions from a human perspective. Design speculations are seen here as opportunities to discuss and engage actors – thereby highlighting the potential of design as an active analytical and research tool to uncover the ‘real’ problems and nuances of prosaic urban life (Christensen, Melvin, and Hernandez Bueno Citation2022). In this sense, design speculations are used as a way to showcase the potential of the airport to be a humanised place.

Humanising the design of airport space is about more than applying parameters in a normative way. It is also, as mentioned, about the potential ways in which design can be used to engage different actors (e.g. researchers, designers, users) in conversations about taking seriously people’s practices and ways of making meaning of space. This is what the design speculations aim for: They dare to engage – materially and spatially – and to acknowledge the site-specific practices and meanings often overlooked by designers.

Methods and data gathering

To capture people’s practices and movements at a micro scale, and thereby render a holistic understanding of the arrival experience in the M&G, a mixed-methods approach was adopted, comprising the use of ethnography, design mappings and thermal camera video recordings.

Ethnographic observations and design mappings were used to capture spatial qualities and conditions, as well as people’s practices and movements – both in situ and from the researcher’s sensorial perspective. This means that it was possible to experience and map the different mobile situations, ambiances and atmospheres of space, as well as the rhythms of flow and social interactions from the researcher’s point of view. These observations were conducted over the course of several visits to the airport between 2017 and 2018, and during a planned data collection in summer 2018 that included the deployment of thermal cameras. The long-term ethnographic studies and design mappings of the site granted the researcher a better understanding of the spatial qualities and dynamics of the space; this understanding informed the selection of focus areas where the thermal cameras would be installed.

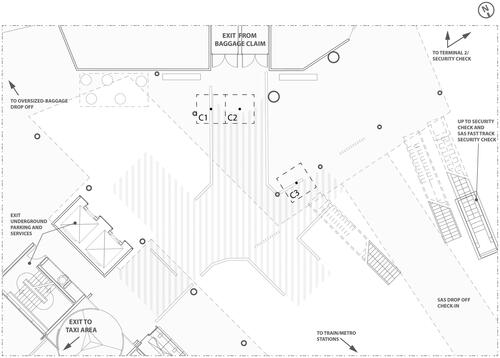

Thermal cameras were used to capture the (embodied) interactions between passengers and ‘meeters and greeters’ at an intimate scale. Thermal cameras capture people’s body temperature and therefore do not compromise their privacy (see Jensen et al. Citation2020). Three thermal cameras were installed (see ): two over the corridor of arriving passengers, in front of the exit door from customs (C1 and C2), and one in a small section of the waiting areas (C3), to capture the interaction between arriving passengers and ‘meeters and greeters’ in three distinctive spatial conditions and situations.

Figure 1. ‘Meet and greet’ area with location of thermal cameras installed in summer 2018. Source: own; plan drawing: Copenhagen Airport, adapted by the author and used with permission.

The summer 2018 data collection spanned the last week of August and the first week of September, with the aim of collecting data during the holiday and business peak seasons, respectively. Observations and mapping were conducted only on Tuesdays each week, and the thermal camera footage was analysed only for selected peak days, during specific peak hours, based on the analysis of tracked human flows and the number of people arriving. Algorithms were used to track people’s position in space and time across videos recordings, thereby counting the number of individuals per hour.

The 'meet and greet’ area of CPH

CPH is an international hub airport located 8 km south-east of Copenhagen. It is the main hub for SAS airlines. Between 80,000–100,000 passengers travelled through CPH every day during 2019. During 2023, an average of 73,000 passengers passed through CPH each day. The ‘meet and greet’ (M&G) area of CPH is located on the ground floor of the landside area of Terminal 3. The landside is defined as the most public area of the airport. The M&G area is the arrival and welcoming space for passengers after they pass customs and baggage claim; thus it is passengers’ first encounter with the landside area and the city of Copenhagen. This space works as a distribution node for inflows and outflows of people within and across two levels. On the ground floor, passengers are distributed to the arrival hall and the different transportation systems that connect to the city. In addition, some passengers coming from the taxi area are distributed to the check-in counters located in the arrival hall. Vertically and on the first floor, this area distributes passengers coming from the taxi areas, train and metro stations, and bus stops to the security check areas located on the first floor.

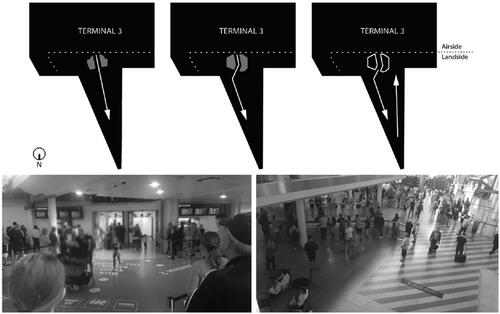

Whilst conducting this research, the M&G area underwent various physical renovations to optimise the distribution of human flows coming in and out of the airport and to expand the space for airport operations. This included the installation and testing of mock-ups, such as temporary barriers and coloured foil on the floor as a nudging element that led to the permanent implementation of barriers and floor signage. The new design of the space layout presented challenges in terms of the intuitive spatial legibility of architectural cues for arriving passengers (e.g. finding their way out of the airport) and ‘meeters and greeters’ (e.g. understanding where to wait for their relatives), prompting the incorporation and re-adjustment of signage elements. shows the before-and-after situation of the design of the M&G area based on the ethnographic studies conducted during the research period.

Figure 2. (a) The M&G area before and after renovation; (b) the area during the renovations carried by the airport designers and authorities in summer 2017, where a ‘red carpet’ foil was implemented to nudge arriving passengers towards the main exits; (c) M&G area after renovation in summer 2018. Source: own.

Passengers’ embodied interactions and mobile affordances

In the M&G area, various mobile situations showed the embodied interactions among different types of airport users and in relation to the built environment (passengers, ‘meeters and greeters’, airport staff). The mobile situations analysed in this area are passengers arriving, meeters and greeters waiting, and passengers meeting and greeting.

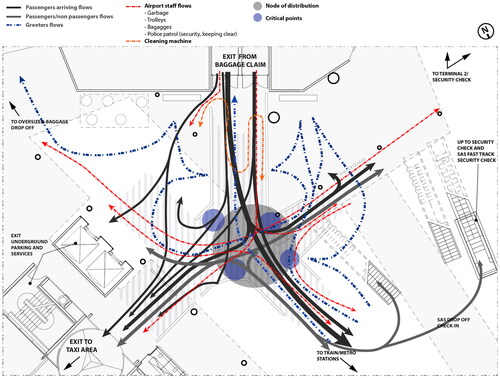

Passengers arriving to the ‘meet and greet’ area

As shown in and , the flow of passengers arriving is intersected by the flow of other passengers and airport visitors heading towards other areas like the security check and check-in counters in Terminal 2, by staff working, and by ‘meeters and greeters’ waiting in the area. Those different flows intersect because of the spatial configuration of the area created by the barriers located there. According to the airport designers, those barriers are used to frame both the waiting areas for ‘meeters and greeters’ and the flow areas of arriving passengers, thereby nudging the different flows towards certain areas to avoid disruptions that can affect efficiency, security and safety (Personal communication, 2018).

Figure 3. Mapping of passengers and other airport users flow interactions in the M&G area. Source: own; base plan drawing: Copenhagen Airport, adapted by the author and used with permission.

Figure 4. (a) Intersection of passengers, airport staff and people waiting; (b) flow of passengers heading to the arrival hall at the north side of Terminal 3. Source: own.

Upon arrival, passengers looked around to find their way and/or those who had come to meet them (see ). Once they found them, they smiled and greeted them with hugs (see third subsection). Some arrivals oriented themselves towards the north, perhaps towards the terminal exit and the signage areas (). Other passengers took an improvised ‘shortcut’ () through one of the waiting areas, presumably to avoid the crowd or perhaps reach the taxi rank more quickly. This shortcut is an opening located to the north-east of the exit door that is used by airport staff, such as security or cleaning personnel, to avoid the crowd and move efficiently.

Figure 5. (a) passenger looking around and finding the way; (b) passenger pointing to the way out; (c) passengers looking at the signage above the intersection node; and (d) passengers taking the ‘shortcut’. Source: own.

Some passengers displayed the hallmarks of being frequent travellers. Arriving as part of a group with their colleagues, they stopped for a very short time at the intersection of flows to say goodbye to each other. At this intersection, passengers formed temporary congregations before parting ways.

As observed in the thermal camera recordings and in situ, in some situations () arriving passengers overtook others, whereas others stopped in the corridor to wait for fellow passengers emerging from customs.

Figure 6. Thermal camera images showing (a) passengers arriving; (b) passengers stopping in the corridor while waiting for others; and (c) one passenger overtaking another. Source: own.

During the ethnographic studies, it could be observed that the passenger flows have certain rhythms that affect a dynamic and bustling atmosphere. For example, it was easy to spot the peak hours in terms of flows of passengers arriving and people waiting. When several flights arrived at the same time, crowding intensified very quickly for a couple of minutes. When the flow of arriving passengers slackened, the area became calmed and quiet, making it easy to recognise the constant security announcements of the airport authorities.

Meeters and greeters waiting

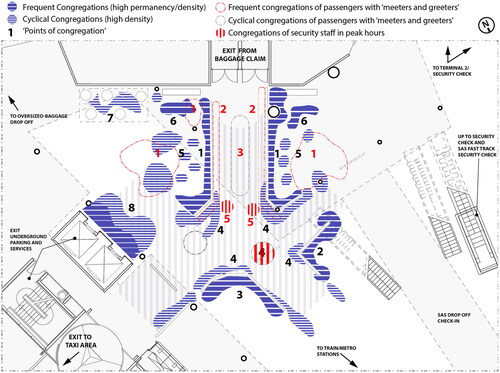

As shown in , ‘meeters and greeters’ congregate especially along and on both sides of the barriers (inside and outside the waiting areas), in the flow areas, and in the corners of the intersection node created by the disposition of the barriers – areas that are constantly cleared by airport security staff during peak hours because they interrupt the flow of passengers arriving and block the emergency exits located to the east.

Figure 7. Mapping of ‘meeters and greeters’ and airport staff congregation patterns and interactions with the built environment.

Note: The diagram shows the frequent and cyclical congregations of ‘meeters and greeters’ based on the duration of permanency (blue shadowed areas) and points of congregation (black numbers), frequent and cyclical waiting areas where ‘meeters and greeters’ welcomed and met their relatives and friends upon arrival (areas marked with red and grey dotted lines) and points of encounter (red numbers), and the areas where security staff congregated during peak hours (red shadowed areas) and points of congregation (red numbers). Congregations of ‘meeters and greeters’ along the barriers inside the waiting area (black numbers 1 and 3) and along the barrier outside the waiting areas (black number 5), in the corners of the intersection node (black number 4), in front of the information boards (black number 6) and in the café table areas (black number 7). Source: own; base plan drawing: Copenhagen Airport, adapted by the author and used with permission.

Figure 8. (a) and (b) ‘Meeters and greeters’ waiting along the barriers, and (c) in one of the corners of the intersection node; (d) Police clearing the ‘meeters and greeters’ that wait in the corridor and corners of the intersection node. Source: own.

‘Meeters and greeters’ dwell along the barriers by laying and resting on them, listening to music, reading books and drinking coffee (using the barrier as a table), and talking to their companion(s), if any ( and ). Children waiting use the barriers as seating and interact with them in playful ways. ‘Meeters and greeters’ also wait around columns (leaning on them or sitting against them on the floor) close to the information boards, against walls of the elevator shaft, in a café table area located close by, and areas that have good visibility to the exit door from customs and to the flow of passengers arriving (). They also perform practices of spatial appropriation that include the use of ‘props’, such as chairs moved from the café table area to the waiting areas or re-arranged in space to have better visibility towards the door from customs.

Figure 10. ’Meeters and greeters’ performing dwelling practices (a) on the barriers, (b) and (c) around columns and (d) by re-arranging the chairs in the café table area. Source: own.

Figure 11. Thermal camera images showing (a) business partners with a small board and a person resting their arms and head upon the barrier; (b) and (c) interactions among people waiting and congregation of people around the barriers and in space while waiting. Source: own.

Some of the ‘meeters and greeters’ carried welcoming signs, balloons, flowers and Danish flags to welcome their relatives – carrying Danish flags for celebrations is a very common practice in Denmark and part of the Danish celebration culture (see figures in the following sub-section). In addition, it was observed that there was a group of business partners awaiting colleagues or clients. They usually carried digital or paper boards with the names of the passengers for whom they were awaiting ().

A common waiting pattern observed was that some ‘meeters and greeters’ followed others’ waiting patterns and practices. In other words, the presence of ‘meeters and greeters’ waiting in certain specific areas attracted others to wait nearby, and their practices of appropriation influenced and ‘taught’ others different possibilities of how to wait and dwell in space. In addition, the thermal camera video recordings showed how ‘meeters and greeters’ waiting along the barrier gradually moved towards the exit door from customs, also forming cyclical patterns of waiting. In some instances, meeters and greeters who spotted their relatives arriving left their spot along the barrier to meet them, allowing others to move forward.

The presence of ‘meeters and greeters’ and their practices explained above created urban atmospheres that were simultaneously homely, dynamic, bustling and business-like. In particular, the micro-interactions among different groups of people waiting, the built environment, and those arriving unpacked the social and collective aspects of temporary inhabitation thereby creating an urban atmosphere.

Passengers meeting and greeting

The most common social practices observed between passengers and people waiting were greeting, hugging and shaking hands at the barrier (see ). For example, business partners shake hands at the barrier once they recognise and find each other ().

Figure 12. (a) Greeting situation between ‘meeters and greeters’ and a passenger, (b) Two people waiting interacting between the and arriving relative. Source: own.

Figure 13. Greeting situations between business passengers and partners waiting: (a) shaking hands, (b) getting instructions in the waiting area for business. Source: own.

Figure 14. Greeting situations between ‘meeters and greeters’ and passengers: (a) hugging at the barrier, (b) and (c) hugging in the flow corridor of passengers arriving, (d) passengers congregating in the waiting areas. Source: own.

In addition, and as mentioned above, passengers and ‘meeters and greeters’ greeted and hugged at the barrier and, on occasion, stayed for a short period talking ( and ). Afterwards they moved to the waiting areas to further celebrate their reunion. In some situations, ‘meeters and greeters’ moved from the waiting areas towards the corridor where passengers were arriving to greet and hug them (). Passengers and their relatives usually stopped and hugged in the corridor and then moved together to the waiting areas. In most cases, when a group of relatives were waiting, some of them stayed in the waiting areas while one or two of the other members moved to the corridor to ‘pick up’ the arriving passenger. Once again, children were observed interacting with the barriers in particularly playful ways. Some kids sat over the barrier to see the exit door and passengers arriving, and in one case a child jumped over the barrier to greet her arriving relatives ().

Practices of meeting and greeting created emotional, playful and sometimes touching atmospheres. The act of meeting and greeting was followed by emotions of joy, excitement, love and reunion. Some people became very euphoric; others, especially children, ran happily to hug their arriving relatives, while others cried or hugged romantically for an extended time.

Findings and discussion

The analysis shows that spatial design and particular designed artefacts afford multiple practices and movements of passengers and people that do not follow only the functionalities intended or expected by airport designers and governing authorities (Hubregtse Citation2020; Jensen and Lanng Citation2017). This highlights that airport spaces and their architectural artefacts are multifunctional and adopt different meanings for users depending on the specific situation. In the case of the M&G, the predominant efficiency narrative of its design is frequently interrupted and countered by different micro-practices and movements, as well as the social and material interactions of passengers and those awaiting their arrival.

Moreover, mobile situations observed in CPH are comparable with, and in some instances very similar to, situations that unfold in urban public spaces (Gehl Citation2011; Jensen Citation2013; Whyte [1988] Citation2009). We may draw attention to two specific ideas here: the agency of corners and edges, and the urban ballet. For instance, ‘temporary congregations’ (Jensen Citation2013, 4) of passengers occurred not only in front of the information screens but also inside the main areas of flows, and around columns and corners. As Whyte illustrates in his studies of social life in urban spaces, particularly in relation to sidewalks (flow areas) and street corners ([1988] 2009, 8):

The people who stop to talk did not move out of the main pedestrian flow; and if they had been out of it, they moved into it… What is less explainable is the inclination to remain in the main flow, blocking traffic, and being jostled by it. This seems to be a matter not of inertia but choice – instinctive perhaps, but by no means illogical. In the center of the crowd, you have maximum choice – to break off, to switch, to continue… It is a behavior universally deplored and practiced

In addition, in his studies about people’s behaviour and dwelling habits in public spaces of Copenhagen and other European cities, Jan Gehl (Citation2011, 149) mentioned the so-called edge effect (coined by Derk de Jonge), referring to the edges of public spaces, buildings (e.g. facades) and other urban artefacts (e.g. columns of building galleries) as the most popular places for staying, waiting and dwelling. The edges of the urban environment, as Gehl argued, provide both opportunities for surveillance (to look out over the space) as well as a safe space for people to dwell where ‘[o]ne is not in the way of anyone or anything. One can see, but not be seen too much, and the personal territory is reduced to a semicircle in front of the individual. When one’s back is protected, others can approach only frontally, making it easy to keep watch and to react…’ (ibid.).

As shown in the empirical analyses, these ‘temporary congregations’ attracted other people and passengers to congregate and wait ‘together’. As in the case of urban public spaces, ‘what attracts people most, in sum, is other people’ (Whyte [1988] 2009, 10). As Gehl illustrates, ‘human activities attract other people’ because ‘activities begin in the vicinity of events that are already in progress’ (2011, 23). This was observed when certain waiting and dwelling practices performed by ‘meeters and greeters’ and passengers were followed and ‘copied’ by others in space, and also in the way ‘meeters and greeters’ distributed themselves around – and as close as possible to – the exit door from customs, which acted as the stage for the main event being awaited: the arrival of passengers. Moreover, it was not only the presence of people (passengers and ‘meeters and greeters’) that attracted other people, but also specific architectural features. These artefacts – such as the aforementioned customs exit door, the screens and signage for finding information about arriving flights, and the barriers and columns with good visibility to the exit door – played an important role in practices of waiting, dwelling, meeting, and greeting. In terms of the flow’s ‘ballet’, passengers arriving were negotiating their way with other passengers on the move, ‘meeters and greeters’, and the built environment (Jensen Citation2013). This practice of mobile negotiation reflects the ‘cooperative effort’ observed by Whyte ([1988] 2009, 57) in urban public spaces in terms of the adaptability of people’s flows to avoid collisions and make sense of space.

The above-mentioned examples vividly show how urban skills and capacities of inhabiting urban space are mobilised and transferred by ‘meeters and greeters’ and passengers moving and waiting in the M&G to make sense of space. This practice of knowledge transference based on previous experiences is also seen in other research in urban public spaces, train stations, and even airports (see Chowdhury and McFarlane Citation2021; Degen and Rose Citation2012; Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021), thereby demonstrating that such practice is a vital part of city life and what it means to be human in urban environments. This finding has implications in design – and particularly in the idea of airport design as agile, and not static – because changes in people’s behaviour in the city and ways of understanding urban space may also be transferred to airport spaces.

What we see in the M&G are also micro-practices of temporary waiting where people engage in different embodied (in)actions and rituals (Bissell Citation2007). By looking at the ‘corporeal experience of waiting’ (289), it is possible to map out a waiting ballet taking place in the M&G – in order words, a continuous and very subtle repetition of waiting practices (such as those observed along the barriers) that creates social rhythms of waiting in ‘preparation’ for the event to come. Most importantly, and beyond showcasing waiting solely as a sort of urban rhythm, this waiting ballet reflects the act of waiting as a collective encounter and social event (Brown 2005 in Bissell Citation2007, 285); that is, as a ‘wholly active and co-managed interaction’ (Bissell Citation2007, 285). As illustrated also by Bissell (Citation2007), these practices of waiting do not portray a still or static body; on the contrary, the event of waiting in the M&G requires the body to be in constant re-adjustment in space and even territorial appropriation to find its ‘equilibrium’ and maintain readiness. The act of waiting in the M&G comprises micro-movements, pauses and disruptions that certainly demand bodily engagement: ‘a kind of relation-to-the-world that transcends and folds through this relational dialecticism of (im)mobility’ (284).

In this waiting ballet we also see the affective influence of people’s practices and how skills are learnt and ‘transferred’ between people waiting, thereby showcasing a city life that is characterised by rapid fluctuations of densities: rich micro-negotiations and body adjustments within the crowd in space, resulting in replications of practices of appropriation. As Chowdhury and McFarlane (Citation2021, 1367) argue: ‘Being among crowds emerges as a practical workshop for differentiating people and behaviours in public spaces and the cultivation of a politics of urban belonging through which citylife – always shaped by social norms, inheritances and changing city persona– is negotiated and remade’.

The discussion above shows that the M&G works like an urban public space, and is not solely a space for the arrival and efficient distribution of flows. The movements of passengers and other users are dynamic and organic – sometimes messy – and although the flows and congregations of people follow certain rhythms and patterns, passengers and people perform practices of appropriation and temporary dwelling that do not follow the script and functional narrative of the designed built environment. Rather, they inhabit the space in unpredictable ways and perform practices that are comparable to those performed in urban public spaces. In terms of ‘citiness’, it is important to note that in the CPH M&G we do not find homeless people, museums or libraries that mimic the urban qualities of airport spaces, as Cresswell (Citation2006) and Nikolaeva (Citation2013) illustrate. However, we do find people reading books, talking on the phone while waiting, having business meetings, sipping coffee, saying goodbye to a colleague, chatting in a corner, greeting one another, etc. We also find emotional and touching encounters: families reunited, love stories and children playing. These are situations that we could also witness in urban public spaces and other spaces of mobilities, like train stations and shopping malls. In other words, the M&G is a space where social interactions and meaningful everyday practices take place – a new mobile agora (Jensen Citation2020), and not solely a space for travelling and travellers. The M&G is a space where temporary encounters among different people enact urban and social atmospheres. It is also a space that is continuously changing, both spatially and in terms of people’s flows, where the subtle (or abrupt) re-design, incorporation, and re-configuration of the location of designed artefacts and spatial conditions (e.g. barriers, floor foil, signage, and other informational elements) is constantly carried out on the move, rendering it a process in the same way that cities are (Amin and Thrift Citation2002).

Design speculations

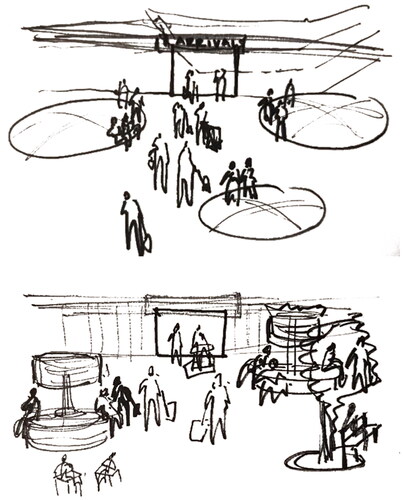

Whilst past work has pointed out some of the city-like qualities of the airport space, the above micro-scale observations on the interactions between design and mobilities allow us to pose a question: What if we design the M&G like an urban public space? (For example, by modifying the architectural artefacts and spatial features to respond to the site-specific mobile situations observed.) and show design speculations, developed by the author, where the re-design of already-existing elements – such as the barriers and the floor surface – accommodates the interactions and dwelling practices of passengers and ‘meeters and greeters’.

Figure 16. Barriers as pockets for first encounters and temporary greetings: Re-design of barriers that respond to the mobile situation of ‘meeting and greeting’, thereby affording slow and fast movement and temporary congregations. Source: own.

Figure 17. (a) Floor surface as a landscape to create pockets for first encounters and temporary greetings that also facilitate sitting, leaning and playing; (b) tree-like structures and green features that afford free flow, interactions and congregations. Source: own.

As exemplified in the design speculations, providing ‘agility’ in this specific case means creating environments that respond in a performative way to site-specific mobile practices and forms of inhabiting space. Adopting a human-centric approach to humanising airport spaces is not only about considering people’s needs and behaviour but also about integrating those overlooked micro-scale interactions that co-shape and ‘belong’ to the place – that are site-specific and thus give meaning to, and construct, the identity of that place. In addition, and beyond these normative guidelines, the design speculations have the potential to initiate design discussions that consider such micro-scale routines and ways of being human in the airport. Such conversations can hopefully boost the already-present nature of the airport as a laboratory for experimentation where design and its micro-adjustments become ‘one of our chief means of seeing and understanding the world’ (Graham and Thrift Citation2007, 5).

Conclusions

This article has used the case of the M&G area in CPH to argue that airports are like cities. The city-like qualities do not rely only on the way the airport accommodates non-aviation activities, or on the public nature and access of the landside area, but also on the way passengers and airport visitors interact, inhabit and make sense of space at a micro scale (see, e.g. Hernandez-Bueno Citation2022, where city-like qualities and ‘urban’ practices of dwelling and appropriation are performed by passengers in the airside areas). The airport consists of ‘open-minded’ spaces (Walzer 1986 in Jensen Citation2013, 147) and situations where messy urban life unfolds, and where passengers and airport visitors have the ‘freedom’ to perform practices of dwelling and appropriation that don’t fit with security, safety and efficiency expectations and narratives. This also reflects the ambiguity and dialectical tensions of the airport as a place of both control and freedom of movement.

The significance and implications of this research for transport design, urban design and mobilities design lie in the potential to explore (and hence exploit) the ambiguity of such spaces of mobilities at micro and intimate scales – such as by using (design) experimentation to return human and ‘urban’ dimensions to the centre of design processes. As shown above, people’s behaviour, movements and practices cannot be fully controlled, even in a heavily secured space like the airport. In this sense, the city-like qualities and ambiguity of the airport reinforce its laboratory conditions (Fuller and Harley Citation2004; Roseau Citation2012) and open the possibility of potential explorations of urban design concepts (on the move) that aim to humanise transportation infrastructures by responding to – and hence facilitating – ‘loose’ and ‘life-enhancing’ frameworks for spontaneous, everyday life situations and interactions to take place (Sendra and Sennett Citation2020). The design speculations in the previous section represent a modest intervention of this sort. As argued elsewhere, the airport is a design intervention (Hernandez-Bueno Citation2022) due to its changeable and unpredictable nature, and is therefore already a ‘process’ – as cities are.

In addition, the findings of this paper have implications for our understandings of fair and just cities. Designing mobility environments for fairer cities means paying particular attention to site-specific micro-situations and temporary ‘moments of encounter’ (Amin and Thrift Citation2002, 30). In their performance, these moments unpack the city-like qualities, identities and meanings hidden in the way people on the move engage bodily and experientially with space. Therefore, it is imperative to continue investigating the role of micro-scale designed artefacts, specifically in the way they afford ‘urban’ forms of human inhabitation and social interaction in specific situations.

As inspiration for future research, this paper highlights the importance of continued investigation of passengers’ and airport visitors’ experiences at an intimate micro scale. This includes the examination of urban and mobility literacies from the point of view of past experiences in urban public spaces, particularly how cultural aspects and ‘perceptual memory’ (Degen and Rose Citation2012) influence the way people make sense of space: how the understanding of urban public spaces is translated into and used to understand and inhabit ambiguous spaces like the airport. As argued elsewhere (Hernandez-Bueno Citation2021, 456), ‘the passenger experience starts outside the airport’ in not only physical but also experiential terms. In this sense, the passenger experience, and the design that frames it, cannot be investigated in isolation – but must instead be viewed in relation to other (urban) situations and interactions inside and outside the airport space.

Acknowledgements

Material for this paper comes from a doctoral research project titled 'Becoming a Passenger’ carried out during 2017-2021. ‘Becoming a Passenger’ was part of the ‘Airport City Futures’ research project that was fully funded by Innovation Fund Denmark. I would like to thank Copenhagen Airport for collaborating with me during the research project and data collection in the airport. In addition, I would like to thank the editors of this special issue Peter Merriman and Samuel Mutter for their valuable feedback and guidance. I would like to thank to Ole B. Jensen for his critical feedback. Finally, I would like to thank the anonymous journal reviewers for their critical feedback and journal editor for guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adey, P. 2008. “Airports, Mobility and the Calculative Architecture of Affective Control.” Geoforum 39 (1): 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.09.001.

- Adey, P. 2010. Aerial Life. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Amin, A., and N. J. Thrift. 2002. Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Augé, M. 1995. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. London: Verso.

- Bissell, D. 2007. “Animating Suspension: Waiting for Mobilities.” Mobilities 2 (2): 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100701381581.

- Büscher, M., J. Urry, and K. Witchger. 2011. Mobile Methods. London: Routledge.

- Chowdhury, R., and C. McFarlane. 2021. “The Crowd and Citylife: Materiality, Negotiation and Inclusivity at Tokyo’s Train Stations.” Urban Studies 59 (7): 1353–1371. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211007841.

- Christensen, C. B., E. Melvin, and A. V. Hernandez Bueno. 2022. “Design Interventions – Reflections and Perspectives for Urban Design Research.” The Nordic Journal of Architectural Research 34 (1): 15–48.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World. London: Routledge

- Degen, M. M., and G. Rose. 2012. “The Sensory Experiencing of Urban Design: The Role of Walking and Perceptual Memory.” Urban Studies [Online] 49 (15): 3271–3287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012440463.

- Edwards, B. 2005. The Modern Airport Terminal: New Approaches to Airport Architecture. 2nd ed. London: Spon Press.

- Fuller, G., and R. Harley. 2004. Aviopolis: A Book About Airports. London: Black Dog.

- Gehl, J. 2011. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. 6th ed. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press.

- Gibson, J. (1979) 2015. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.

- Gottdiener, M. 2001. Life in the Air: Surviving the New Culture of Air Travel. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Graham, S., and N. Thrift. 2007. “Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Theory, Culture and Society 24 (3): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407075954.

- Hajer, M., and A. Reijndorp. 2001. In Search of the New Public Domain: Analysis and Strategy. Rotterdam: Netherlands Architecture Institute NAi Uitgevers/Publishers.

- Hernandez-Bueno, A. V. 2021. “Becoming a Passenger: Exploring the Situational Passenger Experience and Airport Design in the Copenhagen Airport.” Mobilities 16 (3): 440–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1864114.

- Hernandez-Bueno, A. V. 2022. “Airport Design and Situational Passenger Flows and Practices: Exploring Design as a Method in Copenhagen Airport.” Applied Mobilities 7 (2): 186–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2020.1847397.

- Hubregtse, M. 2020. Wayfinding, Consumption and Air Terminal Design. New York: Routledge.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Jensen, O. B. 2013. Staging Mobilities. London: Routledge.

- Jensen, O. B. 2020. “On the Move. On Mobile Agoras, Networked Selves, and the Contemporary City.” In The Routledge Companion to Urban Media and Communication, edited by Z. Krajina and D. Stevenson, 96–106. London: Routledge.

- Jensen, O. B., and D. B. Lanng. 2017. Mobilities Design. Urban Design for Mobile Situations. London: Routledge.

- Jensen, O. B., S. Smith, A. V. Hernandez-Bueno, and C. B. Christensen. 2020. “Mobilities Design Methods.” In Handbook on Research Methods and Applications for Mobilities, edited by Monika Büscher, Malene Freuendal-Pedersen, Sven Kesselring and Nikolaj Kristensen, 354–364. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kasarda, J. D., and G. Lindsay. 2011. Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Lassen, C. 2009. “A Life in Corridors: Social Perspectives on Aereomobility and Work in Knowledge Organizations.” In Aeromobilities, edited by Saulo Cwerner, Sven Kesselring and John Urry, 177–193. New York: Routledge.

- Lassen, C., O. B. Jensen, and A. V. Hernandez-Bueno. 2020. “Den Lærende Lufthavn.” Trafik & Veje 97 (12): 24–27.

- Magalhães, L., R. Vasco, and M. Rosário. 2017. “A Literature Review of Flexible Development of Airport Terminals.” Transport Reviews 37 (3): 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2016.1246488.

- Mela, A. 2014. “Urban Public Space Between Fragmentation, Control and Conflict.” City, Territory and Architecture 1 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-014-0015-0.

- Nikolaeva, A. 2013. “More Than Just an Airport”: Visions of the International Airport Terminal as a Multifunctional Urban Public Space, PhD diss., Aarhus: Aarhus University.

- Nikolaeva, A. 2017. ““Spoiled”, “Bored”, “Irritated” and “Nervous”: The Transformations of a Mobile Subject in Airport Design Discourse.” In Mobilising Design, edited by Justin Spinney, Suzanne Reimer and Philip Pinch, 25–34. New York: Routledge.

- Roseau, N. 2012. “Airports as Urban Narratives: Toward a Cultural History of the Global Infrastructures.” Transfers 2 (1): 32–54. https://doi.org/10.3167/trans.2012.020104.

- Sendra, P., and R. Sennett. 2020. Designing Disorder: Experiments and Disruptions in the City. London: Verso.

- Shuchi, S., R. Drogemuller, and L. Buys. 2017. “Flexibility in Airport Terminals: Identification of Design Factors.” Airport Management 12 (1): 90–108.

- Whyte, W. H. (1988) 2009. City: Rediscovering the Center. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.